Abstract

Recently, the rates of allergic diseases and cesarean delivery have increased worldwide. Some reports describe associations between allergic diseases and cesarean delivery. However, the association between allergic diseases and cesarean delivery is controversial. In this study, we investigated the association between cesarean delivery and the development of wheezing and eczema among infants at 1 year of age. We used data including those of 104,065 fetal records and their children from the Japan Environment and Children’s Study. Information about the mode of delivery, wheezing, eczema, asthma, and atopic dermatitis was obtained from medical record transcripts and questionnaires. Multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the risks of wheezing, eczema, asthma, and atopic dermatitis among infants at 1 year of age associated with cesarean delivery. We included 74,639 subjects in this study, wherein 18.4% underwent cesarean deliveries. Children born by cesarean delivery had no increased odds of developing wheezing (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 0.98; 95% confidence intervals [CI, 0.93–1.04], eczema (aOR = 0.99; 95% CI, 0.94–1.05), asthma (aOR = 0.95; 95% CI, 0.84–1.08), or atopic dermatitis (aOR = 1.02; 95% CI, 0.92–1.13).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, the incidence of allergic diseases has recently increased1. In Japan, allergic diseases are a serious health concern, with high rates of wheezing (16.4%), asthma (10.5%), and atopic dermatitis (21.5%) observed in children at 5 years of age2. Concurrently, cesarean delivery rates have been increasing around the world3,4,5. Some recent reports describe associations between allergic diseases and cesarean delivery6,7,8. Given that the increases in allergic disease rates have occurred over a short period of time, they may be associated with environmental factors. Compared with children born by vaginal delivery, those born by cesarean delivery have different gut flora and cytokine profiles9,10,11, which are thought to be related to allergic diseases. In contrast, some reports showed that delivery by cesarean section was not associated with the development of allergic diseases12,13,14. Therefore, the association between allergic diseases and cesarean delivery is controversial. In this study, we investigated the association between infants born by cesarean delivery and the development of wheezing and eczema among infants at 1 year of age using data from a large sample size cohort study of the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS).

Materials and methods

Study design

In the present study, we used data from the JECS, which is a nationwide, government-funded birth cohort study. The design of the JECS has been previously reported in detail15. The JECS investigates the effects of environmental factors on children’s health by tracking mothers and their children until the children reach 13 years of age15. From January 2011 to March 2014, 103,062 pregnancies were included in the JECS at 15 Regional Centres in Japan15. A total of 104,065 fetal records from pregnant women, including those with multiple pregnancies, were registered. Caregivers completed questionnaires regarding information about the mothers and their children during pregnancy and when the children were 6 and 12 months of age. The JECS protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ministry of the Environment’s Institutional Review Board on Epidemiological Studies and Ethics Committees of all participating institutions. The JECS was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and other nationally valid regulations and guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data collection

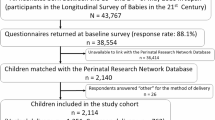

We used the dataset released in March 2018 (jecs-an-20180131). We excluded women who miscarried, had multiple births, whose babies were stillborn, or whose data regarding confounders were missing (Fig. 1).

Outcomes, exposures, and covariates

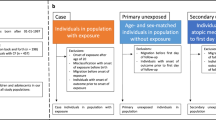

Wheezing, eczema, asthma, and atopic dermatitis were assessed based on the information given in the participants’ questionnaires when the children were 1 year old. The questionnaire included whether wheezing, eczema, asthma, and atopic dermatitis occurred in the first year of life. Information about wheezing, eczema, asthma, and atopic dermatitis was obtained from the responses to the question: “Has your child ever had wheezing or whistling in the chest at any time in the past?”, “Has your child ever had a recurring itchy rash for at least 2 months?”, “Immune system disorder diagnosed: Asthma”, and “Immune system disorder diagnosed: atopic dermatitis”. This was a validated, modified International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) questionnaire, translated in Japanese16,17,18. The subjects were assigned to a cesarean or vaginal delivery group, based on the modes of delivery. Moreover, participants in the cesarean delivery group were assigned to an elective or emergency group based on the reason for cesarean delivery: elective cesarean delivery included repeat cesarean delivery, history of uterine surgery, placenta previa, and fetal malpresentation and emergency cesarean delivery included gestational hypertension syndrome, nonreassuring fetal status, delayed/obstructed labor, early rupture of membrane, intrauterine infection, cephalopelvic disproportion, and complication/other reason. We considered the following factors as possible confounders in the regression analyses: maternal age at pregnancy, parity, sex, gestational age (GA), small for gestational age (SGA), maternal allergy history, maternal active and passive smoking during pregnancy, maternal educational levels, annual family income, marital status, breastfeeding at six months, pet ownership, and passive smoking exposure of infants after birth.

Statistical analyses

A chi-squared test was used to compare categorical variables. Multiple logistic regression was performed to determine the risks of wheezing, eczema, asthma, and atopic dermatitis associated with cesarean delivery by calculating the odds ratios (ORs), which were adjusted for the aforementioned confounders, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We initially adjusted for perinatal and socioeconomic factors and then added postnatal factors19. Finally, we estimated the association between elective and emergency cesarean delivery (vs. vaginal delivery) and the risks of wheezing, eczema, asthma, and atopic dermatitis. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata, version 15.0 (Stata Corporation LLC, College Station, TX, USA). A two-sided P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

After applying the study’s inclusion criteria, 74,639 subjects were eligible to participate in this study (Fig. 1). Comparison of the basic attributes between the analyzed (n = 74,639) and data-deficient groups (n = 23,616) was performed using the chi-square test. The phi coefficients in all comparisons of basic attributes were less than 0.1. Of the 74,639 mothers, 13,756 (18.4%) and 60,883 (81.6%) underwent cesarean and vaginal delivery, respectively (Table 1). Of the 13,756 cesarean deliveries, 8057 (10.8%) and 5699 (7.6%) were elective and emergency cesarean deliveries, respectively. The rates of wheezing, eczema, asthma, and atopic dermatitis in those born via cesarean delivery were 20.2%, 18.1%, 2.7%, and 4.2%, respectively; while the rates for those born via vaginal delivery were 19.5%, 19.0%, 2.5%, and 4.4%, respectively (Table 1). There were differences noted in the rate of eczema between the cesarean and vaginal delivery groups, while there were no differences in the rates of wheezing, asthma, and atopic dermatitis. A higher incidence of cesarean delivery was associated with a maternal age at pregnancy ≥ 30 years, parity ≥ 2, GA < 39 weeks, SGA, maternal smoking during pregnancy, higher maternal education, higher annual family income, and pet ownership. A lower incidence of cesarean delivery was associated with primipara and breastfeeding at six months.

Multiple logistic regression was performed to assess the risks of wheezing, eczema, asthma, and atopic dermatitis associated with cesarean delivery (Table 2). After adjusting for confounding factors, cesarean delivery was not associated with an increased odds of developing wheezing (adjusted OR [aOR] = 0.98; 95% CI, 0.93–1.04), eczema (aOR = 0.99; 95% CI, 0.94–1.05), asthma (aOR = 0.95; 95% CI, 0.84–1.08), or atopic dermatitis (aOR = 1.02; 95% CI, 0.92–1.13). Overall crude ORs and aORs for the association between elective and emergency cesarean delivery (vs. vaginal delivery) and the risks of wheezing, eczema, asthma, and atopic dermatitis are shown in Table 3. After adjusting for confounding factors, elective cesarean delivery was not associated with as increased odds of developing wheezing (aOR = 1.06; 95% CI, 0.99–1.12), eczema (aOR = 1.00; 95% CI, 0.94–1.06), asthma (aOR = 1.11; 95% CI, 0.96–1.27), or atopic dermatitis (aOR = 1.00; 95% CI, 0.90–1.13). After adjusting for confounding factors, emergency cesarean delivery was associated with a decreased odds of developing eczema (aOR = 0.91; 95% CI, 0.85–0.98) whereas it did not increase the odds of developing wheezing (aOR = 0.99; 95% CI, 0.92–1.06), asthma (aOR = 0.96; 95% CI, 0.79–1.16), or atopic dermatitis (aOR = 0.96; 95% CI, 0.83–1.10). Therefore, emergency cesarean delivery significantly decreased the odds of developing eczema but cesarean delivery or elective cesarean delivery was not associated with the development of wheezing and eczema up to 1 year of age.

Discussion

In this study, we found no associations between cesarean delivery and the development of wheezing and eczema among infants up to 1 year of age. Moreover, patients delivered through elective and emergency cesarean deliveries had no increased odds of developing wheezing and eczema among 1 year of age after adjusting for confounding factors. Numerous studies have investigated the associations between cesarean delivery and allergic diseases, but the results have been inconsistent. The findings from a previous meta-analysis that included 15 cohort studies, four case–control studies, and one cross-sectional study, showed an association between cesarean delivery and asthma, and an increased risk of asthma among children born by cesarean delivery (OR = 1.20; 95% CI, 1.14–1.26)8. Moreover, the authors of a meta-analysis that included 23 cohort studies and three case–control studies concluded that allergic outcomes were attributable to cesarean delivery in only 1–4% of subjects6. A recent birth cohort study in Korea reported that cesarean section delivery was associated with childhood asthma (aOR = 1.57; 95% CI, 1.36–6.14)20. A recent cross-sectional study in China showed that cesarean delivery was related to increased risk of wheezing by the age of 3 (aOR = 1.50; 95% CI, 1.06–2.12) and increased tendency to develop asthma by the age of 4 (aOR = 3.16; 95%CI, 1.25–9.01)21. In contrast, a population-based cohort study in the UK in 2004 showed that cesarean delivery was not associated with the subsequent development of physician-diagnosed asthma, wheezing, or atopy in later childhood (aOR = 1.14; 95% CI, 0.9–1.4; aOR = 0.95; 95% CI, 0.7–1.3]; and aOR = 1.04; 95% CI, 0.8–1.3, respectively)14. A population-based cohort study in the USA in 2005 showed that the mode of delivery was not associated with subsequent risk of developing childhood asthma (adjusted hazard ratio: 0.93; 95% CI, 0.6–1.4) or wheezing episodes (adjusted hazard ratio: 0.93; 95% CI, 0.7–1.3)13. A recent cohort study in Taiwan in 2017 showed that asthma was not associated with cesarean delivery after controlling for GA and parental history of asthma (aOR = 1.11; 95% CI, 0.98–1.25)12. A recent cohort study in Korea reported that cesarean section did not increase the prevalence of allergic diseases, including recurrent wheezing, asthma, and atopic dermatitis in infants up to 3 years of age22. A cross-sectional study in China reported that cesarean section delivery was associated with increased odds ratio of childhood asthma (aOR = 1.12; 95%CI, 0.99–1.26)23. Our results may be different with those of previous studies due to variable sample sizes, age groups, follow-up times, case definitions, and adjustments for confounding factors.

Children born by cesarean delivery show differences in relation to altered cytokine profiles and the establishment of their gut flora9,10,11. Hence, the delivery mode may be a crucial factor that influences the development of an infant’s immune system and subsequent incidence of disease. Altered perinatal toll-like receptor responses and aberrant changes in cord blood cytokine responses, including those associated with interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-13, tumor necrosis factor-α, and interferon-γ, are related to asthma, and neonates with bacterial colonization of the airways are at an increased risk of developing recurrent wheezing and asthma in early life11. Another mechanism may be changes in the stress hormone levels at birth between cesarean and vaginal deliveries because infants delivered by cesarean section before the onset of labor lack the normal surge of stress hormones24. These mechanisms may affect elective cesarean deliveries more than emergency cesarean deliveries because emergency cesarean deliveries are often performed after the onset of labor24. Children born by cesarean delivery, especially elective cesarean delivery, may have an increased risk of developing allergic diseases. However, some investigators report that the microbiome may be seeded before birth25. These findings may support our results that there were no associations between cesarean delivery and the development of wheezing and eczema.

The strengths of our study include the prospective and nationwide design that was adjusted for multiple factors including perinatal, socioeconomic, and postnatal factors. Moreover, we were able to distinguish between emergency and elective cesareans.

However, this study has several limitations. First, all outcomes were defined within the first year of life. This window may be too early to observe associations, especially with asthma, which is definitively diagnosed later in childhood. Respiratory function tests cannot be reliably interpreted in infants, making it difficult to accurately diagnose asthma in this age group. Furthermore, in early childhood, several conditions including infections can cause wheezing. As many studies have shown, assessing for asthma may be more appropriate in children around 5–6 years of ages. Second, unmeasured confounders may have influenced the association between cesarean delivery and the development of wheezing and eczema. Third, we evaluated allergic diseases using participants’ self-reported questionnaires, which may have led to the under-reporting of wheezing and eczema. This self-reporting could potentially bias the findings, particularly the null results. Fourth, no information was available regarding the extent and severity of wheezing and eczema. Finally, cesarean delivery may not have been strictly assigned to the elective or emergency cesarean delivery group in the JECS data; emergency cesarean delivery may have also included elective cesarean delivery. Despite these limitations, our study evaluated data from a large, nationwide, prospective birth cohort study, and therefore, provides strong evidence against an association between cesarean delivery and wheezing and eczema among infants up to 1 year of age. This may have important clinical and public health implications. Further studies are needed to evaluate whether cesarean delivery plays a role in the development of allergic diseases.

Data availability

Data are unsuitable for public deposition because of ethical restrictions and the legal framework of Japan. It is prohibited by the Act on the Protection of Personal Information (Act No. 57 of May 30, 2003, amended on September 9, 2015) to publicly deposit data containing personal information. The Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects enforced by the Japan Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology and the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare also restrict the open sharing of epidemiological data. All inquiries about access to data should be sent to jecs-en@nies.go.jp. The person responsible for handling inquiries sent to this e-mail address is Dr. Shoji F. Nakayama, JECS Program Office, National Institute for Environmental Studies.

References

Wong, G. W., Leung, T. F. & Ko, F. W. Changing prevalence of allergic diseases in the Asia-pacific region. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 5, 251–257. https://doi.org/10.4168/aair.2013.5.5.251 (2013).

Yamamoto-Hanada, K., Yang, L., Narita, M., Saito, H. & Ohya, Y. Influence of antibiotic use in early childhood on asthma and allergic diseases at age 5. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 119, 54–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2017.05.013 (2017).

Feng, X. L., Xu, L., Guo, Y. & Ronsmans, C. Factors influencing rising caesarean section rates in China between 1988 and 2008. Bull. World Health Organ. 90, 30–39. https://doi.org/10.2471/blt.11.090399 (2012).

Finger, C. Caesarean section rates skyrocket in Brazil. Many women are opting for caesareans in the belief that it is a practical solution. Lancet 362, 628. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14204-3 (2003).

Maeda, E. et al. Cesarean section rates and local resources for perinatal care in Japan: A nationwide ecological study using the national database of health insurance claims. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 44, 208–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/jog.13518 (2018).

Bager, P., Wohlfahrt, J. & Westergaard, T. Caesarean delivery and risk of atopy and allergic disease: Meta-analyses. Clin. Exp. Allergy 38, 634–642. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.02939.x (2008).

Chu, S. et al. Cesarean section without medical indication and risk of childhood asthma, and attenuation by breastfeeding. PLoS ONE 12, e0184920. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184920 (2017).

Thavagnanam, S., Fleming, J., Bromley, A., Shields, M. D. & Cardwell, C. R. A meta-analysis of the association between Caesarean section and childhood asthma. Clin. Exp. Allergy 38, 629–633. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02780.x (2008).

Dominguez-Bello, M. G. et al. Delivery mode shapes the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across multiple body habitats in newborns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 11971–11975. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1002601107 (2010).

Dominguez-Bello, M. G. et al. Partial restoration of the microbiota of cesarean-born infants via vaginal microbial transfer. Nat. Med. 22, 250–253. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.4039 (2016).

Liao, S. L. et al. Caesarean section is associated with reduced perinatal cytokine response, increased risk of bacterial colonization in the airway, and infantile wheezing. Sci. Rep. 7, 9053. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-07894-2 (2017).

Chen, G. et al. Associations of caesarean delivery and the occurrence of neurodevelopmental disorders, asthma or obesity in childhood based on Taiwan birth cohort study. BMJ Open 7, e017086. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017086 (2017).

Juhn, Y. J., Weaver, A., Katusic, S. & Yunginger, J. Mode of delivery at birth and development of asthma: A population-based cohort study. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 116, 510–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2005.05.043 (2005).

Maitra, A., Sherriff, A., Strachan, D. & Henderson, J. Mode of delivery is not associated with asthma or atopy in childhood. Clin. Exp. Allergy 34, 1349–1355. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.02048.x (2004).

Kawamoto, T. et al. Rationale and study design of the Japan environment and children’s study (JECS). BMC Public Health 14, 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-25 (2014).

Asher, M. I. et al. International study of asthma and allergies in childhood (ISAAC): Rationale and methods. Eur. Respir. J. 8, 483–491. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.95.08030483 (1995).

Ellwood, P., Asher, M. I., Beasley, R., Clayton, T. O. & Stewart, A. W. The international study of asthma and allergies in childhood (ISAAC): Phase three rationale and methods. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 9, 10–16 (2005).

Weiland, S. K. et al. Phase II of the international study of asthma and allergies in childhood (ISAAC II): Rationale and methods. Eur. Respir. J 24, 406–412. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.04.00090303 (2004).

Maeda, H. et al. Association of cesarean section and infectious outcomes among infants at 1 year of age: Logistic regression analysis using data of 104,065 records from the Japan Environment and Children’s Study. PLoS ONE 19, e0298950. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0298950 (2024).

Lee, E. et al. Associations of prenatal antibiotic exposure and delivery mode on childhood asthma inception. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 131, 52-58.e51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2023.03.020 (2023).

Lin, J. et al. The Associations of caesarean delivery with risk of wheezing diseases and changes of T cells in children. Front. Immunol. 12, 793762. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.793762 (2021).

Kim, H. I. et al. Cesarean section does not increase the prevalence of allergic disease within 3 years of age in the offsprings. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 62, 11–18. https://doi.org/10.5468/ogs.2019.62.1.11 (2019).

Hu, Y. et al. Breastfeeding duration modified the effects of neonatal and familial risk factors on childhood asthma and allergy: A population-based study. Respir. Res. 22, 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-021-01644-9 (2021).

Rusconi, F. et al. Mode of delivery and asthma at school age in 9 european birth cohorts. Am. J. Epidemiol. 185, 465–473. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwx021 (2017).

Willyard, C. Could baby’s first bacteria take root before birth?. Nature 553, 264–266. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-00664-8 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The findings and conclusions of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the Ministry of the Environment, Japan. We thank all the participants and staff involved in the JECS. Members of the JECS Group as of 2020: Michihiro Kamijima (principal investigator, Nagoya City University, Nagoya, Japan), Shin Yamazaki (National Institute for Environmental Studies, Tsukuba, Japan), Yukihiro Ohya (National Center for Child Health and Development, Tokyo, Japan), Reiko Kishi (Hokkaido University, Sapporo, Japan), Nobuo Yaegashi (Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan), Koichi Hashimoto (Fukushima Medical University, Fukushima, Japan), Chisato Mori (Chiba University, Chiba, Japan), Shuichi Ito (Yokohama City University, Yokohama, Japan), Zentaro Yamagata (University of Yamanashi, Chuo, Japan), Hidekuni Inadera (University of Toyama, Toyama, Japan), Takeo Nakayama (Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan), Hiroyasu Iso (Osaka University, Suita, Japan), Masayuki Shima (Hyogo College of Medicine, Nishinomiya, Japan), Youichi Kurozawa (Tottori University, Yonago, Japan), Narufumi Suganuma (Kochi University, Nankoku, Japan), Koichi Kusuhara (University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Kitakyushu, Japan), and Takahiko Katoh (Kumamoto University, Kumamoto, Japan).

Funding

This study was funded by the Ministry of the Environment, Japan. The findings and conclusions of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the above government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

H.M. conceptualized and designed the study, analyzed the data, and drafted the initial manuscript. K.H., H.I., and H.K. contributed to the data analysis and interpretation and assisted in the preparation of the manuscript, giving critical advice. Y.K., H.G., and T.M. gave advice on the data analysis. A.S. and Y.O. collected the data. K.F., H.N., S.Y., M.H., and the JECS group reviewed the manuscript and gave critical advice. All of the authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript. All of the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Maeda, H., Hashimoto, K., Iwasa, H. et al. Association of cesarean section with asthma and atopic dermatitis in infants from the Japan Environment and Children’s Study. Sci Rep 15, 39700 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23252-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23252-z