Abstract

DNA copy number research is impeded by limited methodology to determine true DNA copy numbers accurately and precisely. Human alpha defensin 1–3 (DEFA1A3) is a multiallelic gene with DNA copy numbers generally ranging from 2 to 12 copies per diploid genome. In this study, we developed a digital droplet PCR (ddPCR) protocol using DEFA1A3 as a model locus. We compared these results to DNA copy numbers determined by pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), which is considered a gold standard in CNV identification, on 40 DNA samples from a clinical study cohort. Taqman real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) was also compared, being the other major available low cost, high-throughput system. The copy number measurements of 40 genomic samples were highly concordant between ddPCR and PFGE, while copy number by qPCR correlated only weakly with PFGE copy number. In conclusion, ddPCR is a low-cost, high-throughput technique with accurate resolution of CNV at both low and high DNA copy numbers. This makes it an ideal model to adapt for CNV testing in clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Copy number variations (CNVs) refer to variations in the number of copies present of specific DNA sequences between individual genomes in a population. CNVs range in length from 50 base pairs to multiple mega base pairs and can result from gene mutations as well as errors in DNA replication or recombination1,2,3,4. Copy number variable regions comprise at least 12% of the human genome and thus contribute significantly to human genetic diversity5. CNVs have a wide spectrum of clinical effect: Some CNVs may cause no discernible changes in phenotype or disease susceptibility, while others cause severe disease pathologies by altering gene dosage. For example, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease is a debilitating hereditary neuropathy caused by inherited CNV mutation4,5,6. Our lab has previously identified the clinical significance of CNVs in the human alpha defensin 1–3 (DEFA1A3) locus in relation to urinary tract infection (UTI) susceptibility in children with vesicoureteral reflux (VUR). DEFA1A3 copy number varies from 2 to 16 copies per diploid genome with high variability between individuals, and lower gene copy number is associated with an increased incidence of UTI in children with VUR on antibiotic prophylaxis in the Randomized Intervention for Children with Vesicoureteral Reflux (RIVUR) trial7. Higher copy number of this gene was then confirmed, using a transgenic knock-in DEFA1A3 mouse model, to be protective against UTI in a dose-dependent manner8,9.

Despite the demonstrated significance of copy number variation in disease, CNV testing is not universally utilized in the clinical arena. A major obstacle to the standardization and implementation of a single CNV enumeration method among clinical laboratories is that each currently used methodology is limited by either low-throughput nature, cost, labor requirement, technical difficulty, test resolution, or limited discrimination power above a certain CNV threshold7,10,11,12,13,14,15.

Digital droplet PCR (ddPCR) is a high-throughput, low-cost, and minimally labor-intensive technique. ddPCR partitions the PCR system into over 20,000 water-in-oil microdroplets, conferring thousands of data points and increasing the accuracy of results. Thus, ddPCR provides an absolute quantification of copy number that is unaffected by unequal amplification efficiencies. This method allows for detection of small changes in copy number over a wide range of CNV lengths16. Through these advantages, ddPCR overcomes the limitations inherent to other available testing methodologies in identification of CNVs. Here, we validate ddPCR as alternative methodology for CNV enumeration. We compare ddPCR to pulsed field gel electrophoresis-Southern blot (PFGE) and quantitative PCR. PFGE is highly accurate as it infers the absolute copy number present versus an estimation based on ratios, but it is low-throughput and highly labor-intensive15,17. PFGE requires special equipment, high-quality DNA, and depends on the unique restriction enzyme sites used in the experiment. Given its reliance on the specific expertise of the person conducting the test, PFGE-determined CNV enumeration can also be affected by operator-dependent bias. While these factors limit the generalizability of this method to standard clinical practice, PFGE is generally accepted to be a gold standard for both precision and accuracy in CNV enumeration and it has been used to validate other CNV-testing methods18. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) is, in contrast, high-throughput and cost-efficient. It requires only tiny amounts of DNA in a PCR reaction and includes both the target and a stable 2 copy gene as a reference. Subsequent copy number is assigned based on the fold ratio between the target and reference genes. A critical flaw of the qPCR method is that the copy-fold relationship decreases with increasing copy number, making results difficult to interpret and increasing diagnostic error at higher copy numbers. Specifically, if one assumes even a very small error rate from PCR inefficiency, pipetting variations, etc., this error can compound dramatically and lead to low precision and reproducibility of qPCR in high copy number states. We chose to compare ddPCR to the PFGE and qPCR methodologies as PFGE represents highly accurate/reproducible methodology and qPCR represents low-cost, high-throughput methodology.

To carry out this comparison, we utilized a sample of forty patients from the RIVUR cohort, on which we had previously tested for DEFA1A3 CNV using PFGE. The DEFA1A3 gene’s high copy number variability, as already demonstrated in this sample cohort, makes it a practical target for cross-platform validation of CNV enumeration techniques. Specifically, it is ideal for comparing the accuracy of PCR-based methods at the extremes of copy number, especially above 8 copies per diploid genome, where traditional qPCR may be expected to err in CNV enumeration and precision.

Other CNV enumeration methods exist that we chose to omit from this study. Hybridization-based methodologies visualize multiple stretched target DNA sequences using fluorochrome-labeled DNA probes. Fiber-fluorescence in situ hybridization (Fiber-FISH) is one such methodology, though it is technically challenging and resolution is low relative to other CNV enumeration methodologies. This process is also low-throughput, labor-intensive, and technically challenging, making it a poor candidate for standardization in the clinical space15,19. Array-based comparative Genomic Hybridization (CGH) is another of these methods, and like qPCR it functions by comparing ratios of test to reference DNA. The method only provides a relative quantitative difference compared to a pooled or reference DNA sample with no true quantification.

Paralogue ratio testing (PRT) was developed to overcome some of the limitations of qPCR and uses a single pair of primers to amplify target and reference sequences that are nearly identical but varied in length. The ratio of test to reference loci is used to estimate the gene copy number. Though it is robust and high-throughput, PRT depends on the assumptions that primer binding, and thus amplification efficiency, will not be affected by polymorphisms in the tested DNA, and that the paralogous reference loci do not themselves vary in copy number. The success of PRT is dependent on the choice of primers and the identification of a suitable paralogous reference sequence outside of the target region, betraying a difficult test design. PRT is additionally sensitive to the quality of DNA and potentially limited by system bias. A significant amount of technical expertise is required to design and optimize primers for PRT10.

Next generation genome sequencing (NGS) determines CNVs through base-by-base reading with the aid of analytics. NGS provides base-level resolution of CNVs but can be limited by read depth as well as bias in the choice of reference genome. It is additionally low-throughput and high in cost, making it unfit to serve as a clinical standard for CNV enumeration in its current state.

Results

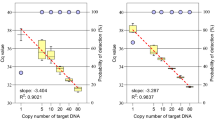

PFGE-determined results are considered highly precise and accurate and are thus used as a reference to evaluate ddPCR and qPCR-determined copy number typing of the DEFA1A3 gene. DNA copy number typing by these methods for each individual sample is shown in Table 1. ddPCR and qPCR-determined copy numbers within ≤ 1 of the PFGE-determined copy number were considered concordant results. Conversely, copy numbers ≥ 2 different from PFGE values were considered discordant. ddPCR showed high overall concordance of 95% (38/40) with PFGE, consistent with strong Spearman correlation of r = 0.90 (p < 0.0001) between these methods. Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test also supported concordance, with median of differences of 0 (IQR [0,0]), and ddPCR copy numbers differed 5% on average from PFGE. By comparison, qPCR results were 60% (24/40) concordant with PFGE with moderate Spearman correlation of r = 0.57 (p < 0.0001). The median of differences between PFGE and qPCR was − 1.0, (IQR [-2,1]) by Wilcoxon test, and qPCR results differed by an average of 22% from PFGE.

The copy number measurements of the 40 investigated samples were then plotted for ddPCR versus PFGE (Fig. 1A) and qPCR versus PFGE (Fig. 1B). Simple linear regression was applied, constrained to pass through (0,0), where Y = X with a slope of 1 would demonstrate 1:1 agreement between the tested method and PFGE. The regression equation for ddPCR versus PFGE resulted as Y = 0.9953 × (95% CI [0.9607,1.030]); That of qPCR was Y = 0.8889 × (95% CI [0.8114,0.9664]), demonstrating average underestimation of copy number by qPCR. Comparisons of qPCR to ddPCR were similar to comparisons of qPCR with PFGE, given the high concordance of ddPCR results with PFGE in our samples.

Determination of ddPCR (A) and qPCR (B) accuracy in CNV enumeration, though comparison to PFGE. The line of best fit from simple linear regression, constrained through (0,0) is presented with 95% confidence bands and the resulting equation is displayed on the graph in the form of y = mx, where m is slope. An m = 1 would signify perfect concordance, while values below 1 represent that the modality is on average underestimating the copy number when compared to PFGE.

Discussion

The major challenge in assessing copy number variation in the clinical space is difficulty standardizing a high-throughput methodology. As we have described, PFGE is considered one of the gold standards in copy number determination. As it measures, rather than estimates, copy number by the physical size of a DNA fragments, it is more accurate than estimation methods20,21. However, though PFGE is sensitive, precise, and highly repeatable, there are limitations for the PFGE platform including the need for special equipment and time-intensive procedures that take several days to complete. DNA is separated by electrophoresis and interpreted by size rather than sequence, which is not conducive to defining the precise gene structure. Because this method separates large DNA fragments, 10–50 Mb in size, this method is difficult to apply to lower-quality DNA samples, for example from archives22.

In this study, we validated ddPCR as a low-cost, high-throughput alternative method for CNV enumeration of the DEFA1A3 gene by comparing it to PFGE. In our data, we had strong concordance between ddPCR and PFGE copy numbers, with copy numbers differing only 5% on average between these methods. This comparison demonstrates that ddPCR was highly accurate in copy number assessment of DEFA1A3 in our study.

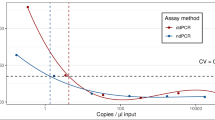

We also demonstrated the superiority of ddPCR over qPCR-based copy typing. In our study, qPCR suffered an additional average error of 17% beyond ddPCR when comparing to PFGE. The superiority of ddPCR over qPCR in copy number enumeration echoes the literature, and most studies cite that high variability between qPCR reactions is a major source of error for this method23,24,25,26. As the qPCR method is heavily affected by the PCR efficiency of both target and reference, small inefficiencies or inherent errors are compounded exponentially through 35–40 cycles and even a minor change in amplification efficiency could result in an significant error in ΔΔCt calculation27. An additional weakness of qPCR is that copy number estimation is derived from the fold change, which decreases non-linearly with increasing copy number. Thus, the discrimination power of qPCR copy number typing is increasingly prone to error as copy number increases and a limit of discrimination can often be demarcated28. We identified the qPCR discrimination limit for DEFA1A3 to be around 7–8 copies of the gene (Fig. 2).

In our data, two-thirds of the discordant values in the qPCR data were at 7 or more copies by PFGE, which is consistent with the identified limit of discrimination. Other studies have found better agreement between qPCR and ddPCR but with higher ambiguity and misclassification at higher copy numbers29,30. The discrepancy in agreement level between qPCR and PFGE in our study may be explained by the range of copy numbers being tested. Studies reporting good agreement of qPCR with ddPCR were generally testing copy numbers ≤ 4, which is lower than the range we tested for DEFA1A3. Thus, in this context, qPCR may not surpass the discrimination limit, demonstrating higher accuracy in low copy number settings.

The high level of concordance we observed between ddPCR and PFGE is in agreement with published literature comparing ddPCR to other established copy number identification methods23,31. A single study reported higher average difference between ddPCR and PFGE with persistent underestimation of copy number by ddPCR18. However, it is important to note that this study tested ddPCR in only seven samples. Though significant underestimation was reported in this sample, ddPCR and PFGE copy numbers did still show strong linear correlation with each other. The difference observed in that dataset may be due to inherent error rates when testing large versus small variable regions, as well as high absolute copy number. While ddPCR is highly replicable and accurate under ideal conditions, results can also be impacted by under-dilution of samples. Variable GC richness within different genes and the impact of annealing temperature may also necessitate developing gene-specific experimental conditions for ddPCR-based copy number identification25.

Despite these limitations, we have shown that ddPCR can be utilized to produce reliable and accurate copy numbers for the DEFA1A3 gene, and it is superior to qPCR in copy number determination. While ddPCR and qPCR are both high-throughput methodologies that have the potential to be standardized and used in clinical practice, ddPCR is not impacted by a discrimination limit like qPCR and may perform significantly better than qPCR at higher copy numbers. The digital nature of ddPCR makes the copy number quantitation absolute and minimizes the impact of variable PCR efficiency between target and reference genes. As ddPCR results depend solely on the fluorescent-positive (1) or negative (0) signal counts between target and reference droplets, less ambiguity exists in interpretation than with other methods.

Future studies should assess how ddPCR functions against the critical weaknesses of other copy typing methods, including quantification of the impact of inter-observer variability and level of technical expertise on the accuracy and precision of results. Now that we have validated the protocol for copy number identification by ddPCR in DEFA1A3 in a reference cohort of clinical samples, this protocol should ideally be recapitulated in larger sample cohorts for further validation. As clinical development may pivot ddPCR toward a multiplexing approach over single-gene CNV identification, it should be confirmed that the reliability of this method does not change when the experiment is scaled to simultaneously test multiple genes. Based on our results and with additional future studies, we believe that ddPCR may be optimized to fill the clinical need for a robust, low-cost, and high-throughput genomic copy typing methodology.

Materials and methods

Subjects

DNA was utilized from a previously genetically characterized cohort from the Randomized intervention for Vesicoureteral Reflux (RIVUR) trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT00405704). The trial recruited 607 children (558 girls and 49 boys) with UTI and VUR, and DNA was obtained following informed consent32. For this experiment, a subset of 40 previously tested Caucasian female patients with known DEFA1A3 copy numbers ranging from 4 to 13 were specifically selected for copy number typing comparison32,33. The patient mean age was 23 months old (range = 2–71 months). Human subject/sample research was approved by the Indiana University Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocols 1,709,327,425 and 1,802,253,259. All methods were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. For complete RIVUR study design and outcome data, please refer to previously published manuscripts32.

DEFA1A3 copy typing

Digital droplet digital PCR (ddPCR)

The DNAs were quantified with a Qubit 3 Spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The ddPCR was done as described previously34. The samples were analyzed using a dual fluorescent probe-based multiplex assay.

The DEFA1A3 was amplified with the following primers and probe:

Forward: 5’-CCTCTCACTGAGATTG-3’,

Reverse: 5’-CCAGCCTGGATTTATAG-3’,

Probe: 5’-(FAM) CTTGTCTCCGAGCCTT-MGB-BHQ-3’.

RPP30-HEX (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) was used as a reference gene, as it is known to be 2 copies in all individuals per diploid genome. The DNA was predigested with HaeIII before PCR (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) to obtain single copy fragments of DEFA1A3. The DNAs were serially diluted and amplified to determine the optimized copy number for the ddPCR amplification by the following protocol: 95 °C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15s, and 60 °C for 1 min (2.5 °C/s ramp rate) with a final 10 min hold at 98 °C. (Fig. 3)35. In each assay, DNA samples were amplified in triplicate. Four reference DNA samples with known copy number and two distilled water controls were included in each test.

Optimization of DNA loading in the copy typing using ddPCR. ddPCR droplets could not discriminate whether signals were from droplets containing single or multiple copies of DNA. A titration using serially diluted DNA loading should be conducted to ensure each droplet contains no more than one copy of the target/reference fragments.

The copy numbers were assayed with a QX200 digital PCR system coupled with a QX200 Droplet Generator and a QX200 droplet reader using company-specified reagents and analyzed with Quantasoft software. (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA)36. The copy number was calculated by (CopyTarget/CopyRPP30)*2, which represents the copy number per cell.

All ddPCR and qPCR testing was run in triplicate and results averaged. The experimental criterion for an accepted result included 0 signal for negative controls, and identical copy number or within ± 1 copy difference for the 4 known copy number samples. Otherwise, the test was rejected and repeated. The PFGE copy number of the test cohort was blinded until analysis, at which time all cases with calculated copy numbers ≥ 2 copies away from the PFGE copy number underwent additional duplicate runs. Copy numbers were rounded up or down to the closest integer.

TaqMan real-time PCR

Quantitative real–time PCR (qPCR) was performed using the Taqman method with the above-mentioned primer pair and probe with RPP30 as a reference, using Bio-Rad CFX real-time PCR system (Bio-Rad). The PCR conditions were initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles, each with denaturation at 95 °C for 10 s, annealing at 60 °C for 60 s. The copy number were calculated by ΔΔCt method7. Pooled ΔCt of 6 known copy samples was used for calibration.

Copy numbers were rounded up or down to the closest integer.

Interpretation of the experimental data

The copy numbers from each subject in the cohort were compared across 3 different technical platforms. The copy numbers were considered concordant if reads were identical or within the variation range of ≤ 1 copy to the established PFGE copy number. Any copy number measurement with a variation range ≥ 2 copy from the PFGE-determined number was determined to be discordant.

Pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE)

PFGE results, which were previously reported by Schwaderer et al.,7 were used as the gold standard for copy typing. Briefly, the DNA was PCR amplified, digested with PacI enzyme, separated with PFGE for DNA fragments with sizes between 50 and 400 kb. The DNA fragments were then subjected to a modified Southern blot procedure7. The absolute copy number was determined by the size of band on the λ-ladder base using the 19.1 kb haplotype size of DEFA1A3 gene as reference.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad software (GraphPad, Boston, MA). PFGE and ddPCR copy numbers were not normally distributed (Anderson-Darling), so nonparametric testing was used where applicable. ddPCR and qPCR were compared to PFGE using simple linear regression, constrained through (0,0), and displayed with 95% confidence bands of the best-fit line. Difference in medians was derived from Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank tests with two-tailed p and correlation analyses were performed using Spearman’s test with two-tailed p.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Feuk, L., Carson, A. R. & Scherer, S. W. Structural variation in the human genome. Nat. Rev. Genet. 7, 85–97. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg1767 (2006).

Girirajan, S., Campbell, C. D. & Eichler, E. E. Human copy number variation and complex genetic disease. Annu. Rev. Genet. 45, 203–226. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-genet-102209-163544 (2011).

Arlt, M. F., Wilson, T. E. & Glover, T. W. Replication stress and mechanisms of CNV formation. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 22, 204–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gde.2012.01.009 (2012).

Pos, O. et al. DNA copy number variation: main characteristics, evolutionary significance, and pathological aspects. Biomed. J. 44, 548–559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bj.2021.02.003 (2021).

Redon, R. et al. Global variation in copy number in the human genome. Nature 444, 444–454. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05329 (2006).

Rice, A. M. & McLysaght, A. Dosage sensitivity is a major determinant of human copy number variant pathogenicity. Nat. Commun. 8, 14366. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14366 (2017).

Schwaderer, A. L. et al. Polymorphisms in alpha-Defensin-Encoding DEFA1A3 associate with urinary tract infection risk in children with vesicoureteral reflux. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 27, 3175–3186. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2015060700 (2016).

Canas, J. J. et al. DEFA1A3 DNA gene-dosage regulates the kidney innate immune response during upper urinary tract infection. Life Sci. Alliance. 7 https://doi.org/10.26508/lsa.202302462 (2024).

Canas, J. J. et al. Human neutrophil peptides 1–3 protect the murine urinary tract from uropathogenic Escherichia coli challenge. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 119, e2206515119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2206515119 (2022).

Hollox, E. J. Analysis of copy number variation using the paralogue ratio test (PRT). Methods Mol. Biol. 1492, 127–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-6442-0_8 (2017).

Mazaika, E. & Homsy, J. Digital droplet PCR: CNV analysis and other applications. Curr. Protoc. Hum. Genet. 82, 72421–272413. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471142905.hg0724s82 (2014).

Hughes, T. et al. Runaway multi-allelic copy number variation at the alpha-defensin locus in African and Asian populations. Sci. Rep. 10, 9101. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65675-w (2020).

Hollox, E. J. The challenges of studying complex and dynamic regions of the human genome. Methods Mol. Biol. 838, 187–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-61779-507-7_9 (2012).

Khan, F. F. et al. Accurate measurement of gene copy number for human alpha-defensin DEFA1A3. BMC Genom. 14, 719. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-14-719 (2013).

Cantsilieris, S., Baird, P. N. & White, S. J. Molecular methods for genotyping complex copy number polymorphisms. Genomics 101, 86–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygeno.2012.10.004 (2013).

Harmala, S. K., Butcher, R. & Roberts, C. H. Copy number variation analysis by droplet digital PCR. Methods Mol. Biol. 1654, 135–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-7231-9_9 (2017).

Lemmers, R. J. Analyzing copy number variation using Pulsed-Field gel electrophoresis: providing a genetic diagnosis for FSHD1. Methods Mol. Biol. 1492, 107–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-6442-0_7 (2017).

Morton, E. et al. (ed, A.) Challenges and approaches to genotyping repetitive DNA. G3 (Bethesda) 10 417–430 https://doi.org/10.1534/g3.119.400771 (2020).

Shwan, N. A. A., Louzada, S., Yang, F. & Armour, J. A. L. Recurrent rearrangements of human amylase genes create multiple independent CNV series. Hum. Mutat. 38, 532–539. https://doi.org/10.1002/humu.23182 (2017).

Sharma-Kuinkel, B. K., Rude, T. H. & Fowler, V. G. Jr. Pulse field gel electrophoresis. Methods Mol. Biol. 1373, 117–130. https://doi.org/10.1007/7651_2014_191 (2016).

Neoh, H. M., Tan, X. E., Sapri, H. F. & Tan, T. L. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE): A review of the gold standard for bacteria typing and current alternatives. Infect. Genet. Evol. 74, 103935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2019.103935 (2019).

Herschleb, J., Ananiev, G. & Schwartz, D. C. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Nat. Protoc. 2, 677–684. https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2007.94 (2007).

Wen, T., Zhang, X., Lippuner, C., Schiff, M. & Stuber, F. Development and evaluation of a droplet digital PCR assay for 8p23 beta-Defensin cluster copy number determination. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 25, 607–615. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40291-021-00546-2 (2021).

Bharuthram, A., Paximadis, M., Picton, A. C. & Tiemessen, C. T. Comparison of a quantitative Real-Time PCR assay and droplet digital PCR for copy number analysis of the CCL4L genes. Infect. Genet. Evol. 25, 28–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2014.03.028 (2014).

Barbieri, G. et al. Digital droplet PCR versus quantitative PCR for lipoprotein (a) kringle IV type 2 repeat polymorphism genetic characterization. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 38, e24998. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcla.24998 (2024).

Cantsilieris, S., Western, P. S., Baird, P. N. & White, S. J. Technical considerations for genotyping multi-allelic copy number variation (CNV), in regions of segmental duplication. BMC Genom. 15, 329. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-15-329 (2014).

Guescini, M., Sisti, D., Rocchi, M. B., Stocchi, L. & Stocchi, V. A new real-time PCR method to overcome significant quantitative inaccuracy due to slight amplification Inhibition. BMC Bioinform. 9, 326. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-9-326 (2008).

Wu, Y. L. et al. Sensitive and specific real-time polymerase chain reaction assays to accurately determine copy number variations (CNVs) of human complement C4A, C4B, C4-long, C4-short, and RCCX modules: Elucidation of C4 CNVs in 50 consanguineous subjects with defined HLA genotypes. J. Immunol. 179, 3012–3025. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.3012 (2007).

Klove-Mogensen, K., Terp, S. K. & Steffensen, R. Comparison of real-time quantitative PCR and two digital PCR platforms to detect copy number variation in FCGR3B. J. Immunol. Methods. 526, 113628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jim.2024.113628 (2024).

Doleschall, M. et al. Quantitative PCR from human genomic DNA: the determination of gene copy numbers for congenital adrenal hyperplasia and RCCX copy number variation. PLoS One. 17, e0277299. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0277299 (2022).

Oscorbin, I., Kechin, A., Boyarskikh, U. & Filipenko, M. Multiplex DdPCR assay for screening copy number variations in BRCA1 gene. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 178, 545–555. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-019-05425-3 (2019).

Carpenter, M. A. et al. The RIVUR trial: profile and baseline clinical associations of children with vesicoureteral reflux. Pediatrics 132, e34–45. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-2301 (2013).

Investigators, R. T. et al. Antimicrobial prophylaxis for children with vesicoureteral reflux. N Engl. J. Med. 370, 2367–2376. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1401811 (2014).

Syed, F. et al. Beta cell MicroRNAs function as molecular hubs of type 1 diabetes pathogenesis and as biomarkers of diabetes risk. BioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.15.545170 (2023).

Ginzinger, D. G. Gene quantification using real-time quantitative PCR: an emerging technology hits the mainstream. Exp. Hematol. 30, 503–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0301-472x(02)00806-8 (2002).

Pinheiro, L. B. et al. Evaluation of a droplet digital polymerase chain reaction format for DNA copy number quantification. Anal. Chem. 84, 1003–1011. https://doi.org/10.1021/ac202578x (2012).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SZ, ALS, DSH conceptualized and designed the study. SZ, FS, JC, VS generated data. SZ, ALS, EAR, DSH analyzed data. SZ wrote initial draft. SZ, EAR, DSH created response to reviews and wrote revised draft. All authors edited and finalized draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, S., Rajadhyaksha, E.A., Syed, F. et al. Digital droplet PCR is an accurate and precise method to measure DNA copy number. Sci Rep 15, 36958 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20944-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20944-4