Abstract

Motor learning is proposed to be associated with a minimization or optimization of physical and cognitive resources. Effort involves the voluntary investment of resources for task performance. While these two constructs are intrinsically linked, their relationship has never been empirically examined. This study aimed to investigate how the perception of effort evolves throughout the motor learning process. Thirty young adults volunteered in this study. Each participant had four visits to perform 10 blocks of a continuous tracking task on each visit. The sequences within these blocks were either random (control condition) or repeated (experimental condition). Following each block, participants rated the intensity of the effort invested to perform the task. Sequence-specific motor learning was observed, with the repeated outperforming the random sequence condition at the retention test. Perception of effort decreased only with sequence-specific motor learning, with a repeated measures correlation showing an association between these two variables. Our findings suggest that motor sequence learning reduces perception of effort. Thus, as sequence-specific task proficiency increases, individuals find the task less effortful. This link between learning a motor task and effort perception presents valuable opportunities for future research to investigate the behavioral and neural mechanisms underlying motor learning and effort.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Learning motor skills is integral to the very essence of human existence. At various stages of life, individuals must learn the motor skills necessary for, or that are beneficial to, daily life. Motor learning is associated with practice and experience that results in long-lasting changes in a person’s capability to perform a motor skill1. A motor skill is defined as the proficiency to attain a goal with the utmost certainty and minimal effort2. Motor learning is inferred from improvements in motor performance3. Motor performance is defined as the observable production of a voluntary motor action at a given moment1. Regardless of the learner’s current stage in the motor learning process4, accurately assessing motor learning requires evaluating the maintenance of performance improvements during a delayed retention test1.

Fitts and Posner’s 4 model outlines three key stages in motor skill learning: cognitive, associative, and autonomous. In the cognitive stage, the emphasis is on task comprehension, involving inconsistent and effortful performance with frequent errors. Transitioning to the associative stage involves linking environmental cues with necessary movements, reducing effort and variability, and enhancing error detection. Finally, the autonomous stage is characterized by nearly automatic skill execution, demanding minimal conscious effort3. Motor sequence learning, a critical form of skill acquisition, is the process of combining a series of movements into a single, fluid action5. This process comprises two key components: sequence-specific learning, which reflects an improvement in the practiced order of movements, and non-specific learning, which is a general improvement in performance regardless of the sequence5. In the early stages of motor sequence learning, brain resources are more heavily weighted toward prefrontal regions than motor-related areas, reflecting a higher demand for cognitive control6,7. Neuroimaging studies suggest that the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and premotor cortex are particularly active during the early stages of motor sequence learning8,9,10. As learning advances, the activity in these areas diminishes, suggesting the brain’s transition from effortful to more automated processing with increased proficiency7,8,11. The reduction in neural activation within these key regions likely reflects a diminished or optimized mobilization of resources required to perform the task9,12,13,14. Moreover, evidence related to the minimization of physical resources indicates that with practice, the central nervous system adapts and optimizes the patterns of muscle activity to make more efficient use of the motor system15. Taken together, it can be postulated that motor learning is associated with a minimization or optimization of physical and cognitive resources, highlighting a conceptual link between motor learning and effort.

While the literature across disciplines did not yet reach a consensus on a definition of effort16,17,18,19,20, one of the most used theoretical frameworks considers effort as a resource-based phenomenon. In this framework, effort could be defined as the voluntary allocation of physical and cognitive resources to perform, or attempt to accomplish, a task16,17,18,20,21. While the possibility to exhaustively and accurately measure the cognitive and physical resources voluntarily mobilised in a task remains debated18,19,20, there is a consensus on the interest of investigating the conscious experience of exerting effort, namely the perception of effort. The perception of effort corresponds to the experience of the resources invested in a task16,20,22,23. It can be described as the sensation of energy being exerted, accompanied by a feeling of strain and labor that intensifies as the individual tries harder16. The perception of effort is a common phenomenon in daily life and plays a critical role in regulating human behavior24. Evidence from exercise physiology, neuroscience, and psychology suggests that the perception of effort is generated by the brain’s processing of corollary discharge of the central motor command25,26. Corollary discharge is a neural signal produced by the premotor and/or motor cortex27,28,29. The ACC has been proposed as a key brain area in the regulation of effort and its perception23,30,31,32,33. Importantly, the ACC has extensive connectivity with the DLPFC and the motor cortex, while also having a critical role in cognition and motor action34. Taken together, the underlying mechanisms of effort and its perception and motor learning are suggestive of their potential association.

As (i) motor learning is associated with a minimization or optimization of physical and cognitive resources involved in a task6,15, and (ii) effort perception is proposed to reflect the resources allocated to task completion22,23, decreased perception of effort during the motor learning process would be a reasonable expectation. To the best of our knowledge, this relationship has never been empirically examined. In this context, this study aimed to address this gap in knowledge by investigating how the perception of effort evolves through the motor learning process. We hypothesized that the perception of effort will decrease during the process of motor learning.

Methods

Participants

Thirty young adults (50% female; age: 25.6 ± 3.7 years, height: 174.1 ± 9.2 cm, mass: 74.4 ± 11.4 kg, body mass index: 24.5 ± 2.5 kg/m2) volunteered to participate in this study. All participants were right-handed; 29 reported moderate to high levels of physical activity, while 1 participant reported a low level of physical activity. A sensitivity analysis performed in G*Power 3.1.9.7 with an alpha risk of 0.05 and a sample size of 30 indicated that we had an 80% chance to observe a medium effect size of f(U) = 0.368 (ηp2 = 0.119) or higher. None of the subjects had any known mental or somatic disorders. Each participant gave written informed consent prior to the study. All participants were given written instructions describing all procedures related to the study but were naive to its aims and hypotheses. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Experimental protocol and procedures were approved by the ethics committee of the Centre de recherche de l’Institut universitaire de gériatrie de Montréal.

Experimental protocol

This study involved a within-subject design. Participants visited the laboratory for four sessions over two weeks. As the time of day has been shown to influence motor learning35, all sessions were conducted at the same time of day ± 1 h. During the first session, participants completed questionnaires regarding handedness and physical activity36,37. Heart rate belts and electromyographic (EMG) electrodes were installed. Standardized instructions were provided to participants regarding the rating of perceived effort. After that, they engaged in two familiarization trials of the motor task, i.e., the continuous tracking task (CTT). Participants were asked to rate the intensity of their perceived effort to complete the familiarization trials to ensure they understood the construct of effort and how to report it. The familiarization trials were completed at the beginning of the first session only.

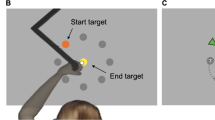

Following the familiarization trials, and for each of the sessions, participants performed 10 blocks of the CTT. A description of the blocks is presented in Fig. 1. The motor sequences within these blocks were either random (control condition; associated with general visuomotor control) or repeated (experimental condition; associated with sequence-specific learning). Following each block, participants rated the intensity of the effort invested to perform the task using a visual analog scale. Throughout all four sessions, physiological and performance variables were continuously measured during task completion, as described in the next sections. In both conditions: (i) motor skill acquisition was evaluated by observing improvements in performance during motor practice (i.e., Day 1)38; (ii) motor learning was inferred via assessing performance 24 h post-practice during a retention test (i.e., Day 2) 38. Sequence-specific motor learning was inferred via assessing performance of the random and repeated sequence conditions during a 24 h retention test (i.e., Day 2). The two conditions (random and repeated sequence) were performed in a pseudorandomized and counterbalanced order with 7 days in between the 2nd and 3rd session to avoid carryover effects (i.e., the influence of practice of a condition on the performance of the subsequent condition). Finally, participants completed a recognition test at the end of the fourth session to assess their explicit awareness of the sequences included in the CTT. A schematic of the protocol design is presented in Fig. 1.

Schematic of the protocol design. Panel a illustrates an overview of the sessions and presentation of the motor task (continuous tracking task) conditions: repeated sequence (experimental condition) and random sequences (control condition). Panel b illustrates a description of the blocks and rating of perceived effort. Panel c illustrates the timeline of the sessions in each condition. The order of the conditions was pseudorandomized and counterbalanced. Panel d illustrates the timing of the measurements of the other psychological variables.

Motor task: the continuous tracking task (CTT)

The CTT is a well-established motor task used to assess sequence-specific motor learning39,40,41,42. Participants performed adduction/abduction thumb movements, moving a custom joystick to the left and right to produce vertical upward and downward movements, respectively. These movements allowed the control of a cursor displayed on a computer screen (LG 29WL500-B, screen size: 29 inches, refresh rate: 75 Hz, aspect ratio: 21:9). The goal of the CTT was to track a visual target continuously oscillating vertically up and down, while moving at a constant rate (50 Hz) from left to right across the computer screen.

Familiarization. At the beginning of the first session, participants were familiarised with the procedures, without practising the sequences included in the experimental (repeated sequence) and control (random sequence) conditions. The familiarization included performing two 30 s trials. These trials consisted of the cursor moving in a straight line for 10 s in the middle of the screen, 10 s in a straight line at the top of the screen, and 10 s in a straight line at the bottom of the screen. This way, we ensured that the participants became familiar with the task without practicing the sequences.

Task description. After the familiarisation (session 1 only), and in sessions 2–4, participants completed the CTT. The CTT included 10 blocks of 5 trials in a repeated sequence (i.e., practice associated with motor sequence learning; experimental condition) or random (i.e., practice associated with general visuomotor control; control condition) sequences. The CTT involved 30 s trials, preceded by a 2 s normalization period when the cursor becomes level with the tracking target at the vertical midline of the screen. The repeated sequence remained consistent throughout the two sessions of the experimental condition, while the random sequences varied from trial to trial in the control condition, making them unpredictable. Random and repeated sequences were controlled for difficulty level in terms of range of motion and velocity of the target movements (for specific information please see40. Participants were not informed about the presence of random and repeated sequences. Tracking error for the repeated sequence reflects sequence-specific motor learning while changes in random sequence tracking error index non-specific improvements in motor control40.

Motor performance was assessed based on spatial accuracy and temporal precision40,43,44. Spatial accuracy was quantified as root mean square error (RMSE). A lower RMSE score denotes superior spatial tracking performance. Temporal precision was quantified as time lag. Time lag scores with larger negative values indicate greater time lag in tracking, whereas a zero value signified no time lag between participant movements and the target (i.e., accurate temporal performance). Motor learning was inferred based on decreases in RMSE and/or time lag during motor practice (i.e., Day 1) that were maintained at a delayed retention test (i.e., Day 2). Sequence-specific motor learning was inferred by lower RMSE and/or time lag in the repeated sequence condition compared to the random sequence condition at a delayed retention test (i.e., Day 2). All data from the CTT underwent processing using a custom MATLAB script (Version R2016a, The Mathworks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA). Individual trial data were aggregated to measure tracking performance within each block and enable comparisons across blocks. There was a 30 s period between blocks to rate the intensity of the perceived effort.

Recognition test. Following the last session, all participants underwent a recognition test to determine the degree of explicit awareness of the sequences included in the CTT. The recognition test consisted of watching a target moving on the computer screen. Participants had to decide if the sequence displayed was the repeated sequence or not. This procedure was performed with 10 sequences: 3 of them being repeated and 7 foils (random sequences). Individuals who identified the repeated sequence at a better than chance rate, i.e., 2 of 3 repeated sequences identified correctly as being recognized and 4 of 7 novel, random epochs identified correctly as never having been seen before, were considered to have gained explicit awareness of the repeated sequence45.

Perception of effort

The perception of effort reflects the experience of cognitive and physical resources being invested in the completion of a task16. Participants reported the intensity of their perceived effort to complete the CTT via a 100 mm visual analog scale with bipolar anchors (0 mm = “No effort at all”; 100 mm = “Maximal effort”). The following question was asked to assess the level of effort: “What is the level of effort you invested in completing the task?”. Participants were instructed to report the intensity of their perception by placing a mark along the line. The visual analog scale score was determined by the distance between the initial anchor and the participant’s marked position. At the beginning of each testing session, subjects received written instructions about the perception of effort. These instructions are available in the supplementary information. Given the distinction between effort and other sensations related to exercise23, participants were explicitly instructed to exclude ratings of additional sensations (e.g., fatigue, boredom, and discomfort) from their assessment of effort23,46. Participants reported their perceived effort after each block during the CTT practice.

Other psychological variables

Fatigue is a psychophysiological state associated with increased feelings of tiredness and lack of energy that can be caused by physical, cognitive, or combined physical and cognitive exertion47,48. Participants reported their level of fatigue via a 100 mm visual analog scale with bipolar anchors (0 mm = “Not fatigued at all”; 100 mm = ‘‘Extremely fatigued”). The following question was asked to assess the level of fatigue: “How fatigued are you at this moment?”. Participants were asked to place a mark along the line to indicate how they currently felt46. Fatigue was measured pre- and post-completion of the CTT.

Boredom is defined as a sensation that occurs when tasks are over- or under-challenging and feel meaningless49. Boredom can significantly challenge self-control by signaling that one’s resources should be redirected elsewhere, thereby making it more difficult to persist with an ongoing task48,49,50. Participants reported their level of boredom via a 100 mm visual analog scale with bipolar anchors (0 mm = “Not bored at all”; 100 mm = ‘‘Extremely bored”). The following question was asked to assess the level of boredom: “Were you bored during the task you just completed?” 46. Participants were asked to place a mark along the line to indicate their feelings. Boredom was measured after five blocks of the CTT (mid) and post-completion of the CTT.

Motivation is defined as the attribute that drives us to take action or refrain from action and has been proposed to influence performance21. Motivation to perform the CTT was measured with the motivation scale developed by Matthews et al51.. This questionnaire has seven questions on intrinsic motivation (e.g., “I wish to do my best”) and seven questions on extrinsic motivation (e.g., “I performed this exercise only because of an outside reward”). There are five possible answers for each question: (0 = not at all, 1 = a little bit, 2 = somewhat, 3 = very much, 4 = extremely). The score of each motivation ranges between 0 and 28. Motivation was measured before completion of the CTT.

Subjective workload. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration Task Load Index (NASA-TLX) was used to evaluate subjective workload52. The NASA-TLX is composed of six subscales: mental demand (how much mental and perceptual activity was required?), physical demand (how much physical activity was required?), temporal demand (how much time pressure did you feel due to the rate or pace at which the task occurred?), performance (how much successful do you think you were in accomplishing the goals of the task set by the experimenter?), effort (how hard did you have to work to accomplish your level of performance?), and frustration (how much irritating, annoying did you perceive the task?). The participants had to score each of the items on a scale divided into 20 equal intervals anchored by a bipolar descriptor (e.g., high/low). This score was multiplied by 5, resulting in a final score between 0 and 100 for each of the subscales. Participants reported their perceived workload after completion of the CTT.

Physiological variables

Complementary to the subjective measurements of effort, we measured changes in physiological variables including EMG and heart rate to infer changes in the mobilization of resources53,54,55.

Electromyography activity of the abductor pollicis brevis (APB) muscle was recorded continuously during CTT practice. Before placing the electrodes, the skin was shaved, cleaned with alcohol, and dried. Electrodes were placed over the APB muscle using the SENIAM recommendations56. Electromyography was recorded using a PowerLab system (26T, ADInstruments) with an acquisition rate of 2 K Hz and bandpass filtered with a range from 20 to 400 Hz and a notch filter with a center frequency of 50 Hz. Data were analyzed using the LabChart software (ADInstruments). The root mean square (RMS), a measure of EMG amplitude, was calculated offline in the software. Data were averaged for each block of CTT practice. To capture the maximal EMG activity of the APB muscle, participants were asked to perform two 3 s maximal voluntary contractions with verbal encouragement, pushing their dominant thumb against a table before performing the CTT. The greater maximal RMS amplitude of the two contractions was used for normalization of the EMG signal measured during CTT practice.

Heart rate was recorded continuously during CTT practice using a chest strap (Polar RS400, Polar Electro Oy, Kempele, Finland) with an acquisition frequency of 2 kHz. Data were analyzed off-line and averaged for each block of CTT practice. Heart rate frequency and heart rate variability were calculated. For heart rate variability, the root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD) between normal heartbeats was calculated using the Labchart heart rate variability add-in package. Heart rate variability indexes neurocardiac function and is generated by interactions between the heart and brain, reflecting the regulation of autonomic balance57.

Statistical analyses

The statistical analyses were conducted using Jamovi 2.3.16 and Jasp 0.19.1.0, and RStudio 2025.05.1. The graphics were created using GraphPad Prism 10.2.1, and RStudio 2025.05.1 using ggplot2 package. Data are presented as mean (95% confidence interval [CI]) unless stated otherwise.

Repeated measures ANOVA was used to test the main effect of time (Day 1 block 1, Day 1 block 10, Day 2 block 1, Day 2 block 10), condition (repeated, random) and time × condition interaction. The Mauchly’s test of sphericity was used to test for sphericity violation, and if any, the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was used to adjust degrees of freedom. Post-hoc comparisons were conducted using the Holm-Bonferroni correction in case of a significant main effect or interaction.

Following a significant time × condition interaction, and in line with the aim of the study, we performed the following 12 comparisons for the perception of effort, motor performance, and physiological data: (i) Within each condition: Day 1-block 1 vs. Day 1-block 10, Day 1-block 1 vs. Day 2-block 1, Day 1-block 10 vs. Day 2-block 1, Day 2-block 1 vs. Day 2-block 10. (ii) Between conditions: Day 1-block 1, Day 1-block 10, Day 2-block 1 and Day 2-block 10. Outliers in RMSE and time lag data were removed at the trial level for each block, based on conditions and days.

Repeated measures correlations were performed using the “rmcorr” package in R to examine the relationships between perception of effort and RMSE, as well as between perception of effort and time lag for both repeated and random sequence conditions, at four time points: Day 1-block 1, Day 1-block 10, Day 2-block 1 and Day 2-block 10, with participants treated as clusters.

Outliers were defined as values exceeding 2 standard deviations from the mean58. Statistical significance was set at \(\:\alpha\:=.05\). Effect sizes were calculated using partial eta squared (\(\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}\)) for ANOVAs and Cohen’s d for pairwise comparisons.

Results

Changes in motor performance during CTT practice and task awareness

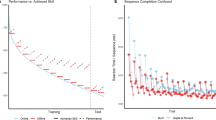

RMSE data is presented in Fig. 2A. Outliers accounted for 0.47% of data. A main effect of time was observed (\(\:{F}_{2.06,\:\:59.85}=160.78,p<.001,\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}=.847\:[0.765,\:0.884])\). On Day 1, RMSE decreased from block 1 to block 10 \(\:({t}_{29}=11.7,p<.001,d=1.083\:\left[0.603,\:1.564\right])\) and from block 10 on Day 1 to block 1 on Day 2 \(\:({t}_{29}=4.71,p<.001,d=0.336\:\left[0.098,\:0.574\right])\). RMSE decreased from block 1 on Day 1 to block 1 on Day 2 \(\:({t}_{29}=15.43,p<.001,\:d=1.419\:\left[0.831,\:2.008\right])\). Additionally, on Day 2, RMSE decreased from block 1 to block 10 \(\:({t}_{29}=6.33,p<.001,\:d=0.355\:\left[0.149,\:0.562\right])\). However, there was no main effect of condition \(\:({F}_{\text{1,29}}=1.29,p=.265,\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}=.043\:\left[0,\:0.237\right])\), and the time × condition interaction did not reach significance \(\:({F}_{1.35,\:39.16}=2.85,p=.088,\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}=.089\:\left[0,\:0.267\right])\).

Time lag data is presented in Fig. 2B. Outliers accounted for 0.42% of data. A time × condition interaction was observed \(\:({F}_{1.23,\:35.68}=4.46,\:p\:=.034,\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}=.133\:\left[0,\:0.330\right])\). On Day 1, there was a reduction in time lag during the repeated sequence condition from block 1 to block 10 \(\:{(t}_{29}=-3.44,p=.012,d=-1.039\:[-2.178,\:0.100])\), and from block 1 on Day 1 to block 1 on Day 2 \(\:{(t}_{29}=-3.69,p=.004,d=-1.119\:[-\text{2.275,0.038}]).\) On Day 2, the time lag decreased from block 1 to block 10 \(\:{(t}_{29}=-3.50,p=.009,d=-0.276\:[-\text{0.575,0.022}])\). There was less time lag in the repeated sequence condition than the random sequence condition on block 10 of Day 1 \(\:{(t}_{29}=-10.09,p<.001,d = -1.187\:[-1.859,\:-0.516])\), on block 1 of Day 2 \(\:{(t}_{29}=-8.25,p<.001,d=-0.748\:[-1.207,\:-0.288])\), and on block 10 of Day 2 \(\:{(t}_{29}=-11.65,p<.001,d=-1.018\:[-0.568,\:-0.469])\). Time lag decreased in the random sequence condition from block 1 of Day 1 to block 1 of Day 2 \(\:{(t}_{29}=-3.18,p=.028,d=-0.635\:[-1.378,\:0.109])\), and from block 10 of Day 1 to block 1 of Day 2 \(\:{(t}_{29}=-5.71,p<.001,d=-0.519\:[-0.910,-0.128])\).

Explicit awareness. The percent correct score for the repeated sequence was 75% and for the random sequences was 67%. Overall, 63% of the participants (n = 19) gained explicit awareness of the repeated sequence.

Changes in perception of effort during CTT practice

Perceived effort data is presented in Fig. 2C. A time × condition interaction was observed \(\:({F}_{3,\:87}=9.10,p\:<\:.001,{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}=.239\:\left[0.081,\:0.360\right])\). On Day 1, the perception of effort decreased during the repeated sequence condition from block 1 to block 10 \(\:{(t}_{29}=4.58,p<.001,d=0.929\:[0.115,\:1.744])\), and from block 1 on Day 1 to block 1 on Day 2 \(\:{(t}_{29}=6.26,p<.001,d=1.097\:\left[\text{0.317,1.877}\right]).\) On Day 2, the perception of effort decreased from block 1 to block 10 \(\:{(t}_{29}=3.23,p=.012,d=0.404\:[-0.062,\:0.870])\). However, the perception of effort did not change in the random sequence condition from block 1 to block 10 on Day 1 \(\:{(t}_{29}=0.66,p=1.000,d=0.129\:[-0.537,\:0.794]),\) and from block 10 on Day 1 to block 1 on Day 2 \(\:{(t}_{29}=1.48,p>.999,d=0.304\:[-0.414,\:1.022])\), nor did it change from block 1 on Day 1 to block 1 on Day 2 \(\:{(t}_{29}=2.25,p=.224,d=0.433\:\left[-0.256,\:1.121\right]).\) In block 10 of Day 2, the perception of effort was lower in the repeated sequence than the random sequence condition \(\:{(t}_{29}=6.00,p<.001,d=1.206\:\left[\text{0.327,2.086}\right])\).

Changes in Root Mean Square Error (RMSE, Panel a), Time lag (Panel b), and perception of effort (Panel c) during Day 1 (practice) and Day 2 (retention). $ Denotes a main effect of time. * Denotes a within-condition difference between blocks. † Denotes a between-conditions difference at the same block. One symbol for p <.05, two symbols for p <.01, and three symbols for p <.001. Data are presented as means ± 95% Confidence Interval.

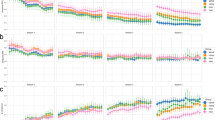

Correlation between CTT performance and perception of effort

Repeated measures correlation data are presented in Fig. 3. In the repeated sequence condition, we observed a correlation between RMSE and perception of effort (Panel a), \(\:{r}_{rm\:89}=\:0.57,\:95\%\:CI\:[0.417,\:0.697],\:p\:<\:.001\). Furthermore, a correlation was observed between time lag and perception of effort (Panel b), \(\:{r}_{rm\:89}=\:-0.46,\:95\%\:CI\:[-0.605,\:-0.276],\:p\:<\:.001\).

Conversely, in the random sequence condition, neither the correlation between RMSE and perception of effort (Panel c), \(\:{r}_{rm\:89}=\:0.11,\:95\%\:CI\:[-0.099,\:0.308],\:p\:=\:.305\), nor between time lag and perceived effort (Panel d), \(\:{r}_{rm\:89}=\:-0.15,\:95\%\:CI\:[-0.348,\:0.054],\:p\:=\:.147\), reached statistical significance.

Correlation between motor performance and perception of effort assessed at block 1 and 10 of both Day 1 (practice) and Day 2 (retention). Panel a illustrates the correlation between RMSE and perception of effort in the repeated sequence condition. Panel b illustrates the correlation between time lag and perception of effort in the repeated sequence condition. Panel c illustrates the correlation between RMSE and perception of effort in the random sequence condition. Panel d illustrates the correlation between time lag and perception of effort in the random sequence condition.

Changes in the perceived workload during CTT practice

Subjective workload data is presented in Fig. 4. A time × condition interaction was observed for NASA mental score \(\:({F}_{1,\:29}=5.18,p\:=\:.030,{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}=.152\:\left[0,\:0.373\right])\). Participants reported a lower mental demand in the repeated sequence condition from Day 1 to Day 2 \(\:{(t}_{29}=3.496,p=.002,\:d=0.340\:[0.037,\:0.643])\). A time × condition interaction was observed for NASA effort score \(\:({F}_{1,\:29}=6.77,{p\:=\:.014,\eta\:}_{p}^{2}=.189\:\left[0.007,\:0.411\right])\). The effort subscale decreased in the repeated sequence condition from Day 1 to Day 2 \(\:{(t}_{29}=4.265,p=.001,\:\:d=0.662\:[0.158,\:1.166])\), and was lower than the random sequence condition on Day 2 \(\:{(t}_{29}=3.193,p=.006,\:\:d=0.679\:[0.026,\:1.333])\). A main effect of time was observed for NASA temporal score \(\:{({F}_{1,\:29}=25.10,p\:<\:.001,\eta\:}_{p}^{2}=.464\:[0.183,\:0.633]\)). The temporal demand decreased in both conditions from Day 1 to Day 2 \(\:{(t}_{29}=5.01,p<.001,\:\:d=0.311\:\left[\text{0.159,0.463}\right])\). However, we observed no significant effects for NASA physical score, performance score, and frustration score (all p’s > 0.087 and \(\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}<.098\:\)).

Changes in perceived workload during Day 1 (practice) and Day 2 (retention). (Panel a) Illustrates NASA-TLX mental demand. (Panel b) Illustrates NASA-TLX physical demand. (Panel c) Illustrates NASA-TLX temporal demand. (Panel d) Illustrates NASA-TLX performance. (Panel e) Illustrates NASA-TLX effort. (Panel f) Illustrates NASA-TLX frustration. *** Denotes a within-condition difference between the two days (p <.001). $$$ Denotes a main effect of time (p <.001). †† Denotes a between-conditions difference in the same block (p <.01). Data are presented as means ± 95% Confidence Interval.

Changes in physiological variables during CTT practice

Raw EMG RMS data is presented in Fig. 5A. A time × condition interaction was observed \(\:({F}_{3,\:75}=3.68,p=.016,\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}=.128\:\left[0.004,\:0.247\right])\). On Day1, raw EMG RMS decreased from block 1 to block 10 in the repeated sequence condition \(\:{(t}_{25}=3.73,p=.001,\:d=0.421\:[-0.024,\:0.866])\). On Day 2, the raw RMS decreased from block 1 to block 10 in the random sequence condition \(\:{(t}_{25}=2.84,p=.018,\:d=0.366\:[-0.110,\:0.783])\). Analysis included 7 missing data points leading to the exclusion of 4 participants from the repeated measures ANOVA analysis.

Normalized RMS data is presented in Fig. 5B. There was no main effect of condition \(\:({F}_{\text{1,25}}=0.01,p=.910,\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}=.001\:\left[0,\:0.078\right])\), time \(\:({F}_{2.07,\:51.78}=2.78,p=.069,\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}=.100\:\left[0,\:0.246\right])\), and the time × condition interaction did not reach significance \(\:({F}_{\text{3,75}}=2.28,p=.085,\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}=.084\:\left[0,\:0.190\right])\). Analysis included 7 missing data points leading to the exclusion of 4 participants from the repeated measures ANOVA analysis.

Heart rate frequency data is presented in Fig. 5C. There was no significant time × condition interaction \(\:({F}_{1.45,\:40.50}=0.07,p=.865,\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}=.003\:\left[0,\:0.070\right])\), nor was there a main effect of time \(\:({F}_{1.78,\:49.94}=2.66,p=.085,\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}=.087\:\left[0,\:0.236\right])\). Finally, the main effect of condition did not reach significance \(\:({F}_{\text{1,28}}=3.77,p=.062,\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}=.119\:\left[0,\:0.342\right])\). Analysis included 1 missing data point leading to the exclusion of 1 participant from the repeated measures ANOVA analysis.

Heart rate variability data is presented in Fig. 5D. There was a main effect of condition \(\:({F}_{1,\:15}=5.52,p=.033,\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}=.269\:\left[0,\:0.537\right])\). RMSSD was higher in the repeated sequence condition compared to the random sequence condition \(\:{(t}_{15}=-2.35,p=.033,\:d=-0.446\:[-0.887,-0.006])\). There was no main effect of time \(\:({F}_{1.92,\:28.80}=2.29,p=.121,\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}=.132\:[0,\:0.330]\), and no time × condition interaction \(\:({F}_{3,\:45}=1.83,p=.156,\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}=.108\:\left[0,\:0.248\right])\). Analysis included 44 missing data points leading to the exclusion of 11 participants from the repeated measures ANOVA analysis.

Changes in raw (Panel a) and normalized by maximal voluntary contraction (MVC, Panel b) electromyographic (EMG) signal of the abductor pollicis brevis, heart rate frequency (Panel c), and variability (Panel d) measured with the root mean square of successive differences between normal heartbeats (RMSSD) during Day 1 (practice) and Day 2 (retention). *** Denotes a within-condition difference between the two days (p <.001). ** Denotes a within-condition difference between the two days (p <.01). Data are presented as means ± 95% Confidence Interval.

Results of fatigue, boredom, and motivation, are presented in the Supplementary Information document (see Supplementary Figure S1 online).

Discussion

The main aim of the present study was to test the hypothesis that the perception of effort will decrease during the process of motor learning. Confirming our hypothesis, the perception of effort decreased in the repeated sequence condition, and to a greater extent than the random sequence condition. Moreover, the greater decrease in the perception of effort in the repeated sequence condition was maintained at the delayed retention test (i.e., Day 2). This same pattern of decreased perception of effort was not found in random sequence condition. This indicates that the reduction in the perception of effort occurred with sequence-specific motor learning demonstrated by sequence specific performance at the retention test (i.e., Day 2). To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to demonstrate a reduction in the perception of effort during the motor learning process. This observation could motivate future research to explore the underlying neurophysiological mechanisms and clinical implications of the relationship between motor learning and the perception of effort.

Perception of effort decreased with sequence-specific motor learning

To address our hypothesis that the perception of effort decreases during the motor learning process, it was necessary to demonstrate that learning of the motor task occurred. Importantly, we observed sequence-specific motor learning following a single session of practice (i.e., Day 1) at a 24 h retention test (i.e., Day 2), consistent with previous studies using the CTT39,59,60. This was reflected by the greater improvement in temporal precision (less time lag) in the repeated compared to the random sequence condition, which was maintained at our delayed retention test (Day 2). Although the change in spatial accuracy (measured with RMSE) in the repeated compared to the random sequence condition did not reach statistical significance, this is consistent with previous work that demonstrated changes in time lag are reflective of rapid improvements in sequence-specific motor performance within a single practice session40,44. Sequence-specific improvements in RMSE can require multiple CTT practice sessions that may not be captured after a single practice session39.

We found that sequence-specific motor learning occurred with a decrease in the perception of effort. Additionally, we conducted repeated measures correlation analyses to directly explore the relationship between sequence-specific motor learning and the decrease in perception of effort. Our findings revealed a significant correlational relationship between improved performance and decreased perception of effort in the repeated sequence condition. This correlation between improved performance and decreased perception of effort in the repeated sequence condition further highlights the relationship between sequence-specific motor learning and reduced perception of effort. This correlation suggests that the perception of effort may be a key underlying mechanism during the process of motor learning, which may influence ongoing performance and long-term skill retention. Our observed reduction in perceived effort is in line with Fitts and Posner’s classic model of motor learning stages4. As participants progressed through the process of learning a motor task, the cognitive load and effort associated with task performance diminished. This decreased cognitive demand likely contributed to the reduced perception of effort reported by our participants. Thus, the findings of our study align with Fitts and Posner’s model, demonstrating the combination of decreased cognitive demands and improved motor proficiency culminates in a lower perception of effort. Additionally, participants reported their perceived workload to perform the CTT. The analysis revealed that motor sequence learning caused a significant reduction in participants’ cognitive demand and effort. These results further support the idea that motor sequence learning lowers the cognitive load and perceived effort required for the task.

A hallmark of learning new motor skills is that one progresses from an initial stage that is highly attention-demanding to an advanced stage where the skill operates more automatically12. This reduction in attentional demand is supported by a meta-analysis of neuroimaging data8 showing that motor sequence learning is associated with a consistent decrease in the DLPFC, ACC, and premotor cortex activity. Additionally, motor learning is marked by a robust pattern of activity shifting from prefrontal and associative areas in early practice to the sensorimotor areas with increased practice8,61,62. The decreased activity in prefrontal areas (e.g., DLPFC, ACC) during the motor learning process and the shift from associative to sensorimotor cortices can be partly interpreted as reduced resource mobilization. This is consistent with the view of ‘attention to action’ 6, i.e., activity in certain brain regions decreases when the task becomes more automatic and attentional demands are reduced. Also, it is suggested that the ACC is an important cerebral structure involved in the perception of effort63,64. Moreover, research indicates that the DLPFC plays a crucial role in exerting mental effort65,66 and is believed to contribute to effort-based decision-making in coordination with other regions, such as the ACC67,68. As the same regions that undergo shifts in activity during the early stages of motor learning are proposed to be involved in the generation or regulation of the perception of effort, it is plausible that the reduced activation in these brain areas may underlie the observed decrease in the perception of effort in the current study. Future studies could more directly investigate the common brain region activity associated with motor learning and the perception of effort.

Perception of effort decreased with repeated but not random sequence practice

The concept of chunking can be a plausible explanation as to why the perceived effort was lower in the repeated sequence. Humans can learn complex sequences of temporally ordered actions by grouping them into integrated units, known as chunks69,70,71. For example, when we first learn to drive or type, our actions are slow and prone to errors. Yet, with practice, tasks like shifting gears or typing letters become more seamless, as we begin to perform sequences of actions as a single unit rather than as distinct, isolated steps. Initially, when learning a new skill, it is believed that we retrieve and execute each action in a sequence one at a time72,73. Over time, we learn to integrate these once-separate movements into cohesive chunks71. Eventually, each chunk can be retrieved from memory and executed as a unified action, allowing us to perform complex tasks with greater ease and efficiency4,74,75,76. A key assumption in sequential behavior is that chunking can ease the cognitive burden on sequence planning and execution77,78,79. Although there is no literature on chunking and how it can affect the perception of effort, Kahn et al.80, showed that chunking can reduce subjective workload in complex tasks. Chunking the repeated sequence into one unit can reduce the need for mobilization of additional resources81 which in turn can lead to a lower perception of effort. However, random sequences cannot theoretically be chunked due to their variable nature. As a result, each element in the random sequence is treated as isolated and independent from previous or subsequent stimuli41. The improved performance in the random condition likely reflects participants’ enhanced motor control to track a moving target in general. However, in the repeated sequence condition, in addition to the improved motor control to perform the task, participants learned the repeated sequence.

The majority of participants in this study gained explicit awareness of the repeated sequence. Cognitive strategies may have contributed to the learning we see in the repeated sequence and the reduced perception of effort. When participants consciously recognized the sequence, they could have anticipated and executed the task more easily, potentially via chunking82,83. Also, recognizing patterns in a task enhances the ability to perform it more efficiently83,84, potentially leading to a reduction in perceived effort. Research suggests that learned sequences primarily reflect the cognitive properties of the task79,85 indicating that motor sequence learning reduces the cognitive load required for task performance. Consequently, the lower perception of effort in the repeated sequence condition likely reflects a reduced cognitive load rather than a physical one. This idea is supported by our data on the perceived workload during CTT practice. Participants reported a lower mental workload during motor sequence learning reflecting a reduction in participants’ cognitive demand and effort. However, the physical workload remained similar between the two conditions. Theoretically, a slight decrease in perceived effort should have been observed in the random condition as well, given the enhanced motor control and associated reduction in tracking error. However, the observed decrease didn’t reach significance, possibly due to the limited sensitivity of the scale in detecting such subtle changes in perceived effort.

Decreased mobilization of resources occurred with motor learning

Changes in physiological variables including heart rate and EMG were measured to infer changes in the mobilization of resources during the motor learning process53,54,55. Traditionally, EMG has been employed as a proxy of the central motor command54,86,87 and has been shown to be closely linked to the perception of effort22,54,88. We observed a reduction in the raw APB muscle RMS amplitude during Day 1 in the repeated sequence condition and during Day 2 in the random sequence condition. However, this reduction was not confirmed with normalized EMG results. Consequently, our EMG results do not suggest a minimization of resources at the muscle level. Future studies should replicate the current study using different joints (e.g., the wrist), enabling the measurement of both agonist and antagonist muscle activity to better assess potential changes in EMG activity.

While no change in heart rate frequency was observed, a higher heart rate variability was observed during the repeated sequence condition compared to the random sequence condition. However, these findings should be interpreted with caution, as they are exploratory and warrant careful consideration before drawing definitive conclusions. Heart rate variability offers insight into the nervous system’s capacity to regulate homeostatic responses, adapting to the physiological and psychological demands of the current situation89. Heart rate variability was measured using the RMSSD of the beat-to-beat interval90. Higher RMSSD indicates greater parasympathetic nervous system activity associated with a more relaxed state and better autonomic flexibility91. Increased RMSSD with sequence-specific motor learning in the current study suggests that as individuals became more proficient in the motor task, their physiological state became more relaxed and efficient57,91.

The absence of clear minimization of physical resources in this study could stem from the dominance of cognitive rather than physical demand in the task used in this study. The perception of effort in this task may be more closely tied to the cognitive load rather than the physical load, due to the relatively simplistic nature of the CTT performed in the current study, which involved few physical resources using a single thumb joint to manipulate a joystick. In tasks like the CTT, where cognitive demands decrease during the performance of the repeated sequence, the perception of effort may decrease even if physical exertion, as measured by heart rate and EMG, does not change significantly. The different sensitivity to task specificity can explain this mismatch between the perception of effort and the physiological variables. The subjective experience of effort might be more sensitive to the cognitive aspects of motor learning, such as sequence familiarity or the ease of processing a repeated sequence. In contrast, physiological measures (e.g., heart rate and EMG activity) during motor task practice may reflect overall physical exertion levels, which might not vary as much between repeated and random sequences. Future studies should further investigate these speculative interpretations.

Limitations and perspectives

While we observed a specific decrease in perceived effort during the repeated sequence condition, we failed to capture evidence of an objective manifestation of the resources involved in the task. Our results, and those of others, support the notion that motor sequence learning lowers the cognitive load of the task. In this case, we could expect a greater minimization of cognitive resources compared to physical resources. Given that we only measured physical resources, with specific emphasis on muscle recruitment (with EMG) and cardiac responses (with heart rate), it is not surprising that a clear minimization of physical resources was not observed. We suggest that future studies specifically interested in motor sequence learning and its effect on the perception of effort carefully monitor brain activity and/or excitability while performing a motor task to capture the minimization of cognitive resources. Future work could use transcranial magnetic stimulation (e.g92.,), electroencephalography (e.g93.,) or functional magnetic resonance imagery (e.g., 9) to investigate these questions.

The experimental design used in this study did not include a baseline for heart rate variability, leading us to analyze the data solely based on the raw response to the task, without normalization or subtraction of a baseline heart rate variability. Consequently, our heart rate variability data should be considered with caution. Additionally, a substantial proportion of heart rate variability data were missing due to technical issues, which resulted in the exclusion of 11 participants from the repeated measures ANOVA. This level of data loss may limit the robustness of our heart rate variability results. We encourage future researchers to replicate our study with an a priori approach to the heart rate variability measure, in order to include a baseline and match the highest standard of measurement and analysis for this parameter94.

The CTT was originally designed to investigate implicit learning39, with the repeated sequence being flanked by two portions of random sequences, unbeknownst to the participants. To capture the perception of effort without the confound of random sequences in the repeated condition, and vice-versa, we modified the task to include either all random sequences or only the repeated sequence. Our modified CTT may have contributed to most participants gaining explicit awareness of the repeated sequence, which may have led to a propensity for explicit learning in our group of participants. We encourage future research to control for implicit versus explicit motor learning to examine the impact on the perception of effort. Finally, as motor learning is not confined to the use of the sequence-learning paradigm, we encourage researchers to conceptually reproduce our results using other motor learning paradigms, such as adaptation or association learning.

Conclusion

The observation of decreased perception of effort during the process of learning a new motor task is of critical importance to further understand the mechanisms of motor learning, and the relationship between effort, its perception, and motor performance. Our findings suggest that motor sequence learning reduces perceived effort. Thus, as sequence-specific task proficiency increased, our participants found the task less effortful. As (i) effort could be defined as the voluntary engagement of cognitive and physical resources to perform, or attempt to perform, a task16,17,18,21, and (ii) motor learning is proposed to induce a minimization or optimization of physical and cognitive resources6,15, our results empirically support the theoretical relationship between motor learning, effort, and its perception. Our findings present valuable opportunities for future research to investigate the behavioral and neural mechanisms underlying motor learning and effort perception. As effort could be altered in various clinical populations (e.g., stroke95 or during the ageing process96, our results may have important implications for future research in aging and clinical populations.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, and approval of the ethics committee. Individual data are presented in the figures.

References

Schmidt, R. A., Lee, T. D., Winstein, C., Wulf, G. & Zelaznik, H. N. Motor control and learning: A behavioral emphasisHuman kinetics,. (2018).

Guthrie, E. R. Psychology of Learning. (1935).

Magill, R. & Anderson, D. I. Motor Learning and Control (McGraw-Hill Publishing, 2010).

Fitts, P. & Posner, M. Human performance. Brooks/Cole (1967).

Krakauer, J. W., Hadjiosif, A. M., Xu, J., Wong, A. L. & Haith, A. M. Motor learning. Compr. Physiol. 9, 613–663. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.c170043 (2019).

Passingham, R. E. Attention to action. Biol. Sci. 351, 1473–1479 (1996).

Sakai, K. et al. Transition of brain activation from frontal to parietal areas in visuomotor sequence learning. J. Neurosci. 18, 1827–1840 (1998).

Lohse, K. R., Wadden, K., Boyd, L. A. & Hodges, N. J. Motor skill acquisition across short and long time scales: a meta-analysis of neuroimaging data. Neuropsychologia 59, 130–141 (2014).

Gobel, E. W., Parrish, T. B. & Reber, P. J. Neural correlates of skill acquisition: decreased cortical activity during a serial interception sequence learning task. Neuroimage 58, 1150–1157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.06.090 (2011).

Toni, I., Krams, M., Turner, R. & Passingham, R. E. The time course of changes during motor sequence learning: a whole-brain fMRI study. Neuroimage 8, 50–61 (1998).

Doyon, J. et al. Experience-dependent changes in cerebellar contributions to motor sequence learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 1017–1022 (2002).

Debaere, F., Wenderoth, N., Sunaert, S., Van Hecke, P. & Swinnen, S. Changes in brain activation during the acquisition of a new bimanual coordination task. Neuropsychologia 42, 855–867 (2004).

Patel, R., Spreng, R. N. & Turner, G. R. Functional brain changes following cognitive and motor skills training: a quantitative meta-analysis. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 27, 187–199 (2013).

Paus, T., Koski, L., Caramanos, Z. & Westbury, C. Regional differences in the effects of task difficulty and motor output on blood flow response in the human anterior cingulate cortex: a review of 107 PET activation studies. Neuroreport 9, R37–R47 (1998).

Carson, R. G. & Riek, S. Changes in muscle recruitment patterns during skill acquisition. Exp. Brain Res. 138, 71–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002210100676 (2001).

Preston, J. & Wegner, D. M. Elbow grease: when action feels like work. In E. Morsella, J. A. Bargh, & P. M. Gollwitzer (Eds.). Oxford Handb. Hum. Action, 569–586 (2009).

Inzlicht, M., Shenhav, A. & Olivola, C. Y. The effort paradox: effort is both costly and valued. Trends Cogn. Sci. 22, 337–349 (2018).

Steele, J. What is (perceived) effort? Objective and subjective effort during task performance. PsyArχiv https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/kbyhm (2020).

Halperin, I. & Vigotsky, A. D. An integrated perspective of effort and perception of effort. Sports Med. 54, 2019–2032 (2024).

Mangin, T. & Pageaux, B. Effort and its perception revisited: How physical-domain insights could lead toward a unified theory. PsyArXiv. April 29. (2025). https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/64kpq_v1

Richter, M., Gendolla, G. & Wright, R. Three decades of research on motivational intensity theory: what we have learned about effort and what we still don’t know. Adv. Motiv Sci. 3, 149–186 (2016).

de la Garanderie, M. P. et al. Perception of effort and the allocation of physical resources: A generalization to upper-limb motor tasks. Front. Psychol. 13, 974172 (2023).

Pageaux, B. Perception of effort in exercise science: definition, measurement and perspectives. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 16, 885–894 (2016).

Marcora, S. M. & Staiano, W. The limit to exercise tolerance in humans: Mind over muscle? Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 109, 763–770. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-010-1418-6 (2010).

Bergevin, M. et al. Pharmacological Blockade of muscle afferents and perception of effort: A systematic review with Meta-analysis. Sports Med. 53, 415–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-022-01762-4 (2023).

de Morree, H. M., Klein, C. & Marcora, S. M. Perception of effort reflects central motor command during movement execution. Psychophysiology 49, 1242–1253. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.2012.01399.x (2012).

Subramanian, D., Alers, A. & Sommer, M. A. Corollary discharge for action and cognition. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging. 4, 782–790 (2019).

Crapse, T. B. & Sommer, M. A. Corollary discharge across the animal Kingdom. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 587–600 (2008).

McCloskey, D. Centrally-generated commands and cardiovascular control in man. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 3, 369–378 (1981).

Croxson, P. L., Walton, M. E., O’Reilly, J. X., Behrens, T. E. & Rushworth, M. F. Effort-based cost-benefit valuation and the human brain. J. Neurosci. 29, 4531–4541. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4515-08.2009 (2009).

Engstrom, M., Landtblom, A. M. & Karlsson, T. Brain and effort: brain activation and effort-related working memory in healthy participants and patients with working memory deficits. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 7, 140. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00140 (2013).

Klein-Flugge, M. C., Kennerley, S. W., Friston, K. & Bestmann, S. Neural signatures of value comparison in human cingulate cortex during decisions requiring an Effort-Reward Trade-off. J. Neurosci. 36, 10002–10015. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0292-16.2016 (2016).

Vassena, E. et al. Overlapping neural systems represent cognitive effort and reward anticipation. PLoS One. 9, e91008. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0091008 (2014).

Paus, T. Primate anterior cingulate cortex: where motor control, drive and cognition interface. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2, 417–424 (2001).

Truong, C. et al. Time-of-day effects on skill acquisition and consolidation after physical and mental practices. Sci. Rep. 12, 5933 (2022).

Craig, C. L. et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 35, 1381–1395 (2003).

Oldfield, R. C. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 9, 97–113 (1971).

Kantak, S. S. & Winstein, C. J. Learning-performance distinction and memory processes for motor skills: a focused review and perspective. Behav. Brain Res. 228, 219–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2011.11.028 (2012).

Meehan, S. K., Randhawa, B., Wessel, B. & Boyd, L. A. Implicit sequence-specific motor learning after subcortical stroke is associated with increased prefrontal brain activations: an fMRI study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 32, 290–303. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.21019 (2011).

Wadden, K., Brown, K., Maletsky, R. & Boyd, L. A. Correlations between brain activity and components of motor learning in middle-aged adults: an fMRI study. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 7, 169. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00169 (2013).

Boyd, L. A., Vidoni, E. D. & Siengsukon, C. F. Multidimensional motor sequence learning is impaired in older but not younger or middle-aged adults. Phys. Ther. 88, 351–362 (2008).

Pew, R. W. Levels of analysis in motor control. Brain Res. 71, 393–400 (1974).

Boyd, L. A. & Winstein, C. J. Cerebellar stroke impairs Temporal but not Spatial accuracy during implicit motor learning. Neurorehabilit Neural Repair. 18, 134–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888439004269072 (2004).

Mang, C. S., Snow, N. J., Campbell, K. L., Ross, C. J. & Boyd, L. A. A single bout of high-intensity aerobic exercise facilitates response to paired associative stimulation and promotes sequence-specific implicit motor learning. J. Appl. Physiol. 117, 1325–1336. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00498.2014 (2014).

Vidoni, E. D. & Boyd, L. A. Motor sequence learning occurs despite disrupted visual and proprioceptive feedback. Behav. Brain Funct. 4, 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-9081-4-32 (2008).

Mangin, T., André, N., Benraiss, A., Pageaux, B. & Audiffren, M. No ego-depletion effect without a good control task. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 57 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.102033 (2021).

Dong, L., Pageaux, B., Romeas, T. & Berryman, N. The effects of fatigue on perceptual-cognitive performance among open-skill sport athletes: A scoping review. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984x.2022.2135126 (2022).

Mangin, T. & Pageaux, B. It is time to stop using the terminology passive fatigue. Motiv Sci. 11, 125–132. https://doi.org/10.1037/mot0000375 (2025).

Westgate, E. C. & Wilson, T. D. Boring thoughts and bored minds: the MAC model of boredom and cognitive engagement. Psychol. Rev. 125, 689 (2018).

Wolff, W. & Martarelli, C. S. Bored into depletion? Toward a tentative integration of perceived self-control exertion and boredom as guiding signals for goal-directed behavior. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 15, 1272–1283 (2020).

Matthews, G., Campbell, S. E. & Falconer, S. in Proc. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. Annu. Meet. 906–910 (Sage Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA).

Hart, S. G., & Staveland, L. E. Development of NASA-TLX (Task load Index): Results of empirical and theoretical research. In Advances in psychology-italics. 52, 139-183. (1988).

Gendolla, G. H. E. & Richter, M. Effort mobilization when the self is involved: some lessons from the cardiovascular system. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 14, 212–226. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019742 (2010).

Kozlowski, B. et al. Perception of effort during an isometric contraction is influenced by prior muscle lengthening or shortening. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 121, 2531–2542. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-021-04728-y (2021).

Luft, C. D., Takase, E. & Darby, D. Heart rate variability and cognitive function: effects of physical effort. Biol. Psychol. 82, 164–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2009.07.007 (2009).

Hermens, H. J., Freriks, B., Disselhorst-Klug, C. & Rau, G. Development of recommendations for SEMG sensors and sensor placement procedures. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 10, 361–374 (2000).

Shaffer, F. & Ginsberg, J. P. An overview of heart rate variability metrics and norms. Front. Public. Health. 5, 258. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00258 (2017).

Neva, J., Brown, K., Mang, C., Francisco, B. & Boyd, L. An acute bout of exercise modulates both intracortical and interhemispheric excitability. Eur. J. Neurosci. 45, 1343–1355 (2017).

Siengsukon, C. F. & Boyd, L. A. Sleep to learn after stroke: implicit and explicit off-line motor learning. Neurosci. Lett. 451, 1–5 (2009).

Wadden, K. P. et al. Predicting motor sequence learning in individuals with chronic stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 31, 95–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968316662526 (2017).

Doyon, J. et al. Contributions of the basal ganglia and functionally related brain structures to motor learning. Behav. Brain Res. 199, 61–75 (2009).

Lehéricy, S. et al. Distinct basal ganglia territories are engaged in early and advanced motor sequence learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 102, 12566–12571 (2005).

Pageaux, B., Marcora, S. M. & Lepers, R. Prolonged mental exertion does not alter neuromuscular function of the knee extensors. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 45, 2254–2264. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e31829b504a (2013).

Williamson, J. et al. Hypnotic manipulation of effort sense during dynamic exercise: cardiovascular responses and brain activation. J. Appl. Physiol. 90, 1392–1399 (2001).

Braver, T. S. et al. A parametric study of prefrontal cortex involvement in human working memory. Neuroimage 5, 49–62 (1997).

Miller, E. K. & Cohen, J. D. An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 24, 167–202 (2001).

Domenech, P., Redoute, J., Koechlin, E. & Dreher, J. C. The Neuro-Computational architecture of Value-Based selection in the human brain. Cereb. Cortex. 28, 585–601. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhw396 (2018).

Shenhav, A. et al. Toward a rational and mechanistic account of mental effort. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 40, 99–124. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-neuro-072116-031526 (2017).

Lashley, K. S. The Problem of Serial order in BehaviorVol. 21 (Bobbs-Merrill Oxford, 1951).

Sakai, K., Kitaguchi, K. & Hikosaka, O. Chunking during human visuomotor sequence learning. Exp. Brain Res. 152, 229–242 (2003).

Verwey, W. B. & Eikelboom, T. Evidence for lasting sequence segmentation in the discrete sequence-production task. J. Mot Behav. 35, 171–181 (2003).

Doyon, J. & Benali, H. Reorganization and plasticity in the adult brain during learning of motor skills. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 15, 161–167 (2005).

Wymbs, N. F., Bassett, D. S., Mucha, P. J., Porter, M. A. & Grafton, S. T. Differential recruitment of the sensorimotor putamen and frontoparietal cortex during motor chunking in humans. Neuron 74, 936–946 (2012).

Abrahamse, E. L., Ruitenberg, M. F., De Kleine, E. & Verwey, W. B. Control of automated behavior: insights from the discrete sequence production task. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 7, 82 (2013).

Keele, S. W. Movement control in skilled motor performance. Psychol. Bull. 70, 387 (1968).

Logan, J. A., Schatschneider, C. & Wagner, R. K. Rapid serial naming and reading ability: the role of lexical access. Read. Writ. 24, 1–25 (2011).

Diedrichsen, J. & Kornysheva, K. Motor skill learning between selection and execution. Trends Cogn. Sci. 19, 227–233 (2015).

Verwey, W. B., Shea, C. H. & Wright, D. L. A cognitive framework for explaining serial processing and sequence execution strategies. Psychon Bull. Rev. 22, 54–77 (2015).

Ariani, G. & Diedrichsen, J. Sequence learning is driven by improvements in motor planning. J. Neurophysiol. 121, 2088–2100 (2019).

Kahn, M. J., Tan, K. C. & Beaton, R. J. in Proc. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. Annu. Meet. 1509–1513 (SAGE Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA).

Farooqui, A. A., Gezici, T. & Manly, T. Chunking of control: an unrecognized aspect of cognitive resource limits. J Cogn 6(1),25 (2023).https://doi.org/10.5334/joc.275.

Moisello, C. et al. Motor sequence learning: acquisition of explicit knowledge is concomitant to changes in motor strategy of finger opposition movements. Brain Res. Bull. 85, 104–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresbull.2011.03.023 (2011).

Wong, A. L., Lindquist, M. A., Haith, A. M. & Krakauer, J. W. Explicit knowledge enhances motor Vigor and performance: motivation versus practice in sequence tasks. J. Neurophysiol. 114, 219–232. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00218.2015 (2015).

Ghilardi, M. F. et al. Patterns of regional brain activation associated with different forms of motor learning. Brain Res. 871, 127–145 (2000).

Solopchuk, O., Alamia, A., Olivier, E. & Zénon, A. Chunking improves symbolic sequence processing and relies on working memory gating mechanisms. Learn. Mem. 23, 108–112 (2016).

Carrier, D. R., Anders, C. & Schilling, N. The musculoskeletal system of humans is not tuned to maximize the economy of locomotion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 18631–18636 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1105277108

Thoroughman, K. A. & Shadmehr, R. Electromyographic correlates of learning an internal model of reaching movements. J. Neurosci. 19, 8573–8588 (1999).

Lampropoulou, S. I. & Nowicky, A. V. The effect of transcranial direct current stimulation on perception of effort in an isolated isometric elbow flexion task. Mot Control. 17, 412–426 (2013).

Appelhans, B. M. & Luecken, L. J. Heart rate variability and pain: associations of two interrelated homeostatic processes. Biol. Psychol. 77, 174–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.10.004 (2008).

Luque-Casado, A., Perales, J. C., Cárdenas, D. & Sanabria, D. Heart rate variability and cognitive processing: the autonomic response to task demands. Biol. Psychol. 113, 83–90 (2016).

Schmitt, L., Regnard, J. & Millet, G. P. Monitoring fatigue status with HRV measures in elite athletes: an avenue beyond RMSSD? Front. Physiol. 6, 343. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2015.00343 (2015).

Ljubisavljevic, M. Transcranial magnetic stimulation and the motor learning-associated cortical plasticity. Exp. Brain Res. 173, 215–222 (2006).

de Vico Fallani, F. et al. Structural organization of functional networks from EEG signals during motor learning tasks. Int. J. Bifurcat. Chaos. 20, 905–912 (2010).

Laborde, S., Mosley, E. & Thayer, J. F. Heart rate variability and cardiac vagal tone in Psychophysiological research–recommendations for experiment planning, data analysis, and data reporting. Front. Psychol. 8, 213 (2017).

Kuppuswamy, A., Clark, E. V., Turner, I. F., Rothwell, J. C. & Ward, N. S. Post-stroke fatigue: a deficit in corticomotor excitability? Brain 138, 136–148 (2015).

Aschenbrenner, A. J. et al. Increased cognitive effort costs in healthy aging and preclinical alzheimer’s disease. Psychol. Aging. 38, 428 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Maxime Bergevin for providing valuable feedback on the manuscript. This work is supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC; RGPIN-2019-05057 to BP and RGPIN-2020–05263 to JLN). BGG is supported by scholarships from the Centre de recherche de l’Institut universitaire de gériatrie de Montréal (CRIUGM), the Centre interdisciplinaire de recherche sur le cerveau et l’apprentissage (CIRCA), and the Faculté de médecine at Université de Montréal. BP and JLN are supported by the Chercheur Boursier Junior 1 award from the Fonds de Recherche du Québec - Santé. TM is supported by the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Nature et Technologies with a Postdoctoral scholarship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BP and JLN co-conceived the study. BGG, BP and JLN designed the experiment; BGG collected the data; BGG analyzed the data; BGG and TM performed the statistical analyses; BGG created the first draft of the figures and all authors contributed to their final version; BGG wrote the first draft of the manuscript; BP, JLN, and TM provided feedback on the manuscript; all authors read and edited the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghafari Goushe, B., Mangin, T., Pageaux, B. et al. Perception of effort decreases with motor sequence learning. Sci Rep 15, 44403 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20733-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20733-z