Abstract

This retrospective study investigated the impact of preoperative comorbidities on postoperative complications and survival in 408 head and neck cancer (HNC) patients undergoing complete tumor resection for curative intent. The mean age was 62.5 ± 13.2 years; 58.6% were male, 32.4% had pT3-4 tumors, and 27.5% had pN1-3 disease. Comorbidities were present in 70.6%, primarily hypertension (36.8%), cardiac disease (24.5%), endocrine/metabolic diseases (21.6%), pulmonary diseases (13.2%), and cerebrovascular diseases (CVDs, 10.8%). The overall postoperative medical/surgical complications rate was 24.7% (medical: 8.1%, surgical: 18.4%). Patients with comorbidities had higher complication rates (28.1% overall, 9.4% medical, 20.5% surgical). CVDs (20.5% vs. 6.6%), cardiac disease (14.0% vs. 6.2%), and endocrine/metabolic diseases (13.6% vs. 6.6%) significantly increased medical complication risks. Multivariable analysis identified tumor located in oral cavity, ASA grade III–IV, prolonged operation (> 3 h), flap reconstruction, and tracheotomy as independent risk factors for complications. Survival analysis showed reduced overall survival in patients with higher ASA grades, cervical lymph node metastasis, or history of preoperative adjuvant therapy (radiotherapy, chemotherapy, concurrent chemoradiotherapy). The findings highlight that preoperative CVDs, cardiac disease, or endocrine/metabolic disorders elevate medical complication risks by 2–3 times, underscoring the need for thorough preoperative assessment to improve outcomes in HNC surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The incidence of head and neck cancer (HNC) has increased in the past decade, with surgical resection being the mainstream treatment1,2. Patients with comorbidities are inclined to present a higher rate of HNC. Preoperative comorbidity is defined as a distinct medical diagnosis that HNC patients have alongside the primary diagnosis of head and neck cancer. It refers to a pre-existing condition identified through preoperative medical history or specialist diagnosis. The ability to tolerate oncologic surgery is a primary concern for these patients and their families3,4. Comorbidities attract more attention because they directly impact patient care, surgical treatment plans, anesthesia risk assessment, and the evaluation of treatment effectiveness. Patients with HNC often present with several risk factors for preoperative comorbidities, such as coronary artery disease (CAD) and pulmonary disease. They are typically older men, with a high rate of smoking and a high prevalence of arteriosclerosis5. Patients with pre-existing cardiac or pulmonary morbidity usually require careful attention due to anesthetic risk and potential medical complications. Large volume fluid shifts from significant intraoperative blood loss and intravenous volume replacement can cause hemodynamic instability, resulting in cardiac ischemia. Additionally, patients undergoing HNC ablation often have difficulty in communicating with others due to the overlap of the surgical site and anesthesia intubation during the perioperative period, making it challenging to detect and diagnose symptoms of perioperative medical complications6. Therefore, despite precise preoperative evaluations, strict intraoperative monitoring of vital signs, and proper postoperative care, patients may still experience episodes of perioperative medical complications. Severe comorbid or coexisting conditions may pose an equal or even greater threat to survival than cancer3,7. Perioperative acute myocardial infarction (AMI)-related hemodynamic instability presents a significant challenge to surgeons. Based on the guidelines provided by European society of cardiology, patients undergoing head and neck surgery would have an intermediate (1–5%) risk for CAD, AMI, and stroke within 30 days after surgery8. Haapio et al9.found that the 30-day incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular complications was 7.2%. Other authors have reported a higher risk of cardiac complications for patients undergoing major HNC surgery (12–25%)10,11.

While preoperative comorbidities are known to increase perioperative complication risks, it is unclear which ones cause the most severe postoperative complications or demand special attention. This study clarified the main comorbidities that cause postoperative complications and their incidence rates by comparing the postoperative complication rates of HNC patients with and without preoperative comorbidities, and further evaluated the impact of preoperative comorbidities on patient prognosis.

Materials and methods

Study design and patients

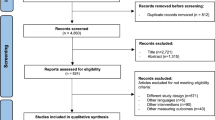

This was a retrospective case-series study. Patients with HNC who underwent general anesthesia for tumor resection between January 2012 and December 2021 at the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH), were enrolled in this retrospective study. Inclusion criteria were: (1) pathologically confirmed head and neck cancer patients who underwent curative-intent complete tumor resection; and (2) availability of complete medical records. Exclusion criteria were: (1) patients who underwent only biopsy without definitive resection; or (2) those with non-malignant tumors. The study was conducted according to the ethical guidelines of the Ministry of Health of China. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board(IRB) and the Office of Responsible Research Practices at PUMCH (NO. I-24PJ1762). Our study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and IRB guidelines. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, IRB and the Office of Responsible Research Practices at PUMCH waived the need of obtaining informed consent.

Data collection

Demographic, clinical characteristics of patients were collected from our institution’s clinical medical history database management system(inpatient and outpatient), including age at surgery, gender, history of smoking and alcohol use, preoperative comorbidities, diagnosis, tumor subsite, T stage (tumor size and extent, AJCC 8th edition), N stage (lymph node involvement, AJCC 8th edition), history of preoperative adjuvant therapy (including radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and concurrent chemoradiotherapy), the surgical method (flap reconstruction), American society of anesthesiologists (ASA) classification, operative duration, tracheotomy, intra-operative blood transfusion, post-operative and total length of hospital stay, postoperative medical/surgical complications (including complications occurred within 30 days of discharge from the hospital).

Two independent reviewers, who were not involved with the attending surgeon, performed the data collection. The charts were thoroughly reviewed by these same independent reviewers for any complications documented in the notes, including daily progress notes, consulting service notes, radiography reports, and discharge summaries.

Definition and assessment of preoperative comorbidities

Preoperative comorbidities included hypertension, cardiac diseases (including CAD and arrhythmia), endocrine and metabolic diseases (including diabetes mellitus), pulmonary disease, cerebrovascular disease (CVDs, such as cerebrovascular accident[CVA]), liver diseases, kidney diseases, digestive tract diseases, viral hepatitis, autoimmune diseases, hematological system diseases, venous thromboembolic diseases (including deep vein thrombosis [DVT] and pulmonary embolism [PE]), mental diseases, and multiple primary cancer (including HNC and non-HNC). Preoperative comorbidities were categorized based on the presence or absence of coexisting medical conditions. Any preoperative condition unrelated to the head and neck cancer of this inpatient surgery was classified as a comorbidity. The severity of preoperative comorbidities was assessed using the Adult Comorbidity Evaluation 27 (ACE-27) index3 and Charlson comorbidity index (CCI)12. The ACE-27 scores 27 different medical conditions across multiple organ systems (e.g., cardiovascular, respiratory, renal, endocrine, neurological). Each condition is graded based on severity: Grade 1 (Mild), Grade 2 (Moderate), and Grade 3 (Severe). CCI is a widely used prognostic tool to predict 1-year and 10-year mortality risk based on a patient’s comorbid conditions. The CCI includes 19 medical conditions, each assigned a weight from 1 to 6 based on their association with mortality. The overall comorbidity score reflected the highest ranked single ailment for patients with multiple diseases or conditions. If two or more moderate ailments occurred in different organ systems, the overall comorbidity score was classified as severe. Multiple primary cancers are defined as more than one synchronous or metachronous cancer in the same individual.

Definition and grades of postoperative complication

Both postoperative medical and surgical complications were analyzed. Medical complications included death, shock, heart failure, myocardial infarction (MI), cardiac arrest, atrial fibrillation, severe pneumonia, acute respiratory disease, CVA, DVT/PE, delirium tremens, glaucoma, cholecystitis, intestinal infection and acute urinary retention. Surgical complications included flap necrosis, dehiscence, salivary collection/seroma, re-exploration, and infection.

Postoperative complications were categorized into five grades based on the Clavien-Dindo Classification (CDC)13: (1) Grade Ⅰ included minor events not requiring pharmacological, surgical, endoscopic, or radiological interventions, e.g. bedside-treated wound infections; (2) Grade Ⅱ involved complications necessitating pharmacological intervention, including blood transfusions; (3) Grade Ⅲ complications required surgical intervention; (4) Grade Ⅳ complications were defined as complications leading to permanent disability or organ loss; (5) Grade Ⅴ complications could lead to patient death. For analysis, CDC grades Ⅰ-Ⅱ and grades Ⅲ-Ⅴ corresponded to minor complications and major complications, respectively.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 23.0; IBM, Armonk, NY), GraphPad Prism software (version 7.0; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA), and Microsoft Excel software (2016 release; Microsoft, Redmond, WA). Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Logistic regression analysis was performed to identify risk factors for postoperative complications. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of surgery to the date of death or the last follow-up visit. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate survival outcomes, and the log-rank test was used to compare survival curves. Cases lost to follow-up were right-censored at their last confirmed visit. This censoring approach, which assumed non-informative missingness, was considered appropriate due to the low LTFU rate (< 10%). Multivariate survival analyses was performed using the Cox proportional hazards model. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients

A total of 416 patients were initially reviewed. After excluding eight due to incomplete medical records, a final cohort of 408 patients was analyzed. The study population had a mean age of 62.5 ± 13.2 years, and 239 (58.6%) were male. Demographic and clinical characteristics of preoperative comorbidity group and normal group are summarized in Table 1 and Table S1. Preoperative evaluation revealed no distant metastasis in any of the patients. The two groups were comparable in terms of age in years, gender, history of smoking and alcohol use, diagnosis, tumor subsite, pathological T stage, pathological N stage, history of preoperative adjuvant therapy, flap reconstruction, tracheotomy, blood transfusion, postoperative length of stay, total length of stay, and postoperative therapy.

Elderly patients (> 70 years), those diagnosed with oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC), and those with tumors located in oral cavity had a higher prevalence of preoperative comorbidity (p < 0.005). There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of gender, history of smoking/alcohol use, pathological T stage, pathological N stage, and preoperative adjuvant therapy. There were 45 cases of preoperative adjuvant therapy: 6 recurrent HNC tumors, 15 locally advanced tumors, 18 multiple primary carcinomas, and 6 early-stage tumors.

Patients with the history of smoking and alcohol use showed a tendency toward a higher risk of preoperative comorbidity, but these differences were not statistically significant (p = 0.077 and p = 0.086, respectively). Patients in the preoperative comorbidity group had a higher rate of major postoperative complications with CDC grades Ⅲ-Ⅴand a longer total length of stay compared to those without preoperative comorbidity (p = 0.031 and p = 0.028, respectively). There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of tracheotomy status, flap reconstruction, intraoperative blood transfusion, and postoperative length of stay.

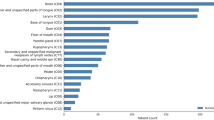

Preoperative comorbidity status of patients

The overall study cohort included 408 patients, with 288 patients (70.6%) in the preoperative comorbidity group and 120 patients (29.4%) in the normal group. The preoperative comorbidity status for the study is shown in Table 2. Duplicates were recorded for patients with two or more diseases. The most common conditions were hypertension (36.8%), cardiac disease (24.5%), endocrine and metabolic system disorders (21.6%), pulmonary disease (13.2%), and CVDs (10.8%). A history of cerebrovascular accident (CVA) was observed in 8.6% of patients at the time of surgery. Twelve patients (2.9%) had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or pneumonia. Forty-four patients (10.8%) presented with non-head and neck multiple primary cancer.

Postoperative complication status of patients

Complication outcomes are presented in Table 3. Patients with preoperative comorbidities had a higher risk of postoperative complications compared to those without comorbidity (28.1% versus 16.7%, odds ratio [OR] = 1.957, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.135–3.373, p = 0.015). Trends indicated that patients with preoperative comorbidity experienced higher rates of medical complications (9.4% versus 5.0%, p = 0.14) and/or surgical complications (20.5% versus 13.3%, p = 0.089). Cardiac events occurred more frequently in patients with preoperative comorbidity (3.5% versus 0%, p = 0.038). No significant differences were found in pulmonary complications (2.1% versus 1.7%, p > 0.95), venous thromboembolic events (3.8% versus 1.7%, p = 0.361), or neurological complications (1.4% versus 0.8%, p > 0.95). There was also no significant difference in recipient site complications (19.4% versus 11.7%, p = 0.058) or donor site complications (1.4% versus 2.5%, p = 0.431).

Univariate and multivariate analyses of predictive factors for postoperative complications.

The univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses of predictive factors for any postoperative complication, medical complications, and surgical complications are presented in Table 4. We compared three groups based on the presence or absence of these complications.

Multivariable analysis showed that a higher ASA stage (ASA Ⅲ-Ⅳ; p < 0.01), flap reconstruction (p < 0.01), and tracheotomy (p < 0.01) were significant predictors for developing any complication. In univariable analysis, CCI scores, ACE-27 scores, tumor subsite, T categoary, N categoary, ASA scores, operative duration, tracheotomy, and intraoperative blood transfusion were predictive factors for postoperative medical complications. Besides, multivariable analysis identified a higher ASA score (p < 0.01) and tracheotomy (p < 0.05) as predictors of postoperative medical complications. Neither univariable nor multivariable analyses showed that age at surgery, gender, history of smoking/alcohol use, preoperative comorbidity, or preoperative adjuvant therapy were significant predictive factors for postoperative medical complications. The significant predictors for surgical complications in multivariable analysis were gender (male; p < 0.05), longer operative duration (p < 0.05), and tracheotomy (p < 0.01).

Subgroup analysis of tumor subsite, preoperative therapy, and surgical types showed that the oral floor showed the highest complication rates (50% overall, 40.5% surgical, 19% medical), followed by buccal mucosa (40.4%, 34%, 8.5%). Parotid (3.8%), submandibular gland (3%), and oropharyngeal (0%) surgeries had the lowest rates. Patients receiving preoperative chemotherapy (43.8%) or radiotherapy (41.7%) had higher complication rates than those receiving concurrent chemoradiotherapy (29.4%). Surgical extent impacted postoperative complications: radical resection with neck dissection and flap reconstruction had the highest complication rates (51.8% overall, 40.5% surgical, 15.5% medical), while resection alone had minimal complications (1%). Neck dissection alone showed intermediate risk (9.4%) (Table S2).

Rates of postoperative medical complications for patients with preoperative comorbidities

The overall rate of postoperative medical complications among patients with preoperative comorbidities was 9.4%, as detailed in Table 5.

Fourteen patients (14.0%) with preoperative cardiac diseases experienced postoperative medical complications, which was significantly higher than the rate in those without preoperative cardiac disease (14.0% vs. 6.2%, OR = 2.476, 95% CI = 1.192–5.144, p = 0.013). Postoperative complications in these patients included (1) 9 cardiac events: 4 cases of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) involving 3 with preoperative percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and 1 with premature beats; 3 cases of atrial fibrillations involving 1 with CAD,1 with a history of PCI, and 1 with heart bypass; 1 case of heart failure associated with atrial premature beats; 1 case of cardiac arrest requiring a cardiac pacemaker; (2) 1 severe case of pneumonia involving CAD and COPD; (3) 1 cases of DVT and 1 cases of both DVT and PE; (4) 1 case of cholecystitis; (5) 1 case of septic shock associated with CAD and atrial fibrillation. Patients with CAD had a higher rate of postoperative medical complications (16.1% vs. 6.7%, OR = 2.701, 95% CI = 1.216–5.999, p = 0.012).

Eight patients (14.8%) with preoperative pulmonary diseases experienced postoperative medical complications, which was higher compared to those without preoperative pulmonary disease (14.8% vs. 7.1%, OR = 2.289, 95% CI = 0.974–5.375, p = 0.061), although this difference was not statistically significant. The complications of these patients included 4 cases of pneumonia, 2 cases of DVT with PE, 1 case of ACS, 1 case of postoperative delirium, and 1 case of hemorrhagic shock.

Nine patients (20.5%) with preoperative CVD had postoperative medical complications, which was significantly higher compared to those without preoperative CVD (20.5% vs. 6.6%, OR = 3.643, 95% CI = 1.570–8.450, p = 0.005). The complications included 4 cases of pneumonia, 2 cases of atrial fibrillations, 1 case of ACS, 1 case of hemorrhagic shock, and 1 case of delirium.

No significant differences were found in postoperative medical complications among patients with preoperative high blood pressure (HBP), venous thromboembolic disease, autoimmune diseases, liver diseases, kidney diseases, digestive tract diseases, viral hepatitis, hematological disorders, or multiple primary cancers, compared to those without these conditions (Table S3).

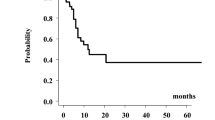

Survival outcomes

At a median follow-up of 42 months (range 1–120 months), the three-year OS rate was 80.5%. Thirty-nine patients were lost to follow-up due to the change of contact information. These cases were treated as right-censored at their last known follow-up date. Given that the lost-to-follow-up rate was < 10%, the potential bias introduced by censoring was considered minimal. Clinical significance was evaluated using the Cox proportional hazards model for OS. In univariable analysis, age, CCI ≥ 4, ASA Ⅲ-Ⅳ, pathological positive N categoary, history of preoperative adjuvant therapy, operative time longer than 3 h, any complication, surgical complication, and major complication with CDC grades Ⅲ-Ⅴ were significant factors for OS (Table 6). Multivariable analysis revealed that preoperative adjuvant therapy (hazard ratio [HR] = 2.081, 95% CI [1.128–3.839], p = 0.019), N categoasy I-Ⅲ (HR = 2.049, 95% CI [1.233–3.406], p = 0.006), and ASA Ⅲ-Ⅳ (HR = 2.245, 95% CI [1.317–3.827], p = 0.003) were independent factors associated with shortened OS (Fig. 1).

Discussion

The present study confirmed a significant association between preoperative comorbidity and an increased rate of postoperative complications in a cohort of 408 patients undergoing surgical treatment for HNC. Further analysis revealed that patients with preoperative comorbidities had a higher prevalence of major postoperative complications. Cardiac events (3.5%) were the most common postoperative medical complications among these patients. Despite the strong evidence for an increased rate of postoperative complications in comorbid patients, more detailed analysis showed that only patients with clinical dysfunction (higher ASA levels) were independently associated with postoperative complications and OS. No specific preoperative comorbidity status was found to be independently associated with postoperative complications after adjusting for confounding factors. These findings highlighted the importance of optimizing the management of medical comorbidities in the perioperative period, considering patients with preoperative comorbidities were predisposed to postoperative medical complications.

Preoperative comorbidities are relatively common among patients with HNC, with the most frequent conditions including diabetes, hypertension, cardiac diseases, pulmonary diseases, renal diseases, and endocrine abnormalities14. The rate of preoperative comorbidities have been found to be varied across studies depending on the study population and the severity of comorbidities. For instance, studies involving patients who received surgical and/or adjuvant therapy have reported a prevalence of comorbidity ranging from 45% to 58.7%14. Besides, Piccirillo14 examined the burden of comorbidity among 341 HNC patients and found that 21% had moderate to severe comorbidity, while 55% had no comorbidity. In this study, the authors defined the severity of comorbid health as mild, moderate, or severe based on Kaplan Feinstein Comorbidity Index (KFI). This comorbidity burden level was second only to that observed in patients with lung cancer (40%) and colorectal cancer (25%). Furthermore, Tzelnick15 focused on cardio-vascular comorbidity. They investigated 225 patients with oral cavity and larynx cancer and reported an overall comorbidity rate of 58.7%. Among these, the cardiovascular comorbidity rate was 46.2%, involving ischemic heart disease, chronic heart failure, CVA, hypertension, and diabetes. In addition, in Haapio’s study, the preoperative rates of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, CAD, atrial fibrillation, and prior transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke among HNC patients were 26%, 10%, 10%, 5%, and 6%, respectively9.In studies involving patients who underwent free flap reconstruction after cancer ablation, the prevalence of preoperative comorbidities were found to be ranged from 29.54% to 31%. The methods employed to assess comorbidity included ASA scores and CCI in this study16. Parsemain’s study16 reported comorbidity rates of 12.2% for COPD and 10% for DM. Mitchell’s study17 assigned patients to a high or low comorbidity group based on CCI. They reported relatively high rates of DM (18.2%), history of MI or congestive heart failure (CHF) (14.4%), COPD (5.3%), stroke or TIA (5.3%), and chronic kidney disease (3.8%). Wood found the rates of COPD, interstitial lung disease, CHF, cerebrovascular incidents, and liver diseases to be 9.7%, 0.1%, 4.2%, 6.4%, 4.4%, respectively18. In our study, the preoperative comorbidity rate was relatively high, with higher prevalence rates for HBP, CAD, CVA, and DM compared to previous reports9,16,17,18. It may be attributed to the characteristics of our comprehensive hospital.

Patients undergoing surgery for HNC are at high risk of developing postoperative medical complications, especially those with complex pre-existing conditions. In Cory’s study19, the rates of postoperative complications for patients who underwent parotidectomy were reported as follows: cardiac arrest (0.1%), MI (0.2%), stroke (0.2%), pneumonia (0.4%), sepsis or septic shock (0.3%), PE (0.1%), and DVT (0.2%). In this study, 3.6% of patients underwent free flap reconstruction. Haapio’s study9 highlighted the increased risk of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) in patients with pre-existing cardiovascular conditions. For patients who underwent HNC surgery and had a history of heart failure, CAD, prior MI, prior coronary revascularization, or hypertension, the rates of MACCE at the 30-day follow-up were 18%, 16%, 19%, 17%, and 10%, respectively. In Haapio’s study, 17.1% of patients underwent free flap reconstruction. Sou’s study20 further corroborated the heightened risk in patients with pre-existing CAD or CVA, showing higher perioperative AMI rates. The perioperative AMI rate was 3.1% for patients who underwent free flap reconstruction, with rates of 10.5%, 12.3%, 3.1%, and 2.1% in those with underlying CAD, CVA, hypertension, DM, respectively. In Marie-Therese Scaglioni’s study21, three patients died due to AMI, acute PE, and respiratory failure, resulting in a mortality rate of 5.2% among 57 HNC patients with CAD who received tumor ablation and free flap reconstruction.

In our study, the incidence of postoperative cardiac events, pulmonary complications, venous thromboembolic disease, and CVA was 2.5%, 2%, 3.2%, and 0.3%, respectively, which was lower than previously reported rates of 7–13% [5]. Patients with preoperative comorbidities had a higher overall risk of postoperative complications (28.1% vs. 16.7%). Specifically, these patients experienced higher rates of medical complications (9.4% vs. 5%) and surgical complications (20.5% vs. 13.3%), although the difference in surgical complications was not statistically significant. Cardiac incidents were more prevalent in patients with preoperative comorbidities (3.5% vs. 0), consistent with Sou’s study20. It highlights the need for vigilant cardiac monitoring and management in this patient population. Other complications, such as pulmonary, venous thromboembolic, and neurological complications, did not show significant differences between groups. This may suggest that specific comorbidities might have more pronounced effects on certain types of complications, or that the low incidence of these events could be due to cohort heterogeneity and/or the prophylactic use of perioperative antithrombotic agents in our institution. Patients with preoperative CVD (20.5% vs. 6.6%), heart disease (14% vs. 6.2%), and pulmonary disease (14.8% vs. 7.1%) had a higher rate of postoperative medical complications, including cardiac events, pneumonia, thrombosis, cholecystitis, delirium, and shock. These findings indicate that specific comorbidities, such as CVD, heart disease, and pulmonary disease, increase the risk of postoperative medical complications, necessitating targeted perioperative strategies to mitigate these risks.

It has been demonstrated that the overall severity of comorbidity is significantly associated with the survival of HNC patients14,22. Major postoperative complications are also independently associated with decreased OS23. Ankola et al. investigated 288 patients who underwent tumor resection and flap reconstruction for primary oropharyngeal, laryngeal, or oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). They found that 81% of patients had mild to severe comorbidity and reported that preoperative comorbidity was associated with poor OS, but not with cancer-specific survival or recurrence24. Similarly, Milne’s study, which included 231 patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma who underwent selective neck dissection, tumor resection, and reconstruction, found that the severity of comorbidity was significantly related to two-year mortality25. Katna’s study, which included 531 patients who had surgery for OSCC, revealed that a CCI score of 4 or more was associated with poor OS (76% vs. 66%)26. In our study, we used three different scoring/staging systems to investigate the influence of comorbidity on OS. The results indicated that a higher ASA status was independently associated with poor OS after adjusting for other significant covariates. This finding suggests that only major comorbidities with clinical dysfunction significantly impact the OS of patients. Except higher ASA status, our study also indicated that cervical lymph node metastasis and adjuvant therapy history was also independently associated with OS, this finding consistent with previous studies27,28.

The study’s strength lay in its comprehensive inclusion of all HNC patients in our departement, providing a broad risk assessment for postoperative complications in those with comorbidities. However, there were several limitations in this study. Firstly, these findings should be interpreted with caution since it was a single-center, retrospective study. Secondly, we included all cancer patients who underwent surgical treatment, resulting in a high degree of heterogeneity in the study population, which may result in unmeasured confounders. We applied subgroup analysis to address heterogeneity by dissecting complications by subsite and treatment, but larger, adjusted studies are needed for definitive risk modeling. Thirdly, the perioperative assessment, monitoring, and treatment for comorbidities and complications evolved and were modified throughout the study, which may have influenced our findings. Last, it should be noted that our study cohort predominantly consisted of patients with oral cavity cancer. Therefore, while the findings regarding preoperative comorbidities are likely applicable to the surgical management of head and neck cancer in general, caution should be exercised when extrapolating these results to populations with a very different distribution of cancer subsites. Future prospective studies are needed to better understand the impact of comorbidity on patients undergoing surgical treatment for HNC.

Conclusion

Patients with preoperative CVD, cardiac diseases, or endocrine and metabolic diseases experienced significantly higher rates of postoperative medical complications. Thorough preoperative assessment and close patient monitoring remain essential for ensuring medical safety and achieving surgical success.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of sensitivity and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J. Clin. 70, 7–30 (2020).

Pfister, D. et al. (ed, G.) Head and neck Cancers, version 2.2020, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Canc Netw. 18 873–898 (2020).

Piccirillo, J. F., Tierney, R. M., Costas, I., Grove, L. & Spitznagel, E. L. Jr. Prognostic importance of comorbidity in a hospital-based cancer registry. JAMA 291, 2441–2447 (2004).

Rose, B. S., Jeong, J. H., Nath, S. K., Lu, S. M. & Mell, L. K. Population-based study of competing mortality in head and neck cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 29, 3503–3509 (2011).

Siasos, G. et al. Smoking and atherosclerosis: mechanisms of disease and new therapeutic approaches. Curr. Med. Chem. 21, 3936–3948 (2014).

Nicoletti, G. et al. Objective assessment of speech after surgical treatment for oral cancer: experience from 196 selected cases. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 113, 114–125 (2004).

Sarfati, D., Koczwara, B. & Jackson, C. The impact of comorbidity on cancer and its treatment. CA Cancer J. Clin. 66, 337–350 (2016).

Halvorsen, S. et al. [2022 ESC guidelines on cardiovascular assessment and management of patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery developed by the task force for cardiovascular assessment and management of patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery of the European society of cardiology (ESC) endorsed by the European society of anaesthesiology and intensive care (ESAIC)]. G Ital. Cardiol. (Rome). 24, e1–e102 (2023).

Haapio, E. et al. Incidence and predictors of 30-day cardiovascular complications in patients undergoing head and neck cancer surgery. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 273, 4601–4606 (2016).

Dillon, J. K., Liu, S. Y., Patel, C. M. & Schmidt, B. L. Identifying risk factors for postoperative cardiovascular and respiratory complications after major oral cancer surgery. Head Neck. 33, 112–116 (2011).

Buitelaar, D. R., Balm, A. J., Antonini, N., van Tinteren, H. & Huitink, J. M. Cardiovascular and respiratory complications after major head and neck surgery. Head Neck. 28, 595–602 (2006).

Charlson, M. E., Pompei, P., Ales, K. L. & MacKenzie, C. R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J. Chronic Dis. 40, 373–383 (1987).

Clavien, P. A. et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann. Surg. 250, 187–196 (2009).

Piccirillo, J. F. Importance of comorbidity in head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope 110, 593–602 (2000).

Tzelnick, S. et al. Major head and neck surgeries in the elderly population, a match-control study. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 47, 1947–1952 (2021).

Parsemain, A., Philouze, P., Pradat, P., Ceruse, P. & Fuchsmann, C. Free flap head and neck reconstruction: feasibility in older patients. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 10, 577–583 (2019).

Mitchell, C. A. et al. Morbidity and survival in elderly patients undergoing free flap reconstruction: A retrospective cohort study. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 157, 42–47 (2017).

Wood, C. B. et al. Existing predictive models for postoperative pulmonary complications perform poorly in a head and neck surgery population. J. Med. Syst. 43, 312 (2019).

Bovenzi, C. D. et al. Reconstructive trends and complications following parotidectomy: incidence and predictors in 11,057 cases. J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 48, 64 (2019).

Sou, W. K., Perng, C. K., Ma, H. & Shih, Y. C. Perioperative myocardial infarction in free flap for head and neck reconstruction. Ann. Plast. Surg. 88, S56–S61 (2022).

Scaglioni, M. T., Giovanoli, P., Scaglioni, M. F. & Yang, J. C. Microsurgical head and neck reconstruction in patients with coronary artery disease: A perioperative assessment algorithm. Microsurgery 39, 290–296 (2019).

Alho, O. P. et al. Differential prognostic impact of comorbidity in head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 29, 913–918 (2007).

Ch’ng, S., Choi, V., Elliott, M. & Clark, J. R. Relationship between postoperative complications and survival after free flap reconstruction for oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 36, 55–59 (2014).

Ankola, A. A. et al. Comorbidity, human papillomavirus infection and head and neck cancer survival in an ethnically diverse population. Oral Oncol. 49, 911–917 (2013).

Milne, S., Parmar, J. & Ong, T. K. Adult comorbidity Evaluation-27 as a predictor of postoperative complications, two-year mortality, duration of hospital stay, and readmission within 30 days in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 57, 214–218 (2019).

Katna, R. et al. Impact of comorbidities on perioperative outcomes for carcinoma of oral cavity. Ann. R Coll. Surg. Engl. 102, 232–235 (2020).

Arun, I. et al. Lymph node characteristics and their prognostic significance in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 43, 520–533 (2021).

Wang, L. & Shi, W. Metastatic lymph node burden impacts overall survival in submandibular gland cancer. Front. Oncol. 13, 1229493 (2023).

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgments are extended to colleagues of the department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery for their invaluable support in facilitating this study.

Funding

This work was supported by National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (Grant number 2022-PUMCH-C-070) and Fund for Medical Sciences, National Science Foundation (Grant number 2024-I2M-C&T-B-027).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.W. and T.Z. developed the study design. Q.L., ZY.Z. S.L.and L.W. contributed to data extraction and organization. L.W., Q.L., and ZH.Z. performed the statistical analysis. L.W.and T.Z. wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors performed a critical review of the manuscript and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted according to the ethical guidelines of the Ministry of Health of China. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board and the Office of Responsible Research Practices at PUMCH (NO. I-24PJ1762).

Informed consent

Due to the retrospective nature of the study, Institutional Review Board and the Office of Responsible Research Practices at PUMCH waived the need of obtaining informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, L., Li, Q., Zhu, Z. et al. Impact of preoperative comorbidities on postoperative complication rates and survival outcome in patients with head and neck cancer undergoing surgical treatment. Sci Rep 15, 38746 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22445-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22445-w