Abstract

This study aims to develop a nomogram for predicting the overall survival (OS) of early-onset colorectal cancer with liver metastasis (EOCRC-LM) patients who underwent primary tumor resection combined with chemotherapy. Using the SEER database (2010–2015), we identified EOCRC-LM underwent primary tumor resection and chemotherapy. Eligible cases were randomly split into training/validation cohorts. Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator(LASSO) regression and multivariate Cox analysis identified independent OS predictors, which were integrated into a nomogram. Model performance was assessed via calibration curves, time-dependent Receiver Operating Characteristic, and Decision Curve Analysis (DCA), demonstrating clinical utility. A cohort of 1049 early-onset colorectal cancer patients with liver metastases underwent tumor resection and chemotherapy was analyzed using SEER data (2010–2015), randomly divided into training (n = 734) and validation (n = 315) cohorts. LASSO and multivariate Cox regression identified eight independent prognostic factors: marital status, tumor location, T/N stage, CEA level, lymph node count, and bone/lung metastases. The nomogram showed strong predictive accuracy, with training cohort Area Under the Curve(AUCs) of 0.70 (0.66, 0.73) (2-year), 0.72 (0.68, 0.76) (3-year), and 0.77 (0.72, 0.80) (5-year), and validation cohort AUCs of 0.68 (0.62, 0.74) , 0.71 (0.65, 0.77) , and 0.80 (0.75, 0.86) , respectively. Calibration curves confirmed close alignment between predicted and observed survival, while DCA validated clinical utility for personalized risk assessment. The clinical prediction model developed from SEER data for OS in EOCRC-LM patients underwent combined primary tumor resection and chemotherapy demonstrated robust performance in prognostic evaluation. This nomogram-based tool provides clinicians with reliable quantitative guidance and a theoretical foundation for implementing personalized therapeutic strategies, thereby addressing the critical need for precision medicine in this clinically heterogeneous population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common malignant tumor globally and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths1. Although the incidence of colorectal cancer in the elderly population (> 50 years old) has declined due to widespread screening and advances in treatment, the incidence of early-onset colorectal cancer (EOCRC, diagnosed at ≤ 50 years of age) has rapidly increased globally2, exhibiting a significant trend of younger age onset. Multiple studies have shown that patients with EOCRC are more likely to be diagnosed at advanced stages (III/IV) and have a higher incidence of distant metastasis3,4. EOCRC patients tend to have more aggressive tumors (e.g., higher proportions of mucinous or signet-ring cell carcinoma), which may increase the risk of liver metastasis5. Moreover, EOCRC exhibits higher genetic heterogeneity (with a higher proportion of MSI-H and enriched specific gene mutations), stronger immunogenicity (elevated TMB and PD-L1 expression), and unique activation of signaling pathways related to the immune microenvironment6. In contrast, late-onset colorectal cancer (LOCRC) relies more on traditional driver gene mutations and chronic inflammation-related pathways. LOCRC predominantly exhibits microsatellite stability (MSS), with driver mutations such as KRAS and BRAF being more common7. The differences between EOCRC and LOCRC suggest that early-onset liver metastasis is characterized by greater genetic heterogeneity and immune evasion, while late-onset cancer is more driven by traditional carcinogenic pathways.

The treatment of early-onset colorectal cancer liver metastasis (EOCRC-LM) is characterized by multidisciplinary collaboration, with the combined use of surgery and chemotherapy being the current core strategy. In terms of surgery, radical liver resection remains the primary means of achieving long-term survival. However, approximately 80% of patients are unable to undergo direct surgery at diagnosis due to tumor burden or insufficient liver function reserve8,9. For initially unresectable cases, conversion therapy using chemotherapy regimens (e.g., FOLFOX/FOLFIRI combined with targeted drugs) can provide 15–40% of patients with the opportunity for a second-stage surgery10. EOCRC exhibits more aggressive tumor biology, often presenting with high lymph node positivity and synchronous liver metastasis11. However, retrospective studies show that after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and downstaging, the 5-year survival rate of EOCRC-LM patients undergoing R0 resection can reach 35–50%, with no significant difference compared to late-onset patients12. Furthermore, the application of chemotherapy must balance efficacy with toxicity. Long-term chemotherapy may lead to chemotherapy-associated liver injury (CALI), such as sinusoidal obstruction and steatosis, which increases the risk of posthepatectomy liver failure (PHLF)13. For younger patients, clinicians often tend to use more intensive chemotherapy regimens, but existing evidence suggests that this age-related bias does not lead to clear survival benefits14. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) can reduce early recurrence rates in specific high-risk patients, while adjuvant chemotherapy can prolong disease-free survival, especially in patients with synchronous liver metastasis15. Advances in minimally invasive surgery (laparoscopic/robotic) have reduced perioperative risks during simultaneous resection of primary and liver metastatic lesions16, while the combination of molecular targeted drugs and chemotherapy has further optimized systemic treatment outcomes17. Currently, there is controversy regarding the survival benefit of resecting the primary tumor in patients with unresectable liver metastasis, as this benefit remains unclear18. A comprehensive evaluation, including tumor burden and genetic status (e.g., RAS mutations), is necessary.

This study aims to analyze the impact of primary tumor resection combined with chemotherapy on survival in early-onset colorectal cancer patients with liver metastases using the SEER database, develop a survival prediction model, provide individualized treatment guidance for clinicians, assess which patients may benefit from this treatment strategy, and support decision-making with data-driven evidence.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

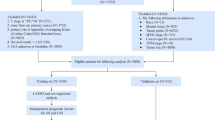

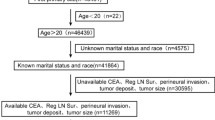

The data for this study was sourced from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database (www.SEER.cancer.gov), which includes 17 registries, as of November 2023 (covering data from 2000 to 2021). Patient data was downloaded using SEER*Stat version 8.4.4.Since SEER does not include personal identifying information, this study does not require approval from an ethics committee or informed consent. A total of 23,798 patients under the age of 50 were downloaded from the data, with patients whose information was invalid or incomplete excluded from the study. Ultimately, 1049 patients were included and randomly divided into a training group and a validation group in a 7:3 ratio. The data screening process is shown below (Fig. 1).

Statistical analysis

In this study, all statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 3.6.1), with a P value < 0.05 (two-tailed) considered statistically significant. All patients were randomly divided into a training group and a validation group using R software. The distribution of variables between the two groups was compared using the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. In the training group, the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression analysis was used to identify relevant prognostic risk factors from the clinical variables. Multivariable Cox regression was then used to further examine non-zero coefficient variables in order to determine independent prognostic factors for EOCRC-LM patients who underwent primary tumor resection combined with chemotherapy. Additionally, a new diagnostic nomogram was constructed using the “rms” package based on independent risk factors. The newly established nomogram model was then evaluated using the validation group, generating a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and calculating the corresponding area under the curve (AUC) to assess its discriminatory ability. In addition, calibration curves and decision curve analysis (DCA) were used to evaluate the performance of the nomogram. Based on the nomogram score, patients were classified into low- and high-risk groups, and the risk model was visualized using “ggrisk.”

Result

Characteristics of included cases

Based on the inclusion criteria, a total of 1049 cases were included in this study, with 734 cases randomly assigned to the training group and 315 cases to the validation group. Among all patients, 45.1% were male and 54.9% were female. Of the patients, 33.6% were unmarried, 54.5% were married, and 11.9% were widowed or divorced.Rectal cancer accounted for 18.5%, and colon cancer for 81.5%, with the highest proportion being left-sided colon cancer, which accounted for 51.7%. Bone metastasis was present in 2.9%, and lung metastasis in 15.6%. Among them, 4.2% of patients were aged ≤ 29 years, while 95.8% were aged between 30 and 49 years. Tumor stages T1-T4 accounted for 3.3%, 3.6%, 59.3%, and 33.7%, respectively.143 patients (13.6%) had a history of radiotherapy, and 622 patients (59.3%) were CEA-positive. No significant differences were found between the training group and the validation group for each included variable (Table 1).

Nomogram establishment

The LASSO regression model initially selected 14 variables as prognostic risk factors for EOCRC-LM patients who underwent primary tumor resection combined with chemotherapy (Fig. 2). To enhance the interpretability of the model, only non-zero coefficient variables selected based on the minimum one standard error criterion were retained. Ultimately, nine risk factors—marital status, primary tumor location, T stage, N stage, CEA, number of lymph nodes dissected during surgery, history of radiotherapy, bone metastasis, and lung metastasis—were used in multivariate Cox regression analysis for overall survival (OS) (Table 2) to determine independent prognostic factors for OS. In the multivariate OS analysis, marital status, primary tumor location, T stage, N stage, CEA, number of lymph nodes dissected during surgery, bone metastasis, and lung metastasis were significantly associated with patient OS. Therefore, based on the independent prognostic risk factors from the multivariate analysis, we constructed OS nomogram models for 2-year, 3-year, and 5-year survival (Fig. 3).

Nomogram validation

The calibration curve of the OS prediction model showed excellent consistency between predicted and actual risks, closely following the diagonal, confirming their high predictability and accuracy (Fig. 4). The time-dependent ROC curve highlighted the model’s sensitivity and specificity. In the training set, the AUC for the OS model at 2, 3, and 5 years was 0.70, 0.72, and 0.77, respectively; in the validation set, the AUCs were 0.68, 0.71, and 0.80, respectively (Fig. 5). Additionally, decision curve analysis indicated that, compared to traditional TNM staging, these predictive models offer better clinical applicability (Fig. 6).

Risk stratification and visualization of predictive models

This study constructed a predictive model for EOCRC-LM patients who underwent primary tumor resection combined with chemotherapy based on LASSO regression and Cox proportional hazards models, and visualized the model’s risk stratification and variable contributions using the “ggrisk” package (Fig. 7). The survival rate of patients in the high-risk group (red) was significantly lower than that of the low-risk group (log-rank p < 0.001), indicating that the model has clinical applicability.

Discussion

In this study, 8 independent prognostic factors were selected from 14 prognostic factors to construct a prognostic nomogram for EOCRC-LM patients who underwent primary tumor resection combined with chemotherapy. This suggests that the prognosis of these patients is likely to be related to a greater number of variables. The 2-, 3-, and 5-year AUC values and the calibration curve of this model indicate that the risk model has good discriminatory ability,and can be used to provide individualized treatment for EOCRC-LM patients by combining multiple risk factors, selecting those who will benefit from primary tumor resection combined with chemotherapy. Age was not included as an independent prognostic risk factor during model construction. First, multiple studies have shown that after adjusting for molecular markers (such as RAS/BRAF mutation status), the survival difference between early-onset (< 50 years) and late-onset patients is no longer significant19,20. This suggests that the prognostic value of age may be masked by the tumor’s biological characteristics. Secondly, immune microenvironment analysis shows no significant difference in immune cell infiltration in liver metastases between younger and older patients21. Furthermore, molecular-level heterogeneity (such as Claudin-2 expression) may drive metastasis more than the effect of age itself22. Additionally, treatment-related factors such as chemotherapy responsiveness and timing of primary tumor resection have a more direct impact on prognosis23. These data collectively suggest that age may indirectly affect prognosis by mediating other biological or treatment-related variables, rather than being an independent risk factor. Multiple studies have confirmed that marital status is an independent protective prognostic factor for colorectal cancer patients, significantly associated with earlier diagnosis and longer survival24. Marital support may improve prognosis by enhancing treatment adherence and providing psychological support, and our analysis also supports this finding. In T1-stage early-onset colorectal cancer liver metastasis patients, a paradoxical phenomenon was observed: despite the primary tumor being early-stage, their prognosis was worse than that of T3/T4 stage metastatic patients. This may be related to T1-stage tumors being more prone to occult metastasis or having distinct biological behaviors25. These patients often present with characteristics such as rectal origin, high differentiation, few lymph node metastases, and elevated CEA levels26, indicating the need for a targeted prognostic model to optimize treatment strategies.

The study found significant differences in the impact of the tumor’s primary site on prognosis. First, right-sided colon cancer (R-CC) is more commonly associated with RAS/BRAF mutations and mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR), leading to increased invasiveness and poor prognosis27,28. Left-sided colon cancer (L-CC) and rectal cancer (ReC) are predominantly associated with TP53 mutations, but rectal cancer has a higher risk of recurrence29,30. Additionally, left-sided tumors have a higher rate of liver metastasis, whereas right-sided tumors are more likely to have multifocal metastases and mucinous adenocarcinoma, leading to worse prognosis. Rectal cancer, however, has a higher risk of local recurrence, and its recurrence-free survival rate is lower than that of left-sided colon cancer31. Thus, the primary tumor site affects prognosis through molecular heterogeneity and metastatic patterns. The number of lymph nodes dissected is one of the key factors influencing prognosis. For patients undergoing primary tumor resection combined with chemotherapy, adequate lymph node dissection not only helps with accurate staging but also significantly improves survival outcomes32. Lymph node metastasis status (e.g., lymph node ratio, LNR) is closely related to liver metastasis burden. A high LNR (e.g., ≥ 0.25) indicates a poorer overall survival rate33. Inadequate lymph node dissection may result in undetected occult metastasis, thereby increasing the risk of postoperative recurrence. It is noteworthy that neoadjuvant chemotherapy may reduce the number of detectable lymph nodes, but standardized dissection can still maintain the accuracy of prognostic assessment. Additionally, CEA positivity significantly impacts patient prognosis. In I-II stage patients who did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy, increasing CEA levels can independently predict the risk of recurrence34. For patients undergoing liver resection combined with chemotherapy, abnormal CEA levels not only suggest a higher tendency for liver metastasis but are also associated with a decrease in 3-year disease-free survival rate35. It is worth noting that dynamic changes in CEA levels (e.g., reduction after chemotherapy) can reflect the tumor’s sensitivity to systemic chemotherapy (e.g., FOLFIRI combined with targeted therapy) and predict survival benefits36. Therefore, the prognostic model includes CEA as a stratification variable, combined with the primary tumor site, allowing for more accurate long-term prognosis assessment of EOCRC-LM patients.The presence of bone and lung metastasis greatly influences the survival prediction for EOCRC-LM patients, as metastatic disease is a key prognostic factor37.Patients with bone or lung metastasis have significantly lower survival rates, further highlighting the aggressiveness of metastatic EOCRC, which requires accurate prediction to optimize systemic treatment and assess the potential for palliative therapy38.

In the current treatment strategies for EOCRC-LM, combined primary tumor resection (PTR) and chemotherapy has become an important area of research. Existing evidence suggests that PTR can improve survival in patients with synchronous metastasis, particularly for those with liver metastases that remain unresectable after chemotherapy. PTR may prolong overall survival (OS) by reducing tumor burden and metastatic potential39. However, the extent of its benefit is significantly influenced by molecular characteristics (such as RAS/BRAF mutation status)40. Regarding chemotherapy, neoadjuvant treatment (neoCTx) can increase the rate of liver resection, but its liver injury risk must be balanced with survival benefits41. The lack of early efficacy evaluation tools (such as continuous variable models based on tumor diameter and lesion count) may delay treatment plan adjustments for non-responders42, It is important to note that the synergistic mechanisms between PTR and chemotherapy still need further exploration, including biological processes such as the reactivation suppression of dormant tumor cells (e.g., FBX8 pathway) and liver microenvironment remodeling (e.g., Claudin-2-mediated metastatic colonization). Future directions should focus on multicenter validation of dynamic predictive models and explore the potential for combining immunotherapy with existing treatment regimens22,43.

This study integrated multiple variables, enabling the model to provide dynamic survival predictions, suitable for follow-up management at different time points. Additionally, the intuitive scoring system is easy to implement in clinical practice. Validation with the calibration curve showed that the model exhibits good predictive performance and stability. High-risk patients (e.g., CEA-positive) can be identified through the model, optimizing adjuvant treatment plans;while low-risk patients can avoid overtreatment.

Limitions

Although this study model relies on the extensive case resources of the SEER database, its clinical information dimensions still have significant limitations, providing clear directions for the improvement of future research. Specifically, the database lacks key parameters related to the diagnostic and treatment process, such as the number and extent of liver metastases, the choice of chemotherapy regimen for liver metastasis, the number of treatment cycles, adjustments to drug doses, and the use of targeted therapies. This missing core treatment data may limit the reliability of the model’s evaluation results. It is noteworthy that the database has not yet integrated molecular pathological features with important prognostic value in colorectal cancer diagnosis and treatment (such as KRAS/BRAF mutation status and microsatellite instability). These biological markers have been shown to be closely related to tumor invasiveness and treatment sensitivity. Incorporating these into the multivariate analysis model should be a key breakthrough in future research.

Conclusion

In this study, we identified independent risk factors for (EOCRC-LM patients who underwent primary tumor resection combined with chemotherapy based on the SEER database, and constructed and validated a survival prediction model for these patients. The model demonstrates good accuracy and potential clinical applicability.

Data availability

All data analyzed in this study are included in the supplementary files.

References

Siegel, R. L., Wagle, N. S., Cercek, A., Smith, R. A. & Jemal, A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 73(3), 233–254. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21772 (2023).

Arnold, M. et al. Global patterns and trends in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Gut 66(4), 683–691. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310912 (2017).

Ren, B., Yang, Y., Lv, Y. & Liu, K. Survival outcome and prognostic factors for early-onset and late-onset metastatic colorectal cancer: a population based study from SEER database. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 4377. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-54972-3 (2024).

Nors, J., Gotschalck, K. A., Erichsen, R. & Andersen, C. L. Risk of recurrence in early-onset versus late-onset non-metastatic colorectal cancer, 2004–2019: A nationwide cohort study. Lancet Reg. Health. Eur. 47, 101093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2024.101093 (2024).

Li, S., Keenan, J. I., Shaw, I. C. & Frizelle, F. A. Could microplastics be a driver for early onset colorectal cancer?. Cancers 15(13), 3323. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15133323 (2023).

Tang, J. et al. Molecular characteristics of early-onset compared with late-onset colorectal cancer: A case controlled study. Int. J. Surg. 110(8), 4559–4570. https://doi.org/10.1097/JS9.0000000000001584 (2024).

Hamilton, A. C. et al. Distinct molecular profiles of sporadic early-onset colorectal cancer: A population-based cohort and systematic review. Gastro. Hep. Adv. 2(3), 347–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gastha.2022.11.005 (2022).

Aykut, B. & Lidsky, M. E. Colorectal cancer liver metastases: multimodal therapy. Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 32(1), 119–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soc.2022.07.009 (2023).

Zhang, H. et al. Activin A/ACVR2A axis inhibits epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in colon cancer by activating SMAD2. Mol. Carcinog. 62(10), 1585–1598. https://doi.org/10.1002/mc.23601 (2023).

Papakonstantinou, M. et al. A systematic review of disappearing colorectal liver metastases: Resection or no resection?. J. Clin. Med. 14(4), 1147. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14041147 (2025).

Maki, H. et al. Evolving survival gains in patients with young-onset colorectal cancer and synchronous resectable liver metastases. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. J. Eur. Soc. Surg. Oncol. Br. Assoc. Surg. Oncol. 50(4), 108057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2024.108057 (2024).

Wang, H. W. et al. Impact of age of onset on survival after hepatectomy for patients with colorectal cancer liver metastasis: A real-world single-center experience. Curr. Oncol. (Tor. Ont.) 29(11), 8456–8467. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29110666 (2022).

Hayashi, K. et al. Posthepatectomy liver failure in patients with splenomegaly induced by induction chemotherapy for colorectal liver metastases. J. Gastrointest. Cancer 56(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12029-024-01130-7 (2024).

Mauri, G. et al. Young-onset colorectal cancer: treatment-related nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 13(e3), e885–e889 (2024).

Baidoun, F., Merjaneh, Z., Nanah, R., Saad, A. M. & Abdel-Rahman, O. Impact of perioperative chemotherapy on survival outcomes among patients with metastatic colorectal cancer to the liver. J. Comp. Eff. Res. 11(13), 935–951. https://doi.org/10.2217/cer-2021-0239 (2022).

Shi, X. et al. Simultaneous curative resection may improve the long-term survival of patients diagnosed with colorectal liver metastases: A propensity score-matching study. Surgery 181, 109144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2024.109144 (2025).

Kim, J. S. et al. Hepatic arterial infusion in combination with systemic chemotherapy in patients with hepatic metastasis from colorectal cancer: A randomized phase II study—(NCT05103020)—study protocol. BMC Cancer 23(1), 691. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-11085-w (2023).

Amygdalos, I. et al. Survival after combined resection and ablation is not inferior to that after resection alone, in patients with four or more colorectal liver metastases. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 408(1), 343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-023-03082-1 (2023).

Jácome, A. A. et al. The prognostic impact of RAS on overall survival following liver resection in early versus late-onset colorectal cancer patients. Br. J. Cancer 124(4), 797–804. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-020-01169-w (2021).

Jin, Z. et al. Clinicopathological and molecular characteristics of early-onset stage III colon adenocarcinoma: An analysis of the ACCENT database. J. Nat. Cancer Ins. 113(12), 1693–1704. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djab123 (2021).

Griffith, B. D. et al. Unique characteristics of the tumor immune microenvironment in young patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Front. Immunol. 14, 1289402. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1289402 (2023).

Tabariès, S. et al. Claudin-2 promotes colorectal cancer liver metastasis and is a biomarker of the replacement type growth pattern. Commun. Biol. 4(1), 657. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-021-02189-9 (2021).

Rahbari, N. N., Biondo, S., Frago, R., Feißt, M., Kreisler, E., Rossion, I., Serrano, M., Jäger, D., Lehmann, M., Sommer, F., Dignass, A., Bolling, C., Vogel, I., Bork, U., Büchler, M. W., Folprecht, G., Kieser, M., Lordick, F., Weitz, J., & SYNCHRONOUS and CCRe-IV Trial Groups Primary tumor resection before systemic therapy in patients with colon cancer and unresectable metastases: Combined results of the SYNCHRONOUS and CCRe-IV trials. J. clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 42(13) 1531–1541. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.23.01540 (2024).

Feng, Y. et al. The effect of marital status by age on patients with colorectal cancer over the past decades: A SEER-based analysis. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 33(8), 1001–1010. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-018-3017-7 (2018).

Li, Q., Wang, G., Luo, J., Li, B. & Chen, W. Clinicopathological factors associated with synchronous distant metastasis and prognosis of stage T1 colorectal cancer patients. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 8722. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-87929-x (2021).

Wu, L., Fu, J., Chen, Y., Wang, L. & Zheng, S. Early T stage is associated with poor prognosis in patients with metastatic liver colorectal cancer. Front. Oncol. 10, 716. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.00716 (2020).

Janssens, K. et al. A Belgian population-based study reveals subgroups of right-sided colorectal cancer with a better prognosis compared to left-sided cancer. Oncologist 28(6), e331–e340. https://doi.org/10.1093/oncolo/oyad074 (2023).

Kajiwara, T. et al. Sidedness-dependent prognostic impact of gene alterations in metastatic colorectal cancer in the nationwide cancer genome screening project in Japan (SCRUM-Japan GI-SCREEN). Cancers 15(21), 5172. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15215172 (2023).

Takamizawa, Y. et al. Prognostic role for primary tumor location in patients with colorectal liver metastases: A comparison of right-sided colon, left-sided colon, and rectum. Dis. Colon Rectum 66(2), 233–242. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000002228 (2023).

Ciepiela, I. et al. Tumor location matters, next generation sequencing mutation profiling of left-sided, rectal, and right-sided colorectal tumors in 552 patients. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 4619. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-55139-w (2024).

Inoue, M. et al. Prognostic impact of primary tumour location after curative resection in Stage I-III colorectal cancer: A single-centre retrospective study. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 54(7), 753–760. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyae035 (2024).

Jiao, S. et al. Prognostic impact of increased lymph node yield in colorectal cancer patients with synchronous liver metastasis: A population-based retrospective study of the US database and a Chinese registry. Int. J. Surg. 109(7), 1932–1940. https://doi.org/10.1097/JS9.0000000000000244 (2023).

Ahmad, A. et al. Association of primary tumor lymph node ratio with burden of liver metastases and survival in stage IV colorectal cancer. Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 6(3), 154–161. https://doi.org/10.21037/hbsn.2016.08.08 (2017).

Margalit, O. et al. Assessing the prognostic value of carcinoembryonic antigen levels in stage I and II colon cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 94, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2018.01.112 (2018).

Zhang, R. X. et al. Long-term outcomes of intraoperative chemotherapy with 5-FU for colorectal cancer patients receiving curative resection (IOCCRC): A randomized, multicenter, prospective, phase III trial. Int. J. Surg. 110(10), 6622–6631. https://doi.org/10.1097/JS9.0000000000001301 (2024).

Michl, M., Stintzing, S., Fischer von Weikersthal, L., Decker, T., Kiani, A., Vehling-Kaiser, U., Al-Batran, S. E., Heintges, T., Lerchenmueller, C., Kahl, C., Seipelt, G., Kullmann, F., Stauch, M., Scheithauer, W., Hielscher, J., Scholz, M., Mueller, S., Lerch, M. M., Modest, D. P., Kirchner, T. & FIRE-3 Study Group CEA response is associated with tumor response and survival in patients with KRAS exon 2 wild-type and extended RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer receiving first-line FOLFIRI plus cetuximab or bevacizumab (FIRE-3 trial). Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 27(8) 1565–1572. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdw222 (2016).

Hoshi, Y. et al. Site of distant metastasis affects the prognosis with recurrent/metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma patients treated with Nivolumab. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 28(9), 1139–1146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-023-02381-3 (2023).

Zhao, X., Xu, Z. & Feng, X. Clinical characteristics and prognoses in pediatric neuroblastoma with bone or liver metastasis: Data from the SEER 2010–2019. BMC Pediatr. 24(1), 162. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-024-04570-z (2024).

Kanemitsu, Y., Shitara, K., Mizusawa, J., Hamaguchi, T., Shida, D., Komori, K., Ikeda, S., Ojima, H., Ike, H., Shiomi, A., Watanabe, J., Takii, Y., Yamaguchi, T., Katsumata, K., Ito, M., Okuda, J., Hyakudomi, R., Shimada, Y., Katayama, H., Fukuda, H. & JCOG Colorectal Cancer Study Group Primary tumor resection plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for colorectal cancer patients with asymptomatic, synchronous unresectable metastases (JCOG1007; iPACS): A randomized clinical trial. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 39(10), 1098–1107. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.20.02447 (2021).

Kawaguchi, Y. et al. Contour prognostic model for predicting survival after resection of colorectal liver metastases: Development and multicentre validation study using largest diameter and number of metastases with RAS mutation status. Br. J. Surg. 108(8), 968–975. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjs/znab086 (2021).

Passot, G. et al. Recent advances in chemotherapy and surgery for colorectal liver metastases. Liver cancer 6(1), 72–79. https://doi.org/10.1159/000449349 (2016).

Bhangu, J. S. et al. Circulating free methylated tumor DNA Markers for sensitive assessment of tumor burden and early response monitoring in patients receiving systemic chemotherapy for colorectal cancer liver metastasis. Ann. Surg. 268(5), 894–902. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002901 (2018).

Zhu, X. et al. FBX8 promotes metastatic dormancy of colorectal cancer in liver. Cell Death Dis. 11(8), 622. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-020-02870-7 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the reviewers for their helpful comments on this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhiguo Tang: Research design, data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing; Guojia Zhou: Data analysis; Yu Xu, Zhang Yang: Research design, manuscript revision. Yinxu Zhang: Supervision and verification. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, Z., Zhou, G., Xu, Y. et al. Prognostic model for early-onset colorectal cancer with liver metastasis after primary tumor resection and chemotherapy. Sci Rep 15, 37698 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21410-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21410-x