Abstract

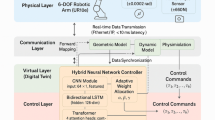

The nursing robot, equipped with a 6-degree-of-freedom (6-DOF) humanoid manipulator, has been applied in elderly and disabled care to execute complex and random nursing tasks with its advantages in automation and intelligence. Especially, when the nursing robot performs daily care tasks such as serving tea and pouring water, the good trajectory tracking performance of its manipulator is a crucial capability. However, nonlinear coupling, model uncertainty, joint friction, unknown external disturbances, and particularly the fact that manipulator does not satisfy Pieper criterion-are the main challenges, which degrade control performance. Few existing studies have simultaneously addressed all these issues to improve the control accuracy of the manipulator. Therefore, to achieve the good tracking performance for manipulator, a robust control method combining sliding mode control (SMC), radial basis function neural network (RBFNN), and nonlinear disturbance observer (NDO) is proposed. An improved Jacobian-based gradient descent method solves inverse kinematics, with the improved gradient descent driven inverse kinematics (IGDIK) module ensuring accuracy; RBFNN compensates for model uncertainty; NDO handles disturbances and friction. Simulations and experiments demonstrate enhanced trajectory tracking accuracy and stability, validating its effectiveness for the target manipulator.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Population aging is intensifying elderly care pressure. Nursing robots alleviate this pressure by performing complex, random tasks—such as feeding and medication delivery—in homes and hospitals. Our laboratory has developed a specific nursing robot (as shown in Fig. 1), with its 6-DOF humanoid manipulator as the core for task execution. When performing tasks, the manipulator needs high-precision trajectory tracking. Thus, designing a high-precision trajectory tracking controller is key to ensuring the robot’s reliable operation.

However, the humanoid manipulator faces multiple challenges in practical applications, directly limiting improvements in trajectory tracking accuracy. On one hand, its humanoid structure violates the Pieper criterion, making inverse kinematics difficult to solve and hindering the rapid generation of accurate joint control commands. On the other hand, issues like dynamic model uncertainty, unknown external disturbances, and joint friction in nursing scenarios further increase control difficulty. These problems are mutually coupled, and conventional control methods struggle to address them simultaneously. Therefore, it is necessary to develop an appropriate controller to simultaneously address all these issues to improve the control accuracy of the manipulator.

Literature review

For the problem of inverse kinematics solving in manipulators that do not satisfy the Pieper criterion, relevant research has been conducted. Dereli et al.1 employed the Firefly algorithm for 7-DOF manipulators. Bai et al.2 proposed a hybrid FABRIK-ANN method. Zhou et al.3 reduced 6-DOF calculation time. Ames et al.4 used deep learning. Gao et al.5 optimized BP neural networks. However, these methods overlook its structural nonlinearity, limiting practicality. This study thus proposes an improved gradient descent method for such non-Pieper systems, validated for high accuracy, efficiency, and resistance to local optima.

SMC is valued for its simplicity, strong robustness, and fast response, making it relevant for manipulator control. For example, Yin et al.6 developed an adaptive fuzzy SMC. Tran et al.7 integrated RBFNN with SMC for 3-DOF manipulators. Yin et al.8 achieved kinematic control of humanoid upper-body robots via virtual flexible joint dynamics and a quasi-sliding mode observer. Xiao et al.9 validated SMC on a six-axis BU-RASL manipulator. Dachang et al.10 proposed an adaptive back-stepping control and validated it on a planar two-link. Su et al.11 proposed a non-singular terminal SMC with an integral sliding surface. However, Tran et al.7 treated model uncertainty as a disturbance, failing to address it in practical nursing tasks, highlighting the need for improved strategies. To address this, Song et al.12 designed a nonsingular fast terminal sliding mode controller with a new nonlinear disturbance observer to enhance control accuracy and anti-interference ability. Wei et al.13 introduced a disturbance observer.

Beyond SMC, RBFNN excel in dynamic model approximation for nonlinearities. Liu et al.14 showed RBFNN outperforms BP networks in generalization. Stoffel et al.15 noted its superiority over FFNN and DCNN. Narayan et al.16 used RBFNN for uncertain dynamics. Xin et al.17 combined it with fuzzy SMC. Sun et al.18 reduced chattering via T-S fuzzy switching. Notably, these studies16,17,18 overlook unforeseen external disturbances, limiting applicability in care environments.

To address external disturbances, researchers have optimized SMC. Li et al.19 and Nguyen et al.20 optimized SMC for convergence and robustness. Sun et al.21 used full-drive models. Chen et al.22 integrated RBFNN with disturbance observers for better control. Narayan et al.23 and Liu et al.24 combined RBFNN with fuzzy control. However, these methods remain unvalidated for 6-DOF humanoid manipulators, which face unique, unaddressed challenges including non-Pieper criterion models, model uncertainty, joint friction, and external disturbances.

In this paper, a sliding mode robust control strategy integrating RBFNN and NDO, combined with an improved Jacobian-based gradient descent method, is proposed. Contributions include: (1) An improved Jacobian-based gradient descent method, effectively solving inverse kinematics for 6-DOF non-Pieper humanoid manipulators with higher accuracy and smoothness. (2) A novel RBFNN + NDO control strategy: RBFNN approximates the dynamic model with online parameter adjustment via weight adaptive law; NDO compensates composite disturbances (friction + external disturbances) in real time.

System description

This paper focuses on the 6-DOF humanoid manipulator of the Seed Noid R7F nursing service robot, which is the core research object. The Seed Noid R7F is a humanoid robot with a life-size structural design, as illustrated in Fig. 1. It has a height of 141–170 cm (with a prismatic joint in the legs), a weight of approximately 80 kg, and two identical 6-DOF robotic manipulators. In addition, the Seed Noid R7F robot is equipped with an industrial motherboard, a Linux system controller based on a mini PC, an Android touchscreen tablet, four omnidirectional wheels under the base layer, and six ultrasonic sensors (0.02–3 m) on the base layer. Furthermore, it is equipped with two 3D D435 depth cameras (one on the head and one on the chest), two angle sensors (0.06–4 m, -120°~120°), two remote control boards for control and communication, and two rechargeable DC 12 V/22Ah lead batteries, mainly used to drive the motors and operate the circuit board.

Dynamics and properties

The equations of the dynamic model of the robot are obtained using the Lagrange equation. The proposed control system of the humanoid robotic manipulator considers the effects of joint friction and unknown external disturbances. Thus, the complete dynamic model25 is as follows:

where, \(q,\dot {q},\ddot {q} \in {\Re ^n}\) are the angle, the angular velocity, and the angular acceleration of the joints, respectively,\({\varvec{M}}(q) \in {\Re ^{n \times n}}\) is the symmetric positive definite inertia matrix,\({\varvec{C}}(q,\dot {q}) \in {\Re ^{n \times n}}\)is the Coriolis matrix,\({\varvec{G}}(q) \in {\Re ^n}\) is the gravity force, and \({\mathbf{F}}(\dot {q}) \in {\Re ^n}\) is the joint friction.\(d \in {\Re ^n}\)is the external disturbance with an upper bound \(\left\| d \right\| \le d_{\text{M}}\), with \(d_{\text{M}}\) denoting a well-known positive constant, \(\left\| {} \right\|\) is the standard Euclidean norm, and \(\tau \in {\Re ^n}\) represents the joint torque vector. This dynamic model has the following properties26.

Property 1

The inertia matrix \({\varvec{M}}(q)\) is a symmetric positive definite matrix. There exist positive constants \({m_{\hbox{min} }}\),\({m_{\hbox{max} }}\)that satisfy the following inequality holds:

Property 2

\(\dot {\textbf{M}}{(}q\user2{)} - {2}{\textbf{C}}{(}q{,}\dot q2{)}\) is a skew-symmetric matrix.

Assumption 1

The mass and length of the target gripped by the humanoid robotic manipulator are limited. Therefore, the inertia matrix\({\varvec{M}}\varvec{(}q\varvec{)}\), the Coriolis matrix \({\textbf{C}}(q,\dot {q})\) , and the gravity force\({\varvec{G}}\varvec{(}q\varvec{)}\) are bounded.

where, \({{\varvec{M}}_\text{m}}\),\({{\varvec{M}}_\text{M}}\),\({{\varvec{C}}_\text{M}}\)and \({{\varvec{G}}_M}\) are some well-known positive constants.

Assumption 2

Treat joint friction \({\mathbf{F}}(\dot {q}) \in {\Re ^n}\) and external disturbance\(d \in {\Re ^n}\)are considered compound disturbance\(\rho\). It is Assumed that the derivative of the compound disturbance is unknown but in a bounded interval:

By multiplying both sides of Eq. (1) by\({\varvec{M}}_{{}}^{{ - 1}}(q)\) and solving for\(\ddot {q}\), one obtains:

For manipulator models with compound disturbances and parametric uncertainties, we propose a sliding-mode robust controller using RBFNNs. This approach combines global approximation and a NDO to ensure asymptotic convergence of sliding surfaces and tracking errors to zero. The position tracking error \(e(t) \in {\Re ^n}\) represents the difference between the actual joint angle q and the desired joint angle \(q_{d}\) (i.e., the deviation between actual and ideal motion).

Given the desired joint position\({q_d}\), few studies have addressed trajectory tracking control for multi-degree-of-freedom (DOF) robotic manipulators. However, their industrial applications have grown rapidly in recent years. As the deployment of these systems expands, solving trajectory tracking optimization and tracking error convergence challenges becomes critical. Therefore, developing advanced control strategies to enhance trajectory-tracking performance is essential.

Adaptive iterative optimization for kinematic solution

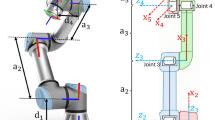

The kinematic model of humanoid robotic manipulators is inherently highly nonlinear and coupled. As illustrated in Fig. 2, these manipulators replicate human physiological structures. Due to their anthropomorphic design, they often violate the criterion of Pieper, making traditional geometric, algebraic, and iterative algorithms ineffective for solving inverse kinematics.

To address this, an improved gradient descent method is proposed, with its core iterative formula derived as follows:

The objective cost function is defined as the difference between the desired and actual poses:

The objective cost function is defined as the difference between the desired and actual poses:

where,\({X_{target}}\) and \(X=f(\theta )\) are the desired and actual poses, respectively. The Jacobian matrix represents the mapping relationship between joint and terminal pose velocity:

Based on the target cost function in Eq. (8) and the Jacobian matrix in Eq. (9), the basic iterative formula of inverse kinematics is derived:

The standard gradient descent method exhibits limitations such as tortuous optimization paths, slow convergence rates, and susceptibility to local minima. To overcome these, a momentum term is introduced into the framework:

where, \(p{v_{t - 1}}\) is the upper time gradient,\(\alpha\) is the learning rate, and p is the attenuation factor.

To further improve calculation accuracy, a second-order momentum term is introduced:

where, \(r_{t}\)is the second-order momentum (exponentially weighted moving average of squared gradients). Incorporating this into the iterative update rule, the proposed IGDIK control module is formulated as:

Among them, σ is a small constant to stabilize numerical calculations and avoid division by zero.

IGDIK control module

Equation (13) integrates first-order and second-order momentum terms to optimize the inverse kinematics solution process, with its core mechanism as follows:

First-order momentum (\(pv_{{\user2{t - 1}}}\)): This term introduces historical gradient information, forming a weighted sum of past update directions. As illustrated in Fig. 3, it enables the algorithm to maintain “inertia” during iteration, overcoming local optima by continuing the search in regions where the objective function value may decrease, even when trapped in suboptimal points. In areas with consistent historical gradient directions, it accelerates convergence, reducing the time required for inverse kinematics solving.

Second-order momentum (\(\sqrt {r_{t} + \sigma }\)): This term quantifies the scale of historical gradient magnitudes, dynamically adjusting the effective learning rate \(a\). When gradients exhibit high volatility (large rt), the denominator increases, reducing the step size to facilitate fine-grained exploration of the solution space. Conversely, when gradients are stable (small rt), the denominator decreases, increasing the step size to accelerate convergence toward the global optimum.

The improved gradient descent algorithm flow is shown in Fig. 4. This mechanism ensures the algorithm balances solution accuracy and convergence speed, effectively addressing the limitations of traditional gradient descent methods and enabling efficient inverse kinematics solving for non-Pieper humanoid manipulators.

To validate the effectiveness of the improved gradient descent method, it is compared with an advanced gradient descent method based on gradient normalization27. Table 1; Fig. 5 present the root mean square error (RMS) and trajectory error curves of the two methods in the inverse kinematics solution of a 6-DOF humanoid manipulator.

In Fig. 5a, the trajectory error of the improved gradient descent method remains consistently at the 10−10 m order of magnitude, with a fluctuation range smaller than 3.3799 × 10− 10m, demonstrating excellent convergence stability and no local optimum trap issue. In Fig. 5b, although the gradient normalization method alleviates gradient oscillation through gradient norm scaling, the absence of a second-order momentum adaptive mechanism leads to error fluctuations reaching the10− 8m order of magnitude.

Design of the control strategy

RBFNN design for SMC

In practical applications, the dynamic model of the humanoid robotic manipulator varies concurrently with payload variations, which inevitably affects the performance of the control strategy. To surmount this challenge, this paper employs the RBFNN28 to estimate the parameters of the robotic manipulator model, as depicted in Fig. 6. Considering the dynamic model in Eq. (1) and the tracking error equation in Eq. (7), the following sliding variables are defined:

where, \({\varvec{\varLambda}}= [\begin{array}{*{20}c} {\lambda_{{1}} } & {\lambda_{{2}} } & \cdots & {\lambda_{n} } \\ \end{array} ]^{T} \in \Re^{n}\). Its selection needs to satisfy that \({s^{n - 1}}+{\lambda _{n - 1}}{s^{n - 2}}+ \cdots +{\lambda _1}\) is Hurwitz polynomial (when\(r \to 0\), then,\(e \to 0\)). From Eq. (14), we obtain:

and

Among them, \(f(x)={\mathbf{M}}({\ddot {q}_d}+\Lambda \dot {e})+{\mathbf{C}}({\dot {q}_d}+\Lambda e)+{\mathbf{G}}+{\mathbf{F}}\) is the dynamic model that needs to be approximated,\({\mathbf{M}}\),\({\mathbf{C}}\) and \({\mathbf{G}}\) are abbreviations for matrices \({\mathbf{M}}(q)\),\({\mathbf{C}}(q,q)\), and \({\mathbf{G}}(q)\), respectively.

In practical applications, the model uncertainty term \(f(x)\) is unknown, so RBFNN needs to approximate\(f(x)\), and its RBFNN structure is presented in Fig. 6.

In Fig. 7, \(x={[e_{{}}^{{\text{T}}},{\dot {e}^{\text{T}}},q_{{\text{d}}}^{{\text{T}}},\dot {q}_{{\text{d}}}^{{\text{T}}},\ddot {q}_{{\text{d}}}^{{\text{T}}}]^\text{T}}\) is the neural network input vector, m, and k are the number of input and hidden layer nodes, respectively. The radial basis function in RBFNN uses the Gaussian basis function, expressed as follows:

where,\({h_j}(x)\)is the nonlinear activation function of the jth hidden node, \({b_j}\)is the basis width of the jth Gaussian basis function, \({c_j}\)is the Gaussian basis function center vector of the jth node, and \(\left\| {x - c_{j} } \right\|^{2}\) is the Euclidean distance between \(x\)and \(c_{j}\).

The RBFNN output is defined as follows:

where, \(\tilde {\textbf{W}} = {\textbf{W}} - {\hat {\textbf{W}}},{\left\| {\textbf{W}} \right\|_F} \leqslant {{\textbf{W}}_{\max }}\).

Then, the designed control law is:

where, \(\hat {f}(x)\) is the estimated value of\(f(x)\) using RBFNN.

Inserting the control law in Eq. (19) into Eq. (16) provides:

The Lyapunov function is established as:

then,

Therefore, under the condition that Kv is a constant value, the stability of the control system depends on the approximation accuracy of \(\tilde {f}\) to f and the size of external disturbance\({\tau _d}\). Since the external disturbance \({\tau _d}\) is uncertain, the control law must be further improved to ensure the stability of the system.

RBFNN design for sliding mode robust control

This section proposes a robust sliding mode controller that operates without requiring precise model knowledge. The ideal RBFNN output is defined as:

where, \({\varvec{W}}^{{\varvec{T}}}\)is the weight of the neural network, φ(x) is the Gaussian function.

For the dynamic model in Eq. (1), the control law is designed as:

where, \(v= - ({\varepsilon _N}+{b_d})\operatorname{s} {\text{i}}gn(r)\) is a robust term used to overcome approximation errors in neural networks29,30,31,32.

Placing the control law of Eq. (24) into Eq. (16), we have:

where, \({\zeta _1}={\tilde {W}^T}{\mathbf{\varphi }}\left( x \right)+(\varepsilon +{\tau _d})+v\).

Define Lyapunov function:

where, tr(.) is the trace of the matrix. The trace of a matrix is the sum of its eigenvalues, by seeking differentiation, we can obtain:

By substituting Eq. (25) into the above equation, we can obtain:

According to Eq. (28) above, in order to make the control system asymptotically stable (\(\mathop V\limits^{.} \leqslant 0\)), it is necessary to take:

The adaptive law for updating weights in RBFNN is:

We can obtain

By substituting the robust term \(\mathop {v= - ({\varepsilon _{N}}+{b_{d}})sign(r)}\limits^{.}\) into Eq. (31), we can obtain:

Among them, \(\left\| \varepsilon \right\| \leqslant {\varepsilon _\text{N}}\),\(\|{\tau _{d}}\| \leqslant {\tau _{{dN}}}\).Therefore, if \(\mathop V\limits^{.} \leqslant 0\) can be ensured, the control system will gradually stabilize. Equation (25) infers that the model uncertainty term \(f(x)\) can be described as:

where, \({{\mathbf{\xi }}_1}(t)={\ddot {q}_d}+\Lambda \dot {e}, {{\mathbf{\xi }}_2}(t)={\dot {q}_d}+\Lambda e\).

RBFNN can be used to approximate and calculate the terms in \(f(x)\) separately:

then,

where, \({{\mathbf{\varphi }}_0}(x)=\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{{\mathbf{\varphi }}_{\text{M}}}} \\ {{{\mathbf{\varphi }}_{\text{V}}}} \\ {{{\mathbf{\varphi }}_\psi }} \\ {{{\mathbf{\varphi }}_{\text{F}}}} \end{array}} \right],{{\mathbf{W}}^{\text{T}}}=\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\mathbf{W}}_{{\text{M}}}^{{\text{T}}}}&{{\mathbf{W}}_{{\text{V}}}^{{\text{T}}}}&{{\mathbf{W}}_{{\text{G}}}^{{\text{T}}}} \end{array}} \right]\).

The adaptive law is defined as:

where, \({k_\text{M}}>0,{k_\text{v}}>0,{k_\text{G}}>0,{k_\text{F}}>0\).

Considering the adaptive law, the Lyapunov function is redefined as:

then,

Placing the control law of Eq. (24) in Eq. (38) provides:

Considering the characteristics of the humanoid robotic manipulator and substituting the adaptive law of Eq. (36) into Eq. (39), we get:

Because of

Considering the robust term\(v= - ({\varepsilon _N}+{b_d})sign(s)\), we get:

Because of

For\(\dot {{\varvec{L}}}<0\), we need

or \({\left\| {{{\tilde {{\varvec{W}}}}_\text{M}}} \right\|_\text{F}}>{{\varvec{W}}_{\text{M}\hbox{max} }}\), \({\left\| {{{\tilde {{\varvec{W}}}}_\text{V}}} \right\|_\text{F}}>{{\varvec{W}}_{\text{V}\hbox{max} }}\)and\({\left\| {{{\tilde {{\varvec{W}}}}_\text{G}}} \right\|_\text{F}}>{{\varvec{W}}_{\text{G}\hbox{max} }}\).

When faced with unknown dynamics and compound model uncertainties, RBFNN is employed to approximate uncertain system dynamics. Leveraging SMC principles, this paper proposes a robust controller that operates independently of precise model information. The SMC law is designed to compensate for both approximation errors and external disturbances through adaptive control gains, ensuring closed-loop stability under Lyapunov analysis.

Nonlinear disturbance observer

The control system of the Seed Noid R7F humanoid robotic manipulator must consider unknown external disturbances and the effect of joint friction, which, according to Eq. (5), are regarded as compound disturbances. By using a NDO4 to estimate compound disturbances, the calculated values are fed back to the input to adjust the control torque, reducing the impact of compound disturbances on the humanoid robotic manipulator control system and demonstrating anti-disturbance solid performance. The kinetic equation for the compound disturbance \(\rho\) is described as follows:

According to Assumption 2 in Sect. 2, the compound disturbance Eq. (5) is bounded, and thus, the NDO equation is written as:

where, \(\hat {\rho }\)is the estimated compound disturbance from the NDO and \({\mathbf{L}}(q,\dot {q})\)is the gain matrix. Since it is challenging to obtain the joint angular acceleration signal in practical applications, this signal should not be used when designing a NDO and the auxiliary parameter vector must be defined as:

where, \(p(q,\dot {q})\) is the function vector that must be designed. Then,\(p(q,\dot {q})\) and \({\mathbf{L}}(q,\dot {q})\) must satisfy the following conditions:

Since \({\mathbf{M}}(q)\) is a positive definite matrix, the matrix \({\mathbf{L}}(q,\dot {q})\) can be made positive definite by designing an appropriate\(p(q,\dot {q})\). Taking the derivative of \(z\) provides:

To sum up, the NDO is written as:

then, the general control equation of the humanoid robotic manipulator system can be written as follows:

Let the estimation error of the NDO be \(e=\rho - \hat {\rho }\). Assuming that the change of the compound disturbance is slow, i.e., \(\rho =0\), we have:

The Lyapunov function is defined as\({V_\rho }=\frac{1}{2}e_{\rho }^{\text{T}}{e_\rho }\), and thus:

Since \({\varvec{L}}(q,\dot {q})\) is a positive definite matrix,\({\dot {V}_\rho } \leqslant 0\), and the observation error of the NDO converges asymptotically.

A NDO is designed to estimate and attenuate unknown external disturbances in the dynamic model of a nursing robot, specifically addressing nonlinear joint friction effects. By integrating the NDO output with the SMC input, a closed-loop control architecture is constructed to compensate for both parametric uncertainties and external perturbations, thereby ensuring robust tracking performance under Lyapunov stability theory.

This study presents an integrated control framework combining RBFNN, sliding-mode robust control, and NDO. The RBFNN provides global approximation of parametric uncertainties for adaptive parameter estimation, while sliding-mode control ensures robustness through sliding variable design. The NDO compensates for external disturbances and unmodeled dynamics, guaranteeing closed-loop stability under Lyapunov analysis. This synergetic architecture effectively addresses dynamic variations in 6-DOF humanoid manipulators operating in complex environments, offering a robust control solution for trajectory tracking applications.

Simulation and result analysis

An evaluation of the proposed sliding-mode robust control strategy, which integrates a RBFNN with global approximation capabilities and a NDO, is conducted on a 6-DOF humanoid robotic manipulator, specifically the Seed Noid R7F nursing service robot. This robotic manipulator consists of six rotating joints, offering a greater number of joint configurations during movement, thereby enhancing its flexibility and trajectory diversity.

In this study, the right arm of the robot is selected as the modeling object. The D-H parameters are presented in Table 2, and the comprehensive physical parameters of the humanoid robotic manipulator are listed in Table 3.

The control strategy for the humanoid robotic manipulator system is developed in MATLAB/Simulink. Spiral trajectories are used as the reference paths for the robot in Cartesian space. The pose angle of the robot is represented by Euler angles following the Z-Y-X sequence, which correspond to the rotation angles about the Z, Y, and X axes, respectively.

The spiral lines are xd = 0.02cos(πt) + 0.1, yd = 0.02sin(πt) + 0.1, zd = 0.05t + 0.1. The pose angle is a constant value, where roll, pitch, and yaw are 45 °, 60 °, and 30 °, respectively. The sliding mode surface parameter is\(\Lambda =15\). The basis function center is c = [− 1 − 0.8 − 0.6 − 0.4 − 0.2 0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1] and the basis function width is b = 20. For the weight adaptive law coefficient matrix,\(F\_M\), \(F\_C\), and \(F\_G\) are assigned a value of 100. In response to the influence of unknown external disturbances and joint friction in the control system of the 6-DOF humanoid robotic manipulator, this study considers the unknown external disturbances and joint friction as composite disturbances. Simulated experiment applying composite interference. Joint friction is the sum of Coulomb friction and viscous friction \({\mathbf{F}}(\dot {q})=2sign(\dot {q})+0.8\dot {q}\). The external disturbance is given to six joints \({\tau _d}=0.8\sin (t)\), respectively.

The robust parameters of this article are selected as 0.5, 1.5, 2.1, and 3, and the position error comparison chart is shown in Fig. 8.

The number of hidden layer neurons in RBFNN directly impacts dynamic model robustness. We evaluated 5, 8, 11, and 14 hidden units for robustness analysis, with results presented in Fig. 9.

The design parameters of the nonlinear disturbance observer are \(\user2{p(q,\dot{q}) = cc[\dot{q}}_{{\varvec{1}}} \user2{,\dot{q}}_{{\varvec{2}}} \user2{,\dot{q}}_{{\varvec{3}}} \user2{,\dot{q}}_{{\varvec{4}}} \user2{,\dot{q}}_{{\varvec{5}}} \user2{,\dot{q}}_{{\varvec{6}}} \user2{]}^{{\varvec{T}}}\) and \({\mathbf{L}}(q,\dot {q})={\text{cc}}{{\mathbf{M}}^{ - 1}}\), where \({\varvec{cc}}\)is selected as 10, 20, 60, 100, and 120. The disturbance errors under different parameters are compared, as shown in Fig. 10.

Finally, the design parameters of the NDO are: \(p(q,\dot {q})=60{[{\dot {q}_1},{\dot {q}_2},{\dot {q}_3},{\dot {q}_4},{\dot {q}_5},{\dot {q}_6}]^\text{T}}\)and\({\mathbf{L}}(q,\dot {q})=60{{\mathbf{M}}^{ - 1}}\). The RBFNN involves 11 hidden layer nodes.\({\varepsilon _N}=2\) and \({b_d}=0.1\) in robust term.

The inverse kinematics solution maps Cartesian space coordinates to joint space, generating desired joint angle trajectories. The proposed control strategy is then applied to achieve trajectory tracking in joint space. Finally, forward kinematics computations reconstruct the Cartesian space trajectory from the tracked joint angles.

Digital simulation results

Figures 11 and 12 present Cartesian space trajectory tracking results of the proposed RBFNN- SMC strategy, demonstrating high-precision convergence between actual and desired trajectories.

The inverse kinematics solution maps Cartesian space trajectories to joint space, generating expected joint angle trajectories. Figure 13 presents attitude angle results in Cartesian space, while Figs. 14 and 15 illustrate joint position and velocity profiles in joint space. These results demonstrate that the proposed control strategy achieves high-precision tracking of spiral trajectories, validating its reliability for complex trajectory tasks.

The fitting results of RBFNN based on the overall approximation of the model are illustrated in Fig. 16.

Take the uncertain terms of the model as:\({\varvec{M}}={\varvec{M}}+0.5{\varvec{M}}\); \({\varvec{C}}={\varvec{C}}+0.5{\varvec{C}}\); \({\varvec{G}}={\varvec{G}}+0.5{\varvec{G}}\). With the introduction of model uncertainty, the RBFNN-based approximation converges to the actual dynamics, demonstrating robust control performance under parametric variations. Figure 17 compares the dynamic model fitting results before and after uncertainty injection, verifying the effectiveness of the RBFNN in approximating uncertain system dynamics.

Figure 18 shows the joint torque diagram, indicating that after effectively handling the uncertain influencing factors of the control system, the torque jitter phenomenon is significantly reduced.

The composite interference results are estimated using a disturbance observer, as depicted in Fig. 19. It reveals that after the response, the matrix norm of the fitted model \({f_N}(x)\) is almost identical to the actual model\(f(x)\), and the error is within an acceptable range.

At \(\user2{t = 2s}\), a step interference signal with amplitude of 10 N is applied to the end effector. As depicted in Fig. 20, the NDO demonstrates the ability to precisely estimate step interference signals.

RBFNN have demonstrated superior performance in dynamic modeling applications. Specifically, RBFNN exhibits robust fitting capabilities for nonlinear system dynamics, accurately capturing complex model characteristics. Under parametric uncertainty, RBFNN-based approximations asymptotically converge to true system dynamics, preserving control robustness and ensuring stable operation in uncertain environments. When subjected to composite disturbances, the RBFNN-identified model maintains close approximation to actual dynamics, showcasing excellent disturbance rejection properties. Furthermore, the proposed framework demonstrates favorable control performance under step disturbances, effectively mitigating perturbations and validating system robustness.

Comparative analysis of the results

Comparative analysis between the proposed control framework and alternative strategies is presented in Figs. 21 and 22. For the 6-DOF humanoid manipulator trajectory tracking task, Cartesian space position errors are compared between actual and target trajectories. Quantitative results demonstrate statistically significant improvements in tracking performance through adaptive parameter tuning. Specifically, Figs. 21 and 22 reveal that the RBF + NDO and FA-SMC strategies outperform other methods in both control accuracy and disturbance rejection. While FA-SMC exhibits larger Z-axis errors at initial transient phases, PD + NDO demonstrates lower tracking accuracy, and SMC + NDO experiences error oscillations under uncertainty, indicating reduced robustness. Key performance metrics are summarized in Table 4, including RMSE and maximum deviation values.

As manifested in Table 4, the devised sliding mode robust control strategy, which employs the RBFNN predicated on model global approximation and a NDO, demonstrates excellent performance in the trajectory tracking control of the humanoid robotic manipulator. In contrast to conventional control strategies, this control approach attains enhanced anti-interference capabilities and superior control accuracy.

Virtual simulation results

The Linux/Ubuntu20.04 system uses the Noetic version of the ROS simulation platform, which is combined with the Moveit library for the experiments. First, one must obtain the URDF file officially provided by the robot and then import the Seed Noid R7F humanoid robotic manipulator into the system for trajectory tracking experiments. The path trajectories are automatically generated by Moveit, and the tracking experiments are carried out through the employment of the robust RBFNN-SMC founded on global approximation. With the initial position of the box being (0, 3, -0.2, 0, 0.775), the robotic manipulator is set to transition from its initial state to the initial position of the crate and subsequently to the target position of the box, which is (0, 5, -0.4, 1, 1.055). The manner in which the robotic manipulator is moved from the initial state to the initial position of the box is illustrated in Fig. 23. The movement state of the trajectory of the robotic manipulator from the initial point of the box to its target point is portrayed in Fig. 24. The final state of the robotic manipulator is presented in Fig. 25.

Figures 24 and 25 demonstrate smooth, stable, and precise target object grasping at desired positions using the proposed RBFNN-SMC strategy. Figures 26, 27 and 28, and 29 reveal that the robot can smoothly, stably, and accurately grasp the target object at the desired position in the ROS simulation platform using the proposed control strategy. During experiments, extensive sensor data were collected for key parameters including joint angles, accelerations, torques, and end-effector trajectory states. Data analysis reveals that the control strategy maintains excellent tracking performance and robust disturbance rejection under compound uncertainties (model uncertainty, external unknown disturbances, and joint friction), ensuring closed-loop stability and precision control.

Experimental process and result analysis

The experiment uses the Seed Noid R7F robot manipulator with six rotary joints. The maximum load capacity of the manipulator is 2 kg, the loaded manipulator contains three fingers, and the maximum holding force is 150 N, capable of performing various complex movements. The robot is controlled in real-time on the PC side of the ROS operating system.

The experimental platform uses the KDL (Kinematics and Dynamics Library) solver. The target object is a box of milk. Upon the generation of the trajectory via KDL, the trajectory tracking experiment is carried out by employing the sliding mode robust control strategy, which incorporates the RBFNN founded on the proposed global approximation and NDO.

Figure 30 presents the experimental status of the Seed Noid R7F robot. In the phases illustrated by (a)-(d), the robot executes a displacement from the initial pose to the pose of the box. Subsequently, during the intervals depicted in (e)-(h), the robot undertakes the task of grasping the box and transporting it to the target pose.

It is a long process for the Seed Noid R7F robot to perform the above gripping tasks and requires much computing time. Therefore, due to the substantial computational overhead of the trajectory tracking and the complex trajectories, the execution time is extended. Nevertheless, the experimental outcomes indicate that the Seed Noid R7F robot is capable of accomplishing the grasping action successfully with the employment of the proposed controller. Although friction interference and hardware circuit response delay the grasping process of the robotic manipulator, the grasping trajectory action is accurate, as illustrated in Fig. 31. This control strategy has good control performance and strong anti-interference ability.

Conclusion

The present paper tackles the problems concerning model uncertainty, joint friction, and unknown external disturbances that are associated with the 6-DOF humanoid robotic manipulator. Specifically, this study proposes a sliding mode robust control strategy with the RBFNN based on model global approximation and NDO by using the RBFNN to approximate the whole dynamic model and applying the weight adaptive law to adjust the dynamic model parameters online. The developed strategy can effectively reconstruct the dynamic model. Additionally, the NDO conducts real-time monitoring of the unknown external disturbances and joint friction, and further compensates within the control strategy to mitigate the influence exerted by these factors. Simulation and experimental results in MATLAB/Simulink and ROS environments demonstrate that compared with control approaches such as SMC + NDO and PD + NDO, the proposed controller exhibits remarkably smaller fluctuations across all axes, maintaining closer adherence to the ideal trajectory. Mean square deviation data further reveals that the RBF + NDO controller achieves the minimum values for the x, y, and z axes-5.01 × 10− 5m, 4.45 × 10− 5m, and 1.39 × 10− 5m, respectively. Notably, the x-axis value is merely 29.3% of the SMC + NDO method (1.71 × 10− 5m). These quantitative comparisons and trajectory analyses collectively validate the prominent advantages of the RBF + NDO method in trajectory tracking accuracy and stability.

Nevertheless, in practical implementation, the 6-DOF humanoid robotic manipulator is expected to accommodate various scenarios. Owing to the structural constraints of the robotic manipulator, the current study was confined to conducting trajectory tracking control under a fixed attitude. Future research efforts should be directed towards trajectory tracking control investigations that involve dynamically adjusting the attitude angles in accordance with task demands.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Y. Y.

Abbreviations

- \(q\) :

-

Joint angles

- \(\tau\) :

-

Joint torque vector

- \(d\) :

-

External disturbances

- \({\varvec{F}}(q)\) :

-

Joint friction

- \(e\) :

-

Position tracking error

- \(pv_{t - 1}\) :

-

The upper limit of the time gradient

- \(\alpha\) :

-

Learning rate

- \(p\) :

-

Attenuation factor

- \(r\) :

-

Sliding variables

- \(h_{j} (x)\) :

-

The nonlinear activation function of the jth hidden node

- \(b_{j}\) :

-

Base width

- \(c_{j}\) :

-

The center vector of the Gaussian function of the j-th node

- \({\varvec{M}}(q)\) :

-

The symmetric positive definite inertia matrix

- \({\varvec{C}}(q,\dot{q})\) :

-

The Coriolis matrix

- \({\varvec{G}}\) :

-

The gravity force

- \({\varvec{F}}(\dot{q})\) :

-

The joint friction

- \(\rho\) :

-

Compound disturbance

- \(m\) :

-

The number of input

- \(k\) :

-

The number of hidden layer nodes

- \(\phi (x)\) :

-

The Gaussian function

- \({\varvec{L}}(q,\dot{q})\) :

-

The gain matrix

- \(\hat{w}\) :

-

The weight of the neural network

- \(\hat{\rho }\) :

-

Composite interference

References

Dereli, S. & Köker, R. A meta-heuristic proposal for inverse kinematics solution of 7-DOF serial robotic manipulator: quantum behaved particle swarm algorithm. Artif. Intell. Rev. 53, 949–964 (2020).

Bai, Y. & Hsieh, S. J. A hybrid method using FABRIK and custom ANN in solving inverse kinematic for generic serial robot manipulator. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 130, 4883–4904 (2024).

Zhou, X. et al. An improved inverse kinematics solution for 6-DOF robot manipulators with offset wrists. Published online by Cambridge University Press: 14 January (2022).

Ames, B., Morgan, J. & Konidaris, G. Ikflow: generating diverse inverse kinematics solutions. IEEE Rob. Autom. Lett. 7(3) (2022).

Gao, R. Inverse kinematics solution of Robotics based on neural network algorithms. J. Ambient Intell. Hum. Comput. 11, 6199–6209 (2021).

Yin, X., Pan, L. & Cai, S. Robust adaptive fuzzy sliding mode trajectory tracking control for serial robotic manipulators. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 72, 101884 (2021).

Tran, T. & Ahn, K. K. Adaptive nonsingular fast terminal sliding mode control of robotic manipulator based neural network approach. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 22, 417–429 (2021).

Yin, H. et al. Kinematic control of humanoid upper body robot using virtual flexible joint dynamics primitive and Quasi-Sliding mode Observer[J]. IEEE Trans. Industrial Electron. (2025).

Xiao, B., Cao, L., Xu, S. & Liu, L. Robust tracking control of robot manipulators with actuator faults and joint velocity measurement uncertainty. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 25, 1354–1365 (2020).

Zhu, D., Du, B., Zhu, P. & Wu, W. Adaptive backstepping sliding mode control of trajectory tracking for robotic manipulators. Complexity 2020, 1–11 (2020).

Su, Y. & Zheng, C. A new nonsingular integral terminal sliding mode control for robot manipulators. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 51, 1418–1428 (2020).

Song, T., Fang, L. & Zhang, Y. Nonsingular Fast Terminal Sliding Mode Control Based on a Novel Nonlinear Disturbance Observer for Robotic Systems [J] (Asian Journal of Control, 2025).

He, W., Huang, H. & Ge, S. Adaptive neural network control of a robotic manipulator with Time-Varying output constraints. IEEE Trans. Cybernetics. 47, 3136–3147 (2017).

Liu, Q. et al. Adaptive bias RBF neural network control for a robotic manipulator. Neurocomputing 447, 213–223 (2021).

Stoffel, M., Gulakala, R., Bamer, F. & Markert, B. Artificial neural networks in structural dynamics: A new modular radial basis function approach vs. convolutional and feedforward topologies. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 364 (Issue), 112989–112989 (2020).

Narayan, J. & Dwivedy, S. K. Adaptive Control of a Pediatric Gait Exoskeleton: Integrating RBF Neural Network with Non-Singular Fast Terminal Sliding Mode Scheme. In 10th International Conference on Control, Decision and Information Technologies (CoDIT). (2024).

Xin, Z. & Ying, Q. Fuzzy sliding mode control of manipulator based on disturbance observer and RBF neural network. Autom. Control Comput. Sci. 57, 123–134 (2023).

Sun, X., Zhang, L. & Gu, J. Neural-network based adaptive sliding mode control for Takagi-Sugeno fuzzy systems. Inf. Sci. 628, 240–253 (2023).

Li, H., Hu, X., Zhang, X., Chen, H. & Li, Y. Adaptive radial basis function neural network sliding mode control of robot manipulator based on improved genetic algorithm. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 37 (8), 1025–1039 (2024).

Viet–Thanh & Nguyen Bao–Long Pham, Thi–Van–Anh Nguyen, Ngoc–Tam Bui, Quy–Thinh Dao. Sliding mode control of antagonistically coupled pneumatic artificial muscles using radial basis neural network function. SN Appl. Sci. 5, 246 (2023).

Sun, H., Huang, L. & He, L. Research on the trajectory tracking control of a 6-DOF manipulator based on Fully-Actuated system models. J. Syst. Sci. Complexity. 35, 641–659 (2022).

Chen, Z., Zhang, Y., Nie, Y., Tang, J. & Zhu, S. Adaptive sliding mode control design for nonlinear unmanned surface vessel using RBFNN and Disturbance-Observer. IEEE Access. 8, 45457–45467 (2020).

Narayan, J., Abbas, M., Patel, B. & Dwivedy, S. K. Adaptive RBF neural network-computed torque control for a pediatric gait exoskeleton system. Intell. Serv. Robot. 16, 549–564(2023).

Liu, Y. et al. A novel trajectory tracking control approach for uncertain 6-DOF manipulators based on fuzzy sliding mode of radial basis function neural network. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part I J. Syst. Control Eng. 237(6), 1032–1044 (2023).

Liu, Z., Wang, Y., Yang, J. & Shi, J. In Robotics and Rehabilitation Intelligence: First International Conference, ICRRI Fushun, China, September 9–11, 2020, Proceedings, Part I 1. 64–82 (Springer). (2020).

Yu, J. Y. Trajectory Tracking Based on Neural Network Sliding Mode controller[J] (Authorea Preprints, 2023).

Roy, S. & Roy, S. B. Kar, I. N. Adaptive–robust control of Euler–Lagrange systems with linearly parametrizable uncertainty bound. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 26, 1842–1850 (2017).

Jian, Z., Hanqing, S., Jinzhu, Z., Tao, W. & Qingxue, H. Solving the inverse kinematics of A series robotic arm based on gradient descent. Modular Mach. Tool Automatic Manuf. Technique 11, 78–82 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Qiu, M. & Gao, H. In IJCAI Thirty-Second International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence. 4602–4610 (2023).

Yu, J., Wu, M., Ji, J. C. & Yang, W. Neural Network-Based region tracking control for a Flexible-Joint robot manipulator. J. Comput. Nonlinear Dyn. 19, 1–12 (2024).

Yang, J., Zhou, Z. & Ji, J. Nonlinear integral sliding mode control with adaptive extreme learning machine and robust control term for Anti-External disturbance robotic manipulator. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 48, 2375–2397 (2023).

Xi, R., Xiao, X., Ma, T. & Yang, Z. X. Adaptive sliding mode disturbance observer based robust control for robot manipulators towards assembly assistance. IEEE Rob. Autom. Lett. 7, 1–1 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The conceptualization was carried out by Y.W., Y.Y. and L.J. The methodology was developed by Y.W., Y.Y., and J.Y. The journals were reviewed by Z.W., S.W. and L.J. The software was designed and implemented by Y.Y., Z.W., and L.J. The verification process was conducted by Y.Y. and L.J. The overall supervision was overseen by Y.W. All authors have thoroughly read and consented to the final published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Yu, Y., Wang, Z. et al. Tracking control of humanoid manipulator using sliding mode with neural network and disturbance observer. Sci Rep 15, 38980 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22825-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22825-2