Abstract

Agronomic parameters have been extensively studied under lab conditions to determine effect of nanoparticles (NPs). However, the yield characteristics have not been determined especially to biodiesel producing crops. This study explores the effect of copper sulfide (CuS) NPs on the growth, biochemical properties, productivity, and oil content of Eruca sativa under field condition. The oil extracted from E. sativa seeds was converted to biodiesel via transesterification reaction and analyzed through FT-IR, GC-MS and NMR. Further the fuel properties were compared with international standards. The results demonstrate that CuS NPs markedly improved root (20.23%) and shoot length (21.17%), branches per plant (45.64%), plant biomass (49.46%), siliqua per plant (48.68%), seeds per siliqua, and oil percentage (18.27%) compared to control plants. Atomic absorption spectroscopy depicts that root accumulated maximum Cu followed by shoot and seeds. Biochemical analysis showed that plants treated with CuS NPs had higher level of protein (175.16 mg/kg FW), superoxide dismutase (0.63 nM/min/gFW) and peroxidase (0.74 nM/min/gFW) activities as compared to control plants. The roots and shoots of E. sativa showed enhanced total phenolic content, total flavonoid content, and improved antioxidant activities. The biodiesel yield was up to 85% using 1% KOH as catalyst and 6:1 oil to methanol ratio. FT-IR, NMR and GC-MS analyses of biodiesel indicate that CuS NPs has negligible effect on the biodiesel composition. Fuel properties i.e., pour point, cloud point, flash point, viscosity, density, sulfur content and ash content are found to comply with international standards. This study highlights the potential of CuS NPs in elevating agricultural yield and offers a sustainable approach to biofuel production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The application of nanoparticles (NPs) in agriculture has emerged as novel strategy to promote plant growth productivity and resilience. Copper sulfide nanoparticles (CuS NPs), in particular, have been evaluated for their potential antimicrobial properties1 and their role in enhancing plants agronomic parameters. Yet, the impact of CuS NPs on Eruca sativa under field condition remains unexplored particularly regarding agronomic parameters and oil content characteristics. Copper (Cu) is an essential micronutrient that promotes plant growth, plays an important role in photosynthesis, protein metabolism, and electron transport chain2,3,4. Cu based NPs have been used as fertilizer, growth regulators, pesticides, and herbicides5. The size, high surface area, shape, and peculiar chemical and physical properties of NPs affect the plant growth and nutrition value6. Due to their slow ion release potential and higher adsorption, NPs including Cu NPs have gained attention in agricultural applications7,8. The bioaccumulation and translocation factors determine the uptake and translocation potential of metallic NPs and their respective ions in crops9. Cu nanoparticles have shown a positive effect on plant height, biomass, yield, and seed quality of Glycine max8,10. The positive effect on the growth and development of plants also include tolerance to biotic and abiotic variations, and stress mitigation due to biochemical and metabolic functions11. Under drought stress, Cu NPs increased total number of seeds, grain yield, chlorophyll content, and enzymes activities in maize12. Foliar application of Cu NPs increased fruit size in tomato13 and ameliorates toxicity of heavy metal by evoking antioxidant enzymes activities14. Rameen et al.15 reported improvement in productivity and oil quality of Brassica napus upon exposure to Cu NPs. Moreover, assessing the antioxidant capacities of the plant are important for understanding the defense mechanism of plants and its potential application in plant health. Sulfur (S) is an important component of S-containing amino acids and proteins. It promotes growth and metabolism of the plants, and regulates crop productivity and quality. Sulfur also minimizes the negative impact of heavy metals via higher antioxidant enzymes activities16.

Eruca sativa L. is a member of herbaceous family Brassicaceae (mustard family), commonly known as taramira, rocket salad, Rocket seed or arugula. It is a leafy vegetable, famous for its characteristic flavor, nutritional value, and oil content. E. sativa has also gained attention due to its rich phytochemical profile, particularly its phenolic and flavonoid compounds, which contribute to its antioxidant properties (17,18. These bioactive compounds associate with different health benefits, including antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory impacts19. The oil extracted from the seeds of E. sativa is a potential feedstock for biodiesel production. Biodiesel is a renewable energy source and may be used as alternative to conventional fossil fuel. Moreover, it is nontoxic, environment friendly, emit low gases, and require no modification for diesel engine20. Efficient and cost-effective production of biodiesel faces many challenges including high prices. Among 350 oil producing crops used as biodiesel feed stock, 95% are edible that led to food versus fuel conflict21,22.

The current study was aimed to evaluate the effect of copper sulfide nanoparticles (CuS NPs) on Eruca sativa under field conditions. Different agronomic parameters were measured. Plants extracts were assessed for antioxidant properties, and oil extracted from seeds was analyzed for biodiesel production. This inclusive approach peruses to explicate the multifaceted impact of Cu-based treatments on Eruca sativa, contributing significant insights into sustainable agricultural practices and biodiesel production.

Materials and methods

The study describes synthesis, characterization of CuS NPs and their application as nanofertilizer under field condition to analyze growth, biochemical response, and yield characteristics of E. sativa plants. The seed oil was converted into biodiesel and characterized. The study was carried out at Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad and National Agriculture Research Center (NARC) Islamabad. All the chemicals used in this study were purchased from Merck or Sigma-Aldrich otherwise mentioned.

Synthesis and characterization of CuS NPs

Co-precipitation method as reported by Al-Jawad et al.23, was followed for the synthesis of CuS NPs. In short 0.5 M Na2S aquous solution was slowly mixed with 0.5 M CuSO4.5H2O solution. The reaction was stirred at 1500 rpm for 2.5 h. Thereafter, the color changed to greenish black. The CuS NPs were collected by centrifugation at 8000 rpm for 10 min at 25°C. The NPs were washed thrice with distilled water, dried, and calcinated at 500 °C for 2 h.

The morphology of NPs sample was determined through scanning electron microscopy (SEM, TESCAN MIRA 3) and images were recorded at different magnifications operating with a 20kV electron beam. The elemental analysis of CuS NPs was carried out by Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) at the energy range of 0-20 kV and current of 1 x 10−9 A. X-ray diffraction (XRD) was used to analyze crystallinity of NPs by Model D8, Bruker AXS. The XRD pattern was obtained by using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406); the 2θ range was from 20 to 80° at a scanning rate of 0.02 deg/sec., increment = 0.02, operating voltage = 40 kV, and operating current = 30 mA. The average size of CuS NPs was calculated using Debye-Scherrer equation.

D = kλ/βcosθ

Where D is the size of the crystallite, k is the crystal’s shape factor which is 0.9, λ is the wavelength of Cu Kα which is 1.5404 Å, θ is the Braggs angle of the diffraction peak and β is the angular full width at half maximum (FWHM) of diffraction peak, measured in radian.

The surface morphology of NPs for presence of functional groups was analyzed through Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer (NicoletTM380). The spectrum was acquired with a resolution of 2 cm−1 over the range 500–4000 cm−1.

Description of experimental site

This study was conducted in open field at National Agriculture Research Centre (NARC) (33.4°N, and 73.8°E) Islamabad, Pakistan. The soil analysis before experiment, meteorological data during study, and study area map of NARC are shown in Table 1&Table 2, and Figure 1 respectively. According to Köppen climate classification, the experimental site is situated in a humid subtropical climate zone. Soybean, chickpea, sesame, linseed, and arugula etc. are the major crops of the selected study area. Eruca sativa, a rabi crop was cultivated in October-November 2022 followed by harvesting in April 2023.

Study area map of NARC, Islamabad Pakistan. (Figure copied from24 after permission).

Field study

Eruca sativa (Var. PM-26187) seed were sown in a loamy soil (pH 7.73). A plot of 3.2 × 3.4 meters (10.88 m2) was selected for each treatment, the row length was kept 3.2 m, and the distance maintained between two beds was 2.30 m with a 0.70m path between the rows. After irrigation, the soil was ploughed and seed were sowed in the month of October 2022. The weeds were removed after 15 days of seed germination and the plant-to-plant distance was kept 4-6 cm by thinning. CuS NPs and CuSO4 were applied by broadcasting in soil at the rate of 8 Kg ha−1 at 6-8 leaf stage. Randomized Complete Block Design (RCBD) was used to conduct the study in triplicate. The nitrogen and potassium fertilizer (50 Kg/ha) were applied in the experimental plots and the field was irrigated when required. The crop was harvested in the month of April 2023. At harvesting stage, 10 plants were randomly picked from each treatment to measure selected agronomic parameters. Quantitative characteristics i.e., root and shoot length, total branches per plant, dry weight per plant, siliqua per plant, and seed per siliqua were recorded. The crop was harvested and seeds were manually isolated, dried, and stored for further analysis.

Determination copper

The copper content in soil and plant parts (root, shoot, and seed) was measured by atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS). The post-harvest soil was collected and after oven drying, 1 g soil was digested on a hot plate in fume hood at 80 °C in 15mL aqua regia till the mixture become transparent. The aqua regia was prepared by mixing 35% HCl and 70% high-purity HNO3 in a ratio of 3:1, respectively. The root, shoot, and seed were grinded in electric blender. Each sample (0.25g) was mixed in a freshly prepared acidic solution (HClO4, H2SO4, and HNO3 at a ratio of 0.5: 1: 5). The samples were digested until the solution become transparent and the final volumes was made 50 mL by distilled deionized water. After filtering the solution through Whatman filter paper 42, the filtrate was analyzed through atomic absorption spectrometer (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) for the determination the amount of Cu in soil samples and plant material. The bioaccumulation factor (BAF) and translocation factor (TF) were calculated by using the following equations.

BAF = Concentration of Cu in plant tissues/Concentration of Cu in the soil

TF = Concentration of Cu in shoot and seeds/Concentration of Cu roots

Estimation of total protein, SOD, and POD

Fresh leaves were collected at fruiting stage, rinsed with distilled water, chopped, and pasted in mortar pestle in pH 7 phosphate buffer. The transparent solution was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was used for the estimation of total protein content, SOD, and POD activities. Total soluble protein in supernatant was measured followed the methodology reported by Lowry et al.25.

For determination of superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity, the method reported by Ullah et al.26 was employed. 200 μL of the reaction mixture (20 μL EDTA, 20 μL methionine, 20 μL NBT, 78 μL phosphate buffer, 2 μL riboflavin) and 60 μL plant sample was poured in 96 well plate. Blank was prepared by mixing all the chemicals except plant supernatant in the same quantity. Absorbance was measured at 560 nm using a micro-plate reader after seven min incubation of mixture in fluorescent light.

POD activity in shoots supernatant was determined by the method of Lagrimini27. Reaction mixture (40 μL guaiacol 100mM, 100 μL dH2O, 20 μL H2O2 27.5 mM, and 40 μL KH2PO4 buffer 50 mM) of 200 μL was poured in 96 well plate and 20 μL of plant extract was added. Reaction mixture without extract was used as control. Absorbance was measured using a micro-plate reader at 470 nm wavelength.

Biological profile of root and shoot

At the time of fruit collection, roots and shoots were also collected, dried, and powdered in electric blender. The sample powder was suspended in 1 mL dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in eppendorf tubes and kept at room temperature. After 24 h, the mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was used for the biochemical profiling.

Total phenolic content (TPC) were determined by the method of Astill et al. (2001). 20 μL of the samples, standard or blank i.e. sample, Gallic acid, or DMSO were transferred to each well of 96 well plates. In each well, 90 μL of 10 times diluted freshly prepared FC (Folin– Ciocalteu) reagent was added. The plates were incubated at room temperature for 5 min and then 90 μL of Na2CO3 solution was added to reaction mixture. The plates were then incubated for 1 h and absorbance was measured at 650 nm by using microplate reader.

Total flavonoid contents (TFC) were determined using the method as described by Almajano et al. (2008). Test sample20 μL, standard and blank were poured in the 96 well microplate and 10 μL of 10% aluminum chloride solution was added. Thereafter 10 μL of potassium acetate (1 M) solutions was added and the final volume was raised up to 200 μL by adding 160 μL of distilled water. The plate was incubated at room temperature for 30 min and optical density of samples was measured at 415 nm by microplate reader (Bioteck, USA).

The free radical scavenging activity of test sample against DPPH was determined using procedure described by Sajjad et al., (2021). 10 μL of test sample, standard and blank were mixed with 190 μL of DPPH solution in the 96 well microplate. The reaction mixture was incubated in dark for 1 h at 37°C. The optical density of the samples was measured at 517 nm using microplate reader. Percent inhibition of test sample was calculated using the following formula: Where: A= O.D of DPPH solution with sample; B= O.D of negative control (containing the reagent except the sample).

Total antioxidant activity (TAC) of roots and shoots of soybean and sesame plants was evaluated using protocol described by Sajjad et al. (2021). In TAC assay, 100 μL stock solution/test samples were added to Eppendorf tubes and 900 μL of TAC reagent (H2SO4, NaH2PO4.H2O, (NH4)6Mo7O24.4H2O) was then added and mixed thoroughly. The tubes were then incubated at 95 °C for 90 min. After incubation, the reaction mixtures were cooled at room temperature and then 200 μL of uniformly mixed solution were transferred to 96 well plates. The absorbance was measured at 630 nm by using micro plate reader.

Total reduction potential (TRP) of the test samples was evaluated according to the procedure described by Sajjad et al. (2023). For TRP assay, 100 μL of the test samples was mixed with 200 μL of phosphate buffer (0.2 M, pH 6.6) and 250 μL of 1% potassium ferricyanide solution. The reaction mixtures were then incubated for 20 min at 50⁰C. After incubation, the reaction mixture was acidified with 200 μL of 10% trichloroacetic acid. The resulting mixtures were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. 150 μL of supernatant layer of each centrifuged mixture was transferred to 96 well microplates and mixed with 50 μL of 0.1% ferric chloride solution. The optical density was measured at 630 nm using microplate reader. The results were expressed as μg Ascorbic acid equivalent per mg extract (μg AAE/mg extract)

Measurement of oil content

The 15 g seeds were oven-dried for 5 h at 50°C. The oil content was measured via non-destructive technique employing NMR analyzer (Newport 400 of Oxford Analytical Instruments) having a coil assembly of 40 mL. The seed were placed in sample holder and the oil content was recorded as percent oil present in the seeds.

Oil extraction and Estimation of free fatty acid (FFA) contents in E. sativa oil

The seed were washed with distilled water and dried in oven at 70 °C for 12 h. The oil was extracted through electrical expeller. The extracted was store for biodiesel production and further analysis.

Aqueous acid-base titration was used to determine the free fatty acid content in the oil extracted from E. sativa seeds. Blank and sample titrations were carried out. To perform blank titration, 0.025M KOH solution (0.14 g KOH in 100 mL distilled H2O) was poured in a burette. Isopropyl alcohol (10 mL) was taken in a conical flask and 2-3 drops of phenolphthalein indicator (0.5g phenolphthalein in 50% ethanol) and titrated against 0.025M KOH till the solution become dusky and turned pink indicating the endpoint of the reaction. At this point, the used volume of KOH was noted. For sample titration, isopropyl alcohol and oil were taken at a ratio of 9:1 in a conical flask and 2-3 drops of phenolphthalein indicator was added. The mixture was titrated against 0.025M KOH till the end point and used volume KOH was noted. The experiments for both blank titration and sample titration were carried out thrice to find average volume of KOH used in titrations. The following equation was used to determine the free fatty acid (FFA) content of E. sativa crude oil28.

where,

A= Volume used in Sample titration, B= Volume used in Blank titration, C= Mass of KOH in g/L

V= total volume of oil used

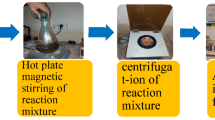

Biodiesel production

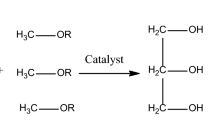

Before transesterification reaction, 1% KOH as catalyst was mixed well with methanol. The preheated E. sativa oil was mixed with methanol at 6:1 and subjected to stirring for 3 h at 65˚C for transesterification reaction. The mixture of biodiesel was allowed to stand overnight to separate biodiesel from catalyst and glycerin layer. The crude biodiesel was isolated and washed with distilled water to remove impurities such as CH3OH, KOH, and glycerin. These impurities absorbed into water, settle down, and leave pure biodiesel at the top. This process was repeated until clear water appeared29,30. This procedure of biodiesel production was employed for the oils extracted from treated and non-treated E. sativa seeds (Figure 2). The percent biodiesel yield was calculated using the following equation.

Where, \({m}_{1}\) is the mass of biodiesel produced, and \({m}_{2}\) is the mass of oil samples used.

Fatty acid (R1COOH) + Alcohol (ROH) ⇋ Ester (R1COOR) + Water (H2O)

Triglyceride + R1OH ⇋ Diglyceride + RCOOR1

Diglyceride + R1OH ⇋ Monoglyceride + RCOOR1

Monoglyceride + R1OH ⇋ Glycerol + RCOOR1

Generalize equation for transesterification of triglycerides.

Determination of fuel properties

The fuel properties of Eruca sativa biodiesel viz pour point, cloud point, flash point, viscosity, density, sulfur content, ash analysis, and acid value were determined using standard procedures of American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) (Table 3). These properties were compared with International Standards of Biodiesel i.e., European (EN-14214), American (ASTM D-6751), and Chinese GB/T 20,828 standards.

For the determination of pour point, the biodiesel was kept at room temperature for 24 h. After that, the biodiesel was poured into a test jar until its level reached a marked line at 5.5 cm above the bottom. The jar was sealed with cork and a thermometer was inserted in such a manner that its bulb remains 3 mm below the marked line, and the temperature was recorded. The jar was kept in jacket, preventing contact between the jacket and jar through a gasket. For observation, the jar was held horizontally for 5 s. The observation of flowing ability of biodiesel was initiated at a temperature at least 9 °C above the anticipated pour point. The biodiesel was allowed to cool until it completely ceased to flow, determining the pour point.

For recording cloud point, 10 cm3 biodiesel was taken in 100 cm3 beaker and kept in deep freezer. The biodiesel sample was examined at intervals and the temperature was recorded when the bottom of the beaker became hazy.

Flash point of the biodiesel was measured using automated Pensky Martens closed cup apparatus, for which the temperature range was set between 60-190 °C. The biodiesel sample was filled in a brass test cup and the lid was closed. The sample was heated and stirred. The ignition source was introduced at regular interval into the test cup with concurrent interruption of stirring, till the flash is detected, which spread throughout the cup. The temperature was recorded at the appearance of flash.

Redwood viscometer was used for the determination of viscosity of biodiesel. Viscosity value is the time needed for 50 ml biodiesel to come out of viscometer at standard temperature. The biodiesel was poured in to viscometer cup, heated electrically, and the pressure was kept constant. The time for the flow of 50 ml biodiesel was recoded at 40 °C.

The density of the biodiesel sample was determined through digital density analyzer (PAAR, DMA 38). The biodiesel sample (0.7 mL) was poured in to an oscillating sample tube and the density was measured by change in the mass of oscillating tube which altered the oscillating frequency.

The amount of sulfur in biodiesel was estimated by energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (EDXRF) (OXFORD, Model Lab-X3000). The biodiesel sample was placed in X-rays beam and the resultant excited rays were measured followed by comparison with X-rays count obtained from standards in the concentration ranges of 0.015-0.1 % and 0.1-5.0 %.

For the determination of ash content, 10 g biodiesel sample was ignited at 800 °C in dry and pre-weighed silica crucible until only ash was left. The crucible was allowed in a desiccator at room temperature and weighed. The difference between the weight of crucible before and after ignition was used to calculate the ash percentage of the original biodiesel mass.

The acid value was estimated by dissolving 10 g of biodiesel in a 30 cm3 mixture of isopropanol and toluene containing small amount of water. This solution was titrated against KOH to the end point as indicated by pink color due to phenolphthalein indicator.

Characterization of biodiesel

FT-IR spectra of E. sativa oil and biodiesel were attained on Burker-Platinum-ATR spectrometer at a scanning rate of 15 at 1cm−1 to analyze their functional groups and structural arrangement. A drop of oil and biodiesel was placed directly on spectrometer and the spectra were recorded in a wavenumber range of 4000-500 cm−1.

The fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) profile of biodiesel was determined by GC-MS through QP2010 Plus spectrometer fitted with capillary column of 0.2 µm thickness, length of 30 m, and, inner diameter of 0.2 µm. The FAMES were identified by a search of NIST17R.lib and NIST17M2 standard mass spectrum database. High purity (99.99%) helium gas was used as carrier at a flow rate of 1.5 mL/min. The injection temperature was set as 250 °C, whereas interface temperature was kept as 280°C. The oven temperature was kept at 50 °C with a hold time of 5 min and the scan range was m/z 40-800.The biodiesel sample (1 µL) with a split ratio of 20:1was injected and the spectra were obtained after complete scanning of biodiesel.

1H and 13C NMR spectra of E. sativa biodiesel were recorded at 298 K on Bruker-Avance 300 MHz spectrometer. Tetramethylsilane (TMS) and Deuterated chloroform (CDCl3) were used as internal standard and solvent, respectively. After vertexing with CDCl3, the biodiesel was transferred to NMR sample tube to record NMR spectra. 1H (300MHz) spectra were recorded at a flip angle of 30°, recycle delay of 1 s, scan number of 10, and pulse duration of 30°. 13C NMR (75MHz) spectra were recorded at a flip angle of 30°, recycle delay of 1.89 s, scan number of 10, and pulse duration of 30°.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were carried out in triplicate. The field experiment was performed in a Randomized Complete Block Design (RCBD) to evaluate the effect of CuS NPs and CuSO4 on the agronomic parameters and oil content of Eruca sativa. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine significant difference between treatments. To compare treatment, the results were further analyzed statistically through HSD test at P≤ 0.05 using STATISTIX 8.1® (Hill and Lewicki 2006).

Results and discussion

Characterization of CuS NPs

SEM images present roughly spherical forms of CuS NPs that were moderately aggregated (Figure 3). Chemical approaches for synthesis of NPs present good morphological products, less aggregated, and smaller size. Energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) analysis percents composition of Cu and S elements in CuS NPs. The surface showed 48.51% Cu and 39.56% S by weight. The precent composition reflects atomic arrangement and purity of NPs31.

The XRD analysis of CuS NPs revealed diffraction peaks at 27.68º, 29.23º, 31.78º, 47.73º, 52.67º, and 59.21º. These diffraction peaks align with lattice planes (101), (102), (103), (107), (108), and (116), respectively (Figure 3). JCPDS card 06-0464 support the diffractogram and corresponds to hexagonal crystal lattice of CUS NPs (32,33,34. The average size calculated by equation determines 4.32 nm NPs.

FTIR peaks presented broad band in the region of 3450 cm−1 corresponds to the stretching vibrations of the OH group and can be attributable to adsorbed water or surface-bound hydroxyl ions. The bands located at 1600 cm−1 and 1384 cm−1 represent the O–H bending mode that indicates Cu-O-H structure (Figure 3). A band at 1124 cm−1 suggests asymmetric stretching vibration of SO4- species whereas the band at 617 cm−1 can be attributed to Cu-S stretching vibrations34,35.

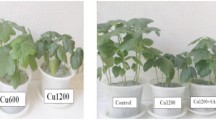

Growth and yield attributes of Eruca sativa

Physical growth and yield parameters of E. sativa exposed to CuS NPs and CuSO4 under field environment are shown in Table 4. The application of CuS NPs markedly increased the growth and yield parameters of E. sativa. CuS NPs improved the root length (20.23%), shoot length (21.17%), branches per plant (45.64%), and dry weight per plant (49.46%) as compared to untreated control plants. Similarly, yield parameters such as siliqua per plant (48.68%), seeds per siliqua (18.16%), and oil percentage (18.27%) also increased in response to CuS NPs with respect to control plants. Although, the application of CuSO4 also improved in the aforementioned parameters compared to control, yet lower than CuS NPs treated plants. Cu is an essential micronutrient for plant and acts as cofactor for different enzymes, photosynthetic machinery, and cytochrome oxidase of the respiratory electron transport chain. Plants produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) in response to Cu stress36,37. Rameen et al.15 reported increased growth and yield parameter in Brassica napus in response Cu NPs at below threshold concentration. Cu NPs increased the number pod per plant in Glycine max upon exposure to soil applied Cu NPs38. However, some studies have shown that Cu NPs reduced root and shoot length, water content, and biomass in Lactuca sativa and wheat39,40,41. The S component of CuS NPs mitigated the Cu toxicity in the current study as various studies revealed that sulfur application alleviates heavy meat toxicity42,43,44. The exact mechanism through which Cu NPs improve agronomic parameters is still to be uncovered. However, it is assumed that Cu interferes with plant biochemical processes and enzymes that are involved in biochemical processes including lipid production. Sulfur plays important role in the synthesis of oil, protein, vitamins, and aromatic compounds in plants. It is also a component of three important amino acids,cystine, cysteine, and methionine. Enhanced oil content in E. sativa seed may also be attributed to the role of S in oil biosynthesis.

Elemental analysis

The roots of E. sativa grown in presence of CuS NPs accumulated highest Cu content (54.46±1.63 mg/kg) followed by shoot (34.53±1.72 mg/kg) and seeds (9.4±0.47 mg/kg). Cu accumulation was observed in the same manner in E. sativa treated with CuSO4 (Table 5). As the roots are in direct contact with soil seems to accumulate more amount of Cu whereas seed being farthest from root and develop later in the life tends to accumulate the least amount of Cu. Moreover, dissolution of metals from nanoparticles also promotes uptake of Cu by roots45. The less accumulation of Cu in salt treated plants as compared to NPs treated plants points that the Cu ions released from salt were less available either due to leaching or binding with other molecules while Cu slowly dissolute from NPs conforming Cu availability throughout the life. These findings are aligned with Ogunkunle et al.46, where they found higher Cu concentration in the root followed by leaves and seed of cowpea upon exposure to Cu NPs.

Bioaccumulation factors (BF) ranged from 17.47 to 37.59, whereas translocation factors (TF) ranged from 0.57 to 0.8 (Table 5). TF was determined to assess the capability of E. Sativa for Cu translocation from root to shoot. It is evident from the results that highest TF was observed in CuS NPs treated plants suggesting high translocation efficiency of E. sativa. Consequently, it is concluded that translocation capability of E. sativa increased with increase in the amount of Cu in the soil. Nanoparticles accumulate in roots and translocated to the shoot and seeds47,48. NPs type, concentration, size surface charge, ion dissolution efficiency as well as plant species affect the absorption, bioaccumulation, and translocation of metals in plants49,50,51,52. Larger NPs struggle to pass through tiny pores in the cell wall53 whereas smaller size NPs have better potential to transport54. Nanoparticles adhere to root surface, enter the cell wall and move between cell wall through plasmodesmata and transported shoot via xylem53. Wang et al.55 reported the transport of Cu NPs from root to shoot through xylem.

Biochemical analysis of Plants

The protein content in E. sativa treated with CuS NPs increased (175.16±8.5 mg/g FW) as compare to untreated control plants (63.88±3.19 mg/g FW). Similar results were noted for enzymatic antioxidants, SOD and POD in response to externally applied CuS NPs (Table 6). Moreover, non-enzymatic antioxidants, phenolics and flavonoids also increased in the root and shoot of E. sativa upon exposure to CuS NPs. The root of E. sativa showed an increase of TPC 44.26% while shoots depicted 15.33% increase of TPC as compared to control plants. Similarly, TFC increased by 11.62% and 8.04% in roots and shoots, respectively as contrast to control plants. The root and shoot of E. sativa also showed increase of DPPH free radical scavenging activity, TAC and TRP upon exposure to CuS NPs (Table 7). A slight increase in the above parameters was also observed in response to CuSO4 treatment. However, this increase was negligible when compared with CuS NPs treatments.

Faizan & Hayat56reported that metallic NPs enhance protein content in tomato by interfering in transcription and translation processes. In another study, Salama57, found that Ag NPs augmented protein content in common bean and corn up 60 ppm and decreased above this dose. A concentration dependent increase in the amount of protein was also observed by Leopold et al.58 in soybean upon exposure to metallic nanoparticles. At cellular level, SOD and POD provide the first defense mechanism against oxidative damage59. SOD catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide radicals O2. to molecular oxygen and hydrogen peroxide. POD being a key enzyme in antioxidant enzyme convert hydrogen peroxide to H2O and O2. In the current study there was a clear increase in the SOD and POD activities of the plant treated with CuS NPs. Similar results have been reported by Kim et al60 in Cucumis sativus. A significant increase in SOD gene expression was also observed by Nair and Chung61 in pea upon treatment with different concentration of Cu NPs. TPC and TFC are non-enzymatic antioxidants which protect the plants against stresses. They affect plant growth and development through the life62,63. The amount of TPC and TFC augmented in Brassica64,65, Abelmoschus esculentus66, Ocimum basilicum (Nazir et al. 2012), cucumber Zhao et al.67, and rice68 upon exposure to different metallic NPs including Cu NPs. The variation in the amount of TPC and TFC in response to NPs is possibly due to ROS production. Still, this variation depends on the type of NPs, mode of application, and age and specie of the plant. Upon entry in to the cell, these NPs cause oxidative stress by interacting with cell organelles69. The plant defense system gets activated and produces antioxidant such as phenolics and flavonoids under stress70. In the current study, the increase in DPPH free radical scavenging activity, TAC, and TRP under the elicitation of CuS NPs shows exertion of oxidative stress that do not negative effect plant growth and yield as depicted by agronomic parameters. ROS produced in response to stress may also act as signaling molecules71. The increase in antioxidant activities indicate strong detoxification mechanism that protect the plant cells from eternally applied Cu stress.

Biodiesel synthesis and yield

The oil obtained from E. sativa plants seeds were converted to biodiesel. Prior to biodiesel synthesis, the free fatty acid (FFA) was determined and found to be 0.31 mg KOH/g. The quality and yield of biodiesel directly depends on amount of FFA which affect the rate of biodiesel synthesis. The FAA value up to 3% is considered appropriate for efficient conversion of oil to biodiesel in a single step transesterification reaction. The FFA content above this value leads to saponification which makes the separation difficult72,73. Owon et al.74 reported 1.13% free fatty acids content in rocket seed oil. Our value of FFA content is within the safe limit for single step transesterification reaction. The percent yield of biodiesel was 85.16, 85.31 and 84.98 for the oil extracted from control, CuSO4, and CuS NPs treated E. sativa plants, respectively. Tariq et al.75 also observed 83.3% yield in a study using rocket seed oil as feedstock for biodiesel production.

Fuel properties

The fuel properties of E. sativa oil biodiesel are presented in table 6 and compared with international standard i.e., American (ASTM- 6751), European (EN- 14214), China (GB-T) and published studies. The determination of fuel properties is considered essential before applications in diesel-based engines.

The lowest temperature at which a fuel is able to flow is pour point while the temperature at which crystals formation starts to form precipitate is known as cloud point. The pour points were found to be between −4.01°C to −4.32°C, while cloud points were from 2.93 oC to 3.3 oC (Table 8). These values are within the recommended limits for standard biodiesel. For low temperature operation of fuel, pour point and cloud points are commonly used76. The parameters show the least temperature at which a fuel ignites efficiently. The low pour and cloud points in this study indicate that E. sativa biodiesel can be used in a moderate cold climate tropical country like Pakistan.

Flash point is the temperature at which the fuel vaporizes and is a significant parameter in safety, handling, and storage of fuel and inflammable substances. The flash points of E. sativa biodiesel obtained from seeds of plants of different treatments are close to each other and are well in the range of international standards (Table 6). Viscosity is another important feature of fuel as both low and higher viscosity affect the proper operation of engine. It influences the atomization of biofuel after injection to diesel engine. High viscosity results in incomplete combustion due to poor oxygen supply which lead to deposition in the diesel engines (Knothe and Steidley, 2005) while low viscosity causes low combustion due to low penetration which lead to black smoke emission. In this study, the viscosity of biodiesel obtained from seeds of plants treated with CuS NPs was little bit higher than control (Table 8). These values are also in the range of international standards for biodiesels.

Density of biodiesel affects the atomization of fuel during combustion and engine performance77. The densities of biodiesel of E. sativa seed oil were found same and comparable to international standard of biodiesel (0.86–0.90 g/m3) (Table 8). The sulfur content is present in biodiesel primarily due to the existence of phospholipids in oil78. The sulfur content was observed 0.017 for control,0.011 for CuSO4; and 0.013 wt.% for CuS NPs treated E. sativa oils that also lies within the ideal range of international standards. Ash content indicates the presence of inorganic contaminants in biodiesel. During combustion process, these inorganic compounds oxidize quickly and lead to ash formation. The ash accumulates in engine that reduces efficiency of engine79,80. The results in table 6 show that ash content of E. sativa biodiesel lies within the recommended international standard range.

The acid value represents the quantity of free fatty acid in biodiesel. High acid number (≥ 0.50 mg KOH g−1) may negatively affect engine performance due to corrosion. The acid value in current study were observed to be in the range of 0.14-0.19 mg KOH g−1, which are comparable to international standard for biodiesel (Table 8).

Similar result for fuel properties of biodiesel synthesized from Eruca sativa seed oil biodiesel is reported by81,82, and Tariq et al.75.

Characterization of biodeisel

FT-IR analysis of Eruca sativa oil and biodeisel

FT-IR analysis was used to identify the functional groups and bands attributed to different bending vibrations and stretching in the oil and biodiesel. Both E. sativa oil and biodiesel showed nearly similar FT-IR spectra, yet differences were observed in both spectra (Figure 4 and 5). The peaks in oil at 3312.86 cm−1 and 1635.85 cm−1 corresponding to O-H stretching vibration and C=C stretching respectively, disappeared in biodiesel, and the emergence of new peaks at 3010.38 cm−1 (stretching vibration of CH), 1426.32 cm−1 and 722.24 cm−1 (bending vibrations of CH2) is indicative of oil conversion to biodiesel83. The absorption band of oil in the regions of 1744.91 cm−1 and 1160.53 cm−1 shifted to 1740.79 cm−1 and 1168.76 cm−1 in biodiesel (Figure 4 and 5). Similar result of peaks disappearance in the oil spectra, emergence of new spectra in biodiesel, and shifting of peaks in E. sativa oil and biodiesel were observed by81 and Tariq et al.75. The biodiesel FT-IR spectra confirm successful conversion of E. sativa oil to biodiesel. It is concluded that CuSO4 and CuS NPs treatment did not affect chemical structure of oil and biodiesel, and its performance as fuel.

GC-MS analysis of biodiesel

The fatty acid methyl ester (FAMEs) composition of E. sativa biodiesel was determined through GC-MS. The GC-MS analyses showed that the biodiesel composition E. sativa oil is not affected markedly by CuS NPs and CuSO4 treatments. The results indicate that FAMEs remain consistent across all treatments indicating that primary fatty acid profile remains intact despite the salt or NPs treatment. However, biodiesel obtained from oil extracted from E. sativa seeds grown with CuS NPs lead to variations in the relative abundances (% concentration) of specific compounds (Table 9; Figure 6). GC-MS identified up to sixteen compounds in E. sativa biodiesel prepared from the oil extracted from control and treated plants. Some of the compounds showed slight variation while other indicated marked variation in percent concentration. For instance, the concentration of Octanoic acid, methyl ester was 43% in control oil and 1.13% in E. sativa oil treated with CuS NPs. Similarly, the percent concentrations of Nonanoic acid, 9-oxo-, methyl ester, 2,4-Decadienal, (E, E)-, and 2,4-Decadienal were 3.74%, 5.37%, and 11.25%, respectively, in control oil, while 0.18%, 0.16%, and 0.34% respectively, in oil of CuS NPs treated plants (Table 9). Moreover, Lauric acid, methyl ester (16.06%) was present in the biodiesel synthesized from the oil extracted from E. sativa seeds oil treated with CuS NPs while absent in control and CuSO4 treated plant oil. CuS NPs treatment revealed a more pronounced impact on improving unsaturated FAMEs, which may enhance the quality of biodiesel in the term of oxidative stability and cold flow property84. Meher et al.85 reviewed that transesterification reaction for biodiesel production is affected by molar ratio of oil to alcohol, alcohol type, reaction time and condition, reactants purity, catalyst, and temperature.

NMR analysis

The biodiesel was characterized by 13C and 1H NMR spectroscopy. In 1H NMR, the methoxy protons resonance singlet at 3.64 ppm confirms the presence of methyl esters in E. sativa biodiesel (Figure 7). The appearance of methoxy proton and CH2 proton are the peaks in biodiesel for the confirmation of methyl esters. The peak present at 0.84 ppm represents terminal CH3 proton, an intense signal at 1.25 ppm represents CH2 proton of carbon chain, and signals at 1.55 ppm and 5.3 ppm are related to β-carbonyl methylene protons and olefinic hydrogen, respectively. Similar 1H NMR peaks in E. sativa biodiesel were observed by Shah et al.86 and Tariq et al75. The spectrum for 13C NMR of E. sativa oil biodiesel is presented in Figure 8. The resonance signals at 51.3 ppm and 174 ppm indicating ester carbonyl (-COO-) and C-O, respectively, confirms the conversion of E. sativa oil to biodiesel. Peak in the range of 127-131 ppm attributes to sp2 hybridized carbons of olefinic double bonds, showing unsaturation methyl eaters. The peaks around 22-34 ppm represent C-C bonds in fatty acid chains, indicating the presence of long chain fatty acid in E. sativa oil biodiesel. Similar peaks in E. sativa methyl esters were found by Tariq et al.75 and Shah et al.86. It is noteworthy that the NMR peaks across all treatments remained consistent, indicating that CuS NPs and CuSO4 treatment did not induce significant alteration in the biodiesels structure and resulting performance.

Conclusion

The study indicates the substantial role of CuS NPs in improving plant growth, yield and biochemical attributes under field condition. The soil application of NPs enhanced agronomic parameters, oil percentage and antioxidant activities. Linseed oil being a feedstock for biodiesel, the improved oil percentage ultimately leads to enhanced biodiesel production. Comprehensive FT-IR, NMR, and GC-MS analysis of the biodiesel synthesized from oil extracted from treated and untreated plant seeds did not show significant alteration in composition. Moreover, fuel properties lie within international standard for biodiesel, demonstrating the feasibility of biodiesel produced from CuSO4 and CuS NPs treated plants. These outcomes highlight the dual importance of CuS NPs in agriculture and biofuel production and offer a sustainable approach to agricultural practices and renewable energy production. However, further research is needed to evaluate the long term ecological and environmental impact of metallic nanoparticles application in agriculture. Although, CuS NPs improved various plant parameters, it is important to evaluate the possible risk associated with NPs application in the cultivation of plants. The long run effect of NPs on the environment needs to be evaluated and further studies may be carried out on NPs accumulation in the soil and water. From literature, it has been ascertained that NPs may remain in the environment and affect the soil microbiota and productivity of crop. The present study may be considered as optimal, yet further studies need to be carried out in order to find that NPs application in agriculture is safer for food chain.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed and materials used during this study are included in this article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

Roy, S. & Rhim, J. W. Fabrication of copper sulfide nanoparticles and limonene incorporated pullulan/carrageenan-based film with improved mechanical and antibacterial properties. Polymers 12(11), 2665 (2020).

Sharma, R. K. & Agrawal, M. Biological effects of heavy metals: an overview. J. Environ. Biol. 26(2), 301–313 (2005).

Van Assche, F. & Clijsters, H. A biological test system for the evaluation of the phytotoxicity of metal-contaminated soils. Environ. Pollut. 66(2), 157–172 (1990).

Yruela, I. Copper in plants. Brazil. J. Plant Physiol. 17, 145–156 (2005).

Xiong, T. et al. Copper oxide nanoparticle foliar uptake, phytotoxicity, and consequences for sustainable urban agriculture. Environ. Sci. & Technol. 51(9), 5242–5251 (2017).

Wang, J. et al. Small particles, big effects: How nanoparticles can enhance plant growth in favorable and harsh conditions. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 66(7), 1274–1294 (2024).

Jia, Y., Klumpp, E., Bol, R. & Amelung, W. Uptake of metallic nanoparticles containing essential (Cu, Zn and Fe) and non-essential (Ag, Ce and Ti) elements by crops: A meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53(16), 1512–1533 (2023).

Xiao, Y. et al. Copper accumulation and physiological markers of soybean (Glycine max) grown in agricultural soil amended with copper nanoparticles. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 229, 113088 (2022).

Imperiale, D. et al. Interaction of hyperaccumulating plants with Zn and Cd nanoparticles. Sci. Total Environ. 817, 152741 (2022).

Ngo, B. Q. et al. Effects of nanocrystalline powders (Fe, Co and Cu) on the germination, growth, crop yield and product quality of soybean (Vietnamese species DT-51). Adv. Nat. Sci. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 5, 015016. https://doi.org/10.1088/2043-6262/5/1/015016 (2014).

Kaleem, Z. et al. Harnessing the potential of copper-based nanoparticles in mitigating abiotic and biotic stresses in crops. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31(50), 59727–59748 (2024).

Van Nguyen, D. et al. Copper nanoparticle application enhances plant growth and grain yield in maize under drought stress conditions. J. Plant Growth Regul. 41(1), 364–37s (2022).

López-Vargas, E. R. et al. Foliar application of copper nanoparticles increases the fruit quality and the content of bioactive compounds in tomatoes. Appl. Sci. 8(7), 1020 (2018).

Noman, M. et al. Green copper nanoparticles from a native Klebsiella pneumoniae strain alleviated oxidative stress impairment of wheat plants by reducing the chromium bioavailability and increasing the growth. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safety 192, 110303 (2020).

Rameen, S. et al. Foliar application of silver (Ag-NPs) and copper (Cu-NPs) nanoparticles enhances phenotypic traits and oil quality in Brassica napus L. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 27618 (2024).

Yuan, H. et al. Sulfur nanoparticles improved plant growth and reduced mercury toxicity via mitigating the oxidative stress in Brassica napus L. J. Cleaner Prod. 318, 128589 (2021).

Ramazzina, I. et al. Fresh-cut eruca sativa treated with plasma activated water (PAW): evaluation of antioxidant capacity, polyphenolic profile and redox status in Caco2 Cells. Nutrients 14(24), 5337. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14245337 (2022).

Jaafar, N. S. & Jaafar, I. S. Eruca sativa Linn.: Pharmacognostical and pharmacological properties and pharmaceutical preparations. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 12(3), 39–45 (2019).

Fratianni, F. et al. Eruca sativa might influence the growth, survival under simulated gastrointestinal conditions and some biological features of Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus plantarum and Lactobacillus rhamnosus strains. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 15(10), 17790–17805. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms151017790 (2014).

Atabani, A. E. et al. Investigation of physical and chemical properties of potential edible and non-edible feedstocks for biodiesel production, a comparative analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 21, 749–755 (2013).

Arumugam, A. & Ponnusami, V. J. R. E. Biodiesel production from Calophyllum inophyllum oil a potential non-edible feedstock: An overview. Renew. Energy 131, 459–471 (2019).

Roschat, W., Siritanon, T., Yoosuk, B. & Promarak, V. Biodiesel production from palm oil using hydrated lime-derived CaO as a low-cost basic heterogeneous catalyst. Energy Convers. Manag. 108, 459–467 (2016).

Al-Jawad, S. M., Taha, A. A., & Muhsen, M. M. Preparation and characterization of CuS nanoparticles prepared by two-phase colloidal method. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series (Vol. 1795, No. 1, p. 012053). IOP Publishing 2021

Khan, K. et al. Temporal climatic comparison of various narc sunflower hybrids based on their yield stability. J. Plant Biochem. Physiol. 11, 281 (2023).

Lowry, O. H., Rosebrough, N. J., Farr, A. L. & Randall, R. J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 193(1), 265–275 (1951).

Ullah, M. A. et al. Effect of ultraviolet-C radiation and melatonin stress on biosynthesis of antioxidant and antidiabetic metabolites produced in in vitro callus cultures of Lepidium sativum L. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20(7), 1787 (2019).

Lagrimini, L. Plant peroxidases: Under-and over-expression in transgenic plants and physiological consequences. Plant Peroxidases 1990, 59–69 (1980).

Shaheen, A. et al. Assessing the potential of different nano-composite (MgO, Al2O3-CaO and TiO2) for efficient conversion of Silybum eburneum seed oil to liquid biodiesel. J. Mol. Liquids 249, 511–521 (2018).

Gumahin, A. C. et al. Response surface optimization of biodiesel yield from pre-treated waste oil of rendered pork from a food processing industry. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 6, 1–13 (2019).

Hoque, M. E. & Gee, L. P. Biodiesel from plant resources—sustainable solution to ever increasing fuel oil demands. J. Sustain. Bioenergy Syst. 3(03), 163 (2013).

Chakraborty, S. Preparation and characterization of CuS nanoparticles. Biophys. Rev. Lett. 19(02), 197–208 (2024).

Lafta, K. T., & Salman, T. A. (2024). Green synthesis, characterization of copper sulfide nanoparticles and antibacterial activity evaluation. Iraqi Journal of Science, 6277-6287.

Garcia, A. G. et al. Hydrophobic CuS nanoparticle entrapment and release from lignin-derived nanoparticles. J. Nanoparticle Res. 27(6), 149 (2025).

Abdulwahab, A. M. et al. Synthesis, characterization, and anti-cancer activity evaluation of Ba-doped CuS nanostructures synthesized by the co-precipitation method. RSC Adv. 15(6), 4669–4680 (2025).

Hammadi, M., Hummadi, E. H., & Sabah, R. Synthesis of cus nanoparticle and characterization, as well as investigation of their anticancer activity against a human breast cancer cell line. Journal of Pharmaceutical Negative Results 13(2) 2022

Asati, A., Pichhode, M. & Nikhil, K. Effect of heavy metals on plants: an overview. Int. J. Appl. Innov. Eng. & Manag. 5(3), 56–66 (2016).

Kasana, R. C., Panwar, N. R., Kaul, R. K. & Kumar, P. Biosynthesis and effects of copper nanoparticles on plants. Environ. Chem. Lett. 15, 233–240 (2017).

Yusefi-Tanha, E., Fallah, S., Pokhrel, L. R. & Rostamnejadi, A. Role of particle size-dependent copper bioaccumulation-mediated oxidative stress on Glycine max (L.) yield parameters with soil-applied copper oxide nanoparticles. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31(20), 28905–28921 (2024).

Hong, J. et al. Toxic effects of copper-based nanoparticles or compounds to lettuce (Lactuca sativa) and alfalfa (Medicago sativa). Environ. Sci.: Process. & Impacts 17(1), 177–185 (2015).

Trujillo-Reyes, J., Majumdar, S., Botez, C. E., Peralta-Videa, J. R. & Gardea-Torresdey, J. L. Exposure studies of core–shell Fe/Fe3O4 and Cu/CuO NPs to lettuce (Lactuca sativa) plants: are they a potential physiological and nutritional hazard?. J. Hazardous Mater. 267, 255–263 (2014).

Dimkpa, C. O. et al. Fate of CuO and ZnO nano-and microparticles in the plant environment. Environ. Sci. & Technol. 47(9), 4734–4742 (2013).

Lu, Y. et al. Effects of exogenous sulfur on alleviating cadmium stress in tartary buckwheat. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 7397 (2019).

Cao, Z. Z., Qin, M. L., Lin, X. Y., Zhu, Z. W. & Chen, M. X. Sulfur supply reduces cadmium uptake and translocation in rice grains (Oryza sativa L.) by enhancing iron plaque formation, cadmium chelation and vacuolar sequestration. Environ. Pollut. 238, 76–84 (2018).

Dixit, G. et al. Sulfur mediated reduction of arsenic toxicity involves efficient thiol metabolism and the antioxidant defense system in rice. J. Hazardous Mater. 298, 241–251 (2015).

Gao, X. et al. CuO nanoparticle dissolution and toxicity to wheat (Triticum aestivum) in rhizosphere soil. Environ. Sci. & Technol. 52(5), 2888–2897 (2018).

Ogunkunle, C. O. et al. Effects of manufactured nano-copper on copper uptake, bioaccumulation and enzyme activities in cowpea grown on soil substrate. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safety 155, 86–93 (2018).

Rico, C. M., Majumdar, S., Duarte-Gardea, M., Peralta-Videa, J. R. & Gardea-Torresdey, J. L. Interaction of nanoparticles with edible plants and their possible implications in the food chain. J. Agri Food Chem. 59(8), 3485–3498 (2011).

Tripathi, D. K. et al. An overview on manufactured nanoparticles in plants: uptake, translocation, accumulation and phytotoxicity. Plant physiol. Biochem. 110, 2–12 (2017).

Rajput, V. et al. Accumulation of nanoparticles in the soil-plant systems and their effects on human health. Ann. Agri. Sci. 65(2), 137–143 (2020).

Mittal, D., Kaur, G., Singh, P., Yadav, K. & Ali, S. A. Nanoparticle-based sustainable agriculture and food science: Recent advances and future outlook. Front. Nanotechnol. 2, 579954 (2020).

Kaphle, A., Navya, P. N., Umapathi, A. & Daima, H. K. Nanomaterials for agriculture, food and environment: applications, toxicity and regulation. Environm. Chem. Lett. 16, 43–58 (2018).

Yusefi-Tanha, E., Fallah, S., Rostamnejadi, A. & Pokhrel, L. R. Root system architecture, copper uptake and tissue distribution in soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) grown in copper oxide nanoparticle (CuONP)-amended soil and implications for human nutrition. Plants 9(10), 1326 (2020).

Iram, D., Sansi, M. S., Singh, P., Chandhni, P. R., Zanab, S., Rana, S., & Ali, S. A. Effect of metal oxide nanoparticles on biochemical pathways in plants. In Nanometal Oxides in Horticulture and Agronomy (pp. 19-49). Academic Press. 2023

Dietz, K. J. & Herth, S. Plant nanotoxicology. Trends Plant Sci. 16(11), 582–589 (2011).

Wang, Z. et al. Xylem-and phloem-based transport of CuO nanoparticles in maize (Zea mays L.). Environ. Sci. & Technol. 46(8), 4434–4441 (2012).

Faizan, M. & Hayat, S. Effect of foliar spray of ZnO-NPs on the physiological parameters and antioxidant systems of Lycopersicon esculentum. Pol. J. Nat. Sci 34(6), 87–105 (2019).

Salama, H. M. Effects of silver nanoparticles in some crop plants, common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) and corn (Zea mays L.). Int. Res. J. Biotechnol. 3(10), 190–197 (2012).

Leopold, L. F. et al. The effect of 100–200 nm ZnO and TiO2 nanoparticles on the in vitro-grown soybean plants. Colloids Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 216, 112536 (2022).

Fang, Y. Z., & Zheng, R. L. Theory and application of free radical biology. Beijing, Sciencex, 56-78. 2002

Kim, S., Lee, S. & Lee, I. Alteration of phytotoxicity and oxidant stress potential by metal oxide nanoparticles in Cucumis sativus. Water, Air, & Soil Pollut. 223, 2799–2806 (2012).

Nair, P. M. G. & Chung, I. M. The responses of germinating seedlings of green peas to copper oxide nanoparticles. Biologia plantarum 59(3), 591–595 (2015).

Bistgani, Z. E. et al. Effect of salinity stress on the physiological characteristics, phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of Thymus vulgaris L. and Thymus daenensis Celak. Ind. Crops Prod. 135, 311–320 (2019).

Cheynier, V., Comte, G., Davies, K. M., Lattanzio, V. & Martens, S. Plant phenolics: recent advances on their biosynthesis, genetics, and ecophysiology. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 72, 1–20 (2013).

Rehman, R. U. et al. Postponement growth and antioxidative response of Brassica nigra on CuO and ZnO nanoparticles exposure under soil conditions. IET Nanobiotechnol. 14(5), 423–427 (2020).

Zafar, H., Ali, A., Ali, J. S., Haq, I. U. & Zia, M. Effect of ZnO nanoparticles on Brassica nigra seedlings and stem explants: growth dynamics and antioxidative response. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 535 (2016).

Baskar, V. et al. A comparative study of phytotoxic effects of metal oxide (CuO, ZnO and NiO) nanoparticles on in-vitro grown Abelmoschus esculentus. Plant Biosyst.-Int. J. Deal. with all Asp. Plant Biol. 155(2), 374–383 (2021).

Zhao, L. et al. CeO2 and ZnO nanoparticles change the nutritional qualities of cucumber (Cucumis sativus). J. Agri. Food Chem. 62(13), 2752–2759 (2014).

Rico, C. M. et al. Effect of cerium oxide nanoparticles on the quality of rice (Oryza sativa L.) grains. J. Agri. Food Chem. 61(47), 11278–11285 (2013).

Hatami, M., Naghdi Badi, H. & Ghorbanpour, M. Nano-elicitation of secondary pharmaceutical metabolites in plant cells: A review. J. Med. Plants. 18(71), 6–36 (2019).

Berni, R. et al. Reactive oxygen species and heavy metal stress in plants: Impact on the cell wall and secondary metabolism. Environ. Exp. Botany 161, 98–106 (2019).

Ismail, A., Takeda, S. & Nick, P. Life and death under salt stress: same players, different timing?. J. Exp. Botany 65(12), 2963–2979 (2014).

Demirbas, A. Biodiesel from waste cooking oil via base-catalytic and supercritical methanol transesterification. Energy Convers. Manag. 50(4), 923–927 (2009).

Dorado, M. P. et al. An alkali–catalyzed transesterification process for high free fatty acid waste oils. Trans. ASAE 45(3), 525 (2002).

Owon, M. A., Noaman, M. A., Nour, E. D. & Osman, M. A. Chemical and technological studies on rocket (eruca sativa) seed oil: 1-characterization of rocket (eruca sativa) seed oil. J. Food Dairy Sci. 30(1), 383–395 (2005).

Tariq, M. et al. Identification, FT-IR, NMR (1H and 13C) and GC/MS studies of fatty acid methyl esters in biodiesel from rocket seed oil. Fuel Process. Technol. 92(3), 336–341 (2011).

Alamu, O. J., Waheed, M. A., & Jekayinfa, S. O. Alkali-catalysed laboratory production and testing of biodiesel fuel from Nigerian palm kernel oil. Agricultural Engineering International: CIGR Journal. 2007

Chhetri, A. B., Watts, K. C. & Islam, M. R. Waste cooking oil as an alternate feedstock for biodiesel production. Energies 1(1), 3–18 (2008).

Knothe, G. Analyzing biodiesel: standards and other methods. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 83(10), 823–833 (2006).

Hagenow, G., Reders, K., Heinze, H. E., Steiger, W., Zigan, D., & Mooser, D. Fuels. Handbook of diesel engines, 77-125. (2010)

Ferrari, R. A., Pighinelli, A. L. M. T. & Park, K. J. Biodiesel production and quality. Biofuel’s Eng. process Technol. 1, 221–240 (2011).

Fatima, A. et al. Synthesis of lipase-immobilized CeO2 nanorods as heterogeneous nano-biocatalyst for optimized biodiesel production from Eruca sativa seed oil. Catalysts 10(2), 231 (2020).

Mumtaz, M. W. et al. Biodiesel production using Eruca sativa oil: optimization and characterization. Pak. J. Bot 44(3), 1111–1120 (2012).

Safar, M., Bertrand, D., Robert, P., Devaux, M. F. & Genot, C. Characterization of edible oils, butters and margarines by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy with attenuated total reflectance. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 71, 371–377 (1994).

Knothe, G. Dependence of biodiesel fuel properties on the structure of fatty acid alkyl esters. Fuel Process. Technol. 86(10), 1059–1070 (2005).

Meher, L. C., Sagar, D. V. & Naik, S. N. Technical aspects of biodiesel production by transesterification—a review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 10(3), 248–268 (2006).

Shah, M., Tariq, M., Ali, S., Guo, Q. X. & Fu, Y. Transesterification of jojoba oil, sunflower oil, neem oil, rocket seed oil and linseed oil by tin catalysts. Biomass Bioenergy 70, 225–229 (2014).

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge NARC, Islamabad for providing their technical support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MZ and JK: conceptualization. JK, MZ, and MR: methodology. JK, and MA: data analysis. JK and MZ: writing—original draft preparation. MA and MZ: writing—review and editing. MZ and MA: visualization. MZ: supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to participate

Manuscript does not contain human related data therefore consent to participate is not required

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, J., Rukh, M., Ahmad, M. et al. Copper sulfide nanoparticles application under field condition increases Eruca sativa morpho-physiological response, yield, and biodiesel production for sustainable energy. Sci Rep 15, 36576 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20523-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20523-7