Abstract

Kirkia tenuifolia Engl. (family Kirkiaceae) is traditionally used to treat cholera, alleviate thirst, and serves as an important water source and livestock feed in arid regions. However, to date, no scientific study has been conducted on its chemical composition and pharmacological properties. Therefore, the present study aimed to isolate and identify the chemical constituents from the stem bark of Kirkia tenuifolia Engl and evaluate their pharmacological activities. Silica gel chromatographic separation of the methanol extract afforded nine compounds (1–9), identified herein for the first time from this species. Among them, lupeol (2) exhibited notable antibacterial activity with an MIC of 0.625 mg/mL against E. coli, S. typhi, and P. aeruginosa. Dimethylfraxetin (5), urolithin M5 (6) and urolithin M5 (7) showed antibacterial activity with an MIC of 0.625 mg/mL against E. coli and P. aeruginosa. Compounds 2, 5, 6, and 7 demonstrated potent antioxidant activities in the DPPH assay, with IC₅₀ values ranging from 2.58 to 9.00 µg/mL. The methanol extract showed significant cytotoxicity against MCF-7 breast cancer cells (34.96% viability at 200 µg/mL) and antiviral activity against influenza A (H1N1) (CC₅₀ = 39.8, IC₅₀ = 4.2 µg/mL, SI = 9.1). Molecular docking revealed that compound 7 exhibited higher binding affinities with S. aureus pyruvate kinase (-7.2 kcal/mol) and L. monocytogenes receptor (-7.4 kcal/mol) compared to ciprofloxacin (-5.6 and − 6.2 kcal/mol, respectively). Lupeol (2) showed stronger binding to Prdx5 (-6.1 kcal/mol) than ascorbic acid (-5.2), while compounds 2, 5, 6, and 7 bound more strongly to human myeloperoxidase (-7.4 to -8.6) than ascorbic acid (-4.8). These findings support the therapeutic potential of Kirkia tenuifolia Engl, but further studies are needed to confirm its effects against diverse pathogens and cell lines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nowadays, a significant number of higher plants have been cultivated worldwide to obtain valuable substances for use in medicine and pharmacy1. The pharmacological properties of plants have led to the development of natural product-derived drugs, harnessing the medicinal benefits of various species. Even before the 18th century, the medicinal activities of many plants, their effects on human health, and their mechanisms of action were recognized2. Today, both developing and developed countries are witnessing a growing demand for herbal plants as sources of drugs, nutraceuticals, beverages, and cosmetics3. Due to their natural origin, herbal medicines are widely preferred over synthetic drugs by many people around the world. These herbal remedies are known for their therapeutic efficacy, safety, minimal side effects, cost-effectiveness, and availability in local communities4. Natural product chemists continue to purify and characterize herbal formulations and traditional decoctions used by indigenous communities in the quest for new bioactive compounds5. The therapeutic value of medicinal plants is primarily attributed to the diverse array of chemical constituents they contain. Therefore, identifying and predicting the pharmacological basis of traditionally used plants is crucial for the development of modern drugs6.

Kirkia tenuifolia Engl. (family Kirkiaceae) is native to eastern and southern Ethiopia, extending to central and eastern Kenya. It is a shrub or small tree that primarily grows in desert and dry shrubland biomes7. The plant is well adapted to arid environments, with swollen roots that serve as an important water source during drought periods8,9. In Somalia, a decoction prepared from its bark is traditionally consumed for the treatment of cholera, and the bark is also chewed to relieve thirst9. Kirkia tenuifolia Engl. (Figure. 1) is a resilient and visually distinctive species, valued both for its drought tolerance and its ornamental appeal. It thrives in poor soils and requires minimal maintenance once established. In addition to its landscape value, it holds cultural and medicinal significance. It is traditionally used for cholera treatment and thirst alleviation, and it plays a role in local ecosystems by attracting pollinators such as bees and butterflies10. Various parts of the plant are also browsed by livestock11,12. However, despite its ethnobotanical importance, the phytochemical and pharmacological properties of Kirkia tenuifolia Engl. have not yet been investigated. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the antioxidant, antibacterial, antiviral, and antiproliferative activities of stem bark methanol extract of Kirkia tenuifolia Engl. and their chemical constituents through an integrated experimental and computational approach.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and instruments

NMR spectra were measured in CDCl3 and CD3OD solvents and TMS as an internal standard using a Bruker Avance 400 MHz spectrometer. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on pre-coated aluminum plates Merck, Germany, silica gel GF254, and the compounds were observed under UV light at 254 and 365 nm. Silica gel (100–200 mesh mesh size) was utilized for the separation of compounds through Column chromatography. Absorbance of DPPH assay was read at 517 nm using a double-beam UV-Vis spectrophotometer (UV-1800, Shimadzu). Analytical-grade (≥ 99.8% purity) and HPLC-grade (≥ 99.8% purity) methanol, ethyl acetate, chloroform, dichloromethane, and n-hexane solvents were purchased from LOBA CHEMIE PVT. LTD., India.

Plant materials collection and identification

The stem bark of Kirkia tenuifolia Engl. was collected in October 2023 from Moyale, Ethiopia. The plant was identified and authenticated by senior botanist Melaku Wondafrash, and a voucher specimen (GN003) was deposited at the National Herbarium of Ethiopia, Department of Plant Biology and Biodiversity Management, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa.

Extraction and isolation of compounds

The powdered stem barks of Kirkia tenuifolia Engl. (1 kg) were extracted by maceration with methanol (5 L × 2) for 48 h each with continuous shaking using a mechanical shaker (Fig. 2). The extracts were filtered through Whatman No. 1 filter paper and concentrated under reduced pressure at 40 °C using a rotary evaporator (R-300, Büchi, Switzerland), yielding 52 g of crude methanol extract. Preliminary TLC analysis of the crude extract using n-hexane/ethyl acetate (6:4) as the eluent under UV light (254 and 365 nm) showed a promising profile. A portion of the crude extract (25 g) was adsorbed onto an equal weight of silica gel (25 g, 100–200 mesh) and subjected to column chromatography over silica gel (200 g) using gradient elution with n-hexane/ethyl acetate and chloroform/methanol, yielding 230 fractions (50 mL each)13. Fractions 17–30 (eluted with n-hexane/EtOAc 9:1, 120 mg) were combined and further purified by silica gel column chromatography using a gradient of EtOAc in n-hexane as eluent, affording 33 subfractions. Subfraction 27 showed a single spot on TLC (n-hexane/EtOAc, 8:2) and gave compound 1 (24.5 mg). Fractions 40–65 (n-hexane/EtOAc, 8:2, 215 mg) were combined and re-chromatographed on silica gel with an increasing gradient of EtOAc in n-hexane as eluent, yielding 20 subfractions. Subfractions 13–15 were combined and afforded compound 2 (22.1 mg). Fractions 70–94 (n-hexane/EtOAc, 7:3, 143.6 mg) were pooled and purified via silica gel column chromatography, yielding 25 subfractions. Subfraction 22 gave mixture of compounds 3 and 4 (41.5 mg), respectively. Fractions 103–134 (n-hexane/EtOAc 6:4, 285 mg) were combined and further chromatographed, yielding 15 subfractions. Subfraction 10 yielded compound 5 (18.7 mg). Fractions 138–170 (n-hexane/EtOAc 1:1, 316.5 mg) were combined and purified on silica gel using a similar gradient, yielding 37 subfractions. Subfractions 23–27 were combined and subjected to preparative TLC (n-hexane/EtOAc 1:1) to afford compounds 6 (35.5 mg) and 7 (23.5 mg). Fractions 180–230 (eluted with CHCl₃/MeOH 95:5) were subjected to silica gel column chromatography using the same solvent system. Fractions 212–224 were pooled and purified by preparative TLC (CHCl₃/MeOH 9.5:0.5), affording compound 8 (17.5 mg) and compound 9 (20.6 mg). The percentage yield of each compound was calculated relative to the methanol crude extract (25 g) that was subjected to silica gel column chromatography (Fig. 2).

DPPH assay

The antioxidant activity of the stem bark of Kirkia tenuifolia Engl. was evaluated in vitro using the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging assay, following a previously described protocol by Abera, B. et al.14. Ascorbic acid and sample-free DPPH solution were used as the positive and negative controls, respectively. The methanol extract and compounds was serially diluted in methanol in the concentration range from 1,000, 500, 250, 125, and 62.5 µg/mL from 1 mg/mL stock solution. To each prepared concentration, a fresh DPPH solution (2 mL, 0.04% w/v in CH3OH) was added. The sample solutions were incubated for 30 min and their absorbances were determined using the UV-Vis spectrophotometer in triplicate at 517 nm. The scavenging potentials were calculated using Eq. (1) and the results were reported as mean ± SD. Finally, the IC50 values were calculated from the relationship curves.

Where A sample and A control revealed absorbance of the sample and absorbance of the DPPH solution without sample respectively.

Antibacterial activity

Three Gram-positive bacterial strains S. aureus (ATCC 25923), L. monocytogenes (ATCC 15313) and S. agalactiae (ATCC 12386) along with three Gram-negative strains E. coli (ATCC 25922), S. typhimurium (ATCC 13311) and P. aeruginosa (ATCC 27853) were used to assess the antibacterial activity of the extract and isolated compounds. These bacterial strains were preserved in tryptic soy broth with 20% glycerol at -78 °C in the microbiology laboratory of the Traditional and Modern Medicine Research and Development Directorate (TMMRDD) at the Armauer Hansen Research Institute (AHRI). The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was determined using the 96-well microtiter plate broth dilution method following CLSI guidelines15. Stock solutions (5 mg/mL) of the extract and compounds were prepared in 5% DMSO. Serial two-fold dilutions in Mueller-Hinton Broth (MHB) resulted in final concentrations ranging from 0.01953125 mg/mL to 2.5 mg/mL. Bacterial inoculum, standardized to an OD of 0.08–0.1 at 625 nm (< 1.0 × 105 CFU/mL) and diluted to 5 × 105 CFU/mL, were added to each well and incubated at 37 °C for 18–24 h. After incubation, 40 µL of 0.4 mg/mL 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) was added and incubated for 30 min. The MIC values were determined as the lowest concentration at which no visible bacterial growth occurred, indicated by the absence of pink coloration following the addition of 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC). Controls included sterility, growth, ciprofloxacin as a positive control (0.01953125 µg/mL to 2.5 µg/mL), and 5% DMSO as a negative control.

Cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxic effect of the methanol extract from the stem bark of Kirkia tenuifolia Engl was tested on the MCF-7 breast cancer cell line. The cell line was obtained from the Centre of Molecular Medicine and Diagnostics, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Saveetha University, Chennai. Cells were cultured normally in DMEM/F12 media supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) and 1X Penicillin/Streptomycin solution. The cytotoxicity was assessed in vitro using the MTT test, with minor changes to the described method16. The plant extract stock solution (1 mg/mL) was prepared by dissolving the sample in 5% DMSO. Treatment media were prepared at final concentrations of 50 µg/mL, 100 µg/mL, and 200 µg/mL in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 1X Penicillin/Streptomycin solution. MCF-7 cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 10⁴ cells per well into 96-well plates in triplicate. Cells were incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO₂ atmosphere until reaching ~ 70% confluence before treatment with the prepared extract solutions. Following 24 h of treatment, the MTT assay was performed. The spent media were carefully removed, and a 0.5 µg/mL MTT reagent stock solution was added to each well containing fresh media. Formazan crystals were formed following 4 h incubation at 37 °C. The MTT reagent was discarded and DMSO was added to solubilize the crystals. The absorbance at 570 nm was determined by using an ELISA reader to quantify the cytotoxicity of the methanol extract.

Doxorubicin was used as the positive control, while 0.5% DMSO in cell culture medium was used as the negative control.

Antiviral activity

The cytotoxicity of the methanol extract of the stem bark of Kirkia tenuifolia Engl. was determined by the microtetrazolium (MTT) assay17. Briefly, series of three-fold serial dilutions in MEM were prepared ranging from 3.7 to 300 µg/mL, specifically: 3.7, 11.1, 33.3, 100, and 300 µg/mL. MDCK cells were incubated for 48 h at 36 °C in 5% CO2 in the presence of the dissolved specimens. The cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and a solution of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazolyl-2) 2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (ICN Biochemicals Inc. Aurora, Ohio) (0.5 µg/ml) in PBS was added to the wells. After 1 h incubation, the wells were washed and the formazan residue was dissolved in DMSO (0.1 ml per well). The optical density in the wells was then measured on a Thermo Multiskan FC plate reader at the wavelength of 540 nm and plotted against the concentration of extract. Each concentration was tested in three parallels. The 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC₅₀) of the extract was calculated from the dose–response data using GraphPad Prism version 4.0 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA), by plotting the percentage of cell inhibition against percentage of inhibition versus the concentrations.

Cytoprotection assay

The extracts were dissolved in 0.1 ml DMSO to prepare stock solutions, and final serial solutions (300–3.7 µg/ml) were prepared by adding MEM with 1 µg/ml trypsin. The extract was incubated with MDCK cells for 1 h at 36 °C. Each concentration of the extract was tested in triplicate. The cell culture was then infected with influenza virus A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (H1N1) (moi 0.01) for 48 h at 36 °C in the presence of 5% CO2. After this, cell viability was evaluated by MTT assay as described above. Based on the results of photometry, 50% inhibiting concentration (IC50), the concentration that provided protection of 50% cells comparing to the wells without extracts, was calculated for each extract as well as the selectivity index (SI, the ratio of CC50 to IC50). Rimantadine was used as a positive control antiviral agent to compare the activity of the plant extract. Serial dilutions of rimantadine were prepared in parallel with the test samples, and its effect was assessed under the same experimental conditions. For calculations, GraphPad Prism version 4.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) was used.

In silico pharmacokinetic and toxicity analysis: The pharmacokinetic properties of compounds (1–7) were assessed using the SwissADME tool (http://www.swissadme.ch/) to determine their drug-likeness using Lipinski’s rule of five. Toxicological profiles, including toxicological endpoints and LD50 values, were computed using the ProTox-II online platform (https://tox.charite.de).

Molecular docking

The present study aimed to complement the in vitro findings with in silico molecular docking analysis by predicting the binding orientation and affinity of the isolated compounds toward selected antioxidant and antibacterial target proteins. Based on the DPPH radical scavenging assay results, compounds 2, 6, and 7 showing promising antioxidant activity were docked against human peroxiredoxin 5 (PDB ID: 1HD2), human myeloperoxidase (PDB ID: 1DNU), aromatase (PDB ID: 3EQM), and topoisomerase II (PDB ID: 4FM9). Compounds 2 and 5–7, which showed notable antibacterial activity, were docked against the E. coli DNA gyrase B receptor (PDB ID: 4F86). In addition, compound 1 was docked with the S. agalactiae receptor (PDB ID: 2XTL), compound 7 with the S. aureus pyruvate kinase (PDB ID: 3T07), and compounds 1 and 2 with the S. typhi outer membrane protein (OmpF, PDB ID: 4KR4). Furthermore, compounds 2, 5, 6, and 7 were docked with the P. aeruginosa target protein (PDB ID: 2UV0), and compounds 2 and 7 were evaluated against the L. monocytogenes internalin A (InlA) protein (PDB ID: 1O6T). The protein targets were selected based on their key roles in the metabolic and pathogenic pathways related to antioxidant defense, cancer progression, and antimicrobial pathways.

Protein and ligand preparation

The 3D crystal structures of the selected target proteins were retrieved from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org) and saved in PDB format. These structures were imported into BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer 2021 for preprocessing, which involved the removal of water molecules, heteroatoms, and co-crystallized complexes. For site-specific molecular docking, the ligand-binding sites were identified by examining the coordinates (x, y, z) of the co-crystallized ligands within the SBD site spheres. The dimensions of the binding pockets for each target protein were determined and summarized in Table S1. Protein preparation was conducted using AutoDock 4.2.6 and MGLTools 1.5.6, following the protocol described by Mandal et al. 5. Polar hydrogens were added, gasteiger charges, AD4-type atoms and kollman charges were assigned. The resulting protein structures were saved in PDBQT format using AutoDockTools 1.5.6. The chemical structures of the studied compounds (1, 2, and 5–7) were drawn using ChemOffice (ChemDraw 16.0, PerkinElmer Inc., USA; https://www.Perkinelmer.com) with appropriate 2D orientation, and their geometries were energy-minimized using ChemBio3D. The energy-minimized ligand molecules were saved in pdbqt format using the AutoDock Vina tool to carry out the docking simulation.

Protein-ligand docking strategy

The objective of the docking protocol was to accurately reproduce the docking interactions and binding pores of the co-crystallized ligands within the experimentally resolved protein structures. To achieve this, the native ligand from each co-crystallized protein was first was separated and prepared. Subsequently, the ligands of interest were docked into the active sites of the respective proteins using AutoDock Vina 4.2.6. The docking simulations were executed via the Command Prompt interface, and the binding affinities along with root mean square deviation (RMSD) values were recorded. RMSD values ranging from 0 to 3 Å were considered acceptable, indicating reliable docking outcomes18. For each ligand, nine binding poses were generated, and the pose with the most favorable binding affinity and lowest RMSD was selected for further interaction analysis. The visualization of ligand orientations, binding interactions, and pocket conformations was performed using BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer 2021.

Result and discussion

Characterization of isolated compounds

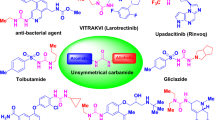

The methanol extract of the stem bark of K. tenuifolia afforded nine compounds (1–9) (Fig. 3), reported herein for the first time from the species Kirkia tenuifolia Engl and even from the genus Kirkia. The structures of the isolated compounds were determined based on rigorous spectroscopic investigation, including FT-IR, ¹H NMR, ¹³C NMR, and DEPT-135, and literature reported data comparison.

Compound 1 (24.5 mg) was isolated as a white solid, mp 19–23 °C. It showed the presence of a single spot on TLC having Rf 0.67 when n-hexane: EtOAc (8:2) was used as an eluent. The FT-IR spectrum (Fig. S1) of compound 1 showed characteristic bands of long-chain alkyl esters. The bands at 2921 and 2846 cm− 1 correspond to asymmetric and symmetric C-H stretching of sp³-hydrocarbons. A strong band at 1725 cm− 1 is attributed to ester C = O stretching, while a weak band at 1461 cm− 1 indicates CH₂ scissoring vibrations. The ¹H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl₃, Fig. S2, Table S2) exhibited the typical signals of an oxymethylene group at δH 4.05 (2 H, t, J = 6.7 Hz, H-19), and a methylene adjacent to the ester carbonyl at δH 2.29 (2 H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, H-2). A broad multiplet from δH 1.63–1.25 integrated for multiple protons, owing to the long aliphatic methylene chain linked with the carbonyl and ester function. A terminal methyl group appeared as a multiplet at δH 0.75–0.93 (6 H, H-18 & H-22).

The ¹³C NMR (Fig. S3), supported by DEPT-135 analysis (Fig. S4), displayed a resonance for the ester carbonyl carbon at δC 174.2 (C-1) and an oxymethylene carbon at δC 64.6 (C-19). The carbon adjacent to the carbonyl was at δC 34.6 (C-2), while the methylene carbons of the long aliphatic chain and the methylene of ester function were ranged from δC 22.9 to 32.1. Terminal methyl carbons gave resonance at δC 14.3. Based on these spectral characteristics and literature comparison, compound 1 was identified as butyl stearate, a fatty acid ester that has been reported to have antisickling activity19.

Compound 2 (22.1 mg, Rf: 0.43 in 20% EtOAc in n-hexane) was obtained as white sparkles with mp 212–214 °C. The FT-IR spectrum (Fig. S5) of compound 2 showed characteristic bands of the triterpenoid lupeol. A broad band at 3374 cm− 1 corresponds to O-H stretching of the hydroxyl group. Bands at 2924 and 2854 cm− 1 are due to C-H stretching of sp³-hybridized hydrocarbons. The band at 1650 cm− 1 is attributed to C = C stretching of the lupene alkene, while the C-O stretch of the secondary alcohol appears at 1056 cm− 1. The1 H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, Fig. S6, Table S3) spectra revealed doublets at δH 4.67 (1 H, d, J = 2.5, H-29a) and 4.55 (1 H, d, J = 1.2, H-29b) that reflect the presence of terminal isopropenyl group in lupane series of triterpenoids. A broad singlet and doublet of doublets observed at δH 3.63 (1 H, brs, OH) and 3.18 (1 H, dd, J = 11.2, 5.0, H-3) due to hydroxyl and oxymethine protons at C-3, respectively. The multiplet signals at δH 2.32 (1 H, m, H-19) were characteristic for a pentacyclic methine proton where the isopropenyl group is situated. Signals of seven singlets appearing at δH 1.67, 1.01, 0.95, 0.86, 0.82, 0.78, and 0.75 (21 H, s) are due to the methyl groups of the structure corresponding to H-30, H-26, H-27, H-23, H-25, H-28, and H-24, respectively. The rest of the protons were overlapped in the range of δH 1.65–1.15 (24 H, m). The13 C NMR (Fig. S7) spectrum exhibited thirty well-resolved signals corresponding to the lupane series of a triterpenoid skeleton. Signals corresponding to sp2 hybridized carbon were observed at δC 151.1 and 109.4 corresponding to C-20 and C-29, respectively, of which the former is an sp2 quaternary carbon, whereas, the latter is a terminal sp2 methine carbon from the DEPT-135 spectrum. The δC 79.1 (C-3) signal displayed an oxymethine carbon and sets of methine signals at δC 55.4 (C-5), 50.5 (C-9), 48.4 (C-18), 48.1 (C-19), and 38.1 (C-13). Seven methyl signals were also characteristically present at δC 28.1(C-23), 18.4 (C-30), 18.1 (C-28), 16.2 (C-25), 16.1 (C-26), 15.5 (C-24), and 14.2 (C-27) in good agreement with the triterpenoid skeleton. Besides, the DEPT-135 spectrum (Fig. S8) had an sp2 olefinic methylene signal at δ 109.4, an sp3 oxymethine signal at δC 79.1, five methine, ten methylene, and seven methyl signals characteristics. Spectroscopic data of compound 2 were close to the values reported for lupeol, which was isolated earlier from the roots of S. siamea, which showed antioxidant (IC₅₀ = 3.93 µg/mL) as well as antibacterial activity by inhibition zones of 14.17 ± 0.24 mm against E. coli and 14.33 ± 0.47 mm against S. pyogenes20.

Compound 3 was isolated as white substance (41.5 mg, Rf = 0.51 in 30% EtOAc in n-hexane). The ¹H NMR (400 MHZ, CD₃OD, Fig. S9, Table S4) spectrum indicated an AB olefinic spin system at δH 7.60 (1 H, d, J = 15.9 Hz, H-7) and δH 6.28 (1 H, d, J = 15.9 Hz, H-8), as well as an aromatic ABX spin system at δH 7.06 (1 H, dd, J = 8.1, 1.8 Hz, H-6), δH 7.02 (1 H, d, J = 1.8 Hz, H-2), and δH 6.90 (1 H, d, J = 8.1 Hz, H-5), indicating a 1,3,4-trisubstituted benzene ring. A methoxyl was observed at δH 3.92 (s, 3 H). The aliphatic region showed signals at δH 4.17 (2 H, t, J = 6.7 Hz, H-1′), a multiplet at δH 1.15–1.55 (24 H, H-2′ to H-13′), and a terminal methyl at δH 0.87 (3 H, t, J = 6.8 Hz, H-14′), characteristic of a C14 saturated hydrocarbon chain. The ¹³C NMR spectrum (Fig. S10) exhibited 25 carbon signals, corresponding to one CH₃, thirteen CH₂, five CH, and four quaternary carbons. Specifically, δC 167.5 (C-9), 144.7 (C-7), and 115.7 (C-8) signals indicated the presence of an α,β-unsaturated carboxylic group. The aromatic carbons appeared in the δC 127.1 (C-1), 109.3 (C-2), 147.9 (C-3 and C-4), 114.8 (C-5), and 123.1 (C-6) signal, which corresponds to a trisubstituted benzene ring. The methoxyl carbon appeared in the δC 56.0. Additional evidence at δC 64.6 (C-1′), 22.7–32.0 (C-2′ to C-13′), and 14.2 (C-14′) showed the presence of a saturated C14 aliphatic chain. This result was further supported by the DEPT-135 spectrum (Fig. S11), where characteristic CH and CH₂ signals for aromatic ring, aliphatic chain, and α,β-unsaturated carboxyl group were shown. The spectroscopic data of compound 3 closely match those of reported for Erythrinassinate C, previously isolated from L. lopadusanum aerial parts, which had previously exhibited bacteriostatic activity with a MIC of 250 µg/mL against E. faecalis21.

Compound 4 was isolated as a close analogue mixture of compound 3. Spectroscopic data were almost identical with the only perceivable difference observed in the ¹H NMR spectrum (Fig. S9, Table S5) an additional methylene signal at δH 3.64 (2 H, t, J = 6.6 Hz) for CH₂-14′, and an upfield methylene signal at δH 1.68 (m, H-13′) because of an oxygenated long-chain alkyl moiety. The ¹³C NMR (Fig. S10) revealed 25 carbon signals, thirteen CH₂, five CH, and four quaternary carbon atoms. The additional downfield methylene carbon signal at δC 63.0 (C-14′) and δC 32.8 (C-13′) relative to compound 3 also established the presence of the oxygenated long-chain group. These findings were also corroborated by the DEPT-135 spectrum (Fig. S11), which provided evidence for the presence of the characteristic CH and CH₂ signals of the aromatic moiety, the extended aliphatic chain, and the α,β-unsaturated carboxylic group. Overall, compound 4 spectroscopic characteristics closely resemble those found in the reported Lyciumol A, which was obtained previously from the root bark of L. chinense, the only difference exists in the number of the carbon atoms in the aliphatic chain22.

Compound 5 (18.7 mg, Rf = 0.38 in 40% EtOAc/n-hexane) was obtained as a white solid amorphous. The FT-IR spectrum (Fig. S12) of compound 5 showed characteristic bands of dimethylfraxetin. Bands at 2923 and 2854 cm− 1 correspond to C-H stretching of sp³-hybridized aliphatic carbons from methoxy groups. A band at 1741 cm− 1 is attributed to C = O stretching of the lactone carbonyl in the coumarin core. Additional bands at 1485 and 1259 cm− 1 indicate aromatic C = C and aryl C-O stretching, respectively. The ¹H NMR spectrum (400 MHz, CD₃OD, Fig. S13, Table S6) exhibited three aromatic proton signals at δH 6.80 (1 H, d, J = 9.1 Hz, H-3), 8.33 (1 H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, H-4), and 7.35 (1 H, s, H-5), along with three singlet methoxy proton signals at δH 3.80 (3 H, s, 8-OCH₃), 3.77 (3 H, s, 7-OCH₃), and 3.73 (3 H, s, 6-OCH₃). The ¹³C NMR spectrum (100 MHz, CD₃OD, and Fig. S14) revealed 13 different carbon resonances. Quaternary carbon signals occurred at δC 160.9 (C-2), 151.2 (C-6), 145.4 (C-7), 135.1 (C-8), 144.6 (C-9), and 123.5 (C-10), while the methine carbons occurred at δC 113.1 (C-3), 121.9 (C-4), and 107.3 (C-5). The methoxy carbons appeared at δC 56.3 (6-OCH₃), 59.0 (7-OCH₃), and 61.0 (8-OCH₃). These findings were also verified using the DEPT-135 spectrum (Fig. S15), which further showed that there were three aromatic CH groups and three methoxy groups present. The combined spectral data was found to be in good agreement with that already reported for dimethylfraxetin isolated from the aerial parts of Tagetes lucida23.

Compound 6 (35.5 mg, Rf = 0.53 in 50% EtOAc/n-hexane) was obtained as a yellow solid with a melting point of 315–321 °C. The ¹H NMR spectrum (400 MHz, CD₃OD, Fig. S16, Table S7) exhibited three aromatic proton signals at δH 8.31 (1 H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, H-1), δH 6.86 (1 H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, H-2), and δH 7.56 (1 H, s, H-7), along with five methoxy proton singlets at δH 3.30, 3.79, 3.83, 3.89, and 3.90 (15 H total). The ¹³C NMR spectrum (Fig. S17) showed 17 carbon resonances consisting of three aromatic methine (CH) carbons, ten quaternary carbons, and four methoxy carbon signals with one additional signal because of symmetry. Quaternary carbon signals appeared at δC 159.8 (C-6), 152.6 (C-3), 151.3 (C-4), 150.0 (C-4a), 148.8 (C-8), 144.7 (C-9), 134.7 (C-10), 122.8 (C-6a), 115.0 (C-10a), and 109.5 (C-4b). Methine carbons appeared at δC 121.3 (C-1), 107.8 (C-2), and 113.2 (C-7), while methoxy carbons appeared at δC 56.1 (4-OCH3), 60.4 ((3-OCH3), 60.6 (8-OCH3), and 60.9 (9-OCH3), and one signal due to symmetry methoxy (10-OCH3). These were also confirmed by the DEPT-135 spectrum (Fig. S18), which confirmed the presence of three aromatic CH carbons and five methoxy carbons, one of them due to symmetry. In general, compound 6 spectroscopic characteristics closely resemble those of Urolithin M5, previously isolated from the flowers of T. nilotica, the only structural difference is the methylation of five hydroxyl groups24.

Compound 7 (22.5 mg, Rf = 0.53 in 50% EtOAc/n-hexane) was isolated as yellow solid with m.p. 315–321 °C. The FT-IR spectrum (Fig. S19) of compound 7 displayed characteristic bands of a methoxylated Urolithin M5 derivative. A broad band at 3374 cm− 1 corresponds to the O-H stretch of the remaining hydroxyl group, while bands at 2923 cm− 1 are due to C-H stretching of methoxy groups. The C = O stretch of the lactone appeared at 1725 cm− 1, with aromatic C = C and aryl C-O stretching vibrations observed at 1602 and 1065 cm− 1, respectively. The ¹H NMR spectrum (400 MHz, CD₃OD, Fig. S20, Table S8) showed three aromatic proton signals at δH 8.29 (1 H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, H-1), δH 6.90 (1 H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, H-2) and δH 7.58 (1 H, s, H-7), and four methoxy proton signals. The ¹³C NMR spectrum (Fig. S21) contained 16 carbon signals with three aromatic methine (CH) carbons, ten quaternary carbons, and three methoxy groups, and in addition a one methoxy carbon by virtue of symmetry. Two strong quaternary carbon signals were seen at δC 160.5 (C-6), 153.6 (C-3), 152.8 (C-4), 150.4 (C-4a), 149.4 (C-8), 145.3 (C-9), 135.4 (C-10), 123.7 (C-6a), 115.2 (C-10a), and 108.8 (C-4b). Methine carbon resonances were seen at δC 121.7 (C-1), 108.2 (C-2), and 114.3 (C-7). The methoxy carbon resonances were seen at δC 56.6, 60.8, and 61.3, along with one other resonance for a symmetry-related methoxy. These were augmented by the DEPT-135 spectrum (Fig. S22), which revealed three aromatic methine (CH) carbon resonances at δC 121.6, 114.3, and 108.2. Methoxy carbon signals were at δC 56.6, 60.8, and 61.3, in addition to an additional signal on account of molecular symmetry. Otherwise, the spectroscopic information regarding compound 5 is quite akin to that of Urolithin M5, previously obtained from flowers of T. nilotica, the only notable structural difference is the methylation of four hydroxyl groups24.

Compound 8 (17.5 mg, Rf = 0.48 in 9.5% MeOH/CHCl₃) was a brown solid amorphous substance. The ¹H NMR spectrum (400 MHz, CD₃OD, Fig. S23, Table S9) exhibited signals in the range δH 3.55–5.07 ppm. The protons at δH 3.44 (1 H, t, J = 9.21 Hz, H-4), 3.54 (1 H, dd, J = 9.1, 3.6 Hz, H-2), 3.62 (1 H, t, J = 9.5 Hz, H-3), 3.91 (1 H, m, H-5), 4.00 (1 H, m, H-5′), 4.09 (1 H, t, J = 8.6 Hz, H-4′), 4.44 (1 H, d, J = 7.8 Hz, H-3′), and 5.07 (1 H, d, J = 3.7 Hz, H-1) are all attributed to oxy-methine protons. Additional resonances at δH 3.64 (2 H, d, J = 1.3 Hz, H-6), 3.58 (2 H, s, H-1′) and 3.76 (2 H, d, J = 2.3 Hz, H-6′) were attributed to oxy-methylene protons, while the singlet at δH 3.42 (3 H, s) was because of a methoxy proton. ¹³C NMR spectra (Fig. S24) showed 13 distinct carbon signals, including an anomeric carbon at δC 100.0. Eight sp³ oxy-methine carbons appeared at δC 81.1, 73.4, 72.4, 72.0, 71.0, 70.5, 69.9, and 68.0. Three oxy-methylene carbon resonances appeared at δC 64.6, 63.2, and 63.1, and a methoxy carbon at δC 56.5. The above spectroscopic data were very close to those observed for sucrose, the only structural difference is that one of the hydroxyl groups is methylated25,26.

Compound 9 (20.6 mg, Rf = 0.45 in 9.5% MeOH/CHCl3) was isolated as a brown solid amorphous substance. The ¹H NMR spectrum (400 MHz, CD₃OD, Fig. S25, Table S10) displayed signals between δH 3.55–5.07 ppm. The signals observed at δH 5.52 (1 H, d, J = 5.2 Hz, H-1), 4.10 (1 H, dd, J = 8.4, 4.8 Hz, H-2), 5.23 (1 H, dd, J = 12.4, 1.6 Hz, H-3), 5.06 (1 H, dd, J = 8.0, 6.4 Hz, H-4), 4.03 (1 H, d, J = 4.2 Hz, H-5), 4.26 (1 H, d, J = 5.2 Hz, H-3′), 3.80 (1 H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, H-4′), 3.65 (1 H, m, H-5′) all assignable to oxy-methine protons. Additional resonances at δH 3.52 (2 H, m, H-6), 3.59 (2 H, m, H-1′), and 3.85 (2 H, d, J = 2.0 Hz, H-6′) were attributed to oxy-methylene protons, while the signal at δH 2.41 (1 H, m, H-2′′), 1.20 (2 H, m, H-3′′), 0.80 (2 H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, H-4′′) and 0.90 (2 H, d, J = 4.4 Hz, H-5′′) corresponded to 2-methylbutyryl proton moiety. The ¹³C and DEPT-135 NMR spectra (Fig. S26 & 27) revealed 17 and 16 distinct carbon signals respectively, including an anomeric carbon at δC 100.0. Eight sp³ oxy-methine carbons were observed at δC 84.6 (C-1), 75.1 (C-2), 71.7 (C-3), 66.2 (C-4), 78.1 (C-5), 82.5 (C-3′), 77.9 (C-4′), and 83.4 (C-5′). Three oxy-methylene carbon signals appeared at δC 60.5 (C-6), 62.7 (C-1′) and 59.3 ((C-6′). The 2-methylbutyryl carbon signal appeared at δC 180.1 (C-1′′), 39.5 (C-2′′), 24.0 (C-3′′), 15.4 (C-4′′) and 16.0 (C-5′′). The overall spectroscopic data were consistent with those reported for sucrose esters, with the major difference being the presence of a substituent previously isolated from the glandular trichomes of L. typicum27.

Antioxidant activity

The antioxidant activity of the aerial parts of K. tenuifolia methanol extract and compounds (1–9) isolated therein was evaluated using the DPPH radical assay, with ascorbic acid as the standard reference (Table 1; Fig. 4). A Microsoft Excel 2016 spreadsheet was used to calculate the IC50 values. The logarithmic relationship curves that displayed the closest coefficient of determination (R2) values to one were chosen and the following equations were set. Methanol extract; Y = 6.7046ln(x) + 47.739, R2 = 0.9668, compound (1); Y = 6.2382ln(x) + 28.758, R2 = 0.9915, compound (2); Y = 8.6319 ln(x) + 33.143, R2 = 0.995, compound (3 & 4); Y = 8.6765 ln(x) + 29.201, R2 = 0.9818, compound (5); Y = 6.8268ln(x) + 34.996, R2 = 0.9756, compound (6); Y = 7.6145ln(x) + 38.855, R2 = 0.9851, compound (7); Y = 7.0851ln(x) + 43.268, R2 = 0.989, compound (8); Y = 5.8689ln(x) + 28.441, R2 = 0.9894, compound (9); Y = 8.1ln(x) + 10.641, R2 = 0.9778 and ascorbic acid (standard); Y = 6.0651ln(x) + 53.122, R2 = 0.9798 and the Y values were labeled as 50. The methanol crude extract exhibited notable antioxidant activity with an IC₅₀ of 1.40 µg/mL, which is 2.33 times less potent than ascorbic acid (IC₅₀: 0.60 µg/mL). This relatively low IC₅₀ for a crude extract suggests the presence of highly active antioxidant constituents. Such activity may result from synergistic effects among polyphenols, flavonoids, and other bioactive compounds present in the extract. Nonetheless, the result highlights the therapeutic promise of the extract and warrants further the need for further bioassay-guided fractionation to isolate and characterize the individual compounds responsible for the activity. This finding indicates that the MeOH extract of Kirkia tenuifolia Engl possesses comparable antioxidant potential compared to K. wilmsii, which has an EC₅₀ value of 3.57 ± 0.41 µg/mL 28. Lupeol (2) exhibited notable DPPH radical scavenging activity with an IC₅₀ of 7.05 µg/mL, aligning with previously reported activity (IC₅₀ = 3.93 µg/mL)20. Its presence in the plant supports known health benefits, including anticancer, antimicrobial, antidiabetic, cardioprotective, and hepatoprotective effects29. Compounds 6 and 7 also demonstrated strong antioxidant activity, with IC₅₀ values of 4.32 and 2.58 µg/mL, respectively. These compounds are derivatives of urolithin M-5 (pentahydroxy-urolithin), which is known for a range of pharmacological effects30. Their presence suggests potential for similar bioactivities, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and other therapeutic properties associated with urolithin M-5 30.

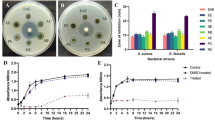

Antibacterial activity

The antibacterial activities of the crude methanol extract and isolated compounds 1–9 from Kirkia tenuifolia Engl were evaluated against six bacterial strains and compared with ciprofloxacin as the reference drug (Table 2). The crude MeOH extract is active against most strains at 0.156–1.25 mg/mL, particularly strong against L. monocytogenes. This finding indicates that the MeOH extract of K. tenuifolia possesses comparable antibacterial activities to K. wilmsii leave methanol extract which has an MIC values of 0.31 and 0.67 mg/mL against E. coli and S. aureus31. Another study reported that the endophytic fungi crude extracts from the leaves of Kirkia acuminata exhibited antibacterial activity, with an MIC value of 1.25 mg/mL against E.coli and P. aeruginosa32. Among the isolated compounds, Butyl stearate (1) exhibited antibacterial activity with an MIC value of 0.625 mg/mL against S. agalactiae and S. typhi. Lupeol (2) exhibited antibacterial activity with an MIC value of 625 µg/mL (0.625 mg/mL) against E. coli, S. typhi, and P. aeruginosa. Notably, this activity is more potent than previously reported MIC values of 2.5, 20, and 2.5 mg/mL against the respective pathogens in published literature33. Lupeol (2) and compound (7) exhibited MIC values of 2.5 and 0.938 mg/mL, respectively, against L. monocytogenes. Similarly, dimethylfraxetin (5), along with compounds 6 and 7, demonstrated antibacterial activity with an MIC value of 0.625 mg/mL against E. coli and P. aeruginosa. Additionally, compound 7 showed an MIC value of 0.625 mg/mL against S. aureus.

Antiproliferative activity

The methanol (MeOH) extract of Kirkia tenuifolia Engl exhibited a dose-dependent cytotoxic effect, significantly reducing the viability of MCF-7 breast cancer cells to 34.96 ± 0.20% at a concentration of 200 µg/mL surpassing the cytotoxicity of doxorubicin at the same dose (64.94 ± 0.44%) (Table 3; Fig. 5). The negative control (DMSO) maintained 100% cell viability, confirming that the observed effects were attributable to the extract.

Antiviral

The methanol (MeOH) crude extract of Kirkia tenuifolia Engl had a CC₅₀ of 39.8 µg/mL against MDCK cells and significant antiviral activity against influenza virus A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (H1N1) with an IC₅₀ of 4.2 µg/mL. The low IC₅₀ suggests significant inhibition of viral replication at low doses. The CC₅₀ to IC₅₀ ratio had a selectivity index (SI) of 9.5, indicating an optimal therapeutic window and the potential of developing the extract as an antiviral drug candidate34. Interestingly, the influenza strain used in this study had a mutation in genome segment 7 that confers resistance to rimantadine, a clinically used anti-influenza drug, which had an IC₅₀ value of 61 µM and a SI of 5. In contrast, the methanol extract of Kirkia tenuifolia Engl strongly inhibited this drug-resistant strain, indicating its potential as a lead for the development of new antiviral agents with the capacity to overcome existing drug resistance.

In Silico Pharmacokinetic predictions

Lipinski’s rule of five and Veber’s rule were applied to evaluate the drug-likeness of the isolated compounds. Compounds with MW < 500 Da, NHA < 10, NHD < 5, and LogP < 5 satisfy Lipinski’s criteria, indicating good drug potential. Additionally, Veber’s rule (TPSA ≤ 140 Ų, NRB ≤ 10) predicts good oral bioavailability35. Four of the isolated compounds fully complied with Lipinski’s Rule of Five, indicating favorable drug-likeness. Three compounds butyl stearate (1), lupeol (2), and Erythrinassinate C (3) each exhibited only one violation of the rule. Four compounds (2, 5, 6 and 7) met Veber’s rule, with NRB ≤ 5 and TPSA ≤ 140 Ų, indicating good potential for absorption in the gut. The LogP value provides insight into a compound’s lipophilicity, which influences membrane permeability and bioavailability36. Seven compounds exhibited LogP values below 5, suggesting optimal lipophilicity (Table 4). Lupeol (2) was predicted to be a non-inhibitor of cytochrome P450 enzymes, consistent with the behavior of the standard drug ascorbic acid. It also showed a similar profile to doxorubicin, being a non-inhibitor of CYP enzymes, except that it was identified as a P-glycoprotein (P-gp) substrate. The BOILED-Egg model revealed that compounds 3, 4, and 7 are predicted to be well absorbed through the gastrointestinal tract (white region), whereas compounds 5 and 6 are predicted to be blood brain barrier (BBB) permeable (yellow region), indicating promising pharmacokinetic profiles for drug development (Fig. 6). Specifically, compounds 5 and 6 are expected to cross the BBB, suggesting potential central nervous system (CNS) penetration. While BBB permeability may be advantageous for drugs targeting CNS disorders, it could pose risks of central side effects for non-CNS therapeutic agents. Therefore, the BBB-crossing ability of compounds 5 and 6 underscores the need for careful consideration during drug formulation and further evaluation to balance therapeutic efficacy with potential CNS-related toxicity37.

Toxicity prediction

Compounds 3 and 4 exhibited predicted LD₅₀ values greater than 5000 mg/kg (toxicity class 6), indicating they are non-toxic based on acute toxicity models. The remaining isolated compounds had LD₅₀ values ranging between 2000 and 5000 mg/kg, placing them in toxicity classes 4 and 5, and thus considered slightly toxic. Compounds (2–7) were predicted to be active in immunotoxicity assessments. Compounds (5–7) were predicted to exhibit mutagenic potential, while they were inactive for cytotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, and carcinogenicity similar to the profiles of ascorbic acid and ciprofloxacin (Table 5).

Molecular Docking studies

Binding mode analysis of compounds 2, 6, and 7 docked against human peroxiredoxin 5 (PDB ID: 1HD2) and human myeloperoxidase (PDB ID: 1DNU): Human Peroxiredoxin 5 (Prdx5) (PDB: 1HD2) is a thioredoxin-dependent peroxidase that reduces H₂O₂, alkyl hydroperoxides, and peroxynitrite, playing a key role in antioxidant defense and signaling. It protects cells from oxidative damage and serves as a target for antioxidant compounds38. Another key antioxidant receptor, Human Myeloperoxidase (MPO) catalyzes H₂O₂ oxidation of chloride into hypochlorous acid (HOCl), a potent antimicrobial oxidant. While essential for pathogen defense, excessive HOCl production leads to oxidative stress and tissue damage, contributing to vascular inflammatory diseases. MPO-derived chlorinated compounds act as inflammation biomarkers, making MPO inhibition a promising strategy for treating free radical-induced disorders39. Therefore, in this study, we predicted the binding orientation and affinity of the isolated compounds (2, 6, and 7) toward human Peroxiredoxin 5 (Prdx5; PDB ID: 1HD2) and Myeloperoxidase (MPO; PDB ID: 1DNU) receptors. The molecular docking results for the isolated compounds (2, 6, and 7) against selected target receptors demonstrated strong binding affinities (Table S10). Notably, lupeol (2) exhibited a lower binding energy (-6.1 kcal/mol) toward human Peroxiredoxin 5 (PDB ID: 1HD2) compared to ascorbic acid (-5.2 kcal/mol), indicating stronger binding. In contrast, compounds 6 and 7 showed comparable binding affinities, with values of -4.8 and − 5.1 kcal/mol, respectively. Lupeol (2) interacted with the target protein primarily through hydrophobic and Van der Waals interactions (Table S11, Fig. 7). For MPO (PDB ID: 1DNU), compounds 2, 6, and 7 exhibited lower binding energies of -8.6, -7.9, and − 8.1 kcal/mol, respectively, compared to ascorbic acid (-4.8 kcal/mol), suggesting stronger interactions. Among them, lupeol (2) showed the strongest binding affinity (-8.6 kcal/mol), forming one hydrogen bond with GLU-242 along with twelve van der Waals interactions (Table S11, Fig. 8). Compound (7) formed two hydrogen bonds with ARG-239 (3x) and PHE-332.

Binding mode of analysis of compounds docked against E. coli DNA gyrase B receptor (PDB ID: 4F86): E. coli DNA gyrase B (PDB: 4F86) is a vital bacterial enzyme involved in DNA replication. It functions by hydrolyzing ATP to introduce negative supercoils into DNA, which helps relieve torsional stress during replication and transcription. The ATP-binding site in the GyrB subunit is a key target for antibacterial agents. In molecular docking studies, this site is used to screen potential inhibitors that can block ATP hydrolysis, thereby preventing DNA supercoiling and leading to bacterial cell death. The protein (4F86) is widely used to identify and design new antibacterial compounds targeting the GyrB ATPase domain26. Therefore, in this study, we evaluated the binding orientation and affinity of the isolated compounds (2, 5–7) against the E. coli DNA gyrase B receptor (PDB ID: 4F86). The molecular docking results revealed strong binding affinities for all tested compounds (Table S12). Notably, compounds 2 and 5–7 exhibited lower binding energies (-5.5 to -6.6 kcal/mol) compared to the standard antibacterial drug ciprofloxacin (-5.1 kcal/mol). Lupeol (2) showed the strongest binding affinity (-6.6 kcal/mol), forming one hydrogen bond with GLU-50 and ten Van der Waals interactions involving residues ARG-76, ASP-49, ASN-46, ILE-78, ILE-94, VAL-120, GLY-119, SER-121, VAL-97 and VAL-93 (Table S12, Fig. 9). Compound (7) also demonstrated a strong binding affinity (-6.6 kcal/mol), forming hydrogen bonds with ASN-46 (twice), GLU-50, ASP-73 (twice), and THR-165 (Table S12, Fig. 9).

Binding mode of analysis of compounds docked against against S. aureus Pyruvate Kinase (PDB: 3T07), S. agalactiae protein (PDB: 2XTL) and S. typhi outer membrane protein (OmpF, PDB ID: 4KR4): S. agalactiae, a major cause of invasive infections in vulnerable populations, poses risks such as premature labor and stillbirth. Maternal rectovaginal colonization increases the risk of infant infection40. The ATP-binding cassette transporter is a promising target for innovative antimicrobial methods since it promotes antibiotic resistance, helps with nutrition acquisition, and prevents toxic accumulation all of which are critical defense mechanisms in S. agalactiae41. S. aureus causes a range of infections, from skin conditions to severe diseases like pneumonia and sepsis. The rise of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), resistant to many antibiotics, complicates treatment. Among the key enzymes in S. aureus, Pyruvate kinase (PK), critical for energy metabolism in S. aureus, catalyzes the final step of glycolysis, converting phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) and ADP into pyruvate and ATP, essential for bacterial survival, especially in anaerobic conditions. Inhibiting PK disrupts ATP production, hindering bacterial growth and survival, offering a potential therapeutic strategy against MRSA42. S. typhi is a Gram-negative, motile, rod-shaped pathogen transmitted through poor hygiene. Its outer membrane protein F (OmpF, PDB ID: 4KR4) acts as a porin, enabling passive diffusion of small molecules and aiding antibiotic uptake, making it a key target for antibacterial drugs43. In this study, we predicted the binding orientation and affinity of isolated compound 1 with the S. agalactiae receptor (PDB ID: 2XTL), compound 7 with S. aureus pyruvate kinase (PDB ID: 3T07), and compounds 1 and 2 with the S. typhi outer membrane protein (OmpF, PDB ID: 4KR4). Compound 1 exhibited a binding affinity of -4.3 kcal/mol with the 2XTL receptor, which is comparable to that of ciprofloxacin (-5.4 kcal/mol). The ligand–protein complex formed by compound 1 was stabilized by one hydrophobic interaction (Alkyl–LYS-251, three times) and thirteen Van der Waals interactions (Table S12). Docking analysis of compound 7 with S. aureus pyruvate kinase (3T07) revealed a higher binding affinity (-7.2 kcal/mol) compared to ciprofloxacin (-5.6 kcal/mol) (Table S12, Fig. 10). The resulting complex was stabilized by multiple hydrogen bonds involving THR-366 (3x), ASN-369, and ALA-358. Additionally, compounds 1 and 2 showed strong binding affinities with the S. typhi OmpF receptor (4KR4), at -4.7 and − 8.5 kcal/mol respectively, both of which were stronger than ciprofloxacin (-4.6 kcal/mol) (Table S12, Fig. 10). The complex formed by compound 1 was stabilized by two hydrogen bonds (SER-90 and SER-140), while that of compound 2 involved one hydrogen bond with GLU-44.

Binding mode of analysis of compounds docked against P. aeruginosa protein (PDB: 2UV0): P. aeruginosa, an opportunistic pathogen, is resistant to multiple antibiotics and poses challenges in treating hospital-acquired infections. Its high adaptability stems from efflux pumps, biofilm formation, and virulence factors44. The protein MurD ligase (PDB: 2UV0), involved in bacterial cell wall biosynthesis, catalyzes the addition of D-glutamic acid to UDP-N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine. Inhibiting MurD weakens the cell wall, making P. aeruginosa susceptible to stress45. Therefore, this study predicts the binding and affinity of isolated compounds against P. aeruginosa MurD. The molecular docking results for the isolated compounds (2, 5, 6, and 7) against P. aeruginosa protein (PDB ID: 2UV0) are summarized in Table S12. All compounds exhibited lower binding energies of -8.0, -7.8, -6.1, and − 7.8 kcal/mol, respectively, compared to the standard drug ciprofloxacin (-4.8 kcal/mol), indicating stronger binding interactions. Lupeol (2) exhibited the highest binding affinity (-8.0 kcal/mol), with the ligand-protein complex stabilized by a single hydrogen bond with GLY-123. Dimethylfraxetin (5) demonstrated strong binding affinity (-7.8 kcal/mol), forming two hydrogen bonds with ASP-73 (Table S12, Fig. 11). Similarly, compound (7) showed notable binding affinity (-6.5 kcal/mol), stabilized by six hydrogen bonds involving key residues LYS-42, ARG-122, ASP-43, GLY-123, GLY-120, and GLU-145.

Binding mode of analysis of compounds docked against L. monocytogenes InlA protein (PDB ID: 1O6T): L. monocytogenes is a Gram-positive foodborne pathogen that invades host epithelial cells through the interaction of its surface protein internalin A (InlA) with the host E-cadherin receptor. InlA (PDB ID: 1O6T) is a key virulence factor facilitating bacterial adhesion and internalization46. Targeting InlA with small molecules may inhibit this interaction, thereby blocking host cell invasion and representing a potential anti-virulence strategy in drug development. This study evaluated the binding affinity of isolated compounds against L. monocytogenes internalin A (InlA) protein (PDB ID: 1O6T). Molecular docking results for compounds 2 and 7 showed stronger interactions than the standard drug ciprofloxacin (-6.2 kcal/mol), with binding energies of -9.6 and − 7.4 kcal/mol, respectively (Table S12). Lupeol (2) exhibited the highest binding affinity, with its ligand-protein complex stabilized by one hydrogen bond with ASP-279, a hydrophobic Pi-alkyl interaction with PHE-150, and ten van der Waals interactions involving ASN-259, LYS-301, SER-257, THR-237, MG-1497, ILE-235, ASP-213, SER-192, GLU-170, and SER-172. Compound (7) also showed strong binding, forming four hydrogen bonds with GLN-109, GLN-153 (twice), and ASN-152 (twice), along with eight van der Waals interactions involving ASN-107, ASN-129, ASN-151, ASN-130, ASN-108, and GLN-131, indicating a strong and stable interaction (Table S12, Fig. 12).

Binding mode analysis of compounds docked against aromatase (PDB: 3EQM) and topoisomerase II (PDB: 4FM9): Oxidative stress has a dual role in cancer: it promotes tumor initiation and progression but also makes cancer cells more vulnerable due to high ROS levels. Natural antioxidants can disrupt this redox imbalance, inducing apoptosis, protecting DNA, reducing tumor-promoting inflammation, and enhancing the effectiveness of chemotherapy by protecting normal cells and selectively stressing cancer cells demonstrating anticancer effects beyond simple ROS scavenging47. Therefore, in this study, we predicted the binding orientation and affinity of antioxidant-active compounds 2, 6, and 7, compared to the FDA approved drugs letrozole and doxorubicin, against aromatase (PDB ID: 3EQM) and topoisomerase II (PDB ID: 4FM9), respectively. Aromatase is a key enzyme in estrogen biosynthesis, converting androgens to estrogens, which promote the proliferation of estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancer cells like MCF-7 48,49. Topoisomerase II (PDB: 4FM9) is a key enzyme that regulates DNA topology during replication and transcription. In rapidly dividing breast cancer cells, its activity is often elevated. Anticancer drugs like doxorubicin target this enzyme by stabilizing the DNA-topoisomerase complex and preventing the re-ligation of cleaved DNA strands. This leads to DNA double-strand breaks, triggering apoptosis and inhibiting tumor growth. Therefore, Topoisomerase II is an important therapeutic target in the treatment of aggressive breast cancers, including triple-negative and high-grade tumors50. Molecular docking results revealed that lupeol (2) exhibited stronger interactions with aromatase than the standard drug letrozole, with a binding energy of -8.4 kcal/mol compared to -8.1 kcal/mol (Table S13). Lupeol (2) formed a stable ligand-protein complex, primarily through one hydrophobic interaction with Pi-sigma TYR-424, and twelve van der Waals interactions involving residues GLN-428, PRO-429, PHE-427, PHE-430, TYR-361, MET-444, TYR-441, ILE-350, VAL-445, LEU-157, LYS-440, and PHE-132. Compound (7) also demonstrated a comparable binding affinity (-7.8 kcal/mol), forming four hydrogen bonds with ARG-115 (3×), GLY-439, and ILE-133. Additionally, it established six hydrophobic interactions Pi-sigma with ALA-306, alkyl interactions with ALA-443, MET-311, and ILE-132, and Pi-alkyl interactions with ILE-133 and ALA-438 along with one Pi-sulfur interaction with CYS-437. Eight van der Waals contacts further stabilized the complex, involving ARG-435, ARG-145, TRP-141, PHE-148, LEU-152, THR-310, MET-446, and ALA-307 (Table S13, Fig. S28). Towards topoisomerase II, molecular docking results revealed that lupeol (2) exhibited stronger interactions than the standard drug doxorubicin, with a binding energy of -9.7 kcal/mol compared to -9.4 kcal/mol (Table S13). Lupeol (2) formed a stable ligand-protein complex, primarily through one hydrogen bond with GLN-500 and eleven van der Waals interactions involving residues DA-11, DG-10, DC-9, DA-6, DT-7, DA-8, DC-8, MG-101, DG-7, DC-5, and DG-4. Compound (7) also demonstrated a favorable binding affinity (-7.7 kcal/mol), forming five hydrogen bonds with DC-9 (2×), DC-8, DA-8, DG-7 (2×), and DA-6. Additionally, it engaged in seven hydrophobic interactions Pi-sigma with DT-7, and Pi-alkyl interactions with DT-6, DG-7, DA-8, DC-9, DC-5, and DA-6 as well as one Pi-anion interaction with DT-7. The complex was further stabilized by five van der Waals contacts involving GLN-500, DA-6, MG-101, DG-9, and DG-10 (Table S13, Fig. S29).

Conclusion

Kirkia tenuifolia Engl. is a drought-resistant shrub native to eastern Africa, valued for its traditional medicinal use against cholera and thirst, as well as its ecological role in arid ecosystems. Its resilience, ornamental appeal, and ability to thrive in poor soils highlight its cultural, environmental, and potential pharmacological significance. The methanol extract of the aerial parts of Kirkia tenuifolia Engl yielded nine compounds (1–9), all reported for the first time from this species and even from the genus Kirkia. The MeOH extract and isolated compounds showed antibacterial activity against three Gram-positive bacteria (S. aureus, L. monocytogenes, S. agalactiae) and three Gram-negative strains (E. coli, S. typhimurium, P. aeruginosa). The extract showed potent activity against L. monocytogenes (MIC = 0.15625 mg/mL). Lupeol (2) showed notable antibacterial activity (MIC = 0.625 mg/mL) against E. coli, S. typhi, and P. aeruginosa, while dimethylfraxetin (5) and compounds 6 and 7 exhibited similar activity against E. coli and P. aeruginosa. Both the crude extract and compounds 1–9 displayed weak to strong antioxidant activity. The extract showed higher DPPH radical scavenging activity (IC₅₀ = 1.40 µg/mL) than the isolated compounds, though weaker than ascorbic acid (IC₅₀ = 0.60 µg/mL). Compounds 2, 5, 6, and 7 showed potent antioxidant activity (IC₅₀ = 2.58–9.00 µg/mL). The extract exhibited cytotoxicity against MCF-7 cells (34.96% viability at 200 µg/mL) and strong antiviral activity against H1N1 (IC₅₀ = 4.2 µg/mL, CC₅₀ = 39.8 µg/mL, SI = 9.5). Molecular docking revealed that compound 7 exhibited higher binding affinities with S. aureus pyruvate kinase (-7.2 kcal/mol) and L. monocytogenes receptor (-7.4 kcal/mol) compared to ciprofloxacin (-5.6 and − 6.2 kcal/mol, respectively). Lupeol (2) showed stronger binding to Prdx5 (-6.1 kcal/mol) than ascorbic acid (-5.2), while compounds 2, 5, 6, and 7 bound more strongly to human myeloperoxidase (-7.4 to -8.6) than ascorbic acid (-4.8). Lupeol (2) showed strong binding affinities of -8.4 and − 9.7 kcal/mol with aromatase and topoisomerase IIα receptors, respectively, outperforming the reference drugs letrozole (-8.1 kcal/mol) and doxorubicin (-9.4 kcal/mol). Most of the isolated compounds complied with Lipinski’s Rule of Five, indicating favorable drug-likeness and development potential. The antiviral and antiproliferative evaluations were conducted using only a single strain, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other strains or species. Addressing these limitations in future studies will be essential to fully validate and extend the current results. The demonstrated antioxidant, antibacterial, cytotoxic, and antiviral activities underscore the potential of Kirkia tenuifolia Engl as a source of bioactive compounds for drug development and warrant further in vivo and mechanistic studies to fully explore its therapeutic potential. However, further study is needed to validate the antiviral and antiproliferative effects across a broader range of pathogens and cell types.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and Supplementary Material.

References

Roy, M. et al. Profiling of aroma volatile compounds and antimicrobial potentiality of two Blumea species: A comparative insight of experimental and computational studies. Vegetos 2024, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42535-024-01040-w (2024).

Nigussie, G., Ashenef, S. & Meresa, A. The ethnomedicine, phytochemistry, and Pharmacological properties of the genus bersama: current review and future perspectives. Front. Pharmacol. 15, 1366427. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2024.1366427 (2024).

Mandal, M., Misra, D., Ghosh, N. N. & Mandal, V. Physicochemical and elemental studies of Hydrocotyle javanica Thunb. for standardization as herbal drug. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 7 11 979–986 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apjtb.2017.10.001 (2017).

Misra, D. et al. Anti-enteric efficacy and mode of action of tridecanoic acid Methyl ester isolated from monochoria hastata (L.) Solms leaf. Braz J. Microbiol. 53 (2), 715–726. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42770-022-00696-3 (2022).

Mandal, M. et al. Inhibitory efficacy of RNA virus drugs against SARS-CoV-2 proteins: an extensive study. J. Mol. Struct. 1234, 130152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2021 (2021).

Mandal, M., Misra, D., Ghosh, N. N., Mandal, S. & Mandal, V. GC-MS analysis of anti-enterobacterial dichloromethane fraction of Mandukaparni (Hydrocotyle Javanica Thunb.)–A plant from ayurveda. Pharmacogn J. 12 https://doi.org/10.5530/pj.2020.12.205 (2020).

Gardens, R. B. Kirkia tenuifolia Engl. https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org: names:813796-1 (accessed 10/20/2023).

Heywood, V. H., Brummitt, R. K. & Culham, A. Seberg, O. Flowering plant families of the world; Firefly books Ontario (2007).

Schmelzer, G. In Schmelzer GH, Gurib-Fakim A,(Eds.), Arroo R,(Associate Ed.) Lemmens RHMJ, Oyen LPA,(General Ed.). Plant Resources of Tropical Africa: Medicinal plants, 11, 1 (2008).

Gregarious, I. Learn more about Kirkia tenuifolia Care. https://greg.app/kirkia-tenuifolia-overview/ (accessed 20/10/2023).

Schmidt, E., Lotter, M. & McCleland, W. Trees and shrubs of Mpumalanga and Kruger national park; Jacana Media (2002).

Chigayo, K., Mojapelo, P., Bessong, P. & Gumbo, J. R. The preliminary assessment of anti-microbial activity of HPLC separated components of Kirkia wilmsii. Afr. J. Tradit Complement. Altern. Med. 11 (3), 275–228. https://doi.org/10.4314/ajtcam.v11i3.38 (2014).

Belitibo, D. et al. In vitro antibacterial Activity, molecular Docking, and ADMET analysis of phytochemicals from roots of Dovyalis abyssinica. Molecules 29 (23), 5608. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29235608 (2024).

Abera, B. et al. In vitro antibacterial and antioxidant activity of flavonoids from the roots of Tephrosia vogelii: a combined experimental and computational study. Z. Naturforsch C. 79 (9–10), 305–327. https://doi.org/10.1515/znc-2024-0044 (2024).

Alemu, M. et al. Antibacterial activity and phytochemical screening of traditional medicinal plants most preferred for treating infectious diseases in Habru District, North Wollo Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Plos One. 19 (3), e0300060. (2024).

Yarlılar, Ş. G., Yabalak, E., Yetkin, D., Gizir, A. M. & Mazmancı, B. Anticancer potential of Origanum munzurense extract against MCF-7 breast cancer cell. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 33 (6), 600–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/09603123.2022.2042495 (2023).

Mosmann, T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods. 65 (1–2), 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4 (1983).

Ramírez, D. & Caballero, J. Is it reliable to take the molecular Docking top scoring position as the best solution without considering available structural data? Molecules 23 (5), 1038. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23051038 (2018).

Tshilanda, D. D. et al. Antisickling activity of Butyl stearate isolated from ocimum Basilicum (Lamiaceae). Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 4 (5), 393–398. 10.12980/AP JTB.4.2014C1329 (2014).

Gebrehiwot, H., Ensermu, U., Dekebo, A., Endale, M. & Hunsen, M. Exploring the medicinal potential of Senna Siamea roots: an integrated study of antibacterial and antioxidant activities, phytochemical analysis, ADMET profiling, and molecular Docking insights. Appl. Biol. Chem. 67 (1), 48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13765-024-00899-2 (2024).

Gargiulo, E. et al. Antibacterial metabolites produced by Limonium lopadusanum, an endemic plant of Lampedusa Island. Biomolecules 14 (1), 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom14010134 (2024).

Pan, S. & Hou, A. J. New long-chain hydroxyalkyl ferulates from the root bark of Lycium Chinense mill. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 11 (7), 681–685. (2009).

Nayeli, M. B. et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of coumarins isolated from Tagetes Lucida Cav. Nat. Prod. Res. 34 (22), 3244–3248. https://doi.org/10.1080/14786419.2018.1553172 (2020).

Nawwar, M. & Souleman, A. 3, 4, 8, 9, 10-Pentahydroxy-dibenzo [b, d] pyran-6-one from tamarix Nilotica. Phytochemistry 23 (12), 2966–2967. (1984).

Hernández-García, E. et al. Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy data of isolated compounds from Acacia Farnesiana (L) willd fruits and two esterified derivatives. Data brief. 22, 255–268. (2019).

Abera, B. et al. In vitro antibacterial, antioxidant, in Silico molecular Docking and ADEMT analysis of chemical constituents from the roots of Acokanthera schimperi and Rhus glutinosa. Appl. Biol. Chem. 67 (1), 77. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13765-024-00930-6 (2024).

King, R. R., Calhoun, L. A., Singh, R. P. & Boucher, A. Characterization of 2, 3, 4, 3’-tetra-O-acylated sucrose esters associated with the glandular trichomes of Lycopersicon typicum. J. Agric. Food Chem. 41 (3), 469–473. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf00027a023 (1993).

Suleiman, M., Bagla, V., Naidoo, V. & Eloff, J. Evaluation of selected South African plant species for antioxidant, antiplatelet, and cytotoxic activity. Pharm. Biol. 48 (6), 643–650. https://doi.org/10.3109/13880200903229114 (2020).

Park, J. S. et al. A triterpenoid Lupeol as an antioxidant and anti-neuroinflammatory agent: impacts on oxidative stress in alzheimer’s disease. Nutrients 15 (13), 3059. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15133059 (2023).

Xian, W. et al. Distribution of urolithins metabotypes in healthy Chinese youth: difference in gut microbiota and predicted metabolic pathways. J. Agric. Food Chem. 69 (44), 13055–13065. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.1c04849 (2021).

Peter, M. Ethnobotanical study of some selected medicinal plants used by traditional healers in Limpopo Province (South Africa). Am. J. Res. Commun. 1 (8), 8–23 (2013).

Kubayi, S., Makola, R. T. & Dithebe, K. Exploring the Antimicrobial, antioxidant and extracellular enzymatic activities of culturable endophytic fungi isolated from the leaves of Kirkia acuminata Oliv. Microorganisms 13 (3), 692. (2025).

Musa, N. M., Sallau, M. S., Oyewale, A. O. & Ali, T. Antimicrobial activity of Lupeol and β-amyrin (triterpenoids) isolated from the rhizome of Dolichos pachyrhizus harm. Adv. J. chem. sect. A. 7 (1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.48309/ajca.2024.387131.1380 (2024).

Lica, J. J. et al. Effective drug concentration and selectivity depends on fraction of primitive cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (9), 4931. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22094931 (2021).

Issahaku, A. R. et al. Characterization of the binding of MRTX1133 as an avenue for the discovery of potential KRASG12D inhibitors for cancer therapy. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 17796. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-22668-1 (2022).

Şahin, S. 3, 4-difluoro-2-(((4-phenoxyphenyl) imino) methyl) phenol with in Silico predictions: Synthesis, spectral analyses, ADME studies, targets and biological activity, toxicity and adverse effects, site of metabolism, taste activity. J. Mol. Struct. 1317 (139136). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2024.139136 (2024).

Daina, A., Michielin, O. & Zoete, V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate Pharmaco kinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 42717. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep42717 (2017).

Salaria, D. et al. In vitro and in Silico antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potential Of essential oil Of Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapf. Of North-Western himalaya. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 40 (24), 14131–14145. https://doi.org/10.1080/07391102.2021.2001371 (2022).

Cai, B. et al. Purification and identification of novel myeloperoxidase inhibitory antioxidant peptides from tuna (Thunnas albacares) protein hydrolysates. Molecules 27 (9), 2681. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27092681 (2022).

Pena, J. M. S., Lannes-Costa, P. S. & Nagao, P. E. Vaccines for Streptococcus agalactiae: current status and future perspectives. Front. Immunol. 15, 1430901. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1430901 (2024).

Narciso, A. R., Dookie, R., Nannapaneni, P., Normark, S. & Henriques-Normark, B. Streptococcus pneumoniae epidemiology, pathogenesis and control. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 23, 256–271. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-024-01116-z (2024).

El Sayed et al. Novel pyruvate kinase (pk) inhibitors: new target to overcome bacterial resistance. ChemistrySelect 5 (11), 3445–3453. https://doi.org/10.1002/slct.202000043 (2020).

Arunkumar, M. et al. Evaluation of seaweed sulfated polysaccharides as natural antagonists targeting Salmonella Typhi ompf: molecular Docking and Pharmacokinetic profiling. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic. Appl. Sci. 11, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43088-021-00192-x (2022).

García-Villada, L., Degtyareva, N. P., Brooks, A. M., Goldberg, J. B. & Doetsch, P. W. A role for the stringent response in Ciprofloxacin resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 8598. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-59188-z (2024).

Azam, M. A. & Jupudi, S. MurD inhibitors as antibacterial agents: a review. Chem. Pap. 74 (6), 1697–1708. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11696-020-01057-w (2020).

Venugopal, S. Molecular Docking and molecular dynamic simulation studies to identify potential terpenes against internalin A protein of Listeria monocytogenes. Front. Bioinform. 4, 1463750. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbinf.2024.1463750 (2024).

An, X. et al. Oxidative cell death in cancer: mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Cell. Death Dis. 15 (8), 556. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-024-06939-5 (2024).

Kanamaeda, K. et al. Long-term Estrogen-deprived Estrogen receptor α-positive breast cancer cell migration assisted by fatty acid 2-hydroxylase. J. Biochem. 177 (1), 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1093/jb/mvae074 (2025).

Chan, H. J., Petrossian, K. & Chen, S. Structural and functional characterization of aromatase, Estrogen receptor, and their genes in endocrine-responsive and -resistant breast cancer cells. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 161, 73–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsbmb.2015.07.018 (2016).

Farouk, F. et al. Investigating the potential anticancer activities of antibiotics as topoisomerase II inhibitors and DNA intercalators: in vitro, molecular docking, molecular dynamics, and SAR studies. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 38 (1), 2171029. https://doi.org/10.1080/14756366.2023.2171029 (2023).

Acknowledgements

GN acknowledges Armauer Hansen Research Institute for sponsorship.

Funding

The work was funded by Armauer Hansen Research Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GN: Investigation, Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing original draft, Writing review and editing. AD, MA, AM, MC and ME: Conceptualization, Visualization, Supervision, Writing review and editing. MH, TN, VZ, SZ and AA: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing review and editing. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The study was reviewed and approved by the Armauer Hansen Research Institute (AHRI)/ALERT Ethics Review Committee under protocol number PO-37-21, and permission to collect Kirkia tenuifolia Engl was obtained from the Armauer Hansen Research Institute.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nigussie, G., Zaib, S., Dekebo, A. et al. Exploring the therapeutic potential of Kirkia tenuifolia Engl. stem bark extract and its bioactive compounds through experimental and computational approaches. Sci Rep 15, 38406 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22247-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22247-0