Abstract

Automated microbial identification and antibiotic susceptibility testing systems (automated ID/AST systems) are widely used in clinical microbiology, yet ensuring standardized and accurate report generation remains challenging. Large language models, such as ChatGPT, offer potential for improving report consistency and objectivity through structured prompt engineering. This study evaluates the effectiveness of ChatGPT in generating standardized microbiology reports for automated ID/AST systems, compared to clinical microbiologists (CM). ChatGPT was provided with structured prompts based on clinical & laboratory standards institute (CLSI) guidelines to generate automated ID/AST systems reports. A prompt engineering framework was developed to enhance AI-generated reports. Performance was assessed across five dimensions: accuracy, relevance, objectivity, completeness, and clarity. Eight clinical cases were analyzed, comparing reports from three groups: CM, ChatGPT before prompt training (ChatGPT_BT), and ChatGPT after prompt training (ChatGPT_AT). The ChatGPT_BT group demonstrated higher relevance and completeness compared to the CM’ group (p < 0.0001 and p < 0.0001). After training, the ChatGPT_AT group produced reports with significantly improved quality across all five dimensions (p < 0.001, p < 0.0001, p < 0.0001, p < 0.0001 and p < 0.0001). Moreover, the ChatGPT_AT group showed notable improvements in relevance, objectivity, completeness, and clarity compared to the ChatGPT_BT (p < 0.001, p < 0.0001, p < 0.0001 and p < 0.05), with no significant difference in accuracy (p ≥ 0.05). ChatGPT, when guided by a structured prompt engineering process, shows significant potential in assisting CM by enhancing the objectivity, clarity, completeness, relevance, and accuracy of automated ID/AST systems reports.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In clinical microbiology, accurately verifying reports generated by automated microbial identification and antibiotic susceptibility testing systems (automated ID/AST systems) is a very important step1,2. A detailed description of the pathogen, its phenotype, quantity, and antibiotic resistance is provided in these reports3,4. As microbial automation advances, the need for quick, easy, and accurate interpretation of automated ID/AST systems reports becomes increasingly crucial.

Despite the fact that automated ID/AST systems reports offer assistance and time efficiency for clinical laboratory staff, there are potential drawbacks. Unless a laboratory has extensive experience in drug susceptibility reporting and interpretation, there is a risk of interpretation errors, antibiotic susceptibility break point judgments, as well as other information being sent directly to the client or patient5. The field of clinical microbiology is constantly evolving, such as Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) updates its guidelines annually, incorporating new sensitivity breakpoints, resistance phenotype interpretations, and new bacterial classifications. Furthermore, as new antibiotic treatments are developed, new resistant strains will also develop. The issuance of automated ID/AST systems reports is time-consuming, resource-intensive, and necessitates expert knowledge and ongoing education for clinical microbiology staff, which presents a substantial challenge for less experienced Clinical microbiologists (CM). Hence, it is necessary to explore methods for improving the quality of clinical automated ID/AST systems reports.

Large language models (LLMs) are transforming various aspects of life, and the newly launched chatbot “ChatGPT” has received significant attention and praise6. ChatGPT uses a natural language processing model based on the transformer architecture to generate human-like responses covering a wide range of topics and inquiries7,8. In particular, ChatGPT excels in the medical and healthcare fields, having been trained on a massive dataset and developed with approximately 175 billion parameters9,10. There is evidence that ChatGPT can be used to assist with clinical diagnosis11. By skillfully leveraging the complex language patterns in its training data, the LLM enables tailored and insightful responses based on a rich knowledge. CM, infectious diseases experts, and nurses can use chatbots to make diagnostic decisions regarding tests and to improve interactions with medical microbiology laboratories12. The application of ChatGPT in clinical microbiology has garnered significant attention for its potential to improve diagnostic processes13. Although ChatGPT has been studied in the field of neurosurgery14, there has been no study of its application in clinical microbiology.

We evaluated whether ChatGPT, an LLM tool, could assist in issuing automated ID/AST systems reports compared to microbiology professional recommendations. We supplied ChatGPT with a summary of the automated ID/AST systems report and utilized the hint project to assist it in generating the approval report, training it with the CLSI Guidelines (2024)15. In order to standardize the issuance process, we developed a workflow. We compared ChatGPT’s responses to CM’s suggestions based on accuracy, relevance, objectivity, completeness, and clarity16,17,18,19. The objective of this study is to assess the potential of ChatGPT in enhancing the clinical microbiology workflow, specifically by assisting in the generation and review of automated ID/AST systems reports. Our goal is to determine whether ChatGPT can offer practical assistance in improving the accuracy and standardization of clinical automated ID/AST systems report generation.

Methods

ChatGPT training

In order to prepare the content for the report generation, we provided ChatGPT with standardized summaries of automated ID/AST systems reports derived from Vitek-2 output, noting that the Vitek-2 system is widely used globally20,21 and represents a typical automated platform. All outputs were formatted according to the 2024 edition of CLSI guidelines. In this study, ChatGPT-4, the most recent version of the model at the time of research, was used due to its accuracy and context-awareness. Including the model version ensures transparency, enabling future studies to replicate or compare results reliably. The same standardized Vitek-2 outputs (with only organism names, antimicrobial susceptibility results, and alarm signal colors) were also presented to CM in the questionnaire, ensuring identical input content and format across groups. All three groups generated complete written reports for each case, ensuring directly comparable outputs.

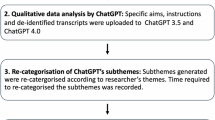

Developing the standardized review protocol

Following the CLSI (2024) standards, we trained ChatGPT using datasets provided in Supplementary Text 1. As a result of this training, a standardized review protocol was developed to ensure the accuracy and consistency of automated ID/AST systems report reviews. The protocol is illustrated in Fig. 1, which outlines key steps such as alarm interpretation, phenotypic analysis, and verification of intrinsic drug resistance mechanisms. In the GPT_AT group, structured prompts were designed to follow these steps in sequence, ensuring consistent and reproducible outputs; by contrast, GPT_BT received the same standardized inputs without stepwise prompting. The complete list of prompts used for GPT_BT and GPT_AT is available in Supplementary Text 1 to ensure transparency and reproducibility.To clarify the methodological background, although clinical microbiology laboratories routinely employ multiple approaches such as MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry for identification, selective media for screening, and molecular assays for resistance confirmation, it is important to note that both the CM group and ChatGPT were free to incorporate such complementary methodologies in their responses if considered relevant, reflecting real-world reasoning and ensuring that the evaluation captured not only data interpretation but also professional judgment.

ChatGPT training for automated ID/AST systems report review protocol. Correctly understanding automated ID/AST systems alert information (01), check the MIC value, phenotypic analysis (02), checking the original plate: whether the colony is pure and if the colony morphology matches the ID (03), verifying the accuracy of the ID, including cross-verification with different methodologies (04), validating resistance mechanisms through various methodologies (05), studying relevant papers (06), paying attention to intrinsic resistance adjustments and product insert limitations (07), and issuing an accurate report (08).

Experimental setup

Twenty hospitals in Fujian Province, China, participated in this study through their clinical microbiology laboratories. A total of 63 participants in the CM group completed the survey and provided responses. Eight representative clinical microbiology laboratory cases were collected from routine practice in the Department of Laboratory Medicine, Xiamen Chang Gung Hospital Hua Qiao University. These cases were drawn from routine clinical practice and represented common challenges encountered in daily laboratory work22,23,24,25. All cases were anonymized to protect patient privacy. The details of the eight clinical cases, including the questions, purposes, and correct solutions, are presented in Table 1, while the full case materials are provided in Supplementary Text 2. The GPT_BT and GPT_AT groups represented ChatGPT’s performance before and after prompt training, respectively, as ChatGPT operates as a single LLM. Scores were calculated based on the accuracy, relevance, objectivity, completeness, and clarity of the collected questionnaire responses (Supplementary Table 1).

Experimental grouping

We divided the participants into three groups: We divided the participants into three groups: CM (63 participants), GPT_BT (1 instance of ChatGPT), and GPT_AT (1 instance of ChatGPT). The GPT_BT and GPT_AT groups represented different configurations of the same LLM (ChatGPT), reflecting its performance before and after prompt training. Clinical microbiologists in the CM group wrote automated ID/AST systems reports empirically. Both the GPT-BT and GPT-AT groups used recommendations generated by ChatGPT, with the GPT-AT group receiving our prompt training.

Evaluation

The evaluation was blinded: experts were not informed of the group origin of each output. Outputs from all three groups (CM, GPT_BT, GPT_AT) were independently assessed by two senior clinical microbiology experts according to CLSI (2024) guidelines, which served as the gold standard. Each case was scored across five dimensions—accuracy, relevance, objectivity, completeness, and clarity—using a four-level scale (0–3; Supplementary Table 1). Scores from the two experts were averaged; if their difference exceeded one point, the experts discussed the case and reached consensus before finalizing the score. This procedure ensured reproducibility and reliability of the evaluation. For analysis, scores (including dimension-specific values, total scores, and case-level results) were summarized as mean ± standard deviation (SD). This protocol ensured that performance comparisons were based on standardized expert consensus rather than subjective impressions.

Ethics approval

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Xiamen Chang Gung Hospital (approval number XMCGIRB2024018, approval date: April 26, 2024). Electronic informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their participation in the study. The consent process was embedded at the beginning of the survey, where participants were informed that by proceeding, they agreed to participate and understood the research purpose. The study adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (Ethical Approval). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, including institutional, national, and international standards for research involving human participants.

Statistical analysis

To determine which groups had significant differences, a one-way analysis of variance was conducted using GraphPad Prism 10.0, followed by Tukey’s post hoc analysis. The statistical analysis also included descriptive statistics on participant characteristics, such as gender, years of automated ID/AST systems usage, and whether their institution is ISO15189 accredited. The significance level was set at a p value of < 0.05 (*), a p value of < 0.01(**), a p value of < 0.001 (***), or a p value of < 0.0001 (****).

Results

Establishing a standardized review protocol

As detailed in the Methodology section, a standardized review protocol (Fig. 1) was developed following the training of ChatGPT. This protocol was applied to systematically review automated ID/AST systems reports, ensuring consistency and alignment with CLSI (2024) standards. The outcomes of this application are described below.

Basic information of quality assessment participants

Table 2 shows the gender and age distribution of 63 CM who had an average of 8.6 years of experience using the automated ID/AST systems.

Comparison between GPT_BT group, GPT_AT group, and CM group

According to the evaluation results, there was no significant difference in quality of responses from CM based on gender, experience with automated ID/AST systems, or ISO15189 certification (all p ≥ 0.05; Fig. 2). Overall, the quality of automated ID/AST system reports generated by ChatGPT (GPT_BT and GPT_AT groups) was superior to that of CM group, with significantly higher mean total scores (GPT_BT:23.63 ± 7.69, GPT_AT:31.63 ± 4.31, CM:19.25 ± 3.97; GPT_BT vs. CM: p < 0.01, GPT_AT vs. CM: p < 0.0001, GPT_BT vs. GPT_AT: p < 0.001; Fig. 3F). Even without training, GPT_BT reports outperformed CM particularly in relevance (p < 0.0001; Fig. 3B) and completeness (CM:4.06 ± 0.48; p < 0.0001; Fig. 3D). Although the GPT_BT group scored higher than the CM group in accuracy (GPT_BT:6.50 ± 2.62, CM:5.95 ± 2.69; p ≥ 0.05; Fig. 3A), objectivity (GPT_BT:3.13 ± 0.99, CM:2.66 ± 0.75; p ≥ 0.05; Fig. 3C), and clarity (GPT_BT:1.88 ± 0.83, CM:1.52 ± 0.69; p ≥ 0.05; Fig. 3E), the differences were not statistically significant (Supplementary Table 2). After structured prompt engineering, GPT_AT showed substantial gains across nearly all dimensions compared to CM, including accuracy, relevance, objectivity, completeness, clarity and total scores (all p < 0.001; Fig. 3A–F; Supplementary Table 3). Compared to GPT_BT, GPT_AT responses were significantly more relevant, objective, completeness, and clarity (all p < 0.05; Fig. 3B–E; Supplementary Table 4), but not statistically significantly more accurate (p ≥ 0.05; Fig. 3A; Supplementary Table 4).

Correlation analysis of response quality within the clinical Microbiologist (CM) group. There was no significant difference in response quality based on gender (A), years of automated ID/AST system usage (B), and whether the institution was ISO15189 certified (C). The abbreviation ‘ns’ means p ≥ 0.05, indicating no statistical significance.

Bar charts for group comparisons. The clinical Microbiologist (CM) group, the ChatGPT before training (GPT_BT) group, and the ChatGPT after training (GPT_AT) group. Group comparisons were made in terms of accuracy (A), relevance (B), objectivity (C), completeness (D), clarity (E), and total score (F). *indicates statistical significance (p < 0.05), **indicates statistical significance (p < 0.01), ***indicates statistical significance (p < 0.001), ****indicates statistical significance (p < 0.0001), while ‘ns’ indicates no statistical significance (p ≥ 0.05).

Characteristics of response quality in different groups

The radar chart analysis shows that, without training, the response quality of ChatGPT was better than the CM group in terms of accuracy, relevance, and completeness, while there was no significant difference in clarity and objectivity. Despite significant improvements in clarity, accuracy, and objectivity after training, ChatGPT’s relevance and completeness did not improve significantly (Fig. 4).

Radar analysis of response characteristics across the three groups. Blue represents the clinical microbiologist (CM) group, green represents the ChatGPT_BT group, and red represents the ChatGPT_AT group. The analysis examines changes across five dimensions: accuracy, clarity, relevance, objectivity, and completeness.

Impact of the training protocol on chatgpt’s response quality

To further highlight the difference between groups, we calculated the total score differences between GPT_BT-CM and the GPT_AT-CM, defined as the mean total score of the ChatGPT before or after training minus the mean total score of CM group (a positive value indicates ChatGPT outperformed CM, whereas a negative value indicates CM outperformed ChatGPT). We found that after prompt engineering training, the quality of automated ID/AST systems reports generated by ChatGPT improved significantly. It was found that the quality of responses by the GPT_AT - CM group exceeded those of the pre-training group in case 1, case 3, case 4, case 5, case 6, case 7, and case 8 (all p < 0.0001; Fig. 5C–H), while there was no significant difference for case 2 (GPT_BT – CM: 8.16 ± 0.67, GPT_AT – CM: 8.16 ± 0.67; p ≥ 0.05; Fig. 5B). The detailed results are presented in Supplementary Table 5. Overall, the GPT_AT – CM values were consistently positive across eight clinical cases, demonstrating that after prompt engineering training, ChatGPT generated significantly higher-quality automated ID/AST systems reports than CM (case 1: 17.29 ± 0.49, case 2: 8.16 ± 0.67, case 3: 6.86 ± 0.28, case4: 9.11 ± 0.48, case 5: 14.37 ± 0.54, case 6: 13.63 ± 0.47, case 7: 21.63 ± 0.48, case 8: 16.02 ± 0.48; also see Fig. 5). In contrast, the GPT_BT – CM values varied. In case 1 (–6.71 ± 0.49; Fig. 5A) and case 3 (–1.14 ± 0.28; Fig. 5C), CM outperformed GPT_BT, reflected by negative values. However, in case 2 (8.16 ± 0.67; Fig. 5B), case 4 (3.11 ± 0.48; Fig. 5D), case 5 (11.37 ± 0.54; Fig. 5E), case 6 (10.37 ± 0.47; Fig. 5F), case 7 (12.37 ± 0.48; Fig. 5G), and case 8 (5.37 ± 0.48; Fig. 5H), GPT_BT achieved higher scores than CM.

Differences in case results before and after ChatGPT training. Case1 (A), case 2 (B), case 3 (C), case 4 (D), case 5 (E), case 6 (F), case 7 (G) and case 8 (H). GPT_BT-CM represents the difference in total scores between the GPT_BT group and the CM group, GPT_AT-CM represents the difference in total scores between the GPT_AT group and the CM group, and ΔTotal score represents the difference in total scores. **** indicates statistical significance (p < 0.0001), while ‘ns’ indicates no statistical significance (p ≥ 0.05).

Discussion

Key findings on chatgpt’s performance in automated ID/AST systems report generation

This study evaluates the potential of ChatGPT in assisting with the issuance of automated ID/AST systems reports in clinical microbiology. By implementing a training methodology grounded in the latest CLSI (2024) guidelines and established clinical workflows, we aimed to enhance ChatGPT’s capability to process complex datasets effectively. The findings indicate that utilizing ChatGPT can significantly improve report accuracy, leading to better-informed clinical decisions. In particular, the eight representative clinical cases used in this study (Table 1) covered scenarios that frequently challenge routine practice, including database limitations (Case 3), carbapenemase gene detection (Case 4), enzyme-mediated resistance mechanisms (Case 7), and novel or unclassified resistance patterns (Case 8). ChatGPT demonstrated an improved ability to provide structured and clinically relevant interpretations across these cases, underscoring its potential to support healthcare professionals in both standard and complex diagnostic contexts. This application highlights the transformative role that advanced language models can play in streamlining laboratory processes and supporting healthcare professionals in their diagnostic tasks.

Limitations of ISO15189 certification in clinical microbiology

The responses from CM were comparable to or marginally lower than those of GPT_BT (Fig. 3). Through an analysis of gender, years of automated ID/AST system usage, and whether the hospital’s department of laboratory medicine was ISO certified, we found that the quality of clinical microbiologists’ responses was not significantly correlated with these factors (Fig. 2). In Fujian, China, ISO15189 certification in hospitals does not appear to have substantially enhanced clinical microbiology standards, which may be attributable to intrinsic characteristics of the discipline. Clinical microbiology is a highly complex discipline that demands continuous learning and adaptation. The dynamic nature of microbial evolution, the diversity of pathogens, and the rapid advancement in diagnostic technologies require CM to constantly update their knowledge and skills26,27. These factors make it challenging to standardize procedures across different institutions, even with ISO15189 certification28. Moreover, the variability in resources, such as laboratory infrastructure and staff expertise, may further limit the impact of such certifications on improving clinical microbiology practices29,30,31. Therefore, achieving meaningful improvements in this field may require not only certification but also a concerted effort to promote ongoing education, invest in cutting-edge technologies, and foster collaboration between institutions to ensure consistent laboratory standards32,33. Another potential explanation is that statistical variations in sampling, such as differences in geographic region and economic status, may have influenced the results. Hospitals located in more economically developed areas may have better access to advanced technologies and more trained personnel, while those in less developed regions might struggle with limited resources, affecting the consistency and quality of microbiology testing34,35. Despite these limitations, our study provides a novel perspective that leverages ChatGPT to assist clinical microbiologists in addressing challenges associated with automated microbiology testing. While the findings are promising, future studies should validate this approach across a broader range of geographic and socioeconomic contexts to ensure its generalizability and scalability in diverse clinical settings.

Importantly, ISO15189 itself still provides substantial benefits to clinical laboratories, such as establishing standardized validation frameworks, ensuring traceability of results, and facilitating external quality assessments36. These mechanisms support the safe introduction of novel technologies, including AI-assisted tools, into routine workflows. Therefore, although our data did not show a significant performance advantage for ISO-certified institutions, the certification should be viewed as a complementary safeguard that can promote reliability and harmonization when integrating AI into clinical microbiology practice.

In addition, geographic variability in pathogen prevalence and infection rates can complicate standardization, as laboratories in different regions may encounter distinct diagnostic challenges37,38. Addressing these disparities may require a tailored approach that accounts for regional differences in resources, training, and local epidemiology39,40,41. A more equitable distribution of resources, coupled with region-specific training programs, could help harmonize clinical microbiology practices across diverse geographic and economic contexts42. To mitigate these issues, CM must continuously expand their knowledge base and stay updated with the latest advancements in the field. In this context, ChatGPT’s development of a personalized and continuously updated clinical microbiology database could significantly alleviate the knowledge constraints faced by clinical microbiologists and facilitate standardization.

Enhancing ChatGPT performance through prompt training

Based on the research findings, the quality of ChatGPT’s responses exhibited a marked improvement following prompt training utilizing our protocol (Figs. 1 and 3), particularly in the areas of clarity, accuracy, and objectivity (Fig. 4). This improvement can be attributed to several factors. First, the standardized training protocol helped eliminate human cognitive biases that might otherwise affect the consistency of report generation. Second, ChatGPT demonstrated the ability to apply a uniform set of clinical guidelines and references, ensuring that its responses adhered to established standards. Third, its capacity to process and synthesize large volumes of information without fatigue contributed to more reliable and comprehensive outputs. Additionally, the iterative feedback mechanism during training allowed the model to refine its understanding of complex microbiological concepts, further enhancing its performance compared to clinical microbiologists who may rely on subjective judgment in certain scenarios. However, there was minimal enhancement in completeness for both human participants and ChatGPT. For CM, this may be attributed to insufficient knowledge reserves, inadequate knowledge updates, and a lack of proactive engagement30. In the case of ChatGPT, the limitation is inherent to its operational logic; each conversation initiates a memory reset, and it lacks a dedicated, specialized database8. In the future, to facilitate the issuance of automated ID/AST systems reports by CM, a specialized ChatGPT microbiology knowledge base could be developed, incorporating continuously updated and verified information. Our research findings indicate that prompt engineering training significantly enhances the quality of automated ID/AST systems reports generated by ChatGPT. This conclusion aligns with the findings of previous studies, which demonstrated that, with appropriate training and guidance, LLM like ChatGPT exhibit improved capabilities in natural language processing and generation43,44. This result confirms our hypothesis that, with appropriate training and guidance, ChatGPT can become an effective tool for assisting in the issuance of high-quality automated ID/AST systems reports.

ChatGPT exhibited the highest trainability in cases 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 (Fig. 5) (p < 0.05); however, the training effect in case 2 did not show a statistically significant difference (p > 0.05). Due to the requirement of using pure colonies for testing in case 2, the training did not enhance ChatGPT’s ability to recognize this specific issue. CM also encounter similar problems. The challenges primarily stem from inefficient workflows and inadequate attention to detail. To minimize reporting errors resulting from the use of non-pure colonies, it is advisable to carefully verify the use of pure colonies before testing and to double-check the plates during report issuance. This dual verification process could significantly reduce errors associated with non-pure colonies. In cases 1 and 3, the CM group demonstrated superior performance compared to the GPT_BT group. As indicated in Table 1, in terms of accurately identifying rare bacteria that produce NDM enzymes without matching phenotypes in the expert database, the quality of responses from GPT_BT was inferior to that of CM. This issue is related to ChatGPT’s design as an intelligent question-answering tool, but it can be effectively addressed through training or the development of a specialized clinical microbiology database.

Innovations and limitations of the study

This study is distinguished by three key aspects. First, we are pioneers in utilizing a LLM, ChatGPT, to assist in generating automated ID/AST systems reports, thereby opening new possibilities for the practical application of such models in frontline clinical microbiology. Additionally, this multicenter clinical study, based on real-world data from actual clinical scenarios, provides robust scientific evidence for ChatGPT’s application as a tool to assist in the issuance of automated ID/AST systems reports12,45. Furthermore, our findings indicate that ChatGPT-generated automated ID/AST systems reports are superior to those produced by clinical microbiologists, enhancing report accuracy and, consequently, clinical diagnostic precision, which has significant implications for patient treatment outcomes. Finally, we present a new prompt engineering training method that significantly improves the quality of ChatGPT-assisted automated ID/AST systems reports through targeted training and guidance. This approach offers novel insights into the training of LLMs and holds promise for expanding their applications across various fields. Despite employing a multicenter sampling strategy, our study’s sample distribution was limited by regional and economic disparities. Previous research has highlighted significant socioeconomic differences between China’s eastern and western regions, which may influence both healthcare outcomes and access to services46,47.These factors may have affected the representativeness of our sample and should be considered when interpreting the results. To address these limitations, future studies should aim to include more geographically and economically diverse regions to enhance sample representativeness and generalizability. Additionally, incorporating standardized protocols across different healthcare settings could mitigate the variability introduced by regional disparities. Further research could also explore collaborations with international institutions to validate the findings in a global context, thereby extending the applicability of ChatGPT-assisted tools beyond the current study scope. These strategies will provide stronger evidence for the adoption of large language models like ChatGPT in diverse clinical environments and further improve the robustness of their application.

Conclusion

The results of this study hold significant value for clinical microbiology, as training ChatGPT to assist in generating automated ID/AST systems reports can enhance report generation efficiency and reduce the workload of CM.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Change history

31 October 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: The labels to the accompanying Supplementary Material 6 and Supplementary Material 7 were reversed. The original Article has been corrected.

Abbreviations

- Automated ID/AST systems:

-

Automatic microbial identification and antibiotic susceptibility testing system

- CM:

-

Clinical microbiologists

- LLM:

-

Large language model

- CLSI:

-

Clinical & laboratory standards institute

- GPT_BT:

-

ChatGPT before prompt training

- GPT_AT:

-

ChatGPT after prompt training

References

Vijayakumar, S., Biswas, I. & Veeraraghavan, B. Accurate identification of clinically important acinetobacter spp.: an update. Future Sci. OA. 5 (6), Fso395. https://doi.org/10.2144/fsoa-2018-0127 (2019). PMID: 31285840.

Albert, M. J., Al-Hashem, G. & Rotimi, V. O. Multiplex GyrB PCR assay for identification of acinetobacter baumannii is validated by whole genome Sequence-Based assays. Medical principles and practice: international journal of the Kuwait university. Health Sci. Centre. 31 (5), 493–496. https://doi.org/10.1159/000526402 (2022). PMID: 35944494.

Funke, G., Monnet, D., deBernardis, C., von Graevenitz, A. & Freney, J. Evaluation of the VITEK 2 system for rapid identification of medically relevant gram-negative rods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36 (7), 1948-52 https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.36.7.1948-1952.1998 (1998).

Lee, J. Y. H. et al. Global spread of three multidrug-resistant lineages of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Nat. Microbiol. 3 (10), 1175–1185. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-018-0230-7 (2018). PMID: 30177740.

Chan, E. & Leroi, M. Evaluation of the VITEK 2 advanced expert system performance for predicting resistance mechanisms in enterobacterales acquired from a hospital-based screening program. Pathology 53 (6), 763–767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pathol.2021.01.009 (2021). PMID: 33958177.

Gordijn, B. & Have, H. J. M. Health Care, philosophy. ChatGPT: Evol. Revolut. 26 (1), 1–2 (2023).

Bueno, J. M. T. Analysis of the Capacity of ChatGPT in Relation To the Educational System of the Dominican republic. Handbook of Research on Current Advances and Challenges of Borderlands, Migration, and Geopolitics p. 373–386 (IGI Global, 2023).

OpenAI. Introducing ChatGPT. https://openai.com/index/chatgpt/ (2022).

Karan Singhal, T. T. et al. . Towards Expert-Level Medical Question Answering with Large Language Models. Nat Med 31,943-950 https://doi.org/10.1038/s4159-024-03423-7 (2025).

Mukhida, S., Das, N. K., Kannuri, S. & Desai, D. Artificial intelligence support in health policymaking. 12 (4), 298–300 https://doi.org/10.4103/mjhs.mjhs_35_24 (2024).

Liu, S. et al. Using AI-generated suggestions from ChatGPT to optimize clinical decision support. J. Am. Med. Inf. Association: JAMIA. 30 (7), 1237–1245. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocad072 (2023). PMID: 37087108.

Egli, A., ChatGPT & GPT-4, and Other Large Language Models: The next revolution for clinical microbiology? Clin Infect Dis. 77 (9), 1322–1328. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciad407 (2023). PMID: 37399030.

Howard, A., Hope, W. & Gerada, A. ChatGPT and antimicrobial advice: the end of the consulting infection doctor? Lancet. Infect. Dis. 23 (4), 405–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(23)00113-5 (2023). PMID: 36822213.

Kuang, Y-R. et al. ChatGPT Encounters Multiple Opportunities Challenges Neurosurg.Int J Surg. 109(10),2886–2891. https://doi.prg/10.1097/JS9.0000000000000571 (2023).PMID:37352529

Institute, C. L. S. CLSI Guidelines. https://clsi.org/ (2024).

Bazzari, F. H. & Bazzari, A. H. Utilizing ChatGPT in telepharmacy. Cureus 16 (1), e52365. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.52365 (2024). PMID: 38230387.

Elkhatat, A. M. Evaluating the authenticity of ChatGPT responses: a study on text-matching capabilities. Int. J. Educational Integr. 19 (1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-023-00137-0 (2023). 2023/08/01.

He, W. et al. Physician versus large Language model chatbot responses to Web-Based questions from autistic patients in chinese: Cross-Sectional comparative analysis. J. Med. Internet. Res. 26, e54706. https://doi.org/10.2196/54706 (2024). PMID: 38687566.

Pugliese, N. et al. Accuracy, Reliability, and comprehensibility of ChatGPT-Generated medical responses for patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 22 (4), 886–889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2023.08.033 (2024). PMID: 37716618.

Zhou, M. et al. Comparison of five commonly used automated susceptibility testing methods for accuracy in the China antimicrobial resistance surveillance system (CARSS) hospitals. Infection and drug resistance. 11, 1347–1358 https://doi.org/10.2147/idr.S166790 (2018).

Carvalhaes, C. G. et al . Performance of the Vitek 2 advanced expert system (AES) as a rapid tool for reporting antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) in enterobacterales from North and Latin America. Microbiol. Spectr. 11 (1), e0467322. https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.04673-22 (2023). PMID: 36645286.

Li, X. et al. Molecular epidemiology and genomic characterization of a plasmid-mediated mcr-10 and blaNDM-1 co-harboring multidrug-resistant Enterobacter asburiae. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 21, 3885–3893. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csbj.2023.08.004 (2023). PMID: 37602227.

Findlay, J., Perreten, V., Poirel, L. & Nordmann, P. Molecular analysis of OXA-48-producing Escherichia coli in Switzerland from 2019 to 2020. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. Official Public. Eur. Soc. Clin. Microbiol. 41 (11), 1355-60 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-022-04493-6 (2022).

Ymaña, B., Luque, N., Pons, M. J. & Ruiz, J. KPC-2-NDM-1-producing Serratia marcescens: first description in Peru. New microbes and new infections. 49–50, 101051 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmni.2022.101051 (2022).

Yang, Y. & Bush, K. Biochemical characterization of the carbapenem-hydrolyzing beta-lactamase AsbM1 from Aeromonas sobria AER 14 M: a member of a novel subgroup of metallo-beta-lactamases. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 137 (2–3), 193–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08105.x (1996). PMID: 8998985.

Miller, J. M. et al. Guide to Utilization of the Microbiology Laboratory for Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases: 2024 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society for Microbiology (ASM). Clin Infect Dis. 5:ciae104. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciae104 (2024). PMID:38442248

Heinz, E. & Domman, D. Reshaping the tree of life. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15 (6), 322. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2017.51 (2017). PMID: 28496163.

Paulo, P. Trends in the accreditation of medical laboratories by ISO 15189. In: (ed Paulo, P.) Six Sigma and Quality Management. Rijeka: IntechOpen; p. (2023). Ch. 10.

Kozlakidis, Z., Vandenberg, O. & Stelling, J. Editorial: clinical microbiology in low resource settings. 7 https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2020.00258 (2020).

Reller, L. B. et al. Role of clinical microbiology laboratories in the management and control of infectious diseases and the delivery of health care. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32 (4), 605–610 . https://doi.org/10.1086/318725.(2001).PMID:11181125.

Love-Koh, J. et al. Methods to promote equity in health resource allocation in low- and middle-income countries: an overview. Globalization Health 16 (1), 6 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-019-0537-z

Outeiro, T. F. The courage to change science. EMBO Rep. 21 (3), e50124. https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.202050124 (2020). PMID: 32077198.

Meier, F. A., Badrick, T. C. & Sikaris, K. A. What’s to Be Done About Laboratory Quality? Process Indicators, Laboratory Stewardship, the Outcomes Problem, Risk Assessment, and Economic Value: Responding to Contemporary Global Challenges. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 149 (3), 186 – 196. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcp/aqx135. (2018). PMID: 29471323.

Silber, J. H. et al. Comparison of the value of nursing work environments in hospitals across different levels of patient risk. JAMA Surg. 151 (6), 527–536. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2015.4908 (2016). PMID: 26791112.

Azmatullah, A., Qamar, F. N., Thaver, D., Zaidi, A. K. & Bhutta, Z. A. Systematic review of the global epidemiology, clinical and laboratory profile of enteric fever. J. Glob. Health 5 (2), 020407 https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.05.020407 (2015). PMID: 26649174.

Wallace, P. S. et al. Quality in the molecular microbiology laboratory. Methods Mol Biol. 943, 49–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-60327-353-4_3 (2013). PMID: 23104281.

Kubes, J. N. & Fridkin, S. K. Factors affecting the geographic variability of antibiotic-resistant healthcare-associated infections in the united States using the CDC antibiotic resistance patient safety atlas. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 40 (5), 597–599. https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2019.64 (2019).

Dyck, B., Unterberg, M., Adamzik, M. & Koos, B. The impact of pathogens on sepsis prevalence and outcome. Pathogens. 13 (1), 89 https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens13010089 (2024). PMID: 10818280.

Saha, S., Gales, A. C., Okeke, I. N. & Shamas, N. Tackling antimicrobial resistance needs a tailored approach - four specialists weigh in. Nature 633 (8030), 521–524. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-02971-9 (2024). PMID: 39289501.

Wang, Z., Grundy, Q., Parker, L. & Bero, L. Variations in processes for guideline adaptation: a qualitative study of world health organization staff experiences in implementing guidelines. BMC Public. Health 20 (1), 1758. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09812-0

Hu, A. E. et al. Field epidemiology training programs contribute to COVID-19 preparedness and response globally. BMC Public Health. 22 (1), 63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12422-z (2022).PMID: 35012482.

ASM.org. Strengthening Laboratories in Resource Limited Settings. https://asm.org/Webinars/Strengthening-Laboratories-in-Resource-Limited-Set (2023).

Christoph Alt, M. H. & Leonhard, H. Fine-tuning pre-trained transformer language models to distantly supervised relation extraction. (2019). Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguisics,P1388-1398,Florence, Italy. Association for Computational Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/P19-1134.

Tianyu Gao, A. F. Danqi Chen. Making pre-trained language models better few-shot learners. (2020). Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Conputational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natual Language Processing(Volume 1: Long Papers), P3816-3830. Association for Computational Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2021.acl-long.295.

Peng, C., May, A. & Abeel, T. Unveiling microbial biomarkers of ruminant methane emission through machine learning. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1308363. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1308363 (2023). PMID: 38143860.

Wu, Q., Zhao, Y., Liu, L., Liu, Y. & Liu, J. Trend, regional variation and socioeconomic inequality in cardiovascular disease among the elderly population in China: evidence from a nationwide longitudinal study during 2011–2018. BMJ Glob. Health 8 (12), https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2023-013311 (2023). PMID: 38101937.

Levy, M. et al. Socioeconomic differences in health-care use and outcomes for stroke and ischaemic heart disease in China during 2009-16: a prospective cohort study of 0.5 million adults. Lancet Glob. Health 8 (4), e591-e602 https://doi.org/10.1016/s2214-109x(20)30078-4 (2020). PMID: 32199125.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge that no generative AI tools, including ChatGPT or other language models, were used in any part of the manuscript preparation or writing.We would like to express our gratitude to Huang Jiaming, Lin Rengui, Zhao Hongdong, and others for their assistance during the questionnaire survey. We also extend our thanks to the Research Department of Xiamen Chang Gung Hospital for providing complimentary office space throughout the completion of this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: B Li and LP Hu. Development of methodology: B Li and LP Hu. Acquisition of data: B Li, YT Zhuang and LP Hu. Analysis and interpretation of data: XH Xu, YT Zhuang and LP Hu. Writing, review, and revision of the manuscript: XH Xu, B Li, YT Zhuang and LP Hu. Administrative, technical, and material support: ML Xu, YY Lin, XH Wu, B Li and LP Hu. Study supervision: XH Xu and B Li. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Institutional review board statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Xiamen Chang Gung Hospital (approval number XMCGIRB2024018, approval date: April 26, 2024).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, L., Xu, X., Zhuang, Y. et al. Pre-trained ChatGPT for report generation in automated microbial identification and antibiotic susceptibility testing systems. Sci Rep 15, 36283 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22315-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22315-5