Abstract

Universal safety precaution is a central component of safe and high-quality service delivery at the facility level. Medical waste cleaners are more vulnerable than other health staff to medical waste-related health problems due to their work characteristics. The purpose of this study was to assess safety precaution knowledge, attitude, practice, and associated factors. An institution-based cross-sectional study design was conducted on 418 medical waste cleaners working in West and East Gojjam Zones government hospitals. Data were entered using Epidata version 3.1 and then exported to SPSS version 25.0 for cleaning, coding, and analysis. In bi-variable logistic regression, variables with a p-value ≤ 0.25 were selected for multivariable logistic regression. Finally, variables with a p-value < 0.05 were used to identify associated factors. In this study, safety precautions, good knowledge, favorable attitude, and good practice levels among cleaners were 70.6 (95% CI: 62, 75), 66.3 (95% CI: 62, 71), and 65.3 (95% CI: 61, 70), respectively. Working in a general hospital [AOR: 0.45 (95% CI: 0.25, 0.91) p = 0.02], > 24 months of work experience [AOR: 2.37 (95% CI: 1.33, 4.21) p = 0.003], and training [AOR: 2.55 (95% CI: 1.56, 2.16) p = 0.001] identified factors for knowledge. Good knowledge [AOR: 3.31 (95% CI: 2.05, 5.33) p = 0.001], working in primary hospital [AOR: 1.87 (95% CI: 1.15, 3.04) p = 0.01], and training [AOR: 1.91 (95% CI: 1.16, 3.13) p = 0.01] were associated with favorable attitude. Good knowledge [AOR: 2.08 (95% CI: 1.31, 3.30) p = 0.02], diploma and above educational [AOR: 0.60 (95% CI: 0.38, 0.97) p = 0.03] and working site in the hospital [AOR: 2.22 (95% CI: 1.03, 4.74) p = 0.04] were associated factors for good practice. Two-thirds or more of participants had adequate safety precaution knowledge, attitude, and practice. Working hospital levels, experience, education, training, and work site in the hospital were identified as factors. Routine training and working site rotation are very important to improve the safety precaution standards of cleaners. Hospital administrators and other stakeholders should give special attention to continuous professional education, mentoring, evaluation, and supervision required to implement standard safety precautions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Safety precaution is a central component of safe and high-quality service delivery at the facility level. Practicing adequate infection prevention practices among healthcare workers is essential to prevent the risk of hospital-acquired infections, including Human Immune Virus Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, hepatitis A and C, and other common bacterial and viral infections1,2,3,4. The World Health Organization defines biomedical waste as composed of organisms that can cause serious health problems for supporting staff, health workers, patients, and the public at large, which are produced at hospitals. These include needles, scalpel blades, gloves, bandages, cotton, medicine, blood and body fluids, human tissues, radioactive substances, and chemicals. These are also classified as highly infectious, infectious, and non-infectious5,6. However, about 40% of the hepatitis B and C infections and 2.5% of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infections among Healthcare Workers (HCWs) are attributed to occupational exposures at work7. Nearly 3 million HCWs face occupational exposure to blood-borne viruses; the incidence is higher in sub-Saharan Africa2,8,9.

Safety precaution refers to standard precautions, which are sets of infection prevention practices in healthcare settings to protect both healthcare workers and patients by reducing the risk of transmission of microorganisms from both recognized and unrecognized sources. This should be used by all healthcare workers, during the care of all patients, at all times, in all settings10,11. Healthcare-Associated Infections (HAIs) are infections that occur in a patient while receiving care11,12. Globally, 100 million people are affected by HAIs yearly by these avoidable infections1,13,14,15. The severity of the problem is 30% in high-income countries, whereas it has increased two to three times in low-income countries13. Nearly 10% of admitted patients in developed countries and 25% in developing countries acquire HAIs, resulting in poor health outcomes1, including increased hospitalization, high health system burden and financial costs, antimicrobial resistance, morbidity, and mortality1,14,15. HAIs cause about 99,000 deaths and $33 billion in costs yearly in the United States in 200212,13. It is also more than 16 million prolonged hospital stays in Europe, which accounted for €7 billion in healthcare costs1. The majority of HAIs are prevented through proper implementation of standard safety precautions14,15.

Mismanagement of hospital waste indicates a combination of improper handling of waste during generation, collection, storage, transport, and treatment. Safe healthcare waste management is fundamental for the provision of quality health services, people-centered care, and protection of the patients and staff, including safeguarding the environment. Safe management of healthcare waste reduces healthcare-related infections, increases trust and uptake of services, increases efficiency, and decreases the cost of service delivery4,16,17,18. The global action plan aims to ensure that all healthcare facilities have basic water, sanitation, and hygiene services by 2030, including safe healthcare waste management involving segregation, collection, treatment, and waste disposal3,6,19. Maintaining a clean environment and proper disposal of medical waste are social obligations of the hospitals, and medical waste cleaners have a greater responsibility to create a clean and safe working environment2,6,16. Hospital medical waste cleaners are at higher risk of work-related injuries, such as needle-stick injury, resulting in improper waste handling and management. The problem is severe in medical waste handlers due to a lack of adequate knowledge, a lack of a positive attitude about the waste management system, improper use or lack of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), and a lack of training on prevention mechanisms of work-related exposure17,19,20. Hence, they are at high risk of acquiring disease resulting from exposure to various work hazards compared to health professionals over the entire working time17,21.

In Saudi Arabia, hospital staff claimed that they were 60.4% knowledgeable, 26.9% had a positive attitude, and 24.6% practiced infection prevention22. A study of medical waste management among healthcare workers conducted in Thailand found that 89.5% had high knowledge, 91.9% had a positive attitude, and 92.2% practiced properly23. In Libya, 33.4% of participants have adequate knowledge, 50% believed that standard precautions prevent hospital-acquired infections, and 45.5% have good infection prevention practices24. Similarly, 89.9% of participants knew medical wastes are hazardous, 80% and 85% of hospital medical waste cleaners believed wearing personal protective equipment and proper segregation prevent cross-contamination, respectively, and 80.0% of them put wastes in the right plastic bags in Namibia25. Furthermore, the studies conducted in Addis Ababa public hospitals revealed that 51.2% cleaner had adequate knowledge, 80.1% had a positive attitude, and 35.7% had good safety precaution practices26, whereas 55.4% of healthcare workers had good knowledge, 83.3% had a positive attitude, and 66.1% had good infection prevention practices1. Waste handlers had 58.5% good knowledge, 50% good attitude, and 44.1% safe practice on safety precautions in Addis Ababa27. The good knowledge, positive attitude, and safe practice levels were 61%, 50%, and 38.2%, respectively, in the Somalia region medical waste handlers28. A study conducted at Gondar reported 81.6% adequate knowledge, 64.2% favourable attitude, and 57.4% good practice29, whereas 47.7% and 52.3% had good knowledge and practice, respectively30. Similarly, in Debre Markos Town, 45.5%, 78.2%, and 80.0% of medical waste handlers had adequate knowledge, a favourable attitude, and adequate practice, respectively31.

As evidence, educational status, working hours, experience, waste disposal site access, training, availability of PPE, age, being married, khat chewing, alcohol drank, job stress, supportive supervision, work rotation, availability of soap or hand rub alcohol, and workload are identified factors affecting safety precaution Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice (KAP) of medical waste cleaners23,25,26,31,32,33,34,35. One of the most common causes of work exposure injuries in healthcare facilities is the improper implementation of safety precautions. Medical waste cleaners in hospitals are at higher risk of work-related exposure (i.e., needle-stick injury, contamination of blood and body fluids, and other biological products). The previous studies focused on healthcare workers1,4,12,14,29,31,33,34,36,37, but few studies done on medical waste handlers17,26,27,28,30,38 whereas only one study found in this study setting with small sample size, which lacks representativeness31. The risk is increasing, but there is insufficient attention, particularly among medical waste cleaners. This highlights the need for scientific evidence using large samples in multicentre settings to address the bottleneck problem of improper hospital waste handling and disposal. The aim of this study was to determine safety precaution knowledge, attitude, practice, and identify associated factors among medical waste cleaners in West and East Gojjam Zones governmental hospitals. The findings can be helpful for programmers, planners, and policymakers for implementing innovative strategies for safe waste handling and management, promoting and maintaining a safe working environment, and preventing hospital-acquired infections.

Methods

Study design, setting, and population

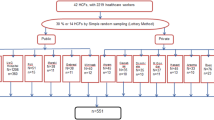

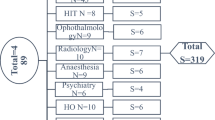

An institution-based cross-sectional study design was conducted. The study was conducted in the West and East Gojjam Zones in the Amhara region. It is located 375 km and 300 km, respectively, from Addis Ababa, the capital city. There are 21 governmental hospitals in these two zones, i.e., Felege Hiwot Specialized Hospital, Debre Markos Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Tibebe Ghion Specialized Hospital, Mota and Finote Selam General Hospital, and 16 Primary Hospitals (Mertolemariyam, Debrework, Bichena, Yedwuha, Dejen, Lumamie, Yejubie, Bibugn, Dembecha, Burie, Durbetie, Feresbet, Liben, Adiet, Debre Elias, and Adisalem). All medical waste cleaners working in these 21 governmental hospitals are the source population. Cleaners who annually or delivery leave at the time of data collection were excluded from this study. The study was conducted from July 1, 2023 to August 30, 2023.

Sample size determination and sampling procedure

The sample size was calculated using a single population proportion formula study conducted in Debre Markos Town health facilities by considering the proportion of 45.5% knowledge, 78.2% attitude, and 80% practices of safety precaution31.

Where:

n = required sample size.

Z α /2= 95% confidence (1.96).

P = 78.2% proportion of good attitude.

d = 4% margin of error.

We checked by using KAP, considering the above assumption, and the larger sample size calculated using practice was 409. The final sample size, considering a 10% non-response rate, was 450. There are 21 governmental hospitals in the West and East Gojjam Zones. The numbers of cleaner working in the hospital are few in number, due to this reason all cleaners working in the governmental hospitals were eligible for the study. There were 671 medical waste cleaners presented in 21 hospitals during this study period. After receiving lists of cleaners in each hospital, a simple random sampling lottery method was used for each hospital to select participants for the interview.

Operational definitions

Knowledge safety precaution

Is defined as having a clear awareness and understanding of medical waste cleaners on safety precaution of infection prevention activities, scored 1 for “yes” and 0 for “no and not sure” responses.

Good knowledge

Those medical waste cleaners who responded correctly to more than 13 out of 18 items in the knowledge questions, which scored a minimum of 75% and above on the knowledge assessment questions.

Poor knowledge

Those medical waste cleaners who answered 13 or less out of 18 knowledge questions, which scored less than 75% on the knowledge assessment questions26.

Attitude safety precaution

This is based on the personal view of medical waste cleaners on infection prevention activities assessed using a Likert scale: agree, neutral, and disagree. This scale question is grouped into two categories, with 1 for “agree” and 0 for “neutral and disagree”.

Favourable attitude

Those medical waste cleaners who responded above 10 out of 17 item attitude questions correctly, which scored a minimum of 60% and above on attitude assessment questions.

Unfavourable attitude

Those medical waste cleaners who responded 10 and below out of 17 attitude questions, scored less than 60% on attitude assessment items17.

Practice of safety precaution

This is an act/skill of medical waste cleaners on infection prevention activities practiced, scored as 1 for “always/yes” and 0 for “sometimes/no”.

Good practice

Those medical waste cleaners who responded 4 or above out of 8 items in the practice question, which scored a minimum of 50% or above on the practice assessment questions.

Poor practice

Those medical waste cleaners who responded below 4 out of 8 items in the practice question scored less than 50% on the practice assessment questions38.

Alcohol use

Is any kind of use of alcohol during work time based on the degree of frequency and categorized as always (who drink alcohol all working days per week), usually (those who were drink alcohol three to four working days per week), and sometimes (who were drink alcohol one to two working days per week)26.

Khat chewing

It is the practice of chewing khat based on frequency and categorized as always (who chew khat all working days per one week), usually (who chew khat three to four working days per one week), and sometimes (who chew khat one to two working days per one week)26.

Cigarette smoking

Smoking of cigarettes based on the degree of frequency and categorized as always (who smoked all working days per week), usually (who smoked three to four working days per week), and sometimes (who smoked cigarettes one to two working days per week)26.

Data collection tools, procedures, and quality control

A structured interview-administered questionnaire was used to collect data. The data collection tool was prepared after reviewing existing literature26,27,28,29,30,31,33,36,38. The questionnaire was prepared originally in English and then translated into the local language (Amharic), and back translated into English to maintain consistency. Data was collected through a face-to-face interview-administered questionnaire. The interview was conducted in the respective establishment and in a place convenient for both the respondents and the interviewer during working hours. The questionnaire had four sections: socio-demographic characteristics, 18-item knowledge questions, 17-item attitude questions, and 8-item practice questions of safety precautions for medical waste cleaners. The internal consistency of the tool was checked using the Cronbach alpha test. The reliability coefficient for knowledge, attitude, and practice items had a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.821, 0.752, and 0.732, respectively. Twenty environmental health graduate data collectors and two Master’s of Public Health supervisors participated. The tool was pre-tested at Debre Markos town health centers, which are not study-eligible health facilities. The quality of the data was assured through the careful design of the tool, training for data collectors and supervisors, and close supervision of the entire data collection period by the supervisor and principal investigators.

Data processing and analysis

EpiData version 3.1 was used for data entry and then exported to SPSS version 25.0 for data cleaning, coding, and further analysis. Descriptive statistics were presented using frequency tables, mean, standard deviation, and ranges. In bivariable logistic regression, variables with a p-value ≤ 0.25 were selected for multivariable logistic regression analysis. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test was checked for the model’s goodness of fit. Finally, in multivariable logistic regression analysis, variables with a p-value < 0.05, 95% Confidence Interval (CI) corresponding to Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) were used to identify statistically associated factors of safety precaution knowledge, attitude, and practice among medical waste cleaners.

Results

Socio-demographic, behaviour, and health facility-related characteristics

In this study, 418 medical waste cleaners participated with a response rate of 93%. The median age of respondents was 34 years, an inter quartile range of (31, 37). About 203 (48.6%) of study participants were aged between 20 and 30 years. The majority (97.6%) of the respondents were Orthodox Christian followers. Eighty-eight (21.1%) had a history of alcohol drinking, and neither of the study participants smoked cigarettes nor chewed khat. (Table 1).

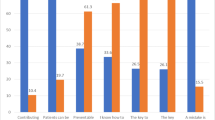

Safety precaution knowledge of the study participants

The overall good knowledge of the study was 70.6 (95% CI: 62, 75). Three hundred thirty-six (80.4%) study participants knew the recommended maximum medical waste storage time, 164 (39.2%) of them knew when to start HIV post-exposure prophylaxis, and 327 (78.2%) cleaners knew the maximum level filling safety box. Only 250 (59.8%) of medical waste cleaners knew the correct signs of biohazard bags. Three hundred five (77.8%), 347 (83%), and 362 (86.6%) of the study participants reported that general, infectious, and sharp waste should be disposed of using a black, yellow, and safety box, respectively (Table 2).

Safety precaution attitude of the respondents

In this study, about 66.3 (95% CI: 62, 71) of the participants had favourable attitudes towards safety precautions. Three hundred sixty-one (86.4%) respondents believed that HIV post-exposure prophylaxis would help to prevent HIV infection (Table 3).

Safety precaution practices of the respondents

The overall good practice of the study was 65.3 (95% CI: 61, 70). Four hundred eight (97.6%), 322 (77.0%), and 111 (26.6%) respondents used always heavy-duty gloves, aprons, and boots, respectively. Two hundred nineteen (71.5%) of participants disinfected reusable cleaning materials after they used them, and 340 (81.6%) separately transported medical wastes (Table 4).

Associated factors of safety precaution knowledge among medical waste cleaners

In multivariable logistic regression, working hospital level, work experience, and training were statistically significant factors. The odds of medical waste cleaners working in general hospitals’ safety precaution knowledge were 55% lower compared to cleaners who were working in comprehensive specialized hospitals [AOR: 0.45 (95% CI: 0.25, 0.91) p = 0.02]. The odds of medical waste cleaners with > 24 months’ work experience were 2.37 times more likely to have good safety precaution knowledge compared to cleaners who had ≤ 24 months of work experience [AOR: 2.37 (95% CI: 1.33, 4.21) p = 0.003]. Similarly, medical waste cleaners who received waste management training were 2.55 times more likely to have good safety precaution knowledge compared to their counterparts [AOR: 2.55 (95% CI: 1.56, 2.16) p = 0.001] (Table 5).

Associated factors of safety precaution attitude among medical waste cleaners

In multivariable logistic regression, knowledge, working hospital level, and training were statistically significant factors for a favourable attitude. The odds of medical waste cleaners who had a good knowledge having more than three times a favourable safety precautions attitude compared to their counterparts [AOR: 3.31 (95% CI: 2.05, 5.33) p = 0.001]. The odds of medical waste cleaners who had worked in primary hospitals were 1.87 times more likely to have a favourable safety precaution attitude compared to those who had worked in comprehensive specialized hospitals [AOR: 1.87 (95% CI: 1.15, 3.04) p = 0.01]. The odds of medical waste cleaners who had received training were nearly two-fold favourable safety precaution attitude compared to cleaners who had not been trained [AOR: 1.91 (95% CI: 1.16, 3.13) p = 0.01] (Table 6).

Associated factors of safety precaution practice among medical waste cleaners

In multivariable logistic regression, knowledge, educational status, and current working site in the hospital were statistically significant factors for good practice. The odds of medical waste cleaners who had a good knowledge were two-fold, good safety precaution practice compared to cleaners who had a poor knowledge [AOR: 2.08 (95% CI: 1.31, 3.30) p = 0.02]. The odds of medical waste cleaners having a secondary education level were 40% less likely to practice safety precautions compared to those with a diploma and above education level [AOR: 0.60 (95%CI: 0.38, 0.97) p = 0.03]. The odds of medical waste cleaners who were working in the outpatient departments were 2.22 times more likely to have good safety precaution practices compared to cleaners working in the emergency ward [AOR: 2.22 (95% CI: 1.03, 4.74) p = 0.04] (Table 7).

Discussion

This institution-based cross-sectional study was designed to assess safety precaution knowledge, attitude, practice, and associated factors among medical waste cleaners working at governmental hospitals. In this study, the good safety precaution knowledge was 70.6 (95% CI: 62, 75). This finding is greater than studies reported in different areas 51.2% to 58.6% in Addis Ababa26,27, 47.7% in Gondar30, 45.5% in Debre Markos31, 54.6% in Harari and Dire Dawa regions33, 61% Somalia region28, 41% in Nigeria39, and 60.4% in Saud-Arabia40. The differences in knowledge level may be due to study area, period, sample size, measurement, and the variation in the included study participants. The current study, conducted in the hospital setting with a relatively large sample size, may be a possible attribute of increased knowledge level. Whereas in the previous study, knowledge level was measured among healthcare workers33, using a cut-off point above the mean value31,33. However, this finding is lower than previous studies reported 81.6% in Gondar29, 84.7% in Debre Markos34, 74.1% in Addis Ababa17, 96.1% in South Wollo Zone14, 89.9% in Namibia25, 97.3% in Nigeria41, 89.5% in Thailand23, and 90% in Saudi-Arabia42. This variation might be due to the fact that the majority of the previous studies conducted in a single institution included only health professionals or all healthcare workers with low sample sizes and measurement differences between the studies14,17,25,34,41,42. These reasons are possibly increasing the knowledge level of previous evidence.

Medical waste cleaners working hospital level is statistically significant for safety precaution knowledge: The odds of medical waste cleaners working in general hospitals were 55% less likely to have good safety precaution knowledge compared to working in comprehensive specialized hospitals. The level of hospital care increases, and the waste generation, collection, segregation, and management processes also increase. This may result in more emphasis being given by the cleaners and infection prevention team. It is also likely that the availability of training, guidelines, and infection prevention protective materials at higher hospitals results in regular monitoring and inspection to ensure an aseptic hospital environment.

The working experience of the respondents was a significantly associated factor for safety precaution knowledge: Cleaners who had > 24 months of work experience were 2.37 times more likely to have good safety precaution knowledge compared to their counterparts. This finding is supported by previous studies reported in Debre Markos, Addis Ababa, Nigeria, and Saudi Arabia26,31,34,43. This is due to increased work experience, which may predispose to safety precaution training, seminars, and repeated exposure, which may become familiarized and improve performance skills. Experience can be fundamental in ensuring that cleaners realize the potential risks and hazards associated with their duties36,37,44.

The respondents who received training on medical waste management were identified as significant factors: Cleaners who received training on medical waste management were 2.55 times more likely to have good safety precaution knowledge. This finding is consistent with findings in Debre Markos, Addis Ababa, Nigeria, and Saudi Arabia26,31,43. On-job and off-job training improve the awareness, understanding levels, and performance skills of the participants. Cleaners who are regularly trained may become more aware of the potential hazards and familiar with the importance of adhering to and complying with safety protocols and standards36,44,45,46,47.

The level of favourable safety precaution attitude was 66.7 (95% CI: 62, 71). This finding is consistent with the finding reported 64.2% in Gondar29. This may be due to a similar tool used to measure attitude. Whereas it is greater than 50% in Addis Ababa27, the Somalia region28, and in Libya24. The variation may be due to the study setting and period. This is also lower than previous findings conducted 78.2% in Debre Markos31, 98.8% in Addis Ababa17, 77.2% in South Wollo Zone14, 91.9% in Thailand23, and 98% in Nigeria39. The previous study conducted in Thailand is a multicentre study with a high level of awareness and technologically advanced settings. The study reported in Nigeria was conducted in one hospital, and a study conducted in Debre Markos was multicentre with a very small sample size (55 cleaners). This may be attributed to a high attitude level. The cut-off point for the current study was 60% using 17-item attitude assessment questions, whereas previous evidence used above the mean, which may be the possible reason for variations in attitude17,23,31.

Medical waste cleaners who had good knowledge had 3.31 times favourable safety precaution attitudes compared to those with poor knowledge. This finding was supported by previous studies conducted in Debre Markos34 and Thailand23. The level of knowledge is very important to the attitude status of the individual. Knowledge about the mode of transmission, management, treatment, and prevention of hospital-related infections is imperative for hospital-acquired infection risk reduction, which may influence the attitude37.

Study participants working in primary hospitals were 1.87 times more likely to have favourable safety precaution attitudes compared to those working in comprehensive specialized hospitals. According to the WHO report, healthcare waste generation depends on the type of healthcare establishment, level of specialization, patient flow, and proportion of reusable items used20,48,49. Despite this, it is due to the service expansion that increases the magnitude of waste generated and infectiousness too. The patient flow, magnitude, and infectiousness of wastes generated in comprehensive specialized hospitals were increased compared to primary hospitals20. This may cause high workload burden and burnout, resulting in a cleaner lower level of attitude.

Participants who received training on medical waste safety and management had nearly two-fold favourable safety precaution attitudes compared to those who did not receive training. This finding was supported by the study reported in Ethiopia50. Pre-employment and in-service training are very crucial to reducing potential risks posed due to infectious waste handling. Medical waste cleaners should be trained on the safe handling, collection, and disposal principles of medical waste to reduce hospital-associated infections. It is also an encouraging effect on knowledge acquisition and behaviour enhancement37,45,46,47.

In this study, the good safety precaution practice was 65.3 (95% CI: 61, 70). This is in line with the study reported 66.1% in Addis Ababa1 and 69.5% in Nigeria51. This is greater than findings reported 25.3% to 44.1% in Addis Ababa17,26,27, 52.3% to 57.2% in Gondar29,30, 57.3% in Debre Markos34, 47.3% Southwestern Ethiopia38, 53.7% South Wollo Zone14, 38.2% Somalia region28, 45.5% in Libya24, 8.3% in Nigeria39, 50% in Ghana52, and 24.6% in Saudi Arabia22. The discrepancy might be due to the study setting, measurement, study population, and differences in the availability of PPE materials. The majority of previous studies reported practice with a small sample size22,26,27,34,38,39,52 and only health professionals or healthcare workers in one study setting29,34,52. This probably affected the overall practice level. Whereas, this is lower than the findings reported by 80% in Debre Markos28, 92.2% in Thailand23, and 73.6% in India51. The variation resulted in a setting difference; the previous study was conducted in Debre Markos Town with 55 study populations. The previous evidence conducted in Thailand and India has significant differences in health facility setups, population differences, including healthcare workers, educational, and awareness levels. This might be the possible reason to increase the practice level of medical waste cleaners. In addition, this study measures practice level using an interview questionnaire only, which may obscure the actual practice level.

Cleaners who had good knowledge were 2 times more likely to have good safety precaution practices compared to those with poor knowledge. This finding is supported by previous studies conducted in Somalia, Addis Ababa, Gondar, Southwestern Ethiopia, and Nigeria26,27,28,30,38,39. Knowledgeable cleaners find it easy to put their knowledge into practice. They are also easy to change behaviour, learned from their previous exposure/practice, and proactive learners from the surrounding environment. Medical waste cleaners who have secondary education levels were less likely to have safety precaution practices compared to those with higher education levels. This result is similar to the studies reported in Addis Ababa, Southwestern Ethiopia, Debre Markos, Botswana, and Palestine26,32,34,38. Educated medical waste cleaners are able to practice proper and safe infection prevention practices through easy understanding and adhering to standard protocols, guidelines, hazard symbols in the waste containers, training, and other performance follow-ups18,53,54.

Finally, medical waste cleaners who were working in the outpatient departments were 2.22 times more likely to have good safety precaution practices compared to those working in the emergency ward. This is in line with study results in Addis Ababa17,26. The amount and type of waste generated in the outpatient department were more likely to be smaller and less likely to be infectious compared to other wards that undertook minor and major procedures37. This may facilitate easy application of the safety precaution procedures other than emergency and other wards.

The implication of the study revealed that hospital level, experience, training, education level, and working site rotations are very important explanatory variable, which helps to improve standard safety precautions in medical waste cleaners. Designing new interventional strategies like continuous educational development programs, regular mentoring, and supportive supervision activities is required to improve the medical waste cleaner standard safety precaution.

Limitations of the study

The practice level of the medical waste cleaners is not measured by using an observation checklist, which may be prone to bias, and the study did not include health centers and private health facilities. The findings of this study may have a social desirability bias, as a result of self-report information trustworthiness. There is also an inability to infer the causal association due to the cross-sectional study design limitation.

Conclusions

Nearly two-thirds or more of the participants had good knowledge, a favourable attitude, and good practice of safety precautions, which is unacceptable to prevent hospital-acquired infections. Working hospital level, working experience, and training are significantly associated with good knowledge. Participants’ knowledge, working hospital, and training were significantly associated with favourable attitudes, whereas knowledge, education level, and current working site in the hospital were significantly associated with good safety precaution practices. This study showed that there are significant gaps in safety precautions among medical waste cleaners, which is very important to prevent hospital-acquired infections. Routine pre-employment and in-service training, supportive supervision, and working site rotations are desirable to improve the knowledge, attitude, and practice levels of safety precautions. Further, hospital administrators and other stakeholders should give special attention to establishing a continuous professional development program, regular mentoring, evaluation, and supervision required for ensuring safety precautions and effective infection prevention and control at the hospital level. Future studies with an observational checklist supported with qualitative information are desirable to address the limitations of this study.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COR:

-

Crude odds ratio

- HCWs:

-

Healthcare workers

- HIV:

-

Human immune virus

- HAIs:

-

Healthcare-associated infections

- KAP:

-

Knowledge, attitude, and practice

- PPE:

-

Personal protective equipment

References

Sahiledengle, B. G. A., Getahun, T. & Hiko, D. Infection prevention practices and associated factors among healthcare workers in governmental healthcare facilities in addis Ababa. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 28 (2), 177–186 (2018).

Shiferaw, Y. & AT, Mihret, A. Hepatitis B virus infection among medical waste handlers in addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Res. Notes. 4 (479), 1–7 (2011).

Chartier, Y. Safe Management of Wastes from health-care Activities (World Health Organization, 2014).

Amsalu, A. & KH Healthcare workers’ compliance and factors for infection prevention and control precautions at Debre Tabor referral Hospital, Ethiopia. PAMJ - One Health 7(35). (2022).

Aldeguer, C. T. M. A. E., Alfaro, R. C. L., Alfeche, A. A. Z., Abeleda, M. C. M. & Abilgos, R. G. V. An analytical cross-sectional study on the knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) on biomedical waste management among nurses and medical technologists in the Philippines. Health Sci. J. 10 (1), 1–9 (2021).

Singh, A. S. A. & Maurya, N. K. Health care waste management. Int. J. Sci. Res. Rev. 8 (2), 410–416 (2019).

Wilburn, S. Q. EG: preventing needlestick injuries among healthcare workers: A WHO-ICN collaboration. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health. 10 (4), 451–456 (2004).

Reda, A. A., FS, Mengistie, B. & Vandeweerd, J. M. Standard precautions: occupational exposure and behavior of health care workers in Ethiopia. PLoS One. 5 (12), e14420 (2010).

FitzSimons, D. F. G. et al. Hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus and other blood-borne infections in healthcare workers: guidelines for prevention and management in industrialised countries. Occup. Environ. Med. 65 (7), 446–451 (2008).

World Health Organization. Standard precautions for the prevention and control of infections. (2022).

Ethiopian Ministry of Health. National infection prevention and control reference manual for healthcare service providers and managers. (2023).

Bekele, T. A. T., Ermias, A. & Arega Sadore, A. Compliance with standard safety precautions and associated factors among health care workers in Hawassa university comprehensive, specialized hospital, Southern Ethiopia. PLoS One. 15 (10), e0239744 (2020).

Babore, G. O. E. Y., Mengistu, D., Foga, S., Heliso, A. Z. & Ashine, T. M. Adherence to infection prevention practice standard protocol and associated factors among healthcare workers. Global J. Qual. Saf. Healthc. 7 (2), 50–58 (2024).

Berihun, G. G. A. et al. Adherence to infection prevention practices and associated factors among healthcare workers in Northeastern Ethiopia, following the Northern Ethiopia conflict. Front. Public. Health. 12, 1433115 (2024).

Sahiledengle, B., Tekalegn, Y. & Woldeyohannes, D. The critical role of infection prevention overlooked in Ethiopia, only one-half of health-care workers had safe practice: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 16 (1), e0245469 (2021).

Elling, H. B. N. et al. Role of cleaners in Establishing and maintaining essential environmental conditions in healthcare facilities in Malawi. J. Water Sanitation Hygiene Dev. 12 (3), 302 (2022).

Mariam, F. A. AZ: medical waste handling practice and associated factors among cleaners in public hospitals under addis Ababa health Bureau, addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Research & Reviews: J. Med. Health Sci. 7(4). (2018).

Angeloni, N. L. N. et al. Impact of an educational intervention on standard precautions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Brazilian J. Nurs. 76 (4), e20220750 (2023).

Capoor, M. R. Current perspectives on biomedical waste management: Rules, conventions and treatment technologies. Ind. J. Med. Microbiol. 35 (2), 157–164 (2017).

Debere, M. K., GK, Alamdo, A. G. & Trifa, Z. M. Assessment of the health care waste generation rates and its management system in hospitals of addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2011. BMC Public. Health. 13 (28), 1–9 (2013).

Alemayehu, T., Worku, A. & Assefa, N. Medical waste collectors in Eastern Ethiopia are exposed to high Sharp injury and blood and body fluids contamination. J. Prev. Infect. Control. 2, 2 (2016).

Hamid, H. A. et al. Assessment of hospital staff knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAPS) on activities related to prevention and control of hospital-acquired infections. J. Infect. Prev. 8 (1), 1–7 (2019).

Akkajit, P. & RH, Assawadithalerd, M. Assessment of knowledge, attitude, and practice in respect of medical waste management among healthcare workers in clinics. J. Environ. Public Health 2020. (2020).

Abdelbai, E. A. A., SA, Suleman, E. A. & Jamal Abdulsalam, A. A. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices for Standard Precautions in Infection Control among Hospital Staff in the Fezzan region, Southern Libya (Shendi University Repository, 2020).

Haifete, A. N. & JA, Iita, H. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of healthcare workers on waste segregation at two public training hospitals. Eur. J. Pharm. Med. Res. 3 (5), 674–689 (2016).

Tesfaye, T. G. T. T. & Dinka, T. G. Safety precaution practices and associated factors among public hospital cleaners: case in addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Int. J. Res. Eng. Sci. (IJRES). 8 (12), 10–21 (2021).

Tekle, T. A. T., Wondimagne, A. & Abdo, Z. A. Safety practice and associated factors among waste handlers in governmental hospitals in addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Eur. J. Prev. Med. 9 (4), 107–113 (2021).

Mahamed, A. A. Safety practice and associated factors among waste handlers at selected government hospitals in Somali Region, Eastern Ethiopia, 2021: Institutional-based cross-sectional study. Psychol. Journal: Res. Open. 6 (3), 1–11 (2024).

Yazie, T. D. & SG, Abebe, W. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of healthcare professionals regarding infection prevention at Gondar university referral hospital, Northwest ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Res. Notes. 12 (563), 1–7 (2019).

Tesfaye, A. H., MT, Belay, B. D. & Yenealem, D. Y. Infection prevention and control practices and associated factors among healthcare cleaners in Gondar city: an analysis of a cross-sectional survey in Ethiopia. Risk Manage. Healthc. Policy. 16, 1317–1330 (2023).

Deress, T. J. M., Girma, M. & Adane, K. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of waste handlers about medical waste management in Debre Markos town healthcare facilities, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Res. Notes. 12 (146), 1–7 (2019).

Mugabi, B. H. S. & Chima, S. Assessing knowledge, attitudes, and practices of healthcare workers regarding medical waste management at a tertiary hospital in botswana: A cross-sectional quantitative study. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 21 (12), 1627–1638 (2018).

Alemayehu, T. & WA, Assefa, N. Knowledge and practice of health workers about standard precaution: special emphasis on medical waste management in Ethiopia. International J. Infect. Control 14(2). (2018).

Desta, M. A. T., Sitotaw, N., Tegegne, N., Dires, M. & Getie, M. Knowledge, practice and associated factors of infection prevention among healthcare workers in Debre Markos referral hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 18 (465), 1–10 (2018).

Yakob, E. L. T. & Henok, A. Knowledge, attitude and practice towards infection control measures among Mizan-Aman general hospital workers, South West Ethiopia. J. Community Med. Health Educ. 5 (5), 1–8 (2015).

Kasa, A. S. T. W. et al. Knowledge towards standard precautions among healthcare providers of hospitals in Amhara region, Ethiopia, 2017: A cross-sectional study. Archives Public. Health. 78 (127), 1–8 (2020).

Senbato, F. R. et al. Compliance with infection prevention and control standard precautions and factors associated with noncompliance among healthcare workers working in public hospitals in addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 13 (32), 1–12 (2024).

Ketema, S. M. A., Demelash, H., Mariam, G., Mekonen, M. & Addis, S. Safety practices and associated factors among healthcare waste handlers in four public hospitals, Southwestern Ethiopia. Safety 9 (41), 1–12 (2023).

Miner, C. A., IE, Omeiza, D. S., Ejinmah, B. C. & Akims, N. D. Knowledge, attitude and practice of hospital waste disposal among cleaners in a tertiary health institution in plateau State, Nigeria. Highland Med. Res. J. 21 (1), 11–18 (2021).

Bdour, A. N., TZ, Al-Momani, T. & El-Mashaleh, M. Analysis of hospital staff exposure risks and awareness about poor medical waste management: A case study of the Tabuk regional healthcare system, Saudi Arabia. J. Commun. Disease. 47 (2), 1–13 (2015).

Samuel, S. O. & KO, Musa, O. I. Awareness, practice of safety measures, and the handling of medical wastes at a tertiary hospital in Nigeria. Nigeria Postgrad. Med. J. 17 (4), 297–300 (2010).

Alghamdi, N. A. AS: knowledge about the standard precautions among health care workers in primary health care Centers, ministry of health, Jeddah 2017. Int. J. Med. Res. Professionals. 4 (6), 155–158 (2018).

Onubogu, C. U. et al. Knowledge and compliance with standard precaution among healthcare workers in a south-east Nigerian tertiary hospital. Orient. J. Med. 33 (1–2), 22–34 (2021).

Ghabayen, F. A. et al. Knowledge and compliance with standard precautions among nurses. SAGE Open. Nursing 9. (2023).

Bęś, P. SP: analysis of the effectiveness of safety training methods. Sustainability 16 (2732), 1–21 (2024).

Ramzi, Z. S. The effect of training course on knowledge, attitudes, and skills regarding health and safety among university students: A quasie-xperimental study. Pakistan J. Med. Health Sci. 14 (3), 1–6 (2020).

Uchendu, O. C. & DA, Owoaje, E. T. Effect of training on knowledge and attitude to standard precaution among workers exposed to body fluids in a tertiary institution in South-west Nigeria. Annals Ib. Postgrad. Med. 18 (2), 100–105 (2020).

Meleko, A., Tesfaye, T. & Henok, A. Assessment of healthcare waste generation rate and its management system in health centers of bench Maji zone. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 28 (2), 125–134 (2018).

Prüss, A. & Rushbrook, G. E. (eds) Safe Management of Wastes from health-care Activities (World Health Organization, 1999).

GD. G: Knowledge, attitude, and practices on occupational health and safety principles among cleaners: the case of Tikur Anbassa specialized referral Hospital, addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Open Health 3(1) 22–33. (2022).

Awodele, O. A. A. & Oparah, A. C. Assessment of medical waste management in seven hospitals in Lagos, Nigeria. BMC Public. Health. 16 (269), 1–11 (2016).

Akagbo, S. E. & NP, Ackumey, M. M. Knowledge of standard precautions and barriers to compliance among healthcare workers in the lower Manya Krobo District, Ghana. BMC Res. Notes. 10 (432), 1–9 (2017).

Gaikwad, U. N. et al. Educational intervention to foster best infection control practices among nursing staff. Int. J. Infect. 5 (3), 1–7 (2018).

Mengesha, Y. D. Z. et al. Factors associated with the level of knowledge and self-reported practice toward safety precautions among factory workers in East Gojjam Zone, Northwest Ethiopia. SAGE Open. Med. 11, 1–11 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Debre Markos University, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, for providing ethical clearance, data collectors, supervisors, and hospital staff for their support and cooperation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DA contributed to the idea conception. DA, ATT, and MWA developed a design of methodology. ATT, DA, SDH, MWA, and BE contributed to data entry analysis and data interpretation. BE, MWA, and SDH conducted data supervision and validation. ATT, DA, BE, SDH, and MWA reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from Debre Markos University, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Ethical Review Committee (HSC/R/C/Ser/PG/Co/91/11/14). Letters of support were obtained from the West and East Gojjam Zonal Health Department, and a permission letter was received from each hospital administration. Verbal informed consent was received from each study participant after a possible explanation of the purpose of the study and before the commencement of data collection. The participants were informed that their participation was voluntary and that they had the right to withdraw from the interview at any time. The respondents’ name was not recorded on the questionnaires to ensure anonymity and confidentiality. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Telayneh, A.T., Awudew, D., Endalew, B. et al. Safety precaution knowledge, attitude, practice, and associated factors among medical waste cleaners in governmental hospitals, Northwest Ethiopia. Sci Rep 15, 42272 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22577-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22577-z