Abstract

Wild barley (Hordeum vulgare subsp. spontaneum) germplasm is a valuable genetic resource for improving cultivated barley. The western regions of Iran, natural habitats for diverse wild barley populations, offer rich genetic diversity for enhancing economically important traits. This study examined 114 genotypes from western Iran, assessing their agro-morphological and physiological traits under both irrigated and rainfed conditions. The goal was also to identify informative SSR markers associated with these traits. Field trials were conducted over two agricultural years (2020–2021 and 2021–2022) using an augmented design with nine control genotypes. Significant variations in agronomic and physiological traits were observed, highlighting the interactive effects of genotype and environmental conditions. Genotype by environment interaction revealed significant differences at the 1% and 5% probability levels for traits other than spike length, number of seeds per spike, and flag leaf length. Population structure analysis classified these genotypes into 7 subpopulations. Marker-trait associations identified SSR markers linked with stress tolerance and yield-related traits. Notably, markers EBMAG0781, BMAG0323, and SCSSR04163 exhibited significant associations with various morphological and physiological traits under both conditions. These findings emphasize the extensive genetic diversity present in wild barley and its potential for breeding programs aimed at enhancing barley’s adaptation to diverse environmental.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wild relatives of crop plants have a high potential for tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses. Studies on drought tolerance in wild and cultivated barley indicate that certain tolerance strategies are present in wild parents, which have been weakened in the domestication and cultivation of barley, focusing on yield and agronomic traits1. Currently, significant attention is given to wild species and primitive barley landraces, which can serve as rich sources of genetic diversity for improving cultivated varieties. Wild barley, such as H. spontaneum, has been used as a source of resistance genes for diseases like powdery mildew, rust, barley leaf scorch, and leaf blotch. Additionally, this species is crucial for providing genetic variations in economic traits2.

Genetic diversity in wild barley, particularly H. spontaneum, plays a crucial role in breeding stress-resistant cultivars. Studies have shown that wild barley accessions exhibit significant genetic variability in their resistance to phytotoxic aluminum ions, making them valuable genetic resources for developing high-yielding cultivars adapted to specific environmental conditions3. Additionally, crop wild gene flow in barley populations, such as H. agriocrithon, has led to the emergence of hybrid forms with characteristics of both wild and domesticated barley, contributing to the genetic diversity of the species4. The genetic erosion of traditional barley varieties in regions like Ethiopia highlights the importance of conserving genetic resources to meet future food needs and enhance agricultural sustainability5.

Furthermore, genomic studies on wild barley populations have revealed insights into the genomic basis of local adaptation, highlighting the role of structural variants and gene expression patterns in response to abiotic stress, such as drought tolerance and flowering time adaptation, which are essential for genetic improvement in cultivated barley6. Wild barley varieties and landraces show promise in providing novel opportunities for enhancing abiotic stress tolerance in crops, particularly under changing climatic conditions, emphasizing the potential of utilizing wild relatives in breeding programs for improved resilience in barley cultivation7.

In plant breeding, understanding the extent of genetic diversity and the distance between individuals is extremely important because genetic diversity is a cornerstone of sustainable agriculture8,9. Today, molecular markers are widely used to study genetic diversity. Markers based on polymerase chain reaction (PCR), such as AFLP and SSR, are more effective in studying genetic diversity10.

One of the most important applications of molecular markers in breeding programs is their use in identifying superior individuals in segregating populations, identifying trait-controlling regions, and determining gene loci. One of the most important methods of quantitative genetics that allows for the precise dissection of quantitative traits and understanding of the relationship between gene loci and phenotypic traits is linkage mapping and association mapping or linkage disequilibrium mapping11.

Studying the relationships between molecular markers and agronomic traits has multiple applications, such as the potential to evaluate the genetic potential of specific genotypes before phenotypic evaluations, identifying desirable trait alleles in germplasm collections, facilitating the precise localization of QTLs, and validating candidate genes responsible for quantitative traits like stability and drought resistance12.

Identifying molecular markers associated with major genes controlling target traits has been achieved in recent years through the development of segregating populations such as F1 in heterozygous plants, F2, RIL, and DH in homozygous plants. Some molecular markers have been used for breeding purposes; however, limitations such as the unavailability of segregating populations for mapping, insufficient time, and lack of sufficient correlation between morphological traits and molecular markers have hindered the identification of markers associated with morphological traits. However, regression correlation analysis does not have these limitations13.

The goal of linkage mapping is to identify markers linked to a quantitative trait in a related population. This localization is based on establishing a statistical relationship between alleles controlling a quantitative trait and is widely used in plant populations. In contrast, association mapping uses a large collection of randomly collected individuals and maps based on linkage disequilibrium. Given that linkage mapping has high statistical power and repeatability14,15, association analysis is an alternative method to overcome the limitations of using quantitative trait mapping. This method examines the correlation between genotype and phenotype traits in unrelated individuals. Moreover, this method uses a broad source, unlike quantitative trait mapping16,17,18.

Given the above, this study aims to investigate and analyze the relationship between the germplasm of wild barley (H. spontaneum) in terms of agro-morphological and physiological traits using SSR and EST-SSR molecular markers. This research seeks to identify and understand the genetic and phenotypic patterns of this species under different environmental conditions, to utilize this information for the improvement and development of cultivated barley varieties with desirable traits, such as drought resistance and high productivity.

Results

Analysis of variance

Based on the results of Table 1, the trait’s spike length (SL) and number of seeds per spike (NSPS) were not significant across the years. Additionally, the interaction effects of the year by environment and genotype by year for flag leaf length (FLL) showed no significant differences. Spike length (SL) was also non-significant for the interaction effects of year by genotype, environment by genotype, and year by environment by genotype. Similarly, the interaction effects of the year by genotype and environment by genotype for the trait number of seeds per spike (NSPS) did not show significant differences. Other studied traits showed significant differences at the 1% and 5% probability levels. This indicates a varying response pattern of genotypes under different environmental conditions.

Comparison of mean and descriptive statistics for agro-morphological traits

The results of Table 2 highlight high coefficients of variation (CV) under both rainfed and irrigated conditions for traits such as Xteragen Length (XL), flag leaf length (FLL), straw yield (SY), and grain yield (GY) only in rainfed conditions. This indicates significant variability among the wild barley genotypes for these traits. The highest CVs (30.9% and 28.2%) were observed for straw yield (SY) under both rainfed and irrigated conditions, respectively. In contrast, Plant Height (PH) exhibited the lowest CV under both conditions. Due to the extensive amount of information, a supplementary table has been included in the Supplementary Table S4 and S5.

The mean plant height (PH) in rainfed and irrigated conditions was 80.67 and 90.88, with a standard deviation of 7.57 and 8.24, respectively. The highest plant height (PH) was observed in genotypes 88, 64, 32, 33, 31, 107, 35, 74, 75, and 84, while the lowest plant height (PH) was observed in genotypes 17, 30, 106, 114, 34, 56, 4, 19, 26, and 78 in the rainfed conditions. Additionally, genotypes 88, 35, 33, 44, 49, 107, 70, 42, 84, and 87 exhibited the highest plant height (PH) in irrigated conditions, while genotypes 56, 106, 17, 19, 23, 114, 30, 26, 67, and 78 had the lowest plant height (PH).

The mean xteragen length (XL) in rainfed and irrigated conditions was 13.88 and 17.39, with standard deviations of 3.21 and 3.96, respectively. Genotypes 114, 52, 19, 34, 78, 101, 57, 24, 38, and 47 had the lowest xteragen length (XL), while genotype 70, 87, 48, 88, 94, 21, 42, 6, 3, and 7 had the highest xteragen length (XL) in the rainfed conditions. In the irrigated conditions, genotypes 114, 19, 52, 34, 101, 24, 57, 90, 106, and 9 had the lowest xteragen length (XL), while genotypes 42, 48, 89, 51, 32, 70, 88, 21, 87, and 94 had the highest xteragen length (XL).

In rainfed conditions, the mean spike length (SL) was 9.35 with a standard deviation of 7.5. In irrigated conditions, it was 11.20 and 8. Genotypes number 107, 33, 8, 12, 88, 35, 36, 40, 41, and 57 had the highest spike length (SL), while genotypes number 95, 34, 51, 55, 56, 93, 97, 102, 106, and 113 had the lowest spike length (SL) in the rainfed conditions. Similarly, in irrigated conditions, genotypes 93, 4, 2, 5, 48, 55, 56, 59, 66, and 67 had the lowest spike length (SL), while genotypes 107, 33, 71, 8, 12, 34, 36, 41, 62, and 88 had the highest spike length (SL).

The mean awn length (AL) under rainfed and irrigated conditions was 11.20 and 14.30, with standard deviations of 1.73 and 1.93, respectively. Genotypes 5, 9, 15, 10, 51, 65, 91, 100, 103, and 113 exhibited the lowest awn length (AL), while genotypes 12, 78, 88, 70, 38, 89, 13, 34, and 61 had the highest awn length (AL) in the rainfed conditions. Similarly, genotypes 15, 33, 5, 52, 60, 65, 95, 111, 60, 1, and 114 displayed the lowest awn length (AL), whereas genotypes 88, 78, 12, 69, 34, 11, 38, 41, 46, and 76 exhibited the highest awn length (AL) in the irrigated conditions.

In rainfed conditions, the mean flag leaf length (FLL) was 7.07 with a standard deviation of 2.06, while in irrigated conditions it was 9.12 with a standard deviation of 1.21. Genotypes 58, 78, 79, 84, 90, 102, 114, 66, 67, and 77 had the lowest flag leaf length (FLL), whereas genotypes 107, 32, 87, 11, 41, 32, 86, 88, 4, 10, and 98 had the highest flag leaf length (FLL) in the rainfed conditions. Additionally, genotypes 84, 90, 58, 24, 45, 73, 78, 102, 16, and 18 had the lowest flag leaf length (FLL) in the irrigated conditions, while genotypes 107, 86, 87, 88, 44, 41, 47, 70, 32, and 89 had the highest flag leaf length (FLL).

The mean of 100-kernel weight (TSW) in rainfed and irrigated conditions was 4.67 and 5.78, with a standard deviation of 0.848 and 1.130, respectively. Genotypes 103, 51, 14, 25, 39, 107, 47, 9, 56, and 13 have the lowest 100-kernel weight (TSW), while genotype 113, 73, 88, 86, 97, 78, 84, 85, 12, and 77 have the highest 100-kernel weight (TSW) in the rainfed conditions. Additionally, genotypes 103, 96, 51, 25, 39, 107, 47, 9, 56, and 13 exhibit the lowest 100-kernel weight (TSW), while genotypes 72, 73, 113, 6, 114, 86, 88, 66, 69, and 78 display the highest 100-kernel weight (TSW).

The mean number of seeds per spike (NSPS) in rainfed and irrigated conditions was 24.50 and 28.35, with standard deviations of 3.63 and 3.21, respectively. Genotypes 1, 6, 11, 56, 72, 113, 17, 25, 26, and 41 had the lowest number of seeds per spike (NSPS), while Genotypes 8, 42, 48, 62, 74, 86, 97, 31, 32, and 107 had the highest number of seeds per spike (NSPS) in the rainfed conditions. In the irrigated conditions, genotypes 1, 4, 9, 11, 26, 71, 72, 73, 77, and 113 had the lowest number of seeds per spike (NSPS), while genotypes 97, 107, 7, 32, 34, 62, 8, 47, 48, and 42 had the highest number of seeds per spike (NSPS).

The mean straw yield (SY) in rainfed and irrigated conditions was 4.67 and 5.78, with a standard deviation of 0.848 and 1.130, respectively. In rainfed conditions, genotypes 1, 3, 18, 19, 50, 55, 56, 39, 96, and 103 had the lowest straw yield (SY), while genotypes 31, 33, 35, 38, 62, 65, 84, 53, 44, and 88 had the highest straw yield (SY). In irrigated conditions, genotypes 5, 12, 17, 18, 39, 55, 3, 23, 21, and 56 had the lowest straw yield (SY), whereas genotypes 33, 35, 70, 74, 79, 84, 83, 53, 114, and 88 had the highest straw yield (SY).

In rainfed conditions, the mean grain yield (GY) was 1.10 with a standard deviation of 0.786, while in irrigated conditions it was 1.80 with a standard deviation of 0.324. Genotypes 88, 97, 86, 62, 113, 74, 12, 85, and 75 exhibited the highest grain yield (GY), whereas Genotypes 72, 56, 25, 51, 1, 103, 67, 17, 50, and 6 had the lowest grain yield (GY) in the rainfed conditions. Similarly, in irrigated conditions, genotypes 113, 86, 88, 97, 62, 66, 6, 114, 85, and 73 showed the highest grain yield (GY), while genotypes 103, 25, 51, 13, 26, 56, 29, 18, 67, and 17 had the lowest grain yield (GY).

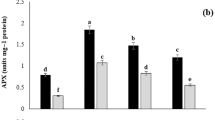

Comparison of mean and descriptive statistics for physiological traits

Table 3 displays the minimum, maximum, mean, range of changes, standard deviation, standard error, coefficient of variation, and the results of the LSD test at the 5% and 1% probability levels for the traits measured in both rainfed and irrigated conditions. The descriptive statistics reveal a significant diversity among wild barley genotypes in terms of physiological characteristics. Based on the coefficient of variation, the RWL trait exhibited the highest amount in both rainfed and irrigated conditions, while the lowest amount was observed in the chlorophyll a trait. Due to the extensive amount of information, a supplementary table has been included in the Supplementary Table S4 and S5.

The mean relative water content (RWC) in rainfed and irrigated conditions was 47.59 and 61.30, with a standard deviation of 8.90 and 8.55, respectively. Genotypes 1, 56, 89, 51, 68, 103, 96, 90, 41, and 55 exhibited the lowest RWC, while genotypes 12, 5, 75, 79, 88, 74, 16, 15, 97, and 86 showed the highest RWC. RWC was measured in rainfed conditions. Additionally, genotypes 51, 18, 17, 1, 13, 89, 56, 9, 11, and 19 had the lowest RWC, while genotypes 6, 79, 5, 62, 74, 12, 94, 81, 15, and 97 had the highest RWC.

In rainfed conditions, the mean relative water loss (RWL) was 23.67, with a standard deviation of 5.68, and in irrigated conditions, it was 29.50 and 5.57, respectively. Genotypes 62, 12, 15, 20, 77, 88, 16, 8, 35, and 4 had the lowest RWL, while genotypes number 103, 96, 72, 74, 69, 56, 51, 64, 114, and 102 had the highest RWL in the rainfed conditions. Similarly, in irrigated conditions, genotypes 5, 12, 15, 16, 8, 7, 62, 10, 61, and 20 exhibited the lowest RWL, while genotypes 92, 70, 68, 69, 96, 102, 66, 64, 51, and 79 had the highest RWL.

The mean chlorophyll a content in rainfed and irrigated conditions was 4.15 and 7.29, with standard deviations of 0.51 and 0.77, respectively. In rainfed conditions, genotypes 65, 108, 109, 56, 1, 22, 51, 50, 17, and 112 exhibited the lowest levels of chlorophyll a, while genotypes 88, 77, 73, 64, 97, 78, 86, 12, 85, and 15 had the highest levels. Similarly, genotypes 1, 13, 26, 51, 18, 17, 103, 29, 11, and 112 showed the lowest chlorophyll a levels, while genotypes 62, 61, 66, 6, 5, 73, 12, 15, 86, and 88 exhibited the highest levels in the irrigated conditions.

In rainfed conditions, the mean chlorophyll b content was 2.45, with a standard deviation of 0.47, while in irrigated conditions, it was 4.62 and 0.71. Genotypes 1, 56, 51, 17, 50, 41, 6, 55, 60, and 9 had the lowest chlorophyll b levels in the rainfed conditions, while genotypes 62, 35, 12, 61, 32, 15, 88, 33, 77, and 108 exhibited the highest levels. Additionally, genotypes 110, 103, 71, 106, 30, 112, 102, 51, 78, and 98 showed the lowest chlorophyll b levels, while genotypes 86, 88, 62, 61, 97, 44, 34, 35, 32, and 85 had the highest levels in the irrigated conditions.

The mean total chlorophyll in rainfed and irrigated conditions was 6.61 and 11.91, with a standard deviation of 0.91 and 1.32, respectively. Genotypes 1, 56, 51, 17, 50, 41, 6, 55, 60, and 103 had the lowest total chlorophyll, while genotypes 88, 77, 73, 12, 62, 35, 78, 97, 15, and 86 had the highest total chlorophyll in the rainfed conditions. Similarly, genotypes 1, 56, 51, 17, 50, 41, 6, 55, 60, and 103 had the lowest total chlorophyll, and genotypes 88, 77, 73, 12, 62, 35, 78, 97, 15, and 86 had the highest total chlorophyll in the irrigated conditions.

In the rainfed condition, the mean carotenoid level was 10.65, with a standard deviation of 1.60, while in the irrigated condition, it was 15.59, with a standard deviation of 1.47. In rainfed conditions, genotypes 114, 12, 62, 35, 15, 88, 61, 32, 20, and 33 exhibited the highest carotenoid levels, whereas genotypes 1, 56, 51, 50, 17, 41, 25, 55, 73, and 6 showed the lowest carotenoid levels. Additionally, in irrigated conditions, genotypes 62, 110, 61, 78, 27, 86, 88, 71, 97, and 85 had the highest carotenoid levels, while genotypes 1, 103, 106, 51, 102, 98, 56, 95, 3, and 37 had the lowest carotenoid levels.

Genotypic grouping of genotypes under rainfed and irrigated conditions based on cluster analysis

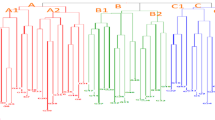

Cluster analysis using the Ward method was employed to group the studied genotypes under stress and non-stress conditions into eight clusters. In rainfed conditions (Fig. 1), the first group consisted of 21 genotypes, the second group of 9 genotypes, the third group of 8 genotypes, the fourth group of 21 genotypes, the fifth group of 26 genotypes, the sixth group of 17 genotypes, the seventh group of 9 genotypes, and the eighth group of 3 genotypes.

Based on the results, the first group exhibited the lowest values for grain yield (GY), RWC, chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll, and carotenoids. Additionally, the second group had the lowest straw weight. The third group had the highest RWC and the lowest awn length (AL) and relative water loss (RWL). The fourth group showed the lowest values for plant height (PH), peduncle length, spike length (SL), flag leaf length (FLL), 100-kernel weight (TSW), number of seeds per spike (NSPS), and straw yield (SY). The seventh group had the highest 100-kernel weight (TSW), number of seeds per spike (NSPS), straw yield (SY), grain yield (GY), chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll, and carotenoids. The eighth group exhibited the highest values for plant height (PH), peduncle length, spike length (SL), awn length (AL), flag leaf length (FLL), and RWL.

In irrigated conditions (Fig. 2), the first group comprised 23 genotypes, the second group 12 genotypes, the third group 10 genotypes, the fourth group 7 genotypes, the fifth group 11 genotypes, the sixth group 12 genotypes, the seventh group 26 genotypes, and the eighth group 13 genotypes.

According to this grouping, the first group had the lowest number of seeds per spike (NSPS), and the second group had the lowest peduncle length, awn length (AL), straw weight, grain yield (GY), RWC, chlorophyll a, and carotenoids. The third group had the highest 100-kernel weight (TSW), grain yield (GY), RWC, chlorophyll a, and the lowest RWL. The fourth group exhibited the highest awn length (AL) and number of seeds per spike (NSPS). The sixth group had the lowest plant height (PH), spike length (SL), flag leaf length (FLL), number of seeds per spike (NSPS), chlorophyll b, and total chlorophyll. The seventh group had the highest RWL, and the eighth group had the highest plant height (PH), peduncle length, spike length (SL), flag leaf length (FLL), straw yield (SY), chlorophyll b, carotenoids, and total chlorophyll.

Dendrogram resulting from cluster analysis by Ward’s method in rainfed conditions for H. spontaneum wild barley genotypes. Grain Yield (GY), Number of Seed Per Spike (NSPS), 100-Kernel weight) TSW), Plant Height (PH), Spike Length (SL), Xteragen Length (XL), Straw Yield (SY), Flag Leaf Length (FLL) and Awn Length (AL), Chlorophyll a (CHL a), Chlorophyll b (CHL b), Total Chlorophyll (CHL T) and Carotenoid (CAR).

Dendrogram resulting from cluster analysis by Ward’s method in irrigated conditions for H. spontaneum wild barley genotypes. Grain Yield (GY), Number of Seed Per Spike (NSPS), 100-Kernel weight) TSW), Plant Height (PH), Spike Length (SL), Xteragen Length (XL), Straw Yield (SY), Flag Leaf Length (FLL) and Awn Length (AL), Chlorophyll a (CHL a), Chlorophyll b (CHL b), Total Chlorophyll (CHL T) and Carotenoid (CAR).

Molecular marker analysis

Genetic diversity among the studied genotypes was assessed using a set of 50 molecular markers, comprising both SSR and EST-SSR types. Of these, 35 markers (21 SSR and 14 EST-SSR) produced clear, polymorphic, and scorable bands (Supplementary Figure S2). The total number of alleles detected per locus ranged from two to four for both marker types. SSR markers amplified a total of 57 alleles, while EST-SSR markers generated 40 alleles, reflecting substantial allelic variation. The overall polymorphism rate was high, exceeding 96% for both SSR and EST-SSR markers, indicating considerable genetic variability. Among SSR markers, loci such as BMAC0154, BMAG0508A, BMAG0323, and EBMAC0775 demonstrated the highest polymorphic information content (PIC) values. Similarly, EST-SSR markers including GBM1221, GBM1461, and SCSSR04163 exhibited superior in formativeness. Discriminatory power metrics, such as Marker Index (MI), Effective Multiplex Ratio (EMR), and Resolving Power (RP), identified EBMAC0775, BMAG0131, HVLTPPB, and SCSSR04163 as highly effective in detecting genetic diversity. Furthermore, the mean number of effective alleles and Shannon’s Information Index supported the presence of substantial allelic diversity, especially for EBMAC0775, HVLTPPB, and SCSSR04163 19.

Population structure analysis

Results showed that based on the LnP(D) and ΔK indices, K = 7 was identified as the optimal number (Fig. 3; Table 4) for characterizing population structure and calculating the Q-matrix, which estimates the membership proportions of individuals in each cluster20.

Based on the observed results in the barplot (Fig. 4), the 114 barley genotypes studied were classified into seven families. Specifically, 17 genotypes belonged to the first structure, 31 genotypes to the second structure, 12 genotypes to the third structure, 15 genotypes to the fourth structure, 11 genotypes to the fifth structure, 14 genotypes to the sixth structure, and 14 genotypes to the seventh structure. The second and fifth groups accounted for the highest (31) and lowest (11) number of individuals, respectively21.

Association analysis

Association analysis of the genome was conducted using the Mixed Linear Model (MLM), and markers associated with morphological and physiological traits under rainfed and irrigated conditions are listed in Table 5. The significance level of marker-trait associations (P-Marker) at the 0.05 level is indicated.

Results from the analysis of relationships between morphological and physiological traits and 97 amplified alleles under rainfed conditions showed that the markers EBMAG0781, BMAG0323, and SCSSR04163 are associated with grain yield (GY). Spike length (SL) is associated with markers WMC1E8, SCSSR15864, GBM1461, and SCSSR18076. Awn length (AL) is associated with markers EBMAC0521, BMAG0323, GBM1126, WMC1E8), and BMAG0131. Flag leaf length (FLL) is associated with markers SCSSR25691, EBMAC0775, HVLTPPB, BMAG0692, and EBMAG0781. Xteragen Length (XL) is associated with markers EBMAC0521, BMAG0323, GBM1110, and SCSSR05599. Number of seeds per spike (NSPS) is associated with markers BMAG0131, EBMAC0775, EBMAC0521, SCSSR15864, SCSSR25691, and GBM1126. Straw yield (SY) is associated with markers BMAC0273 and EBMAC0775. Plant height (PH) is associated with markers HVLTPPB, SCSSR04163 and EBMAC0775. (TSW) 100-Kernel weight is associated with markers SCSSR15864, SCSSR15864, BMAC0154, BMAC0154, WMC1E8, GBM1110, and EBMAC0775. Relative water loss (RWL) is associated with markers SCSSR04163, BMAG0131, and GBM1176. Relative water content (RWC) is associated with markers BMAG0323, GBM1176, and BMAG0341. Total chlorophyll (Chl T) is associated with markers GBM1461, EBMAC0415, BMAC0189, WMC1E8, BMAG0341, and BMAG0323. Chlorophyll b is associated with markers BMAG0692 and GBM1176. Chlorophyll a is associated with markers BMAG0323, GBM1126, and EBMAC0521. Carotenoid is associated with markers EBMAC0775, BMAC0273, GBM1212, and SCSSR05599.

Under irrigated conditions, results from the analysis of relationships between morphological and physiological traits and 97 amplified alleles showed that grain yield (GY) is associated with marker EBMAC0775. Spike length (SL) is associated with marker WMC1E8. Awn length (AL) is associated with markers BMAC0189 and EBMAC0415. Flag leaf length (FLL) is associated with markers BMAG0603, GBM1110, BMAC0189, and EBMAC0775. Xteragen Length (XL) is associated with markers BMAG0603, EBMAC0674, and BMAG0603. Number of seeds per spike (NSPS) is associated with marker BMAC0189. Straw yield (SY) is associated with markers BMAC0273, BMAC0273, and EBMAC0775. Plant height (PH) is associated with markers BMAG0508A, WMC1E8, BMAC0273, and HVLTPPB. (TSW) 100-Kernel weight is associated with markers EBMAG0781, GBM1110, and EBMAG0781. Relative water content (RWC) is associated with markers BMAG0323 and SCSSR25691. Relative water loss (RWL) is associated with marker SCSSR04163. Total chlorophyll (CHL T) is associated with markers BMAC0189 and SCSSR15864. Chlorophyll b is associated with markers BMAG0341, GBM1110, GBM1126, EBMAG0781, BMAC0189, SCSSR04163, and SCSSR15864. Chlorophyll a is associated with marker SCSSR25691. Carotenoid is associated with markers EBMAC0775, BMAG0692, BMAG0603, EBMAC0054, EBMAC0775, and BMAG0603.

The results demonstrate that marker WMC1E8 is significantly associated with spike length (SL), marker EBMAC0775 with flag leaf length (FLL), markers BMAC0273 and EBMAC0775 with straw yield (SY), marker HVLTPPB with plant height (PH), marker GBM1110 with 100-kernel weight (TSW), marker SCSSR04163 with relative water loss (RWL), marker BMAG0323 with relative water content (RWC), marker BMAC0189 with total chlorophyll content, and marker EBMAC0775 with carotenoid content. Notably, these associations were consistent across both rainfed and irrigated conditions.

- Grain Yield (GY), Number of Seed Per Spike (NSPS), 100-Kernel weight) TSW), Plant Height (PH), Spike Length (SL), Xteragen Length (XL), Straw Yield (SY), Flag Leaf Length (FLL) and Awn Length (AL), Chlorophyll a (CHL a), Chlorophyll b (CHL b), Total Chlorophyll (CHL T) and Carotenoid (CAR).

The chromosomal positions of the SSR and EST-SSR markers analyzed in this study are illustrated in Fig. 5, with the corresponding agronomic and physiological traits indicated adjacent to each marker. Across both rainfed and irrigated environments, significant marker–trait associations were detected and distributed across all seven barley chromosomes (1–7 H). Under rainfed conditions, chromosome 2 H harbored WMC1E8, which was associated with spike length (SL), and BMAG0323, linked to relative water content (RWC). Chromosome 4 H contained EBMAC0273, associated with flag leaf length (FLL), while chromosome 5 H included BMAC0275 and EBMAC0775, both linked to straw yield (SY). Under irrigated conditions, chromosome 1 H carried GBM1110, associated with thousand-seed weight (TSW), whereas chromosome 3 H hosted BMAC0189, and chromosome 6 H contained EBMAC0415, both consistently linked to grain yield (GY). Notably, BMAG0323 (2 H) and BMAG0223 (7 H) were associated with RWC under both moisture regimes, indicating positional stability. Among all chromosomes, 2 H and 5 H showed the highest frequency of significant associations, suggesting their central role in controlling both yield components and physiological traits under contrasting water availabilities.

The chromosomal locations of the markers utilized and their associations with the evaluated traits under both rainfed and irrigated conditions are illustrated. This figure was generated using the ggplot2 package within the R programming environment, with marker position information obtained from the GrainGenes database (https://wheat.pw.usda.gov/GG3/).

Discussion

The presence of various biological and non-biological stresses in cultivated areas in Iran underscores the importance of conservation and utilization programs for genetic diversity. Genetic diversity is essential for successful breeding, as the selection of superior genotypes within breeding populations depends on its presence22. This diversity has been developed over thousands of years and has remained stable, giving it superiority over artificial diversity. Based on significant differences in the mentioned traits, it can be concluded that the genotypes under study possess sufficient genetic diversity. This diversity enables the selection of superior genotypes based on these traits under drought stress conditions23.

Genotype differences under favorable moisture conditions indicate the production potential in different genotypes, which can yield different performances depending on genotype capacity if suitable conditions are provided. Analyses of genetic diversity in wild barley defense genes have indicated greater variation in biotic stress-related genes compared to abiotic stress-related genes24. This diversity is valuable for barley improvement, as it provides a rich source of genetic variations for breeding programs25. A study conducted to evaluate agro-morphological and physiological traits in wild barley (H. spontaneum) germplasm revealed a wide range of phenotypic expression for various traits, including days to spike emergence, plant height, spike length, spikelet triplet groups, 100-grain weight, total root length, and root dry weight26.

According to the results of the analysis of variance, the studied traits are significantly influenced by moisture conditions, as both spatial and genotypic effects, as well as their interaction, have shown significant differences. Therefore, these traits can serve as criteria for selecting wild barley genotypes under rainfed conditions. Additionally, most of these traits have shown significant differences among genotypes under both rainfed and irrigated conditions. The composite variance analysis showed a significant effect of rainfed and irrigated conditions on the measured traits, and genotype responses in these two experimental environments were significantly different. These results indicate extensive diversity among wild barley genotypes in different moisture conditions, which can be utilized for selecting genotypes tolerant to drought stress and with higher yields. As observed, the range of variations in all traits had a relatively high spectrum, indicating high diversity in terms of the studied traits among the studied genotypes. Given the high coefficients of variation for the studied traits and their importance in selecting superior genotypes, these traits can be considered valuable breeding resources. The evaluation of morphological diversity in wild barley (H. spontaneum) germplasm revealed significant variation in quantitative characters, including plant height, spike length, root length, grain width, number of grains per spike, grain length, number of leaves, and days for flowering27.

The results showed significant differences in the performance of the best genotypes under rainfed and irrigated conditions. However, what was significant was the different grouping of genotypes for different traits under stress and non-stress conditions, indicating a different trend in genotype responses to different moisture conditions. The selection and separation of genotypes tolerant to stress are performed directly (performance measurement) and indirectly (based on morphological and physiological traits correlated with stress tolerance). Drought tolerance in a plant genotype is owed to a number of its physiological and morphological characteristics, and efforts are ongoing to identify effective criteria for selecting resistant genotypes. Hamza et al. 28 in examining the diversity among 26 winter barley genotypes in Tunisia, used 12 agronomic traits and conducted cluster analysis on traits and samples. Cluster analysis showed genetic similarity of H. spontaneum barley samples with their geographic success to some extent. In the study of Shakhaterh et al. 29 cluster analysis of wild barley samples also corresponded to their ecological and geographic patterns.

Relative leaf water content (RWC) has been introduced as an index to demonstrate damage caused by drought stress. Higher relative leaf water content increases photosynthesis and consequently enhances performance under stress conditions. Water deficiency reduces relative leaf water content and leaf water potential, leading to cellular dehydration, stomatal conductance, and photosynthesis reduction, thereby affecting growth and crop production. Therefore, this trait can be considered one of the best indicators of plant water status in selecting varieties under stress conditions30. The results of the present study showed that the loss of plant water content under rainfed conditions is greater than under irrigated conditions, but the minimum amount of lost water under rainfed and irrigated conditions differs slightly, indicating resistance to water scarcity in genotypes. It can be said that the results obtained from the study of water loss depend on environmental conditions and genetic materials under study, and accordingly, the results of different studies have been different. Therefore, the maintenance and availability of water in these genotypes under moisture stress conditions are highly significant and directly affect performance.

Considering the obtained results, it is evident that drought stress causes a reduction in greenness in all genotypes, but the reduction in sensitive cultivars was greater than in tolerant varieties. Wild barley accessions have shown improved RWC percentages and reduced relative water loss (RWL) under drought conditions compared to cultivated barley, indicating their superior drought tolerance mechanisms31. Additionally, the application of biochar has been found to enhance RWC by up to 33% and reduce RWL by 54% in stressed barley plants, highlighting the potential of soil amendments in improving water retention and stress tolerance in crops32. These findings underscore the importance of monitoring RWC and RWL as indicators of drought stress responses and the potential for utilizing wild barley genetic resources to enhance drought tolerance in cultivated barley.

Chlorophyll maintenance is crucial under drought stress conditions in cereals, and drought-tolerant genotypes show less chlorophyll reduction compared to drought-sensitive genotypes. Moreover, under drought conditions, a decrease in chlorophyll and carotenoids content has been observed, suggesting an adaptive response to minimize the formation of reactive oxygen species in photosynthetic membranes33.

Association analysis of wild barley has been a topic of interest in recent literature. Wild barley has been identified as a valuable source of genetic variation for abiotic stress tolerance in crop improvement. Studies have shown that wild barley collections from various regions, particularly the Mediterranean, harbor genetic diversity that could be beneficial for developing stress-tolerant cultivars. Research has highlighted the importance of exploring the differences between wild barley and cultivated varieties to harness untapped genetic reserves34. Furthermore, genetic strategies involving wild barley germplasm have been successful in identifying positive alleles for stress tolerance traits, such as drought tolerance, in barley35. The use of wild barley in breeding programs has shown promise in introducing new disease-resistance genes and enhancing stress tolerance in cultivated barley34.

Results have shown that based on LnP(D) and ΔK indices, the number 7 was identified as the best K. Based on the observed results, 114 barley genotypes studied were divided into seven families. Ferreira et al. 36 examined the genetic diversity of Brazilian barley (6 wild barley samples, 35 cultivars, and 16 breeding lines) using UPGMA clustering on traits and found that genotype grouping classified them into three groups. They also classified genotypes using Structure software and identified two subpopulations using the Evanno method. The first subgroup included wild barley and breeding lines, and the second subgroup included Brazilian barley with very low diversity.

Results of the correlation between morphological and physiological traits and 97 duplicated alleles under irrigated conditions showed that BMAC0189, BMAG0603, and EBMAC0775 had the highest correlation with five traits. Similarly, under rainfed conditions, BMAG0323, EBMAC0775, and GBM1126 markers had significant correlations with six traits. Common markers for some traits are likely due to chromosomal linkage controlling these traits or pleiotropy.

Wojcik-Jagla et al. 37 studied the mapping of trait associations related to drought tolerance in 109 spring barley genotypes and examined the associations between sequence-tagged sites (DArTseq) and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with various physiological indices related to plant responses to drought stress. It was concluded that mapping associations could increase the density of existing QTL maps without reconstructing mapping populations. The examination of traits such as plant height (PH), yield, flowering time, grain weight, and grain protein content in a population composed of 770 barley lines showed that 91 QTLs controlled these traits38. Abou-Elwafa39 used association mapping to examine correlations between 76 SSR markers and six drought-related traits in a set of 107 barley evaluated under drought and irrigated conditions. Significant differences were measured between irrigated suitable and drought stress conditions for all traits, with a high level of polymorphism observed with SSR markers. A significantly positive correlation was found between several molecular markers and more than one phenotypic trait, indicating the possibility of polytropic effects or indirect effects. Association mapping using SSR markers in barley identified 51 chromosomal regions associated with performance traits, plant height (PH), and yield stability40.

The chromosomal distribution pattern of marker–trait associations highlights specific genomic regions with potential importance for barley adaptation to different water regimes. Chromosome 5 H, with multiple loci (BMAC0275 and EBMAC0775) affecting biomass related traits, appears to be a hotspot for QTLs controlling vegetative growth and yield potential, particularly under rainfed conditions. Chromosome 2 H demonstrated dual functionality, carrying loci such as WMC1E8 and BMAG0323 that influence both agro-morphological (Spike Length) and physiological (RWC) traits, which may be linked to drought adaptive processes like improved water use efficiency and spike architecture optimization. The stability of associations for RWC related markers on 2 H and 7 H across environments indicates the presence of conserved drought responsive genes, possibly involved in osmotic adjustment or cell membrane stability. In contrast, loci like GBM1110 on 1 H and BMAC0189 on 3 H exhibited environment specific effects, being significant only under irrigated conditions, which suggests their role in optimizing performance under favorable growth circumstances. The identification of these chromosomal regions provides a targeted genetic framework for integrating stable and environment specific QTLs into breeding programs, enabling the development of barley genotypes with improved performance in both high input and water limited systems.

Conclusion

This study highlights the significant genetic diversity within wild barley (H. spontaneum) populations in western Iran and underscores the potential of these genotypes for improving cultivated barley varieties. Through comprehensive analysis of agro-morphological and physiological traits using SSR and EST-SSR molecular markers, several key findings and applications have emerged. Firstly, the identification of significant marker-trait associations provides valuable insights for breeding programs aimed at enhancing barley’s resilience to abiotic stresses such as drought and salinity. Markers such as EBMAG0781, BMAG0323, and SCSSR04163, which showed strong associations with various traits, are particularly noteworthy for their potential use in marker-assisted selection (MAS) strategies. The genetic diversity observed in traits such as grain yield, plant height, and relative water content across different environmental conditions further emphasizes the adaptability and robustness of these wild barley genotypes. Additionally, the population structure analysis revealed the existence of seven subpopulations, indicating a rich genetic stratification that can be exploited for breeding purposes. The presence of significant genotype by environment interactions for most traits suggests that future breeding efforts should consider environmental specificity to maximize the expression of desirable traits. In conclusion, the genetic resources found in wild barley populations present a valuable opportunity for the development of high yielding, stress tolerant barley varieties. By leveraging the genetic diversity and marker-trait associations identified in this study, future breeding programs can significantly contribute to global food security and agricultural sustainability.

Materials and methods

Plant samples

This study was conducted on 114 genotypes of wild barley (H. spontaneum) collected from the western provinces of Iran, including 29 genotypes from Kermanshah, 28 genotypes from Kurdistan, 28 genotypes from Ilam, and 29 genotypes from Lorestan (Dr Ali Ashraf Mehrabi undertook the formal identification, the Ilam University gene bank code (IUGB), genotype numbers, locations/regions, and geographic coordinates can be found in the Supplementary Table S1) Voucher specimens of all 114 genotypes of H. spontaneum were deposited in the Ilam University Gene Bank (IUGB), which is a public collection providing access to deposited material. The experiment was carried out during the agricultural years 2020–2021 and 2021–2022 at the research farm of the Agricultural and Natural Resources Research Center of Kermanshah Province, located in the Mahidasht region.

Experimental design and agricultural operations

This research was conducted in an augmented design (augmented RCBD) with five blocks and nine control genotypes {Genotypes 1 (Kermanshah-Mahidasht), 24 (Kermanshah-Sarpol Zahab), 35 (Kermanshah-Harsin), 10 (Ilam-Ilam), 51 (Ilam-Mehran), 74 (Kurdistan-Kamyaran), 34 (Kurdistan-Bijar), 104 (Lorestan-Kuhdasht), and 113 (Lorestan-Aligudarz)}. Each plot consisted of two three-meter rows with a row spacing of 50 cm. Sampling for measuring morphological and physiological traits was done considering the climatic conditions of the area, after pollination and ensuring the application of drought stress on the genotypes under study. In both drought-stressed and non-stressed conditions, the first rainfall was considered the planting date, and in drought stressed conditions, no irrigation was provided throughout the growth period. Drought stress intensity (SI) was calculated according to Fischer and Maurer42 as SI = 1−( YS/YP), where YS and YP are the mean yields under stress and non-stress conditions, respectively; the resulting value indicated a 33% yield reduction, corresponding to a moderate drought stress level. For recording observations, 20 plants were randomly selected from each genotype in each replication, considering the edge effect.

Location specifications

The field experiment was carried out at the Mahidasht Research Station, situated 20 km along the Kermanshah–Islamabad-e-Gharb road, at an altitude of 1,380 m above sea level (34°16′ N, 46°50′ E). According to the USDA Soil Taxonomy, the soil at the experimental site is classified as Fine, Mixed, Thermic, Vertic Calcixerepts, with a silty clay texture, indicating a heavy to very heavy soil class. Irrigation water quality corresponds to the C3–S1 class, and the long-term (10-year) mean annual precipitation is approximately 335 mm. Detailed physico-chemical properties of the soil, including texture, field capacity, and water-holding capacity, are provided in Supplementary Table S2. Climatic data for the 2020–2021 and 2021–2022 growing seasons were obtained from the Mahidasht Meteorological Station. The region is characterized by a semi-arid to sub-humid climate, and environmental variables were continuously monitored during the study period. Monthly patterns of temperature and precipitation, illustrating seasonal climatic fluctuations, are shown in Supplementary Figure S1. Prior to sowing, no basal fertilizer was applied. During the growing season, each plot received 50 g of urea fertilizer, and weeds were removed manually to avoid competition with the crop.

Traits studied in the field

The evaluated agronomic traits included grain yield (GY), number of seeds per spike (NSPS), 100-kernel weight (TSW), plant height (PH), spike length (SL), exteragen length (XL), straw yield (SY), flag leaf length (FLL), and awn length (AL).

Relative water content (RWC)

0.5 gr of the youngest fully developed leaf from each plant (FW) was separated, and then the samples were floated in distilled water for 4 h. After this period, the leaf pieces were gently dried with paper towels and immediately weighed to obtain the turgid weight (TW). The leaf pieces were then dried in an oven at 70 degrees Celsius for 48 h to obtain the dry weight (DW). RWC was calculated using the following formula:

Relative water loss (RWL)

For this trait, 5 flag leaves were randomly selected from each genotype in each replication during the flowering stage and immediately weighed. The weighed samples were placed at 35 degrees Celsius for 4 h to obtain the wilting weight. Finally, to obtain the dry weight, the samples were placed in an oven at 72 degrees Celsius for 24 h and then weighed. The water loss was calculated using the following formula:

Determination of chlorophyll a, b, total chlorophyll, and carotenoid concentrations

0.25 gr of dry leaf powder was weighed with a digital scale with an accuracy of 0.0001 gr and placed in capped tubes. Five milliliters of 99.5% methanol were added. The samples were kept in the dark for 2 h, then shaken to homogenize the solution and centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 rpm. The absorbance of the supernatant was read at 650, 665, and 470 nm using a spectrophotometer, and the concentrations were calculated using the following formulas43:

Statistical analysis of morphological and physiological studies

Variance analysis with five replications and nine control genotypes for two years in two environments (rainfed and irrigated) was performed using SPSS.22 software for agro-morphological and physiological traits, and mean comparisons were made using the LSD method at the 5% and 1% levels. Cluster analysis using the Ward method was also performed for the traits using ClustVis software44.

Genotypic evaluation

DNA extraction was performed using the modified CTAB method45 for each population. The quality and quantity of the extracted DNA were assessed using 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis and a spectrophotometer. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) was carried out in a 20 µl volume (50 ng template DNA, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.05 mM of each dNTP, 0.2 µmol primers, one unit Taq DNA Polymerase enzyme, and 1x reaction buffer). The thermal cycle included an initial denaturation at 95 degrees Celsius for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 30 s at 95 degrees Celsius, 30 s at a primer-specific annealing temperature (52 to 60 degrees Celsius), and 60 s at 72 degrees Celsius. A final extension was done for 5 min at 72 degrees Celsius. A 4% agarose gel with 1X TBE reaction buffer was used in this experiment. The Quantum ST4 Gel Document device was used to visualize the DNA bands.

Population structure and association analysis

The genetic structure of the evaluated barley genotypes was characterized using a Bayesian model-based clustering strategy implemented in STRUCTURE software version 2.3.4 46. Thirty-five polymorphic SSR primers (primer sequences provided in Supplementary Table S3) were employed, with chromosomal positions obtained from the GrainGenes database (https://wheat.pw.usda.gov/GG3/) based on established barley linkage maps41,47. The number of possible genetic clusters (K) was explored within a range of 1 to 10. Each K value was analyzed in five independent runs under an admixture model with independent allele frequencies. A burn-in phase of 10,000 iterations was followed by 100,000 Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) replications to ensure likelihood convergence. The Q-matrix generated by STRUCTURE quantified the proportion of each genotype’s genome assigned to each inferred cluster. A genotype was classified into a specific subpopulation if its membership coefficient (Q value) was ≥ 0.70; otherwise, it was considered admixed48. The most likely number of subpopulations was determined by examining the posterior probability [LnP(D)] across K values, as well as applying the ΔK method of Evanno et al. 49, which identifies the optimal K through the second-order rate of change in LnP(D).

Marker–trait association (MTA) was evaluated using a Mixed Linear Model (MLM) in TASSEL version 3.0. Quality control procedures included removal of genotypes with excessive missing data, exclusion of alleles showing poor amplification, and elimination of markers with a minor allele frequency (MAF) below 5%. Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) testing and linkage disequilibrium (LD) analysis were also conducted in TASSEL. To correct for population structure and relatedness, both the Q-matrix from STRUCTURE and the kinship matrix (K-matrix) from TASSEL were included in the MLM (Q + K) framework. This approach reduced the risk of spurious associations while improving detection power.

Marker positions were expressed in centimorgans (cM) and visualized as chromosome maps generated using the ggplot2 package in R, allowing precise graphical representation of marker distribution for interpretation of MTA results.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Nevo, E. & Chen, G. Drought and salt tolerances in wild relatives for wheat and barley improvement. Plant. Cell. Environ. 33, 670–685 (2010).

Lakew, B. The genetic potential of wild barley (Hordeum Spontaneum C. Koch) to improve adaptation to low rainfall environments (Southern Cross University., 2009).

Yakovleva, O. Genetic diversity of wild barley (Hordeum spontaneum K. Koch) in the context of resistance to toxic aluminum ions. Труды по прикладной ботанике генетике и селекции. 184, 215–224 (2023).

Guo, Y., Himmelbach, A., Weiss, E., Stein, N. & Mascher, M. Six-rowed wild‐growing barleys are hybrids of diverse origins. Plant J. 111, 849–858 (2022).

Tesfaye, S. & Sime, B. Review on genetic erosion of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) in the highlands of Ethiopia. EAS J. Biotechnol. Genet. 4, 24–30 (2022).

Zhang, W. et al. Genome architecture and diverged selection shaping pattern of genomic differentiation in wild barley. Plant Biotechnol. J. 21, 46–62 (2023).

Capasso, G., Santini, G., Petraretti, M., Esposito, S. & Landi, S. Wild and traditional barley genomic resources as a tool for abiotic stress tolerance and biotic relations. Agriculture 11, 1102 (2021).

Iqbal, A. et al. Study of genetic divergence among wheat genotypes through random amplified polymorphic DNA. Genet. Mol. Res. 6, 476–481 (2007).

Gaweł, M., Wiśniewska, I. & Rafalski, A. Semi-specific PCR for the evaluation of diversity among cultivars of wheat and triticale. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 7, 577–582 (2002).

Williams, N. R. PCR-based Polymorphisms in Bermudagrass (Cynodon spp) (University of Florida, 2003).

Semagn, K., Bjørnstad, Å. & Xu, Y. The genetic dissection of quantitative traits in crops. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 13, 16–17 (2010).

Gebhardt, C., Ballvora, A., Walkemeier, B., Oberhagemann, P. & Schüler, K. Assessing genetic potential in germplasm collections of crop plants by marker-trait association: a case study for potatoes with quantitative variation of resistance to late blight and maturity type. Mol. Breeding. 13, 93–102 (2004).

Gupta, P. K., Rustgi, S. & Kulwal, P. L. Linkage disequilibrium and association studies in higher plants: present status and future prospects. Plant Mol. Biol. 57, 461–485 (2005).

Holland, J. B. Genetic architecture of complex traits in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant. Biol. 10, 156–161 (2007).

Doerge, R. W. Mapping and analysis of quantitative trait loci in experimental populations. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3, 43–52 (2002).

Breseghello, F. & Sorrells, M. E. Association mapping of kernel size and milling quality in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cultivars. Genetics 172, 1165–1177 (2006).

Myles, S. et al. Association mapping: critical considerations shift from genotyping to experimental design. Plant. Cell. 21, 2194–2202 (2009).

Ersoz, E. S., Yu, J. & Buckler, E. S. In Genomics-Assisted Crop Improvement: Vol. 1: Genomics Approaches and Platforms97–119 (Springer, 2007).

Shirvani, H. et al. Phenotyping variability and detecting informative SSR and EST-SSR markers for malt and straw quality characteristics in a diverse panel of wild barley (H. spontaneum) under rainfed and irrigated conditions. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 72, 1881–1902 (2025).

Shirvani, H. et al. Phenotyping variability and detecting informative SSR and EST-SSR markers for malt and straw quality characteristics in a diverse panel of wild barley (H. spontaneum) under rainfed and irrigated conditions. Genetic Resour. Crop Evolution, 1–22 (2024).

Shirvani, H. et al. Marker-trait association analysis for root and shoot traits at the seedling stage of wild barley (Hordeum vulgare subsp. spontaneum) under water stress and normal conditions. AoB Plants. 17, plaf022 (2025).

Yirgu, M. et al. Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers for genetic diversity and population structure study in Ethiopian barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) germplasm. BMC Genomic Data. 24, 7 (2023).

Al-Abdallat, A. et al. Assessment of genetic diversity and yield performance in Jordanian barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) landraces grown under rainfed conditions. BMC Plant Biol. 17, 191 (2017).

Fitzgerald, T. L. et al. Genome diversity in wild grasses under environmental stress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108, 21140–21145 (2011).

Liu, M. et al. The draft genome of a wild barley genotype reveals its enrichment in genes related to biotic and abiotic stresses compared to cultivated barley. Plant Biotechnol. J. 18, 443–456 (2020).

Kaur, V., Sharma, K. & Jacob, S. R. Assessment of genetic diversity in cultivated and wild species germplasm of barley based on morpho-agronomical and root architecture traits. Indian J. Plant. Genetic Resour. 32, 360–367 (2019).

Al-Saghir, M., Malkawi, H. & El-Oqlah, A. Morphological diversity in hordeum spontaneum C. Koch of Northern Jordan (Ajloun Area). Middle-East J. Sci. Res. 4, 24–27 (2009).

Hamza, S., Ben Hamida, W., Rebaï, A. & Harrabi, M. SSR-based genetic diversity assessment among Tunisian winter barley and relationship with morphological traits. Euphytica 135, 107–118 (2004).

Shakhatreh, Y., Haddad, N., Alrababah, M., Grando, S. & Ceccarelli, S. Phenotypic diversity in wild barley (Hordeum vulgare L. ssp. Spontaneum (C. Koch) Thell.) accessions collected in Jordan. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 57, 131–146 (2010).

Fang, S., Yang, H., Duan, L., Shi, J. & Guo, L. Potassium fertilizer improves drought stress alleviation potential in Sesame by enhancing photosynthesis and hormonal regulation. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 200, 107744 (2023).

Abdelaal, K. et al. The pivotal role of Biochar in enhancement soil properties, morphophysiological and yield characters of barley plants under drought stress. Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca. 50, 12710–12710 (2022).

Shrestha, A. et al. Natural diversity uncovers HvP5cs1 regulation and its role in drought stress adaptation and yield sustainability in barley. Authorea Preprints (2022).

Tatsiana, G. & Nikolay, V. The effect of soil drought on the content of photosynthetic pigments in barley plants of the brovar variety. Exp. Biol. Biotechnol. 3, 46–53 (2020).

Ellis, R. P. et al. Wild barley: a source of genes for crop improvement in the 21st century? J. Exp. Bot. 51, 9–17 (2000).

Forster, B. et al. Genotype and phenotype associations with drought tolerance in barley tested in North Africa. Ann. Appl. Biol. 144, 157–168 (2004).

Ferreira, J. R. et al. Assessment of genetic diversity in Brazilian barley using SSR markers. Genet. Mol. Biology. 39, 86–96 (2016).

Wójcik-Jagła, M., Fiust, A., Kościelniak, J. & Rapacz, M. Association mapping of drought tolerance-related traits in barley to complement a traditional biparental QTL mapping study. Theor. Appl. Genet. 131, 167–181 (2018).

Pauli, D. et al. Association mapping of agronomic QTLs in US spring barley breeding germplasm. Plant. Genome. 7 plantgenome2013.2011.0037 (2014).

Abou-Elwafa, S. F. Association mapping for yield and yield-contributing traits in barley under drought conditions with genome-based SSR markers. Comptes Rendus Biologies. 339, 153–162 (2016).

Inostroza, L. et al. Association mapping of plant height, yield, and yield stability in Recombinant chromosome substitution lines (RCSLs) using hordeum Vulgare subsp. Spontaneum as a source of donor alleles in a hordeum Vulgare subsp. Vulgare background. Mol. Breeding. 23, 365–376 (2009).

Ramsay, L. et al. Variation shown by molecular markers in barley: genomic and genetic constraints. (2004).

Fischer, R. & Maurer, R. Drought resistance in spring wheat cultivars. I. Grain yield responses. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 29, 897–912 (1978).

Lichtenthaler, H. K. & Wellburn, A. R. (Portland Press Ltd., (1983).

Metsalu, T. & Vilo, J. ClustVis: a web tool for visualizing clustering of multivariate data using principal component analysis and heatmap. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, W566–W570 (2015).

Torres, A., Weeden, N. & Martin, A. Linkage among isozyme, RFLP and RAPD markers in vicia Faba. Theor. Appl. Genet. 85, 937–945 (1993).

Pritchard, J. K., Stephens, M., Rosenberg, N. A. & Donnelly, P. Association mapping in structured populations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 67, 170–181 (2000).

Ramsay, L. et al. A simple sequence repeat-based linkage map of barley. Genetics 156, 1997–2005 (2000).

Spataro, G. et al. Genetic diversity and structure of a worldwide collection of phaseolus coccineus L. Theor. Appl. Genet. 122, 1281–1291 (2011).

Evanno, G., Regnaut, S. & Goudet, J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 14, 2611–2620 (2005).

Acknowledgements

We thank Faculty of Agriculture, Ilam University for the technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, Investigation, Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Validation, Software, Writing – original draft [Hooman Shirvani], Investigation, Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Validation, Software, Writing – original draft [Ali Ashraf Mehrabi], Supervision, Funding administration, Writing – review & editing [Mohsen Farshadfar], Supervision, Writing – review & editing [Hooshmand Safari], Supervision, Writing – review & editing [Ali Arminian] and Supervision, Writing – review & editing [Foad Fatehi].

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study focused exclusively on plant research and did not involve any human or animal subjects. As a result, it did not require approval from an ethics committee. The research adhered to all applicable guidelines and regulations for plant studies to ensure ethical and responsible conduct of the research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shirvani, H., Mehrabi, A.A., Farshadfar, M. et al. Genetic structure and marker-trait association analysis for agro-morphological and physiological characteristics in germplasm of wild barley (Hordeum vulgare subsp. spontaneum). Sci Rep 15, 38706 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22401-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22401-8