Abstract

Curcumin has attracted attention for its nontoxic chemopreventive effects; however, the pathways underlying these effects in colon cancer remain unclear. We investigated the potential interplay between curcumin and integrin β1 in colon cancer. Human colon cancer (HCT) 116 cell line and fibroblast cells were treated with curcumin, and cell proliferation was assessed using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay and western blotting. Using western blotting and confocal microscopy in curcumin-treated HCT116 cells, we analyzed integrin β1 expression and the roles of talin and rab25 in integrin β1 activation by curcumin. Curcumin significantly decreased the survival of HCT116 cells but did not significantly affect the survival of fibroblast cells. Moreover, curcumin significantly increased integrin β1 expression in HCT116 cells, which was primarily mediated by talin. In contrast, rab25 expression remained unchanged after curcumin treatment. Using rab25-specific small interfering ribonucleic acid knock-down experiments, we confirmed that curcumin increased integrin β1 expression even in the absence of rab25. Confocal microscopy revealed a dose-dependent increase in integrin β1 and talin expression, with consistent spatial distribution patterns in response to curcumin. This study reports that curcumin acts as an anticancer agent in colon cancer by modulating integrin β1 expression through a talin-mediated pathway rather than through rab25.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anticancer drugs are widely used to treat many types of cancer; however, their toxic effects on normal cells remain a concern. In recent years, the efficacy of medicinal herbs in selectively inducing apoptosis in tumor cells and preserving the integrity of healthy organs has received attention1,2. Curcumin, a polyphenolic compound derived from turmeric, is a prominent spice and traditional medicinal agent in the Indian culture that has received considerable attention for its nontoxic chemo preventive properties against human cancers3,4. Curcumin has been shown to interfere with carcinogenesis and disrupt the proliferation of malignant cells by exerting anti-angiogenic effects, promoting apoptosis, and disrupting the cell cycle5,6,7. Accumulating evidence suggests that curcumin exerts anticancer effects by regulating various signaling pathways, including the epidermal growth factor receptor/platelet-derived growth factor (EGFR/PDGFR), AKT/mTOR, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and signal transducer of activators of transcription (STAT) pathways8,9,10,11,12. Among these pathways involved in the anticancer effects of curcumin, integrins have emerged as important molecular players capable of modulating various signaling molecules13,14,15,16.

Integrins, heterodimeric proteins composed of α and β monomers, are a prominent class of cell surface receptors found in many animal species. Alterations in the expression or function of integrins play important roles in cancer progression17. Two main mechanisms regulate the action of integrins: the talin- and rab-mediated pathways18. Talin is a major cytoskeletal actin-binding protein that binds to integrin β tails and co-localizes with activated integrins. It plays a critical role in integrin activation by regulating their endocytosis19. Rab proteins are members of the Ras superfamily of guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases) and are involved in recycling proteins from the endosome to the plasma membrane. Rab25 promotes integrin β1 activation through a recycling process called trafficking20. Several studies have reported that integrins are involved in the anticancer effects of curcumin; however, little is known about the underlying mechanisms, especially in colon cancer.

In this study, we investigated the involvement of integrin β1 in the anticancer effect of curcumin. Specifically, we focused on determining whether talin or rab25 is involved in the integrin β1-mediated anticancer effect of curcumin.

Methods

Preparation of cells

The human colon cancer (HCT) 116 cell line (Cat: CCL-247, ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) was purchased from the Korean Cell Line Bank. HCT116 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Cat: LM 011 − 01, Welgene, Daegu, Korea) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Cat: 16000–044, Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Cat: LS 202-02, Welgene) in 90 mm dishes (Cat: 20100, SPL, Pocheon, Korea) in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

The IL-1β-stimulated colonic myofibroblast (CCD-18Co) cell line (Cat: CRL1459, ATCC), which exhibits fibroblast morphology, was purchased from the Korean Cell Line Bank. Cells were cultured in Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium (Cat: LM007-54, Welgene) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Cat: 16000–044, Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin solution (Cat: LS 202-02, Welgene) in 90 mm cell culture dishes (Cat: 20100, SPL, Pocheon, Korea) in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay

The HCT116 and CCD-18Co cells were seeded in 96-well plates (Cat: 30096, SPL) and incubated overnight at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. Then, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, and 50 µg/mL of curcumin (Cat: 08511, Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) was added to the cells, and the cells were incubated for 24 and 48 h. Thereafter, thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (MTT, Cat: 5655, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) solution (5 mg/mL in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) was added to each well, and the cells were incubated for 4 h at 37 °C. The culture medium was then removed from each well, and 200 µL of dimethyl sulfoxide solution was added to each well for 15 min. Absorbance was measured at 590 nm using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay plate reader (SpectraMax ABS Plus, San Jose, CA, USA).

Protein purification

The cultured cells were washed twice with cold PBS and treated with 0.05% trypsin– ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (Cat: LS015-01, Welgene) for 3 min at 37 °C. A complete medium was added to in-activate trypsin–EDTA, the cells were collected in a tube, centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 5 min, and the supernatant was removed. The pellet was washed with cold PBS, centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 5 min, and the supernatant was removed twice. Harvested cell pellets were treated with 200 µL of pro-prep lysis buffer (Cat: 17081 iNtRON Biotechnology, Ko-rea), incubated on ice for 30 min at -20 °C, centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatants were transferred to a new tube. Protein concentrations were measured using the Pierce™ bicinchoninic acid assay Protein Assay Kits (Cat: 23227, Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunoblotting

Equal amounts of proteins were separated by 8% or 15% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Cat: 10600021, Cytiva). The membrane was blocked using 5% skim milk for 1 h, incubated with a specific primary antibody for 1 h, and blotted with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-linked secondary antibody for 1 h. Labeled proteins were detected using the SuperSignal™ West Atto Ultimate Sensitivity Substrate (Cat: a38554, Thermo Fisher Scientific) on the ChemiDoc Imaging Systems (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Primary antibodies were diluted to 1:1000, whereas secondary antibodies were diluted to 1:5000. The anti-integrin β1 (Cat: 34971), anti-rab25 (Cat: 13081), anti-talin 1 (Cat: 4021), anti-β-actin (Cat: 4970 S), HRP-linked anti-mouse IgG (Cat: 7076), and HRP-linked anti-rabbit IgG (Cat: 7074) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA).

Rab25 knockdown with SiRNA transfection

On the day before transfection, HCT116 cells were seeded (1.5 × 104 cells) in a 6-well plate. Before transfection, the medium was replaced with fresh medium without antibiotics. siRNA transfections on HCT116 cells were performed using Lipofectamine™ RNAiMAX (Cat: 13778075, Thermo Fisher Scientific), HS_Rab25_5 FlexiTube siRNA (Cat: SI03036544, FlexiTube GeneSolutions, Qiagen, Denmark), and Opti-MEM™ (Cat: 31985062, Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The final siRNA concentration was 20 nM between 10, 20, and 50 nM for 24 h. Knock-down efficiency was analyzed using the band density determined using western blotting. After rab25 knockdown in the HCT116 cell line, the dishes were washed twice with PBS, and 10 µg/mL of curcumin (Cat: 08511, Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) with the complete medium was added to the cells for 24 and 48 h. The mock group was treated with Lipofectamine™ RNAiMAX and Opti-MEM™ only, without siRNA, to control for the effects of the transfection reagent.

Confocal microscopy

HCT116 cells were seeded (6 × 104) in 4-well chamber slices (Cat: 30114, SPL) in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37 °C overnight. Cells were washed twice with PBS, 10 µg/mL of curcumin (Cat: 08511, Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) with the complete medium was added to the cells, and cells were incubated for 24 and 48 h in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. The medium was removed, the cells were washed twice with PBS, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (Cat: P2031, Biosesang Inc., Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea) for 15 min at room temperature (RT), and rinsed twice with PBS. After fixation, the cells were permeabilized with 0.1% triton x-100 in PBS (1 mL) for 10 rinses and washed twice with PBS. The cells were blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 1 min at RT and rinsed twice with PBS.

The cells were incubated with the primary antibody in 0.1% BSA and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The cells were rinsed twice with PBS, incubated with the secondary antibody or 488-labeled integrin β1 (Cat: ab193591, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) in 0.1% BSA in PBS for 1 h at RT, and rinsed with PBS. The silicon wall was removed from the slide, and the cells were mounted using Fluoroshield mounting medium containing 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Cat: F6057, Sigma-Aldrich). The primary antibodies used were anti-talin 1 rabbit monoclonal antibody (1:500, Cat: 4021, Cell Signaling) diluted 1:500 or 488-labeled integrin β1 anti-body (Cat: ab193591, Abcam) diluted 1:500. The secondary antibody used was 594-labeled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) heavy and light chains (Cat: ab150080, Abcam) diluted 1:500. Fluorescence was analyzed using a Zeiss LSM 800 (Carl Zeiss) confocal laser scanning microscope equipped with a 40× numerical aperture 1.2 objective (water) or a 63× numerical aperture 1.4 objective (oil). Images were acquired using the ZEN software (Carl Zeiss). Quantitative analysis of mean fluorescence intensity was performed using ImageJ, a Java-based image analysis program.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was repeated three or more times, and protein levels were calculated using β-actin levels as the reference. The band intensities obtained through western blot experiments were quantified using the National Institutes of Health software (ImageJ). The quantified data were converted to percent control and plotted using the GraphPad Prism software ver. 5.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, USA). Statistical analyses between different treatments were performed using the Mann–Whitney U test, and all statistical analyses were performed using SPSS ver. 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical significance was considered when P-values were < 0.05.

Results

Curcumin induces cancer-specific cytotoxicity

To investigate the effect of curcumin on cancer cells, HCT116 cells were treated with different doses of curcumin (0.5, 1, 5, 10, 20, and 50 µg/mL), and cell viability was assessed using MTT assay after 24 and 48 h. The MTT assay showed that curcumin effectively inhibited cell proliferation in a dose-dependent manner. Cellular proliferation was most effectively suppressed at a curcumin dose of 10 µg/mL. This trend remained consistent across different treatment durations of 24 and 48 h (Fig. 1a).

MTT assay after treatment of HCT116 and CCD-18Co cells with curcumin. (a) After treatment of HCT116 cells with curcumin, cellular proliferation is inhibited in a dose-dependent and time-dependent manner; (b) In CCD-18Co cells, curcumin exhibited relatively lower cytotoxicity compared to HCT116 cells. (c) The IC50 values of curcumin for HCT116 cells were 4.69 µg/mL and 5.13 µg/mL at 24 and 48 h, respectively. (d) The IC50 values of curcumin for CCD-18Co cells were 26.85 µg/mL and 12.15 µg/mL at 24 and 48 h, respectively. Data were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test. Each condition was tested in triplicate across three independent experiments. Results are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. MTT, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide; HCT, human colon cancer cell line.

To determine the effect of curcumin on normal cells, CCD-18Co fibroblast cells were treated with curcumin in a similar manner. The MTT assay showed that curcumin exhibits relatively lower cytotoxicity in CCD-18Co cells compared to HCT116 cancer cells (Fig. 1b). The IC50 values of curcumin for each cell line at 24 and 48 h were as follows: 4.69 µg/mL and 5.13 µg/mL for HCT116 cells, and 26.85 µg/mL and 12.15 µg/mL for CCD-18Co cells (Fig. 1c and d), respectively. These results suggest the preferential cytotoxicity of curcumin toward colon cancer cells compared to normal cells.

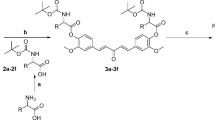

Curcumin induces integrin β1 activation via a talin-dependent pathway

To investigate the involvement of integrin β1 in the anticancer effect of curcumin, we analyzed the expression of integrin β1 after curcumin treatment of HCT116 cells. Curcumin was added at a concentration of 10 µg/mL, which is the optimal dose between anticancer effect and cytotoxicity, as observed in previous experiments (Fig. 1a). As shown in Fig. 2, the expression of integrin β1 significantly increased at 24 and 48 h after treatment of HCT116 cells with curcumin.

After treatment of HCT116 cells with curcumin, an increase in integrin β1 and talin expression is observed, but no significant changes in rab25 expression are observed. (a) Expression of integrin β1, talin, and rab25, depending on curcumin treatment, is analyzed using western blotting; (b) Transcriptional levels of integrin β1, talin, and rab25 are measured using real-time polymerase chain reaction. Data were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test. Each condition was tested in triplicate across three independent experiments. Results are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. HCT human colon cancer cell line.

To determine whether talin or rab25 is involved in the activation of integrin β1 by curcumin, the expressions of talin and rab25 were assessed in the same manner. HCT116 cells were treated with 10 µg/mL of curcumin, and the expression of talin and rab25 was assessed using western blotting after 24 and 48 h. While the increase in talin expression at 24 h was not visually prominent in the blot image (Fig. 2a), densitometric analysis (Fig. 2b) revealed a statistically significant upregulation compared to the control. At 48 h, talin expression was more clearly elevated. In contrast, rab25 expression did not show any significant change at either time point. These findings suggest that the increase in integrin β1 expression by curcumin occurs in a talin-mediated, but not rab25-mediated, manner.

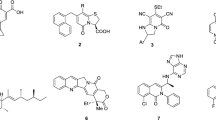

Curcumin induces integrin β1 activation via a Rab25-independent pathway

Although trafficking by rab25 is one of the major mechanisms by which integrin β1 is activated, curcumin increased the expression of integrin β1 without changing the expression of rab25 (Fig. 2). To determine whether the interaction between curcumin and integrin β1 occurs independently of rab25, we performed further experiments by modulating the expression of rab25. HCT116 cells were transfected with rab25-specific siRNA, and the efficacy of the knockdown was validated using western blotting, which confirmed a substantial reduction following treatment with 20 nM rab25 siRNA (Fig. 3a). After successful rab25 knockdown, a reduction in the cell number was observed, and this phenomenon was further enhanced by curcumin treatment in the rab25 knockdown group (Fig. 3b).

Effects of rab25 knockdown and curcumin treatment on the expression of rab25, integrin β1, and talin in HCT 116 cells. (a) siRNA transfection effectively reduced rab25 expression. (b) Cell viability measured by MTT assay after sequential treatment with rab25 siRNA (20 nM) and curcumin (10 µg/mL). (c) Western blot analysis showing that rab25 knockdown transiently increased integrin β1 expression at 24 h, which was not sustained at 48 h. Curcumin treatment led to a marked upregulation of integrin β1 and talin expression at 48 h. (d) Transcriptional levels of rab25, integrin β1 and talin were measured using real-time PCR. Data were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test. Each condition was tested in triplicate across three independent experiments. Results are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. C, curcumin; HCT, human colon cancer cell line; MTT, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide; siRNA, small interfering ribonucleic acid.

The expression of rab25, integrin β1, and talin was evaluated after curcumin treatment in the rab25 knockdown group. As expected, rab25 expression remained suppressed after siRNA transfection and was not restored by curcumin treatment. Interestingly, integrin β1 expression showed a transient increase at 24 h following rab25 knockdown, but this was not sustained at 48 h, suggesting a short-term cellular response to rab25 depletion. In contrast, curcumin treatment resulted in a robust and sustained upregulation of integrin β1 at 48 h, regardless of rab25 knockdown status. Similarly, talin expression also increased after 48 h of curcumin treatment (Fig. 3c). These findings suggest that curcumin exerts its anticancer effect by upregulating integrin β1 via a talin-mediated pathway, rather than through rab25.

Visualization of the expression of integrin β1 and Talin in response to Curcumin

To determine the spatial distribution and quantitative expression levels of integrin β1 and talin in response to curcumin treatment, confocal microscopy was performed in HCT116 cells. A significant, dose-dependent increase in cytosolic integrin β1 expression was observed following curcumin treatment (Fig. 4a and b). Additionally, HCT116 cells treated with 10 µg/mL curcumin were evaluated at 24 and 48 h using confocal microscopy with integrin β1 and talin-specific antibodies. The expression levels of both integrin β1 and talin were elevated at both time points compared with the control group (Fig. 4c, d).

Confocal microscopy and quantitative analysis of integrin β1 and talin expression in HCT116 cells following curcumin treatment. (a) Cytosolic expression of integrin β1 increased in a dose-dependent manner following curcumin treatment. Cells were stained with anti-integrin β1 antibody (green) and DAPI (blue) and imaged by confocal microscopy. Original magnification, 63×. (b) Quantification of mean fluorescence intensity of integrin β1 after curcumin treatment. Results are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. (c) HCT116 cells were treated with 10 µg/mL curcumin for 24 h and 48 h. The expression of integrin β1 (green) and talin (red) increased after treatment. Cells were counterstained with DAPI (blue), and merged images indicate co-localization. Original magnification, 40×. (d) Quantitative analysis of integrin β1 and talin fluorescence intensities. Results are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. HCT human colon cancer cell line.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the involvement of integrin β1 in the anticancer effect of curcumin in colon cancer. We found that curcumin exerts its anticancer effects by modulating the expression of integrin β1 and that this modulation occurs through a talin-mediated pathway and not through rab25. In particular, the cytotoxic effects of curcumin were observed only in cancer cells and not in normal cells, suggesting that curcumin exhibits cancer-specific cytotoxicity.

Many studies have investigated the anticancer effects of curcumin in various types of cancer. Curcumin inhibits cancer growth by inhibiting matrix metalloproteinases, NF-κB, tumor necrosis factor-α, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, and EGFR21,22,23. Curcumin exerts its anticancer effects by regulating the expression of molecules involved in cell adhesion24,25. Studies have shown that curcumin inhibits cancer progression by regulating various cellular pathways, including EGFR/PDGFR, AKT/mTOR, and MAPK, which are either signaling partners or downstream molecules of integrin8,9,10,11,12. Previous studies on the integrin-mediated anticancer effect of curcumin have shown mixed results, with some studies showing that curcumin upregulates integrin expression and others showing that it downregulates it. Ray et al. demonstrated that curcumin exhibits antimetastatic properties by increasing integrin α5β1 and αvβ3 expression in lung cancer26. Coleman et al. showed that curcumin inhibits integrin β4 in breast cancer cells13. In contrast, a study reported that curcumin exerts anti-apoptotic and anti-catabolic effects by increasing integrin levels27. Mani et al. reported conflicting results, with curcumin upregulating integrin β1 and β4 and downregulating integrin β2 in bladder cancer cells28. In our study, we showed that curcumin inhibited cell proliferation by increasing the expression of integrin β1 in colon cancer cells. This effect was also mediated by talin, a key molecule that regulates integrin activity.

Integrins, which mediate cell adhesion to extracellular matrix ligands and cellular counter receptors, are a family of 24 heterodimeric receptors composed of α- and β-subunits17. Activation of integrins can be induced either by cytoplasmic events (‘‘inside-out’’ activation) or by extracellular stimuli (‘‘outside-in’’ activation)18. Talin is a large, multi-domain protein containing FERM domains. Talin, a key integrin regulator, binds to the cytoplasmic tail of the integrin β subunit to induce “inside-out” activation of integrin19. Rab proteins are members of the Ras superfamily of GTPases and are involved in recycling proteins from the endosome to the plasma membrane. Rab25 promotes the “outside-in” activation of integrins through a recycling process20. The present study showed that curcumin acts as an anticancer agent without modulating integrin recycling. Our findings shed light on the pivotal role of the integrin-talin interplay in mediating the tumor-suppressive effects of curcumin in colon cancer.

Curcumin, which accounts for 2–8% of the chemicals in turmeric, is thought to be the primary source of the plant’s yellow-gold color and is also responsible for numerous other properties3,4. Owing to its diverse capabilities and low intrinsic toxicity, curcumin has had a significant impact on a wide range of pharmacological discoveries, including anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and antioxidant drugs5,6,7. The low toxicity of curcumin is one of its most important properties, making it a suitable therapeutic agent. Low doses of curcumin have no adverse effects. High doses of curcumin have been shown to inhibit cancer cell proliferation without affecting normal cells29,30,31. These properties have led to its widespread use in cancer treatments32. In this study, we found that the integrin-mediated anticancer properties of curcumin in colon cancer cells concurrently attenuated its harmful effects on normal fibroblasts. The IC50 values support the preferential cytotoxicity of curcumin toward colon cancer cells compared to normal fibroblasts, although some degree of toxicity to normal cells was observed at higher concentrations and longer exposure durations. These findings suggest a potential therapeutic window, but also highlight the need for careful dose optimization in future in vivo or clinical applications. In addition to the anticancer effects of curcumin, some studies have shown that curcumin inhibits proteins associated with drug resistance and enhances the efficacy of anticancer drugs.

This study is limited by the use of a single cell line, which may affect the generalizability of our findings. However, we selected HCT116 cells because they are widely used in colon cancer research and are well-characterized in terms of their molecular background, including moderate integrin β1 expression and responsiveness to curcumin. To partially address this limitation, we cited previous studies showing curcumin-induced cytotoxicity in other colon cancer cell lines33,34,35. Future studies using diverse cell lines with varying genetic backgrounds and integrin β1 activity will help validate our results. Another limitation of this study is the absence of talin knockdown experiments. Nevertheless, increased talin expression and its co-localization with integrin β1 support its functional involvement. Talin is a cytoskeletal adaptor protein that links integrin β1 to the actin cytoskeleton and facilitates inside-out integrin activation. Its upregulation suggests a mechanistic role in curcumin-induced cytotoxicity. To further investigate this, future studies will employ gene knockdown or CRISPR-based gene editing to disrupt talin expression and evaluate its effect on integrin signaling and cell survival. In addition, functional assays to directly link integrin β1 activation with apoptosis, such as flow cytometry or caspase activity analysis, were not performed. Future studies incorporating loss-of-function or pathway inhibition approached will be necessary to clarify the mechanistic role of integrin β1 in curcumin-induced cytotoxicity.

This study underscores the clinical relevance of curcumin as a selective anticancer agent, particularly for colon cancer. Our findings suggest that medicinal herbs, such as curcumin, which possesses nontoxic chemo preventive properties, may be promising candidates in this regard. Although we did not delineate a specific pathway, our research highlights the integral role of the integrin-mediated pathway, independent of integrin trafficking modulation, in the anticancer properties of curcumin. Our study provides valuable insights into the diverse functions of common molecular entities, such as integrins, in tumorigenesis, along with the location of the tumor, which would be useful in selecting specific anticancer therapies appropriate for each person.

Conclusions

In conclusion, curcumin exerts cancer-specific cytotoxicity by modulating the expression of integrin β1. This modulation occurs through a talin-mediated pathway and not through rab25. Further investigation of the complex interplay between curcumin and integrin-mediated signaling molecules holds promise for the development of targeted anticancer therapeutics for colon cancer.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Mansouri, K. et al. Clinical effects of Curcumin in enhancing cancer therapy: A systematic review. BMC Cancer. 20, 791 (2020).

Ahmadi, F. et al. Grandivittin as a natural minor groove binder extracted from ferulago Macrocarpa to ct-DNA, experimental and in Silico analysis. Chem. Biol. Interact. 258, 89–101 (2016).

Koroth, J. et al. Investigation of anti-cancer and migrastatic properties of novel Curcumin derivatives on breast and ovarian cancer cell lines. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 19, 273 (2019).

Chattopadhyay, I., Biswas, K., Bandyopadhyay, U. & Banerjee, R. K. Turmeric and curcumin: biological actions and medicinal applications. Curr. Sci. 87, 44–53 (2004).

Maheshwari, R. K., Singh, A. K., Gaddipati, J. & Srimal, R. C. Multiple biological activities of curcumin: a short review. Life Sci. 78, 2081–2087 (2006).

Ono, K., Hasegawa, K., Naiki, H. & Yamada, M. Curcumin has potent anti-amyloidogenic effects for alzheimer’s beta-amyloid fibrils in vitro. J. Neurosci. Res. 75, 742–750 (2004).

Sun, C., Zhang, S., Liu, C. & Liu, X. Curcumin promoted miR-34a expression and suppressed proliferation of gastric cancer cells. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 34, 634–641 (2019).

Zhou, Y., Zheng, S., Lin, J. J., Zhang, Q. J. & Chen, A. The interruption of the PDGF and EGF signaling pathways by Curcumin stimulates gene expression of PPARgamma in rat activated hepatic stellate cell in vitro. Lab. Invest. 87, 488–498 (2007).

Chen, A., Xu, J. & Johnson, A. C. Curcumin inhibits human colon cancer cell growth by suppressing gene expression of epidermal growth factor receptor through reducing the activity of the transcription factor Egr-1. Oncogene 25, 278–287 (2006).

Yu, S., Shen, G., Khor, T. O., Kim, J. H. & Kong, A. N. T. Curcumin inhibits Akt/mammalian target of Rapamycin signaling through protein phosphatase-dependent mechanism. Mol. Cancer Ther. 7, 2609–2620 (2008).

Chaudhary, L. R. & Hruska, K. A. Inhibition of cell survival signal protein kinase B/Akt by Curcumin in human prostate cancer cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 89, 1–5 (2003).

Squires, M. S. et al. Relevance of mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) and phosphotidylinositol-3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/PKB) pathways to induction of apoptosis by Curcumin in breast cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 65, 361–376 (2003).

Coleman, D. T., Soung, Y. H., Surh, Y. J., Cardelli, J. A. & Chung, J. Curcumin prevents palmitoylation of integrin β4 in breast cancer cells. PLOS ONE. 10, e0125399 (2015).

Soung, Y. H. & Chung, J. Curcumin Inhibition of the functional interaction between integrin α6β4 and the epidermal growth factor receptor. Mol. Cancer Ther. 10, 883–891 (2011).

Javadi, S., Zhiani, M., Mousavi, M. A. & Fathi, M. Crosstalk between epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFR) and integrins in resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in solid tumors. Eur. J. Cell. Biol. 99, 151083 (2020).

Bachmeier, B. E. et al. Curcumin downregulates the inflammatory cytokines CXCL1 and – 2 in breast cancer cells via NFkappaB. Carcinogenesis 29, 779–789 (2008).

Sun, Z., Costell, M. & Fässler, R. Integrin activation by talin, kindlin and mechanical forces. Nat. Cell. Biol. 21, 25–31 (2019).

Margadant, C., Kreft, M., de Groot, D. J., Norman, J. C. & Sonnenberg, A. Distinct roles of Talin and kindlin in regulating integrin α5β1 function and trafficking. Curr. Biol. 22, 1554–1563 (2012).

Pernier, J. et al. Talin and kindlin cooperate to control the density of integrin clusters. J Cell. Sci 136 (2023).

Goldenring, J. R. & Nam, K. T. Rab25 as a tumour suppressor in colon carcinogenesis. Br. J. Cancer. 104, 33–36 (2011).

Duvoix, A. et al. Chemopreventive and therapeutic effects of Curcumin. Cancer Lett. 223, 181–190 (2005).

Qadir, M. I., Naqvi, S. T. Q. & Muhammad, S. A. Curcumin: a polyphenol with molecular targets for cancer control. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 17, 2735–2739 (2016).

Niedzwiecki, A., Roomi, M. W., Kalinovsky, T. & Rath, M. Anticancer efficacy of polyphenols and their combinations. Nutrients 8 (2016).

Sullivan, D. E., Ferris, M., Nguyen, H., Abboud, E. & Brody, A. R. TNF-alpha induces TGF-beta1 expression in lung fibroblasts at the transcriptional level via AP-1 activation. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 13, 1866–1876 (2009).

Sa, G. & Das, T. Anti cancer effects of curcumin: cycle of life and death. Cell. Div. 3, 14 (2008).

Ray, S., Chattopadhyay, N., Mitra, A., Siddiqi, M. & Chatterjee, A. Curcumin exhibits antimetastatic properties by modulating integrin receptors, collagenase activity, and expression of Nm23 and E-cadherin. J. Environ. Pathol. Toxicol. Oncol. 22, 49–58 (2003).

Shakibaei, M., Schulze-Tanzil, G., John, T. & Mobasheri, A. Curcumin protects human chondrocytes from IL-l1beta-induced Inhibition of collagen type II and beta1-integrin expression and activation of caspase-3: an Immunomorphological study. Ann. Anat. 187, 487–497 (2005).

Mani, J. et al. Curcumin combined with exposure to visible light blocks bladder cancer cell adhesion and migration by an integrin dependent mechanism. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 23, 10564–10574 (2019).

Anand, P., Sundaram, C., Jhurani, S., Kunnumakkara, A. B. & Aggarwal, B. B. Curcumin and cancer: an old-age disease with an age-old solution. Cancer Lett. 267, 133–164 (2008).

Boon, H. & Wong, J. Botanical medicine and cancer: a review of the safety and efficacy. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 5, 2485–2501 (2004).

Wargovich, M. J. Nutrition and cancer: the herbal revolution. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 15, 177–180 (1999).

Banik, K. et al. Piceatannol: A natural Stilbene for the prevention and treatment of cancer. Pharmacol. Res. 153, 104635 (2020).

Guo, Y. et al. Curcumin inhibits anchorage-independent growth of HT29 human colon cancer cells by targeting epigenetic restoration of the tumor suppressor gene DLEC1. Biochem. Pharmacol. 94, 69–78 (2015).

Dou, H. et al. Curcumin suppresses the colon cancer proliferation by inhibiting Wnt/β-Catenin pathways via miR-130a. Front Pharmacol 8 (2017).

Kaur, H. & Moreau, R. Curcumin represses mTORC1 signaling in Caco-2 cells by a two-sided mechanism involving the loss of IRS-1 and activation of AMPK. Cell Signal 78 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to Jin Soo Kim for his invaluable contributions to this project. His expertise and guidance have been crucial in navigating the challenges encountered along the way.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: H.K.K., B.Y.O. and R.L.; methodology: H.K.K., K.S.H. and G.T.N.; formal analysis and Investigation: H.K.K. and K.S.H.; writing - original draft preparation: H.K.K.; writing - review and editing: R.L. and B.Y.O.; funding acquisition: K.S.H. and G.T.N.; resources: R.L., K.S.H. and G.T.N.; supervision: R.L. and B.Y.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, H.K., Lee, RA., Hong, K.S. et al. Cancer-specific cytotoxicity of curcumin through regulation of integrin β1 expression in colon cancer. Sci Rep 15, 39218 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21627-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21627-w