Abstract

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) is a rare and often severe genetic disorder that poses significant challenges for affected children and their families. Managing this condition, particularly in terms of wound care and pain relief, creates numerous challenges for parents and can lead to increased parental stress. This stress can adversely affect parents’ quality of life and mental health. Resilience is crucial in helping parents cope with difficulties and improve their psychological well-being. Therefore, this study aims to determine the relationship between parental stress, resilience, and quality of life in parents of children with EB. This study is a descriptive cross-sectional study. One hundred parents (77 mothers and 23 fathers) of children with EB visiting healthcare centers affiliated with Hamadan and Shiraz Universities of Medical Sciences who met the inclusion criteria were enrolled in the study through a census method. Data collection tools included a demographic questionnaire, the Abidin Parenting Stress Index, the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale, and the SF-36 Quality of Life Questionnaire. The parents completed the questionnaires in person. After data collection, statistical analysis was conducted using descriptive and analytical methods with SPSS version 26. The findings indicated that the mean (standard deviation) scores of parental stress in parents of children with EB were 151.28 (± 2.36), the mean (standard deviation) scores of resilience were 49.86 (± 2.63), and the mean (standard deviation) of quality of life was 41.32 (± 2.32). There was a strong inverse correlation between parental stress and resilience (r = -0.89, p < 0.001), a strong inverse correlation between parental stress and quality of life (r = -0.86, p < 0.001), and a strong direct correlation between resilience and quality of life (r = 0.88, p < 0.001). Additionally, a relationship was found between parental stress and demographic variables, including mother’s age, mother’s education, mother’s occupation, father’s education, type of EB, number of affected children, and family income, which accounted for 69.34% of the variations in parental stress. Parents caring for children with EB experienced high levels of stress, moderate resilience, and low quality of life. Furthermore, high parental stress led to decreased resilience and quality of life. Parental stress was closely associated with demographic variables such as the number of affected children, family income, type of EB, mother’s education, mother’s age, father’s education, and mother’s occupation. Accordingly, healthcare professionals can facilitate the adaptation and participation of these parents in caring for children with EB by providing supportive environments, counseling, and education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) is a rare and often severe genetic disorder characterized by mechanical fragility and blistering or erosion of the skin, mucous membranes, and epithelial covering of organs in response to minimal trauma1. In addition to skin blisters, open wounds, and scarring, more severe cases can present with extra-cutaneous manifestations, including gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, and urogenital anomalies2. The prevalence of this disease is approximately 10 per million population, with 950 cases identified in Iran to date3,4. EB comprises over 30 subtypes and is classified into four main categories based on the affected skin layer: simplex, junctional, dystrophic, and kindler syndrome5. These four types vary in severity, but unfortunately, no known cure exists for any of them6. Care objectives focus on blister prevention, wound care, pain relief, early diagnosis, and prevention of external complications2. Simple daily activities such as eating, bathing, walking, and sleeping can cause pain and injury7. Wound care is one of the most significant challenges parents and children face daily, and managing it can be time-consuming and exhausting8,9. Therefore, children and adolescents with this disease are considered to have special healthcare needs10. Parents, as primary caregivers, face numerous challenges5. In addition to raising and nurturing their children, parents must assist with daily activities, provide psychological support, and manage wound care5. Consequently, caring for children with EB not only affects the child’s life but also impacts the parents’ lives, as they experience significant time constraints due to skincare and financial burdens from medical costs, leading to high parental stress5,11.

Parental stress is a psychological response that occurs when parenting tasks are not adequately performed, particularly when parental demands are inconsistent with expectations or when parents cannot meet these demands12. Parental stress has multiple consequences for parents, children, and other family members13. The higher the level of parental stress, the lower the psychological adjustment and quality of life for both parents and their children11. Furthermore, high levels of parental stress may jeopardize treatment effectiveness12. Resilience is one of the factors that help individuals cope with and adapt to difficult and stressful life situations, protecting them from psychological disorders and life difficulties14.

Resilience is a dynamic process in which individuals exhibit positive adaptive behavior in the face of adverse conditions or psychological trauma15. In other words, the individual can withstand life’s stressful challenges and plays a significant role in coping with the stressors associated with the long-term care of a sick family member16. Thus, resilience acts as an important protective factor, especially for families with low levels of social support17. Caregivers with high resilience experience less burden, even when facing high caregiving demands18. Studies have shown that enhancing resilience improves family quality of life17.

According to the World Health Organization, quality of life is defined as individuals’ perception of their position in life within the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns19. Quality of life results from a subjective evaluation, and individuals are best suited to judge it themselves20. Parents of children with EB have a lower quality of life compared to parents of healthy children11. Research results in this area indicate that assessing quality of life in chronic diseases is important since quality of life is one of the main indicators for measuring the success of therapeutic outcomes in chronic illnesses21. Therefore, special attention to the health status of parents of these children seems essential and can contribute to implementing family support programs to reduce family burden and improve their quality of life6. For parents to fully care for and support their children, they must have mental peace22. Given the importance of parental stress, resilience, and quality of life in parents of children with EB, no studies have been conducted in Iran to date. This study aims to examine the relationship between parental stress, resilience, and quality of life in parents of children with EB. In this regard, Bruckner et al. (2020) stated in their study that caring for this condition is very time-consuming and exhausting, imposing a significant caregiving burden on patients, caregivers, and families, affecting their education, employment, and daily lives2. Moreover, covering wound care costs for these patients is challenging and increases the caregiving burden. The demanding nature of care and high caregiving burden negatively impact the quality of life of this group. In their study, Wen et al. (2020) demonstrated that caring for children with genetic or rare diseases can impact the mental health of families. The use of ineffective coping mechanisms by parents to manage stress is linked to higher levels of parental stress and symptoms of depression23. Additionally, Choghani et al. (2020) noted that caring for patients with EB imposes a significant caregiving burden on caregivers, especially families as the primary caregivers, severely affecting their quality of life24. In this context, Mauritz et al. (2021) indicated in their study that coping strategies such as acceptance and avoidance improve the quality of life and emotional-social functioning of children with EB and their parents25.

Therefore, it is necessary to examine the stress, resilience, and quality of life of parents of children with EB. So, the present study was conducted with the study aimed of investigating parental stress, resilience, and quality of life in parents of children with epidermolysis bullosa and exploring the correlation between parental stress, resilience, and quality of life. Also, identifying factors that predict parental stress in these parents.

Methods

Study design and setting

This descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted in healthcare centers affiliated with with Hamadan and Shiraz Universities of Medical Sciences from September 2022 to November 2024. This study was conducted based on the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology statement (STROBE).

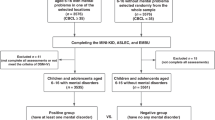

Participants and sampling

Following ethical approval, the researcher visited healthcare centers associated with Hamadan and Shiraz Universities of Medical Sciences. A list of families with children diagnosed with epidermolysis bullosa who met the inclusion criteria was compiled. Subsequently, parents were contacted, and those interested in participating were invited to participate in the study. Ultimately, one hundred and eight parents were identified through a census method and invited to participate in the study. Inclusion criteria included parents having a child diagnosed with EP based on criteria and the opinion of a specialist physician, absence of intellectual disability, mental disorders, or other known physical illnesses in parents as reported by them, absence of intellectual disability, mental disorders, or other known physical illnesses in the child based on medical records, informed consent to participate in the study, parents’ literacy in reading and writing. Exclusion criteria included not referring to relevant questionnaires and not responding to more than 20% of the questions. Out of the 108 parents, 100 completed and returned the questionnaires, resulting in a response rate of 92.59%. The primary reason for non-response was a lack of time.

Questionnaires

Demographic questionnaire

This questionnaire included information such as the age and gender of parents, parental education, parental occupation, family income, parental health conditions, age and gender of the child, number of children, number of sick children, number of children with epidermolysis bullosa, living situation with parents, number of hospitalizations, and type of epidermolysis bullosa.

Parenting stress index

The short form of the Parenting Stress Index, developed by Abidin in 1995, provides a comprehensive assessment of overall parental stress, including subscales for parental distress, dysfunctional parent-child interactions, and child behavior problems. This study utilized the overall parenting stress score, which consists of 36 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1: strongly disagree to 5: strongly agree). The total score ranges from 36 to 180, with higher scores indicating higher parental stress. The validity and reliability of this questionnaire were assessed in a study by Fadaei et al. (2010), showing adequate content and construct validity, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.9026. The current study also evaluated the validity and reliability, yielding a Cronbach’s alpha 0.91.

Connor-Davidson resilience scale

The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale was developed in 2003 through a review of research literature from 1979 to 1991 in the field of resilience. This questionnaire consists of 25 items, and its response scale is a 5-point Likert scale ranging from zero (strongly disagree) to four (strongly agree). The minimum score is zero, and the maximum score is 100. A score above 60 indicates higher resilience. Connor and Davidson conducted an internal consistency analysis for this tool, resulting in a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89, with item-total correlations ranging from 0.30 to 0.70. Mohammadi adapted this questionnaire for use in Iran, administering the scale to 248 individuals, achieving a reliability score of 0.89 through internal consistency measured by Cronbach’s alpha. In the study by Haq Ranjbar and colleagues, Cronbach’s alpha for this tool was calculated at 0.84. The validity of this scale was examined in the study by Basharat et al. (2007), showing that both face and content validity were adequate27. The validity and reliability of this questionnaire were also assessed in the present study, yielding a value of 0.88.

SF-36 quality of life questionnaire

The 36-item SF-36 quality of life questionnaire was designed by Ware and Sherbourne in 1992 in the USA. It consists of 8 subscales, each containing 2 to 10 items. The subscales include physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health, role limitations due to emotional problems, energy/fatigue, emotional well-being, social functioning, pain, and general health. Combining these subscales yields two overall measures: physical health and mental health. The score range varies between 0 and 100, and a higher score represents a better quality of life. A lower score indicates a lower quality of life, and vice versa. In Iran, this questionnaire was translated into Persian using a back-translation method by Samsamipour et al., who reported that, except for the energy/fatigue subscale (alpha = 0.65), all other subscales had acceptable reliability (0.77 to 0.90). The validity was established through convergent validity with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.58 to 0.9928. In the current study, the reliability was found to be 0.93.

Statistical methods

The collected data were analyzed using SPSS version 26. Descriptive statistics (frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation) were employed. Independent t-tests and ANOVA were utilized to examine the relationship between parental stress and demographic information. A significance level of p < 0.05 was set. Subsequently, demographic information, resilience, and quality of life (p < 0.25) were entered into a multiple linear regression model with a backward strategy. Additionally, the effects of moderating variables on the relationships between parental stress and demographic information, resilience, and quality of life were assessed by comparing the results of simple and multiple linear regression. Before conducting multiple linear regression, assumptions including normality of data, homogeneity of variance, and independence of residuals were evaluated.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Committee of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences approved the study protocol. Researchers began by introducing themselves, outlining the research objectives, and ensuring participants kept their information confidential. Participants were given the option to withdraw from the study at any point. Subsequently, all participants provided written consent after receiving detailed information about the study.

Results

Demographic information in parents of children with epidermolysis Bullosa

100 parents (77 mothers and 23 fathers) participated in the study. The age range for mothers was 21 to 41 years, with a mean age of 25.47 (± 2.74 years), while fathers had an age range of 23 to 46 years, with a mean age of 32.67 (± 2.29 years). Most mothers had a high school education (46.75%), and most were housewives (38.96%). Similarly, most fathers had a high school education (65.21%) and were self-employed (78.26%). Most parents had two children (58%) and one child with epidermolysis bullosa (88%). Most children lived with both parents (72%), and the family income for the majority exceeded 6 million (71%). The findings indicated significant relationships between parenting stress and several demographic variables, including the number of children with epidermolysis bullosa, household income, type of epidermolysis bullosa, parental education, mother’s age, and occupation. Specifically, employed mothers, parents with higher education, and those with lower income reported higher levels of parenting stress. (Table 1).

Parenting Stress, Resilience, and quality of life in parents of children with epidermolysis Bullosa

In this study, parents of children with epidermolysis bullosa reported a mean parenting stress score of 151.28 (± 2.36), indicating high levels of stress. The mean resilience score was 49.86 (± 2.36), reflecting moderate resilience, while the mean quality of life score was 41.32 (± 2.32), indicating low quality of life. (Table 2)

The relationship between parenting Stress, Resilience, and quality of life in parents of children with epidermolysis Bullosa

The results showed a strong inverse correlation between parenting stress and resilience (r = -0.89, p < 0.001) as well as between parenting stress and quality of life (r = -0.86, p < 0.001) and as well as between resilience and quality of life (r = -0.88, p < 0.001).

Factors predicting parenting stress in parents of children with epidermolysis Bullosa

Variables such as resilience, quality of life, mother’s age, mother’s education, mother’s occupation, father’s education, type of epidermolysis bullosa, number of children with epidermolysis bullosa, and household income (p < 0.25) were entered into a multiple linear regression model with a backward strategy. These variables accounted for approximately 69.34% of the variance in parenting stress among parents of children with epidermolysis bullosa. (Table 3)

Discussion

This study demonstrated that parents of children with epidermolysis bullosa reported high levels of parenting stress, moderate resilience, and low quality of life. There was a strong inverse correlation between parenting stress and both resilience and quality of life. Additionally, parenting stress was associated with variables such as resilience, quality of life, mother’s age, mother’s education, mother’s occupation, father’s education, type of epidermolysis bullosa, number of affected children, and household income. These variables explained approximately 69.34% of the variance in parenting stress.

Although several studies have explored the psycholbasogical challenges faced by parents of children with epidermolysis bullosa, no studies have specifically examined the relationship between parenting stress, resilience, quality of life, and demographic information in this population. Thus, researchers referenced other studies that have separately analyzed parenting stress, resilience, and quality of life.

Parents of children with EB in this study reported a high level of parenting stress. This stress level is attributable to the unique characteristics of epidermolysis bullosa and the complex, exhausting care required for these children, significantly burdening parents. Various studies have documented these challenges and stresses associated with caring for children with epidermolysis bullosa. For instance, Bruckner et al. (2020) noted that children with this condition require continuous care, directly leading to increased parenting stress2. Similarly, Daae et al. (2024) highlighted that parents face challenges in balancing personal life with caregiving responsibilities, often exceeding their capabilities, significantly increasing their psychological pressure and stress5. Wu et al. (2020) also emphasized the intense stress and caregiving burden experienced by parents29. Furthermore, Khalili et al. (2025) found that the pressures associated with epidermolysis bullosa affect parents physically, emotionally, socially, and financially, diminishing their ability to fulfill their responsibilities and exacerbating parenting stress30. Although previous studies did not directly measure parenting stress, their findings align with our study, indicating that caregiving for these children is exhausting and raises parents’ expectations of themselves, potentially exceeding their capabilities, leading to high parenting stress.

Resilience among parents in this study was moderate. While no studies are available to researchers that have examined resilience in parents of children with epidermolysis bullosa.Therefore, studies that have examined resilience in parents of children with chronic illnesses were discussed and reviewed. In a study conducted by Qiu et al. (2021), it was reported that the resilience of families with children suffering from chronic illnesses was lower than the resilience of parents of healthy children. The average resilience in the aforementioned study was lower than the results of our study31, which may be attributed to the use of different tools and the cultural context differing from that of Iran. Additionally, the target group in this study may include patients with illnesses different from EB, which could impact their level of resilience. Conversely, Cici et al. (2024) demonstrated in their study that the resilience of families with children suffering from chronic illnesses is significantly higher than the present research results32. This discrepancy may be due to various reasons, including the differing socio-cultural context of Iran or a broader target group encompassing all types of chronic illnesses. The results of these studies indicate that the resilience of parents of children with chronic illnesses, including EB, is influenced by various cultural, social, and disease-related factors, highlighting the need for further research in different cultural and geographical contexts.

Based on the results of the current study, the quality of life for parents of children with EB was low. same studies indicate that EB has profound effects on the patient and negatively impacts the family, especially the parents, directly affecting their quality of life. Choghani et al. (2021) reported that the quality of life for families of individuals with EB was low33. Although the present study aligns with this study, the average quality of life score is lower than that of the current study, which may be because the previous study considered all individuals with EB across all age ranges. It is evident that the age of children with EB, their family members, becomes fatigued and worn out, leading to a decline in their quality of life. Furthermore, a different tool was used in the earlier study, and all family members could participate, which could account for the differing scores. On the other hand, they reported that EB, due to high treatment costs, job limitations, and disruptions in parents’ social relationships, creates numerous social and economic challenges for parents, directly impacting their quality of life.

According to the results of the present study, parental stress has a strong negative correlation with resilience34. Although few studies have examined the relationship between parental stress and the resilience of these parents, the topic has been discussed in relation to other illnesses and disorders. Cerezuela et al. (2021) found a significant negative correlation between parental stress and the resilience of parents of children with autism and Down syndrome. They also observed that the more resilient parents felt against adversities, the less stress they experienced35. This finding is consistent with the present study, indicating that increased resilience can lead to reduced parental stress. Zhao et al. (2021) also demonstrated a significant relationship between resilience and parental stress, suggesting that enhancing resilience leads to a decrease in parental stress36. These findings clearly show that resilience, as a protective variable, can mitigate the stresses associated with caring for children with specific illnesses. Wen et al. (2020) further stated that parents who employ ineffective coping strategies experience higher parental stress. However, they noted that the use of coping strategies does not necessarily have a significant impact on reducing depressive symptoms or parental stress23. This point underscores the importance of using appropriate and effective coping strategies, which are highlighted in the present study as influential factors in parental resilience.

The studies mentioned above, despite focusing on different populations, all highlight common themes such as chronicity, burdensome caregiving responsibilities, reliance on parents for daily needs, and the disruption of parents’ lives, which align with the findings of our study. Our research indicates a strong negative correlation between parental stress and quality of life, emphasizing the significant impact that psychological and emotional factors like parental stress can have on the well-being of parents. The study by Datta et al. (2021), focusing on parents of children with chronic dermatoses, indicates that these parents face high levels of stress. Chronic skin diseases often require special care, and the children in this group frequently need more attention and support due to physical and social limitations. This situation increases psychological and physical pressures on parents. Furthermore, the results of this study show that as parental stress increases, parents’ quality of life declines37. In the study by Staunton et al. (2023), which focused on parents of children with intellectual disabilities, the findings indicated a moderate negative correlation between parental stress and parents’ quality of life15. Although the present study was conducted in a different target group, it shares similarities regarding chronic conditions and the dependency of these children on their parents. Dijkstra et al. (2024) demonstrated in their study that parents of children struggling with autism spectrum disorders typically face high levels of parental stress, which can negatively impact their mental health, quality of life, and family relationships. Additionally, this study showed that reducing parental stress and providing appropriate support can improve the quality of life for parents38. Although the present study’s findings align with our study, they were conducted in a different target group. Based on the current research results, parental stress was associated with maternal age, maternal education, maternal occupation, paternal education, type of EB, number of children with EB, and family income. In a study conducted by Dellve et al. (2006), mothers, especially single mothers and those with more than one sick child, reported higher parental stress compared to fathers39. This difference is particularly due to mothers’ greater responsibilities in caring for their children, which can impose additional pressure on them. Besides gender, the education level of parents can also significantly impact the level of parental stress. Parents with higher education may often have higher expectations for themselves and their children, which can lead to increased stress.

Furthermore, the level of education a parent has can impact the amount of social support and resources available to them, thereby affecting the level of parental stress. Scheibner et al. (2024) revealed that as mothers’ education levels rose, so did their parental stress40. This could be attributed to heightened self-expectations and the challenges of juggling work and personal life. Age has also been recognized in numerous studies as a significant factor in influencing parental stress levels. Younger parents may experience more stress due to a lack of experience or an inability to cope with various daily life problems. Conversely, older parents may feel more psychological pressure due to health concerns or an inability to perform certain tasks. Fang et al. (2024) showed that both younger and older parents report higher stress levels, which may be due to a lack of experience or age-related concerns41. Similarly, in the study by Hj Lee et al. (2023), it was observed that mothers of children with atopic dermatitis experience higher parental stress compared to fathers and mothers of healthy children. These mothers face not only stress related to their child’s illness but also a lower quality of life, which can lead to increased psychological pressure42.

Limitations

One of the most significant limitations of the present study is the low response rate of questionnaires from parents. This issue is likely due to the overwhelming demands and time-consuming nature of caregiving for children with EB. Additionally, the rarity of this condition extended the sampling process. Given these limitations, it is recommended that future research assess parenting stress, resilience, and quality of life in diverse communities with larger sample sizes to obtain a more accurate representation of these parents’ situations. Such information could assist managers and policymakers in designing and implementing comprehensive support programs for the parents of these children based on the findings.

Conclusions

In this study, parenting stress among parents of children with EB was reported to be high. Factors such as maternal resilience, quality of life, maternal age, maternal education, maternal occupation, paternal education, type of EB, number of children affected by the disease, and household income significantly influenced the parenting stress experienced by these parents. Consequently, pediatric nurses and policymakers in health and treatment organizations can facilitate the adaptation and engagement of these parents in caring for children with EB by providing supportive environments, counseling, and education.

Data availability

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Salamon, G., Strobl, S., Matschnig, M. S. & Diem, A. The physical, emotional, social, and functional dimensions of epidermolysis bullosa. An interview study on burdens and helpful aspects from a patients’ perspective. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 20, 3 (2025).

Bruckner, A. L. et al. The challenges of living with and managing epidermolysis bullosa: insights from patients and caregivers. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 15, 1–14 (2020).

Mohammadi, F., Masoumi, S. Z., Oshvandi, K., Sobhan, M. R. & Bijani, M. Parents’ perception of challenges of caring of children with epidermolysis bullosa: a qualitative study. BMC Res. Notes. 17, 302 (2024).

Khanna, D. & Bardhan, A. In StatPearls [Internet] (StatPearls Publishing, 2024).

Daae, E., Feragen, K. B., Naerland, T. & von der Lippe, C. When care hurts: parents’ experiences of caring for a child with epidermolysis Bullosa. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 19, 492 (2024).

Alheggi, A., Alfahhad, A., Bukhari, A. & Bodemer, C. Exploring the impact of epidermolysis Bullosa on parents and caregivers: A Cross-Cultural validation of the epidermolysis Bullosa burden of disease questionnaire. Clinical Cosmet. Invest. Dermatology 17, 1027–1032 (2024).

Asimakopoulou, E. et al. Epidermolysis bullosa: A case study in Cyprus and the nursing care plan. Int. J. Nurs. Knowl. 33, 312–320 (2022).

Jeffs, E. et al. Costs of UK community care for individuals with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa: Findings of the Prospective Epidermolysis Bullosa Longitudinal Evaluation Study. Skin Health Dis. 4, ski2. 314 (2024).

Retrosi, C. et al. Multidisciplinary care for patients with epidermolysis Bullosa from birth to adolescence: experience of one Italian reference center. Ital. J. Pediatr. 48, 58 (2022).

Barbosa, N. G. et al. School inclusion of children and adolescents with epidermolysis bullosa: the mothers’ perspective. Revista Da Escola De Enfermagem Da USP. 56, e20220271 (2022).

Mauritz, P. J., Bolling, M., Duipmans, J. C. & Hagedoorn, M. Patients’ and parents’ experiences during wound care of epidermolysis Bullosa from a dyadic perspective: a survey study. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 17, 313. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-022-02462-y (2022).

Holly, L. E. et al. Evidence-Base update for parenting stress measures in clinical samples. J. Clin. child. Adolesc. Psychology: Official J. Soc. Clin. Child. Adolesc. Psychol. Am. Psychol. Association Div. 53 48, 685–705. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2019.1639515 (2019).

Thompson, P. Gender Differences of Parenting Stress during Child Custody Evaluations as Measured by the Parenting Stress Index (Alliant International University, 2022).

Rezaeefard, A. The role of resilience and parenting styles in predicting parental stress of mothers of students with ADHD/Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J. Sch. Psychol. 10, 73–85 (2022).

Staunton, E., Kehoe, C. & Sharkey, L. Families under pressure: stress and quality of life in parents of children with an intellectual disability. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 40, 192–199 (2023).

rostami ardalan, a., ahmadian, h. & moradi, m. The effect of resilience skills on life expectancy and stress of mothers with mentally retarded children in Kamyaran. Zanko J. Med. Sci. 20, 35–45 (2019).

Hassanein, E. E. A., Adawi, T. R. & Johnson, E. S. Social support, resilience, and quality of life for families with children with intellectual disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 112, 103910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2021.103910 (2021).

Behzadi, H., Borimnejad, L., Mardani Hamoleh, M. & Haghani, S. Effect of an online educational intervention on resilience and care burden of the parents of children with cancer. Iran. J. Nurs. 35, 118–133. https://doi.org/10.32598/ijn.35.2.247.4 (2022).

Bobes, J., Garcia-Portilla, M. P., Bascaran, M. T., Saiz, P. A. & Bousoño, M. Quality of life in schizophrenic patients. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 9, 215–226. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2007.9.2/jbobes (2007).

Karimian, B., Karimi Afshar, E., The relationship of resilience with quality of life and life expectancy of the mothers of deaf children. Nurs. Midwifery J. 19, 888–896, https://doi.org/10.52547/unmf.19.11.888 (2022).

Begjani, J. et al. The effect of self care education based on orem’s theory on quality of life of parents of children with nephrotic syndrome. Iranian J. Nurs. Res. (IJNR) Original Article 17, 140–149 (2022).

fallah mehrjardi, M. & Barkhordari sharifabad, M. Comparison of parental anxiety before surgery your children. Iranian J. Pediatr. Nurs. 7, 80–86 (2020).

Wen, C. C. & Chu, S. Y. Parenting stress and depressive symptoms in the family caregivers of children with genetic or rare diseases: the mediation effects of coping strategies and self-esteem. Ci Ji Yi Xue Za zhi = Tzu-chi Med. J. 32, 181–185. https://doi.org/10.4103/tcmj.tcmj_35_19 (2020).

Chogani, F., Parvizi, M. M., Murrell, D. F. & Handjani, F. Assessing the quality of life in the families of patients with epidermolysis bullosa: the mothers as main caregivers. Int. J. Women’s Dermatology. 7, 721–726 (2021).

Mauritz, P. J., Bolling, M., Duipmans, J. C. & Hagedoorn, M. The relationship between quality of life and coping strategies of children with EB and their parents. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 16, 53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-021-01702-x (2021).

Fadaei Z, Dehghani M, Tahmasian K, Farhadei M. Investigating reliability, validity and factor structure of parenting stress- short form in mother`s of 7–12 year-old children. J. Res. Behav. Sci. 8(2), 81–91 (2010).

Besharat, M. A. Resilience, vulnerability, and mental health. JPS 6(24), 373–383 (2008).

Samsamipour, M. et al. Health-related quality of life of young adult with beta-Thalassemia major. Sci. J. Nurs. Midwifery Paramedical Fac. 4, 66–75 (2019).

Wu, Y. H., Sun, F. K. & Lee, P. Y. Family caregivers’ lived experiences of caring for epidermolysis Bullosa patients: A phenomenological study. J. Clin. Nurs. 29, 1552–1560. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15209 (2020).

Khalili, H., Moonaghi, K., Kianifar, H. R. & Manzari, Z. S. Parental caregiving experiences in epidermolysis bullosa: A phenomenological study. Int. J. Community Based Nurs. Midwifery. https://doi.org/10.30476/ijcbnm.2025.102011.2466 (2025). -.

Qiu, Y. et al. Family Resilience, parenting styles and psychosocial adjustment of children with chronic illness: A Cross-Sectional study. Front. Psychiatry. 12, 646421. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.646421 (2021).

Cici, A. M. & Özdemir, F. K. Examining resilience and burnout in parents of children with chronic disease. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 75, e176–e183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2024.01.011 (2024).

Chogani, F., Parvizi, M. M., Murrell, D. F. & Handjani, F. Assessing the quality of life in the families of patients with epidermolysis bullosa: the mothers as main caregivers. Int. J. Women’s Dermatology. 7, 721–726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.08.007 (2021).

Manomy, P. et al. Impact of a psychodermatological education package on the subjective distress, family burden, and quality of life among the primary caregivers of children affected with epidermolysis Bullosa. Indian Dermatology Online J. 12, 276–280 (2021).

Pastor-Cerezuela, G., Fernández-Andrés, M. I., Pérez-Molina, D. & Tijeras-Iborra, A. Parental stress and resilience in autism spectrum disorder and down syndrome. J. Fam. Issues. 42, 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X20910192 (2020).

Zhao, M., Fu, W. & Ai, J. The mediating role of social support in the relationship between parenting stress and resilience among Chinese parents of children with disability. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 51, 3412–3422 (2021).

Datta, D., Sarkar, R. & Podder, I. Parental Stress and Quality of Life in Chronic Childhood Dermatoses: A Review. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 14, S19-S23 (2021).

Dijkstra-de Neijs, L., Boeke, D. B., van Berckelaer-Onnes, I. A., Swaab, H. & Ester, W. A. Parental stress and quality of life in parents of young children with autism. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-024-01693-3 (2024).

Dellve, L., Samuelsson, L., Tallborn, A., Fasth, A. & Hallberg, L. R. Stress and well-being among parents of children with rare diseases: a prospective intervention study. J. Adv. Nurs. 53, 392–402. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03736.x (2006).

Scheibner, M. et al. The impact of demographic characteristics on parenting stress among parents of children with disabilities: a cross-sectional study. Children 11, 239 (2024).

Fang, Y. et al. Parent, child, and situational factors associated with parenting stress: a systematic review. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 33, 1687–1705 (2024).

Lee, H. J. et al. Psychological stress in parents of children with atopic dermatitis: a cross-sectional study from the Korea National health and nutrition examination survey. Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 103, 2242 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The present article is the outcome of a research project registered at Hamadan University of Medical Sciences. The researchers express their gratitude to the authorities at Hamadan University’s School of Nursing and Midwifery, as well as to the participants and other individuals who provided valuable cooperation.

Funding

This research was not funded by any specific grants from public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FM, ME, FCH, SKH, MRS, and MMP were involved in the conception and design of the study. They are responsible for data collection. Then, FM and SKH analyzed the data. FM, ME, FCH, SKH, MRS, and MMP drafted the primary manuscript, and FM, ME, FCH, SKH, MRS, and MMP revised and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The institutional review board of the medical universities located in the west of Iran provided ethics approval (IR.UMSHA.REC.1402.387). All methods were performed under the relevant guidelines and regulations, and all the research methods met the ethical guidelines described in the Declaration of Helsinki. At the start of the study, the researcher introduced herself and outlined the study’s objectives. Informed consent to participate was obtained from the parents. They were assured that all information would be kept confidential. The researcher also made it clear that parents could withdraw from the study at any point without facing any consequences.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Esmaeili, M., Mohammadi, F., Cheragi, F. et al. The relationship between parental stress, resilience, and quality of life in parents of children with epidermolysis bullosa. Sci Rep 15, 39683 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23223-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23223-4