Abstract

Microarray technology has revolutionized cancer genomics by enabling the simultaneous analysis of thousands of gene expressions, providing critical insights into gene regulation and disease mechanisms. However, the inherent challenges of high-dimensionality, noise, and sparsity in microarray data demand robust analytical approaches. Image processing techniques further enhance this analysis by extracting meaningful patterns from histological and microarray-derived visual data, aiding in biomarker discovery and classification. This study presents a novel framework leveraging deep neural networks for gene selection and cancer classification using microarray data, addressing the challenges of high dimensionality, noise, and sparsity. The proposed Gene-Optimized Neural Framework (GONF) integrates the Minimum Redundancy Maximum Relevance (mRMR) gene selection method with a deep Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) for effective feature selection and classification. By optimizing hyperparameters and employing advanced preprocessing techniques, the framework enhances computational efficiency and accuracy. Experiments were conducted on TCGA and AHBA datasets, utilizing metrics such as accuracy, precision and recall for evaluation. The GONF outperformed other methods, achieving a classification accuracy of 97% on the TCGA dataset and 95% on the AHBA dataset. The framework demonstrated significant reductions in false positive and false negative rates, improving cancer subtype predictions and providing biologically interpretable results. The findings highlight GONF’s robustness and adaptability, paving the way for its application in other genomic studies and clinical settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microarray technology has revolutionized the field of genomics, enabling the high-throughput measurement of gene expression across thousands of genes simultaneously1,2. This advancement has made microarray data an invaluable resource in cancer research, offering insights into gene regulation, biological pathways, and disease mechanisms3. A critical application of this technology is cancer classification, where accurately distinguishing between cancer subtypes is essential for diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment planning. Despite its potential, the analysis of microarray data presents significant challenges due to its high dimensionality, sparsity4, and noise, which often obscure meaningful biological patterns and complicate the extraction of relevant information. Gene selection plays a crucial role in addressing these challenges. By identifying the most informative genes, gene selection reduces the dimensionality of the data, improving classification performance and enhancing the interpretability of the results4,5. However, traditional gene selection methods, which typically rely on statistical tests or basic feature selection algorithms, struggle to capture the complex, nonlinear relationships that exist between genes6. These limitations necessitate the development of more sophisticated approaches to gene selection and classification.

Deep neural networks (DNNs) have emerged as powerful tools for addressing these challenges. Their ability to model complex, nonlinear interactions and automatically extract hierarchical features makes them particularly well-suited for analyzing high-dimensional genomic data. DNNs can be used to enhance gene selection by learning which genes are most relevant to the classification task, without the need for manual intervention or predefined assumptions about gene interactions7. Additionally, DNNs’ success in image processing tasks, where they have demonstrated an ability to learn spatial hierarchies of features, suggests that similar techniques can be applied to gene expression data to uncover hidden patterns. Integrating DNNs with gene selection techniques offers a promising approach to improving cancer classification from microarray data. This combination allows for the simultaneous reduction of dimensionality and the identification of biologically significant genes, thereby addressing issues of noise, redundancy, and computational complexity. By leveraging both the power of deep learning and advanced feature selection, this research aims to provide a more accurate, interpretable, and biologically meaningful analysis of cancer data8.

The motivation for this study arises from the need to develop more effective cancer classification models that balance dimensionality reduction, interpretability, and classification accuracy. With the growing availability of large-scale genomic data, there is an urgent need for methods that can extract meaningful insights from these high-dimensional datasets while managing inherent noise and redundancy. By combining DNNs with robust gene selection techniques, this research seeks to bridge the gap between cutting-edge computational methods and their practical applications in cancer genomics. This study, makes a number of new contributions to the field of cancer classification using microarray data:

-

Integrated mRMR-CNN Pipeline: GONF is the only program that combines the mRMR gene selection method with a deep CNN in a single framework. GONF improves both accuracy and interpretability by using a low-redundancy, high-relevance gene subset that directly informs the CNN’s feature extraction process. This is better than traditional methods that treat feature selection and classification as separate steps.

-

Image Processing for Genomic Data: GONF pioneers the integration of advanced image processing techniques, such as the Hough Transform and Watershed segmentation, to preprocess microarray-derived visual data and histopathological images. This preprocessing improves the quality of the input features by lowering noise and making it easier for the CNN to find biologically relevant patterns. This is a new method that hasn’t been used much in previous gene selection studies.

-

Optimized CNN Architecture for Genomic Data: The customized CNN architecture has six convolutional layers, dropout regularization, and max pooling. It is made to handle the high dimensionality and sparsity of microarray data. When combined with Random Search hyperparameter optimization, this makes GONF stand out from other hybrid deep learning models because it ensures strong performance and computational efficiency.

These contributions together make GONF a strong and new way to classify cancer, and it could also be useful in other areas of genomic research and clinical diagnostics. The remainder of this article is structured as follows: section “Related works” reviews the role of microarray technology, gene selection, and the application of deep learning in cancer research. Section “Dataset” presents the proposed methodology, detailing the integration of DNNs with gene selection techniques. Section “Proposed method” reports experimental results, comparing the performance of the proposed approach with existing methods. Finally, section “Evaluation” discusses the implications, potential applications, and future research directions.

Related works

Recent years have witnessed significant advances in the application of neural networks for gene selection and cancer classification using microarray data. Microarray technology generates extensive gene expression profiles, making deep learning models essential for efficient feature selection, improving classification accuracy, and addressing challenges related to data sparsity and high dimensionality. The authors in9 introduced a DNN methodology to enhance gene selection for cancer classification. This approach aimed to improve classification accuracy by reducing the complexity of microarray data, integrating gene selection with a DNN for enhanced predictive results. The findings showed substantial improvements in predictive accuracy compared to conventional methods, demonstrating the effectiveness of DNNs in handling high-dimensional cancer data. Low-light image enhancement methods based on physical models of fogging have played an important role in improving the quality of input data for feature extraction10. The focus was on minimizing noise in microarray samples and identifying the most relevant genes for classification. This model outperformed traditional classifiers, highlighting the ability of DNNs to autonomously discern essential properties in high-dimensional cancer data and showing their proficiency in multi-class cancer classification. In11, the authors addressed the problem of class imbalance in cancer classification by incorporating a weighted loss function within a deep learning framework. This strategy significantly improved the accuracy of identifying minority cancer types, emphasizing deep learning’s capacity to manage complex real-world datasets. Multiexponential representation learning in molecular property prediction has been introduced as a powerful approach for extracting complex features from genomic data12. This hybrid model enhanced computational efficiency and classification precision by selecting a smaller set of genes while maintaining high predictive performance, validating that hybrid DNNs could improve both efficiency and accuracy in cancer classification.

Another study by the authors in13 explored the use of deep reinforcement learning (DRL) to improve gene selection for cancer categorization. By progressively identifying the most important genes based on their impact on classification accuracy, the DRL-based model reduced the number of genes needed for precise classification, while maintaining high performance. This approach highlighted the potential of reinforcement learning in enhancing gene selection for cancer classification. The authors in14 proposed a DNN model for predicting cancer outcomes using gene expression data. The model incorporated a feature selection phase, ensuring that only the most significant genes were used for prediction. This model surpassed conventional classification algorithms, offering a more efficient and accurate method for predicting cancer outcomes. A study by the authors in15 proposed a deep learning system for tumor classification, combining unsupervised training for feature extraction with supervised training for cancer classification. This dual-phase methodology enhanced both gene selection and classification accuracy, with the unsupervised training helping to uncover complex gene interactions, improving classification results. Analysis of microarray data in a recent study has revealed common pathways in gastrointestinal and cardiac diseases, confirming the importance of using microarray data in discovering disease mechanisms16. This method significantly reduced the number of genes required, enhancing the efficiency of the classification process while maintaining high accuracy. The study demonstrated that autoencoder-based DNN models are effective in managing large-scale gene expression datasets. The authors in17 integrated evolutionary methods with DNNs for feature selection and cancer classification. The emphasis was on identifying a minimal set of genes that provided optimal classification performance. This hybrid approach achieved substantial precision, demonstrating the effectiveness of optimization methods in enhancing cancer classification. The development of video resolution enhancement methods using complex CNNs has shown that spatiotemporal convolutional operations can enhance the quality of image reconstruction. This can be effective in improving the quality of microarray-derived images18. The model adapted during training to focus on the most relevant genes, achieving superior classification accuracy and computational efficiency compared to traditional classifiers. This flexible feature selection process minimized overfitting and enhanced the generalizability of the model. A study by the authors in19 employed both unsupervised and supervised learning techniques, using autoencoders for feature extraction and DNNs for classification. This approach effectively identified pertinent gene sets and categorized cancer types with high precision, even with limited training data. The authors in20 proposed a hybrid model combining a deep CNN with a support vector machine (SVM) for gene selection in cancer classification. The model’s unique architecture facilitated efficient feature extraction from microarray data, resulting in enhanced classification accuracy. The SIR-3DCNN framework has provided good performance by combining time series and spatial features for early detection of lung cancer, which is in line with our goal of using complex CNNs on multidimensional data21. By representing gene interactions as a graph, GTCGA could capture complex relationships among genes, outperforming conventional methods in both precision and interpretability.

This survey indicates that current approaches include several shortcomings. Numerous conventional models are susceptible to overfitting, especially when processing high-dimensional data, hence diminishing their performance on novel, unexplored data. Moreover, models such as KNN are deficient in sophisticated feature selection methods, leading to suboptimal identification of essential predictors. Conventional techniques may lack robustness, constraining the models’ capacity to reliably discern the most significant predictors. Moreover, although deep learning methodologies possess potential, their amalgamation with optimal feature selection for gene selection and classification of cancer remains inadequately investigated. Resolving these difficulties necessitates the creation of models that harmonize precision with computing efficiency and possess the robustness to generalize across many situations. The proposed method GONF, overcomes many constraints of conventional approaches by exhibiting markedly superior accuracy. This enhancement is attained by refined selection of features and DNN optimization methods. Furthermore, the amalgamation of mRMR with deep learning efficiently diminishes data dimensionality, enabling the model to concentrate on essential variables and mitigate overfitting. The model experiences accelerated convergence owing to a random approach for hyperparameter optimization, hence lowering training duration. The architecture facilitates scaling via transfer learning, enhancing its adaptability to various illnesses and expanding its use in predictive analytics. The algorithm’s efficacy and precision render it suitable for practical application, facilitating its incorporation into healthcare environments.

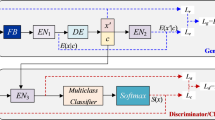

The use of neural networks for gene selection and cancer classification has advanced significantly in recent years. Hybrid approaches such as CNN + wrapper FS22,23, mRMR + DNN24,25, CSSMO-based deep learning (CSSMO-DL)26, and Multi-classification GAN with Feature Bundling (MGAN-FB)27 have shown promise. Nevertheless, these techniques have drawbacks, such as the potential for overfitting, the need for computationally intensive feature selection, and the restricted ability to integrate multi-modal data, like histopathological images or visual data derived from microarrays. For example, CNN + wrapper FS models mainly rely on numerical data and lack robust image preprocessing, whereas mRMR + DNN approaches frequently handle feature selection and classification in a sequential manner. Similarly, MGAN-FB concentrates on numerical data with feature bundling, omitting CNN-specific optimization, and CSSMO-DL uses metaheuristic feature selection but excludes visual data.

The suggested approach (GONF) fills these gaps by combining mRMR gene selection with a customized six-layer CNN and sophisticated image processing methods like Watershed segmentation and Hough Transform to take advantage of both visual data (microarray-derived intensity maps and histopathological images) and numerical gene expression. Table 1 compares GONF to these new hybrid methods, emphasizing how its multi-modal data integration and unified pipeline improve accuracy and biological interpretability. This comparison demonstrates how GONF is unique in overcoming the drawbacks of current approaches, opening the door for its thorough methodology in section “Proposed method”.

Dataset

We evaluate the proposed method with two different standard microarray datasets The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Allen Human Brain Atlas (AHBA). Figures 1 and 2 shows an example of the images used in TCGA and AHBA datasets.

TCGA dataset

TCGA integrates microarray-based gene expression data with high-resolution histopathological images to support cancer research. The microarray data provides detailed gene expression profiles across thousands of genes for various cancer types, allowing researchers to investigate transcriptional changes, identify biomarkers, and understand tumor biology. These datasets are complemented by clinical metadata, such as tumor stage and patient outcomes, enabling a multi-dimensional analysis of cancer progression and response to treatments. Alongside the microarray data, TCGA offers high-resolution histopathological Whole Slide Images (WSIs) of tumor tissues, typically stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E). These images allow for the examination of tissue architecture and cellular morphology, which can be correlated with gene expression patterns derived from microarrays. This integration of transcriptomic and imaging data supports innovative research, such as linking molecular signatures to histological features or predicting genomic alterations from image data. The TCGA datasets are accessible through platforms like the GDC Data Portal and the Cancer Digital Slide Archive, making it a vital resource for advancing cancer diagnostics and therapeutics. The GCCNet model using gated cross-correlation has shown high accuracy in multi-view classification. This idea can also be inspiring in multi-view analysis of gene expression data28.

AHBA dataset

The AHBA combines microarray-based gene expression data with high-resolution brain imaging to map the molecular architecture of the human brain. Microarray data includes the expression profiles of over 20,000 genes sampled from thousands of anatomical sites across six human donor brains, offering a detailed view of gene activity in specific brain regions. This allows researchers to explore gene regulation, identify spatial patterns of gene expression, and study the molecular basis of brain functions and disorders. The dataset al.so includes metadata on the sampled regions, enabling precise localization of gene activity within the brain’s anatomical structure. In addition to microarray data, the AHBA features structural and functional imaging, such as MRI scans and histological sections. These high-resolution images provide a visual context for the gene expression data, allowing for the integration of molecular profiles with brain morphology. This combination supports multi-modal analyses, such as linking gene expression patterns to brain structure, function, or disease states. Accessible through the Allen Institute’s portal, the dataset is a powerful resource for researchers studying the intersection of genomics, neuroscience, and imaging, enabling a deeper understanding of the human brain’s complexity29.

Proposed method

Within the cancer classification model, the three most important components are feature selection, data preparation, and classification. After the data preprocessing step, we do outlier processing and standardization on the dataset to make sure all the data are properly formed. To identify important features, a gene selection procedure based on the mRMR mechanism is used. We create a 4:2 training and test set from the chosen subset, with the former being fed into our GONF. To be more precise, our deep neural network builds the optimal initial weights to achieve a better result. Furthermore, the test samples are used to gauge the model’s efficacy. Figure 3 clearly illustrates the flow diagram of the proposed method-GONF.

Pre-processing

The purpose of this section is to provide in-depth information regarding the preprocessing that is utilized in the GONF method to ensure accuracy. Preprocessing is crucial for the effectiveness of the GONF method, as it directly impacts the reliability of the results obtained. Therefore, various techniques are employed to normalize data and ensure that the input is of superior quality prior to analysis. The image processing methods used in this study are applied directly to actual histopathological and microarray images. These techniques play specific, useful roles in our data pipeline rather than being employed as metaphorical or analogous references. Our framework makes use of datasets like TCGA and AHBA, which offer high-resolution visual data in addition to numerical gene expression profiles. In particular, AHBA contains anatomical and histological scans of brain tissue, whereas TCGA provides H&E-stained Whole Slide Images (WSIs). These image modalities are processed as part of the computational pipeline and are essential to the analysis. The image data undergoes a number of preprocessing steps to improve feature extraction and guarantee consistency. In order to ensure correct alignment before CNN input, the Hough Transform is used to identify and correct image skew in scanned microarray and histopathological sections. The accuracy of spatial feature localization is increased by detecting microarray grid patterns and suppressing noise through the use of autocorrelation techniques in conjunction with average brightness analysis. Furthermore, watershed segmentation allows for more accurate feature extraction by defining areas of interest within overlapping or intricate visual structures, such as gene spots or cell clusters. Gene expression data and the resulting preprocessed images are converted into structured representations and fed into the CNN architecture. This design improves classification performance by allowing joint learning from gene expression profiles and image-derived features.

Normalization

Using z-score normalization, the TCGA and AHBA microarray datasets were preprocessed to standardize gene expression values. This ensured that each gene had a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 for every sample. For a gene expression value \({x_{ij}},\) \(gene~\left( i \right)\) and sample \(\left( j \right)\), the z-score was computed as follows:

where \({{\text{\varvec{\upsigma}}}_i}\) is the standard deviation and\(~{{\text{\varvec{\upmu}}}_i}\) is the gene \(i~\)mean expression. To lessen the impact of extreme values, robust outlier clipping was used prior to normalization, capping expression values at the 1st and 99th percentiles. Pixel intensities were normalized to the range [0, 1] for histopathological and microarray-derived images using min-max normalization:

the original pixel intensity is represented by \(I\left( {x,y} \right)\) and the image’s minimum and maximum intensities are represented by \({I_{min}}\) and \({I_{max}}~\)or the CNN, images were resized to a uniform input size of \(128~ \times 128~ \times 1\).

Image preprocessing

To ensure correct alignment, skew was detected and corrected using the Hough Transform (HT) on microarray-derived visual data and histopathological images. The HT is a mathematical technique used in image processing for detecting geometric shapes, such as lines, in digital images. It works by transforming points in the image space into a parameter space, where patterns corresponding to the desired shapes can be identified. This transformation is particularly effective for detecting lines, as it simplifies the problem into finding intersections or peaks in a two-dimensional parameter space. In the Cartesian coordinate system, a line is expressed as Eq. (1).

where m is the slope, and c is the y-intercept. However, this representation is unsuitable for computational purposes, especially for vertical lines where the slope becomes undefined. Instead, the Hough Transform uses the polar form of a line, given by Eq. (2).

Here, ρ is the perpendicular distance from the origin to the line, and θ is the angle between the x-axis and the normal to the line. The coordinates (x, y) are points on the line. This representation ensures uniform handling of lines, including vertical ones. Also to detect lines, edge points in the image are first identified using techniques like the Canny edge detector. Each edge point (x, y) is mapped into the parameter space using the Eq. (3).

This results in a sinusoidal curve in the parameter space for each edge point, representing all possible lines passing through that point. This process is repeated for all edge points, generating multiple curves in the parameter space.

To identify the lines, the Hough Transform uses an accumulator array, which discretizes the parameter space into bins. The value of each bin is incremented whenever an edge point contributes to the corresponding (ρ,θ) pair. This can be represented as Eq. (4).

Here, δ is the Dirac delta function, ensuring that only the relevant bins are incremented.

Peaks in the accumulator array correspond to the most prominent lines in the image. Each peak provides the parameters (ρ,θ) of a detected line. These parameters can be used to reconstruct the line in the image space using the Eq. (5).

The Hough Transform is highly robust to noise and can detect lines even when they are partially obscured. It is commonly used for tasks such as skew detection in images, where the dominant angles of detected lines help determine the skew angle of the image. By analyzing these angles, the skew can be corrected by rotating the image by the negative of the computed angle. This makes the Hough Transform a versatile tool in applications requiring geometric analysis and alignment.

Calculate average brightness values

In a microarray image, calculating the average brightness values along horizontal or vertical directions involves computing the mean projection of pixel intensities across one axis. For the horizontal brightness profile, the average brightness for each row y in an image with dimensions x×y is calculated using the Eq. (6).

Here, x is the total number of pixels in the horizontal direction, y is the index of the row, and I(i, y) represent the intensity value of the pixel at column ii in row y. This equation computes the average brightness of all pixels in a specific row by summing their intensity values and dividing by the total number of pixels in that row. Similarly, for the vertical brightness profile, the average brightness for each column x is determined using the Eq. (7).

Here, y is the total number of pixels in the vertical direction, x is the index of the column, and \({\text{I}}\left( {{\text{x}},{\text{j}}} \right)\) represent the intensity value of the pixel at row j in column x. This equation calculates the average brightness of all pixels in a specific column by summing their intensity values and dividing by the total number of pixels in that column.

Figure 4 shows the process of identifying locations in a microarray block. Figure 4a presents the vertical histogram of the microarray block based on the mean value of the x pixels, which represents the signal intensity distribution in the vertical direction. This histogram contains noise that can affect the data analysis. In Fig. 4b, the autocorrelation function is applied to the histogram, which shows the repetitive pattern present in the data. Fast image dehazing methods based on linear transformations have improved the sharpness and detail of images in vision systems. Applying such techniques in the preprocessing of histopathological images can increase the accuracy of cancer classification30. The peaks of the autocorrelation function provide important information about the periodic position of the elements in the block.

In Fig. 4c, the noise present in the histogram has been removed using noise removal techniques and a cleaner pattern of signal intensities can be seen. Finally, in Fig. 4d, grid lines are drawn based on the identified locations in the data. These lines represent the designated locations for the microarray elements, which is done to facilitate more detailed analysis and data alignment. This process plays an important role in increasing the accuracy and efficiency of microarray data analysis.

Gene expression

The gene selection procedure is markedly inefficient for accurate classification, but the mRMR method may significantly enhance classification accuracy31. In a high-dimensional microarray, the presence of hundreds of genes renders the direct application of a technique problematic. Furthermore, accurately training a classifier poses considerable difficulties. Alternative solutions must be employed to address this situation successfully. Thus, mRMR is employed initially to remove noisy and redundant genes. Cross-modal causal learning in radiology report generation has shown that merging image and text data can improve clinical analysis32. This approach is similar to our goal of merging genomic and image data to improve cancer classification. This technique may be utilized for both continuous and discrete datasets to evaluate the significance and redundancy of variables and to pinpoint the most advantageous ones. This research offers a comparative examination of mRMR and the maximum relevance approach (MaxRel), employing several machine learning classifiers across separate microarray datasets. The experimental findings indicate that mRMR is a highly effective method for enhancing feature selection efficacy. The features selected by mRMR demonstrate enhanced predictive potential and produce more precise classification outcomes than those indicated by MaxRel. The integration of convolution and transformer architectures in image feature extraction significantly improves the performance of medical vision models33. Experimental results from comparative cancer microarray datasets demonstrate that the mRMR filter approach exhibits greater efficacy when employed alongside SVM-RFE. It has been shown that mRMR can be effectively used with other feature selection techniques, including wrappers. Hybrid models based on histopathological images and gene mutations have shown accurate performance in predicting survival of patients with colorectal cancer. These results are in line with our strategy of integrating imaging and genomic data34. This may be implemented to identify a highly condensed subset from prospective characteristics at a lower expense. Furthermore, the authors in35 introduced a novel gene selection method that combines an mRMR filter methodology with a genetic wrapper strategy. The findings of this investigation demonstrated that the mRMRGA method was superior to both mRMR filtering and GA wrapper through all datasets. Concurrently, an equivalent number of chosen genes from this experimental outcome demonstrated that the gene set obtained using mRMRGA selection was more representative of the designated class. We will utilize the mRMR gene selection method to identify predictive genes that have low redundancy with other genes in the microarray dataset and maximal relevance to certain cancer classifications. The mRMR technique utilized two mutually beneficial data procedures: one to evaluate the significance between cancer types and individual genes, and the other to examine the redundancy across gene pairs. Figure 5 illustrates the mRMR dataset, which consists of the indices of the chosen genes arranged sequentially. The initial row indicates the most relevant and the least extraneous genes.

The significance of a selected collection of genes, SG, can be articulated as Eq. (8).

W(Gx, F) denotes the value of the shared knowledge between a gene Gx from the SG class and the malignant cell class E = {e1, e2}, where e1 represents the normal class and e2 signifies the malignancy class. Genes can be selected to exhibit a high degree of reliability, often referred to as redundancy, among themselves. The redundant RG of a selected set of genes SG is as Eq. (9).

\(W\left( {{G_x},{G_y}} \right)\) represents mutual information across genes x and y, indicating the extent of their interdependence. The primary objective of employing the mRMR gene selection approach is to discover a specific subset of genes from SG, denoted as {xi}, that exhibit the highest dependence on the target class or the least dependence on the selected gene subset SG. Authors in20 propose utilizing the composite objective to identify equitable solutions for all parties involved. This criterion employs the maximal relevance criterion and the minimal redundancy criterion as Eq. (10).

Through this strategy the microarray datasets, which at first had about 20,000 genes, were made less dimensional. mRMR chose a subset of 100 genes for the TCGA dataset with 500 samples, producing a feature matrix of size \(\left( {500 \times 100} \right)\). 80 genes were chosen for the AHBA dataset with 300 samples, resulting in a feature matrix of size \(\left( {300 \times 80} \right)\). In order to choose genes with high predictive power and low redundancy, the mRMR process computed mutual information for relevance (Eq. 8) and redundancy (Eq. 9). The objective function (Eq. 10) was then optimized. A validation set was used to adjust the number of chosen genes to optimize classification accuracy while preserving computational efficiency.

Segmentation

The backdrop in microarray images pertains to chemical residues present on the chip during a clinical study34. Inhomogeneous backgrounds provide a significant challenge in microarray imaging. This work uses the watershed method to address the problem. This is implemented to integrate the picture with the backdrop and texture. Recent proteomic studies have shown that chromatin rearrangements can be an effective therapeutic target in neuroblastoma36. Incorporating this level of omics information could help improve the gene selection process in cancer classification models. Watershed segmentation is a powerful image processing technique used to separate and segment regions within an image based on the concept of topographic representation. In this approach, the intensity values of an image are treated as a surface, where the pixel values represent elevation. Bright regions are considered peaks or ridges, while dark regions are interpreted as valleys. The algorithm works by simulating the flooding of water into these valleys. As water fills the basins, barriers are constructed to prevent the merging of water from different basins, effectively segmenting the image into distinct regions. The representation of the watershed transformation is shown in Fig. 6.

Representation of the watershed transformation. (a) An image containing three items that cannot be delineated by a basic threshold. (b) Segmentation of foreground and background. (c) Inverse of image. (d) Intensity line profile along the illustrated line, demonstrating the filling of the basins to the level where the yellow and blue regions converge, resulting in the formation of a first watershed. (e) Watershed transformation. (f) masked image by using (b).

For formulating the transmission, it is assumed that I(x, y) denote the intensity of the pixel at coordinates (x, y). The goal of watershed segmentation is to identify catchment basins and ridge lines. A catchment basin is a region where all pixel’s flow towards a common local minimum under the influence of the gradient of the image. The gradient magnitude of the image, G(x, y) is used to detect these basins and is given by Eq. (11).

Here, \(\frac{{\partial I}}{{\partial x}}~\)and \(\frac{{\partial I}}{{\partial y}}\) are the partial derivatives of the image intensity in the horizontal and vertical directions, respectively. The gradient magnitude highlights the edges in the image, where transitions in intensity occur.

Flooding starts at the local minima of G(x, y) and water gradually fills the catchment basins. To prevent the merging of water from different basins, a boundary or “dam” is built at points where the water from adjacent basins meets. These boundaries correspond to the watershed lines. The segmentation output can be represented as a labeled matrix S(x, y) where each label identifies a distinct region. As shown in Eq. (12).:

where k is a unique identifier for each segmented region.

Watershed segmentation is especially effective in separating touching or overlapping objects, such as cells in microscopy images. However, it is sensitive to noise and over-segmentation, as small intensity variations can create additional local minima. To address this, preprocessing techniques like smoothing or using markers (marker-based watershed) are often applied. Marker-based watershed segmentation uses predefined markers to guide the flooding process, with markers being placed at locations of known objects or regions of interest. Genomic and epigenomic analyses have shown that miRNAs play a key role in tumor heterogeneity and immune evasion in brain tumors37. This reduces sensitivity to noise and improves segmentation accuracy. The mathematical formulation for marker-based segmentation incorporates a modified gradient, Gm(x, y), which enforces the flooding constraints defined by the markers, ensuring that regions align with the markers’ locations.

Classification

In this study, we leverage a deep CNN for the classification phase, specifically designed to handle the complexities of microarray data in cancer detection. CNNs are a type of DNN commonly used for their exceptional ability to automatically extract hierarchical features from raw data, making them particularly suitable for complex, high-dimensional datasets like those found in genomics. Typically, a DNN is structured with a feedforward network, where the backpropagation method plays a crucial role in training the model by adjusting weights to minimize errors. The TRAPT framework, utilizing deep learning and epigenomic data, has accurately predicted key transcriptional regulators. Such models offer new avenues for prioritizing genes in cancer classification38. Over the years, deep neural networks, including CNNs, have been successfully applied across various domains such as voice recognition, image analysis, and cancer detection, demonstrating their robustness and versatility in extracting relevant patterns from complex data. What sets CNNs apart is their ability to learn spatial hierarchies of features, which is particularly useful for microarray data classification. Unlike traditional machine learning methods, CNNs can automatically discover intricate relationships between genes in microarray data, making them ideal for handling high-dimensional and sparse datasets. CNNs excel in capturing local dependencies between genes and identifying relevant features for cancer subtype classification, all while using fewer parameters compared to other deep learning models. This characteristic enables CNNs to work efficiently with structured genomic data, offering a promising solution for gene selection and cancer detection tasks. Comprehensive pan-cancer analyses have identified the NTN1 gene as an important factor in the immune and prognostic influence of cancers. These findings highlight the importance of focusing on key genes in selecting effective traits39.

The CNN architecture employed in this study consists of six convolutional layers, each followed by a Max Pooling layer to reduce dimensionality and retain essential features. This structure helps the model learn progressively more abstract representations of the data, essential for accurately distinguishing cancer subtypes. To prevent overfitting and improve generalization, a “dropout” layer is incorporated after the pooling layers, randomly deactivating certain neurons during training. Finally, a smoothing layer is applied to generate the final feature vector, which serves as the input for the classification phase. This architecture allows for the effective classification of cancer types based on microarray data, with the flexibility to adapt to various genomic datasets. Figure 7 illustrates the CNN design, and Table 2 presents the detailed hyperparameters used in the proposed model. By utilizing deep CNNs for microarray classification, this study aims to enhance both the accuracy and interpretability of cancer detection models, offering a powerful tool for identifying gene patterns that are crucial for understanding cancer biology.

This work addresses the prediction of cancer as a binary classification problem. We assess the prediction accuracy of the model ability using Binary Cross (BIC) as a loss function. Binary classification problems typically employ BIC. The subsequent Eq. (13) is employed to calculate the loss utilizing BIC.

where f(n) is the probability that n, is the binary label. Minimizing loss enhances the likelihood of b(x) for samples labeled as 1, hence enabling the use of BIC as an indicator of classification quality. Conversely, the probability of the sample possessing zero labels is diminishing. Minimizing loss is a process that can significantly enhance the model’s accuracy. The deep neural network employs the Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) as activation function, while utilizing the sigmoid activation function in the output layer. This is performed to guarantee that the output is confined to the interval [0, 1], which is essential for compatibility with the BIC loss function. Moreover, the output is more readily modifiable when employing the sigmoid function as opposed to ReLU. Equations (14) and (15) illustrate the sigmoid and ReLU functions, which are:

The pooling layer of a CNN attains invariance and decreases complexity by eliminating duplicate information by downsampling. The primary approaches employed for pooling are max and average pooling. Average pooling calculates the mean value of the designated area and utilizes it as the pooling result, whereas max pooling determines the greatest value within the zone and employs it as the pooling output. This study utilizes the maximal pooling technique because of its superior capacity to preserve essential information relative to average pooling. The max pooling method is illustrated in Eq. (16):

Where M is the maximum pooling, l is the element (j) of the pooling area a, and \(\:{O}_{r}\) is the output results of the pooling. This method facilitates the retention of essential characteristics while diminishing noise and extraneous information. Following the application of the convolutional layer to the pre-processed input, this procedure is reiterated a certain number of times based on the network type. Subsequent of these layers, one or more fully linked layers are employed to do precise mappings of the extracted characteristics. A completely connected layer is comparable to a convolutional layer; however, it is characterized by a complete link to its preceding layer, unlike the sparse connections found in convolutional layers. This is comparable to the process of establishing connections in conventional neural networks. Mendelian randomization studies have confirmed the causal relationship between genetic markers such as HbA1c and various diseases40. The last layer produces a 1-dimensional vector, with the number of components in this vector corresponding to the number of classification categories. The primary role of this type of layer is to do categorization. In this context, the output of the neural network is employed to compute the network’s loss rate, that subsequently informs the network’s attributes and facilitates its training. In this process, the network’s output is evaluated against the correct answer using an error function, and the error rate is computed. The methodology for calculating errors is defined in Eq. (17):

The cost function \(L\left( {Q,\hat {Q}} \right)\) measures the penalty paid by erroneously predicting \(\hat {Q}\) instead of Q. Subsequent to the computation of the error percentage, the post-propagation procedure commences. At this point, the gradient of each parameter is calculated utilizing the chain rule, and all variables are adjusted according to their influence on the error produced in the network.

Initializing

CNN generally must learn a complex nonlinear model, and different initializers often lead to diverse convergence rates and results. Adjusting parameters is challenging, as the neural network fails to acquire essential properties during backpropagation if entire layer weights are set at 0 or 1. Moreover, an excessively large starting value will lead to an inflated gradient, whilst an insufficient initial value would produce a disappearing gradient; both phenomena impair the network’s learning capability35. The aforementioned concerns must be addressed by choosing a suitable weight initialization method that meets the following criteria.

-

Prevent the neuronal activity values of each layer from reaching saturation.

-

Prevent the activation values of each layer from approaching zero.

Nonetheless, network optimization may encounter challenges due to the prevalent utilization of the random normal method for weight initialization. If the random distribution is improperly generated, the output value of the deep network may converge to zero, resulting in a vanishing gradient. The primary objective is to avert the convergence of all output values to zero, sustain uniformity in the activation values and gradient variances throughout each layer during the propagation process, and guarantee that each layer obtains pertinent feedback during backpropagation. This initialization is useless with the ReLU function. To preserve variance and guarantee that 50% of the neurons in every layer are activated, we halve the initialization, as referenced in36 and demonstrated by Eqs. (18) and (19).

Where wj denotes the weight of a certain layer. qj represents the quantity of input neurons in layer j. qj+1 denotes the quantity of output neurons in layer j + 1. The primary distinction between Eqs. (13) and (14) is the division by 2, which reduces the range of the uniform distribution by a factor of 2. The next section presents a comparison of many established weight initialization strategies in clear and succinct language. This approach is employed in our network due to the advantages of the ReLU activation capability.

Optimization of hyperparameters

Hyperparameters refer to the specific configuration choices made during the development of a model’s architecture. The effectiveness of a model based on neural networks relies on the careful selection of suitable hyperparameters. Hyperparameter tuning involves the determination of optimal hyperparameters. This research employs the Random Search heuristic for hyperparameter optimization. This technique determines the ideal solution by methodically exploring a hyperparameter search space and conducting experiments with random parameter combinations. Estimating the position of objects in complex scenes using neural networks shows that deep models have the ability to resolve fine details in crowded images. This ability could be useful for improving the interpretation of cellular images in genomic analyses41. The hyperparameters yielding the highest accuracy values are selected. The model may be trained on optimal parameters free from aliasing, since we have chosen the hyperparameters using the approach. To provide a fair assessment of the proposed framework’s performance, we have adjusted the hyperparameters for each comparative method utilized in this study. The several hyperparameters included in the proposed approach are listed in Table 3.

Evaluation

We utilized the prescribed approach for cancer categorization. The preliminary phase of dataset preparation entailed data normalization. A feature selection module was subsequently utilized to choose a subset of features, which was then fed into the DNN for training. To improve the effectiveness and resilience of the model, we performed tests utilizing several network optimization methodologies.

Evaluation metrics

This section outlines the assessment measures employed to evaluate the effectiveness of our planned research. In this study, we utilized many known evaluation criteria. The metrics are presented in Eqs. (20) through (28).

The provided illustrations present key evaluation metrics used in cancer classification. These metrics are essential for assessing the performance and reliability of diagnostic models42.

-

True Positive (TP): This metric represents the correct identification of cancerous samples as cancer. It indicates that the model successfully detected cases where cancer is present.

-

False Positive (FP): This metric refers to the incorrect classification of non-cancerous samples as cancerous. It represents instances where the model falsely alarms by diagnosing cancer in healthy individuals, potentially leading to unnecessary treatments or anxiety.

-

True Negative (TN): This metric captures the accurate classification of non-cancerous samples as non-cancerous. It reflects the model’s ability to correctly identify healthy individuals and avoid misdiagnosis.

-

False Negative (FN): This metric signifies the incorrect classification of cancerous samples as non-cancerous. Such errors are critical as they represent missed diagnoses, which could delay necessary treatment and adversely affect patient outcomes.

Results

This part analyzes all evaluation measures presented in part 3.2 and conducts simulations on all datasets outlined in Sect. 3.1. We do a comparative study utilizing several methodologies, including Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Sparse Independent Component study (SICA), Deep Belief Networks (DBN), Autoencoder-based Deep Neural Networks (AEDNNs), and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest (RF) and K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN)43,44,45. This enhances our comprehension of the efficacy of our technique in comparison to other fundamental options. Additionally, we evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed method against many recognized algorithms for cancer categorization. Additionally, we do ablation research to examine the impact of various approaches on the efficacy of our strategy. The Python programming language has been only utilized for code development. We utilized many Python libraries, including pandas, NumPy, TensorFlow, and Scikit-learn, for the experimental work. We have furthermore utilized other public GitHub repositories. An examination was conducted using a PC that had an Intel Core i7 12th generation CPU and 16GB of RAM.

Figures 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 presents an examination of GONF’s success throughout its first development, considering various learning rates. The research indicates that the specified strategy outperforms in every category. The learning rate, models, and performance metrics are modified for the research. The performance measurements exhibit both positive and negative characteristics. The Net Present Value (NPV) and the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) are precise performance metrics indicative of favorable outcomes. Contrary metrics, such as the False Positive Rate (FPR) and the False Negative Rate (FNR), are also examined. The speed differential relative to other models has been determined.

As can see in Fig. 8, the GONF method has better FPR ratio than other baseline methods. With a FPR of less than 2%, GONF outperforms CNN by 3%, GAN by 1.5% and SVM, RF by 6%. This metric is essential in clinical cancer screening systems, as a false positive can lead to psychological distress, unnecessary biopsies, increased financial burden, and waste of clinical resources. High FPR also undermines patient trust in diagnostic systems. Additionally, a high FPR erodes patient confidence in diagnostic tools. By using the mRMR gene selection technique, which eliminates redundant and uninformative features early in the pipeline and lowers the possibility of incorrect positive classifications, GONF is able to achieve its superior FPR. Additionally, the specially designed CNN architecture of GONF is explicitly trained using a hyperparameter optimization and a carefully calibrated dropout strategy, increasing its resistance to noise and irrelevant correlations in microarray data. By concentrating on biologically significant gene signatures, these architectural decisions enable GONF to reduce the rate of incorrectly classifying healthy people.

As shown in Fig. 9 the GONF also excels in minimizing the FNR compared to other baseline methods. False negatives mean missing real cancer cases, which can lead to poor prognoses, delayed treatments, and disease progression, making this metric crucial in cancer diagnostics.

In contrast, GONF reduced FNR by 2% on the TCGA and AHBA datasets, a substantial improvement over GANs (3.5%), CNNs (5%), SICA (6%), DBNs (4%), AEDNNs (3%) and classical methods (SVM, KNN, RF) by average of 7%.This significant reduction is attributed to GONF’s synergistic use of mRMR for robust feature selection and its optimized CNN architecture for precise classification, making it a more reliable and accurate framework for cancer classification. The robust hierarchical feature extraction of GONF, which is intended to identify subtle and intricate gene expression patterns linked to malignancy, is directly responsible for its capacity to reduce FNR. By combining denoising, image preprocessing, and the watershed segmentation technique, input quality is greatly improved, increasing the model’s ability to identify subtle but clinically significant signals. GONF maintains high sensitivity in detecting true positives, a crucial performance requirement in life-critical healthcare applications, by making sure that highly informative gene features are maintained through mRMR and appropriately emphasized during CNN training. Unlike DBNs, which are prone to trapping local minima during training, or SICA, which lacks robust supervised learning mechanisms, GONF maintains high sensitivity. GANs, while helpful in data augmentation, often lack stability in training, leading to increased FNR. The balanced optimization strategies in GONF, combined with its ability to handle high-dimensional genomic data, allow for more accurate identification of cancer cases, minimizing false negatives and improving its utility for clinical diagnostics.

Furthermore, Fig. 10 illustrates that the NPV model significantly outperforms several baseline methods when applied with an 80% learning percentage. The NPV model outperforms GAN by 20%, CNN by 10%, DBN by 10%, SICA by 25%, AEDNN by 11% KNN by 17 and RF by 14%. These modifications indicate that the model has improved its negative predictive values, hence enhancing its accuracy and reliability in predicting negative instances. Robust preprocessing, efficient feature selection, and an optimized deep neural network that can differentiate between normal and abnormal gene expressions all work together to make this possible. Even with complex or noisy input, the model will generalize well thanks to the addition of dropout and regularization, which further reduce overfitting. In clinical screening, where accurately ruling out cancer is just as crucial as accurately detecting it, the model’s cautious approach to negative classification is particularly helpful. Because of its high NPV, the GONF method is a reliable tool for early and accurate cancer screening, ensuring that fewer true cancer cases are missed.

Similarly, Fig. 11 illustrates that the FDR approach significantly outperforms the baseline methods when its learning percentage is 80%. It surpasses GAN by 17%, CNN by 13%, DBN by 13%, SICA by 22%, and AEDNN by 11%. The FDR technique effectively reduces the false discovery rate, facilitating the model’s capacity for accurate predictions by minimizing false positives. These results indicate that the NPV model and FDR outperform previously utilized prediction approaches.

As shown in Fig. 11, GONF achieves a lower FDR compared to other methods. FDR evaluates how many of the model’s positive predictions are actually incorrect, and thus has direct implications on the precision and trustworthiness of diagnostic recommendations. A high FDR not only causes patient distress but also diverts medical attention from genuine cases. GONF’s low FDR is a reflection of its comprehensive multi-stage pipeline that includes denoising, spatial alignment, robust gene filtering, and deep convolutional analysis.

Using mRMR ensures that the selected features are both highly relevant and minimally redundant, effectively reducing the inclusion of noisy or irrelevant genes that could lead to false discoveries. While GANs and AEDNNs show FDRs of around 7% and 10% respectively, they lack the fine-tuned feature selection and classification integration seen in GONF. Traditional CNNs and DBNs exhibit higher FDRs of approximately 8%, with SICA being the least effective, showing an FDR of 12%. In contrast, GONF consistently achieves an FDR below 14%, demonstrating its superior precision. GANs, despite their capacity for generating synthetic data, are prone to instability during training, which increases FDR. SICA’s unsupervised nature and lack of robustness exacerbate false discoveries. GONF’s balanced framework, capable of precise gene selection and accurate classification, ensures fewer false positive predictions, cementing its reliability for cancer diagnostics.

MCC is a powerful metric for evaluating classification performance, particularly under imbalanced class distributions, which are common in cancer datasets. It provides a single value that combines all confusion matrix components, offering a balanced view of model performance. GONF’s superior MCC indicates that it consistently achieves a strong correlation between true and predicted classifications across all categories. This is achieved through GONF’s layered feature reduction and abstraction, in which early-stage preprocessing uniformity, and later-stage convolutional layers focus on learning non-linear gene dependencies. Figure 12 illustrates that at the 50% learning stage, the GONF scheme significantly outperforms several baseline algorithms. GANs and AEDNNs achieve MCC scores of 0.85 and 0.87, but their lack of robust segmentation and feature refinement limits their efficacy. CNNs and DBNs score slightly lower at 0.83 and 0.82, while SICA performs the worst with an MCC of 0.78 due to its inability to handle high-dimensional and noisy data effectively. Also, SVM and KNN with MCC score 0.7 have shown relatively poor performance. In the meantime, the RF algorithm with MCC score of 0.78 has relatively better performance.

Comparison with other methods

Alongside its comparison to conventional machine learning techniques, we also evaluate the efficacy of GONF against several novel, state-of-the-art approaches for cancer classification utilizing microarray data46,47,48,49,50,51. This approach assesses the assessment criteria and results for both types of data. The responses evaluated in the AHBA and TCGA datasets are presented adjacent in Figs. 13 and 14. The GONF model is the most precise (Fig. 13) and the second-highest performer in the TCGA dataset for accuracy, recall, and F1 score. This comparison demonstrates the efficacy of GONF in generating precise predictions for cancer classification tasks, rivaling other models. One of GONF’s most advantageous attributes is its little computational power need, rendering it ideal for real-time applications and environments with constrained resources where operational power may be limited. The model consistently performs favorably across all assessment metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score, ensuring equitable and reliable performance. Its efficacy in minimizing the number of false positives and false negatives demonstrates its effectiveness in therapeutic contexts.

Furthermore, the evaluation of the proposed GONF framework on the AHBA dataset highlights its remarkable effectiveness, as it outperforms all competing methods in both accuracy and precision, as illustrated in Fig. 14. These results underscore GONF’s strong ability to correctly identify true cancer cases while simultaneously minimizing the occurrence of false positives. While high accuracy shows the model’s overall robustness in both cancerous and non-cancerous classifications, high precision means fewer patients receive incorrect cancer diagnoses, reducing needless treatments and the stress they cause. GONF’s multi-stage processing pipeline, which consists of rigorous gene selection using mRMR, efficient denoising, and advanced preprocessing techniques, is directly responsible for its high accuracy. The model can eliminate noise or redundancy and concentrate on the most biologically significant features thanks to this design, producing predictions that are more reliable and consistent. GONF exhibits significant performance in recall and F1 Score, despite not achieving the absolute highest values in these metrics. When evaluating a diagnostic tool’s comprehensiveness, recall and F1 score are both essential. The marginally lower recall indicates a chance to improve the detection of all positive instances, perhaps by using data augmentation techniques or further fine-tuning the feature extraction process. With only minor compromises in some metrics, GONF’s performance on the AHBA dataset generally validates its accuracy, dependability, and diagnostic capability. Its steady strength across a number of evaluation criteria shows that the system is well-balanced and ready for use in genomics-based cancer detection.

Furthermore, Tables 4 and 5 unequivocally demonstrate that GONF yields dependable and efficient outcomes across several performance metrics. GONF is an effective method for cancer classification because to its high accuracy and precision, as well as its improvement in memory and F1 Score. The model’s capacity to deliver precise outcomes across several criteria demonstrates its robustness and utility. It is currently an effective instrument for clinical decision-making and patient management in cancer categorization utilizing microarray data.

Statistical analysis

To evaluate the significance of the reported enhancements, the results obtained from several iterations of each method were analyzed statistically using IBM SPSS V.26. Additionally, in conjunction with the typical calculation of descriptive statistics (mean ± SD), MANOVA and Tukey’s test were performed for each evaluation metric (Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1, and AUC) to ascertain any significant differences in the comparisons conducted. The selected significance level was 0.05. The MANOVA test aims to determine whether there is a significant difference among the outcomes. Tukey’s HSD test facilitates the comparison of each pair of means, allowing us to ascertain whether pairs have a significant difference. The results obtained from the MANOVA analysis are displayed in Table 6.

The MANOVA test results inside Table 6 show a statistical distinction between the mean values of all tested metrics which includes Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1, and AUC. Running the Tukey’s HSD test becomes necessary when performing additional research about pairwise analysis. HSD test evaluated the importance of disparities between each pair of algorithms as shown in Table 7. The main focus of statistical analysis within this section evaluates the outcomes from the leading successful strategy against alternative testing methods. Table 7 shows the results obtained from the HSD test applied to three pairs consisting of the research strategy and its best competing approaches. Q represents the studentized range statistic according to the table. The Q score derives from evaluating the two mean values being studied.

The results of Tukey’s HSD test reveal a significant difference between the superior outcomes achieved by GONF and those of its equivalents in most instances. However, there were a few instances where the difference was not deemed substantial. These exceptions arose for the AEDNN and CNN algorithms. The Tukey’s HSD test indicated that the enhancement in precision attained by the suggested method relative to the AEDNN method is not statistically significant. A comparable scenario is noted regarding the discrepancies between the outcomes of the GONF and CNN algorithms, specifically with Precision and F1, which were statistically insignificant.

Ablation analyzes

This section conducts ablation research to evaluate the impact of various components of our proposed approach on the results. We analyze the impacts of segmentation, augmentation, and denoising in proposed methodology. Eight distinct outcomes were assessed for the subsequent configurations: Proposed GONF (incorporating segmentation, augmentation, and denoising); GONF excluding denoising, segmentation, and augmentation; GONF omitting denoising and augmentation; GONF lacking augmentation and segmentation; GONF devoid of augmentation; GONF absent of denoising; and GONF without denoising. The below algorithms have been employed for this objective.

-

Segmentation: Utilizing Conditional Random Fields (CRF) to identify and segment named items within data.

-

Augmentation: Implementing random insertions, deletions, or character swaps in a data record to produce new samples.

-

Denoising: Utilizing Bayesian reasoning to ascertain the fundamental noise-free data.

The results for the TCGA and AHBA datasets, presented in Tables 8 and 9, respectively, indicate that the GONF surpasses other model versions. This exceptional result underscores the efficacy of integrating various methodologies to improve forecast accuracy and dependability. In the scenarios when a single component is eliminated, GONF without denoising yields the optimal outcomes for the TCGA Dataset, but GONF without segmentation excels for the AHBA Dataset. This signifies that both denoising and segmentation substantially influence the model’s performance, but their effects may differ based on the dataset. The removal of two components indicates that GONF, without both denoising and segmentation, and GONF, devoid of augmentation and segmentation, attain optimal performance for the TCGA and AHBA datasets, accordingly. This discovery highlights the necessity of integrating both augmentation and denoising strategies, since their omission reduces the model’s efficacy in managing complicated data. The combined impacts of segmentation and denoising with augmentation approaches are clear, demonstrating that each element is essential for improving the overall performance of GONF.

Tables 8 and 9 demonstrate that each component uniquely enhances the model’s overall predictive power, and their collective impact exceeds the aggregate of their separate contributions. The significance of each component is evident when examining their interactions and mutual enhancements. Denoising purifies the data, segmentation delineates pertinent features, and augmentation enhances the variability of the training data. The elimination of any one component undermines this synergy, resulting in a significant reduction in performance. This illustrates the effective collaboration of these parts in extracting and enhancing pertinent information regarding cancer from photos, hence optimizing the model’s predictive accuracy.

Conclusion

This study aimed to develop a comprehensive system, GONF, for cancer classification using DNN and microarray data, emphasizing enhanced accuracy, efficiency, and reliability in clinical applications. GONF integrates advanced statistical techniques, such as mRMR for feature selection, and deep neural networks to optimize gene selection and feature extraction processes. The model employs image processing techniques, including Watershed segmentation, to preprocess microarray data effectively, reducing noise and isolating regions of interest, which improves the quality of input features. By feeding these refined features into its deep learning architecture, GONF demonstrated superior performance in cancer classification tasks. The model was tested against state-of-the-art methods, including GANs, CNNs, DBNs, SICA, and AEDNNs, showing consistently higher accuracy, recall, and precision. GONF achieved classification accuracy improvements on the TCGA dataset and AHBA dataset, significantly outperforming the comparative models. Additionally, it demonstrated lower false positive and false negative rates, contributing to its robust predictive capability and reliability in clinical diagnostics. These results highlight GONF’s potential as a powerful tool for healthcare professionals, improving diagnostic accuracy, reducing errors, and enabling timely, personalized treatment planning. The model’s ability to process large datasets efficiently further supports decision-making and resource management in healthcare.

While promising, the GONF model faces certain limitations. Its computational complexity may limit implementation in resource-constrained environments with limited infrastructure or expertise in deep learning. Additionally, although the model performed well on specific datasets, further validation on diverse and larger datasets is needed. Future work should focus on extending its applicability by incorporating real-time data processing, broader datasets, and additional data types such as genomic and lifestyle factors, while refining its segmentation and preprocessing techniques for greater adaptability.

Data availability

Availability of data and materials: The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data used in this study are publicly available through the Genomic Data Commons (GDC) portal: https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/, accession number: phs000178.v11.p8.The Allen Human Brain Atlas (AHBA) data are publicly available from the Allen Institute for Brain Science: https://human.brain-map.org/, donor IDs: H0351.1009, H0351.1015, H0351.1012, H0351.1016, H0351.2001, H0351.2002.

References

Alharbi, F. & Vakanski, A. Machine learning methods for cancer classification using gene expression data: a review. Bioengineering 10 (2), 173 (2023).

Deng, X., Li, M., Deng, S. & Wang, L. Hybrid gene selection approach using XGBoost and multi-objective genetic algorithm for cancer classification. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 60 (3), 663–681 (2022).

Khalsan, M. et al. Fuzzy gene selection and cancer classification based on deep learning model (2023). arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.04883.

Mazlan, A. U. et al. A review on recent progress in machine learning and deep learning methods for cancer classification on gene expression data. Processes 9 (8), 1466 (2021).

Bontonou, M. et al. A comparative analysis of gene expression profiling by statistical and machine learning approaches. Bioinform. Adv. (2024).

Basavegowda, H. S. & Dagnew, G. Deep learning approach for microarray cancer data classification. CAAI Trans. Intell. Technol. 5 (1), 22–33 (2020).

Samiei, M. et al. Classification of skin cancer stages using a AHP fuzzy technique within the context of big data healthcare. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 149 (11), 8743–8757 (2023).

Wu, H., Li, X. & Zhang, J. Gene selection and cancer classification using convolutional neural networks. Comput. Biol. Chem. 93, 107487 (2023).

Zhang, H., Lin, C. & Wu, F. Cancer classification using deep neural networks and gene selection techniques. Bioinformatics 38 (6), 1814–1822 (2022).

Wang, W., Yin, B., Li, L., Li, L. & Liu, H. A low light image enhancement method based on dehazing physical model. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 143 (2), 1595–1616. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.063595 (2025).

Li, Z., Liu, Q. & Huang, W. A hybrid method combining convolutional neural network and gene selection for cancer classification. IEEE Access. 9, 109035–109045 (2021).

Zhang, R. et al. MvMRL: a multi-view molecular representation learning method for molecular property prediction. Brief. Bioinform. 25 (4), bbae298. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbae298 (2024).

Yao, Y., Gao, J. & Zhang, W. A deep learning approach to cancer diagnosis using gene expression data: a comparative study. Bioinformatics 38 (7), 1811–1819 (2022).

Ghosh, S. & Patel, D. A comparative study of machine learning algorithms for cancer classification using gene expression data. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 19 (4), 1078–1086 (2023).

Luo, Z. & Li, Z. A hybrid deep learning model for cancer classification using gene selection techniques. Med. Image. Anal. 74, 102350 (2023).

Men, X. et al. Exploring the pathogenesis of chronic atrophic gastritis with atherosclerosis via microarray data analysis. Medicine 103 (16), e37798. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000037798 (2024).

Shah, R. & Patel, P. A novel hybrid deep learning model for gene selection and cancer classification. Comput. Biol. Chem. 98, 107471 (2023).

Chen, X. & Jing, R. Video super resolution based on deformable 3D convolutional group fusion. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 9050. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93758-z (2025).

Li, Z., Li, F. & Liu, Q. A deep convolutional neural network model for cancer classification using gene expression profiles. Neurocomputing 473, 157–168 (2023).

Xu, T., Wu, F. & Zhang, Y. Feature selection and cancer classification using neural networks and microarray data. J. Comput. Biol. 28 (5), 523–533 (2021).

Liu, R., Wang, S., Tian, F. & Yi, L. SIR-3DCNN: a framework of multivariate time series classification for lung cancer detection. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 74, 2563. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2025.3563000 (2025).

Zafar, S., Ahmad, J., Mubeen, Z. & Mumtaz, G. Enhanced lung cancer detection and classification with mRMR-Based hybrid deep learning model. J. Comput. Biomed. Inf. 7, 2 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Identification of human microRNA-disease association via low-rank approximation-based link propagation and multiple kernel learning. Front. Comput. Sci. 18(2), 182903 (2024).

Wang, J., Chen, Y. & Zou, Q. Inferring gene regulatory network from single-cell transcriptomes with graph autoencoder model. PLoS Genet. 19(9), e1010942 (2023).

Alsuhimat, F. M. & Mohamad, F. S. A hybrid method of feature extraction for signatures verification using CNN and HOG a multi-classification approach. IEEE Access. 11, 21873–21882 (2023).

Das, A., Neelima, N., Deepa, K. & Özer, T. Gene selection based cancer classification with adaptive optimization using deep learning architecture. IEEE Access (2024).

Zeng, Y., Zhang, Y., Xiao, Z. & Sui, H. A multi-classification deep neural network for cancer type identification from high-dimension, small-sample and imbalanced gene microarray data. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 5239 (2025).

Zeng, Y. et al. GCCNet: a novel network leveraging gated Cross-Correlation for Multi-View classification. IEEE Trans. Multimedia. 27, 1086–1099. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMM.2024.3521733 (2025).

Zhang, Y. & Liu, M. A novel deep neural network model for cancer classification with gene expression data. IEEE Trans. Comput. Biology Bioinf. 20 (3), 854–863 (2023).

Wang, W., Yuan, X., Wu, X. & Liu, Y. Fast image dehazing method based on linear transformation. IEEE Trans. Multimedia. 19 (6), 1142–1155. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMM.2017.2652069 (2017).

Li, P. & Yang, Z. A hybrid gene selection approach for cancer classification using deep learning methods. Comput. Biol. Med. 139, 104800 (2022).

Chen, W. et al. Cross-Modal causal representation learning for radiology report generation. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 34 ({}), 2970–2985. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2025.3568746 (2025).

Yin, L. et al. Convolution-Transformer for image feature extraction. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 141 (1), 87–106. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2024.051083 (2024).

He, B. et al. A fusion model to predict the survival of colorectal cancer based on histopathological image and gene mutation. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 9677. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91420-2 (2025).

Zhao, S. & Liu, T. Deep learning-based cancer classification from gene expression profiles. Artif. Intell. Med. 114, 101046 (2021).

Liu, Z. et al. Proteomic analysis reveals chromatin remodeling as a potential therapeutical target in neuroblastoma. J. Translational Med. 23 (1), 234. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-025-06298-5 (2025).

Yang, Z. et al. Integrative analysis of genomic and epigenomic regulation reveals MiRNA mediated tumor heterogeneity and immune evasion in lower grade glioma. Commun. Biology. 7 (1), 824. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-06488-9 (2024).

Zhang, G. et al. TRAPT: a multi-stage fused deep learning framework for predicting transcriptional regulators based on large-scale epigenomic data. Nat. Commun. 16 (1), 3611. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58921-0 (2025).

Luan, F., Cui, Y., Huang, R., Yang, Z. & Qiao, S. Comprehensive pan-cancer analysis reveals NTN1 as an immune infiltrate risk factor and its potential prognostic value in SKCM. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 3223. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85444-x (2025).

Han, L. et al. Causal associations between HbA1c and multiple diseases unveiled through a Mendelian randomization phenome-wide association study in East Asian populations. Medicine 104 (11), e41861. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000041861 (2025).

Al-Selwi, M. et al. Enhancing object pose Estimation for RGB images in cluttered scenes. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 8745. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90482-6 (2025).

Zeng, C. & Zhang, W. Classification of cancer data using deep learning methods: a systematic review. Genetic Eng. Biotechnol. J. 41 (3), 307–319 (2022).

Wang, J. & Li, Y. Hybrid deep learning approaches for gene expression data and cancer classification. Comput. Biol. Chem. 93, 107466 (2021).

Wu, P. & Lu, C. Machine learning and deep learning models for cancer classification with microarray gene expression data. J. Clin. Bioinform. 13 (1), 22 (2023).

Zhao, Q. & Sun, Y. A novel deep neural network model for cancer classification using gene expression data. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 3123 (2022).

Zhang, H. & Sun, Z. A hybrid feature selection and classification approach for cancer diagnosis based on gene expression data. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 68 (8), 2681–2689 (2021).

Li, Y. & Li, P. A convolutional neural network approach for cancer classification based on gene expression. BMC Cancer. 23 (1), 523 (2023).

Chen, J. & Zhang, Q. Deep learning for cancer diagnosis using gene expression profiles: a review. Artif. Intell. Med. 106, 101778 (2022).

Zhang, T. & Wu, Z. Multi-objective genetic algorithm for feature selection in cancer classification using deep learning. Comput. Biol. Chem. 92, 107412 (2023).

Wang, Q. & Guo, Z. A hybrid approach combining feature selection and deep learning for cancer classification. Comput. Biol. Med. 147, 105417 (2024).

Tan, Z. & Wu, J. An improved deep learning model for cancer classification using gene expression data. IEEE Access. 11, 4692–4700 (2023).

Acknowledgements