Abstract

SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant evolved into multiple sub-lineages, some showing increased transmissibility and immune evasion. Despite decreased risk of severe disease, paediatric hospitalization rose. However, factors influencing clinical outcomes remain unclear. A total of 458 whole-genome Omicron sequences from patients 0–17 years, diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 at Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital (January-December 2023) were analysed. Clinical features, disease severity and circulating variants were assessed. Phylogenetic analysis was performed, and logistic regression identified factors associated with hospitalization. Among patients, 249 (54.4%) were male, with median age 0.6 years. Comorbidities were present in 105 (22.9%) patients, mainly immunocompromised (21.0%). Infections were predominantly from XBB (75.0%), JN.1 (12.4%), BA.5 (7.4%) and BA.2 (5.2%) clades. Upper respiratory infections predominated (73.8%), followed by asymptomatic (17.2%) and lower respiratory infections (4.6%), with nine patients having ≥ 1 co-infection. Comorbidities and lower respiratory infections were positively associated with hospitalization, while upper respiratory infections showed a negative association. Given the recent shift to RGN integrin-binding motif in Omicron sub-lineages, leading to altered pathogenesis, its presence was evaluated, revealing a predominance of RGN (N = 378, 84.6%). In conclusion, COVID-19 severity in paediatric patients was primarily driven by comorbidities and co-infections, while milder cases in healthy children may be associated with RGN integrin-binding motif.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) evolved rapidly, accumulating single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Some of these SNPs had little or no impact on the virus, while others modified viral features, eventually resulting in the emergence of new variants1,2,3. The different variants that emerged have varied in transmissibility, virulence, immune evasion, and disease severity4 and some have been classified as variants of concern (VOC) by the World Health Organization5.

After its designation as a VOC in November 2021, Omicron (SARS-CoV-2 variant B.1.1.529) rapidly replaced Delta as the predominant variant worldwide. Following the same pattern of rapid evolution as Delta, Omicron has undergone substantial genetic evolution, resulting in the emergence of different lineages. Initially, BA.1, BA.2, and BA.3 were identified in November 2021, followed by BA.4 and BA.5 in early 20226. Subsequently, recombinant sub-lineages such as XBB and BQ.1 have emerged7,8.

Some of these Omicron sub-lineages have shown higher transmissibility and greater ability to escape the immune response than previous sub-lineages, although they appear to be associated with a lower risk of severe illness9,10,11. This was in part explained by a switch in Omicron sub-lineages from a RGD (arginine/glycine/aspartic acid) integrin-binding motif to RGN (arginine/glycine/asparagine) integrin-binding motif12. This variation alters the interaction of the virus with host cells, reducing its affinity for endothelial cells, which are involved in the most severe complications of COVID-19, such as inflammation and thrombosis13. Consequently, this modification results in clinically milder disease and less severe systemic effects, while potentially increasing transmissibility and immune evasion capacity compared to earlier variants14.

However, during the Omicron wave, while the severity of infections in children decreased, an increase in childhood hospitalization rates was observed15,16,17,18. This paradoxical observation was likely due to the overall increase in SARS-CoV-2 transmissibility observed with the Omicron variant, leading to more children being exposed to the virus. Consequently, paediatric hospital admissions for COVID-19 increased during the Omicron period, particularly among unvaccinated children and those with multiple medical comorbidities19,20. These risk factors increase the risk of severe COVID-19 manifestations and outcomes compared to healthy children. Given the high transmissibility of Omicron, there is the need for data describing the disease severity caused by Omicron, especially for new and emerging sub-lineages, in the paediatric population.

The primary objectives of this study were to characterize the spectrum of disease manifestations and the risk of disease progression in the presence of the Omicron variant and its novel sub-variants, and to identify potential viral genetic determinants associated with different clinical manifestations and outcomes.

Results

Patient characteristics

From January to December 2023, 30,243 SARS-CoV-2 tests were performed in paediatric subjects 0–17 years of age at the Bambino Gesù Children Hospital IRCCS in Rome, of which 1,510 (5.0%) resulted positive. Among them, 576 nasopharyngeal swabs were characterized by cycle threshold (Ct) < 30 or Antigenic Cut-off index (COI) > 100 and had demographic and clinical information available and were available for sequencing. In comparisons of the general and the identified SARS-CoV-2 infected population selected for potential sequencing, no differences were observed in demographic characteristics or clinical findings, except for mean cycle thresholds (p = 0.002) and COI values (p < 0.001), which represented the inclusion criteria for sequencing (Supplementary Table 1). Among the 576 selected patients, sequencing was successfully obtained for 458 (79.5%) patients. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the final 458 patients are reported in Table 1. Two hundred forty-nine (54.4%) were male. Median age was 0.6 (interquartile range [IQR] 0.3–1.4) years. Three hundred and thirty-two (72.5%) patients were < 1 year of age. Most individuals were Italian (N = 404, 88.2%) and lived in Lazio region (i.e. residing in the same region as the hospital, N = 415, 90.6%). One hundred and five (22.9%) patients presented with at least one comorbidity. The most prevalent comorbidities were being immunocompromised (22/105, 21.0%), cardiovascular disorders (15/105, 14.3%), genetic disorders (10/105, 9.5%), and neurological disorders (7/105, 6.7%). Among the other comorbidities, the following could be found: Asthma (N = 3), Bilateral Atresia Auris and Right Cryptorchidism (N = 1), Congenital left clubfoot (N = 1), Developmental Delay (N = 1), Ectopic Kidney (N = 1), Esophageal atresia (N = 1), Gastrointestinal diseases (N = 2), Multicystic Kidney (N = 1), Periodic Fever, Aphthous Stomatitis, Pharyngitis, Adenitis Syndrome (PFAPA, N = 1), Reactive airway disease (N = 2), Right Parietal Fracture (N = 1), Speech and Motor Delay, Microcephaly, and Facial Dysmorphisms (N = 1), Spina Bifida (N = 1), Tetraparesis, Dysphagia and Psychomotor Retardation Outcomes of Anoxic Damage from Methaemoglobinemia (N = 1), and Others Not Specified (N = 46).

Focusing on hospitalization, most patients presented to the emergency department (n = 443, 96.7%), 99 (21.6%) required hospitalization with a median (IQR) length of 4 (3–9) days, and 7 (1.5%) were admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). A higher incidence of lower respiratory tract infections (15.2% vs. 1.7%, p < 0.001) and gastrointestinal symptoms (10.1% vs. 2.87%, p = 0.004) were observed in hospitalized patients, whereas upper respiratory tract infections were more prevalent among non-hospitalized patients (83.3% vs. 39.4%, p < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 1). Furthermore, a significant proportion of hospitalized patients were asymptomatic (35.4%vs. 12.3%, p < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 1), likely due to comorbidities.

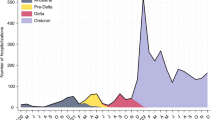

Distribution of SARS-CoV-2 lineages and integrin binding domain

Most SARS-CoV-2 infections (75.0%) were caused by XBB and its sub-lineages, followed by JN.1 (12.4%), BA.5 (7.4%), and BA.2 (5.2%) (Fig. 1). Eleven different sub-lineages of interest were identified. The most prevalent were EG.5.1 (n = 77), JN.1 (n = 57), XBB.1.5 (n = 37), XBB.1.16 (n = 30), BQ.1 (n = 28), XBB.1.9 (n = 12) and XBB.2.3 (n = 10). All sub-lineages identified are reported in the Supplementary material.

Several specific integrin-binding motifs were present in the Omicron viral sequences. Among the 458 sequences analysed, only 3 presented the RGD (arginine/glycine/aspartic acid) motif, while most presented the RGN (arginine/glycine/asparagine) motif (Supplementary material). Additionally, the KGN (lysine/glycine/asparagine) and KGD (lysine/glycine/aspartic acid, already observed in SARS-CoV-1) motifs were present in 65 and 1 sequences, respectively (Supplementary material).

Clinical manifestations

The majority of patients presented with upper respiratory infections (n = 338, 73.8%), followed by asymptomatic infections (n = 79, 17.2%), while a smaller proportion exhibited lower respiratory infections (n = 21, 4.6%) (Figs. 1 and 2).

By analysing the distribution of lineages in these infections we observed that lower infections were mainly characterised by the XBB.1 lineage (11/21, 52.4%), followed by the XBB.1.5 lineage (19/21, 19%) and then by the others with a frequency of less than 10%, except for BA.5, which was never observed. Even in upper infections, the main lineage involved was XBB.1 (145/338, 42.9%), followed by the lineage XBB.1.5 (16.6%) and JN.1 (13.3%). The lineage distribution in patients with asymptomatic infection was equally distributed (within 10%), except for XBB.1, which was found in 35.4%.

Estimated Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of the 458 SARS-CoV-2 sequences obtained from population aged ≤ 18 years. The maximum likelihood was inferred from a core genome alignment of 29,164 bp. The phylogeny was estimated with IQTREE using the best-fit model of nucleotide substitution GTR + F + R3 with 1,000 replicates and fast bootstrapping. The numbers on leaves represent the sample IDs, and bootstrap values higher than 90 are shown on branches. SARS-CoV-2 genomes were highlighted in different colours against omicron lineages (first, inner circle). Information regarding symptoms (second circle), comorbidities (third circle) and hospitalization (fourth, outer circle) were also reported. Among symptoms, lower and upper respiratory tract infections were considered regardless of gastrointestinal symptoms.

Correlation with hospitalization

Univariable and multivariable logistic regression models were used to assess whether the risk of hospitalization was associated with certain SARS-CoV-2 sub-lineages, clinical manifestations, or demographic characteristics (Table 2). The results showed that the presence of at least one comorbidity (versus no comorbidity) and involvement of the lower respiratory airways compared with asymptomatic patients were positively associated with hospitalization (adjusted OR [95% CI]: 5.59 [3.22–9.71], p-value < 0.001; and 3.16 [1.02–9.81], p-value = 0.046, respectively), while a negative association was observed with upper respiratory airways with respect to asymptomatic patients (0.25 [0.13–0.46], p-value < 0.001). These results were confirmed by performing the analysis under two extreme assumptions: treating all missing data as vaccinated and treating all missing data as unvaccinated (Supplementary Table 2).

In particular, the risk of hospitalization was significantly higher among patients with lower respiratory infections compared to those without (71.0% vs. 19.2%, p = 0.026), and ICU admissions were more frequent among patients with lower respiratory infections compare to those without (23.8% vs. 0.5%, p < 0.001). No associations were observed between the risk of hospitalization and specific Omicron lineages.

Viral and bacterial co-infections

Among the 21 patients with lower respiratory infection, nine (42.9%) presented with co-infection, namely four viral co-infections (1 Metapneumovirus, 1 Respiratory Syncytial Virus, 1 Rhinovirus A/B/C, and 1 Bocavirus 1/2/3 + Respiratory Syncytial Virus + Rhinovirus A/B/C), four bacterial co-infections (1 Pseudomonas aeruginosa + Staphylococcus aureus, 1 Staphylococcus aureus + Pseudomonas aeruginosa, 1 Escherichia coli, 1 Pseudomonas aeruginosa + Klebsiella pneumoniae + Enterococcus faecalis), and one viral and bacterial co-infection (Human Herpesvirus 6, HHV-6 + Staphylococcus aureus + Enterococcus faecalis, + Streptococcus pneumoniae).

Most co-infections primarily involved the respiratory tract, with eight patients showing respiratory involvement and pathogens isolated from respiratory samples including Metapneumovirus, RSV, Rhinovirus, Bocavirus, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterococcus faecalis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Escherichia coli. However, in several cases, other body districts were also affected: blood co-infections were documented in two patients, one positive for Pseudomonas aeruginosa and the other for Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and HHV-6; gastrointestinal co-infections were identified in three patients through positive coprocultures or fecal PCR for Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterococcus faecalis, and enteroaggregative Escherichia coli; additionally, urinary tract involvement was noted in one patient with a positive urinary antigen test for Streptococcus pneumoniae. Among these nine patients with co-infections, five were admitted to the ICU and presented with acute respiratory failure (Supplementary Table 3).

Among these 9 patients with co-infections, 5 were admitted to ICU and presented acute respiratory failure.

Discussion

This study provides insights into the clinical manifestations and outcomes of Omicron variant infections among paediatric patients. Notably, infants under one year of age emerged as the most affected group, although they generally exhibited mild symptoms. This is consistent with prior studies, which have observed that children affected by COVID-19 during the Omicron wave were significantly younger than those in pre-Omicron periods21.

We found an association between disease severity and specific clinical conditions, namely lower respiratory infections and comorbidities. The risk of hospitalization was significantly higher among paediatric patients with lower respiratory infections and underlying medical conditions, underscoring the importance of early recognition and management of risk factors to mitigate severe outcomes in paediatric COVID-19 cases. Indeed, it has been observed that during the Omicron wave, the severity of COVID-19 was mainly due to the presence of underlying conditions or co-infection, and not only the infecting variants22. Although other studies have suggested strong differences in clinical manifestations (respiratory tract involvement and hospitalization risk) between BA.1 and BA.2 subvariants with BA.5 subvariant, we did not observe an association between specific Omicron lineages and COVID-19 manifestations or hospitalization risk23.

The prevalence of milder disease manifestations, observed in our study, may be attributed to the specific integrin binding motif present in the viral sequences, putatively leading to the limited inflammatory response. The RGD (arginine/glycine/aspartic acid) amino acid sequence, present on the spike protein receptor-binding domain (RBD), is the most frequent motif that plays a key role in integrin binding, as it interacts with different integrins12. In the Omicron sub-lineages BA.2, BA.4, BA.5, and XBB.1.5, the aspartate residue within the integrin-binding RGD motif has mutated to asparagine leading to the emergence of an RGN motif. While the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein is known to primarily interact with RGD-binding integrins αVβ324 and α5β125, the D405N mutation has recently been found to inhibit binding to integrin αVβ313,26. Since this integrin is a key receptor involved in viral entry and host cell infection, the presence of this inhibitory motif across the majority of our analysed sequences suggests a potential mechanism by which the virus may attenuate its pathogenicity, leading to less severe clinical outcomes in affected individuals. Moreover, we identified the presence of an additional integrin binding motif, the KGN (lysine/glycine/asparagine) motif, in sequences belonging to JN.1 and BA.2.86 sub-lineages, suggesting a further evolution of the virus in the newly merged variants.

Our study has several limitations. First, in our cohort of 458 patients, COVID-19 vaccination status information was not available for 234 individuals, 214 were children not eligible for vaccination, 1 was vaccinated with three doses, and 9 were unvaccinated. Therefore, we could not evaluate whether COVID-19 vaccination was associated with different clinical manifestations and outcomes following infection. This limitation reflects the overall vaccination landscape in the paediatric population in Italy. According to data from the Italian Ministry of Health, by the end of September 2023, vaccine uptake among children aged 0–4 years was extremely low27. Only 626 children (0.03% of the population in this age group) had received at least one dose, and just 16 children (0.00%) had completed the primary vaccination course. Considering that the majority of our cohort (72.5%) was under 1 year of age, limited vaccine coverage in this population was expected and consistent with national trends.

Second, our study focused on acute COVID-19 and was not designed for longitudinal follow-up of patients. As most patients are not monitored after discharge, observation of longer-term outcomes, such as Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) and long COVID, were out-of-scope of this study. Third, although we observed that having an underlying medical condition was associated with an elevated risk of hospitalization among paediatric patients, we did not have sufficient sample size to assess whether specific conditions were associated with the increased risk. Another limitation of this study is the potential incompleteness of clinical data due to its retrospective design, which may have affected the availability and consistency of certain clinical variables. In addition, only 38% of SARS-CoV-2–positive samples met the sequencing threshold (Ct < 30 or COI > 100), which may have introduced selection bias by over-representing patients with higher viral loads and greater clinical severity. Since the monthly distribution of cases did not suggest distinct epidemic waves or notable temporal variation, we did not adjust for calendar time in our analysis. Finally, although we used multivariable regression models to adjust for potential confounders, residual and unmeasured confounding may nonetheless be present given the observational nature of our study. Moreover, in future studies, the increase of number of cases will surely help improving the stability of the multivariable logistic regression model.

Our findings offer valuable insights into the mechanisms underlying COVID-19 pathogenesis, and highlight the evolving nature of SARS-CoV-2. In particular, our study emphasizes that the severity of COVID-19 in paediatric patients during the Omicron period was primarily due to underlying conditions and co-infections rather than the specific infecting variant. The presence of comorbidities significantly influenced hospitalization risk and clinical outcomes, while the milder disease manifestations observed in healthy children could be linked to mutations in the integrin-binding motifs of the viral spike protein, which may reduce the virus’ ability to bind to key receptors involved in host cell infection, potentially contributing to less severe clinical outcomes. These findings highlight the critical role of comorbidities in determining the risk of progression to severe illness in children and underscore the importance of early recognition and management of risk factors. Understanding the mechanisms of viral evolution and pathogenicity can inform future therapeutic interventions and improve clinical management of COVID-19 in paediatric populations.

Methods

Design, setting, and population

This retrospective observational study included all patients 0–17 years of age who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis at Bambino Gesù Children Hospital from January to December 2023, regardless of symptoms. During the pandemic, all patients presenting to the emergency department or requiring hospital admission were tested for SARS-CoV-2, irrespective of whether they exhibited symptoms, as part of the hospital’s infection control measures.

To be included, patients needed to have a laboratory confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, complete demographic and clinical data available, as well as documented clinical outcomes. Moreover, only those infected with an Omicron variant, confirmed through genetic characterization, were considered. Patients older than 17 years, those lacking reliable demographic or clinical information, or those without retrievable biological samples were excluded from the study. Nasopharyngeal swabs were collected at the time of admission for SARS-CoV-2 testing and sequencing from a proportion of patients. SARS-CoV-2 infection was detected by antigenic or molecular tests. Specifically, the antigenic tests employed were Roche Elecsys SARS-CoV-2 Antigen (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) and RADT STANDARD F COVID-19 Ag FIA (SD BIOSENSOR, Korea). The molecular tests used were Cepheid Xpert Xpress CoV-2 Plus (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and SARS-CoV-2 ELITe MGB Kit® (Elitechgroup, Turin, Italy). Nasopharyngeal swabs with a cycle threshold (Ct) < 30 in molecular tests or Antigenic Cut-off index (COI) > 100 in antigen tests were considered suitable for sequencing. Among 1,510 SARS-CoV-2–positive samples, 576 (38%) met the sequencing threshold, while 934 (62%) did not.

Information on patient demographics and clinical findings were obtained retrospectively from pseudonymized electronic medical records. Comorbidities were categorized based on the systems and functions most directly affected by these conditions.

The severity of COVID-19 was defined on the basis of clinical features, laboratory tests and chest X-ray images28. The following definitions were used: (i) asymptomatic infection, defined as testing SARS-CoV-2 positive but not developing any clinical symptoms; (ii) upper respiratory tract infection, such as rhinitis, pharyngitis, cough, sore throat, runny nose, sneezing, or symptoms of a gastrointestinal tract infection (vomiting, diarrhoea); and (iii) lower respiratory tract infection including clinical signs of bronchitis or pneumonia (with or without signs of gastrointestinal symptoms)29.

Ethics committee statement

The study protocol was approved by the local Research Ethics Committee of Ospedale Pediatrico Bambino Gesù IRCCS (prot. 2384_OPBG_2021) and was conducted under the principles of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committee of Ospedale Pediatrico Bambino Gesù IRCCS following the hospital regulations on observational retrospective studies.

Virus amplification and sequencing

Viral RNAs were extracted from nasopharyngeal swabs by using QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), followed by purification with Agencourt RNAClean XP beads (Beckman Coulter Life Sciences, CA, USA). Both the concentration and the quality of all isolated RNA samples were measured and checked with the Nanodrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). Amplicons of whole genome sequences of SARS-CoV-2 were generated with a 50 ng viral RNA template, by using CleanPlex SARS-CoV-2 Research and Surveillance Panel (Paragon Genomics, Hayward, CA, USA), QIAseq DIRECT SARS-CoV-2 Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and Illumina COVIDSeq Assay (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) following manufacturers’ protocol. Libraries were then generated using the Nextera DNA Flex library preparation kit with Illumina index adaptors and sequenced on a MiSeq instrument (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) with 2 × 150-bp paired-end reads. Raw reads were trimmed for adapters and filtered for quality (Phred score > 28) using Fastp (v0.23.2)30. Reference-based assembly was performed with BWA-mem (v0.7.17)31 aligning against the GenBank reference genome NC_045512.2 (Wuhan, collection date: December 2019)32.

SNP variants were called with freebayes (v1.3.2)33 and all SNPs having a minimum supporting read frequency of 2% with a depth ≥ 10 were retained.

Phylogenetic analysis

Consensus sequences were generated using the GitHub freely distributed software vcf_consensus_builder34 considering all SNPs having a minimum read frequency of 40% (high-abundant mutations). SARS-CoV-2 lineages of the obtained consensus sequences were assigned according to Pangolin application (Pangolin v4.1.1)35 and then grouped into seven major sub-lineages (BA.2, JN.1, BA.5, XBB, XBB.1, XBB.1.16, XBB.1.5). All sub-lineages identified are reported in the Supplementary material.

Sequences were aligned using MAFFT v7.475 and manually inspected using Bioedit. The final alignment comprised 458 sequences of 29,164 nucleotides of length. In order to investigate the phylogeny of Omicron clade that affects the paediatric population (0–17 years), a maximum likelihood (ML) phylogeny tree was generated using IQTREE2 (v2.1.3)36 with 1000 bootstrap replicates, using the best-fit model of nucleotide substitution GTR + F + R3 inferred by ModelFinder37. Annotation of the phylogenetic tree, including information about lineages, symptoms, comorbidity and hospitalization was performed with iTOL (v5)38.

Co-infections evaluation

Co-infections were investigated in patients diagnosed with lower respiratory tract infections on samples collected as part of routine clinical care. Viral agents were identified through molecular tests (Allplex Respiratory Panel assay, Seegene Inc., Korea and ARGENE® HHV6 R-GENE®, BioMerieux, France) while bacterial pathogens were detected via culture methods.

The presence of co-infections was defined exclusively by the detection of at least one positive result from any diagnostic test, without requiring clinical correlation or additional confirmatory testing.

Statistical analysis

The Likelihood Ratio Test, followed by a logistic regression model that estimated odd ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs), was used to compare demographic and clinical findings between general and selected SARS-CoV-2 infected populations.

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess the distribution (normal or non-normal) of the continuous variables. Descriptive statistics were expressed as median (interquartile range, IQR) for continuous data and number (%) for categorical data. To assess for significant differences in patient characteristics and clinical findings, Fisher’s exact test and the Chi-Square test for trend, and the Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used for categorical and continuous variables, respectively.

Univariable and multivariable logistic regression models were employed to assess whether the risk of hospitalization was associated with specific SARS-CoV-2 sub-lineages, clinical manifestations, or demographic characteristics. Patients with a previous SARS-CoV-2 infection and those who had already been vaccinated (N = 6) were excluded from these analyses. The primary outcome was hospitalization, with the reference group being patients who were not hospitalized. The covariates included age, Omicron sub-lineage, clinical manifestations and the presence of comorbidity (versus patients without comorbidity). Model stability was evaluated by calculating the events-per-variable (EPV)39, and multicollinearity was assessed using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). Model fit was examined with the Cox & Snell and Nagelkerke R² statistics.

For the clinical manifestations, patients were categorized into four groups: those with lower respiratory airway involvement, those with upper respiratory airway involvement, those with only gastrointestinal symptoms, and those who were asymptomatic.

For comorbidities, patients were classified as patients with at least one comorbidity, regardless of type (immunocompromised, cardiovascular disorders, genetic disorders, neurological disorders etc.), and patients without comorbidities. The reference category in the logistic regression models was the presence of at least one comorbidity.

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

Al-Khatib, H. A. et al. Comparative analysis of within-host diversity among vaccinated COVID-19 patients infected with different SARS-CoV-2 variants. iScience. 18;25(11):105438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2022.105438. Epub 2022 Oct 25. PMID: 36310647; PMCID: PMC9595287. (2022).

Safari, I., InanlooRahatloo, K. & Elahi, E. Emerged haplotypes and informative Tag nucleotide variations. J. Med. Virol. 93 (4), 2010–2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.26553 (2021). Epub 2020 Nov 1. PMID: 32975856; PMCID: PMC7537300Evolution of SARS-CoV-2 genome from December 2019 to late March 2020.

Pagani, I., Ghezzi, S., Alberti, S., Poli, G. & Vicenzi, E. Origin and evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Eur. Phys. J. Plus. 138 (2), 157. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjp/s13360-023-03719-6 (2023). Epub 2023 Feb 16. PMID: 36811098; PMCID: PMC9933829.

Bai, H. et al. A systematic mutation analysis of 13 major SARS-CoV-2 variants. Virus Res. 345, 199392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2024.199392 (2024). Epub 2024 May 15. PMID: 38729218; PMCID: PMC11112362.

Updated working definitions. And primary actions for SARS-CoV-2 variants, 4 October 2023 (WHO).

Shrestha, L. B., Foster, C., Rawlinson, W., Tedla, N. & Bull, R. A. Evolution of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variants BA.1 to BA.5: implications for immune escape and transmission. Rev. Med. Virol. https://doi.org/10.1002/rmv.2381 (2022).

WHO. TAG-VE statement on Omicron sublineages BQ.1 and XBB. (2022). https://www.who.int/news/item/27-10-2022-tag-ve-statement-on-omicron-sublineages-bq.1-and-xbb

Scarpa, F. et al. Genetic and structural data on the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BQ.1 variant reveal its low potential for epidemiological expansion. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (23), 15264. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232315264 (2022). PMID: 36499592; PMCID: PMC9739521.

Tian, D. D., Sun, Y. H. & Xu, H. H. The emergence and epidemic characteristics of the highly mutated SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. J. Med. Virol. 94 (6), 2376–2383. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.27643 (2022).

Arabi, M. et al. Severity of the Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variant compared with the previous lineages: A systematic review. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 27 (11), 1443–1464. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.17747 (2023). Epub 2023 May 18. PMID: 37203288; PMCID: PMC10243162.

Dai, B. et al. Update on Omicron variant and its threat to vulnerable populations. Public. Health Pract. (Oxf). 7, 100494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhip.2024.100494 (2024). Published 2024 Mar 25.

Luan, J., Lu, Y., Gao, S. & Zhang, L. A potential inhibitory role for integrin in the receptor targeting of SARS-CoV-2. J. Infect. 81 (2), 318–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.046 (2020).

Bugatti, A. et al. The D405N mutation in the Spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.5 inhibits Spike/integrins interaction and viral infection of human lung microvascular endothelial cells. Viruses 15, 332. https://doi.org/10.3390/v15020332 (2023).

Huntington, K. E. et al. Integrin/TGF-β1 inhibitor GLPG-0187 blocks SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron pseudovirus infection of airway epithelial cells which could attenuate disease severity. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2022 Jan 3:2022.01.02.22268641. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.02.22268641. Update in: Pharmaceuticals (Basel). ;15(5):618. doi: 10.3390/ph15050618.

Belay, E. D. & Godfred-Cato, S. SARS-CoV-2 spread and hospitalisations in paediatric patients during the Omicron surge. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health. 6 (5), 280–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(22)00060-8 (2022).

Cloete, J. et al. Paediatric hospitalisations due to COVID-19 during the first SARS-CoV-2 Omicron (B.1.1.529) variant wave in South africa: a multicentre observational study. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health. 6 (5), 294–302 (2022). Epub 2022 Feb 18. PMID: 35189083; PMCID: PMC8856663.

Liu, Y. et al. Epidemiological, clinical, and household transmission characteristics of children and adolescents infected with SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant in Shanghai, china: a retrospective, multicenter observational study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 129, 1–9 (2023). Epub 2023 Jan 29. PMID: 36724865; PMCID: PMC9884399.

Di Chiara, C. et al. Clinical features of COVID-19 in Italian outpatient children and adolescents during Parental, Delta, and Omicron waves: a prospective, observational, cohort study. Front. Pediatr. 11, 1193857. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2023.1193857 (2023). PMID: 37635788; PMCID: PMC10450148.

Piralla, A. et al. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron and delta variants in patients requiring intensive care unit (ICU) admission for COVID-19, Northern Italy, December 2021 to January 2022. Respir Med. Res. 83, 100990. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resmer.2023.100990 (2023). Epub 2023 Mar 4. PMID: 36871459; PMCID: PMC9984278.

Melamed, S. et al. Pediatric COVID-19 hospitalizations during the Omicron surge. WMJ 122 (5), 342–345 (2023). PMID: 38180921.

Stopyra, L. et al. Characteristics of hospitalized pediatric patients in the first five waves of the COVID-19 pandemic in a single center in Poland-1407 cases. J. Clin. Med. 11 (22), 6806. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11226806 (2022). PMID: 36431283; PMCID: PMC9697870.

Quintero, A. M. et al. Differences in SARS-CoV-2 clinical manifestations and disease severity in children and adolescents by infecting variant. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 28 (11), 2270–2280. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2811.220577 (2022). PMID: 36285986; PMCID: PMC9622241.

de Prost, N. et al. SEVARVIR investigators. Clinical phenotypes and outcomes associated with SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variants BA.2, BA.5 and BQ.1.1 in critically ill patients with COVID-19: a prospective, multicenter cohort study. Intensive Care Med. Exp. 11 (1), 48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40635-023-00536-0 (2023).

Nader, D., Fletcher, N., Curley, G. F. & Kerrigan, S. W. SARS-CoV-2 uses major endothelial integrin αvβ3 to cause vascular dysregulation in-vitro during COVID-19. PLoS One. 16 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253347 (2021).

Beddingfield, B. J. et al. The integrin binding peptide, ATN-161, as a novel therapy for SARS-CoV-2 infection. JACC (J Am. Coll. Cardiol.): Basic. Translational Sci. 6, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacbts.2020.10.003 (2021).

Beaudoin, C. A. et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariant Spike N405 unlikely to rapidly deamidate. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 666, 61–67 (2023). Epub 2023 May 2. PMID: 37178506; PMCID: PMC10152834.

Dong, Y. et al. Epidemiology of COVID-19 among children in China. Pediatrics 145 (6), e20200702. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-0702 (2020). Epub 2020 Mar 16. PMID: 32179660.

Alteri, C. et al. Epidemiological characterization of SARS-CoV-2 variants in children over the four COVID-19 waves and correlation with clinical presentation. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 10194. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14426-0 (2022). Erratum in: Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):12814. PMID: 35715488; PMCID: PMC9204374.

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. Fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890 (2018).

Houtgast, E. J., Sima, V. M., Bertels, K. & Al-Ars, Z. Hardware acceleration of BWA-MEM genomic short read mapping for longer read lengths. Comput. Biol. Chem. 75, 54–64 (2018).

Scutari, R. et al. Molecular characterization of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron clade and clinical presentation in children. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 5325. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-55599-0 (2024). PMID: 38438451; PMCID: PMC10912656.

Garrison, E. & Marth, G. Haplotype-based variant detection from short-read sequencing. Preprint at (2012). http://arXiv.org/1207.3907

Minh, B. Q. et al. IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 37, 15. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msaa015 (2020).

Kalyaanamoorthy, S., Minh, B. Q., Wong, T. K. F., von Haeseler, A. & Jermiin, L. S. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods. 14 (6), 587–589. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.4285 (2017). Epub 2017 May 8. PMID: 28481363; PMCID: PMC5453245.

Letunic, I. & Bork, P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v5: an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, W293–W296. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab301 (2021).

van Smeden, M. et al. No rationale for 1 variable per 10 events criterion for binary logistic regression analysis. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 16 (1), 163. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-016-0267-3 (2016). Published 2016 Nov 24.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted as a collaboration between Ospedale Pediatrico Bambino Gesù and Pfizer. Ospedale Pediatrico Bambino Gesù is the study sponsor. We thank Pfizer that financially supported this work. The authors also thank the whole staff of the Microbiology Laboratory of Ospedale Pediatrico Bambino Gesù IRCCS for outstanding technical support in processing swab samples, performing laboratory analyses and data management.

Funding

This work was supported by the Italian Ministry of Health with Current Research funds. This study was conducted as a collaboration between Ospedale Pediatrico Bambino Gesù and Pfizer. Ospedale Pediatrico Bambino Gesù is the study sponsor.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S., V.Fo., C.A., C.F.P.; methodology, R.S., V.Fo., M.M., L.F.R., A.G., V.Fi.; resources L.Co., M.M., L.F.R.; recruited samples and enrolled patients, A.S., A.C.V., L.Cu., C.D., A.D.S.; data curation, R.S., V.Fo., J.L.N., L.P., M.M.M., C.A., J.Y., A.P., S.R.V., C.R, formal analysis: R.S., V.Fo.; writing—original draft preparation, R.S., V.Fo.; writing—review and editing, C.F.P., J.M.M.L. C.M.; Investigator, R.Q., C.M., L.L., M.L.C.D.A., A.C., M.R., A.V., C.F.P.; supervision, C.F.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical declarations

The study protocol was approved by the local Research Ethics Committee of Ospedale Pediatrico Bambino Gesù IRCCS (prot. 2384_OPBG_2021) and was conducted under the principles of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committee of Ospedale Pediatrico Bambino Gesù IRCCS following the hospital regulations on observational retrospective studies.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Scutari, R., Fox, V., Nguyen, J.L. et al. Clinical manifestations and severity of COVID-19 caused by Omicron among paediatric patients aged 0–17 years in Italy. Sci Rep 15, 36638 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20483-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20483-y