Abstract

Background Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) is a standard approach for treating locally advanced gastric cancer (GC), but resistance in some patients can result in treatment toxicity and surgical delays without therapeutic benefit. Identifying biomarkers predictive of NAC response is crucial for personalized treatment strategies. This study evaluated circulating microRNAs (miRNAs) as potential biomarkers for NAC response. Materials and methods Plasma samples from 39 GC patients undergoing NAC followed by gastrectomy (NCT04223401) were collected before treatment. Four miRNAs (miR-19a, miR-21, miR-27a, miR-200c) were analyzed via quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. NAC response was assessed in histological specimens using the Becker tumor regression grade (TRG), which classifies patients as Responders (TRG 1–2) or Non-responders (TRG 3). Results Among 39 patients, 20 (51%) were Responders, and 19 (49%) were Non-responders. miR-19a, miR-21, and miR-200c were significantly upregulated in Non-responders (p < 0.05). ROC analysis revealed miR-19a (AUC: 0.693), miR-21 (AUC: 0.700), and miR-200c (AUC: 0.772) as predictive of resistance. Univariate analysis revealed a correlation between higher levels of miR-19a, miR-21, and miR-200c and a low neutrophil count, with increased resistance risk. Multivariate analysis confirmed miR-200c as an independent predictor of resistance (OR: 20.90; 95% CI: 1.54-283.73). Conclusions This pilot study identifies circulating miR-19a, miR-21, and miR-200c as novel biomarkers for poor NAC response in GC, providing a foundation for personalized treatment strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) continues to pose a significant global health challenge, with over one million new cases and approximately 769,000 deaths reported annually, ranking it as the fifth most common and fourth deadliest cancer worldwide1. Despite advancements in treatment modalities, the prognosis for patients, particularly those in advanced stages, remains poor. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) has emerged as a promising therapeutic strategy, aiming to shrink tumors, eliminate micrometastases, and enhance surgical outcomes2,3. Presently, the combination of docetaxel, oxaliplatin, leucovorin, and 5-fluorouracil (FLOT) stands out as the most effective NAC regimen4. However, treatment efficacy varies widely among patients, with up to 40% exhibiting minimal or no tumor regression upon histopathological examination5, leading to compromised long-term outcomes6. The absence of reliable predictive markers poses a considerable challenge in guiding treatment decisions and stratifying patients according to their likelihood of responding to NAC. Consequently, a substantial proportion of patients may undergo ineffective treatment, enduring unnecessary toxicity and potentially delaying radical surgery. Therefore, there is an urgent need for personalized treatment approaches facilitated by the development of biomarkers.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are short noncoding transcripts that post-transcriptionally regulate gene expression via partial base-pairing complementarity to mRNA7. Their regulatory reach encompasses genes implicated in pivotal mechanisms driving chemoresistance, including epithelial-mesenchymal transition, hypoxia, autophagy, apoptosis, and drug efflux8. Remarkably, circulating miRNAs exhibit exceptional stability and can be detected in various bodily fluids such as tissue, urine, saliva, stool, sputum, serum/plasma, and others, positioning them as prime candidates for cancer biomarkers9. Consequently, miRNAs have emerged as promising biomarkers for chemoresistance across different types of cancer10,11,12,13. In the context of GC, miR-19a14, miR-2115, miR-27a16, and miR-200c17 have been implicated in chemoresistance based on findings from both experimental in vitro and in vivo studies, as well as clinical investigations involving patients with metastatic GC. However, it remains uncertain whether these miRNAs could serve as biomarkers for resistance to NAC in GC patients. This pilot study was designed to address this knowledge gap and explore the potential role of miR-19a, miR-21, miR-27a, and miR-200c in predicting NAC efficacy through histological tumor regression assessment.

Methods

Patients and sample collection

The samples were collected from patients who had participated in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) examining the effects of home-based prehabilitation on postoperative complications. Both the protocol18 and the outcomes of the RCT19 have been published previously. For this observational side-study, patients’ clinicopathological characteristics were documented, and baseline blood samples were collected for further miRNA profiling before the patients had received NAC followed by gastrectomy at the National Cancer Institute, Vilnius, Lithuania (2020–2022). Before enrollment in the study, all patients provided written informed consent. Ethical approval of the statement was obtained by “the Vilnius University Regional Bioethics Committee (2020/1–1185-675)”. Ethical guidelines delineated in the Helsinki Declaration of 2013 were followed throughout the course of this study.

NAC treatment with the FLOT (5-fluorouracil, oxaliplatin, leucovorin, and docetaxel) scheme was the predominant treatment method for GC patients. Patients underwent four cycles of FLOT every two weeks before surgery. Following NAC, radical gastrectomy was planned within 4 to 6 weeks. The type and approach of the surgery (open or laparoscopic) were determined at the discretion of the individual surgeon.

Evaluation of response to NAC

Pathological evaluation was conducted at the National Center of Pathology, Vilnius, Lithuania. Final tumor histology was determined, and tumors were staged according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging, 8th edition, providing ypTNM staging. The histological type of tumors was classified in accordance with the WHO Classification of Tumors of the Digestive Tract (2010) and the Lauren classification of gastric carcinoma. All slides were stained with hematoxylin-eosin, with additional immunostaining performed as needed. Immunohistochemistry for HER2 status was conducted concurrently with evaluation for poorly cohesive gastric carcinoma type and signet ring cells. Expert gastrointestinal pathologists reviewed all specimens to assess histologic TRG by Becker8 after NAC in the primary tumor. Based on the Becker TRG score, the patients were grouped into Responders (TRG 1–2) and Non-responders (TRG 3) groups.

Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Blood sample preparation and qRT-PCR

Peripheral venous blood samples were collected before NAC using (Lind-Vac, OÜ InterVacTechnology, Narva, Estonia) vacutainer tubes, centrifuged at 3000 g for 10 min at 4 °C. Subsequently, plasma was separated, aliquoted, and stored at −80 °C until further analysis.

RNA extraction from plasma was carried out using the miRNeasy Serum/Plasma Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Specifically, after the addition of Qiazol reagent and incubation, all samples were supplemented with cel-miR-39-3p exogenous control. The subsequent steps followed the manufacturer’s protocol.

cDNA synthesis was performed using the TaqMan Advanced miRNA cDNA Synthesis Kit (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cDNA reactions were performed using a ProFlex PCR System thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA).

The levels of selected miRNAs (hsa-miR-19a-3p, hsa-miR-21-5p, hsa-miR-27a-3p, and hsa-miR-200c-3p) were determined by qRT-PCR using TaqMan MicroRNA Assays (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) with specific probe IDs: 479,228, 477,875, 478,384, 4,427,975. The qRT-PCR amplification was performed in 96-well plates using the QuantStudio™ 5 instrument (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. An initial analysis of Ct values was conducted on QuantStudio Design and Analysis Software v. 2.5.0. Based on good qRT-PCR practice, each assay was performed with two identical replicates, and the resulting Ct values were subjected to statistical analysis. Additionally, a no-template control was included for each assay to assess the possibility of reaction contamination.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 28.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism version 9.5.1 for MacOS. SPSS was primarily used to analyze all baseline characteristics data, while GraphPad Prism was employed for analyzing miRNA data and creating graphs related to miRNA levels. ROC curves were created using MedCalc Software version 18.2.1. Continuous variables between groups were compared by the Mann-Whitney U test and expressed as median with first (Q1) and third (Q3) quartiles. Categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test or Chi-square test as appropriate and expressed as proportions and percentages.

ROC curves were created to depict the prognostic value of possible resistance to NAC markers. When calculating the Youden index for each miRNA and baseline neutrophil count, the identified cut-off values were used to define higher or lower levels of these markers. While creating ROC curves, different combinations of data were tested to improve model performance. To determine the prognostic factors of resistance to NAC, all potential factors were included in univariate analyses using binary logistic regression. Variables that showed significance in these univariate analyses were then included in subsequent multivariate analysis, also employing binary logistic regression.

Overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) rates were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared between the study groups using the log-rank test. The fold changes in miRNA levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method as described by Livak et al.20.

A summary of the overall study design and workflow is provided in Supplementary Figure S1.

Results

Patients

Between April 13, 2021, and September 22, 2022, a total of 39 GC patients were included in the study (Supplementary Figure S2). Histological analysis of TRG showed that Becker grades 1a, 1b, 2, and 3 were observed in 2 patients (5.1%), 6 patients (15.4%), 12 patients (30.8%), and 19 patients (48.7%), respectively. Based on these results, patients were categorized into Responders (TRG grades 1a, 1b, or 2; n = 20) and Non-responders (TRG grade 3; n = 19). Histological evaluation was performed on tumor specimens obtained at the time of surgery following completion of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Table 1 displays the patient and disease characteristics for the study groups. Both groups were comparable in most baseline characteristics, except that patients in the Non-responders’ group had lower baseline neutrophil counts and higher albumin levels.

Treatment and outcomes

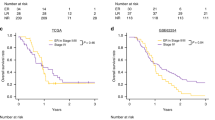

Treatment characteristics are detailed in Table 2. Patients in the Responders (n = 20/20, 100%) and Non-responders (n = 17/19, 89.5%) groups predominantly received FLOT regimen chemotherapy (p = 0.231) with a median number of 4 cycles in both the NAC and adjuvant settings. Both patients diagnosed with stage IV GC in the Responders’ group had only positive peritoneal cytology without other distant metastases, and cytological status has converted after NAC. The type of surgery, postoperative complications and R0 resection rates were similar between the groups. The median follow-up was 26 (22; 32) months after the start of the treatment. Kaplan-Meier analysis showed a trend for higher 3-year OS (89.1% vs. 67.5%; p = 0.098) and DFS (70.0% vs. 52.6%; p = 0.138) for the patients in the Responders’ group, although the differences failed for significance (Fig. 1).

Potential biomarkers for resistance to NAC: plasma MiRNAs level and neutrophile count

Blood samples for miRNA analysis were collected prior to the initiation of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Relative miR-19a, miR-21, and miR-200c levels were significantly upregulated in the blood plasma of Non-responders group (p < 0.05). Descriptive statistics of the analyzed miRNAs between groups are shown in Supplementary Table S1. There were no differences in miR-27a level between groups, thus further analyses did not include this particular microRNA. Furthermore, patients in the non-responders group exhibited decreased neutrophil count before the start of the treatment (Fig. 2).

After identifying potential biomarkers of response to NAC, ROC curves were created to depict prognostic values of plasma miR-19a, miR-21, miR-200c, and baseline neutrophil count for resistance to NAC and to identify the cut-off values for further analysis. ROC analysis revealed sufficient prognostic value of all analyzed plasma miRNAs and baseline neutrophil count, with the best characteristics attributable to miR-200c (Fig. 3; Table 3). Combining biomarkers did not yield any additional prognostic value, as the ROC parameters were comparable to those obtained with individual biomarkers alone (Supplementary Table S2). Additionally, we explored whether circulating miRNA levels varied according to TNM cancer stage. Comparisons between stage groups are summarized in Supplementary Figure S3.

In the univariate analysis higher miR-19a, miR-21, miR-200c levels, and low neutrophil count were significantly associated with the resistance to NAC (Table 3) and were further analyzed and included into the multivariate analysis. Multivariate analysis showed that patients with high levels of plasma miR-200c have higher odds for resistance to NAC (OR: 20.90; 95% CI: 1.54–283.73.54.73), while other biomarkers (higher miR-19a, miR-21 levels and lower neutrophil count) were not predictive for the resistance (Table 4).

Discussion

This pilot study aimed to evaluate the potential of miR-19a, miR-21, miR-27a, and miR-200c as novel biomarkers for predicting resistance to NAC in GC patients. Present findings show that upregulated plasma levels of miR-19a, miR-21, and miR-200c can predict resistance to NAC with sensitivities ranging from 73.6% to 94.7% and specificities from 50.0% to 75.0%. Additionally, a lower neutrophil count was identified as a potential predictor of resistance to NAC as well. Multivariate analysis revealed that patients with high miR-200c plasma level have the highest odds of developing resistance to NAC.

NAC is the current standard for treating locally advanced GC, with the FLOT regimen being the most effective option4. This neoadjuvant approach enables in vivo chemosensitivity testing by assessing TRG in surgical specimens. Despite the use of advanced cytotoxic treatment regimens, approximately half of the patients exhibit minimal or no histological tumor regression following NAC5,21. These patients are known to have significantly worse long-term prognosis6 and thus can be considered resistant to NAC. Consequently, the benefit of NAC for these patients is questionable, as the treatment poses significant toxicity and delays potentially curative surgery. Therefore, the development of novel biomarkers for resistance to NAC is crucial for enhancing GC treatment and enabling treatment personalization.

Emerging evidence highlights the role of miRNAs in chemoresistance22. Additionally, circulating miRNAs show remarkable stability and can be detected in various body fluids, making them attractive biomarkers. The present study provides the first clinical evidence that upregulated levels of miR-19a, miR-21, and miR-200c are associated with resistance to NAC in GC patients. miR-19 is part of the miR-17–92 cluster, known as oncomir-1, one of the most potent oncogenic miRNA clusters23,24. Among the miR-19 family, miR-19a stands out as a prominent oncogenic miRNA. Its oncogenic activity promotes c-MYC-induced lymphomagenesis by inhibiting apoptosis and repressing the tumor suppressor phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN)23,25. Additionally, miR-19a activates the protein kinase B (AKT)-mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway, which functionally antagonizes PTEN to enhance cell survival23,25. The targeting of PTEN by miR-19a, particularly in the context of PTEN/AKT signaling, also contributes to cancer cell resistance to chemotherapeutic agents25,26,27. In the context of GC, miR-19a/b has been shown to promote multidrug resistance in GC cells in vitro by accelerating the efflux of chemotherapeutic drugs and inhibiting drug-induced apoptosis14. These mechanisms of multidrug resistance involve the targeting of PTEN14. Similarly, PTEN is a target of miR-21. A recent study found that M2 macrophages had high levels of miR-21 in both their exosomes and cell lysates. These exosomes can transfer miR-21 to GC cells, leading to cisplatin resistance by suppressing PTEN expression and activating the PI3K/AKT (phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase) signaling pathway, thereby inhibiting cell apoptosis28. In other cancers, miR-21 down-regulates PDCD4 (programmed cell death protein 4) expression, causing paclitaxel resistance in breast cancer29 and 5-FU resistance in colon cancer30. The PDCD4 loss in GC is associated with disease aggressiveness and poor prognosis31, although it’s role in the chemoresistance warrants further investigation. The evidence regarding the role of miR-200c in chemoresistance and its pro/antioncogenic mechanisms is controversial. Lower levels of miR-200c expression have been reported in gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer cell lines and cisplatin-resistant breast cancer cells17,32. The underlying mechanisms involve miR-200c’s ability to inhibit epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)33. Contrarily, miR-200c has been shown to increase sensitivity to cisplatin in GC tissues by targeting and downregulating pr (zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox 2), a transcription factor involved in promoting EMT and drug resistance. On the other hand, miR-200c overexpression has also been reported to induce cisplatin chemoresistance by activating the AKT pathway in esophageal cancer34. Our pilot study showed increased levels of plasma miR-200c in resistant to NAC GC patients, suggesting that miR-200c is related to resistance to NAC in the clinical setting. Our findings are in line with those of Valladares-Ayerbes et al., who reported that circulating miR-200c levels were significantly elevated in gastric cancer patients compared to healthy controls, and that higher miR-200c expression was associated with advanced stage, increased lymph node involvement, and poorer overall and progression-free survival43. These converging lines of evidence strengthen the plausibility of miR-200c as both a prognostic and predictive biomarker in gastric cancer35. In conclusion, the present study confirms previous in vitro findings, demonstrating for the first time in a clinical setting the role of miR-19a, miR-21, and miR-200c to predict chemoresistance in GC patients undergoing NAC.

Moreover, the present study found that a lower neutrophil count at baseline serves as a prognostic marker for chemoresistance in GC patients undergoing NAC as well. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate such findings. Tumor-associated inflammation is linked with systemic inflammation, cancer development, tumor characteristics, and chemosensitivity36,37,38. While the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio has previously been proposed as a marker for poor prognosis and poor response to chemotherapy in various types of cancers39,40,41, this study highlights the specific association between low neutrophil count and chemoresistance. The mechanisms by which neutrophils contribute to chemoresistance are not fully understood. However, recent evidence suggests that neutrophils may play a role through extracellular trap-dependent mechanisms, involving T-cell exhaustion, drug detoxification, angiogenesis, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, and extracellular matrix remodeling42. Although this study only investigated neutrophil count rather than their function, we are not able to explain why a lower count of neutrophils is associated with poor response to NAC.

As a future direction, our research could benefit from computational models that identify miRNA biomarkers in complex diseases. Recent reviews43,44,45 highlight how network-based inference, ensemble learning, and deep learning methods are increasingly applied to integrate miRNA, clinical, and pathological data. Earlier work46 also emphasized that such models accelerate discovery of miRNA–disease associations. Applying these approaches in gastric cancer could improve prediction of chemoresistance by combining circulating miRNA levels with clinical variables, moving biomarker research from descriptive findings toward predictive and personalized applications.

The present study has several limitations that should be considered. First, the relatively small sample size may limit the generalizability and statistical power of the findings. Particularly, we consider, that the lack of power and relatively short follow-up of patients prevented us from showing statistically significant impairment of long-term outcomes in resistant to NAC group despite the clear trend was observed. Second, as a single-center study, there may be biases that limit the applicability of the results to other populations or clinical settings. Third, although miRNA levels were correlated with chemoresistance, tumor tissue and functional experiments to elucidate the precise biological mechanisms behind this association were not included. Similarly, we did not perform experiments to address the underlying biological mechanisms explaining the relationship between low neutrophil count and chemoresistance. Another limitation of this study is that we did not perform functional wet-lab experiments to validate the biological role of the identified miRNAs. Future studies could investigate these miRNAs in gastric cancer cell lines or preclinical models, for example by modulating their expression to assess effects on chemoresistance, apoptosis, and cell proliferation. Despite these drawbacks, this study is the first to demonstrate the role of miR-19a, miR-21, and miR-200c in predicting chemoresistance in GC patients undergoing NAC.

Conclusions

This pilot study for the first time identified circulating miR-19a, miR-21, miR-200c as potential novel biomarkers to predict resistance to NAC in GC patients.

Data availability

The data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Cancer J. Clin. 68 (6), 394–424 (2018).

Cunningham, D. et al. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl. J. Med. 355 (1), 11–20 (2006).

Ychou, M. et al. Perioperative chemotherapy compared with surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma: an FNCLCC and FFCD multicenter phase III trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 29 (13), 1715–1721 (2011).

Al-Batran, S. E. et al. Perioperative chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel versus fluorouracil or capecitabine plus cisplatin and epirubicin for locally advanced, resectable gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (FLOT4): a randomised, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet 393 (10184), 1948–1957 (2019).

Al-Batran, S. E. et al. Histopathological regression after neoadjuvant docetaxel, oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin versus epirubicin, cisplatin, and fluorouracil or capecitabine in patients with resectable gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (FLOT4-AIO): results from the phase 2 part of a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 2/3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 17 (12), 1697–1708 (2016).

Becker, K. et al. Significance of histopathological tumor regression after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in gastric adenocarcinomas: a summary of 480 cases. Ann. Surg. 253 (5), 934–939 (2011).

Bautista-Sánchez, D. et al. The promising role of miR-21 as a cancer biomarker and its importance in RNA-Based therapeutics. Mol. Therapy - Nucleic Acids. 20, 409–420 (2020).

Konoshenko, M. & Laktionov, P. The MiRNAs involved in prostate cancer chemotherapy response as chemoresistance and chemosensitivity predictors. Andrology 10 (1), 51–71 (2022).

Noonan, E. J., Place, R. F. & Li, L. C. MicroRNAs in Predicting Radiotherapy and Chemotherapy Response. In MicroRNAs in Cancer Translational Research [Internet] (ed. Cho, W. C. S.) 415–47 (Springer, 2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0298-1_18.

Zhang, Z. et al. MiRNAs as therapeutic predictors and prognostic biomarkers of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 194 (3), 483–505 (2022).

Cui, E. et al. Serum MicroRNA 125b as a diagnostic or prognostic biomarker for advanced NSCLC patients receiving cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 34 (2), 309–313 (2013).

Just, C. et al. MicroRNAs as potential biomarkers for chemoresistance in adenocarcinomas of the esophagogastric junction. J. Oncol. 2019, e4903152 (2019).

Chakrabortty, A., Patton, D. J., Smith, B. F. & Agarwal, P. MiRNAs: potential as biomarkers and therapeutic targets for cancer. Genes (Basel). 14 (7), 1375 (2023).

Wang, F. et al. MicroRNA-19a/b regulates multidrug resistance in human gastric cancer cells by targeting PTEN. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 434 (3), 688–694 (2013).

Qi, M., Liu, D. & Zhang, S. MicroRNA-21 contributes to the discrimination of chemoresistance in metastatic gastric cancer. Cancer Biomark. 18 (4), 451–458 (2017).

Zhao, X., Yang, L. & Hu, J. Down-regulation of miR-27a might inhibit proliferation and drug resistance of gastric cancer cells. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 30 (1), 55 (2011).

Li, M. et al. MicroRNA-200c reverses drug resistance of human gastric cancer cells by targeting regulation of the NER-ERCC3/4 pathway. Oncol. Lett. 18 (1), 145–152 (2019).

Bausys, A. et al. Personalized trimodal prehabilitation for gastrectomy. Med. (Baltim). 99 (27), e20687 (2020).

Bausys, A. et al. Effect of home-based prehabilitation on postoperative complications after surgery for gastric cancer: randomized clinical trial. Br. J. Surg. 110 (12), 1800–1807 (2023).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta delta C(T)) method. Methods 25 (4), 402–408 (2001).

Bausys, A. et al. Histologic lymph nodes regression after preoperative chemotherapy as prognostic factor in Non-metastatic advanced gastric adenocarcinoma. J. Cancer. 12 (6), 1669–1677 (2021).

Magee, P., Shi, L. & Garofalo, M. Role of microRNAs in chemoresistance. Ann. Transl. Med. 3 (21). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4690999/ (2015).

Olive, V. et al. miR-19 is a key oncogenic component of mir-17-92. Genes Dev. 23 (24), 2839–2849 (2009).

Olive, V., Jiang, I. & He, L. mir-17-92, a cluster of MiRNAs in the midst of the cancer network. Int. J. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 42 (8), 1348–1354 (2010).

Ardizzone, A. et al. Role of miRNA-19a in cancer diagnosis and poor prognosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (9), 4697 (2021).

Xing, S. et al. Deregulation of lncRNA-AC078883.3 and microRNA-19a is involved in the development of chemoresistance to cisplatin via modulating signaling pathway of PTEN/AKT. J. Cell. Physiol. 234 (12), 22657–22665 (2019).

Jiang, X. M. et al. microRNA-19a-3p promotes tumor metastasis and chemoresistance through the PTEN/Akt pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomed. Pharmacother. 105, 1147–1154 (2018).

Zheng, P. et al. Exosomal transfer of tumor-associated macrophage-derived miR-21 confers cisplatin resistance in gastric cancer cells. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 36, 53 (2017).

Tao, L., Wu, Y. Q. & Zhang, S. P. MiR-21-5p enhances the progression and paclitaxel resistance in drug-resistant breast cancer cell lines by targeting PDCD4. neo. ;66(05):746–55. (2019).

Sun, L. H., Tian, D., Yang, Z. C. & Li, J. L. Exosomal miR-21 promotes proliferation, invasion and therapy resistance of colon adenocarcinoma cells through its target PDCD4. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 8271 (2020).

Motoyama, K. et al. Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of PDCD4 and microRNA-21 in human gastric cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 36 (5), 1089–1095 (2010).

Pogribny, I. P. et al. Alterations of MicroRNAs and their targets are associated with acquired resistance of MCF-7 breast cancer cells to cisplatin. Int. J. Cancer. 127 (8), 1785–1794 (2010).

Jiang, T. et al. MicroRNA-200c regulates cisplatin resistance by targeting ZEB2 in human gastric cancer cells. Oncol. Rep. 38 (1), 151–158 (2017).

Hamano, R. et al. Overexpression of miR-200c induces chemoresistance in esophageal cancers mediated through activation of the Akt signaling pathway. Clin. Cancer Res. 17 (9), 3029–3038 (2011).

Valladares-Ayerbes, M. et al. Circulating miR-200c as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for gastric cancer. J. Transl Med. 10, 186 (2012).

Grivennikov, S. I., Greten, F. R. & Karin, M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 140 (6), 883–899 (2010).

Luo, G. et al. Blood neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio predicts survival in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer treated with chemotherapy. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 22 (2), 670–676 (2015).

Aggarwal, B. B., Vijayalekshmi, R. V. & Sung, B. Targeting inflammatory pathways for prevention and therapy of cancer: short-term friend, long-term foe. Clin. Cancer Res. 15 (2), 425–430 (2009).

Guthrie, G. J. K. et al. The systemic inflammation-based neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio: experience in patients with cancer. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 88 (1), 218–230 (2013).

Seah, J. A. et al. Neutrophil-Lymphocyte ratio and pathological response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with Muscle-Invasive bladder cancer. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer. 13 (4), e229–e233 (2015).

Asano, Y. et al. Predictive value of Neutrophil/Lymphocyte ratio for efficacy of preoperative chemotherapy in Triple-Negative breast cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 23, 1104–1110 (2016).

Shahzad, M. H. et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps in cancer therapy resistance. Cancers (Basel). 14 (5), 1359 (2022).

Huang, L., Zhang, L. & Chen, X. Updated review of advances in MicroRNAs and complex diseases: taxonomy, trends and challenges of computational models. Brief. Bioinform. 23 (5), bbac358 (2022).

Huang, L., Zhang, L. & Chen, X. Updated review of advances in MicroRNAs and complex diseases: towards systematic evaluation of computational models. Brief. Bioinform. 23 (6), bbac407 (2022).

Huang, L., Zhang, L. & Chen, X. Updated review of advances in MicroRNAs and complex diseases: experimental results, databases, webservers and data fusion. Brief. Bioinform. 23 (6), bbac397 (2022).

Chen, X., Xie, D., Zhao, Q. & You, Z. H. MicroRNAs and complex diseases: from experimental results to computational models. Brief. Bioinform. 20 (2), 515–539 (2019).

Funding

This project has received funding from the Research Council of Lithuania (LMTLT), agreement No S-MIP-22-30.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concepts: B.B; A.B; R.Sa; S.J. Study design: B.B; A.B; R.Sa; S.J.Data acquisition: B.B; K.B; A.B; K.R; A.Š; R.St. Quality control of data and algorithms: A.B; R.B; R.Sa; S.J.Data analysis and interpretation: B.B; K.R; A.Š; K.Ž; R.St.Statistical analysis: B.B; K.R; K.Ž; R.Sa.Manuscript preparation: B.B; K.B; R.B.Manuscript editing: R.B;; R.Sa; Manuscript review: A.B; S.J.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baušys, B., Rauduvytė, K., Šeštokaitė, A. et al. Circulating miR-19, miR-27a, and miR-200c as novel biomarkers for resistance to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in gastric cancer patients: a pilot study. Sci Rep 15, 39472 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23087-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23087-8