Abstract

This paper proposes the improved data driven strategy for aircraft control system, including three aspects, i.e. data driven identification, data driven control and data driven validation. Firstly, after reviewed the classical aircraft flight control system as one closed loop system with the unknown aircraft model and controller, within the framework of perfect tracking, controller is yielded through solving one optimization problem. To give one explicit form of cost function, data driven identification is applied to construct one auxiliary model, replacing the unknown aircraft model. Secondly, to avoid the modeling process, data driven control is applied to design one parameterized control, whose controller parameters are tuned by gradient algorithm. Thirdly, to testify whether the designed controller work well, data driven validation is applied to the correlation based validation method. Finally, the detailed derivations about our proposed data driven strategy are given from the point of theoretic aspect, and its application in aircraft flight system is also given. Generally, this paper combines our new contributions from the theory of data driven strategy and its practical application.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

During the military field, aircraft has become increasingly important as one tactical weapon, as it is used for reconnaissance, surveillance and attack tasks, etc. Thus the risk of casualties among soldiers is reduced and the combat efficiency is also improved. With the continuous development of technology, autonomous flight level of aircraft is gradually improved, for example, aircraft uses deep learning and artificial intelligence technology to achieve the autonomous obstacle avoidance, autonomous risk reduction and autonomous interaction and other interesting functions, so aircraft is more safe or smart in latter military application. Furthermore, aircraft is also applied in commercial and civilian fields. More specifically, for agricultural practice, aircraft has revolutionized crop management, as aircraft is not only used for real time monitoring whether crop grows well, but also play a key role in fertilization or pesticide spraying. Based on this developing aircraft technology, the final overall quality of agricultural products is greatly improved. Also aircraft shows its unique value in the construction industry, such as routine site inspection and multi directional monitoring through detecting the potential safety hazards quickly. Generally, aircraft improves the safety and overall efficiency of construction effectively. In addition, aircraft plays an important role in photography, geological survey and other fields, providing us with a more comprehensive and intuitive perspective. From above concise description about aircraft’s important applications in different fields, lots of research about aircraft are ongoing from different subjects, for example, aircraft control, aircraft target detection, aircraft trajectory planning, aircraft identification, aircraft formation dynamic, etc., meaning aircraft is a combination with above mentioned subjects. In addition of these functional modules work well, aircraft will be smarter, just like a bird.

During these past decades, a great deal of process has been yielded in theory and application of ideas in advanced control theory for mechanical systems. The areas of application of control theory for mechanical systems are diverse and challenging, and it constitutes an important factor for the interest in these systems, corresponding to robotics and automation, autonomous vehicles in marine, aerospace, and other environments, flight control problems in nuclear magnetic resonance, micro-electromechanical systems, and fluid mechanics. Moreover, the areas of overlap between mechanics and control posse the sort of mathematical elegance that makes them appealing to study independently of applications. As aircraft control is to guarantee the considered aircraft fly according to the desired trajectory or path, while considering other flight missions, for example, minimum flight time or minimum short flight trajectory, so this paper concerns on aircraft controller design by virtue of data driven strategy, without any prior knowledge about the unknown aircraft model, i.e. extracting one controller from the measured data directly. In 2020 s, this innovative control method is studied very popularly, named as data driven control strategy. As data driven control only needs the input-output data analysis process, it is also strongly supported in the control fields. Reference1 designed the optimal output stable control strategy using the input-output data of the system, reference2 identified aircraft parameters using frequency-domain response combined with American commercial software, and designed a linear quadratic controller for attitude control, while the position controller was designed based on Lyapunov and backstepping theory. Reference3 designed a class of nonlinear discrete single input and single output systems using pseudo-gradients and input-output data, which had good robustness. Reference4 used Kalman filter to estimate the parameters of the longitudinal model in detail, and then designed the linear quadratic controller based on the minimum energy principle. Reference5 used the excitation signal to identify the linear parameter varying model, and redesigned the position and attitude controller according to the cascade structure. Reference6 identified disturbances generated by changes in wind or load and predicted the output results. Reference7 combined data-driven and consistency principles, then a data-driven distributed optimal consistent controller was designed for unknown systems with input time-delay, and the optimal control of finite time periods was applied in time-delay systems. Reference8 used an echo state network approach to predict the system’s speed and angular speed based on identification of aircraft parameters. Reference9 used the system black box identification to obtain the mathematical model of aircraft attitude loop, and designed a robust controller, whose attitude control precision was superior to proportion integration differentiation control. As above mentioned references study the problem about aircraft controller design on the point of linear system and linear controller, but in this paper we take another point to solve this interesting control problem from the nonlinear system and controller directly.

During recent years, our team also obtains some new contributions about aircraft controller design. For example, our paper10 proposes one nonlinear data driven control from theoretical analysis and practical engineering, i.e. aircraft formation flight system. Paper11 combines direct data driven control and other safety property to form an innovative direct data driven safety control for aircraft flight system. In paper12, a novel iterative learning data driven control strategy is established to efficiently design the flight controller for closed loop aircraft flight system, while avoiding the modeling process for that unknown aircraft system. Roughly speaking, above existed results about controller design for aircraft system are divided into two steps, i.e. the first linearization process and the second controller design process. More specifically, the considered aircraft system and the unknown controller are all linearized as their corresponding linear forms, then the existed results about linear controller design methods are applied directly, as there are lots of literatures about linear control theory, i.e. the number of literatures about linear control theory is vast. For example for our previously studied direct data driven strategy, we always assume that unknown controller be one linear form, such as PID controller or neural network controller etc., so the latter problem is turned to identify these unknown controller parameters from the observed input-output data sequence, i.e. parameter identification process. The formulation about nonlinear controller design for nonlinear aircraft system can be seen reference12, where a preliminary about the control process is given.

The purpose of aircraft control is to complete all various flight tasks for each mode through adjusting the attitude trajectory. For clarity of presentation about aircraft control technique, aircraft experiences three phases, i.e. tethered flight, remote controlled flight within visual range, and over-the –horizon autonomous control flight13. Tethered flight is a form of early stage which adopts a rope to connect aircraft and ground surface, then power is supplied directly from the ground through cables, resulting in a long lag time. But its disadvantage is that the ground station cannot be separated from aircraft, which restricts the range of life off, so tethered flight is not used during modern aircraft flight process due to small reconnaissance area and easily being located or attacked14. Flight control is the key to the realization of remote control and over the horizon autonomous flight with the increasing applications of reliable electronic equipment, navigation system and data transmission technology15. Remote controlled flight breaks the strict limitations of tethered flight, placing considerable demands on flight control system, radio information transmission system. Roughly speaking, after 1980 s, with the rapid developments of flight control technology and electronic technology, it becomes possible for aircraft to fly completely autonomously16. Such advanced aircraft has a powerful central control computer on board, which inputs the flight tasks to computer in form of preprogramming, and the ground control station carries out real time monitoring mission and intervene with human17. This type of flight control brings more higher requirements on the information acquisition and processing system, which are loaded with advanced radar and digital camera equipment, and have stable, reliable or high speed data transmission channel between aircraft and ground control station18. All above ensure the uploading of commands and downloading of data. Generally, at present aircraft control still has some shortcomings, mainly on the lack of ability to cope with emergencies, only implementing the predetermined tasks and low degree of intelligences.

Based on above detailed descriptions about aircraft controller design and our previous contributions about data driven control for aircraft flight control system, this new paper continues to do some improvements about our considered data driven control strategy for aircraft flight control system. Specifically, after describing the commonly used aircraft flight control system as one classical closed loop system structure with the unknown aircraft system and unknown controller simultaneously, the main idea is to design that unknown controller while satisfying some control performances, such as perfect tracking, robustness, disturbance rejection etc. To solve controller design problem, we propose to apply data driven strategy within the known or unknown aircraft system respectively. Formally speaking, under the requirement of perfect tracking, two data driven strategies are studied in detail respectively. The first case corresponds to model-based control, i.e. applying data driven strategy to identify or construct one priori model for aircraft system. The second case is data driven control, using the measured input-output data sequence to yield one controller while satisfying that perfect tracking. To the best of our knowledge that data driven strategy is very benefit for one special parameterized controller, as the problem of controller design is transformed into one parameter estimation problem, relying on the mature system identification theory and estimation theory. Furthermore, after the controller is designed, then one another problem appears, i.e. how to validate this yielded controller whether it works well. For completeness, the process of controller validation is given through our own mathematical derivations. Later to combine our proposed theories and their efficiencies in practice, one practical engineering example is shown from a practical point of view, i.e. designing one controller to guarantee aircraft fly according to our given trajectory.

Generally, in summary new contributions about data driven strategy of this paper are formulated as follows.

-

(1)

Data driven strategy is applied to complete the traditional tracking control through constituting one internal model for aircraft system.

-

(2)

Data driven strategy is applied to design that controller directly. For one special case of the parameterized controller, the detailed controller parameter are identified or tuned while analyzing the statistical convergence.

-

(3)

Data driven strategy is applied to validate the designed controller through the correlation analysis.

This paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, aircraft flight control system is reviewed to correspond one closed loop system with the unknown aircraft system and controller simultaneously. To achieving the goal of perfect tracking, in Sect. 3, data driven strategy is applied to combine the traditional tracking control and internal model control, i.e. data driven strategy is used to construct one internal model and replace that unknown aircraft system. To avoid this model construction process, data driven strategy is applied to design one special parameterized controller in Sect. 4, where the detailed algorithm of tuning the controller parameter is analyzed. To testify whether the designed controller is correct, the controller validation is given by the correlation analysis. Section 6 gives one practical example of aircraft flight control to show our proposed theories. Finally, Sect. 7 formulates our main contributions and points our future work.

Aircraft flight control system

Flight control law is the core of flight control system, as aircraft is a high order complex system with multi variables, nonlinearity, strong coupling and time varying property. Due to the asymmetry of aerodynamic characteristics and structure, aerodynamic coupling and control coupling increase the difficulty of designing flight controller, so the design of flight controller needs the mathematical model of the considered aircraft model and the priori information about feed forward or feedback controller. As aircraft has multiple flight modes, its flight controller may include the unified management and scheduling of flight modes, then aircraft flight controller must ensure the smooth switching of various flight modes.

Consider the complexity of designing flight controller and diversity of flight modes, a hierarchical model of aircraft flight control system is summarized in Fig. 1, where the whole hierarchical model is divided into three sublevels, i.e. high level, middle level, and low level, and each level has its different function. The information fusion unit collects data from different physical sensors and sends those useful flight data or instructions to the flight controller through wireless communication link. Then flight controller starts to make decision and control aircraft through the lower level.

According to the complete scheme of aircraft flight control system, it consists of the following five parts, i.e. computer system for data processing and control action, sensor system for sensing aircraft states, servo actuation system for controlling rudder surface, power adaptation system for power supply and ground measurement of control system for monitoring aircraft, being plotted in Fig. 2.

Due to space limit, we do not explain all five parts in Fig. 2. By the way, that computer system is responsible for many important tasks, for example, data collection, compute the control law and flight mission management etc. it uses a 32-bit microprocessor with powerful data processing capability, and provides conditions for implementing complex control laws to ensure the reliability and safety for flight control system, being defined as a position servo system in Fig. 3.

where in above Fig. 3, the dual closed loop system is composed of the current feedback and position feedback, which enables the position servo system to have fast transient response, precise tracking property and high stability, coming from the good effect of dual feedback.

Control strategy for perfect tracking

Observing Fig. 2, dual feedback loop exists in that aircraft flight control system. As the inner loop is only one unit feedback loop, and the external loop includes one unknown controller, so our extracted closed loop system is that external loop, i.e. reducing to one simplified structure in Fig. 4.

where in above Fig. 4, \(P\left( z \right)\)\(P\left( z \right)\)\(P\left( {} \right)\)\(P\left( z \right)\)\(P\left( z \right)\)is aircraft kinematic model, \(C\left( z \right)\)is the unknown controller. \(r\left( t \right)\)\(r\left( t \right)\)is the given input signal, \(u\left( t \right)\)is the controller output. y(t) is the whole closed loop system output, \(d\left( t \right)\)is the external noise or disturbance. \(M\left( z \right)\)is the desired or expected system for system response \({y_0}\left( t \right)\), i.e. \({y_0}\left( t \right)=M\left( z \right)r\left( t \right)\). Error signal \(e\left( t \right)=r\left( t \right) - y\left( t \right)\), and output error \(\xi \left( t \right)=y\left( t \right) - {y_0}\left( t \right)\). z is the shift operator.

Observing Fig. 4 again, some existing equations hold easily.

i.e.

From Eq. (2), we see the transfer function from input \(r\left( t \right)\)to output y(t) is\(\frac{{P\left( z \right)C\left( z \right)}}{{1+P\left( z \right)C\left( z \right)}}\), similarly the same meaning for transfer function \(\frac{1}{{1+P\left( z \right)C\left( z \right)}}\) is defined. When to consider the perfect tracking property, i.e. designing one controller \(C\left( z \right)\)to let \(\frac{{P\left( z \right)C\left( z \right)}}{{1+P\left( z \right)C\left( z \right)}}\)track that expected transfer function\(M\left( z \right)\), it can be formulated as the following optimization problem.

where above notation \(\left\| {} \right\|\)means Euclidean norm.

Furthermore, if we consider both the perfect tracking and disturbance rejection, Eq. (3) is changed to that.

where the second term is to reject the negative effect from disturbance, and parameter \(\lambda\)is a tuning value.

From both Eqs. (1) and (2), we also have.

So the controller output estimation \(\hat {u}\left( t \right)\)is deemed as that.

Then the error signal between \(\hat {u}\left( t \right)\)and \(u\left( t \right)\) is that.

Based on above prediction error performance\(u\left( t \right) - \hat {u}\left( t \right)\), controller \(C\left( z \right)\) is yielded to solve that.

Remark 1

Both Eqs. (4) and (5) consider the whole closed loop output \(y\left( t \right)\) to track one desired transfer function\(M\left( z \right)\). But Eq. (8) concerns on the controller output\(u\left( t \right)\), while guaranteeing the measured controller output \(u\left( t \right)\)be equal to its estimation\(\hat {u}\left( t \right)\), i.e. making the error signal \(u\left( t \right) - \hat {u}\left( t \right)\)be sufficient small.

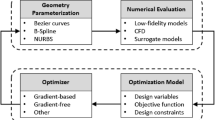

Observing Eqs. (4), (5) and (8) again, as that unknown aircraft system \(P\left( z \right)\)exists in all three cost functions, so when to solve them, the priori information or one explicit form of \(P\left( z \right)\)is needed. It means the first step is to construct one mathematical model\(\hat {P}\left( z \right)\), being used to replace that unknown aircraft system \(P\left( z \right)\)only through the measured data sequence\(\left\{ {u\left( t \right),y\left( t \right)} \right\}_{{t=1}}^{N}\), where N is the total number of data. Then above step is plotted in the following Fig. 5.

where in Fig. 5, that mathematical model \(\hat {P}\left( z \right)\)is called one internal model structure, being identified by data driven identification.

Improved data driven strategy

To avoid the modeling process for that unknown aircraft \(P\left( z \right)\)and design controller \(C\left( z \right)\)directly from the measured data, our improved data driven strategy is introduced here.

As the input-output for the unknown controller \(C\left( z \right)\)are\(\left\{ {e\left( t \right),u\left( t \right)} \right\}\), i.e. it holds that.

where Eq. (9) uses the perfect tracking property, i.e.

Collecting the following data sequence\(\left\{ {e\left( t \right),u\left( t \right)} \right\}_{{t=1}}^{N}=\left\{ {u\left( t \right),\left[ {{M^{ - 1}}\left( z \right) - 1} \right]y\left( t \right)} \right\}_{{t=1}}^{N}\), i.e. data sequence \(\left\{ {u\left( t \right),y\left( t \right)} \right\}_{{t=1}}^{N}\) are collected, and \(M\left( z \right)\)is given in priori, we need to look for a relation between \(u\left( t \right)\)and \(e\left( t \right)\) to guarantee that.

Let us parameterize above controller \(C\left( {z,e\left( t \right)} \right)\)with a finite dimensional parameter vector\(\theta\), i.e. \(C\left( {z,e\left( t \right),\theta } \right)\), for example.

where n is the order and \({c_k}\left( {e\left( t \right)} \right)\)is basis function, and

where \(\theta\)is one vector, combining all weights in Eq. (11), being the called control parameters.

Based on above linearized controller (8), then the controller design problem is turned to identify that controller parameter vector \(\theta\), i.e. controller parameters tuning problem.

To avoid notation burden, we denote that parameterized controller as\(C\left( \theta \right)\). From Eq. (10), as controller \(C\left( \theta \right)\)must satisfy that idea equity, so we minimize the error between the output of controller \(C\left( \theta \right)\)and its measured output \(u\left( t \right)\) by using data sequence \(\left\{ {e\left( t \right),u\left( t \right)} \right\}_{{t=1}}^{N}=\left\{ {u\left( t \right),\left[ {{M^{ - 1}}\left( z \right) - 1} \right]y\left( t \right)} \right\}_{{t=1}}^{N}\) and that given reference model \(M\left( z \right)\). Then the controller design problem is transformed into one parameter estimation or tuning problem, i.e.

Substituting Eqs. (10) and (11) into above (13), it holds that.

Observing above cost function, we see that desired reference model \(M\left( z \right)\)is given in prior, and input-output data \(\left\{ {u\left( t \right),y\left( t \right)} \right\}_{{t=1}}^{N}\)are measured through some physical devices, meaning only that controller parameters vector \(\theta\)is unknown and other physical variables are all known in priori. It is the essence of data driven control strategy.

Remark 2

Our control goal is to design one parameterized controller \(C\left( \theta \right)\)while satisfying perfect tracking, i.e. the closed loop output is that \(y\left( t \right)=M(z)r(t)\), where \(M\left( z \right)\)is one given reference model. Firstly, the perfect tracking is transformed to \(u\left( t \right)=C\left( \theta \right)e(t)=C\left( \theta \right)\left( {r(t) - y(t)} \right)=C\left( \theta \right)\left( {{M^{ - 1}}\left( z \right) - 1} \right)y(t)\). Secondly, based on this ideal equity, that unknown controller parameters vector \(\theta\) is identified to minimizing above cost function, suiting for the special parameterized controller.

When to solve above controller parameters from optimization problem (13), the commonly used gradient algorithm is used to generate one convergent sequence through its recursive form.

where \({\theta ^{k+1}}\) and \({\theta ^k}\)are the iterative values at step \(k+1\)and k respectively, \({\gamma _k}\)is step size. \(\frac{{\partial J\left( \theta \right)}}{{\partial \theta }}\)is the corresponding gradient vector, being computed as that.

The merit of gradient algorithm is that the convergence is guaranteed, meaning after k steps, the iterative value \({\theta ^{k+1}}\)will converge to its global optimum.

Remark 3

Because that feed forward control \(C\left( z \right)\)is parameterized by one unknown parameter vector \(\theta\), identified from one unconstrain optimization problem (13), so the original controller design problem is changed to one parameter estimation problem. The recursive parameter estimate is given by the classical gradient algorithm in Eq. (14). Then stability analysis for our improved data driven control strategy has two points, i.e. closed loop stability and parameter convergence, which are all coved in our previous paper19. If the reader is interesting in the detailed closed loop stability, please refer to that paper.

The main essence of data driven control is to extract some information about the unknown plant and controller directly from the measured input-output data\(\left\{ {u\left( t \right),y\left( t \right)} \right\}_{{t=1}}^{N}\), corresponding to the data fitting problem. For the special parameterized controller\(C\left( \theta \right)\), then the entire controller design process is changed to find the appropriate controller parameters to guarantee one ideal equity, i.e. \(u\left( t \right)=C\left( \theta \right)\left( {{M^{ - 1}}\left( z \right) - 1} \right)y(t),t=1 \cdots N\), where \(\left\{ {u\left( t \right),y\left( t \right)} \right\}_{{t=1}}^{N},M(z)\)are all known. To better understand the essence of data driven control strategy, please read our book20.

Controller validation

After controller \(C\left( {t,\hat {\theta }} \right)\)is designed or yielded, how to testify whether it is good or not, corresponding to controller validation process. A simple way to achieve it is to repeat the second experiment. Specifically, one input signal \(r\left( t \right)\)is chosen approximately as impulse or sine, then we collect the whole closed loop output\(y\left( t \right)\). Latter we testify if the equity holds, i.e. \(y\left( t \right)=M\left( z \right)r\left( t \right)\) or the error \(y\left( t \right) - M\left( z \right)r\left( t \right)\)is sufficient small. If it holds, then the designed controller \(C\left( {t,\hat {\theta }} \right)\)is accepted, or refuse it and repeat our above strategy.

This section proposes one correlation analysis to validate the controller\(C\left( {t,\hat {\theta }} \right)\). Firstly, based on the parameter estimation \({\theta ^k}\), define the following residual error \(\xi \left( {t,\hat {\theta }} \right)\).

Consider the following hypothesis.

H0: \(\xi \left( {t,\hat {\theta }} \right)\) is white and uncorrelated with\(r\left( t \right)\);

H1: \(\xi \left( {t,\hat {\theta }} \right)\) is correlated with\(r\left( t \right)\);

If H0 holds, then the residual error\(\xi \left( {t,\hat {\theta }} \right)\) form a white noise sequence, and it is uncorrelated with the excitation input \(r\left( t \right)\). Construct one correlation function between two sequences \(\xi \left( {t,\hat {\theta }} \right)\)and \(r\left( t \right)\), and test it by forming

\(E\left[ {\xi \left( {t,\hat {\theta }} \right)r\left( t \right)} \right]\)would be zero, provided the expectation exists. From probability theory, we have if H0 holds,, then

where

The correlation based validation method is equivalent to a stagewise regression procedure. The main idea of this correlation based validate method is to testify whether the residual error \(\xi \left( {t,\hat {\theta }} \right)\)is white noise and uncorrelated with input signal\(r\left( t \right)\). In addition, we only need to testify whether that statistical variable \({z_N}\left( {t,\hat {\theta }} \right)\)is a white noise with zero mean.

Simulation example

In this simulation example, a aircraft is used, as it can take off and land vertically. It has strong air control capability, good static flight and low speed flight characteristics. The altitude control of aircraft is achieved through collective pitch control. The size of the collective pitch determines the size of the main rotor lift. In fact, height control is to compare the real height fed back by the height sensor with the set height, and adjust the size of the collective distance according to the deviation value.

Flight control structure

In order to increase the control damping, the feedback of the rate of change of the height is introduced to form a cascade control system, shown in following Fig. 6, where all physical variables are defined in our previous paper11,12.

The altitude control loop adds the effect of the heading channel to the control law, \(\Delta \psi\) is the yaw angle. Due to the structural characteristics of aircraft with tail rotor, the lateral force required for left turning is greater than the lateral force required for right turning, so the power consumed by the tail rotor when turning left is relatively large, and the height of the helicopter will be as follows: turn left, go down; turn right, go up. Introduce yaw angle compensation in the altitude loop, properly increase the collective pitch when turning left, and appropriately reduce the collective pitch when turning right, so that the height of the helicopter will not fluctuate too much.

Velocity control for aircraft refers to the control of the forward flying speed. To make aircraft fly forward, it is generally necessary to change the longitudinal cyclic pitch, and use the pulling force generated by the rotor to pull aircraft forward to fly. Structure of this velocity control system is seen in Fig. 7.

where in this velocity control loop for aircraft in Fig. 7, \({u_g}\)is the given forward velocity, corresponding to the UAV body. The eastward velocity and northward velocity are measured by GPS, then after comparing them with their given velocities, one velocity error is generated.

Simulation result

During the simulation process for cascade controller design in the velocity loop system structure, one ideal aircraft model \(P\left( z \right)\) and that desired reference model \(M\left( z \right)\)are chosen as the following two transfer functions.

Based on the input signal and output signal in Fig. 8, our mission is to design one nonlinear form for that formation controller. Through using our proposed direct data driven control strategy, one approximated linear controller is applied to replace that nonlinear formation controller. Specifically, the commonly used linear affine form is used here, i.e.

Then our mission is to change to design these four above unknown parameters \(\left\{ {{a_0},{a_1},{a_2},{a_3}} \right\}\) from the input-output measured data. It corresponds to one data fitting problem, i.e. designing three parameters to guarantee the real output be same with the given output.

One controller, proposed by our improved data driven control, is applied to control aircraft flight trajectory. After takeoff, aircraft flies according to the predetermined track. We take the simulation process of 0 ~ 500 s for analysis, and the simulation process curve is shown in Fig. 9(a), where aircraft flies around one circle. More specifically, set the input values to these six degree of freedoms, i.e. \(x,y,z\), and the terminate value is 12 s, the output responses for aircraft flight system are also shown in Fig. 9(b), which tells us that after 15 s, aircraft will fly with one constant velocity, and as no any flutter or fluctuate, so latter aircraft flies well while approaching one stable state.

To compare our proposed improved data driven control and classical PID control, some simulation results are plotted in Fig. 10. Specifically, Fig. 10(a) is the reference or desired trajectory, and Fig. 10(b) shows the actual output response or trajectory, coming from the output response of our proposed improved data driven control strategy. Error curve between our control output and reference output is plotted in Fig. 10(c), and similarly Fig. 10(d) plots the error curve between PID control output and reference output. From Fig. 10(c) and Fig. 10(d), error curve in Fig. 10(c) is more stable than that in Fig. 10(d), and only one small jump appears at 50 s. But large deviate exists continuously during time interval [0,100] for PID control.

Conclusions

Based on our previous contributions on data driven control, this paper concerns on one improved data driven strategy for aircraft flight control system. A complete analysis about improved data driven strategy is given in detail including data driven identification, data driven control and data driven validation. Furthermore, above contents include some knowledge about identification, control and probability. The detailed derivations about our proposed improved data driven strategy are given from theoretic aspect, and its application in aircraft flight system is also given. Generally in the future, we will expand the research on data driven strategy to more complex systems.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Bemporad, A., Morari, M., Dwa, V. & Pistikopoulos, E. N. The explicit linear quadratic regulator for constrained systems. Automatica 38 (1), 3–20 (2002).

De Peris, C. & Tesi, P. Formulas for data driven control: stabilization, optimality and robustness. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control. 65 (2), 909–924 (2019).

Piga, D., Formentin, S. & Bemporad, A. Direct data driven control of constrained systems. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 26 (4), 1422–1429 (2018).

Florian Dorfler, J., Coulson, I. & Markovsky Bridging direct and indirect data driven control formulating via regularizations and relaxations. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control. 68 (2), 883–897 (2023).

Van Waarde, H. J., Camlibel, M. K. & Mesbahi, M. From noisy data to feedback controllers: non-conservative design via a matrix s-lemma. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control. 67 (1), 162–175 (2022).

Van Waarde, H. J., Eising, J., Trentelman, H. L. & Camlibel, M. K. Data informativity: a new perspective on data driven analysis and control. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control. 65 (11), 4753–4768 (2020).

Ivan Markovsky, P. & Rapisarda Data driven simulation and control. Int. J. Control. 81 (12), 1946–1959 (2008).

Berberich, J., Kohler, J., Muller, M. A. & Allgower, F. Data driven model predictive control with stability and robustness guarantee. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control. 66 (4), 1702–1717 (2021).

Tanaskovic, M., Fagiano, L., Novara, C. & Morari, M. Data driven control of nonlinear systems: an on line direct approach. Automatica 75 (1), 1–10 (2017).

Wang, J. Minimum variance control strategy for closed loop linear time invariant system. Int. J. Syst. Syst. Eng. 9 (1), 62–74 (2019).

Wang Jianhong, Z. & Ying, R. A. Direct data driven scheme for UAV flight control. IEEE Access. 10 (1), 108241–108250 (2022).

Wang Jianhong, G. & Xiaoyong Iterative learning data driven strategy for aircraft control system. Aircr. Eng. Aerosp. Technol. 95 (10), 1588–1595 (2023).

Alessio Moreschini, A. & Astilfi Closed loop interpolation by moment matching for linear and nonlinear system. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control. 70 (5), 2918–2933 (2025).

Florian Meiners, A., Himmel, J. & Adamy On a geometric notion of duality in nonlinear control systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control. 70 (4), 2122–2133 (2025).

Efstratics Stratoglou, A. A., Simoes & Anthory Bloch etc. On the geometry of virtual nonlinear nonholonomic constraints. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control. 70 (5), 3362–3369 (2025).

Karafyllis, I., Krstic, M. & Aslanidis, A. Deadzone adaptive disturbance suppression control for strict feedback systems. Automatica 17 (1), 1–12 (2025).

Pankaj, K., Mishra, P. & Jagtap Approximation free control for unknown systems with performance and input constraints. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control. 70 (5), 3417–3424 (2025).

Duran Deffin, J. E. & Garcia Beliran, C. D. Modeling and passivity based control for a convertible fixed wing VTOL. Appl. Math. Comput. 461 (1), 1–11 (2024).

Wen, R. W., Jianhong, W., Yanxiang, Z. & Bohua Adaptive direct data driven control for unknown closed loop system. Int. J. Innovative Comput. Inform. Control. 21 (2), 373–387 (2025).

Wang Jianhong, R. A., Ramirez_Mendoza & Morales-Menendez, R. Data Driven Strategy Theory and application. Boca. Raton. FL (CRC, 2023).

Funding

This work was supported by Projects of Jiangxi Provincial National Science Foundation (20232BAB201015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Methodology and Conceptualization, Wang Jianhong and Wen Ruchun.; writing-original draft preparation, Wang Jianhong. and Ricardo A. Ramirez-Mendoza.; writing-review and editing, Wang Jianhong. and Ricardo A. Ramirez-Mendoza.; software and validation, Julian C. Pena-Bermudez. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jianhong, W., Ramirez-Mendoza, R.A., Pena-Bermudez, J.C. et al. Improved data driven strategy for aircraft controller design. Sci Rep 15, 40438 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23233-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23233-2