Abstract

Fatigue affects over half of all adults worldwide, but it is particularly prevalent among undergraduates due to the combined effects of academic stress and a heavy workload. This study aimed to evaluate the level of fatigue and associated factors among university students in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. An online survey was conducted among 201 nursing students at the College of Nursing between March and May 2024. A Structured questionnaire with 20 questions, divided into three sections (demographics, health-related characteristics, and fatigue assessment), was used for data collection. The Fatigue Assessment Scale (FAS) was used to assess fatigue, with respondents rating their experiences on a 5-point scale. The Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was used to determine the association between variables. To identify predictors of fatigue, the Mann-Whitney U test and the Kruskal-Wallis test were used. Furthermore, logistic regression was applied to identify the predictors of fatigue. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all analyses. In this study of 201 students, 87.1% (175/201) were males, with a mean age of 22.86 ± 1.63 years. A significant proportion, 88.6% (178/201), reported experiencing high levels of fatigue with a mean fatigue score of 30.80 ± 6.92, out of a total possible score of 50. Moreover, over one-third of the participants indicated that they became exhausted very quickly. Additionally, 24.9% (50/201) reported feeling mentally drained. Physically active students had lower levels of fatigue compared to inactive students, as evidenced by both categorical analysis (p = 0.043) and median fatigue scores (physically active scored less, as 30.00, IQR: 12.00, comparing to inactive 32.00, IQR: 6.00) (p = 0.038). Similarly, nonsmokers had lower levels of fatigue compared to smokers (p = 0.049). Additionally, median fatigue score for fourth-year (33.00(IQR:6.00) and interns was, 32.00(IQR:12.00), indicating a significant difference in median fatigue score based on the year of study (p = 0.044). Likewise, smokers 33.00 (IQR:6.00) exhibited higher median fatigue scores compared to non-smokers and ex-smokers, however the difference was not significant (p = 0.051). Our findings reveal that students experience high levels of fatigue, which can have detrimental effects on their physical and mental well-being. Notably, students who engaged in regular physical activity and did not smoke reported lower levels of fatigue, suggesting that these healthy habits are significantly associated with reduced fatigue. Policies and advocacy implemented through multiple channels encouraging physical activity and banning possible risk factors (like smoking) with the compass may alleviate the burden of fatigue and improve the ability to learn, preventing burnout and well-being of students are recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fatigue is a subjective experience of tiredness or energy depletion affecting individuals across all ages and professions1,2. Characterized by physical, mental, or emotional exhaustion, fatigue impairs daily functioning, productivity, and overall well-being3,4,5. In healthcare students, fatigue can have severe consequences, including decreased academic performance, compromised patient care, and increased burnout risk3,4,5. Two distinct types of fatigue exist: peripheral (physical) fatigue, resulting from physical exertion, and central (mental) fatigue, affecting cognitive functions like attention and memory6,7. Fatigue is a prevalent health complaint, ranking among the top five in primary care1,8. It is defined as persistent and excessive tiredness, weakness, or exhaustion that persists despite rest9. As a multidimensional concept, fatigue is experienced by both healthy individuals and those with medical conditions1.

Fatigue is a widespread global issue, affecting individuals across the world with an overall prevalence of 59%10. This rate rises even further among those suffering from mental or behavioral health conditions, reaching 65.9%11. Despite its widespread nature, the prevalence of fatigue varies considerably among different populations10,12,13,14. For instance, in the general population, rates range from 4.3% to 21.9%12 while among the Chinese students, it is reported at 40%13. Jordanian students experience a prevalence of 59%14, and medical students report that 44.4% suffer from severe fatigue15. Among nursing students, the prevalence climbs to 67.3%16. In the United States, college students report experiencing fatigue throughout the week at a rate of 24.1%, with 16.4% indicating they feel fatigued for three days or more17. Similarly, in Egypt, 53.5% of medical students report experiencing fatigue18. In Saudi Arabia, the prevalence of fatigue among healthcare professionals also varies19,20. A study among nurses in eastern Saudi Arabia found a prevalence of 35.3%20, while medical students at a Saudi university reported a much higher rate of 69.7%19.

It is believed that university students experience a significant increase in workload, frequently writing exams, attending various courses and labs in their regular academic curriculum, and facing competition among students to achieve higher scores. These factors may contribute to mental distress and other academic challenges, leading to fatigue21. On the other hand, literature on the factors contributing to fatigue among university students reveals that those with irregular or insufficient sleep habits, following weight-loss diets, engaging in excessive or insufficient exercise, or spending a lot of time traveling and working are more likely to experience physiological fatigue22,23.

The rigorous and demanding nature of healthcare education can require students to maintain intense focus, potentially affecting their ability to perform academically24,25. Healthcare students face unique challenges in completing academic responsibilities, which alter their physical and mental well-being25. The academic life of the students involves intense competition and pressure to succeed, which can alter cognitive function26,27,28, leading to decreased concentration, memory retention, and motivation27,28,29. Additionally, prolonged study hours can cause physical fatigue, further compromising students’ ability to focus and engage with their studies6,28. This fatigue can exacerbate stress levels, ultimately impacting overall well-being and health25. While fatigue among healthcare professionals, including nurses and medical students, has been extensively studied, our research fills a knowledge gap by focusing on nursing students in Saudi Arabia, a previously understudied population. By investigating self-reported fatigue and its associated factors, aiming to identify unique challenges and stressors faced by healthcare students in a university in Saudi Arabia that may contribute to fatigue, and further to provide insights that can inform the development of targeted interventions and support systems for healthcare students. Therefore, this study aims to assess self-reported fatigue and its associated factors, focusing on the assessment of health and wellness among healthcare students at a university in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Method

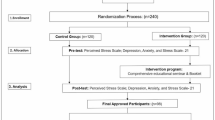

Study design, setting, and population

An online analytical survey was conducted from March to May 2024 among nursing students enrolled in a nursing program at a King Saud university in the capital region of Saudi Arabia. Male and female students between 19 and 25 years old, willing to provide informed consent, and attending classes regularly were eligible to participate. Students under 18 years old were excluded, as well as students from other departments. Before data collection, the study protocol and questionnaires were reviewed and approved by the King Saud University Research Ethics Committee for Human Research (KSU-HE-24-544). The study procedure was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines for human research. In addition, informed consent was obtained from all students, who were assured that their data would only be used for research purposes and that confidentiality would be maintained throughout the study.

Sample selection and recruitment process

The students were selected using a simple random sampling method from the official enrollment list provided by the university’s student affairs department. The sample frame consisted of all nursing students enrolled in the program. Data collection utilized an online questionnaire created via Google Forms. We visited the classrooms of nursing students, briefly explained the study’s purpose and significance, and distributed the questionnaire links via their preferred communication channels (WhatsApp or email), ensuring convenience and accessibility for potential participants. To mitigate selection bias, only students meeting the inclusion criteria were invited30. To overcome the response bias, we provided clear instructions on the survey’s purpose, procedures, and questions30. Additionally, responses were anonymous to encourage honest answers. Accessibility bias was controlled by the online survey platform, and use of computers as the survey was designed to be accessible on various devices, including Mobiles and computers or laptops, and optimized to facilitate participation. Further social desirability bias was controlled through questions that were phrased in a neutral and non-judgmental manner31,32. Students were assured that their responses would be confidential. Two follow-up reminders were sent to minimize non-response bias and encourage a representative sample. To address social desirability bias, students were informed that their responses would remain anonymous and confidential32. Data collection continued until the target sample size was reached.

Sample size estimation

The sample size for this study was calculated based on the following formula for descriptive studies

where N = Population size (N) = 500; P = Hypothesized % frequency (p) = 30% or 0.3; d = Confidence limits (d) = 5% or 0.05; DEFF = Design effect (DEFF) = 1; Z = Confidence level = 95% (Z = 1.96).

After adding this value

Plugging in values:

So total 197 respondents are required for this study. Anticipating a 10% attrition rate, we adjusted our target sample size to at least 217 participants to maintain the study’s validity. To further enhance the study’s power, minimize sampling bias, and optimize accuracy, we invited 250 students to participate. Ultimately, 201 students provided complete responses that met the inclusion criteria, yielding a satisfactory sample for analysis.

Questionnaire

The questionnaires used for this study were adopted from previously validated studies on fatigue assessment and associated factors33,34,35. The questionnaire consisted of 20 questions and was divided into 3 sections as follows. The first section of the study collected demographic data of the students, including age, gender, level of education, and academic performance (grade point average (GPA) in the Last semester. The second section dealt with the general health-related characteristics of the students and included a total of 6 items33. The third section of the study, about the fatigue assessment (10 items) scale (FAS), asked students to rate their levels of fatigue on a five-point Likert scale ranging from never, sometimes, regularly, often, and always35. The questionnaire was administered in English and Arabic to accommodate all students and minimize language-related response bias. To ensure the compatibility of the Arabic and English versions of the questionnaire, we conducted forward-backward translation method36,37. In this the questionnaire was first translated from English to Arabic by a bilingual expert, and then back-translated to English by another independent bilingual expert37. The original and back-translated English versions were compared for consistency and accuracy. After the initial draft of the questionnaires, it was subjected to content validation by five experts in the field of nursing, public health, and epidemiology, who reviewed the questionnaires in three rounds to ensure clarity, relevance, and appropriateness of items. The Content Validity Index (CVI) was used to quantify expert agreement, with a final CVI score above 0.80, indicating strong content validity. Later, a pilot study was conducted among a randomly selected sample of students (n = 20) to assess the face validity and internal consistency. The pilot study findings were not included in the main findings.

Data collection utilized an online questionnaire created via Google Forms. We visited the classrooms of Nursing students, briefly explaining the study’s significance to those present, and distributed the questionnaire links via their preferred method (WhatsApp or email). Data collection fallowed simple random sampling method to select participants, ensuring every student had an equal chance of being included. The data collection was continued until the target sample size was reached. To optimize response rates, reminders were sent to students to complete the questionnaires.

Scoring and fatigue levels

The scoring was carried out by allocating a score of 1 for never, 2 for infrequently, 3 for regular intervals, 4 for often, and 5 for always. The overall mean score was computed by combining all 10 items. Fatigue levels were then categorized into two groups based on percentile rankings:

-

Low fatigue: scores below the 10th percentile.

-

Higher fatigue: scores at or above the 10th percentile.

Statistical analyses

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 24 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were presented as frequencies (n) and percentages (%). To examine associations between variables, we used chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. The Shapiro-Wilk test revealed a significant deviation from normality (p < 0.001), indicating that the data did not follow a normal distribution. Consequently, we employed non-parametric tests for further analysis. To identify predictors of fatigue, we used the Mann-Whitney U test for demographics with two categories and the Kruskal-Wallis test for demographics with more than two categories. logistic regression was applied to find out the predictors of fatigue. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all analyses.

Results

Socio-demographic and academic-related characteristics of students

A total of 201 students responded to the study, giving a response rate of 80.4% (201/250). Of these, 87.1% (175/201) were males, with a mean age of 22.86 ± 1.63(Std) (median 23) years. The age distribution showed that 43.8% (88/201) were between 24 and 25 years old, while 36.3% (73/201) were between 22 and 23 years old. Regarding academic status, 33.8% (68/201) were interns and 20.9% (42/201) were second-year nursing students. The mean GPA of the students was 4.32 ± 0.709 (median 4.48). Most participants reported a GPA between 4 and 5, as presented in Table 1.

General health characteristics of students

Regarding health-related characteristics, the findings revealed that 4.5% (9/201) of the students had a family history of chronic diseases, while 13.4% (27/201) were current smokers and 72.6% (146/201) identified as nonsmokers. Additionally, 58.2% (117/201) of the students reported being physically active, and 45.8% (92/201) indicated they spent between 6 and 9 h daily on the computer. A detailed summary of the students’ general health-related characteristics is presented in Table 2.

The assessment of fatigue among the 201 students, as detailed in Table 3, revealed several notable patterns. Fatigue was a common concern, with 26.4% of students (53/201) reporting that it bothered them sometimes, and 24.4% (49/201) stating it affected them often. The mean score for fatigue was 3.30 ± 1.22, with an interquartile range (IQR) of 2. A significant proportion (36.3%, 73/201) noted that they became exhausted quickly at times, with a mean exhaustion of 3.06 ± 1.28.

In terms of productivity, 35.8% (72/201) sometimes felt they were not accomplishing much, with a mean productivity of 2.92 ± 1.40, while 18.9% (38/201) experienced this feeling frequently. Energy levels also fluctuated, with 34.8% (70/201) reporting that they sometimes had sufficient energy to carry out daily tasks. Physical and mental exhaustion were commonly experienced, with 37.8% (76/201) and 24.9% (50/201), respectively, reporting occasional episodes. Additionally, cognitive challenges were evident, as 31.8% (64/201) sometimes struggled with thinking clearly, and 28.9% (58/201) reported a lack of motivation. Concentration difficulties were also notable, with 27.4% (55/201) of students often finding it hard to focus.

In this study, 11.4%(n = 23/201) of the students reported the lowest levels of fatigue, while the majority, 88.6%(n = 178/201), had the highest levels of fatigue. The associations between students’ fatigue levels and factors such as gender, year of study, smoking status, history of a physician-diagnosed chronic disease, living with family, attendance at courses or lectures on fatigue, hours spent working on a computer per day, number of meals per day, and physical activity status were determined using chi-square or Fisher exact tests at the p < 0.05 level of significance. The results showed that smoking and physical activity status had a significant association with levels of fatigue (p < 0.001). For example, physically active students had lower levels of fatigue compared to others (p = 0.043). Similarly, nonsmokers had the lowest levels of fatigue compared to smokers (p = 0.049), indicating a statistically significant difference. According to the data presented, the level of fatigue was not significantly associated with gender (p = 0.520), year of study (p = 0.296), history of a physician-diagnosed chronic disease (p = 0.299), or living with family (p = 0.219).

Regression analysis (Table 4) revealed that none of the demographic factors showed a statistically significant association with fatigue. However, physically active students were more likely to report fatigue compared to those who were not active, though the association was not-significant (Adjusted OR 2.847, p = 0.060). Male students were less likely to report fatigue compared to females (AOR 0.478, p = 0.413). Students aged 19–21 years showed a higher likelihood of fatigue than those aged 24–25 years (AOR 8.160, p = 0.231), followed by students aged 22–23 years (AOR 1.211, p = 0.818). Compared to interns, first-year students were less likely to report fatigue (AOR 0.037, p = 0.072), while second, third-, and fourth-year students also showed lower likelihoods, with the lowest among fourth years (AOR 0.363, p = 0.235). Smokers were more likely to experience fatigue (AOR 2.456, p = 0.562), while non-smokers were less likely (AOR 0.365, p = 0.365) compared to those who smoked occasionally. Ex-smokers also showed slightly higher odds (AOR 1.458, p = 0.124). Students with a physician-diagnosed chronic disease were more likely to report fatigue (AOR 2.500, p = 0.347). Those living with family were less likely to report fatigue (AOR 0.420, p = 0.350). Compared to those spending 10 or more hours on the computer, students spending 6–9 h had lower odds of fatigue (AOR 0.478, p = 0.166), and those using computers for less than 5 h showed even lower odds (AOR 0.901, p = 0.904). Regarding meals, students consuming four meals per day were more likely to report fatigue (AOR 2.654, p = 0.093) compared to those taking five or more. Those consuming one to two meals (AOR 0.659, p = 0.154) and three meals (AOR 0.980, p = 0.431) had lower odds.

A Chi-square test examining the relationship between GPA and fatigue agreement levels resulted in a p-value of 0.853, indicating that students with higher GPAs are more likely to agree with higher levels of fatigue. Similarly, an examination of the relationship between students’ age and fatigue agreement level resulted in a p-value of 0.919, indicating that as age increases, individuals are more likely to experience higher levels of fatigue. Furthermore, as the year of study increases, fatigue levels also increase. For instance, students in the fourth year and interns were more likely to have the highest levels of fatigue compared to juniors. However, all these variables (GPA, year of study, and age of the students) were not significantly associated with the levels of fatigue.

As shown in Table 5, the median fatigue score for senior students was higher compared to juniors. For instance, the median fatigue score for fourth-year and interns was 33.00 (IQR:6.00), 32.00(IQR:12.00). Our results indicated a significant difference in median fatigue score based on the year of study (p = 0.044). Additionally, there was a notable difference in fatigue scores based on physical activity status. Specifically, physically active students had a lower median fatigue score 30.00(IQR:12.00)) compared to physically inactive students 32.00 (IQR:6.00)) (p = 0.038), suggesting that physical activity status was a significant predictor of fatigue. Likewise, smokers 33.00 (IQR:6.00) and occasional smokers 33.00(IQR:8.00) exhibited higher median fatigue scores compared to non-smokers and ex-smokers (p = 0.051).

Discussion

Fatigue is a pressing issue among students, potentially leading to adverse academic outcomes and negatively affecting their overall well-being. In response to the research question, findings revealed that fatigue is a significant concern among students, with high levels of fatigue reported. These findings align with previous studies conducted among undergraduate students in other countries8,38. For instance, a study among Chinese nursing students reported a mean fatigue score of 44.9 38. Similarly, a study among Pakistani university students found that 54.9% experienced mild to moderate fatigue, and 6.3% experienced severe fatigue39. In the United Arab Emirates, students reported moderate fatigue levels (range: 22–46)40. In Greece, 39% of healthcare students experienced fatigue12. Similarly, 83.5% of Brazilian nursing students reported moderate to intense fatigue8 while 28% of UK students41, and 20.5% of female students and 6.5% of male students in the Netherlands experienced severe fatigue42. The discrepancies in fatigue levels may be attributed to factors such as inadequate sleep, poor diet, high academic stress, insufficient study breaks, and excessive clinical or academic workload. Regular college attendees may face increased academic demands and stress, compromising their sleep quality and exacerbating fatigue12. These findings highlight the need for targeted interventions and management strategies to address fatigue, promote student well-being, and enhance academic performance. Regular monitoring, preventive measures, and fatigue-mitigation strategies are crucial to protecting students’ learning and health outcomes.

Our study reveals that a substantial proportion of student’s experience mental exhaustion, with 24.9% reporting occasional feelings of exhaustion and 65.2% experiencing it consistently. These findings are consistent with previous research, which found that 86% of college students experience mental fatigue during online academic activities and 74% during traditional academic activities43. Notably, 68.7% of students in our study reported being bothered by fatigue, and 55.2% attempted to overcome it quickly. A study among university students in the UAE also found that a significant percentage experienced fatigue lasting more than five days per week40. These collective findings underscore the pervasive nature of fatigue among students. Given the complexity and serious consequences of fatigue on students’ daily and academic lives, it is crucial to identify key predictors and implement targeted interventions. Collaborative efforts are essential to mitigate the effects of fatigue on student well-being, academic performance, and safety.

In this study outcome of Chi-square and Kruskal–Wallis tests show significant associations between physical activity and lower fatigue, yet regression analysis suggests physically active students were more likely to report fatigue (Adjusted OR 2.847, p = 0.060), however there was no significant association between them. Sometimes fatigue also reported among individuals with excessive physical activity or lifting heavy weights44,45 In addition, individual differences and contextual factors can influence this relationship between fatigue and physical activity45. Further research is needed to explore these dynamics in more depth. In addition, students who did not smoke reported lower levels of fatigue, highlighting the importance of healthy habits in mitigating fatigue. These findings are consistent with earlier research12,39. For instance, Hanif et al. found a significant link between physical activity levels and fatigue among Pakistani university students39. Bouloukaki et al. reported that fatigue was independently associated with lack of physical activity, chronic disease, depression, sleepiness, and poor sleep quality12. In contrast to some previous studies, our research found no significant associations between fatigue levels and certain demographic characteristics, such as gender, year of study, or living situation. However, a study in the UAE reported higher fatigue levels among female students compared to male students, and lower fatigue levels among students aged 26–30, single, employed full-time, and satisfied with assessment frequency40. Given the limited research on variations in fatigue levels among students and their characteristics, further studies are needed to explore these relationships and inform targeted interventions.

A lack of relaxation and self-care habits, as well as unhealthy mental habits such as overthinking and excessive worrying, were common among students and the elderly12,40,43. These habits can contribute to fatigue, negatively impacting mental strain and energy levels. Most of the earlier literature focused on the general population12,40,43. This study aims to promote awareness and healthy lifestyles among healthcare students, ultimately enhancing their overall health status and mitigating fatigue caused by academic and inactivity-related factors. By addressing fatigue and implementing effective management strategies, students can improve their academic performance and quality of life43. This study will serve as a valuable resource for future research, providing insights into the complex relationships between fatigue, lifestyle habits, and academic performance among healthcare students41.

This study has several limitations that warrant consideration. Firstly, the reliance on a self-administered online questionnaire may have introduced biases, such as recollection bias. Secondly, the study’s scope was limited to a single university in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings to other contexts. Additionally, the study focused exclusively on nursing students, which may not be representative of the broader student population. Therefore, the results may not be representative of the entire college community or the broader Saudi population within the same age group. This limitation should be considered when interpreting the findings and applying them to other contexts. Another possible limitation is the underrepresentation of female students and the overrepresentation of 4th-grade students, older students, and those with higher GPAs. Future studies should aim to control for these variables and ensure more diverse representation. Furthermore, the phrasing of the physical activity question may introduce subjectivity and social desirability bias. To address this, future research could employ more objective measures, such as validated physical activity questionnaires or wearable devices, to assess physical activity levels more accurately.

Implications and recommendations

Despite these limitations, the study’s findings can inform policymakers and healthcare professionals in developing targeted interventions to promote healthy lifestyles and address fatigue among students. By increasing awareness of fatigue and its impact, we can work towards improving the overall health and well-being of individuals in the community. Therefore, we recommend that universities and colleges in Saudi Arabia and other countries prioritize promoting healthy habits among students. This can be done by providing access to fitness facilities or wellness programs. Additionally, educators and administrators should be aware of the potential impact of fatigue on student performance. They should provide support services, such as counseling or academic advising, to help students manage fatigue. Curriculum planners should also consider incorporating content on self-care and stress management to help students develop healthy coping mechanisms. Further research is needed to explore the causes of fatigue among nursing students and to develop targeted interventions to mitigate its effects.

Conclusion

Our findings reveal that students experience high levels of fatigue, which can compromise their physical and mental well-being, learning ability, and academic performance. Notably, regular physical activity and non-smoking habits are significantly associated with reduced fatigue. If left unaddressed, fatigue can lead to absenteeism, lower grades, and academic failure. These results highlight the need for targeted support programs that promote self-care, healthy habits, and stress management. By creating a safe and supportive learning environment, educational institutions can help students succeed academically and in their future careers as emergency medical technicians.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Billones, R., Liwang, J. K., Butler, K., Graves, L. & Saligan, L. N. Dissecting the fatigue experience: A scoping review of fatigue definitions, dimensions, and measures in non-oncologic medical conditions. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 15, 100266 (2021).

Johansson, B., Dobryakova, E. & van der Naalt, J. Pathological fatigue from neurons to behavior. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 16, 973190 (2022).

Billones, R., Liwang, J. K., Butler, K., Graves, L. & Saligan, L. N. Dissecting the fatigue experience: A scoping review of fatigue definitions, dimensions, and measures in non-oncologic medical conditions. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 15, 100266 (2021).

Supriyadi, T., Sulistiasih, S., Rahmi, K., Pramono, B. & Fahrudin, A. The impact of digital fatigue on employee productivity and well-being: A scoping literature review. Environ. Soc. Psychol. 10(2) (2025).

Santos, M. A. et al. Fatigue and quality of life in emergency healthcare professionals. Texto Contexto Enferm. 33, e20240114 (2024).

Kunasegaran, K. et al. Understanding mental fatigue and its detection: A comparative analysis of assessments and tools. PeerJ 11, e15744 (2023).

Tornero-Aguilera, J. F., Jimenez-Morcillo, J., Rubio-Zarapuz, A. & Clemente-Suárez, V. J. Central and peripheral fatigue in physical exercise explained: A narrative review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19(7), 3909 (2022).

Amaducci, C. M., Mota, D. D. & Pimenta, C. A. Fatigue among nursing undergraduate students. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 44, 1052–1058 (2010).

Dittner, A. J., Wessely, S. C. & Brown, R. G. The assessment of fatigue: A practical guide for clinicians and researchers. J. Psychosom. Res. 56(2), 157–170 (2004).

Hertanti, N. S., Nguyen, T. V. & Chuang, Y-H. Global prevalence and risk factors of fatigue and post-infectious fatigue among patients with dengue: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 80 (2025).

Park, N-H. et al. Comparative study for fatigue prevalence in subjects with diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 23348 (2024).

Bouloukaki, I. et al. Sleep quality and fatigue during exam periods in university students: Prevalence and associated factors. In Paper Presented at: Healthcare (2023).

Li, W., Chen, J., Li, M., Smith, A. P. & Fan, J. The effect of exercise on academic fatigue and sleep quality among university students. Front. Psychol. 13, 1025280 (2022).

Shoiab, A. et al. Evaluation of prevalence of fatigue among Jordanian university students and its relation to COVID-19 quarantine. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 10(E), 1898–1903 (2022).

Zhong, X., Chen, J., Yang, B. & Li, G. Compassion fatigue among medical students and its relationship to medical career choice: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Med. Educ. 25(1), 742 (2025).

Liu, S. et al. The prevalence of fatigue among Chinese nursing students in post-COVID-19 era. PeerJ 9, e11154 (2021).

Statista. Percentage of U.S. College students that felt tired or sleepy within the past seven days as of fall 2023 (2024).

Ghanem, E. A., Elhussiney, D. M. & Elbadawy, D. A. Prevalence, risk factors of videoconference fatigue, and its relation to psychological morbidities among Ain Shams medical students, Egypt. Egypt. J. Community Med. 41(2), 111–117 (2023).

Alkhamees, A. A. et al. Fatigue syndrome among medical students in Saudi arabia: A cross-sectional study on depression and anxiety. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 16(Suppl 5), S4623–S4627 (2024).

Britiller, M. C., Hassan, E. M. & Anna, R. A. Factors associated with the physical and mental fatigue levels of nurses in the Eastern region Hospitals, Saudi Arabia. J. Biosci. Appl. Res. 10(4), 842–855 (2024).

Romero-Rodríguez, J-M., Hinojo-Lucena, F-J., Kopecký, K. & García-González, A. Digital fatigue in university students as a consequence of online learning during the Covid-19 pandemic. Educ. XX1 26(2), 141–164 (2023).

Schiffert Health Center. Fatigue and the College Student. https://healthcenter.vt.edu/content/dam/healthcenter_vt_edu/assets/docs/MCInfoSheet-Fatigue.pdf. Accessed 9 Sept 2024 (2010).

Mayo Clinic. Symptoms Fatigue. https://www.mayoclinic.org/symptoms/fatigue/basics/causes/sym-20050894. Accessed 9 Sept 2024.

Samreen, S., Siddiqui, N. A. & Mothana, R. A. Prevalence of anxiety and associated factors among pharmacy students in Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020(1), 2436538 (2020).

Abdulghani, H. M., AlKanhal, A. A., Mahmoud, E. S., Ponnamperuma, G. G. & Alfaris, E. A. Stress and its effects on medical students: A cross-sectional study at a college of medicine in Saudi Arabia. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 29(5), 516 (2011).

Jiang, M. M., Gao, K., Wu, Z. Y. & Guo, P. P. The influence of academic pressure on adolescents’ problem behavior: Chain mediating effects of self-control, parent-child conflict, and subjective well-being. Front. Psychol. 13, 954330 (2022).

Iqra, N. A systematic—Review of academic stress intended to improve the educational journey of learners. Methods Psychol. 11(1), 1–9 (2024).

Kotnik, P., Roelands, B. & Bogataj, Š. Prolonged theoretical classes impact students’ perceptions: An observational study. Front. Psychol. 15, 1278396 (2024).

Pérez-Jorge, D., Boutaba-Alehyan, M., González-Contreras, A. I. & Pérez-Pérez, I. Examining the effects of academic stress on student well-being in higher education. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 12(1), 1–13 (2025).

Elston, D. M. Participation bias, self-selection bias, and response bias. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. (2021).

Ingram O. What is Social Desirability Bias – Causes & Examples. Research prospect. https://www.researchprospect.com/what-is-social-desirability-bias/. Accessed 4 Sept 2025 (2023).

Ried, L., Eckerd, S. & Kaufmann, L. Social desirability bias in PSM surveys and behavioral experiments: Considerations for design development and data collection. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 28(1), 100743 (2022).

Michielsen, H. J., De Vries, J. & Van Heck, G. L. Psychometric qualities of a brief self-rated fatigue measure: The fatigue assessment scale. J. Psychosom. Res. 54(4), 345–352 (2003).

Hendriks, C., Drent, M., Elfferich, M. & De Vries, J. The fatigue assessment scale: Quality and availability in sarcoidosis and other diseases. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 24(5), 495–503 (2018).

Shahid, A., Wilkinson, K., Marcu, S. & Shapiro, C. M. Fatigue assessment scale (FAS). In STOP, THAT and One Hundred Other Sleep Scales 161–162 (Springer, 2011).

Degroot, A. M., Dannenburg, L. & Vanhell, J. G. Forward and backward word translation by bilinguals. J. Mem. Lang. 33(5), 600–629 (1994).

Bashatah, A. & Alahmary, K. A. Psychometric properties of the Moore index of nutrition self-care in Arabic: A study among Saudi adolescents at King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Nurs. Res. Pract. 2020, 9809456 (2020).

Yi, L-J. et al. Prevalence of compassion fatigue and its association with professional identity in junior college nursing interns: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19(22), 15206 (2022).

Hanif, S., Ahmed, I., Nawaz, R., Shabbir, H. & Asif, K. Association of fatigue level and physical activity among university students: A cross-sectional survey. J. Health Rehabil. Res. 4 (1), 1642–1646 (2024).

Mosleh, S. M., Shudifat, R. M., Dalky, H. F., Almalik, M. M. & Alnajar, M. K. Mental health, learning behaviour and perceived fatigue among university students during the COVID-19 outbreak: A cross-sectional multicentric study in the UAE. BMC Psychol. 10(1), 47 (2022).

Viner, R. M. et al. Longitudinal risk factors for persistent fatigue in adolescents. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 162(5), 469–475 (2008).

Ter Wolbeek, M., Van Doornen, L. J., Kavelaars, A. & Heijnen, C. J. Severe fatigue in adolescents: A common phenomenon? Pediatrics 117(6), e1078–e1086 (2006).

Estandian, V. C. A., Reyes, M. C. C., Torres, R. D. & Gumasing, M. J. J. Evaluation of Mental Fatigue of Students: A Comparison between Traditional and Online Learning in College Students.

Bricout, V. A., Nguyen, D. T. & Favre Juvin, A. Physical activity or inactivity and fatigue in children and adolescents: A cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Med. 14(5) (2025).

Balatoni, I. et al. The importance of physical activity in preventing fatigue and burnout in healthcare workers. In Paper Presented at: Healthcare (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors of this study extend their appreciation to the Ongoing Research Funding Program (ORF-2025-1099), King Saud University, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia.

Funding

This study was funded by the Ongoing Research Funding Program (ORF-2025-1099), King Saud University, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.A.,N.A., Y.A.,W.S. and M.E.A. wrote the main manuscript text and M.B.A. prepared figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alghamdi, A., Alyahya, N., Aldhamri, Y. et al. Online survey of fatigue and associated factors among university students in Riyadh Saudi Arabia. Sci Rep 15, 35210 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21390-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21390-y