Abstract

This study introduces a novel topological descriptor, the second Davan index (SDI) based on weighted degree of molecular graphs. Its chemical significance is validated through QSPR modelling of octane isomers, where it exhibits superior correlation with physico-chemical properties such as entropy, acentric factor, density and molar volume, outperforming classical indices like the Sombor index, second hyper Zagreb index and redefined third Zagreb index. The second Davan index demonstrates enhanced isomer discrimination capability, as evidenced by its high sensitivity values compared to established descriptors. Further, bounds are established for connected graphs and closed form expressions are computed for standard graph classes and certain nanostructures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Graph theory finds profound applications across various scientific domains, with chemistry recognized as one of its most prominent beneficiaries. Within the scope of chemical graph theory, topological indices (TIs) serve as numerical descriptors that represent the molecular topology of compounds, aiding in the prediction of diverse physico-chemical and biological properties1,2,3.

Over recent decades, TIs have gained considerable attention in pharmacology, bio-inorganic chemistry, toxicity analysis and theoretical modelling4,5,6. Topological indices have played a pivotal role in the development of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) and Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) models, offering computationally efficient tools for predicting molecular behaviour7,8. Their reliability stems from the mathematical rigour of graph-based abstraction and elimination of experimental constraints, making TIs indispensable in modern theoretical chemistry. In chemical graphs, hydrogen atoms are typically omitted to streamline structural analysis. The reliability of QSAR/QSPR predictions is largely influenced by the choice of molecular datasets, algorithms and descriptors used9,10,11.

As purely computational tools, TIs dropping the need for experimental procedures while offering powerful insights into molecular behaviour. Recent innovations include descriptors that account for atomic types and sub structural patterns, which have improved modelling accuracy12,13. Moreover distance-based indices and chirality-aware descriptors have enriched the structural detail offered in drugs discovery and cheminformatics. Exponential structure descriptors have demonstrated strong predictive power for thermodynamic properties of benzenoid hydrocarbons14.

Octane isomers and their structural influence

Octane isomers indicate eighteen distinct structural variations of the hydrocarbon \(C_8H_{18}\), all sharing the same molecular formula but differing in carbon connectivity and branching. These isomers display varied physico-chemical behaviour, with properties such as melting point, refractive index, density and acentric factor affected by their branching geometry and position. One notable example is 2,2,4-trimethylpentane (iso-octane), values for its high resistance to engine knocking and use as a reference fuel in octane rating scales15,16.

Recent advancements in graph-theoretic descriptors have improved the predictive modelling of these isomers. Topological indices based on neighborhood degrees and line graph transformations have shown strong correlations with molecular characteristics, supporting (QSAR) models in computational chemistry17,18,19. Such models help predict molecular behaviour, enhancing compound selection for fuels, solvents and synthetic applications. Furthermore, octane isomers serve as benchmark structures for validating novel indices and regression schemes, making them indispensable in cheminformatics and theoretical graph analysis.

Statistical analysis of QSPR models for topological indices

In regression analysis20, the following statistical terms are employed to evaluate model performance:

-

Residual standard error (Sy.x): represents the standard deviation of the residuals, indicating how far the data points deviate from the predicted regression line. Lower value signify a better model fit.

-

F-statistic (F): measures the overall significance of the regression model. A higher F value suggests that the model explains a substantial portion of the variability in the data.

-

P-value: indicates the probability that the observed correlation occurred by chance. P-value less than 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

-

Indicator: qualitative description based on the P- value, specifying whether the relationship is “Significant” or “Not significant”.

Methodology

Let \(G = (V, E)\) be a simple undirected graph, where V(G) denotes the vertex set and E(G) the edge set, such that \(|V(G)| = n\) and \(|E(G)| = m\). For foundational definitions and graph-theoretic terminology, readers may refer to standard texts such as21,22. If \((r,s) \in E(G)\) represents an edge connecting vertices r and s, then \(d_r\) denotes the degree of vertex r, i.e., the number of edges incident to r. The neighborhood degree \(S_r\) is defined as the sum of degrees of all vertices adjacent to r, capturing the local connectivity around vertex r.

The concept of topological indices in molecular graph theory can be traced back to the work of Harold Wiener in 1947. He introduced the Wiener index23, a distance-based descriptor that relates molecular structure to boiling point predictions.

where \(d(s_i, s_j)\) denotes the shortest path between vertices \(s_i\) and \(s_j\).

Following this, Gutman and Trinajstić proposed the widely cited Zagreb indices in 1972, which capture the branching patterns in molecular structures.

Second Zagreb index is formulated as,

Sombor index24 is defined as,

Redefined third Zagreb index25 is defined as,

Second hyper Zagreb index26 is defined as,

Neighborhood-based second Zagreb index27 is defined as,

Weighted degree of a vertex28 is defined as,

The notation \({e} = rs\) indicates that edge e is incident with vertex r and vertex s.

The second Davan index

Classical topological indices in chemical graph theory serve as foundational tools for understanding molecular structure and properties. Among them, the Wiener index characterizes a molecule by aggregating shortest path distances between pairs of atoms, while Zagreb indices focus on vertex degrees to reflect branching complexity. Motivated by their successful applications, we propose a novel topological descriptor termed the second Davan index, which is constructed using the weighted degree of vertices in a molecular graph.

This new index provides a refined perspective by incorporating both local and edge-based connectivity information through vertex-edge interactions. To assess its chemical relevance, we analyse the statistical correlation between the second Davan index and physico-chemical attributes of various compounds, such as entropy, acentric factor, density and molar volume. The promising regression results suggest that the second Davan index holds significant predictive capability within the QSPR framework.

The second Davan index of a graph H, \(D_2(H)\) is defined as the sum of the product of the weighted degree of a pair of adjacent vertices of H.

Lemma 5.1

Let H be a simple graph. Then, \(d_H^w(r) = d(r)(d(r) - 2) + S(r)\).

Proof

Consider a connected graph H with vertex r, edge \(e=rs\).

\(\square\)

Theorem 5.1

Let H be a simple graph. Then,

Proof

Let \(d_H^w(r)\) represent the weighted degree of a vertex r in a simple graph H. Lemma 5.1 in Eq. (1) we have

\(\square\)

Chemical applicability of second Davan index

In the quantitative structure-property relationship (QSPR) and quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) studies, the second Davan index \(D_2\) has emerged as a significant topological descriptor due to its strong correlation with various physico-chemical properties. To explore this relevance, a linear regression model was formulated to examine the relationship between \(D_2\) and several characteristic properties such as acentric factor (AcentFac), entropy (S), molar volume (MV) and density of octane isomers.

The physico-chemical data of octane isomers were obtained from the official repository of the NIST Standard Reference Database Number 69 (https://webbook.nist.gov/chemistry/). The considered topological indices alongside the physical properties for octane isomers are tabulated in Table 1.

The linear equation for each physical property acentric factor (AcentFac), entropy (S), density and molar volume (MV) with SDI is obtained in Table 1.

The regression equations derived for the \(D_2\) are as follows:

The regression equations derived for the \(HM_2\) are as follows:

The regression equations derived for the \(ReZG_3\) are as follows:

The regression equations derived for the SO are as follows:

The linear equation, derived from Table 1 is used to generate a Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4 that displays the correlation coefficient.

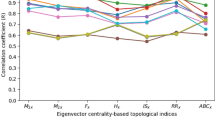

Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4 illustrate the regression modelling and corresponding correlation between four representative physico-chemical properties and the topological indices \(D_2\), \(HM_2\), \(ReZG_3\) and SO. From the data shown in Table 2, it is evident that the second Davan index \(D_2\) exhibits the highest correlation across all selected properties. Notably, the correlation coefficient with acentric factor reaches an exceptional value of \(|r| = 0.9778\) and entropy follows closely at \(|r| = 0.9594\), both indicating strong predictive power.

Furthermore, \(D_2\) maintains consistently high correlations with density (\(|r| = 0.7495\)) and molar volume (\(|r| = 0.7498\)), outperforming other indices such as \(HM_2\), \(ReZG_3\) and SO. While SO also demonstrates considerable correlation with entropy (\(|r|=0.9465\)) and acentric factor (\(|r|= 0.9594\)), its correlation with density and molar volume is notably weaker. In comparison, \(HM_2\) reveals substantially lower correlation coefficients, indicating limited predictive reliability.

These findings reinforce the significance of the \(D_2\) index as a robust topological descriptor in QSPR/ QSAR modelling frameworks, providing strong associative power across multiple molecular attributes and offering enhanced statistical relevance relative to traditional indices.

Table 3 presents the regression statistics for the second Davan index \(D_2\). It reveals exceptionally strong correlations across all selected properties, with particularly high F-values for entropy (\(F = 185.4\)) and acentric factor (\(F = 348.6\)), alongside extremely low residual standard errors (Sy.x). The P-values for all regressions are less than 0.05, confirming statistical significance across the board. These results strongly support the predictive efficacy of \(D_2\) in modelling molecular characteristics.

Table 4 outlines the performance of the \(HM_2\) index. Although entropy demonstrates mild significance (\(P = 0.0311\)), the remaining properties such as acentric factor, density and molar volume yield higher residual errors and P-values above the 0.05 threshold. This indicates that \(HM_2\) shows limited predictive strength and cannot reliably model multiple physical properties within this dataset.

Table 5 contains regression metrics for the \(ReZG_3\) index, which exhibits consistent significance for all parameters. Notably, acentric factor and molar volume both show high F-values (30.44 and 19.75 respectively) and low P-values (\(<0.05\)), affirming the index suitability for QSPR modelling. While residual errors are slightly higher compared to \(D_2\), the overall statistical profile positions \(ReZG_3\) as a reasonably strong topological descriptor.

Table 6 summarizes the regression statistics for the SO index. All physical properties show statistical significance, with entropy and acentric factor delivering strong F-values (137.7 and 185.2 respectively). Though SO exhibits slightly larger residual errors than \(D_2\), its consistent significance and moderate error margins validate its applicability as a dependable topological index within QSPR frameworks.

Sensitivity measure of topological indices for octane isomers

Topological indices are numerical constructs that encode the structural variations of chemical compounds. For an index to be effective, it must distinguish between varying molecular frameworks - particularly among isomers. A frequent limitation in many indices is their degeneracy, where distinct isomers are assigned identical index values, thereby impeding structural differentiation.

To assess an index ability to distinguish among isomers, Konstantinova29 introduced a measure known as sensitivity, mathematically given by:

where:

-

N is the total number of isomers analysed,

-

\(N_I\) is the number of isomers not distinguishable by the index I.

Greater sensitivity implies a stronger capability to discriminate among molecular structures.

Among the various classes of indices, particularly in the case of octane isomers, recently proposed descriptors exhibit higher sensitivity compared to many traditional degree-based indices (see Table 7), affirming their value in capturing intricate structural details.

Table 7 presents the sensitivity (\(\text {SI}\)) values of various topological indices for octane isomers, highlighting their structural discrimination ability. The newly proposed index \(D_2\) achieves a maximum sensitivity of 1.000, meaning it successfully distinguishes all isomers considered in the study. This value, shown in bold in the Table 7, clearly establishes the superiority of \(D_2\) over traditional descriptors such as \(M_2\), \(HM_2\), SO and \(ReZG_3\), which exhibit sensitivity values of 0.389, 0.888, 0.777 and 0.666 respectively. These results underscore the enhanced isomer resolution capability of \(D_2\), making it a highly effective molecular descriptor for chemical graph-based analysis.

The bar chart (Fig. 5) illustrates the comparative sensitivity of five topological indices, with \(D_2\) showing the highest responsiveness and \(M_2\) the lowest. This visualization aids in selecting chemically relevant descriptors for QSPR/QSAR modeling.

Impact of second Davan index on cheminformatics applications: the variation in SDI values across nanostructure types reflects underlying changes in molecular connectivity and symmetry. Higher SDI values, as observed in toroidal forms, suggest increased local and global connectivity, which may correlate with enhanced electronic conductivity, mechanical stability and thermal resilience. For instance, the toroidal \(TUC_4C_8(S)[x,y]\) structure, with its maximal SDI of 1728xy, implies a highly interconnected framework, potentially favorable for charge transport in nanoelectronic applications.

Bounds for second Davan index

Theorem 8.1

For a connected graph H with \(n\ge 3\) vertices and m edges. Then,

\(D_2 (H)\le 4m(n-1)^2 (n-2)^2\),

and equality holds if and only if H is isomorphic to \(K_n\).

Proof

Consider a connected graph H with n vertex and m edge, where \(n \ge 3\). Using Lemma 5.1 in Eq. (1), we have

\(\square\)

Theorem 8.2

For a connected graph H with \(n\ge 5\) vertices and m edges. Then,

\(16n-50\) \(\le\) \(D_2 (H)\le 2n(n-1)^3 (n-2)^2\),

where, equality for lower bound holds for path and equality for upper bound holds for complete graph.

Second Davan index of standard class of graphs

Proposition 9.1

For path \(P_m\), where \(m \ge 5\), \(D_2(P_m) = 16m-50\).

Proof

The path \(P_m\) has m vertices and \((m-1)\) edges. For \(m \ge 5\), we have following partition of edges based on the weighted degree of a vertex:

Using the values from Table 8 in Eq. (1), we obtain

\(\square\)

Proposition 9.2

For cycle \(C_m\), where \(m \ge 3\), \(D_2(C_m)\) = 16m.

Proof

The cycle \(C_m\) has m edges and m vertices. For \(m \ge 3\), the weighted degree of each vertex is four.

\(D_2(C_m) = m (4 \times 4) = 16m.\)

\(\square\)

Proposition 9.3

For complete graph \(K_m\), where \(m \ge 3\), \(D_2(K_m) = 2m(m-1)^3 (m-2)^2\).

Proof

The complete graph \(K_m\) consists of \((m(m-1))/2\) edges and m vertices. Each vertex in \(m \ge 3\) has a weighted degree of \(2(m-2)(m-1)\).

\(\begin{aligned} D_2(K_m)&= ^mC_2[(2(m-2)(m-1))^2 ]\\&= 2m(m-1)^3 (m-2)^2. \end{aligned}\)

\(\square\)

Proposition 9.4

For complete bipartite graph \(K_{m,n}\), where \(m,n \ge 2\),

\(D_2 (K_{m,n} )=(mn)^2(m+n-2)^2\).

Proof

In complete bipartite graph \(K_{m,n}\). For \(m,n\ge 2\), the weighted degree of vertices of \(V_1\) is \(m(m+n-2)\) and the weighted degree of vertices of \(V_2\) is \(n(m+n-2)\).

\(\begin{aligned} D_2 (K_{m,n})&=mn(m(m+n-2))(n(m+n-2))\\&=(mn)^2(m+n-2)^2. \end{aligned}\)

\(\square\)

Corollary 9.1

Let \(K_{n,n}\) be a complete bipartite graph. Then, \(D_2 (K_{n,n} )=4n^4(n-1)^2\).

Corollary 9.2

Let \(K_{1,n}\) be a star graph. Then, \(D_2 (K_{1,n} )=n^2(n-1)^2\).

Definition 9.1

30 Crown graph \(S^0_m\) for an integer \(m\ge 3\) is the graph with vertex set \(\left\{ u_1, u_2 \dots u_m, v_1, v_2 \dots v_m\right\}\) and edge set \(\left\{ u_iv_j;1\le i, j\le m,i\ne j\right\}\).

Proposition 9.5

For crown graph \(S_m^o\), where \(m\ge 3\), \(D_2 (S_m^o )=4m(m-1)^3 (m-2)^2.\)

Proof

In crown graph \(S_m^o\), For \(m \ge 3\), weighted degree of each vertex is \(2(m^2-3m+2)\).

\(\begin{aligned} D_2 (S_m^o )&=m(m-1)(2(m^2-3m+2))^2\\&=4m(m-1)^3 (m-2)^2. \end{aligned}\)

\(\square\)

Proposition 9.6

For ladder graph \(L_m\), where m \(\ge\) 5, \(D_2 (L_m)=768m-2368.\)

Proof

By definition of \(L_m\)31, we have following partition of edges based on weighted degree of a vertex:

Using the values from Table 9 in Eq. (1), we obtain

\(\square\)

Proposition 9.7

For wheel graph \(W_m\) , where \(m \ge 4\), \(D_2 (W_m )=m^4+7m^3+56m-64\).

Proof

In wheel graph \(W_m\), the degree of centre vertex is m and degree of each vertex which are located on cycle is three. Hence, the weighted degree of centre vertex is \(m(m-1)\) and the weighted degree of rest of vertex of \(W_m\) is \(m+8\).

\(\square\)

Proposition 9.8

For gear graph \(G_m\), where \(m \ge 3\), \(D_2 (G_m )=m(m+7)(m^2+m+12)\).

Proof

In gear graph \(G_m\) , the outer layer vertex is of degree alternatives 3 and 2, while the central vertex of degree is m. The center vertex’s weighted degree is \(m(m+1)\), each corner vertex next to it has a weighted degree of \((m+7)\) and the other vertices have a weighted degree of 6.

\(\square\)

Proposition 9.9

For friendship graph \(F_m\), where \(m \ge 2\), \(D_2 (F_m )=16m^4+20m^3+8m^2+4m.\)

Proof

In friendship graph \(F_m\) , 2m vertices are of degree two and center vertex is of degree 2m. The weighted degree of the center vertex is \((2m)^2\) and weighted degree of the remaining vertices is \(2m+2\).

\(\square\)

Topological modelling of carbon-based nanostructures

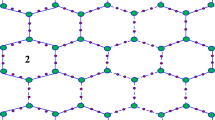

Nanostructures are materials with nano scale dimensions, typically ranging from 1 to 100 nano meters, and are typically used for their unique electronic, biological, mechanical and chemical properties. Chemical graph theory offers a robust framework to model these structures denoted by atoms as vertices and bonds as edges in a graph32. This abstraction facilitates the computation of topological indices (TIs), which are numerical descriptors of molecular structure. 2D-lattice nanostructures refer a planar, grid-like pattern of atoms typically organized in repeating square or hexagonal units. A notable example is the nano tube, a cylindrical molecular framework comprised of carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal mesh. Depending on the number of concentric layers, these are classified as single-walled or multi-walled variants. Similarly, nano torus structures exhibit a toroidal geometry formed by folding a two-dimensional lattice into a closed circular surface, resembling a molecular-scale doughnut.

Among various nanostructure models, the \(TUC_4C_8(S)[x,y]\) (Fig. 6) configuration features a symmetrical network of square (\(C_4\)) and octagonal (\(C_8\)) units arranged in a planar grid. This structure supports predictable weighted degree distributions and facilitates analytical derivations of descriptors like the second Davan index. Transforming this lattice into toroidal forms introduces curvature and periodic boundaries, affecting the distribution of weighted degree-based properties-factors critical in molecular stability and electronic behaviour prediction33.

The rotated counterpart, \(TUC_4C_8(R)[x,y]\) (Fig. 7) modifies the connectivity of \(C_4\) and \(C_8\) units to produce distinct automorphism groups and topological behaviours. This layout often results in increased symmetry and uniformity, making it suitable for computing eccentric connectivity and spectral-based descriptors34. Additionally, zigzag polyhex nanostructures-denoted by \(PTUZC_6[x,y]\), \(TUZC_6[x,y]\) and \(TTUZC_6[x,y]\)-are derived from graphene-like hexagonal lattices. SDI-based analysis of these configurations effectively reveals structural curvature-induced changes in local connectivity, supporting their application in electronic transport, drug delivery and nano medicine35.

In this section, we present explicit formulas for computing the second Davan index for three structurally distinct nanostructures: \(TUC_4 C_8(R)[x,y]\), \(TUC_4 C_8(S)[x,y]\) and the zigzag polyhex \(PTUZC_6[x,y], TUZC_6[x,y], TTUZC_6[x,y]\) (Fig. 8)36,37,38.

Theorem 10.1

Let A be 2D-lattice of \(TUC_4 C_8 (R)[x,y]\). Then,

Proof

(i) The 2D-lattice \(TUC_4 C_8 (R)[x,y]\) has 4xy vertices and \(6xy-x-y\) edges. Based on the weighted degree of vertex, the edge partition of A is given in Table 10.

(ii) The subdivision graph \(S(A)\) has order \(10xy - x - y\) and size \(2(6xy - x - y)\). The edges is determined by the weighted degree of its vertices as shown in Table 11.

(iii)The line graph of subdivision graph \(L(S(A))\) has order \(2(6xy-x-y)\) and size \((18xy-5x-5y)\). The edges is determined by the weighted degree of its vertices as shown in Table 12.

\(\square\)

Theorem 10.2

Let B be \(TUC_4 C_8 (R)[x,y]\) nano tubes. Then,

Proof

(i) The \(TUC_4 C_8 (R)[x,y]\) nano tube has 4xy vertices and \(6xy-x\) edges. Based on the weighted degree of vertex, the edge partition of B is given in Table 13.

(ii) The subdivision graph (S(B)) has the order and size are \(10xy-x\) and \(2(6xy-x)\), respectively. Based on the weighted degree of vertex, the edge partition of S(B) is given in Table 14.

(iii) The line graph of subdivision graph (L(S(B)) of order and size are \(2(6xy-x)\) and \((18xy-5x),\) respectively. Based on the weighted degree of vertex, the edge partition of L(S(B)) is given in Table 15.

\(\square\)

Theorem 10.3

Let C be \(TUC_4 C_8 (R)[x,y]\) nano torus. Then,

Proof

(i) The \(TUC_4 C_8 (R)[x,y]\) nano torus has 4xy vertices and 6xy edges. Based on the weighted degree of vertex is as shown in Table 16.

(ii) The subdivision graph (S(C)) has the order and size are 10xy and 12xy, respectively. Based on the weighted degree of vertex, the edge partition of S(C) is as shown in Table 17.

(iii) The line graph of subdivision graph (L(S(C))) of order and size are 12xy and 18xy, respectively. Based on the weighted degree of vertex, the edge partition of L(S(C)) is as shown in Table 18.

\(\square\)

Theorem 10.4

Let \(F_1\) be zigzag polyhex 2D-structure lattice \(PTUZC_6[x, y]\). Then,

\(D_2 (F_1)=864xy-528x-544y+278.\)

Proof

The order and size of \(F_1\) are \(2y(2x+1)\) and \(6xy-x+y,\) respectively. Based on the edge classification shown in Table 19, the second Davan index \(D_2(F_1)\) is obtained.

\(\square\)

Theorem 10.5

Let \(F_2\) be zigzag polyhex nano tube \(TUZC_6[x, y]\). Then,

\(\begin{aligned} D_2 (F_2)=864xy-528x. \end{aligned}\)

Proof

The order and size of \(F_2\) are 4xy and \(6xy-x,\) respectively. Based on the edge classification shown in Table 20, the second Davan index \(D_2(F_2)\) is obtained.

\(\square\)

Theorem 10.6

Let \(F_3\) be zigzag polyhex nano torus \(TTUZC_6[x, y]\). Then,

\(\begin{aligned} D_2 (F_3)=864xy. \end{aligned}\)

Proof

The order and size of \(F_3\) are 4xy and 6xy, respectively. Based on the edge classification shown in Table 21. Hence we obtain desired result.

\(\square\)

Theorem 10.7

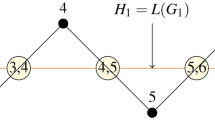

Let \(H_1\) be 2D-lattice of \(TUC_4C_8(S)[x, y]\). Then,

\(\begin{aligned} D_2 (H_1)=1728xy-976(x+y)+14748. \end{aligned}\)

Proof

The order and size of \(H_1\) are 8xy and \(12xy-2(x+y),\) respectively. Based on the edge classification shown in Table 22. Thus we obtain final result. \(\square\)

Theorem 10.8

Let \(H_2\) be nano tube of \(TUC_4C_8(S)[x, y]\). Then,

\(\begin{aligned} D_2 (H_2)=1728xy-976x. \end{aligned}\)

Proof

The order and size of \(H_2\) are 8xy and \(12xy-2x,\) respectively. Based on the edge classification shown in Table 23. The second Davan index \(D_2(H_2)\) is obtained. \(\square\)

Theorem 10.9

Let \(H_3\) be nano torus of \(TUC_4C_8(S)[x, y]\). Then,

\(\begin{aligned} D_2 (H_3)=1728xy. \end{aligned}\)

Proof

The order and size of \(H_3\) are 8xy and 12xy, respectively. Based on the edge classification shown in Table 24. Hence the desired result is obtained.

\(\square\)

Conclusion

In this study, we introduced the second Davan index (SDI), a novel topological descriptor derived from the weighted degree of vertices of molecular graphs. Through rigorous quantitative structure-property relationship (QSPR) analysis involving octane isomers, the SDI demonstrated superior predictive performance, exhibiting the highest correlation coefficients with key physico-chemical properties such as entropy (\(|r| = 0.9594\)), acentric factor (\(|r| = 0.9778\)), molar volume (\(|r| = 0.7498\)) and density (\(|r| = 0.7495\)), when compared against classical indices such as Sombor index, second hyper Zagreb index and redefined third Zagreb index. Specifically, the SDI achieved a perfect sensitivity value of 1.000 in isomer discrimination tests, indicating its ability to uniquely identify all octane isomers and outperforming the sensitivity levels of established descriptors such as \(M_2\) (0.389), \(HM_2\) (0.888), SO (0.777) and \(ReZG_3\) (0.666). Closed form expressions for SDI were derived for several standard graph classes including paths, cycles, complete, bipartite, crown, ladder, wheel, gear and friendship, thereby validating its structural applicability. Moreover, upper and lower bounds for the SDI were established, with extremal cases identified for path and complete graphs. We further extended the applicability of SDI to nanostructures by computing explicit formulas for various molecular configurations such as \(TUC_4C_8(R)[x,y]\), \(TUC_4C_8(S)[x,y]\), \(PTUZC_6[x,y]\), \(TUZC_6[x,y]\) and \(TTUZC_6[x,y]\), including their subdivision and line graph transformations. These results confirm the robustness of SDI across diverse structural domains, establishing it as a reliable descriptor in QSPR modelling and nano scale molecular analysis.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Gutman, I. & Trinajstić, N. Graph theory and molecular orbitals. Total \(\pi\)-electron energy of alternant hydrocarbons. Chem. Phys. Lett. 17(4), 535-538 (1972) .

Trinajstic, N. Chemical Graph Theory (CRC Press, 1992).

Furtula, B. & Gutman, I. A forgotten topological index. J. Math. Chem. 53(4), 1184–1190 (2015).

Shanmukha, M. C., Basavarajappa, N. S., Shilpa, K. C., & Usha, A. Degree-based topological indices on anticancer drugs with QSPR analysis. Heliyon 6(6) (2020).

Hayat, S., Imran, M. & Liu, J. B. Correlation between the Estrada index and \(\pi\)-electronic energies for benzenoid hydrocarbons with applications to boron nanotubes. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 119(23), e26016 (2019).

Kirmani, S. A. K., Ali, P. & Azam, F. Topological indices and QSPR/QSAR analysis of some antiviral drugs being investigated for the treatment of COVID-19 patients. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 121(9), e26594 (2021).

Todeschini, R. & Consonni, V. Handbook of Molecular Descriptors (Wiley, 2008).

Roy, K. Topological descriptors in drug design and modeling studies. Mol. Divers. 8(4), 321–323 (2004).

Shanmukha, M. C., Usha, A., Siddiqui, M. K., Shilpa, K. C. & Asare-Tuah, A. Novel degree based topological descriptors of carbon nanotubes. J. Chem. 2021(1), 3734185 (2021).

Zaman, S., Raza, A. & Ullah, A. Some new version of resistance distance-based topological indices of complete bipartite networks. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 139(4), 357 (2024).

Das, K. C., Huh, D. Y., Bera, J. & Mondal, S. Study on geometric–arithmetic, arithmetic–geometric and Randi-indices of graphs. Discrete Appl. Math. 360, 229–245 (2025).

Balaban, A. T. & Devillers, J. (Eds.). Topological Indices and Related Descriptors in QSAR and QSPAR. (CRC Press, 2014).

Dearden, J. C. Advances in QSAR Modeling. (2017)

Sarkar, P., Pal, A. & Mondal, S. On some exponential structure descriptors and their applications to benzenoid hydrocarbons. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 125(11), e70061 (2025).

Perdih, A. Physicochemical Properties of Octane Isomers in View of the Structural Numbers. Acta Chim. Slov. 68(1) (2021).

Rasheed, M. W., Mahboob, A. & Hanif, I. Investigating the properties of octane isomers by novel neighborhood product degree-based topological indices. Front. Phys. 12, 1369939 (2024).

Alraqad, T. et al. Analysis of octane isomer properties via topological descriptors of line graphs. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 27159 (2024).

Das, K. C. & Mondal, S. On exponential geometric-arithmetic index of graphs. J. Math. Chem. 62(10), 2740–2760 (2024).

Basavanagoud, B., Gali, C. S. & Bhuvana, B. On first closed neighborhood Zagreb index of graph. Commun. Combin. Cryptogr. Comput. Sci. 2024(2), 234–247 (2025).

Wei, J., Hanif, M. F., Mahmood, H., Siddiqui, M. K. & Hussain, M. QSPR analysis of diverse drugs using linear regression for predicting physical properties. Polycycl. Arom. Compds. 44(7), 4850–4870 (2024).

Bondy, J. A. & Murty, U. S. R. Graph Theory with Applications Vol. 290 (Macmil lan, 1976).

West, D. B. Introduction to Graph Theory. Vol. 2. 1-512. (Prentice Hall, 2001).

Wiener, H. Structural determination of paraffin boiling points. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 69(1), 17–20 (1947).

Gutman, I. Geometric approach to degree-based topological indices: Sombor indices. MATCH Commun. Math. Comput. Chem. 86(1), 11–16 (2021).

Usha, A., Ranjini, P. S., & Lokesha, V. Zagreb co-indices, augmented Zagreb index, redefined Zagreb indices and their polynomials for phenylene and hexagonal squeeze. In Proceedings of International Congress in Honour of Dr. Ravi. P. Agarwal, Uludag University, Bursa, Turkey (2014).

Gao, W., Farahani, M. R., Siddiqui, M. K. & Jamil, M. K. On the first and second Zagreb and first and second hyper-Zagreb indices of carbon nanocones CNC k [n]. J. Comput. Theor. Nanosci. 13(10), 7475–7482 (2016).

Shirdel, G. H., Rezapour, H. & Sayadi, A. M. The hyper-Zagreb index of graph operations. Iran. J. Math. Chem. 4, 213–220 (2013).

Prakasha, D. G. & Gali, M. On weighted forgotten index of total transformation graphs. Ann. Math. Comput. Sci. 20, 41–62 (2024).

Konstantinova, E. V. The discrimination ability of some topological and information distance indices for graphs of unbranched hexagonal systems. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 36(1), 54–57 (1996).

Adiga, C., Bayad, A., Gutman, I. & Srinivas, S. A. The minimum covering energy of a graph. Kragujevac J. Sci. 34, 39–56 (2012).

Gallian, J. A. A dynamic survey of graph labeling. Electron. J. Combin. 6(25), 4–623 (2022).

Estrada, E. Topological structural classes of complex networks. Phys. Rev. E-Stat. Nonlinear Soft Matter Phys. 75(1), 016103 (2007).

Hansen, P. J., & Jurs, P. C.: Chemical applications of graph theory. Part I. Fundamentals and topological indices. J. Chem. Educ. 65(7), 574 (1988).

Diudea, M. V., Gutman, I. & Jantschi, L. Molecular Topology 332 (Nova Science Publishers, 2001).

Basak, S. C. Use of graph invariants in quantitative structure-activity relationship studies. Croat. Chem. Acta 89(4), 419–429 (2016).

Nadeem, M. F., Zafar, S. & Zahid, Z. On certain topological indices of the line graph of subdivision graphs. Appl. Math. Comput. 271, 790–794 (2015).

Su, G. & Xu, L. Topological indices of the line graph of subdivision graphs and their Schur-bounds. Appl. Math. Comput. 253, 395–401 (2015).

Basavanagoud, B. & Gali, C. S. A note on certain topological indices of the derived graphs of subdivision graphs. TWMS J. Appl. Eng. Math. 10(1), 208–219 (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ms. Swapna B S - Conceptualization, Methodology, Article writing, Resources, Validation. Dr. Chetana G & Dr. Shanmukha M C - Review of the manuscript, Formal analysis, Suggestions given for correction of manuscript, Supervision, Validation. Dr. Manjunath G & Dr. Usha A - Review of the manuscript, Formal analysis, Suggestions given for correction of manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Swapna, B.S., Chetana, G., Shanmukha, M.C. et al. Chemical significance and degeneracy of weighted degree-based topological descriptor second Davan index for octane isomers and computation of certain nanostructures. Sci Rep 15, 36568 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20539-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20539-z