Abstract

To evaluate the relationship between pain catastrophizing, treatment modality, pain intensity, and functional disability in patients with chronic lower back pain, while also accounting for the effects of kinesiophobia and self-efficacy using generalized linear mixed models. Secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Outpatient clinical setting. Forty-eight adults with chronic low back pain participated in the study. Participants were randomized into three intervention groups receiving therapeutic exercise (ET) either alone, combined with manual therapy (ETmanualtherapy), or with kinesiotape (ETkinesiotape). Each group underwent two sessions per week for 12 weeks. Disability, pain intensity, kinesiophobia, pain catastrophizing, and self-efficacy were assessed at baseline, 3, 6, and 12 weeks. Generalized linear mixed models revealed a significant reduction in pain over time in all intervention groups (p < 0.001). A significant interaction was identified between the treatment group and catastrophizing levels (p = 0.023), with the Kinesiotape group being the only one showing increased pain scores associated with higher PCS levels. Regarding disability, significant effects were found for catastrophizing (p = 0.015), kinesiophobia (p < 0.001), and self-efficacy (p = 0.008), as well as a significant interaction between the group and self-efficacy (p = 0.003). In the groups without kinesiotaping, lower self-efficacy was associated with increased disability; however, this pattern was not observed in the kinesiotape group. The study found that pain and disability improved over time in all the intervention groups. However, psychological factors influenced outcomes differently depending on the treatment, with catastrophizing increasing pain only in the kinesiotape group. Thus, kinesiotaping may offer a protective effect by modulating psychological influences in chronic lower back pain.

Trial registration NCT05544890

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic low back pain (CLBP) is the second most common reason for medical visits, with research indicating that both its incidence and prevalence increase with age1,2. This condition places a substantial economic and social burden3,4, which is expected to grow in the coming years as the number of people affected by CLBP rises significantly5. Individuals with CLBP often experience considerable limitations in their daily activities, leading to high levels of pain and disability6. The high prevalence and certain clinical aspects that complicate diagnosis7, such as the lack of a specific patho-anatomical cause, make CLBP a particularly important area of study. In this context, comprehending the fundamental mechanisms of pain is crucial for enhancing diagnostic precision and customizing treatment strategies. While diagnosissing of CLBP is complex, it is increasingly relevant to evaluate the nociplastic, nociceptive, and neuropathic causes of pain based on its aetiopathogenesis8,9. Currently, the biopsychosocial model serves as a framework for both the study and management of CLBP because of the importance of physiological and psychosocial components10. This model recognizes that psychological factors can substantially affect pain perception and disability, thereby influencing treatment outcomes. For instance, the clinical profile of individuals diagnosed with CLBP is characterized by disability, fear of movement, catastrophizing, and lack of self-efficacy11.

Clinical treatment guidelines now prioritize exercise as the first-line approach for treating CLBP. Exercise therapy has been shown to enhance functionality, regulate biopsychosocial factors, and improve mental health, all based on the principles of biomechanics, pathology, and physiology12. Additionally, conservative interventions, such as spinal manipulative therapy, kinesiotaping, and various combinations of these methods, are emphasized, with a focus on multimodal approaches13. This multimodal treatment has demonstrated a rapid response in terms of clinical improvement, producing clinically significant reductions in pain intensity14. Secondary benefits include improvements in self-efficacy, decreased fear of movement, and reduced exercise catastrophizing15. Patients with CLBP who exhibit higher levels of kinesiophobia and pain are more likely to experience changes in their disability16. The positive effects of these interventions can, in part, be attributed to reductions in fear-avoidance behaviours17, pain perception18, and improvements in self-efficacy19. Thus, psychosocial variables function not only as outcomes but also as mediators in the efficacy of treatment.

Pain intensity and disability (primary outcomes) are common variables used in the treatment of CLBP in clinical practice20. Identifying high-risk factors enables healthcare providers to pinpoint individuals who may be more vulnerable to chronic pain. This allows for the creation of thorough treatment plans that address both the physical and psychological components of the condition. Interventions that address psychosocial elements in high-risk patients are generally more effective than standard care21. Therefore, tailored interventions designed to alter maladaptive beliefs and behaviours are essential. Disability and back pain intensity outcomes are considered potentially relevant treatment targets22, and exercise interventions targeting specific determinants of behaviour change are needed to support the adoption of this practice23. These strategies can assist clinicians in choosing targeted treatment strategies for subgroups of working patients with CLBP24. Psychological outcomes (i.e. kinesiophobia, self-efficacy, and concerns about pain) should be evaluated to observe the changes they produce in the subject25,26. Clarifying these mechanisms can inform the development of more targeted and effective treatment strategies, thereby improving clinical decision-making. This study aimed to evaluate the relationship between concerns about pain, kinesiophobia, self-efficacy, treatment type, pain perception—as measured by the Visual Analogue Scale—and functional disability, as assessed by the Oswestry Disability Index. Generalized linear mixed models were used to account for both fixed and random effects, providing a comprehensive analysis of how these psychological and treatment-related variables interact with patients with chronic lower back pain.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

This study is a secondary causal analysis of a three-arm randomized controlled trial that assessed therapeutic exercise with or without manual therapy or kinesiotape from 2022 to 2023. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Catholic University of Valencia (UCV/2019–2020/138) in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki27. Additionally, it was registered at Clinicaltrial.gov on 19/09/22 (NCT05544890). All participants provided written informed consent. The primary study that serves as the foundation for this secondary analysis has been published in a separate source28.

All patients were treated by two physiotherapists with more than 10 years of experience in the employed treatment modalities. A block randomization method with block sizes of four, six, or eight was used to ensure an equal distribution of participants across groups. This trial aimed to investigate the effects of core stability exercise alone or in combination with manual therapy (MT) or kinesiotape (KT) on disability, kinesiophobia, catastrophising, self-efficacy, and pain intensity (visual analogue scale [VAS]) in patients with CLBP and mild disability (Oswestry Disability Index [ODI] < 20%). A total of forty-eight patients with CLBP were included in this study. The sample size for the primary trial was estimated using GPower software (Franz Faul, Universität Kiel, Kiel, Germany; version 3.1.9.2).

The primary study’s findings indicated improvements in disability, pain perception, kinesiophobia, and concerns about pain following a 12-week intervention, with no significant differences between groups in most outcomes. Notably, a significant difference was identified in the ETmanualtherapy group, which exhibited a greater reduction in disability—as assessed by the Oswestry Disability Index—at 3 weeks compared to the ET group. Disability was measured using the Oswestry Disability Index (version 2.0), from zero to five, with higher scores indicating higher disability29. Pain perception was measured using the visual analogue scale30. The Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK) was used to measure fear of movement or reinjury using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”31. Kinesiophobia was measured using the Spanish version of the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia32. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) was used to assess the level of catastrophizing in the presence of pain (total score range: 0–52)33. To assess self-efficacy (SE), we employed the Spanish-validated version of the Chronic Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire34. This instrument consists of 19 items rated on a Likert-type scale ranging from 0 to 10, where 0 indicates “not at all confident,” 5 signifies “moderately confident,” and 10 denotes “completely confident.” The questionnaire has exhibited robust psychometric properties, including high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.87)35.

Interventions

The study involved dividing participants into groups of 15–17 people, who attended two sessions per week over a 12-week period. Each session lasted 60 min and was conducted under the supervision of a qualified physiotherapist. All participants completed the same 24 core stabilisation exercise sessions during the programme. All treatments were delivered individually, ensuring that each participant received personalized care without the influence of group dynamics or peer pressure.

Exercise group

Each training session commenced with stabilisation and control motor exercises, starting with a familiarisation period in which the participants practiced the chosen movements. The exercises were repeated thrice, with dynamic exercises comprising 10 repetitions and static exercises maintained for approximately 30 s of isometric contraction. Intervals of 30 s were allowed between sets, and 2–3 min between different exercises36. The physiotherapist led and monitored the personalised training, ensuring that all participants adhered to the same protocol based on the guidelines of Falla et al., with identical training volume across the board37.

Manual therapy group

The MT technique was administered by a physical therapist with eight years of experience prior to each exercise session. The technique comprised a single high-velocity manipulation in a side-lying position, applied bilaterally—once on each side—targeting the L3-S1 segment38. The patient’s thoracolumbar spine was rotated while the upper body was stabilised. Each session had a duration of five minutes, and the same procedure was adhered to in all 24 sessions over the 12-week treatment period39,40.

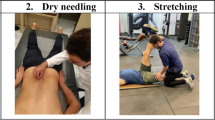

Kinesiotape group

Kinesiotape was applied to the lumbar region at the start of each session. The cutaneous surface was cleansed prior to application to enhance the adhesion. The tape was positioned with the subject in a neutral spine position, initiating with a Y-strip applied to the sacroiliac joint, a minimum of 5 cm inferior to the area of pain41. The tail of the tape was extended with minimal tension (15%-25%) or paper-off tension. A 22 cm strip was incised and elongated to 5 cm. The tape was removed after each session.

Data collection

All questionnaires and scales used to measure outcomes validated Spanish versions, yielding results equivalent to the original versions. Data were collected at baseline and 3, 6, and 12 weeks of the intervention.

Outcome measures

The primary outcomes for the causal mediation analysis were disability, evaluated using the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) questionnaire, which comprises 10 sections (each scored from zero to five, with higher scores indicating greater disability), and pain perception, assessed on a 10-point Visual Analogue Scale (VAS). All outcomes were measured one week prior to randomization and at 3, 6, and 12-weeks post-randomization.

Confounders

To minimize confounding variables in both dependent and independent variables, patients were categorized according to their disability level. Only patients classified as stage 2 on the Oswestry Disability Index were included in the study. There is a scarcity of information regarding the most effective treatments for particular CLBP subgroups42,43. To address this issue, the ODI scale was employed to categorize patients and minimize heterogeneity37. Only those with mild disability, classified as stage 2 on the ODI, were included, following previous research44. This approach facilitated the creation of a more uniform sample.

Data analysis

Descriptive analysis

Descriptive statistics were employed to characterize the sample. Continuous variables were summarized using means and standard deviations, as well as medians and interquartile ranges when appropriate. Categorical variables were described using proportions and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals.

Regression models

To assess the impact of psychosocial variables (PCS, SE, and TSK) on treatment outcomes, two generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) were constructed. These models assumed a gamma distribution with a log link function, given that the outcome variables were positively skewed and strictly positive. Treatment outcomes were evaluated using two dependent variables: the VAS and ODI. For each model, the fixed effects included the intervention group (exercise, exermanualtherapy, exerkinesiotape), time (0, 3, 6, and 12 months), and psychosocial variables. Sociodemographic covariates (age, sex, and BMI) were incorporated as fixed effects. Additionally, interaction terms between the group and psychosocial factors were included to explore the differential treatment effects. To account for within-subject correlations due to repeated measures, a random intercept for participant ID was included in all models (random effect structure). Model structure selection adhered to the protocol by Zuur & Ieno45, and models were implemented using the R packages lme4 (v1.1-35.3) and lmerTest (v3.1-3). Initial model specification was based on the “beyond optimal model” strategy, and final model selection was conducted via backward selection using the corrected Akaike Information Criterion, calculated with the MuMIn package (v1.46.0). The final model yielded AICc values of 548.52 and − 911,63 for the VAS and ODI outcomes, respectively, indicating the best trade-off between goodness-of-fit and model complexity among the evaluated candidate models. All model assumptions were meticulously verified: residuals were visually inspected for normality and homoscedasticity, normality was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and homoscedasticity was tested using Levene’s test. Multicollinearity and influential cases were assessed using tools from the performance package (v0.10.3). Inference on fixed effects was conducted using Type III ANOVA (via the car package, v3.1-0), and post-hoc contrasts were computed using estimated marginal means (EMMs) via the emmeans package (v1.7.5).

Results

Participants and sample characteristics

The study commenced with a sample of 48 participants, comprising 17, 16, and 15 in the ET, ET manualtherapy, and ETkinesiotape groups, respectively. The subsequent table (Table 1) presents the descriptive analyses stratified by the study group. Each assessment was delineated by specific outcomes for each measurement time point.

Residual adjustments and necessary assumptions for VAS and ODI

The model demonstrated a good fit, fulfilling the main assumptions of linearity on the link scale, normality of the random effects, homoscedasticity of the residuals, absence of multicollinearity, and absence of influential outliers. These assumptions were met for both the VAS and ODI models.

Regression model pain perception

The GLMMs employing a gamma distribution with a logarithmic link function identified two significant fixed effects on the VAS pain scores: time and the interaction between group and catastrophizing (Group: PCS). First, a significant reduction in perceived pain was observed over time, with an estimate of − 0.062 ± 0.015 (t = − 4.066; p < 0.001), indicating a progressive decrease in VAS scores as the months of intervention progressed. This overall improvement was consistent across all treatment groups, confirming the beneficial effect of time on pain evolution (Fig. 1).

Second, the effect of PCS on perceived pain varied according to the treatment group (χ2 = 7.514; p = 0.023). Specifically, in the group that received kinesiotape prior to exercise, VAS scores progressively increased with higher levels of catastrophizing: participants with PCS scores of 6, 11, and 16 had estimated marginal means (EMM) of 2.81 ± 0.5 [95% CI: 1.97–3.99], 3.09 ± 0.5 [2.24–4.25], and 3.4 ± 0.53 [2.50–4.62], respectively. The contrasts between the PCS levels were marginally significant (for example, PCS6 vs. PCS16: difference = 0.83; z = − 2.23; p = 0.066). In contrast, in the exercise-only and exercise-plus-manual therapy groups, VAS scores remained stable across different levels of catastrophizing, with no statistically significant differences (e.g. exercise PCS6 vs. PCS16: difference = 1.1; p > 0.05). The estimated marginal means for the exercise group at PCS scores of 6, 11, and 16 were 3.19 ± 0.49 [2.36–4.3], 3.04 ± 0.44 [2.29–4.02], and 2.89 ± 0.51 [2.05–4.09], respectively, and for the exercise-plus-manual therapy group, 3.77 ± 0.62 [2.73–5.2], 3.42 ± 0.51 [2.55–4.58], and 3.1 ± 0.5 [2.25–4.26] (Fig. 2).

Regression model functionality

The analysis of GLMMs employing a gamma distribution with a logarithmic link function revealed that disability was significantly influenced by several psychological variables and temporal factors. First, catastrophizing had a significant effect on disability (χ2 = 5.869; p = 0.015), indicating that elevated levels of catastrophizing thoughts were associated with increased disability scores. Similarly, kinesiophobia demonstrated a positive and significant association (χ2 = 13.783; p < 0.001). Time also exerted a significant effect on patient improvement (χ2 = 38.893; p < 0.001), reflecting a progressive reduction in disability as the sessions advanced (estimate = − 0.005 ± 0.001; t = − 6.236; p < 0.001) (Fig. 3).

Furthermore, significant effects of the treatment group (χ2 = 8.108; p = 0.017) and self-efficacy (χ2= 7.049; p = 0.008) were observed, along with a significant interaction between the group and self-efficacy (χ2 = 11.653; p = 0.003). Participants in the exercise-only and exercise-plus-manual therapy groups exhibited a progressive increase in disability scores as their self-efficacy decreased. For instance, in the exercise-plus-manual therapy group, the contrast between follow-up times AF6 and AF20 showed a difference of − 0.97 (z = − 4.21; p < 0.001), indicating a negative progression in those with lower confidence in their abilities. The EMM for self-efficacy in this group ranged from 1.05 ± 0.01 [95% CI: 1.03–1.07] at AF6 to 1.08 ± 0.01 [1.06–1.11] at AF20. Conversely, participants in the kinesiotape plus exercise group maintained stable disability levels irrespective of their self-efficacy, with no statistically significant changes across the evaluation points (e.g. AF6 vs. AF20: difference = 1.01; p > 0.05) (Fig. 4).

Discussion

In examining pain perception, the findings indicated a progressive amelioration of pain over time, irrespective of the intervention group or other variables included in the model. The interaction between the intervention group and participants’ PCS level revealed that the association between catastrophizing and perceived pain differed across the experimental groups. Notably, in the cohort receiving kinesiotaping prior to exercise, there was a trend of increasing VAS scores correlating with heightened catastrophizing, with marginally significant differences observed between the lowest and highest PCS levels. Although individual contrasts did not achieve statistical significance, the overall interaction was significant, suggesting a distinct pattern in this group: individuals with elevated catastrophizing reported greater pain over time than the exercise-only and exercise + manual therapy groups, where this relationship was absent.

Regarding perceived disability, the results demonstrated a significant reduction in disability scores over time, indicating progressive improvement regardless of the intervention group. Furthermore, significant effects of both PCS and TSK were observed, such that higher levels of these psychological variables were associated with higher disability scores. A significant interaction between the treatment group and self-efficacy was also identified, indicating that the relationship between self-efficacy and disability varied by group. Specifically, participants in the exercise-only and exercise + manual therapy groups exhibited increased disability as self-efficacy decreased, whereas in the kinesiotaping group, this relationship was not evident, with disability levels remaining stable irrespective of self-efficacy. These findings suggest that self-efficacy may exert a different protective role contingent upon the type of intervention received. In particular, kinesiotaping may buffer the detrimental effects of low self-efficacy on functional outcomes, potentially modulating psychological distress more effectively than exercise or manual therapy alone.

Catastrophizing levels are considered a significant factor in the design of treatment protocols for patients diagnosed with CLBP because of their direct influence on pain perception. In this context, initial levels of catastrophizing are hypothesized to moderate the treatment response, suggesting that patients with higher baseline values would derive greater benefits from the applied techniques46. Moreover, CLBP is recognized for its multidimensional nature, encompassing complex interactions among physical, psychological, and social aspects, as well as overall health status47. This observation, derived from the present study, has been corroborated by numerous other investigations that have demonstrated a direct relationship between pain intensity and catastrophizing48. These findings suggest potential internal influences among factors within the psychosocial domain that are closely associated with pain perception49.

Several authors have demonstrated the mediating role of concerns about pain in exercise on pain intensity50 and disability, compared to other treatment techniques51,52. Furthermore, a meta-analysis indicated that spinal manipulative techniques appear to exhibit comparable mediating processes through common psychological factors such as concerns about pain, kinesiophobia, and self-efficacy, providing comparable effects to other treatments for short-term pain relief, including exercise53,54. Notably, fear avoidance and self-efficacy beliefs acted as mediators for the impact of disability when exercise was prescribed, in contrast to manual therapy55. Moreover, high levels of kinesiophobia can lead to increased pain sensitivity due to psychosocial factors56. Regarding kinesiophobia, the established fear-avoidance model suggests a close relationship between avoidance behaviours and pain, particularly when the pain is persistent57. When the fear-avoidance model is affected, fear of pain arises, leading to reduced activity levels. This pattern affects patients diagnosed with CLBP, altering their pain response by increasing avoidance, anxiety, and muscle dysfunction58.

Continuing with this interaction, pain is the variable that most significantly modifies fear of movement, as it engenders a sense of vulnerability to pain and the potential for injury, thereby amplifying both factors59. A cycle emerges, triggering adaptations that connect negative thought patterns, leading to movement limitation directly associated with increased pain perception, which subsequently causes muscle atrophy, ultimately resulting in spinal functional disability60. Furthermore, due to the lack of clarity regarding which factor initiates this cascade of modifications, altered movement patterns in patients with kinesiophobia may generate changes in afferent input, which subsequently disrupts the individual’s proprioception61. This is particularly relevant in the context of our findings on self-efficacy: while lower self-efficacy was associated with increased disability in the exercise and manual therapy groups, the kinesiotaping group did not show this vulnerability. This suggests that kinesiotaping may help stabilize functional outcomes even in patients with lower psychological resources, offering a more resilient approach for managing disability in CLBP. While pain catastrophizing, fear of pain, and self-efficacy are frequently conceptualized as relatively stable psychological traits, our findings indicate that these constructs may be subject to change over time in response to intervention. The observed reductions in PCS and TSK scores, coupled with improvements in SE, support the notion that even stable psychological factors can be influenced by treatment. This aligns with previous studies demonstrating that cognitive-behavioral and multidisciplinary approaches can modify these traits in patients with chronic pain62.

This study had several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, although our sample was classified as stage 2 according to the ODI, alternative classification systems, such as pain phenotyping based on nociceptive, neuropathic, or nociplastic mechanisms, might have offered a more precise framework for understanding patient subgroups and guiding targeted interventions. Future research could benefit from incorporating such approaches to better capture the multidimensional nature of CLBP and its treatment response. Second, although psychosocial variables were included in the analysis, the study did not assess psychological or social factors separately, which limited a more granular understanding of their individual contributions. Future studies could benefit from distinguishing between these domains to refine interpretation and treatment adaptation. Additionally, although the results highlighted positive changes during the intervention period, the long-term sustainability of these improvements in pain, functionality, and psychological variables remained uncertain; extended follow-up studies are necessary to assess the durability of the treatment effects.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study revealed that pain perception and disability exhibited progressive improvement over time in all intervention groups. Nevertheless, the association between psychological factors and clinical outcomes varied according to treatment modality. Notably, higher levels of catastrophizing were linked to increased pain exclusively in the kinesiotape plus exercise group, whereas lower self-efficacy was predictive of greater disability in the exercise-only and exercise plus manual therapy groups but not in the kinesiotape group. These findings suggest that kinesiotaping may uniquely modulate the impact of certain psychological factors, potentially providing a protective effect against pain in patients with chronic lower back pain.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- CLBP:

-

Chronic low back pain

- Df:

-

Degrees of freedom

- ES:

-

Effect size

- ET:

-

Exercise therapy

- ETkinesiotape:

-

Exercise therapy combined with kinesiotaping

- ETmanualtherapy:

-

Exercise therapy combined with manual therapy

- KT:

-

Kinesiotape

- MT:

-

Manual therapy

- ODI:

-

Oswestry disability index

- PCS:

-

Pain catastrophizing scale

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- SE:

-

Standard error

- TSK:

-

Tampa scale of kinesiophobia

- VAS:

-

Visual analogue scale

References

Cypress, B. K. Characteristics of physician visits for back symptoms: A National perspective. Am. J. Public. Health. 73 (4), 389–395 (1983).

Deyo, R. A., Mirza, S. K., Turner, J. A. & Martin, B. I. Overtreating chronic back pain: Time to back off? J. Am. Board. Fam Med. 22 (1), 62–68 (2009).

Thomas, E., Peat, G., Harris, L., Wilkie, R. & Croft, P. R. The prevalence of pain and pain interference in a general population of older adults: Cross-sectional findings from the North Staffordshire osteoarthritis project (NorStOP). Pain 110 (1–2), 361–368 (2004).

Dionne, C. E., Dunn, K. M. & Croft, P. R. Does back pain prevalence really decrease with increasing age? A systematic review. Age Ageing. 35 (3), 229–234 (2006).

Li, Y. et al. Exercise intervention for patients with chronic low back pain: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Front. Public. Health. 11, 1155225 (2023).

Pitcher, M. H., Von Korff, M., Bushnell, M. C. & Porter, L. Prevalence and profile of high-impact chronic pain in the united States. J. Pain. 20 (2), 146–160 (2019).

Finucane, L. M. et al. International framework for red flags for potential serious spinal pathologies. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 50 (7), 350–372 (2020).

Nijs, J. et al. Low back pain: guidelines for the clinical classification of predominant Neuropathic, Nociceptive, or central sensitization pain. Pain Physician. 14 (3), E185–E200 (2011).

Allegri, M. et al. Mechanisms of low back pain: a guide for diagnosis and therapy. F1000Research ;5: (2016). F1000 Faculty Rev-1530.

Bolton, D. A revitalized biopsychosocial model: Core theory, research paradigms, and clinical implications. Psychol. Med. 53 (16), 7504–7511 (2023).

Melloh, M. et al. Differences across health care systems in outcome and cost-utility of surgical and Conservative treatment of chronic low back pain: a study protocol. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 9, 81 (2008).

O’Connell, N. E., Cook, C. E., Wand, B. M. & Ward, S. P. Clinical guidelines for low back pain: A critical review of consensus and inconsistencies across three major guidelines. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 30 (6), 968–980 (2016).

Bussières, A. E. et al. Spinal manipulative therapy and other Conservative treatments for low back pain: A guideline from the Canadian chiropractic guideline initiative. J. Manipulative Physiol. Ther. 41 (4), 265–293 (2018).

Peterson, K., Anderson, J., Bourne, D., Mackey, K. & Helfand, M. Effectiveness of models used to deliver multimodal care for chronic musculoskeletal pain: A rapid evidence review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 33 (Suppl 1), 71–81 (2018).

Aspinall, S. L., Leboeuf-Yde, C., Etherington, S. J. & Walker, B. F. Changes in pressure pain threshold and Temporal summation in rapid responders and non-rapid responders after lumbar spinal manipulation and sham: A secondary analysis in adults with low back pain. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 47, 102137 (2020).

Wood, L. et al. Pain catastrophising and kinesiophobia mediate pain and physical function improvements with pilates exercise in chronic low back pain: A mediation analysis of a randomised controlled trial. J. Physiother. 69 (3), 168–174 (2023).

Foster, N. E., Jensen, C., Hill, J. C., Lewis, M. & Main, C. J. Explaining How cognitive behavioral approaches work for low back pain: Mediation analysis of the back skills training trial. Spine. ;42(17):E1015-22. (2017). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28832441/

Mansell, G., Hill, J. C., Main, C., Vowles, K. E. & van der Windt, D. Exploring what factors mediate treatment effect: Example of the start back study High-Risk intervention. J. Pain. 17 (11), 1237–1245 (2016).

O’Neill, A., O’Sullivan, K., O’Sullivan, P., Purtill, H. & O’Keeffe, M. Examining what factors mediate treatment effect in chronic low back pain: A mediation analysis of a cognitive functional therapy clinical trial. Eur. J. Pain. 24 (9), 1765–1774 (2020).

Tagliaferri, S. D. et al. Domains of chronic low back pain and assessing treatment effectiveness: A clinical perspective. Pain Pract. 20 (2), 211–225 (2020).

Rabiei, P. et al. Are tailored interventions to modifiable psychosocial risk factors effective in reducing pain intensity and disability in low back pain? A systematic review with meta-analysis of randomized trials. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 55 (2), 89–108 (2025).

Fors, M. et al. Are illness perceptions and patient self-care enablement mediators of treatment effect in best practice physiotherapy low back pain care? Secondary mediation analyses in the betterback trial. Physiother Theory Pract. 40 (8), 1753–1766 (2024).

Duarte, S. T. et al. Exploring barriers and facilitators to the adoption of regular exercise practice in patients at risk of a recurrence of low back pain (MyBack project): a qualitative study. Disabil. Rehabil ;1–10. (2024).

Trinderup, J. S., Fisker, A., Juhl, C. B. & Petersen, T. Fear avoidance beliefs as a predictor for long-term sick leave, disability and pain in patients with chronic low back pain. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 19 (1), 431 (2018).

Wun, A. et al. Why is exercise prescribed for people with chronic low back pain? A review of the mechanisms of benefit proposed by clinical trialists. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 51, 102307 (2021).

Wood, L. et al. Treatment targets of exercise for persistent non-specific low back pain: A consensus study. Physiotherapy 112, 78–86 (2021).

World Medical Association. World Medical association declaration of helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human participants. JAMA. Oct 19. (2024). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2024.21972

Blanco-Giménez, P. et al. Clinical relevance of combined treatment with exercise in patients with chronic low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 17042 (2024).

Jimenez-Pacheco, A. & Jimenez-Pacheco, A. Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. A therapeutic challenge. Rev. Med. Chil. 142 (8), 1078–1079 (2014).

Fähndrich, E. & Linden, M. Reliability and validity of the visual analogue scale (VAS)(author’s transl). Pharmacopsychiatria 15 (3), 90–94 (1982).

Swinkels-Meewisse, E. J., Swinkels, R. A., Verbeek, A. L., Vlaeyen, J. W. & Oostendorp, R. A. Psychometric properties of the Tampa scale for kinesiophobia and the fear-avoidance beliefs questionnaire in acute low back pain. Man. Ther. 8 (1), 29–36 (2003).

Ferrer-Peña, R. et al. Adaptation and validation of the Spanish version of the graded chronic pain scale. Reumatol Clin. 12 (3), 130–138 (2016 May-Jun).

Campayo, J. G. et al. Validación de La versión española de La Escala de La catastrofización ante El Dolor (Pain catastrophizing Scale) En La fibromialgia. Med. Clin. (Barc). 131 (13), 487–492 (2008).

Martín-Aragón, M., Pastor, M., Rodríguez-Marín, J., March, M. & Lledó, A. Percepción de autoeficacia En Dolor crónico. Adaptación y validación de La chronic pain Self-Efficacy scale. Rev. Psicol. Salud. 11 (1), 51–76 (1999).

Van-der Hofstadt Román, C. J., Leal Costa, C., Alonso Gascón, M. R. & Rodríguez Marín, J. Calidad de vida, emociones negativas, autoeficacia y Calidad Del sueño En Pacientes Con Dolor crónico: efectos de Un programa de intervención psicológica. Univ. Psychol. 16 (3), 1–10 (2017).

Ozsoy, G. et al. The effects of myofascial release technique combined with core stabilization exercise in elderly with non-specific low back pain: A randomized controlled, single-blind study. Clin. Interv Aging. 14, 1729–1737 (2019).

Wang, F., Jiang, Y. & Hou, L. Effects of different exercise intensities on motor skill learning capability and process. Sci. Sports. 38 (2), 207–e1 (2023).

McCarthy, C. J., Potter, L. & Oldham, J. A. Comparing targeted thrust manipulation with general thrust manipulation in patients with low back pain. A general approach is as effective as a specific one. A randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. Sport Exerc. Med. 5 (1), e000514 (2019).

Aspinall, S. L., Jacques, A., Leboeuf-Yde, C., Etherington, S. J. & Walker, B. F. No difference in pressure pain threshold and Temporal summation after lumbar spinal manipulation compared to sham: A randomised controlled trial in adults with low back pain. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 43, 18–25 (2019).

Bergmann, T. F. & Peterson, D. H. Chiropractic Technique 5th edn (Elsevier Health Sciences, 2010).

Uzunkulaoğlu, A., Aytekin, M. G., Ay, S. & Ergin, S. The effectiveness of Kinesio taping on pain and clinical features in chronic non-specific low back pain: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Turk. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 64 (2), 126–133 (2018).

Mauck, M. C. et al. Evidence-based interventions to treat chronic low back pain: treatment selection for a personalized medicine approach. Pain Rep. 7 (5), e1019 (2022).

Kreiner, D. S. et al. Guideline summary review: an evidence-based clinical guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of low back pain. Spine J. 20 (7), 998–1024 (2020).

Henry, S. M., Van Dillen, L. R., Trombley, A. R., Dee, J. M. & Bunn, J. Y. Reliability of novice raters in using the movement system impairment approach to classify people with low back pain. Man. Ther. 18 (1), 35–40 (2013).

Zuur, A. F. & Ieno, E. N. A protocol for conducting and presenting results of regression-type analyses. Methods Ecol. Evol. 7 (6), 636–645 (2016).

Day, M. A. et al. Moderators of mindfulness Meditation, cognitive therapy, and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for chronic low back pain: A test of the Limit, Activate, and enhance model. J. Pain. 21 (1), 161–169 (2020).

O’Sullivan, P., Caneiro, J. P., O’Keeffe, M. & O’Sullivan, K. Unraveling the complexity of low back pain. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 46 (11), 932–937 (2016).

Gustafsson, M. & Gaston-Johansson, F. Pain intensity and health locus of control: a comparison of patients with fibromyalgia syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis. Patient Educ. Couns. 29 (2), 179–188 (1996).

Cheng, S. K. & Leung, F. Catastrophizing, locus of control, pain, and disability in Chinese chronic low back pain patients. Psychol. Health. 15 (5), 721–730 (2000).

Sisco-Taylor, B. L. et al. Changes in pain catastrophizing and Fear-Avoidance beliefs as mediators of early physical therapy on disability and pain in acute Low-Back pain: A secondary analysis of a clinical trial. Pain Med. 23 (6), 1127–1137 (2022).

Hall, A. M., Kamper, S. J., Emsley, R. & Maher, C. G. Does pain-catastrophising mediate the effect of Tai Chi on treatment outcomes for people with low back pain? Complement. Ther. Med. 25, 61–66 (2016).

Smeets, R. J., Vlaeyen, J. W., Kester, A. D. & Knottnerus, J. A. Reduction of pain catastrophizing mediates the outcome of both physical and cognitive-behavioral treatment in chronic low back pain. J. Pain. 7 (4), 261–271 (2006).

Tavares, F. A. G. et al. Additional effect of pain neuroscience education to spinal manipulative therapy on pain and disability for patients with chronic low back pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Man. Ther. 64, 102755 (2023).

Thoomes-de Graaf, M. et al. Cost-Effectiveness of pain neuroscience education and physical exercise for chronic low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. Pain Pract. 22 (4), 453–466 (2022).

Ford, S. et al. Is fear of pain a mediator in the fear avoidance model of chronic low back pain? Eur. J. Pain. 21 (6), 955–963 (2017).

Guo, J. et al. Epidemiological and genetic findings of back pain: A review. Ann. Transl Med. 11 (3), 128 (2023).

Scholten-Peeters, G. G., Verhagen, A. P., Bekkering, G. E., van der Heijden, G. J. & de Vet, H. C. Prognostic factors for recovery in acute nonspecific low back pain: A systematic review. Phys. Ther. 85 (10), 1163–1180 (2005).

Chou, R. & Huffman, L. H. Nonpharmacologic therapies for acute and chronic low back pain: A review of the evidence for an American pain society clinical practice guideline. Ann. Intern. Med. 147 (7), 492–504 (2007).

Qaseem, A., Wilt, T. J., McLean, R. M. & Forciea, M. A. Noninvasive treatments for Acute, Subacute, and chronic low back pain: A clinical practice guideline from the American college of physicians. Ann. Intern. Med. 166 (7), 514–530 (2017).

Stevans, J. M. et al. Exercise interventions for the treatment of chronic low back pain: A systematic review and Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Phys. Ther. 99 (5), 531–545 (2019).

Nijs, J. et al. Chronic pain treatment in patients with central sensitization: Do we need a different approach? Man. Ther. 16 (3), 267–274 (2011).

Luque-Suarez, A., Martinez-Calderon, J. & Falla, D. Role of kinesiophobia on pain, disability and quality of life in people suffering from chronic musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 49 (3), 305–317 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Catholic University of Valencia.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization J.V-M. and C.B; methodology J.V-M and P.B-G; software, J.V-M; formal analysis, J.V-M. and C.B; data curation, P.B-G; writing—original draft preparation, J.V-M, P.B-G and C.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vicente-Mampel, J., Blanco-Giménez, P. & Barrios, C. Influence of patient-reported outcomes on the effect of exercise therapy, manual therapy, and kinesiotaping in chronic low back pain: secondary statistical analysis. Sci Rep 15, 38400 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22260-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22260-3