Abstract

Smoking is one of the most important preventable causes of chronic disease and premature death in adults worldwide. The effect of smoking on blood parameters is not well known, and the results are contradictory. The present study aimed to investigate the association between smoking status and blood parameters of adults in southwestern Iran. This cross-sectional study was conducted using data from the recruitment phase of the Fasa Adults Cohort Study (FACS). A total of 6988 adults participated. The study variables included demographic characteristics, chronic diseases, smoking status, physical activity, and blood cell parameters. Linear regression analyses were performed to examine associations between smoking status and blood parameters. Based on the multivariate linear regression results, current smokers showed higher levels of white blood cells (β = 0.89), hemoglobin (β = 0.14), mean corpuscular volume (β = 1.05), lymphocyte/monocyte ratio (β = 0.75), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (β = 0.18), and mean corpuscular hemoglobin (β = 0.50) compared to non-smokers. Additionally, mean platelet volume was significantly lower in ex-smokers (β = − 0.05) and passive smokers (β = − 0.05) compared to never-smokers. Our results indicate that cigarette smoking is linked to increased levels of specific blood cell parameters. Although smoking clearly affects various hematological measures, inconsistencies in the literature—particularly concerning indices like MPV—highlight the need for more detailed research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Smoking is one of the most important preventable causes of chronic disease and premature death in adults worldwide1. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) report, 8 million people die every year due to smoking. More than 7 million deaths are caused by direct tobacco use, and over 1 million are caused by exposure to secondhand smoke2. In addition, smoking is responsible for 13% and 4% of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in developing and developed countries3. According to evidence, smoking prevalence in low and middle-income countries such as Iran is increasing4. The average Iranian smokes 13.7 cigarettes a day, and more than 30 billion cigarettes are consumed in Iran each year5. According to Iranian studies, men and women have a smoking prevalence of 24.4 and 3.8, respectively6.

Out of the 4000 known chemicals in tobacco smoke, 60 are suspected or known to be carcinogens7. Cigarette smoke contains substances such as carbon monoxide (CO), formaldehyde, ketones, acetaldehyde, ammonia, heavy metals like cadmium (Cd), nickel, lead (Pb), arsenic, and other compounds like benzopyrenes. These substances cause tissue damage by increasing oxidative stress and inflammation8. So, smoking leads to the death of approximately half of smokers from smoking-related diseases. According to previous studies, smoking is a factor that increases the risk of pathological conditions and chronic diseases like cardiovascular diseases, cancers, atherosclerosis, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, metabolic syndrome, and some autoimmune diseases9. Smoking is the cause of 20% of deaths from coronary heart disease10. The effects of smoking on the human body and the creation of adverse consequences follow complex mechanisms. So, the exposure to free radicals from tobacco smoke leads to an increase in oxidative stress, inflammation, and DNA damage11. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and tobacco-specific carcinogenic nitrosamines present in tobacco smoke after activation create DNA adducts that escape from cell repair mechanisms and cause numerous and permanent mutations in cells12.

But it seems that the mechanism of the effect of smoking on blood parameters has been less studied. Studies suggest that nicotine in cigarettes can cause an increase in the number of leukocytes by releasing hormones that lead to an increase in their number. Also, exposure to carbon monoxide can cause an increase in hemoglobin and hematocrit levels in smokers13. In addition, carbon monoxide’s binding to hemoglobin and producing carboxyhemoglobin results in a reduction in oxygen-carrying capacity and oxygen utilization1. Some other evidence shows that smoking is responsible for the accumulation of platelets and blood clotting, which, as a result, increases the viscosity of blood and the occurrence of cardiovascular diseases. Also, smoking harms other blood parameters such as red blood cell count (RBC), hemoglobin concentration (Hb), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), and white blood count (WBC), and causes systemic inflammation in the body14. However, there are contradictory findings regarding the effect on other parameters such as RBC, WBC indices, monocytes, lymphocytes, and basophils6,13.

Based on the evidence, there are still questions about the effect of smoking on human blood parameters, and considering the limited and contradictory information about this effect in different populations, especially in Iran, there is a requirement for further research to explore this mechanism6. So, the present study was conducted to investigate the relationship between smoking status and blood parameters of adults in southwestern Iran.

Materials and methods

Study population

This cross-sectional study utilizes baseline data from the Fasa Adults Cohort Study (FACS), a subset of the Persian Cohort Study initiated in 2016. FACS aims to investigate various determinants associated with cardiovascular disease among adults in the Fasa region. The methodological protocol and study profile of FACS have been detailed in previously published literature, establishing a comprehensive framework for investigating health-related outcomes within this population15,16. Trained interviewers collected all standard questions.

Smoking status

To categorize the smoking status, we used the National Institutes of Health (NIH), which categorizes smoking status into the following main categories:

-

Current Smoker: Individuals who report smoking cigarettes at the time of assessment.

-

EX-Smoker: Individuals who have smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime but do not currently smoke.

-

Never Smoker: Individuals who have never smoked cigarettes, including those who have never tried smoking or have only experimented with it.

-

passive smoker: referred to as a secondhand smoker or environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) exposure, is someone who does not smoke but is exposed to the smoke produced by others who are smoking.

Inclusion criteria: All participants with registered baseline data in the Fasa Adults Cohort Study (FACS) were included, totaling 10,138 individuals.

Excluded criteria: Participants were excluded from the study based on the following criteria: fatty liver disease(n = 759), hepatitis B and C(n = 2), diabetes(n-1249), thyroid disorders(n = 580), cancer(n = 30), pregnancy(n = 57), incomplete blood data(n = 28), blood disorders or anemia (n = 385), and renal failure (n = 60). As a result of these exclusion criteria, a total of 6988 participants remained in the study, and 3150 were excluded. The FACS cohort study collected blood samples following a standardized protocol to ensure consistency and accuracy.

Blood parameters

Complete blood count (CBC): In the Fasa Adults Cohort Study, participants were instructed to fast for 10–14 h before their appointment. Trained personnel collected blood samples using modern equipment, labeling each sample with a unique code and storing them in appropriate tubes. Each participant provided a total of 25 mL of blood: one 7-mL clot tube and three 6-mL EDTA tubes. The Complete Blood Count (CBC) and biochemistry tests were conducted immediately upon arrival at the study’s central laboratory.

Complete blood count (CBC) tests were conducted with the Celltac-A hematology analyzer (Model MEK-6510 K; Nihon Kohden Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), which provides precise and comprehensive counts of blood cells and other hematological parameters. Biochemistry tests were performed using the BS-380 autoanalyzer (Mindray Bio-Medical Electronics Co., Ltd., Shenzhen), a fully automated instrument designed for rapid and accurate measurement of various biochemical parameters in serum and plasma samples.

White blood cells (WBC): Measures the number of white blood cells, Red Blood Cells (RBC): Indicates the number of red blood cells responsible for oxygen transport. Hemoglobin (HGB): Measures the protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen. Hematocrit (HCT): The percentage of blood volume occupied by red blood cells.

Mean corpuscular volume (MCV): Indicates the average size of red blood cells. Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin (MCH): Measures the average amount of hemoglobin per red blood cell. Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin Concentration (MCHC): Indicates the average concentration of hemoglobin in a given volume of red blood cells.

Platelets (PLT): Measures the number of platelets, which are key in blood clotting. Monocytes (Mono): A type of white blood cell involved in the immune response. Granulocytes (Gr): A category of white blood cells that includes neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils, important in fighting infections. Platelet Crit (PCT): Estimates the volume percentage of platelets in the blood. Mean Platelet Volume (MPV): Measures the average size of platelets.

Platelet distribution width (PDW): Indicates the variation in platelet size, which can be indicative of various health conditions. Lymphocyte-to-Monocyte Ratio (LMR): A ratio used to evaluate the balance between lymphocytes and monocytes, which can provide insight into immune system status.

Statistical analysis

To analyze differences in complete blood count (CBC) parameters by smoking status, we used a One-Way ANOVA test. The association between categorical variables (such as sex, marital status, occupation, and medical history) and smoking status was assessed with the Chi-Square test. For each CBC parameter, we conducted a linear regression analysis with smoking status as the independent variable and the CBC parameter as the dependent variable. Potential confounders—including age, gender, education, occupation, physical activity, hypertension, body mass index (BMI), cardiovascular disease (CVD), alcohol use, and opium use—were adjusted for by including them as covariates in the regression models. A p-value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using Stata version 14 (STATA, College Station, TX, USA).

Result

Among the 6988 older adults who participated in the study, 3863 (55.3%) were male. The mean age ± SD for current smokers was 47.37 ± 8.78 years. The study included 6988 individuals, categorized as 2168 (31.0%) never-smokers, 1648 (23.6%) current smokers, 624 (8.9%) ex-smokers, and 2548 (36.5%) passive smokers. Current smokers were significantly more likely to be male (p < 0.001). They also had the highest rates of opium use (69.7%), alcohol use (16.7%), and the longest average years of education (5.7 ± 3.8). Additionally, the prevalence of hypertension and cardiovascular disease (CVD) was significantly higher among ex-smokers compared to the other groups (p < 0.001). Baseline characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1.

The crude associations between smoking status and blood parameters are shown in Table 2. In the unadjusted analysis, current smokers had significantly higher mean values of WBC, RBC, HGB, MCV, MCH, MCHC, and LMR compared to other groups (p < 0.001).

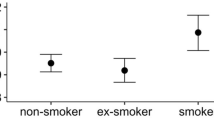

Table 3 presents the adjusted linear regression results for the association between smoking status and blood parameters. After controlling for age, gender, education, occupation, opium use, alcohol consumption, hypertension, history of CVD, physical activity, and BMI, multiple linear regression showed that current smoking was significantly positively associated with WBC counts (β = 0.89, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.02). Current smokers also had higher mean HGB levels (β = 0.14, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.24) than never smokers. Additionally, being a current smoker was positively associated with MCV (β = 1.05, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.60). MCH (β = 0.50, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.73) and MCHC (β = 0.18, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.27) levels were also significantly elevated in current smokers compared with never smokers. Monocyte levels were lower in current smokers than never smokers (β = − 0.21, 95% CI − 0.32 to − 0.10).

Moreover, mean MPV was significantly lower in both ex-smokers (β = − 0.05, 95% CI − 0.09 to − 0.01) and passive smokers (β = − 0.05, 95% CI − 0.09 to − 0.01) compared to the reference group. Finally, current smoking was positively associated with increased LMR (β = 0.75, 95% CI 0.34 to 1.16).

Discussion

Smoking is a major health risk worldwide. While many of its effects are well known, its impact on hematological indices remains debated. This study examined the association between cigarette smoking status and complete blood cell parameters. The results showed that 23.5% of participants were current smokers, 9% were former smokers, and 36.5% were passive smokers. Most active smokers were men, with 69.9% reporting opium use and 15.7% alcohol consumption. The prevalence of high blood pressure and cardiovascular diseases was 17.1% each and was significantly higher among former smokers. The mean BMI was significantly lower in current smokers compared to other groups, while former smokers had a mean BMI similar to non-smokers.

After adjusting for potential confounders including age, sex, education, occupation, opium use, alcohol use, history of hypertension, cardiovascular disease, physical activity, and body mass index, active smokers showed significantly higher levels of WBC, HGB, MCV, MCH, and MCHC compared to non-smokers. Additionally, monocyte levels were lower and LMR levels were significantly higher in active smokers. The study also found that former and passive smokers had significantly lower average MPV levels. Consistent with existing evidence, our findings indicate that the BMI of active smokers is significantly lower than that of non-smokers, former smokers, and passive smokers17. Notably, the BMI of ex-smokers after quitting is comparable to that of individuals who have never smoked18. The mechanisms by which smoking reduces body weight are complex and not fully understood. However, existing evidence suggests that nicotine in cigarettes can reduce weight by increasing energy expenditure and suppressing appetite19,20. The findings of our study confirm the existing evidence that the prevalence of opium and alcohol consumption is higher in smokers compared to non-smokers21. A cross-sectional study in Afghanistan found that cigarette smoking was significantly associated with opium use. Specifically, opium users were 23 times more likely to smoke cigarettes than non-opium users, indicating a strong association between these behaviors21. In our study, the prevalence of high blood pressure and cardiovascular diseases was notably higher among ex-smokers compared to non-smokers, current smokers, and passive smokers. This finding may reflect the long-term health impacts of smoking. In contrast, Ahmed et al.13 did not find a significant relationship between smoking status and age, weight, or blood pressure. This discrepancy might be attributed to their method of categorizing smoking status, which was limited to just two groups: smokers and non-smokers. Our findings demonstrate that cigarette smoking has severe adverse effects on hematological parameters, including WBC, HGB, MCV, MCH, and MCHC. Specifically, the WBC count in active smokers was significantly higher than that in non-smokers, passive smokers, and ex-smokers, aligning with numerous studies in the literature22,23. The WBC counts in passive and ex-smokers were similar to those in non-smokers, potentially indicating the short-term effects of smoking on WBC levels. Consistent with our results, Higuchi et al.24 reported a decrease in WBC count following smoking cessation. Conversely, Ahmed et al.13 found that WBC counts were higher in all groups of smokers compared to non-smokers. Supporting these findings, a recent cross-sectional study from the TABARI cohort in Iran, involving over 4000 adult males, also demonstrated that total WBC counts, specific WBC subtypes, and several inflammatory indices were significantly elevated in smokers compared to non-smokers. Notably, the study reported a clear dose-dependent relationship, whereby greater smoking exposure was associated with higher WBC counts and inflammatory ratios. These results underscore a consistent pattern of smoking-related systemic inflammation in the Iranian population and further validate the relevance of our findings in the context of national public health concerns23.

The exact mechanism by which smoking affects WBC counts is not fully understood. However, current evidence suggests that particles and gases in cigarette smoke trigger systemic inflammatory responses, which may explain the observed increase in WBC levels9,25. The findings of our study confirm the existing evidence regarding the effect of smoking on increasing hemoglobin levels9. The mechanisms behind smoking-related increases in blood hemoglobin levels are complex and mainly involve carbon monoxide (CO) binding to hemoglobin (HGB). The elevated hemoglobin concentration in smokers is believed to be a compensatory response to reduced oxygen delivery caused by carboxyhemoglobin. CO binds to hemoglobin, forming carboxyhemoglobin, an inactive form that cannot carry oxygen. This binding also shifts the hemoglobin dissociation curve to the left, further reducing hemoglobin’s ability to release oxygen to tissues. As a result, smokers maintain higher hemoglobin levels to offset this impaired oxygen delivery26. MCV, MCH, and MCHC are important red blood cell indices that reflect the average size and hemoglobin content of red blood cells. Our study found significantly higher MCV, MCH, and MCHC values in current smokers compared to non-smokers. This finding is consistent with multiple studies, including a large cohort from the Iranian Kurdish population, which also reported significantly higher MCV, MCH, and MCHC levels in current smokers, supporting the consistency of this hematological response across different Iranian populations6. The observed increases in MCV, MCH, and MCHC among current smokers may result from chronic hypoxia caused by cigarette smoke exposure. This low-oxygen state activates hypoxia-inducible factors, especially HIF-2, which stimulate erythropoietin (EPO) production and increase intestinal iron absorption, promoting enhanced erythropoiesis. Additionally, oxidative stress from smoking can impair DNA synthesis in erythroid precursor cells, leading to the production of larger red blood cells with higher hemoglobin content. Together, these mechanisms indicate a physiological adaptation to smoking-induced hypoxia27,28.

However, the values of MCV, MCH, and MCHC among passive smokers and ex-smokers were lower and not statistically significant. Similarly, the study by Schmitt et al.1 found that smokers had higher levels of hemoglobin, MCV, MCH, and MCHC compared to non-smokers and ex-smokers, indicating the short-term effects of smoking on these indices. In contrast to our findings, the study by Salamzadeh reported that the levels of MCH and MCHC in smokers were significantly lower than those in non-smokers29.

The findings of our study did not show a significant relationship between active smoking and mean platelet volume (MPV), but ex-smokers and passive smokers had significantly lower mean MPV levels. In line with our findings, Arslan et al.30 also reported no significant difference in MPV between smokers and non-smokers, Other studies suggest a statistically significant decrease in MPV after smoking cessation31.

We do not know the exact cause of the decrease in MPV values after smoking cessation, but it may reflect a reduction in systemic inflammation and normalization of platelet function. One possible explanation is that continuous exposure to smoke in current smokers maintains platelet activation and turnover, resulting in stable or even elevated MPV. In contrast, in ex-smokers and passive smokers, lower levels of exposure or cessation may lead to decreased inflammatory stimulation and the release of smaller, less reactive platelets. This hypothesis is supported by evidence showing that MPV can decrease after smoking cessation31. However, some studies have reported significantly higher MPV values in smokers compared to non-smokers, which contrasts with our findings. These discrepancies might be due to differences in study design, sample size, population characteristics, and intensity or duration of smoking. For example, variations in age, sex distribution, or the degree of tobacco exposure may affect MPV levels31,32. Finally, our study found that lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR) levels were significantly higher in active smokers, which aligns with existing evidence in this field33.

Limitations study

We cannot assess causality because of the cross-sectional nature of our study. The second limitation of this study is the grouping of ex-smokers into one group, although these individuals can vary greatly in their past smoking duration and the time since quitting smoking. But we were unable to conduct subgroup analyses due to the incomplete information in this group. Third, the smoking status variable, provided by the cohort team, was limited to a validated four-category NIH classification: Never, Current, Ex-smoker, and Passive smoker. It did not include detailed information on smoking intensity (e.g., cigarettes per day) or duration of exposure, which restricted our capacity to perform dose-response analyses. Fourth, this study’s findings could be influenced by recall bias or social desirability bias since smoking status relies on self-reported data. Fifth, another limitation of the present study is the inability to adjust for confounding factors such as dietary habits, hydration status, acute infections, occupational exposures, or socioeconomic status, although calorie intake was adjusted in the modeling to reflect the nutritional profile of the subjects. Finally, due to the lack of stratified analysis based on age and sex, the results of this study cannot assess how these differences might influence hematological responses to smoking. Although age and gender were adjusted for in the modeling, performing stratified analyses by gender and different age groups in future studies could help understand these differences.

Conclusion

This study provides significant insights into the relationship between smoking status and various hematological parameters. Our findings confirm that active smoking is associated with increased levels of white blood cells (WBC), hemoglobin (HGB), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC). Our study also highlighted the impact of smoking on body mass index (BMI) and the prevalence of high blood pressure and cardiovascular diseases, particularly among ex-smokers. These results highlight the complex relationship between smoking, body weight, and cardiovascular health. While the effects of smoking on many hematological parameters are clear, inconsistencies in the literature—particularly regarding indices like MPV—indicate the need for cautious interpretation and more detailed investigation. Future research should focus on resolving these discrepancies by thoroughly controlling for confounders and exploring the underlying mechanisms to better understand smoking’s overall impact on blood health.

Data availability

Data inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- FACS:

-

Fasa adults cohort study

- WHO :

-

World Health Organization

- DALYs:

-

Disability-adjusted life years

- CO :

-

Carbon monoxide

- Cd :

-

Cadmium

- RBC :

-

Red blood cell count

- Hb :

-

Hemoglobin concentration

- MCV :

-

Mean corpuscular volume

- MCH :

-

Mean corpuscular hemoglobin

- WBC :

-

White blood count

- NIH :

-

National Institutes of Health

- ETS :

-

Environmental tobacco smoke

- CBC :

-

Complete blood count

- HCT :

-

Hematocrit

- HGB :

-

Hemoglobin

- MCHC :

-

Mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration

- PLT :

-

Platelets

- Mono :

-

Monocytes

- PDW :

-

Platelet distribution width

- PCT :

-

Platelet crit

- Gr:

-

Granulocytes

- BMI :

-

Body mass index

- CVD :

-

Cardiovascular disease

- EPO :

-

Erythropoietin

References

Schmitt, M. et al. Smoking is associated with increased eryptosis, suicidal erythrocyte death, in a large population-based cohort. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 3024 (2024).

WHO. tobacco 2023 [Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco

Varmaghani, M. et al. Prevalence of smoking among Iranian adults: Findings of the National steps survey 2016. Arch. Iran. Med. 23 (6), 369–377 (2020).

Naghizadeh, S. et al. Prevalence of smoking, alcohol consumption, and drug abuse in Iranian adults: Results of Azar cohort study. Health Promotion Perspect. 13 (2), 99 (2023).

Aslani, M. et al. Prevalence of cigarette smoking and its related factors among students in iran: A meta-analysis. Tanaffos 21 (3), 271 (2022).

Shakiba, E. et al. Tobacco smoking and blood parameters in the Kurdish population of Iran. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 23 (1), 401 (2023).

Meysamie, A. et al. Pattern of tobacco use among the Iranian adult population: Results of the National survey of risk factors of Non-Communicable diseases (SuRFNCD-2007). Tob. Control 19 (2), 125–128 (2010).

Wang, J., Wang, Y., Zhou, W., Huang, Y. & Yang, J. Impacts of cigarette smoking on blood circulation: Do we need a new approach to blood donor selection? J. Health Popul. Nutr. 42 (1), 62 (2023).

Malenica, M. et al. Effect of cigarette smoking on haematological parameters in healthy population. Med. Arch. 71 (2), 132 (2017).

Hahad, O., Kuntic, M., Kuntic, I., Daiber, A. & Münzel, T. Tobacco smoking and vascular biology and function: Evidence from human studies. Pflügers Arch.-Eur. J. Physiol. 475 (7), 797–805 (2023).

Onor, I. O. et al. Clinical effects of cigarette smoking: Epidemiologic impact and review of pharmacotherapy options. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 14 (10), 1147 (2017).

Kispert, S. & McHowat, J. Recent insights into cigarette smoking as a lifestyle risk factor for breast cancer. Breast Cancer: Targets Therapy 127–132 (2017).

Ahmed, I. A., Mohammed, M. A., Hassan, H. M. & Ali, I. A. Relationship between tobacco smoking and hematological indices among Sudanese smokers. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 43 (1), 5 (2024).

Siddiqui, N. et al. Variation in hematological parameters due to tobacco cigarette smoking in healthy male individuals. Prof. Med. J. 30 (02), 264–269 (2023).

Farjam, M. et al. A cohort study protocol to analyze the predisposing factors to common chronic non-communicable diseases in rural areas: Fasa cohort study. BMC Public Health 16, 1–8 (2016).

Homayounfar, R. et al. Cohort profile: The Fasa adults cohort study (FACS): A prospective study of non-communicable diseases risks. Int. J. Epidemiol. 52 (3), e172–e8 (2023).

Jacobs, M. Adolescent smoking: The relationship between cigarette consumption and BMI. Addict. Behav. Rep. 9, 100153 (2019).

Audrain-McGovern, J. & Benowitz, N. Cigarette smoking, nicotine, and body weight. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 90 (1), 164–168 (2011).

Hofstetter, A., Schutz, Y., Jéquier, E. & Wahren, J. Increased 24-hour energy expenditure in cigarette smokers. N. Engl. J. Med. 314 (2), 79–82 (1986).

Perkins, K. A. Metabolic effects of cigarette smoking. J. Appl. Physiol. 72 (2), 401–409 (1992).

Hamrah, M. S. et al. The prevalence and associated factors of cigarette smoking and its association with opium use among outpatients in afghanistan: A cross-sectional study in Andkhoy City. Avicenna J. Med. 9 (04), 129–133 (2019).

Pedersen, P. et al. Smoking and increased white and red blood cells: A Mendelian randomization approach in the Copenhagen general population study. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 39 (5), 965–977 (2019).

Ghadirzadeh, E. et al. The association between smoking profile, leukocyte count, and inflammatory indices in males: A cross-sectional analysis of the TABARI cohort study at enrollment phase. Inhal Toxicol. 37 (3), 146–155 (2025).

Higuchi, T. et al. Current cigarette smoking is a reversible cause of elevated white blood cell count: Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Prev. Med. Rep. 4, 417–422 (2016).

Qiu, F. et al. Impacts of cigarette smoking on immune responsiveness: Up and down or upside down? Oncotarget 8 (1), 268 (2017).

Patel, S. J. A., Mohiuddin, S. S. & Physiology Oxygen Transport And Carbon Dioxide Dissociation Curve. [Updated 2023 Mar 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; (2024). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539815/

Haase, V. H. Regulation of erythropoiesis by hypoxia-inducible factors. Blood Rev. 27 (1), 41–53 (2013).

Malenica, M. et al. Effect of cigarette smoking on haematological parameters in healthy population. Med. Arch. 71 (2), 132–136 (2017).

Salamzadeh, J. The hematologic effects of cigarette smoking in healthy men volunteers. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. (Supplement 2), 41. (2010).

Arslan, E., Yakar, T. & Yavaşoğlu, İ. The effect of smoking on mean platelet volume and lipid profile in young male subjects. Anadolu Kardiyoloji Dergisi: AKD = Anatol. J. Cardiol. 8 (6), 422–425 (2008).

Varol, E. et al. Effect of smoking cessation on mean platelet volume. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 19 (3), 315–319 (2013).

Liu, C. et al. Passive smoke exposure was related to mean platelet volume in never-smokers. Am. J. Health Behav. 38 (4), 519–528 (2014).

Hsueh, C. et al. The prognostic value of preoperative neutrophils, platelets, lymphocytes, monocytes and calculated ratios in patients with laryngeal squamous cell cancer. Oncotarget 8 (36), 60514 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Fasa University of Medical Sciences for their support of this research.

Funding

This research was supported by Fasa University of Medical Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MSH and SF provided the study’s main idea and methodology. MSH, NB, and PB were responsible for the final analysis, developing the idea, and revising the final manuscript. EH, MR and NB contributed to developing the idea and revising the final manuscript. AM assisted with data analysis and manuscript revision. All authors approved the final version of the submitted manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The authors adhered to ethical standards concerning plagiarism, informed consent, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy, and related issues. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines. Baseline data from the FACS were analyzed; informed consent was obtained from all participants at the enrollment phase. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Fasa University of Medical Sciences (IR.FUMS.REC.1402.093).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sharafi, M., Haghjoo, E., Bagheri, P. et al. Association between smoking status and complete blood cell parameters in baseline data from the Fasa adults cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 38340 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22324-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22324-4