Abstract

To explore missed nursing care activities and possible reasons in adult intensive care units in mainland China. A descriptive study. ICU nurses were recruited by convenience sampling between August 2023 and October 2023. They were asked to complete the missed intensive nursing care scale (MINCS) consisted in three parts (Basic information of participants, missed care elements in ICU and reasons for missing). Data analysis was conducted through descriptive, univariate and multivariate analyses. We followed the RANCARE guideline and STROBE checklist when reporting this study. A total of 550 registered nurses participated in this study. The total scores for missed nursing care items in ICU ranged from 38 to 167 points, with an average item score of (1.79 ± 0.72). Nursing activities related to satisfy patients’ physiological and emotional needs were most frequently missed. The scores for the causes of such omissions ranged from 23 to 92 points, with an average item score of (2.44 ± 0.81). Nurse professional burnout, inadequate human resource allocation, and insufficient competence were the most commonly reported reasons by ICU nurses. Moreover, nurses’ gender and job title were found to be associated with MNC in the ICU (p < 0.001).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Missed nursing care (MNC), an error of omission defined by Kalisch (2009) as “any aspect of required patient care that is omitted (either in part or in whole) or delayed”1. This phenomenon, also described as implicit rationing of nursing care, unfinished nursing care, unmet nursing needs, etc. has been a hot topic in the field of patient safety and nursing care quality over the past two decades2. Evidence of missed nursing care has surfaced in various healthcare settings, including hospitals3,4, communities5,6,7, and nursing homes8,9,10.

Despite its varied descriptions, the adverse impacts of missed nursing care on patients, nurses, and organizations are undeniable. MNC poses a serious threat to patient safety11, and contributes to adverse outcomes such as pressure ulcers, increased mortality, falls, and nosocomial infections. Simultaneously, it leads to negative nurse outcomes, including a higher level of burnout and resignation, and lower job satisfaction12. Additionally, the organizational consequences encompass increased economic costs due to prolonged hospital stays and a tarnished hospital reputation resulting from patient adverse events13.

Nurses, as the primary caregivers, are dedicated to delivering high-quality care services to address diverse patient needs14. However, despite these efforts, MNC occurs due to a variety of complex reasons, leading to the omission or delay of necessary nursing interventions15. Studies have identified the most frequently missed elements crucial for meeting patients’ fundamental physiological needs, such as turning, ambulation, feedings, and hygiene16. Interestingly, Lili Saar et al. highlighted that giving emotional care was frequently omitted, underscoring the multifaceted nature of MNC17. Prior research suggests that care tasks prone to omission are those requiring extended time, collaboration, and not posing an immediate threat to patients’ lives18,19. Moreover, while studies have identified unmet nursing needs from the patient’s perspective, a comprehensive investigation into all aspects of patient needs is still lacking20. A systemic review conducted by Bagnasco revealed that the identified unmet nursing needs from the perspective of patients were congruent with nurses’ perceptions, suggesting the feasibility of investigating MNC from the point of nurses21. However, at the same time, the investigation of the satisfaction extent of patient needs in previous studies is not comprehensive enough, and further exploration is needed.

The association between MNC and factors such as inadequate labor resources, nursing staff characteristics, work environment, and managerial style further complicates the picture22,23. In times of low manpower, nurses have no choice but to complete those higher priority nursing tasks such as drug administration, condition monitoring, so those with psychological care, health education, etc., are at risk of being left undone.

Despite extensive research in various clinical departments, such as pediatrics24, cardiology departments25, oncology wards26, Postanesthesia Care Unit27, labor and delivery units28 and neonatal intensive care units29, the occurrence of MNC in adult intensive care units (ICUs) remains underexplored30,31,32. Critically ill patients in ICUs face unique challenges due to communication and mobility restrictions, making it imperative to investigate and address MNC to enhance nursing service quality, improve patient experiences, and prevent adverse events33,34.

However, the occurrence of MNC in adult ICUs in Mainland China remains underexplored. Investigating MNC within this specific context is critical due to unique factors such as the structure of the Chinese healthcare system, distinct nursing workforce challenges, and cultural nuances in patient care expectations, which may differentially influence the prevalence and reasons for MNC compared to other international settings. Therefore, this study aims to bridge this research gap through a cross-sectional design, examining the occurrence and factors associated with MNC in adult ICUs in China.

Methods

Study design

A multi-center, cross-sectional descriptive study design was employed in this study.

Setting and sample

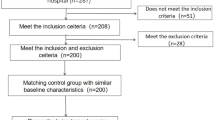

Convenience sampling was used to recruit nurses currently working in adult ICUs. Hospitals were invited to participate through the research team’s professional networks. We aimed to include a variety of hospitals from different geographical regions to enhance diversity. The final sample comprised comprehensive secondary and tertiary hospitals located in several provinces and municipalities, including Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Hubei, and Zhejiang, representing Southwest, Central, and Eastern China. Nurses from these hospitals were invited to participate between August and October 2023. Secondary hospitals were defined as those with 100 to 500 beds, while tertiary hospitals had a capacity of more than 500 beds. Inclusion criteria for nurses were: (1) registered nurses with a minimum of six months’ experience in adult ICUs, a criterion set to ensure participants had adequate familiarity with the full scope of ICU care practices to reliably report on missed care; and (2) informed consent and voluntary participation. Exclusion criteria included: (1) trainee nursing students; (2) individuals absent from work for personal reasons for half a year or more. The sample size is 5 to 10 times the number of questionnaire items. Considering the dropout rate of 10%, at least 336 subjects were required.

Ethical consideration

The study obtained ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University (Date: 6 September 2022, Number: 2022 − 151). We promised that the survey was completed anonymously, and that the personal information of the subjects was kept confidential, and that the informed consent was obtained before they answered the questionnaire. All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Measures

The Missed Intensive Nursing Care Scale (MINCS) was adopted to measure MNC in adult ICUs. This scale was selected for its unique value in providing a theoretically grounded and context-specific assessment. Unlike generic tools, the MINCS is structured around Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, enabling a holistic evaluation of omissions across five domains: Physiological, Safety, Emotional, Esteem, and Cognitive needs. Furthermore, its items are specifically tailored to the adult ICU environment, capturing care activities critical for critically ill patients. The tool comprised three parts:

-

i.

Part A with 13 items collecting basic demographic characteristic of respondents (e.g., age, gender, work years, and educational level).

-

ii.

Part B with 38 items and five domains evaluating the frequency of MNC during the fulfillment of five categories of ICU patient needs (Physiological, safety, emotional, esteem, and cognitive needs). Participants used a Likert 5 scale, ranging from “Never” (1) to “Always” (5), with higher scores indicating more MNC. Nurses could choose “Not applicable” for certain activities.

-

iii.

Part C includes 23 items and four domains (labor resources, material resources, communication and managerial factors), explaining possible reasons for omitted care. A Likert 4 scale from “significant factors” (4), ‘‘moderate factor’’, ‘‘minor factor,’’ to ‘‘not a reason for unmet nursing care’’ (1) was used. The self-designed MINCS was partially adapted from the original MISSCARE Survey35 but was significantly developed and validated for the ICU context.

Data collection

Data were collected from August to October 2023, with nurses completing the MINCS distributed on Questionnaire Star, an online electronic platform widely used in China.

Data analysis

Prior to data analysis, a rigorous data cleaning process was conducted, excluding invalid questionnaires that either selected all answer options uniformly or were completed in less than 1 min. Descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, and ranges, were employed to analyze the basic information of the participants. The total score of Part B and Part C was calculated, along with the average score for each item. The relationship between nurse demographic variables and scores of subscale B was assessed using one-way analysis of variance (univariate analysis). Further, multiple linear regression analysis was performed for variables that demonstrated statistical significance, with a significance level set at p < 0.05. Responses of “occasionally”, “often”, and “always” were defined as missed, and the missing rate was calculated accordingly. Responses indicating “not applicable” were excluded from the analysis, as they did not reflect the prevalence of missed nursing care36. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 25.0.

Validity and reliability/rigour

The MINCS underwent a comprehensive scale development process, incorporating the Delphi expert consultation method, item analysis, and psychometric property testing. The scale demonstrated high credibility, evidenced by a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.94. Additionally, the Scale Content Validity Index (S-CVI) values were 0.988 for Part B and 0.977 for Part C, further attesting to the validity of the instrument in measuring missed nursing care in ICUs.

Results

Demographic characteristics of participants

In total, 752 questionnaires were distributed among eligible nurses, with 550 samples deemed valid and included in the analysis. Among them, 97 (17.6%) were men and 453 (82.4%) were women. The majority, 475 (86.4%), held a bachelor’s degree. 95.1% respondents were staff nurses, serving as direct caregivers to patients. All participants were employed in secondary or higher-level hospitals. 162 (29.5%) possessed critical nurse certificate; Over half of the participants (58.9%) reported working over 40 h per week. Detailed demographic information is presented in Table 1.

Elements of nursing that are frequently missed

309 nurses (56.2%) reported MNC at least one of the 38 nursing care items during their last working shift. The study revealed that the total score of the MINCS ranged from 38 to 167 points, with an average score of 67.94 ± 27.17 points. The average score for each item is 1.79 ± 0.72. Dimensions 1 to 5, representing physiological needs-related nursing, safety needs-related nursing, emotional needs-related nursing, respect needs-related nursing, and cognitive needs-related nursing, respectively, had scores of 2.13 ± 0.96, 1.57 ± 0.74, 1.9 ± 0.91, 1.78 ± 0.84, and 1.81 ± 0.84. These scores suggest that the frequency of MNC in the ICU is predominantly at the level of “rarely” and “occasionally”. Table 2 provides detailed information on the top five and last five items, offering insights into the specific nursing care activities that are more frequently or less frequently missed by ICU nurses.

Reasons for missed nursing care reported by ICU nurses

The reported causes of missed nursing care in the ICU ranged from 23 to 92, with the average score of Part C being 56.11 ± 18.69. The average score for each item was 2.44 ± 0.81. The four dimensions—human resources, material resources, communication, and management—had scores of 2.59 ± 0.92, 2.38 ± 0.92, 2.49 ± 0.92, and 2.39 ± 0.87, respectively. These scores provide insights into the perceived reasons behind missed nursing care, categorized across different dimensions.

Table 3 outlines the specific conditions associated with the first five and last five items, shedding light on the particular aspects of nursing care that are reported more frequently or less frequently as reasons for omission by ICU nurses.

The association of nurses’ characteristics to MINCS

Significant differences were observed among the sociodemographic characteristics of ICU nurses in relation to the scores of gender, age, professional title, position, and shift system across the five dimensions of the MINCS. The specific results, presented in Table 4, highlight variations in MINCS scores among different groups of nurses. To further explore the factors influencing the lack of ICU care, multiple linear regression analysis was conducted using the total score of each dimension of missing ICU care and the statistically significant items identified in the univariate analysis as independent variables. The results, detailed in Table 5, revealed that gender and professional title emerged as significant factors affecting the occurrence of missed nursing care in the ICU.

Discussion

This study investigated MNC among 550 ICU nurses in China. While 56.2% reported omitting at least one care task during their last shift, the overall frequency was relatively low (mean item score: 1.79), occurring “rarely” to “occasionally.” This finding is consistent with studies suggesting that ICUs may experience less MNC compared to general wards37,38, possibly due to higher nurse-to-patient ratios and the critical nature of the unit. The most cited reasons for MNC were burnout, labor resource issues (both quantity and quality), and communication problems.

The use of the MINCS, grounded in Maslow’s theory, provided a nuanced understanding, revealing that missed care disproportionately affects higher-level patient needs (emotional, esteem, cognitive), which are often overlooked by task-oriented tools. This underscores the value of a theoretically framed, ICU-specific instrument.

Our results align with the global pattern that care related to physiological needs (e.g., thirst management, nutritional support evaluation) is most frequently missed39. The complexity of certain tasks, requiring specialized knowledge (e.g., interpreting nutritional indices), coupled with external constraints like limited family visitation40,41 which hampers communication, likely contributes to these omissions. In contrast, safety-related care (e.g., patient identification, risk assessment) was least missed, reflecting its non-negotiable priority in the ICU environment42,43, where life-saving measures take precedence.

The significant omission of care addressing emotional, esteem, and cognitive needs highlights a gap in holistic care delivery. Nurses often prioritize urgent physiological and safety tasks over psychological support or cognitive stimulation due to high workload44. This is concerning, as such omissions can contribute to delirium and impair patient outcomes45,46. Respecting patient autonomy and privacy47are also integral to quality care, and their missed nature calls for strategies to better integrate holistic practices into the ICU routine.

The perceived reasons for MNC underscore systemic issues. Burnout and job dissatisfaction critically impair nurses’ capacity to complete care48. Similarly, inadequacies in human resources (staff numbers, skill mix) and interprofessional communication are well-documented barriers49. This suggests that nursing managers need to take valid measures to control the quality of nursing from these two aspects, to ensure the safety of patients50. Our article also verified that communication problems are responsible for the missed care51. Teamwork is crucial to the recovery of patients in ICU, and almost all medical treatment require the cooperation of doctors and nurses42. It should be pointed out that, in Part C, respondents were asked to choose the extent to which these reasons contribute to MNC and does not mean that this is the current situation of the department. For example, the respondents had the highest score for the item related to burnout, which does not represent their have high-level of burnout, but they think this is the main reason for MNC, and their extent of burnout is only known through extra investigation.

Analysis of demographic factors revealed significant associations. Nurses’ gender and job title were associated with MNC, with men showing higher scores in the dimension of safety-related care, in line with other literature52, which may be related to women being more attention to detail and more sensitive to the importance of safety care. But this result contradicts the findings of Diab’s study53 that women reported the highest level of MNC than men. However, some studies did not find a relationship between gender and MNC42,54. Therefore, it is crucial to examine the impact of gender variable on the MNC in the future. Nurses with higher professional titles report more MNC table in this study, which may be that nursing staff with higher professional titles face more pressure and responsibility, and can keenly detect management problems related to nursing quality55. So nursing managers should actively engage senior nurses through structured channels (e.g., quality circles) to identify and address systemic failures proactively.

Limitation

Nurses’ self-reported methods may have a reporting bias that will have an impact on the results56. However, the tool of this study involves the investigation of the multi-aspect needs of patients, which can comprehensively assess the status of MNC. Additionally, the cross-sectional study design allows us to reserve this question when making causal inference. Last, this study rarely describes the hospital characteristics, so in the next, the influence of the hospital features except the size of the hospital towards MNC needs exploring. It is also suggested more studies used objective evaluation method, with a large sample to be conducted in the ICU.

Conclusion

This study investigated the occurrence and reasons of MNC among Chinese adult intensive care units, enriched the research in this field, although the results showed nursing activities remain rarely missed, there are still requirements for further improvement, and practice of holistic care should be attached importance to satisfy patients’ various needs.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to concerns regarding the privacy of research participants but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- GICU:

-

General intensive care unit

- MICU:

-

Medicine intensive care unit

- SICU:

-

Surgical intensive care unit

- EICU:

-

Emergency intensive care unit

- RICU:

-

Respiratory intensive care unit

- NICU:

-

Neurological intensive care unit

References

Kalisch, B. J., Landstrom, G. L. & Hinshaw, A. S. Missed nursing care: a concept analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 65 (7), 1509–1517 (2009).

Jones, T., Drach-Zahavy, A., Sermeus, W., Willis, E. & Zelenikova, R. Understanding missed care: definitions, measures, conceptualizations, evidence, prevalence, and challenges. In Impacts of Rationing and Missed Nursing Care: Challenges and Solutions: RANCARE Action (eds Papastavrou, E. & Suhonen, R.) 9–47 (Springer International Publishing, 2021).

Gurková, E., Mikšová, Z. & Šáteková, L. Missed nursing care in hospital environments during the covid-19 pandemic. Int. Nurs. Rev. 69 (2), 175–184 (2022).

Simonetti, M., Cerón, C., Galiano, A., Lake, E. T. & Aiken, L. H. Hospital work environment, nurse staffing and missed care in chile: a cross-sectional observational study. J. Clin. Nurs. 31 (17–18), 2518–2529 (2022).

Andersson, I., Bååth, C., Nilsson, J. & Eklund, A. J. A scoping review—missed nursing care in community healthcare contexts and how it is measured. Nurs. Open. 9 (4), 1943–1966 (2022).

Phelan, A., McCarthy, S. & Adams, E. Examining missed care in community nursing: a cross section survey design. J. Adv. Nurs. 74 (3), 626–636 (2018).

Senek, M. et al. Nursing care left undone in community settings: results from a Uk cross-sectional survey. J. Nurs. Manag. 28 (8), 1968–1974 (2020).

Ludlow, K. et al. Unfinished care in residential aged care facilities: an integrative review. Gerontologist 61 (3), e61–e74 (2021).

Renner, A. et al. Increasing implicit rationing of care in nursing homes: a time-series cross-sectional analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 134, 104320 (2022).

Zhang, H., Peng, Z., Chen, Q. & Liu, W. A cross-sectional study of implicit rationing of care in publicly funded nursing homes in shanghai, China. J. Nurs. Manag. 30 (1), 345–355 (2022).

Kalánková, D. et al. Missed, rationed or unfinished nursing care: a scoping review of patient outcomes. J. Nurs. Manag. 28 (8), 1783–1797 (2020).

Stemmer, R. et al. A systematic review: unfinished nursing care and the impact on the nurse outcomes of job satisfaction, burnout, intention-to-leave and turnover. J. Adv. Nurs. 78 (8), 2290–2303 (2022).

Janatolmakan, M. & Khatony, A. Explaining the consequences of missed nursing care from the perspective of nurses: a qualitative descriptive study in Iran. BMC Nurs. 21 (1), 59 (2022).

Feo, R., Kitson, A. & Conroy, T. How fundamental aspects of nursing care are defined in the literature: a scoping review. J. Clin. Nurs. 27 (11–12), 2189–2229 (2018).

Cartaxo, A., Dabney, B. W., Mayer, H., Eberl, I. & Gonçalves, L. External influencing factors on missed care in Austrian hospitals: testing the theoretical antecedents of missed care using structural equation modelling. J Adv. Nurs (2023).

Zeleníková, R., Jarošová, D., Polanská, A. & Mynaříková, E. Implicit rationing of nursing care reported by nurses from different types of hospitals and hospital units. J. Clin. Nurs. 32 (15–16), 4962–4971 (2023).

Saar, L., Unbeck, M., Bachnick, S., Gehri, B. & Simon, M. Exploring omissions in nursing care using retrospective chart review: an observational study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 122, 104009 (2021).

Abdelhadi, N., Drach Zahavy, A. & Srulovici, E. The nurse’s experience of decision-making processes in missed nursing care: a qualitative study. J Adv. Nurs (2020).

Papastavrou, E., Andreou, P. & Vryonides, S. The hidden ethical element of nursing care rationing. Nurs. Ethics. 21 (5), 583–593 (2014).

Mandal, L., Seethalakshmi, A. & Rajendrababu, A. Rationing of nursing care, a deviation from holistic nursing: a systematic review. Nurs. Philos. 21(1), e12257 (2020).

Bagnasco, A. et al. Unmet nursing care needs on medical and surgical wards: a scoping review of patients’ perspectives. J. Clin. Nurs. 29 (3–4), 347–369 (2019).

Chiappinotto, S. et al. Antecedents of unfinished nursing care: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Nurs 21(1) (2022).

Zárate-Grajales, R. A. et al. Sociodemographic and work environment correlates of missed nursing care at highly specialized hospitals in mexico: a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 126, 104140 (2022).

Ogboenyiya, A. A., Tubbs-Cooley, H. L., Miller, E., Johnson, K. & Bakas, T. Missed nursing care in pediatric and neonatal care settings: an integrative review. MCN Am. J. Matern Child. Nurs. 45 (5), 254–264 (2020).

Wagner-Łosieczka, B. et al. The variables in the rationing of nursing care in cardiology departments. BMC Nurs 22(1) (2023).

Vryonides, S. et al. Ethical climate and missed nursing care in cancer care units. Nurs. Ethics. 25 (6), 707–723 (2018).

Kiekkas, P. et al. Missed nursing care in the postanesthesia care unit: a cross-sectional study. J. PeriAnesthesia Nurs. 36 (3), 232–237 (2021).

Lake, E. T., French, R., O’Rourke, K., Sanders, J. & Srinivas, S. K. Linking the work environment to missed nursing care in labour and delivery. J. Nurs. Manag. 28 (8), 1901–1908 (2020).

Smith, J. G., Rogowski, J. A. & Lake, E. T. Missed care relates to nurse job enjoyment and intention to leave in neonatal intensive care. J. Nurs. Manag. 28 (8), 1940–1947 (2020).

Nymark, C., Falk, A. C., von Vogelsang, A. C. & Göransson, K. E. Differences between registered nurses and nurse assistants around missed nursing care-an observational, comparative study. Scand J. Caring Sci (2023).

von Vogelsang, A. C., Göransson, K. E., Falk, A. C. & Nymark, C. Missed nursing care during the covid-19 pandemic: a comparative observational study. J. Nurs. Manag. 29 (8), 2343–2352 (2021).

Wieczorek Wojcik, B., Gaworska Krzemińska, A., Owczarek, A. J. & Kilańska, D. In-hospital mortality as the side effect of missed care. J. Nurs. Manag. 28 (8), 2240–2246 (2020).

Xiao, L., Zhang, C. L. & Ling, S. Y. Nurses’ perceptions of communication needs of patients on mechanical ventilation. [J]. J. Nurs. Sci. 36 (14), 85–87 (2021).

Xiong, J., Wang, H. & Deng, J. A review of care needs of conscious critically ill patients in ICU[J]. J. Nurs. Sci. 33 (13), 105–109 (2018).

Kalisch, B. J. & Williams, R. A. Development and psychometric testing of a tool to measure missed nursing care. J. Nurs. Adm. 39 (5), 211–219 (2009).

Pereira, L. S. R. et al. Omission of nursing care, professional practice environment and workload in intensive care units. J. Nurs. Manag. 28 (8), 1986–1996 (2020).

Bragadóttir, H., Kalisch, B. J. & Tryggvadóttir, G. B. Correlates and predictors of missed nursing care in hospitals. J. Clin. Nurs. 26 (11–12), 1524–1534 (2017).

Campbell, C. M. et al. Variables associated with missed nursing care in alabama: a cross-sectional analysis. J. Nurs. Manag. 28 (8), 2174–2184 (2020).

Chen, F., Jiang, Z. X. & Yang, M. J. A study on the perceptions and behaviors of ICU nursing staff on thirst in mechanically ventilated patients in Guizhou Province [J]. Chin. J. Nurs. 58 (09), 1104–1111. https://doi.org/10.3761/j.issn.0254-1769.2023.09.012 (2023).

Bauer, P. R., Rabinstein, A. A. & Wilson, M. E. Family visitation policies in the Icu and delirium. JAMA 322 (19), 1923–1924 (2019).

Palese, A. et al. Depicting clinical nurses’ priority perspectives leading to unfinished nursing care: a pilot q methodology study. J. Nurs. Manag. 28 (8), 2146–2156 (2020).

Nobahar, M., Ameri, M. & Goli, S. The relationship between teamwork, moral sensitivity, and missed nursing care in intensive care unit nurses. BMC Nurs 22(1) (2023).

Vincelette, C., D’Aragon, F., Stevens, L. & Rochefort, C. M. The characteristics and factors associated with omitted nursing care in the intensive care unit: a cross-sectional study. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 75, 103343 (2023).

Shi, F., Li, Y. & Zhao, Y. How do nurses manage their work under time pressure? Occurrence of implicit rationing of nursing care in the intensive care unit: a qualitative study. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 75, 103367 (2023).

Barr, J. et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit. Care Med. 41 (1), 263–306 (2013).

Nørbæk, J. & Glipstrup, E. Delirium is seen in one-third of patients in an acute hospital setting. Identification, Pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic treatment is inadequate. Dan Med. J 63(11) (2016).

Sun, X., Zhang, G., Yu, Z., Li, K. & Fan, L. The meaning of respect and dignity for intensive care unit patients: a meta-synthesis of qualitative researches. Nurs Ethics, 1548508858 (2023).

Nantsupawat, A., Wichaikhum, O. A., Abhicharttibutra, K., Sadarangani, T. & Poghosyan, L. The relationship between nurse burnout, missed nursing care, and care quality following covid-19 pandemic. J. Clin. Nurs. 32 (15–16), 5076–5083 (2023).

Zeleníková, R., Jarošová, D., Mynaříková, E., Janíková, E. & Plevová, I. Inadequate number of staff and other reasons for implicit rationing of nursing care across hospital types and units. Nurs. Open. 10 (8), 5589–5596 (2023).

McCauley, L., Kirwan, M., Riklikiene, O. & Hinno, S. A scoping review: the role of the nurse manager as represented in the missed care literature. J. Nurs. Manag. 28 (8), 1770–1782 (2020).

He, M. et al. Exploring the role of communication in missed nursing care: a systematic review. J Adv. Nurs (2022).

Arslan, G. G., Özden, D., Göktuna, G. & Ertuğrul, B. Missed nursing care and its relationship with perceived ethical leadership. Nurs. Ethics. 29 (1), 35–48 (2022).

Diab, G. & Ebrahim, R. M. R. Factors leading to missed nursing care among nurses at selected hospitals. Am. J. Nurs. Res. 7 (2), 136–147 (2019).

Młynarska, A., Krawuczka, A., Kolarczyk, E. & Uchmanowicz, I. Rationing of nursing care in intensive care units. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 17 (19), 6944 (2020).

Kalisch, B. J. & Xie, B. Errors of omission: missed nursing care. West. J. Nurs. Res. 36 (7), 875–890 (2014).

Vincelette, C., Thivierge-Southidara, M. & Rochefort, C. M. Conceptual and methodological challenges of studies examining the determinants and outcomes of omitted nursing care: a narrative review of the literature. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 100, 103403 (2019).

Funding

This research has not received any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Y. made substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; L.Y. and L.L. Involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content; X. G. give final approval of the version to be published. L.Y., L.L. and X.H. agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, L., Liu, L., Hu, X. et al. Prevalence and reasons for missed nursing care in adult intensive care units. Sci Rep 15, 39712 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23369-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23369-1