Abstract

Non-fired tile has numerous functional, economic, and environmental benefits. It can be considered a viable alternative to conventionally fired ceramic tiles. In this study, Ceiba pentandra fibre and Phosphogypsum (PG) have been used in the production of non-fired tile. PG is a by-product and is obtained from the phosphate industry. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) has been carried out to assess the environmental impacts associated with the production and use of these PG-based tiles. Physico-chemical properties of both PG and Ceiba pentandra fibres were analysed to assess the suitability of these materials in sustainable tile production. The strength characteristics of the tiles, made by combining PG and Ceiba pentandra fibres, were experimentally tested to assess their mechanical properties, particularly their bending stress. The results indicated that the tiles reinforced with 6 wt% Ceiba pentandra fibers exhibit a higher bending stress of 16.6 MPa under the pressing load of 15 MPa. Besides, the epitome fibre and water content were identified through experimental investigations, and this data is vital for optimising the manufacturing process to ensure the best performance of the eco-friendly tiles. The findings emphasised that these materials can be used as a novel and sustainable alternative in the construction industry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the present era, agriculture has become a prime focus in all countries owing to global population growth and demand for increased food production. Currently, large quantities of chemical fertilisers are used to enhance soil nutrient content. Especially, phosphate-based fertilisers play a vital role in replenishing the soil phosphorus levels. Phosphogypsum (PG), a by-product from the phosphate fertilizer industry, is produced in vast quantities worldwide, approximately 250 to 300 million tons annually. Its generation is geographically concentrated, with China, the United States, India, Morocco, Tunisia, and Brazil identified as among the leading producers owing to their extensive phosphate fertilizer industries. Yet, only 10–15% of this waste is reused in limited applications such as gypsum plaster, wallboards, cement retarders, agricultural soil amendment, road base materials, and lightweight aggregates, leaving a massive volume to be either landfilled or stockpiled, often causing environmental and health hazards due to its mildly radioactive content and high sulfate concentration5,6,7. The cumulative global stockpiles are estimated to exceed 70–80 million tonnes5. Its proper disposal remains a major challenge, especially for fertilizer industries that face increasing regulatory pressures and land scarcity9,11. Despite the concerns, PG’s chemical composition, primarily calcium sulfate dihydrate (CaSO₄·2 H₂O), and its low cost or near-zero procurement value make it a viable candidate for sustainable reuse in construction applications2,3,79,80,81. The reuse of PG in building materials such as non-fired tiles, plasters, wallboards, and gypsum-based blocks not only diverts waste from landfills but also significantly lowers energy consumption and CO₂ emissions by replacing high-energy clinker or avoiding firing processes altogether1,8,27,82. Furthermore, PG-based products have been validated to meet health and safety standards concerning radioactivity, which supports their broader industrial application27,57,83,84. As demonstrated in this study, the integration of PG into non-fired tile production, especially when reinforced with natural fibers like Ceiba pentandra, enhances the mechanical and thermal properties of the final product while also supporting a circular economy approach by valorizing industrial waste into affordable, durable, and eco-efficient construction materials6,21,39,85.

However, only 10–15% of this by-product is reused for different purposes. The proper disposal of PG poses a critical challenge for the industries10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18, as it requires extensive dumping sites and environmentally compatible methods. Open dumping is particularly problematic, leading to significant environmental and health risks19,20,21,22,23,24,25,31. PG contains naturally occurring radioactive elements, including U-234, Ra-226, U-238, and Pb-210. Nevertheless, the concentrations of these elements in PG are generally below the thresholds set by the EPA, allowing for its safe utilization26,27,28,29,30.

Research indicates that utilizing PG in the production of building materials poses no health risks to humans. Studies, such as those by Sun et al. (2017)27, have assessed the effect of PG on the properties of cementitious pastes and found no significant health concerns related to its radioactive content. Overall, while the disposal of PG remains a pressing issue, its potential for safe reuse in construction and other industries is being increasingly recognised. Enables low-energy materials, such as non-fired tiles and blocks, avoiding the need for high-temperature processing. PG is obtainable at least or no cost; which reduces the overall cost of materials32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41.

However, the tensile strength of the composite should be given more attention during the product development stage. Natural fibers impart good tensile strength to composites. They can be added to construction materials such as non-fired tiles, plasters, and bio-concretes to enhance performance. Natural fibers like hemp, jute, and sisal are universally unified into building materials to improve their performance42,43,44. In this study, natural fiber obtained from the Ceiba pentandra tree is used to enhance the tensile strength of PG-based non-fired tiles. It has several advantages, such as good thermal insulation, light weight, and buoyancy. Besides, the air-filled hollow structure of the fiber plays a key role in enhancing the workability of concrete45,46,47,48.

The inclusion of Ceiba pentandra fiber in the composition of non-fired tiles significantly contributes to their mechanical strength and durability through micro-reinforcement mechanisms. These natural fibers, derived from the kapok tree, are unique for their lightweight, high tensile strength, and hollow, buoyant structure. Ceiba pentandra, commonly referred to as kapok, is a tropical tree whose fibers have gained considerable attention due to their distinctive structural and mechanical properties. These fibers are lightweight, buoyant, and possess a hollow lumen structure, which significantly contributes to their low density (1.19 g/cm³) and excellent thermal insulation properties43,46. In terms of mechanical characteristics, Ceiba fibers have a tensile strength of approximately 2.74 GPa and a Young’s modulus of 59.1 GPa, making them suitable for reinforcing composites, especially for non-structural applications where toughness and energy absorption are critical44. Several studies have emphasized the bridging role of these fibers in crack propagation zones, enhancing flexural strength and impact resistance in composite materials42,48. Furthermore, the environmental appeal of Ceiba fiber lies in its biodegradability, abundance in tropical regions, and minimal processing requirements, making it an attractive alternative to synthetic fibers14,77. From an LCA perspective, Martijn et al. (2017)14 showed that Ceiba-based materials can exhibit a significantly reduced environmental footprint, contingent on local farming and processing methods. Their high cellulose and low lignin content facilitate easy integration into cementitious and gypsum-based matrices43, while their waxy outer surface improves resistance to moisture absorption—an essential factor in building applications. These findings collectively reinforce the applicability of Ceiba pentandra as a viable and sustainable reinforcing agent in green construction materials.

In tile matrix, Ceiba fibers act as distributed micro-reinforcements within binder system49,50,51. These fibers help in bridging micro-cracks that initiate under stress, thus preventing their propagation and delaying failure. This bridging effect enhances the tile’s flexural behaviour, allowing it to bend slightly rather than fail abruptly. Additionally, the lightweight characteristic of Ceiba fiber reduces the overall density of the tile, making it more suitable for applications where weight reduction is crucial without compromising on structural integrity. This can lead to ease in handling, reduced transportation cost, and lower embodied energy in construction materials.

Currently, ceramic tiles are widely used, and they attain high strength through the sintering process. However, abundant quantities of gases are emitted during sintering, contributing to air pollution55,56. While ceramic tile production is indispensable, it poses several environmental challenges. Many researchers have indicated that PG can be used in building materials without any health risks57,58. Previously, several researchers evaluated PG’s effect on the rheology of cementitious pastes and found no notable health risks associated with its radioactive content59.

Overall, the disposal of PG remains a pressing issue. Therefore, its potential for safe reuse in construction and other industries is being increasingly recognized60,61,62,63. Hence, PG is used in the pressing hydration process to produce non-fired tile according to standards64,65,66,67. The Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) methodology (ISO, 2006) is proposed to estimate the environmental impact of PG tiles throughout their lifespan and compare it with that of conventional tiles.

The main goal of this research is to replace energy-intensive kiln firing with renewable natural fibres to turn waste PG into a value-added product for sustainable development. By utilising PG and Ceiba pentandra fibre, this innovative technique for making non-fired tiles helps cut down on waste disposal and makes use of a by-product that would otherwise be harmful to the environment. Furthermore, using these materials lessens reliance on raw minerals, cuts waste, and provides a substitute for energy-intensive production methods, all of which contribute to a lower carbon footprint and meet SDGs 7, 11, and 12.

Materials and test details

Production of PG tile with Ceiba pentandra fiber is a pioneering approach. By and large, glass fibre is used to expand the tensile strength. Production of PG tile using ceiba pentandra fibre comprises 80–90% less greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions than using glass fibre52,53. It is a novel approach; hence, the existing literature on LCA studies with respect to PG tile is limited. So, the scope has been constrained to study the environmental impact of conventional and Ceiba pentandra fibre-added PG tile. The study was categorized and executed in two phases. Phase I consists of the strong features. Phase II consists of the life cycle assessment of Ceiba pentandra fibre added PG tile and the conventional tile.

Constituent materials

Figure 1 shows XRD details of PG. The percentage proportion of constituents of PG is shown in Table 1.

Based on Fig. 1, it is evident that the significant constituent available in PG is CaSO4·2H2O. Ceiba pentandra fibre was used to elevate the tensile strength of the tile. The crystalline peaks typically appear at well-defined 2θ angles, confirming a fine crystalline matrix with limited amorphous content. CaHPO4.2H2O appearance may be due to partial dehydration during processing. The less intense peaks indicate the smaller crystal size and less ordered crystalline structure. The proportions and properties of various constituents of Ceiba pentandra fibre are provided in Tables 2 and 3.

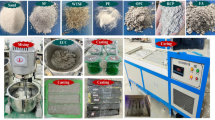

Preparation of Ceiba Pentandra fiber-added PG-based non-fired tile

The pressing hydration method was preferred to form the ceiba pentandra fibre-supplemented PG tile. 5, 10, and 15 MPa of loading pressure have been applied for the preparation of the tile. The following step-by-step procedure can be followed in the production process of tile:

Step 1

Alkaline Treatment with NaOH.

-

Prepare a sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution at a molar ratio of 1.5 with respect to the carbon content, and Mix NaOH with PG thoroughly.

-

Heat the mixture at 100 °C for 30 min to activate the mineral transformation and avoid CO₂ release. Allow the treated mixture to cool before further processing.

Step 2

Preparation of Tile Mixes.

-

Measure 11 kg of treated PG per tile and choose a water-to-binder (w/b) ratio between 10% and 25%. Prepare different batches with varying ratios to study the effect of water content.

Step 3

Addition of Ceiba Pentandra Fiber.

-

Prepare the fiber and incorporate fiber into the PG mix at varying levels from 0% to 12% by weight of PG.

Step 4

Pressing the Samples.

-

Place the prepared mix into moulds of dimensions 750 mm × 750 mm × 10 mm. Apply a uniaxial pressure of 5, 10, or 15 MPa using a hydraulic press. Maintain the pressure for 3 min. This step transforms PG into dihydrate form (CaSO₄·2 H₂O) and improves the tile’s structural integrity (Fig. 2).

PG tile production process is a low-energy, eco-conscious, and technically scalable method that transforms industrial waste into a viable construction material. It holds strong potential for mass adoption in sustainable building practices, especially in developing regions where material cost, availability, and environmental compliance are critical drivers, and it can be achieved using simple hydraulic tile press machines.

The PG tile production method developed in this study is inherently low-energy, utilizing a pressing hydration process that avoids the high-temperature sintering required for traditional ceramic tiles. This attribute, coupled with the use of industrial by-products like PG and naturally renewable Ceiba pentandra fiber, positions it as a highly sustainable and economically viable alternative. The process is particularly suitable for deployment in regions near phosphate fertilizer industries where PG waste is abundantly available and poses disposal challenges.

Mix ratios and test methods

Bending stress was evaluated as per IS 13,630 (part 6): 2006. Two series of mixes were used to prepare tile samples of size 750 × 750 × 10 mm. The First Series of mixes consist of PG tile without fibre (PGT), and the second series consists of PG tile with fibre (PGTF). Mix ratios of the PGT and PGTF series are mentioned in Tables 4 and 5, respectively.

Mix ratios

The detailed mix proportions of the PGT series and the PGTF series are shown in Tables 3 and 4.

Life cycle assessment (LCA)

LCA is an eminent tool that provides a scientific approach for engineering solutions towards sustainability and assesses the environmental footprints concerned with a product’s life span68. LCA is used for several applications and is usually considered as the full life span, the middle stage, and a portion of the life span69,70. The aim of the study is to measure the prospective energy consumption during the production of Ceiba pentandra fibre unified PG tile, conventional tile, and the influence of reducing PG tile on the environment due to the non-firing process. In this LCA study was done according to ISO 14,040 (2006). In this study, the middle stage, i.e. Cradle-to-gate, is considered for analysis54. This analysis supports assessing the environmental impact and improving the performance of the Ceiba pentandra fibre incorporated PG tile.

In carrying out this study, a few assumptions and boundary conditions were established to ensure feasibility and clarity. The physico-chemical properties of PG and Ceiba pentandra fibre used in the experimental program were assumed to be representative of similar materials sourced from other regions. For the LCA, a cradle-to-gate boundary was considered, with partial reliance on secondary datasets and published literature where complete industrial data were not available. It was further assumed that the pressing hydration process adopted at the laboratory scale can be extrapolated to industrial production without significant deviation in energy demand or product performance.

However, certain limitations are acknowledged. The LCA analysis did not consider the use phase or end-of-life scenarios, which may affect the overall environmental impact of PG-based tiles. Additionally, while mechanical properties such as bending and impact strength were extensively studied, durability-related aspects were beyond the present scope. Variability in PG quality across different fertilizer industries was also not investigated, and this may affect generalizability of the findings. These limitations provide opportunities for future research to strengthen the applicability of PG-based non-fired tiles.

System boundaries

Processing of raw material, production of tile, and packing are the system boundaries deliberated in this investigation for assessment71. The system boundaries of conventional tile production are shown in Fig. 3.

Owing to a lack of complete field data, scrutinising the environmental footprint is critical. Hence, the cradle to gate approach was considered as the system boundary for PG tile, which mainly consists of the formation of tile using raw materials, drying of tile, and sintering processes, applying glazing material, and firing of tile, and packing of tile58,59. Figure 4 illustrates the system boundaries of PG tile production.

Life cycle inventory (LCI)

LCI phase estimates the material consumption, waste generation and emissions during the life span of a product. The LCI phase creates data associated with the unit process. The affirmed functional unit is contingent on the goal of life-cycle assessment. Hence, 1 m2 was chosen as the functional unit. Raw material collection, energy consumption (energy required for surface preparation, sintering, glazing, firing) and transportation are considered as inputs, and the product development, waste production, and pollutants dispersion are considered as outputs for assessment54,55,56,57,58,59. The data required for ceramic tile life cycle inventory furnished by Tikul (2014) was considered as a reference.

Tikul examined the environmental impacts related to acidification, global warming, and ozone layer depletion during the production of 1 m2 ceramic tile. In production, each process ingests an extensive amount of energy that is considered for environmental impact assessment. Per square meter, 17.1 kg of raw material is utilized and 11.2 kg of ceramic tile produced. The electrical energy consumed for biscuit and glazing firing has been considered for analysis. 12.9 kg of raw material has been utilised for 1 m2 of tile production, and 10.3 kg of PG tile has been produced. Inventory analysis has been done using experimental and previously available data to assess the energy consumption and air pollution in tile production.

Results and discussions

Influence of water content on bending strength

Water-to-binder ratio has been varied, and different loading pressures (5, 10 and 15 MPa) were applied for the preparation of PG tile. Figure 5 exemplifies the bending strength test results of the PG tile. The optimal bending strength was recorded at 10 MPa loading pressure. The addition of 20% water content by mass of PG amplified the bending strength to 12.3 MPa. The main reason behind the strength attainment was the hydrophobic action of water present in the mix, which promoted a more homogeneous and consistent microstructure.

The optimal water content in the mix improved the packing density of PG and eased the dispersion of dehydrated particles. However, additional water disrupted the ideal packing and bonding of particles, resulting in a weaker product. Test results indicated that 20 wt% was found to be the optimal water content. The surplus water, i.e. more than 20 wt%, may intensify the di-hydrate crystals in the mix and reduce the bonding characteristics.

Influence of Ceiba Pentandra fiber addition on bending strength

The effect of ceiba pentandra fibre addition (0–12%) has been tested against the bending strength of the mixes comprising an optimal water content of 20% by mass of PG. Figure 6 illustrates the test values mixes incorporated with fibre for the optimal water content. Infusing fibre in the composite escalated the bending strength from 11.8 to 16.7 MPa for fibre incorporation up to 6% by mass of PG. In case of higher fibre addition, a deduction in bending strength has been noted for fibre addition more than 6 wt%.

During the pressing stage, the incorporation of fibers into the di-hydrated PG matrix considerably enhanced monolithic bonding within the mix. The integration of fibers acted as a micro-reinforcement and improved the overall bonding of the mix. Hence, an escalating trend was noticed in the bending strength. The fibers evenly distributed the stress in fracture zones and reduced crack propagation72,73,86. However, when the fibre content exceeded 6%, owing to the higher aspect ratio, the proliferation nature of the fibre was adversely affected. Therefore, a reduction in bending strength was recorded.

Influence of Ceiba Pentandra fiber addition on impact strength and water absorption

PG is highly hygroscopic, and tiles made from it can have high water absorption (up to 14% to 18% by weight). However, PG tile produced by pressing the hydration process has a water absorption of 9% by weight due to compaction during pressing, which reduces the capillary porosity and water absorption. The impact strength of the fibre-added PG tile was found to be 0.89 kJ/m2, whereas the impact strength of the non-fibre tile was found to be 0.57 kJ/m2. The increase in impact strength may be due to the addition of fibres that convert a brittle gypsum matrix into a tough, energy-absorbing composite. This increased the toughness of fiber-added tiles and shows significantly higher impact strength than non-fiber tiles.

Scanning electron microscopy analysis (SEM)

SEM analysis of the PG tile with fibre gives the microstructural characteristics of the concrete. The morphology of the conventional and PG tiles with fibre has been studied at the microscopic level. The presence of constituents may modify the pore size distribution of the matrix. Figure 7 shows the SEM image of a conventional tile and a PG tile with fibre. SEM images evidently showed the formation of calcium hydroxide (CH) and ettringite in the concrete. The formation of ettringite may be due to the presence of sulphate content in the mix, which could signal the reaction of these materials with hydrated products.

The SEM images (Fig. 7) reveal a relatively dense matrix with a heterogeneous distribution of pores. The pores are predominantly spherical to irregular in shape, with a size range of 5–20 μm, indicating a partially closed porosity pattern that may be attributed to the thermal processing and binder reactivity.

Furthermore, the fiber–matrix interface appears well-bonded, with minimal debonding or pull-out observed, suggesting effective stress transfer. This strong interfacial adhesion can be attributed to the chemical compatibility between the organic binder and fibre reinforcement, as well as the physical anchoring due to the surface roughness of the fibres.

As evident in the micrographs, crack propagation is often arrested at fiber bridges or redirected along weak zones around larger pores. These observations support the hypothesis that including natural fibers contributes significantly to crack bridging and energy dissipation during loading, thereby enhancing the toughness and post-cracking resistance of the composite tile.

Life cycle impact assessment of conventional tile vs. PG tile

The life cycle impacts of both tiles were assessed. Life cycle impact assessment (for 1 m2 of tile) consists of considering global warming, the ozone depletion layer, and acidification during the sintering process. The energy consumption of tile production is also deliberated74,75,76. Figure 8 illustrates the comparison of energy consumption during tile production.

Scalability is technically feasible due to the simplicity of the process, which requires only a hydraulic press and basic curing setups—both of which are widely accessible in semi-industrial or cottage-scale manufacturing units. The pressing hydration process does not require large energy infrastructure, thereby reducing both capital and operational expenditures. The manufacturing can be adapted to various tile sizes and shapes depending on mould design, making it versatile for different market demands.

From a market perspective, these tiles offer significant benefits: reduced material and processing costs (as quantified in the manuscript’s cost analysis section), improved impact and bending resistance (particularly at 6% fiber inclusion), and a reduced environmental footprint (~ 80% reduction in energy demand and CO₂ emissions). These attributes are particularly relevant in affordable housing projects, green building initiatives, and regions with limited energy infrastructure.

In terms of prospects, PG tiles can play a key role in promoting circular economy practices by valorising industrial waste, aligning with national and international sustainability goals. Standardisation efforts, field-scale validation, and integration into public procurement frameworks could further promote widespread adoption. Accordingly, we have included additional discussion in the conclusion and implications sections to reflect these points more clearly.

Tikul31 evaluated that per square meter of conventional tile production causes acidification of 0.21 kg SO2-eq and Ozone layer depletion of 2.38 × 10−7 kg CFC11-eq. From a Global warming point of view, 22.8 kg of CO2 was emitted, but not during PG tile production due to non-firing. Hence, PG tile production considerably reduced the environmental pollution69. During the production process, ceramic tile ingests 36.02 MJ of energy, but PG tile incurs only 7.36 MJ of energy. Tables 6 and 7 furnish the energy consumption details of conventional and PG tile.

The unit operations involved in conventional and PG tile production are shown in Table 879. The life cycle impact assessment clearly showed that PG tile production using the pressing hydration process can substantially reduce the environmental impact (Table 9). Exclusively reducing resource depletion and global warming. From the LCI study, it is substantiated that PG tile production consumes only 20% of the total energy consumed for conventional tile production.

The PG tile production process offers significant environmental and economic benefits, particularly in regions grappling with industrial waste management and affordable housing needs. However, technical, regulatory, and perceptual criteria must be fulfilled through standardization, quality control, and pilot-scale demonstrations to enable widespread adoption of PG tile. Production of PG tile acts as a valorisation route for large-scale PG disposal, especially near fertilizer plants and promotes a circular economy with zero-waste manufacturing in construction sectors.

Conclusion

The research findings led to several key conclusions in terms of ingredient content and from an implication perspective.

The optimal proportions of ingredients for PG tile production are.

-

Experimental results revealed that a water content of 20% by weight of PG can be considered as an optimal water content for producing PG tiles without compromising bending strength.

-

10 MPa was identified as an optimal loading pressure to produce PG tiles with good strength characteristics.

-

The optimal Ceiba pentandra fibre content was identified as 6%, and the tile produced with 6% fibre content with 20% water content by mass of PG achieved a bending strength of 16.7 MPa, meeting the Indian Standards requirement of ≥ 15 MPa.

Based on the LCA study, the following limitations are drawn in terms of implications for the environmental impact of the PG tile (cradle to gate level).

-

Production of PG tile using pressing hydration process witnessed lower environmental footprint such as acidification, ozone layer depletion and global warming than the conventional tile without detrimental to the strength characteristics.

-

An LCA study is used to ascertain the bottlenecks of a new, greener product. 80% of the cumulative energy demand has been reduced during the pressing hydration process with respect to conventional tile production.

-

The present LCA study has proven that the usage of PG tile extensively reduces the environmental impact. For precise environmental analysis, an accurate LCI dataset should be collected from the industry by considering the apparent environmental effects at a holistic system level.

-

The input data considered for life cycle assessment are case-specific. Hence, LCA have some limitations in evaluating the environmental impacts of a product.

-

On the whole, the production of PG tile with Ceiba pentandra fibre by pressing hydration process offers several benefits, predominantly in terms of economic viability, mechanical properties, and environmental sustainability. This innovative approach represents a potential paradigm shift in modern tile manufacturing.

Limitations

-

The scope of the LCA was limited to cradle-to-gate analysis, excluding use-phase and end-of-life impacts, which may influence the overall environmental profile of PG-based tiles.

-

The study focused primarily on mechanical strength (bending and impact strength) and did not extend to long-term durability tests such as freeze–thaw resistance, chemical stability under aggressive environments, or ageing performance.

-

Variations in the quality and consistency of PG from different fertilizer industries were not evaluated in this study, which may affect the generalizability of the results.

-

Scaling up from laboratory to industrial production may involve additional variables (e.g., moisture control, uniform fiber dispersion, curing conditions) that were not fully captured in the present study.

Statement of originality

The authors declare that this manuscript is original, has not been published before and is not currently being considered for publication elsewhere. The authors confirm that the manuscript has been read and approved by all named authors and that no other persons have satisfied the criteria for authorship but are not listed. The authors further confirm that all have approved the order of authors listed in the manuscript of us. The authors understand that the corresponding author is the sole contact for the Editorial process. The corresponding author is responsible for communicating with the other authors about progress, submissions of revisions and final approval of proofs.

Data availability

Data used in the study is present in the manuscript.

References

Jain, N., Maiti, S., Malik, J. & Sondhi, D. Development of sustainable water-resistant binder with FGD gypsum & fly ash, and its environmental impact evaluation via carbon footprint and energy consumption analysis. Sustainable Chem. Pharm. 37, 101376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scp.2023.101376 (2024).

Levickaya, K., Alfimova, N., Nikulin, I., Kozhukhova, N. & Buryanov, A. The use of phosphogypsum as a source of Raw materials for gypsum-based materials. Resources 13 (5), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources13050069 (2024).

Balti, S., Boudenne, A. & Hamdi, N. Characterization and optimization of eco-friendly gypsum materials using response surface methodology. J. Building Eng. 69, 106219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.106219 (2023).

Alfimova, N., Pirieva, S., Levickaya, K., Kozhukhova, N. & Elistratkin, M. The production of gypsum materials with recycled citrogypsum using semi-dry pressing technology. Recycling 8 (2), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling8020034 (2023).

Murali, G. & Azab, M. Recent research in utilization of phosphogypsum as Building materials. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 25, 960–987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.05.272 (2023).

Qin, X. et al. Resource utilization and development of phosphogypsum-based materials in civil engineering. J. Clean. Prod. 387, 135858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.135858 (2023).

Chernysh, Y., Yakhnenko, O., Chubur, V. & Roubik, H. Phosphogypsum recycling: a review of environmental issues, current trends, and prospects. Appl. Sci. 11 (4), 1575. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11041575 (2021).

Calderón-Morales, B. R., García-Martínez, A., Pineda, P. & García-Tenório, R. Valorization of phosphogypsum in cement-based materials: limits and potential in eco-efficient construction. J. Building Eng. 44, 102506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2021.102506 (2021).

Jin, Z., Ma, B., Su, Y., Qi, H. & Lu, W. Preparation of eco-friendly lightweight gypsum: use of beta-hemihydrate phosphogypsum and expanded polystyrene particles. Constr. Build. Mater. 297, 123837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.123837 (2021).

Ma, B. et al. Utilization of hemihydrate phosphogypsum for the Preparation of porous sound absorbing material. Constr. Build. Mater. 234, 117346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117346 (2020).

Tayibi, H., Choura, M., López, F. A., Alguacil, F. J. & López-Delgado, A. Environmental impact and management of phosphogypsum. J. Environ. Manage. 90 (8), 2377–2386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2009.03.007 (2009).

Wang, Y. B., Zhang, W., Chen, C. & He, T. S. Effect of curing time and CaSO4 whisker content on properties of gypsum board. Appl. Mech. Mater. 507, 222–225. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.507.222 (2014).

Sun, T. et al. Optimization on hydration efficiency of an all-solid waste binder: carbide slag activated excess-sulphate phosphogypsum slag cement. J. Building Eng. 86, 108851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2024.108851 (2024).

Broeren, M. L. et al. Life cycle assessment of Sisal fibre–exploring how local practices can influence environmental performance. J. Clean. Prod. 149, 818–827. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.02.073 (2017).

Marsh, R. Building lifespan: effect on the environmental impact of Building components in a Danish perspective. Architectural Eng. Des. Manage. 13 (2), 80–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/17452007.2016.1205471 (2017).

Anusha, H. M., Bariker, P. & Viswanath, B. Analysis of strength properties of lime stabilized black cotton soil with Phosphogypsum. In Proceedings of the Indian Geotechnical Conference 2019: IGC-2019 Volume III (pp. 385–393). Singapore: Springer Singapore. (2021)., April https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-33-6444-8_35

Berndt, M. L. Properties of sustainable concrete containing fly ash, slag and recycled concrete aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 23 (7), 2606–2613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2009.02.011 (2009).

Ajam, L., Hassen, A. B. E. H. & Reguigui, N. Phosphogypsum utilization in fired bricks: radioactivity assessment and durability. J. Building Eng. 26, 100928. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2019.100928 (2019).

Macías, F., Pérez-López, R., Cánovas, C. R., Carrero, S. & Cruz-Hernandez, P. Environmental assessment and management of phosphogypsum according to European and united States of America regulations. Procedia Earth Planet. Sci. 17, 666–669. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeps.2016.12.178 (2017).

Tirado, R. & Allsopp, M. Phosphorus in agriculture: problems and solutions. Greenpeace Research Laboratories Technical Report (Review), 2. (2012). https://www.greenpeace.to/greenpeace/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/Tirado-and-Allsopp-2012-Phosphorus-in-Agriculture-Technical-Report-02-2012.pdf

Arunvivek, G. K. & Rameshkumar, D. Experimental investigation on feasibility of utilizing phosphogypsum in E-Glass Fiber-incorporated Non-fired ceramic wall tile. J. Institution Eng. (India): Ser. A. 103 (2), 445–451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40030-021-00604-2 (2022).

Li, G. et al. Performance and hydration mechanism of MSWI FA-barium slag-based all-solid waste binder. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 192, 588–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2024.10.093 (2024).

Yang, L., Yan, Y., Hu, Z. & Xie, X. Utilization of phosphate fertilizer industry waste for belite–ferroaluminate cement production. Constr. Build. Mater. 38, 8–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2012.08.049 (2013).

Framinan, J. M., Leisten, R. & Ruiz García, R. A case study: ceramic tile production. In Manufacturing Scheduling Systems: an Integrated View on Models, Methods and Tools 371–395 (Springer London, 2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-6272-8_15.

Mechi, N., Khiari, R., Ammar, M., Elaloui, E. & Belgacem, M. N. Preparation and application of Tunisian phosphogypsum as fillers in papermaking made from Prunus amygdalus and Tamarisk Sp. Powder Technol. 312, 287–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2017.02.055 (2017).

Paswan, R. K., Kumar, P., Kumar, V. & Sembeta, R. Y. Mechanical properties of alkali activated slag binder based concrete at elevated temperatures. Discover Sustain. 6 (1), 744. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-025-01542-w (2025).

Li, X. et al. Immobilization of phosphogypsum for cemented paste backfill and its environmental effect. J. Clean. Prod. 156, 137–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.04.046 (2017).

Tikul, N. Assessing environmental impact of small and medium ceramic tile manufacturing enterprises in Thailand. J. Manuf. Syst. 33 (1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmsy.2013.12.002 (2014).

Dharmaraj, R. et al. Novel approach to handling microfiber-rich dye effluent for sustainable water conservation. Adv. Civ. Eng. 1(2021), 1323472. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/1323472 (2021).

Li, X., Lv, X. & Xiang, L. Review of the state of impurity occurrences and impurity removal technology in phosphogypsum. Materials 16 (16), 5630. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16165630 (2023).

Breedveld, L., Timellini, G., Casoni, G., Fregni, A. & Busani, G. Eco-efficiency of fabric filters in the Italian ceramic tile industry. J. Clean. Prod. 15 (1), 86–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2005.08.015 (2007).

Goldoni, S. & Bonoli, A. A Case Study about LCA of Ceramic Sector: Application of Life Cycle Analysis Results To the Environment Management System Adopted by the Enterprise (University of Bologna, 2006).

Arunvivek, G. K. & Rameshkumar, D. Experimental investigation on performance of waste cement sludge and silica fume-incorporated Portland cement concrete. J. Institution Eng. (India): Ser. A. 100 (4), 611–618. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40030-019-00399-3 (2019).

Mezquita, A., Monfort, E., Ferrer, S. & Gabaldón-Estevan, D. How to reduce energy and water consumption in the Preparation of Raw materials for ceramic tile manufacturing: dry versus wet route. J. Clean. Prod. 168, 1566–1570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.04.082 (2017).

González-Benito, J. & González‐Benito, Ó. A review of determinant factors of environmental proactivity. Bus. Strategy Environ. 15 (2), 87–102. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.450 (2006).

Itard, L. & Klunder, G. Comparing environmental impacts of renovated housing stock with new construction. Building Res. Inform. 35 (3), 252–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613210601068161 (2007).

Meyer, C. The greening of the concrete industry. Cem. Concr. Compos. 31 (8), 601–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2008.12.010 (2009).

Yilmaz, I., Yildirim, M. & Marschalko, M. Effect of surface void percentage (SVP) on the unconfined compressive strength (UCS) of porous rocks. Q. J. Eng. Geol.Hydrogeol. 51 (1), 108–112. https://doi.org/10.1144/qjegh2016-024 (2018).

Geremew, A., Outtier, A., De Winne, P., Demissie, T. A. & De Backer, H. An experimental investigation on the effect of incorporating natural fibers on the mechanical and durability properties of concrete by using treated hybrid Fiber-Reinforced concrete application. Fibers 13 (3), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/fib13030026 (2025).

Karimah, A. et al. A review on natural fibers for development of eco-friendly bio-composite:characteristics, and utilizations. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 13, 2442–2458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2021.06.014 (2021).

Geremew, A., Winne, P. D., Adugna, T. & Backer, H. D. Mechanical properties of concrete using natural fibres-An overview. In AIP Conference Proceedings (Vol. 2404, No. 1, p. 080034). AIP Publishing LLC. (2021)., October https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0068874

Vidya, J., Sunitha, R., Malavika, T. & Prakash, C. Influence of Ceiba Pentandra fibre orientation on mechanical properties of biocomposites—a rudimentary approach. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery. 15 (5), 7751–7761. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-024-05541-1 (2025).

Purnawati, R. et al. Physical and chemical properties of Kapok (Ceiba pentandra) and Balsa (Ochroma pyramidale) fibers. J. Korean Wood Sci. Technol. 46 (4), 393–401 (2018).

Chan, E. W. C. et al. Ceiba Pentandra (L.) Gaertn.: an overview of its botany, uses, reproductive biology, Pharmacological properties, and industrial potentials. J. Appl. Biology Biotechnol. 10 (20), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.7324/JABB.2023.110101 (2022).

Andoko, A. et al. Performance of carbon fiber (CF)/Ceiba Petandra fiber (CPF) reinforced hybrid polymer composites for lightweight high-performance applications. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 27, 7636–7644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.11.103 (2023).

Sangalang, R. H. Kapok fiber-structure, characteristics and applications: a review. Orient. J. Chem. 37 (3), 513–523. https://doi.org/10.13005/ojc/370301 (2021).

Lilargem Rocha, D. et al. A review of the use of natural fibers in cement composites: concepts, applications and Brazilian history. Polymers 14(10): 2043 (2022) . https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14102043

Sanjay, M. R. & Siengchin, S. Editorial corner-a personal view Exploring the applicability of natural fibers for the development of biocomposites. Express Polym. Lett. https://doi.org/10.3144/expresspolymlett.2021.17 (2021).

Rebitzer, G. et al. Life cycle assessment: Part 1: Framework, goal and scope definition, inventory analysis, and applications. Environment international 30(5), 701–720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2003.11.005 (2004).

Bovea, M. D., Saura, Ú., Ferrero, J. L. & Giner, J. Cradle-to-gate study of red clay for use in the ceramic industry. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 12 (6), 439–447. https://doi.org/10.1065/lca2006.06.252 (2007).

IS 13630 (part 6). : Ceramic Tiles — Methods of Test, Sampling and Basis for Acceptance. (2006).

ISO 14040. 2006 Environmental management - Life cycle assessment - Principles and framework.

IS0 10545. (Part13): 2016(E) Ceramic tile – Determination of acid resistance.

Mezquita, A., Boix, J., Monfort, E. & Mallol, G. Energy saving in ceramic tile kilns: cooling gas heat recovery. Appl. Therm. Eng. 65 (1–2), 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2014.01.002 (2014).

Monfort, E. et al. Consumo de energía térmica y emisiones de dióxido de carbono en la fabricación de baldosas cerámicas Análisis de las industrias Española y Brasileña. Boletín de la. Sociedad Española de Cerámica y Vidrio, 51(5), 275–284. https://doi.org/10.3989/cyv.392012 (2012).

Nicoletti, G. M., Notarnicola, B. & Tassielli, G. Comparative life cycle assessment of flooring materials: ceramic versus marble tiles. J. Clean. Prod. 10 (3), 283–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-6526(01)00028-2 (2002).

Ye, L., Hong, J., Ma, X., Qi, C. & Yang, D. Life cycle environmental and economic assessment of ceramic tile production: A case study in China. J. Clean. Prod. 189, 432–441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.04.112 (2018).

Sahu, A., Kumar, P., Pratap, B., Gogineni, A. & Sembeta, R. Y. Thermal and mechanical performance of geopolymer concrete with recycled aggregate and copper slag as fine aggregate. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 28968. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15153-y (2025).

De Souza, W. J. V., Scur, G., de Hilsdorf, C. & W Eco-innovation practices in the Brazilian ceramic tile industry: the case of the Santa Gertrudes and Criciúma clusters. J. Clean. Prod. 199, 1007–1019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.06.098 (2018).

Shen, Y., Qian, J., Chai, J. & Fan, Y. Calcium sulphoaluminate cements made with phosphogypsum: production issues and material properties. Cem. Concr. Compos. 48, 67–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2014.01.009 (2014).

Franković Mihelj, N., Ukrainczyk, N., Leakovic, S. & Šipušić, J. Waste Phosphogypsum–Toward sustainable reuse in calcium sulfoaluminate cement based buildingmaterials. Chem. Biochem. Eng. Q. 27 (2), 219–226 (2013). https://hrcak.srce.hr/104812

Thyavihalli Girijappa, Y. G., Rangappa, M., Parameswaranpillai, S., Siengchin, S. & J., & Natural fibers as sustainable and renewable resource for development of eco-friendly composites: a comprehensive review. Front. Mater. 6, 226. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmats.2019.00226 (2019).

Zhou, J. et al. A novel two-step hydration process of Preparing cement-free non-fired bricks from waste phosphogypsum. Constr. Build. Mater. 73, 222–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.09.075 (2014).

Singh, M. Treating waste phosphogypsum for cement and plaster manufacture. Cem. Concr. Res. 32 (7), 1033–1038. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0008-8846(02)00723-8 (2002).

Blengini, G. A., Busto, M., Fantoni, M. & Fino, D. Eco-efficient waste glass recycling: integrated waste management and green product development through LCA. Waste Manage. 32 (5), 1000–1008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2011.10.018 (2012).

Redmond, J., Walker, E. & Wang, C. Issues for small businesses with waste management. J. Environ. Manage. 88 (2), 275–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2007.02.006 (2008).

Pan, W., Li, K. & Teng, Y. Rethinking system boundaries of the life cycle carbon emissions of buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 90, 379–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2018.03.057 (2018).

Li, H. et al. Investigation on mechanical properties of excess-sulfate phosphogypsum slag cement: From experiments to molecular dynamics simulation. Constr. Build. Mater. 315, 125685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.125685 (2022).

Liu, G. et al. Preparation of phosphogypsum (PG) based artificial aggregate and its application in the asphalt mixture. Constr. Build. Mater. 356, 129218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.129218 (2022).

Yoshihiko, F. Life cycle assessment (LCA) study of ceramic products and development of green (reducing the environmental impact) processes. Annual Report of the Ceramics Research Laboratory Nagoya Institute of Technology, Japan, 37, 45. (2004).

Huang, Y., Bird, R. & Heidrich, O. Development of a life cycle assessment tool for construction and maintenance of asphalt pavements. J. Clean. Prod. 17 (2), 283–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2008.06.005 (2009).

Finkbeiner, M., Inaba, A., Tan, R., Christiansen, K. & Klüppel, H. J. The new international standards for life cycle assessment: ISO 14040 and ISO 14044. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 11 (2), 80–85. https://doi.org/10.1065/lca2006.02.002 (2006).

Gabaldón-Estevan, D., Criado, E. & Monfort, E. The green factor in European manufacturing: a case study of the Spanish ceramic tile industry. J. Clean. Prod. 70, 242–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.02.018 (2014).

Sun, T. et al. A new eco-friendly concrete made of high-content phosphogypsum-based aggregates and binder: mechanical properties and environmental benefits. J. Clean. Prod. 400, 136555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136555 (2023).

Geraldo, R. H. et al. Calcination parameters on phosphogypsum waste recycling. Constr. Build. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.119406 (2020).

Campos, M. P., Costa, L. J. P., Nisti, M. B. & Mazzilli, B. P. Phosphogypsum recycling in the Building materials industry: assessment of the radon exhalation rate. J. Environ. Radioact. 172, 232–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvrad.2017.04.002 (2017).

Baraniak, J. & Kania-Dobrowolska, M. Multi-purpose utilization of Kapok fiber and properties of Ceiba Pentandra tree in various branches of industry. J. Nat. Fibers. 20 (1), 2192542. https://doi.org/10.1080/15440478.2023.2192542 (2023).

Kumar, S. et al. Physical and mechanical properties of natural leaf fiber-reinforced epoxy polyester composites. Polymers 13 (9), 1369. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13091369 (2021).

Kumar, P. S. et al. A sustainable bioengineering approach for enhancing black cotton soil stability using waste foundry sand. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 20, 1112–1120. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijlct/ctaf054 (2025).

Kumar, P. et al. Thermal performance prediction for alkali-activated concrete using GGBFS, NaOH, and sodium silicate. Civ. Eng. Infrastruct. J. https://doi.org/10.22059/ceij.2024.369661.1996 (2024).

Kumar, P., Pratap, B. & Sahu, A. Recycled aggregate with GGBS geopolymer concrete behaviour on elevated temperatures. J. Struct. Fire Eng. 16 (1), 118–137. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSFE-07-2024-0019 (2025).

Pratap, B., Paswan, R. K. & Kumar, P. Mechanical and micro-characterization of alkali‐activated concrete under high‐temperature exposure. Struct. Concrete. 26 (2), 1911–1923. https://doi.org/10.1002/suco.202301157 (2025).

Kumar, P., Gogineni, A. & Ammarullah, M. I. Sustainable bioengineering approach to industrial waste management: LD slag as a cementitious material. Discover Sustain. 6 (1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-025-00981-9 (2025).

Paswan, R. K., Gogineni, A., Sharma, S. & Kumar, P. Predicting split tensile strength in Portland and geopolymer concretes using machine learning algorithms: a comparative study. J. Building Pathol. Rehabilitation. 9 (2), 129. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41024-024-00485-5 (2024).

Kumar, P., Gogineni, A. & Upadhyay, R. Mechanical performance of fiber-reinforced concrete incorporating rice husk Ash and recycled aggregates. J. Building Pathol. Rehabilitation. 9 (2), 144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41024-024-00500-9 (2024).

Arunvivek, G. K., Anandaraj, S., Kumar, P., Pratap, B. & Sembeta, R. Y. Compressive strength modelling of cenosphere and copper slag-based geopolymer concrete using deep learning model. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 27849. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13176-z (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully thank the authors’ respective institutions for their strong support of this study.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G. K. Arunvivek: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - original draft. Pramod Kumar: Project administration, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. J. Rajprasad: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Sanjay Sharma: Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Investigation, Review, and editing. Regasa Yadeta Sembeta: Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Institutional Review Board Statement.

Not applicable.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Clinical trial

Not applicable.

Informed consent

to participate.

Not applicable.

Ethical statement

This study did not involve human participants or animals; no ethical approval was required. All research procedures adhered to relevant ethical guidelines and best practices for non-human and non-animal research.

Declaration of AI use.

The authors declare they will not use AI-assisted technologies to create this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Arunvivek, G.K., Kumar, P., Rajprasad, J. et al. Evaluation of nonfired ceramic tiles using phosphogypsum waste and Ceiba Pentandra fiber for sustainable construction. Sci Rep 15, 39681 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23225-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23225-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Synergic utilization of waste glass powder for fire-resilient and low alkali-activated concrete

Scientific Reports (2026)

-

Interface improvement and multiscale assessment of recycled concrete aggregates with epoxy resin polymer

Scientific Reports (2026)