Abstract

The Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) enables continuous collection and transmission of healthcare data through interconnected networks of patient wearables and other devices. This capability transforms traditional healthcare systems into data-rich environments. However, this also brings privacy concerns because of the widespread distribution of health data across multiple healthcare systems. Such concerns, including data breaches and privacy violations, become paramount when aggregating data into a centralized location for analytical purposes. Therefore, this paper proposes a novel privacy-preserving framework designed with a three-layer protection mechanism for distributed healthcare analytics on encrypted data. This framework mitigates the risk of data breaches while balancing data privacy with model accuracy tradeoffs. First, fully homomorphic encryption (FHE) is introduced to encrypt healthcare data. This mechanism enables analytical computations while mitigating the risk of data breaches. Building on this, we develop a distributed FHE framework that eliminates the need for centralized data storage and supports iterative learning through continuous model updates as new data become available. Furthermore, we propose a distributed ensemble learning architecture that leverages parallel processing to accelerate the generation of consensus models for healthcare analytics. Experimental results from real-world intensive care unit (ICU) case studies show that the proposed framework effectively protects data privacy while maintaining the performance of analytical models. Moreover, compared with individual departmental models, the proposed privacy-preserving framework achieves the highest accuracy of 84.6%. These findings highlight the potential of a federated privacy-preserving framework to avoid centralized data storage and support collaborative analytics in data-rich healthcare environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) is revolutionizing digital technology in the healthcare sector. By integrating various patient wearables, medical devices, and networking components, smart healthcare systems collect, process, and generate enormous amounts of health-related data. The International Data Corporation predicts that there will be approximately 41.6 billion connected IoT devices to produce about 79.4 zettabytes of data by 20251. As such, this transformation has turned traditional health systems into data-rich environments and offers an unprecedented opportunity to develop innovative analytical methods and tools. For example, a recurrence analysis approach is introduced to support automatic, image-guided identification of invasive ductal carcinoma in breast cancer2. Further, a two-level framework is designed to support data-driven clinical decisions for breast cancer treatment3.

While IoT technologies offer transformative benefits, there is an increasing interest in the protection of data privacy, particularly in different departments of healthcare systems like intensive care units (ICUs). ICU is a data-rich environment where critically ill patients are continuously monitored by advanced devices, enabling rapid risk assessments through both conventional methods and emerging machine learning approaches for mortality prediction and patient stratification. However, this increased connectivity raises significant privacy concerns due to expanded data transmission and the growing complexity of cyber-attacks. Patients’ healthcare data often contain highly sensitive information (e.g., blood pressure and temperature readings). As such, patients are understandably reluctant to permit healthcare units to share their health histories. The HIPAA Journal reports a concerning trend of data breaches in the healthcare sector, with 5887 incidents affecting at least 500 records each between 2009 and 2023. These incidents have compromised approximately 519.94 million healthcare records, exceeding 150% of the United States population. In 2023 alone, the healthcare industry experienced an average of nearly two significant data breaches daily, exposing around 364,570 records per day4. IBM’s 2023 Cost of a Data Breach Report reveals that the average cost of a healthcare data breach in the United States has risen sharply to $10.93 million. This result marks a concerning 53% increase over the past three years5. This rise reflects not only the financial impact but also the potential harm to patient trust and the integrity of healthcare systems. Without robust privacy protections, the expansion of IoMT could result in compromised patient confidentiality and reduced willingness to engage with smart healthcare.

In the current paradigm of large-scale healthcare analytics, data from various independent units or departments within hospitals are often aggregated into a centralized platform to derive broader insights and enhance predictive accuracy. However, this integration is challenging and leads to a complex structure of governance where stringent privacy controls are needed. For example, in 2017, the WannaCry ransomware attack disrupted England’s National Health Service, affecting about one-third of trusts, cancelling thousands of appointments, and incurring an estimated £92 million in service disruption and remediation costs6. As such, there are significant roadblocks to data sharing. For example, aggregating raw data across multiple units or departments into a centralized location raises concerns over data breaches, patient confidentiality, and strict regulatory compliance such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in Europe7 and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) in the United States8. These regulations demand rigorous protection around patient data.

To address privacy concerns in healthcare systems, several standard protocols such as ISO/IEC 291009 have been established to enhance the protection of data privacy. The term “personally identifiable information (PII)” refers to any data that identify an individual. Based on the level of sensitivity, user data are commonly classified into three types: sensitive personal data, general data, and statistical data. Sensitive personal data requires the strictest privacy measures. In contrast, general and statistical data need moderate protection because they are mainly for research or analysis purposes. The PII owners have full control over their data. On the other hand, PII processors, typically units or departments, are granted permission by PII owners to access and utilize their data for specific tasks. The processors might, under certain conditions and with the owners’ agreement, share data with third parties for particular functions. If unauthorized use occurs, both the processors and any third parties involved are held accountable for any breaches in data handling. To reduce the risk of identity disclosure and privacy violations, organizations may use privacy mechanisms such as anonymization and pseudonymization when processing personal data10. Besides, Krall et al. also present a gradient-based mechanism with differential privacy and assess its ability to mitigate malicious attacks in ICUs11.

Overall, healthcare systems currently face significant challenges in maintaining data privacy. First, the widespread use of traditional machine learning models often requires centralized data collection and storage, which greatly increases the risk of data breaches. Second, patients are frequently hesitant to share their raw data due to privacy concerns, which complicates efforts for collaborative decision-making. Lastly, although the adoption of encryption technologies such as the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) can be used to protect data privacy during storage, they limit the computational capabilities available for processing the encrypted data. Hence, it is difficult to exchange data across units for analytical purposes. This situation poses a critical challenge: How can we enable effective analytical computing across distributed datasets owned by different units or individual patients while protecting data privacy?

Hence, this paper proposes a novel privacy-preserving framework designed with a three-layer protection mechanism for distributed healthcare analytics on encrypted data. This framework mitigates the risk of data breaches while balancing data privacy with model accuracy tradeoffs. First, fully homomorphic encryption (FHE) is introduced to encrypt healthcare data to enable analytical computation while mitigating the likelihood of data breaches. After decryption, the outputs are identical to those obtained by applying the same computations to the unencrypted data. Second, a distributed version of FHE framework is developed to obviate the requirement for centralized data storage and enable iterative learning with model updates as new data become available. Third, we present a distributed ensemble learning architecture for healthcare analytics that employs parallel processing to accelerate consensus model generation. Finally, a real-world ICU case study is conducted to evaluate and validate the practical applicability and effectiveness of the proposed privacy-preserving framework. Experimental results from real-world case study show that the proposed framework enables the effective deployment of FHE to healthcare domain, which reduces costs associated with data breaches. Moreover, the proposed framework ensures that the quality of decision-support systems is maintained and provides scalable solutions for privacy-preserving analytics. Both encrypted and unencrypted models perform identically across all metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score. Furthermore, the proposed framework outperforms individual departmental models, achieving 84.6% accuracy, 87.3% recall, 83.4% precision, and 85.31% F1 score.

Results

Experimental design

The rapid advancement of IoMT has created data-rich environments in healthcare systems. Among these, the ICU stands out as a critical department where patients recovering from life-threatening injuries and illnesses require constant monitoring by medical staff. In such high-stakes settings, the development of early and reliable predictive tools for critical medical conditions is necessary to enhance patient care12. As such, a prediction model for ICU mortality is urgently needed to support timely decision-making. In this case study, we employed logistic regression as the predictive model due to its robustness and interpretability in binary outcome prediction, specifically predicting ICU mortality. Also, we consider five distinct departments across different healthcare systems, each independently managing its own dataset. Importantly, data collected from each department are de-identified and share the same format. However, collaborative efforts to develop a predictive ICU mortality model raise data privacy concerns and pose a significant challenge.

In this study, real-world ICU data were obtained from the Multiparameter Intelligent Monitoring in Intensive Care (MIMIC) II Clinical Database, a resource created to support research in intelligent monitoring for critical care patients13. This dataset contains records for 4,000 de-identified patients, each documenting 48 h of ICU stays across various departments, including coronary care, cardiac surgery recovery, medical ICU, and surgical ICU. Also, this dataset includes associated clinical outcomes, indicating either in-hospital death or survival. Previous studies focused on integrating all data into a centralized platform for predictive modeling14. In contrast, this investigation assumes segregated data storage across departments in different healthcare systems. In this case study, there are five independent hospitals collaborating without sharing raw data. Each hospital maintains de-identified data but adopts a common variable dictionary for ICU mortality prediction. We assume participating hospitals align on a shared schema and then apply light harmonization and preprocessing (same feature set, common normalization range, and the same class-rebalancing pipeline) before encrypted training. This reflects what collaborating ICUs typically do in practice, which is collecting similar variables for the shared task and standardizing them enough to enable joint analysis without exchanging raw records. Each of the five departments, labeled as departments 1 through 5, holds a distinct dataset with varying numbers of patient records: 500, 700, 1100, 1000, and 700 data points, respectively. ICU mortality data are sequentially collected as patients are treated in each department. The prediction model is iteratively updated when new data become available.

Prior to federated training, the collaborating ICUs first agreed on a common data dictionary and a deterministic preprocessing script. First, feature selection and preprocessing were carried out following the approach proposed by Chen et al.15. Next, data normalization was performed to ensure the input variables ranged between − 1 and 1. Third, the observed outcomes are highly imbalanced, with 3,446 negative (survival) and 554 positive (in-hospital death) instances. This imbalance can lead to machine learning models exhibiting high accuracy but low recall, precision, and F1 scores. This trend indicates a bias toward the majority class. To address this issue, data were balanced using the BorderlineSMOTE16 and Tomek-Links17 techniques to result in around 3,400 data points for each class. The ring dimension of FHE is 16,384, the total coefficient modulus is 218 bits (e.g., [60, 40, 40, 40, 38]), and the security level is 128 bits.

Subsequently, due to limitations of the FHE algorithm, certain equations (e.g., Sigmoid function in logistic regression) cannot be directly performed. As a result, a polynomial approximation is employed to approximate the Sigmoid function. Coefficients are obtained by minimizing the maximum approximation error on [− 6,6] via Remez exchange. Various polynomial orders are compared to determine the most suitable approximation based on performance metrics and computational efficiency. The polynomial approximations considered in this case study are as follows:

-

Cubic polynomial approximation \({\sigma }_{3}\left(\mathcal{z}\right)\)

$$\sigma_{3} \left( z \right) = 0.5 + 1.201 \cdot \left( \frac{z}{8} \right) - 0.816 \cdot \left( \frac{z}{8} \right)^{3}$$ -

Quintic polynomial approximation \({\sigma }_{5}\left(\mathcal{z}\right)\)

$${\upsigma }_{{5}} \left( z \right){ = 0}{\text{.5 + 1}}{.53} \cdot \left( {\frac{z}{{8}}} \right){ - 2}{\text{.353}} \cdot \left( {\frac{{\text{z}}}{{8}}} \right)^{{3}} { + 1}{\text{.351}} \cdot \left( {\frac{z}{{8}}} \right)^{{5}}$$ -

Septic polynomial approximation \({\sigma }_{7}\left(\mathcal{z}\right)\)

$${\upsigma }_{{7}} \left( z \right){ = 0}{\text{.5 + 1}}{.735} \cdot \left( {\frac{z}{{8}}} \right){ - 4}{\text{.194}} \cdot \left( {\frac{z}{{8}}} \right)^{{3}} { + 5}{\text{.434}} \cdot \left( {\frac{z}{{8}}} \right)^{{5}} { - 2}{\text{.507}} \cdot \left( {\frac{z}{{8}}} \right)^{{7}}$$

Performance metrics such as accuracy, recall, precision, and F1 score are then obtained from a non-private framework, which serves as a baseline to measure the model performance and risk in predicting patient mortality. Next, the proposed privacy-preserving framework is then implemented to allow comparisons against a non-private framework. This study further evaluates the integration of ensemble learning within the proposed privacy-preserving framework in terms of both computational efficiency and model performance. Finally, the framework’s ability to protect data privacy is discussed in detail.

Approximation of sigmoid function

First, polynomial approximation functions of varying orders are adopted to approximate the Sigmoid function, with each order impacting the approximation accuracy. As shown in Fig. 1, we compare the Sigmoid function with polynomial approximations of three different orders over the domain from − 6 to 6. A cubic polynomial provides a rough approximation of the Sigmoid function, while higher-order polynomials yield more accurate approximations that closely resemble the Sigmoid curve. Next, this study evaluates the predictive performance by comparing the use of the Sigmoid function with these three polynomial approximations. The comparison focuses on the following key metrics: accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score.

As shown in Fig. 2a, the machine learning model with Sigmoid function achieves the highest accuracy at approximately 81.2%. In comparison, accuracies with cubic, quintic, and septic polynomial approximations are slightly lower, at 80.7%, 81%, and 81.1%, respectively. It may be noted that the accuracy difference between cubic and quintic approximations is more significant than that between the quintic and septic approximations. Precision results, shown in Fig. 2b, follow a similar trend. The Sigmoid function yields the highest precision at 80%, while the cubic, quintic, and septic polynomial approximations achieve 79.1%, 79.5%, and 79.7%, respectively. Precision gradually improves as the polynomial order increases. However, as shown in Fig. 2c, the Sigmoid function does not yield the highest recall. Instead, quintic polynomial approximation achieves the highest recall at 84.6%. This result indicates that this machine learning algorithm with the quintic polynomial approximation is particularly effective at identifying positive cases and minimizing the number of false negatives. Subsequently, F1 scores are compared in Fig. 2d. The Sigmoid function again achieves the highest F1 score at 82.1%, slightly surpassing scores of 81.7% for cubic, 81.9% for quintic, and 82% for septic approximations. In conclusion, while the quintic polynomial approximation is effective at identifying the most positive instances, it produces a relatively high number of false positives, which leads to lower precision.

Besides, as shown in Fig. 3, when considering computational efficiency, the machine learning algorithm using the Sigmoid function directly takes less than 1 s to execute one iteration. However, if data are encrypted by FHE and polynomial approximations are used to simulate the Sigmoid function, computation time increases. Specifically, the cubic, quintic, and septic polynomial approximations require around 33, 43, and 54 s per iteration, respectively. Given the similarity in model performance between quintic and septic approximations observed in previous experiments, this study selects the quintic polynomial approximation for estimating the Sigmoid function. This choice balances the tradeoff between model performance and computational efficiency.

Comparative analysis of the proposed model with versus without FHE

We then evaluate and validate the impact of data encryption and computational operations on prediction performance. Specifically, we compare the performance of a machine learning model using a quintic polynomial approximation under two scenarios: one with FHE and the other without FHE. Experimental results show that both models perform identically across all metrics, achieving an accuracy of 81%, a precision of 79.5%, a recall of 84.6%, and an F1 score of 81.9%. There is no significant performance difference. As a result, the proposed privacy-preserving framework does not compromise model performance when FHE is leveraged to protect data privacy. Besides, Table 1 reports the per-site, per-round communication cost. The unencrypted baseline exchanges about 2.2 KB and adds less than one millisecond. With FHE encryption, the round trip rises to approximately 727 KB, which corresponds to roughly 58 ms of transfer time per round. This increase reflects the larger encrypted data yet remains modest at typical hospital link speeds.

Impact of ensemble learning on computational time and model performance

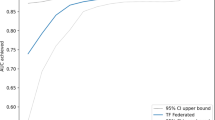

FHE, while providing strong data privacy protection, is also characterized by significant computational complexity. To address this challenge, we compare the computational efficiency of our proposed distributed ensemble learning architecture with a serial-computing version of the predictive model. The computational time required is directly influenced by the number of sub-models within the ensemble; in our evaluation, we considered configurations ranging from 1 to 15 sub-models. As shown in Fig. 4, the serial-computing version is used as the baseline, defined as 100%, and when only one sub-model is used, the system operates in a serial-computing mode. The experiential results indicate that computational time decreases as the number of sub-models increases; however, beyond 7 sub-models, the rate of improvement in computational time begins to slow considerably, even as additional sub-models are added.

In contrast, Fig. 5 shows the changes in prediction performance with an increasing number of sub-models. First, as the number of sub-models grows, there is a notable improvement in accuracy. However, beyond 7 sub-models, accuracy gains stabilized, with accuracy increasing from 81.4% to 84.5%, representing a 3% improvement compared to a single main model. We also compare precision and recall across various numbers of sub-models. As shown in Fig. 5b and c, the performance stabilizes when the number of sub-models exceeds 7, with a precision of around 84% and a recall of approximately 87%, albeit performance varies when the number of sub-models is fewer than 7. Notably, with 5 sub-models, the precision is the highest among the various configurations. However, the recall at this configuration is relatively low. This indicates that, although the ensemble model with 5 sub-models demonstrates high reliability in positive predictions, it misses a substantial portion of actual positive cases. As such, a trade-off exists between precision and recall when the number of sub-models is set to 5. Lastly, Fig. 5d shows the comparison of F1 scores as the number of sub-models grows. Overall, the F1 score reflects the trends seen in precision and recall. When the sub-model count surpasses 7, the F1 score stabilizes and reaches the highest value at approximately 85%. Therefore, 7 sub-models are selected as the optimal configuration to provide a balance between computational efficiency and model performance.

Performance comparison between privacy-preserving framework and local departmental models

Furthermore, we compare the performance of the proposed privacy-preserving framework employing 7 sub-models with individual models developed by departments 1 through 5. Notably, each department independently trained its own model using only local data. Predictive performance is evaluated using metrics including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score. Figure 6a shows accuracy variations among these 6 machine learning models. The proposed framework yields the highest accuracy at 84.6%, outperforming individual departmental models. It is worth noting the variation in performance among departments 1 to 5; for example, the model of department 2 has an accuracy that is 7% higher than department 1. This indicates significant differences in model performance when relying on isolated datasets. Figure 6b and c further show differences in precision and recall among different models. Experimental results indicate that the proposed framework is more effective in correctly identifying positive cases and minimizing false negatives. Specifically, the proposed framework achieves a recall of approximately 87.3% and a precision of around 83.4%. When departments collaborate through federated learning, recall and precision improve by up to 10.8% and 6.2%, compared to independent models. Lastly, Fig. 6d presents F1 score comparisons, which balance precision and recall. The proposed framework consistently achieves the highest F1 score of 85.31%. In contrast, independent models developed by departments 1 to 5 record F1 scores of 78.42%, 82.7%, 81.51%, 81.59%, and 81.9%, respectively. These results highlight the superior performance of proposed privacy-preserving framework in maintaining a balanced prediction performance among different departments of healthcare systems.

Resistance to attacks

To mitigate cyberattacks, including offline attempts and cryptanalytic attacks, the proposed framework reduces the likelihood of data exposure. For offline attacks such as dictionary and brute-force guessing, the framework uses cryptographically secure generation of public–private key pairs and long key sizes. This enlarges the search space to a level where key guessing becomes practically infeasible and the success probability is negligible; for cryptanalytic attacks, the framework isolates each site with its own independent key pair. Keys are not fixed or shared across factories. Under known-plaintext and chosen-ciphertext models, this key isolation limits cross-site exposure and makes it harder for an attacker to recover sensitive data from intercepted ciphertexts.

Privacy analysis and comparison

Last, the proposed privacy-preserving framework is compared with alternative privacy-preserving paradigms such as differential privacy (DP), indistinguishability under chosen-plaintext (IND-CPA), chosen-ciphertext (IND-CCA), and secure multi-party computation (MPC). DP protects individuals by adding calibrated noise to query results. This guarantee is attractive when many parties need summary statistics. However, the cost is accuracy. Noise lowers fidelity and tight privacy budgets limit repeated analyses. In our study, computations run on encrypted data and return exact results after decryption, so model utility is preserved.

Classical encryption notions such as IND-CPA and IND-CCA secure data at rest and in transit, but they do not support learning on ciphertexts. Our framework enables training and inference directly over encrypted records, so collaborating units never decrypt each other’s data. This expands the role of encryption from passive protection to active analytics while keeping confidentiality guarantees. MPC allows parties to compute jointly without sharing raw inputs, yet general MPC protocols incur heavy interaction and communication rounds and can be difficult to compose for end-to-end pipelines. Here, each site trains locally on its own encrypted data and shares only encrypted model updates for aggregation. This design avoids the round-trip patterns common in general MPC and keeps the programming interface close to standard training.

Taken together, the framework delivers three advantages against the state of the art. First, exact model utility without DP-induced noise during learning; second, stronger functionality than classical IND-CPA/IND-CCA storage/transport encryption because analytics proceed on encrypted data; third, lower interaction complexity than general MPC by using local encrypted training with lightweight update sharing.

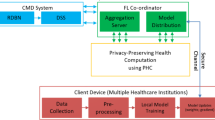

Three‑layer data protection in collaborative healthcare analytics

As shown in Fig. 7, the proposed privacy-preserving framework is designed to mitigate the severe consequences of data breaches, even in the event of a successful cyberattack on the system. First, under layer 1 protection, segregated data storage ensures that a breach in one unit (or department within the hospital) only exposes raw data from that specific unit. Data from other units remain secure due to segregated data storage. Second, under layer 2 protection, a hacker would only have access to encrypted data. Without the corresponding private keys, hackers cannot interpret the encrypted patient data. Third, under layer 3 protection, should any data exposure occur, hackers could access only encrypted data and model parameters from a single unit because the model training process is distributed across facilities. Thus, the proposed framework greatly lowers the risk of data breaches in collaborative healthcare analytics and allows multiple departments to work together securely on predictive model development without compromising the patient data privacy.

Discussion and conclusions

Fully homomorphic encryption (FHE) stands as a key technology for secure computation and has evolved to become practically applicable in real-world use. This encryption method enables arithmetic computations to be performed directly on encrypted data without requiring decryption. As such, data privacy is protected from potential risks during processing. Initially proposed in the 1970s by Rivest et al., FHE was long considered either impractical or prohibitively complex for real-world implementation18. A major breakthrough occurred in 2009 when Gentry introduced the first viable FHE scheme. This scheme was capable of handling arithmetic computations on encrypted data. Gentry not only presented this initial FHE scheme but also developed a methodology to transform a partially homomorphic encryption scheme with limited evaluation capacity into a fully homomorphic one19.

Following Gentry’s work, there has been a surge in research and development efforts aimed at enhancing homomorphic encryption. This has led to the creation of several advanced FHE schemes, notably including the Brakerski-Gentry- Vaikuntanathan (BGV)20, Fan-Vercauteren (FV)21, and Cheon-Kim-Kim-Song (CKKS)22. Each contributes to the diversification and advancement of FHE technologies. FHE now has a wide range of applications across various domains. In machine learning, FHE enables privacy-preserving computation, supporting applications from simple linear regression models23 to complex tasks like encrypted neural network inference24. In the healthcare sector, FHE enhances data privacy in analysis, as seen in its integration with the k-means algorithm to investigate disease risk factors25.

However, integrating FHE into federated learning for smart healthcare systems remains in its early stages, with limited exploration of its potential benefits. The healthcare sector, now more than ever, calls upon the development of privacy-preserving frameworks. This research gap highlights an urgent need to develop FHE-enhanced federated learning approaches and establish multi-layer protection of data privacy.

In this study, we assume that each participating hospital has sufficient computational resources to support FHE, that all partners treat data privacy as the primary objective, and that our threat model centers on cyber-attacks against healthcare data and analytics pipelines. Under this setting, the case study shows a clear trade-off between privacy and cost. When privacy leads, the goal is to minimize overhead in time, money, and computational resources while keeping protections intact. These results suggest concrete changes for practice. Privacy should not be managed as a single number in a table; it protects real patients. Hospitals should reorganize data storage and usage to reflect this priority. For example, using privacy-preserving analytics by default, restricting access paths, and reviewing retention and reuse policies so that secondary analysis does not weaken protections. Although the proposed framework can protect data privacy, time and cost are the main constraints at present. Although we reduce overhead where possible, running encrypted analytics across sites still demands additional runtime and operational effort, which we plan to lower with engineering advances and resource sharing.

Beyond implementation of the proposed framework in ICUs, it has broader implications for healthcare systems at large. By enabling secure, privacy-preserving collaborative analytics, it can improve decision-making and resource allocation across various healthcare domains, which are from chronic disease management to emergency response and beyond. Furthermore, the proposed framework is readily adaptable to existing healthcare IT infrastructures. It facilitates integration with electronic health record systems and other digital platforms. As healthcare institutions increasingly recognize the value of data-driven insights, adopting such a framework can enhance inter-institutional collaboration, improve patient outcomes, and resist cyber threats. The results of this investigation show the potential of proposed framework to protect patient privacy while driving innovation in healthcare analytics.

For the general clinical practice, we summarize who benefits from this work, how they benefit, and how we will reach them.

-

1.

ICU clinical teams benefit from more consistent mortality prediction and patient stratification across sites while keeping data private, supporting earlier recognition of high-risk patients.

-

2.

Hospital departments and enterprise IT/security benefit from collaborative model development without moving raw data, a reduced breach blast-radius through segregated storage, encryption, and distributed training, and lower compliance risk.

-

3.

Health information exchanges and multi-center consortia benefit from a hub that aggregates encrypted model updates only, enabling cross-site learning with minimal handling of identifiable data.

-

4.

Patients and advocacy groups benefit from stronger privacy protection with maintained model performance, which can strengthen trust in data-driven care.

We will first release a reproducible specification pack with preprocessing templates, parameter settings, and synthetic examples. Second, we can share implementation guides and webinars for ICU leads, chief information officers (CIOs), and chief information security officers (CISOs) through professional societies. Third, a short technical brief can be published for health-IT vendors and standards groups to assist integration. Last, we can provide a plain-language summary and results at clinical informatics and healthcare analytics venues for patient communities.

Outside healthcare, the proposed privacy-preserving framework can generalize to other regulated and data-sensitive domains. Representative use cases include financial services for cross-institution fraud detection and credit risk modeling; manufacturing and supply chains for federated quality analytics and predictive maintenance across plants26; energy and utilities for load forecasting and grid anomaly detection from encrypted smart-meter data. In each case, parties agree on a common data dictionary and deterministic preprocessing, compute encrypted updates locally, and fuse sub-models into a consensus model to balance accuracy and computational cost while reducing breach exposure.

FHE introduces notable computational cost yet remains important for protecting patient data privacy across clinical narratives, imaging, laboratory results, and continuous monitoring data. In healthcare, confidentiality is a core requirement rather than a preference. When exposure risks carry operational and reputational consequences, a privacy preserving framework is warranted despite higher computational demand. This rationale supports strategic investment in data protection, since the value of protecting sensitive data exceeds the additional resources required for computation. This study characterizes the resource implications of alternative protection strategies and affirms the centrality of privacy in healthcare practice. Efficiency can be improved within federated learning through algorithmic designs that streamline encrypted processing, hardware acceleration, and large-scale parallelization frameworks such as MapReduce, which together can reduce processing time while maintaining privacy.

The security of our privacy-preserving framework relies on the RLWE assumption. RLWE enjoys worst-case-to-average-case reductions from standard problems on ideal lattices (e.g., approximate shortest vector problem (SVP)/shortest independent vectors problem (SIVP)) and is conjectured hard against both classical and quantum attackers. This hardness underpins CKKS schemes; with conservative choices of parameters of FHE, it supports the targeted 128-bit security level.

This study acknowledges that there are several models such as neural network can be adopted to predict ICU mortality. Here, logistic regression is selected as a demonstrative model to evaluate the proposed privacy-preserving framework. A key challenge is that the sigmoid is not directly computable on encrypted data, so we replace it with a low-degree polynomial approximation that runs under encryption with minimal loss of accuracy. More generally, we would like to demonstrate a practical rule. When any model equation cannot be directly computed on encrypted data, it can be substituted with a tractable approximation while preserving the model’s intent. Future work may consider to further extend the proposed privacy-preserving framework to other machine learning model.

Differential privacy27 provides a formal guarantee that the inclusion or exclusion of any individual in the dataset cannot be reliably inferred. In future work, we will further investigate combining differential privacy with our framework, for example adding calibrated noise to model updates before homomorphic encryption. This multi-layer defense is intended to strengthen privacy protection while preserving model utility.

In summary, this paper proposes a novel privacy-preserving framework designed with a three-layer protection mechanism for distributed healthcare analytics on encrypted data. With the mechanism of federated learning and FHE, the proposed framework eliminates the centralized data storage requirements. Instead, model development is decentralized and operates entirely on encrypted data. Additionally, the proposed framework leverages an ensemble learning approach to enhance both computational efficiency and model performance to ensure the system can handle complex, distributed datasets while maintaining high levels of privacy protection.

Methods

This paper proposes a novel privacy-preserving framework designed with a three-layer protection mechanism for distributed healthcare analytics on encrypted data. The proposed framework comprises the following three components:

Computation on encrypted data

FHE enables analytical computations to be performed directly on encrypted data. Thus, the proposed framework mitigates the risk of data breaches and preserves patient privacy throughout the analytical process.

Decentralized on‑site learning

The proposed framework employs decentralized model training across multiple healthcare units without the need to exchange raw data. Each unit trains its model locally and shares only model updates with a central server. This federated learning design in smart healthcare systems ensures that sensitive patient data remain confidential while still enabling collaborative analytics.

Collective intelligence of models

To enhance computational efficiency and model performance, ensemble learning is utilized within a parallel computing architecture. Multiple sub-models are trained simultaneously and then integrated into a consensus model. This parallelism accelerates the computational process and provides scalable analysis of large-scale healthcare data.

As shown in Fig. 7, the interactive workflow of these layers ensures that raw data are never exchanged between units, while still allowing continuous model refinement and enhanced predictive performance. Integrated interaction between data segregation, FHE encryption, and federated ensemble learning forms the backbone of a privacy-preserving framework for healthcare analytics. The workflow is determined by problem constraints in distributed healthcare system.

Segregated data storage

In the context of IoMT, healthcare data are collected from diverse sources, including wearable devices, sensors, and medical equipment, and are distributed across different units or departments of healthcare systems. Notably, a single unit only provides care to a small number of patients, while different units often treat diverse patient populations. For instance, one pediatric unit may primarily handle a small pool of cases, while the other focuses on specific patients with chronic conditions. This variation results in distributed data that reflect only specific patient populations. As such, units are left with a limited perspective on broader healthcare trends and patient conditions. To obtain a comprehensive view of healthcare trends and patient conditions, collaboration among multiple units across healthcare systems is needed. However, such collaboration introduces significant concerns regarding data privacy, especially when sharing sensitive patient data.

Data storage is crucial for protecting data privacy and enabling efficient operations. Currently, segregated data storage is a common structure where each unit or department across healthcare systems retains full control over its dataset. Data are stored independently. This structure supports a high level of data privacy protection because each unit enforces its privacy protocols to minimize the risk of unauthorized access. However, while segregated data storage helps protect data privacy, the potential for data-driven collaboration across multiple independent healthcare systems is limited. Units face challenges in coordinating care because isolated datasets prevent comprehensive patient records from being assembled. Such limitations reduce insights that could improve diagnostics, treatments, and patient outcomes. As a result, while effective for privacy, segregated data storage hinders the broader goals of an integrated healthcare system.

On the other hand, aggregated data storage is another structure where multiple units across healthcare systems contribute to a unified, collaboratively managed dataset. In this setup, data storage responsibilities are shared among all participating units or departments. This structure enables access to a more extensive dataset that can reveal patterns and insights across patient populations. Aggregated data storage supports more effective disease tracking, personalized treatment strategies, and improved diagnostics. However, this structure poses unique challenges in maintaining patient privacy because of the increasing level of complexity when multiple units have access to the same dataset. Without privacy-preserving mechanisms such as data encryption, anonymization techniques, and controlled access protocols, patients’ sensitive data are at risk. The balance between maximizing the value of shared data and protecting data privacy remains a pressing concern in IoMT.

To address these challenges, it is imperative to develop a privacy-preserving framework for distributed learning in healthcare systems. Such a framework can enable units across healthcare systems to collaborate on data analytics while protecting sensitive patient data. As shown in Fig. 8, the proposed privacy-preserving framework consists of three-layer protection. Patient data from various devices and sensors are standardized and de-identified at each healthcare unit to ensure that data remain localized and compliant with privacy requirements. (Layer 1: Data Segregation). These segregated data are then encrypted by FHE to enable analytical computation without decryption and mitigate the likelihood of data breaches (Layer 2: Data Encryption). The encryption layer interacts with the decentralized learning layer, where federated learning is employed to collaboratively train machine learning models across multiple units. In this process, each unit processes its encrypted data locally and transmits only model updates to a central server. These updates are then integrated using ensemble learning techniques, which combine the strengths of multiple sub-models into a consensus model. (Layer 3: Decentralized Learning). The interactive workflow of these layers ensures that raw data are never exchanged between units, while still allowing continuous model refinement and enhanced predictive performance. Integrated interaction between data segregation, FHE encryption, and federated ensemble learning forms the backbone of a privacy-preserving framework for healthcare analytics.

Computation on encrypted data

FHE, a novel encryption technique, goes a step further by allowing computations to be conducted directly on encrypted data. As a form of asymmetric encryption, two distinct keys are utilized: a public key (\(pk\)) and a private key (\(sk\)). Notably, the public key is to encrypt the raw data, and the private key is to decrypt it. A significant advantage of FHE is that, upon decryption, the results of these computations are identical to those obtained by performing on raw data. This capability allows data processing and analysis while preserving data privacy.

As shown in Fig. 9, there are K departments in the healthcare system. Department \(k\) independently manages its data \({\left[\mathbf{X},\mathbf{Y}\right]}^{\left(k\right)}\), where \(\mathbf{X}\) denotes the matrix of input variables, and \(\mathbf{Y}\) is the matrix of output values in the process of healthcare analytics. Each department \(k\) owns its key pair, including the public key \({pk}^{\left(k\right)}\) and the private key \({sk}^{\left(k\right)}\). Upon data collection, department \(k\) encrypts the raw data using \({pk}^{\left(k\right)}\) into \({\left[{\mathbf{X}}_{e} , {\mathbf{Y}}_{e}\right]}^{\left(k\right)}\). Notably, this encrypted data can only be decrypted by department \(k\), which holds the corresponding private key \({sk}^{\left(k\right)}\). When department \(k\) conducts analytical computation such as addition or multiplication on encrypted data, FHE ensures that the operations yield accurate results. For instance, if an addition operation is defined as \(F\left({x}_{e},{ y}_{e}\right)\text{=}{ x}_{e}\text{+}{y}_{e}\), decrypting the result with the \({sk}^{\left(k\right)}\) produces the same outcome as \(x\text{+}y\). Similarly, for a multiplication operation defined as \(F\left( {x_{e} , y_{e} } \right){ = } x_{e} \times y_{e}\), decrypting the result yields an outcome identical to \(x \times y\).

In the proposed framework, each unit or department \(k\) of healthcare systems generates a key pair, including a private key \({sk}^{\left(k\right)}\) and a public key \({pk}^{\left(k\right)}\), following the assumption of Ring Learning with error (RLWE)28. Define

as the cyclotomic ring, where \(n\) is a power of two and \({\mathbb{Z}}\left[X\right]\) is defined as the polynomial ring with integer coefficients. The residue ring \({R}_{q}\text{=}{\mathbb{Z}}_{q}\left[X\right]/\left({X}^{n}\text{+}1\right)\) operates with coefficients modulo \(q\). Key generation utilizes polynomials in the form \(\left( {a^{\left( k \right)} ,b^{\left( k \right)} { = - }s^{\left( k \right)} \cdot a^{\left( k \right)} { + }e} \right)\) . Per the RLWE assumption, \({b}^{\left(k\right)}\) is indistinguishable from uniformly random elements in \({R}_{q}\) when \({a}^{\left(k\right)}\) is selected uniformly at random from \({R}_{q}\), \({s}^{\left(k\right)}\) is drawn from \({R}_{q}\), and \(e\) is sampled from a uniform distribution over \({R}_{q}\). The fundamental settings of FHE algorithm are outlined below.

-

Private key setup: For each unit \(k\), the private key \({sk}^{\left(k\right)}\) is defined as:

$$\begin{array}{c}{sk}^{\left(k\right)}\text{=}\left(1,{s}^{\left(k\right)}\right)\#\end{array}$$(2) -

Public key setup: The public key \({pk}^{\left(k\right)}\) of unit \(k\) is defined by the following equation:

$$\begin{array}{*{20}c} {pk^{\left( k \right)} { = }\left( {b^{\left( k \right)} ,a^{\left( k \right)} } \right){ = }\left( {{ - }s^{\left( k \right)} \cdot a^{\left( k \right)} { + }e,a^{\left( k \right)} } \right)} \\ \end{array}$$(3) -

Encryption \({\text{Enc}}\left(\cdot \right)\): The FHE takes a raw data \({x}^{\left(k\right)}\) and the public key \({pk}^{\left(k\right)}\) from unit \(k\) as input and outputs an encrypted data \({x}_{e}^{\left(k\right)}\) as follows:

$$\begin{aligned} x_{e}^{\left( k \right)} { = } & \,{\text{Enc}}\left( {pk^{\left( k \right)} ,x^{\left( k \right)} } \right) = \left( {x^{\left( k \right)} ,0} \right){ + }pk^{\left( k \right)} \\ = & \left( {x^{\left( k \right)} { - }s^{\left( k \right)} \cdot a^{\left( k \right)} { + }e,a^{\left( k \right)} } \right) \\ = & \left( {c_{0}^{\left( k \right)} ,c_{1}^{\left( k \right)} } \right) \\ \end{aligned}$$(4) -

Decryption \({\text{Dec}}\left(\cdot \right)\): The FHE decryption process takes the encrypted data \({x}_{e}^{\left(k\right)}\) and the private key \({sk}^{\left(k\right)}\) as input and generates a decrypted data \({\widetilde{x}}^{\left(k\right)}\) as follow:

$$\begin{aligned} \tilde{x}^{\left( k \right)} = &\, {\text{Dec}}\,\left( {sk^{\left( k \right)} ,x_{e}^{\left( k \right)} } \right) \\ = &\, c_{0}^{\left( k \right)} { + }c_{1}^{\left( k \right)} \cdot s^{\left( k \right)} \\ = & \left( {x^{\left( k \right)} { - }s^{\left( k \right)} \cdot a^{\left( k \right)} { + }e} \right){ + }a^{\left( k \right)} \cdot s^{\left( k \right)} \\ = & x^{\left( k \right)} { + }e \\ \approx & x^{\left( k \right)} \\ \end{aligned}$$(5)

Two key properties of FHE are described below:

-

Additive homomorphism \({\text{Add}}\left(\cdot \right)\): Suppose unit \(k\) has two data point \({x}^{\left(k\right)}\) and \({y}^{\left(k\right)}\), which are encrypted as follows:

$$\begin{array}{c}{x}_{e}^{\left(k\right)}\text{=}\,{\text{E}}{\text{n}}{\text{c}}\left({pk}^{\left(k\right)},{x}^{\left(k\right)}\right)\text{=}\left({c}_{x,0}^{\left(k\right)},{c}_{x,1}^{\left(k\right)}\right)\end{array}$$(6)$$\begin{array}{c}{y}_{e}^{\left(k\right)}\text{=}{\text{E}}{\text{n}}{\text{c}}\left({pk}^{\left(k\right)},{y}^{\left(k\right)}\right)\text{=}\left({c}_{y,0}^{\left(k\right)},{c}_{y,1}^{\left(k\right)}\right)\end{array}$$(7)to mitigate the risk of data breaches while computing data analysis. When an addition operation is demanded, the encrypted sum of \({x}_{e}^{\left(k\right)}\) and \({y}_{e}^{\left(k\right)}\) is calculated as follows:

$$\begin{aligned} {\text{Add}}\left( {x_{e}^{\left( k \right)} ,y_{e}^{\left( k \right)} } \right) = & x_{e}^{\left( k \right)} { + }y_{e}^{\left( k \right)} \\ = & \left( {c_{x,0}^{\left( k \right)} ,c_{x,1}^{\left( k \right)} } \right){ + }\left( {c_{y,0}^{\left( k \right)} ,c_{y,1}^{\left( k \right)} } \right) \\ = & \left( {c_{x,0}^{\left( k \right)} { + }c_{y,0}^{\left( k \right)} ,c_{x,1}^{\left( k \right)} { + }c_{y,1}^{\left( k \right)} } \right) \\ \end{aligned}$$(8)When the result of \({\text{Add}}\left({x}_{e}^{\left(k\right)}\text{+}{y}_{e}^{\left(k\right)}\right)\) is decrypted by \({sk}^{\left(k\right)}\), the outcome is the same as the addition of raw data \({x}^{\left(k\right)}\text{+}{y}^{\left(k\right)}\), as shown below:

$$\begin{aligned} {\text{Dec}} & \left( {sk^{\left( k \right)} ,{\text{Add}}\left( {x_{e}^{\left( k \right)} ,y_{e}^{\left( k \right)} } \right)} \right) = \left( {c_{x,0}^{\left( k \right)} + c_{y,0}^{\left( k \right)} } \right){ + }\left( {c_{x,1}^{\left( k \right)} + c_{y,1}^{\left( k \right)} } \right) \cdot sk^{\left( k \right)} \\ = & \left( {c_{x,0}^{\left( k \right)} + c_{x,1}^{\left( k \right)} \cdot sk^{\left( k \right)} } \right) + \left( {c_{y,0}^{\left( k \right)} + c_{y,1}^{\left( k \right)} \cdot sk^{\left( k \right)} } \right) \\ = & \left( {x^{\left( k \right)} + e} \right) + \left( {y^{\left( k \right)} + e} \right) \approx x^{\left( k \right)} + y^{\left( k \right)} \\ \end{aligned}$$(9) -

Multiplicative homomorphism \({\text{Multi}}\left(\cdot \right)\): Conversely, if unit \(k\) has one encrypted data \({x}_{e}^{\left(k\right)}\) and performs multiplication by a non-sensitive real number \(t\), which does not need encryption, the multiplication function is defined as follows:

$$\begin{aligned} {\text{Multi}}\left( {x_{e}^{\left( k \right)} ,t} \right) =\, & x_{e}^{\left( k \right)} \cdot t \\ = & \left( {c_{x,0}^{\left( k \right)} ,c_{x,1}^{\left( k \right)} } \right) \cdot t \\ = & \left( {c_{x,0}^{\left( k \right)} \cdot t,c_{x,1}^{\left( k \right)} \cdot t} \right) \\ \end{aligned}$$(10)

When the private key \({sk}^{\left(k\right)}\) is utilized to decrypt this result, the decryption yields:

Furthermore, if data \({x}^{\left(k\right)}\) and \({y}^{\left(k\right)}\) are sensitive and used in the multiplication function, unit \(k\) has to encrypt them as \({x}_{e}^{\left(k\right)}\) and \({y}_{e}^{\left(k\right)}\). The multiplication function for two encrypted data is defined as follows:

Here, it is important to note that \({\text{Dec}}\left(\cdot \right)\) is typically a quadratic polynomial. However, as shown in the above equation, \({\text{Dec}}\left({sk}^{\left(k\right)},{\text{Multi}}\left({x}_{e}^{\left(k\right)},{y}_{e}^{\left(k\right)}\right)\right)\) now becomes a cubic polynomial. As a result, relinearization \({\text{ReLin}}\left(\cdot \right)\)29 is adopted to make \({\text{Dec}}\left({sk}^{\left(k\right)},{\text{Multi}}\left({x}_{e}^{\left(k\right)},{y}_{e}^{\left(k\right)}\right)\right)\) still be a quadratic polynomial. The relinearization process is defined as follows:

where \(d_{0}^{\prime } { + }d_{1}^{\prime } \cdot s^{\left( k \right)} { = }d_{0} { + }d_{1} \cdot s^{\left( k \right)} { + }d_{2} \cdot s^{\left( k \right)2}\). Consequently, the decryption of relinearized result yields:

Federated learning and predictive analytics

IoMT leverages vast, diverse, and high-quality data to enhance healthcare capabilities. However, collaboration among multiple units or departments introduces a risk of data breaches. To mitigate this risk, a federated learning framework offers an effective solution by circumventing the need for centralized data storage. Models are trained locally at each unit to keep data securely within its original environment. This decentralized framework enhances data privacy while still supporting the benefits of collaborative learning. This research introduces a federated learning framework tailored to the IoMT context to increase data utility while protecting privacy.

As shown in Fig. 10, a network of \(\text{K}\) departments collaborate across healthcare systems. Each department stores its own dataset, denoted as \({\mathcal{D}}^{\left(k\right)}\text{=}\left({\mathbf{x}}_{i}^{\left(k\right)},{y}_{i}^{\left(k\right)}\right)\), where \(i\text{=}1,\dots ,{N}^{\left(k\right)}\). Here, \({\mathbf{x}}_{i}^{\left(k\right)}\) represents the \({i}^{th}\) input vector for department \(k\), \({y}_{i}^{\left(k\right)}\) corresponds to the \({i}^{th}\) output, and \({N}^{\left(k\right)}\) specifies the total amount of data at department \(k\). Each department securely stores its data and further develops machine learning models. Variations in patient demographics, hospital resources, and other factors contribute to differences in datasets across departments. Subsequently, a consensus model synthesizes the insights from these individual models to create a unified machine learning model.

In a multi-entity collaboration setting, this research illustrates the federated learning framework by utilizing logistic regression as an example in healthcare systems. First, each unit or department encrypts its raw data as follows:

Here, the logistic regression is defined as

where \(p\) represents the probability of outcome \(y\text{=}1\), \({\mathbf{x}}_{e}^{\left(k\right)}\) is the encrypted input vector from the \({k}^{th}\) unit, \({{\varvec{\upbeta}}}^{\left(t-1\right)}\) denotes the parameters vector updated for \(t-1\) times. Notably, \(p\left({\mathbf{x}}_{e}^{\left(k\right)},{\varvec{\upbeta}}\right)\) is defined as the probability of outcome \(y\text{=}1\) on the given encrypted input \({\mathbf{x}}_{e}^{\left(k\right)}\) and the model parameters \({\varvec{\upbeta}}\). After rearranging the above equation, we can have

The model parameters are estimated through maximum likelihood estimation (MLE), defined as the joint probability density of healthcare data from unit \(k\) conditioned on a given set of model parameters. Therefore, the joint likelihood function for the training data from unit \(k\) is defined as

Taking the logarithm transforms products into sums as follows:

The objective of MLE is to determine the optimal parameter set \({{\varvec{\upbeta}}}^{\boldsymbol{*}}\) of model that maximizes the log-likelihood function:

Model parameters \({\varvec{\upbeta}}\) are iteratively updated as follows:

Due to the constraints of FHE, directly implementing the Sigmoid function is infeasible. To address this challenge, a polynomial approximation \({\sigma }_{r}\left(z\right)\) is employed to approximate the sigmoid function:

where \(r\) represents the polynomial’s order, and \(z\) is the input to the Sigmoid function. The polynomial approximation allows the use of the Sigmoid function within FHE constraints. As such, the proposed framework can support secure computation while preserving the essential properties of the original function.

Ensemble learning in smart healthcare systems

FHE provides a high level of data privacy protection by enabling computations directly on encrypted data. However, this privacy protection comes with a significant computational burden due to the intensive mathematical operations involved. To address this trade-off, a distributed ensemble learning structure is designed in the proposed framework to both reduce computation time and enhance model performance.

Ensemble learning combines multiple sub-models to create a more robust machine learning model. Specifically, bootstrap aggregating (bagging) is employed to enhance model performance by integrating outcomes from several sub-models. In bagging, multiple versions of models are trained on different bootstrap samples of training data, and their outcomes are integrated to produce a final result. This distributed learning structure reduces the computational load for each sub-model by distributing the training process across multiple nodes. By leveraging distributed computing resources, the overall computation time can be reduced, as each model is trained in parallel. Additionally, using various training sets improves model accuracy and robustness by reducing variance and minimizing overfitting.

As shown in Fig. 11, we propose a distributed ensemble learning framework for smart healthcare systems. In this framework, \(\text{K}\) departments collaborate, and the consensus model comprises \(\text{S}\) sub-models. Each department’s dataset is divided into \(\text{S}\) subsets, corresponding to the number of models in the consensus framework. Each subset of data trains a specific sub-model; for instance, subset \(s\) from department \(k\) is used to train sub-model \(s\). As a result, this approach allows each sub-model to process only \(1/s\) of the total data, distributing the computational load across multiple nodes. Once all sub-models are trained, their outputs are combined using a majority voting mechanism to determine the final prediction.

Each logistic regression sub-model computes the probability of the positive class using the sigmoid function:

where \({{\varvec{\upbeta}}}_{s}\) denotes the parameters vector for sub-model \(s\). Each sub-model assigns a binary label based on a threshold, which is typically defined as 0.5:

The final ensemble prediction \({\widehat{y}}_{ens}\) is determined via majority voting as

Alternatively, this can be written using the indicator function as

This approach allows healthcare system to reduce computational overhead by parallelizing the training process across nodes while maintaining high prediction accuracy.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the Multiparameter Intelligent Monitoring in Intensive Care (MIMIC) II Database, https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e31820a92c6.

Code availability

The code for this study will be available upon request to the corresponding author.

References

Reinsel, D. How you contribute to today’s growing datasphere and its enterprise impact. https://blogs.idc.com/2019/11/04/how-you-contribute-to-todays-growing-datasphere-and-its-enterprise-impact/ (2019).

Chen, C.-B., Wang, Y., Fu, X. & Yang, H. Recurrence network analysis of histopathological images for the detection of invasive ductal carcinoma in breast cancer. IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinform 20, 3234–3244 (2023).

Alomran, O., Qiu, R. & Yang, H. Hierarchical clinical decision support for breast cancer care empowered with bayesian networks. Digital Transformation and Society 2, 163–178 (2023).

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Healthcare data breach statistics. https://www.hipaajournal.com/healthcare-data-breach-statistics/ (2024).

I.B.M. Corporation. Cost of a data breach report 2023. https://www.ibm.com/account/reg/us-en/signup?formid=urx-52913 (2023).

Morse, A. Investigation: WannaCry Cyber Attack and the NHS. (2017).

Voigt, P. & von dem Bussche, A. The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-57959-7.

Goldstein, M. M. & Pewen, W. F. The Hipaa Omnibus Rule: Implications for Public Health Policy and Practice. Public Health Reports® 128, 554–558 (2013).

ISO/IEC 29100. Information technology—security techniques—privacy framework. International Organization for Standardization Std (2024).

Dimopoulou, S. et al. Mobile Anonymization and Pseudonymization of Structured Health Data for Research. in 2022 Seventh International Conference On Mobile And Secure Services (MobiSecServ) 1–6 (IEEE, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1109/MobiSecServ50855.2022.9727206.

Krall, A., Finke, D. & Yang, H. Gradient mechanism to preserve differential privacy and deter against model inversion attacks in healthcare analytics. in 2020 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC) 5714–5717. https://doi.org/10.1109/EMBC44109.2020.9176834 (IEEE, 2020).

Chen, Y. & Yang, H. Heterogeneous postsurgical data analytics for predictive modeling of mortality risks in intensive care units. in 2014 36th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society 4310–4314. https://doi.org/10.1109/EMBC.2014.6944578 (IEEE, 2014).

Saeed, M. et al. Multiparameter intelligent monitoring in intensive care II: A public-access intensive care unit Database*. Crit Care Med 39, 952–960 (2011).

Krall, A., Finke, D. & Yang, H. Mosaic privacy-preserving mechanisms for healthcare Analytics. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform 25, 2184–2192 (2021).

Chen, Y., Leonelli, F. & Yang, H. Heterogeneous sensing and predictive modeling of postoperative outcomes. Healthcare Analytics: From Data to Knowledge to Healthcare Improvement 463 (2016).

Han, H., Wang, W.-Y. & Mao, B.-H. Borderline-SMOTE: A new over-sampling method in imbalanced data sets learning. in 878–887 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/11538059_91.

Tomek I. Two modifications of CNN. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern SMC-6, 769–772 (1976).

Rivest, R. L., Adleman, L. & Dertouzos, M. L. On data banks and privacy homomorphisms. Foundations of Secure Comput. 4, 169–180 (1978).

Gentry, C. Fully homomorphic encryption using ideal lattices. Proceedings of the forty-first annual ACM symposium on Theory of computing 169–178 https://doi.org/10.1145/1536414.1536440.

Brakerski, Z., Gentry, C. & Vaikuntanathan, V. (Leveled) Fully homomorphic encryption without bootstrapping. ACM Trans. Computat. Theory 6, 1–36 (2014).

Fan, J. & Vercauteren, F. Somewhat practical fully homomorphic encryption. Cryptology ePrint Archive (2012).

Cheon, J. H., Kim, A., Kim, M. & Song, Y. Homomorphic encryption for arithmetic of approximate numbers. in 409–437 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-70694-8_15.

Xu, W. et al. Toward practical privacy-preserving linear regression. Inf Sci (N Y) 596, 119–136 (2022).

Xia, Z., Yin, D., Gu, K. & Li, X. Privacy-preserving electricity data classification scheme based on CNN model with fully homomorphism. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Comput. 8, 652–669 (2023).

Zhang, P. et al. Privacy-preserving and outsourced multi-party k-means clustering based on multi-key fully homomorphic encryption. IEEE Trans Dependable Secure Comput https://doi.org/10.1109/TDSC.2022.3181667 (2022).

Kuo, T. & Yang, H. Federated learning on distributed and encrypted data for smart manufacturing. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. Eng. 24 (2024).

Lee, H., Finke, D. & Yang, H. Privacy-preserving neural networks for smart manufacturing. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. Eng. 24 (2024).

Lyubashevsky, V., Peikert, C. & Regev, O. On Ideal Lattices and Learning with Errors over Rings. In 1–23 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-13190-5_1.

Cheon, J. H., Han, K., Kim, A., Kim, M. & Song, Y. A Full RNS Variant of Approximate Homomorphic Encryption. In 347–368 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-10970-7_16.

Acknowledgements

The study is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (Project No. NIH R01 HL172292) and Penn State Center for Health Organization Transformation (Corresponding author: Hui Yang).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.K. designed the methodology of the study, performed data analysis, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. H.Y. conceived and led the project, contributed to the experimental design, and was a contributor to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kuo, T., Yang, H. Multi-layer encrypted learning for distributed healthcare analytics. Sci Rep 15, 39442 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23140-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23140-6