Abstract

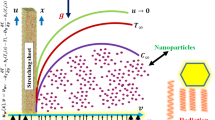

This article enunciates the effects of slip in an axisymmetric flow of non-Newtonian fluid via Buongiorno model with non-linear variable thermal conductivity and variable electric conductivity between two stretchable discs. Through the application of similarity transformations, the system of governing partial differential equations is systematically reduced and expressed in the form of coupled ordinary differential equations. The transformed system is resolved by HAM (homotopy analysis method) and the obtained results for skin friction coefficient, Nusselt number and Sherwood number are then compared with the results attained by SM (shooting method). The effect of several conspicuous parameters on velocity, thermal and concentration profiles are perceived through graphical data. The nanoparticles’ whirling between discs is assessed via thermophoretic diffusion and Brownian movement parameters in the flow of Casson nanofluid. Axial and radial velocity profiles enhance for stretching ratio and declines for Casson material parameter. The concentration profiles enhance when values of thermophoresis parameter are increased while an inverse trend for Brownian motion parameter is noticed. Temperature profile declines for rising values of Prandtl number and Reynolds number. The stretching behavior of discs is observed through tabular data by calculating engineering interest quantities at both lower and upper discs simultaneously. Both axial and radial velocity components show decreasing behavior due to increase in electric conductivity. The current analysis may be useful in many engineering applications including automobiles industries, hydraulics and mechanical engineering.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is much importance of magneto hydrodynamic flows in the field of industrial engineering, petrochemicals and mechanical systems such as manufacturing through MHD pumps, disc brake system in automobiles, MHD generators, ionized gasses flow, hydraulic systems, MHD levitating systems, and MHD propulsion aircrafts. Since viscous and electrically conducting fluid flows are generally stimulated by imposition of magnetic field that is why many researchers, for instance, Abdulaziz et al.1, Srinivas and Muthuraj2, Zhang et al.3, Ali et al.4 and Zhang5 discussed the magnetized flow phenomena in different flow assumptions. Casson liquid is one of the most popular pseudoplastic fluids because of its unique rheological configurations in an association of shear stress relative to strain factor. The plastic fluids are generally regarded as Casson fluids because of yield stress factor. Since at lower values of shear stress it is elastic solid and when it has critical stress value then it turns into Newtonian fluid. Tomato sauce, tooth paste, blood, honey, soup, synovial fluids, fruit juices and biological fluids are some common examples viscid fluids which are usually estimated through Casson fluid model. Eldabe et al.6 appraised the heat transference rate in the flow of Casson fluid between concentric cylindrical surfaces. Mukhopadhyay et al.7 conferred the numerical solution of mass transpiration of Casson liquid over pervious sheet with radiative flux effects. Upreti et al.8 presented a numerical investigation of Au–blood Casson nanofluid stagnation-point flow over a stretchable sheet in a permeable medium, emphasizing the roles of various slips, and nanoparticle geometry on flow velocity and heat transfer behavior. In another research, Upreti et al.9 have developed a mathematical model for hybrid Casson nano-liquid flowing around a horizontal cylinder, incorporating magnetic field, Ohmic heating, and thermal radiation effects, and solved the governing equations efficiently using the differential transformation method. Recently, Dinarvand et al.10 emphasized the potential of nanofluids and hybridized modifications to enhance flat tube car radiator performance by improving heat transfer and enabling compact designs, while also discussing the challenges such as stability and material compatibility. Furthermore, recent researches11,12,13,14 have revealed that the induced magnetic field significantly alters MHD nanofluid flows by modifying the Lorentz force and energy transport, thereby influencing both velocity and thermal distributions. It is disclosed in review of literature that there exists no such work in the field of magneto hydrodynamics (MHD) axisymmetric Casson nanofluids flow with assumptions of non-linearly varying thermal conductivity and electric conductivity till to date.

In pioneering studies on thermal behaviors of non-Newtonian fluids, Choi15 introduces the new concepts of non-Newtonian fluids known as nanofluids. These fluids are engineered by pouring small particles of size 1–100 nm into some pure liquid. The liquids containing nanoelements are termed as base fluids. Thermal conductivities of these fluids surprisingly increased due to suspension of nano-sized particles into the base liquids of smaller thermal conductivities. Casson fluid with nano sized particle is regarded as Casson nanofluid. Jamshed et al.16 considered the dynamics of Casson nanofluid under impact of thermal radiation over sheet taking unsteady case. Afterwards, Abdal et al.17 examined the flow of Casson nanofluid through a cylindrical surface by assuming porous medium. Casson nanofluid flow over sheet under the effect of fluid properties is discussed by Prasad et al.18. Berrehal et al.19 have recently conducted a numerical investigation on the flow behavior, heat transfer characteristics, and entropy generation of an aqua-based silver-copper oxide hybrid nanofluid past a downward-pointing rotating vertical cone.

The physical problems of flow in between discs has gained the great interest of engineers and researchers due to its lot of industrial and mechanical applications. Few applications of rotating bodies having disc shape are being utilized in medical equipment industry, rotating machinery, air cleaning machines, aerodynamic, crystal growth processes, thermal power generating system, gas turbine rotors and mostly prominent in computer storage devices. These applications of rotary discs stimulated the scientists of modern era to analyze flows of different fluids between discs with different thermal and magnetic settings. Initially, Fang20 got the solution for the rotating discs by revisiting Karman21. Fang found that the centrifugal force pumps in the ambient fluid due to rotating discs and Karman observed that the ambient pressure is higher than the pressure near the walls due to stretching discs. Transfer of heat and flow of fluid over vertically and rotating discs is analyzed by Turkyilmazoglu22. Casson fluid flow over rotating discs discussed by Khan and Hussain23. MHD Casson nanofluid flow over discs under the thermal radiation impact examined by Jawad et al.24. In recent years, several researchers have examined nanofluid flow over rotating discs to analyze the thermal characteristics of working fluids (see Refs.25‚26). These studies highlight the significance of rotating geometries in enhancing heat transfer performance for practical engineering applications.

Convective boundary conditions are very prominent in various engineering and industrial fields such as material dying, laser pulse heating, nuclear plants and turbines. The convective boundary condition captured the attentions of researchers because of its better thermal transference capability on flow of fluids in various disciplines. Aliakbarzadeh Kashani et al.27 numerically explored unsteady double-diffusive mixed convection flow of a salt-water nanofluid flowing through a vertical plate, incorporating Brownian motion and thermophoresis effects via Buongiorno’s two-component model. Zhang et al.28 discussed different irreversibilities on flow of Newtonian natured liquid through a convectively heated sheet and flow is taking place due to stretching effects in the sheet. Recently, Faridi et al.29 numerically calculated different newly defined Bejan numbers in the flow of pseudoplastic fluid through a magnetically influenced sheet assuming the convectively heated wall of the sheet. MHD boundary layer flow of Casson nanofluid through a stretchable thin sheet taking convective heat flux has been studied by Nadeem et al.30. Das et al.31 demonstrated magneto dynamics of nanofluid over a convectively heated sheet with a numerical technique constructed by shooting method. They assumed chemical reaction and linear radiative heat flux in the analysis. Likewise, Mansourian et al.32 examined heat transfer features of MHD hybrid nanofluid composed of Mn/Zn ferrite and cobalt ferrite nanoparticles in water over a stretched permeable sheet employing numerical methodology. Recent studies33,34 highlight that convective boundary conditions strongly affect heat transfer by controlling surface to fluid thermal exchange, underscoring their importance in realistic thermal flow modeling.

The Buongiorno model offers a more accurate demonstration of nanofluids behaviour than usual single-phase or two-phase models. It portrays two unique effects namely; the Brownian motion and the Thermophoresis between nanoparticles and the base fluids. The stability of nanofluids, variations in viscosity, thermal conductivity enhancement and convective heat transference capability of naofluids is better understood by applying the Buongiorno model. It reflects the independent movement of nanoparticles through Brownian motion and thermophoresis, encouraging more genuine results of heat transfer. The insertion of slip parameters pronounces more accurately the behaviour of thermal boundary layer, which is a key factor in various applications including cooling systems, petroleum refineries, microchannels, solar collectors, etc.

In many studies, thermal conductivity is supposed to be a constant in flow of nanofluids. Thermal conductivity of a material is the physical property which may vary due to change in temperature. Hazarika and Konch35 examined the thermal conductivity impact on two-dimensional MHD dusty fluid over a permeable plate. Kakac et al.36 deliberated the thermal variable conductivity effect in single phase transfer of heat in slip flow. The variable conductivity impact on pseudoplastic nanofluid flow through an asymmetric channel has been numerically analyzed by Hasona et al.37.

Electric conductivity is reciprocal of electric resistivity and is defined as the capability of a material to conduct electric current. It is also known as specific conductance. In metallic conductors, due to decrease in temperature the electric conductivity of material increases. The materials of high electric conductivity are plasma and metals while poor conductivity materials are glass, rubber, diamond, plastic, air etc. The electrical conductivity of distilled water is poor but its electric conductivity is changed by pouring small amount of sodium chloride. The instrument used to measure the electric conductivity of fluid is known as conductive metre device and its units are micro-mhos per centimetre. Sikdar et al.38 analyzed the electric conductivity of nanofluids. The electric conductivity impact on MHD flow is determined by Hossain and Gorla39. Hussain and Khan40 demonstrated the electric conductivity effect on thermal flow of Williamson nano-liquid amid rotatory discs in the presence of external magnetic field. The electric conductivity impact on flow of Casson nano-liquid over a linearly stretchable surface is observed by Obalalu et al.41. Recently, Behrouz et al.42 explored thermo-micropolar binary nanofluid flow over a permeable shrinking sheet with mixed convection and a lateral magnetic field using Tiwari–Das model, with alumina and copper nanoparticles in water. Alraddadi et al.43 implemented the Cattaneo-Christov heat flux theory to observe the thermal and electrical variable conductivities in the magnetized flow of Jeffery nanofluid amid a pair of stretched discs. Moreover, Hussain et al.44 analyzed the entropy generation rate in flow of Williamson nanofluid between stretchable discs under the impacts of magnetic field.

In present study, thermally radiative Casson nanofluid flow in the existence of non-linear thermal variable conductivity, effects of magnetic field and electric conductivity have been analyzed. It is considered that Casson nanofluid is flowing between two parallel discs. The Casson nanofluid is most valuable fluid because of its many real-life applications in food manufacturing, biological fluids, automobiles industries, etc. Although, researchers pointed out many investigations on MHD Casson nanofluids but MHD Casson nanofluid flow with features of non-linear thermal variable conductivity and variable electric conductivity with various slips has not been examined yet. The major motivation of this research is to fill this gap of scientific knowledge. Moreover, a novel comparison of numerical results is presented by applying homotopy analysis method (HAM) and shooting method (SM) simultaneously. The obtained results could be very helpful in the fields of energy production, extrusion processes, solar systems, HVAC systems, petrochemicals and automobile industries.

Mathematical formulation

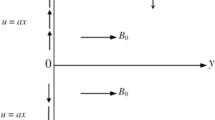

In this section we suppose axisymmetric steady and incompressible MHD flow Casson nanofluid with non-linear variable thermal conductivity \(K(T)\) and variable electric conductivity \(\sigma (T)\) between the pair of parallel stretching discs located at a distance \(d\) apart from each other.

The discs are supposed to be stretching linearly and direction of discs is taken opposite to transverse direction. Casson nanofluid occupies the space \(0<z<d\). Let \({B}_{0}\) be the constant magnetic field applied crosswise on fluid flow as demonstrated in Fig. 1. Under low magnetic diffusivity assumption, magnetic induction phenomenon has been ignored in this analysis. The cylindrical coordinates \((r,\theta ,z)\) are chosen for the current flow model. Since flow is assumed to be axisymmetric, the azimuthal velocity vanishes and all the quantities are obtained in the form free from \(\theta\).

The main flow assumptions are specified here as:

-

A two-dimensional, steady and incompressible is assumed.

-

An axisymmetric flow is considered between two stretchable rotating discs.

-

Buongiorno model is modified for estimation of Casson nanofluid.

-

The variable relations for thermal conductivity \(K\left(T\right)\) and electric conductivity \(\sigma (T)\) are considered.

-

Thermal radiative heat flux and external magnetic field effects are considered in this study.

-

Velocity slip and convective heat transfer conditions are imposed on the boundaries.

In the view of above stated flow assumptions, the governing equations of flow are given as43,44:

The symbols used in above equations are (\(u\),\(w\)) the axial and radial components of velocity, \(p\) the pressure, \(\mu\) the dynamic viscosity, (\(C_{1} , \, C_{2}\)) the nanoparticle’s concentration on respective discs, \(\rho\) the fluid density, \(D_{B}\) the Brownian movement diffusivity, \(D_{T}\) the thermophoresis diffusivity, (\(T_{1} , \, T_{2}\)) the temperatures at respective discs,\(T_{m}\) mean temperature of the fluid and \(\upsilon\) kinetic viscosity. Furthermore, expression for thermal radiations \({q}_{r}\) is followed by the works of Khan et al.45 defined as:

here \(\sigma\) and \(k\) are Stefan Boltzmann and absorption constants respectively. With the help of Taylor’s series, expanding \({T}^{4}\) and the below relation is obtained by neglecting terms consisting higher order of \({T}^{4}\).

\(K(T)\) designates the nonlinear thermal conductivity by following Alraddadi et al.43 which is expressed as:

where, the constant \(\varepsilon\) shows thermal dependent conductivity and \(K_{0}\) represents the ambient fluid conductivity parameter.

Variable electrical conductivity \(\sigma (T)\)46 is stated as:

where, \(f\left(\theta \right)=1+b\left({T}_{2}-{T}_{1}\right)\theta =1+b\theta\), here \(b\) is called electric conductivity parameter.

Using Eqs. (6) and (8) the Eq. (4) is modified as

Boundary conditions of proposed problem are of the form:

Where \({h}_{f}\) and \({h}_{m}\) are coefficients of heat and mass transfer respectively.

Similarity transformations relevant to this problem are stated as:

\(u=H{^{\prime}}\left(\upeta \right).ar\), \(w=H\left(\upeta \right).ad\), \(\theta \left(\eta \right)=\frac{T-{T}_{1}}{{T}_{2-{T}_{1}}}\),

The transformed system of governing equations of present problem is stated as

The transformed form of boundary conditions is demarcated as:

Where, \(\beta \left(={\mu }_{B}\sqrt{2{\pi }_{c}}/{p}_{y}\right)\) is the Casson material parameter,\({N}_{t}\left(=\frac{\tau {D}_{T}}{{T}_{m}}(\frac{{T}_{2}-{T}_{1}}{\nu })\right)\) is thermophoresis diffusion parameter, \({N}_{b}\left(=\tau {D}_{B}(\frac{{C}_{2}-{C}_{1}}{\nu })\right)\) is the Brownian motion parameters, and \({\lambda }_{1}\left(=\frac{{b}_{1}}{d}\right)\), \({\lambda }_{2}\left(=\frac{{b}_{2}}{d}\right)\) are slip lengths parameters. Some other non-dimensional numbers aroused in calculations are, \(R\left(=\frac{a{d}^{2}}{\nu }\right)\) Reynolds number, \(Le\left(=\frac{\alpha }{{D}_{B}}\right)\), Lewis number, \({P}_{r}\left(=\frac{\nu }{\alpha }\right)\), Prandtl number, \(Bi\left(=\frac{{h}_{f}d}{k}\right)\) Biot number, \(Ni\left(=\frac{{h}_{m}d}{k}\right)\) Nield number, and \(M\left(=\frac{\sigma {B}_{0}^{2}}{\rho a}\right)\) is Hartmann number.

Estimation of physical quantities

The relations for engineering attention quantities which are representative of thermal (the Nusselt number), solutal (the Sherwood number) and momentum (skin friction coefficient) behaviors of working fluid are modified in this section. The expressions for these physical quantities are formulated for both discs in view of basic laws.

Nusselt number

By application of Fourier’s law, heat transfer rate is computed very easily and calculated as

The Nusselt numbers are stated at both discs in the following form.

Sherwood number

The \(Sh\) Sherwood number at both discs is computed as.

where the mass flux is \({j}_{w}\) and Sherwood number in dimensionless form is stated as.

Skin friction

\({\tau }_{w}\) Is symbol of shear stress and its illustration on both discs respectively is expressed as

The coefficients of skin friction \({C}_{1f}\) and \({C}_{2f}\) at both discs are formulated as

Solution methodology

In the present article, the transformed set of equations of the flow model are resolved by employing the homotopy analysis method (HAM) as studied in pioneering research work of Liao47. It is a powerful semi-analytical technique that delivers a flexible and convergent approach for solving highly non-linear differential equations without demanding small parameters. Numerous studies have been conducted and documented in the literature48,49,50,51 that has employed the homotopy analysis method (HAM) in simulation of non-linear systems of equations. The basic steps for applying the homotopy analysis method are summarized in the flowchart Fig. 2.

The convergence of the solution

In this portion of study, we evaluate the convergence of series solutions of the modelled equations. The substitute parameters namely \({h}_{1}\), \({h}_{2}\) and \({h}_{3}\) are used to describe the variation in momentum, energy and concentration respectively of the fluid. The accuracy and convergence of HAM solution is obtained from these auxiliary parameters. The preparations of h-curves are very helpful in finding the suitable range of the auxiliary parameters and it is demonstrated in Fig. 3a–c. The solution shows better accuracy when \({h}_{1}\epsilon [-1.3, 0.2]\), \({h}_{2} \epsilon [-1.3, -0.8]\) and \({h}_{3} \epsilon [-1.4, -0.7]\). By our calculations, additionally determined the optimal values of auxiliary parameters such as \({h}_{1}=-0.1\), \({h}_{2}=-0.2\) and \({h}_{3}=-0.2\). The convergence of homotopy solution for different approximation order such as \({H}^{{\prime}{\prime}}(0)\), \({\theta }^{\prime}(0)\) and \({\phi }^{\prime}(0)\) is shown in Table 1. It is noticed that for HAM technique, by an increase in approximation order, the more accurate solution is obtained.

Comparison and code validation

The solution obtained by homotopy analysis method has been compared and validated through literature results given in works of Mustafa52 and Aldabesh et al.53 against various data set for parameter \(M\) arranged as in histogram Fig. 4. It noticed that our results are in an inclusive accordance with the existence one.

Results and discussion

A unique analytical technique, the homotopy analysis method (HAM) is applied to attain the approximate solution of above stated dynamical problem. With the help of numerous dimensionless parameters, the numerical outcomes for velocity, thermal and solutal equations of the proposed problem are discussed here. The symbols and designations of the dimensionless parameters involved are demonstrated as; (M) the Hartmann number, (Ni) the Nield number, (Nb) the Brownian motion parameter, \({(\lambda }_{1})\) the Deborah number, \((\gamma )\) the stretching ratio parameter, (Nt) thermophoretic diffusion parameter, (\(R\)) the local Reynolds number, (Le) the Lewis number, (Bi) the Biot number, (Pr) the Prandtl number and \((b)\) the electric conductivity parameter. The present flow model is established on basis of some assumptions on theoretical flow except any experimental data, so flow parameters are assigned arbitrary values. The outcomes of various non-dimensional parameters influencing the momenta, thermal and solutal profiles of modelled equations are represented and demonstrated through graphical data for a range of optimal values.

The influence of Hartmann number on velocity profiles is shown in Fig. 5a, b. Since the Hartmann number M is obtained by taking the ratio between viscous and electromagnetic forces. Hartman number and resistive force are directly proportional to each other. When large amount of magnetic force is utilized then as result higher Lorentz force is obtained which sufficiently resists the movement of fluid particles. Thus, both axial velocity Fig. 5a and radial velocity profiles Fig. 5b falloff from upper towards lower disc due to increase in M. The effect of ratio parameter on axial and radial velocity components is described in Fig. 6a and b correspondingly. The axial velocity component develops from lower disc’s flow region to upper disc’s flow region when stretching ratio increases which is given in Fig. 6a. While the radial velocity is described in Fig. 6b, as the stretching ratio parameter enhances, the radial velocity also rises up to a maximal region then it starts declining and this happens due to dissimilarity of stretching velocities of two discs.

Figure 7a and b are sketched to describe the impact of Casson parameter \(\beta\) on velocity curves. An axial velocity component drops from upper disc towards lower disc due to enhancement in Casson parameter \(\beta\), which is shown in Fig. 7a. Physically, an enhancement in Casson parameter relates to high flow viscosity in nature and as a result the velocity distribution declines. It is demonstrated in Fig. 7b that when \(\beta\) enhances then radial velocity declines from upper to lower disc. It is noticed that fluid flow improves under electric conductivity impact. The impact of electric conductivity parameter b on velocity profile is shown in Fig. 8a and b. The axial and radial velocity components decay from upper to lower disc due to upsurge in electric conductivity parameter which is demonstrated graphically in Fig. 8a and b respectively. Physically higher electrical conductivity intensifies the Lorentz force, causing a greater reduction in both radial and axial velocity components. Reynolds number R is introduced by Osborne Reynolds and is used to identify the flow type, either it is turbulent flow or a laminar flow. Since Reynolds number is the relation between inertial and viscous forces. Figure 9a and b are produced to demonstrate the impacts of Reynolds number and Prandtl number on temperature distributions. The temperature of fluid reduces from upper to lower disc when Reynolds number \(R\) is enhanced as shown in Fig. 9a. The relation between viscous and thermal diffusivity is termed as Prandtl number Pr. Ludwig Prandtl introduced this dimensionless number. Thermal diffusivity declines due to variation in Pr then as result the nanofluid temperature decreases. The appropriate values of Pr are helpful in control the heating and cooling processes. Few large Prandtl fluids having large thermal diffusivity and low thermal conductivity are namely engine oil, water etc. For growing values of parameter Pr gives a remarkable decline in fluid overall heat as depicted in Fig. 9b.

Figure 10a and b are mapped to discuss the thermal behavior nanoparticles. As shown in Fig. 10a, the fluid temperature decreases from the upper to the lower disc with an increase in the thermophoresis parameter Nt, since stronger thermophoretic forces drive nanoparticles away from hotter regions, reducing thermal energy retention. Similarly, Fig. 10b reveals that higher Brownian motion parameter Nb lowers the thermal profile from the upper to the lower disc, as enhanced random motion of nanoparticles promotes heat dispersion and accelerates thermal energy diffusion. The irregular motion of fluids’ molecules is categorized as Brownian movement which effects the temperature of fluid significantly. Biot number is useful in the calculations of heat transfer and denoted by Bi, furthermore it is dimensionless quantity. Biot number and coefficient of heat transference are directly related with each other. The proportion of thermal resistance inside body and surface of body is Biot number. Figure 11a and b show the effects of Bi and \(\varepsilon\) on thermal profiles. Figure 11a shows that the rising values of Bi remarkably boosts up the temperature of fluid from lower disc to upper disc. Likewise, the dimensionless parameter \(\varepsilon\) behaves with the thermal distributions as mapped in Fig. 11b.

Figure 12a and b are drawn to elucidate the effects of Lewis number Le and Nield number Ni on concentration profiles. The concentration profiles exhibit a decreasing trend from upper disc to lower one in response of increasing values of Le which is examined in Fig. 12a. In boundary layer region, comparative role of thermal diffusion and mass diffusion rates is seen against Lewis number Le. Since the ratio between Schmidt number and Prandtl number is designated as Lewis number. Thus, the heat diffusion rate will be greater than mass diffusion when \(Le>1.0\) while the diffusion rates of both mass and heat will be same when \(Le=1.0\). Therefore, thinness is observed in mass boundary layer and the enhancement in Lewis number results steeper in concentration profile. In Fig. 12b, it is established that concentration of suspended particles enhance due to increase in Ni. Physically, with increasing values of Nield number Ni, the surface mass flux dominates over molecular diffusion, thus enhancing nanoparticle transport into the fluid and resulting in elevated concentration profiles. The impression of Nt and Nb on concentration curves is examined in Fig. 13a and b. The concentration profile of nanoparticles enhances for growing values of Nt as shown in Fig. 13a and a significant decline in concentration of the working fluid for Nb as marked in Fig. 13b. It is assumed that nanoparticles’ concentration expression varies inversely against Brownian motion parameter. So, nanoparticle concentration declines due to increase in Nb. Higher values of Brownian movement while thermophoresis diffusion parameter perform a vital role in the dynamics of floating nanoparticles in the base fluid between two axisymmetric stretching discs. The thermal cooling of flow field can be condensed by adjusting the numerical values of Brownian movement parameter and thermophoresis diffusion parameter effectively.

Comparison of two different solutions obtained by HAM and shooting method for three engineering quantities are described through Tables 2, 3 and 4. The coefficients of skin friction at both lower and upper discs for several values of \(\gamma\) and \(\beta\), are calculated and compared as shown in Table 2. The two diverse techniques, the shooting method and HAM, are employed here to compute numerical as well as analytical solutions of the present problem. It is detected that maximum values are attained by wall shear stress due to variation of both dimensionless parameters. The variation in amount of Nusselt number at both discs for several values of dimensionless numbers such as Pr, Nb, Nt and Bi is displayed in Table 3. For numerous growing values of Pr, M and R, the Sherwood number at both discs is examined which is given in Table 4. It is perceived that the rate of mass transfer improves in response of growth in Pr.

Conclusions

The slip effect in axisymmetric Casson nanofluid flow between discs with non-linear thermal variable conductivity and electric variable conductivity is discussed in this article. A comparative analysis of homotopy analysis method and shooting method is presented here to evaluate the solution of the current problem. The findings of this research work provide valuable intuitions for engineering and industrial processes where MHD flows of non-Newtonian fluids are important, such as in polymer processing, metallurgical operations, automobile engines, cooling of electronic devices, and energy systems. The key outcomes of the study are:

-

When \(\gamma\) increases, axial velocity smoothly develops while the radial velocity increases to some extent then it tends to degenerate.

-

Both axial and radial velocity components show decreasing behavior due to increase in electric conductivity parameter \(b\).

-

When parameter \(\beta\) enhances and the remaining parameters are fixed, both the axial and radial components of velocity show a decreasing behavior.

-

The fluid’s temperature decreases with growing values of Pr.

-

Temperature profile shows increasing behavior for both Bi and \(\varepsilon\).

-

Concentration profiles decrease as Le enhances, while increase as Ni has grows.

-

Nanoparticles’ concentration shows increasing behavior with rising values of Nt but a decreasing trend is observed for Nb.

The results obtained from this study may be further helpful in developing magnetic levitation in automotive engines under controlled conditions to enhance thermal stability and fuel cost reduction.

Limitations and future recommendations

The present study is limited to a two-dimensional, steady, viscous and incompressible MHD Casson nanofluid flow with variable thermal and electrical conductivities, while other transport properties are assumed constant. The effects of induced magnetic field, Hall currents, nanoparticle aggregation, and sedimentation are not considered, and the analysis is performed under idealized boundary conditions without experimental validation. Future work may extend this model to three-dimensional and transient flows, incorporate electromagnetic effects such as Hall currents and ion slip, account for nanoparticle shape factor, agglomeration, and polydispersity, and include validation through experiments or advanced numerical simulations for broader applicability.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- \(b\) :

-

Electrical conductivity number

- \(B_{0}\) :

-

Magnetic field constant \(({\text{kg}}\,{\text{s}}^{ - 2} \,{\text{A}}^{ - 1} )\)

- \(B_{i}\) :

-

Biot number

- \(C_{p}\) :

-

Specific heat \(({\text{J}}\,{\text{mol}}^{ - 1} \,{\text{K}}^{ - 1} )\)

- \(C_{1}\) :

-

Nanoparticles’ concentration on lower disc \(({\text{kg}}\,{\text{m}}^{ - 3} )\)

- \(C_{2}\) :

-

Nanoparticles’ concentration on upper disc \(({\text{kg}}\,{\text{m}}^{ - 3} )\)

- \(D_{B}\) :

-

Brownian motion diffusivity \(({\text{m}}^{2} \,{\text{s}}^{ - 1} )\)

- \(D_{T}\) :

-

Thermophoresis diffusivity \(({\text{m}}^{2} {\text{s}}^{ - 1} )\)

- \(K_{0}\) :

-

Ambient thermal conductivity \(({\text{W}}\,{\text{m}}^{ - 1} \,{\text{K}}^{ - 1} )\)

- \(K(T)\) :

-

Variable thermal conductivity \(({\text{W m}}^{ - 1} {\text{ k}}^{ - 1} )\)

- \(k\) :

-

Mean absorption coefficient

- \(Le\) :

-

Lewis number

- \(M\) :

-

Hartmann number

- \(Ni\) :

-

Nield number

- \(N_{b}\) :

-

Brownian movement parameter

- \(N_{t}\) :

-

Thermophoresis parameter

- \(p\) :

-

Pressure \(({\text{Nm}}^{ - 2} )\)

- \(Pr\) :

-

Prandtl number

- \(Rd\) :

-

Thermal radiation

- \(R\) :

-

Reynolds number

- \(T_{1}\) :

-

Lower disc’s temperature (\({\text{K}}\))

- \(T_{2}\) :

-

Upper disc’s temperature (\({\text{K}}\))

- \(T_{m}\) :

-

Mean temperature (\({\text{K}}\))

- \(\beta\) :

-

Casson material parameter

- \(\rho\) :

-

Density of fluid \(\, {{({\text{kg}}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{({\text{kg}}} {{\text{m}}^{3} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{\text{m}}^{3} }})\)

- \(\sigma\) :

-

Stefan- Boltzmann constant

- \(\sigma (T)\) :

-

Variable electrical conductivity (\({{\text{S}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\text{S}} {\text{m}}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\text{m}}}\))

- \(\theta\) :

-

Dimensionless temperature

- \(\lambda_{1}\) :

-

Slip length as time relaxation

- \(\lambda_{2}\) :

-

Slip length as retardation time

- \(\eta\) :

-

Similarity variable

- \(\varepsilon\) :

-

Constant of conductivity

- \(\phi\) :

-

Concentration variable

- \(\mu_{0}\) :

-

Viscosity at zero shear rate

- \(\mu_{\infty }\) :

-

Viscosity at infinite shear rate

- \(\mu\) :

-

Viscosity of fluid \({{({\text{kg}}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{({\text{kg}}} {{\text{ms}}}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{\text{ms}}}})\)

- \(\gamma\) :

-

Stretching ratio

- \(\tau_{w}\) :

-

Wall share stress

References

Abdulaziz, O., Noor, N. F. M. & Hashim, I. Homotopy analysis method for fully developed MHD micropolar fluid flow between vertical porous plates. Int. J. Numer. Meth. Eng. 78, 817–827 (2009).

Srinivas, S. & Muthuraj, R. Effects of thermal radiation and space porosity on MHD mixed convection flow in a vertical channel using homotopy analysis method. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 15, 2098–2108 (2010).

Zhang, J., Li, B. & Chen, Y. Hall effects on natural convection of participating MHD with thermal radiation in a cavity. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 66, 838–843 (2013).

Ali, M. M., Mamun, A. A., Maleque, M. A. & Azim, N. H. M. A. Radiation effects on MHD free convection flow along vertical flat plate in presence of Joule heating and heat generation. Procedia Eng. 56, 503–509 (2013).

Zhang, X. Effect of contact resistance on liquid metal MHD flows through circular pipes. Fusion Eng. Des. 88, 2228–2234 (2013).

Eldabe, N. T. M., Saddeek, G. & El-Sayed, A. F. Heat transfer of MHD non-Newtonian Casson fluid flow between two rotating cylinders. Mech. Eng. 5, 230–250 (2001).

Mukhopadhyay, S., Vajravelu, K. & Van Gorder, R. A. Casson fluid flow and heat transfer at an exponentially stretching permeable surface. ASME J. Appl. Mech. 80, 054502 (2013).

Upreti, H., Mishra, S. R., Pandey, A. & Bartwal, P. Shape factor analysis in stagnation point flow of Casson nanofluid over a stretching/shrinking sheet using Cattaneo-Christov model. Numer. Heat Transf. B Fundam. 85, 1381–1397 (2023).

Upreti, H., Pandey, A., Lingwal, S. & Bartwal, P. Free convective flow of Casson hybrid nanofluid around a horizontal circular cylinder with thermal radiation using differential transformation method. Multidiscip. Model. Mater. Struct. https://doi.org/10.1108/MMMS-02-2025-0050 (2025).

Dinarvand, S., Abbasi, A. & Gharsi, S. A review of the applications of nanofluids and related hybrid variants in flat tube car radiators. Fluid Dyn. Mater. Proc. 21, 37–60 (2025).

Guedri, K. et al. Heat transfer in magneto-hybrid nanofluids with viscous and joule dissipation: A successive over relaxation analysis. Results Eng. 27, 106485 (2025).

Upreti, H., Bartwal, P., Pandey, A. & Makinde, O. Heat transfer assessment for Au–blood nanofluid flow in Darcy-Forchheimer porous medium using induced magnetic field and Cattaneo-Christov model. Numer. Heat Transf. B Fundam. 84, 1–17 (2023).

Faridi, A. A., Khan, N., Ali, K. & Inc, M. Impact of magnetic induction on the flow of Maxwell hybrid nanofluid comprising GO–TiO₂ and sodium alginate over a stretching sheet: A numerical study. Multiscale Multidiscip. Model. Exp. Des. 8, 257 (2025).

Krishna, M. V., Anand, P. V. S. & Chamkha, A. J. Heat and mass transfer on free convective flow of a micropolar fluid through a porous surface with inclined magnetic field and Hall effects. Spec. Top. Rev. Porous Media 10, (2018).

Choi, S. U. S. & Eastman, J. A. Enhancing thermal conductivity of fluids with nanoparticles. Proc. ASME Int. Mech. Eng. Congr. Expo. 66, 99–105 (1995).

Jamshed, W. et al. Evaluating the unsteady Casson nanofluid over a stretching sheet with solar thermal radiation: An optimal case study. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 26, 101160 (2021).

Abdal, S., Hussain, S., Siddique, I., Ahamdian, A. & Ferrara, M. On solution existence of MHD Casson nanofluid transportation across an extending cylinder through porous media and evaluation of priori bounds. Sci. Rep. 11, 7799 (2021).

Prasad, K. V., Vajravelu, K. & Vaidya, H. MHD Casson nanofluid flow and heat transfer at a stretching sheet with variable thickness. J. Nanofluids 5, 423–435 (2016).

Berrehal, H., Karami, R., Dinarvand, S., Pop, I. & Chamkha, A. Entropy generation analysis for convective flow of aqua Ag–CuO hybrid nanofluid adjacent to a warmed down-pointing rotating vertical cone. Int. J. Numer. Methods Heat Fluid Flow 34, 878–900 (2024).

Fang, T. Flow over stretchable discs. Phys. Fluids 19, 128105 (2007).

Karman, T. V. Über laminare und turbulente Reibung. Z. Angew. Math. Mech. 1, 233–252 (1921).

Turkyilmazoglu, M. Fluid flow and heat transfer over a rotating and vertically moving disc. Phys. Fluids 30, 063605 (2018).

Khan, N. A. & Husain, Z. Spinning flow of Casson fluid near an infinite rotating disc. MAC 20, 174–188 (2015).

Jawad, M., Saeed, A., Gul, T. & Bariq, A. MHD Darcy-Forchheimer flow of Casson nanofluid due to a rotating disc with thermal radiation and Arrhenius activation energy. J. Phys. Commun. 5, 025008 (2021).

Bartwal, P., Upreti, H., Mishra, S. & Pandey, A. Exploring the features of von Kármán flow of tangent hyperbolic fluid over a radially stretching disk subject to heating due to porous media and viscous heating. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 38, 2450135 (2023).

Upreti, H., Pandey, A., Pandey, A. & Bartwal, P. A comparative analysis of thermal and pressure distribution in rotating flows of von Kármán and Bödewadt using multivariate regression models: A case of machine learning techniques. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 166, 109118 (2025).

Aliakbarzadeh Kashani, D., Dinarvand, S., Pop, I. & Hayat, T. Effects of dissolved solute on unsteady double-diffusive mixed convective flow of a Buongiorno’s two-component nonhomogeneous nanofluid. Int. J. Numer. Methods Heat Fluid Flow 29, 448–466 (2019).

Zhang, X. et al. Successive over relaxation (SOR) methodology for convective triply diffusive magnetic flowing via a porous horizontal plate with diverse irreversibilities. Alex. Eng. J. 14, 102137 (2023).

Faridi, A. A., Ali, K., Khan, N., Jamshed, W. & Alqahtani, S. A. Relaxation analysis and entropy simulation of triple diffusive slip effect on magnetically driven Casson fluid flow. Int. J. Multiphase Flow https://doi.org/10.1080/02286203.2023.2301129 (2024).

Nadeem, S., Haq, R. & Akbar, N. S. MHD three-dimensional boundary layer flow of Casson nanofluid past a linearly stretching sheet with convective boundary condition. IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol. 13, 109–115 (2014).

Das, K., Duari, P. R. & Kundu, P. K. Numerical simulation of nanofluid flow with convective boundary condition. J. Ocean Eng. Sci. 23, 435–439 (2014).

Mansourian, M., Dinarvand, S. & Pop, I. Aqua cobalt ferrite/Mn–Zn ferrite hybrid nanofluid flow over a nonlinearly stretching permeable sheet in a porous medium. J. Nanofluids 11, 383–391 (2022).

Parvin, S., Nasrin, R., Alim, M. A., Hossain, N. F. & Chamkha, A. J. Thermal conductivity variation on natural convection flow of water–alumina nanofluid in an annulus. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 55, 5268–5274 (2012).

Gorla, R. S. R. & Chamkha, A. J. Natural convective boundary layer flow over a nonisothermal vertical plate embedded in a porous medium saturated with a nanofluid. Nanoscale Microscale Thermophys. Eng. 15, 81–94 (2011).

Hazarika, G. & Konch, J. Effects of variable viscosity and thermal conductivity on magnetohydrodynamic free convection dusty fluid along a vertical porous plate with heat generation. Turk. J. Phys. 40, 52–68 (2016).

Kakac, S., Yazicioglu, A. G. & Gözükara, A. C. Effect of variable thermal conductivity and viscosity on single-phase convective heat transfer in slip flow. Heat Mass Transf. 47, 879–891 (2011).

Hasona, W. M., Almalki, N. H., ElShekhipy, A. A. & Ibrahim, M. G. Combined effects of variable thermal conductivity and electrical conductivity on peristaltic flow of pseudo plastic nanofluid in an inclined non-uniform asymmetric channel: Applications to solar collectors. J. Therm. Sci. Eng. Appl. 12, 021018 (2020).

Sikdar, S., Basu, S. & Ganguly, S. Investigation of electrical conductivity of titanium dioxide nanofluids. Int. J. Nanoparticles 4, 336–349 (2011).

Hossain, A. & Gorla, R. S. R. Joule heating effect on magnetohydrodynamic mixed convection boundary layer flow with variable electrical conductivity. Int. J. Numer. Methods Heat Fluid Flow 23, 275–288 (2013).

Hussain, M. & Khan, N. Effects of variable thermal conductivity and electrical conductivity on flow of Williamson nanofluid between two parallel discs. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 35, 2150526 (2021).

Obalalu, A. M., Ajala, O. A., Abdulraheem, A. & Akindele, A. O. Influence of variable electrical conductivity on non-Darcian Casson nanofluid flow with first- and second-order slip conditions. Partial Differ. Equ. Appl. Math. 4, 100084 (2021).

Behrouz, M. et al. Mass-based hybridity model for thermomicropolar binary nanofluid flow: First derivation of angular momentum equation. Chin. J. Phys. 83, 165–184 (2023).

Alraddadi, I. et al. Implementation of Cattaneo-Christov heat flux theory for thermal conductivity variation impacts on Jeffery nanofluid flow between two stretchable discs. J. Radiat. Res. Appl. Sci. 18, 101419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrras.2025.101419 (2025).

Hussain, S. M., Ahmad, H., Hussain, M., Faridi, A. A., Khan, N. & Jamshed, W. Relaxation analysis of entropy generation in MHD flow of Williamson nanofluid between stretchable discs: Thermal engineering application. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. N J. Nanoeng. Nanosyst. (2025).

Khan, S. N., Shah, Q., Bhaumik, A. & Kumam, P. Entropy generation in bioconvection nanofluid flow between two stretchable rotating discs. Sci. Rep. 10, 4448 (2020).

Attia, H. A. Unsteady MHD flow and heat transfer of dusty fluid between parallel plates with variable physical properties. Appl. Math. Model. 26, 863–875 (2002).

Liao, S. Advances in the Homotopy analysis method (world scientific. Singapore https://doi.org/10.1142/8939 (2013).

Turkyilmazoglu, M. Analytic approximate solutions of rotating disc boundary layer flow subject to a uniform suction or injection. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 52, 1735–1744 (2010).

Abdelmalek, Z., Khan, S. U., Awais, M., Mustfa, M. S. & Tlili, I. Analysis of generalized micropolar nanofluid with swimming of microorganisms over an accelerated surface with activation energy. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 144, 1051–1063 (2021).

Al-Khaled, K., Khan, S. U. & Khan, I. Chemically reactive bioconvection flow of tangent hyperbolic nanoliquid with gyrotactic microorganisms and nonlinear thermal radiation. Heliyon 6, e03117 (2020).

Faridi, A. A., Khan, N. & Ali, K. A novel numerical note on the enhanced thermal features of water–ethylene glycol mixture due to hybrid nanoparticles (MnZnFe₂O₄–Ag) over a magnetized stretching surface. Numer. Heat Transf. B Fundam. 86, 804–826 (2023).

Mustafa, M. MHD nanofluid flow over a rotating disc with partial slip effects: Buongiorno model. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 108, 1910–1916 (2017).

Aldabesh, A. et al. Thermal variable conductivity features in Buongiorno nanofluid model between parallel stretching discs: Improving energy system efficiency. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 23, 100820 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University for funding this work through Large Research Project under grant number RGP2/207/46.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HZ and MH formulated the problem. HA and AAF solved the problem. HZ, MH, HA, AAF, NK, MEEA, KG and AHA computed and scrutinized the results. All the authors equally contributed in writing and proof reading of the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zahir, H., Hussain, M., Ahmad, H. et al. Solar radiation impact on nanofluid flow and heat transfer between magnetized stretchable discs with variable thermal properties. Sci Rep 15, 35847 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20704-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20704-4