Abstract

This paper focuses on parameter optimization for the actually manufactured test vehicle. This method achieves high-precision, rapid computation of vehicle dynamic performance while fully preserving the strongly coupled nonlinear dynamic properties of the system. Firstly, by employing twin modeling technology, the model accurately reflects the physical dynamic characteristics of the actual vehicle, enabling us to determine how much improvement the optimized vehicle dynamic response will exhibit compared to the current state. Next, a mathematical model for multi-parameter, multi-objective collaborative optimization is constructed using big data search, and key parameters significantly influencing vehicle dynamics are identified through Sobol sensitivity analysis for dynamic optimization. Finally, an improved multi-start parallel simulated annealing algorithm is proposed to enhance the computational efficiency and reliability of the optimization results. The results demonstrate significant improvement in the dynamic performance of the experimental vehicle, validating the effectiveness of the proposed method. This approach overcomes the limitations of traditional linearization treatments, providing a new perspective for dynamic optimization of complex coupled systems and demonstrating significant engineering application value in the field of rail transportation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid development of rail transit technology, the demand for dynamic optimization of vehicle-track coupled systems has become increasingly prominent1. As an interactive system, the parameter matching characteristics between vehicle and track directly affect the system’s vibration response2. Particularly, the suspended monorail system, as a new rail transit mode, exhibits fundamental differences in structural characteristics and operating conditions compared to conventional rail systems3, making existing optimization methods unsuitable and posing new challenges for system dynamics optimization.

Dynamically, the suspended monorail system demonstrates strong multi-parameter coupling4, nonlinearity, fast time-variability and uncertainty5. Therefore, optimizing this strongly coupled system to enhance overall dynamic performance while effectively suppressing bridge vibration has become a critical scientific challenge. Addressing this requires comprehensive consideration of multi-parameter coupling, nonlinear relationships and uncertainties, and developing targeted optimization methods to provide theoretical and technical support for suspended monorail dynamics optimization.

Technical challenges of strongly coupled systems

A strongly coupled system refers to one where there is intense interaction between vibrations in different directions, necessitating consideration of coupled vibration effects and precluding isolated analysis of single-direction characteristics. These characteristics render traditional decoupling methods inadequate for accurately describing their true dynamic behavior6. Secondly, the interactions in strongly coupled systems often display nonlinear characteristics, where input and output are not proportional7,8, leading to exceptionally complex dynamic computations. Their dynamic responses cannot be predicted through linear superposition and may exhibit chaotic9,10, critical, or other complex phenomena, significantly increasing the difficulty of system analysis and solution. Additionally, strongly coupled systems are highly sensitive to parameter variations—minor disturbances can trigger drastic state changes, accompanied by substantial uncertainty, making accurate prediction using simple linear models challenging11,12.

Technical challenges in the dynamic analysis of suspended monorail vehicles

The dynamic analysis of suspended monorail vehicles constitutes a complex multiphysics coupling problem. Primarily, due to the three-directional elastic characteristics of tires and the strongly coupled nature of the system, traditional decoupling methods become inapplicable, necessitating the adoption of more sophisticated coupling analysis approaches. Secondly, the vehicle system contains numerous nonlinear components that render linearization methods ineffective13, particularly under high-speed operation and large displacement conditions where conventional analytical approaches fail to accurately predict true dynamic behaviors14. Furthermore, the analysis process requires simultaneous consideration of coupled multidisciplinary problems spanning macroscopic kinematics, microscopic contact mechanics15, and tribology16. Compounded by random environmental factors such as wind loads and track excitations17,18, the system’s dynamic characteristics become substantially more complex. To accurately compute the vehicle’s dynamic performance, it is imperative to establish high-precision models that integrate multiphysics simulation technologies with experimental data, thereby effectively addressing the system’s nonlinearity, coupling effects, and stochastic phenomena.

Comparative analysis of vibration characteristics in suspended monorail systems and traditional rail vehicles

Conventional rail vehicles use wheelsets with high stiffness and load capacity. Minimal deformation during operation results in small wheel-rail contact areas16, concentrating contact forces. The track’s high rigidity decouples directional deformations, allowing independent vibration analysis. Steel wheel-rail contact is typically modeled as linear elastic19, enabling simplified uncoupled mechanical analysis20.

In contrast, suspended monorails employ rubber tires exhibiting strongly nonlinear, coupled tri-directional (lateral/vertical/longitudinal) elasticity21. Tire deformation depends on contact force, direction, area, and speed22, with directional forces interacting through internal shear23. Speed, temperature, and disturbances further complicate this nonlinear behavior24, necessitating coupled dynamic analysis.

Additionally, on each suspended monorail vehicle, over 20 tires are strategically mounted at distinct positions and oriented in various directions. Each tire exhibits three-dimensional elastic behavior, and the intricate interplay among tire forces significantly amplifies the complexity of vehicle body vibration.

Current research status of vehicle dynamics optimization

Extensive research has demonstrated that optimizing the key dynamic parameters of rail vehicles can significantly enhance their dynamic performance. Current studies primarily focus on the dynamic optimization of conventional railway vehicles, with typical approaches including: establishing a linearized model after decoupling vibrations in different directions25,26, and employing statistical methods to analyze the mapping relationship between decoupled system parameters and optimization objectives27,28,29. However, these traditional methods suffer from low optimization efficiency. To address this, researchers have proposed two improved approaches based on intelligent algorithms: one involves replacing the vehicle dynamic model with a neural network30, while the other entails constructing a dedicated optimization model31,32,33. Note that these optimization methods only apply to weakly coupled vehicle systems, not to strongly coupled ones like monorail vehicles. Current dynamics modeling for strongly coupled vehicles often employs simplified approaches, neglecting their coupling effects34,35,36. Moreover, existing optimization relies mainly on neural network-based linearized surrogate models3.

In existing suspended monorail modeling frameworks, the guide wheel is typically idealized as a horizontal force element, with wheel slipping forces being disregarded. This approach simplifies the model structure to resemble that of conventional rail vehicles but fails to account for the inherent strong coupling of vibrations in all directions.

The improvement in this paper

Compared with conventional railway vehicles, suspended monorail vehicles exhibit significant differences in structural design and operational conditions, with their dynamic systems demonstrating complex characteristics such as strong coupling, nonlinearity, and time-varying behavior. This makes traditional dynamic analysis methods like decoupling and linearization inadequate. In current suspended monorail modeling frameworks, guide wheels are often simplified as horizontal force units, with their slip forces frequently neglected. While this simplification aligns the model structure closer to conventional rail vehicles, it fails to fully account for the inherent strong coupling characteristics of multi-directional vibrations. Existing dynamic optimization methods primarily rely on equivalent vehicle models based on neural network linearization, whereas this study proposes a dynamic computation method based on digital twin technology that more accurately preserves the system’s strong coupling and nonlinearity. Furthermore, for strongly coupled nonlinear vehicle systems, this study innovatively introduces a multi-objective optimization approach integrating digital twin modeling and big data search. During digital twin data training and vehicle optimization, an enhanced multi-start parallel simulated annealing algorithm is employed, significantly improving computational efficiency through multi-thread parallel computing. The multi-start cooperative search strategy effectively expands the solution space, not only avoiding the local optima trap common in traditional single-thread simulated annealing but also enhancing the stability and reliability of optimization results.

Theoretical analysis

Vehicle model

The main structure of the suspended monorail vehicle includes the car body, two bogies, two bolsters, and four suspension beams. As shown in Fig. 1, the vehicle is supported by a combination of driving wheels, guide wheels, and stable wheels. The driving wheels are connected to the gear box via a rotational joint, while the gearbox is linked to the bogies through traction and supporting rubber bushings, which transmit the wheel-rail forces to the bogies. The bolster are positioned at the top of the car body and are connected to the car body by traction rods. The air springs located between the suspension beams and bolsters form the secondary suspension system of the vehicle.

Strong coupling characteristics

Typically, conventional railway vehicles are classified as typical weakly coupled systems because their high-stiffness wheel-rail contact characteristics allow decoupled analysis of vertical, lateral, and longitudinal vibrations37. In contrast, suspended monorail vehicles exhibit significantly strong nonlinear coupling characteristics in their multi-directional vibration systems due to their unique wheel-rail structure. Specifically: the guide wheels and stable wheels operate along the guiding surface of the box-type track beam, while the driving wheels move along the running surface of the track beam. Owing to the coupled nature of the tire’s tri-axial elasticity, vibration energy is transmitted to the car body through the suspension system. This coupling effect inevitably introduces vertical vibration components into the vehicle’s lateral motion, forming a typical strongly coupled vibration system. Consequently, in dynamic analysis, the vertical and lateral vibrations of suspended monorail vehicles cannot be effectively decoupled.

The suspended monorail vehicle dynamics system shown in Fig. 1 demonstrates the following strong coupling characteristics through establishing lateral and vertical dynamic equations for its main components.

The lateral movement of the front bogie is shown as follows:

\({\mathbf{F}}_{{{\mathbf{gzf}}}}\) denotes the radial force vector between the guide wheel and stable wheel of the front bogie; \({\mathbf{F}}_{{{\mathbf{dyf}}}}\) denotes the lateral force vector of the driving wheels on the front bogie; \({\mathbf{K}}_{{{\mathbf{zyyf}}}}\) denotes the stiffness matrix of the force source between the front bogie and the front bolster; \({\mathbf{y}}_{{{\mathbf{zf}}}}\) denotes the lateral displacement matrix of various components within the front bogie; \({\mathbf{y}}_{{{\mathbf{yf}}}}\) denotes the lateral displacement matrix of various components within the front bolster; \({\mathbf{C}}_{{{\mathbf{zyyf}}}}\) denotes the damping matrix of the force source between the front bogie and the front bolster; \({\mathbf{m}}_{{{\mathbf{zf}}}}\) denotes the mass matrix of the front bogie, and \({\mathbf{F}}_{{{\mathbf{zyf}}}}\) denotes the external force matrix acting on the components of the front bogie.

The lateral movement of the rear bogie is shown as follows:

\({\mathbf{F}}_{{{\mathbf{gzr}}}} ,{\mathbf{F}}_{{{\mathbf{dyr}}}} ,{\mathbf{K}}_{{{\mathbf{zyyr}}}} ,{\mathbf{y}}_{{{\mathbf{yr}}}} ,{\mathbf{y}}_{{{\mathbf{zr}}}} ,{\mathbf{C}}_{{{\mathbf{zyyr}}}}\) and \({\mathbf{m}}_{{{\mathbf{zr}}}}\) denote those parameters of the rear bogie.

The lateral dynamics of the front bolster is shown as follows:

\({\mathbf{K}}_{{{\mathbf{ycyf}}}}\) denotes the lateral stiffness matrix between the front bolster and the car body; \({\mathbf{y}}_{{\mathbf{c}}}\) denotes the lateral displacement matrix of the car body; \({\mathbf{C}}_{{{\mathbf{ycyf}}}}\) denotes the lateral damping matrix between the front bolster and the car body; \({\mathbf{m}}_{{{\mathbf{yf}}}}\) denotes the mass matrix of the front bolster; \({\mathbf{F}}_{{{\mathbf{yyf}}}}\) denotes for the matrix of other vertical external forces acting on the front bolster.

The lateral dynamics of the rear bolster is shown as follows:

\({\mathbf{K}}_{{{\mathbf{ycyr}}}} ,{\mathbf{C}}_{{{\mathbf{ycyr}}}} ,{\mathbf{y}}_{{{\mathbf{yr}}}} ,{\mathbf{m}}_{{{\mathbf{yr}}}}\) and \({\mathbf{F}}_{{{\mathbf{yyr}}}}\) denote those parameters of the rear bolster.

The lateral motion of the vehicle body is shown as follows:

\({\mathbf{m}}_{{\mathbf{c}}}\) denotes the total mass of the car body and the suspension beam; \({\mathbf{F}}_{{{\mathbf{cy}}}}\) denotes other lateral external forces acting on the car body.

We obtain the equation for the augmented matrix of the entire system by merging Eq. (1)-(5):

\({\mathbf{F}}_{{{\mathbf{gz}}}}\) denotes the matrix of vertical forces on the guide wheels; \({\mathbf{F}}_{{{\mathbf{dy}}}}\) denotes the matrix of lateral forces on the driving wheels; \({\mathbf{y}}\) denotes the displacement matrix corresponding to each component of the entire system; \({\mathbf{K}}_{{\mathbf{y}}}\) denotes the stiffness matrix corresponding to each component of the entire system; \({\mathbf{C}}_{{\mathbf{y}}}\) denotes the damper matrix corresponding to each component of the entire system; \({\mathbf{m}}\) denotes the mass matrix corresponding to each component of the entire system; \({\mathbf{F}}_{{\mathbf{y}}}\) denotes the external force matrix corresponding to each component of the entire system.

Among them,\({\mathbf{F}}_{{{\mathbf{gz}}}} = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {{\mathbf{F}}_{{{\mathbf{gzf}}}} } & {} & {} & {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {} & {} \\ \end{array} } \\ {} & {{\mathbf{F}}_{{{\mathbf{gzr}}}} } & {} & {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {} & {} \\ \end{array} } \\ {} & {} & {\mathbf{0}} & {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {} & {} \\ \end{array} } \\ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {} \\ {} \\ \end{array} } & {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {} \\ {} \\ \end{array} } & {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {} \\ {} \\ \end{array} } & {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {\mathbf{0}} \\ {} \\ \end{array} } & {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {} \\ {\mathbf{0}} \\ \end{array} } \\ \end{array} } \\ \end{array} } \right],{\mathbf{F}}_{{{\mathbf{dy}}}} = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {{\mathbf{F}}_{{{\mathbf{dyf}}}} } & {} & {} & {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {} & {} \\ \end{array} } \\ {} & {{\mathbf{F}}_{{{\mathbf{dyr}}}} } & {} & {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {} & {} \\ \end{array} } \\ {} & {} & {\mathbf{0}} & {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {} & {} \\ \end{array} } \\ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {} \\ {} \\ \end{array} } & {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {} \\ {} \\ \end{array} } & {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {} \\ {} \\ \end{array} } & {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {\mathbf{0}} \\ {} \\ \end{array} } & {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {} \\ {\mathbf{0}} \\ \end{array} } \\ \end{array} } \\ \end{array} } \right]\)

Similarly, the augmented matrix equation for the vertical direction can be obtained as follows.

\({\mathbf{F}}_{{{\mathbf{gy}}}} ,{\mathbf{F}}_{{{\mathbf{dz}}}} ,{\mathbf{K}}_{{\mathbf{z}}} ,{\mathbf{C}}_{{\mathbf{z}}} ,{\mathbf{F}}_{{\mathbf{z}}}\) and \({\mathbf{z}}\) denote the parameters related to vertical vibrations.

When solving the vehicle dynamics using Eqs. (6) and (7), it is essential to first calculate the forces acting on the tires in all directions. According to the Fiala model, the calculation of the radial force of the tire is as Eq. (8):

\(k_{z}\) denotes the vertical stiffness of the tire, \(\Delta r\) denotes the vertical tire deflection, \(d_{z}\) denotes the vertical damping of the tire, and \(V_{\Delta r}\) denotes the rate of vertical tire deflection.

The calculation of the tire longitudinal force \(F_{x}\) is as follows:

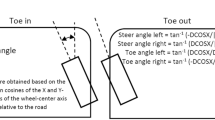

\(s_{x}\) denotes the longitudinal slip, \(c_{x}\) denotes the longitudinal creep stiffness of the tire, and \(sign\) denotes the sign function. The calculations for \(s_{x} ,\mu ,s\) and \(s^{ * }\) are as follows:

\(s_{y}\) denotes Sideslip. \(\mu_{0}\) denotes static coefficient of friction. \(u_{1}\) denotes dynamic coefficient of friction. \(\partial\) denotes slip angle.

The calculation of the tire lateral force \({\text{F}}_{\text{y}}\) \(F_{y}\) is as follows:

The calculations for \(h\) and \(s^{\prime}\) are as follows:

By substituting Eqs. (14) into Eqs. (6) and (7), the expressions represented by Eqs. (17) and (18) are derived.

\({\mathbf{L}}_{{{\mathbf{gzf}}}} ,{\mathbf{L}}_{{{\mathbf{gzr}}}} ,{\mathbf{L}}_{{{\mathbf{dzf}}}}\) and \({\mathbf{L}}_{{{\mathbf{dzr}}}}\) denote the radial force matrix of the guide wheels and driving wheels of the front and rear bogies. The elements of these matrices follow the rule: when tire slip rate \(\left| {s_{y} } \right| < s^{\prime}\),the equation is \(\mu \left( {1 - h^{2} } \right)sign\left( {s_{y} } \right)\); otherwise, it is \(\mu sign\left( {s_{y} } \right)\). \({\mathbf{F}}_{{\mathbf{y}}} = {\mathbf{L}} \circ {\mathbf{F}}_{{\mathbf{z}}}\), where \({\mathbf{L}} \circ {\mathbf{F}}_{{\mathbf{z}}}\) denote the Hadamard product of two matrices, which is the element-wise multiplication.

Specifically:\({\mathbf{F}}_{{{\mathbf{dy}}}} = {\mathbf{L}}_{{{\mathbf{dz}}}} \circ {\mathbf{F}}_{{{\mathbf{dz}}}} .{\mathbf{F}}_{{{\mathbf{gy}}}} = {\mathbf{L}}_{{{\mathbf{gz}}}} \circ {\mathbf{F}}_{{{\mathbf{gz}}}}\).

The main characteristic of a strongly coupled system is the high degree of interdependence among all directions. According to the tire force Eqs. (14), there is a significant correlation between the vertical and lateral forces of the tire, indicating that the vertical, lateral, and longitudinal motions induced by triaxial elasticity are interdependent and interact with each other. Further analysis through Eq. (17) reveals that the lateral motion of the vehicle contains components of vertical motion, indicating that lateral motion (y) is a function of vertical motion (z). Additionally, both Eq. (17) and Eq. (18) include components of the tire’s triaxial elasticity, further demonstrating the strong correlation between them. Therefore, there is a strong coupling relationship between vertical and lateral motions, reflecting the high interdependence and interaction between these two motions. Moreover, when optimizing tire wear based on the wear formula \(WI = \frac{{F_{x} s_{x} + F_{y} s_{y} }}{A}\), the optimization objective also includes expressions for both y and z, further indicating strong coupling among all directions of the suspended monorail vehicle.

Rapidly time-varying and uncertainty characteristics

Track irregularities are commonly characterized by Power Spectral Density (PSD), which depicts the energy distribution at various spatial frequencies, thereby effectively capturing their spatial frequency characteristics. For simulating track irregularities in the time domain, the Monte Carlo method is typically employed to generate time-domain sequences from the PSD. These sequences can then be directly implemented in vehicle simulations to evaluate the vehicle’s stability under different conditions of track irregularities.

The PSD of track irregularity can be expressed as:

\(\Omega\) denotes the wave number, while \(a,\beta\) and \(n\) denote to the roughness coefficients, geometric parameters, and the power distribution parameters of the given PSD curve, respectively.

Figure 2 illustrates different types of road irregularities encountered by the suspended monorail vehicle:

Suspended monorail vehicles experience random time-varying excitations from both track irregularities and wind loads. Beyond uncertain external loads, complex coupling in thin-walled components amplifies system dissipation.

Nonlinear characteristics

Suspended monorail vehicles contain multiple rubber components, which themselves exhibit strong nonlinearity due to the rubber material. Moreover, in this project, the guide wheels of the suspended monorail vehicle are made of solid rubber tires, while the driving wheels use pneumatic rubber tires. Beyond the nonlinearity of the materials, the tire structures themselves also possess strong nonlinear compression characteristics. Additionally, the shock absorbers used in suspended monorail vehicles are often nonlinear components.

Digital twin modeling of suspended monorail vehicles

Digital twin modeling is a technology that maps physical systems to virtual models based on experimental data38. In the field of vehicle dynamics, a real-time data-driven digital twin system enables accurate computation of vehicle dynamic performance. Through simulation-based inference and intelligent optimization algorithms, it generates targeted strategies for enhancing dynamic performance, thereby providing theoretical and technical support for the precise optimization of vehicle dynamic behavior.

In the digital twin modeling process for suspended monorail vehicles, the key steps include constructing blueprint models, collecting Sperling index data from experimental vehicles during operation, and training the blueprint model with this data. By utilizing experimental Sperling index data to train the virtual model, the developed model closely matches the actual operational state of the vehicle, accurately reflecting its dynamic performance and ensuring a precise depiction of the vehicle’s dynamic characteristics.

Blueprint model construction

The topological structure of the suspended monorail vehicle system is shown in Fig. 3.

The physical meanings of force elements are shown in Table 1.

Based on the previously referenced topology diagram, the blueprint model for the suspended monorail vehicle is established as depicted in Fig. 4.

The calculation of sperling index data for the experimental vehicle

The Sperling index data for the suspended monorail vehicle were calculated during experimental vehicle testing. The experimental vehicle is shown in Fig. 5.

Data training

Data training is a critical step in digital twin modeling. This study employs a simulated annealing algorithm to iteratively update the parameter files in the blueprint model. Based on the updated parameters, vehicle dynamics simulations are conducted to obtain vibration acceleration data, from which the Sperling index of the blueprint model is calculated. This index is then compared with the Sperling index obtained from physical vehicle tests to compute the goodness of fit. The iterative process is repeated until the simulated annealing algorithm meets the convergence criteria. Finally, the parameter values, the maximum goodness of fit, and the corresponding the Sperling index are output. The detailed workflow of the digital twin data training is illustrated in Fig. 6.

As illustrated in Fig. 7, the Sperling index of the trained digital twin model is presented and compared with the Sperling index data from the experimental vehicle. The results demonstrate that the Sperling index of the digital twin model aligns closely with that of the experimental vehicle, fulfilling the consistency requirements for the Sperling index training.

Applications and challenges of digital twin models

The current "Design Standard for Suspended Monorail Transportation DBJ51/T099-2018" and "Technical Standard for Suspended Monorail Transportation DBJ41/T217-2019" in China provide only the Sperling index as a quantitative metric for assessing the dynamic performance of suspended monorail vehicles. The model presented in this paper ensures an accurate approximation of both the lateral and vertical Sperling indices at the design speed, making it well-suited to precisely reflect the dynamic performance of suspended monorails. However, the limitations of the digital twin data training approach include the potential for multiple solutions in model parameter training when there are excessive training parameters or insufficient experimental data. Therefore, for more complex systems, it is essential to gather a larger set of experimental data for effective model training.

Mass production of blueprint models

To reduce computation time, this paper employs a multi-process parallel computing approach. During the optimization process, each optimization process is ensured to run independently to avoid interference caused by computations initiated from different processes. Therefore, it is necessary to create multiple blueprint models to facilitate the independent invocation of corresponding simulation instances.

In the dynamic software “UM” (used in this paper), the blueprint model files are typically stored in a folder, including tire files, parameter files, track irregularity files, and vehicle trajectory files. The tire files primarily store the various tire parameters; the parameter files contain the stiffness, damping, and other parameters of the vehicle dynamics model; the track irregularity files store the track irregularity data at the tire-to-track contact points; and the vehicle trajectory files record the vehicle’s running trajectory.

To achieve batch model construction, the initial model is placed in the working folder. A new subfolder is then created within the working folder, and the initial model is copied into this new target folder. Subsequently, through automation scripts or batch processing tools, the path information in the model configuration files within the new folder is updated to ensure that the newly created models match the actual paths of their corresponding folders, shown in Fig. 8.

Mathematical model for multi-parameter and multi-objective optimization

In the process of vehicle dynamics optimization, the established mathematical model aims to systematically modify vehicle dynamics parameters in batch through mathematical methods. Based on these modifications, it calculates key dynamic performance indicators, thereby enabling a comprehensive evaluation of the overall vehicle dynamic behavior.

Parameter batch processing

In the optimization design of complex, strongly coupled systems, parameter batching enhances computational efficiency and accuracy. Through parameter batching, model parameters can be automatically modified, significantly reducing the complexity associated with strong coupling characteristics. This allows researchers to concentrate on analyzing and making decisions based on the results of multi-objective optimization without the need for repetitive, time-consuming manual operations. Furthermore, batching also greatly reduces the risk of human errors, making it an essential tool for efficient scientific computation. The specific steps of parameter batch processing are as follows:

Identify the parameters that influence vehicle dynamics performance, including parameters such as the stiffness of the gearbox bushings, the stiffness and damping of the air springs, and the radial stiffness and damping in the tire data files. Set the correction coefficient for the dynamic parameters as \({\mathbf{x}}\).

Calculate the specific values of the modified dynamic parameters using the correction coefficient \({\mathbf{x}}\). The calculation method is as follows:

\({\mathbf{k}}_{{\mathbf{0}}}\) denotes the original parameters of the vehicle, while \({\mathbf{k}}\) denotes the parameters modified for the vehicle.

The batch processing operation modifies the parameter files and tire data files in the blueprint model, generates updated parameter and tire data files, and invokes dynamics simulation software to perform simulation computations. The data collected during the simulation are stored in a multidimensional array to support subsequent vehicle dynamics performance analysis.

Establishment of multi-objective functions

Constructing the objective function is a core step in optimization problems. The objective function provides a quantitative measure of the system’s dynamic performance, allowing for an intuitive evaluation of optimization outcomes.

Sperling index

The Sperling index \(W\) denotes a measure of passenger comfort on rail vehicles. It is computed by collecting lateral and vertical accelerations in the vehicle’s time domain and processing them through Fourier transformation. It is defined as follows:

In this equation, \(A_{a}\) denotes the acceleration in the frequency domain after amplitude-frequency characteristic transformation, \(f\) denotes the frequency of vibration, and \(F\left( f \right)\) denotes the frequency correction coefficient defined according to the frequency in Chinese standard GB5599-2019.

The frequency correction coefficients for lateral and vertical vibrations are different. For vibrations in the same direction, the correction coefficients vary with different frequencies. Specifically for vertical vibrations:

For the frequency correction coefficients corresponding to lateral acceleration, they are as follows:

Wheel wear

Wheel wear refers to the gradual erosion of rubber wheels on vehicles due to friction and impact with the track during operation. For suspended monorail vehicles, the formula defining the wheel wear of guide wheels and driving wheels is as follows39:

\(F_{x}\) and \(F_{y}\) denote the longitudinal and lateral forces on the wheel, respectively. \(s_{x}\) and \(s_{y}\) denote the longitudinal and lateral slip ratios of the vehicle.\(A_{t}\) denote the contact area between the wheel and the track.

\(H\) denotes the tire width, \(R\) denotes the tire radius, and \(\delta\) denotes the wheel compression amount.

Elastic component stress

Elastic component stress refers to the stress generated in elastic elements when subjected to external forces. The definition of elastic component stress is as follows:

\(F_{s}\) denotes the force acting perpendicular to the cross-section, and \(A_{s}\) denotes the cross-sectional area.

Wheel-rail contact noise

Wheel-rail contact noise refers to the sound generated by the vibrations of the wheels during contact with the track while the vehicle is in operation. According to the energy statistical method, it is derived as follows:

Since the speed of sound waves is much faster than the rate of heat conduction, the process of sound wave propagation can be considered adiabatic. Therefore, the adiabatic state equation for an ideal gas of a given mass can be written as40:

In this equation, \(p,V\) and, \(\rho\) denote the sound pressure, volume, and fluid density, respectively. \(p_{0} ,V_{0}\) and \(\rho_{0}\) denote the total sound pressure, volume, and density at the initial moment. \(\alpha\) is the ratio of the specific heat capacity at constant pressure to the specific heat capacity at constant volume for the gas, which is 1.402 for air.

Rearrange the above Eq. (28) to obtain the relationship between sound pressure and volume change.

The equation relating sound velocity and sound pressure is as follows:

Substituting Eqs. (29) and (30) into Eq. (28) yields the sound pressure.

Convert sound pressure to sound pressure level, defined as the ratio of the root-mean-square sound pressure to the reference sound pressure, expressed in decibels (dB).

\(p_{r}\) denotes the reference sound pressure, typically taken as \(p_{r} = 2 \times 10^{ - 5} Pa\), which is the minimum sound pressure of a \(1KHz\) air sound detectable by the human ear.

Normalization and weighting of the objective function

Since the dynamic performance indicators have different units, they cannot be directly aggregated numerically. Therefore, it is necessary to apply a normalization method to convert these indicators into dimensionless values, eliminating dimensional influences, thereby enabling the comprehensive evaluation of the overall vehicle dynamics. The normalization formulas for each dynamic performance indicator are as follows:

\(W_{y}\) and \(W_{z}\) respectively denote the lateral and vertical Sperling index of the vehicle. \(WI_{k}\) denotes the wear value of wheel numbered \(k\), and \(L_{k}\) denotes the sound pressure level generated by wheel numbered k.\(\sigma_{k}\) denotes stress for the elastic component numbered as the k-th. \(W_{y0} ,W_{z0} ,WI_{0k} ,L_{0k} ,\sigma_{0k}\) denote the initial values of these parameters.

The physical significance of \(g_{i} \left( {i = 1,2,3,4} \right)\) is the ratio of optimized vehicle dynamics indicators to the vehicle dynamics indicators under initial parameter conditions.

The normalized objective functions are used to achieve multi-objective optimization through linear weighting, and the objective function is expressed as:

In this paper, the four metrics of vehicle dynamics are equally important, so the target weights are set to be the same. Therefore, \(w_{i} = \frac{1}{4}\).

Sensitivity analysis

For strongly coupled nonlinear vehicle systems with numerous parameters, global optimization of all dynamic parameters would significantly increase computational costs41. To improve optimization convergence efficiency, parameter sensitivity analysis is required to eliminate non-critical parameters with low contributions to the objective function.

This study employs variance-based Sobol global sensitivity analysis, which uses Monte Carlo sampling to quantitatively assess parameter sensitivity by computing the contribution ratios of input parameters and their interactions to the system output variance. Based on the results, key parameters with significant influence on system performance are identified as optimization variables to achieve efficient parameter optimization.

The sensitivity analysis procedure is as follows:

The number of parameters \(D\) that determine the value of the objective function, with \(n\) being the known number of parameter sample points.

Define the range of parameters.

\({\mathbf{X}}_{{{\mathbf{min}}}} ,{\mathbf{X}}_{{{\mathbf{max}}}}\) denote the lower and upper bounds of the parameter.

\({\mathbf{p}}_{n \times 2D}\) denote the generated Sobol sequence matrix, and based on this Sobol sequence matrix, a matrix \({\mathbf{R}}_{n \times 2D}\) denotes generated. Each element in the matrix is obtained using the following equation:

The first n columns of the matrix \({\mathbf{R}}_{n \times 2D}\) generate the matrix \({\mathbf{A}}\), and the last n columns generate the matrix \({\mathbf{B}}\).

Replace the elements in the i-th column of matrix \({\mathbf{A}}\) with the elements in the i-th column of matrix \({\mathbf{B}}\) to obtain the matrix \({\mathbf{AB}}_{j}^{i}\).

Simulate and compute the objective function values \(Y_{A\_j} ,Y_{B\_j} ,Y_{{AB^{i} \_j}} \left( {i = 1,2, \cdots ,D,j = 1,2, \cdots ,n} \right)\) for each row of matrices \({\mathbf{A}},{\mathbf{B}}\) and \({\mathbf{AB}}^{{\mathbf{i}}}\) by invoking the objective function.

\({\mathbf{Y}}_{{\mathbf{A}}} ,{\mathbf{Y}}_{{\mathbf{B}}}\) and \({\mathbf{Y}}_{{{\mathbf{AB}}^{{\mathbf{i}}} }}\) denote representations of the objective function vectors.

Let \({\mathbf{Y = }}\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {{\mathbf{Y}}_{{\mathbf{A}}} } \\ {{\mathbf{Y}}_{{\mathbf{B}}} } \\ \end{array} } \right]\), \({\text{var}}_{Y}\) denotes the variance of the vector \({\mathbf{Y}}\).

First-order sensitivity indices \(S_{i}\) for sensitivity analysis of each parameter can be calculated using Eq. (48):

Total-effect sensitivity indices \(ST_{i}\) for sensitivity analysis of each parameter can be calculated using Eq. (49).

A sensitivity analysis was performed on 34 parameters to calculate their total-effect indices. After sorting the parameters in descending order (see supplementary table for parameter names and corresponding total-effect indices), a bar chart of the total-effect indices was generated based on the data in this table.

As shown in Fig. 9, the total-effect sensitivity indices of the top 14 parameters are comparatively high. Consequently, these 14 parameters are selected as the focus for optimization. The selected 14 key parameters specifically include: lateral and vertical stiffness of the front bogie gearbox bearing bushings, lateral stiffness and vertical damping of the front bogie air spring, vertical damping of the rear bogie air spring, vertical stiffness of the front bogie guide wheel, vertical stiffness, damping coefficient, and cornering stiffness of the front bogie driving wheel, vertical stiffness and cornering stiffness of the front bogie stable wheel, vertical stiffness of the rear bogie driving wheel, as well as vertical stiffness and cornering stiffness of the rear bogie stable wheel.

Advantages of simulated annealing (SA) algorithm

In engineering optimization design, algorithm selection directly impacts the convergence process and solution quality. Preferred algorithms are selected based on three key criteria: First, Computational efficiency—high-performance algorithms achieve preset accuracy requirements with fewer iterations through improved convergence mechanisms; Second, Optimization robustness—algorithms with global search capability effectively avoid local optima; Third, Engineering applicability—intelligent optimization algorithms achieve optimal balance between accuracy and efficiency for strongly coupled multi-parameter systems. Based on these criteria, Genetic Algorithm (GA) and Simulated Annealing (SA) have become preferred methods for complex engineering optimization problems due to their superior global optimization performance.

This paper takes an objective function that includes 34 parameters (Eq. (50)) as an example, utilizing the Simulated Annealing (SA) algorithm to compute the minimum value of the objective function. It also compares the optimization performance between the Simulated Annealing and the Genetic Algorithm (GA). The objective function is presented below:

Through theoretical analysis and computational testing, the following conclusions were drawn:

Algorithm applicability

The Simulated Annealing (SA) algorithm is suitable for any type of optimization problem, especially demonstrating strong performance in continuous optimization challenges. Conversely, the Genetic Algorithm (GA) is more appropriate for discrete optimization problems. When utilized for continuous optimization problems, the Genetic Algorithm typically necessitates additional modifications, such as real-number encoding, thereby adding to the algorithm’s complexity.

Convergence speed

Based on the comparison of optimization results over time between the Simulated Annealing (SA) algorithm and the Genetic Algorithm (GA) as shown in Fig. 10(a), the Simulated Annealing algorithm reaches convergence in only 0.028349 s, while the Genetic Algorithm takes 1.059630 s. This demonstrates that the Simulated Annealing algorithm is 37.38 times faster than the Genetic Algorithm. This significant speed advantage is primarily because the Genetic Algorithm involves processes such as encoding, decoding, chromosome crossover, and combination, whereas the Simulated Annealing algorithm directly searches in the solution space, avoiding these complex processes and thus significantly reducing computation time.

Convergence stability

As observed from Fig. 10(a), the convergence stability of the Simulated Annealing (SA) algorithm clearly outperforms the Genetic Algorithm (GA).

Fluctuation reasons for the genetic algorithm

The fluctuations in fitness values of the Genetic Algorithm mainly arise from the randomness of its crossover and mutation operations. While this randomness boosts the Genetic Algorithm’s search capabilities, it can also cause instability in fitness values during the convergence process.

Stability reasons for the Simulated Annealing Algorithm

The Simulated Annealing algorithm ensures stability during the convergence process by progressively lowering the temperature and securing more optimal solutions in the current set, thereby preventing significant fluctuations in fitness values.

Result reliability

The Simulated Annealing (SA) algorithm is less prone to getting trapped in local optima compared to the Genetic Algorithm (GA).

Advantages of SA

SA incorporates a temperature-based acceptance probability mechanism. During the high-temperature phase, the acceptance probability is relatively high, allowing the algorithm to explore more solutions across the global search space and effectively escape local optima. As the temperature gradually decreases, the search scope narrows, and the algorithm converges to the global optimum.

Limitations of GA

In the early generations, GA can quickly identify high-fitness individuals through crossover and mutation operations. However, as iterations progress, these high-fitness individuals dominate the population, leading to a loss of diversity. This lack of diversity makes it difficult for GA to escape local optima, resulting in convergence to suboptimal solutions. Figure 10(b) compares GA’s performance in achieving global optima versus being trapped in local optima.

Multi-start parallel simulated annealing algorithm optimization

Traditional Simulated Annealing (SA) performs well in global optimization but has notable limitations. SA is highly sensitive to initial parameters (temperature, cooling rate), where improper settings impair convergence. Although SA can escape local optima, it may still get trapped in complex problems, and its inherent randomness causes solution instability. Moreover, despite the notable enhancement in convergence speed exhibited by the Simulated Annealing (SA) algorithm when compared to the Genetic Algorithm (GA), the optimization process involving SA in a single-threaded mode still incurs substantial time consumption.

To address these issues, we propose Multi-Start Parallel Simulated Annealing (MSSA), which enhances performance by integrating multi-start search with parallel computing. MSSA executes SA processes simultaneously from multiple initial points, expanding search scope and reducing local optima entrapment—making it particularly effective for complex optimization. Parallel computing further improves efficiency by leveraging modern computational resources.

Figure 11(a) illustrates traditional SA’s single-point serial search, while Fig. 11(b) demonstrates MSSA’s multi-point parallel search, significantly increasing the likelihood of finding the global optimum. This approach is especially advantageous for complex problems or scenarios requiring high computational efficiency.

Figure 12(a) presents the complete workflow of a novel strongly coupled nonlinear vehicle dynamics optimization method based on multi-start parallel simulated annealing. Figure 12(b) details the parallel implementation: synchronous initialization of multiple independent initial solutions, parallel simulated annealing execution across computing nodes yielding local optima, with global optimization achieved through a minimum-value selection criterion.

Parallel management strategy

This study designs a multi-start parallel simulated annealing algorithm that employs a parallel strategy based on tensor decomposition and reconstruction. The strategy first decomposes a high-dimensional tensor into several sub-tensors, which are distributed to different processes for parallel computation. Finally, the computational results of the sub-tensors are integrated into a new global tensor. The parallel computing workflow is illustrated in Fig. 8, with the specific steps as follows:

First, a parallel computing pool containing ‘i’ workers is created on the local computing platform to enable multi-process parallel execution. To ensure system robustness, a dynamics software monitoring and forced termination mechanism is implemented: when numerical divergence (such as “rollover” or other abnormal conditions) during simulation prevents the software from exiting automatically, this mechanism forcibly terminates the process and automatically filters out invalid data to prevent contamination of the solution space by abnormal results.

In the parallel computation phase, the initial tensor is decomposed into multiple sub-tensors, each assigned to an independent process for computation. To avoid write conflicts caused by multiple processes simultaneously invoking the dynamics model (i.e., the “baseline model”) to generate output files, the algorithm schedules computation tasks with delayed starts based on sub-tensor numbering sequence. It also monitors the operational status of the dynamics software in each process in real time, thereby preventing conflicts that could arise from simultaneous termination of dynamics computations.

Finally, the dynamics optimization results corresponding to each sub-tensor are integrated and reconstructed into a new global tensor, which serves as the input for the next iteration. This strategy effectively balances parallel efficiency and computational reliability, making it suitable for large-scale complex optimization problems.

Parameter range limitation

Based on the sensitivity analysis results, set the appropriate range for the parameters to be optimized.

\({\mathbf{b}}_{{\mathbf{b}}}\) and \({\mathbf{b}}_{{\mathbf{s}}}\) respectively denote the matrices of minimum and maximum values for parameter ranges, where \(x_{j\min }\) denotes the minimum value of the j-th parameter, and \(x_{j\max }\) denotes the maximum value of the j-th parameter.

Key considerations for parameter selection in simulated annealing

The performance and optimization efficacy of simulated annealing algorithms critically depend on the rational configuration of key parameters, particularly the temperature setting strategy. The initial temperature (\(T_{i}\))must be sufficiently high to ensure the algorithm accepts suboptimal solutions in the early stages, thereby effectively avoiding convergence to local optima. However, excessively high initial temperatures significantly reduce computational efficiency. Therefore, the selection of the initial temperature should balance the algorithm’s exploration capability and computational cost. In this study, the initial temperature was set to \(T_{i} = 100\).

The final temperature (\(T_{e}\))is generally set close to zero to facilitate precise local search in the later stages of optimization. Additionally, supplementary termination criteria, such as a maximum iteration count or stagnation of the objective function value, can be employed. In this research, the final temperature was defined as \(T_{e} = 0.01\).

The cooling rate (\(C_{l}\)) directly influences the algorithm’s search scope and computational overhead. A slower rate expands the exploration space but increases computational burden, with values typically ranging between 0.5 and 0.99. This study adopted a cooling rate of \(C_{l} = 0.9\).

Given the predetermined attenuation function for the temperature control parameter, the Markov chain length (\(L_{k}\)) should ensure that the algorithm attains a state of quasi-equilibrium at each temperature level. In this work, the Markov chain length was set to \(L_{k} = 100\).

Multi-start generation

In low-dimensional spaces (such as two or three dimensions), uniform random sampling can effectively cover the solution space. However, as dimensionality increases, the volume of the space grows exponentially, leading to a rapid expansion of the average distance between sample points. Randomly generated point sets tend to concentrate near the edges and corners of the space, resulting in significant sparsity in the central region. The optimization problem addressed in this study lies in a 14-dimensional space. In such a high-dimensional setting, traditional uniform initial point generation strategies are no longer applicable.

Therefore, this study adopts a random generation strategy to construct initial points. This approach enables broad exploration of the solution space at a relatively low computational cost, effectively mitigating sampling bias issues in high-dimensional settings. The inherent randomness of this strategy is naturally compatible with parallel computing architectures: each independent process can initiate a search from a different starting point, not only maintaining diversity in global exploration but also significantly enhancing the algorithm’s ability to escape local optima. This initialization method, which does not rely on prior knowledge, demonstrates superior applicability and robustness when dealing with black-box optimization problems. The specific method for generating the initial point matrix \({\mathbf{B}}\) is given by Eq. (53).

Matrix \({\mathbf{l}}\) denotes an \(n\)-row by \(j\)-column matrix, with its elements all ranging between 0 and 1.

The specific expression for the initial solution matrix \({\mathbf{B}}\) is shown in Eq. (54).

The element \(x_{nj}\) in the above initial solution matrix \({\mathbf{B}}\) denotes the initial solution of the \(j\)-th parameter in the \(n\)-th generated starting point.

Annealing process in multi-start parallel simulated annealing algorithm

To save time, compute the objective function value in parallel each time. Begin annealing with the temperature set to the initial temperature (\(T = T_{i}\)).

Let \({\mathbf{EC}}\) denote the objective function value matrix for the current solution, and \({\mathbf{EB}}\) denote the objective function value for the best solution. Both \({\mathbf{EC}}\) and \({\mathbf{EB}}\) are \(n\)-row by 1-column matrices, with all elements initially set to positive infinity. Furthermore, let the current solution matrix \(\text{sc}\) \({\mathbf{sc}}\) be initialized as the initial solution matrix \({\mathbf{B}}\) composed of \(n\) starting points, and similarly, let the best solution matrix \({\mathbf{sb}}\) also be initialized as the same matrix \({\mathbf{B}}\). The initialization is expressed as:

Calculate the objective function value matrix corresponding to the current solution matrix, as follows:

\({\mathbf{EC}}\) denotes the current objective function value, where \(ob\) denotes the defined function being optimized.

The new solution matrix \({\mathbf{sn}}\) denotes generated by perturbing the current solution matrix \({\mathbf{sc}}\), with the perturbation method defined in Eq. (58).

Ensuring that parameters remain within specified ranges after perturbation is crucial to meeting practical constraints. Parameters that do not meet these constraints can be handled using penalty functions or correction mechanisms. Through experimental design and validation, it is essential to verify the set parameter ranges and the effectiveness of the optimization algorithm. Statistical analysis of the optimization results is conducted to ensure their reliability and robustness.

Evaluate whether the new solution satisfies the constraint conditions, with the evaluation method shown in Eq. (59):

The corresponding elements in the matrix are:

\(x_{rj} + \Delta x_{j}\) denotes the element in the \(r\)-th row and \(j\)-th column of the new solution matrix, \(x_{rj}\) denoting the solution for the \(j\)-th parameter at the \(r\)-th starting point.

For parameters that do not satisfy the above conditions, correction is applied using the following penalty function:

If \(x_{j\max } < x_{rj} + \Delta x_{j}\) , then set \(x_{j\max } = x_{rj} + \Delta x_{j}\).

If \(x_{j\min }> x_{rj} + \Delta x_{j}\) , then set \(x_{j\min } = x_{rj} + \Delta x_{j}\).

Calculate the objective function value matrix corresponding to the perturbed new solution matrix, shown as follows:

Evaluate whether the new solution is accepted. If \({\mathbf{EN}} < {\mathbf{EC}}\), the new solution is accepted, as follows:

Under the condition \({\mathbf{EN}} < {\mathbf{EC}}\), further evaluate if the new solution is the best solution found so far. Specifically, if \({\mathbf{EN}} < {\mathbf{EB}}\) , then:

Under the condition \({\mathbf{EN}}> {\mathbf{EC}}\), decide whether to accept the probabilistic solution.

In the above expression,\({\mathbf{R}}\) denotes an \(n\)-row by j-column matrix, with its elements all ranging between 0 and 1, and \(T\) denotes the current annealing temperature. If the above condition (Eq. (66)) is satisfied, then:

If \({\mathbf{R}}> e^{{{\mathbf{ - }}\frac{{{\mathbf{EN - EC}}}}{T}}}\), then:

Then, assess whether to repeat the perturbation and acceptance process \(L_{k}\)times at temperature \(T\). If affirmative, continue executing the annealing process; otherwise, continue perturbing the current value.

Finally, evaluate if the temperature \(T\) has reached the termination temperature \(T_{e}\). If true, terminate the algorithm; otherwise, continue the annealing process.

Selection and identification of the optimal solution

Select the minimum value from the optimal solutions and identify the corresponding optimal solution.

\(Ebe\) denotes the ultimate optimization result, specifically the minimum value within the optimal solution, while \({\mathbf{Sbe}}\) denotes the optimal solution corresponding to this minimum value.

Result analysis

Figures 13(a), 14 demonstrates the evolution of the parallel simulated annealing optimization process with five initial points as a function of inverse temperature. Figure 15(a) illustrates that this global optimization algorithm adopts a "better-update" strategy, resulting in a stepwise decline of optimization outcomes with decreasing temperature, indicating convergence toward the global optimum. Figures 13(b), 14 further reveals: during the high-temperature phase, elevated acceptance probabilities induce significant fluctuations in objective function values, effectively enhancing the algorithm’s ability to escape local optima; while during the cooling process, systematic reduction of acceptance probabilities leads to progressively stabilized convergence of objective function values.

Comparison of dynamic performance before and after optimization;(a) Vehicle Sperling index; (b) wear index for all wheels;(c) Stress index for elastic components; (d) Sound pressure level index for driving wheels; (e) Sound pressure level index for guide wheels; (f) Sound pressure level index for stable wheels.

According to the multi-start simulated annealing algorithm, the best function value is 0.5330, indicating that the optimized vehicle’s dynamic performance metric has improved by 46.7% compared to the original state.

Specific comparison of dynamic performance optimization as shown in Fig. 15.

According to Fig. 15, the optimization results for various parameters show that the vehicle’s Sperling index decreased by 25.38%, while the stress on elastic components decreased by 87.07%, and wheel wear decreased by 74.33%. It is also observed that for high-frequency vibrations such as wheel-rail noise, the effectiveness of this optimization method is not significant. For the study of noise and other high-frequency vibrations, multi-rigid-body dynamics is no longer applicable, and it is necessary to develop more complex finite element models for analysis.

The comparative results of key vehicle parameters before and after optimization are presented in Table 2.

Conclusion

This paper focuses on suspended monorail vehicles to address the challenge of directly applying conventional railway vehicle dynamics analysis methods to strongly coupled nonlinear dynamic systems. Research indicates that the dynamic performance of manufactured vehicles can be further enhanced through the methodology proposed in this study.

Existing railway vehicle dynamics analysis approaches, primarily based on decoupled linearization theory, may lead to vibration characteristic distortions when applied to strongly coupled nonlinear systems. Current suspended monorail modeling frameworks often oversimplify guide wheel interactions by treating them as horizontal force units while neglecting slip forces, a reduction that aligns the model’s structural form with conventional rail systems but fails to capture the multidirectional vibration interdependencies critical to suspended monorail. To resolve this critical issue, while fully preserving the strongly coupled nonlinear characteristics of the system, we developed a high-fidelity digital twin model of the suspended monorail vehicle using experimental Sperling index data. This model enables accurate computation of strongly coupled nonlinear vehicle dynamics characteristics, effectively overcoming the technical bottleneck in the dynamics analysis of such systems.

This paper proposes a multi-parameter multi-objective cooperative optimization method for strongly coupled nonlinear systems. Based on big data search technology, a multi-objective optimization mathematical model for vehicles is established. The model first dynamically adjusts vehicle dynamic parameters through batch processing, then conducts high-fidelity dynamic simulations, and finally achieves systematic evaluation and normalized weighted processing of various dynamic performance metrics.

Through numerical simulations and theoretical analysis of 32-dimensional test functions, this study demonstrates the significant advantages of simulated annealing in high-dimensional optimization: its convergence speed is 37 times faster than genetic algorithms, and its elimination of encoding/decoding operations enhances engineering practicality. Moreover, its probability-based jump mechanism ensures more reliable optimization results by effectively avoiding local optima—a common drawback of genetic algorithms.

The proposed optimization method significantly improves computational speed and result reliability. First, Sobol global sensitivity analysis identifies key vehicle dynamics parameters with significant influence on critical performance metrics as optimization variables. Then, an enhanced multi-start parallel simulated annealing algorithm is employed: parallel computing greatly enhances efficiency, while multi-initial-point synchronous search expands the solution space exploration, effectively reducing the risk of local optima and ensuring globally reliable results.

Optimization results demonstrate significant reductions in the Sperling index, tire wear index, and stress index of elastic components for the test vehicle. This study innovatively proposes an optimization methodology for strongly coupled nonlinear systems, overcoming the limitations of conventional techniques in handling system coupling and nonlinearity. The findings not only provide an effective solution for rail vehicle dynamics optimization, but the proposed theoretical and methodological framework can also be extended to other complex electromechanical systems, demonstrating substantial engineering applicability and academic significance.

Data availability

All experimental data generated in this study have been uploaded as Supplementary Material (filename: data.zip).

References

Zuo, L. Public safety risk prediction of urban rail transit based on mathematical model and algorithm simulation. Soft Comput. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00500-023-08919-x (2023).

Chen, X. et al. A vehicle–track beam matching index in EMS maglev transportation system. Arch. Appl. Mech. 90, 773–787. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00419-019-01638-6 (2020).

Yang, Y., He, Q., Cai, C., Li, R. & Zhu, S. Multi-objective optimization of the dynamic performance of a suspended monorail vehicle based on an effective surrogate model. Eng. Optim. 56(12), 1950–1971. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305215X.2023.2290517 (2024).

Hou, M., Yang, G., Chen, B., Liu, F. & Wang, N. Investigating the effect of rail profile deviation on hunting instability of high-speed railway vehicle under multi-parameter coupling. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng, Part F: J Rail Rapid Transit. 238(2), 152–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/09544097231181301 (2024).

Zhao, H. et al. Dynamic characteristics and sensitivity analysis of a nonlinear vehicle suspension system with stochastic uncertainties. Nonlinear Dyn. 112, 21605–21626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-024-10159-z (2024).

Zhang, X. & Hoagg, J. B. Frequency-domain subsystem identification with application to modeling human control behavior. Syst Control Lett. 87, 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sysconle.2015.10.009 (2016).

Machado, J. D. P. & Blanter, Y. M. Quantum nonlinear dynamics of optomechanical systems in the strong-coupling regime. Phys. Rev. A. 94(6), 063835. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.94.063835 (2016).

Sarker, P. & Chakravarty, U. K. A generalization of the method of lines for the numerical solution of coupled, forced vibration of beams. Math. Comput. Simul. 170, 115–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matcom.2019.10.011 (2020).

Nowicki, M. & Respondek, W. Mechanical linearization of mechanical control systems without controllability assumption. Automatica 155, 111098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.automatica.2023.111098 (2023).

Nowicki, M. & Respondek, W. Input-output linearization and decoupling of mechanical control systems. Int. J. Robust. Nonlinear Control. 34(13), 8644–8660. https://doi.org/10.1002/rnc.7406 (2024).

Lei, S. et al. Frequency-domain method for non-stationary stochastic vibrations of train-bridge coupled system with time-varying characteristics. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 183, 109637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2022.109637 (2023).

Sun, Y. et al. Dynamic analysis and vibration control for a maglev vehicle-guideway coupling system with experimental verification. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 188, 109954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2022.109954 (2023).

Yang, Y. et al. A novel 3D train–bridge interaction model for monorail system considering nonlinear wheel-track slipping behavior. Nonlinear Dyn. 112, 3265–3301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-023-09240-w (2024).

Chen, Z. et al. Mechanical characteristics of resilient wheels that consider structural nonlinearity and varying wheel/rail contact point. Int. J. Mech. Mater Des. 20, 15–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10999-023-09655-8 (2024).

Liu, B., Vollebregt, E. & Bruni, S. Review of conformal wheel/rail contact modelling approaches: towards the application in rail vehicle dynamics simulation. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 62(6), 1355–1379. https://doi.org/10.1080/00423114.2023.2228438 (2023).

Meymand, S. Z., Keylin, A. & Ahmadian, M. A survey of wheel–rail contact models for rail vehicles. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 54(3), 386–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/00423114.2015.1137956 (2016).

Bao, Y., Xiang, H., Li, Y. & Hou, G. Dynamic effects of turbulent crosswinds on a suspended monorail vehicle–curved bridge coupled system. J. Vibration Control. 28(9–10), 1135–1147. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077546320988197 (2022).

Bao, Y., Xiang, H., Li, Y., Yu, C. & Wang, Y. Study of wind–vehicle–bridge system of suspended monorail during the meeting of two trains. Adv. Struct. Eng. 22(8), 1988–1997. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369433219830255 (2019).

Shabana, A. A. et al. Development of elastic force model for wheel/rail contact problems. J. Sound Vib. 269(1–2), 295–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-460X(03)00074-9 (2004).

Wu, P., Zhang, F., Wang, J., Wei, L. & Huo, W. Review of wheel-rail forces measuring technology for railway vehicles. Adv. Mech. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1177/16878132231158991 (2023).

Cabrera, J. A. et al. A procedure for determining tire-road friction characteristics using a modification of the magic formula based on experimental results. Sensors. 18(3), 896. https://doi.org/10.3390/s18030896 (2018).

Yan, X. Non-linear three-dimensional finite element modeling of radial tires. Math. Comput. Simul. 58(1), 51–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-4754(01)00320-2 (2001).

Nakashima, H. & Wong, J. Y. A three-dimensional tire model by the finite element method. J. Terramechanics. 30(1), 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-4898(93)90028-V (1993).

Zhang, M. et al. A detailed tire tread friction model considering dynamic friction states. Tribol Int. 193, 109342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.triboint.2024.109342 (2024).

Johnsson, A., Berbyuk, V. & Enelund, M. Pareto optimisation of railway bogie suspension damping to enhance safety and comfort. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 50(9), 1379–1407. https://doi.org/10.1080/00423114.2012.659846 (2012).

Sun, J. et al. Modal parameters-based hunting stability analysis of high-speed railway vehicles considering full range of equivalent conicity. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng, Part K: J Multi-body Dyn. 236(3), 422–439. https://doi.org/10.1177/14644193221103211 (2022).

Yao, Y., Li, G., Wu, G., Zhang, Z. & Tang, J. Suspension parameters optimum of high-speed train bogie for hunting stability robustness. Int. J. Rail. Transp. 8(3), 195–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/23248378.2019.1625824 (2019).

Yao, Y., Chen, X., Li, H. & Li, G. Suspension parameters design for robust and adaptive lateral stability of high-speed train. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 61(4), 943–967. https://doi.org/10.1080/00423114.2022.2062012 (2022).

Chen, X., Yao, Y., Shen, L. & Zhang, X. Multi-objective optimization of high-speed train suspension parameters for improving hunting stability. Int. J. Rail Transp. 10(2), 159–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/23248378.2021.1904444 (2021).

Li, D. et al. Global optimization of medium low-speed maglev train-bridge dynamic system based on multi-objective evolutionary algorithm. Int. J. Struct. Stability Dyn. 24(05), 2450049. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219455424500494 (2024).

Chen, X., Shen, L., Hu, X., Li, G. & Yao, Y. Suspension parameter optimal design to enhance stability and wheel wear in high-speed trains. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 62(5), 1230–1252. https://doi.org/10.1080/00423114.2023.2224905 (2023).

Wu, Q., Sun, Y., Spiryagin, M. & Cole, C. Methodology to optimize wedge suspensions of three-piece bogies of railway vehicles. J. Vibration Control. 24(3), 565–581. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077546316645698 (2018).

Wang, Q., Zeng, J., Shi, H. & Jiang, X. Parameter optimization of multi-suspended equipment to suppress carbody vibration of high-speed railway vehicles: a comparative study. Int. J. Rail. Transp. 12(6), 1000–1019. https://doi.org/10.1080/23248378.2023.2291202 (2023).

He, Q. et al. An improved dynamic model of suspended monorail train-bridge system considering a tyre model with patch contact. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 144, 106865. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2020.106865 (2020).

Cai, C. et al. Dynamic interaction of suspension-type monorail vehicle and bridge: numericsal simulation and experiment. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 118, 388–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2018.08.062 (2019).

Bao, Y., Li, Y. & Ding, J. A case study of dynamic response analysis and safety assessment for a suspended monorail system. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 13(11), 1121. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13111121 (2016).

Yan, J. M. Vehicle Engineering 2nd edn. (China Railway Publishing House, 2003).

Tang, Y., Sadjadi, P., Dehaghani, M. R. & Wang, G. G. A systematic online update method for reduced-order-model-based digital twin. J. Intell. Manuf. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10845-024-02524-x (2024).

Jiang, Y. et al. Prediction of wheel wear of different types of articulated monorail based on co-simulation of MATLAB and UM software. Adv. Mech. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1177/1687814019856841 (2019).

Z. Li, F. Zhan, Virtual.Lab Acoustics: Advanced Applications of Acoustic Simulation and Calculation, first ed., National Defense Industry Press, Beijing, (2014).

Yongzhi, Jiang Pingbo, Wu Jing, Zeng Long, Jiang (2024) Real-time detection of wheel-rail conditions in a monorail vehicle-track nonlinear system based on vehicle vibration signals. Journal of Vibration and Control, 30(17-18), 4052-4068, https://doi.org/10.1177/10775463231206215 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgement of Funding Support.

Funding

State Key Laboratory of Rail Transit vehicle system Open Fund, RVL2410, National Natural Science Foundation of China, 52305093, Youth Foundation of Chongqing Education Board,KJQN202200727, Youth Foundation of Chongqing Education Board,KJQN202300740, Chongqing Natural Science Foundation General Project, CSTB2023NSCQ-MSX0054, Research Foundation for Talented Scholars in Chongqing Jiaotong University, F1220007, Chongqing Key Laboratory of Urban Rail Transit System Integration and Control Open Fund, CKLURTSIC-KFKT-212003, Chongqing Natural Science Foundation Innovation and Development Joint Fund Project, CSTB2024NSCQ-LZX0105, Chongqing Graduate Joint Cultivation Base Project, JDLHPYJD2024006.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jiang provides funds support, proposes methodology and innovative research framework, writes initial draft and reviews final draft Zhang designs key experiment and writes MATLAB programs, writes writes initial draft and final draft, constructs a dynamic model Liu supports experiment and Matlab programs, reviews final draft. Chen reviews final draft. Wang reviews final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Declaration of generative AI for spell-check in word processing

During the preparation of this work the author(s) used ERNIE Bot for spell-check in word processing. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, Y., Zhang, S., Liu, W. et al. Multi-parameter and multi-objective collaborative optimization of a suspended monorail vehicle addressing its strongly coupled nonlinear characteristics. Sci Rep 15, 39322 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23108-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23108-6