Abstract

As incarcerated individuals age, prison systems often struggle to provide appropriate long-term care. Compassionate release policies can address this gap by allowing seriously ill or aging individuals to transition to community-based care. Many nursing homes, however, are reluctant to admit individuals recently released from prison. This study examined how incarceration status affects nursing home admission decisions.

Using a statewide secret shopper methodology, researchers contacted all 74 licensed nursing homes in Rhode Island. Callers first inquired about bed availability for a standardized model patient, then disclosed the patient would be arriving from prison under compassionate release. Responses before and after disclosure were categorized and analyzed using ordinal regression.

Of 74 facilities, 61 (82.4%) were reached. Before disclosure, 52.5% reported bed availability within one month; this dropped to 26.2% after incarceration was mentioned. Complete rejections increased from 9.8 to 44.3%. Facilities were 3.41 times more likely to downgrade admission status after disclosure (OR = 3.41; 95% CI: 1.76–6.70; p < 0.001). For patients with serious criminal offenses, the rejection rate reached 70.5%, and the odds of rejection increased to 11.39 (95% CI: 5.48–24.65; p < 0.0001). Facility size was not associated with rejection likelihood.

Incarceration and criminal history significantly reduce access to nursing home care, even when medical need and payment ability are constant. These findings highlight the need for policy and system-level interventions to reduce stigma and increase care access for aging individuals eligible for compassionate release.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The aging prison population in the United States presents significant public health and social challenges. Between 1991 and 2021, the number of incarcerated individuals aged 55 and older increased by nearly 400%1. Persons incarcerated in correctional facilities often experience “accelerated aging,” whereby pre-incarceration and carceral-setting factors drive expedited cellular senescence and thus, geriatric conditions such as dementia, functional impairments, and chronic illnesses arrive significantly earlier in the lifecourse than in the general population2,3. These health challenges are further exacerbated by the prison environment, which is ill-suited to facilitate appropriate geriatric care4.

Compassionate release policies, including medical and geriatric parole, can address these challenges by enabling seriously ill or aging incarcerated individuals to transition to community-based care settings, including (but not limited to) nursing homes, hospice facilities, and private residences5.

Originally introduced as federal law in 1984, “compassionate release” allowed the Director of the Bureu of Prisons to immediately release an incarcerated individual in circumstances deemed “extraordinary and compelling.” This language was narrowly interpreted to include only terminally ill individuals until the federal US Sentencing Commission defined criteria in 2007 that extraordinary and compelling may include: “(1) terminal illness, (2) debilitating physical conditions that prevent inmate self-care, and (3) death or incapacitation of the only family member able to care for a minor child.”6 Almost all state systems have a similar compassionate or medical release program7. As the average age in prison has increased, these mechanisms often serve to address the needs of this population. For example, in 2021 Rhode Island introduce “geriatric parole” for “humanitarian reasons and to alleviate exorbitant expenses associated with the cost of aging, for inmates whose advanced age reduces the risk that they pose to the public safety.”8.

Compassionate release policies strive to balance public safety with the humane treatment of incarcerated individuals, allowing those deemed to pose minimal risk to receive appropriate care. Despite these intentions, only about 3.24% of compassionate release applications in federal prisons were granted from 2013 to 2014, and even when granted, significant barriers remain in placing individuals in community resources5,9. Between 2013 and 2015, only 13.5% of persons eligible for compassionate release were discharged from state departments of corrections10.

While navigating long-term care admission is difficult for many, persons with a history of criminal legal system involvement also face stigma and unique logistical challenges when seeking community care. Nursing homes and other long-term care facilities are often unwilling to accept these individuals due to concerns about safety11,12. This issue is exemplified by the Rhode Island Department of Corrections, where there have been cases of individuals granted compassionate release through medical parole who have remained incarcerated because no community facility is available or willing to accept them. Consequently, these seriously ill individuals remain behind bars despite being assessed as posing no substantial public safety risks by the Parole Board. This gap in community resources undermines the goals of compassionate release statutes, leaving aging and ill incarcerated individuals to languish in prison settings unequipped for their needs4.

This significant public health problem affects multiple state departments of corrections, though lacks characterization in existing literature. Addressing this research gap is essential to meet the urgent need for impact-oriented policy and legislation to facilitate better health outcomes for these individuals. The lack of available community resources for incarcerated persons can severely limit new and existing “compassionate release” programs designed to support aging and seriously ill patients behind bars.

To address this gap, we conducted a study investigating the availability and acceptance of nursing home placement for patients granted compassionate release compared to community-dwelling patients. Using a secret shopper methodology, we aimed to assess disparities in access and identify perceptions of incarceration as a barrier to nursing home admission.

Methods

Study design and participants

Secret shopper studies, also known as audit studies, have proven effective in highlighting inequities and assessing access in healthcare research13. The research team conducted a state-wide survey of all 74 nursing homes in Rhode Island (RI) identified via the RI Department of Health’s “Nursing Home Summary Report”14. A researcher called every facility, presenting themself as a family member seeking long term nursing care for a relative (i.e. the patient). With help from an expert advisory panel (a licensed nursing home administrator, social worker, and compassionate release researcher), the research team developed a standardized “model” patient profile that would likely qualify for long-term nursing home care. This patient profile was a 78-year-old male with a medical history significant for insulin-dependent diabetes, a mild oxygen requirement for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, poor eyesight, a recent fall history, and the ability to pay for nursing home care privately for 1 year.

All nursing facilities were contacted using a standardized call script (Supplement 1) to determine whether a facility had current bed availability, a waitlist (and its length), or no availability for prospective patients. After establishing an initial response, the caller disclosed that the patient would be coming from the RI Adult Correctional Institution (ACI) on compassionate release and asked how that may affect admissions. Any changes in responses were documented. The caller then asked whether any specific offenses would be problematic for the nursing facility. After inquiring about and documenting any changes in facility bed availability after disclosing the patient’s incarceration status, the call script elicited admissions coordinators’ perceived barriers to admitting incarcerated patients.

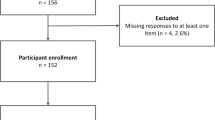

If a nursing facility’s admission coordinator was unable to be contacted (e.g., out of office or call went to voicemail), no voicemails were left and the researcher called back on a different day. Up to 5 attempts were made to contact every facility. After the fifth attempt, the facility was excluded from the study. Following completion of the study, a debrief letter was sent to every nursing facility that had been contacted. The debrief letter explained the facility’s anonymous involvement in this study, provided a point of contact for any further inquiries, and offered the opportunity for the facility to opt out of the study.

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations for secret shopper studies. The Lifespan/Brown University Health Institutional Review Board approved a waiver of informed consent, as it is part of the secret shopper study methodology. Because this was a secret shopper study, participants were initially unaware of their involvement; however, they were notified after the interaction and given the opportunity to opt out of inclusion in the research. This study received approval from the Lifespan/Brown University Health Institutional Review Board.

Measures

The primary outcome of this study was the response of nursing home intake coordinators regarding bed availability before and after disclosing the patient’s incarceration status. Responses were classified as “Available,” “Waitlist < 1 month,” “Waitlist > 1 month,” and “Reject.” Per this project’s expert panel, the industry often utilizes longer waitlists to softly reject prospective residents. Therefore, a waitlist > 1 month was classified as a “soft rejection” for data analysis purposes.

Secondary outcomes included whether nursing home staff identified specific criminal offenses that would hinder admission and their perceived barriers to accepting individuals from the ACI. These data were captured during the secret shopper calls, specifically during the portion of the script that followed disclosure of the patient’s incarceration history. If a facility respondent indicated that certain offenses would disqualify a patient from admission, the response was recorded and qualitatively coded. Offenses described by staff as prohibitive were grouped under the category of “serious offenses,” which included violent crimes, sexual assault, breaking and entering, and drug-related offenses.

Each call was recorded into a REDCap server that collected Facility Name, Time and Date of Call, Outcomes, and Notes. Notes were utilized to guide future calls, record any aberrancy in routine calls, or document other pertinent information. Calls were kept brief to minimize operational disruptions.

Statistical analysis

Prior to exporting the data from REDCap for statistical analysis, the data was de-identified. This study utilized a pre-post study design to assess changes in nursing home acceptance before and after disclosure of incarceration status. An ordinal regression model was performed to assess differences in responses before and after mentioning incarceration and compassionate release. A second logistic regression model was constructed to evaluate whether facility size was associated with nursing home acceptance status and to assess whether it confounded the relationship between incarceration status and rejection. Facility size was treated as a continuous variable, defined by the total number of certified beds per facility.

Results

Of 74 nursing homes in the initial sample, 82.43% (n = 61) were successfully contacted for information regarding bed availability and the impact of incarceration (Table 1). After receiving the debrief letter, no facilities opted out from the study, and 2 facilities inquired about how they had answered. Initially, 29.5% (n = 18) endorsed immediate bed availability, 23% (n = 14) had a waitlist less than 1 month, 37.7% (n = 23) had a waitlist greater than 1 month, and 9.8% (n = 6) rejected the prospective patient (Table 2). By combining the “immediate bed availability” and “waitlist < 1 month” categories, 52.5% (n = 32) of facilities were classified as having initial bed availability within 1 month. Likewise, by combining the “reject” and “waitlist > 1 month” categories, 47.5% (n = 29) of facilities were classified as having no availability (Table 3, Fig. 1).

Facility responses for availability significantly changed after mentioning the incarceration status of the patient. The percent of facilities that endorsed availability within a month decreased by half from 52.5% (n = 32) to 26.2% (n = 16) when incarceration and compassionate release status was mentioned (See Table 2). The percent of facilities that rejected the prospective patient increased 4.5 times from 9.8% (n = 6) to 44.3% (n = 27) with incarceration mentioned (Table 2). Likewise, the percentage of facilities with no availability (reject combined with waitlist > 1 month), increased 1.5 times from 47.5% (n = 29) to 73.8% (n = 45) (Table 3).

Using an ordinal regression model, facilities were 3.41 times more likely (95% CI: 1.76–6.70, p < 0.001) to move a prospective patient to a more restrictive acceptance category (i.e., longer wait times or outright rejection) when their history of incarceration was disclosed (Table 4). Additionally, 41% (n = 25) of facilities said incarceration status might impact admissions without explicitly rejecting the patient or changing their initial response about availability.

To assess whether differences in facility size could account for disparities in acceptance, we incorporated facility size as a covariate in an adjusted ordinal regression model (Table 4). Facility size (i.e., number of nursing beds) was not significantly associated with acceptance outcomes (OR = 0.99, 95% CI: 0.99–1.00, p = 0.101), and did not attenuate the association between incarceration status and nursing home rejection.

For violent offenses and other serious crimes (e.g., sexual offenses, drug-related offenses, breaking and entering), facility responses for availability changed more significantly. The percent of facilities that rejected the prospective patient increased from 9.83% (n = 6) to 70.5% (n = 43) if there was a history of a serious offense (Table 2). Similarly, the percent of facilities that had no availability (reject + waitlist > 1 month) increased from 47.5% (n = 29) to 88.5% (n = 54) for violent offenses and other serious crimes (Table 3). Based on the ordinal regression model, facilities were 11.39 times more likely (95% CI: 5.48–24.65, p < 0.0001) to move a prospective patient to a more restrictive acceptance category when a history of a serious offense was disclosed (Table 3).

Nearly 40% of facilities explicitly mentioned violent offenses as prohibitive for nursing home admissions (37.7% (n = 23). Sexual assault was mentioned by 24.6% (n = 15) of facilities as prohibitive for admission, and 19.7% (n = 12) stated any criminal offense would prohibit facility admissions (Table 4).

When admissions coordinators were asked about their perceived barriers for accepting an incarcerated patient to a nursing facility, 44.3% (n = 27) cited safety as a concern, 13.1% (n = 8) expressed concern about an inability to meet patient needs or the complexity of the patient, 13.1% (n = 8) cited behavioral and psychiatric problems as barriers for admissions, and 24.6% (n = 15) cited incarceration in and of itself or a specific policy against incarceration as a barrier for admissions (See Table 6).

Discussion

This study sought to explore the impact of incarceration and compassionate release status on the availability of nursing home placement, and the associated perceived barriers to admissions. At baseline, the majority of RI nursing homes reported bed availability within 1 month. A significant group of facilities did have long waitlists, suggesting that long-term nursing care is a limited resource for any person coming from the community. However, while a substantial number of admissions coordinators endorsed extended waitlists longer than 1 month, very few nursing facilities outright rejected patients during the initial survey of bed availability.

The disclosure of incarceration and compassionate release status dramatically influenced the possibility of nursing home placement, with many admissions coordinators changing their responses to rejection. After discovering the incarceration status of the prospective patient, bed availability within 1 month was cut in half. Furthermore, a large number of facilities (41%) stated that incarceration may impact admissions but did not deliver a definitive answer. As a result, our results are likely conservative estimate. Only 4 facilities (6.6% of all nursing homes) endorsed bed availability within 1 month without qualifying that incarceration might impact admissions. In summary, while some nursing homes were willing to consider compassionate release patients for admission, most facilities either rejected incarcerated patients despite existing bed availability or expressed concern about incarceration status without explicit rejection.

Violent offenses and other serious crimes had a particularly pronounced impact on nursing home admissions, with facilities more likely to deny admissions to those with serious offenses on their criminal record. The bulk of admissions coordinators explicitly stated they would not accept an incarcerated patient with a “serious offense” on their record for nursing home admissions, and nearly 90% of nursing homes in RI were unavailable to incarcerated patients with a “serious offense” on their record.

Many people eligible for medical parole many have had long incarcerations. As most incarcerated persons in RI who are serving sentences greater than 10 years have committed violent or other serious crimes, these data suggest that nursing home placement is virtually non-existent for most compassionate release candidates15. Thus, the population most eligible for compassionate release may also be the population least likely to be accepted by nursing homes.

Specific concerns regarding patient safety, care complexity, and institutional policies were commonly cited by admissions coordinators as barriers to accepting individuals granted compassionate release. Notably, multiple respondents described the patient as “too complex,” despite the standardized model profile having relatively low medical acuity. Nearly a quarter of facilities explicitly cited incarceration itself as the primary barrier to admission, suggesting that criminal legal history—not clinical need—often drove exclusion.

These concerns may reflect stigma more than evidence. Compassionate release is often contingent on a thorough review by parole boards, which explicitly assess public safety risk prior to approval. Moreover, empirical data demonstrate that individuals over the age of 55 have extremely low recidivism rates of 0.2–0.4%16.

Despite the evidence of decreased recidivism among older incarcerated people, admission coordinators’ responses regarding safety, complex patient needs, and behavioral challenges highlight that nursing homes may feel ill-equipped to care for patients with a history of incarceration. Resident-to-resident and resident-to-staff physical violence are both known entities in nursing homes. However, neither have been systematically correlated with prior criminal offenses and are, instead, associated with cognitive impairment among residents and staffing constraints17,18,19. This further highlights how criminal legal stigma may be influencing health decision-making.

Criminal legal stigma has been repeatedly demonstrated to negatively impact the housing and health of justice-involved individuals’ post-incarceration20,21.

As it stands, incarcerated persons are not explicitly protected under the Fair Housing Act, allowing for a history of incarceration to remain a legal and legitimate reason for a housing provider to reject an applicant22. Provided that the FHA has been shown to apply to nursing homes23,24, nursing facilities can selectively exercise bias and reject applicants due to their incarceration status. However, since incarcerated people are disproportionately members of racial and ethnic classes that are protected under the FHA, the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development issued a 2016 guidance on the “Application of Fair Housing Act Standards to the Use of Criminal Records.” This guidance clarifies that, while a nursing home, for example, may reasonably consider criminal legal involvement as a factor for denying admission if it aligns with the facility’s interests and needs, generalized or arbitrary criminal history-based restrictions are likely to discriminate against protected groups, thereby potentially violating the FHA22. As such, the FHA may offer a potential pathway to challenge blanket exclusions based on incarceration, particularly when such practices disproportionately impact marginalized groups protected by the FHA.

Admissions coordinators’ perceived barriers to accepting a compassionate release patient may stem from the cost-benefit analysis that must be conducted on every prospective admission. Since insufficient Medicaid reimbursements often force nursing homes to operate on thin or negative margins, nursing facilities must always consider if the resource utilization from accepting and caring for a patient is worth the reimbursement25,26. Therefore, even a perceived risk of increased liability that a history of incarceration may carry has the potential to swing that cost-benefit analysis toward denying admission to justice-involved patients27.

These perceived barriers, paired with our quantitative findings of significantly limited bed availability for incarcerated patients, suggest that alternative nursing home placement options are required for older incarcerated individuals granted compassionate release to receive the care they need.

This is the first study to examine the real-world availability of community nursing home services for incarcerated persons seeking compassionate release. Our findings suggest that the limited state-wide availability of nursing home care to incarcerated individuals is a barrier to the widespread implementation of compassionate release laws. If this policy and market gap is not addressed, patients may continue to remain incarcerated and unable to receive more appropriate nursing care as they age or illness advances.

Limitations

These findings may underestimate the number of nursing homes that would reject patients coming from carceral settings. The way questions were posed regarding incarceration status and criminal history may have introduced the social desirability bias28. Put differently, the study design could not prevent admissions coordinators from saying they would still consider an incarcerated patient for nursing home admissions because that is the socially desirable response when, in reality, the patient would be rejected later in the process for unspecified reasons.

Another limitation of this study is that it primarily quantified the responses of nursing home admissions coordinators. While we can assume that the responses of admissions coordinators reflected the official policies of the long-term nursing facilities themselves, there may be some discrepancy between responses during a brief phone call and the official nursing facility policy, and likewise between policy and practice. However, admissions coordinators are the primary point of contact for individuals seeking long-term nursing care, and so this may reflect real-world dynamics more accurately.

This study is further limited by generalizability. While 82.4% of long-term nursing facilities in Rhode Island were successfully included, Rhode Island is a uniquely small state with no state-run public nursing home. As such, the specific nursing home landscape in Rhode Island may not translate to other states that may be better equipped to provide nursing home care to incarcerated patients granted compassionate release.

The problem of generalizability also applies to how much of a challenge the compassionate release process is in RI compared to other states. A 2018 study by Families Against Mandatory Minimums (FAMM) assigned a report card for every state’s compassionate release programs. RI is 1 of 5 states that received an A, A+, or A- grade, compared to 34 out of 50 states that received an F29,30. Since one of the metrics the FAMM study judged compassionate release programs on was the efficacy of discharge planning, it is possible that the results of this study may be more dramatic in many other states.

The model patient used in our study had a specific set of characteristics that may not be reflected in real-world incarcerated persons granted compassionate release. Other medical conditions or criminal legal system factors may increase or decrease the likelihood of placement. Our sample patient was stated to be able to pay privately for nursing home care for 1 year. This was done to eliminate insurance as a factor for bed availability to truly isolate incarceration as the sole independent variable impacting responses in this study. However, the reality is that most incarcerated patients cannot privately pay for long term nursing care and would likely rely on Medicaid31. Nursing homes frequently have limited Medicaid beds, creating a separate financial barrier to nursing home admissions from the community32. Incarcerated patients granted compassionate release may, therefore, face other barriers to finding a nursing home bed beyond incarceration itself.

Facility size was assessed as a potential confounder, though it did not significantly impact results. However, other unmeasured facility-level factors such as ownership status, staffing capacity, or proximity to schools (in cases of a sexual offense) could also influence decision-making and warrant future study.

Next steps

This is the first state-wide survey of nursing home availability to incarcerated persons granted compassionate release. Future research is needed to replicate this study design in other states that may have different nursing home industries or compassionate release policies.

Nearly a quarter of facilities stated that having any criminal background was prohibitive for nursing home admissions, with some stating that this was aligned with their facility’s policies. Moving forward, future projects should better characterize the prevalence and quality of policies that limit nursing home admissions based on incarceration history.

Furthermore, our study suggests that there are a very small number of nursing home facilities that are particularly open to caring for justice-involved patients. Future research can aim to better understand what allows these facilities to comfortably consider patients with carceral histories for nursing home admissions. By doing so, future partnerships or policies can be designed to strengthen the ability of certain facilities to care for justice-involved patients.

Conclusion

The aging prison population will continue to challenge our healthcare and prison systems. The question of how to provide appropriate long-term nursing care within or outside of carceral facilities unequipped for nursing home-level services will only grow as incarcerated persons grow older and develop chronic diseases. Although compassionate release allows for the discharge of individuals deemed unlikely to pose a public safety risk and data shows extremely low recidivism rates among elderly parolees, nursing homes remain reluctant to accept these patients. The lack of community placement options not only limits access to needed healthcare services but also undermines compassionate release programs intended to ease prison overcrowding and ultimately ensure humane treatment for those no longer considered a public threat. As a result, a growing number of elderly individuals will continue to remain incarcerated not because they pose a danger to society, but because no nursing home will take them.

Data availability

The de-identified dataset generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Access to the data may require approval from the Lifespan/Brown University Health Institutional Review Board to ensure compliance with ethical standards and institutional policies.

References

Widra, E. The Aging Prison Population: Causes, Costs, and Consequences (Prison Policy Initiative, 2023).

Kaiksow, F. A., Brown, L. & Merss, K. B. Caring for the rapidly aging incarcerated population: the role of policy. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 49 (3), 7–11 (2023).

Greene, M. et al. Older adults in jail: high rates and early onset of geriatric conditions. Health Justice. 6 (1), 3 (2018).

Bedard, R., Metzger, L. & Williams, B. Ageing Pisoners: An Introduction to Geriatric Health-Care Challenges in Correctional Facilities. International Review of the Red Cross, 917–939. (2016).

Mitchell, A. & Williams, B. Compassionate release policy reform: Physicians as advocates for human dignity. AMA J. Ethics. 19 (9), 854–861 (2017).

Berry, I. I. I. W.W., Extraordinary and Compelling: A Re-Examination of the Justifications for Compassionate Release (Maryland Law Review, 2008).

Williams, B. A. et al. Balancing punishment and compassion for seriously ill prisoners. Ann. Intern. Med. 155 (2), 122–126 (2011).

Laws, R. I. G. Title 13 - Criminals – Correctional InstitutionsChapter 13 – 8.1 - Medical and Geriatric ParoleSection 13-8.1-2. - Purpose. (2024).

General, U. D. o.J.O.o.t.I., The Impact of An Aging Inmate Population on the Federal Bureau of Prisons. Published May Revised February 2016. (2015).

Holland, M. et al. Access and Utilization of Compassionate Release in State Departments of Correctionsp. 49–65 (Mortality, 2021).

Garrido, M. & Frakt, A. B. Challenges of aging population are intensified in prison. JAMA Health Forum. 1 (2), e200170 (2020).

Seaward, H. et al. Stigma management during reintegration of older incarcerated adults with mental health issues: A qualitative analysis. Int. J. Law Psychiatry. 89, 101905 (2023).

Rankin, K. A. et al. Secret shopper studies: An unorthodox design that measures inequities in healthcare access. Arch. Public. Health. 80 (1), 226 (2022).

Health, R. I. D. Nursing Home Summary Report. (2024).

Corrections, R. I. D. Fiscal Year 2024 Annual Population Report. (2025).

Prescott, J. J., Pyle, B. & Starr, S. B. Understanding Violent-Crime Recidivism: Notre Dame Law Review. pp. 1643–1698, 1688. (2020).

Office, U. S. G. A. Long-Term Care Facilities: Information on Residents Who Are Registered Sex Offenders or Are Paroled for Other Crimes. : GAO-06-326. (2006).

Tak, S. et al. Workplace assaults on nursing assistants in US nursing homes: A multilevel analysis. Am. J. Public. Health. 100 (10), 1938–1945 (2010).

Ferrah, N. et al. Resident-to-resident physical aggression leading to injury in nursing homes: A systematic review. Age Ageing. 44 (3), 356–364 (2015).

Howell, B. A. et al. The stigma of criminal legal involvement and health: A conceptual framework. J. Urban Health. 99 (1), 92–101 (2022).

P, L. and M. T, Criminal records and housing: an experimental study. J. Exp. Criminol. 527–535. (2017).

Development, U. S.D.o.H.a.U., Office of General Counsel Guidance on Application of Fair Housing Act Standards to the Use of Criminal Records by Providers of Housing and Real Estate-Related Transactions. (2016).

Montano v. Bonnie Brae Convalescent Hosp., I., 79 F. Supp. 3d 1120 (C.D. Cal, 2015).

Fair Hous. Just. Ctr., I.v.C., No. 18-CV-3196 (VSB), 2019 WL 4805550. S.D.N.Y. Sept. 30, (2019).

Grabowski, D. C. & Mor, V. Nursing home care in crisis in the wake of COVID-19. JAMA 324 (1), 23–24 (2020).

Commission, M. P. A. Report To the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy MedPAC,(2024).

Corson, T. R. & Nadash, P. Providing long term care for sex offenders: liabilities and responsibilities. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 14 (11), 787–790 (2013).

Bispo Júnior, J. P. Social desirability bias in qualitative health research. Rev. Saude Publica. 56, 101 (2022).

Minimums, F. A. M. FAMM Releases National Poll Results, Compassionate Release Report Cards for all 50 States and D.C.(2022).

Minimums, F. A. M. Clemency and Compassionate Release: Your State’s Laws.

Rabuy, B. & Kopf, D. Prisons of Poverty: Uncovering the Pre-Incarceration Incomes of the Imprisonedp. 01–05 (Prison Policy Initiative, 2015).

Assistance, M. P. Medicaid and Nursing Homes. Medicaid Planning Assistance.

Funding

Dr. Veronica Petersen ’55 and Dr. Robert A. Petersen Educational Enhancement Fund at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University. NIDA K23DA055695. NIA 5R24AG065175. Dr. Nicole Mushero: HRSA: K0149060.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.D., R.J., B.B., and B.W. contributed to data collection, study design, and manuscript drafting. G.D. also participated in all manuscript revisions. D.S., K.T., and S.P. supported study operations, contributed to project design, provided subject matter expertise, and participated in manuscript revision. M.M. contributed to data collection, manuscript editing, and facilitated project management of the team. M.S. and N.M. contributed to data analysis and manuscript editing. J.B. conceived the study, supervised all aspects of the project, contributed to data analysis and interpretation, and finalized the manuscript for submission. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dayanim, G., Junkin, R., Bergsneider, B. et al. Nursing home availability for incarcerated persons granted compassionate release. Sci Rep 15, 37676 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21492-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21492-7