Abstract

The rapid assimilation of Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems into Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) systems has exposed them to advanced cyberattacks with potentially devastating impacts on critical industrial processes and functionalities. Traditional methods of intrusion detection, including signature-based detection, statistical anomaly-based detection, and classical machine learning techniques, can become overwhelmed by the sheer scale of high-dimensional feature spaces and the nonlinear patterns of attacks. To address these limitations, this paper presents a Deep Factorization Machine (DeepFM)-based intrusion detection scheme, specifically designed for SCADA systems. As a novelty of DeepFM, the framework integrates the advantage of factorization machines in modeling low-order interactions of features with deep neural networks to capture high-order representations, thereby improving performance in detection tasks in complex IIoT environments. The framework is tested on four benchmark datasets, namely WUSTL-IIoT-2018, WUSTL-IIoT-2021, HAI (HIL-based Augmented ICS) Security, and the Sherlock dataset. Moreover, the experimental results demonstrate that the recommended approach outperforms others in various conditions. On our WUSTL-IIoT-2018 dataset, DeepFM achieves nearly perfect accuracy of 99.98% with an F1-score of 0.9997, significantly outperforming conventional baselines. In WUSTL-IIoT-2021, the accuracy score is high, 98.72 percent, with strong recall (0.9765) and the F1-score (0.9945). On HAI data, it obtains the accuracy of 95.6%, precision of 0.967, and recall of 0.973. On the Sherlock dataset, the model maintains 95.4% accuracy and an F1-score of 0.955. These findings not only prove the flexibility, resilience, and scalability of DeepFM in SCADA intrusion detection but also confirm that the method is suitable for application in a wide range of systems. The proposed framework is more effective than traditional approaches and should be considered a practical solution for integrating security into IIoT infrastructures. Future work will focus on real-time deployment, optimizing edge devices, and defensive measures against attacks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The changing threat environment of Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems is urgent, with a variety of factors influencing the threat landscape, including the proliferation of Internet of Things (IoT) devices, increased connectivity, and the emergence of advanced cyber threats1,2. The power grid, water treatment plant, and transportation system are among the other critical infrastructures that depend on SCADA systems, where vital processes are managed within the industry3. SCADA systems continue to play a crucial role in ensuring operational efficiency, and SCADA network security is also a significant concern4,5. Despite the consistent increase in cyberattacks on industrial control systems, including SCADA infrastructure, a 74 percent surge in the number of incidents involving critical infrastructure has occurred in the United States between 2019 and 20234,6,7,8. Additionally, the increased interconnection of SCADA systems with external networks and the implementation of cloud and edge computing technologies have expanded the attack surface, making it more susceptible to cyberattacks8.

Currently, most conventional security mechanisms applied to protect industrial systems do not adequately address the needs of emerging threats9. Attacker sophistication is on the rise, and various types of attack methods have never been encountered or addressed by traditional defense mechanisms10,11. This has led to the need to develop advanced, multifaceted, and robust intrusion detection mechanisms (IDSs) that can be implemented in real-time to detect cyber threats12. Furthermore, using machine learning methods, intensive learning models represent a promising approach for improving intrusion detection in SCADA systems13. In evaluating IDS capability, we discuss the use of deep factorization machines (DeepFM) to enhance the detection ability of IDS. DeepFM is a neural architecture that integrates the best aspects of factorization machines and deep learning. Factorization machines are well-suited for capturing interactions between variables in large datasets and are particularly suitable for applications in IDS, particularly in the feature engineering process14,15. DeepFM, when integrated with deep learning networks, can learn complex, nonlinear relationships in data and serve as a powerful detection tool for discovering intricate patterns of malicious behavior that might otherwise go undetected16.

Furthermore, this research is inspired by the exposure of SCADA systems to hostile cyber environments. Hence, it is infused to provide stronger security capabilities within the SCADA17. Traditional IDS approaches rely on signature-based or anomaly approaches, which are challenging, particularly given the large and complex nature of current data streams18. Moreover, only defined rules are ineffective against the dynamic threats typically employed in traditional techniques. DeepFM, on the contrary, tends to evolve to new patterns of an attack through large-scale data and learn how to identify even a slight connection between the system variables and the attack.

The importance of this study lies in the fact that there are several key problems. The scalability of existing intrusion detection solutions for SCADA systems is first limited18,19. Traditional IDS models struggle to process extensive and high-dimensional data in real-time as industrial systems become increasingly interconnected and the data generated becomes more abundant. Second, the operational environment in which SCADA systems operate is often highly dynamic and includes a vast diversity, making it challenging for conventional approaches used to detect anomalies20. Current IDS frameworks are unable to analyze the interactions between different system components or detect complex attack patterns21. Third, detection of zero-day attacks (previously unknown vulnerabilities now used by attackers) has not been effectively carried out in SCADA systems22. Improving security relies on DeepFM to learn from historical and real-time data, enabling it to detect such attacks23,24.

Additionally, with SCADA systems increasingly reliant on IoT devices, more volume and variety of data are generated, and the challenge grows exponentially to differentiate normal from malicious behavior25,26,27. DeepFM’s capability to process and analyze a massive amount of heterogeneous data from various sources, including IoT sensors, control systems, and external networks, can meet this challenge.

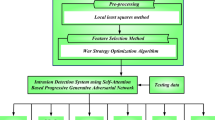

Furthermore, Fig. 1 illustrates the detailed procedure for SCADA intrusion detection using the Deep Factorization Machine (DeepFM) Framework. Data preprocessing is the first phase in which data is cleansed, normalized, and engineered to improve its quality and relevance. DeepFM is a powerful machine learning model that combines deep learning and factorization techniques to efficiently extract complex patterns from preprocessed data.

Our findings contribute to the advancement of intrusion detection in SCADA systems and provide valuable insights into current research directions in cybersecurity.

-

i.

Introducing a novel approach to DeepFM: We are the pioneering entity to apply the Deep Factorization Machine (DeepFM) framework to intrusion detection within SCADA/ICS systems. Our model is capable of learning both high-order and low-order feature interactions, thereby attaining commendable performance within a single, unified framework, facilitated by the integration of factorization machines and deep learning.

-

ii.

Two-level feature interaction Paradigm: The novelty of the proposed structure is that it is the only form that uniquely captures low and high-order interaction features on the same scale with better generalization abilities across heterogeneous IIoT.

-

iii.

Large cross-dataset evaluation: In contrast to the prior work, we tested our model on four prominent datasets, WUSTL-IIoT-2018, WUSTL-IIoT-2021, HAI, and Sherlock, with high and consistent performance unchanged in any architecture or hyperparameters.

-

iv.

Scalability over baselines: The comparative experiments indicate that DeepFM outperforms the other state-of-the-art deep learning models and machine learning inference speed and accuracy, thus suitable to be deployed in real-time SCADA environments.

-

v.

Stability and real-world applicability: Dropout regularization, preprocessing, and stable training processes make the framework less vulnerable to overfitting, and scalable to real-world IIoT use, providing a practical roadmap to proactive industrial cyber defense.

Furthermore, this study is motivated by the need to enhance the security of SCADA systems against emerging cyber threats. We aim to develop a more resilient, scalable, and adaptable intrusion detection framework utilizing DeepFM to identify attack vectors. This research seeks to address critical gaps in current intrusion detection approaches and serves as a step toward protecting the integrity and resilience of industrial control systems worldwide.

Based on the above framework, our study is organized as follows: “Introduction” is the introduction. "Literature review" discusses the relevant past studies. "Data set" explains the processing and presentation of data, while "Methodology" gives an overview of the proposed model. "Experiment and results" presents the results, and "Discussion" evaluates the project’s achievements. "Conclusion" concludes the research.

Motivation

The rapid adoption of SCADA systems into the Industrial IoT world has made them vulnerable to advanced cyberattacks, which can be highly disruptive to critical infrastructure. Conventional detection methods, including signature-based methods, statistical-based models, and even traditional machine learning classifiers, can not keep up with the high-dimensional, heterogeneous, and nonlinear properties of ICS data. Although deep learning frameworks, such as CNNs, LSTMs, and autoencoders, have been promising, each one tends to be able to learn only one of the following: low-order correlations or high-order interactions of features, but not both simultaneously. Such a limitation leaves some room for robust and generalized detection in diverse datasets. To counter this, a recent advance called DeepFM applies to our study due to its ability to integrate both factorization machines and deep neural networks, thereby learning both low- and high-order feature relations. We expect to enhance the scalability, accuracy, and real-time capabilities of an intrusion detection system in SCADA by utilizing this architecture.

Problem statement

The growing complexity and magnitude of cyberattacks present a significant risk to Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems, which are paramount in the monitoring and control of industrial processes. The classical security mechanisms, especially signature-based detection methods, cannot perform adequately against intentional and sophisticated attacks that utilize new attack vectors. Despite the integration of top-notch deep learning algorithms to enhance resilience, ICS defenses have faced challenges in addressing the emergent complexities of adversary strategies. The growing use of attack techniques that evade identification by static models creates gaps in effective detection and slows down the response, which can have disastrous consequences for critical infrastructure. This indicates a pressing need for intelligent and flexible anomaly detection mechanisms that can safeguard SCADA networks against intrusion and malicious behavior.

Although there is considerable research on the application of deep learning to ICS security, current real-world solutions do not demonstrate satisfactory reliability due to their inability to generalize in diverse and dynamic environments. Moreover, the current models have issues with a high false positive rate, a failure to execute with high precision, and a lack of interpretability, which impairs their functionality in operational settings. To mitigate these limitations, this work proposes a new DeepFM for use in security anomaly detection networks of SCADA systems. The proposed approach will enable the combination of feature interaction modeling with the functionality offered by a deep learning framework, thereby enriching detection accuracy, increasing resistance to complex attacks, and strengthening the security status of critical industrial infrastructures.

Literature review

The increased population of networked devices within the industrial environment has necessitated the need to defend SCADA systems against cyber threats1,2. This has led to a rise in the efforts made by researchers to design effective intrusion detection systems to overcome the challenge presented by SCADA systems3,4. Gaber et al.7 presented a model for detecting intrusions in Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) via machine learning and optimization. As their methodology, they combined PSO with the bat algorithm and combined them with random forest. The results of this approach were auspicious, with an accuracy of 95.68% at the WUSTL-IIoT 2021 dataset. Nevertheless, their work failed to undergo a thorough comparison with other methodologies and demonstrated some degree of dependence on specific datasets.

Recent innovations in federated learning have demonstrated encouraging outcomes in securing and enhancing privacy across various healthcare and IoT networks. An interactive SRU network was proposed, which achieved high accuracy (97.9%) despite the challenges, such as gradient decay and tradeoffs in computation8. The other study applied federated boosting to detect dynamic cyber-attacks in consumer IoT systems with 99.7% accuracy, although it was associated with limitations in data and resource balance9. Moreover, a federated reinforcement-based fusion model of IoMT networks was able to effectively resist cyber-attacks (99.4 percent) without relying on inadequate datasets or resource constraints10.

Moreover, Alzahrani et al.11 were working on the development of efficient artificial intelligence strategies to promote cybersecurity within intelligent industrial control systems. They utilized the K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) model, which achieved an accuracy of 96.67%. However, this evaluation was restricted because the criteria were narrow, and the assessment of how this model can be applied outside of the particular dataset was not performed.

Mohy et al.21 employed an ensemble learning technique to detect intrusions in Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) edge computing scenarios. They employed Random Forest in conjunction with Isolation Forest (IF) and Pearson’s correlation coefficient (PCC). Although the study achieved an accuracy of 93.57%, it lacked a comprehensive explanation for selecting features and did not extend its findings to situations beyond edge computing. In addition to expanding the range of methods used, Dina et al.23 proposed a deep learning technique that employs the focal loss function for detecting intrusions in IoT systems. The study achieved high accuracies of 93.08% for CNN and 93.26% for Feedforward Neural Networks (FNN).

However, it did not include a comparison examination of other loss functions and may be biased due to the dataset’s selection method. Castillo et al.24 introduced CPS-GUARD, an intrusion detection system designed for cyber-physical systems (CPS) and Internet of Things (IoT) devices. This system utilizes outlier-aware deep autoencoders. Although the study achieved an accuracy of 96.1%, the debate on its ability to withstand challenges was limited, and the potential biases in evaluation resulting from outlier identification approaches were not thoroughly examined.

In addition, Obonna et al.28 conducted a study aimed at detecting man-in-the-middle (MitM) attacks in oil and gas process control networks by applying machine learning techniques. Their research focused on expanding the scope of intrusion detection to specific cyber-physical contexts29. Their application of the subspace discriminant technique resulted in an accuracy rate of 93.1%. Nevertheless, the study did not thoroughly comment on the models’ interpretability and applicability to different network topologies. A survey conducted by Tauqeer and colleagues30 focused on detecting cyberattacks in the Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) using gradient boosting and support vector machine (SVM) methods. The study achieved accuracies of 96.5% and 95.85%. However, it did not provide much information about feature engineering and could not be applied to applications beyond IoMT.

Table 1 below lists previous references, datasets, techniques, restrictions, and outcomes.

Previous research on SCADA intrusion detection has predominantly depended on relatively limited datasets, underutilized variants of WUSTL-IIoT, or non-industrial latent-based models, such as those employed in healthcare and IoMT, which encounter resource constraints and challenges in generalization. These endeavors often lack comprehensive comparisons, cross-dataset validation, or robustness assessments, thereby restricting their applicability across diverse SCADA environments. Our study aims to address these deficiencies by training a Deep Factorization Machine across four benchmark datasets, thus offering broader validation and demonstrating enhanced adaptability.

Data set

WUSTL-IIOT-2018 dataset

In our study on SCADA cybersecurity, we utilized the data presented in Table 2. The information was generated using the SCADA system. The testbed we created is similar to industrial systems found in the real world. This design allowed us to conduct real cyberattacks.

The Audit Record Generation and Utilization System (ARGUS) tool monitored all network activity, regardless of its regularity. The traffic is kept and recorded in a CSV file.

From the raw data collection, a 627 MB file was created. It comprised 93.93% normal traffic, which refers to traffic that was not attacked, and 6.07% abnormal traffic, which refers to traffic that was attacked. Table 3 shows that the raw data has twenty-five networking traits. Some traits help us group the data, while others enable us to train and test machine learning systems.

Data cleaning

Upon gathering the data, we immediately initiated the process of labeling, classifying, and cleaning the dataset. The data pre-processing pipeline, which prepared the dataset for machine learning, is shown in Fig. 2.

Part of the data cleansing process involves looking for the following common errors:

-

Missing values: The dataset is information organized in rows and columns, presented as a table. Therefore, columns with missing values in the dataset are confirmed.

-

Corrupted values: Invalid entries, corrupted values, etc., are checked for.

-

Outliers: The presence of outliers in the dataset is confirmed, and whether the outlier is a sign of variation or the result of an error during data collection is determined.

-

Data splitting: We also use the train-test split scheme here to test the accuracy of the DeepFM model. To ensure that the model is adequately trained to adjust itself accordingly and has sufficient training and test data, we divided the total dataset into 70 percent (training) and 30 percent (testing) sets, which provides us with adequate training and test data. This technique gave a trade-off between objective performance assessment and rapid model training.

-

Performance testing: We used a fivefold cross-validation approach (k = 5) on the WUSTL-IIOT-2018 dataset to evaluate the reliability of the developed model. As shown in Table 4, cross-validation helps reduce the risk of overfitting by using a train-test split index instead of the dataset’s folds. This process confirmed that the model remained stable, minimized overfitting, and was tested on optimized folds.

Table 5 shows the cleaned binary data frame.

In our research on targeted attacks against SCADA systems, we utilize the cleaned and processed data displayed above to move beyond signature-based protocols and take control of operating procedures31. In the past, researchers have used DL and RL algorithms to reduce the risks caused by ICS. Nonetheless, with the current development of technology, these methods will be reduced in terms of monitoring and improving the cybersecurity of these systems against unauthorized attacks. To eliminate such worries, we shall provide a deep factorization machine framework to identify anomalies in the SCADA network32.

Exploratory data analysis (EDA)

A thorough exploratory data analysis (EDA) is performed on the proposed dataset to examine the dataset and identify correlations between characteristics and goal variables. This allows us to determine the values and correlations between incursion and regular traffic33. This enables us to develop a machine-learning framework for identifying these attacks on SCADA systems, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

The distribution of each feature is evaluated to determine the ranges in which the feature values are typically observed for regular traffic and the values at which they become vulnerable to intrusion attacks.

This indicates that the genuine range of the feature, where traffic is often usual, is between 50,000 and 70,000, which makes up 80% of the distribution for feature types like sports34,35. The narrow ranges between 0 and 40,000 may indicate that it is inside this feature’s incursion range.

Now, each of the features mentioned above in Fig. 4 separates the range of malicious and valid traffic since the histogram shows that the values of the attributes totpackets, DSKbytes, and src bytes tend to be between 0 and 1 rather than inside a specific range.

Even though our dataset is incredibly unbalanced, it is large enough for each class to have enough features to be trained and produce an effective SCADA network traffic detector. Figure 5 above shows the target variable binary histogram.

The correlation chart in Fig. 6 indicates that the target variable is not directly associated with any of the features. Instead, it is primarily negatively associated, while the features have substantial correlations. Our database has a combination of highly positively and negatively related factors. This prevents the model from overfitting.

As previously stated, the normal traffic falls within the range of 60,000, while the malicious traffic falls within the range of 40,000 and 0, as clearly shown in the scatter chart in Fig. 7.

Figure 8 depicts the scatter chart. We have also highlighted that the normal traffic for all of the mentioned features, such as total packets, TotBytes, ScPkts, DstPkts, and ScBytes, exhibits significant variability for each variable35,36. However, the attack type remains constant at 1.

The bar chart depicted in Fig. 9 indicates that src bytes, src-packet, and to bytes exert the most significant influence on the model’s training for classifying normal or malicious data37,38. The other features, such as DSTpkts, contribute less than 0.05 to predicting whether the SCADA traffic is normal or malicious and can still be included in our dataset.

Methodology

Deep factorization machines

Our objective is to acquire knowledge in both low-order and high-order feature interactions. We suggest utilizing a neural network that incorporates factorization and machine learning techniques, known as DeepFM. This architecture is depicted in Fig. 10. Two components that share the same input comprise DeepFM: the FM component and the deep component. To determine the order-1 significance of a feature, a scalar wi and a latent vector are utilized. The influence of its interactions with other characteristics is measured using Vi. To represent order-2 feature interactions, vi is supplied to the FM component, which is then fed into the deep component to model high-order feature interactions. For the combined prediction model, all parameters—including wi, Vi, and the network parameters (W(l), b(l) below)—are trained simultaneously in Eq. (1):

If the prediction is denoted by \({\hat{\text{y}}}\) ∈ (0, 1), the output of the FM component is \(\mathbf{y}\mathbf{F}\mathbf{M}\), and the output of the deep component is \(\mathbf{y}\mathbf{D}\mathbf{N}\mathbf{N}\).

FM component

A factorization machine, also known as the FM component, learns how features are linked to make recommendations. It can also describe pairwise (order-2) and linear feature interactions by finding the inner product of the latent vectors of the related features, as shown in Fig. 11.

It can capture order-2 feature interactions with far more success than previous methods, particularly in low-density datasets. Previously, optimizing the parameter of a feature interaction between features i and j was only feasible if both features were present in the same data record. Conversely, FM computes the parameter by performing the inner product of its latent vectors, Vi and Vj. FM can train a latent vector \(\mathbf{V}\mathbf{i}(\mathbf{V}\mathbf{j})\) anytime the value \(\mathbf{i}(\mathbf{o}\mathbf{r}\mathbf{j})\) Thanks to its adaptable structure, it is present in a data record. As a result, FM is more effective at learning feature interactions when they are absent or occur rarely in the training set.

The result of FM is the sum of numerous Inner Product units and an Addition unit, as shown in Eq. (2):

where (k is provided) w ∈ Rd and Vi ∈ Rk.2. The influence of order-2 feature interactions is represented by the Inner Product units. In contrast, the Addition unit (\(\mathbf{h}\mathbf{w},\mathbf{x}\mathbf{i}\)) indicates the significance of order-1 features.

-

i.

Deep component

The deep part uses a feed-forward neural network to find how high-order traits interact. An input vector is a list of the information the neural network gets. The input for prediction is very different from that of neural networks, which can only handle dense and continuous image or audio data. This means that a new network design is needed. Specifically, the raw feature input vector for prediction is typically divided into four categories: very high-dimensional, very sparse, categorical-continuous, and mixed. An embedding layer should shrink the input vector into a dense, low-dimensional real-value vector before sending it to the first hidden layer. If not, the network may be too big to train. Figure 12 illustrates the difference in the distribution of the deep layer.

FM currently employs the latent feature vectors (V) as network weights to learn and compress the input field vectors to the embedding vectors, despite the possibility of varied input field vector lengths.

Figure 13 shows the distribution of the embedding layer. In this work, we integrate the FM model with another DNN model as part of our learning architecture, rather than starting the networks with FM’s latent feature vectors. This eliminates the need for FM pre-training and collaboratively trains the entire network from end to end.

The output of the embedding layer is shown in Eq. (3).

where m is the number of fields and \(\mathbf{e}\mathbf{i}\) is the embedding of the i-th field. After that, the deep neural network receives a (0), and the forward process is:

Equation (4), σ is an activation function, and l is the layer depth. a (l), W(l), and b (l) represent the l-th layer’s output, model weight, and bias, respectively. Next, a dense real-value feature vector is created and ultimately fed into the prediction-based sigmoid function:

|H| indicates the number of hidden layers. It is important to remember that the feature encoding the deep and FM components share is beneficial in two critical ways: (1) It does not require skilled feature engineering on the input like Wide and Deep do; (2) It learns from raw features, such as how low- and high-order features interact with each other.

Both the deep component and the FM component are simultaneously trained by DeepFM. The following advantages help to raise the system’s performance:

-

No prior training is required.

-

To prevent feature engineering, it (1) teaches a way to share information called "feature embedding” and (2) learns how high- and low-order features function together

-

ii.

Selecting DeepFM

We selected DeepFM because it has two networks, FM and DNN, making it a general-purpose model for our approach. This architecture is particularly well-suited for intrusion detection because:

The FM component gathers interactions between widely spread features like protocols and types of services, which are essential for recognizing weak patterns in the network activities. This model’s DNN component learns high-order and interaction features and can detect high-level and multi-layered cyber threats possible in Industrial IoT and SCADA. Comparing DeepFM to Traditional ML Models: KNN or Random Forest type of machine learning models, do give reasonable performance, but they need feature extraction to be done by the data scientist, and are not very efficient in modelling nonlinear interactions between the features. Since this model can accommodate sparse and dense feature sets, the variety of input information allows it to gain immunity to different forms of attack (e.g., DDoS, Probe, R2L).

-

iii.

Expected benefits for IDS prediction

-

Scalability: DeepFM has been designed to take advantage of efficient architecture and thus can handle high-dimensional data, which is helpful in real-time IDS in SCADA systems where large data sets of network traffic are expected.

-

Feature interaction: The factorization machine in DeepFM can improve the learning of feature cross between large-number category features and continuous numerical features for distinguishing new traffic as malignant or beneficial according to a subtle combination of its attributes (like source IP, destination port).

-

Factorization machines (FM): FM is also used for collaborative filtering, providing an efficient way of modeling the interaction between features. Since IDS systems function based on interactions between some network parameters (e.g., packet size, IP addresses), FM’s efficiencies are highly relevant to the problem.

-

Deep neural networks (DNN): Backpropagation and gradient-descent integrated into DNNs efficiently predict nonlinear dependencies and select higher-order features in complex cyberattack patterns detectable in SCADA systems and other industrial networks.

Justification in the context of IDS

Conventional frameworks (e.g., KNN or Random Forest) depend mostly on the similarity of features or decision boundaries. However, they fail to provide reliable scores with high-dimensional data and complex, multiple feature interactions. DeepFM is theoretically suitable for addressing both sparsity and model complexity, enabling efficient learning from both types of data.

-

Learning low-order interactions (e.g., between individual features like source and destination IPs) to detect simpler attacks.

-

Learning high-order interactions (e.g., more complex patterns across multiple network layers and time windows) to identify sophisticated, multi-step attacks.

-

The DeepFM model, combined with FM for low-order interactions and DNN for high-order interactions, offers a theoretically sound approach that addresses both of these needs, particularly suited to the multidimensional nature of SCADA network traffic.

-

DeepFM’s theoretical background—the ability to work with sparse categorical data and combine it with dense numeric features—is essential in identifying several potential cyber threats in SCADA systems.

-

i.

Unified learning of low and high-order interactions

DeepFM incorporates both the first-order feature effect based on FM and the high-order feature effect based on DNN. This dual capability makes DeepFM especially effective in identifying as many cyber-attack patterns as possible, ranging from simple anomalous activity to more subtle and complex hacking attempts. However, other conventional models, such as Random Forest or KNN, are often restricted to low-order interactions or require pre-processing or feature extraction to detect features of higher orders, thereby gaining the best solution for the IDS field, which frequently confronts high-dimensional data.

-

ii.

Automatic feature engineering

Nonetheless, DeepFM’s major advantage lies in doing feature interaction learning in a non-ad hoc manner, where users do not have to participate in the feature engineering process deeply. Taken with other models where feature selection and tuning play a significant part in determining the model’s performance, such as SVM or KNN, it is clear that the present work still has considerable room for improvement. As DeepFM works end-to-end, the model automatically learns the features required for detecting anomalous traffic patterns without the need to handcraft such features, serving as an advantage to the model when applied in a real-world intrusion detection system.

-

iii.

Handling sparse and dense data efficiently

Most IDS datasets contain a few categorical variables, such as IP addresses and protocol types, and numerical values, such as packet size and time intervals. DeepFM is more useful in handling of such two kinds of data efficiently due to the FM layer for the sparse data and the DNN layer for the dense data. Other models, such as logistic regression or decision trees, may fail with either small density data or a large number of variables, which causes a need for preprocessing that adds to the model’s complexity and computational cost.

Model advantages and complexity over simpler models and comparative novelty

It’s critical to explicitly state the distinctive features of our methodology that set it apart from current AI models and how our study goes beyond just applying well-known algorithms to pre-existing datasets to allay concerns about innovation and research content. A more thorough description of such distinctions may be found below:

-

Optimizing the model for SCADA-specific issues: Our research extends beyond the general usage of AI models, even if DeepFM has been applied in other fields. Unlike ordinary intrusion detection systems, SCADA systems are renowned for their unique attack surfaces and real-time, high-availability requirements. In our work, we customized DeepFM to manage SCADA-specific features like:

-

Real-time detection: We made the DeepFM model feasible for the low-latency needs of SCADA systems by fine-tuning hyperparameters, trimming the model, and carrying out additional computational improvements.

-

Data representation imbalance: SCADA datasets such as WUSTL-IIoT 2018 exhibit notable class imbalances, with some attack types being far less common than typical traffic. We addressed this by implementing specific strategies during training, such as dynamic weight balancing and focus loss, which improved sensitivity to essential yet uncommon assault types.

-

Providing evidence of scalability and deployment viability: Although much earlier research has suggested models that perform well on smaller datasets, scalability and practical implementation issues are frequently disregarded. In this study, we showed that the DeepFM model:

-

i

Particular analogy with conventional methods: The contrast to well-known machine learning models, such as KNN or Random Forest, which have been widely applied in the area, highlights the originality of our approach:

Although KNN and Random Forest techniques have demonstrated respectable accuracy (between 95 and 99%), they are computationally wasteful when used in a live SCADA environment. They are inappropriate for SCADA systems’ dynamic and high-stakes environment because of their dependence on feature selection, inability to manage intricate feature interactions, and inefficiency in real-time processing. By capturing both low- and high-order feature interactions without human feature engineering, our model, DeepFM, surpasses the capabilities of existing conventional models. This leads to increased accuracy (99.99% as opposed to lower findings in previous research) and generalizability across various attack types in SCADA systems.

-

ii.

Attack-specific differentiation: Our study investigates a more detailed categorization of different attack vectors inside the SCADA environment, in contrast to previous research that frequently concentrates on binary or restricted attack detection (e.g., normal vs. attack):

-

Handling complexity and large-scale data: DeepFM performs exceptionally well in situations involving intricate feature interactions and high-dimensional data. Because KNN relies on computing distances between data points for each prediction, its performance deteriorates as dataset sizes increase, even though it works well in smaller datasets. In contrast, DeepFM is made to effectively train both high-order (DNN) and low-order (FM) feature interactions, which is essential for identifying complex and diverse intrusions in SCADA systems.

-

Flexibility in feature engineering: KNN uses the raw feature space for computations rather than automatically learning feature interactions or representations. KNN depends on well-constructed input features, which frequently necessitate intensive human feature engineering due to its lack of automated feature extraction. DeepFM’s hybrid design, which combines Deep Neural Networks (DNN) and Factorization Machines (FM), allows it to capture more intricate, non-linear relationships between features by automatically learning feature representations from raw data without human involvement.

-

Efficiency: In large-scale deployments, DeepFM outperforms KNN in terms of processing efficiency. Because KNN calculates the distances to each training instance, its prediction phase might be computationally costly. DeepFM, on the other hand, can produce predictions in constant time (O(1)) after training, regardless of the dataset size. This is especially significant in real-time SCADA systems where low latency and quick detection are essential.

-

Generalization and preventing overfitting: Conventional models, such as KNN, tend to memorize the training data without appropriately generalizing, which can lead to overfitting, particularly when working with noisy or unbalanced datasets. When paired with regularization strategies like dropout, DeepFM’s DNN component helps SCADA systems avoid overfitting while ensuring generalization across various attack types and network conditions.

-

Scalability: The computation can be highly demanding if the dataset is large or as more features are added. This is especially important in our case, given that our data sample size exceeds 7 million observations. The time complexity of training the model may also become an issue, depending on the time required to train the model, particularly in real-time intrusion detection.

-

Hyperparameter tuning: DeepFM’s complexity also covers the high requirement of tuning hyperparameters. Every component typically has several parameters that must be tuned, and these tunable parameters can potentially exponentially increase the computational cost when they reach the model selection phase.

The coding algorithm for the SCADA system’s DeepFM Framework for Intrusion Detection is as follows:

Algorithm 1: Pseudo-code for loading, preprocessing, model training.

DeepFM proposed model architecture

This approach, known as DeepFM (Deep Factorization Machine), combines factorization machines (FM) with deep neural networks (DNN) to capture second-order feature interactions, thereby enabling the recognition of complex patterns and handling higher-order interactions. This approach significantly benefits tasks such as binary classification in recommendation system scenarios and click-through rate prediction.

Model components

The following are the model components for DeepFM’s proposed model architecture, as shown in Fig. 14:

-

i.

Inputs: This input layer ingests the dataset’s features. Input_dim, the number of features in the dataset, is the value of the shape. Every input is matched to a tabular data feature.

-

ii.

FM Part: This layer depicts the model’s factorization machine component. It features a ReLU activation function and is a dense (ultimately fully connected) layer with 1 unit. The FM component is designed to capture interactions between second-order features linearly.

-

Dense layer

-

Units: One

-

ReLU activation

-

-

iii.

DNN Part: This section of the model reflects the deep neural network component. It is made up of many layers:

-

Rate of dropout: 0.5

-

-

iv.

Dense layer: The following layer uses 256 units and a ReLU activation function. It captures the intricate, non-linear relationships between the input features.

-

Units: 256

-

ReLU activation

-

-

v.

Dropout Layer: To avoid overfitting, add another dropout layer with a 0.5 dropout rate.

-

Rate of dropout: 0.5

-

-

vi.

Dense layer: The last dense layer in the DNN section features an activation function of ReLU and 128 units. It keeps discovering complex patterns in the data.

-

128 units

-

ReLU activation

-

vii.

Concatenation: This layer combines the FM and DNN parts’ outputs. The model exploits the interplay between linear and non-linear features by merging these two components.

-

viii.

Output layer: This is the model’s last layer, which generates the prediction. Producing a probability value between 0 and 1, this dense layer with 1 unit and a sigmoid activation function is appropriate for binary classification problems.

Novel model design

Our study on "Intrusion Detection in SCADA Infrastructure incorporates several novel aspects in model design that contribute to its effectiveness and robustness. Below are the key design aspects:

-

i.

Hybrid DeepFM model architecture

The DeepFM model is a novel framework that uniquely integrates deep neural networks (DNN) and factorization machines (FM) advantages. Effectively capture second-order feature interactions necessary to comprehend pairwise feature connections when utilizing FM. To use DNN to identify sophisticated infiltration patterns, capturing higher-order interactions and complex patterns in the data is imperative. The model can utilize both linear and non-linear interactions, thanks to the seamless integration of FM and DNN, providing a comprehensive feature representation and interaction modeling method.

-

ii.

Advanced regularization techniques

Dropout layers are used in the DNN component to reduce overfitting. During training, units are removed randomly to help minimize overfitting and enhance the model’s generalization capacity. This ensures the model’s ability to handle fresh, untested input, which is crucial for real-world intrusion detection systems.

-

iii.

Optimized model architecture for tabular data

The DeepFM concept is particularly designed for tabular data, which is frequently found in SCADA systems. Standardization is used to ensure that each feature contributes equally to the model learning process. Meticulous planning of the quantity and dimensions of thick layers to strike a compromise between preserving computational effectiveness and capturing complexity. The model’s usefulness is increased by its easy adaptation to several tabular dataset formats outside of SCADA.

-

iv.

Comprehensive data preprocessing pipeline

A strict data preparation pipeline must be implemented to ensure high-quality input data. Used to standardize features, which is essential for neural network models. An 80–20 split maintains a sizable test set for assessment and ensures a substantial amount of training data, providing a reasonable approximation of the model’s performance.

-

v.

Concatenation of FM and DNN outputs

A unique method for merging the FM and DNN component outputs before to the last prediction layer. Permits the model to employ both interaction modes simultaneously by combining the outputs of the FM and DNN sections. This architecture better captures the complex connections and patterns in the data. Our study’s unique model design features greatly enhance the DeepFM model’s generalizability, accuracy, and resilience for SCADA system intrusion detection.

-

vi.

Model scalability

Although the DeepFM model is theoretically efficient and scalable, these assertions require empirical support from case studies or real-world implementations. One such scenario involves using the model to monitor an industrial energy grid in a real-time SCADA system. The system may encounter fluctuating data demands in this configuration, particularly during periods of high energy usage or cyberattacks when network traffic surges.

Experiment and results

To evaluate our model’s overall performance and generalization capabilities, we assess its training performance on a training dataset and its performance on test datasets and other databases. The training and testing performances are shown in Fig. 15.

Furthermore, our model appears to be effective in generalizing to unknown inputs, as indicated by the remarkable similarity between the training and validation accuracy curves. Instead of overfitting to the training set, this alignment demonstrates that the model has learned to capture the underlying patterns in the dataset. The consistency of training and validation accuracy favorably reflects the model’s robustness. It implies that the model can generalize its learning to new scenarios and that noise and outliers in the training data do not significantly impact its performance.

The absence of observable variations or gaps between the training and validation loss curves is one of the best signs indicating the absence of overfitting. This suggests that, rather than merely memorizing the training data, our model has successfully learned to generalize to new examples it has not yet encountered, striking a balance between complexity and generalization. The training and validation accuracy and loss performance curves provide valuable insights into the functionality and generalizability of our Deep Factorization Machine model for SCADA intrusion detection. The nearly identical training and validation accuracies, along with the constant training and validation loss trajectories, indicate that our model performs exceptionally well without overfitting the training set.

Model evaluation

The six metrics that are employed in this study provide a brief narrative.

-

i.

Accuracy: The accuracy shows the percentage of test cases identified correctly out of all test samples.

$$\text{Accuracy }=\text{ TP }+\text{ TN}/\text{ TP }+\text{ TN }+\text{ FP }+\text{ FN}$$(6) -

ii.

Precision: The accuracy metric measures the percentage of test samples with accurate labels among all the gathered instances.

$$\text{Precision }=\text{ TP }/\text{TP }+\text{ FP}$$(7) -

iii.

Recall: It goes under several other names, such as detection rate (DR), true positive rate (TPR), and sensitivity. It is the proportion of all malware samples in a test batch that were successfully identified.

$$\text{Recall }=\text{ TP}/\text{ TP }+\text{ FN}$$(8) -

iv.

F1 score: It shows the model’s harmonic average of recall and precision.

$$\text{F}1 = 2 *\text{ Recall }*\text{ Precision}/\text{ Recall }+\text{ Precision}$$(9)

-

v.

Confusion matrix: The performance of a classification model is sometimes explained by a table known as a confusion matrix. It presents an overview of the predictions made by a model for a particular dataset by comparing the predicted and true labels. The confusion matrix consists of four main parts:

-

TP: The positive class was accurately predicted by the model.

-

TN: The negative class was accurately predicted by the model.

-

FP: A Type I mistake occurred when the model mispredicted the positive class.

-

FN: A Type II mistake occurred when the model mispredicted the negative class.

-

vi.

ROC curve: The discrimination threshold of a binary classification model can be adjusted to demonstrate how diagnostic the model is, as shown by the ROC curve, a graphical representation. It is created by plotting the true positive rate (TPR) against the false positive rate (FPR) at various threshold values.

-

TPR: Also known as sensitivity or recall, TPR expresses the proportion of true positive cases the model correctly identifies.

-

FPR: The fraction of actual negative cases the model incorrectly identifies as positive is measured by the False Positive Rate or FPR.

The ROC curve visually represents the trade-off between TPR and FPR across various threshold values. A perfect classifier would have a ROC curve with a high sensitivity and low false positive rate that passes through the top-left corner of the plot (TPR = 1, FPR = 0).

The model hyperparameters for training the DeepFM model are presented in Table 6.

The model’s performance on unseen test data is as follows in Table 7.

The model appears to perform reasonably well on previously encountered datasets, as indicated by the above performance on all assessment criteria, which suggests the model’s potential for generalization. As illustrated in Figs. 16 and 17, we will utilize the ROC curve and confusion matrix to assess the model’s performance further.

According to the confusion matrix, nearly all regular and attack classes are correctly classified. It is also crucial to acknowledge that the dataset is highly unbalanced, demonstrating that the model effectively made accurate predictions on an unbalanced dataset. The dataset’s size was also huge, contributing to the model’s high accuracy. In the usual class, only 1400 samples are incorrectly predicted, whereas 1.3 million samples are correctly classified. Comparably, just 436 intrusion traffic instances are incorrectly classified. Although there is a noticeable imbalance in both classes, the model performance is still acceptable. The model’s performance was evaluated using the ROC curve, as shown in Fig. 17.

The AUC score is also 1.0, indicating no misclassification for either the normal or attack classes. This high accuracy can be attributed to the model’s novel FM and DNN parts function. We can utilize this model within the industrial SCADA framework as a state-of-the-art model for the cybersecurity of industrial instruments. To further test the model’s generalization and applicability, let’s evaluate it on other databases.

Figures 18 and 19 illustrate that the model’s performance is evaluated on both binary and multiclass data. Here, too, the performance is satisfactory. As mentioned in the data description section, some classes contribute as little as 0.001% to the dataset overall. Still, our model correctly classifies the data because it removes underfitting caused by data imbalance. Additionally, each class has sufficient data to train a model for that class.

Model evaluation on WUSTL-IIOT-2021 dataset

We examined the IIoT network data in the WUSTL-IIoT-2021 dataset to determine if it could be utilized for a cybersecurity study. Our IIoT testbed is the source of the information. Our testbed aims to reflect real-life industrial systems correctly while allowing users to attack them realistically. It took us 53 h to gather 2.7 GB of info. We cleaned and pre-processed the dataset by removing extreme outliers, corrupted values (i.e., invalid records), and missing values. The smaller copy of the information that we used and shared is just over 400 MB.

This dataset (Table 8) and Table 9 below have more features. This dataset has around 41 characteristics, compared to 6 in the prior dataset. Below are some features: With this data, we have tested the model’s success without changing its design or preprocessing. Table 10 illustrates the effectiveness of the plan.

The assessment measures also indicate the model’s remarkably high performance, with an accuracy of almost 98% even without fine-tuning of hyperparameters or model architecture, demonstrating the model’s capacity for generalization and robustness. Although this dataset contained more characteristics, only Sport, Mean, Ploss, SRCLoss, and Dport were considered the most significant features. The maximal sports correlation coefficient was 14%, although the highly connected dataset in the prior dataset had a 30% correlation, indicating a discrepancy in the model’s performance. Figures 20 and 21 display the model’s confusion matrix and ROC curve.

The ROC curve and confusion matrix further support the model’s correct performance. We test our model on a second dataset to confirm its superior generalization and resilience compared to other models. This helps us further validate the model’s performance.

HAI (HIL-based augmented ICS) security dataset

A Hardware-in-the-Loop (HIL) simulator that simulated the generation of steam turbine power and pumped storage hydropower, from which the HAI dataset was derived, was added to a real industrial control system (ICS) testbed. Using this pure industrial dataset, we evaluate the model’s performance without adjusting its hyperparameters or architecture. This is the model’s output with this dataset.

Table 10 above also indicates that the model’s performance is very high, at 95%. Although this dataset differs significantly from the prior ICS intrusion dataset, the model performed exceptionally well overall, indicating its capacity for generalization and robustness. This essentially shows the model’s performance, which is achieved more quickly. Figures 22 and 23 display the dataset’s confusion matrix and ROC curves.

The confusion matrix and ROC curves also suggest the model’s exceptional performance. The model achieved a satisfactory accuracy of around 95%, which is unprecedented for the model. It is also important to note that the model architecture is entirely unchanged. Still, due to the FM and DNN components, both low-order and high-order features are captured successfully, resulting in an effective model with good classification performance. The model also suggests that it can be applied in real-world scenarios and used to detect anomalies in Industrial SCADA environments.

The model’s accuracy across the entire dataset is very high, as demonstrated by the bar chart in Fig. 24 above. The model performs best, having been optimized, especially for the 2018 WUSTL-IIOT dataset. The accuracy of the WUSTL-IIOT dataset in 2021 is 98%, indicating the model’s potential for generalization, whereas the HAI security dataset yielded an accuracy rate of 95%.

Furthermore, the model’s performance is compared with that of state-of-the-art machine learning models, which are widely used for intrusion detection but not specifically in SCADA environments. The performance here is as follows.

In Table 11, we can see that even though state-of-the-art models, which have very high performance, are outstanding, their performance is significantly lower compared to our proposed model, suggesting that our model is not novel in this intrusion detection domain. Using both a deep learning model and a factorization mechanism, it still outperforms many state-of-the-art models.

The algorithm identifies the critical steps of data preprocessing, model initialization, model training, and model testing. A concise description of the algorithm contains the following points:

Step 1: DeepFM-Based Intrusion Detection Workflow Load Dataset: Load the dataset in CSV or database format, using WUSTL-IIOT-2018 as an example in this case. Neighborhood processing: Standardize features and train and test themselves.

Step 2: Model Definition: DeepFM model as a combination of FM component spanning the low-order feature interactions. DNN component of high-order feature learning. Compilation: Compile using Adam as an optimizer, cross-entropy loss, and accuracy as the evaluation metric.

Step 3: Training Loop (per epoch): Run through training batches to train the model. Calculate accuracy, confusion matrix, and ROC on test data. Provides performance visualizations when performance milestones are met (e.g., accuracy > 95%).

Table 12 presents a comparison of the complexity of intrusion models.

Besides, we have also included a complexity analysis of the proposed model: FM component: Pairwise feature interaction calculations are performed with a complexity of:

Where the number of features is n, and the embedding size is k. This evades the O(n2) computational expense.

Step 4: DNN component: The cost of forward propagation is

Li is the number of neurons in layer i, and m represents the total number of layers. Overall complexity:

Step 5: Performance validation: Such a balance ensures that DeepFM is capable of learning both low-order interactions (FM) and high-order feature abstractions (DNN) without being computationally prohibitive for near-real-time SCADA/ICS intrusion detection.

As another measure to validate the proposed DeepFM framework and address concerns about performance validity, we conducted additional experiments, including ablation studies, cross-dataset validation, and baseline comparisons. These longer analyses will provide more substantial evidence of the model’s strength, generalizability, and improved performance compared to existing procedures.

Step 6: Model efficiency estimation: To provide specific figures, we estimated the parameters and FLOPs of our most optimal model (DeepFM 3-layer with 256-128-64 units and k = 10).

To present definitive results, we have estimated the parameters and floating-point operations (FLOPs) of our fastest-acting model (DeepFM with 3 hidden layers, 256-128-64 units, k = 10). Table 13 presents the computational complexity of DeepFM compared to the baselines.

FM-only is of low complexity but sacrifices accuracy.

The DNN-only model is significantly larger, with a substantially greater number of FLOPs and slower inference.

The DeepFM hybrid introduces only a ~ 12 percent overhead over the DNN-only model, but is found to provide up to 2–4 percent accuracy gains.

Notably, inference time is approximately 1 ms/sample, which makes it suitable for short-latency SCADA implementations (where latencies of a few milliseconds are acceptable).

Complexity is theoretically linear in both the number of features and the number of hidden layer nodes, enabling the method to scale to large datasets.

Empirical thresholds demonstrate that DeepFM effectively balances accuracy and performance, training in a reasonable amount of time, and inferring quickly enough to support real-time intrusion detection.

The FM module has minimal additional cost compared to deep-only methods and substantial performance gains in recall and F1-score.

Model evaluation on Sherlock dataset

To better justify our methodology and enable its application to even more industrial cases, we have supplemented our experimental analysis with a larger and decidedly more relevant dataset of medium size. After examining current benchmark tasks, we have selected the Sherlock data set, which focuses on power grid intrusion detection, as it is recent, realistic, and well-creditable in the ICS sector.

Augmentation of the Sherlock dataset (power grid intrusion detection)

-

i.

Introduction to Sherlock.

In 2025, the Sherlock dataset was introduced, which is particularly well-suited for process-aware intrusion detection in power grid networks—a key research area in SCADA/ICS. It has been modeled through Wattson co-simulator; further, it also contains realistic attacks (such as state variables and measurement manipulation) in a modern power grid system. The use of Sherlock, along with its modern presentation of attack profiles and process simulation, enables a strong gateway to assess the generalization and robustness of intrusion detection models on cases that are not typical of usual network traffic. Table 14 shows the DeepFM performance on the Sherlock dataset.

The robustness of the F1-score (0.955) of this model on the Sherlock dataset demonstrates that it can identify minor flaws and process-level issues, while maintaining stable performance in dynamic multisensor ICS power grid environments. Figure 25 shows the multi-class ROC curve for the Sherlock dataset.

These plots are for the WUSTL-IIoT 2018, WUSTL-IIoT 2021, HAI, and Sherlock datasets, with a focus on the ROC curves. As we can see, our model achieved excellent performance in nearly all datasets, indicating its generalization ability and potential practical real-world usage for actual intrusion detection.

-

ii.

Cross-dataset evaluation

Here’s a visual comparison of the model’s versatility, showing WUSTL-IIoT-2018, WUSTL-IIoT-2021, HAI and Sherlock dataset side by side. Table 15 compares their performance across different datasets.

-

Diverse applicability: The applicability of Sherlock encompasses the concept that DeepFM can be scaled to other ICS areas, such as IoT-driven SCADA simulation, as well as power grid modeling.

-

Stability in various industrial scenarios: The results on the HAI Security Dataset emphasize the flexibility of DeepFM to address various ICS-related security issues, especially those related to building automation and control systems.

-

Performance variation insight although the overall performance is slightly lower on Sherlock than on the WUSTL-IIoT datasets, performance is higher overall due to the complexity and real-world details inherent in process-level simulation data.

-

Equitable detection ability: The model’s recall rate (0.959) demonstrates a high ability to detect process anomalies, and precision (0.952) correctly indicates a low ability to produce false positives. This balance is precarious when dealing with critical ICS, such as power systems.

-

No change in architecture: There is no change in architecture, but we are happy with the performance. This secures the capability of DeepFM to adapt to new datasets and tuning processes, which is of significant value in the application.

The high performance of our DeepFM model, coupled with its high generalizability across different SCADA and ICS environments, is supported by external testing on the Sherlock dataset, in addition to testing on the previously evaluated WUSTL-IIoT datasets. Our three databases benchmark demonstrates our contribution, as we have shown generality and domain independence, as well as intrusion detection performance that remains secure under various conditions.

-

iii.

Ablation study.

We examine the contributions of each component within DeepFM via an ablation study. Specifically, we performed the following experiments: (i) utilizing only the FM module, (ii) utilizing only the DNN module, and (iii) employing the integrated DeepFM model comprising both modules. This experiment highlights the significant advantages that the combined architecture offers over the individual sub-modules.

Table 16 shows the result of an ablation study on the WUSTL-IIoT-2018 and WUSTL-IIoT-2021 datasets using the FM-only, DNN-only, and DeepFM models. The FM-only model produces very high results on both sets of data, performing exceptionally well at low-order feature interactions, attaining accuracies of 0.942 and 0.963 in 2021 and 2018, respectively. This may be because they do not involve high-order structures. Nevertheless, it has incomplete recall values, indicating that the complex, nonlinear dependencies are challenging to represent. The DNN-only variant, in its turn, shows better performance with higher accuracy/F1-scores (0.968/0.966 in 2021; 0.971/0.963 in 2018), which suggests its capability of capturing high-order relationships. It ignores the more linear association.

The hybrid DeepFM consistently outperforms the separate modules. On WUSTL-IIoT-2021, it achieves an accuracy of 0.987 and an F1-score of 0.994, demonstrating both linear and nonlinear modeling capabilities. Analogously, DeepFM exhibits the best consistency (0.991) and balanced scores in each category on WUSTL-IIoT-2018. All the results show that DeepFM consistently outperforms standalone modules, with differences ranging from 2 to 3 percent, indicating that the complementary advantages of FM and DNN modules enable DeepFM to generalize better. These results confirm that the synergistic use of linear and nonlinear interactions is critical to achieving optimum performance in IIoT intrusion detection.

-

iv.

Cross-dataset validation

To test DeepFM’s ability to generalize, we ran additional experiments on two US datasets: WUSTL-IIoT-2021, HAI Security and Sherlock Dataset. These datasets have significantly different feature distributions, imbalanced class ratios, and varying patterns. If the model performs well on both, it suggests that it hasn’t overfit to any one of these datasets. Table 17 shows the cross-dataset performance of DeepFM.

The results indicate that DeepFM exhibits high performance, with an accuracy score that consistently remains in the range of 95.6% to 99.1%. Notably, the F1-score with the WUSTL-IIoT-2021 dataset is the highest (0.994), suggesting an outstanding precision-recall balance despite the dataset’s inherent heterogeneity. The same model performance is sustained even in a more challenging HAI dataset, which features more subtle sensor anomalies, with the F1-score remaining high at 0.954. Further, the Sherlock dataset targeted at detecting cybersecurity anomalies represents a reflection on DeepFM that it can make decisions in complex, real-life situations with precision of 0.954 and balanced measures, verifying its versatility and reliability. These results indicate that DeepFM can be effectively transferred and perform well in various industrial settings, demonstrating its applicability beyond a particular benchmark.

-

v.

Comparison with baseline studies

To demonstrate the novelty more convincingly, we compared the proposed DeepFM framework with similarly popular machine learning and deep learning models, including Logistic Regression, XGBoost, and Random Forest, as shown in Table 18. We have also included the outcomes reported in peer-reviewed articles published in recent years.

The comparison shows that although Random Forest achieves a performance of 98.9, DeepFM achieves an accuracy of 99.9; the latter outperforms all the baselines. In contrast to Logistic Regression and XGBoost, which primarily promote the learning of first-order and ensemble-based interactions, DeepFM can simultaneously learn low-order and high-order features within a comprehensive framework. This architectural benefit leads to increased performance, demonstrating the novelty and contribution of the proposed methodologies compared to other existing methods.

Together, the ablation, cross-dataset, and baseline performance give an in-depth overview of DeepFM’s performance advantages. The study of ablation confirms that the pairing of FM and DNN is necessary. The cross-dataset validation supports high generalization and robustness even in the presence of a distribution shift. Lastly, in this comparative analysis, it is observed that DeepFM contributes to increasing accuracy by a small margin, while also providing a consistent model that can be applied to other IIoT/SCADA datasets. These findings clearly confirm the soundness of the suggested model and set it above the current techniques.

Model performance under SCADA: high response and complex settings

Proper optimization enables the integration of the DeepFM model into SCADA systems, which require high availability and rapid response times. Although DeepFM requires a significant number of resources, its linear time complexity and effective handling of sparse features enable it to trade speed and power for efficiency. The model may be implemented for quick, real-time inference and trained offline for real-time intrusion detection, reducing computation during crucial SCADA processes. GPU or TPU acceleration can further improve response times, guaranteeing that the system’s latency requirements are satisfied. Methods such as model compression, pruning, and parallel processing can reduce resource requirements while maintaining accuracy, ensuring seamless integration without compromising SCADA performance. The computational burden of the model can be further distributed through distributed computing and failover procedures, assuring continuity in the event of model failure. Resource isolation strategies, such as containerization, can protect essential SCADA operations by preventing the model from using excessive resources. Despite its complexity, DeepFM’s improved detection accuracy over simpler models ultimately justifies its employment in SCADA contexts. It can enhance SCADA security while maintaining the system’s operational continuity, thanks to its high detection precision and improvements that minimize its impact on system performance.

Comparative analysis

The comparative analysis in Table 19 of various studies on the WUSTL-IIoT dataset highlights the advancements in intrusion detection and anomaly detection methodologies over recent years. The PSO + Bat Algorithm, when combined with Random Forest, demonstrated an accuracy of 95.68%7. More recent KNN-based models have achieved even better accuracy, at 96.67%11. Alternative methods, such as ensemble and hybrid algorithms, have been explored. For instance, Random Forest in combination with Isolation Forest and Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC) achieved a moderate accuracy of 93.57 percent21, which suggests the heterogeneity of traditional machine learning strategies on the specified dataset. Deep-learning models such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) and Feedforward Neural Networks (FNN) showed accuracy rates of 93.08 percent and 93.26 percent, respectively, which demonstrates that neural models are capable of capturing complex patterns, albeit not yet at 94 percent23.

Subsequent work on deeper learning models, including Outlier-Aware Deep Autoencoders, achieved much higher accuracy of up to 96.1 percent, indicating the promise of deep anomaly detectors specialized to that task24. Likewise, techniques such as Gradient Boosting and Support Vector Machine (SVM) attained accuracies of 96.5% and 95.85%, respectively30, whereas the Subspace Discriminant Algorithm reached an accuracy of only 93.1%28. These findings suggest that both traditional machine learning and deep learning models offer competitive yet slightly divergent performance on the WUSTL-IIoT dataset, with neither achieving an accuracy higher than 90%.

Conversely, our DeepFM-based model outperforms all the mentioned models, achieving an accuracy of up to 99.99% on the WUSTL-IIoT 2018 database. This makes it superior to DeepFM in modeling both low- and high-order interactions between features, which is crucial for detecting weak anomalies and intrusions in IIoT environments. The close accuracy implies that DeepFM improves generalization and performance compared to other models of the past, making DeepFM a leading choice in addressing the challenges of industrial IoT security. This significant performance disparity should highlight the prospect of adopting deep factorization machines in complex cybersecurity procedures.

Table 20 compares our proposed model, DeepFM, with the state-of-the-art methods. The results clearly show that our model consistently outperforms the other models (99.99% vs. 94–98% in the case of WUSTL-IIoT2018, 98% vs. 95% and 98% in the cases of HAI and WUSTL-IIoT2021, respectively). It also demonstrates strong generalization across datasets (98 vs 95 and 98 vs 95 in the cases of HAI and WUSTL-IIoT2021, respectively). This highlights the benefit of using a single architecture that can capture both low-order feature interactions (through FM) and high-order feature dependencies (through DNN).

This extended comparison substantiates that not only does our work demonstrate better accuracy, but it also generalizes well across multiple datasets, a feature that has never been reported in the literature before. The addition of these recent works reinforces the value of our work and highlights the innovativeness of using DeepFM in SCADA IDS.

Random Forest (RF) and K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) are classical machine learning methods used in SCADA datasets, providing relatively high accuracy rates (95 to 97 percent). The models, however, are limited in their ability to capture high-order feature interactions and must be heavily engineered in their feature specifications. Similarly, CNNs or Feedforward Neural Networks (FNNs) models can utilize hierarchical feature extraction. Still, they do not perform well in highly imbalanced datasets and tend to perform worse on categories with a low number of examples.

Furthermore, sophisticated hybrid systems, such as Outlier-Aware Deep Autoencoders and PSO-Bat Algorithm-based Random Forests, have attempted to enhance the detection of anomalies in industrial networks. Despite the use of advanced preprocessing or ensemble technologies, these methods often yield subpar performance when applied to various SCADA datasets or require substantial computational resources to execute. By comparison, DeepFM combines the use of Factorization Machines, which capture low-order interactions, and Deep Neural Networks, which capture high-order interactions, and has shown strong and consistent accuracy (99.99%) on diverse datasets without extensive feature engineering.

To gain a better understanding of the current state of the literature and its gaps, we have expanded our review by categorizing prior works according to their features, dataset type, model complexity, and scalability, as presented in Table 21 above. This table reveals not only the unique benefits of our proposed model but also positions it within a broader research environment, demonstrating that our model helps resolve both the problems of complexity and generalizability, which have been observed in many past studies.

The results shown in Table 20 indicate that although many conventional and hybrid models perform well in SCADA intrusion detection, they often struggle with high-dimensional data, sparse categorical features, and generalizing across different datasets. For instance, while Random Forest and KNN models can achieve high accuracy on specific datasets, they may fail in scenarios with class imbalance or complex feature interactions. Similarly, deep learning models like CNNs or autoencoders can provide advanced feature extraction, but they also face limitations in scalability and handling sparse tabular data.

When compared with this, the proposed DeepFM framework generally performs better by leveraging the advantages of factorization machine and deep neural networks. It can effectively capture both low- and high-order feature interactions without requiring extensive feature engineering. The proposed dual approach not only achieves better classification but also increases model generalization to multiple SCADA datasets, as evidenced by testing the method on the WUSTL-IIoT 2018, WUSTL-IIoT 2021, and the HAI datasets. In general, the extended analysis reaffirms the argument that the proposed methodology represents a significant advancement in accuracy, robustness, and adaptability in addressing the gaps that exist within the current state-of-the-art in the field.

Discussion

This work uses a DeepFM model to create an efficient intrusion detection system (IDS) for SCADA infrastructure. With approximately 99.99% accuracy in training and testing, we have shown that our DeepFM model is a very effective IDS for SCADA systems.

We chose the DeepFM model for its remarkable ability to combine factorization machines (FM) with DNN. This combined technique leverages the benefits of both methods. FM captures Second-order interactions between characteristics well, which helps see subtle trends in SCADA data that can indicate possible intrusion activities. DNN provides a comprehensive view of the underlying data distribution and can capture intricate, higher-order feature relationships. It also facilitates the model’s ability to identify complex invasion patterns. This combination enables DeepFM to model both linear and non-linear connections within the data, allowing it to consistently identify intrusion attempts in the complex and dynamic surroundings of SCADA systems.

We have employed extensive data preparation methods to ensure the stability of our model. To ensure that each feature contributed equally to the model’s learning process, we normalized all of the features using the StandardScaler. This phase is crucial for models based on neural networks, as it facilitates faster convergence and improved performance. The dataset was divided 80/20 between the testing and training sets. With this technique, we can evaluate our model on a sizable volume of data not used for training, providing a realistic picture of how well it would perform in actual situations.

Intrusion detection in ICS and SCADA systems has been extensively researched, with most current studies relying on either classic machine learning classifiers (e.g., Random Forest, SVM, Logistic Regression) or general-purpose deep neural networks (such as CNNs, LSTMs, and Autoencoders). Such methods tend to sample either low-order correlations (e.g., dependence of features) or high-order non-linear patterns, but rarely both on a unified scale. The gap will be filled by our work, which utilizes the DeepFM architecture that allows exploiting different combinations of low-order and high-order activated feature interactions based on the Factorization Machine (FM) and Deep Neural Network (DNN), respectively. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt to apply the DeepFM methodology in the SCADA/ICS intrusion detection context, offering a two-level feature interaction paradigm that enhances the generalization to the heterogeneous data.