Abstract

Novel therapies for Wilson disease (WD) will require appropriate biomarkers and clinically relevant endpoints to demonstrate therapeutic efficacy. We aimed to develop robust, minimally invasive biomarker assays to assess target engagement in future clinical trials for WD therapeutics. We conducted a single-center, sample collection biomarker study in 21 patients with WD and 6 control participants. Serum, liver fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNA), and liver core needle biopsy (CNB) samples were collected from participants. RNA and protein were isolated from serum exosome and biopsy samples. Samples were analyzed for mRNA expression by quantitative PCR and for protein expression by a novel electrochemiluminescence (ECL) immunoassay. ATP7B mRNA was detectable in FNA, CNB, and serum exosome samples. However, serum exosomes are not yet a viable method for ATP7B quantification. ATP7B protein was only detectable in CNB samples. We compared the FNA and CNB results for five WD patients and found mRNA expression levels to be comparable with an R2 of 0.64 with statistical significance. The methods we developed may be useful in clinical settings to quantify hepatocyte-specific expression of ATP7B for the development of novel therapeutics for Wilson disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wilson disease (WD) is a rare, monogenic autosomal-recessive disorder, characterized by excess copper accumulation throughout the body1. This disorder arises from inherited biallelic pathogenic variants in the ATP7B gene, which encodes for a P-type ATPase enzyme involved in copper transport and excretion1. In humans, the gene is expressed mainly in the liver, with lower amounts expressed in non-hepatic tissues, including kidney and brain. WD is progressive and if left untreated, may cause chronic liver disease (cirrhosis), neuropsychiatric symptoms, and fatality1,2,3. Typically, diagnosis is made based on clinical findings, such as Kayser-Fleischer rings and neurologic signs, and laboratory measurements of serum copper, urinary copper, and serum ceruloplasmin, the major copper-carrying protein in blood1. Early and accurate diagnosis is essential to ensure that medical interventions can be started before symptoms develop or during early stages of the disease.

Current therapies for WD focus on dietary changes to limit copper intake and lifelong chelation therapies to increase excretion from the body or treatment with zinc salts to inhibit copper absorption. Some patients are refractory to treatment and struggle with medical adherence due to severe side effects4. A liver transplantation is the only life-saving treatment for WD and may also result in neurological improvement in patients with severe neurological symptoms5,6. While current therapies are effective at reducing or stabilizing symptoms, there still remains an unmet need for novel therapies to treat the underlying genetic pathomechanism. Several research studies have highlighted the potential for novel therapeutic strategies for WD7,8, including genetic therapies such as antisense oligonucleotides, or gene and cell-based therapies8,9,10,11. These types of therapies may be able to restore normal copper metabolism but to this date has only been demonstrated in preclinical models.

Biomarkers could significantly contribute to the development and evaluation of these novel therapies. It will be important to define appropriate tests and clinically relevant endpoints that clearly demonstrate therapeutic efficacy. In addition, drug and liver function monitoring for the management of WD could benefit from the development of less-invasive assays and biomarkers. This may also impact diagnostic testing for WD by helping to clarify the pathogenicity of variants of uncertain significance in ATP7B, which will result in a timelier diagnosis and earlier access to treatment12.

The majority of WD patients are compound-heterozygous with two different variants on each ATP7B allele; so far, genotype-phenotype correlations have been difficult to establish13,14,15. Most mutations associated with WD inactivate the copper-transporting function of ATP7B. Protein-truncating mutations cause earlier onset of disease due to decreased protein stability and quantity, while partial preservation of function may be associated with milder phenotypes16. Some missense mutations may also cause early onset of disease. For example, patients who are homozygous for the R778L variant have a younger age of onset due to reduced protein expression, severely impaired copper transport, and protein mislocalization16,17. WD patients with the common H1069Q mutation have a mean onset of symptoms between 20 and 22 years old and several functional studies show that this variant reduces protein expression and stability16,17,18. Quantitative protein assays, such as measurement of extrahepatic ATP7B levels in dried blood spots, may be useful as a first assessment for diagnosis of WD, especially in patients with less common variants or those that are compound-heterozygous and the residual protein expression is unclear19.

We aimed to develop biomarker assays that can robustly detect hepatic ATP7B mRNA and protein for monitoring future ATP7B gene therapies. More specifically, we developed and optimized a quantitative PCR (qPCR) and a novel immunoassay for ATP7B detection in serum exosomes and liver fine needle aspirates (FNA), which we evaluated as safe, less invasive potential alternatives to liver core needle biopsies (CNB)20,21. In this paper, we compare these methods against detection in CNBs using samples collected from participants enrolled at the UHN Hepatology and Liver Transplant Clinic. We show that ATP7B mRNA was detectable in FNA, CNB, and exosome samples, whereas ATP7B protein can only be detected in CNB samples. Significantly, we found positive correlation between mRNA expression in FNA and CNB samples for WD patients, and good correlation of these results to markers of copper metabolism, which suggests that the methods we developed may be useful in the clinic.

Methods

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the UHN Research Ethics Board (CAPCR ID: 21-5756) and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All research was conducted in accordance with both the Declarations of Helsinki and Istanbul.

Study design

This was a single-center, sample collection study at the UHN Liver Clinic at Toronto General Hospital. This study enrolled 27 participants. Fifteen individuals with WD provided only a blood sample (WB01-15). Six additional WD patients provided both a blood sample and liver biopsy samples (WL01-06). None of the patients had liver biopsies performed for diagnosis. Six control participants, who were non-WD patients undergoing liver biopsy for another clinical indication, also provided blood and liver biopsy samples (C01-C06). Every liver biopsy was research and/or clinically required. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in (Supplementary Table 1).

Serum collection

Whole blood was collected by venipuncture using standard medical procedures. A minimum of 22mL of blood was collected in serum separator tubes. Platelet-free serum samples were transferred into conical tubes and placed on ice before processing or storage at −80 °C.

Liver tissue sampling by fine needle aspiration (FNA)

Prior to FNA collection, a liver stiffness measurement was performed as a surrogate for liver fibrosis stage. The liver was identified by ultrasound and the spot for needle insertion was marked. The skin was sterilized and the location was anesthetized by lidocaine injection. A small mandarin containing a 25-gauge spinal needle was punctured in the 6th right intercostal space. After removal of the stylet from the mandarin, a 10mL syringe filled with 0.5mL RPMI medium without phenol red was attached. Intrahepatic cells were aspirated by negative syringe pressure. The needle and syringes were removed from the skin. The needle was flushed with 0.5mL of RPMI to collect the cells into a tube with RPMI on ice. A total of 4 independent passes were performed for each participant and collected into separate tubes. For subsequent passes, the needle was inserted at a 30° angle in adjacent tissue to minimize sampling error. There were no observed complications in these patients after combined biopsies. After sample collection, the volume and colour of each pass was recorded. Each pass was centrifuged at 825 x g for 5 min at 4 °C to remove the supernatant and the volume of each sample was measured again. Samples were stored at -80 °C until processing.

Liver tissue sampling by core needle biopsy (CNB)

Immediately after FNA collection, a routine CNB was collected per institutional collection guidelines. The CNB was performed at the same site of insertion as the FNA. Up to 3 passes were performed and samples were collected into 2mL cryotubes. One pass was used for routine histology and the remaining tissue was snap frozen on dry ice.

Assay development samples

Samples used for method development were purchased from a commercial source (BioIVT, USA), including: primary human hepatocytes (Product# F00995, Lot# NVP), human peripheral blood mononuclear cell (Cat# HUMAN-PBMC-U-190635, Lot# HMN69998), unfiltered frozen human serum from normal healthy individuals (Cat# HUMANSRM2001761, Lot# HMN663734 and Lot# HMN475919), and filtered fresh serum from normal healthy individuals (Cat# HUMANSRM-0110735, Lot# HMN810815).

Exosome RNA isolation

The exosome isolation protocol was performed using the Beckman XPN 80 ultracentrifuge with the SW 40 Ti rotor and miRNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen, Germany). Serum was filtered through a Minisart NML 0.8 μm filter (Sartorius, Germany) and diluted 1:5 with ice-cold PBS. The first round of high-speed ultracentrifugation was performed at 200,000 x g for 2.25 h at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded and exosome pellets were resuspended in 10mL of ice-cold PBS. A second round of high-speed ultracentrifugation was performed at 110,000 RCF for 1.5 h at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded and the pellets were transferred to a new 2mL tube on ice. QIAzol (Qiagen, Germany) was added to the sample pellet at a QIAzol: sample ratio of 5:1. Samples were either immediately processed with the miRNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen, Germany) or stored at -80 °C prior to RNA purification.

Isolation of RNA from FNAs and CNBs

All samples were processed together but FNA passes were processed separately and only one pass from each participant was processed for analysis. RNA was extracted from FNAs using the miRNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen, Germany) using an optimized protocol with a second chloroform extraction step and two additional ethanol washes22. RNA was extracted from CNBs using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany) using an optimized protocol with 50% ethanol. Samples were stored at -80 °C until cDNA synthesis.

qPCR

Reverse transcription was performed with the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, USA) or SuperScript IV Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, USA). Following reverse transcription, qPCR was performed to measure RNA content using the TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, USA) or PrimeTime Gene Expression Master Mix (IDT, USA). The following TaqMan gene expression assays (Applied Biosystems, USA) were used: HS00963534_m1 (ALAS1), Hs00163739_m1 (ATP7B), Hs00169070_m1 (TF), Hs00609411_m1 (ALB), and Hs00237047_m1 (YWHAZ). qPCR amplification was performed using the QuantStudio 5 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA). All qPCR assays were confirmed to have comparable qPCR amplification efficiencies between 90 and 110% using standard curves and all measurements were normalized to hepatocyte-enriched genes rather than tissue mass or total protein content.

Isolation of protein from FNAs and CNBs

All samples were processed together. Protein was extracted from FNAs by adding the appropriate amount of Tris Lysis Buffer (Meso Scale Discovery, USA) to each tube. 100X inhibitors from the Inhibitor pack (Meso Scale Discovery, USA) were added to the lysis buffer to make Complete Tris Lysis Buffer (1µL of protease inhibitor per 100µL of Tris Lysis Buffer). Protein was extracted from CNBs by adding a bead and 500µL of Complete Tris Lysis Buffer to each tube. The samples were homogenized with the TissueLyser at 2 min x 2 min at 25 Hz. Samples were incubated on ice for 30 min and centrifuged at > 10,000 x g for 10 min at 4 °C to clear cellular debris from the lysate. The lysate supernatant was carefully transferred into new tubes, leaving 1–2µL at the bottom.

Electrochemiluminescence (ECL) immunoassay

Anti-ATP7B capture antibody (Abcam, UK, Cat# 131208), anti-ATP7B detection antibody (Novus Biologicals, USA, Cat# NB100-361) and ATP7B recombinant protein (Origene, USA, Cat# TP323635) were purchased from commercial sources.

Anti-ATP7B antibody (Novus Biologicals, USA, Cat# NB100-361) was labeled with MSD SULFO-TAG at 1:20 molar ratio using an MSD SULFO-TAG NHS-Ester kit (Meso Scale Discovery, USA).

The MULTI-ARRAY Standard plate (Meso Scale Discovery, USA) was coated with 35µL of anti-ATP7B capture antibody (Abcam, Cat# 131208) and incubated at 4 °C overnight. The next day, the coating antibody was decanted. The plate was blocked with 0.1% Blocker D-M in PBS-T at room temperature for 1 h with shaking at 700 rpm. After blocking, the blocking solution was decanted and the plate was washed. The plate was run with one set of standards, blanks, quality control samples, and experimental samples in duplicate. These were incubated in the antibody-coated plate at room temperature for 1 h with shaking at 700 rpm. The plate was washed and incubated with 25µL of a sulfo-tagged anti-ATP7B detection antibody at room temperature for 1 h with shaking at 700 rpm. Following a wash step, 150µL 2X Read Buffer Solution (Meso Scale Discovery, USA) was added into each well. The plate was immediately read on the MESO Sector S 600 (Meso Scale Discovery, USA).

Data analysis

For qPCR analysis, average relative expression levels were calculated using the comparative threshold cycle (Ct) method23 and multiple reference gene normalization24 relative to albumin (ALB) and transferrin (TF). To remove outliers, outlier analysis was performed by first excluding each sample and calculating the mean dCt (ATP7B Ct - reference gene Ct) and SD of all other samples. A sample was determined to be a true outlier if the sample was greater than 2 SDs away from the mean dCt of all samples with that sample excluded. Coefficient of variation (CV) analysis and NormFinder25 were used to evaluate each reference gene.

For immunoassay analysis, the conversion of ECL signal units to concentrations was performed using GraphPad Prism 10. The ECL signal vs. concentration relationship was regressed according to a four-parametric logistic regression model with a weighting factor of 1/y2. ATP7B protein concentrations measured by the immunoassay were normalized based on total protein concentrations from BCA protein assays for CNB-based measurements.

Pearson correlation coefficient correlation was used to assess the similarity of FNA vs. CNB results for 5 WD patients. P values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the cohort

In this cohort, sixteen patients had compound heterozygous variants and 5 patients had homozygous variants. Of these variants, 23 were missense, 10 were truncating, 3 were intronic, and 1 was a full gene deletion. Recurrent variants included Asn270Ser, Arg77Leu, Met645Arg, Arg778Ser, and His1069Gln. Genotypes of the WD patients in this study are available in (Table 1). The cohort consisted of 48% females and 52% males with a median age of 34 years (range: 18–66 years). Ethnicities were 56% Asian, 41% White, and 4% Middle Eastern. Liver biopsies were rated by activity grade (0–4), fibrosis stage (0–4), and percent fat. In the WD cohort, the breakdown of activity grades was 50% grade 0 and 50% grade 1; in the control cohort, the activity grades were 83% grade 1 and 17% grade 2. For fibrosis stage scored by the Laennec system, the WD cohort was 17% stage 0, 17% stage 1, 33% stage 3, and 33% stage 4; in the control cohort, the fibrosis stages were 17% stage 0, 17% stage 1, 50% stage 2, and 17% stage 4. Demographic characteristics and liver biopsy features of all participants are available in (Supplementary Table 2). Phenotypes of the WD patients are available in (Supplementary Fig. 1). The cohort was split between those that had only hepatic symptoms (43%) and those that had differing combinations of psychiatric, ocular, hepatic, and neurologic symptoms (48%), while 10% were asymptomatic. All patients have received treatment for WD, including copper chelation agent (90%), zinc supplementation (86%), or low copper diet (76%). Some patients have received multiple treatments. None of these patients have undergone a liver transplant.

Blood sample analysis

ATP7B mRNA in serum exosomes may be detected at low levels in fresh and frozen serum from patients with Wilson disease

After evaluating several approaches to exosome isolation, we found that levels of ATP7B mRNA could only be reliably measured by qPCR from samples isolated using the exoRNeasy kit, which is an affinity spin-column based approach. An optimized ultracentrifugation (UC) method for exosome isolation resulted in serum exosomes with low ATP7B mRNA detection from frozen-thawed healthy control serum and did not give clear improvements over the column-based exoRNeasy method (Supplementary Table 3). qPCR results showed that the Ct difference observed between ATP7B and ALAS1 reflects the differential levels in the liver, where ALAS1 mRNA is expected to be expressed 10X higher than ATP7B mRNA based on internal RNAseq data (Supplementary Table 3). We also determined that hemolysis does not affect serum exosome RNA isolation (Supplementary Table 4).

Blood samples for exosome detection were available from a total of 21 WD patients. Matched fresh and frozen WD patient blood samples were compared to frozen healthy control serum samples. ATP7B mRNA was detected in fresh serum from WD patients but exceeds assay reliability (Ct > 35) in frozen serum from the same participants (Table 2). ATP7B mRNA was detected in frozen control serum after isolation with the column-based and UC methods but exceeded assay reliability with the UC method (Supplementary Table 3). These data suggest that ATP7B mRNA may be detected in serum exosomes by qPCR but patient-to-patient genotypic variability will hamper meaningful cohort analysis. Intra-patient variability may also affect analysis, although multiple serum samples were not collected from the same patient at different time points for assessment. Technical variation during sample preparation and the qPCR assay may also be considerable sources of variability due to the low expression levels of ATP7B mRNA in serum exosomes. For qPCR, Ct values > 33 indicate target quantities approaching a single copy; because of this, variability due to sampling will be large26.

ATP7B mRNA in hepatic tissue from FNAs and CNB

ATP7B mRNA may be detected in hepatic tissue of CNBs and FNAs from WD patients

To determine whether ATP7B mRNA can be detected in CNB and FNA samples, total RNA was extracted and analyzed by qPCR. An initial experiment was conducted to identify appropriate reference genes for each of the sample types (Supplementary Table 5; (Supplementary Figs. 2, 3). 6 WD patients and 6 controls were available for analysis but for the WD patients, only 5 could be used due to a statistical outlier and for the non-WD controls, only 3 could be used due to 3 statistical outliers.

CNB results were analyzed as the average relative expression for each sample. Although we may expect a lower amount of ATP7B mRNA for all WD patient samples compared to control samples, we only observed a decrease in ATP7B mRNA in 4 out of 5 WD samples (WL01, WL02, WL03, and WL05) compared to the controls (Fig. 1a). Participant WL01 has a deletion of the ATP7B gene in one allele and a 4022G > A mutation on the other, resulting in a missense transcript. We measured a 60% overall reduction in mRNA, which is consistent with the loss of mRNA expression from one allele. Participant WL02 has missense mutations in both copies of ATP7B and we observed a 40% reduction in mRNA levels. The first variant in WL03 results in a frameshift and the second allele carries a missense mutation. We observed a 17% decrease in expression in the WL03 CNB. The mutations in WL05 lead to an early stop codon in both alleles, which is expected to lead to a significant reduction in mRNA. We observed a 70% loss of mRNA in the WL05 CNB. WL04 has the M645R mutation, which has been reported to cause exon skipping that results in frameshift and stop-gain8. The second allele in WL04 is the H1069Q mutation that does not affect mRNA levels17. Interestingly, we observed a 44% increase in ATP7B expression in this sample (Fig. 1a). C03, C04, and C05 are similar in relative expression, as expected for control samples from healthy individuals that should not show significant variability in ATP7B mRNA expression. All reference genes were stable in expression, demonstrated by low percentage CV across different control CNB samples (Supplementary Fig. 4).

ATP7B RNA is detectable in hepatocytes in both fine needle aspiration (FNA) and core needle biopsy (CNB) samples. (A) Average relative expression of ATP7B mRNA for each CNB sample was calculated relative to the control samples using TF as the reference gene. (B) Average relative expression of ATP7B mRNA for each FNA sample was calculated relative to the average of control samples using TF as the reference gene. Each bar represents the mean of 3 technical replicates. Each dot represents a single technical replicate.

FNA results were also analyzed as the average relative expression for each sample. The trends in the strength and direction of the ATP7B mRNA expression levels in WL02, WL05, and WL04 FNAs agree with the CNB data (Fig. 1b). We observed a 7% and 45% decrease in expression in WL02 and WL05 FNAs respectively, and a 135% increase in expression in the WL04 FNA. Surprisingly, FNAs WL01 and WL03 however, were not concordant with the matched CNB data and showed an average relative expression above the level of the control samples by 3% and 154%, respectively, which suggests limited consistency. This discrepancy cannot be attributed to variability in the reference gene expression since the Ct values of these genes were quite similar across 3 controls with less than 10% CV (Supplementary Fig. 5).

These data demonstrate that ATP7B mRNA from hepatocytes may be detectable in FNAs and CNBs from WD patients. FNA mRNA expression shows the expected expression decrease in 2 out of 5 WD patients while CNB mRNA expression shows the expected expression decrease in 4 out of 5 WD patients.

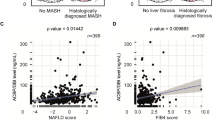

FNAs and CNBs demonstrate comparable levels of ATP7B mRNA

The average relative expression level for each WD patient FNA sample was plotted against the mean relative expression level of its corresponding CNB sample to perform correlation analysis (Fig. 2). There is a positive Pearson correlation with statistical significance (R2 = 0.64, P value = 0.0003) (Fig. 2). These data suggest that FNA may be a viable option as a less invasive biomarker. Given the limited sample size, the observed correlation should be considered with caution. Power analysis of the qPCR data suggests that this study would benefit from a larger sample size (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Ratio of ATP7B mRNA levels in Wilson disease (WD) vs. control samples are correlated in fine needle aspiration biopsies (FNA) and core needle biopsies (CNB). Average relative expression was calculated relative to the mean dCt of control samples for the reference gene TF with 3 technical replicates using the comparative Ct method. R2 is the coefficient of determination (square of the Pearson correlation coefficient r) and p is the P value in the Pearson correlation.

ATP7B protein in hepatic tissue from FNAs and CNB

Development of a novel sensitive immunoassay to detect ATP7B protein in liver biopsy samples

The literature currently lacks description of robust and sensitive methods to measure hepatic ATP7B protein. While liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry methods exist19,27, they are often limited by their time-consuming extraction steps. Moreover, methods that use blood as the sample material may only quantify ATP7B from extra-hepatic sources, such as PBMCs. Here we developed a novel immunoassay for quantifying ATP7B protein using an ECL readout through the MSD platform. This assay met the acceptance criteria of linearity R2 > 0.9 and < 20% CV for intra- and inter-assay precision of the technical replicates.

Several positive controls of varying amounts of human liver lysate demonstrate that the ATP7B immunoassay is quantitative. The lower limit of detection (LLOD) was calculated from the average signal of 2 blanks plus 2.5*SDs, which was 65pg/mL, and the theoretical lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) was calculated from the mean signal from 18 blanks plus 10 SDs, which was 459pg/mL. All positive controls were above the LLOQ, except one control, which was 50 µg of human liver lysate sample (Supplementary Fig. 7). These data demonstrate that the novel ATP7B immunoassay can be used to accurately measure ATP7B protein in CNB samples.

ATP7B protein assay demonstrates the expected decrease in hepatic tissue of CNBs from patients with Wilson disease

We applied this novel immunoassay to the CNB and FNA samples from this study. For most CNB samples, we have measurements of ATP7B protein concentrations above the LLOQ but not all FNA samples were quantifiable (Fig. 3). On average, the WD CNB samples have significantly less ATP7B protein than the control CNB samples and all WD samples were below 4pg/mL of ATP7B per µg of total protein (Fig. 3). CNB samples from WL01 and WL05 showed complete loss of protein, consistent with the genotypes that cause deletion or lead to early stop codons in ATP7B. WL04, which also showed no protein expression, has the M645R mutation, which leads to a loss of protein expression8. The second allele in WL04 is the H1069Q mutation, which reduces ATP7B protein expression and stability17,18. The genotypes of patients WL02 and WL03 consist of missense and frameshift mutations that are expected to lead to a partial reduction in protein levels. Functional studies show that the P840L pathogenic variant in WL02 results in impaired cellular copper transport28 and the N41S pathogenic variant in WL03 is associated with defective trafficking of ATP7B protein in hepatic cells29. We observed a 72% and 54% decrease in ATP7B protein in CNB samples from WL02 and WL03, respectively. These data demonstrate that ATP7B protein from hepatocytes is not quantifiable in FNAs but the assay was able to measure the expected expression decrease in protein levels from CNBs for all WD patient samples.

Comparison to copper metabolism markers

Serum ceruloplasmin and 24-h urinary copper excretion are copper metabolism markers used in the diagnosis of WD. We compared our measurements of relative ATP7B mRNA and ATP7B protein in FNAs and CNBs to these copper metabolism markers in each study participant (Supplementary Fig. 8). When relative hepatic ATP7B mRNA in CNBs was compared to serum ceruloplasmin, we observed a strong, statistically significant positive Pearson correlation (R2 = 0.94, p = 0.006). ATP7B mRNA in CNBs compared to 24-h urinary copper showed a moderate negative correlation (R2 = 0.68) that was not statistically significant (p = 0.08). Similar results were observed with ATP7B mRNA measurements in FNAs; a strong, statistically significant positive correlation between serum ceruloplasmin and ATP7B mRNA in FNAs (R2 = 0.79, p = 0.043) and a strong negative correlation between 24-h urinary copper and ATP7B mRNA in FNAs that was not statistically significant (R2 = 0.76, p = 0.053). No correlation was observed between ATP7B protein measurements in CNBs using the ECL immunoassay when compared to serum ceruloplasmin or 24-h urinary copper.

Discussion

In this study, we explored alternate methods that can be applied to monitor changes in liver ATP7B levels for potential application as biomarkers in clinical trials for novel therapeutic strategies for Wilson disease. We demonstrated the ability to measure ATP7B mRNA in hepatocytes of liver FNAs with positive correlation to the more invasive liver CNBs. For a second approach, we tested whether liver ATP7B mRNA could be detected in circulating RNA, such as those found in serum exosomes. Detection of ATP7B mRNA in exosomes occurred at low levels in freshly collected serum but was not accurately quantifiable in exosomes isolated from frozen WD patient or control serum. In addition to liver ATP7B mRNA detection, we developed a novel immunoassay to detect low levels of ATP7B protein. While ATP7B protein was detected in CNB samples, we were unable to accurately measure ATP7B protein in liver FNAs or serum exosomes.

FNA is a less-invasive alternative to CNB that contains approximately 20,000–50,000 total cells per pass, including 5–10% hepatocytes30. Aspirates from normal liver consist mainly of immune cell populations and hepatocytes, with varying degrees of red blood cell contamination. Endothelial cells, Kupffer cells, and mesothelial cells are also captured31. FNA is quicker, simpler, lower risk, and less costly compared to a CNB. Several studies using endoscopic ultrasound-guided FNA of liver lesions or masses have reported complications in 0–4% of cases21,32. Two of these studies reported complications in 0/7721,33 and 0/47 patients32. This is contrasted to CNBs, which have been reported to result in 84% pain, 0-5.3% significant haemorrhage, and up to 0.3% mortality34. FNA requires only local anesthesia and serious adverse events are rare. Because of this, repeat sampling can be done in the same patient in the same area. Several studies have used FNA for longitudinal hepatic sampling during antiviral therapy with minor to no procedure-related complications35,36,37,38,39. FNAs also have an advantage over serum exosomes as the method provides a direct measurement of ATP7B from hepatic cells.

Numerous studies have compared FNA to CNB as a biopsy technique for hepatic lesions, with varying results40,41,42. To date, detection of liver hepatocytes from FNA has not been widely studied given the low levels of hepatocytes typically found in liver FNA samples39,43,44,45. Here, we demonstrate hepatocyte detection in liver FNAs through the presence of albumin and transferrin mRNAs. The detection of liver ATP7B mRNA from hepatocytes within FNA samples showed significant correlation between FNAs and CNBs. We propose that monitoring of levels of hepatocyte-expressed genes in FNAs holds promise and can be employed in a clinical setting if subjected to specific criteria. For example, serial FNAs are more easily performed than serial CNBs and could rapidly assess whether a therapy designed to increase ATP7B mRNA expression is being dosed at a therapeutic level. While measuring ATP7B from FNA samples shows promise, our current protocols do not allow FNA to serve as a reliable stand-alone substitute for CNBs without another method to accurately quantify hepatocyte content in each sample. A limitation of our study is that an accurate cell number for each sample could not be determined, which means that the variability of the FNAs may be due to a low number of hepatic cells. Introduction of additional quality controls for FNA samples prior to analysis would mitigate inaccurate measurements due to variability in hepatocyte counts. For example, testing for blood and fat in FNA samples or depleting immune cells via immunomagnetic cell separation could ensure hepatocyte-specific detection. Alternatively, normalization of measurements to hepatocyte counts could be done by quantifying hepatocytes through methods such as flow cytometry. Hepatic copper quantification may also be used for hepatocyte content estimation but is likely more appropriate for CNB samples during validation studies rather than as a routine quality control step during clinical monitoring with FNA samples due to minimal material recovery, potential copper depletion after chelation therapy, and complex sample handling. Although there were some inconsistencies in the relative expression levels of matched FNA and CNB samples, we suspect that this may be due to the overall low expression levels of ATP7B and that this method may be more valid for investigations of a more highly expressed target.

Exosomes are small membrane-encapsulated nanoparticles approximately 30–200 nm in diameter that are released into biological fluids (including serum, saliva, and urine) by many different cell types, including hepatocytes46. Exosomes contain multiple macromolecules, such as proteins and mRNA. More recently, exosomes have been used for detection of biomarkers for diagnosis and therapeutic development in various liver diseases20,47,48,49. Developing a method to monitor changes in ATP7B mRNA due to an expression augmenting therapeutic would be difficult without performing serial liver tissue collections, which would not be suitable in clinical studies. A blood-based measurement would be the least invasive method to measure RNA and protein but would only serve as an indirect method of quantitation. The lack of cell-of-origin markers on exosomes is a key challenge and the relative contribution of hepatic ATP7B to the pool of serum exosomes cannot currently be determined. We have shown that a column affinity-based approach can yield comparable results to a standard ultracentrifugation protocol, offering a more efficient isolation method that may be more amenable to a clinical setting. While we were able to detect levels of ATP7B mRNA from serum exosomes in the WD patient samples, detection was not consistent. Therefore, serum exosome analysis for ATP7B quantification is not yet a viable method. However, our methods may be further optimized and used to monitor mRNA and protein levels from more highly expressed gene targets. This would allow for longitudinal monitoring of target expression changes over the duration of a trial period.

Abnormalities in copper metabolism are often the first stage of WD diagnosis with 24-h urinary copper excretion and serum ceruloplasmin being the two biochemical markers used, according to current AASLD and EASL guidelines50,51. While the methodologies described here were designed to measure liver ATP7B and were not intended to replace genetic or biochemical diagnosis of WD, we compared our assay results to these copper metabolism markers in the study participants. ATP7B mRNA measured in liver FNA and CNB samples showed strong positive correlation with serum ceruloplasmin, which further supports our findings. The negative correlation with 24-h urinary copper excretion was good but not statistically significant, likely due to the patients having received treatment. Due to the small sample size, the strength of the observed correlations should be viewed cautiously. Nonetheless, these results suggest that ATP7B mRNA measurements from CNB and the less-invasive FNA may hold potential for diagnostic use after further validation using larger numbers of positive and negative samples. The results from our ECL immunoassay did not correlate with the copper metabolism markers, underscoring the need to further develop the method for increased sensitivity and accuracy. Significant progress has been made in the field to develop novel minimal- to non-invasive diagnostic tools for WD by measuring ATP7B protein. Collins et al. introduced a method to detect ATP7B peptides from dried blood spots, enabling potential use in newborn diagnostic screening19. Their method removes the need for large blood samples and allows for rapid, sensitive measurement of ATP7B in a way that is unaffected by variability in hepatic ATP7B. In contrast, our study focuses on quantifying hepatic ATP7B levels, which may be obscured in whole blood analyses, where ATP7B detection is thought to largely originate from PBMCs or other blood cells. Currently, our assays are more applicable to gene therapy monitoring where changes in ATP7B may not apply to, or may not be detected in extrahepatic scenarios.

Our results demonstrate that measurements of ATP7B mRNA and ATP7B protein are possible in small samples, however, assay interpretation may be affected by the mutation-specific variability in ATP7B expression. For example, missense mutations such as the common H1069Q variant may preserve mRNA expression while drastically reducing protein function. In other cases, such as the M645R variant, predicted nonsense-mediated decay may result in reduction of both mRNA and protein expression8. Understanding the functional consequences of the ATP7B variants in patient samples is valuable for the interpretation of the assay results for use in biomarker readouts. For this reason, we propose having a baseline measurement when applying these assays for clinical use, which can be done with serial FNA measurements to track changes over time. RNA from an FNA as a biomarker may be important for gene therapy monitoring if the mechanism of the therapy depends on RNA expression or if the variant influences RNA expression. Protein from a CNB as a biomarker may be best suited for diagnosis if the variant has an effect on protein expression. These RNA and protein monitoring assays will only be useful if they are performed alongside genetic testing to confirm the mechanism of a specific clinical variant.

The ability to measure and quantify ATP7B in patients using a minimally invasive method would ease the burden on patients and streamline the development of genetic therapies, cell therapies, and targeted molecular therapies. Two adeno-associated virus-based gene therapies for WD (VTX-801 and UX701) are currently being evaluated in clinical trials (NCT04537377, NCT04884815). The main endpoints for these studies are measurements of serum and urinary copper, as well as serum ceruloplasmin (concentration and activity). ATP7B RNA and ATP7B protein quantification readouts may be useful as additional endpoint evaluations, especially for future therapeutics that may aim to increase the quantity of functional ATP7B protein. An mRNA readout may demonstrate the mechanism of the therapy as well. Since the UX701 study also includes a measurement of liver copper concentration from a liver biopsy sample, including these assays would not be an additional burden to the patients. Circulating serum exosomes and fine needle aspirates are two potentially less invasive methods that may be used to evaluate both ATP7B RNA and ATP7B protein.

Further validation is required to assess the precision and reproducibility of our methods. A larger patient-matched FNA and CNB sample size would allow for more definitive conclusions on consistency of the results, as suggested by power analyses. Although measurements at diagnosis could not be included in this study, future studies should consider recruiting participants at diagnosis and comparing the phenotypes at multiple disease stages. In addition, comparisons of samples at baseline and post-treatment with an ATP7B gene therapy would be important to validate the use of these assays for clinical trials. This could be done in humanized mouse models where the gene therapy is delivered and serial FNA and CNB samples are collected. Since this is a pilot study and the methods are not yet ready for diagnostic purposes, a positive predictive value and negative predictive value were not determined. If our methods are successfully validated, the diagnostic utility of these assays will likely only be complementary to the existing primary diagnostic methods, in cases where diagnosis may be more difficult and genetic analysis was performed.

In summary, we developed methods for detection of liver ATP7B mRNA and ATP7B protein that may be applicable to clinical settings. The mRNA and protein readouts from the CNBs in this study matched the expected functional results from genetic diagnosis, emphasizing the prospect of the assays developed in this study for ATP7B detection. The results from the CNB samples demonstrate the efficacy of our qPCR and immunoassays to measure ATP7B levels in patient samples. The significant positive correlation between FNA and CNB ATP7B mRNA expression is promising but should be interpreted with caution given the small cohort size and power limitations. While CNBs will remain the standard material for measuring liver mRNA and protein, this study demonstrates the potential for using less invasive measures, such as serum exosomes and FNAs, to measure hepatocyte-specific genes.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

Abbreviations

- ATP7B:

-

ATPase copper transporting beta

- CNB:

-

Core needle biopsy

- Ct:

-

Threshold cycle

- CV:

-

Coefficient of variation

- ECL:

-

Electrochemiluminescence

- FNA:

-

Fine needle aspiration

- MSD:

-

Meso scale discovery

- PBMC:

-

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- qPCR:

-

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- RPMI:

-

Roswell park memorial institute

- UC:

-

Ultracentrifugation

- UHN:

-

University health network

- WD:

-

Wilson disease

References

Poujois, A. & Woimant, F. Wilson’s disease: A 2017 update. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 42, 512–520 (2018).

Ala, A., Walker, A. P., Ashkan, K., Dooley, J. S. & Schilsky, M. L. Wilson’s disease. Lancet 369, 397–408 (2007).

Gitlin, J. D. Wilson disease. Gastroenterology 125, 1868–1877 (2003).

Appenzeller-Herzog, C. et al. Comparative effectiveness of common therapies for Wilson disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled studies. Liver Int. 39, 2136–2152 (2019).

Turgut, E., Aydin, C., Kayaalp, C. & Yilmaz, S. Liver transplantation in wilson’s disease: A systematic review. Ann. Liver Transpl. 1, 113–122 (2021).

Litwin, T. et al. Liver transplantation as a treatment for wilson’s disease with neurological presentation: a systematic literature review. Acta Neurol. Belg. 122, 505–518 (2022).

Moini, M., To, U. & Schilsky, M. L. Recent advances in Wilson disease. Transl Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 6, 21 (2021).

Merico, D. et al. ATP7B variant c.1934T > G p.Met645Arg causes Wilson disease by promoting exon 6 skipping. NPJ Genom Med. 5, 16 (2020).

Cai, H., Cheng, X. & Wang, X. P. ATP7B gene therapy of autologous reprogrammed hepatocytes alleviates copper accumulation in a mouse model of wilson’s disease. Hepatology 76, 1046–1057 (2022).

Tang, S., Bai, L., Duan, Z. & Zheng, S. Stem cells treatment for Wilson disease. Curr. Stem Cell. Res. Ther. 17, 712–719 (2022).

Wilson Disease Association. Gene Therapy. Wilson Disease Association. https://wilsondisease.org/living-with-wilson-disease/treatment/genetic-therapies/ (accessed 17 Jan 2025).

Dusek, P., Litwin, T. & Członkowska, A. Neurologic impairment in Wilson disease. Ann. Transl Med. 7, S64 (2019).

Leggio, L., Addolorato, G., Loudianos, G., Abenavoli, L. & Gasbarrini, G. Genotype-phenotype correlation of the Wilson disease ATP7B gene. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 140, 933 (2006).

Wallace, D. F. & Dooley, J. S. ATP7B variant penetrance explains differences between genetic and clinical prevalence estimates for Wilson disease. Hum. Genet. 139, 1065–1075 (2020).

Ovchinnikova, E. V., Garbuz, M. M., Ovchinnikova, A. A. & Kumeiko, V. V. Epidemiology of wilson’s disease and pathogenic variants of the ATP7B gene leading to diversified protein disfunctions. Int J. Mol. Sci 25, (2024).

Chang, I. J. & Hahn, S. H. Chapter 3 - The genetics of Wilson disease. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology (eds. Członkowska, A. & Schilsky, M. L.) vol. 142 19–34 (Elsevier, 2017).

van den Berghe, P. V. E. et al. Reduced expression of ATP7B affected by Wilson disease-causing mutations is rescued by Pharmacological folding chaperones 4-phenylbutyrate and Curcumin. Hepatology 50, 1783–1795 (2009).

Huster, D. et al. Defective cellular localization of mutant ATP7B in wilson’s disease patients and hepatoma cell lines. Gastroenterology 124, 335–345 (2003).

Collins, C. J. et al. Direct measurement of ATP7B peptides is highly effective in the diagnosis of Wilson disease. Gastroenterology 160, 2367–2382e1 (2021).

Sung, S., Kim, J. & Jung, Y. Liver-Derived exosomes and their implications in liver pathobiology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, (2018).

DeWitt, J. et al. Endoscopic ultrasound–guided fine needle aspiration cytology of solid liver lesions: A large single-center experience. Off. J. Am. College Gastroenterol. ACG 98, 2003. (1976).

Toni, L. S. et al. Optimization of phenol-chloroform RNA extraction. MethodsX 5, 599–608 (2018).

Schmittgen, T. D. & Livak, K. J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat. Protoc. 3, 1101–1108 (2008).

Hellemans, J., Mortier, G., De Paepe, A., Speleman, F. & Vandesompele, J. qBase relative quantification framework and software for management and automated analysis of real-time quantitative PCR data. Genome Biol. 8, R19 (2007).

Andersen, C. L., Jensen, J. L. & Ørntoft, T. F. Normalization of real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR data: a model-based variance Estimation approach to identify genes suited for normalization, applied to bladder and colon cancer data sets. Cancer Res. 64, 5245–5250 (2004).

Ruiz-Villalba, A., Ruijter, J. M. & van den Hoff, M. J. B. Use and misuse of Cq in qPCR data analysis and reporting. Life 11, (2021).

Jung, S. et al. Quantification of ATP7B protein in dried blood spots by peptide Immuno-SRM as a potential screen for wilson’s disease. J. Proteome Res. 16, 862–871 (2017).

Huster, D. et al. Diverse functional properties of Wilson disease ATP7B variants. Gastroenterology 142, 947–956e5 (2012).

Braiterman, L. et al. Apical targeting and golgi retention signals reside within a 9-amino acid sequence in the copper-ATPase, ATP7B. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 296, G433–G444 (2009).

Boettler, T. et al. Assessing immunological and virological responses in the liver: implications for the cure of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. JHEP Rep. 4, 100480 (2022).

Chhieng, D. C. Fine needle aspiration biopsy of liver - an update. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2, 5 (2004).

Oh, D. et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration can target right liver mass. Endosc Ultrasound. 6, 109–115 (2017).

Musonda, T. et al. New window into hepatitis B in africa: liver sampling combined with single cell omics enables deep and longitudinal assessment of intrahepatic immunity in Zambia. J. Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiae054 (2024).

Eisenberg, E. et al. Prevalence and characteristics of pain induced by percutaneous liver biopsy. Anesth. Analg. 96, 1392–1396 (2003).

Tjwa, E. T. T. L. et al. Similar frequencies, phenotype and activation status of intrahepatic NK cells in chronic HBV patients after long-term treatment with Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF). Antiviral Res. 132, 70–75 (2016).

Spaan, M., van Oord, G. W., Janssen, H. L. A., de Knegt, R. J. & Boonstra, A. Longitudinal analysis of peripheral and intrahepatic NK cells in chronic HCV patients during antiviral therapy. Antiviral Res. 123, 86–92 (2015).

Claassen, M. A. A., de Knegt, R. J., Janssen, H. L. A. & Boonstra, A. Retention of CD4 + CD25 + FoxP3 + regulatory T cells in the liver after therapy-induced hepatitis C virus eradication in humans. J. Virol. 85, 5323–5330 (2011).

Genshaft, A. S. et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing of liver fine-needle aspirates captures immune diversity in the blood and liver in chronic hepatitis B patients. Hepatology 78, 1525–1541 (2023).

Nkongolo, S. et al. Longitudinal liver sampling in patients with chronic hepatitis B starting antiviral therapy reveals hepatotoxic CD8 + T cells. J. Clin. Invest. 133, (2023).

Huang, S. C. et al. Direct comparison of biopsy techniques for hepatic malignancies. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 27, 305–312 (2021).

Suo, L., Chang, R., Padmanabhan, V. & Jain, S. For diagnosis of liver masses, fine-needle aspiration versus needle core biopsy: which is better? J. Am. Soc. Cytopathol. 7, 46–49 (2018).

Goldhoff, P. E., Vohra, P., Kolli, K. P. & Ljung, B. M. Fine-Needle aspiration biopsy of liver lesions yields higher tumor fraction for molecular studies: A direct comparison with concurrent core needle biopsy. J. Natl. Compr. Canc Netw. 17, 1075–1081 (2019).

Gill, U. S. et al. Fine needle aspirates comprehensively sample intrahepatic immunity. Gut 68, 1493–1503 (2019).

Kim, S. C. et al. Efficacy of antiviral therapy and host–virus interactions visualised using serial liver sampling with fine-needle aspirates. JHEP Rep. 5, 100817 (2023).

Testoni, B. et al. Evaluation of the HBV liver reservoir with fine needle aspirates. JHEP Rep. 5, 100841 (2023).

Pegtel, D. M., Gould, S. J. & Exosomes Annu. Rev. Biochem. 88, 487–514 (2019).

Nakao, Y. et al. Circulating extracellular vesicles are a biomarker for NAFLD resolution and response to weight loss surgery. Nanomedicine 36, 102430 (2021).

Taylor, D. D. & Gercel-Taylor, C. The origin, function, and diagnostic potential of RNA within extracellular vesicles present in human biological fluids. Front. Genet. 4, 142 (2013).

Szabo, G. & Momen-Heravi, F. Extracellular vesicles in liver disease and potential as biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 14, 455–466 (2017).

Alkhouri, N., Gonzalez-Peralta, R. P. & Medici, V. Wilson disease: a summary of the updated AASLD practice guidance. Hepatol. Commun. 7, e1050 (2023).

European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL-ERN clinical practice guidelines on wilson’s disease. J. Hepatol. 82, 690–728 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Doinita Vladutu and Ahreni Saunthar for serum processing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.J.J., L.C., and K.C-O. wrote the manuscript text, conducted the experiments, and developed the methodology. R.J.J. and L.C. validated the reproducibility of the results. R.J.J., L.C., and K.A. prepared the figures. K.A. and D.P.M.L. managed and coordinated the study. R.J.J., B.F., and E.M.H. performed statistical and computational data analysis. L.R., A.J.G., and J.J.F. reviewed the data. J.F.F. conceptualized the study. L.R., J.F.F. and K.C-O. supervised research activity planning and execution. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Funding: Research support was provided by Deep Genomics. Employment: R.J.J, L.C., K.A., B.F., E.M.H, L.R., and K.C-O. are or were employees of Deep Genomics. D.P.M.L., A.J.G., and J.J.F. have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, R.J., Chen, L., Amburgey, K. et al. Novel and less invasive biomarker assays to measure liver ATP7B in Wilson disease patients. Sci Rep 15, 37720 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21455-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21455-y