Abstract

Curcuma kwangsiensis is a medicinal plant endemic to China with significant economic and medicinal value. In agricultural practice, it is typically harvested after one year of cultivation. However, continuous cropping has severely constrained the development of the C. kwangsiensis industry. To elucidate the effects of continuous cropping on the yield and rhizosphere soil environment, this study systematically investigated the effects of continuous cropping on C. kwangsiensis yield, rhizosphere soil physicochemical properties, enzyme activities, and microbial communities through field experiments. The results showed that continuous cropping significantly reduced C. kwangsiensis yield by 58.87%. It decreased soil pH while increasing the accumulation of soil nutrients including organic carbon, total nitrogen, total phosphorus, total potassium, available phosphorus, available potassium, and available nitrogen, but significantly decreased the activities of soil enzymes such as phosphatase, urease and catalase. Moreover, continuous cropping enhanced both the abundance and diversity of bacterial and microeukaryotic communities. It significantly increased the relative abundance of Planctomycetota, which became the dominant bacterial phylum, while also significantly increasing the relative abundances of the predominant microeukaryotic phyla Ciliophora and Cercozoa. Redundancy analysis revealed that pH was the most important factor affecting microbial community composition. Continuous cropping of C. kwangsiensis reduced soil pH, altered soil physicochemical properties and enzyme activities, and restructured microbial communities. The bacterial co-occurrence networks revealed a shift from a relatively compact and clustered structure at the initial stage to a larger and more complex network with continuous cropping, characterized by higher interaction density but reduced local clustering. The fungal networks shifted from a highly compact structure in Y0 to more expanded but less cohesive architectures in Y1 and Y2. SEM (Structural Equation Modeling) analysis shows that during continuous cropping, soil enzyme activity was the key influencing factor, which was closely related to microbial diversity and the availability of nitrogen and phosphorus, and there was a positive feedback effect. These changes collectively explain the yield reduction in C. kwangsiensis, providing a critical theoretical foundation for protecting its rhizosphere soil ecosystem and ensuring sustainable cultivation practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Curcuma kwangsiensis S. K. Lee et C. F. Liang is a natural species from south China, particularly in Guangxi, that has been used since ancient times. C. kwangsiensis is listed in the Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China1. Its bioactive compounds, such as curcuminoids and volatile oils, are widely used in the medicinal, food and cosmetic industries2. Moreover, its essential oils are considered as one of the most important bioactive constituents of C. kwangsiensis and have been reported to elicit diverse biological effects owing to their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antiviral and antitumor activities3. Given these significant economic and medicinal values, C. kwangsiensis is increasingly cultivated under intensive cropping systems. However, this has led to the emergence of severe continuous cropping obstacles, which now threaten the sustainable industrial development of this valuable medicinal plant4.

Continuous cropping can decrease the yield, quality and disease resistance of crops5. These obstacles to continuous cropping are typically observed in agricultural crops6,7. A total of 80–90% of medicinal plants are rhizomes, and there are serious continuous cropping obstacles in crops, such as Panax notoginseng, Rehmannia glutinosa, and Panax ginseng among others. Continuous cropping obstacles are attributed to a multitude of factors8. It is widely acknowledged that the primary causes of continuous cropping obstacles include: (1) deterioration of soil physicochemical properties, such as increased soil salinization and acidification, as well as nutrient imbalance; (2) autotoxicity induced by biologically inhibitory substances and the aggravation of soil-borne diseases; (3) alterations in the soil microbial community, characterized by an increase in harmful microorganisms and a decrease in beneficial microorganisms. The rhizosphere soil is directly affected by plant roots, and its microbial composition is closely related to the transformation and utilization of soil nutrients, which directly affects the growth of crops.

Previous studies on Amorphophallus konjac and Vanilla planifolia have revealed that continuous cropping can change the bacterial communities, which results in a decrease in the numbers of beneficial bacteria and an increase in the numbers of deleterious ones9,10. Moreover, the results of other study showed that after 3 years of continuous cropping of P. notoginseng, the diversity of bacteria decreased significantly. Compared with the diseased plants, the healthy P. notoginseng plants had a higher bacterial diversity within the soil rhizosphere. Furthermore, the bacterial community was most affected by the contents of phosphorus (P) and soil organic carbon (SOC) and the pH as shown by a canonical correspondence analysis11. In addition, a previous study revealed that the number of bacterial species and the diversities of the bacterial communities in the soil rhizospheres of goji berry (Lycium barbarum L.) and Sophora flavescens decreased significantly after continuous cropping12,13.

It has been shown that continuous cropping negatively impacts the microbial community structures in the soil rhizosphere of a wide range of crops. However, studies on the continuous cropping of C. kwangsiensis have mostly concentrated on disease and pest management, as well as the breeding of novel varieties14. No relevant studies have been reported, and the corresponding scientific questions remain unaddressed, including the effects of continuous cropping on the yield of C. kwangsiensis, soil physicochemical properties, and microbial community structure, as well as the interrelationships among these factors. Therefore, this study aims to: (1) investigate the impact of two-year continuous cropping on the yield of C. kwangsiensis and the associated changes in soil physicochemical properties; (2) characterize the structural and compositional shifts of the rhizosphere microbial communities using high-throughput sequencing technologies; (3) most importantly, integrate these datasets to unravel the complex interrelationships between soil characteristics and microbial communities, and to identify the key factors responsible for yield decline. Achieving these objectives is critical not only for elucidating the mechanistic basis of continuous cropping obstacles in this valuable medicinal plant, but also for developing targeted strategies to mitigate these obstacles and enable sustainable cultivation.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

The formal identification of C. kwangsiensis was performed by Professor Peng Yude of Guangxi Medicinal Plants of Botanical Garden. C. kwangsiensis is primarily propagated using rhizomes15. The planting procedure is as follows: shallow pits (10–13 cm in depth) are dug; 0.5 kg of well-decomposed organic fertilizer is applied per pit and mixed thoroughly with the soil; one rhizome is placed in each pit with the bud oriented upward; the pit is backfilled with soil to level the surface, and then thoroughly irrigated.

Study area description

A sampling site was set up in Qinzhou City, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, in the southwest of Lingshan County, China (22°17’40’’N, 108°53’43’’E), which is the Daodi production region of C. kwangsiensis. The selected research region was 40 m above sea level, with an average yearly temperature of 27 °C and 1600 mm of precipitation. The soil type was classified as laterite according to the FAO-UNESCO System of Soil Classification.

Experimental design and sample collection

The experiment began in 2022. C. kwangsiensis was planted in March and harvested on Novermber each year, and planted for two consecutive years. The width of the ridg is 120 cm and the height is 20 cm. The ridge distance was 30 cm, seedling spacing was 50 cm for two rows, length of the plot was 10 m. The area was 300 m2 and the each planting field was dicided into three sample plots. Management was the same as for the field. The fertilization design was formulated on the basis of previous laboratory research15. The amount of the fertilizer applied was 80 kg/ha of compound fertilizer (N-P-K = 15:15:15), 20 kg/ha of micronutrient fertilizer and 20 kg/ha of organic fertilizer. The fertilizer spread evenly on the plot, then turn into the soil. Y0 represents the soil samples before C. kwangsiensis platation in March 2022. Y1 and Y2 represent the soil samples collected after the first and second years of continuous monoculture of C. kwangsiensis plantation in Novermber 2022 and Novermber 2023, respectively.

Nine rhizosphere soil samples were collected from the sample plot using an S-sampling method and mixed as biological replicates. The soil rhizospheres of C. kwangsiensis plants were sampled using the method proposed by Edwards et al.16. The whole root of C. kwangsiensis was completely excavated with a sampling shovel and placed in sterile plastic bags after removing the topsoil, a 3–5 mm soil area around the C. kwangsiensis root (10–50 cm below the topsoil) was collected for each sample of soil rhizosphere. These samples immediately placed on ice for transport to the laboratory within a 5 h period. A portion of each sample was stored at 4℃ for analysis of soil physicochemical properties and enzyme activities. The remaining samples were stored at -80℃ for high-throughput sequencing analysis.

Yield measurement

The rhizomes and roots of C. kwangsiensis serve as the primary medicinal organs. To evaluate the yield, five plants were randomly sampled from each replicate plot of the Y1 and Y2 groups in November of each cultivation year (totaling 15 plants per treatment). Following removal of the aboveground parts, the fresh weights of rhizomes and roots were recorded and subsequently converted to yield per hectare (kg/ha).

Analysis of soil physicochemical properties and enzyme activities

Soil samples were air-dried and all soil chemical properties were determined based on their dry weights. The soil pH was determined using suspensions of the soil samples in water at a ratio of 1:2.5 (w/v) with a Mettler Toledo 320 pH meter (Delta 320; Mettler-Toledo Instruments Ltd., Shanghai, China). The soil organic carbon (SOC) was measured by using the K2Cr2O7-H2SO4 oxidation-reduction titration. The total nitrogen (TN) and available nitrogen (AN) concentration were determined by a FIAstar (FIAstar 5000 FOSS, Sweden Ltd.) according to the Kjeldahl method which employed the alkali-hydrolytic diffusion technique. The total phosphorus (TP) and available phosphorus (AP) were determined using the molybdenum antimony contrast method. Total potassium (TK) and available potassium (AK) were determined by the flame spectrophotometric method. Soil acid phosphatase (S_ACP), urease (S_UE), and catalase (S_CAT) activities were determined using commercial assay kits (Suzhou Grace Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Jiangsu, China) following the manufacturer’s protocols.

DNA extraction and amplicon sequencing

The soil samples were sent to Biomarker Technologies Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) for soil microbiome sequencing analysis. Soil DNA was extracted using the TGuide S96 Magnetic Soil/Stool DNA Kit (Tiangen Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) following the manufacturer’s protocol, and the DNA quality was subsequently assessed. The DNA concentration was quantified using a microplate reader (GeneCompany Limited, Synergy HTX), and the integrity was verified by electrophoresis on a 1.8% agarose gel (Beijing Biomarker Technologies Co., Ltd.). The full-length 16 S rRNA gene was amplified using the primers 27 F (5′-AGRGTTTGATYNTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492R (5′-TASGGHTACCTTGTTASGACTT-3′)17, while the full-length 18 S rRNA gene was amplified using the primers Euk-A (5’-AACCTGGTTGATCCTGCCAGT-3’) and Euk-B (5’-GATCCTTCTGCAGGTTCACCTAC-3’). The sequencing procedures were performed as previously described18. Ultimately, sequencing was conducted using the Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) Sequel IIe platform.

Microbial co-occurrence network analysis

The microbial co-occurrence networks were analyzed using the CoNet app (Cytoscape v3.9.1) to characterize their complexity and modularity. Robust correlations (Spearman’s |r| > 0.80, BH-adjusted p < 0.05) between OTUs were used to reconstruct networks, which were visualized and topologically characterized (e.g., nodes, edges, average degree, modularity) with Gephi 0.9.3. Nodes represent OTUs, and edges signify significant pairwise interactions.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the experimental data was performed using SPSS26.0 software (SPSS Inc., United States). Differences between two groups were assessed using an independent Student’s t-test, with significance denoted by asterisks (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). Differences among three or more independent groups were evaluated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). When the ANOVA result was significant (p < 0.05), post-hoc comparisons were conducted using the Waller-Duncan test, with significance indicated by different lowercase letters (p < 0.05). The bioinformatics analysis of this study was performed with the aid of the BMK Cloud (Biomarker Technologies Co., Ltd., Beijing, China, http://www.biomarker.com.cn/biocloud). A structural equation model (SEM) was constructed and analyzed using the plspm package in R (version 4.4.1) to assess the relationships between soil microbial communities and physicochemical properties.

Results

C. kwangsiensis yield

The effects of continuous cropping on C. kwangsiensis yield are shown in Fig. 1. Compared with Y1, the Y2 group showed a significant decrease in both the number of tuberous roots (Fig. 1A-B) and the weights of rhizomes and roots (Fig. 1C). Notably, the yield of Y2 was significantly lower than that of Y1, showing a 58.87% reduction (Fig. 1D). These results demonstrate severe yield limitation under continuous cropping regimes.

Soil physicochemical properties and enzyme activities

The soil physicochemical properties and enzyme activities showed significant variations among treatments (Table 1). Specifically, soil pH in both Y1 and Y2 was significantly lower than in Y0, with Y2 exhibiting the lowest pH value, indicating that continuous cropping intensified soil acidification. Concurrently, the contents of key nutrients, including SOC, TN, TP, TK, AN, AP, and AK, were significantly elevated in the second year (Y2) compared to Y0 and Y1, indicating a substantial accumulation of soil nutrients. In contrast, soil enzyme activities (S_ACP, S_UE, S_CAT) exhibited a distinct pattern of an initial increase in Y1 followed by a sharp decline in Y2. This pattern suggests that while short-term cropping (Y1) stimulates microbial activity and nutrient turnover, extended continuous cropping (Y2) may lead to a degradation of soil microbial function, potentially disrupting ecosystem processes and contributing to the observed obstacle.

Composition of the soil microbial community

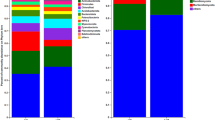

The read lengths for 16 S rRNA and 18 S rRNA sequencing were approximately 1,500 bp and 1,800 bp, respectively, generating total data outputs of approximately 109,070 bp and 118,148 bp. After the filter reads for basic quality control and the removal of single OTUs, 37,936 sequences were obtained from nine samples, including 785 OTUs (Fig. 2A). The lengths of high-quality sequences per sample ranged from 1439 to 1446 bp. The bacterial OTUs were assigned to 23 phyla, 37 classes and 217 genera. The dominant phyla across all the samples were Proteobacteria (26.89%), Verrucomicrobiota (18.34%), Acidobacteriota (16.72%), Chloroflexi (16.38%), Bacteroidota (8.93%), Plantctomycetota (4.34%) and Actinobacteriota (2.90%) (Fig. 2C). After the reads were filtered as described above, 71,297 sequences were obtained from nine samples, and the sequences were clustered into 207 OTUs (Fig. 2B). The lengths of these high-quality sequences per sample ranged from 1,748 to 1,760 bp. The microeukaryotic OTUs were assigned to 23 phyla, 57 classes and 166 genera. The dominant phyla were Basidiomycota (37.49%), Streptophyta (25.60%), Ciliophora (12.97%), Cercozoa (4.29%), Platyhelminthes (4.23%), Mucoromycota (3.41%), Nematoda (2.80%) and Arthropoda (2.79%) (Fig. 2D).

The continuous cropping of C. kwangsiensis induced the abundances of the bacterial and microeukaryotic communities in the soil rhizosphere (Fig. 2). The relative abundances of the different phyla in Y0, Y1 and Y2 were compared (see Supplementary Table S1 online). As shown in Fig. 2C, Y0 resulted in a significantly higher relative abundance of Chloroflexi, Actinobacteriota, Firmicutes and a significantly lower relative abundance of Proteobacteria and Bacteroidota in the dominant bacterial phyla (p < 0.05) compared with those of Y1 and Y2 (see Supplementary Table S1 online). Y2 resulted in a significantly higher relative abundance of Planctomycetota as the dominant bacterial phylum (p < 0.05) compared with Y0 and Y1 (see Supplementary Table S1 online). Y1 resulted in a significantly higher relative abundance of Armatimonadota as the dominant bacterial phylum (p < 0.05) compared with Y0 and Y2. Although there were small differences between the other dominant bacterial phyla, these differences were not significant (see Supplementary Table S1 online). The relative abundances of Ciliophora and Cercozoa as the dominant microeukaryotic phyla were significantly higher in Y2 when compared with those of Y0 and Y1. The relative abundances of Streptophyta and Mucoromycota as the dominant microeukaryotic phyla were significantly higher in Y1 compared with those of Y0 and Y2. The relative abundance of Basidiomycota in the dominant microeukaryotic phyla was significantly higher in Y0 when compared with those of Y1 and Y2 (Fig. 2D; Supplementary Table S2 online).

At the genus level, HSB_OF53_F07, Candidatus Xiphinematobacter, Acetobacter, C. Solibacter and Bradyrhizobium were the dominant bacterial genera, while Galerina, Liatris and Gymnopus were found to be dominant among the microeukaryotic genera (Fig. 2E-F). The proportions of genera, including HSB_OF53_F07, C. Xiphinematobacter, Galerina and Gymnopus, significantly decreased with the prevalence of continuous cropping (p < 0.05) (see Supplementary Table S3 online). However, the proportions of genera, including Tepidisphaera, ADurb.Bin063_1, Occallatibacter, Burkholderia_Caballeronia_Paraburkholderia, Gonostomum, Urostyla, Platyophrya and Oxytricha, increased dramatically (p < 0.05). In addition, the proportions of Acetobacter and Liatris first increased and then decreased (see Supplementary Table S4 online).

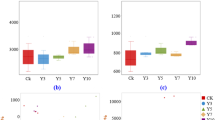

The soil microbial diversity

As shown in Fig. 3, the coverage rate > 96% for all the samples indicated that the depth of sequencing met the needs of the experiment. Except for the Simpson index of the bacteria, the other indices of bacteria and microeukaryotes were significantly higher for Y2 than for Y1 and Y0 (p < 0.05). These findings demonstrate that the diversity of bacteria and microeukaryotes was comparatively high in the Y2 as a result of continuous cropping.

The relationships between the multiple samples could be explained using a principal coordinate analysis (PCoA). The fact that each sample had three replicates and was grouped together suggests that this analysis accurately replicated the architecture of the bacterial and microeukaryotic communities (Fig. 4). A comparison of the three soil samples showed that the rate of contribution of the first principal component of the bacterial community to the sample difference was 51.44%, and that of the second principal component was 23.83% (Fig. 4A). The values for the microeukaryotic community were 50.20% and 30.72%, respectively (Fig. 4B). Based on the direction of the abscissa, the composition of the bacterial and microeukaryotic communities in Y0 could be distinguished from those of Y1 and Y2. With the increase in the time of continuous cropping, the distance between rhizosphere soil samples from different times became increasingly distant, which showed that with the increase of continuous cropping years, the bacterial and microeukaryotic community structure in the rhizosphere soil was disrupted by the continuous cropping of C. kwangsiensis.

Bacteria and microeukaryotic contributed to discrepancies in the community composition

It was confirmed that the microbial community composition in the soil rhizosphere was altered during the continuous cropping of C. kwangsiensis. A Linear discriminant analysis Effect size (LEfSe) was used to search for biomarkers to identify species with significant differences in abundance between the groups. In this study, an LEfSe analysis was used to analyze the data of the abundance of species of the microbial community in the rhizosphere soil samples. A rank sum test was used to detect varying species in different groups and linear discriminant analysis (LDA) scores. The default threshold on the logarithmic LDA score for discriminative features was set to 419. The results confirmed that there was a significant enrichment of Planctomycetota at the phylum level of bacteria and a significant decrease in Chloroflexi with the continuous cropping of C. kwangsiensis. At the genus level, G12_WMSP1, Granulicella, BacC_u_018, C. Xiphinermayobacter, Acidophil silvibacterium, HSB_OF53_F07, and G12_WMSP1 decreased, and Occallayibacter, Mucilaginibacter, Ellin516, Tepidisphaera and Occallaibacter increased (Fig. 5A). For the microeukaryotic phyla, Basidiomycota decreased, and Platyhelminthes increased. The genera Gonosyomum, Bodomorpha and Colpoda increased, while Gymnopus, Galerina and Dicranopteris decreased (Fig. 5B).

Effects of environmental factors on the microbial community

The results of a redundancy analysis (RDA) on the top 10 bacterial and microeukaryotic phyla and environmental factors of the three fields are shown in Fig. 6. Axis-1 and axis-2 represented 94.76% and 97.27% of the total variation in the bacteria and microeukaryotes, respectively. The RDA plot at the phylum level of microbial community indicated that the pH was the most important factor for the bacterial and microeukaryotic communities. The effects of soil properties on the bacterial and microeukaryotic community structure were as follows: pH > SOC > AK > AN > S_ACP. The results showed that the pH was the strongest predictors of the microbial community composition in the rhizosphere soil of continuous cropping C. kwangsiensis.

In addition, the results of a Spearman correlation coefficient analysis are shown in Fig. 7. For the bacterial community, the pH and S_ACP significantly positively correlated with Verrucomicrobiota, Chloroflexi, Actinobacteriota, Myxococcota, Armatimonadota and Firmicutes. The pH and S_ACP significantly negatively correlated with Proteobacteria, Acidobacteriota, Bacteroidota and Planctomycetota. The remaining indicators were inversely correlated with the corresponding bacterial communities. A similar pattern was observed in the microeukaryotic community. SOC and AK significantly positively correlated with Ciliophora, Cercozoa, Platyhelminthes and Arthropoda, while the SOC and AK significantly negatively correlated with Basidiomycota, Streptophyta, Mucoromycota, Ascomycota and Chlorophyta.

Microbial co-occurrence network analysis

The co-occurrence network analysis of the microbial community is shown in Fig. 8. The bacterial co-occurrence networks displayed clear differences across the three sampling stages. Network size and connectivity gradually increased, with 363 nodes and 1378 edges in Y0, 434 nodes and 1505 edges in Y1, and reaching 596 nodes and 3305 edges in Y2. Both positive and negative associations became more abundant over time, indicating that microbial interactions intensified and diversified. The average degree also increased from 7.59 (Y0) and 6.94 (Y1) to 11.09 (Y2), suggesting enhanced interconnectivity among taxa. In contrast, the clustering coefficient declined from 0.354 in Y0 to 0.310 in Y2, while average path length and diameter increased, reflecting that the networks expanded in scale but became less locally aggregated. Overall, these results reveal a shift from a relatively compact and clustered structure at the initial stage to a larger and more complex network at later stages, characterized by higher interaction density but reduced local clustering.

The fungal co-occurrence networks showed marked structural variation across the three stages. In Y0, the network was relatively small but extremely dense, comprising 66 nodes and 670 edges, with an average degree of 20.30, a short path length (1.76), and a high clustering coefficient (0.725), indicating a compact and highly interconnected community. By contrast, the Y1 and Y2 networks expanded in node number (134 and 130, respectively) while maintaining similar edge counts (~ 700), resulting in reduced density (0.078–0.083) and lower clustering compared with Y0. Both Y1 and Y2 exhibited longer average path lengths (2.93 and 2.78) and larger diameters (7 and 6), suggesting looser connectivity and less tightly clustered associations. The balance of positive and negative interactions remained stable across stages (~ 370 vs. ~320), indicating that cooperative and competitive relationships co-occurred consistently. Overall, the fungal networks shifted from a highly compact structure in Y0 to more expanded but less cohesive architectures in Y1 and Y2.

SEM analysis

The results of the structural equation model are shown in Fig. 9. The goodness-of-fit index was 0.81, indicating a satisfactory overall fit of the model to the data. Enzymatic activity had a significant negative impact on Shannon diversity, suggesting that higher enzyme levels correspond to lower microbial diversity, potentially due to the suppression of other microbial groups by dominant enzyme-producing taxa. Shannon diversity exhibited a highly significant positive effect on SOC, implying that greater microbial diversity enhances the decomposition/sequestration processes, thereby increasing SOC content. This model elucidates the complex relationships among soil pH, enzymatic activity, microbial diversity, and the availability of soil carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium: (1) enzymatic activity served as a key mediator, significantly influencing microbial diversity and the availability of nitrogen and phosphorus; (2) microbial diversity was identified as a core driver of SOC, playing a critical regulatory role in the soil carbon pool; (3) significant interactions were observed among soil nutrients, particularly the negative effects of SOC on AK and of AP on AK, reflecting trade-offs in soil nutrient supply.

Discussion

Effects of continuous cropping on the yield and physicochemical properties of the soil ehizosphere of C. kwangsiensis

The prospect of growing a single crop on the same piece of land for 3 years or more will lower crop production and is commonly understood to be a continuous cropping obstacle20. Nevertheless, the reasons behind this practice remain incompletely understood because crops differ from one another21. Traditional continuous monocultures will cause a number of issues, including the accumulation of autotoxic chemicals, disruption of the soil microbial communities, and the deterioration of the physical and chemical qualities of the soil, as well as a decrease in the activities of soil biological enzymes22. These will eventually lead to the decline of crop yields and the quality of plants, and it can also reduce their resistance to disease.

The continuous cropping of C. kwangsiensis has been shown to severely decrease its yield in this study. This general phenomenon has also been found to occur in other Chinese traditional medicinal plants, such as Panax notoginseng, Chinese aconite (Aconitum carmichaeli) and Rehmannia glutinosa19,23,24. With the increase in continuous cropping years, many of the essential components needed by crops will be reduced in the soil, while the elements that are not absorbed by crops will be enhanced, which will cause an imbalance in the soil nutrients8. In this study, the levels of SOC, TP, TK, AN, AP, and AK in the soil increased, while the activities of S_CAT, S_ACP and S_UE in the soil increased at first and then decreased with the increase in continuous cropping years. Similarly, an earlier study demonstrated the increased levels of certain elements during the continuous cropping periods, such as those of P and K during the continuous cropping of Chinese goldthread (Coptis chinensis)25. This study found a considerable reduction in pH, which is one of the soil physicochemical qualities that is widely acknowledged as essential to the sustainability of crops. This is most likely to be related to the diminished capacity of soil to assimilate the exchange in cations following the continuous cropping process. A decrease in pH also indicates soil acidification, which is one of the primary causes of continuous cropping obstacles. This observation is consistent with findings from other studies, which reported that continuous cropping of Pogostemon cablin and Codonopsis pilosula significantly reduced soil pH26,27.

Venn diagram of bacterial (A) and microeukaryote (B) OTUs for the soil samples. Relative abundance of bacterial community (C) and microeukaryote community (D) at the phylum level. Relative abundance of bacterial community (E) and microeukaryote community (F) at the genus level. Y0, Y1, and Y2 represent planting years of 0, 1, and 2 years, respectively. OTUs, operational taxonomic units.

The diversity of bacterial communities, including OTU (A), ACE (B), Chao1 (C), Simpson (D) and Shannon indexes (E). The diversity of microeukaryotic communities, including OTU (F), ACE (G), Chao1 (H), Simpson (I) and Shannon indexes (J). Y0, Y1, and Y2 represent planting years of 0, 1, and 2 years, respectively. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) taxonomic cladogram identified significantly discriminant bacterial (A) and microeukaryotic (B) taxa (LDA > 4) in the rhizosphere soil of Curcuma kwangsiensis. Y0, Y1, and Y2 represent planting years of 0, 1, and 2 years, respectively. LDA, linear discriminant analysis.

Heatmap of the correlation between 10 dominant bacterial (A) and microeukaryotic (B) phyla and the soil physiochemical properties. S_ACP: Phosphatase activity; SOC: soil organic carbon; AN: available nitrogen; TN: total nitrogen; AP: available phosphorus; TP: total phosphorus; AK: available potassium.

Microbial co-occurrence network analysis. (A) Bacterial community and (D) microeukaryotic community in the Y0 group; (B) Bacterial community and (E) microeukaryotic community in the Y1 group; (C) Bacterial community and (F) microeukaryotic community in the Y2 group. Y0, Y1, and Y2 represent planting years of 0, 1, and 2 years, respectively.

Structural equation model illustrating the relationships between pH, Enzymatic activity (CAT and ACP), Microbial diversity, and AN, AK, AP, SOC in the continuous cropping of Curcuma kwangsiensis. Red arrows indicate positive path coefficients, and blue arrows indicate negative path coefficients. (***: p < 0.001; **: p < 0.01; *: p < 0.05).

Effects of continuous cropping on the microbial diversity in the soil rhizosphere of C. kwangsiensis

The dynamic balance of the microbial community, a crucial component of soil ecology, is essential to the growth of C. kwangsiensis. Here, the microbial community structure and diversity of three soil samples was examined, as well as the variation in rhizosphere microorganisms in the soils with the different continuous years. The essential basis to control the distribution of the soil microbial community during the C. kwangsiensis planting process was provided by clarification of the effects of continuous cropping on the species and the relative abundance of soil microorganisms.

After years of continuous cropping, the management strategy remained mostly unchanged, which caused the soil environment to shift in one direction. The number of deleterious microorganisms increased, while the number of beneficial microorganisms decreased yearly, thus, ultimately destroying the level of healthy soil28. This study found that the alpha-diversity of bacteria and microeukaryotes was Y2 > Y1 > Y0. Wang et al. showed that the continuous cropping obstacles of many crops were related to changes in the microbial community structure and composition in the soil7. The results of this study showed that continuous cropping had a considerable impact on the diversity and organization of the soil microbial communities in the three soil samples. A study found that the Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi (AMFs) can serve as a biological indicator of improved soil fertility, whereas an increase in the prevalence of fungi in the soil is a sign of deteriorating soil fertility29. Another study found that the continuous cropping of soybean (Glycine max) led to variation in the soil microbial community, which was also observed in this study30.

At the phylum level, a total of five dominant phyla were identified (relative abundance > 8%), and the relative abundance of these in the three soil samples differed significantly (p < 0.05). Significantly greater relative abundances of Chloroflexi, Firmicutes and Actinobacteriota were observed in Y0 when compared with Y1 and Y2. The material transformation and decomposition of plant residues facilitated by Chloroflexi were essential for the circulation of materials in the soil since they promoted nutrient circulation and preserved the ecological balance of the soil. Firmicutes consists of a broad spectrum of biocontrol bacteria31. The proportions of HSB-OF53-F07 significantly decreased with the continuous cropping (p < 0.05), and HSB-OF53-F07 was proved to promte plant growth32. It was hypothesized that the prevalence of soilborne disease that occurred after the continuous cropping of C. kwangsiensis was owing to the abundance of biocontrol bacteria in Y1 and Y2. For example, many actinomycetes serve as biocontrol organisms that can prevent numerous soilborne diseases of C. kwangsiensis. These can produce secondary metabolites to inhibit the growth of pathogenic bacteria and induce C. kwangsiensis to produce defensive enzymes to enhance its resistance to bacterial pathogens33. It has been hypothesized that the continuous planting of C. kwangsiensis can lead to a decrease in the relative abundance of these species, which will lead to an imbalance in the microecology of the soil34. Proteobacteria are beneficial for soil health, regulating rhizosphere pH and promoting microbial diversity35. They also play crucial roles in soil nitrogen cycling and disease suppression27. Compared to the Y1 group, the reduced abundance of Proteobacteria in the Y2 group may impair key soil functions such as organic matter decomposition and nitrogen cycling, as many Proteobacteria are involved in nitrification and denitrification processes. The decline in beneficial Proteobacteria (e.g., antibiotic-producing Pseudomonas species) could diminish the natural biocontrol capacity of the soil, thereby facilitating the proliferation of soil-borne pathogens. In contrast, the increased abundance of Planctomycetota may reflect a shift in resource availability. Some Planctomycetota are known for their unique anaerobic ammonium oxidation capabilities36, suggesting an alteration in the nitrogen cycle under continuous cropping stress.

Basidiomycetes is the primary fungal group in the soil and serves to maintain the stability of soil microecology37. Therefore, we deduced that the decrease in the relative abundance of Basidiomycota was a reason for the occurrence of soilborne diseases of C. kwangsiensis. The relative abundances of Ciliophora and Cercozoa were higher in Y2. Thus, these organisms may contain a pathogen that can cause a soilborne disease of C. kwangsiensis.

By using LDA of effect size in a LEfSe study, significant differences were observed between the bacterial and microeukaryotic communities obtained from the three samples. The number of Chloroflexi in Y2 decreased significantly, while that of Planctomycetota was significantly enriched. These results were consistent with the analysis of relative abundance. The PCoA showed that the consistent cultivation of C. kwangsiensis altered the bacterial and microeukaryotic community structures of the soil. The results indicated that the three replicates of each sample were grouped together, and the bacterial and microeukaryotic communities in the three samples had significantly distinct compositions and structures.

The correlation between specific microbial communities and soil physicochemical properties can provide information on how the microbial community composition affects the cycling of soil nutrients. In this study, the results of the RDA showed that the pH was the most important factor that affected the microbial community structure. The soil pH is closely related to the availability of nutrients to microorganisms38. Bacteria can effectively use amino acids and carbohydrates and have a wider metabolic capacity at higher pH values39. A decrease in the pH will lead to a decrease in bacterial diversity because most bacterial groups have poor tolerance to growth39. In contrast, many deleterious fungi thrive in a low pH environment40. In addition, the bacterial community members Proteobacteria, Bacteroidota and Planctomycetota significantly negatively correlated with the pH, while Chloroflexi, Actinobacteria and Firmicutes significantly positively correlated with the pH. Basidiomycota and Chlorophyta significantly positively correlated with the pH, while Ciliophora and Cercozoa significantly negatively correlated with the pH. These results further supported the results of microbial community succession. Therefore, the changes in soil physicochemical properties caused by continuous cropping may be the primary factor that drives the success of microbial community and may also be one of the primary reasons that hinders the continuous cropping of C. kwangsiensis.

This study represents the first report on continuous cropping obstacles in C. kwangsiensis. Continuous cropping of C. kwangsiensis for two years significantly reduced its yield. It is therefore worthwhile to further investigate the effects of three years, four years, or even longer continuous cropping, in order to comprehensively analyze the impact of both short-term and long-term monoculture on the yield of C. kwangsiensis and to elucidate the underlying mechanisms. Furthermore, as this study was conducted as a field trial, subsequent research will incorporate pot or micro-plot experiments to enable accelerated validation and enhance the reliability of the conclusions. Based on the research outcomes, including those related to soil physicochemical properties and microbial communities, further studies will be undertaken to explore strategies for mitigating or eliminating continuous cropping obstacles in C. kwangsiensis.

Conclusion

This study revealed that continuous cropping reduced the yield of C. kwangsiensis while decreasing soil pH and significantly increasing the levels of SOC, TN, TP, TK, AN, AP, and AK in the rhizosphere soil. However, the activities of soil enzymes including S_ACP, S_UE, and S_CAT were significantly inhibited. In comparison to Y1 and Y0, the composition, structure, and diversity of bacterial and microeukaryotic communities in Y2 became more diverse. RDA analysis showed that pH was the most significant factor affecting bacterial and microeukaryotic communities at the phylum level. Proteobacteria, Bacteroidota, and Planctomycetota were significantly negatively correlated with pH, while Chloroflexi, Firmicutes, and Actinobacteriota were positively correlated with pH. Basidiomycota showed a significant positive correlation with pH, whereas Ciliophora and Cercozoa were significantly negatively correlated. Consequentially, continuous cropping of C. kwangsiensis reduced soil pH, altered the physicochemical properties and enzyme activities of rhizosphere soil, and disrupted the original soil microecological balance, which may be one of the important reasons for the yield decline under continuous cropping. The outcomes discussed above establish a theoretical foundation for the conservation and enhancement of the soil ecological environment, as well as the future sustainable development of the C. kwangsiensis industry.

Data availability

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

References

Zeng, J. H. et al. Application of the chromatographic fingerprint for quality control of essential oil from GuangXi Curcuma Kwangsiensis. Med. Chem. Res. 18 (2), 158–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00044-008-9115-2 (2008).

Amalraj, A. et al. Biological activities of curcuminoids, other biomolecules from turmeric and their derivatives - A review. J. Tradit Complement. Med. 7 (2), 205–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcme.2016.05.005 (2017).

Schramm, A. et al. Phytochemical profiling of Curcuma Kwangsiensis rhizome extract, and identification of labdane diterpenoids as positive GABAA receptor modulators. Phytochemistry 96, 318–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2013.08.004 (2013).

Guo, L. et al. Effects of continuous cropping on bacterial community and siversity in rhizosphere soil of industrial hemp: A five-year experiment. Diversity 14 (4), 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14040250 (2022).

Sun, K. N. et al. Effects of continuous cucumber cropping on crop quality and soil fungal community. Environ. Monit. Assess. 193 (7), 436. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-021-09136-5 (2021).

Dong, L. L. et al. Soil bacterial and fungal community dynamics in relation to Panax Notoginseng death rate in a continuous cropping system. Sci. Rep. 6, 31802. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep31802 (2016).

Wang, K. G. et al. A review of research progress on continuous cropping Obstacles. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 11 (2), 253–270. https://doi.org/10.15302/j-fase-2024543 (2024).

Zhao, X. Y. et al. Using Biochar for the treatment of continuous cropping obstacle of herbal remedies: A review. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 193, 105127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2023.105127 (2024).

Wu, J. P. et al. Analysis of bacterial communities in rhizosphere soil of continuously cropped healthy and diseased Konjac. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 33 (7), 134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11274-017-2287-5 (2017).

Xiong, W. et al. Different continuous cropping spans significantly affect microbial community membership and structure in a vanilla-grown soil as revealed by deep pyrosequencing. Microb. Ecol. 70 (1), 209–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-014-0516-0 (2015).

Bao, L. M. et al. Interactions between phenolic acids and microorganisms in rhizospheric soil from continuous cropping of Panax Notoginseng. Front. Microbiol. 13, 791603. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.791603 (2022).

He, M. Y. et al. Effects of continuous cropping on the physiochemical properties, pesticide residues, and microbial community in the root zone soil of Lycium barbarum. Huan Jing Ke Xue. 45 (9), 5578–5590. https://doi.org/10.13227/j.hjkx.202311078 (2024).

Liu, S. et al. Traditional Chinese medicine residues promote the growth and quality of Salvia miltiorrhiza bunge by improving soil health under continuous monoculture. Front. Plant. Sci. 14, 1112382. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1112382 (2023).

Li, Z. Y. et al. Research progress of Curcuma Kwangsiensis root tubers and analysis of liver protection and anti-tumor mechanisms based on Q-markers. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 47 (7), 1739–1753. https://doi.org/10.19540/j.cnki.cjcmm.20211220.203 (2022).

Wu, Q. H. et al. Technical code of practice for pollution-free production of Curcuma. Mod. Chin. Med. Res. Pract. 26 (02), 3–4. https://doi.org/10.13728/j.1673-6427.2012.02.003 (2012).

Edwards, J. et al. Structure, variation, and assembly of the root-associated microbiomes of rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 112 (8), E911–E920. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1414592112 (2015).

Guo, L. N. et al. Microorganisms that are critical for the fermentation quality of paper mulberry silage. Food Energy Secur. 10 (4), e304. https://doi.org/10.1002/fes3.304 (2021).

Guo, J. et al. Fulvic acid modified ZnO nanoparticles improve nanoparticle stability, mung bean growth, grain zinc content, and soil biodiversity. Sci. Total Environ. 913, 169840. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.169840 (2024).

Fei, X. et al. Variations of microbial community in Aconitum Carmichaeli Debx. Rhizosphere Soilin a short-term continuous cropping system. J. Microbiol. 59 (5), 481–490. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12275-021-0515-z (2021).

Gao, Z. Y. et al. Effects of continuous cropping of sweet potato on the fungal community structure in rhizospheric soil. Front. Microbiol. 10, 2269. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.02269 (2019).

Zhao, Y. et al. Effects of continuous cropping of Pinellia Ternata (Thunb.) Breit. On soil physicochemical properties, enzyme activities, microbial communities and functional genes. Chem. Biol. Technol. Ag. 8 (1), 43. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40538-021-00243-6 (2021).

Pervaiz, Z. H. et al. Continuous cropping alters multiple biotic and abiotic indicators of soil health. Soil. Syst. 4 (4), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems4040059 (2020).

Xiang, W. et al. Autotoxicity in Panax Notoginseng of root exudatesand their allelochemicals. Front. Plant. Sci. 13, 1020626. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.1020626 (2022).

Liu, Y. Z. et al. Intercropping with Achyranthes bidentata alleviates Rehmannia glutinosa consecutive monoculture problem by reestablishing rhizosphere microenvironment. Front. Plant. Sci. 13, 1041561. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.1041561 (2022).

Alami, M. M. et al. Structure, function, diversity, and composition of fungal communities in rhizospheric soil of Coptis chinensis Franch under a successive cropping system. Plants 9 (2), 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9020244 (2020).

Ul Haq, M. Z. et al. Continuous cropping of Patchouli alleviate soil properties, enzyme activities, and bacterial community structures. Plants 13 (24), 3481. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13243481 (2024).

Li, H. L. et al. Effects of continuous cropping of Codonopsis pilosula on rhizosphere soil microbial community structure and metabolomics. Agronomy. 14(9), (2014). https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy14092014 (2024).

Ma, Y. H. et al. Variation of microflora and enzyme activity in continuous cropping cucumber soil in solar greenhouse. Ying Yong Sheng Tai Xue Bao. 15 (6), 1005–1008 (2004).

Fall, A. F. et al. Roles of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on soil fertility: contribution in the improvement of physical, chemical, and biological properties of the soil. Front. Fungal Biol. 3, 723892. https://doi.org/10.3389/ffunb.2022.723892 (2022).

He, D. X. et al. Effects of continuous cropping on fungal community diversity and soil metabolites in soybean roots. Microbiol. Spectr. 11 (6), e0178623. https://doi.org/10.13227/j.hjkx.202311078 (2023).

Baard, V. et al. Biocontrol potential of Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus tequilensis against four Fusarium species. Pathogens 12 (2), 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens12020254 (2023).

Ding, J. Y. M. et al. Impact of sterilization and chemical fertilizer on the microbiota of oil palm seedlings. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1091755. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1091755 (2023).

Kim, Y. S. et al. Antagonistic effect of Streptomyces sp. BS062 against Botrytis diseases. Mycobiology 43 (3), 339–342. https://doi.org/10.5941/myco.2015.43.3.339 (2015).

Bandara, T. et al. The effects of Biochar aging on rhizosphere microbial communities in cadmium-contaminated acid soil. Chemosphere 303 (Pt 2), 135153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.135153 (2022).

Cui, F. Y. et al. Effects of cotton peanut rotation on crop yield soil nutrients and microbial diversity. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 28072. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75309-0 (2024).

Kündgen, M. et al. Substrate utilization and secondary metabolite biosynthesis in the phylum Planctomycetota. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 109 (1), 123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-025-13514-1 (2025).

Sivanandhan, S. et al. Biocontrol properties of basidiomycetes: an overview. J. Fungi (Basel). 3 (1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof3010002 (2017).

Li, H. Y. et al. Nutrients available in the soil regulate the changes of soil microbial community alongside degradation of alpine meadows in the Northeast of the Qinghai-Tibet plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 792, 148363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148363 (2021).

Zhalnina, K. et al. Soil pH determines microbial diversity and composition in the park grass experiment. Microb. Ecol. 69 (2), 395–406. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-014-0530-2 (2015).

Prusky, D. & Yakoby, N. Pathogenic fungi: leading or led by ambient pH? Mol. Plant. Pathol. 4 (6), 509–516. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1364-3703.2003.00196.x (2003).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on this study. The work was supported by Guangxi Appropriate Technology Development and Promotion Project for Traditional Chinese Medicine (No. GZS2025003), Guangxi Key Research and Development Program (No. Guike AB25069170), and Guangxi Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine Project (No. GXZY20220003).

Funding

The research was funded by Guangxi Appropriate Technology Development and Promotion Project for Traditional Chinese Medicine (No. GZS2025003), Guangxi Key Research and Development Program (No. Guike AB25069170), and Guangxi Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine Project (No. GXZY20220003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yuan Huang and Zhi-gang Yan wrote the main manuscript text; Zhi-gang Yan and Shu-gen Wei contributed to the methodology; Yuan Huang performed formal analysis; Wei Lin conducted the investigation; Kun-fa Gan curated the data; Yuan Huang and Li-jun Shi prepared the original draft; Zhan-jiang Zhang reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, Y., Gan, Kf., Lin, W. et al. Continuous cropping alters rhizosphere microbial communities and soil properties reducing Curcuma Kwangsiensis yield. Sci Rep 15, 39668 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23318-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23318-y