Abstract

The accurate prediction of gas-liquid two-phase flows in industrial systems relies on the careful selection of interfacial force models, particularly the drag force, which dominates momentum transport between phases. This study numerically investigates six widely adopted drag coefficient models using the Eulerian-Eulerian two-fluid framework coupled with the homogeneous “MUltiple Size” Group (MUSIG) population balance model in ANSYS CFX 14.5. The primary objective is to evaluate the predictive performance of these models in capturing local radial gas volume fractions under polydispersed bubbly flow conditions. Simulations were validated against benchmark experimental data from Lucas et al. and Monrós-Andreu et al., which cover a range of superficial gas and liquid velocities. Mean absolute error (MAPE) was used as the main error indicator for model evaluations. The results from the study show that while all models qualitatively behaved differently depending on the test case considered, the model by Grace et al. offered superior predictions (MAPE < 6% for all test cases) within the core region for the MTLoop dataset obtained from Lucas et al. Additionally, all models performed relatively poorly near the wall when compared with the Lucas et al. dataset. In contrast, all models performed better when compared with the Monrós-Andreu et al. dataset, which does not involve transition regimes or very high gas superficial velocities. Notably, the Simonnet et al. model exhibited enhanced performance in high gas superficial velocity cases due to its incorporation of swarm effects. Across both datasets, all models showed better agreement to some extent with experimental data in the pipe core region than near the wall. The insights from this work are valuable for selecting appropriate interfacial force models for industrial simulations and highlight the need for developing drag models for the dynamics of bubbly flows.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multiphase flows are encountered in many industrial systems, including chemical, petroleum, biochemical, pharmaceutical, water treatment, metallurgical, food processing and power generation industries. In a gas-liquid two-phase flow system, a number of different flow patterns, with different characteristic features, may arise depending on the pipe diameter, pipe inclination and the specific mass flow rate of each phase. The flow pattern classifications that are common and widely used in literature for concurrent gas and liquid flow in a vertical upward flow are bubbly flow, slug flow, churn flow, annular flow and mist flow5,6. Among these flow patterns, bubbly flow is of key importance. Bubbly flow is the most stable flow regime, and hence industrial processes involving gas-liquid flow are usually operated in the bubbly flow regime. In addition, bubbly flow conditions are of the greatest interest because they present a large interfacial area required for excellent heat and mass transfer, efficient mixing and optimum contact time for reacting species7,8,9.

In most industries, bubble columns are the equipments used to handle bubble flow systems. For instance, bubble columns are used as flotation cells in the mineral processing industry, as aeration units in the water production and wastewater treatment industries, and as fermentation units in the biochemical industry. In the chemical process industry, bubble columns are used in many processes, including oxidation, chlorination, alkylation, polymerisation of organic compounds, hydration and chemical gas cleaning10,11,12,13,14,15.

Depending on the bubble size and its distribution, bubbly flow could be classified as homogeneous or heterogeneous. For homogeneous flow, the bubble size distribution is narrow with a uniform distribution of the gas content over the cross-section of the column. The gas velocity in this case is low, hence there is negligible bubble breakup and coalescence. The alternate flow regime is characterised by a heterogeneous flow pattern with a broader bubble size distribution. The heterogeneous flow (also referred to as polydispersed flow) pattern is characterised by high gas velocity with bubble breakup and coalescence effects5,7,8,16. One of the attributes of polydispersed gas-liquid two-phase flow is that the different sizes of the dispersed phase interact with each other through the mechanisms of breakup and coalescence. Analysis of this type of flow requires the use of a population balance model.

Population balance is a well-established method in computing the size distribution of the dispersed phase and accounting for the breakup and coalescence effects in bubbly flow systems17. Several population balance models, including the homogeneous “MUlti-SIzeGroup” (MUSIG), have been developed for the investigation of polydispersed multiphase flow systems. Several investigators, includingYeoh et al.18 andCheung et al.19 employed the MUSIG model in their studies, and this model has been adopted in this study. Details on this model and other population balance models are elaborated in the studies by Cheung et al.19, Deju et al.11, Ekambara et al.17, Askari et al.20, and Sun et al.21.

The interface forces on bubbles are also of great importance in the numerical prediction of gas-liquid two-phase flow systems. This is because they largely determine the interfacial processes and turbulent dynamics of the flow, which in turn affect mass and heat transfer between the phases. It is therefore necessary to give serious attention to accurate modelling of these forces, which are key to understanding the dynamics of gas-liquid two-phase flow systems. Although several studies on interface forces in bubbly flow have been conducted, knowledge on them remains insufficient, even for the development of models for a single bubble in a stagnant liquid. Additionally, interface area concentration in polydispersed bubbly flow is a key component in the prediction of interfacial drag and void fraction22,23. Lote et al.24 and Yamoah et al.25 both observed that all models evaluated in their study underpredicted interfacial area concentration at the core peak region of a flow conduit. The authors attributed this to constant bubble size assumption and also the neglect of bubble break-up and coalescence in their modelling. They suggested the use of either two-group IATE, MUSIG, QMOM or any other population balance model that can capture bubble break-up and coalescence. This study takes drag model evaluations a step further by incorporating the homogeneous MUSIG population balance method into the numerical assessments.

Many investigators, including Cheung et al.5, Li8, Lucas et al.26, Tomiyama et al.27, Yamoah et al.25, Zhang7, Ziegenhein et al.16 used Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) methods to numerically investigate gas-liquid two-phase flow process systems. The parameters of key importance that are primarily investigated in such flow systems include gas phase fraction, fluid velocities and their distributions, interfacial area concentration, and Sauter mean bubble diameter. To obtain reasonable results, it is important to carefully select the interface force models incorporated into the momentum transport equation during the investigation of multiphase flow systems. The drag force model, in particular, requires critical attention since its effect is more pronounced than that of other interface forces; hence, the overall accuracy of the numerical calculation largely depends on the formulation of the drag coefficient model. Several drag coefficient models have been developed over the years to calculate the drag force on fluid particles. The selection of a particular drag coefficient model in any numerical investigation is therefore a challenging task28,29. Thus, in this study, numerical investigations were carried out on selected drag coefficient models that have received attention from other researchers and have been widely adopted in multiple flow studies. The objective is to assess the selected drag coefficient models for their ability to predict real flow situations, such as those found in industrial gas-liquid two-phase flow systems.

The structure of the study, as presented in the subsequent sections, has been summarised here. Section “Governing equations” presented the governing equations and the general expression for the drag force, which is the focus of this study. In Sect. “Numerical investigation”, the numerical investigation was presented, where expressions of selected drag coefficient models were presented, and details on the conditions under which each was formulated were discussed. The non-drag forces and the population balance model used have also been presented in this section. The description of the test facilities from which the data used for the validation of the numerical results was obtained is presented in Sect. “Experimental facility”. In Sect. “Numerical modelling”, details of the numerical modelling procedure, boundary conditions, and the turbulent models used are presented. The results and discussion of the numerical calculations performed for the various drag coefficient models are presented in Sect. “Results and discussion”. Finally, the conclusions drawn from the major findings of the study are presented in Sect. “Conclusion and recommendations”, along with recommendations.

Governing equations

The governing equations for conservation of mass and momentum required for each of the phases are presented in Eqs. 1 and 2, respectively, where \({\alpha _k}\)is the phase fraction of phase k, k is liquid (l) or gas (g), \({{{\vec {\text{V}}}}_{\text{k}}}\) is the velocity of phase k, τk is shear stress, and \({{\vec{\text{F}}}}\) is the sum of all the interfacial forces as expressed in Eq. 3. The forces on the right-hand side of Eq. 3 are drag, lift, wall lubrication and turbulent dispersion forces, respectively. Details on these forces can be found in the studies by Besagni et al.30, Hjertager31, Maliska et al.32, and Rzehak et al.33.

The expression for the drag force on fluid particles (droplet or gas bubble) moving in a fluid has been well established and expressed as Eq. 4, where CD, db, ρl, Ul, Ug and αg represent drag coefficient, bubble diameter, liquid density, liquid velocity, gas velocity and gas volume fraction, respectively16,30,32. The drag force originates from “skin friction” (viscous drag) due to the motion of the dispersed phase (bubbles in this case) in the continuous phase, as well as from uneven pressure distribution around the moving bubble caused by its shape and size (form drag). Several drag coefficient models have been developed over the years to calculate the drag force on fluid particles. Some of these models have been implemented in CFD software for simulating gas–liquid flow systems25,28,32.

Numerical investigation

Six drag coefficient models were investigated. The Eulerian two-fluid model coupled with MUSIG was implemented in the commercial CFD package, ANSYS CFX 14.5, for the investigation. The predicted radial gas volume fraction was validated against the experimental data ofLucas et al.1 and Monrós-Andreu et al.2. The gas volume fraction was chosen for the comparison of the models because it is the key parameter in the quantification of gas-liquid flow mixture, and its accurate prediction provides vital information for safety analysis and design optimization of production processes34.

Drag force coefficient

The drag coefficient models selected for the investigations were based on the attention they received from other investigators. These models include those ofGrace et al.3,35, Schiller-Nauman14,35, Ishii et al.36, Simonnet et al.4, Behzadi et al.37, Tomiyama et al.27. The models of Grace et al.3, Schiller-Nauman51, andTomiyama et al.27 were among the old models formulated for single fluid particles and, hence, dilute systems, where the dispersed phase fraction is low; therefore, they do not account for the bubble swarm effect. Although theIshii et al.36 model is also one of the older models, it takes the swarm effect into consideration in its formulation, and the same applies to the recent models ofSimonnet et al.4 and Behzadi et al.37. Details on these models are discussed in this section.

TheGrace et al.3 model was formulated based on observations of a single bubble using air–water data, and it is also suitable for cases with low gas volume fractions. The model, as presented in Eq. 5, considered the bubble as having a distorted form similar to an ellipse25,35. UT in Eq. 5 represents the bubble terminal velocity, which is correlated as presented in Eq. 6. Parameters J and H are expressed in Eqs. 7 and 8, respectively.

In Eq. 8, µref denotes the molecular viscosity of water, which is assumed to be 0.0009 Pa·s. µl, Eo, and Mo are the viscosity of the liquid, Eotvos and Morton numbers, respectively, as expressed in Eqs. 9 and 10, where σ is surface tension. The Grace et al.3 model applies to the range of 1.5 × 10−12 < Mo < 10−3, Eo < 40 and Reb > 0.237.

The model of Schiller-Naumann51 was originally formulated for flow past solid spherical particles35,38. At sufficiently small solid particle Reynolds numbers (the viscous regime), fluid particles (bubbles or droplets) behave in the same manner as solid spherical particles. Hence, the drag coefficient of Schiller-Naumann51 is well approximated for gas-liquid flow systems in the viscous regime. The version of Schiller-Naumann51 implemented in ANSYS CFX is expressed as Eq. 11 (Ansys CFX, 2013). Urel is the gas-liquid slip velocity and Reb is bubble Reynolds number. The model is applicable in the range of Reb > 1 (Pang and Wei, 2011)

TheIshii et al.36 drag coefficient model was formulated using analogies of flow past a single solid sphere and the drag similarity criterion between a single particle and a multi-particle system based on the mixture viscosity model. The model was extended to distorted particle systems and hence classified into different flow regimes: dense spherical, dense distorted (elliptical shape), and dense spherical cap (more distorted) regimes. These regime classifications have been well discussed in35,36,39 and not repeated here. The model as implemented in ANSYS CFX is given in Eq. 13, where Rem is the mixture Reynolds number expressed as Eq. 14, and µm is the mixture viscosity as expressed in Eq. 15 (Ansys CFX, 2013). In Eq. 15, αmax represent user-defined Maximum Packing value for the gas phase and its default value in ANSYS CFX is 1 and the same value is used in this work.

The dense distorted particle regime is modelled using Eq. 16. The parameter Zα is defined in Eq. 17, and f is expressed in Eq. 18. The spherical cap regime was also modelled as Eq. 19. The automatic switching between the various flow regimes by the Ishii et al.36 models is achieved using the expression in Eq. 20. The model is applicable in the ranges of 0 < Reb < 1000 for spherical regime and Reb ≥ 1000 for both the distorted particle and spherical cap regimes35.

Simonnet et al.4 formulated a drag coefficient model using demineralised water–air systems. They indicated that most of the existing drag coefficient models used in CFD investigations were based on single fluid particle (bubble or droplet) system and hence could not cater well for swarm fluid particle systems very well. Through extensive experimental investigation of hydrodynamic parameters in demineralised water–air system in addition to curve fitting, they suggested modification of such drag coefficients to cater for multi-fluid particle systems. Their model could be expressed as Eq. 21. The parameter, CD∞, is the drag coefficient of an isolated bubble in an infinite medium which can be expressed as Eq. 22. V∞ is the terminal velocity of an isolated bubble in a stagnant liquid, and it is evaluated in this study using the correlation described in Eq. 234,25. The parameter, Sα, is a correction factor that accounts for the swarm bubble effect so that the local void fraction represents that of a multi-bubble system and is evaluated using Eq. 26.Simonnet et al.4 compared their proposed model with experimental results and observed that the model increased with the gas phase fraction up to about 15%, beyond which it decreased. They therefore set the value of the exponent, m, to 25 to account for the trend.

Behzadi et al.37 proposed a drag coefficient model by correlating experimental data obtained from literature. They argued that most drag coefficient models used in numerical codes for gas-liquid systems were formulated for single-bubble systems, where the dispersed phase fraction is low, and therefore could not produce accurate results when applied to multi-bubble systems, where the dispersed phase fraction is high. Again, the few older models formulated for higher gas phase fraction systems should behave in such a way that they approach models for single bubble systems when the gas phase fraction approaches zero; however, they do not exhibit such characteristics. Additionally, those that exhibit such characteristics were formulated based on old experimental data and could not produce accurate results when applied in numerical investigations. They therefore proposed a model (Eq. 27) that consists of a single particle system drag coefficient model and a multiplier to account for a multi-bubble system, while simultaneously approaching the behaviour of a single bubble system model as the gas phase fraction approaches zero. The model coefficients, K1 = 3.64 and K2 = 0.864, were determined using a nonlinear fitting procedure implemented in the graph plotting package “GRACE” (Grace Team). Their model applies to steady bubble flow regime37.

Tomiyama et al.27proposed drag coefficient models for single bubbles across a wide range of bubble diameters and gravity conditions. Their model was based on the force balance of a single bubble in stagnant liquid and empirical correlations of the terminal rising velocity of a single bubble. They considered the degree of contamination, and, in the case of water, they proposed three models for the drag coefficient corresponding to pure, slightly contaminated, and contaminated systems. The correlations were compared with experimental data collected under a wide range of Reynolds, Morton, and Eotvos numbers (10−3 < Re < 105, 10−14 <Mo < 107, and 10−2 < Eo < 103), and satisfactory agreements were reported27. In this study, their model for a slightly contaminated system, as given by Eq. 29, was used. This is because the system used in the generation of the experimental data used for the validation of the numerical results was an ordinary water-air system in the case of Lucas et al. (2005) and an osmotized water-air system in the case ofMonrós-Andreu et al.2 which could not be considered as pure systems but susceptible to some degree of contamination.

Lift force

The lift force represents the lateral force experienced by a body moving in rotational shear flow and can be expressed as in Eq. 30, where CL is the lift force coefficient25,30,40

Many investigators have proposed many lift force coefficients over the years. However, the one proposed by Tomiyama et al.27, which effectively captures the experimental observation of de-mixing between “small” and “large” bubbles in a vertical co-current upward gas-liquid flow, is used in this study. The formulation of this coefficient model is presented in Eq. 31. The function f(Eod) is defined as in Eq. 32, where Eod, is the Eotvos number based on the longest axis, dH (Eq. 34), of a deformed bubble and it is expressed as in Eq. 33.

Wall lubrication force

When a bubble moves close to the wall, the liquid speed between the bubble and the wall is lower than that between the bubble and the main flow, resulting in a hydrodynamic pressure difference driving the bubble away from the wall. This driving force is the wall lubrication force which can be represented as in Eq. 35 for gas-liquid flow systems30,35,40

C WL and \({\widehat {{\text{n}}}_{\text{W}}}\)represent the wall lubrication force coefficient and the unit normal vector perpendicular to the wall and pointing away from the wall into the fluid, respectively. The wall lubrication coefficient model presented byAntal et al.41 is given in Eq. 36.

y w is the distance from the wall, and Cw1 and Cw2 are the model coefficients. The model coefficients Cw1 = − 0.01 and Cw2 = 0.05, which are default values in ANSYS CFX were used in this study. The wall lubrication coefficient formulation ofFrank et al.42 is presented in Eq. 3725,35. The parameters, CWD and CWC are the damping and cut-off coefficients respectively and p represents power law constant. Their values in ANSYS CFX as default are CWD = 6.8, CWC = 10.0 and p = 1.7. In this study the power law constant (p) was modified from its default value to 1.3.

Turbulent dispersion force

The distribution of bubbles dispersed in the liquid phase is affected by the turbulent diffusion caused by eddies of the liquid phase. The turbulent dispersion force is a force that accounts for the impacts of turbulent fluctuations of liquid velocity on the gas bubbles. It has a significant impact on the radial gas-phase distribution. The Favre Averaged model developed by Burns et al.43, which is implemented in this study, can be expressed as in Eq. 3930,35,44. CD, and vt represent the drag coefficient and the turbulent kinematic viscosity of the continuous phase, respectively. Sct is the turbulent Schmidt number for the continuous phase with a default value of 0.9 and \({\text{C}}_{{{\text{TD}}}}^{{{\text{AFD}}}}\)is a user-modifiable multiplier with default value of 1 but calculations in this study were done using 0.5 for \({\text{C}}_{{{\text{TD}}}}^{{{\text{AFD}}}}\)

Population balance model

The simulation of bubble coalescence and breakup requires solving a population balance equation. Therefore, in order to take care and account for the different bubble sizes, their coalescence and breakup, the population balance approach known as homogeneous “MUltipleSIze Group” (MUSIG) model as presented in Eq. 40 was used in this study. With this model, the dispersed bubbles were divided into M bubble size groups where inter and intra class bubble coalescence and breakup occur. The homogeneous MUSIG model assumes that there is no slip velocity between bubbles in different size groups, so that all bubble groups have the same velocity5,9,11,40,45. In Eq. 40 and Eq. 41, fi is the size fraction of the ith bubble class, BC represents production (birth) of larger bubbles through coalescences of smaller ones, BB represents production (birth) of a smaller bubbles through breakup of larger bubbles, DC represents loss (death) of bubbles through coalescence, DB represents loss (death) of larger bubbles through breakup.

The bubble breakup and coalescence models used in this study were those of Luo and Svendsen, and Prince and Blanch, respectively35,46. Details on these and other models for breakup and coalescence can be found in the studies of Liao et al.47, Liao et al.48 and Yeoh et al.9.

Experimental facility

The experimental data used for validation of the results of this numerical study was not directly conducted as part of this study but was obtained from experimental investigations previously conducted by Lucas et al.1 and Monrós-Andreu et al.2. A summary of the experimental investigation, including simplified schematics of their experimental setups and experimental details are outlined in this study to help enhance readability and provide further clarity.

Experimental facility of MTLoop

The facility consisted of a circulation loop with the test section comprising a cylindrical pipe with an internal diameter of 51.2 mm and an effective vertical test section approximately 3030 mm high (Fig. 1). The facility could be operated either with air–water mixture at a constant temperature or with steam–water mixture at a pressure of up to 2.5 MPa and a maximum temperature of 225 °C. In order to vary the air volume flow rate, the air supply of the system was fed into the test section through four separate lines. Each line was designed for a specific range of volume flow rates to enable accurate control of the airflow over the entire range. A wire-mesh sensor was used for data gathering and further analysis.

The volume flow rates were controlled by an ultrasonic flow meter for the water and hot wire flow rate sensors for the air. Air injection was performed using a special sparger with 19 capillaries evenly distributed across the cross-section of the pipe. The sparger scheme enables varying the initial bubble sizes and the radial position of the injected bubbles. In cases of low gas volume flow rates, some capillaries were switched off to ensure a symmetric injection of bubbles1,46,49. It is worthy of note that, although the study did not explicitly highlight experimental uncertainty in sensor measurements and instrument tolerances, this study assumes all uncertainties are within the expected ranges for all devices used in the experimental study. The test cases used in the current study correspond to the situation where the loop was operated with an air-water mixture at atmospheric pressure and a temperature of 30 °C. The superficial velocities for the test cases used to obtain the experimental data for validation of the numerical results in this study are presented in Table 1.

A simplified schematic of the experimental facility used to obtain MTLOOP data set1.

Experimental facility of Monrós-Andreu et al.2

The experimental facility of Monrós-Andreu et al.2 was for studying the effects of temperature variation in bubbly and bubbly to slug transition. The experiments were carried out in an upward air–water flow system (Fig. 2). The test section consisted of a transparent pipe of internal diameter 52 mm and a height of 5500 mm. The local flow measurements using a four-sensor conductivity probe were carried out at axial locations of 1166 mm (Low port, L/D = 22.4), 3176 mm (Mid port, L/D = 61), and 5131 mm (Top port, L/D = 98.7). It is assumed experimental uncertainty of this study is within the range expected for four sensor conductive probes. The water was circulated in the loop by a pair of centrifugal pumps. The air was introduced into the test section through a sparger located at the base of a mixing chamber.

Pressure transducers and temperature sensors were installed to measure the pressure and temperature of both phases. The superficial velocity of the liquid phase was measured using a magnetic flow meter at the inlet of the test section. The injected air superficial velocity was measured and controlled with a Bronckhorst EL-FLOW flow controller. To control the water temperature, a heat exchanger was used to maintain constant temperatures in the range of 15–37 °C. The interfacial area concentration, void fraction, and bubble chord length were measured using a four-sensor conductivity probe. A Laser Doppler Anemometry (LDA) was used to measure the liquid velocity and turbulent kinetic energy. The superficial velocities for the test cases used in this study are presented in Table 2.

A simplified schematic of the experimental facility used to obtain the data set by Monrós-Andreu et al.2.

Numerical modelling

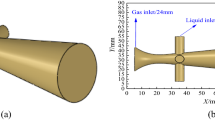

Numerical calculations were performed through the use of the commercial CFD software, ANSYS CFX14.535 within the Eulerian-Eulerian two-fluid model framework. For pipe flows, radial symmetry could be set so that numerical calculations are done on a sector of the pipe in order to reduce calculation time. Various symmetries including 60 degrees34,40,46,50 and 5 degrees25,37,39,40 have been used and similar results were reported. This study also took advantage of the radial symmetry of pipe flows so that numerical calculations could be done on a 5-degree radial sector of the pipe, where symmetry boundary conditions were set for both vertical sides of the computational domain.

For the inlet boundary condition, gas volume fraction profile, gas velocity profile and superficial liquid velocity were specified at L/D = 2.5 for the MTLoop and L/D = 22.4 for the Monros setup. For both setups, the outlet was set to atmospheric pressure and on the walls, a non-slip boundary condition was set for the liquid phase and a free-slip for the gas phase. Turbulence of the liquid phase was modelled using Menter’s k-ω based shear stress transport (SST) model. The turbulence of the gas phase was modelled using the zero-equation turbulence model and turbulence transfer was considered according to Sato’s model. The number of bubble size groups implemented in the MUSIG model was 10. The bubble breakup model of Luo and Svendsen was used with the breakup coefficient set to 0.2 instead of the default value of 1. The bubble coalescence was modelled according to the model of Prince and Blanch35,46 and a value of 0.05 was used for both the buoyancy and turbulence coalescence coefficients.

Grid dependence study and selection

To ensure the accuracy and validation of the numerical results in this study, a grid independence study was conducted. The grid-independent approach also guarantees the selection of the optimal number of grids that minimizes computational time and cost. Hexahedral meshing was applied to the test section in this study. In all the simulations, a convergence criterion based on a root mean square residual of 1 × 10−4 was set for terminating the numerical calculations. Table 3 shows the number of grid elements based on the radial, axial, and total grid elements on the domain test section under the Hexahedral mesh configuration. The selection of grids was aimed at increasing from coarse to finer grid sizes to assess numerical solution stability and consistency. The experimental MTLoop test case 118 (bubble flow) was considered for only the Grace et al.3 model, as it was assumed that the optimal grid elements would also perform well under other models considered in this work.

Figure 3a presents typical results of the radial gas volume fraction for the various cases of grid refinements based on theGrace et al.3 Model. Case 3 provides an excellent match with experimental case 118. Figure 3b indicated that Case 3 was established as the optimal since it gives adequate MSE below the 10−4 under the hexahedral mesh with 27 uniform radial elements and 331 uniform axial elements.

(a) Grid independent study on the gas volume fraction results based on the Grace et al.3 model for varied cases of grid elements, (b) Mean Squared Error (MSE) for each case relative to the experimental test 118.

Results and discussion

The simulation results presented only differ in the drag coefficient models used, while the expression for the drag force remains unchanged. The model coefficients of some of the non-drag forces used to aid in the investigation of the drag coefficient models considered were slightly modified as indicated in the next section. The simulated results were compared with the experimental data at L/D = 59.2 and 98.7 for the MTLoop andMonrós-Andreu et al.2 data, respectively. For the context of this study, radial position between 0 and 20 mm is considered as the core region and 20 to 25 mm is considered the wall region. Additionally, for conciseness, the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) metric is used as the main error metric for contextual discussions. However, all other computed error metrics are presented in Tables 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11.

Models compared on MTLoop data

The effects of the drag coefficient models on the simulation for gas volume fraction are shown in Fig. 4(a-f). The wall lubrication force used for test cases experiment (083) and experiment (118) was based on the work of41. However, when this model was used for the test case 039, all the drag coefficient models highly underpredicted the experimental data. To correct this, theFrank et al.42 wall lubrication force model was used for test case experiment (039), with a slight modification to the power law index from the default value of 1.7 to 1.3. Similarly, the turbulence dispersion coefficient of 0.5 was used for all test cases instead of the default value of 1. Modification of model coefficients is done to enable better prediction of the experimental data.

For test case experiment (039) (depicted in Fig. 4a and b), the trend of the gas volume fraction distribution in the core region of the pipe was generally captured satisfactorily by 5 out of the 6 drag models investigated. The least performing model for this test case was the model by Schiller-Naumann51, which predicted the core region void fraction with an MAPE of 9.68%. The maximum MAPE of the other 5 drag models was 7.54% (by37. A close look at the trends unveils that the majority of the errors in prediction within the core region was due to failure of the models to accurately predict void fractions at the center of the pipe (within radial position of (0 to 5 mm). Additionally, prediction errors became increasingly high towards the wall of the pipe (20–20 mm). None of the investigated models could accurately mimic the trend or predict the experimental data near the pipe walls. MAPE of all models at the wall region for test case experiment (039) ranged between 8.91 and 17.95%. This could be a result of the models perceiving a higher wall lubrication force near the wall. In general, all the models slightly under-predicted the experimental data, except the model of Schiller-Naumann51, which over-predicted it in the wall and core regions. The model ofGrace et al.3 (MAPE: 5.31%) showed the most superiority in predicting the experimental gas volume fraction for this test case, followed closely bySimonnet et al.4 (MAPE:6.46),Ishii et al.36 (MAPE:6.87%), andTomiyama et al.27 (6.97%). The models byGrace et al.3 andTomiyama et al.27 were formulated for dilute systems, where the gas volume fraction is low35, which is also the case for the test case experiment (039). TheSimonnet et al.4 model, on the other hand, was calibrated to account for the local gas volume fraction, which may have improved its ability to predict the experimental gas volume fraction more accurately.

The performance of the drag coefficient models in predicting the experimental gas volume fraction for test case experiment (083) shown in Fig. 4c and d appeared to be better than that for test case experiment (039) based on both prediction error estimations and actual-prediction trending matchings. Similar to test case experiment (039), 5 out of the 6 drag models, with the exception of Schiller-Naumann51 model, were able to match the trend of the experimental data in the core region. The models by Grace et al.3, Behzadi et al.37, Ishii et al.36, Tomiyama et al.27 and Simonnet et al.4 predicted the experimental data at an MAPE of 2.57%, 2.67%, 2.67%, 2.89%, and 2.98% respectively, while Shiller Naumann model predicted the experimental data with MAPE of 6.08%. Notably, the issue of prediction errors within 0 to 5 mm radial position was not observed for test case experiment (083). Despite the good performance of the models in predicting gas volume fraction within the core region, the predictive performance near the wall was relatively poor, with MAPE ranging between 12.14% for Behzadi et al.37 model and 29.17% for Schiller Naumann51 model.

A performance improvement was observed for the test case experiment (118). All models captured the experimental gas volume fraction distribution trend in the core region very well, except theBehzadi et al.37 model (Fig. 4e and f). Aside fromBehzadi et al.37 model, the worst-performing model for this test case in the core region was theSimonnet et al.4 model, which yielded an MAPE of 3.47%. However, the models did not show a significant difference in capturing the experimental data, except for the model byBehzadi et al.37 (MAPE: 11.48%), which underpredicted the core peak. This is possibly because the model ofBehzadi et al.37 was formulated for studying bubble flow regimes where the dynamics in the flow field remain steady. From the test matrix, the flow field of test case experiment (118) might not exhibit completely steady bubble flow behaviour. The performance of all the models in the wall region was relatively poor as shown in Table 6.

Models compared toMonrós-Andreu et al.2 Data

The ability of the drag coefficient models in predicting the gas volume fraction profile of the experimental data of Monrós-Andreu et al.2 is presented in Fig. 5a-j. The models accurately captured the experimental gas volume fraction profile in the core region for the test case VL05JG005TA (Fig. 5a and b). The performance of the models in terms of MAPE numeric ranged between 2.3% and 6.94%. Prediction performance of the models for this dataset was relatively better, compared to the MTLoop dataset. Additionally, there was no prediction issues observed within the center of the pipe and the experimental data was well predicted by all models except that of Schiller-Naumann51, which slightly overpredicted the data near the wall.

The experimental data for the test case VL05JG010TA (Fig. 5c and d) were not well predicted by the models compared to those for the test case VL05JG005TA. The best performing model in the core region wasBehzadi et al.37 with a performance of 5.85% and followed closely byIshii et al.36 model (6.21%). All other models had MAPE greater than 9%. For the wall region, onlySimonnet et al.4 andTomiyama et al.27 models were able to predict the experimental data closely (MAPE: 5.4% and 7.2% respectively). All other models performed relatively poor with MAPE greater than 13. The relatively poor performance can be attributed to the fact that this test case exhibits a transition regime. Additionally, in terms of trend, all the models were able to capture this transition phenomenon favourably.

For test case VL10JG005TA, the performance of the models in the core region had an improvement, compared to test case VL05G005TA (Fig. 5e and f). All the models predicted the experimental data in the core region with an MAPE within 4–6%. The performance of the models was even better within the wall region (MAPE: < 4.5%), with the exception of Schiller-Naumann51 model which slightly overpredicted the experimental data (MAPE:11.5%). However, it is worth noting that all models were able to closely match the trend of void fraction distribution at almost all radial positions within the pipe. The good performance of all models in the core region was also observed for test case VL10JG010TA (Fig. 5g and h). All models closely matched the trend of the experimental void fraction distribution with an MAPE ≤ 4.5%. However, the relatively good performance of all models did not quite transition to the wall region as MAPE of prediction was relatively high as shown in Table 10. The model ofTomiyama et al.27 was the best performing model in terms of predicting the experimental data within the wall region.

For the final test case ofMonrós-Andreu et al.2 data, test case VL10JG030TA (Fig. 5i and j), significant differences were observed in the performance of almost all the models investigated. All the models except that ofSimonnet et al.4 clearly underpredicted the experimental data of this test case within the core region. The best performing model, Simonnet et al.4 model, predicted the data with an MAPE of 3.31%. All other models had MAPE within 18–20%. The better performance of theSimonnet et al.4 model on this data may be because the model was calibrated to take into account the local volume fraction. While the rest of the models were formulated for isolated or single bubbles, except in the case of Ishii et al.36, the area-averaged volume fraction was taken into consideration. Within the wall region, all models performed poorly by overpredicting the experimental data near the wall (MAPE: 17.69% − 60.62%). The general observation is that, for the experimental data of Monrós-Andreu et al.2, the prediction capacity of the models decreases as the superficial velocity of the gas increases. This could probably be because as the gas superficial velocity increases, the flow becomes more turbulent and transitions from bubbly flow towards slug and churn flow, which are more difficult to predict.

Comparison of drag coefficient models on radial gas volume fraction profile for Monrós-Andreu et al.2 data (a) VL05JG005TA (b) VL05JG010TA (c) VL10JG005TA (d) VL10JG010TA (e) VL10JG030TA.

Conclusion and recommendations

The selection of appropriate interface force models, particularly the drag in simulating gas-liquid two-phase flow systems, is crucial for obtaining meaningful results. Several drag coefficient models have been numerically investigated in this study to assess their relative capabilities in simulating upward gas-liquid flow conditions of industrial relevance. The models were validated with experimentally measured profiles of gas volume fraction from the experimental works of Lucas et al.1 and Monrós-Andreu et al.2. Generally, all the models exhibited relatively different performance depending on the test case considered. The performances of the models were assessed by using Mean Absolute Percentage Error as the main error parameter. Additional error parameters were also estimated and summarized in the study for future comparisons, analysis and selections.

A critical analysis of the results and trend visualization of the data revealed that, for experimental data obtained from Lucas et al.1 studies, the model of Grace et al.3 was consistently either the best performing model or among the best performing models for predicting gas volume fraction within the core region of the pipe. The worst performance of Grace et al.3 model produced a mean absolute percentage error of 5.3%. Additionally, for all Lucas et al.1 dataset, the performance of all the models within the core region was better than the region of the pipe. No model was able to accurately predict gas volume fractions within MAPE less than 8.5% within the wall region for all the datasets obtained from Lucas et al.1.

The performance of the models was also relatively different for all models depending on the test case data ofMonrós-Andreu et al.2 considered. However, the performance of the models in predicting gas volume fractions within the wall region for test cases ofMonrós-Andreu et al.2 was way better than what was observed when the models were compared against Lucas et al.1 data set. For the core region of these datasets, all models performed relatively better with an MAPE of 5% or less in 3 out of the 5 experimental datasets. The other two datasets involved possible high gas flow rates and transition regimes which accounts for the relatively poor performance of the models. By just visualization, the models ofGrace et al.3, Behzadi et al.37 andIshii et al.36 showed more consistency in predicting the experimental data better than the other models. TheSimonnet et al.4 model predicted the test case VL10JG030TA remarkably better than the other models. As the superficial velocity of the gas increases, the predictive capabilities of the models decrease. Lastly, all the models predicted the data at the core better than near the wall of the pipe.

The gas-liquid flow conditions in industrial systems for a particular process unit can vary across all flow regimes for upward co-current flow. However, the flow conditions considered in this study were all bubbly flows. It is therefore suggested that a similar study be conducted using data from other flow regimes. This study assumed fully developed flow conditions where void fraction profiles are governed by a balance of lateral forces (mainly, wall lubrication and lift forces) acting on the bubbles. However, current drag models have been developed by considering the movement of bubbles in quiescent liquid. This means that if the drag model is not well formulated, the overall accuracy of the numerical calculation will be affected. Hence, there is a need for more research into the formulation of drag models which consider the motion of all the fluids in order to provide more accurate numerical results.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Lucas, D., Krepper, E. & Prasser, H. M. Development of co-current air-water flow in a vertical pipe. Int. J. Multiph. Flow. 31 (12), 1304–1328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmultiphaseflow.2005.07.004 (2005).

Monrós-Andreu, G. et al. Water temperature effect on upward air-water flow in a vertical pipe: local measurements database using four-sensor conductivity probes and LDA. EPJ Web Conf. 45, 01105. https://doi.org/10.1051/epjconf/20134501105 (2013).

Grace, J. R., Wairegi, T. & Nguyen, T. H. Shapes and velocities of single drops and bubbles moving freely through immiscible liquids. Trans. Inst. Chem. Eng. 54 (3), 167–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408347.2020.1820851 (1976).

Simonnet, M., Gentric, C., Olmos, E. & Midoux, N. Experimental determination of the drag coefficient in a swarm of bubbles. Chem. Eng. Sci. 62 (3), 858–866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ces.2006.10.012 (2007).

Cheung, S. C. P., Yeoh, G. H. & Tu, J. A review of population balance modelling for isothermal bubbly flows. J. Comput. Multiph. Flows. 1 (2), 161–199. https://doi.org/10.1260/175748209789563928 (2009).

Agyei, E., Sarkodie, K., Ribeiro, J. X. F. & Abdulkadir, M. Novel investigation of Taylor bubble and entrained bubbles fractions using Non-Intrusive optical sensors in a concurrent upward slug flow in pipes. Flow Turbul. Combust. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10494-025-00688-x (2025).

Zhang, D. ‘Eulerian modeling of reactive gas-liquid flow in a bubble column’, (2007).

Li, C. ‘Numerical Study of Isothermal Gas-liquid Two-phase Bubbly Flow’, (2011).

Yeoh, G. H., Cheung, S. C. P. & Tu, J. Y. On the prediction of the phase distribution of bubbly flow in a horizontal pipe. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 90 (1), 40–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cherd.2011.08.004 (2012).

Dutta, B. Principles of Mass Transfer and Separation Processes (PHI Learning Private Limited, 2009).

Deju, L., Cheung, S. C. P., Yeoh, G. H. & Tu, J. Y. Capturing coalescence and break-up processes in vertical gas-liquid flows: assessment of population balance methods. Appl. Math. Model. 37, 18–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apm.2013.03.063 (2013).

Khan, K. I. ‘Fluid dynamic modelling of bubble column reactors’, [Online]. (2014). Available: https://iris.polito.it/handle/11583/2528494?mode=simple.6182#.YGnYUegzaM8

Azimi Yancheshme, A., Zarkesh, J., Rashtchian, D. & Anvari, A. CFD simulation of hydrodynamic of a bubble column reactor operating in Churn-Turbulent regime and effect of gas Inlet distribution on system characteristics. Int. J. Chem. Reactor Eng. 14 (1), 213–224. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijcre-2014-0178 (2016).

Chen, P. ‘Modeling the Fluid Dynamics of Bubble Column Flows’, (2004).

Benitez, J. Principles and modern applications of mass transfer operations. 57 11. https://doi.org/10.1002/aic.12641 (2009).

Ziegenhein, T., Lucas, D., Rzehak, R. & Krepper, E. ‘Closure relations for CFD simulation of bubble columns, 8th International Conference on Multiphase Flow’, in Icmf 2013, pp. 1–12. (2013).

Ekambara, K., Nandakumar, K. & Joshi, J. B. CFD simulation of bubble column reactor using population balance. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 47 (21), 8505–8516. https://doi.org/10.1021/ie071393e (2008).

Yeoh, G. H. & Tu, J. Y. ‘Modelling bubbly flows’, in 15th Australasian Fluid Mechanics Conference, pp. 257–268. (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-0938-3_24

Cheung, S. C. P., Yeoh, G. H. & Tu, J. Y. On the numerical study of isothermal vertical bubbly flow using two population balance approaches. Chem. Eng. Sci. 62 (17), 4659–4674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ces.2007.05.030 (2007).

Askari, E., Proulx, P. & Passalacqua, A. Modelling of bubbly flow using CFD-PBM solver in openfoam: study of local population balance models and extended quadrature method of moments applications. Chem. Eng. 2 (1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemengineering2010008 (2018).

Sun, X., Kim, S., Ishii, M. & Beus, S. G. Modeling of bubble coalescence and disintegration in confined upward two-phase flow. Nucl. Eng. Des. 230, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nucengdes.2003.10.008 (2004).

Swearingen, A., Schlegel, J. P. & Hibiki, T. Effect of interfacial area modeling method on interfacial drag predictions for two-fluid model calculations in large diameter pipes. Nucl. Eng. Des. 404, 112180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nucengdes.2023.112180 (2023).

Ishii, M. & Hibiki, T. Thermo-Fluid Dynamics of Two-Phase Flow, no. 1. (2000).

Lote, D. A., Vinod, V. & Patwardhan, A. W. Comparison of models for drag and non-drag forces for gas-liquid two-phase bubbly flow. Multiph. Sci. Technol. 30 (1), 31–76. https://doi.org/10.1615/MultScienTechn.2018025983 (2018).

Yamoah, S., Martínez-Cuenca, R., Monrós, G., Chiva, S. & Macián-Juan, R. Numerical investigation of models for drag, lift, wall lubrication and turbulent dispersion forces for the simulation of gas-liquid two-phase flow. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 98, 17–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cherd.2015.04.007 (2015).

Lucas, D., Krepper, E. & Prasser, H. M. Use of models for lift, wall and turbulent dispersion forces acting on bubbles for poly-disperse flows. Chem. Eng. Sci. 62 (15), 4146–4157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ces.2007.04.035 (2007).

Tomiyama, A., Kataoko, I., Zun, I. & Sakaguchi, T. ‘Drag coefficients of single bubbles under normal and micro gravity conditions’, JSME International journal, vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 472–479, [Online]. (1998). Available: http://www.mendeley.com/research/geology-volcanic-history-eruptive-style-yakedake-volcano-group-central-japan/

Pang, M. J. & Wei, J. J. Analysis of drag and lift coefficient expressions of bubbly flow system for low to medium Reynolds number. Nucl. Eng. Des. 241 (6), 2204–2213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nucengdes.2011.03.046 (2011).

Tabib, M. V., Roy, S. A. & Joshi, J. B. CFD simulation of bubble column-An analysis of interphase forces and turbulence models. Chem. Eng. J. 139 (3), 589–614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2007.09.015 (2008).

Besagni, G., Guedon, G. R. & Inzoli, F. Annular gap bubble column: experimental investigation and computational fluid dynamics modeling. J. Fluids Eng. 138 (1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4031002 (2016). Transactions of the ASME.

Hjertager, B. H. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) analysis of multiphase chemical reactors. Trends Chem. Eng. 4, 45–91 (2016).

Maliska, C. & Da Silva, A. ‘Interface Forces Calculation for Multiphase Flow Simulation’, in EBECEM-1o Encontro … pp. 28–29. [Online]. (2008). Available: https://www.labsolar.ufsc.br/disciplinas/emc6232/arquivos/pdf/palestras/Maliska.pdf

Rzehak, R., Krauß, M., Kováts, P. & Zähringer, K. Fluid dynamics in a bubble column: new experiments and simulations. Int. J. Multiph. Flow. 89, 299–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmultiphaseflow.2016.09.024 (2017).

Cheung, S. C. P. et al. ‘Modelling of polydispersed flows using two population balance approaches’, in AIP Conference Proceedings, pp. 809–814. (2010). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3366467

ANSYS-CFX ‘ANSYS CFX 14.5 Solver Theory Guide’, https://ansyshelp.ansys.com/public/Views/Secured/corp/v251/en/pdf/Ansys_CFX-Solver_Modeling_Guide.pdf

Ishii, M. & Zuber, N. Drag coefficient and relative velocity in bubbly, droplet or particulate flows. AIChE J. 25 (5), 843–855. https://doi.org/10.1002/aic.690250513 (1979).

Behzadi, A., Issa, R. I. & Rusche, H. Modelling of dispersed bubble and droplet flow at high phase fractions. Chem. Eng. Sci. 59 (4), 759–770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ces.2003.11.018 (2004).

Rosa, L. M. et al. Influence of interfacial forces on the mixture prediction of an anaerobic sequencing batch reactor (ASBR). Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 32 (2), 531–542. https://doi.org/10.1590/0104-6632.20150322s00003300 (2015).

Sari, S., Ergün, Ş., Barik, M., Kocar, C. & Sökmen, C. N. Modeling of isothermal bubbly flow with interfacial area transport equation and bubble number density approach. Ann. Nucl. Energy. 36 (2), 222–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anucene.2008.11.016 (2009).

Liao, Y., Lucas, D., Krepper, E. & Schmidtke, M. Development of a generalized coalescence and breakup closure for the inhomogeneous MUSIG model. Nucl. Eng. Des. 241 (4), 1024–1033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nucengdes.2010.04.025 (2011).

Antal, S. P., Lahey, R. T. & Flaherty, J. E. Analysis of phase distribution in fully developed laminar bubbly two-phase flow. Int. J. Multiph. Flow. 17 (5), 635–652. https://doi.org/10.1016/0301-9322(91)90029-3 (1991).

Frank, T., Shi, J. M. & Burns, A. D. ‘Validation of Eulerian multiphase flow models for nuclear safety application’, in 3rd International Symposium on Two-Phase Flow Modelling and Experimentation Pisa, 22–24 September 2004, 2004, pp. 22–24. [Online]. Available: http://www.drthfrank.de/publications/2004/Frank_Shi_Burns_Pisa_2004d.pdf%5Cnpapers3://publication/uuid/4810DCE1-F17C-41C9-A4A6-7404636B72B6

Burns, A. D., Frank, T., Hamill, I. & Shi, J. M. ‘The Favre averaged drag model for turbulent dispersion in Eulerian multi-phase flows’, in 5th International Conference on Multiphase Flow, pp. 1–17. [Online]. (2004). Available: http://www.drthfrank.de/publications/2004/Burns_Frank_ICMF_2004_final.pdf

Cong, T. & Zhang, X. ‘Numerical study of bubble coalescence and breakup in the reactor fuel channel with a vaned grid’, Energies (Basel), vol. 11, p. 256, (2018). https://doi.org/10.3390/en11010256

Krepper, E., Lucas, D., Frank, T., Prasser, H. M. & Zwart, P. J. The inhomogeneous MUSIG model for the simulation of polydispersed flows. Nucl. Eng. Des. 238 (7), 1690–1702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nucengdes.2008.01.004 (2008).

Frank, T., Zwart, P. J., Krepper, E., Prasser, H. M. & Lucas, D. Validation of CFD models for mono- and polydisperse air-water two-phase flows in pipes. Nucl. Eng. Des. 238 (3), 647–659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nucengdes.2007.02.056 (2008).

Liao, Y. & Lucas, D. A literature review of theoretical models for drop and bubble breakup in turbulent dispersions. Chem. Eng. Sci. 64 (15), 3389–3406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ces.2009.04.026 (2009).

Liao, Y. & Lucas, D. A literature review on mechanisms and models for the coalescence process of fluid particles. Chem. Eng. Sci. 65 (10), 2851–2864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ces.2010.02.020 (2010).

Krepper, E., Lucas, D. & Prasser, H. M. On the modelling of bubbly flow in vertical pipes. Nucl. Eng. Des. 235 (5), 597–611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nucengdes.2004.09.006 (2005).

Li, C., Cheung, S., Yeoh, G. & Tu, J. ‘Influence of Drag Forces on a Swarm of Bubbles in Isothermal Bubbly Flow Conditions’, in 7th International Conference on CFD in the Minerals and Process Industries, pp. 1–6. [Online]. (2009). Available: http://www.cfd.com.au/cfd_conf09/PDFs/053LI.pdf

Schiller, L., Naumann, A., Drag Coefficient, A. & Correlation Z. Vereines Ing., 77, 318–320, (1935).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to respectfully acknowledge the invaluable contributions of the late Simon Adzaglo, whose dedication, insight, and scholarly rigor were instrumental in the development of this manuscript. Simon’s expertise and commitment to advancing research in this field have left a lasting impact on our work and on the academic community. Though he is no longer with us, his memory and influence continue to inspire. This publication is dedicated in part to his legacy. The authors are also very grateful to Dr. Dirk Lucas of Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden–Rossendorf, Institute of Fluid Dynamics, Dresden, Germany for providing the MTLoop data and his invaluable suggestions in the preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kwame Sarkodie, PhD supervised the study. Simon Yao Adzaklo (Late) and Kwame Sarkodie conceived and carried out the main objectives of the research and initial manuscript write-up. Emmanuel Agyei performed data analysis, manuscript writing, editing and reviewing. Stephen Yamoah and Nana Yaw Asiedu contributed to manuscript writing and critical review of the work. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Adzaklo, S.Y., Sarkodie, K., Agyei, E. et al. Investigation of drag models for simulation of gas-liquid two-phase flow systems. Sci Rep 15, 39440 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23038-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23038-3