Abstract

Natural sand scarcity and environmental concerns have encouraged the adoption of industrial waste materials in sustainable concrete. Foundry sand (FS) and coal bottom ash (CBA), both industrial waste materials, offer potential as partial replacements for natural sand. However, predicting the compressive strength (CS) of such mixes is complex due to nonlinear interactions among their components. This study proposes a novel, machine learning-based framework for predicting the CS of concrete incorporating FS and CBA. A dataset of 172 mix designs was compiled from published literature. Nine machine learning models were evaluated, including traditional regressors and ensemble methods. The Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) model achieved the highest accuracy, with R2 = 0.983, RMSE = 1.54 MPa, and MAPE = 3.47%. The key innovation of this work is the application of ensemble machine learning models for strength prediction in dual-waste concrete, which has been minimally explored in prior research. Feature importance analysis identified curing duration, superplasticizer dosage, cement content, and water-to-cement ratio as dominant predictors. This research demonstrates the effectiveness of artificial intelligence driven approaches in sustainable concrete mix design. By minimizing the need for trial and error experiments, the proposed method accelerates decision-making, reduces costs, and supports the circular economy by encouraging the use of industrial byproducts in construction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The most popular building material in the world, concrete is essential to contemporary urban growth and infrastructure. Yet, its massive production imposes severe environmental burdens, primarily due to the depletion of natural resources and high greenhouse gas emissions associated with cement manufacturing1,2. Globally, billions of tonnes of natural river sand are extracted each year, leading to severe ecological consequences such as riverbed degradation, habitat destruction, and a significant carbon footprint associated with transportation and processing3,4. Simultaneously, the cement industry contributes nearly 8% of global CO2 emissions, prompting researchers and practitioners to seek sustainable solutions to mitigate these impacts. To promote the sustainable production of concrete, two complementary strategies have gained prominence i.e., partially replacing the cementitious binder with supplementary cementitious materials like fly ash, silica fume, and ground granulated blast furnace slag, and another is replacing natural aggregates, particularly fine aggregates like river sand, with industrial by-products or waste materials5,6. This strategy not only lessens environmental deterioration but also aids in the management of solid waste streams, bringing building methods into line with the ideas of the circular economy. Among potential alternatives, coal bottom ash (CBA) and foundry sand (FS) have drawn significant attention as fine aggregate replacements in concrete7,8. CBA, a granular by-product from thermal power plants, is produced in large volumes worldwide. Its relatively porous and angular texture offers potential benefits such as improved workability and lighter unit weight, although care must be taken to mitigate its typically higher water absorption and potential for residual carbon. FS, produced during the metal casting process, consists mainly of high-purity silica sand coated with residual binder materials like bentonite and carbonaceous additives. In many cases, reclaimed FS exhibits particle size distribution and mechanical strength comparable to or even superior to that of natural river sand. Incorporating FS into concrete can reduce the environmental impact associated with sand mining and also divert large volumes of industrial waste from landfill disposal9.

Recent studies have shown that concrete mixes containing CBA or FS, individually or in combination, can, with the right mix design modifications, attain durability, flexural strength, and compressive strength that are on par with traditional concrete. For instance, partial replacement of natural sand with up to 30–40% CBA or FS often leads to acceptable workability and mechanical performance10,11. However, these materials are not without drawbacks. FS often increases water demand due to its finer texture and residual binders, while CBA exhibits higher porosity and inconsistent particle gradation, which may compromise mechanical strength and durability. Excessive use of these materials can lead to increased permeability, shrinkage, and reduced long-term performance. To mitigate these challenges, previous studies have employed techniques such as particle grading optimization, addition of superplasticizers, and thermal or chemical pre-treatment of waste materials. The physical and chemical characteristics of CBA and FS vary depending on their source, combustion circumstances, or reclamation methods, which contribute to the limited practical implementation of these encouraging discoveries. The complexity and variability of concrete produced with industrial by-products pose challenges for accurate strength prediction using traditional empirical or regression-based methods.

Over the past decade, the construction industry has increasingly turned to machine learning (ML) techniques, which excel at modeling complex, nonlinear relationships and can leverage large experimental datasets to identify hidden patterns. ML models like artificial neural networks, support vector machines, random forest, generalized linear, extremely randomized trees, deep learning, and gradient boosting have demonstrated promising accuracy in predicting concrete’s compressive strength, tensile strength, and durability properties12,13,14,15. By predicting performance outcomes using input variables like mix proportions, curing conditions, and material qualities, these models drastically cut down on the time and expense involved in experimental testing. By reducing reliance on extensive physical testing, ML not only accelerates mix design optimization but also enables more sustainable material usage through data-driven decision-making. The application of ML in concrete technology thus offers a transformative approach to predictive modeling, enhancing performance evaluation, resource efficiency, and circular construction practices. Recent studies have successfully used ML techniques such as generative adversarial networks, ensemble learning, and interpretable models for applications like predicting Marshall test results for asphalt design16, tensile strain capacity of engineered cementitious composites17, structural behavior of recycled concrete-filled tubes18, and stability analysis of soil slopes using Gaussian process regression19. These studies highlight ML’s versatility and accuracy in modeling both material-level and system-level behaviors, supporting its application in sustainable and recycled material systems20,21,22. More recently, ensemble machine learning models, which combine the predictive power of multiple base learners, have emerged as state-of-the-art tools in this field23. Ensemble methods, such as bagging, boosting, and stacking, often outperform single ML models by reducing prediction variance and bias24,25. In concrete technology, ensemble approaches have been applied to predict compressive strength with higher reliability, even for complex mixtures containing recycled aggregates, supplementary cementitious materials, and other alternative materials.

Despite the growing number of studies applying ML to concrete strength prediction, there remains a noticeable research gap regarding the prediction of concrete strength produced using combined replacements of FS and CBA. A very interesting but little-studied method for producing concrete sustainably is to use a combination of CBA and FS in place of natural sand. Predicting the strength of such concrete accurately is essential for its acceptance in structural applications. In order to forecast the compressive strength of concrete made by partially or completely substituting FS and CBA for natural sand, this work intends to create and evaluate an ensemble machine learning model. A large dataset collected from the published literature is used to train the ensemble model. Additionally, the study contrasts the ensemble model’s predictive performance with that of popular single machine learning models, such as artificial neural networks, decision trees, and support vector regression. By doing so, the manuscript seeks to demonstrate the feasibility of CBA and FS as sustainable fine aggregate replacements in concrete, enhance prediction accuracy using ensemble ML approaches, and contribute to data-driven sustainable concrete design.

Literature review

Coal bottom ash and foundry sand as a sustainable material in concrete

Research into FS and CBA highlights both opportunities and challenges26,27. FS, due to its finer particle size and high silica content, often improves packing density and contributes to strength enhancement at moderate replacement levels (10–30%)28. Several studies have reported strength gains between 2 and 12% within this range29,30. However, excessive FS replacement increases water demand and porosity, negatively affecting workability and durability31,32,33. Similarly, CBA has been shown to enhance compressive strength up to 20% replacement, aided by its pozzolanic activity and ability to refine pore structure34,35,36. Beyond this level, however, its high porosity and inconsistent gradation tend to reduce strength and increase susceptibility to acid attack and shrinkage37,38. Overall, while both FS and CBA can partially replace natural sand with satisfactory performance, their variability and durability concerns limit large-scale adoption39,40,41,42,43. Importantly, most prior work has investigated these materials separately, leaving their combined influence underexplored.

Machine learning in FS and CBA concrete

ML has emerged as a powerful tool for predicting concrete strength, particularly when dealing with nonlinear effects introduced by industrial by-products. Table 1 summarizes the various ML models used to forecast the strength of concrete. Neural networks and support vector regressors have shown good predictive performance, while hybrid and ensemble models further improve accuracy and interpretability44,45,46,47,48. For example, FS-based concrete modelled using neural networks consistently identify curing age as a dominant predictor, while CBA-based studies highlight the importance of water-to-cement ratio and cement content. Yet, existing research remains fragmented: most studies analyze either FS or CBA in isolation, rely on relatively small datasets, or lack interpretability. Few have explored dual-waste systems under a unified ML framework. The present study addresses this gap by developing and benchmarking ensemble ML models for predicting compressive strength of concrete incorporating both FS and CBA.

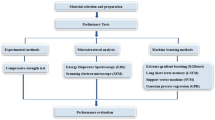

Materials and methods

Dataset description

With an emphasis on combinations that partially substitute natural fine aggregates with variable amounts of bottom ash sand and foundry sand, the data includes concrete mix designs, curing period and the accompanying compressive strength values. The mix proportions reported in the previously published studies were adopted, and the corresponding compressive strength values at different curing periods were considered, resulting in a total of 172 data entries 27,28,52,53,54,55. The dataset comprises a broad spectrum of concrete mixtures, reflecting diverse combinations of constituent materials, mix proportions, and curing conditions. With its own set of input parameters and corresponding compressive strength as the output variable, each record relates to a unique concrete mix design. The step-by-step methodology used in the current study is shown in Fig. 1.

The input features selected for model development based on their documented influence in prior studies and practical importance to concrete performance are detailed in Table 2. In particular, these are the contentious parameters of the study: cement content, fine aggregate (FA), coarse aggregate (CA), FS, and CBA contents, water content, water-cement (w/c) ratio, superplasticizer (SP), and curing duration. The output variable, compressive strength (CS), quantifies the concrete’s capacity to resist axial loading at a specified age.

Structurally, the dataset is organized in a tabular format, where each row represents a unique concrete mix and its corresponding CS measurement. All input variables are continuous numerical features, as is the output variable CS, which is expressed in megapascals (MPa). Each parameter in the dataset spans a large range of values, offering enough variety to efficiently train and verify machine learning models.

The selection of input parameters for model development was guided by two primary considerations, i.e. their physical relevance and established influence on concrete’s compressive strength based on prior experimental studies, and their availability and consistency across published datasets used to build the current data corpus. Cement content, water content, and w/c ratio were included due to their direct control over hydration, workability, and binder strength development. Fine and coarse aggregates represent the inert skeleton of concrete, influencing its packing density and load transfer characteristics. FS and CBA were specifically included as input features because they are the key sustainable replacement materials investigated in this study. Their replacement ratios significantly impact the microstructure and mechanical properties of concrete, particularly in terms of strength gain and porosity control. Superplasticizer dosage was considered because it affects the flowability and compaction of mixes with high replacement content or fine particles like FS. Curing duration was included due to its known role in influencing hydration progression and long-term strength development. All selected parameters are continuous variables and are commonly reported in concrete mix design literature, ensuring both practical relevance and compatibility with machine learning workflows.

Statistical description

The dataset utilised for ML summary statistics, such as mean, standard deviation, median, variance, skewness, kurtosis, and interquartile range, is shown in Table 3. With a standard deviation of 49.91 and a mean cement content of 396.78 kg/m3, there is significant variation in the cement proportions among the various mix proportions that are employed. A few samples may have less cement than the average, according to the modest negative skewness of − 0.29. The distribution of FA is symmetric, with a minor positive skewness of 0.25, showing that few samples have FA greater than the mean FA content. The mean of the FA was 518.53 kg/m3. The mean CA content is 1101.38 kg/m3, and the standard deviation of 169.30 kg/m3. The CA also has a small negative skewness of 1.46, but has the second highest variance in the dataset after the variance of FA content in the dataset. The average percentage of FS used to partially replace natural sand is 10.87%, with the dataset showing a slight positive skewness of 1.16. For CBA, the average replacement level is 9.7%, and the dataset exhibits a positive skewness of 2.95. The mean water content in the dataset is 196.91 kg/m3, with a relatively small skewness of 0.95. The w/c ratio’s volatility is quite low, indicating that the majority of concrete mixes maintain a constant w/c ratio. The w/c ratio has a standard deviation of 0.06 with a mean of 0.48, and its distribution shows a positive skewness of 0.43. Similarly, SP exhibits a small positive skewness of 1.65 and kurtosis of 1.97, which shows that certain samples have noticeably higher SP dosages.

This implies that mixes were designed with improved workability. The dataset is substantially skewed towards lower concrete ages, as indicated by the concrete age’s skewness of 1.57 and kurtosis of 1.28. The majority of the samples were evaluated at a moderate age of hydration and later at a well-hydrated age, as the maximum age is 365 days and the median age is 56 days. The output variable, CS shows a broad range of 13.45–63.3 MPa, with a mean of 35.47 MPa and a standard deviation of 10.77 MPa. The variability in CS across various mix designs is further demonstrated by the interquartile range of 14.74 MPa. The skewness values indicate that variables like FS and CBA exhibit moderate positive skewness, with long right tails, implying that higher substitution percentages are less frequently reported in literature-derived mixes. This asymmetry, along with kurtosis values slightly exceeding, suggests the presence of peaked distributions with occasional outliers. To ensure dataset integrity, the 172 mix records were collected from different peer-reviewed studies and checked for duplication based on composition, property values, and publication metadata. Any overlapping or repeated entries were removed. Despite the natural imbalance in the range of replacement levels (especially for FS and CBA), ensemble models are robust to such irregularities due to their internal handling of feature heterogeneity. These characteristics were further considered during model tuning and validation.

Although the dataset of 172 mixes was carefully curated from multiple peer-reviewed studies and duplicates were removed, certain limitations in representativeness must be acknowledged. The replacement levels of FS and CBA are unevenly distributed, with most mixes clustered below 20% substitution. Higher replacement levels (≥ 50%) are comparatively rare, which may constrain the generalizability of predictions for extreme substitution scenarios. Similarly, curing conditions are heterogeneous across studies, with a majority of mixes tested at standard ages (28–90 days) but fewer at long-term curing (≥ 180 days). Variability in material properties such as particle gradation, residual carbon in CBA, or binder coatings in FS also introduces heterogeneity, as these characteristics differ by source and processing methods. While ensemble ML models are robust to such imbalances and variability, these dataset characteristics highlight the importance of cautious interpretation when applying the trained models to untested ranges or region-specific materials. This transparency ensures that the model’s strengths are clear while also delineating the boundaries of its applicability.

Correlation analysis & data visualization

All variables’ histogram distributions are shown in Fig. 2, and underlying trends are revealed by superimposing Kernel Density Estimates on top. While variables like FS, CBA, SP, and curing days show significant concentrations close to zero, the distributions of cement, w/c ratio, and CS, for instance, show unimodal patterns, indicating that a sizable portion of samples lack these components. To explore the relationships among the variables, both Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients are computed, as defined in Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively. Spearman correlation is a non-parametric metric that captures monotonic associations and is more resilient to outliers and non-linear trends than Pearson correlation, which gauges the strength of linear relationships between two continuous variables.

Figure 3 presents heatmaps illustrating both Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients. In Fig. 3 (Left), the Pearson correlation analysis reveals that curing days exhibit the strongest positive correlation with CS (r = 0.45), followed by SP with a correlation of 0.21. On the other hand, a negative correlation of − 0.23 between CS and the w/c ratio suggests that greater w/c ratios typically result in lower CS, most likely as a result of bleeding and the interfacial transition zone being weaker. The Spearman correlation heatmap in Fig. 1 (Right) displays similar trends while also capturing non-linear, monotonic relationships, offering deeper insight into rank-based associations within the dataset.

Overall, the combined use of visualizations and correlation analyses provides a meaningful understanding of the data. The strong positive correlations observed for SP and curing duration underscore their significant role in enhancing strength development. In contrast, the negative correlation with water content highlights the adverse effects of excess water on concrete performance.

Data preprocessing

Treatment and outlier detection

The interquartile range (IQR) approach is used to find data points that significantly depart from the majority. It does this by using the difference between the first quartile (Q1) and the third quartile (Q3). Equation (3) provides the definition of IQR, and Eqs. (4) and (5) define the typical cutoffs for outlier detection.

Any data point falling outside the Lower Bound, Upper Bound is considered an outlier. To maintain the central tendency of the distribution and lessen significant distortions brought on by extreme values, these values are swapped out for the median of the associated feature.

Feature scaling and normalization

Preprocessing data is essential for improving predictive models’ resilience and performance. It guarantees that problems like inconsistent feature representations, outliers, and missing values are methodically fixed. The dataset is loaded into the analytical environment to start the preparation step. The target variable, CS, is isolated from the input parameters. To enable the model to learn from the majority of the data while being validated on previously unseen cases, the data is split into training and testing subsets using an 80:20 ratio, consisting of a total of 172 samples, with 138 samples allocated for training and 34 samples for testing. Feature scaling is a crucial step in getting data ready for deep learning regression models. Using the standard scaler technique, input features are adjusted to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one in order to prevent bias during training brought on by different feature magnitudes. Alternatively, normalization can be applied using Eq. (6), where each feature value is scaled to a [0, 1] range.

where x is the original value of the feature, min(x) and max(x) denote the feature’s minimum and maximum value, respectively.

Train-test split strategy

To ensure robust model evaluation and minimize overfitting, the dataset was partitioned using an 80:20 train-test split strategy. With this method, the dataset is divided at random so that 80% of it is utilised to train the ML models and 20% is set aside for evaluating how well they perform on hypothetical cases. In addition to ensuring that the models learn from a significant amount of data, this division offers an objective evaluation of the models’ capacity for generalization.

During the splitting process, the target variable CS was separated from the input features to maintain data integrity. To preserve the statistical distribution of the dataset, the splitting was performed using stratified sampling where necessary. This technique maintains the proportion of various input parameters across both the training and testing subsets, ensuring representativeness. The train-test split forms the basis for further steps such as feature scaling, hyperparameter tuning, and cross-validation, ultimately supporting the development of reliable and generalizable predictive models.

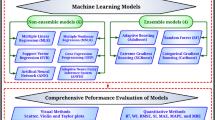

ML algorithm considered

The selection of ML algorithms in this study was based on their proven effectiveness in handling nonlinear, multivariable problems in material and structural engineering applications. Traditional models like Linear Regression (LR), Decision Tree Regressor (DTR), and Support Vector Regressor (SVR) were included as baseline models due to their interpretability and widespread use in regression analysis. However, these models often struggle to capture the complex, nonlinear interactions present in concrete mixtures with multiple variable replacements, such as FS and CBA. To address this limitation, ensemble methods such as Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosting (GBM), and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) were selected for their superior ability to model complex relationships through bagging and boosting strategies. Ensemble learners reduce overfitting, improve generalization, and have shown high predictive accuracy in previous studies related to concrete strength, asphalt mix design, and engineered cementitious composites. XGBoost, in particular, offers efficient training, regularization capabilities, and built-in feature importance analysis, making it a robust choice for this study. Additionally, models like Gaussian Process Regressor (GPR), Kernel Ridge (KR), and Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) were included to explore probabilistic learning, nonlinear kernel effects, and neural network architectures, respectively, ensuring a comprehensive model comparison.

Linear regression

By taking a linear approach, LR models the connection between input data and the target variable. Consider a dataset with n samples and p features, where each sample is represented as xi = (xi1,xi2,…,xip), and the corresponding target value is yi. The LR model is expressed as given in Eq. (7). Despite its simplicity and interpretability, linear regression often fails to capture complex nonlinear relationships. However, it is frequently used as a standard by which to measure the effectiveness of more complex models. The model parameters are estimated by minimizing the sum of squared residuals expressed as given in Eq. (8).

Here, \({\beta }_{0}\) denotes the intercept, and \({\beta }_{j}\) (for j = 1, 2, …., p) are the coefficients associated with each feature.

Decision tree regressor

The DTR constructs a tree-based structure, where each internal node represents a decision rule based on a specific feature, and each leaf node contains a predicted output value. The procedure usually employs a criterion, like variance reduction or mean squared error minimisation, to identify the best splits. At any given node, which contains a subset of the data D, the best split is chosen to maximize the improvement in prediction accuracy using Eq. (9).

Here, \({D}_{left}\) and \({D}_{right}\) represent the two partitions of dataset D, created based on whether the feature \({x}_{j}\) satisfies the condition \({x}_{j}\le t\) or \({x}_{j}\ge t\), respectively. While decision trees offer easily interpretable, rule-based structures, if hyperparameters like the minimum number of samples needed at a leaf node or the maximum tree depth are not appropriately set, they are prone to overfitting.

Random forest

A bootstrap sample of the original dataset and a randomly chosen subset of features are used to train each decision tree in the RF ensemble learning technique. This randomized training process reduces the correlation among individual trees, thereby enhancing prediction accuracy and increasing robustness to noise. The final production is obtained by averaging the output of all trees using Eq. (10).

where B denotes the total number of trees, and \({\widehat{y}}^{(b)}\) is the prediction made by the b-th tree. The bagging technique effectively lowers the variance and helps prevent overfitting, often outperforming a single decision tree.

Gradient boosting machines

The GBM uses error correction to gradually improve the model’s predictions, creating an additive ensemble of weak learners, often shallow decision trees.

The final predictive model can be expressed as Eq. (11).

where hm(x) is the weak learner at iteration m, η is the learning rate that controls the contribution of each learner, and M is the total number of iterations. According to Eq. (12), the new learner is trained to fit the loss function’s negative gradient with regard to the prior prediction at each stage.

Extreme gradient boosting

The XGBoost is an advanced implementation of the gradient boosting algorithm, designed for improved performance and efficiency. It enhances the training process by incorporating second-order derivatives (i.e., both gradients and Hessians) for more accurate optimization. Additionally, XGBoost introduces regularization terms to explicitly control model complexity, helping to prevent overfitting. A scoring function is added to the model. This regularization mechanism helps reduce overfitting by discouraging the formation of excessively complex trees. Furthermore, XGBoost is designed for high computational efficiency, leveraging parallel processing and optimized memory usage to achieve faster training compared to many other gradient boosting implementations.

Support vector regressor

With kernel functions, the SVR works effectively for managing non-linear interactions. SVR maintains a balance between model correctness and complexity while minimizing the error within a given margin. The mathematical formulation is given in Eq. (13).

where K \(\left({X}_{i},X\right)\) is the kernel function (radial basis function, polynomial), \({\alpha }_{i}\), \({\alpha }_{i}^{*}\) are Lagrange multipliers, \(b\) is the bias term. SVR effectively captures non-linear patterns but requires careful tuning of hyperparameters.

Gaussian process regressor

A non-parametric, Bayesian method of regression known as the GPR establishes a distribution over potential functions that could fit the data. GPR uses a probabilistic framework to describe data and assess prediction uncertainty, in contrast to parametric models that assume a fixed shape. Any finite set of function values has a joint Gaussian distribution, and it is assumed that the goal values are samples from a multivariate normal distribution. The covariance (or kernel) function k(x,x′), which expresses similarity between data points, serves as the basis for the prediction for a new input x ∗ . Common kernels include the Radial Basis Function, Matern, and Rational Quadratic. The GPR prediction consists of both a mean and a variance, offering a measure of confidence for each prediction. Because GPR can simulate complicated, nonlinear connections with defined uncertainty, it is especially helpful for small to moderate datasets. Large datasets may be limited by their computational complexity, which scales cubically with the number of training samples. Equation (14) provides the posterior predictive distribution for a test point.

where the mean μ ∗ and variance \({\sigma }_{*}^{2}\) depend on the training data, the kernel, and the observed noise.

Kernel ridge

In order to model nonlinear interactions between inputs and outputs, KR integrates the ideas of kernel techniques with ridge regression. While ridge regression applies L2 regularization to linear models to prevent overfitting by employing a kernel function to transfer the input data into a high-dimensional space, KR expands on this capability and makes it possible to identify intricate, nonlinear patterns. KR is computationally efficient for moderately sized datasets since it offers a closed-form solution in dual space. However, like other kernel methods, its performance may degrade on very large datasets due to the need to compute and invert large kernel matrices. The prediction function in KR is expressed as Eq. (15).

where αi are the dual coefficients, k(x,xi ) is the kernel function evaluating similarity between the test input x and each training instance xi.

Multi-Layer perceptron regressor

One kind of feedforward neural network is the MLP Regressor, which consists of an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer. Each layer consists of many neurons, each of which applies a nonlinear activation function σ(⋅) and calculates a weighted sum of its inputs. Equation (16) provides the prediction for an MLP with a single hidden layer. Backpropagation and a gradient-based method, such as stochastic gradient descent, are used to optimize the model parameters to minimize the loss function, which is typically the mean squared error (MSE) in regression tasks.

Here, W is the weight matrix of the hidden layer, b is the bias vector, σ is the activation function (typically ReLU), v is the output weight vector, and c is the output bias term.

Modal training, hyperparameter tuning, and cross validation

As explained in previous sections, the preprocessed dataset was separated into subsets for testing and training. The training set was used to train each model initially, and Bayesian optimization was used to adjust the hyperparameters. A final training run was carried out to produce the final version of each model after the ideal hyperparameters had been determined. The scikit-learn library in Python was used to create each model. For specific algorithms, such as Extreme Gradient Boosting, dedicated libraries like XGBoost were employed to leverage their optimized implementations. Predetermined tolerance limits for iterative solvers like SVR and a set number of maximum epochs for the MLP model were used to control convergence.

The optimization of hyperparameters plays a crucial role in adapting each machine learning model to the specific characteristics of the dataset, particularly considering the limited sample size and the non-linear relationships between inputs and outputs. In this study, a two-step hyperparameter tuning approach was employed. First, Grid Search was used as the primary method, conducting an exhaustive search across predefined parameter ranges, with each combination evaluated through fivefold cross-validation to ensure robust performance and minimize overfitting. Second, the search space was strategically defined based on domain expertise and prior studies in materials informatics and construction-related regression tasks, which helped narrow down the most promising parameter ranges and reduce computational effort. The final hyperparameter settings, presented in Table 4, were carefully selected to balance model complexity, generalization ability, and predictive accuracy. For instance, the maximum depth of the Random Forest model was constrained to avoid overfitting, while the learning rates in boosting algorithms were fine-tuned to promote stable and gradual learning.

Five-fold cross-validation was used to assess the model’s capacity for generalization. There were five roughly equal subsets (folds) created from the dataset. One-fold was utilized as the validation set and the other four as the training set for every iteration. To guarantee that every data point was used precisely once for validation, this procedure was carried out five times. The mean squared error across all folds was computed as shown in Eq. (17). To give a more thorough assessment of model performance, additional performance metrics were computed and averaged across the folds in addition to mean squared error. These metrics included the coefficient of determination, mean absolute error, mean absolute percentage error, and root mean squared error.

Evaluation metrics

Mean absolute error

Mean Absolute Error (MAE) is the average of the absolute differences between the predicted and actual values. Without taking into account the direction of the errors, it provides an estimate of the average size of the errors in a set of forecasts. MAE is a simple metric that shows how well predictions match actual data and is easy to understand. It was determined using Eq. (18).

Root mean square error

Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) measures the square root of the average of the squared differences between predicted and actual values. It is susceptible to outliers because it assigns greater weight to huge errors. When significant errors are undesired and require harsher penalties, RMSE is very helpful. It is determined using Eq. (19).

Coefficient of correlation

Coefficient of correlation (R2) represents the proportion of variance in the target variable that is explained by the model. It has a range of 0–1, where 1 denotes a perfect fit and 0 denotes no variation explained by the model. A popular statistic for assessing the goodness of fit in regression tasks is R2. It is determined using Eq. (20).

Mean absolute percentage error

Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) measures the average percentage error between predicted and actual values, making it intuitive and easy to interpret in percentage terms. Lower MAPE indicates better model accuracy. However, it is sensitive when actual values are close to zero. It is determined using Eq. (21).

Coefficient of variation of RMSE

Coefficient of Variation of RMSE (CVRMSE) expresses RMSE as a percentage of the mean actual value, allowing comparison across datasets with different scales determined using Eq. (22). More prediction accuracy in relation to the data scale is shown by a lower CVRMSE. Useful for comparing model performance across different datasets.

Results and discussion

Model performance comparison

The performance of ML models developed with the MAE (MPa), RMSE (MPa), R2, MAPE (%), and CVRMSE (%) reported in the current study is shown in Table 5. Ensemble models clearly outperformed traditional learners, confirming their suitability for nonlinear material interactions. XGBoost achieved the highest accuracy (R2 = 0.983, RMSE = 1.54 MPa, MAPE = 3.47%), followed closely by GBM and RF. In contrast, linear regression and SVR underperformed, underscoring the limitations of simpler models when dealing with multi-variable, waste-based concrete systems. These disparities emphasize the ensemble models’ ability to capture nonlinear relationships and complex interactions between mix parameters and capabilities that simpler models lack. Visual interpretation through scatter plots of actual versus predicted compressive strength values further supports these quantitative outcomes, as shown in Fig. 4. In the case of XGBoost and GBM, the data points are closely clustered around the diagonal, indicating strong agreement between predicted and measured values across the entire strength range. In contrast, simpler baselines such as LR, KR, and SVR showed poor alignment with the dataset, underscoring their limited applicability to multi-variable, waste-based concretes.

In addition to conventional performance metrics, a Taylor diagram (Fig. 5) was used to visually compare the performance of the nine ML models. The proximity of a model’s marker to the reference point (representing the actual observations) indicates better performance. As shown in Fig. 5, the XGBoost model demonstrates the highest correlation and minimal distance from the observed values, confirming its superior accuracy and consistency. GBM and RF also exhibit favourable positions close to the reference point, whereas traditional models like SVR, LR, and KR are positioned further away, indicating lower performance. The Taylor diagram reinforces the ensemble models’ ability to capture complex nonlinear relationships in FS and CBA concrete.

Interpretation of results

The superior performance of ensemble methods confirms their suitability for predicting the strength of dual-waste concretes. Among them, XGBoost and GBM demonstrated nearly identical and exceptionally high predictive accuracy, while RF also provided robust results with slightly lower precision. These findings highlight the ability of ensemble approaches to balance bias and variance, capture nonlinear effects, and provide feature importance insights that aid in mix optimization. To further evaluate the error distribution and bias of the XGBoost predictions, the residuals were plotted as shown in Fig. 6.

Further insight into model robustness was gained by examining the residual error distribution of the XGBoost model. The residuals were symmetrically distributed around zero, forming a pronounced peak near the center, which signifies minimal systematic bias and strong generalization capability. This residual pattern corroborates the model’s low RMSE and MAE, confirming that prediction errors are generally small and randomly distributed rather than systematic. In contrast, residual plots for simpler models (not shown here) typically exhibited skewness or wider spreads, reflecting a consistent tendency to either overpredict or underpredict certain strength ranges.

Compared to existing machine learning models in concrete strength prediction, the proposed XGBoost ensemble model offers several distinctive advantages. First, it delivers substantially higher accuracy, achieving an R2 of 0.983 and RMSE of just 1.54 MPa, surpassing the performance of traditional models like ANN, SVR, and RF previously applied to similar datasets. Second, it is one of the first studies to jointly model the effects of both FS and CBA as dual replacements for natural sand, capturing nonlinear synergies that were overlooked in earlier single replacement models. Third, the model includes intrinsic feature importance metrics, enabling informed decisions about mix optimization by ranking key parameters like curing duration, superplasticizer dosage, and binder content. Additionally, the integration of Bayesian optimization ensures that the hyperparameters are fine-tuned for generalization, making the model not only accurate but also robust. These advantages collectively demonstrate the practical value of ensemble learning for mix design in sustainable concrete, offering a significant improvement over conventional data-driven approach.

Feature importance analysis

The feature important analysis results across different ML models used is shown in Fig. 7, which provides vital insights into the roles played by various input parameters in predicting the CS of concrete incorporating FS and CBA. The dominance of curing duration, superplasticizer dosage, and cement content in feature importance aligns with fundamental concrete science, while highlighting the need for tailored mix design in dual-waste concretes. FS and CBA contributed meaningfully but conditionally, with their influence strongly mediated by binder content and curing. This reinforces that while sustainable by-products can partially replace natural sand, their performance depends on optimized design strategies. Figure 8 shows the feature importance heatmap of different ML models. It was noticed from Fig. 8 that XGBoost and GBM provided similar importance distributions, both emphasizing curing days more, followed by SP dosage, cement content, w/c ratio, and then sustainable sands, i.e., FS and CBA. On the other hand, RF assigned slightly more weight to FS and CBA than boosting models, possibly due to its bagging structure, which better handles variable interactions and outliers. Also, DTR and MLP displayed more distributed feature weightings, but still emphasized curing and binder-related features. LR and SVR lacked meaningful interpretability due to poor predictive alignment with nonlinear feature interactions.

Factors contributing to the superior performance of ensemble methods

The superior predictive performance of ensemble models, particularly XGBoost and GBM, can be explained by their innate capacity to represent intricate nonlinearities and interaction effects in the data. Boosting algorithms sequentially build new models that focus on correcting errors made by prior models, leading to progressive error reduction and improved accuracy. XGBoost further enhances this process through advanced regularization techniques (L1 and L2 penalties) that prevent overfitting, making it especially suitable for datasets of limited size. Bagging, which lowers variance by training several trees on bootstrap samples and averaging their results, is advantageous for RF, leading to smoother predictions. In contrast, simpler models like LR inherently assume linearity, making them unsuitable for datasets where variables like FS and CBA content affect strength in nonlinear ways depending on replacement levels, curing conditions, and interactions with other parameters.

Complementary insights were obtained from correlation analysis visualized through Pearson and Spearman heatmaps. Curing days and compressive strength showed a moderately positive correlation (r = 0.45), whereas superplasticizer dosage showed a lower positive correlation (r = 0.21), according to the Pearson analysis. A negative correlation with water-to-cement ratio (r = − 0.23) highlights the detrimental effect of excess water on concrete strength. Spearman analysis, being rank-based, detected similar trends and reinforced the observation that longer curing and higher superplasticizer dosages consistently improve strength, regardless of precise numerical values.

Overall, these results underline critical practical implications. AI-driven ensemble models like XGBoost can accurately predict compressive strength in concrete mixes incorporating FS and CBA, thus enabling practitioners to design sustainable concrete more efficiently and reliably. The findings encourage the safe adoption of FS and CBA as partial natural sand replacements, thereby reducing environmental impact and supporting circular economy goals. Furthermore, by identifying the most influential mix parameters, such models can guide targeted optimization, reducing the reliance on costly and time-intensive experimental testing.

Comparison with existing studies

Previous ML studies on FS or CBA concretes achieved reasonable predictive accuracy but lacked dual-material modeling or systematic hyperparameter tuning. By integrating FS and CBA within a single dataset, applying ensemble models, and using Bayesian optimization, the present study advances methodological rigor and demonstrates higher accuracy than previously reported approaches. This provides new evidence supporting the practical use of FS and CBA in sustainable concrete, guided by AI-driven mix optimization. Ullah et al. studied the ensemble ML approach with the traditional ML approach for the prediction of CS of sustainable foam concrete, and it was noticed that the modified ensemble learner, i.e., RF, outperformed all models by yielding a strong correlation of 0.96 along with the lowest MAE and RMSE of 1.84 MPa and 2.52 MPa, respectively56. Farooq et al. studied similar ensemble learners with bagging and boosting in the prediction of CS of high-performance concrete, and it was observed that employing bagging and boosting learners improves individual model responsiveness. Overall, RF and DTR with bagging give robust performance of the models with a correlation of 0.92 with a minimum error57. Gil et al. studied the different ensemble methods to predict the CS of recycled aggregate concrete, and the result indicates that random forest and gradient boosting models have strong potential to predict the CS of self-compacting recycled aggregate concrete with correlation values of 0.7128 and 0.6948, respectively24. In order to forecast the mechanical properties of geopolymer concrete, Amin et al. investigated ensemble and non-ensemble machine learning techniques. The findings showed that ensemble approaches performed significantly better than non-ensemble algorithms. Typically, RF yielded robust performance by achieving a better correlation of 0.93, and the lowest statistical errors58.

The findings of this study also align with and extend previous research on ML-based prediction of concrete strength using industrial by-products. For instance, Kazemi et al. demonstrated that incorporating sustainable materials such as FS in ML models can achieve high prediction accuracy (R2 > 0.9) using hybrid models, which parallels our strong R values using ensemble regressors49. Similarly, Ashraf et al. highlighted the superiority of hybrid SVR models in predicting the strength property of the CBA incorporated concrete, which is consistent with our results showing the effectiveness of hyperparameter-tuned tree-based ensembles48. Furthermore, our use of Bayesian optimization adds a novel dimension to prior work, such as Nhat-Duc et al., who employed an optimization technique with GBM for FS incorporated concrete, but did not report systematic parameter tuning50. By applying Bayesian search, our study addresses reproducibility concerns and model generalization performance more rigorously. The use of Spearman and Pearson correlation analysis before modelling further enhances reliability, as similarly advocated by Javed et al. in their study of ML in the prediction of FS incorporated concrete14. Thus, our work not only confirms findings from existing literature but also advances the methodological framework by integrating ensemble learning with robust feature selection and hyperparameter tuning, tailored to the context of concrete with FS and CBA.

Practical recommendations

A thorough analysis of ML produced for the prediction of the CS of sustainable sand concrete is part of the current work. Practitioners can apply ensemble ML tools such as XGBoost and GBM to optimize concrete with FS and CBA, but should limit substitutions to moderate levels (FS ≤ 30%, CBA ≤ 20%) unless additional durability testing is performed. Special attention should be given to curing duration and superplasticizer dosage, as these strongly govern strength outcomes in modified concretes. These insights allow engineers to reduce experimental trial-and-error while advancing sustainable material use. From a practical perspective, the results suggest that safe and effective replacement levels for FS are typically up to 20–30%, while CBA can be used satisfactorily up to 15–20% as a partial sand substitute. Within these ranges, compressive strength comparable to or higher than control mixes has been consistently reported in prior studies and supported by our feature importance analysis, which highlights curing duration, superplasticizer dosage, and binder content as critical design parameters. Higher replacement levels, although occasionally explored, remain less reliable due to increased porosity and reduced durability, particularly under aggressive exposures. The findings therefore support cautious use of FS and CBA within moderate substitution levels to promote sustainability without compromising performance.

Conclusion

This article assessed studies focusing on feature importance and the ability of machine learning algorithms to predict the mechanical properties of sustainable sand concrete. The main conclusions are summarised as follows:

-

Among all tested models, ensemble methods, particularly XGBoost (R2 = 0.983, RMSE = 1.54 MPa) and GBM (R2 = 0.982), demonstrated the highest accuracy and generalisation capability.

-

Traditional models such as SVR and LR were unable to capture the complex nonlinear relationships in concrete mix design, resulting in lower predictive performance (R2 = 0.702 and 0.453, respectively).

-

According to feature importance analysis, the most important variables influencing compressive strength were cement content, w/c ratio, curing time, and superplasticizer dosage.

-

The findings confirm that artificial intelligence-driven ensemble models can effectively support sustainable concrete design by accurately predicting strength even when using industrial by-products like FS and CBA.

-

By showing the useful advantages of incorporating ML into mix design workflows, this study advances data-driven concrete technology.

This study makes a significant theoretical contribution by demonstrating the superior performance of ensemble ML algorithms, particularly XGBoost, in capturing the complex nonlinear relationships governing compressive strength in sustainable concrete mixes incorporating FS and CBA. Unlike conventional models, ensemble methods successfully identified and quantified the dominant influence of key parameters such as curing duration, superplasticiser dosage, and binder content. The analysis confirms that replacing natural fine aggregates with FS and CBA not only supports sustainable construction but also introduces unique data patterns that are best understood through advanced ML models. These findings contribute to the growing body of knowledge on artificial intelligence-assisted concrete technology by validating ensemble methods as reliable tools for predicting performance in multi-variable, industrial waste-based concrete systems.

From a practical perspective, the results of this research can be directly applied by civil engineers, material scientists, and ready-mix concrete producers involved in sustainable construction. The developed XGBoost-based prediction model allows practitioners to estimate compressive strength accurately without extensive laboratory testing, thereby reducing time, cost, and environmental impact. Construction professionals aiming to implement circular economy principles by replacing natural sand with industrial byproducts can use the model as a decision-support tool for mix design optimisation. Moreover, policymakers and environmental agencies promoting waste valorisation can leverage these insights to encourage the adoption of FS and CBA in structural grade concrete.

Limitations and future research directions

While the proposed ML framework demonstrated high accuracy in predicting compressive strength of concrete with foundry sand and coal bottom ash, the study has certain limitations. The dataset used was compiled from multiple published sources, which may have introduced variability due to differences in mix design procedures, testing conditions, and material properties across studies. Additionally, the dataset size, although sufficient for training, could limit the model’s generalizability, particularly for underrepresented mix ranges or local material variations. Another constraint is the focus solely on compressive strength prediction. Other important performance parameters, such as tensile strength, flexural strength, shrinkage, and durability indicators, were not considered due to the unavailability of consistent data. Furthermore, while machine learning models like XGBoost provided excellent predictive performance, the study did not include experimental validation or real-time deployment of the model, which would be necessary for full practical adoption.

Future studies should expand the scope of ML applications to include other mechanical and durability properties, such as tensile strength, flexural strength, shrinkage, and chloride ion penetration resistance in FS and CBA concrete. There is also potential for integrating hybrid metaheuristic algorithms to optimize not just prediction but also mix proportioning under performance and cost constraints. Furthermore, developing explainable artificial intelligence can enhance trust and interpretability of the results, making them more accessible for practical deployment. Lastly, experimental validation using region-specific FS and CBA sources can be explored to ensure generalizability and adaptiveness of the model across diverse geographical and material conditions. Another important limitation is the absence of external validation. While cross-validation and Bayesian optimization ensured robustness within the compiled dataset, the model has not yet been tested on new experimental data or region-specific FS/CBA sources. This restricts immediate generalizability and highlights the need for future experimental validation.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request by Mr. Sagar Paruthi, Email id: sparuthi57@gmail.com.

References

Paruthi, S., Rahman, I., Khan, A. H., Sharma, N. & Alyaseen, A. Strength, durability, and economic analysis of GGBS-based geopolymer concrete with silica fume under harsh conditions. Sci. Rep. 14, 31572 (2024).

Ingalkar, R. S. & Harle, S. M. Replacement of natural sand by crushed sand in the concrete. Landscape Archit. Region. Plann. 2, 13–22 (2017).

Paruthi, S. et al. Leveraging silica fume as a sustainable supplementary cementitious material for enhanced durability and decarbonization in concrete. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2025, 5513764 (2025).

Bhoopathy, V. & Subramanian, S. S. The way forward to sustain environmental quality through sustainable sand mining and the use of manufactured sand as an alternative to natural sand. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29, 30793–30801 (2022).

Paruthi, S., Khan, A. H., Isleem, H. F., Alyaseen, A. & Mohammed, A. S. Influence of silica fume and alccofine on the mechanical performance of GGBS-based geopolymer concrete under varying curing temperatures. J. Struct. Integr. Mainten. 10, 2447661 (2025).

Bhardwaj, B. & Kumar, P. Waste foundry sand in concrete: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 156, 661–674 (2017).

Kumar, S., Silori, R. & Sethy, S. K. Insight into the perspectives of waste foundry sand as a partial or full replacement of fine aggregate in concrete. Total Environ. Res. Themes 6, 100048 (2023).

Hamada, H., Alattar, A., Tayeh, B., Yahaya, F. & Adesina, A. Sustainable application of coal bottom ash as fine aggregates in concrete: A comprehensive review. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 16, e01109 (2022).

Manoharan, T., Laksmanan, D., Mylsamy, K., Sivakumar, P. & Sircar, A. Engineering properties of concrete with partial utilization of used foundry sand. Waste Manage. 71, 454–460 (2018).

Tangadagi, R. B. & Ravichandran, P. Performance evaluation of cement mortar prepared with waste foundry sand as an alternative for fine aggregate: a sustainable approach. Iran. J, Sci., Tran. Civ. Eng. 49, 1937–1951 (2025).

Singh, N., Mithulraj, M. & Arya, S. Influence of coal bottom ash as fine aggregates replacement on various properties of concretes: A review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 138, 257–271 (2018).

Paruthi, S. et al. A review on material mix proportion and strength influence parameters of geopolymer concrete: Application of ANN model for GPC strength prediction. Constr. Build. Mater. 356, 129253 (2022).

Paruthi, S., Rahman, I. & Husain, A. Comparative studies of different machine learning algorithms in predicting the compressive strength of geopolymer concrete. Comput. Concr. 32, 607–613 (2023).

Javed, M. F. et al. Comparative analysis of various machine learning algorithms to predict strength properties of sustainable green concrete containing waste foundry sand. Sci. Rep. 14, 14617 (2024).

Kumari, P., Paruthi, S., Alyaseen, A., Khan, A. H. & Jijja, A. Predictive performance assessment of recycled coarse aggregate concrete using artificial intelligence: A review. Clean. Mater. 13, 100263 (2024).

Asif, U., Khan, W. A., Naseem, K. A. & Rizvi, S. A. S. Enhancing the predictive accuracy of marshall design tests using generative adversarial networks and advanced machine learning techniques. Mater. 45, 112379 (2025).

Alahmari, T. S. & Farooq, F. Novel approaches in prediction of tensile strain capacity of engineered cementitious composites using interpretable approaches. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 64, 20250088 (2025).

Dong, J., Wang, Q., Guan, Z. & Chai, H. High-temperature behaviour of basalt fibre reinforced concrete made with recycled aggregates from earthquake waste. J. Buildi. Eng. 48, 103895 (2022).

Kang, F., Han, S., Salgado, R. & Li, J. System probabilistic stability analysis of soil slopes using Gaussian process regression with Latin hypercube sampling. Comput. Geotech. 63, 13–25 (2015).

Chen, D., Kang, F., Li, J., Zhu, S. & Liang, X. Enhancement of underwater dam crack images using multi-feature fusion. Autom. Constr. 167, 105727 (2024).

Dong, J.-F., Wang, Q.-Y. & Guan, Z.-W. Material and structural response of steel tube confined recycled earthquake waste concrete subjected to axial compression. Mag. Concr. Res. 68, 271–282 (2016).

Dong, J., Xu, Y., Guan, Z. & Wang, Q. Freeze-thaw behaviour of basalt fibre reinforced recycled aggregate concrete filled CFRP tube specimens. Eng. Struct. 273, 115088 (2022).

Li, Q. & Song, Z. Prediction of compressive strength of rice husk ash concrete based on stacking ensemble learning model. J. Clean. Prod. 382, 135279 (2023).

Gil, J., Palencia, C., Silva-Monteiro, N. & Martínez-García, R. To predict the compressive strength of self compacting concrete with recycled aggregates utilizing ensemble machine learning models. Case Stud. Const. Mate. 16, e01046 (2022).

Salami, B. A. et al. Estimating compressive strength of lightweight foamed concrete using neural, genetic and ensemble machine learning approaches. Cement Concr. Compos. 133, 104721 (2022).

Ahmad, J., Aslam, F., Zaid, O., Alyousef, R. & Alabduljabbar, H. Mechanical and durability characteristics of sustainable concrete modified with partial substitution of waste foundry sand. Struct. Concr. 22, 2775–2790 (2021).

Aggarwal, Y. & Siddique, R. Microstructure and properties of concrete using bottom ash and waste foundry sand as partial replacement of fine aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 54, 210–223 (2014).

Siddique, R., De Schutter, G. & Noumowe, A. Effect of used-foundry sand on the mechanical properties of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 23, 976–980 (2009).

Siddique, R., Aggarwal, Y., Aggarwal, P., Kadri, E.-H. & Bennacer, R. Strength, durability, and micro-structural properties of concrete made with used-foundry sand (UFS). Constr. Build. Mater. 25, 1916–1925 (2011).

de Barros Martins, M. A., Barros, R. M., Silva, G. & dos Santos, I. F. S. Study on waste foundry exhaust sand, WFES, as a partial substitute of fine aggregates in conventional concrete. Sustain. Cities Soc. 45, 187–196 (2019).

Kaur, G., Siddique, R. & Rajor, A. Influence of fungus on properties of concrete made with waste foundry sand. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 25, 484–490 (2013).

Kaur, G., Siddique, R. & Rajor, A. Micro-structural and metal leachate analysis of concrete made with fungal treated waste foundry sand. Constr. Build. Mater. 38, 94–100 (2013).

Bilal, H. et al. Performance of foundry sand concrete under ambient and elevated temperatures. Materials 12, 2645 (2019).

Kumar, D., Gupta, A. & Ram, S. Uses of bottom ash in the replacement of fine aggregate for making concrete. Int. J. Curr. Eng. Technol. 4, 3891–3895 (2014).

Muthusamy, K. et al. in IOP Conference series: materials science and engineering. 012099 (IOP Publishing).

Kim, H.-K. & Lee, H.-K. Use of power plant bottom ash as fine and coarse aggregates in high-strength concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 25, 1115–1122 (2011).

Lee, H.-K., Kim, H.-K. & Hwang, E. Utilization of power plant bottom ash as aggregates in fiber-reinforced cellular concrete. Waste Manage. 30, 274–284 (2010).

Thomas, J., Thaickavil, N. N. & Wilson, P. Strength and durability of concrete containing recycled concrete aggregates. J. Build. Eng. 19, 349–365 (2018).

Ghosh, R., Gupta, S. K., Kumar, A. & Kumar, S. Durability and mechanical behavior of fly ash-GGBFS geopolymer concrete utilizing bottom ash as fine aggregate. Trans. Indian Ceram. Soc. 78, 24–33 (2019).

Yüksel, İ, Bilir, T. & Özkan, Ö. Durability of concrete incorporating non-ground blast furnace slag and bottom ash as fine aggregate. Build. Environ. 42, 2651–2659 (2007).

Hamzah, A. Durability of self-compacting concrete with coal bottom ash as sand replacement–Material under aggressive environment. Doctoral dissertation, Universiti Tun Hussein Onn Malaysia) (2017).

Abubakar, A. U. & Baharudin, K. S. Properties of concrete using tanjung bin power plant coal bottom ash and fly ash. Int. J. Sustain. Construct. Eng. Technol. 3, 56–69 (2012).

Wongsa, A., Zaetang, Y., Sata, V. & Chindaprasirt, P. Properties of lightweight fly ash geopolymer concrete containing bottom ash as aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 111, 637–643 (2016).

Mehta, V. Machine learning approach for predicting concrete compressive, splitting tensile, and flexural strength with waste foundry sand. J. Build. Eng. 70, 106363 (2023).

Tavana Amlashi, A. et al. AI-based formulation for mechanical and workability properties of eco-friendly concrete made by waste foundry sand. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 33, 04021038 (2021).

Siddique, R., Aggarwal, P. & Aggarwal, Y. Prediction of compressive strength of self-compacting concrete containing bottom ash using artificial neural networks. Adv. Eng. Softw. 42, 780–786 (2011).

Aneja, S., Sharma, A., Gupta, R. & Yoo, D.-Y. Bayesian regularized artificial neural network model to predict strength characteristics of fly-ash and bottom-ash based geopolymer concrete. Materials 14, 1729 (2021).

Ashraf, M. W. et al. Experimental and explainable machine learning based investigation of the coal bottom ash replacement in sustainable concrete production. J. Build. Eng. 104, 112367 (2025).

Kazemi, R., Golafshani, E. M. & Behnood, A. Compressive strength prediction of sustainable concrete containing waste foundry sand using metaheuristic optimization-based hybrid artificial neural network. Struct. Concr. 25, 1343–1363 (2024).

Nhat-Duc, H. & Quoc-Lam, N. Towards sustainable construction: estimating compressive strength of waste foundry sand-blended green concrete using a hybrid machine learning approach. Discov. Civ. Eng. 2, 42 (2025).

Guirado, E., Ruiz Martinez, J. D., Campoy, M. & Leiva, C. Properties and optimization process using machine learning for recycling of fly and bottom ashes in fire-resistant materials. Processes 13, 933 (2025).

Prabhu, G. G., Hyun, J. H. & Kim, Y. Y. Effects of foundry sand as a fine aggregate in concrete production. Constr. Build. Mater. 70, 514–521 (2014).

Siddique, R., Singh, G., Belarbi, R. & Ait-Mokhtar, K. Comparative investigation on the influence of spent foundry sand as partial replacement of fine aggregates on the properties of two grades of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 83, 216–222 (2015).

Rafieizonooz, M., Mirza, J., Salim, M. R., Hussin, M. W. & Khankhaje, E. Investigation of coal bottom ash and fly ash in concrete as replacement for sand and cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 116, 15–24 (2016).

Al-Fasih, M. Y. M., Ibrahim, M. H. W., Basirun, N. F., Jaya, R. P. & Sani, M. Influence of partial replacement of cement and sand with coal bottom ash on concrete properties. Carbon (C) 3, 0.10 (2019).

Ullah, H. S. et al. Prediction of compressive strength of sustainable foam concrete using individual and ensemble machine learning approaches. Materials 15, 3166 (2022).

Farooq, F., Ahmed, W., Akbar, A., Aslam, F. & Alyousef, R. Predictive modeling for sustainable high-performance concrete from industrial wastes: A comparison and optimization of models using ensemble learners. J. Clean. Prod. 292, 126032 (2021).

Amin, M. N. et al. Prediction of mechanical properties of fly-ash/slag-based geopolymer concrete using ensemble and non-ensemble machine-learning techniques. Materials 15, 3478 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the funding of the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, Jazan University, Saudi Arabia, through project number: (JU-202505352-DGSSR-ORA-2025).

Funding

There is no funding for the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sagar Paruthi: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Rashmi Verma: Writing—review & editing, Methodology, Validation, Visualization. Neha Sharma: Writing—review & editing. Afzal Husain Khan: Writing—review & editing. Mohd Abul Hasan: Writing—review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Paruthi, S., Verma, R., Sharma, N. et al. Ensemble machine learning models for predicting strength of concrete with foundry sand and coal bottom ash as fine aggregate replacements. Sci Rep 15, 38331 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22212-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22212-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Integrated hybrid machine learning and metaheuristic approach: optimizing green-surfactant stabilized nano-silica cement composites for structural applications

Journal of Building Pathology and Rehabilitation (2026)

-

Machine learning-assisted evaluation of flexural strength of FRP-confined concrete beams: experimental and ANSYS APDL study

Asian Journal of Civil Engineering (2026)