Abstract

This study aimed to utilize various machine learning algorithms to develop a predictive model for the progression of severe community-acquired pneumonia (SCAP) in children to critical severe community-acquired pneumonia (cSCAP). Retrospective analysis of clinical data of SCAP patients admitted to the Department of Pediatric Intensive Care Medicine at the First Affiliated Hospital of Bengbu Medical University from January 2021 to April 2023. Logistic regression (LR) and Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) were jointly employed to screen model variables. The selected variables were then incorporated into seven algorithms, namely LR, Decision Tree (DT), Random Forest (RF), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), Naive Bayes (NB), k-Nearest Neighbor (KNN), and Support Vector Machine (SVM), to establish a predictive model for the progression of SCAP in children to a critically severe stage. The effectiveness of the model was evaluated based on the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and F1 score. Finally, the Shapley Additive Explanation (SHAP) algorithm was used to interpret the established machine learning model. A total of 211 patients were included. Red Cell Distribution Width–Coefficient of Variation (RDW-CV), procalcitonin (PCT), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) were selected as predictors. The XGBoost model outperformed six other algorithms, with an AUC of 0.98 (95% CI,0.93–1.00 ), accuracy 0.89 (95% CI, 0.78–0.94), sensitivity 0.98 (95% CI, 0.95–1.00), and specificity 0.75 (95% CI, 0.45–0.87). SHAP analysis identified PCT, LDH, RDW-CV, and BUN as the most important contributors, supporting their clinical relevance for early risk stratification. This study developed an accurate predictive model for the cSCAP in children using machine learning techniques, providing clinical support for decision-making by clinicians.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is the leading cause of death among children under five globally, with 541,000 deaths aged 1 to 59 months in 20191. In China, where under-five mortality is high, pneumonia mortality ranges from 0.6 to 21.7 per 1,000 live births1. Severe CAP (SCAP) is diagnosed based on guidelines when symptoms like refusal to eat, persistent vomiting, seizures, lethargy or coma, rapid breathing, severe respiratory distress, low oxygen saturation (< 0.92), or central cyanosis accompany confirmed infectious pneumonia.

In the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) at Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center, the mortality rate for children with SCAP is 12.3%, with a complication rate of 82.3%. Among these, 77.0% had respiratory failure, 12.4% had septic shock, 6.2% had multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS), and 2.7% had acute renal failure. Additionally, 87.6% required respiratory support, with 78.8% needing invasive ventilation and 8.8% non-invasive support2. Koh et al.3 reported that 68.4% of children admitted to PICU for severe pneumonia required invasive ventilation, with a mortality rate of 13.5%. Some researchers define critical SCAP (cSCAP) in children as cases involving mortality, the need for invasive ventilation, or vasoactive drug support due to shock4.

Therefore, using appropriate tools to classify the severity of pediatric pneumonia is crucial for optimizing disease management. However, unlike in adults, no validated risk assessment tools (e.g., CURB-65, PSI) exist for children5,6,7. Early prediction studies for cSCAP in children are also limited. A 2016 multicenter cohort study developed a prediction model for SCAP in hospitalized children, identifying extreme age, vital signs, chest retractions, and radiographic infiltrates as key predictive factors4. However, this model, based on data from three U.S. cities, may not be directly applicable to China and lacks comprehensive external validation. Prognostic models like the Respiratory Index of Severity in Children (RISC) and the PERCH score were developed in low- and middle-income countries to predict mortality in settings with high pneumonia death rates8,9. These models are limited by their focus on comorbidities like malnutrition, HIV, and malaria, which reduces their relevance in resource-rich countries. Moreover, they rely on clinical symptoms that heavily depend on accurate physician assessment, which can be challenging in uncooperative pediatric patients and may lead to underestimation of disease severity. Literature suggests that objective biomarkers can complement traditional clinical scoring systems and improve decision-making for pediatric CAP severity10,11.

These limitations highlight the urgent need for innovative approaches that integrate objective biomarkers and advanced analytical methods to improve risk stratification. With advancements in statistical theory and computer technology, machine learning techniques have outperformed traditional methods in predictive accuracy. Previous studies have shown that machine learning models can accurately predict the likelihood of pediatric patients needing transfer to the PICU, demonstrating strong predictive performance12. These algorithms have also been used to predict mortality risk in children with severe pneumonia13. Given their potential in handling complex datasets, developing an efficient machine learning prediction model for early identification of cSCAP in children is essential. This would enable timely intervention and improve outcomes.

Materials and methods

Study subjects

This retrospective cohort study involved pediatric patients with SCAP admitted to the PICU of the First Affiliated Hospital of Bengbu Medical College between January 2021 and April 2023. Inclusion criteria were: (1) age 1 to 59 months, and (2) meeting the SCAP diagnostic criteria outlined by the National Health Commission of China in the 2019 guidelines for pediatric CAP14. Exclusion criteria included: (1) patients with neuromuscular diseases, specific genetic disorders (e.g., cystic fibrosis or primary immunodeficiency), or bone marrow suppression from hematologic malignancies; (2) hospital-acquired infections; (3) current or recent use of immune-affecting medications like long-term high-dose corticosteroids or other immunosuppressants; and (4) incomplete data.

Diagnostic criteria

(1) SCAP Criteria: According to the 2019 pediatric CAP guidelines from China’s National Health Commission, SCAP is defined as the presence of any one of the following criteria: poor general condition; impaired consciousness; or hypoxaemia, which includes cyanosis, respiratory rate ≥ 70 breaths/min in infants or ≥ 50 breaths/min in children over 1 year of age, signs of assisted respiration (such as groaning, nasal flaring, or the triple concavity sign), intermittent apnoea, or transcutaneous oxygen saturation < 92%. Additional criteria include ultrahigh fever or persistent hyperthermia lasting more than 5 days; refusal to eat or dehydration; abnormal chest radiographic or CT findings, such as ≥ 2/3 unilateral pulmonary infiltrates, multilobar pulmonary infiltrates, pleural effusion, pneumothorax, pulmonary atelectasis, pulmonary necrosis, or pulmonary abscess; and the presence of extrapulmonary complications12.

(2) cSCAP Criteria: cSCAP in children is defined based on previous studies as SCAP cases meeting any of the following criteria: mortality; the need for invasive mechanical ventilation; or shock requiring vasoactive drug support4.

Ethical approval and informed consent

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the First Affiliated Hospital of Bengbu Medical College (No. 2023YJS138) and complied with the Declaration of Helsinki (2013). The Institutional Review Board of the First Affiliated Hospital of Bengbu Medical College waived informed consent due to the retrospective design, fully anonymized data (all identifiers irreversibly removed), and minimal participant risk, in accordance with China’s Personal Information Protection Law (Article 39). Processed data were securely stored on password-protected servers with restricted access, meeting requirements of Cybersecurity Law (Article 21).

Study variables

Data on SCAP in children were obtained from the electronic medical record system. The study variables included: (1) Demographic information: age, gender; (2) Hematological indicators within 24 h of PICU admission: white blood cell count (WBC), neutrophil count, lymphocyte count, monocyte count, Neutrophil Ratio, Lymphocyte Ratio, hemoglobin, red cell distribution width-coefficient of variation (RDW-CV), platelet count, procalcitonin (PCT), C-reactive protein (CRP), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), total protein, albumin, globulin, creatinine, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), creatine kinase isoenzyme MB (CK-MB), prothrombin time (PT), fibrinogen, D-dimer, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), neutrophil-to-monocyte ratio (NMR), systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), and albumin-globulin ratio (AGR).

Variable selection for the prediction model

Variable selection is crucial in predictive modeling to enhance both performance and generalizability. Traditional approaches fall into two main categories: selection based on statistical significance (e.g., logistic regression) and selection based on predictive strength (e.g., LASSO regression). To ensure a robust feature selection process, this study employed a two-step strategy combining both methods. First, univariate logistic regression was performed to evaluate the association between each candidate variable and the outcome, using a significance threshold of p < 0.05. To address multicollinearity, variance inflation factor (VIF) analysis was conducted, and variables with VIF > 5 were excluded. The remaining variables were then entered into a multivariate logistic regression model, retaining only statistically significant predictors. Next, LASSO regression was applied to further refine the feature set by penalizing less informative variables, with the optimal penalty parameter (λ) determined via 10-fold cross-validation. The final predictor set was obtained by intersecting the features selected by both logistic regression and LASSO regression. This dual-selection approach ensured that the chosen variables were not only statistically significant but also practically relevant, mitigating the risk of redundancy from significance testing alone and the potential omission of important predictors by LASSO.

Construction and evaluation of machine learning models

The collected data were randomly divided into a training set and a validation set in a 7:3 ratio for model construction and validation, respectively. Logistic regression and LASSO regression were applied to select variables from the training set. A Venn diagram was then used to identify the common variables. For model development, we prioritized reproducibility and clinical interpretability by retaining the default hyperparameters for most algorithms, adjusting only when necessary. Specifically, the XGBoost model (implemented via xgboost 1.7.7 in R) used the following settings: learning_rate (eta) = 0.1, max_depth = 5, and n_estimators = 100. This configuration was chosen to balance computational efficiency and model stability. Shallow trees reduce the risk of overfitting, which is especially important for moderate-sized datasets (n = 211). The parameter robustness was assessed systematically through 10-fold cross-validation during model development.

We used the selected variables to construct models for predicting the critical type of SCAP in children. Seven machine learning classification algorithms were employed: logistic regression (LR), decision tree (DT), random forest (RF), extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost), naive Bayes (NB), k-nearest neighbor (KNN), and support vector machine (SVM). The models were tested using the validation set. Model performance was evaluated using several metrics: accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, F1 score, and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). We calculated the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for AUC using DeLong’s method, and applied bootstrapping with 1,000 resamples to estimate CIs for other performance metrics. Finally, the best-performing model’s interpretability was assessed using Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP). SHAP quantifies the contribution of each feature to individual predictions, offering insights into the roles of biomarkers and aiding clinical decision-making. A predefined threshold sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate the impact of decision threshold adjustments on model performance. For models with specificity below the prespecified floor of 0.75 in the validation set, the classification threshold was varied from 0.30 to 0.90 at 0.05 intervals. Sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and F1 score were recorded to characterize trade-offs between sensitivity and specificity. LR was selected for its simplicity and interpretability, especially for modeling linear relationships. DT and RF were included for their ability to handle complex, non-linear relationships, with RF benefiting from ensemble learning to reduce overfitting. XGBoost was chosen due to its ability to handle large datasets and its superior performance in machine learning competitions. NB was used as a baseline probabilistic model, while KNN and SVM were considered for their strong performance in classification tasks involving high-dimensional data. These methods were selected not only for their predictive capabilities but also for their interpretability and computational efficiency, which are crucial in a clinical setting where timely decision-making is essential.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables with a normal distribution were expressed as X ± S, and intergroup comparisons were conducted using the t-test. Continuous variables with a skewed distribution were expressed as medians (M) and interquartile ranges (P25, P75), with intergroup comparisons conducted using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were expressed as numbers and percentages, with intergroup comparisons performed using the χ² test or Fisher’s exact test. Spearman correlation analysis was used to assess correlations between variables (a correlation coefficient of + 1 indicates a perfect positive correlation, − 1 indicates a perfect negative correlation, and an absolute value less than 0.5 indicates a weak correlation). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0 and R 4.2.2, with a threshold of p < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Result

Basic characteristics of the training and validation sets

From January 2021 to April 2023, 225 patients with SCAP were admitted to the PICU of the First Affiliated Hospital of Bengbu Medical College. After excluding 14 patients (6 due to incomplete key variable data and 8 for other reasons), 211 patients were included in the final analysis. Missing data were handled using complete case analysis. Patients were randomly divided into a training set (n = 148) and a validation set (n = 63) in a 7:3 ratio, with no significant differences in baseline characteristics between the two groups (P > 0.05, Table 1).

Variable selection for the prediction model

To develop a robust prediction model, we employed a systematic variable selection strategy that combined logistic regression and LASSO regression. First, univariate logistic regression identified statistically significant variables (Table 2). To ensure their independence, we conducted a multicollinearity analysis and excluded variables with VIF greater than 5 (Fig. 1), thereby reducing potential redundancy. The remaining variables were then analyzed using multivariate logistic regression (Table 3), identifying five key predictors: RDW-CV, PCT, BUN, LDH, and fibrinogen. In parallel, LASSO regression was applied to refine the variable selection process (Fig. 2), resulting in four key variables: RDW-CV, PCT, BUN, and LDH. A Venn diagram (Fig. 3) revealed that fibrinogen was retained only in the logistic regression output but excluded by LASSO, resulting in four consensus biomarkers. Finally, we generated a correlation heatmap (Fig. 4) to validate the independence of the selected variables, ensuring the stability and optimization of our predictive model. These four biomarkers were consistently identified by both methods, reinforcing their predictive value in our final model.

Collinearity analysis of variables after univariate analysis. This figure shows the results of the multicollinearity analysis performed using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) to assess the independence of variables. Variables with a VIF greater than 5, such as neutrophil count, NLR, SII, and WBC, were excluded from the analysis to ensure no multicollinearity in the model. The figure illustrates the VIF values for all included variables.

LASSO regression results. This figure illustrates the results of the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) regression used for variable selection. The left panel shows the mean-squared error (MSE) as a function of the regularization parameter (lambda) in a 10-fold cross-validation process. The vertical dashed lines indicate the optimal lambda values: the left line corresponds to the lambda that minimizes MSE, and the right line corresponds to the lambda chosen using the “one standard error rule” for more conservative variable selection. The right panel shows the coefficient paths for all candidate variables as lambda increases (moving from left to right). Based on the LASSO regression results, four key variables—RDW-CV, PCT, BUN and LDH—were identified as important predictors of cSCAP.

Venn diagram of the two algorithms mentioned above. This figure illustrates the overlap in variable selection between Logistic regression (Logit) and LASSO regression. The Venn diagram highlights four key variables—RDW-CV, PCT, BUN and LDH—that were consistently identified as significant predictors by both methods. These shared variables demonstrate strong agreement between the two regression approaches in identifying critical predictors of cSCAP.

Heatmap of variable correlations in machine learning. This figure presents a heatmap showing the correlations among the selected variables. The size and color of the circles represent the strength and direction of the correlation coefficients. Variables with weak correlations (correlation coefficients close to 0) are considered independent. Key variables such as RDW-CV, PCT, BUN and LDH show low correlations with one another, confirming their independence and ensuring the stability and optimization of the prediction model.

Construction and evaluation of machine learning models

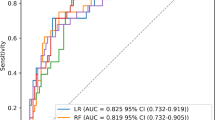

As summarized in Tables 4 and 5; Fig. 5, the seven machine learning models exhibited distinct performance profiles in pediatric cSCAP prediction. XGBoost demonstrated the highest discriminative ability (AUC: 0.98; 95% CI: 0.93-1.00) with sensitivity of 0.98 (0.90-1.00), accuracy of 0.89 (0.78–0.94), and specificity of 0.75(0.45–0.87), while maintaining robust predictive consistency (PPV: 0.88 [0.77–0.96]; NPV: 0.93 [0.64-1.00]; F1-score: 0.92 [0.85–0.97]). RF showed comparable AUC (0.97; 0.89–0.99) but wider confidence intervals in accuracy (0.86; 0.71–0.94) and NPV (0.82; 0.71–0.94). DT achieved the highest specificity (0.80; 0.55–0.94) with accuracy matching XGBoost (0.89; 0.76–0.94), though its NPV range spanned 0.64-1.00. LR attained maximum sensitivity (1.00) but the lowest specificity (0.50; 0.28–0.72), resulting in a PPV of 0.70. Naive Bayes (AUC: 0.76 [0.55–0.91]) and KNN (AUC: 0.77 [0.58–0.88]) displayed suboptimal discrimination, while SVM demonstrated marginal specificity (0.10; 0.00-0.32) despite moderate AUC (0.84; 0.71–0.92). At the default threshold of 0.50, the XGBoost model achieved sensitivity of 0.98 and specificity of 0.75. Threshold sensitivity analysis demonstrated that adjusting the threshold to 0.45 improved specificity to 0.90 but reduced sensitivity to 0.88, illustrating the expected trade-off (Table 6; Fig. 6). Based on these results, the default threshold of 0.50 was retained to prioritize high sensitivity (0.98) and minimize the risk of missed deterioration in PICU patients, despite modest specificity (0.75).

Model interpretation

The SHAP summary plot (Fig. 7) identified PCT as the strongest predictor of progression, followed by LDH, RDW-CV, and BUN. Elevated values of PCT and LDH were associated with increased risk, while lower levels demonstrated protective effects. RDW-CV and BUN also contributed to risk stratification. Patient-level SHAP force plots (Fig. 8) illustrated how risk-enhancing and protective factors interacted within individual predictions, providing transparent, case-specific explanations.

ROC curves of various machine learning algorithms in the validation set. This figure illustrates the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves for seven machine learning algorithms—Logistic Regression (logistic), Decision Tree (dt), Random Forest (rf), XGBoost (xgb), Naive Bayes (nb), K-Nearest Neighbors (knn), and Support Vector Machine (svm)—evaluated on the validation set. The ROC curve demonstrates the balance between sensitivity and specificity for each algorithm. The area under the curve (AUC), presented in the legend alongside the 95% confidence intervals (CIs), serves as a comprehensive metric of model performance. Among the tested algorithms, XGBoost achieved the highest AUC (0.977, 95% CI: 0.949–1.000), highlighting its superior predictive accuracy for cSCAP in children.

Sensitivity analysis of XGBoost performance across different classification thresholds. This figure shows the sensitivity analysis of XGBoost performance for various classification thresholds. As the threshold increases, sensitivity increases, specificity decreases, and the false positive rate rises. The analysis identifies an optimal threshold of 0.45, balancing high sensitivity (0.884) and specificity (0.900), while significantly reducing the false positive rate (0.100). This adjustment leads to an improved F1 score (0.916), optimizing classification performance.

SHAP values for each variable of the XGBoost model. The SHAP summary plot quantified feature contributions to the XGBoost model. The left panel displays the distribution of SHAP values, with the x-axis representing each variable’s effect on prediction (positive = risk-enhancing, negative = protective), and the color scale indicating actual feature values. The right panel shows mean absolute SHAP values, reflecting variable importance. PCT was the most influential predictor (mean |SHAP| = 0.60, range − 0.82 to + 1.02); values > 2.0 ng/mL were strongly associated with progression (SHAP > + 0.45), while values < 0.5 ng/mL were protective (SHAP < − 0.30). LDH ranked second (mean |SHAP| = 0.34), with levels > 400 U/L associated with increased risk (SHAP + 0.12 to + 0.55). RDW-CV and BUN also contributed (mean |SHAP| = 0.12 and 0.08, respectively), with RDW-CV > 14% and BUN > 20 mg/dL linked to elevated risk.

SHAP values of XGBoost model for one patient. The SHAP force plot illustrates an individual-level prediction. Red bars represent risk-enhancing contributions, and blue bars represent protective effects. For this patient (predicted probability = 0.91), LDH = 350 U/L (SHAP + 0.38) and BUN = 3.46 mg/dL (SHAP + 0.22) increased risk, while PCT = 0.53 ng/mL (SHAP − 0.15) and RDW-CV = 14.8% (SHAP − 0.09) mitigated risk. This example demonstrates how the model integrates multiple biomarkers to provide a transparent, individualized explanation.

Discussion

This study aims to develop a machine learning model for the early detection of critical pneumonia in children, a leading cause of illness and death globally. To enhance accuracy and generalizability, several strategies were employed: combining logistic regression and LASSO for feature selection, applying 10-fold cross-validation for model performance assessment, and testing multiple machine learning algorithms to select the best-performing model.

In predictive modeling for cSCAP, the XGBoost model demonstrated exceptional clinical utility. By optimizing bias-variance trade-offs and incorporating enhanced regularization techniques15, it achieved superior feature extraction from medical data, yielding an AUC range of 0.93–1.00 (95% CI), significantly outperforming comparative models. Notably, its clinical value lies in high-risk patient identification, with a sensitivity of 0.98 (95% CI: 0.90–1.00) and a NPV of 0.93 (95% CI: 0.64–1.00), providing reliable confidence in excluding low-risk cases—a critical advantage for emergency triage.

The SHAP analysis provided transparent insights into how individual variables influenced the model’s predictions and highlighted four key biomarkers as the most important contributors. PCT was the dominant predictor, in line with its established role as a marker of bacterial infection severity and systemic inflammation16. Elevated PCT levels were strongly associated with progression to critical illness, consistent with both pediatric and adult studies showing its prognostic value for respiratory failure, sepsis, and the need for vasopressor support17,18,19. LDH ranked second in importance, reflecting its role as a marker of tissue injury and metabolic stress. Prior research has demonstrated that LDH elevation correlates with disease severity across diverse respiratory infections, including viral and Mycoplasma pneumonia20,21,22,23, and in sepsis, where it indicates multi-organ involvement and impaired oxygen delivery24,25. These findings confirm that the model captured biologically plausible signals of severe disease progression.

RDW-CV, a measure of red cell size variability, also emerged as a relevant predictor. Its association with all-cause mortality in critically ill patients is well established26,27, and its inclusion here likely reflects the impact of systemic inflammation and oxidative stress in pediatric pneumonia. Similarly, BUN contributed to risk stratification, potentially serving as an early marker of renal hypoperfusion28, muscle catabolism29, and sympathetic overactivation during sepsis30. While these markers may appear less specific than PCT and LDH, their integration in the model underscores the multifactorial pathophysiology of critical illness in pneumonia and highlights the value of combining routine laboratory tests to enhance prediction accuracy.

The SHAP framework also provides individualized explanations of risk, with patient-level force plots showing how risk-enhancing and protective factors interact. This interpretability increases clinician trust31 and supports dynamic risk assessment. Clinically, the model could be embedded into PICU workflows as a threshold-based alert system, where high predicted risk triggers closer monitoring, or expedited transfer to intensive care32. Such integration may help reduce treatment delays and improve outcomes, particularly in resource-limited settings. Because the model was designed as an early-warning tool in the PICU, we prioritized high sensitivity. At the default threshold of 0.50, the model achieved sensitivity of 0.98 and specificity of 0.75, which we considered an acceptable balance for minimizing missed deterioration. Lowering the threshold to 0.45 increased specificity (up to 0.90) but reduced sensitivity (to 0.88), highlighting the inevitable trade-off between these metrics. Therefore, we retained the default threshold in the main analysis while presenting the sensitivity analysis to illustrate potential clinical implications.

Limitations and future directions

First, missing data were addressed using complete case analysis, which may introduce bias if data were not missing completely at random.

Second, as this was a single-center study limited to PICU patients with severe pneumonia, the generalizability of our findings to other hospitals and patient populations remains uncertain. Differences in institutional protocols, patient demographics, and resource availability may have influenced the results. Future studies should therefore prioritize external validation across multicenter cohorts, including diverse geographic and resource settings, to strengthen robustness and clinical applicability. Prospective validation and integration into real-time clinical workflows will also be essential to confirm the model’s practical utility.

Third, although the model achieved excellent discrimination, its specificity of 0.75 indicates a residual false-positive risk. Our predefined threshold sensitivity analysis demonstrated the trade-off between sensitivity and specificity; future work may consider cost-sensitive learning or multicenter calibration to optimize operating points.

Fourth, the relatively small sample size (n = 211) limits the statistical power to detect subtle performance differences. Larger external cohorts will be required to confirm robustness.

Finally, while our analysis was based on routinely available biomarkers, the economic impact of such monitoring remains unclear, particularly in resource-limited settings, and should be evaluated in future health economics research.

Conclusions

This study developed a machine learning model to predict cSCAP in children, with XGBoost achieving the highest accuracy (AUC 0.98). Key variables contributing to its success were RDW-CV, PCT, BUN, and LDH.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Perin, J. et al. Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000-19: an updated systematic analysis with implications for the sustainable development goals. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health. 6 (2), 106–115 (2022).

Shi, T. et al. Risk factors for mortality from severe community-acquired pneumonia in hospitalized children transferred to the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr. Neonatol. 61 (6), 577–583 (2020).

Koh, J. W. J. C. et al. Risk factors for mortality in children with pneumonia admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 52 (8), 1076–1084 (2017).

Williams, D. J. et al. Predicting severe pneumonia outcomes children. Pediatrics 138(4), e20161019 (2016).

Uwaezuoke SN, Ayuk AC. Prognostic scores and biomarkers for pediatric community-acquired pneumonia: how far have we come? Pediatric Health, Medicine and Therapeutics. 2017; 8: 9–18

Fine, M. J. et al. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl. J. Med. 336 (4), 243–250 (1997).

Aujesky, D. & Fine, M. J. The pneumonia severity index: a decade after the initial derivation and validation. Clin. Infect. Dis. 47 (Suppl 3), S133–S139 (2008).

Reed, C. et al. Development of the respiratory index of severity in children (RISC) score among young children with respiratory infections in South Africa. PloS One. 7 (1), e27793 (2012).

Gallagher, K. E. et al. The predictive performance of a pneumonia severity score in human immunodeficiency virus–negative children presenting to hospital in 7 low-and middle-income countries. Clin. Infect. Dis. 70 (6), 1050–1057 (2020).

Póvoa, P. et al. Biomarkers: Are they useful in severe community-acquired pneumonia? In Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine (Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc., 2024).

Fernandes, C. D. et al. Host inflammatory biomarkers of disease severity in pediatric community-acquired pneumonia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. In Open Forum Infectious Diseases. Vol. 12. 6ofz520 (Oxford University Press, 2019).

Mayampurath, A. et al. Development and external validation of a machine learning model for prediction of potential transfer to the PICU. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 23 (7), 514–523 (2022).

Lin, S. R. et al. Machine learning models to evaluate mortality in pediatric patients with pneumonia in the intensive care unit. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 59 (5), 1256–1265 (2024).

Xin, N. et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of community-acquired pneumonia in children (2019 edition) (in Chinese). Clin. Educ. Gen. Pract. 17(9), 771–777 (2019).

Nielsen, D. Tree Boosting with xgboost-Why Does xgboost Win Every Machine Learning Competition? MS Thesis. (NTNU, 2016).

Milcent, K. et al. Use of procalcitonin assays to predict serious bacterial infection in young febrile infants. JAMA Pediatr. 170 (1), 62–69 (2016).

Self, W. H. et al. Procalcitonin as an early marker of the need for invasive respiratory or vasopressor support in adults with community-acquired pneumonia. Chest 150 (4), 819–828 (2016).

Dar, M. I. Role of procalcitonin in predicting clinical outcomes of paediatric patients with respiratory tract infection: A prospective study at government medical college Jammu. Int. J. 7 (4), 117 (2024).

Florin TA, Ambroggio L, Brokamp C, et al. Biomarkers and disease severity in children with community-acquired pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2020;145(6):e20193728.

Zou, M. et al. Lactate dehydrogenase and the severity of adenoviral pneumonia in children: A meta-analysis. Front. Pead. 10, 1059728 (2023).

Patil, S., Narwade, G. & Dhumal, U. The role of initial and follow-up C-reactive protein titer in COVID-19 pneumonia: A single-center study of 1000 cases in a tertiary care setting in India. J. Adv. Lung Health. 3 (1), 17–24 (2023).

Lee, E. & Choi, I. Clinical usefulness of serum lactate dehydrogenase levels in Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in children. Indian J. Pediatr. 89 (10), 1003–1009 (2022).

Wang L, Lu S, Feng Z, et al. The early examination of combined serum and imaging data under flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy as a novel predictor for refractory Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia diagnosis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(50):e9364.

Algebaly, H. A. F. et al. Predictive value of serum lactate dehydrogenase in diagnosis of septic shock in critical pediatric patients: A cross-sectional study. J. Acute Disease. 10 (3), 107–111 (2021).

Martinez-Outschoorn, U. E. et al. Ketones and lactate increase cancer cell stemness, driving recurrence, metastasis and poor clinical outcome in breast cancer: achieving personalized medicine via metabolo-genomics. Cell. Cycle. 10 (8), 1271–1286 (2011).

Peng, S., Li, W. & Ke, W. Association between red blood cell distribution width and all-cause mortality in unselected critically ill patients: analysis of the mimic-iii database. Front. Med. 10, 1152058 (2023).

Nagaraju, V. A. & Taksande, D.. R. A. A prospective observational study of red cell distribution width (RDW) as an outcome marker in critically ill children admitted to a pediatric intensive care unit in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Central India. F1000Research 13, 178 (2024).

Han, T. et al. Analysis of the value of the blood urea nitrogen to albumin ratio as a predictor of mortality in patients with sepsis. J. Inflamm. Res. 1227–1235 (2022).

Sharma, K., Mogensen, K. M. & Robinson, M. K. Pathophysiology of critical illness and role of nutrition. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 34 (1), 12–22 (2019).

Schrier, R. W. Blood Urea nitrogen and serum creatinine: not married in heart failure. Circulation Heart Fail. 1 (1), 2–5 (2008).

Lundberg, S. M. & Lee, S. I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 30 (2017).

Mayampurath, A. et al. Machine learning-based pediatric early warning score: patient outcomes in a pre-versus post-implementation study, 2019–2023. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 26 (2), e146–e154 (2025).

Funding

This study was supported by the Chinese Medical Association International Exchange and Cooperation Foundation (Grant No. Z-2019-41-2405).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ma Xiaoqian and Zhao Wu conceptualized the research and designed the study methodology. Ma Xiaoqian conducted the data analysis and wrote the main manuscript text. Hang Hang, Li Meng, Wu Di, Liu Binbin and Zhu Hengtian collected the data, while Zhao WU and Sun Qi contributed to provided critical revisions to the manuscript. All authors reviewed, edited, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, X., Zhao, W., Sun, Q. et al. Development and validation of a machine learning model for critical progression risk in pediatric severe community-acquired pneumonia. Sci Rep 15, 43011 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23209-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23209-2