Abstract

α-Glucosidase inhibitors are widely used in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) by delaying carbohydrate digestion and reducing postprandial blood glucose levels. However, current drugs suffer from limited efficacy and gastrointestinal side effects, highlighting the need for novel inhibitors with improved potency and selectivity. In this study, a novel series of 5,7-diaryl-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-6-amines 9a-9t was designed and prepared through an efficient, straightforward synthetic route. Subsequently, they were evaluated for their α-glucosidase inhibitory activity, with compound 9s exhibiting the most potent inhibition (IC50 = 24.32 ± 0.18 µM), outperforming acarbose by over 30-fold. Enzyme kinetics revealed a competitive inhibition mode, and selectivity assays confirmed minimal α-amylase inhibition. Spectroscopic analyses (CD and fluorescence) demonstrated significant conformational changes in α-glucosidase upon ligand binding, suggesting structural stabilization and reduced flexibility. Molecular docking and 200-ns MD simulations confirmed persistent hydrophobic and halogen-bond interactions, particularly with residues Phe303, Arg315, and Gln182. Additionally, a BERT-based deep learning model with SMILES augmentation accurately predicted the biological activity of synthesized compounds, validating our computational pipeline. These findings highlight [1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidines as promising scaffolds for the development of selective and potent α-glucosidase inhibitors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The inability of pancreas to produce insulin or dysfunctionality of the body to use insulin leads to hyperglycemia, which is an abnormally high level of sugar in the blood1. This condition, known as diabetes mellitus, can result in a range of serious damages, including macrovascular complications (cardiovascular disease), and microvascular complications (such as diabetic kidney disease, diabetic retinopathy and neuropathy). These severe outcomes significantly lead to increase the risk of mortality, blindness, and kidney failure, which decrease the life quality in diabetic patients2,3,4. Additionally, the fast-growing rate of diabetes prevalence across the world is concerning; according to the World Health Organization (WHO), 693 million adults will suffer from this illness by 2045. Therefore, diabetes mellitus has identified as one of the major global health crises in the 21st century5.

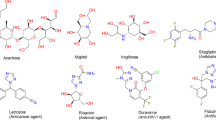

Among different types of diabetes mellitus, type 2 (T2DM) is the most common (more than 90% of all cases)6. One of the most used approaches to treat this subtype is the inhibition of α-glucosidase, an enzyme located and activated in the epithelium of the small intestine. Regarding its responsibility to hydrolyze the disaccharide and oligosaccharide substrates into absorbable monosaccharides, inhibiting this enzyme can help reduce glucose level in the bloodstream7,8,9. There are several approved α-glucosidase inhibitors, including, acarbose, voglibose, and miglitol, to treat the T2DM in the clinic; however, their undesirable side effects and absorption problems, particularly gastrointestinal disturbances, impede their efficacy10. Accordingly, significant efforts have been made to introduce and improve more potent α-glucosidase inhibitors with more favorable pharmacological profile and reduced toxicity.

Various aza-heterocyclic compounds have already demonstrated antidiabetic activity through α-glucosidase inhibition11,12,13,14,15. For instance, numerous studies have emphasized the importance of triazole-based frameworks, particularly 1,2,4-triazoles, when fused or incorporated with other nitrogen-containing heterocycles, as promising structural motifs for the development of α-glucosidase inhibitors. This may be attributed to their great potencies to form the crucial enzyme–ligand interactions, such as hydrogen bonds and π–π stacking16. Several molecular hybrids incorporating 1,2,4-triazoles with azinane A17, indole B18, thiazolidinone C19, pyridine D20, and quinoxaline E21 have already been reported as potential α-glucosidase inhibitors (Fig. 1). Along with these advancements, triazole-pyrimidine based compounds have also emerged as valuable inhibitors, as the integration of these two privileged structures within a single framework, such as 1,2,4-triazolopyrimidines, may result in enhanced binding affinity and inhibitory efficacy.

Among different isomers of 1,2,4-triazolopyrimidines, [1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine is the most extensively studied due to its unique structural features and remarkable stability. Compounds bearing this pharmacophore have been shown to possess a wide range of biological and pharmaceutical activities and several are commercially used in medicinal and agricultural chemistry22,23,24,25. Despite the wide investigations of [1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine-based compounds in diverse biological contexts, their antidiabetic potential evaluation—particularly through the inhibition of α-glucosidase (compounds F-H)26,27,28, α-amylase (compound I)29, dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-4) (compound J)30, and glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3) (compound K)31— has been investigated only in a limited number of studies (Fig. 2). Therefore, the development of new derivatives based on this scaffold represents a valuable and promising research endeavor in this field.

As part of our ongoing efforts to identify novel scaffolds with potential α-glucosidase inhibitory activity32,33,34,35,36, we synthesized a new series of [1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine derivatives 9, which subsequently were subjected to comprehensive biological evaluations, including in vitro α-glucosidase and α-amylase inhibitory assays, enzyme kinetics, circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy, and fluorescence spectroscopy. Moreover, in silico studies, including machine learning-based prediction models, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulations, were conducted to reveal their biological potency and binding interactions.

Results and discussion

Chemistry

According to the literature, [1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidines are typically synthesized using three main precursors: 1H-1,2,4-triazol-3-amine, 2-hydrazineylnicotinic acid, substituted 2,3-diaminopyrimidin-4(3H)-one, among which 1H-1,2,4-triazol-3-amine is the most frequently employed. This nucleophilic adduct went through the condensation with appropriate bifunctional electrophilic systems such as diethyl 2-(ethoxymethylene) malonate, α, β-unsaturated carbonyls and nitriles, 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds, ethyl 3-aryloxirane-2-carboxylate, as well as condensation with aldehydes and active methylenes, to prepare the desired triazolopyrimidine scaffold37,38,39.

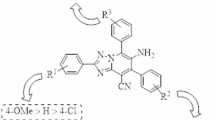

In present study, we described an innovative, straightforward route involving Michael addition-cyclization between α-azidochalcones 7 and 1H-1,2,4-triazol-3-amine 8 to yield novel derivatives of [1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidines 9. Notably, vinyl azides have recently emerged as powerful and versatile synthons in organic synthesis to afford a wide range of biologically active nitrogen-containing heterocycles40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47.

As outlined in Scheme 1, the synthetic approach toward the target 5,7-diaryl-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-6-amines 9 began with the preparation of various α-azidochalcone derivatives 7. Initially, condensation reactions between different arylaldehydes 1 and 1-(aryl)ethan-1-ones 2 were carried out to construct the chalcone backbone, which was subsequently subjected to olefin bromination. The resulting intermediates then underwent nucleophilic substitution with sodium azide, followed by elimination of hydrogen bromide (HBr) to yield the corresponding α-azidochalcones 7. Finally, the reaction between compounds 7 and 1H-1,2,4-triazol-3-amine 8 occurred smoothly to afford the desired multi-substituted [1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine derivatives 9.

To prove the generality of this protocol and expand the substrate scope, various arylaldehydes 1 and 1-(aryl)ethan-1-ones 2 were used, including thiophene, unsubstituted phenyl, and phenyl rings bearing either electron-donating groups (EDGs) (like methyl or methoxy) or electron-withdrawing groups (EWGs) (like chlorine or bromine). As a result, a broad series of triazolopyrimidines 9a-9t was synthesized. The structures of the obtained compounds were fully characterized using IR, 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy, high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS), and elemental analysis. Partial assignments of these resonances are given in the Experimental Part.

On accordance with previous literature, α-azidochalcones 7 went through the Michael addition-cyclization in the presence of bi-nucleophilic adducts, followed by removal of a nitrogen and a water, to produce the desirable nitrogen-containing compounds48. The similar route took place in present study between α-azidochalcones 7 and 1H-1,2,4-triazol-3-amine 8, confirming by characterization analysis. For instance, the data for compound 9s is representative:

Its IR spectrum showed two absorption peaks at 3368 and 3235 cm− 1 for NH2 group. The HRMS spectrum of this compound exhibited the molecular ion peak in positive mode ([M+ + H]+) at m/z 356.0459, which was 46.0167 mass units less than the sum of the masses of corresponding α-azidochalcones 7 and 1H-1,2,4-triazol-3-amine 8 in the ratio of 1 : 1, which is consistent with the loss of one molecule of nitrogen (N2, -28.0061) and one molecule of water (H2O, -18.0106) during the reaction, thereby confirming the proposed pathway. The 1H NMR spectrum of triazolopyrimidine 9s displayed a broad signal around δ 3.79 ppm for NH2 group and a sharp singlet band at δ 8.33 ppm assigned to the proton on the C-2 position of [1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine backbone. Moreover, four doublet peaks with the appropriate chemical shifts and coupling constants were appeared for eight aromatic H-atoms of the two aryl rings in the range of 7.55 to 7.88 of spectrum. The 13C NMR spectrum of this compound exhibited 13 distinct peaks in the suitable chemical shifts, which was in complete agreement with the desirable molecular symmetry of the proposed structure. The spectral data for other newly synthesized compounds 9 consistently supported their structures.

In vitro α-glucosidase inhibitory activity

Our biological studies on a novel series of 5,7-diaryl-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-6-amines 9 began with evaluating their in vitro inhibitory potential against Saccharomyces cerevisiae α-glucosidase. In this study, acarbose was used as standard reference drug. Our primary results revealed that all the triazolopyrimidines 9a-9t showed good to excellent activities (with IC50 values ranging from 24.32 ± 0.18 µM to 151.32 ± 0.56 µM in comparison with the reference drug (with an IC50 value of 750.08 ± 0.48 µM). The results are summarized in Table 1. To provide a comprehensive structure and activity relationship (SAR), the triazolopyrimidines were divided into four groups considering the substituents on the Ar1: (1) unsubstituted; (2) 4-Me substituted; (3) 4-OMe substituted; (4) 4-Cl substituted phenyl ring. To obtain an optimized α-glucosidase inhibitory potency, the substituents on the Ar2 ring was changed in each category.

In the first series, compound 9a with an unsubstituted phenyl ring as Ar2 possessed a moderate inhibitory activity (IC50 = 97.02 ± 0.83 µM). Introducing either an EDG (OMe) or an EWG (like Cl or Br) at the C-4 position of Ar2 enhanced the inhibitory potency of this pharmacophore (as seen in compounds 9b (IC50 = 70.85 ± 0.27 µM), 9c (IC50 = 56.21 ± 0.68 µM), and 9f (IC50 = 65.09 ± 0.38 µM)). Despite the beneficial presence of 4-Cl on Ar2, moving this atom to the C-3 or C-2 positions of this phenyl ring caused a detrimental effect, which might be related with steric hindrance. Comparing compound 9 g with compound 9a, replacing the phenyl ring with thiophene resulted in a significant reduction in inhibitory potency (IC50 = 139.78 ± 1.55 µM).

Across the second series, there was almost similar trend about the role of substituents on the Ar2. Comparing compounds in this group with their corresponding analogue in the first series revealed that introducing 4-Me on Ar1 did not lead to any improvement on the α-glucosidase inhibitory potency. This can be mechanistically explained by the methyl group’s pure electron-donating nature and its potential to introduce minor steric clashes. The active site pocket accommodating Ar1 seemed to be electrostatically tuned such that increased electron density from EDGs like methyl could not favor binding. Furthermore, the small but significant steric bulk of the methyl group might prevent the aryl ring from achieving an optimal deep fit within its sub-pocket.

The presence of a 4-OMe group on this ring in group 3 enhanced the triazolopyrimidine backbone potential to inhibit the enzymatic activity. For example, compound 9 m with an IC50 value of 72.36 ± 0.98 µM demonstrated superior potency than that of compounds 9a and 9 h with IC50 values of 97.02 ± 0.83 µM and 94.52 ± 0.72 µM, respectively. Moreover, introducing an EDG (4-OMe) or an EWG (4-Cl) on Ar2 led to further improvement on inhibition potency, as compounds 9n and 9o possessed IC50 values of 52.66 ± 0.30 µM and 37.18 ± 0.23 µM, respectively. A general comparison of the compounds in this group with their analogues in the previous groups revealed that the presence of OMe improved the inhibitory activities. Its oxygen atom could serve as a hydrogen bond acceptor in the enzyme’s active site. This potential for a favorable polar interaction could offset the negative electronic effects, leading to an overall enhancement in the binding affinity compared to the methyl-substituted or unsubstituted analogues.

Following the modification of substituents on the Ar1, introducing 4-Cl on this phenyl ring increased the inhibitory potency of triazolopyrimidines in group 4, as compound 9q showed better inhibition potency with IC50 value of 58.11 ± 0.34 µM in comparison with its analogues (compounds 9a (IC50 = 97.02 ± 0.83 µM), 9 h (IC50 = 94.52 ± 0.72 µM), and 9 m (IC50 = 72.36 ± 0.98 µM)). Same as previous series, the presence of 4-OMe and 4-Cl helped to enhance the triazolopyrimidine scaffold to inhibit α-glucosidase activity. As can be seen, compounds 9r and 9s exhibited the IC50 values of 41.48 ± 0.56 µM and 24.32 ± 0.18 µM, respectively.

In conclusion, the SAR analysis revealed that inhibitory potency was highly influenced by the electronic nature and precise position of substituents on both aryl rings. The presence of OMe as an EDG or Cl and Br as an EWG at the para position of both Ar1 and Ar2 improved the inhibitory activity in comparison with their unsubstituted analogues, suggesting that the binding pocket accommodating these phenyl rings was likely sensitive to the electron density of the ligand. This can be rationalized by the fact that EWGs helped to improve the activity by increasing the compound’s electrophilicity and forming favorable halogen-bonding interactions with electron-rich regions of the enzyme (such as carbonyl backbones), while EDGs might enhance van der Waals interactions. The presence of chlorine atoms on both phenyl rings in compound 9s exerted the remarkable synergistic effect to maximize hydrophobic interactions and potentially form dual halogen bonds, leading to a significant increase in binding affinity and inhibitory potency.

Moreover, the presence of chlorine atom at the C-2 or C-3 positions had destructive enzymatic effects. It can be contributed with the binding pocket for the Ar2 ring is sterically constrained. The presence of substituents at meta or ortho positions caused a torsional twist or increased steric bulk, preventing this ring from to locate in the optimal coplanar conformation for binding and disrupting key interactions with the enzyme’s active site.

Furthermore, the substitution of Ar2 with a thiophene moiety consistently yielded the least potent derivatives, as reflected by the highest IC50 values. This could be attributed to differences in electronic distribution, bond angles, and reduced planarity compared to the phenyl ring, which may disrupt essential π-π stacking or hydrophobic interactions within the binding site. Therefore, this heterocycle was not a suitable bioisostere for the phenyl ring to inhibit α-glucosidase.

Overall, 5,7-bis(4-chlorophenyl)-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-6-amine 9s (with IC50 value of 24.32 ± 0.18 µM) emerged as the most potent inhibitory activity against α-glucosidase, which was 30.84 times superior than that of acarbose (with IC50 value of 750.08 ± 0.48 µM). Therefore, it was selected for further biological evaluations, including kinetic study to find its inhibition mode, α-amylase inhibition potency to investigate its selectivity, as well as CD and fluorescence spectroscopy measurements to study its potential to alter the secondary and tertiary α-glucosidase’s structure.

α-Glucosidase kinetic study

The α-glucosidase activity in the presence of various concentrations of substrate p-nitrophenyl α-D-glucopyranoside (1–4 mM) along with various concentrations of triazolopyrimidine 9s (0, 6, 12, 24, and 48 µM). Subsequently, the Lineweaver–Burk plot (Fig. 3A) and the plot between the reciprocal of the substrate concentration (1/[S]) and reciprocal of enzyme rate (1/V) over various inhibitor concentrations (Fig. 3B) were outlined to determine the inhibition mode and the Michaelis–Menten constant (Km) value, respectively. As shown in Fig. 3A, increasing the concentration of triazolopyrimidine 9s led to a gradual increase in Km, while Vmax remained unchanged, indicating a competitive mode of inhibition. This suggests that compound 9s competes with the substrate for binding to the active site of α-glucosidase. Furthermore, Fig. 3B shows that the inhibition constant (Ki) of triazolopyrimidine 9s is 24 µM.

In vitro α-amylase inhibitory activity

Selective inhibition of α-glucosidase, without affecting α-amylase activity, is of significant therapeutic value in discovery and development of antidiabetic agents to treat T2DM. α-Glucosidase catalyzes the final step of carbohydrate digestion by hydrolyzing the oligosaccharides and disaccharides into absorbable glucose units at the intestinal brush border. However, α-amylase catalyzes the initial step of polysaccharide breakdown like starch in the upper gastrointestinal tract. Although inhibition of α-amylase may contribute to reduced glucose absorption, it often leads to gastrointestinal side effects, including bloating, cramping, and diarrhea, due to the accumulation of undigested carbohydrates in the colon and their subsequent fermentation by gut microbiota. Therefore, selective α-glucosidase inhibitors are generally more favorable for effective glycemic control and long-term T2DM therapy in clinical use49.

The in vitro α-amylase inhibitory activity of the targeted [1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-6-amines 9a-9t was evaluated and the results are summarized in Table 2. The assay was conducted at a concentration of 100 µM to provide a direct comparison with the standard drug acarbose, which exhibited 50.10 ± 0.5% inhibition under the same conditions.

Notably, the majority of the synthesized triazolopyrimidines demonstrated negligible inhibition against α-amylase. Moreover, seven derivatives (9a, 9d, 9e, 9 g, 9 L, 9p) showed no detectable activity (0% inhibition), while a further eight compounds (9b, 9 h, 9i, 9 m, 9q, 9r, 9t, 9n) exhibited only minimal inhibition, ranging from 2.14% to 8.38%, indicating the noticeable contrast to their potent activity against α-glucosidase (IC50 values ranging from 24.32 to 151.32 µM, Table 1) and confirming their high selectivity for the α-amylase. Among all tested compounds, 9o and 9s—which were also the most potent α-glucosidase inhibitors—showed the highest α-amylase inhibition, at 26.74 ± 0.32% and 23.2 ± 0.9%, respectively. However, even for these top performers, the inhibition remained substantially lower than that of acarbose.

In vitro α-amylase inhibitory activity assessment demonstrated that at a concentration of 100 µM [1,2,4], triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-6-amine 9s and acarbose inhibited α-amylase activity up to 23.2 ± 0.9% and 50.1 ± 0.5%, respectively. These results suggest that, despite the excellent α-glucosidase inhibitory potency of compound 9s, further structural modifications on this backbone may be necessary to enhance higher selectivity over α-amylase and optimize its potency.

Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy measurements

The difference between the absorption of right and left circular polarized light is measured to identify the chiral environment around aminoacids residues and study the changes in the secondary enzyme structures induced by inhibitors. In this study, the CD spectrum was recorded in the far UV region ranged from 190 nm to 240 nm, and then analyzed using CDNN software to compare the conformations of α-glucosidase-triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine 9s complex with native enzyme. There are several conformations, including α-helix, β-sheet, β-turn, and random coils. As presented in Table 3, CD spectroscopy analysis revealed a significant conformational change in α-glucosidase upon interaction with compound 9s. The secondary structure transitioned from a predominantly disordered state (60% random coil, 0% α-helix) to a highly ordered structure (41.2% α-helix, 51.4% β-turn). The CD spectroscopy results indicate that triazolopyrimidine 9s stabilizes the secondary structure of α-glucosidase, likely by inducing α-helical folding and reducing the enzyme’s conformational flexibility—structural changes that may contribute to the inhibition of its catalytic activity.

Fluorescence spectroscopy measurements

Fluorescence spectroscopy measurements were applied to find better insights into the mechanism through which compounds affect the tertiary structures of enzyme, leading to inhibit its activity. Triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine 9s at different concentrations (0, 10, 15, 20, and 25 µM) was added to the 3.0 mL solution containing a fixed amount of α-glucosidase. The steady-state fluorescence emission spectra were recorded at five different temperatures (298 to 338 K) in the range from 300 nm to 500 nm at the excitation wavelength of 280 nm on a Synergy HTX multi-mode reader (Biotek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA), equipped with a 1.0 cm quartz cell holder. During the folding or unfolding process of the enzyme, exposure and change of hydrophobic patches in any folded/unfolded protein can be determined. All of the mixtures were held for 10 min to equilibrate before measurements. The fluorescence spectra of the buffer containing triazolopyrimidine 9s without the enzyme were subtracted as the background fluorescence50.

The α-glucosidase enzyme contains three primary intrinsic fluorophores, named tryptophan, tyrosine, and phenylalanine, located within or near the active site. The fluorescence spectroscopy in this study, as depicted in Fig. 4, showed a shift in the emission maximum and a significant increase in the intensity in concentration-dependent manner (0 to 25 µM) around 340 nm, both of which means triazolopyrimidine 9s may be positioned near the binding locations to make the pivotal interactions which cause conformational changes, mainly altering the local chemical environment around tryptophan residue(s)51. Such interactions probably induce conformational changes in the tertiary structure of α-glucosidase, subsequently contributing to the enzymatic activity inhibition52.

(a) Fluorescence spectroscopy of α-glucosidase in the presence of triazolopyrimidine 9s concentrations (0–25 µM) at phosphate buffer (100 mM, pH 6.8); (b) The inset shows the change in absorbance at 25 ℃ as a function of concentration of triazolopyrimidine 9s; (c) Fraction of unfolded α-glucosidase in various concentrations of triazolopyrimidine 9s at pH 6.8.

There are various non-covalent forces between ligands and proteins, including hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces, electrostatic attraction, and hydrophobic interaction. To identify this type in triazolopyrimidne 9s-α-glucosidase complex. To identify this type, thermodynamic parameters should be determined. To this aim, the stability of this complex was evaluated by monitoring the fluorescence intensity 340 nm to 350 nm at five temperatures (298, 308, 318, 328, and 338 k) using the two-state equilibrium model N ↔ U. The denatured fraction (FD) of protein was calculated from Eq. 1, assuming a two-state mechanism for protein denaturation.

In this Eq. 1, Yobs, YN, and YD are observed absorbance, the values of absorbance characteristics of a fully native and denatured conformation, respectively. After finding FD, the apparent equilibrium constant (K) for a reversible denaturation process between native and denatured protein states and the standard Gibbs free energy change (ΔG°) for protein denaturation were calculated using Eqs. 2 and 4, respectively:

T and R are the absolute temperature and the universal gas constant, respectively. The Gibbs free energy (ΔG°) is the most valuable standard of protein conformational stability in thermal denaturation. The integrated Gibbs–Helmholtz equation was utilized for measuring changes in the Gibbs energy of a system as a function of temperature as below:

where ΔCp is the heat capacity of protein denaturation, the ΔCp (11.6 kJ/mol K) of the α-glucosidase denaturation. In thermal denaturation, Tm is the temperature at which the protein is half-denatured. ΔHºm and ΔSºm are the standard enthalpy and entropy of denaturation. The standard entropy was calculated from a relation between the standard enthalpy (ΔS) and entropy (ΔH) of denaturation as below:

The results are summarized in Table 4:

Using the magnitude and sign of the thermodynamic parameters, type of interactions could be determined as follow: (1) hydrophobic interactions with ΔH° > 0, ΔS° > 0; (2) van der Waals forces with ΔH° < 0, ΔS° > 0; (3) hydrogen bond and van der Waals interactions with ΔH° < 0, ΔS° < 0; and (4) electrostatic interactions with ΔH° < 0, ΔS° > 0. Therefore, Table 3 revealed that triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine 9s formed the hydrogen bond and van der Waals interactions with aminoacids, particularly tryptophan, leading the enzyme to the unfolded state53,54.

Computational studies

Model performance and augmentation

In recent years, computational techniques have played key role in accelerating the drug discovery and development process. Among them, machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) models have been widely used for virtual screening and molecular property prediction. Notably, language models such as BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers), which originally developed for natural language processing, have been successfully adapted to interpret chemical SMILES strings as textual sequences55. By pre-training BERT on large molecular databases, rich chemical representations can be learned and subsequently fine-tuned on task-specific datasets with limited size. To address the common issue of data scarcity in drug discovery, SMILES augmentation techniques—generating multiple equivalent SMILES for each compound—have proven highly effective. Recent studies show that combining BERT-based models with SMILES augmentation significantly enhances the prediction of biological activity and ADMET properties, offering a powerful framework for rational drug design56,57.

In this study, a data-augmented BERT-based deep learning framework was employed to predict the potency of chemically accessible α-glucosidase inhibitors, which were subsequently synthesized and experimentally validated for inhibitory activity. Pre-trained chemical language models were fine-tuned with SMILES augmentation to predict α-glucosidase inhibitory activity, then molecular docking and dynamics (MD) studies were performed.

A deep learning pipeline was developed to evaluate ten pre-trained transformer models obtained from the Hugging Face repository, including chemical language models such as ChemBERT and the PC10M-series. Each model was fine-tuned using SMILES representations of over 1500 known α-glucosidase inhibitors. The dataset was partitioned for internal 4-fold cross-validation (75% training, 25% testing, repeated across 10 iterations) as well as external validation (in which entire publications were held out as test sets over 30 iterations) in order to minimize data leakage.

A comparison of model performance metrics before and after the application of SMILES augmentation revealed substantial improvements. The augmentation process increased the effective dataset size and contributed to a reduction in overfitting. For instance, under the PC10M-450k model, both overall accuracy (ACC) and Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) improved notably following augmentation, indicating enhanced generalization capability. These effects are illustrated in Table 5, which compares ACC and MCC values for models trained with and without SMILES augmentation, showing that augmentation significantly improved all metrics.

The PC10M-450k model achieved the highest Matthews Correlation Coefficient (0.75) after augmentation, indicating a well-balanced and robust classification performance for both active and inactive compounds. With an ACC score of 0.90, this fine-tuned model was subsequently employed to predict the inhibitory activity of newly synthesized compounds 9a-9t. As shown in Table 6, the model accurately predicted the activity profiles of these compounds, demonstrating its practical utility in guiding the design and identification of further potential α-glucosidase inhibitors.

Statistical comparison via ANOVA test comparing all models revealed significant differences in accuracy scores (F = 163, p < 0.0001), indicating that the models did not perform equally. Post-hoc Tukey’s HSD analysis showed no significant difference in accuracy between PC10M-450k and PC10M-396_250 (p > 0.05), while both significantly outperformed the other models (p < 0.01). Given its superior recall, PC10M-450k was selected for subsequent screening.

A one-way ANOVA test conducted across all transformer-based models yielded a highly significant result (F = 163, p < 0.0001), clearly indicating that model performance in terms of accuracy was not uniform. This statistically confirms that the choice of pre-trained model architecture significantly influences predictive outcomes.

Molecular Docking studies

Molecular docking studies were conducted using AutoDock4 (version 4.2.6) to analyze the interactions between the compounds. PDB ID 3A4A was selected for structural analysis due to its high sequence similarity (more than 80%) with α-glucosidase58, finding valuable insights into the binding affinities and interaction profiles of the newly synthesized [1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-6-amines 9a-9t. As summarized in Table 6, the docking scores—showing the predicted binding affinity—ranged from − 8.14 to -9.46 kcal/mol, revealing the strong binding potential of all triazolopyrimidines with the active site of enzyme. Notably, compound 9s (IC50 = 24.32 ± 0.18 µM), having the lowest IC50 value in the enzymatic assay, was also among those with the most favorable docking energies (-9.3 kcal/mol).

As depicted in Fig. 5, the docking analysis of triazolopyrimidine 9s within the α-glucosidase active site revealed a network of stabilizing interactions. This inhibitor occupied a predominantly hydrophobic cleft, with Phe303 engaging in π–π stacking with the triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine core. This residue is part of the active site’s hydrophobic side chains, which means this interaction is important for securing the ligand, especially with 9s’s hydrophobicity. Surrounding hydrophobic residues, including Phe314 (located at the bottom of the active site pocket), Tyr72, and Tyr158 (located at the entrance to the pocket)59, contributed the additional van der Waals contacts that consolidate the binding pose. A halogen bond was established between the chlorine atom of the chlorophenyl moiety and Arg315 at the charged surface, serving as a key anchoring interaction. Furthermore, His112 and Gln182 are positioned near the terminal aryl chloride, forming polar contacts and shape-complementary interactions which helped in maintaining the ligand’s orientation.

Overall, ligand 9s was primarily stabilized by hydrophobic interactions, most notably with Phe303. Its orientation within the binding pocket was further guided by halogen bonds involving the chlorine substituent and residues Gln182 and Arg315. Additionally, His112, a valuable residue responsible for hydrogen bonding with the original ligand in 3A4A59, contributed additional interactions that helped secure the ligand in place. Collectively, these interactions ensured a well-fitted and stable accommodation of triazolopyrimidine 9s within the α-glucosidase active site, consistent with its observed inhibitory potency.

Molecular dynamics simulation

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations play a pivotal role in exploring the inhibitory mechanisms of α-glucosidase. This computational approach provides detailed observation of enzyme–inhibitor interactions, offering insights into both structural flexibility and functional behavior at the atomic scale. Through dynamic modeling, researchers can uncover the binding pathways and identify critical amino acid residues that govern the strength and specificity of ligand attachment. Moreover, MD simulations assess the temporal stability of the enzyme–inhibitor complex using metrics such as Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), which helps differentiate between competitive and non-competitive modes of inhibition.

To evaluate the dynamic stability and interaction profile of the α-glucosidase–ligand complexes, 200 ns molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed for both acarbose and triazolopyrimidine 9s. The time evolution of RMSD values revealed distinct stability patterns. In the acarbose-bound complex (Fig. 6A), the protein backbone RMSD stabilized around 1.5–2.0 Å after ~ 50 ns, while the ligand RMSD gradually increased to ~ 8–9 Å, indicating significant ligand displacement. In contrast, the 9s-bound complex (Fig. 6B) exhibited slightly higher protein fluctuations (up to ~ 2.8 Å) but maintained a lower ligand RMSD (~ 4–5 Å), suggesting a more stable binding pose. These results revealed that acarbose, despite inducing minimal protein perturbation, underwent considerable reorientation or partial dissociation from the active site. Conversely, compound 9s remained tightly bound, even as the protein experienced moderate conformational changes, indicating a more stable and persistent interaction.

Although the ligand RMSD of 9s reached ~ 5.6 Å, this mainly reflects internal conformational flexibility and pose rearrangements within the open glycosidase pocket. Consistently, MM/GBSA analysis (Fig. 7) over the trajectory yielded a more favorable binding free energy for 9s (⟨ΔG_bind⟩ = −48.5 ± 8.2 kcal·mol⁻¹; range − 67.3 to − 24) compared with acarbose (⟨ΔG_bind⟩ = −33.8 ± 8.0 kcal·mol⁻¹; range − 65.3 to − 13), supporting a stably bound complex despite larger ligand RMSD.

Ligand-centric metrics further illustrated the differences in size and flexibility between compound 9s and acarbose. As shown in Fig. 8, acarbose exhibited a larger average RMSD (~ 2–3 Å) and radius of gyration (~ 5.4 Å) compared to 9s (~ 1 Å RMSD, ~ 4.3 Å rGyr), consistent with its bulky, polyhydroxylated structure. The number of intramolecular hydrogen bonds also differed: acarbose formed 0 to 2 internal hydrogen bonds intermittently, whereas compound 9s showed none, reflecting its simpler scaffold. Correspondingly, acarbose’s molecular surface area (~ 480 Ų) and polar surface area (~ 500 Ų) were much greater than those of compound 9s (~ 300 Ų MolSA, ~ 100 Ų PSA). Its solvent-accessible surface area (~ 500 Ų) likewise far exceeded that of compound 9s (~ 200 Ų), indicating that acarbose remained highly solvated and extended throughout the simulation.

In MD terms, acarbose behaved like a flexible polar ligand: its RMSD, PSA, and rGyr showed larger fluctuations—especially during the first ~ 50 ns—before reaching equilibrium. This behavior mirrors previous reports where polar ligands exhibit significant early fluctuations in RMSD, PSA, and rGyr prior to stabilization. By contrast, compound 9s’s compact metrics and lack of internal hydrogen bonding resembled those of a small, rigid ligand, which typically exhibited minimal fluctuations in radius of gyration or surface area. Overall, acarbose’s larger size and polarity led to a more extended and internally hydrogen-bonded conformation that adjusted during the simulation, whereas these metrics suggest that compound 9s behaves as a compact, lipophilic ligand with stable conformational properties throughout the simulation.

Contact frequency analysis (Fig. 9) revealed that the compound 9s–α-glucosidase complex is primarily stabilized by hydrophobic interactions. Aromatic residues such as Tyr72, Tyr158, Phe159, Phe178, and Phe303 formed persistent contacts, supported by Val216, Arg315, Val410, and Arg442. Halogen bonding was highly localized, with Met70, Tyr72, and Gln182 maintaining interactions in ~ 60% of frames. Additional halogen contacts were observed with Asp69 and His280. Hydrogen bonding was less frequent, dominated by Asn414, with minor contributions from Tyr72, Gln279, and Arg315. Water-mediated bridges clustered around Tyr72 and Arg315, and to a lesser extent at Asp352, Gln353, and Leu313. Ionic interactions were negligible, consistent with the ligand’s nonpolar character.

Overall, the triazolopyrimidine 9s–α-glucosidase complex was primarily stabilized by hydrophobic interactions, mediated by aromatic and nonpolar residues. These interactions were reinforced by frequent halogen bonds—most notably with Gln182—and a peripheral hydrogen-bonding network centered around Asn414 (Fig. 10). The MD simulation results were consistent with the docking findings: Phe303 maintained persistent hydrophobic contacts, Arg315 interacted through both hydrophobic and water-mediated bridges, and His112 contributed weak or transient contacts. Among all residues, Gln182 emerged as a key polar anchor, forming stable halogen bonds throughout the trajectory.

Conclusion

The primary aim of this study was to identify novel α-glucosidase inhibitors with enhanced potency and selectivity over acarbose, while minimizing the typical gastrointestinal side effects by reducing α-amylase inhibition. To achieve this aim, a new class of [1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidines was successfully synthesized and evaluated for their α-glucosidase and α-amylase inhibitory potencies. This work addresses a significant gap in the literature by providing the first detailed report on the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of this specific triazolopyrimidine scaffold. Unlike previous studies focusing only on synthetic yields or preliminary activity screening, we established the comprehensive investigations to provide a clear rationale for the observed α-glucosidase activity based on key enzyme-inhibitor interactions.

Among them, compound 9s emerged as a highly potent and selective α-glucosidase inhibitor, demonstrating superior activity compared to acarbose. Spectroscopic and computational analyses revealed that its inhibitory mechanism involved conformational stabilization of the enzyme and persistent hydrophobic and halogen-bond interactions. The successful application of deep learning models and the established SAR analysis provided a powerful framework for the virtual screening and rational design of next-generation derivatives with enhanced properties. However, a limitation of this study is the absence of in vivo antidiabetic activity and toxicity data, which will be our focus in subsequent research.

In summary, these results highlight the potential of triazolopyrimidine-based scaffolds as α-glucosidase inhibitors with enhanced efficacy and selectivity. Given its favorable pharmacological profile and structural adaptability, this scaffold offers a promising foundation for further investigation.

Materials and methods

All reagents and solvents were obtained from Merck (Germany) and utilized as received, without additional purification. The synthesis progress and compound purity were routinely assessed via thin-layer chromatography (TLC), employing silica gel F254 plates (250 μm thickness). Visualization of chromatographic spots was achieved under UV illumination at 254 nm.

Melting points were determined using an Electrothermal 9100 apparatus. Infrared (IR) spectra were recorded on a Shimadzu IR-460 spectrometer. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were measured (DMSO-d6 solution) with Bruker DRX-500 AVANCE (at 500.1 and 125.8 MHz) and Bruker DRX-400 AVANCE (at 400.1 and 100.1 MHz) instruments. Chemical shifts are reported in ppm relative to tetramethylsilane (TMS), and signal multiplicities are denoted as singlet (s), doublet (d), triplet (t), or multiplet (m). High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) was performed using a Waters Synapt G1 HDMS system equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source. Samples were diluted in methanol to a final concentration of 10 µg/mL and analyzed in positive ion mode across an m/z range of 50–1000. Elemental composition (C, H, N) was verified via CHN analysis using a Heraeus CHN-O-Rapid analyzer.

General synthetic procedures

General procedure for the Preparation of Chalcones 3

A mixture of ethanol and distilled water was cooled to 0 °C using an ice bath, and sodium hydroxide (1 equiv.) was added under continuous stirring. Subsequently, 1-(aryl)ethan-1-one derivatives 2 (1 equiv.) were introduced to activate the enolate intermediate. After 5 min of stirring, the corresponding aldehyde 1 (1 equiv.) was added dropwise, resulting in a rapid temperature increase to approximately 30 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred for 3 h at ambient conditions until completion. Afterward, the reaction was stored at 4 °C for 10 h to facilitate precipitation. The solid product was collected by filtration and washed thoroughly with a cold ethanol and water mixture to afford the desired chalcone derivatives 3 as pure solid60.

General procedure for the Preparation of dibromochalcones 5

Chalcone derivative 3 (1 equiv.) was dissolved in diethyl ether and stirred under ice bath conditions (0 °C). Bromine (Br2) 4 (1.2 equiv.) was added dropwise. The mixture was kept at 0 °C for 4 h, during which the gradual fading of color indicated progression toward completion. Upon completion as confirmed by TLC analysis, the reaction mixture was carefully poured into chilled distilled water to induce precipitation. The resulting solid was isolated by filtration and washed thoroughly with cold water to remove residual bromine. The obtained compound 5 was sufficiently pure and used directly in subsequent synthetic steps without further purification61.

General procedure for the Preparation of α-azidochalcones 7

Dibromochalcone 5 (1 equiv.) was reacted with sodium azide (NaN3) 6 (4 equiv.) in DMF at room temperature. The reaction was stirred until complete consumption of the starting materials, as confirmed by TLC monitoring. Upon completion, the mixture was quenched with cold water and extracted three times using ethyl acetate (EtOAc). The combined organic layers were washed with saturated brine solution, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate (Na2SO4), and concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting crude product was purified by recrystallization from n-hexane to afford the target α-azidochalcone derivatives 7 in pure form61.

General procedure for the Preparation of 5,7-diaryl-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-6-amines 9

A mixture of α-azidochalcones 7 (1 equiv.) and 1H-1,2,4-triazol-3-amine 8 (1 equiv.) was refluxed in absolute acetonitrile in the presence of potassium carbonate (1.5 equiv.) under the argon atmosphere. After approximately 4 h, completion of the reaction was confirmed by TLC analysis. The reaction mixture was then cooled to the ambient temperature, and crushed ice was added to facilitate the precipitation of the desired [1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidines 9. The solid product was collected by filtration, washed with water, and subsequently recrystallized from ethanol to afford the pure compounds 9 as pale-yellow powders.

5,7-Diphenyl-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-6-amine (9a)

Pale-yellow solid, mp 164–166 °C, yield: 0.209 g, 73%. IR (KBr) (νmax/cm–1): 3362 and 3283 (NH2), 1617, 1525, 1439, 1390, 1321, 1251, 1203, 1171, 1106, 1039, 1017, 962, 929, 826, 759, 709, 681, 657. 1H NMR (400.1 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.31 (s, 1H, CH), 7.89 (dd, J = 7.5, 1.7 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.76 (dd, J = 7.4, 1.2 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.67 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.64–7.53 (m, 4 H, 4CH), 3.86 (s, 2 H, NH2). 13C NMR (100.1 MHz, CDCl3) δ 155.52, 154.86, 150.96, 136.16, 130.92, 130.35, 129.67, 129.54, 129.06, 128.72, 128.33, 127.82, 124.88. HRMS (ESI) m/z for C17H14N5+ [M + H]+, calculated: 288.1244, found: 288.1257. Anal. Calcd. for C17H13N5: C, 71.06; H, 4.56; N, 24.37; found: C, 70.94; H, 4.66; N, 24.54%.

7-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-5-phenyl-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-6-amine (9b)

Yellow solid, mp 192–195 °C, yield: 0.266 g, 84%. IR (KBr) (νmax/cm–1): 3328 and 3098 (NH2), 1613, 1519, 1452, 1427, 1384, 1309, 1244, 1199, 1157, 1103, 1032, 1009, 958, 857, 772, 703, 668. 1H NMR (500.1 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.27 (s, 1H, CH), 7.88 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.73 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.64 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.58 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H, CH), 7.03 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 3.87 (s, 3 H, OCH3), 3.77 (br. s, 2 H, NH2). 13C NMR (100.1 MHz, CDCl3) δ 161.20, 155.25, 154.57, 150.95, 130.73, 130.38, 129.53, 129.52, 128.50, 128.22, 127.92, 124.82, 114.28, 55.38. HRMS (ESI) m/z for C18H16N5O+ [M + H]+, calculated: 318.1349, found: 318.1346. Anal. Calcd. for C18H15N5O: C, 68.13; H, 4.76; N, 22.07; found: C, 68.22; H, 4.90; N, 22.25%.

7-(4-Chlorophenyl)-5-phenyl-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-6-amine (9c)

Pale-yellow solid, mp 208–211 °C, yield: 0.254 g, 79%. IR (KBr) (νmax/cm–1): 3359 and 3276 (NH2), 1610, 1520, 1432, 1385, 1311, 1250, 1200, 1162, 1098, 1032, 1098, 1032, 1009, 955, 919, 823, 771, 754, 703, 674, 648. 1H NMR (500.1 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.29 (s, 1H, CH), 7.86 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.74 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.66 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.61 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H, CH), 7.52 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 3.85 (s, 2 H, NH2). 13C NMR (125.8 MHz, CDCl3): δ 154.99, 154.15, 150.91, 136.55, 134.56, 131.03, 130.25, 129.69, 129.51, 129.27, 128.23, 127.62, 124.56. HRMS (ESI) m/z for C17H13ClN5+ [M + H]+, calculated: 322.0854, found: 322.0856. Anal. Calcd. for C17H12ClN5: C, 63.46; H, 3.76; N, 21.77; found: C, 63.52; H, 3.64; N, 21.88%.

7-(3-Chlorophenyl)-5-phenyl-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-6-amine (9d)

Pale-yellow solid, mp 179–181 °C, yield: 0.219 g, 68%. IR (KBr) (νmax/cm–1): 3349 and 3265 (NH2), 1615, 1519, 1451, 1426, 185, 1318, 1267, 1190, 1163, 1106, 1051, 1031, 1008, 952, 924, 850, 769, 706, 660. 1H NMR (500.1 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.27 (s, 1H, CH), 7.84 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.74 (s, 1H, CH), 7.64 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, CH), 7.60–7.45 (m, 5 H, 5CH), 3.93 (s, 2 H, NH2). 13C NMR (125.8 MHz, CDCl3): δ 155.72, 154.79, 150.81, 135.92, 135.58, 131.01, 130.96, 130.44, 129.71, 129.49, 129.08, 128.65, 128.54, 127.87, 124.75. HRMS (ESI) m/z for C17H13ClN5+ [M + H]+, calculated: 322.0854, found: 322.0868. Anal. Calcd. for C17H12ClN5: C, 63.46; H, 3.76; N, 21.77; found: C, 63.34; H, 3.69; N, 21.58%.

7-(2-Chlorophenyl)-5-phenyl-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-6-amine (9e)

Pale-yellow solid, mp 154–157 °C, yield: 0.174 g, 54%. IR (KBr) (νmax/cm–1): 3326 and 3282 (NH2), 1608, 1521, 1466, 1434, 1389, 1315, 1252, 1200, 1164, 1108, 1038, 1012, 957, 920, 863, 826, 774, 758, 706, 681. 1H NMR (500.1 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.30 (s, 1H, CH), 7.89 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.68 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, CH), 7.65–7.45 (m, 6 H, 6CH), 3.78 (s, 2 H, NH2). 13C NMR (125.8 MHz, CDCl3): δ 155.37, 154.95, 150.69, 135.96, 134.24, 132.40, 131.50, 130.90, 130.44, 129.15, 129.09, 128.71, 128.19, 127.01, 124.91. HRMS (ESI) m/z for C17H13ClN5+ [M + H]+, calculated: 322.0854, found: 322.0846. Anal. Calcd. for C17H12ClN5: C, 63.46; H, 3.76; N, 21.77; found: C, 63.54; H, 3.88; N, 21.94%.

7-(4-Bromophenyl)-5-phenyl-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-6-amine (9f)

Pale-yellow solid, mp 219–222 °C, yield: 0.326 g, 89%. IR (KBr) (νmax/cm–1): 3358 and 3274 (NH2), 1614, 1519, 1432, 1385, 1312, 1251, 1200, 1163, 1125, 1100, 1035, 1011, 843, 773, 703, 659. 1H NMR (500.1 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.29 (s, 1H, CH), 7.80 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.74 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.68 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.66 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.60 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H, CH), 3.84 (s, 2 H, NH2). 13C NMR (125.8 MHz, CDCl3): δ 155.02, 154.17, 150.95, 135.03, 132.23, 131.03, 130.46, 130.27, 129.69, 129.51, 128.17, 127.62, 124.91. HRMS (ESI) m/z for C17H13BrN5+ [M + H]+, calculated: 366.0349, found: 366.0353. Anal. Calcd. for C17H12BrN5: C, 55.75; H, 3.30; N, 19.12; found: C, 55.89; H, 3.39; N, 19.24%.

5-Phenyl-7-(thiophen-2-yl)-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-6-amine (9 g)

Pale-yellow solid, mp 162–165 °C, yield: 0.185 g, 63%. IR (KBr) (νmax/cm–1): 3298 and 3124 (NH2), 1611, 1518, 1463, 1431, 1386, 1312, 1249, 1197, 1161, 1105, 1035, 1009, 954, 917, 860, 823, 771, 755, 703, 678. 1H NMR (500.1 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.27 (s, 1H, CH), 8.00 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 1H, CH), 7.75 (d, J = 3.0 Hz, 1H, CH), 7.71 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.66 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.60 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, CH), 7.19 (t, J = 4.0 Hz, 1H, CH), 4.05 (s, 2 H, NH2). 13C NMR (125.8 MHz, CDCl3): δ 155.13, 150.70, 149.01, 140.54, 131.02, 130.88, 129.69, 129.60, 129.42, 128.12, 127.63, 127.50, 124.85. HRMS (ESI) m/z for C15H12N5S+ [M + H]+, calculated: 294.0808, found: 294.0814. Anal. Calcd. for C15H11N5S: C, 61.42; H, 3.78; N, 23.87; found: C, 61.49; H, 3.89; N, 23.94%.

7-Phenyl-5-(p-tolyl)-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-6-amine (9 h)

Pale-yellow solid, mp 197–199 °C, yield: 0.235 g, 78%. IR (KBr) (νmax/cm–1): 3387 and 3246 (NH2), 1620, 1525, 1460, 1434, 1402, 1315, 1252, 1166, 1100, 1050, 1014, 966, 922, 870, 811, 776, 729, 709, 675. 1H NMR (500.1 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.29 (s, 1H, CH), 7.90 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.64 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.52–7.41 (m, 5 H, 5CH), 3.99 (s, 2 H, NH2), 2.46 (s, 3 H, CH3). 13C NMR (125.8 MHz, CDCl3) δ 155.07, 154.15, 150.80, 136.40, 134.41, 131.02, 130.43, 129.60, 128.98, 128.33, 127.86, 127.61, 124.68, 21.12. HRMS (ESI) m/z for C18H16N5+ [M + H]+, calculated: 302.1400, found: 302.1397. Anal. Calcd. for C18H15N5: C, 71.74; H, 5.02; N, 23.24; found: C, 71.82; H, 5.14; N, 23.29%.

7-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-5-(p-tolyl)-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-6-amine (9i)

Pale-yellow solid, mp 233–236 °C, yield: 0.285 g, 86%. IR (KBr) (νmax/cm–1): 3297 and 3188 (NH2), 1613, 1518, 1451, 1424, 1384, 1308, 1259, 1188, 1158, 1092, 1043, 1005, 958, 922, 850, 770, 743, 701, 656. 1H NMR (500.1 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.31 (s, 1H, CH), 7.83 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.62 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.44 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.02 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 3.96 (s, 2 H, NH2), 3.88 (s, 3 H, OCH3), 2.48 (s, 3 H, CH3). 13C NMR (125.8 MHz, CDCl3) δ 161.03, 155.54, 153.94, 151.51, 136.08, 134.10, 130.68, 130.11, 128.32, 127.40, 127.36, 124.45, 115.12, 55.40, 21.25. HRMS (ESI) m/z for C19H18N5O+ [M + H]+, calculated: 332.1506, found: 332.1514. Anal. Calcd. for C19H17N5O: C, 68.87; H, 5.17; N, 21.13; found: C, 68.96; H, 5.02; N, 21.22%.

7-(4-Chlorophenyl)-5-(p-tolyl)-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-6-amine (9j)

Pale-yellow solid, mp 218–220 °C, yield: 0.235 g, 70%. IR (KBr) (νmax/cm–1): 3367 and 3281 (NH2), 1616, 1522, 1458, 1436, 1387, 1316, 1253, 1199, 1165, 1106, 1062, 1013, 957, 923, 850, 821, 777, 761, 806, 676, 651. 1H NMR (500.1 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.27 (s, 1H, CH), 7.86 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.62 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.50 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.45 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 3.85 (s, 2 H, NH2), 2.48 (s, 3 H, CH3). 13C NMR (125.8 MHz, CDCl3): δ 154.96, 153.97, 150.95, 141.43, 136.46, 134.66, 130.58, 130.34, 130.26, 129.35, 129.22, 128.18, 124.58, 21.67. HRMS (ESI) m/z for C18H15ClN5+ [M + H]+, calculated: 336.1010, found: 336.1017. Anal. Calcd. for C18H14ClN5: C, 64.38; H, 4.20; N, 20.86; found: C, 64.47; H, 4.08; N, 21.81%.

7-(4-Bromophenyl)-5-(p-tolyl)-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-6-amine (9k)

Pale-yellow solid, mp 230–233 °C, yield: 0.300 g, 79%. IR (KBr) (νmax/cm–1): 3353 and 3278 (NH2), 1618, 1570, 1466, 1429, 1377, 1344, 1268, 1220, 1123, 1046, 1020, 985, 887, 806, 734, 669. 1H NMR (400.1 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.31 (s, 1H, CH), 7.82 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.7. (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.64 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.47 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 3.82 (s, 2 H, NH2), 2.49 (s, 3 H, CH3). 13C NMR (125.8 MHz, CDCl3): δ 155.08, 154.00, 151.05, 141.46, 135.14, 132.23, 130.64, 130.49, 130.38, 129.35, 128.05, 124.86, 124.59, 21.67. HRMS (ESI) m/z for C18H15BrN5+ [M + H]+, calculated: 380.0505, found: 380.0508. Anal. Calcd. for C18H14BrN5: C, 56.86; H, 3.71; N, 18.42; found: C, 56.72; H, 3.79; N, 18.36%.

7-(Thiophen-2-yl)-5-(p-tolyl)-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-6-amine (9 L)

Pale-yellow solid, mp 179–182 °C, yield: 0.150 g, 49%. IR (KBr) (νmax/cm–1): 3347 and 3189 (NH2), 1622, 1518, 1481, 1429, 1396, 1320, 1272, 1175, 1098, 1072, 1037, 939, 858, 786, 721, 689, 641. 1H NMR (500.1 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.28 (s, 1H, CH), 8.00 (d, J = 4.5 Hz, 1H, CH), 7.66–7.56 (m, 3 H, 3CH), 7.47 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.21 (t, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H, CH), 4.02 (s, 2 H, NH2), 2.49 (s, 3 H, CH3). 13C NMR (125.8 MHz, CDCl3): δ 155.13, 150.70, 149.01, 140.54, 131.02, 130.88, 129.69, 129.60, 129.42, 128.12, 127.63, 127.50, 124.85, 21.66. HRMS (ESI) m/z for C16H14N5S+ [M + H]+, calculated: 308.0964, found: 308.0963. Anal. Calcd. for C16H13N5S: C, 62.52; H, 4.26; N, 22.78; found: C, 62.64; H, 4.41; N, 22.85%.

5-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-7-phenyl-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-6-amine (9 m)

Pale-yellow solid, mp 206–209 °C, yield: 0.257 g, 81%. IR (KBr) (νmax/cm–1): 3299 and 3128 (NH2), 1618, 1569, 1475, 1411, 1389, 1340, 1269, 1206, 1152, 1118, 1059, 1015, 966, 910, 876, 803, 774, 730, 714, 759, 629. 1H NMR (500.1 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.28 (s, 1H, CH), 8.00 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.74 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.46–7.36 (m, 3 H, 3CH), 7.18 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 4.04 (s, 2 H, NH2), 3.89 (s, 3 H, OCH3). 13C NMR (125.8 MHz, CDCl3): δ 161.13, 155.39, 154.19, 151.43, 135.99, 130.30, 129.92, 129.31, 128.75, 128.55, 124.13, 120.23, 114.34, 55.29. HRMS (ESI) m/z for C18H16N5O+ [M + H]+, calculated: 318.1349, found: 318.1357. Anal. Calcd. for C18H15N5O: C, 68.13; H, 4.76; N, 22.07; found: C, 68.19; H, 4.88; N, 22.21%.

5,7-Bis(4-methoxyphenyl)-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-6-amine (9n)

Pale-yellow solid, mp 249–252 °C, yield: 0.250 g, 72%. IR (KBr) (νmax/cm–1): 3358 and 3152 (NH2), 1615, 1511, 1474, 1422, 1389, 1313, 1265, 1168, 1091, 1065, 1030, 932, 851, 779, 714, 683, 642. 1H NMR (500.1 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.48 (s, 1H, CH), 8.20 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 8.13 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.09 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.01 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 4.10 (s, 2 H, NH2), 3.91 and 3.88 (2s, 6 H, 2OCH3). 13C NMR (125.8 MHz, CDCl3) δ 162.30, 162.28, 161.02, 156.32, 155.53, 147.44, 131.01, 129.37, 128.82, 122.25, 114.31, 114.29, 105.04, 55.50, 55.41. HRMS (ESI) m/z for C19H18N5O2+ [M + H]+, calculated: 348.1455, found: 348.1457. Anal. Calcd. for C19H17N5O2: C, 65.69; H, 4.93; N, 20.16; found: C, 65.61; H, 5.05; N, 20.29%.

7-(4-Chlorophenyl)-5-(4-methoxyphenyl)-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-6-amine (9o)

Pale-yellow solid, mp 232–234 °C, yield: 0.296 g, 84%. IR (KBr) (νmax/cm–1): 3384 and 3291 (NH2), 1620, 1517, 1479, 1425, 1396, 1320, 1270, 1205, 1170, 1098, 1068, 1035, 938, 844, 786, 759, 720, 696, 643. 1H NMR (500.1 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.30 (s, 1H, CH), 7.87 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.71 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.52 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.16 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 3.91 (s, 2 H, NH2), 3.84 (s, 3 H, OCH3). 13C NMR (125.8 MHz, CDCl3): δ 161.36, 154.97, 153.91, 151.02, 136.47, 134.68, 131.15, 130.28, 129.24, 128.12, 124.63, 119.41, 115.04, 55.52. HRMS (ESI) m/z for C18H15ClN5O+ [M + H]+, calculated: 352.0960, found: 352.0954. Anal. Calcd. for C18H14ClN5O: C, 61.46; H, 4.01; N, 19.91; found: C, 61.54; H, 3.89; N, 20.06%.

5-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-7-(thiophen-2-yl)-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-6-amine (9p)

Pale-yellow solid, mp 193–195 °C, yield: 0.184 g, 57%. IR (KBr) (νmax/cm–1): 3323 and 3258 (NH2), 1608, 1536, 1457, 1382, 1313, 1253, 1142, 1083, 945, 863, 744, 679, 623. 1H NMR (500.1 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.32 (s, 1H, CH), 8.11 (dd, J = 4.9, 0.9 Hz, 1H, CH), 7.90 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.85 (dd, J = 3.8, 1.0 Hz, 1H, CH), 7.18 (t, J = 3.2 Hz, 1H, CH), 7.09 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 3.94 (s, 2 H, NH2), 3.80 (s, 3 H, OCH3). 13C NMR (125.8 MHz, CDCl3): δ 161.00, 155.42, 150.92, 148.97, 140.59, 131.06, 129.73, 129.42, 128.14, 127.42, 124.57, 119.49, 115.38, 55.53. HRMS (ESI) m/z for C16H14N5OS+ [M + H]+, calculated: 324.0914, found: 324.0922. Anal. Calcd. for C16H13N5OS: C, 59.43; H, 4.05; N, 21.66; found: C, 59.51; H, 4.17; N, 21.83%.

5-(4-Chlorophenyl)-7-phenyl-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-6-amine (9q)

Pale-yellow solid, mp 199–202 °C, yield: 0.245 g, 76%. IR (KBr) (νmax/cm–1): 3367 and 3281 (NH2), 1616, 1522, 1458, 1436, 1387, 1316, 1253, 1199, 1165, 1106, 1062, 1013, 957, 923, 850, 821, 777, 761, 806, 676, 651. 1H NMR (500.1 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.27 (s, 1H, CH), 7.88–7.82 (m, 2 H, 2CH), 7.73 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.62 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.58–7.50 (m, 3 H, 3CH), 3.90 (s, 2 H, NH2). 13C NMR (125.8 MHz, CDCl3): δ 155.64, 154.79, 150.89, 136.98, 135.99, 131.13, 130.42, 129.96, 129.08, 128.67, 128.40, 126.17, 124.79. HRMS (ESI) m/z for C17H13ClN5+ [M + H]+, calculated: 322.0854, found: 322.0851. Anal. Calcd. for C17H12ClN5: C, 64.38; H, 4.20; N, 20.86; found: C, 64.42; H, 4.29; N, 21.01%.

5-(4-Chlorophenyl)-7-(4-methoxyphenyl)-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-6-amine (9r)

Pale-yellow solid, mp 223–226 °C, yield: 0.324 g, 92%. IR (KBr) (νmax/cm–1): 3339 and 3217 (NH2), 1613, 1519, 1455, 1433, 1384, 1313, 1250, 1196, 1162, 1103, 1059, 1010, 954, 920, 847, 818, 774, 758, 803, 673, 648. 1H NMR (500.1 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.31 (s, 1H, CH), 7.90 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.76 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.63 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.11 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 4.01 (s, 2 H, NH2), 3.88 (s, 3 H, OCH3). 13C NMR (125.8 MHz, CDCl3): δ 161.07, 155.13, 153.57, 151.44, 136.32, 134.64, 131.08, 130.06, 128.54, 127.37, 127.17, 124.47, 114.76, 55.49. HRMS (ESI) m/z for C18H15ClN5O+ [M + H]+, calculated: 352.0960, found: 352.0962. Anal. Calcd. for C18H14ClN5O: C, 61.46; H, 4.01; N, 19.91; found: C, 61.52; H, 4.12; N, 20.15%.

5,7-Bis(4-chlorophenyl)-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-6-amine (9s)

Pale-yellow solid, mp 251–253 °C, yield: 0.303 g, 85%. IR (KBr) (νmax/cm–1): 3368 and 3235 (NH2), 1596, 1502, 1473, 1435, 1381, 1352, 1276, 1226, 1161, 1126, 1054, 1024, 991, 894, 800, 742, 715, 676. 1H NMR (500.1 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.33 (s, 1H, CH), 7.87 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.74 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.66 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.56 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 3.79 (br. s, 2 H, NH2). 13C NMR (125.8 MHz, CDCl3): δ 155.80, 154.63, 150.82, 136.89, 135.73, 134.13, 131.36, 130.91, 129.01, 128.93, 128.30, 127.40, 124.75. HRMS (ESI) m/z for C17H12Cl2N5+ [M + H]+, calculated: 356.0464, found: 356.0459. Anal. Calcd. for C17H11Cl2N5: C, 57.32; H, 3.11; N, 19.66; found: C, 57.44; H, 3.20; N, 19.82%.

5-(4-Chlorophenyl)-7-(thiophen-2-yl)-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-6-amine (9t)

Pale-yellow solid, mp 177–179 °C yield: 0.216 g, 66%. IR (KBr) (νmax/cm–1): 3329 and 3198 (NH2), 1608, 1528, 1476, 1439, 1387, 1354, 1278, 1230, 1133, 1056, 1030, 995, 897, 816, 744, 679. 1H NMR (500.1 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.24 (s, 1H, CH), 7.97 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 1H, CH), 7.70 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2 H, 2CH), 7.65–7.55 (m, 3 H, 3CH), 7.19 (t, J = 3.9 Hz, 1H, CH), 4.09 (s, 2 H, NH2). 13C NMR (125.8 MHz, CDCl3): δ 155.05, 150.63, 149.09, 140.33, 137.20, 131.20, 131.04, 130.03, 129.46, 128.17, 127.59, 125.95, 124.46. HRMS (ESI) m/z for C15H11ClN5S+ [M + H]+, calculated: 328.0418, found: 328.0412. Anal. Calcd. for C15H10ClN5S: C, 54.96; H, 3.07; N, 21.37; found: C, 55.08; H, 3.12; N, 21.55%.

α-Glucosidase Inhibition assay

The α-glucosidase enzyme (EC 3.2.1.20, derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, 20 U/mg) and its substrate, p-nitrophenyl-α-D-glucopyranoside, were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. The enzyme was dissolved in potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 6.8), while the synthesized 5,7-diaryl-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-6-amines (compounds 9a-9t) were prepared in DMSO to achieve a final concentration of 10%. For the inhibition assay, 20 µL of each test compound, 20 µL of enzyme solution, and 135 µL of phosphate buffer were dispensed into individual wells of a 96-well microplate and incubated at 37 °C for 10 min. Subsequently, 25 µL of the substrate solution (4 mM) was added, and the mixture was further incubated at 37 °C for 20 min. The enzymatic activity was quantified by measuring absorbance at 405 nm using a microplate reader (Gen5, PowerWave XS2, BioTek, USA). The percentage inhibition was calculated using Eq. 7, and IC50 values were determined through non-linear regression analysis based on the Logit mode20.

α-Glucosidase kinetic studies

To elucidate the inhibition mechanism of α-glucosidase, kinetic studies were conducted using the most active compound, triazolopyrimidine 9s. The enzyme solution (1 U/mL, 20 µL) was pre-incubated with varying concentrations of compound 9s (0, 1.6, 3.3, and 6.6 µM) at 30 °C for 15 min. Following this, a range of substrate concentrations (p-nitrophenyl-α-D-glucopyranoside, 1 to 10 mM) was introduced to initiate the reaction. The enzymatic activity was monitored by measuring the absorbance at 405 nm over a 20-minute period using a microplate spectrophotometer (Gen5 software, PowerWave XS2, BioTek Instruments, USA). The resulting data were used to construct Lineweaver–Burk plots, enabling determination of the inhibition type exerted by compound 9s20.

In the presence of a competitive inhibitor, Km increases while Vmax does not change. Michaelis–Menten saturation curve for an enzyme reaction shows the relation between the substrate concentration and reaction rate as bellow:

According to Michaelis–Menten graph, Kmapp is also defined as:

[I] is the concentration of inhibitor.

Lineweaver Burk plot that provides a useful graphical method for analysis of the Michaelis–Menten is represented as:

Therefore, the slope of Lineweaver Burk plot is equal to:

The Kmapp value is calculated by Eq. 7:

Therefore, from replot of Kmapp Vs. [I], Eq. 13 can be used for the calculation of KI62,63:

α-Amylase Inhibition assay

To investigate the α-amylase inhibitory potency, 40 µL of triazolopyrimidine 9s (prepared in DMSO, final concentration 100 µM) was mixed with 40 µL of α-amylase solution (0.5 mg/mL in 0.006 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 6.9, containing 0.02 M NaCl) in microcentrifuge tubes. The mixtures were incubated at 25 °C for 10 min to allow enzyme–inhibitor interaction. Subsequently, 40 µL of soluble starch solution (1% w/v in 0.02 M sodium phosphate buffer) was added at 5-second intervals, followed by a second incubation at 25 °C for 10 min. The enzymatic reactions were terminated by the addition of 100 µL of dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) reagent, and the tubes were heated in a boiling water bath for 5 min. After cooling to ambient temperature, each sample was diluted with 900 µL of distilled water. Acarbose was used as a reference inhibitor under identical conditions. The percentage inhibition was calculated relative to the control, and comparative potency was assessed20.

Fluorescence spectroscopy measurements

To further investigate the interaction between compound 9s and α-glucosidase, fluorescence spectroscopy was employed. A series of solutions containing α-glucosidase (3 mL, 0.1 U/mL) and increasing concentrations of compound 9s (0 to 1.0 µM) were prepared and incubated at room temperature for 10 min to allow equilibrium binding. Fluorescence measurements were performed using a Synergy HTX multi-mode reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA) equipped with a 1.0 cm quartz cuvette holder. The excitation wavelength was set at 280 nm, and emission spectra were recorded in the range of 300 to 450 nm. To correct for intrinsic fluorescence, spectra obtained from buffer solutions containing compound 9s in the absence of enzyme were subtracted as background35.

Computational studies

Dataset collection

A curated dataset of known α-glucosidase inhibitors from literature (> 90 studies), yielding over 1500 compounds with IC₅₀ values was assembled. Acarbose (IC50 = 750 µM) was included as a positive control. For supervised learning, we binarized activity by setting an IC₅₀ threshold of 142 µM (active if ≤ 142 µM, inactive otherwise), resulting in ~ 1047 actives and 1343 inactives.

Model architecture

The transformer-based sequence classifiers were used (AutoModelForSequenceClassification from Hugging Face) with SMILES strings as the input. Ten publicly available pre-trained chemical language models (from the Seyone Chithrananda and DeepChem collections on Hugging Face) were evaluated as the starting points. Pre-training on large molecular datasets allows these models to encode chemical syntax and semantics, reducing fine-tuning time and improving accuracy. Each model was fine-tuned on our α-glucosidase dataset, using a 4-fold internal cross-validation (75% train, 25% validation, repeated 10 times) and an external validation scheme: hold-out sets drawn from entire published articles (30 repeats) to prevent data leakage.

Fine-tuning

To address limited labeled data and overfitting, SMILES augmentation was applied. For each molecule, multiple randomized SMILES were generated by randomly selecting a starting atom and traversing the molecular graph in a new order. This iterative process produced diverse equivalent SMILES for the same compound. The augmented SMILES were added to the training data to increase chemical variety and improve model generalization.

Augmented SMILES (with original labels) were tokenized and input to the transformer models. The Hugging Face AutoModelForSequenceClassification framework was used, fine-tuning the pre-trained models on our classification task. Training hyperparameters (learning rate, epochs, batch size) were optimized via grid search on the validation splits. Model performance was measured by Accuracy (ACC) and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) on both validation and held-out test sets.

Molecular Docking

Molecular docking simulations were conducted using AutoDock4 (version 4.2.6). The target enzyme structure was obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 3A4A, yeast α-glucosidase). The protein was prepared by removing crystallographic water molecules and adding polar hydrogens. A cubic grid box of 60 Å × 60 Å × 60 Å was defined around the enzyme’s active site, with its center positioned at coordinates x = 21.5, y = − 8.0, and z = 23.5 to encompass the binding pocket fully. Each of the synthesized ligands (compounds 9a-9t) was docked into this site using the Lamarckian genetic algorithm implemented in AutoDock4 under standard parameters.

To validate the docking protocol, the co-crystallized ligand from the 3A4A structure was re-docked into the prepared enzyme. The top-scoring docked pose of the native ligand had a root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of 0.56 Å relative to the experimentally determined conformation, confirming the accuracy and reliability of the docking setup. The highest-ranked docking poses for each ligand were selected to further analyze ligand–receptor interactions via two-dimensional interaction diagrams.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation

To assess binding stability, 200-ns MD simulations were performed in Desmond (Schrödinger 2021-1, GPU-accelerated) on the protein–ligand complexes (α-glucosidase bound to acarbose, actaeaepoxide, or isoferulic acid). Complexes were solvated with SPC water in an orthorhombic box (10 Å buffer), neutralized with ions (0.15 M NaCl). The system was energy-minimized (2500 steps, steepest descent), equilibrated from 0 to 300 K, then run in NPT ensemble (300 K, 1 atm) with Nose–Hoover thermostat and Martyna–Tobias–Klein barostat. Long-range electrostatics used PME (9 Å cutoff). Trajectories were saved every 200 ps for analysis (RMSD, RMSF, and radius of gyration).

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the finding of this study are available within the manuscript and supplementary file.

References

Gao, K. et al. 1-Deoxynojirimycin: occurrence, extraction, chemistry, oral pharmacokinetics, biological activities and in Silico target fishing. Molecules 21, 1600. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules21111600 (2016).

Cade, W. T. Diabetes-related microvascular and macrovascular diseases in the physical therapy setting. Phys. Ther. 88, 1322–1335. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20080008 (2008).

Tokalı, F. S. et al. Aldose reductase inhibition properties of novel thiazolidin-2, 4-diones: in vitro and in Silico approach for the treatment of diabetes-related complications. J. Mol. Liq. 426, 127487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2025.127487 (2025).

Tokalı, P., Demir, Y., Çakır, F., Şenol, H. & Tokalı, F. S. Design, synthesis, and aldose reductase Inhibition assessment of novel Quinazolin-4 (3H)-one derivatives with 4-Bromo-2-Fluorobenzene functionality. Bioorg. Chem. 108614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioorg.2025.108614 (2025).

Cho, N. H. et al. IDF diabetes atlas: global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 138, 271–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2018.02.023 (2018).

Zheng, Y., Ley, S. H. & Hu, F. B. Global aetiology and epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications. Nat. Reviews Endocrinol. 14, 88–98. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2017.151 (2018).

Tokalı, F. S., Demir, Y., Ateşoğlu, Ş., Tokalı, P. & Şenol, H. Development of phenolic Mannich bases as α-glucosidase and aldose reductase inhibitors: in vitro and in Silico approaches for managing diabetes mellitus and its complications. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 118264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmc.2025.118264 (2025).

Tokalı, F. S., Demir, Y., Ateşoğlu, Ş., Tokalı, P. & Şenol, H. Quinazolin-4 (3H)‐One‐Based new glitazones as dual inhibitors of α‐Glucosidase and aldose reductase: comprehensive approaches for managing diabetes mellitus and its complications. Arch. Pharm. 358, e70033. https://doi.org/10.1002/ardp.70033 (2025).

Tokalı, F. S., Demir, Y., Tokalı, P., Ateşoğlu, Ş. & Şenol, H. New Quinazolin-4 (3H)‐One–Thiazolidine‐2, 4‐Dione hybrids as dual inhibitors of α‐Glycosidase and aldose reductase: the Synthetic, in Vitro, and in Silico approaches. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 39, e70412. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbt.70412 (2025).

Krentz, A. J. & Bailey, C. J. Oral antidiabetic agents: current role in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Drugs 65, 385–411. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200565030-00005 (2005).

Peytam, F. et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of new Dihydroindolizino [8, 7-b] Indole derivatives as novel α-glucosidase inhibitors. J. Mol. Struct. 1224, 129290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.129290 (2021).

Singh, A. et al. Recent developments in synthetic α-glucosidase inhibitors: A comprehensive review with structural and molecular insight. J. Mol. Struct. 1281, 135115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2023.135115 (2023).

Mushtaq, A., Azam, U., Mehreen, S. & Naseer, M. M. Synthetic α-glucosidase inhibitors as promising anti-diabetic agents: recent developments and future challenges. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 249, 115119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2023.115119 (2023).

Pan, G. et al. A review on the in vitro and in vivo screening of α-glucosidase inhibitors. Heliyon https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e37467 (2024).

Khan, H. et al. Design, synthesis, molecular Docking study, and α-glucosidase inhibitory evaluation of novel hydrazide–hydrazone derivatives of 3, 4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid. Sci. Rep. 14, 11410. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62034-x (2024).

Sharma, A. et al. An insight on medicinal attributes of 1, 2, 3-and 1, 2, 4‐triazole derivatives as alpha-amylase and alpha-glucosidase inhibitors. Mol. Diversity. 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11030-023-10728-1 (2023).

Abdullah Asif, H. M., Kamal, S., Rehman, A., Rasool, S. & Hamid Akash, M. S. Synthesis, characterization, and enzyme Inhibition properties of 1, 2, 4-triazole bearing Azinane analogues. ACS Omega. 7, 32360–32368. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.2c03779 (2022).

Gani, R. S. et al. Synthesis of novel indole, 1, 2, 4-triazole derivatives as potential glucosidase inhibitors. J. King Saud University-Science. 32, 3388–3399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2020.09.026 (2020).

Mohamed, M. A., Abd Allah, O. A., Bekhit, A. A., Kadry, A. M. & El-Saghier, A. M. Synthesis and antidiabetic activity of novel Triazole derivatives containing amino acids. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 57, 2365–2378. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhet.3951 (2020).

Peytam, F. et al. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of Triazolo [1, 5-a] pyridines as novel and potent α–glucosidase inhibitors. Sci. Rep. 15, 17813. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01819-0 (2025).

Abusaif, M. S. et al. Exploring novel of 1, 2, 4-triazolo [4, 3-a] Quinoxaline sulfonamide regioisomers as anti-diabetic and anti-Alzheimer agents with in-silico molecular Docking simulation. Sci. Rep. 15, 19409. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03139-9 (2025).

Łakomska, I. & Fandzloch, M. Application of 1, 2, 4-triazolo [1, 5-a] pyrimidines for the design of coordination compounds with interesting structures and new biological properties. Coord. Chem. Rev. 327, 221–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2016.04.014 (2016).

Oukoloff, K., Lucero, B., Francisco, K. R., Brunden, K. R. & Ballatore, C. 1, 2, 4-Triazolo [1, 5-a] pyrimidines in drug design. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 165, 332–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.01.027 (2019).

Pinheiro, S. et al. Biological activities of [1, 2, 4] Triazolo [1, 5-a] pyrimidines and analogs. Med. Chem. Res. 29, 1751–1776. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00044-020-02609-1 (2020).

Adawy, H. A., Tawfik, S. S., Elgazar, A. A., Selim, K. B. & Goda, F. E. Design, synthesis, and in vitro and in vivo biological evaluation of Triazolopyrimidine hybrids as multitarget directed anticancer agents. RSC Adv. 14, 35239–35254. https://doi.org/10.1039/D4RA06704E (2024).

Pogaku, V., Gangarapu, K., Basavoju, S., Tatapudi, K. K. & Katragadda, S. B. Design, synthesis, molecular modelling, ADME prediction and anti-hyperglycemic evaluation of new pyrazole-triazolopyrimidine hybrids as potent α-glucosidase inhibitors. Bioorg. Chem. 93, 103307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.103307 (2019).

Abuelizz, H. A. et al. Synthesis, biological activity and molecular Docking of new tricyclic series as α-glucosidase inhibitors. BMC Chem. 13, 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13065-019-0560-4 (2019).

Urakov, G. V. et al. Azolo [5′, 1′, 2, 3] pyrimido [5, 4-e] Tetrazolo [1, 5-c] pyrimidines as dual-action antiglycators and α-glucosidase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 130333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2025.130333 (2025).

Hajlaoui, A., Laajimi, M., Znati, M., Jannet, H. B. & Romdhane, A. Novel pyrano-triazolo-pyrimidine derivatives as anti-α-amylase agents: Synthesis, molecular Docking investigations and computational analysis. J. Mol. Struct. 1237, 130346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.130346 (2021).

Gomha, S. M., Eldebss, T. M., Badrey, M. G., Abdulla, M. M. & Mayhoub, A. S. Novel 4-heteroaryl‐antipyrines as DPP‐IV inhibitors. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 86, 1292–1303. https://doi.org/10.1111/cbdd.12593 (2015).

Wagman, A. S., Johnson, K. W. & Bussiere, D. E. Discovery and development of GSK3 inhibitors for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Curr. Pharm. Design. 10, 1105–1137. https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612043452668 (2004).

Peytam, F. et al. An efficient and targeted synthetic approach towards new highly substituted 6-amino-pyrazolo [1, 5-a] pyrimidines with α-glucosidase inhibitory activity. Sci. Rep. 10, 2595. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-59079-z (2020).

Peytam, F. et al. Design, synthesis, molecular docking, and in vitro α-glucosidase inhibitory activities of novel 3-amino-2, 4-diarylbenzo [4, 5] Imidazo [1, 2-a] pyrimidines against yeast and rat α-glucosidase. Sci. Rep. 11, 11911. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-91473-z (2021).

Peytam, F. et al. Imidazo [1, 2-c] Quinazolines as a novel and potent scaffold of α-glucosidase inhibitors: design, synthesis, biological evaluations, and in Silico studies. Sci. Rep. 13, 15672. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-42549-5 (2023).

Peytam, F. et al. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of novel substituted Imidazo [1, 2-c] Quinazoline derivatives as potential α-glucosidase inhibitors with bioactivity and molecular Docking insights. Sci. Rep. 14, 27507. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78878-2 (2024).

Peytam, F. et al. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of Triazolo [1, 5-a] pyridines as novel and potent α–glucosidase inhibitors. Sci. Rep. 15, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01819-0 (2025).

Merugu, S. R., Cherukupalli, S. & Karpoormath, R. An overview on synthetic and medicinal perspectives of [1, 2, 4] Triazolo [1, 5-a] pyrimidine scaffold. Chem. Biodivers. 19, e202200291. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbdv.202200291 (2022).

Salem, M. A., Behalo, M. S. & Khidre, R. E. Recent trend in the chemistry of Triazolopyrimidines and their applications. Mini-Rev. Org. Chem. 18, 1134–1149. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570193X18666210203155358 (2021).

Zedan, M. N., Shoman, M. E., Abdel-Aziz, M. & Abdel-Rahman, H. M. An overview of the most used synthetic pathways of 1, 2, 4-triazolo [1, 5-a] pyrimidines. Results Chem. 101903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rechem.2024.101903 (2024).

Shao, J. et al. Tuning the annulation reactivity of vinyl Azides and carbazates: A divergent synthesis of aza-pyrimidinones and imidazoles. Org. Lett. 17, 4502–4505. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02180 (2015).

Shu, K. et al. Base-mediated synthesis of highly functionalized 2-aminonicotinonitriles from α-keto vinyl Azides and α, α-dicyanoalkenes. RSC Adv. 6, 49123–49126. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6RA04669J (2016).

Rajaguru, K., Mariappan, A., Muthusubramanian, S. & Bhuvanesh, N. Divergent reactivity of α-azidochalcones with metal β-diketonates: tunable synthesis of substituted pyrroles and Indoles. Org. Chem. Front. 4, 124–129. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6QO00541A (2017).