Abstract

Despite the overall positive outcomes in hospitalization and mortality rates from the COVID-19 vaccines, COVID-19 infections remained prevalent around the world highlighting the need for alternative control strategies. Passive immunization with chicken IgY has long served as a feasible countermeasure, which gained further popularity in the research community during the recent pandemic. Here we demonstrate for the first time the scalability of anti-COVID-19 IgY production for effective distribution and potential use in large populations. Over 70,000 chickens were immunized against the SARS-CoV-2 S1 antigen to produce eggs containing anti-S1 IgY. The resulting egg yolk powder was formulated into commercially acceptable tablets for human consumption. QC and stability testing showed that the purified IgY and tablets maintained activity and stability for over a year. The resulting large batch of IgY tablets demonstrated equal immunoreactivity and virus neutralization potential against all leading COVID-19 variants. Our results demonstrate the feasibility of manufacturing egg yolk powder into edible tablets, and that can now be employed to block viral infectivity and transmission against all major COVID-19 variants affordably and effectively in both developed and developing countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The influx and severity of COVID-19 infections has gone beyond our expectations. The unprecedented number of infections and extremely high rates of transmission have caused significant strain on hospitals and other healthcare facilities. Despite the use of available PPE (face masks or shields, gloves, disposable gowns), vigilant hand washing and disinfection, as well as vaccines, we have witnessed a large increase in the numbers of COVID-19 cases, particularly with the Omicron variants. Since the Omicron peak, there has been a sharp reduction in case numbers reaching a plateau, however, this does not reflect the true situation since many, or most COVID-19 cases today never get reported. This not only poses significant risk to the individual infected patient, but also the people around them, both within the healthcare facility (other workers and patients) and outside (general public and family members). Furthermore, new viral strains may suddenly appear that are highly virulent and transmissible. Thus, despite the success of the COVID-19 vaccines in helping to lower morbidity and mortality, there is a need for strategies that can strongly reduce disease transmission and spread.

Over the past few years, we and others have published several articles demonstrating the use of chicken IgY in controlling infection and transmission by COVID-191,2,3,4 as well as other viruses such as SARS5,6 and Influenza7. This was demonstrated by immunizing laying hens with very small quantities of highly purified SARS-CoV-2 S1 glycoprotein8, leading to a strong antibody response in the sera of the chickens, which then appears in very large quantity of IgY in their egg yolk. Eggs were collected, the yolk separated and the IgY purified. Using this purified antibody, we demonstrated a very high titer against S1 antigen by both ELISA and Western blotting. It was also shown that it can neutralize the virus in vitro, as well as provide in vivo protection against infection in a hamster model9. Finally, a Phase 1 clinical trial was carried out demonstrating the safety of IgY as a nasal formulation in humans10.

Based on the results obtained in animal model studies, it was concluded that chicken IgY raised against the SARS-CoV-2 S1 protein can act as a barrier against infection and last for at least 6–8 h. We hypothesized that the IgY can be formulated as either a nasal drop or an edible tablet, to be taken every 6–8 h when encountering potentially infected people. When administered as a tablet, the IgY antibodies will coat the mouth, oropharynx, larynx, and in particular the trachea13. As shown in previous studies, when the virus is inhaled, it will be sequestered and neutralized by the IgY, preventing passage of the virus to the lungs where it normally establishes an infection.

In the current research presented here, we demonstrate the ability and feasibility to scale up and produce chicken IgY (in the form of dry egg yolk) in an edible tablet formulation produced on a large scale under food quality production standards. We also show how this can be accomplished and developed new methods for the scale up of immunization, quality control, epitope specificity and stability testing, demonstration of in vitro cross protection, and tablet formulation.

Worldwide, there are approximately 7 billion laying hens11 which could be used in an emergency anywhere in the world to produce a vast quantity of protective IgY in as little as 30 days from first inoculation of the hens in a highly cost-effective manner. Our working hypothesis is that by producing large numbers of tablets (in the hundreds of millions or billions) commercially at a very cheap cost, they can be used to help control or slow down the transmission and spread of COVID-19 throughout a hospital, school or in the general public. Further, these tablets contain egg yolk powder and as such are amenable for use in children and the elderly. Although in its current egg-yolk powder form, the tablets are not safe for individuals with egg sensitivities, the IgY can be further purified from the egg yolk powder to allow for use by individuals with sensitivity to eggs12. This work is an important step in demonstrating the scalability and use of chicken IgY to control COVID-19 transmission, that can be marketed as a food product for human consumption. Therefore, the objective for this study was to show that these tablets can be manufactured on large scale in an economically feasible manner for the prevention and control of COVID-19 with the intent for the betterment of global health.

Materials and methods

Antigens

Antigens were sourced from ACROBiosystems Inc. The variant ID, lineage and origin are listed in Table 1 below.

Vaccination protocol for small- and large-scale production

Seven young White Leghorn hens (38 weeks of age) were vaccinated with SARS-CoV-2 S1 antigen. The S1 glycosylated antigen used was from the Wuhan variant produced by ACROBiosystems. The antigen was produced in HEK cells labeled His and mixed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) with Emulsigen-D (Phibro Animal Health Products, Teaneck, NJ, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions at 50% (v/v). Each Hen received 5 µg of antigen diluted in Emulsigen-D twice, two weeks apart, to a total of 10 µg. Hens were vaccinated using a repeater injector and 1 mL was injected into the breast muscle of each bird. The first immunization was administered on one side of the breast and the second on the other side. Eggs were collected at different time points during the immunization schedule as shown in Table 2.

The same vaccination procedure was performed on the large-scale production of IgY in which 73,000 White Leghorn hens (44 weeks of age) were immunized. The sample size was chosen based on previous studies on other antigens where it was found a high level of consistency in the immune responsiveness of vaccinated laying hens against a variety of antigens13.

Control IgY used in this study was prepared from eggs laid prior to immunization. The small-scale production included IgY pooled from 24 egg yolks, while the large-scale production was prepared from 96 egg yolks. All eggs used were randomly selected.

All laying hens were raised following the National Chicken Council’s recommendations. Farm personnel followed strict environmental policies which included proper ventilation, indoor protection from predators and weather, and proper lighting which allowed for the ability to monitor disease. Flock health was inspected daily by trained personnel. On-staff veterinarians and poultry nutritionists designed diets to meet the unique physical needs of egg-laying hens which are customized to the age-specific needs of the flock. Feed and water quality were optimized for hen health. All hens were raised without the use of hormones.

Only hens or eggs lost due to regular loss were excluded from the study. Hens that were not laying were removed during commercial production. No adverse events were observed throughout the duration of the study.

This study is reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

IgY extraction and purification from hen egg yolk

Twelve eggs from each vaccination time point (Table 2) were selected at random. The egg yolks were manually separated from the whites, the vitelline membranes pierced, and the egg yolk drained and pooled. The pooled yolk was gently mixed on a stir plate for 10 min at room temperature. 50 mL of homogenized yolks was combined with 150 mL of 4.67% (w/v) polyethylene glycol 8000 (PEG 8000) in PBS. The solution was centrifuged at 10,000 x g for 15 min at 4˚C. The resulting supernatant fluid was recovered through cheesecloth and the volume measured. A volume equivalent to one third the volume of the supernatant (~ 50 mL) of 37.5% (w/v) PEG 8000 in PBS was added to the supernatant and mixed gently on a stir plate for 10 min at room temperature. The solution was centrifuged at 10,000 x g for 15 min at 4˚C, supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended with 50 mL PBS. The solution was centrifuged again at 10,000 x g for 15 min at 4˚C to remove residual PEG 8000. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in 50 mL PBS. The purified IgY was filter sterilized through a 0.2 μm PES membrane, aliquoted, and stored at either 4˚C or −20˚C depending on future use. The purified IgY preparations were analyzed using the A260/280 ratio, and concentrations approximated using the absorbance at 280 nm.

ELISA

Corning Costar 96-well high-binding polystyrene were coated by applying 250 µL of ACROBiosystems recombinant protein (ACROBiosystems, Newark, DE, USA) at 1 µg ml−1 in carbonate bi-carbonate (CBC) buffer (pH 9.6) to test wells and CBC buffer only to control wells. Plates were incubated at 37˚C for 1 h. Plates were then aspirated, and each well blocked with 390 µL of 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for another hour at 37˚C. Wells were washed with Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20 (WB) and air dried in a 25˚C incubator for 1 h. Plates were used immediately upon drying, or vacuum sealed and stored at 4˚C. Purified IgY samples to be tested were prepared by initially diluting the antibody 1:600 in BSA and serially diluting 1:2 in BSA. 125 µL of each dilution were transferred to ACROBiosystems recombinant protein-coated microwell plates. Plates were incubated at 25˚C for 1 h. The plates were washed three times with 400 µL WB per well. Plates were then conjugated with KPL goat anti-chicken IgY IgG HRP (Horseradish peroxidase; Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a concentration of 100 ng ml−1 for 1 h at 25˚C. Plates were then washed four times with 400 µL WB per well. The assay was developed in the dark using 100 µL per well of Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) two component peroxidase substrate system (SeraCare Life Sciences, Inc., Milford, MA, USA) for 10 min. Developing was stopped using 100 µL of 1 M sulfuric acid. Absorbance of wells was measured at 450 nm and corrected using control well values.

LDS-PAGE and western blotting

Western blotting was performed using the iBlot 2 and iBind systems (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Sample preparation for gel electrophoresis was performed following the NuPAGE Bis-Tris Mini Gel protocol (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Every sample was comprised of NuPAGE LDS sample suffer and NuPAGE reducing agent at 1X concentration. The targeted protein amount for each sample was 2 µg/well. Deionized water was added to a final volume of 45 µL. Samples were heated at 100˚C for 3 min. Both chambers of a Life Technologies Mini Gel Tank (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were filled with 400 mL of 1X NuPAGE MES running buffer. NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris mini gels were rinsed with 1X running buffer and placed in each chamber of the gel tank. A volume of 20 µL from each sample were loaded into both gels. Electrophoresis was performed at 200 V constant for 30 min. Upon completion, gels were washed in deionized water three times for 10 min each on a platform shaker. One gel was then stained with Imperial Protein Stain (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for final LDS-PAGE analysis, while the duplicate gel was placed on an iBlot 2 PVDF transfer stack.

The transfer was performed on the iBlot 2 system at 20 V for 1 min, 23 V for 4 min, and then 25 V for 2 min per iBlot 2 protocol recommendation. The membrane was then washed in 1X iBind solution and placed in the iBind Western system. anti-SARS-CoV-2 S1 His-tag IgY was used as the primary antibody at a concentration of 15 µg ml−1. KPL goat anti-chicken IgY IgG HRP was applied as the secondary antibody at a concentration of 15 µg ml−1. After overnight incubation, the membranes were washed for 1 min in deionized water. Detection was performed using Novex HRP chromogenic substrate 3,3’,5,5’-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) for 5 min on a platform shaker. Membranes were allowed to dry in a dark drawer prior to image capture.

Dot blotting

2 µL of recombinant protein (S1, RBD, NTD) at a concentration of 0.5 mg ml−1 were dotted onto strips of nitrocellulose (Pall Corp., Port Washington, NY, USA). After drying, non-specific sites were blocked in 5% (v/v) BSA. Strips were incubated with anti-S1 IgY or anti-Normal IgY at 25 µg ml−1. Strips were washed in 0.05% PBS-Tween 20 (v/v). The strips were incubated in goat anti-chicken IgY IgG HRP-conjugated (Thermo Fischer Scientific) at 1 µg ml−1. After washing, the blots were developed with Novex HRP chromogenic TMB (Thermo Fischer Scientific).

RBD binding assay

Two commercial ELISAs manufactured by ACROBiosystems catalog EP-107(WT) and EP-115(B.1.1.529) were used to look at the potential for the IgY to inhibit the RBD binding to the ACE2 receptor. The protocol was provided along with all the reagents by ACROBiosystems. The plate provided was precoated with Human ACE2 protein. Samples and controls were added to the wells along with the HRP labeled SARS-CoV 2 Spike RBD. The plates were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C, developed with TMB, and read at an absorbance of 450 nm.

In vitro virus neutralization

The chicken-derived IgY samples labelled Day 0, Day 14, Day 21, and Day 28 were assessed for their ability to neutralize SARS-CoV-2 virus using a PRNA assay. Briefly, the antibodies were diluted 1:10, 1:20,1:40, and 1:80 in culture medium and incubated with 200 plaque forming units (PFU) of the SARS-CoV-2 variant being tested. SARS-CoV-2 was diluted in supplemented (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium) DMEM to the appropriate concentration to achieve 200 PFU. The virus was then added to antibody samples and allowed to incubate for 1 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. After incubation, a viral plaque assay was conducted to quantify viral titers using 12-well plates previously seeded with Vero cells (ATCC CCL-81) at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well. Media was aspirated from plates and virus-antibody samples were transferred to wells, one sample per well. Plates were inoculated for 1 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. After infection, a 1:1 overlay consisting of 0.6% agarose and 2X Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium without phenol red (Quality Biological, 115-073- 101), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, 10,437,028), non-essential amino acids (Gibco, 11140-050), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Corning, 25-000-Cl), 2 mM L-glutamine, 1% penicillin-streptomycin (P/S) was added to each well. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. Cells were fixed with 10% formaldehyde for 1 h at room temperature. Formaldehyde was aspirated and the agarose overlay was removed. Cells were stained with crystal violet (1% w/v in a 20% ethanol solution). The viral titer of SARS-CoV-2 was determined by counting the number of plaques.

Tablet formulation

Seattle Gourmet Foods (Kent, WA, USA), a commercial candy manufacturer, was contracted for small pilot runs and a scale up to a production run. The edible tablets produced contained Dipack (sugar and maltodextrin; 49.5%), dextrose (26.5%), pasteurized egg yolk powder (15%), natural flavor (3.5%), and citric acid, malic acid, stearic acid, and magnesium stearate (≤ 2% each). The powders were mixed and made into tablets using a tablet press.

Where tablets were tested via ELISA in this study, samples were prepared by dissolving three tablets (each containing 120 mg of egg yolk powder and approximately 5.4 mg of IgY) in 19 mL of Egg Extract Buffer (EEB).

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were analyzed using the GraphPad Prism 8.0.1 software (GraphPad Software, Boston, Massachusetts USA). Statistical significance was performed using the T-test (2-tailed), where p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically different.

Results

Immunoreactivity of IgY against SARS-CoV-2 S1 protein tested on a small scale

The SARS-CoV-2 S1 protein or RBD peptide reactivity of both purified IgY and egg yolk was examined in eggs collected from 7 hens at two weeks post second immunization (D21) with Fc tagged S1 glycoprotein using ELISA. The ELISA assay (Fig. 1) showed strong positive binding of both egg yolk-IgY and purified IgY to the S1 protein demonstrating that the S1 protein is highly immunogenic in hens. These antibodies also reacted very strongly with the RBD peptide by ELISA. Finally, there was only a small decrease in binding affinity of the purified anti-S1 IgY compared to that of the IgY in whole egg yolk.

Immunoreactivity of IgY raised against Wuhan variant S1 protein via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). (A) Immunoreactivity of IgY in either purified or non-purified (egg yolk) form was tested against the Receptor-Binding Domain (RBD) epitope (left) or whole construct of the SARS-CoV-2 S1 protein (right). (B) Immunoreactivity of purified IgY from individual eggs from hens not immunized (left; negative control) or immunized (right) against Wuhan variant SARS-CoV-2 S1 protein. Immunoreactivity of IgY was tested at two dilution (antigen: IgY) ratios: 1:1200 and 1:2400. Statistical difference determined between the negative control and test samples (p < 0.0001). (C and D) Reactivity of IgY at different time point where IgY was purified from eggs collected at weekly intervals up to 4 weeks (C) or up to 3 months (D). Immunoreactivity of IgY was tested at different antigen: IgY dilution ratios.

Immunoreactivity of purified IgY from individual eggs

Individual eggs may demonstrate different IgY content leading to variability during production and manufacturing. Therefore, to determine the extent of variability of the IgY titer in individual hens, 12 eggs from different immunized hens were selected at random and their IgY isolated and tested by ELISA. This was compared to 8 eggs collected at random from non-immunized hens. As shown in Fig. 1B, we found that the IgY titer was high in all the eggs from immunized hens. In contrast, the negative controls (IgY from non-immunized hens), only gave consistent background levels of reactivity.

Immunoreactivity of purified IgY over time

To determine the rate at which anti-S1 antibody activity appears in the egg yolk, an ELISA was performed on purified egg yolk IgY taken at each stage of egg collection. As shown in Fig. 1C, no increase in IgY titer is seen at the first egg collection after the first immunization (D0). However, a significant increase in IgY titer is seen at the third egg collection (D21). The high IgY titer is maintained for the remaining samples collection over a period of 3 weeks and further work showed that the titer remains high for up to 3 months (Fig. 1D).

Western blot analysis of IgY

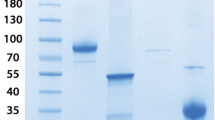

LDS gel and Western blot analysis was conducted to confirm both the purity of the IgY and its reactivity against the S1 antigen (reduced and non-reduced; ACROBiosystems). HRP conjugated goat anti-chicken IgY reacted strongly with a 180 kDa protein band of IgY under non-reducing conditions (Fig. 2, lane 1; Original full-length images can be seen in Figure S1). The anti-S1 IgY reacted strongly with both reduced and non-reduced forms of the SARS-CoV-2 S1 antigen, suggesting the anti-S1 IgY antigen recognition site is not affected in reduced conditions.

Protein analysis of antigen specificity. Left: SDS-PAGE analysis of Wuhan variant α- SARS-CoV-2 S1 IgY and ACROBiosystems SARS-CoV-2 S1 Recombinants – reduced and non-reduced. Right: Western Blot Analysis of Wuhan variant α- SARS-CoV-2 S1 IgY and ACROBiosystems SARS-CoV-2 S1 Recombinants – reduced and non-reduced. Lanes are identified as follows: (1) α- SARS-CoV-2 S1 IgY (Lot#061820BR) positive control; (2) 1X LDS sample buffer negative control (Lot#2165459) (3) ACROBiosystems SARS-CoV-2 S1 recombinant (Lot#3594b-203ZF1-RC), reduced; (4) ACROBiosystems SARS-CoV-2 S1 recombinant (Lot#3594b-203ZF1-RC), non-reduced. Each lane is loaded with 2 ug targeted amount. The loaded antigen is detected by chicken anti-S1 IgY. The secondary detection antibody used is KPL goat anti-chicken IgY IgG HRP. Original full-length images can be seen in Figure S1.

Virus neutralization study

IgY from hens immunized with the S1 antigen were tested using an in vitro plaque assay for virus neutralization. This assay was completed under blinded conditions. The Alpha variant of SARS-CoV-2 was used to infect Vero cells in culture. There was a significant reduction in plaque forming units reaching a maximum at 3 weeks post second immunization (D21; Fig. 3); a similar response was seen on D28. Interestingly, there was a significant reduction seen on D14 with a titer of 1:10.

Upscaling of IgY production

We next carried out large-scale production of the SARS-CoV-2 S1-specific IgY by vaccinating 73,000 hens with 5 µg of purified his tagged S1 glycoprotein (Wuhan variant produced by ACROBiosystems). An ELISA was performed to examine the IgY titer in both the purified IgY fractions and in the egg yolks sampled post immunization (Fig. 4). Consistent with the small-scale experiments, a significant increase in the SARS-CoV-2 S1 IgY in both purified IgY samples and egg samples was seen post immunization with the SARS-CoV-2 S1 protein antigen.

Following confirmation of the high titer of IgY in the egg yolks of the immunized hens, eggs were collected and sent to a commercial egg processing facility where the egg yolks were separated, pasteurized, and spray dried. After 12 weeks of collection and pooling into batches we produced a total of 63,000 kg of high titer, spray dried egg yolk powder.

To ensure that the spray dried egg yolk was free of contaminating pathogens, a quality control and batch safety test was carried out by the tablet manufacturer (Seattle Gourmet Foods, Washington, USA). The dried egg yolk was tested for the presence of common contaminant pathogens. No significant levels of contaminants were detected in the spray dried egg yolk which were therefore approved for food safety (Table 3).

Production of tablets does not affect IgY titer

Tablets were produced on a large scale at the approved facility of Seattle Gourmet Foods, Washington, USA. The final prototype product contained 120 mg of egg yolk powder in a tablet weighing 800 mg. To ensure production and manufacturing of dried egg yolk into the final tablet form does not affect the quality of the IgY, antibody titer was established using ELISA at the different stages of production. These stages included the collection of large quantities of yolk from eggs of immunized hens, pasteurization of the egg yolk, production of egg yolk powder by spray drying and formulation into a tablet. It was found that the whole process from egg to the production of the tablets was found to not significantly impact the titer of the IgY in the product (Fig. 5a).

Immunoreactivity of IgY throughout the (A) production and (B) storage process. Tablets were stored in a dark room at room temperature from the date of manufacture to the date of testing. Sample concentrations were normalized before plotting. Immunoreactivity of IgY was tested against Wuhan variant S1 protein at different antigen: IgY dilution ratios.

Given that the intended tablets would be used over a period of time, we wanted to ensure that the IgY titer maintained stability throughout its expected 1-year shelf life. Tablets were stored at room temperature long-term (nearly 2 years (652 days)) were tested by ELISA (Fig. 5b). It was found that IgY titer levels in the tablets remained stable throughout the entire storage period as compared to the positive egg-yolk powder control.

Chicken IgY antibody titer against SARS-CoV-2 variants

During the time of the scale up production of the chicken IgY, several variants of SARS-CoV-2 arose in various countries around the world. Available vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 have shown variable efficacies against these new variants. It therefore raised the question of the reactivity of Chicken IgY raised against the alpha variant S1 glycoprotein, against these new SARS-CoV-2 variants.

The SARS-CoV-2 S1 spike protein is composed of two key epitopes: a receptor binding domain (RBD) and an N-terminal domain (NTD). The IgY has been raised against the whole S1 protein, and we wished to test its binding affinity to the S1 protein as well as these two specific regions. An ELISA was performed to determine the cross reactivity of anti-Wuhan variant IgY against the S1 protein, RBD and NTD from all the leading SARS-CoV-2 variants. As can be seen in Fig. 6A, it was found that antibodies against the original Wuhan S1 protein reacted strongly with the S1 protein from all the variants tested with OD values between 1.5 and 2.5 absorbance units at a dilution of 1:600. In contrast, control, non-immune IgY had no significant reactivity with any of the proteins/peptides tested.

The results also showed that there was very strong cross reactivity of the anti-S1 IgY against all RBDs and NTDs tested (Fig. 6B and C, respectively) and as expected the OD values were somewhat lower (between 1 and 1.5 absorbance units) than that found against the whole S1 protein. Both purified IgY and IgY extracted from the tablets after being dissolved in Egg Extract Buffer (EEB) fully cross reacted against the S1s, RBDs and NTDs. Finally, it was found that the reactivity with the RBD peptide was significantly stronger than that seen with the NTD peptide particularly when using tablet IgY.

Cross reactivity of chicken IgY against SARS-CoV-2 variants by western blotting and dot blotting

Western blot and dot blot analysis were used to examine the specificity of IgY to the whole S1 as well as to the RBD and NTD epitopes of the antigen, respectively (Fig. 7). We found that there was equal reactivity against the S1 glycoproteins in all the variants tested by Western blotting as was seen by ELISA (Fig. 7a). To reduce any possible effect of incomplete transfer during blotting, we also carried out a dot blot analysis comparing S1, RBD and NTD glycopeptides from all the major variants. Once again as seen by ELISA there was little or no difference in intensity between the variants (Fig. 7b). These results taken together show that the IgY recognized the major epitopes in S1 equally in all variants.

(A) Coomassie stained LDS-PAGE (left) and Western Blot (right) of recombinant whole S1 variants. Each lane is loaded with 2 ug targeted amount. All samples were reduced. Western blot was performed using anti-S1 IgY as the primary antibody. (B) Immunoblot of RBD and NTD variants against anti-S1 IgY (left) and control IgY (right). Original full-length images can be seen in Figure S1.

In vitro RBD/ACE2 binding inhibition assay

An RBD/ACE2 binding inhibition assay was performed to test the ability of the anti-S1 IgY to block the interaction between these two key receptor proteins. As can be seen in Fig. 8, there was a strong reduction in RBD binding to ACE2 in both the original Wuhan Hu-1 variant and the Omicron variant. This further supports the concept of using S1 to immunize hens giving rise to IgY that can inhibit virus binding to its host receptor.

In vitro virus neutralization test using IgY

An IgY sample purified from the large-scale egg yolk powder production batch provided good in vitro neutralization against both the Omicron variant (NR-56461 from BEI resources, Manassas, Virginia), and the Italian Alpha variant of SARS-CoV-2 (NR-52284), reaching a titer of 1:20 at a concentration of 9.3 mg ml−1 (Fig. 9) in comparison to control IgY used at a concentration of 8.7 mg ml−1 that showed no significant neutralization of the virus.

In vitro virus neutralization on the large-scale IgY production. Plaque formation was quantified in Vero cell cultures infected with the SARS-CoV-2 variants (A) Omicron (SARS-CoV-2 Isolate hCoV-19/USA/MD-HP20874/2021 (Lineage B.1.1.529; NR-56461)) and (B) Alpha (SARS-Related Coronavirus 2 isolate Italy-INMI1 (NR-52284)), and co-cultured with different dilutions of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgY collected. Positive control used was human serum; negative control used was IgY extracted from eggs of non-immunized hens.

Discussion

In this paper it was demonstrated that commercial hens raised under farm conditions and vaccinated on a large scale (73,000 hens), mount a very strong immune response when immunized with very small quantities of SARS-CoV-2 S1 glycoprotein produced in HEK cells (5 µg per immunization given twice intramuscularly & spaced two weeks apart). Based on the ELISA results, the titer of the egg yolk antibody is very high and lasted for at least 3 months. In other studies, IgY titers against a variety of antigens was shown to last for at least 4 months14. In addition, 100% of the hens responded to vaccination with all the eggs collected showing a very large quantity of anti-S1 IgY in the egg yolks, which based on previous studies has been shown to contain 100–150 mg specific IgY per yolk7.

Studies carried out using ELISA, Western and Dot blotting, demonstrated that the IgY produced against S1 from the Wuhan variant cross-reacted very strongly with all 6 of the major SARS-CoV-2 variants that have appeared globally (Wuhan original strain, Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, and Omicron). The reason for this is associated with the ability of Chicken IgY to cross react with different variants of viruses as was found with influenza7 and other viruses of human and veterinary importance.

Our epitope mapping results using the SARS-CoV-2 S1 glycoproteins and RBD and NTD peptides in ELISA, showed the excellent cross reactivity between all the variant derived molecules/epitopes. The ELISA results showed that the reactivity against S1 was the strongest followed by the RBD and NTD peptides as expected. Research15,16 into the RBD has highlighted its important role in establishing disease via its binding to the ACE2 receptor. In addition, recent studies17,18 have revealed a potential role for the NTD during infection and have suggested a combined RBD and NTD approach of virus neutralization may be a better way forward in disease treatment. The finding that the IgY produced against S1 reacted well with all variant RBD and NTD peptides strengthens the case for its potential use throughout the pandemic, regardless of which variant arises in the population.

In a recent study carried out by Li et al.19, those researchers mapped 20 peptide epitopes with relatively strong signals in the S-protein using IgY produced against the extracellular domain of the S-protein. Interestingly, those researchers found that 17 of them are highly conserved between SARS-CoV-2 variants with no mutations seen in the amino acid sequence. In addition, they found that the IgY used in mapping the peptide epitopes had a 98% neutralization capability. These results help explain the strong cross reactivity we observed between the SARS-CoV-2 variants and further support the concept of using IgY as a means of providing passive protection against the disease.

Virus neutralization testing using the alpha variant demonstrated the ability of IgY to block virus infection based on a plaque assay in Vero cells. It also shows that IgY made against the Wuhan variant can cross protect against infection by the Alpha and even Omicron variants. These results are supported by the RBD/ACE2 binding inhibition assay showing inhibition of binding to the RBD. Together with previous results seen using IgY to protect hamsters against COVID-19 infection, they demonstrate the potential of this approach to control COVID-19 transmission.

A study carried out using mice and hamsters to test IgY raised against the RBD followed by challenge infections with SARS-CoV-2 RBD, demonstrated the safety and protective effect of this approach9. Hamsters treated with IgY intranasally before or after infection with SARS-CoV-2 showed a clear inhibition of lung pathology. In addition, the IgY was shown to remain in the upper airways for several hours. Similar results were demonstrated by Wongso, et al., who found that IgY administered intranasally in mice accumulated in the trachea20. In our approach using the tablet formulation we would expect the IgY to also remain in the upper airways/trachea for at least 6–8 h. Further work is required to directly demonstrate this persistence of the antibody in humans.

Quality control of the large batch of IgY produced from 73,000 immunized hens showed that it reacted well by ELISA, Western and in vitro neutralization against all variants used in the study. The final tablet formulation showed that the IgY was non-contaminated based on microbiology and had a good neutralization titer. The final tablet formulation also showed good stability of the egg yolk powder IgY. Previous results have shown that IgY is very stable when produced as egg yolk powder21. However, we needed to show that this is also the case when formulated into a tablet. Based on our ELISA results comparing IgY in egg yolk powder (positive control) to that in the tablet, we found that there was no decrease in titer over a period of nearly 2 years of storage. These results demonstrate the stability and storability of IgY in a tablet where we expect to receive approval for use after at least 1 year of production. These results demonstrate that IgY can be stockpiled for use against viruses that undergo mutation and variation due to their cross-protective capability. However, while our data suggests that the IgY in the tablets remains effective against different variants, we have not tested all variants since the outbreak, and there is a small possibility that the IgY may lose its efficacy as mutations occur.

Our results show that IgY can be rapidly manufactured and formulated into a tablet with a cost of production of around 1–2 cents per tablet. However, a key limitation of this approach is that the protective effect of the tablets is only predicted to last 6–8 h before another dose is required. As such, the prophylactic effectiveness of IgY tablets depends heavily on individual compliance with regular dosing to maintain protection. Beyond prophylactic use, IgY could also be explored as a therapeutic option for patients, however, it would need to be formulated for intravenous or intraperitoneal injection requiring approval by regulatory authorities.

Conclusion

In a pandemic characterized by a threat with a high reproduction rate like SARS-CoV-2, prompt implementation of solutions to curb transmission within a population may offer significant public health benefits. IgY technology presents a cost-effective and scalable solution, enabling the rapid production of effective antibodies within 30 days of antigen identification - much faster than traditional human vaccine development. This approach has demonstrated broad-spectrum applicability across various antigens (reviewed by Lee et al.13. Leveraging existing egg production infrastructure allows for efficient manufacturing and distribution, making IgY-based products particularly suitable for early response efforts. Potential applications include deployment in high-risk environments such as schools, hospitals, retirement villages and among immunocompromised populations, offering a valuable tool to reduce transmission while vaccines are developed and distributed.

Data availability

The datasets during and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACE2:

-

angiotensin converting enzyme 2

- ATCC:

-

American type culture collection

- BSA:

-

bovine serum albumin

- CBC:

-

carbonate bi-carbonate

- COVID-19:

-

coronavirus disease 2019

- DMEM:

-

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium

- ELISA:

-

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FBS:

-

fetal bovine serum

- HEK:

-

human embryonic kidney

- HRP:

-

horseradish peroxidase

- ID:

-

identification

- IgA:

-

Immunoglobulin Y

- IgG:

-

Immunoglobulin G

- LDS:

-

lithium dodecyl sulfate

- MES:

-

2-Morpholinoethanesulphonic acid

- NTD:

-

N-terminal domain

- OD:

-

optical density

- PAGE:

-

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- PBS:

-

phosphate buffered saline

- PEG:

-

polyethylene glycol

- PES:

-

polyethersulfone

- PFU:

-

plaque forming units

- PPE:

-

personal protective equipment

- PVDF:

-

polyvinylidene difluoride

- QC:

-

quality control

- RBD:

-

ribosomal binding domain

- SARS:

-

severe acute respiratory syndrome

- SDS:

-

sodium dodecyl-sulfate

- TMB:

-

tetramethylbenzidine

- WT:

-

wild-type

References

Frumkin, L. R. et al. Egg-Derived Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Immunoglobulin Y (IgY) with broad variant activity as intranasal prophylaxis against COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 13, 1–19 (2022).

Lu, Y. et al. Generation of chicken IgY against SARS-COV-2 Spike protein and epitope mapping. J. Immunol. Res. 2020, 9465398 (2020).

Wei, S. et al. Chicken egg yolk antibodies (IgYs) block the binding of multiple SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein variants to human ACE2. Int. Immunopharmacol. 90, 107172 (2021).

Wallach, M. G. & Opinion The use of chicken IgY in the control of pandemics. Front. Immunol. 13, 954310 (2022).

Lee, Y. C. et al. A dominant antigenic epitope on SARS-CoV Spike protein identified by an avian single-chain variable fragment (scFv)-expressing phage. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 117, 75–85 (2007).

Guozhu, H. et al. Study on the effect of specific egg yolk Immunoglobulins (IgY) inhibiting SARS-CoV. Wei Sheng Wu Xue Za Zhi. 24, 123–125. (2004).

Wallach, M. G. et al. Cross-protection of chicken Immunoglobulin Y antibodies against H5N1 and H1N1 viruses passively administered in mice. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 18, 1083–1090 (2011).

Aston, E. J., Wallach, M. G., Narayanan, A., Egaña-Labrin, S. & Gallardo, R. A. Hyperimmunized chickens produce neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. Viruses 14, 1510 (2022).

Agurto-Arteaga, A. et al. Preclinical assessment of IgY antibodies against Recombinant SARS-CoV-2 RBD protein for prophylaxis and Post-Infection treatment of COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 13, 881604 (2022).

Frumkin, L. R. et al. COVID-19 prophylaxis with Immunoglobulin Y (IgY) for the world population: the critical role that governments and non-governmental organizations can play. J. Glob Health. 12, 03080 (2022).

Fernyhough, M., Nicol, C. J., van de Braak, T., Toscano, M. J. & Tønnessen, M. The ethics of laying Hen genetics. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics. 33, 15–36 (2020).

Abbas, A. T., El-Kafrawy, S. A., Sohrab, S. S. & Azhar, E. I. A. IgY antibodies for the immunoprophylaxis and therapy of respiratory infections. Hum. Vaccin Immunother. 15, 264–275 (2019).

Lee, L., Samardzic, K., Wallach, M., Frumkin, L. R. & Mochly-Rosen, D. Immunoglobulin Y for potential diagnostic and therapeutic applications in infectious diseases. Front. Immunol. 12, 696003 (2021).

Wallach, M. et al. Eimeria maxima gametocyte antigens: potential use in a subunit maternal vaccine against coccidiosis in chickens. Vaccine 13, 347–354 (1995).

Piccoli, L. et al. Mapping neutralizing and immunodominant sites on the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Receptor-Binding domain by Structure-Guided High-Resolution serology. Cell 183, 1024–1042 e21. (2020).

Greaney, A. J. et al. Comprehensive mapping of mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain that affect recognition by polyclonal human plasma antibodies. Cell. Host Microbe 29, 463–476 (2021).

Liu, L. et al. Potent neutralizing antibodies against multiple epitopes on SARS-CoV-2 Spike. Nature 584, 450–456 (2020).

McCallum, M. et al. N-terminal domain antigenic mapping reveals a site of vulnerability for SARS-CoV-2. Cell 184, 2332–47e16 (2021).

Li, J. et al. Novel neutralizing chicken IgY antibodies targeting 17 potent conserved peptides identified by SARS-CoV-2 proteome microarray, and future prospects. Front. Immunol. 13, 1074077 (2022).

Wongso, H. et al. Preclinical evaluation of chicken egg yolk antibody (IgY) Anti-RBD Spike SARS-CoV-2-A candidate for passive immunization against COVID-19. Vaccines (Basel) 10, 1–17 (2022).

Gujral, N., Löbenberg, R., Suresh, M. & Sunwoo, H. In-Vitro and In-Vivo binding activity of chicken egg yolk Immunoglobulin Y (IgY) against Gliadin in food matrix. J. Agric. Food Chem. 60, 3166–3172 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank Seattle Gourmet Foods for the preparation of the edible tablets used in this study. We also thank Charmaine Chen from ACROBiosystems for their assistance with product selection and supply.

Funding

This study received funding from Camas, Inc., Le Center, MN, USA. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication. All authors declare no other competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MH: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft. BR: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. FA: Data curation, Investigation. AN: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources. PL: Investigation. JH: Investigation. IH: Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft. MW: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The studies involving animals were reviewed and approved by Camas Inc. Animal Care and Use Committee. All laying hens were raised following the National Chicken Council’s recommendations. All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hawkins, M., Robley, B., Alem, F. et al. Mass production of IgY-containing tablets for COVID-19 transmission control. Sci Rep 15, 39487 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23136-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23136-2