Abstract

Despite a growing body of literature on school engagement and burnout, little is known about how these constructs jointly vary in response to socioemotional skills and phone dependency. This study examined how socioemotional skills and phone dependency predict engagement-burnout profiles among primary school students (N = 615; 47% female; Mage = 9.69, SDage = 0.79). The dimensions of school engagement and burnout were examined as indicators of the latent profiles. The OECD socioemotional skills framework (curiosity, grit, social engagement, belongingness, and academic buoyancy) and phone dependency were examined as predictors of profile membership. Latent profile analysis identified three distinct profiles: (1) a moderately burned-out group (36.1%); (2) a highly burned-out and moderately engaged group (10.9%); and (3) a highly engaged group (53%). Follow-up logistic regression analysis revealed that students who reported a higher level of social engagement, buoyancy, and grit were more likely to be engaged than those who were burned out. In contrast, students who felt lonely and curious were more likely to experience burnout. Moreover, those who reported higher levels of phone dependency and left-behind status were more likely to have burnout symptoms. These findings highlight the role of socioemotional skills and phone dependency in understanding student engagement and burnout, with implications for school interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Student engagement and school burnout have been widely recognized as key constructs in understanding students’ academic well-being and success1. School engagement is generally defined as a student’s emotional, behavioral, and cognitive involvement with their educational tasks, which is closely tied to positive academic outcomes such as persistence, achievement, and school satisfaction. In contrast, school burnout refers to feelings of exhaustion, disengagement, and emotional depletion, and has been associated with school dropout, psychological distress, and reduced academic performance2,3,4. While these constructs have been widely studied in older student populations, research on how primary school students experience engagement and burnout, as well as the factors that predict these outcomes, is still limited5,6,7.

Recent educational psychology emphasizes that socioemotional skills (SES) play a pivotal role in shaping students’ ability to engage positively with school demands8,9, and specifically, the role of SES on students’ school engagement and burnout10,11. SES is considered foundational to students’ ability to navigate academic challenges and social interactions, essential for long-term educational success. However, little attention has been given to the prediction power of SES in the context of school engagement and burnout, particularly at the primary school level. This gap needs to be addressed to better understand how socioemotional competencies influence early school experiences and predict various engagement-burnout profiles. Simultaneously, the growing prevalence of phone dependency among children has raised concerns about its potential to undermine engagement and exacerbate burnout12. The increasing use of smartphones and digital technologies can contribute to academic distractions, social isolation, and mental health issues, which may exacerbate burnout and reduce students’ ability to engage meaningfully with schoolwork. While previous research has explored these factors among adolescents and young adults, studies that examine the impact of phone dependency on primary school students remain scarce3.

Although existing studies have explored the complex interactions between school engagement and burnout and phone dependency13,14,15, as well as between mobile phone use and socioemotional skills16, have already been presented in the literature, they are, however, rarely investigated together within the primary school context. Moreover, studies often treated those variables separately, making studies on the complex interplay between student engagement (burnout) patterns and how they were related to phone dependency and socioemotional skills underrepresented. Therefore, the first aim of the present study is to identify distinct latent profiles of school engagement and burnout among primary school students using latent profile analysis (LPA). The second aim is to examine how SES (e.g., curiosity, grit, academic buoyancy) predicts profile membership. Lastly, we explore the associations between phone dependency, demographic variables, and engagement (burnout) profiles. By integrating these constructs within a person-centered framework, this study aims to advance understanding of early academic well-being and provide actionable targets for intervention.

Literature review

Students’ school engagement and burnout

Over the past two decades, studies on student engagement have exploded due to its potential for tackling longstanding educational challenges such as low achievement, high dropout rates, and high rates of student boredom and alienation17,18,19,20. Student engagement has been defined as a student’s dedication to and investment in schooling21, the time and effort students invest in educational activities22, and the positive emotions and learning strategies they employ23. Despite variances in its definition, there appears to be a consensus that engagement is a multifaceted concept that combines behavior, cognition, and emotion18,21. Recently, one study24 extended the concept of work engagement to the school context, defining school engagement from the perspectives of vigor, commitment, and absorption. Within this psychological approach, energy and dedication correspond to high energy and resilience when executing school-related obligations, whereas absorption reflects immersion in academics or interests25. Learning agency and the purposes of vigor, commitment, and absorption should be considered to fully understand student engagement’s complexity.

In contrast, over the past decade, academics have begun to focus on academic burnout due to its role in predicting low educational achievement, student misbehavior, and school dropout20. The concept of school burnout, typically used to explain the phenomenon of burnout that students encounter in school life, consists of three dimensions: exhaustion at school, cynicism, and a sense of inadequacy at school26,27,28. According to Salmela-Aro’s study29, students experience school burnout when they feel emotionally weary (e.g., overburdened by schoolwork), cynical and alienated from their academic interests (e.g., perceiving a loss of significance in learning), or inadequate (e.g., believing their capacities to be lacking). Emotional exhaustion is a more common symptom of a mental disorder than emotional disengagement30. Several factors, including unrealistically high expectations for one’s study, a lack of outlook on one’s abilities, or feelings of inadequacy, may contribute to academic burnout31,32,33.

Although the above definition of burnout is widely cited, it has been criticized for its narrow focus on symptoms rather than underlying processes. To address these limitations, recent research has increasingly adopted the Study Demands-Resources (SD-R) model, an extension of the Job Demands-Resources model to the educational context3,34. The SD-R model provides a more dynamic framework by examining how study demands (e.g., workload, academic pressure) and study resources (e.g., peer support, teacher feedback, personal coping strategies) interact to influence both school engagement and burnout35,36. This model highlights the dual processes of energy depletion and motivational enhancement, providing a more comprehensive understanding of how students simultaneously experience engagement and burnout within their learning environment. As a result, contemporary developmental psychology and educational psychology studies have begun to examine school burnout alongside student engagement19,20,37,38,39. It is vital to concurrently analyze and replicate both the benefits and drawbacks of engagement31, since students with varied backgrounds (e.g., community, school, and family circumstances) may have different levels of engagement and burnout symptoms; in other words, not all engaged students are alike19.

Socioemotional skills among school-aged children

Exploring the social and emotional realm in primary schoolchildren (e.g., socioemotional skills; SES) is a topic of equal interest to psychologists, teachers, and caregivers35. Therefore, SESs have been identified in international organizations such as the OECD, UNESCO, and the EU (European Union)36 and emphasized in countries like the U.S. and the UK’s contemporary education policy and practice39. Numerous terms and theoretical frameworks define and comprehend these abilities. In the economics literature, for instance, “noncognitive skills” are commonly used40, although “character skills” are preferred by some education specialists41. In general, SES is regarded as an umbrella term encompassing many personal characteristics, including personality traits, motivation, preferences, and values. According to Lechner’s study42, SES manifests itself in relatively consistent behavior patterns, cognition, and affect, partly shaped by socialization and learning.

In this article, we use the term “socioemotional skills”, as they are widely used in the psychological literature, and define such skills according to the OECD framework as individual capacities that can manifest consistent patterns of thoughts, emotions, and behaviors36, which have been tested among students in several countries worldwide43. The OECD socioemotional skills framework36 identifies five conceptual domains that encompass key socioemotional competencies: task performance skills (e.g., persistence or grit), emotional regulation skills (e.g., academic buoyancy), open-mindedness skills (e.g., curiosity), collaboration skills (e.g., social engagement), and skills that facilitate engagement with others (e.g., social belongingness or the absence of loneliness)44. These competencies are crucial in students’ emotional development and well-being, influencing their ability to engage positively with academic tasks and navigate social interactions8.

While social engagement and school belongingness are often considered components of school engagement in classical frameworks2, in this study, we adopt Salmela-Aro and Upadyaya’s3,24 definition of school engagement (vigor, dedication, absorption) and treat belongingness and social engagement as socioemotional skills within the OECD framework. This distinction ensures conceptual clarity and avoids overlap between engagement and SES constructs. Distinct socioemotional skills are essential in predicting school engagement and preventing school burnout among adolescents45,46. For example, persistence and grit are associated with higher motivation and academic achievement47, while academic buoyancy reduces the risk of burnout by helping students regulate emotions under stress45. Social skills and belongingness protect against disengagement, whereas loneliness is a known risk factor for burnout8. These findings provide a strong rationale for examining SES as predictors of students’ engagement–burnout profiles in the present study.

A growing body of empirical research has demonstrated the significant role of socioemotional skills in students’ achievement, academic engagement, and personal well-being8,45,48,49,50, and they are essential determinants of various socioeconomic outcomes51. For example, Durlak et al.’s meta-analysis46 of over 270,000 students found that socioemotional learning (SEL) programs in elementary schools significantly improved students’ academic performance, emotional well-being, and classroom behavior. Similarly, socioemotional competencies in early childhood are strong predictors of later academic achievement and even long-term success in life45. Another large-scale study by Caprara et al.52 highlighted that primary school children’s self-regulation, persistence, and emotional control are closely linked to their academic achievement in reading and math. These findings underscore that socioemotional skills are relevant for psychological adjustment and are critical in facilitating learning and cognitive development during primary school.

A substantial body of evidence indicates that socioemotional skills are malleable and can be influenced by various individual and contextual factors10. It tends to develop and change, particularly during adolescence, and has significant consequences for various essential life domains, including personal and academic well-being45. It also serves as a precursor for lifelong adaptation and functioning53. Young adolescents continuously develop these skills through communication and interaction with family, friends, and teachers at home and school. As children grow, they progressively orient themselves toward their peers and increasingly need to develop skills such as negotiating, resolving conflicts, taking another person’s point of view, empathy, and understanding54. In addition, they need to seek more autonomy and develop self-regulatory skills such as persistence, grit, and academic buoyancy that help them avoid risky behaviors in the interest of long-term educational and life goals47. While it is well established that these skills continue to develop during adolescence, current research also emphasizes the critical foundation laid during primary school, where children begin to acquire essential socioemotional competencies through structured learning environments and peer interactions35. For instance, primary school children progressively develop skills such as empathy, perspective-taking, conflict resolution, and emotional regulation, which are foundational for academic success and lifelong adaptation55. These skills also encompass self-regulatory capacities such as persistence, grit, and academic buoyancy, which help them overcome learning challenges and achieve long-term educational goals56.

Moreover, recent studies emphasize that demographic variables significantly shape socioemotional development, particularly students’ grade level and left-behind status. Research indicates that higher graders often encounter increasing academic and social pressures. In contrast, left-behind children may experience emotional and social vulnerabilities due to parental absence, both of which can affect their socioemotional outcomes15,57,58. These insights underscore the necessity of considering environmental and demographic influences when assessing SES. In light of these findings, policymakers worldwide have launched initiatives to cultivate students’ socioemotional skills. For example, the OECD has promoted the Beyond Academic Learning Program. At the same time, national and regional efforts include Energie Jeunes in France, Construye-T in Mexico, KIPP charter schools in the U.S., and the Singapore Positive Education Network49,59,60,61. These programs collectively underscore the global recognition of SES as a foundation for students’ academic and socioemotional development.

Phone dependency among school-aged children

Phone dependency, which is a term sometimes used interchangeably with problematic phone use and phone addiction62,63,64, is defined as compulsive, problematic use marked by impaired control and functional impairments16. Increased phone dependency among school-aged children has raised public concerns65, particularly given that lower socioeconomic status levels, such as poor self-regulation, are associated with problematic digital behaviors66. For example, an existing study has shown that the rate of phone dependency among young children is increasing across North America, Iran, Korea, Switzerland, Spain, and the UK67,68,69,70,71,72,73. Research has indicated that phone dependency is associated with low emotional stability, chronic stress, and depression74. At the same time, awareness of excessive game use and social networking are predictive factors of phone dependency75. Phone dependency is characterized by compulsive and problematic smartphone use patterns, including the inability to manage or limit smartphone use, withdrawal symptoms when suddenly without a smartphone, tolerance to higher levels of usage, and impaired performance76,77. Studies revealed a negative correlation between phone dependency and socioemotional skills78,79. For example, they found that groups with internet dependency are more likely to have social and emotional impairments and spend more hours online daily79. Moreover, the scientific consensus on the health risks of mobile phones for children and adolescents remains vague and inconclusive80. To track these problems, scholars have agreed that deficient self-regulation positively impacts mobile phone use (i.e., increased usage) by promoting impulsive behavior through the lack of self-regulation an individual experiences in various situations66.

To date, existing research has demonstrated that phone dependency, defined as a compulsive and problematic pattern of smartphone use characterized by excessive time spent, impaired control, withdrawal symptoms, and functional impairments, is associated with a range of adverse psychological and academic outcomes, such as depression and academic burnout among adolescents16,77. Prior studies have also explored the connections between dependency and burnout81. Although much of the literature focuses on adolescents and young adults, recent studies have begun to investigate these patterns among primary school children. For instance, lower levels of socioemotional skills, particularly self-regulation and emotional control, are associated with increased phone dependency among school-aged children82. Similarly, research highlighted that deficiencies in socioemotional competencies can predict problematic smartphone use, even in younger populations83. Thus, while earlier literature often emphasized Internet addiction, more recent studies have explicitly focused on phone dependency as a distinct construct with its own behavioral patterns and risk factors. These empirical findings underscore the importance of socioemotional skills in understanding phone dependency during childhood, thereby bridging the gap between emotional competencies and digital behaviors.

Additionally, studies have examined how phone dependency may contribute to academic burnout. For example, one explored the relationship between technological addictions and burnout, suggesting that compulsive smartphone use can exacerbate emotional exhaustion and disengagement from schoolwork. However, existing studies rarely explore how socioemotional skills relate to phone dependency and burnout, especially among primary school students84,85.

Latent profile analysis in school engagement and burnout research

To identify patterns of engagement and burnout, this study adopts an latent profile analysis (LPA) approach, which has gained considerable attention in educational psychology for identifying unobserved subgroups within student populations based on multidimensional measures86,87,88. Past LPA research has revealed distinct profiles of student engagement and burnout, such as “high engagement/low burnout” and “low engagement/high burnout” profiles, offering nuanced insights into how students experience school-related demands and resources89,90. While LPA has been widely used across various student populations, its application in primary school contexts remains relatively underexplored. However, recent studies91,92 have applied LPA to younger populations, demonstrating its potential in exploring students’ emotional well-being and anxiety profiles.

Given these gaps, our study aims to clarify the associations among SES, phone dependency, engagement, and burnout in primary school students. Rather than conducting mediation analysis, we focus on an exploratory, correlational study using LPA and logistic regression to identify profiles and predictors. LPA offers a unique, person-centered approach that identifies heterogeneous subgroups of students, allowing us to uncover patterns that may be masked in variable-centered analyses. This approach aligns with the study’s goal to understand the nuanced relationships between these factors and their role in predicting student engagement and burnout. Scholars have emphasized that further research is needed to examine school-related well-being, demands, and resources in different cultural contexts and educational stages5.

Moreover, as highlighted in the previous section, students are expected to consistently develop critical socioemotional competencies, such as persistence, grit, and academic buoyancy, that may be protective against excessive smartphone use and its adverse consequences47. For instance, students with high academic buoyancy may be less prone to phone dependency. In contrast, deficits in socioemotional skills have been linked to a higher risk of technological addictions. Strong SES development and other protective factors will likely contribute to responsible and balanced digital habits93.

This study contributes to the growing body of literature in two ways: First, we extend prior research by examining how SES relates to phone dependency and how these factors are associated with patterns of engagement and burnout among primary school students, addressing a population less frequently studied compared to middle and high school students7,10,93. Second, we employ a person-centered approach to uncover student engagement and burnout profiles, offering nuanced insights into the co-occurrence of digital behaviors, socioemotional competencies, and school-related well-being. Overall, we have asked three research questions as follows:

-

(1)

What are the patterns of primary school students’ school engagement and burnout?

-

(2)

What are the roles of socioemotional skills (e.g., curiosity, grit, academic buoyancy, social engagement, belonging, and loneliness) in predicting profiles among primary school students?

-

(3)

What are the roles of phone dependency and demographic information in predicting engagement (and burnout) profiles?

Methods

Sample and procedure

This study employed a cross-sectional survey design to investigate the relationships between socioemotional skills, phone dependency, and patterns of school engagement and burnout among primary school students. The investigation was carried out in November 2022. Overall, we obtained 630 responses from five mixed-gender elementary schools in a large southwest Chinese province and got 615 valid samples (47% females) through data cleaning, with an effective rate of 97.6%.

Participants were 8 to 11 years old (Mage = 9.69, SDage = 0.79) and were all in the 2nd (68.5%, N = 421), 3rd (26%, N = 160), or 4th (5.5%, N = 34) grade. The questionnaire collected students’ demographic information (i.e., age, sex, grade, migration/left-behind status), self-reported school engagement, burnout, smartphone use, and socioemotional skills. Students and parents signed an informed consent form before taking the survey. Only students whose parents provided written informed consent participated in the study; participation was voluntary. The data were collected using a barcode and a questionnaire with the help of class teachers. For students who could not access cell phones at school, the questionnaire was completed with the assistance of their parents or legal guardians. On average, the students were given 20 min to finish the questionnaire. The study protocol adheres to the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and its subsequent editions and was approved by the University Ethical Review Board for the Humanities and Social and Behavioral Sciences at the authors’ institution.

Measures

To measure our variables, we used validated scales from earlier studies. The scales were translated into Chinese and widely applied in numerous studies across China. In our research, these scales consistently demonstrated acceptable reliability levels for Chinese samples, with Cronbach’s α values for each dimension exceeding 0.75, further confirming their internal consistency. Additionally, cross-sample reliability analysis showed that the scales’ reliability remained stable across different student groups, underscoring their robustness within the Chinese context.

School burnout was assessed with the School Burnout Inventory29. The School Burnout Inventory consists of nine items measuring three components of school burnout: (1) exhaustion at school (i.e., I feel overwhelmed by my schoolwork), (2) cynicism toward the meaning of school (i.e., I feel lack of motivation in my schoolwork and often think of giving up), and (3) a sense of inadequacy at school (i.e., I often have feelings of inadequacy in my schoolwork) to be rated on a 6-point scale (1 = strongly disagree; 6 = strongly agree). The total scores were calculated separately for each of the burnout dimensions. The Cronbach’s α reliabilities were.80, 0.78, and 0.82, respectively, indicating good reliability. This inventory has been widely used and its validity and reliability confirmed in Chinese samples94.

School engagement was measured using a short version of the Schoolwork Engagement Inventory24. The scale consisted of three items measuring experiences of energy (i.e., ‘When I study/work, I feel that I am bursting with energy’), three items measuring dedication (i.e., ‘I am enthusiastic about my studies/work’), and three items measuring absorption (e.g., ‘I feel absorbed in my studies’) at school. The responses were rated on a 7-point scale (1 = not at all; 7 = daily), and a sum score (αse = 0.86) was calculated to represent the students’ overall school engagement. This inventory has been adapted for use in China and validated across various student groups95.

Socioemotional skills were examined using an OECD framework integrating curiosity, grit, academic buoyancy, social engagement, belonging, and loneliness8,45. Curiosity was measured using four items (e.g., ‘I find it fascinating to learn new information.’ ‘I think it is nice to work and ponder on new ideas.’) rated on a 4-point scale (1 = hardly ever; 4 = almost all the time), and a sum score (Cronbach’s α = 0.81) was calculated based on the four items96. Academic buoyancy was measured with three items56 concerning students’ management of study-related stress (e.g., “I am good at managing adversity that is related to studying”, “I don’t let study stress get on top of me”, and “I am good at handling study-related pressure”). The responses were rated on a 5-point scale (1 = totally disagree; 5 = totally agree), and a sum score (Cronbach’s α = 0.74) was calculated based on the three items. Grit was measured using the perseverance of effort (e.g., ‘I am diligent’, four items) of the short version of the grit scale97. The responses were rated on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all like me, 5 = very much like me). Cronbach’s α = 0.72. Social engagement was measured with a scale developed in previous studies18 that consisted of seven items concerning students’ experiences in social situations at school. The responses were rated on a 5-point scale (1 = does not describe me at all; 5 = totally describes me), and a sum score (Cronbach’s α = 0.81) was calculated to represent students’ social engagement at school. Belongingness was measured using a scale developed in previous studies88 that consists of items (e.g., “I am proud of belonging to this school”). The responses were rated on a 7-point scale (1 = not at all true; 7 = entirely true), and a sum score (Cronbach’s α = 0.78) was calculated to describe students’ sense of belonging at school. Loneliness was measured with five questions (e.g., ‘I feel like an outsider’)88, and students rated their answers on a 4-point scale (1 = never; 4 = often). A sum score (αses = 0.86) was calculated based on these items. These socioemotional skills questionnaires have been used in previous studies conducted in the Chinese context98.

Phone dependency was measured using a 7-item assessment scale16. The children responded to all items on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = does not describe me at all; 5 = totally describes me), with higher scores indicating higher levels of mobile phone dependence. The participants were asked to what extent it was true for them in the past year; for example, “I feel anxious if my mobile phone is not around me” and “I am spending more and more time using my mobile phone”. The scale demonstrated good reliability and validity for use with adolescent samples, as reported in previous studies89,90. The scale was translated into Chinese and reviewed by a team of experts in both psychology and education. A pilot study was conducted with a sample of primary school students in China to assess the clarity and comprehension of the items. The scale had good reliability in the present study (αdependence = 0.85).

Last, students’ left-behind status was assessed by asking whether parents (one or both) were working in another city and, if so, if the situation lasted more than six months. Additionally, student characteristics, including age, grade level, and gender, were recorded accordingly. For example, gender was coded 1 = female; 2 = male.

Analysis plan

We utilized the original, validated scales, which vary in response formats (4-, 5-, 6-, and 7-point scales), to maintain psychometric integrity and ensure comparability with prior research, data on school engagement and burnout, socioemotional skills, and phone dependency were standardized (using z-scores) before being entered into statistical models. Mplus statistical software and SPSS were used for all of the analyses99. Missing data were addressed using different approaches depending on the analysis. For the Latent Profile Analysis (LPA), we applied the Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) method in Mplus, which allows the inclusion of all available data without imputing missing values, thereby providing unbiased parameter estimates. For logistic regression analyses, listwise deletion was employed, meaning only participants with complete data on all relevant variables were included. The proportion of missing data was minimal, with no variable exceeding 5%, ensuring that the findings remained reliable and robust.

To explore the homogeneous latent groups of students with varying levels of exhaustion, cynicism, feelings of inadequacy, and engagement, we conducted LPA using a three-step approach. We analyzed the associations between these variables and students’ socioemotional skills and phone dependency, while controlling for measurement errors in identifying latent classes.

For RQ1, Latent profiles of school engagement and burnout were identified using LPA in Mplus 8.0, evaluating 2–5 class models with fit indices (AIC, BIC, VLMR-LRT, BLRT, entropy). Standardized scores of engagement and burnout indicators were used. As for RQ2, predictors of latent profile membership (socioemotional skills) were analyzed using multinomial logistic regression in SPSS 26.0. For RQ3, relationships between phone dependency and demographics were examined using Pearson correlation and hierarchical regression. Before performing logistic regression, we checked for multicollinearity (VIF < 5), logit linearity (Box-Tidwell test), and sample size adequacy (minimum of 10 events per predictor). Missing data were handled with FIML (LPA) and listwise deletion (regression).

Standardized values of school burnout (including exhaustion, cynicism, and feelings of inadequacy) and engagement were used in the latent profile analyses. Models with 2–5 latent classes were first evaluated using student involvement and the three characteristics of school burnout. Several fit indices were used to compare the models: the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), the Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test (VLMR-LRT), the bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (BLRT), and the entropy value. Estimation of the parameters for 2,3…, k-class solutions began with a one-class solution. The final latent profile model was chosen based on the answer that best matched the data and seemed plausible when interpreted. Socioemotional skills, student characteristics, and phone dependency variables were introduced as covariates to the final LPA model to uncover potential predictors of student engagement and burnout profiles. Each covariate was introduced separately into the model. Table 1 displays the correlations, means, and variances for all the variables studied.

Results

Latent profiles of engagement and burnout among primary school students

To establish the most successful model, one to four profile solutions were investigated. We initially investigated the 1-profile solution and subsequently extended our analysis to a 4-profile solution. Although the information criteria (AIC, BIC, SABIC) did not reach a minimum value, the log-likelihood values continued to increase, and the BLRT remained significant for model comparison (p < 0.001), suggesting a solution with more than four profiles. We decided not to consider additional solutions because a nonsignificant p value (0.0729) for the LMR emerged for the first time, which could indicate that there is no need to increase the number of profiles100. In addition, the adjusted-VLMR LRT was significant in the three-profile solution, indicating that this model fits the data better than the four-profile solution. Additionally, adding more profiles may impact the parsimony and ease of interpretation. Consequently, the 3-profile solution was considered more appropriate because the 4-profile solution did not yield a significant improvement. Finally, the entropy value (0.917) of more than 0.80 implied that the cases in this solution could be well classified into different profiles. Overall, the three-profile solution is more economical than the other methods. Table 2 shows the detailed model fit statistics for the LPA.

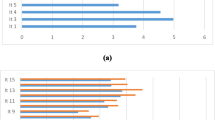

As illustrated in Fig. 1, the three-profile solution was generated from the LPA. In the first profile, 36.1% (n = 222) of the students reported moderate burnout. This group yielded below-average (4 times lower) profile means on engagement and a moderately high level of means against three burnout indicators (exhaustion, cynicism, and inadequacy). A small subgroup of 10.9% (n = 67) of the participants was labeled as “highly burned out and moderately engaged.” This profile stood out for its slightly above-average level of engagement and extraordinarily high level of exhaustion (9 times higher), cynicism (7 times higher), and inadequacy (nearly 4 times higher). The third profile was the largest subgroup (53%, n = 326). It was classified as “highly engaged” since its degree of student engagement was more than twice that of the grand mean but was below the average for all three dimensions of burnout symptoms. Table 3 shows the details of the unstandardized latent profile solutions.

The role of SES in predicting engagement and burnout profiles among primary school students

A follow-up logistic regression analysis was conducted to determine the effect of SES, phone dependency, and student characteristics on predicting the three identified profiles. The final model included two factors related to student characteristics (i.e., grade and left-behind status), six socioemotional skill variables (e.g., social engagement, grit, loneliness, and curiosity), and phone dependency as covariates. Adding these covariates to the model resulted in similar group memberships to those in the final LPA model, regarding both the size and interpretability of the latent groups. The results with the covariates (Table 4) showed clear group differences. Students who reported higher levels of social engagement, buoyancy, and grit were more likely to belong to the highly burned-out and moderately engaged profile (C2) than to the moderately burned-out group (C1). They were also more likely to be classified as highly engaged (C3) rather than moderately burned-out (C1). In contrast, students who reported greater loneliness and curiosity were more likely to fall into the highly burned-out and moderately engaged group (C2) than into the highly engaged group (C3).

Phone dependency, student demographic information, and how they predict engagement and burnout profiles

In terms of phone dependency, students with higher levels of dependency were more likely to fall into the moderately burned-out group (C1) than into the highly burned-out and moderately engaged group (C2). They were also more likely to be classified as highly burned out and moderately engaged (C2) than as highly engaged (C3). Regarding student characteristics, it is worth mentioning that our analysis used only grade and left-behind status as predictors of various engagement and burnout profiles. As indicated in Table 4, according to the odds ratio, those who identified as left-behind children were more likely to belong to the moderately burned-out group than to the highly burned-out and moderately engaged profiles than to their suburban counterparts. Overall, these findings suggest that students in higher grades who attend urban schools are at a greater risk of burnout compared to students in lower grades who attend suburban schools.

Discussion

The profiles of student engagement and school burnout

This study identified three independent profiles. The largest profile, which consisted of 53% of the students, was highly engaged. The second largest group was moderately burned (36.1%). However, we also identified a profile that was high in both burnout and engagement, accounting for 10.9% of the population. For example, among Finnish high school students, approximately one in three reported being engaged, and only 19% were identified as burned10. Focusing on Chinese primary school students, Yang19 found that approximately 40% of students belong to an engaged group, while 16% of students experience moderate to high burnout. These findings are similar to those of the current study since both studies showed that the majority were engaged, and that highly burned-out students were among the minority. Moreover, we identified a group of students who were both highly burned out and highly engaged. These similarities and differences can be explained from two perspectives. First, developmental psychology assumes that individuals undergo systematic changes in cognitive, emotional, and social functioning over time101; however, it is essential to acknowledge that the samples in our study may be mentally immature, necessitating careful consideration of the potential impact on research outcomes. Second, in China, the level of academic stress is high, and competition is fierce in the later years of primary school102. Therefore, it is possible that students need to stay engaged while feeling exhausted and inefficient.

The role of socioemotional skills in student engagement profiles

Regarding the role of socioemotional skills in students’ school engagement and burnout profiles, our findings mostly replicated those of previous studies, where students with higher levels of social skills, academic buoyancy, and grit were more likely to be engaged than those in burned groups. In comparison, those reporting higher levels of loneliness were more likely to be in burned-out profiles10, except for curiosity and belongingness. This finding is interesting since curiosity and belongingness have been suggested to be important buffering variables against school burnout103,104. However, this result could be explained in several ways. First, existing studies primarily focused on secondary school students rather than elementary school-aged children. From the perspective of developmental psychology, secondary school students are more stable in developing their traits, such as engaging with new ideas and generating novel ways to think or act (curiosity) and a sense of belonging105. Second, secondary school participants likely have a more mature understanding of items, thus providing more precise measurements than their elementary counterparts106. This could be the case since, in our study, the factor of belongingness unfortunately failed to predict both engagement and burnout. Furthermore, scholars have suggested that curiosity needs to come with relevant support, such as resources, available to satisfy that curiosity107. Even when resources are present, curiosity does not necessarily lead to desirable outcomes108,109. In other words, curiosity is good only to a certain extent109. Finally, most available studies have focused on Nordic high school samples25,31,38,110, leaving elementary school children from other contexts and cultures underrepresented. Therefore, additional studies are needed to compare different levels of education and varying backgrounds.

Associations between phone dependency, demographic information and engagement (burnout) profiles

Research indicates that both personal and environmental factors influence children’s engagement in elementary school19 and that there is a strong correlation between elementary school student engagement and various academic achievements111. One of the contributions of this study is to explore the predictive roles of phone dependency on student engagement and burnout. As predicted, our study provided evidence that students who reported a higher level of phone dependency were more likely to experience burnout and less likely to engage in learning. This is important since it reveals that more screen time on mobile devices is not necessarily beneficial even for young kids. Previous studies have reported similar results on the relationship between phone use and learning outcomes112. For instance, a recent umbrella review on screen use and learning outcomes revealed that factors such as video games were negatively associated with learning and literacy outcomes112. Moreover, phone dependency has a direct negative relationship with academic engagement in left-behind children. As for left-behind children, Zhen et al.15 demonstrated that mobile phone dependency significantly impairs their academic engagement, primarily through the mediating effects of reduced self-efficacy and increased emotional distress. While our study extends such findings by examining a broader group of primary school students. We further incorporate socioemotional skills as predictors within a person-centered framework to identify engagement–burnout profiles. This approach provides a nuanced perspective on the associations between digital habits, socioemotional competencies, and academic engagement. While our study did not directly test interaction effects, the findings point to the importance of future research examining how these factors may jointly shape engagement, especially among high-risk subgroups such as left-behind children.

In addition, we contributed to the current body of knowledge by further exploring demographic information (e.g., gender, age, left-behind status) and engagement among young children. The results suggest that left-behind children are more likely to belong to burned-out groups than to engaged groups. This result is particularly significant due to China’s large population of school-aged children. Few studies have examined the impact of parental supervision on children’s school experiences in the context of China’s increasing rural–urban migration113. This is particularly true for left-behind children due to their immature self-control114 and the lack of parental supervision115. According to a large body of research, a supportive and cohesive relationship with parents is positively related to children’s academic engagement116. For left-behind children, parental and teacher support is critical in promoting their educational engagement and outcomes113. Therefore, one possible explanation could be that children who are left behind may feel abandoned and lonely117. This could be mitigated by phone dependency through the provision of other socializing opportunities118. Subsequently, they use their phones more frequently to boost their emotional gratification while becoming distracted from their studies113, which eventually leads to decreased academic engagement and increased school burnout111.

Overall, we can conclude that both higher phone dependency and being left behind are potential risk factors for students’ mental well-being (i.e., engagement, and burnout). Perhaps the situation could be improved by bringing parents back into students’ lives and guiding their children’s phone use activities. In our case, the percentage of students who were left behind was substantial (80.5%), and most of the students left their phones unattended with little supervision. A recent study revealed a positive and significant association with literacy when students watch something with a parent (e.g., co-viewing the screen or selecting educational resources)112. Therefore, it could be meaningful to conduct experiments to compare both academic and health outcomes among students, with/without support from parents or guardians.

Limitations and future work

Limitations exist in almost every study, and our study is no exception. First, we used a sample of Chinese primary school children. Readers need to be cautious when interpreting our findings, as local, cultural, historical, and geopolitical contexts are relevant to the research results119. Moreover, as mentioned in the literature review, most available studies have focused on Nordic high schools25,31,38,110, leaving information on elementary school children from other regions unavailable. Future studies can utilize samples from other cultures and countries to gain a deeper understanding of the complex interactions between phone use and socioemotional skills, as well as their contributions to student engagement and burnout. Second, this study employed LPA and regression analysis to identify the profiles and their corresponding predictors. However, LPA cannot analyze or predict relationships between factors, for instance, how SES mediates the relationships between phone dependency and engagement or/and burnout. Due to the absence of consensus‐driven guidelines for both model specification and interpretive procedures, the interpretation of derived profiles is often fraught, as a result, assigned cluster labels can inadequately capture the underlying characteristics of their constituent cases, according to Daumiller et al.120. Therefore, more methods (e.g., structural equation models) are needed to explore the complex interactions among factors. In addition, although our findings at least partially replicate those of past studies111,112, future research is needed to understand better the common and different contributing factors and outcomes associated with engagement profiles, for example, the factors behind the coexistence of high engagement and burnout profiles among school-age children. Lastly, readers should exercise caution when interpreting our results. This is particularly the case since left-behind status was found to be the only statistically significant predictor of student characteristics in this study.

Conclusions

Phone dependence and low academic engagement are prevalent issues among school-age children90. However, few studies have examined the potential relation of phone dependency to academic engagement121,122. To date, while prior studies have examined those variables individually, our study is among the relatively few that investigate the complex interactions among elementary school students’ socioemotional competence, phone dependency, and profiles of engagement and burnout. We identified three independent profiles: moderately burned out, highly burned out, moderately engaged, and highly engaged. Interestingly, half of the students were clustered as highly engaged. Moreover, we found that students with a higher level of phone dependency and those identified as being left behind were more likely to belong to burned-out groups. In contrast, those with a higher degree of socioemotional skills were more likely to be in the engaged profiles and better off overall. Taken together, our results suggest that working on socioemotional skills (e.g., social engagement, buoyancy, and grit) and reducing phone dependency can help reduce school burnout and promote engagement, which, in turn, is of paramount importance for the future success and well-being of youth and society.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- SES:

-

Socioemotional skills

- ENG:

-

Engagement

- EXH:

-

Exhaustion

- CYNI:

-

Cynicism

- INAD:

-

Inadequate

- S_eng:

-

Social engagement

- Pd:

-

Phone dependency

- Curi:

-

Curiosity

- Loney:

-

Loneliness

- Belon:

-

Belongingness

- FP:

-

Free parameters

- LL:

-

Log likelihood value

- LMR(p):

-

P Value for LMR test

- BLRT(p):

-

P Value for BLRT test

References

Upadyaya, K. & Salmela-Aro, K. Development of school engagement in association with academic success and well-being in varying social contexts. Eur. Psychol. (2013).

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C. & Paris, A. H. School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 74, 59–109 (2004).

Salmela-Aro, K. & Upadyaya, K. School burnout and engagement in the context of demands–resources model. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 84, 137–151 (2014).

Wang, M. T. & Fredricks, J. A. The reciprocal links between school engagement, youth problem behaviors, and school dropout during adolescence. Child Dev. 85, 722–737 (2014).

Salmela-Aro, K., Upadyaya, K., Vinni-Laakso, J. & Hietajärvi, L. Adolescents’ longitudinal school engagement and burnout before and during COVID-19—The role of socio-emotional skills. J. Res. Adolesc. 31, 796–807 (2021).

Wang, M. T., Fredricks, J. A., Ye, F., Hofkens, T. L. & Linn, J. S. The math and science engagement scales: Scale development, validation, and psychometric properties. Learn. Instr. 43, 16–26 (2016).

Tuominen-Soini, H., Salmela-Aro, K. & Niemivirta, M. Achievement goal orientations and academic well-being across the transition to upper secondary education. Learn. Individ. Differ. 22, 290–305 (2012).

Kankaras, M. & Suarez-Alvarez, J. Assessment framework of the OECD study on social and emotional skills. OECD Educ. Work. Pap. 207, (2019).

Martin, A. J. & Marsh, H. W. Academic buoyancy: Towards an understanding of students’ everyday academic resilience. J. Sch. Psychol. 46, 53–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2007.01.002 (2008).

Salmela-Aro, K. & Upadyaya, K. School engagement and school burnout profiles during high school—The role of socio-emotional skills. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2020.1785860 (2020).

Mädamürk, K., Upadyaya, K., Hietajärvi, L., Lonka, K. & Salmela-Aro, K. The importance of socio-emotional skills obtained before the COVID-19 pandemic in supporting study engagement during the pandemic and transition to higher education. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 40, 8 (2025).

Domoff, S. E., Borgen, A. L., Foley, R. P. & Maffett, A. Excessive use of mobile devices and children’s physical health. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 1, 169–175 (2019).

Chen, Y. et al. Childhood emotional neglect and problematic mobile phone use among Chinese adolescents: A longitudinal moderated mediation model involving school engagement and sensation seeking. Child Abus. Negl. 115, 104991 (2021).

Kokoç, M. & Göktaş, Y. How smartphone addiction disrupts the positive relationship between self-regulation, self-efficacy and student engagement in distance education. Rev. Psicol. Educ. 30, 500151 (2025).

Zhen, R., Li, L., Ding, Y., Hong, W. & Liu, R. D. How does mobile phone dependency impair academic engagement among Chinese left-behind children?. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 116, 105169 (2020).

Seo, D. G., Park, Y., Kim, M. K. & Park, J. Mobile phone dependency and its impacts on adolescents’ social and academic behaviors. Comput. Hum. Behav. 63, 282–292 (2016).

Chapman, C., Laird, J., Ifill, N., & KewalRamani, A. Trends in High School Dropout and Completion Rates in the United States: 1972–2009 (NCES 2012–006) National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences. Department of Education, 2010. https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/ (2015).

Fredricks, J. A., Filsecker, M. & Lawson, M. A. Student engagement, context, and adjustment: Addressing definitional, measurement, and methodological issues. Learn. Instr. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.02.002 (2016).

Yang, D. et al. The light and dark sides of student engagement: Profiles and their association with perceived autonomy support. Behav. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12110408 (2022).

Yang, D. et al. Not all engaged students are alike: Patterns of engagement and burnout among elementary students using a person-centered approach. BMC Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01071-z (2023).

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C. & Paris, A. H. School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059 (2004).

Bomia, L., Beluzo, D., Demeester, D., Elander, K., Johnson, M. & Sheldon, B. The Impact of Teaching Strategies on Intrinsic Motivation; ERIC Clearinghouse on Elementary and Early Childhood Education, (1997)

Lau, S. & Roeser, R. W. Cognitive abilities and motivational processes in high school students’ situational engagement and achievement in science. Educ. Assess. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203764749-4 (2002).

Salmela-Aro, K. & Upadyaya, K. The schoolwork engagement inventory. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. https://doi.org/10.1037/t08562-000 (2012).

Salmela-Aro, K. & Read, S. Study engagement and burnout profiles among Finnish higher education students. Burn. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burn.2017.11.001 (2017).

Bask, M. & Salmela-Aro, K. Burned out to drop out: Exploring the relationship between school burnout and school dropout. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-012-0126-5 (2013).

Luo, Y., Wang, Z., Zhang, H., Chen, A. & Quan, S. The effect of perfectionism on school burnout among adolescence: The mediator of self-esteem and coping style. Pers. Individ. Dif. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.08.056 (2016).

May, R. W., Bauer, K. N. & Fincham, F. D. School burnout: Diminished academic and cognitive performance. Learn. Individ. Differ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2015.07.015 (2015).

Salmela-Aro, K., Kiuru, N., Leskinen, E. & Nurmi, J. E. School burnout inventory (SBI) reliability and validity. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759.25.1.48 (2009).

Maslach, C. & Leiter, M. P. Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20311 (2016).

Salmela-Aro, K., Moeller, J., Schneider, B., Spicer, J. & Lavonen, J. Integrating the light and dark sides of student engagement using person-oriented and situation-specific approaches. Learn. Instr. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.01.001 (2016).

Schaufeli, W. B., Martinez, I. M., Pinto, A. M., Salanova, M. & Bakker, A. B. Burnout and engagement in university students: A cross-national study. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022102033005003 (2002).

Shin, H., Lee, J., Kim, B. & Lee, S. M. Students’ perceptions of parental bonding styles and their academic burnout. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-012-9218-9 (2012).

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F. & Schaufeli, W. B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 86, 499 (2001).

Tarasova, K. S. Development of socioemotional competence in primary school children. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.10.166 (2016).

Kankaras, M.; Suarez-Alvarez, J. 2019 Assessment framework of the OECD study on social and emotional skills. OECD Educ. Work. Pap. https://doi.org/10.1787/5007adef-en.

Abós, Á., Sevil-Serrano, J., Haerens, L., Aelterman, N. & García-González, L. Toward a more refined understanding of the interplay between burnout and engagement among secondary school teachers: A person-centered perspective. Learn. Individ. Differ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2019.04.008 (2019).

Tuominen-Soini, H. & Salmela-Aro, K. Schoolwork engagement and burnout among finnish high school students and young adults: Profiles, progressions, and educational outcomes. Dev. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033898 (2014).

Williamson, B. Psychodata: Disassembling the psychological, economic, and statistical infrastructure of ‘social-emotional learning’. J. Educ. Policy https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2019.1672895 (2021).

Kautz, T. Heckman, J.J., Diris, R., Ter Weel, B. & Borghans, L. Fostering and measuring skills: Improving cognitive and non-cognitive skills to promote lifetime success; national bureau of economic research (2014). https://doi.org/10.3386/w20749.

Moroni, G., Nicoletti, C. & Tominey, E. Child socioemotional skills: The role of parental inputs. IZA Discussion Paper https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3415778 (2019).

Lechner, C. M., Anger, S. & Rammstedt, B. Socio-emotional skills in education and beyond: Recent evidence and future research avenues. Res. Handb. Sociol. Educ. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788110426.00034 (2019).

OECD. Social and Emotional Skills for Better Lives: Findings from the OECD Survey on Social and Emotional Skills 2023, OECD Publishing, (2024).

Huttunen, I., Upadyaya, K. & Salmela-Aro, K. Longitudinal associations between adolescents’ social-emotional skills, school engagement, and school burnout. Learn. Individ. Differ. 115, 102537 (2024).

Chernyshenko, O.S., Kankaraš, M., Drasgow, F. Social and emotional skills for student success and well-being: Conceptual framework for the OECD study on social and emotional skills. OECD Publishing, (2018). https://doi.org/10.1787/db1d8e59-en.

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D. & Schellinger, K. B. The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Dev. 82, 405–432 (2011).

Gestdottir, S. & Lerner, R. Positive development in adolescence: The development and role of intentional self-regulation. Hum. Dev. 51, 202–224. https://doi.org/10.1159/000135757 (2008).

Lechner, C.M., Anger, S. & Rammstedt, B. Socio-emotional skills in education and beyond: Recent evidence and future research avenues. Res. Handb. Sociol. Educ. (2019).

Boon-Falleur, M. et al. Simple questionnaires outperform behavioral tasks to measure socioemotional skills in students. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-04046-5 (2022).

Eriksen, E. V. & Bru, E. Investigating the links of social-emotional competencies: Emotional well-being and academic engagement among adolescents. Scand. J. Educ. Res. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2021.2021441 (2023).

Korbel, V. & Paulus, M. Do teaching practices impact socio-emotional skills?. Educ. Econ. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2990770 (2018).

Caprara, G. V., Vecchione, M., Alessandri, G., Gerbino, M. & Barbaranelli, C. The contribution of personality traits and self-efficacy beliefs to academic achievement: A longitudinal study. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 81, 78–96 (2011).

Sheridan, S. M., Knoche, L. L., Edwards, C. P., Bovaird, J. A. & Kupzyk, K. A. Parent engagement and school readiness: Effects of the getting ready intervention on preschool children’s social–emotional competencies. Early Educ. Dev. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409280902783517 (2010).

Grusec, J. E. & Davidov, M. Integrating different perspectives on socialization theory and research: A domain-specific approach. Child Dev. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01426.x (2010).

Weissberg, R.P., Durlak, J.A., Domitrovich, C.E. & Gullotta, T.P. Social and emotional learning: Past, present, and future (2015).

Martin, A. J. & Marsh, H. W. Academic buoyancy: Towards an understanding of students’ everyday academic resilience. J. Sch. Psychol. 46, 53–83 (2008).

Shi, H. et al. How parental migration affects early social–emotional development of left-behind children in rural China: A structural equation modeling analysis. Int. J. Public Health 65, 1711–1721 (2020).

Zhang, J., Yan, L., Qiu, H. & Dai, B. Social adaptation of Chinese left-behind children: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 95, 308–315 (2018).

OECD. Beyond Academic Learning: First Results from the Survey of Social and Emotional Skills; OECD Publishing, (2021). https://doi.org/10.1787/92a11084-en.

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL). CASEL: Collaborative for academic, social, and emotional learning. https://casel.org (2025).

Singapore Positive Education Network (SPEN). Singapore Positive Education Network (SPEN). https://www.spen-network.com/ (2025).

Harris, B., Regan, T., Schueler, J. & Fields, S. A. Problematic mobile phone and smartphone use scales: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 11, 672 (2020).

Roberts, J. A., Pullig, C. & Manolis, C. I need my smartphone: A hierarchical model of personality and cell-phone addiction. Pers. Individ. Dif. 79, 13–19 (2015).

Sunday, O. J., Adesope, O. O. & Maarhuis, P. L. The effects of smartphone addiction on learning: A meta-analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 4, 100114 (2021).

Seo, M. & Choi, E. Classes of trajectory in mobile phone dependency and the effects of negative parenting on them during early adolescence. Sch. Psychol. Int. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034317745946 (2018).

Soror, A.A.; Steelman, Z.R.; Limayem, M. Discipline yourself before life disciplines you: Deficient self-regulation and mobile phone unregulated use. In Proceedings of the 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), IEEE (2012). https://doi.org/10.1109/hicss.2012.219

Abadi-Akashe, Z., Zamani, B. E., Abedini, Y., Akbari, H. & Hedayati, N. The relationship between mental health and addiction to mobile phones among university students of Shahrekord, Iran. Addict. Health 6, 93 (2014).

Billieux, J., Van der Linden, M., d’Acremont, M., Ceschi, G. & Zermatten, A. Does impulsivity relate to perceived dependence on and actual use of the mobile phone?. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1289 (2007).

Chen, Y.F. The relationship of mobile phone use to addiction and depression amongst American college students. Korean Broadcast. Soc. Semin. Rep., 344–352 (2004).

Leung, L. Linking psychological attributes to addiction and improper use of the mobile phone among adolescents in Hong Kong. J. Child Media https://doi.org/10.1080/17482790802078565 (2008).

Lopez-Fernandez, O., Honrubia-Serrano, L., Freixa-Blanxart, M. & Gibson, W. Prevalence of problematic mobile phone use in British adolescents. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0260 (2014).

Park, C. & Park, Y. R. The conceptual model on smartphone addiction among early childhood. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. https://doi.org/10.7763/ijssh.2014.v4.336 (2014).

Sánchez-Martínez, M. & Otero, A. Factors associated with cell phone use in adolescents in the community of Madrid (Spain). Cyberpsychol. Behav. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2008.0164 (2009).

Augner, C. & Hacker, G. W. Associations between problematic mobile phone use and psychological parameters in young adults. Int. J. Public Health https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-011-0234-z (2012).

Cha, S. S. & Seo, B. K. Smartphone use and smartphone addiction in middle school students in Korea: Prevalence, social networking service, and game use. Health Psychol. Open https://doi.org/10.1177/2055102918755046 (2018).

Lin, Y. H. et al. Development and validation of the smartphone addiction inventory (SPAI). PLoS ONE https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0098312 (2014).

Zhang, M. X. & Wu, A. M. Effects of childhood adversity on smartphone addiction: The multiple mediation of life history strategies and smartphone use motivations. Comput. Hum. Behav. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107298 (2022).

Carli, V. et al. The association between pathological internet use and comorbid psychopathology: A systematic review. Psychopathology https://doi.org/10.1159/000337971 (2012).

Tonioni, F. et al. Socio-emotional ability, temperament and coping strategies associated with different use of Internet in Internet addiction. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 22, 3461–3476. https://doi.org/10.26355/eurrev_201806_15171 (2018).

Brzozek, C. et al. Uncertainty analysis of mobile phone use and its effect on cognitive function: The application of Monte Carlo simulation in a cohort of Australian primary school children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16132428 (2019).

Noruzi Kuhdasht, R., Ghayeninejad, Z. & Nastiezaie, N. The relationship between phone dependency with psychological disorders and academic burnout in students. J. Res. Health https://doi.org/10.29252/jrh.8.2.189 (2018).

Olenik Shemesh, D., Heiman, T. & Wright, M. F. Problematic use of the internet and well-being among youth from a global perspective: A mediated-moderated model of socio-emotional factors. J. Genet. Psychol. 185, 91–113 (2024).

Sarti, D. et al. Tell me a story: Socio-emotional functioning, well-being and problematic smartphone use in adolescents with specific learning disabilities. Front. Psychol. 10, 2369 (2019).

Biblekaj, V., Robles, R. & Kahlbaugh, P. Socioemotional characteristics of cell phone addiction: The case of nomophobia. J. Soc. Media Soc. 13, 74–89 (2024).

Montroy, J. J., Bowles, R. P., Skibbe, L. E., McClelland, M. M. & Morrison, F. J. The development of self-regulation across early childhood. Dev. Psychol. 52, 1744 (2016).

Martin, A. J. & Marsh, H. W. Academic buoyancy: Towards an understanding of students’ everyday academic resilience. J. Sch. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2007.01.002 (2008).

Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D. & Kelly, D. R. Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1087 (2007).

Kouluterveyskysely. Terveyden ja Hyvinvoinnin Laitos, (2014).

Fu, X. et al. The impact of parental active mediation on adolescent mobile phone dependency: A moderated mediation model. Comput. Hum. Behav. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106280 (2020).

Zhen, R., Li, L., Ding, Y., Hong, W. & Liu, R. D. How does mobile phone dependency impair academic engagement among Chinese left-behind children?. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105169 (2020).

Gierczyk, M., Charzyńska, E., Dobosz, D., Hetmańczyk, H. & Jarosz, E. Subjective well-being of primary and secondary school students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A latent profile analysis. Child Indic. Res. 15, 2115–2140 (2022).

Mammarella, I. C., Donolato, E., Caviola, S. & Giofrè, D. Anxiety profiles and protective factors: A latent profile analysis in children. Pers. Individ. Dif. 124, 201–208 (2018).

Klimenko, O., Cataño Restrepo, Y. A., Otálvaro, I. & Úsuga Echeverri, S. J. Risk of addiction to social networks and the Internet and its relationship with life and socioemotional skills in a sample of high school students from the municipality of Envigado. Psicogente https://doi.org/10.17081/psico.24.46.4382 (2021).

Hu, Q. & Schaufeli, W. B. The factorial validity of the Maslach burnout inventory–student survey in China. Psychol. Rep. 105, 394–408 (2009).

Teuber, Z., Tang, X., Salmela-Aro, K. & Wild, E. Assessing engagement in Chinese upper secondary school students using the Chinese version of the schoolwork engagement inventory: Energy, dedication, and absorption (CEDA). Front. Psychol. 12, 638189 (2021).

Litman, J. A. Interest and deprivation factors of epistemic curiosity. Pers. Individ. Dif. 44, 1585–1595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.01.014 (2008).

Duckworth, A. & Gross, J. J. Self-control and grit: Related but separable determinants of success. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 23, 319–325 (2014).

Shao, Z., Tang, Y. & Zhang, J. The technical report on the 2nd round OECD survey of social and emotional skills of Chinese adolescence. J. East China Norm. Univ. Educ. Sci. 42, 58 (2024).

Muthén, L.; Muthén, B. Mplus (Version 8) [Computer Software] 1998–2017.

Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T. & Muthén, B. O. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct. Equ. Model. 14, 535–569 (2007).

Baltes, P. B., Reese, H. W. & Lipsitt, L. P. Life-span developmental psychology. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 31, 65–110. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.31.020180.000433 (1980).

Hesketh, T. et al. Stress and psychosomatic symptoms in Chinese school children: Cross-sectional survey. Arch. Dis. Child. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2009.171660 (2010).

Litman, J. A. Interest and deprivation factors of epistemic curiosity. Pers. Individ. Dif. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.01.014 (2008).

Ornaghi, V., Conte, E., Cavioni, V., Farina, E. & Pepe, A. The role of teachers’ socioemotional competence in reducing burnout through increased work engagement. Front. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1295365 (2023).

Amponsah, M. O. Personality traits mediating sense of belonging and academic curiosity among students in Ghana. Educ. Res. Int. 2023, 6834304 (2023).

Borgers, N., De Leeuw, E. & Hox, J. Children as respondents in survey research: Cognitive development and response quality. Bull. Sociol. Methodol. 66, 60–75 (2000).

Engel, S. Children’s need to know: Curiosity in schools. Harv. Educ. Rev. 81, 625–645 (2011).

Arnone, M. P., Small, R. V., Chauncey, S. A. & McKenna, H. P. Curiosity, interest, and engagement in technology-pervasive learning environments: A new research agenda. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-011-9190-9 (2011).

Kidd, C. & Hayden, B. Y. The psychology and neuroscience of curiosity. Neuron 88, 449–460 (2015).

Salmela-Aro, K., Upadyaya, K., Hakkarainen, K., Lonka, K. & Alho, K. The dark side of internet use: Two longitudinal studies of excessive internet use, depressive symptoms, school burnout, and engagement among Finnish early and late adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0494-2 (2017).

Bae, C. L., Les DeBusk-Lane, M. & Lester, A. M. Engagement profiles of elementary students in urban schools. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101880 (2020).

Sanders, T. et al. An umbrella review of the benefits and risks associated with youths’ interactions with electronic screens. Nat. Hum. Behav. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-023-01712-8 (2023).

Chen, S., Adams, J., Qu, Z., Wang, X. & Chen, L. Parental migration and children’s academic engagement: The case of China. Int. Rev. Educ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-013-9390-0 (2013).

Steinberg, L. et al. Age differences in sensation seeking and impulsivity as indexed by behavior and self-report: Evidence for a dual systems model. Dev. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012955 (2008).

Dong, C., Cao, S. & Li, H. Young children’s online learning during COVID-19 pandemic: Chinese parents’ beliefs and attitudes. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105440 (2020).

Hannum, E.; Park, A., (Eds). Education and Reform in China, 1st ed. (2007). https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203960950.

Jia, Z. & Tian, W. Loneliness of left-behind children: A cross-sectional survey in a sample of rural China. Child Care Health Dev. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01110.x (2010).

Enez Darcin, A. et al. Smartphone addiction and its relationship with social anxiety and loneliness. Behav. Inf. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929x.2016.1158319 (2016).

Selwyn, N. & Jandrić, P. Postdigital living in the age of Covid-19: Unsettling what we see as possible. Postdigit. Sci. Educ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00166-9 (2020).

Daumiller, M., Janke, S., Butler, R., Dickhäuser, O. & Dresel, M. Merits and limitations of latent profile approaches to teachers’ achievement goals: A multi-study analysis. PLoS ONE 18, e0284608 (2023).

Li, N. et al. The relationship between mobile phone dependence and academic burnout in Chinese college students: A moderated mediator model. Front. Psychiatry 15, 1382264 (2024).

Peng, B. Analysis on the relationships of smartphone addiction, learning engagement, depression, and anxiety: Evidence from China. Iran. J. Public Health 52, 2333 (2023).

Funding

This work was supported by the Guangdong Philosophy and Social Science Foundation (GD25YJY43); Youth Project of Humanities and Social Sciences Financed by Ministry of Education of China (22YJC880072); Education Scientific Planning of Zhejiang Province (2025SCG356);The second batch of Zhejiang undergraduate provincial-level teaching reform initiatives during the 14th Five-Year Plan period(JGBA2024095); and Key project of the 2024 Teaching Reform Program of Zhejiang Normal University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DY and CW contributed equally to this work. DY and CW contributed to the design of the work; acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data; drafted the work and substantively revised it. ZL contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, and substantively revised it. CF contributed to the design of the work; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study was performed after obtaining ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of College of Child Development and Education, Zhejiang Normal University. Following the Declaration of Helsinki, informed consent for children to participate in the study was obtained from their legal guardians. In addition, we anonymized the names of the children used in the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, D., Wang, C., Li, Z. et al. The role of socioemotional skills and phone dependency in predicting patterns of school engagement and burnout among primary school students. Sci Rep 15, 39493 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22912-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22912-4