Abstract

This study investigates the relationship between crystallization behavior, magnetic and mechanical properties, and crack formation in a trachybasaltic glass using differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), Raman spectroscopy, X-ray powder diffraction (XRD), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), vibrating sample magnetometry (VSM), and Vickers indentation tests. Various thermal treatments modify the crystalline cargo (i.e., crystal content), affecting hardness, crack resistance, and magnetism. Single-step annealing at 850 °C rapidly generates nanocrystals, enhancing mechanical strength and inducing ferromagnetic behavior. In contrast, a two-step annealing process (750 °C → 850 °C) promotes gradual magnetite formation, increasing hardness and reducing crack formation while maintaining a predominantly paramagnetic response. These findings suggest that irregular volcanic heating patterns may drive natural crystallization, influencing elastic energy storage and altering failure dynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nanoscale crystals are frequently identified in both the products of volcanic eruptions and industrial processes, covering a broad range of compositions1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Understanding the processes controlling melt viscosity and crystallization in the late eruption stages5,6,9,10; offers useful implications for the glass-ceramic industry11,12. The presence of nanocrystals (nanolites) and their crystallization paths may cause a significant increase in apparent viscosity and mechanical strength of a multiphase mixture, by following: (i) the increase of the solid load13, (ii) Fe-Ti-depleted and Si-enriched shell surrounding the nanolite10,14, and (iii) the enhanced heterogeneous bubble nucleation during magma ascent.

Moreover, basalts are ideal for producing glass-ceramic materials due to their abundance, ease of extraction, and quick production cycles, resulting in remarkable mechanical strength, wear resistance, and corrosion resistance15,16,17,18,19.

In this context, understanding how the heating process and the temperature affects the crystallization (nucleation and growth) is a fundamental step to pursue, as this has a direct impact on the glass properties such as hardness and their attitude to develop and propagate cracks20. Specifically, the resulting microstructure composed of nanocrystals (tens of nanometers in size) uniformly distributed within a residual glassy matrix may increase hardness by up to 30%21. However, although factors such as nanocrystal distribution, total volume fraction, shape, type and their T-dependent evolution are also critical in controlling the macroscopic properties (i.e. mechanical and viscous) of the final products, they are still poorly understood22. In particular, during the crystallization in the supercooled liquid (SCL), trachy-basalts show a remarkable tendency to develop crystals between 700 and 900 °C10,23,24. Indeed, both augite and magnetite nucleate, exhibiting similar Raman bands around 670 cm− 1 and overlapping X-ray diffraction patterns, often making them indistinguishable, although they have significantly different effects on the macroscopic properties of the material1,12.

In this work, we combined differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), Raman spectroscopy, X-ray powder diffraction (XRD), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), vibrating sample magnetometry (VSM), and Vickers tests to correlate the hardness and the crack formation probability to the evolution of the nano-crystalline content in a dry-basaltic glass. Our study aims at clarifying the crystallization path in the SCL region of a standard basalt17,25 by varying the crystal phase proportions (augite and magnetite) and how they impact the hardness and crack formation probability after Vickers indentation upon two kinds of thermal treatment. conducted in a laboratory furnace under ambient air (fO2 ≈ QFM + 4), i.e. atmospheric conditions, ensuring reproducibility across runs.

Results

Differential scanning calorimetry

The DSC thermogram (Fig. 1) of B3 basalt shows a fictive glass transition temperature (Tf) at 658 °C (931 K), where the material changes from a glassy to a supercooled liquid state. Once entering the supercooled liquid field the material shows a weak and broad exothermic bump at the crystallization temperature (Tc,1) of 750 °C (Fig. 1), though its precise identification is tentative given the weak signal and baseline drift, it probably represents the nucleation of magnetite phase26. It is followed by a sharp and strong exothermic peak with an onset at Tc,2 of 845 °C (1116 K in Fig. 1), indicating the beginning of the crystallization process. The sharp exothermic peak, whose onset Tc,2 suggests a rapid and significant crystallization event, corresponds to the typical crystallization peak of augite12. DSC analyses at 20 °C min− 1 were used only to delimit the approximate temperature ranges of initial crystallization and, consequently, design the isothermal annealing experiments at 750 °C and 850 °C, where the crystallization pathways and related properties were investigated.

Raman spectroscopy

The Raman spectra of the samples resulting from the different thermal treatments exhibit the typical shapes of basaltic materials interspersed with fingerprints of nanolites. Spectra of samples thermally treated in the augite crystallization regime (about 850 °C) by varying the isothermal treatment time are reported in Fig. 2a, whilst the evolution stages of the two-step thermal treatment are shown in Fig. 2b. Pristine glass spectrum (sample B3) is reported as a reference presenting the typical features of basalt glass as discussed in Ref25.. The first region (200–600 cm− 1) describes the distribution of rings through the bands R (> 5-membered rings), D1 (4-membered rings), and D2 (3-membered rings)27,28,29. Meanwhile, the 800–1300 cm− 1 region is represented by the symmetric stretching of bridging and non-bridging oxygens24,30,31,32,33. This allows one to understand the evolution of the glassy matrix structure30,34,35 and eventually composition36 during the crystallization process which causes a depletion of elements constituting magnetite and augite from the residual glass phase. Despite the interpretation of the glass signal is highly compromised by the overlap of nanolite peaks (especially the R band of the ring region, 200–450 cm−124,37), a slight shift of the centroid associated with the stretching band to higher wavenumbers can be observed (Fig. 2a), suggesting a slight increase in the polymerization of the glass matrix. Such a result is in agreement with previous findings24. The glass signal is completely lost in the sample B3_60m and in B3_180+, probably because of the high Raman cross-section of magnetite (see Fig. 2b).

Raman spectra of the crystallized glasses, with increasing isothermal holding time at 850 °C in (a). Panel (b) reports the sample isothermally treated at 750 °C for 60 min displaying the typical modes of magnetite (in black) and the two-steps treated sample at 750 °C for 60 min + 850 °C for 180 min (in red). Both panels report the pristine glass (in green).

Just after 5 min (B3_5) at 850 °C, the crystallization is detectable by Raman as evidenced by the formation of the peak around 678 cm− 1. This peak represents both augite and magnetite phases and is assigned to A1g symmetry38,39,40. By 10 min. (B3_10), this peak does not show relevant changes, while a wide and weak bump rises at about 320–330 cm− 1 (also, in this case, refers to the A1g of augite and probably a component of the Eg of magnetite). This indicates an increase in nanocrystal concentration relative to the glass matrix. At 30 min. (B3_30), the peaks strengthen and sharpen further, thus suggesting a continued nanocrystal nucleation and growth that results in an increased crystallinity within the material. After 60 min. (B3_60), the A1g modes of augite at (390, 534 and 1003 cm−141,42) also merge, while at 180 min. (B3_180), the peaks reach their maximum intensity and sharpness, indicating substantial crystallization and a well-defined crystalline structure referred to as augite, in particular the A1g modes at 390, 534 and 1003 cm− 1. It is worth noting that the main “nanolite-peak” shifts toward lower frequencies as the annealing time increases (from 678 to 666 cm−1), suggesting a predominant presence of the augite phase, although contributions from stress effects and compositional variations cannot be excluded43. Raman spectra demonstrate the time-dependent evolution of nano-crystallization, with peaks sharpening and intensifying as the treatment duration increases. The peak shift likely suggests that magnetite and augite coexist in similar proportions during short thermal treatments (likely representing the conditions during the DSC measurement) before evolving into a glass-ceramic where the dominant crystalline phase is progressively represented by augite.

The spectra of sample B3_60m (annealed at 750 °C for 60 min.) and B3_180+, subjected to the two-step treatment (annealed at 750° for 60 minutes and at 850 °C for 180 min.) are reported in Fig. 2b. B3_60m shows the typical spectra of magnetite38,39,40 without any trace of augite peaks, indicating that at this T, only magnetite nucleates, while B3_180 + shows both.

X-Ray powder diffraction

The XRD patterns of all studied samples appear almost indistinguishable (Fig. 3) and all detected peaks can be indexed with augite (ICSD code 009257; Ref44.). Although magnetite reflections are weak and close to the detection limit, they enable a semiquantitative determination of the augite/magnetite ratio. Indeed, its major peaks, namely (103)Mag at 2θ = 35.537° (I% = 100.0) and (121)Mag at 2θ = 35.425° (I% = 82.2) (ICSD code 03115645), fall almost superposed with some augite mean peaks, namely (-131)Aug at 2θ = 35.105° (I% = 29.7), (002)Aug at 2θ = 35.479° (I% = 42.0), and (221)Aug at 2θ = 35.944° (I% = 40.5), as well as do the (112)Mag at 2θ = 30.117° (I% = 33.1) and (200)Mag at 2θ = 30.210° (I% = 23.7) with the (-221)Aug at 2θ = 29.893° (I% = 100.0), (310)Aug at 2θ = 30.508° (I% = 33.8) and (-311)Aug at 2θ = 30.889° (I% = 31.8), respectively. However, when magnetite was included in the quantification routine, consistent results for all samples were obtained, with Aug/Mag ratios varying from 65/35 (B3_5) to 72/28 (B3_180). This crude estimation is sufficient to confirm the presence of magnetite whose association with augite suggests that magnetite may facilitate augite nucleation, though this remains a speculative hypothesis46.

The results (Table 1) show a consistent increase of the average grain size with annealing time, going from ~ 1.9 nm, for samples annealed for 5 min., to ~ 28 nm, for samples annealed for 180 min.

Transmission electron microscopy

All annealed samples show similar TEM micrographs (bright field, BF, Fig. 4) with a clear presence of round- and oval-shaped nanolites ranging from 4 to 50 nm, embedded within an amorphous matrix. However, sample B3_180 (annealed for 180 min., Fig. 4e) shows larger nanolites, i.e., up to 150 nm. Selected-area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns also appear very similar (Fig. 5), apart from minor differences arising from the diverse amounts of material included in the SAED aperture, and therefore the density of diffraction spots and intensity of the diffuse scattering. All patterns are characterized by two more intense and thick diffraction rings at 2.9-3.0 Å and 2.5–2.6 Å. Along these rings fall diffraction spots consistent with the {310} and {-221} planes and the {002}, {−202} and {−131} planes of augite, respectively. As for XRD analysis, the presence of any magnetite diffraction spots, whose most intense reflections would fall within these rings, could not be clearly confirmed.

Nanoparticles suitably oriented for high-resolution electron microscopy (HREM) imaging show for all studied samples lattice fringes with a spacing of ∼6.6 Å, consistent with the (110) planes of augite (Fig. 6). Less frequently, lattice fringes, all consistent with augite, were observed at ∼5.1 Å (001), ∼4.7 Å (200), ∼4.4 Å (1 1–1) and ∼3.0 Å (310). Chemical mapping proved more convincing than TEM to ascertain the presence of magnetite particles. Elemental distribution of Ca, Mg, and Fe within an area of about 400 × 500 nm is reported in Fig. 7 and the direct correlation between the distribution of Ca and Mg indicates the presence of augite nanoparticles. In contrast, the regions where Fe is present without a corresponding correlation with Ca and Mg suggest the presence of magnetite. The higher abundance of augite compared to magnetite suggests that crystallization favors the formation of Ca-Mg-rich silicates over Fe oxides, leading to a dominant augite phase with dispersed, isolated magnetite nanolites (Fig. 7b).

SAED patterns of the samples annealed for: (a) 5 min.; (b) 10 min.; (c) 30 min.; (d) 60 min. Apart from differences arising from the different amount of material included in the SAED aperture, i.e. density of diffraction spots and amount of diffuse scattering, all patterns have the same appearance. In particular, the alignment of spots around two major thick rings at ∼2. 9–3.0 Å and ∼2.5–2.6 Å (arrows and inset), consistent with the {310} and {−221} and {002}, {−202} and {−131} diffracting planes of augite, respectively.

Representative HREM images of selected samples. (a,b) Sample annealed 5 and 10 min. showing an oval nanoparticle (few tens of nm) with lattice fringes spacing of ∼6.6 Å (insets) consistent with the (110) plane of augite. Other nanoparticles, non-suitably oriented for lattice fringe imaging, are visible all around, in particular at the lower side. (a) Moiré fringes (arrow) arising from the superposition of crystalline nanoparticles. (c) The particle at the center-right of the image is augite oriented along [1–1 0] that shows two sets of lattice fringes intersecting at ∼80° with spacing at ∼6.6 and ∼5.1 Å. (d) Magnification of the white box* in (c) showing the augite (110) lattice fringes.

TEM-EDS map of B3_60 (60 min.). (a) BF scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) image of the grain with indication of the measured region (white box). Distribution map of Fe (b), Ca (c) and Mg (d). Note that one can identify Ca/Mg-rich and Fe-rich regions that can be attributed to augite and magnetite, respectively.

Grain-size analyses show that particle size remains stable at ~ 16 nm for short annealing times (5–30 min.), indicating predominant nucleation. After 60 min., the average size increases to ~ 25 nm, and after 180 min. it reaches ~ 75 nm, reflecting a transition to a growth-dominated regime. Consistency with XRD emerges at larger sizes (> 25 nm), while particles below ~ 5 nm may be obscured by larger crystals or appear similar to the glassy matrix due to structural disorder.

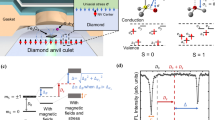

Vibrating sample magnetometry

Figure 8a,b show the magnetization curves of samples B3_5, B3_10, B3_30, B3_60 and B3_180 measured at room temperature. Panel (a) shows the magnetization over the full applied field range (−40000 to 40000 Oe), while (b) zooms in on the central range (−4000 to 4000 Oe) to highlight finer magnetic behavior. All samples exhibit magnetic behavior, though, with distinct characteristics. The samples B3_5, B3_10, B3_30 and B3_60 exhibit a mixed paramagnetic and ferromagnetic behaviors, with a linear increase in magnetization at higher fields, low remanence (Mr), and coercivities (Hc) from 51 to 149 Oe that are in line with results of Ref47.. The B3_60 (60 min.) sample shows the highest magnetization intensity. Sample B3_180 demonstrates predominantly ferromagnetic behavior, as its magnetization tends to saturate for applied fields above 1 T, with intermediate remanence and a higher coercive field, around 460 Oe. With increasing treatment time, the system shifts from mixed paramagnetic/ferromagnetic behavior to predominantly ferromagnetic, indicating that longer treatment stabilizes ferromagnetic phases. Figure 8c,d show the samples: B3_60m treated at 750 °C for 60 min. and B3_180 + treated at 750 °C for 60 min. plus 180 min. at 850 °C. B3_60m and B3_180 + display predominantly superparamagnetic-like behavior, with near-zero coercivity and remanence, and a linear increase in magnetization with applied field at higher fields. With increasing temperature and treatment time (in the augite stability field), B3_180 + exhibits a more intense magnetic response but with low Hc and slightly lower Mr, compared to B3_60m. Magnetite exhibits ferrimagnetic behavior, meaning that when exposed to a magnetic field, its crystal domains adjust their magnetic moments, generating a measurable magnetic response. Ms and Mr increase with crystallinity48, indicating that higher magnetization corresponds to a higher degree of crystallinity. This suggests that extending the treatment time leads to a greater number of crystalline particles. In contrast, coercivity (Hc) behaves differently, as it is more sensitive to factors such as the iron ions, crystal size, and their distribution within the glass matrix14,49. This interpretation is consistent with classical rock magnetic studies, which show that magnetite particles below a critical size of ~ 29–36 nm behave as superparamagnets at room temperature50. Considering our VSM results and the nanoscale domains observed by TEM, we estimate that the effective magnetite grain size in the investigated samples lies within this threshold, supporting the assignment of superparamagnetic-like behavior.

Magnetization curves for samples B3_5, B3_30, B3_60 and B3_180 (a,b) while B3_60m and B3_180+ (c,d). Panels (a) and (c) present the magnetization over the full applied field range (−40000 to 40000 Oe). (b) zooms on the central range (−4000 to 4000 Oe) to highlight finer magnetic behavior. Inset in (b) shows paramagnetic-ferromagnetic evolution, that in (c) the superparamagnetic behavior of B3_60m. (d) shows the evolution of Hc as function of annealing time.

Vickers hardness and crack formation probability

(a) Vickers hardness (HV) values are reported as mean ± 1σ from 10 indentations for 100, 200 and 300 gf and (b) Crack formation probability as a function of the indentation load, as expressed in Newton, in basaltic glass B3 (green circles), crystallized with annealing at 850 °C for 3 h (B3_180, grey triangles) and that with two-step treatment 1 h at 750 °C + 3 h at 850 °C (B3_180+, red diamonds). Labels correspond to the critical load (Pc) for each sample.

The Vickers hardness and the crack formation probability (Fig. 9) after indentation were assessed on the starting trachybasalt and on samples crystallized for 180 min. at 850 °C (single ramp treatment, B3_180) and for 60 min. at 750 °C plus 180 min. at 850 °C (two-step treatment, B3_180+). With increasing the indentation load, the crack formation probability rises for all samples. The untreated trachybasalt glass (B3) shows the highest crack formation probability, reaching 100% at an indentation load of 1000 g. Both thermally treated samples show significantly reduced crack formation probability. The onset shows ca. 80% probability to form cracks in the glass B3 to decrease down to 20% with the two-step treatment (60 min. at 750 °C + 180 min. at 850 °C) exhibiting the lowest crack formation probability. HV slightly increases when the trachybasalt is treated at 850 °C, from 6.1 GPa (glass B3) to 6.4 GPa (B3_180 sample). Notably, HV increases up to 7.5 GPa for the two-step treated sample B3_180 +, which is consistent with the shift of the critical load Pc for 50% crack probability, which rises from ~ 3.3 N in the parent glass to ~ 5.7 N and ~ 7.6 N in the crystallized samples, indicating an overall improvement in crack resistance associated with the nanocrystalline strengthening.

Discussions

The combined Raman, XRD, TEM, and VSM results provide a comprehensive view of the thermal and structural evolution of a synthetic trachybasalt glass (basalt B3) throughout its thermal treatment process, while Vickers tests deliver an insight into the mechanical properties of the samples. After a few minutes (5 and 10 min.) of annealing, a Raman peak around 680 cm−1 indicates the start of nanocrystal formation, which intensifies and sharpens at the expense of the glass signal, i.e. the glass/crystalline signal ratio decreases with annealing time. It turns out very low for the B3_180 and near zero in B3_180+, ending in well-defined crystalline structures whose phase composition is dominated by augite with minor amounts of magnetite. XRD patterns confirm augite as the primary crystalline phase, with magnetite as a minor fraction (35%) that decreases (down to 28%) with increasing annealing time. Regarding the size distribution, both XRD and TEM results together suggest that at 850 °C, the system lies at the stable point of augite nucleation and growth. For relatively short annealing times (5–30 min), TEM images show stable particles with an average size of ~ 16 nm. After 1 h, the average size increases to ~ 25 nm, and reaches ~ 75 nm after 3 h. The two techniques become consistent for larger mean diameters (i.e., those obtained at 60 and 180 min), and therefore we consider the average size estimates reliable only for these three samples. However, in TEM micrographs, crystals smaller than ~ 5 nm may either be obscured by the presence of larger particles or resemble the hosting glassy matrix due to the high degree of disorder typical of rapidly nucleated and grown objects. VSM results confirm what was observed by TEM and XRD, during the single-step treatment at 850 °C, Ms, Mr and Hc increase from about 50 to 150 Oe in the function of time (from 5 to 60 min), indicating an increase in the number of particles and their size14,48.

Comparing the single-step treated sample (B3_180) with the double-step treated one (B3_180+), a drastic drop in Hc is observed. This does not necessarily indicate a reduction in particle size but rather an increase in the number of smaller magnetite particles48. Ms, higher in B3_180+, suggests greater magnetization and, consequently, a higher magnetite content, as confirmed by Raman results. Indeed, sample B3_60m shows only the presence of magnetite (see Fig. 2b) and a glass/crystal signal ratio near to zero suggests a very high crystallization degree.

However, in B3_180, Hc rises drastically to about 460 Oe, highlighting significant crystal growth as a function of time51,52.

The effect of the different treatments on the hardness shows only a slight increase from B3 glass to B3_180, whereas 6.1 GPa for glass B3 to 6.4 GPa for the 180 min treatment sample. However, these values are accompanied by a significant reduction of the crack formation probability that decreases below 50% at 500 g load after 180 min treatment. This behavior can be attributed to the ability of nanocrystals to (i) deviate and deflect the propagation of a crack by subtracting the energy of propagation, reducing the brittle behavior of the glass by favoring the plastic response to the crack nanometric propagation front53,54; (ii) branching at various glass-nanocrystal interface sites due to cleavage of nanolites along specific crystalline planes22, and (iii) change in fracture mode from transgranular to intergranular55. It must be noted that the single-step and two-step treatments are not directly comparable in terms of total thermal budget. Our comparison is therefore qualitative, aimed at illustrating distinct crystallization pathways rather than providing a strictly equivalent thermal history. In our case, we can state that augite contributes significantly in reducing the probability of crack formation. However, the pre-treatment at 750 °C additionally reduces the crack formation probability by 20% at 500 gf (4.9 N) of indentation load. This implies that both size distribution (see the superparamagnetic behavior from VSM data) and quantity (see Raman spectra), of magnetite contributes more significantly than augite to the plasticity of the sample (i.e. by increasing the critical load form 5.7 to 7.6 N). The reasons can be: (i) inhibition of the crack propagation by the effect of the nanolite cargo (size and volume fraction) and the phase (cleavage aligned to the crystalline planes or crack percolation); (ii) different elastic properties distribution depending on bulk effect of nanolites. However, such a variation depends on crystal structure, chemical composition, and interatomic bonds of these two phases. Augite belongs to the pyroxene family, inosilicate with a single-chain structure. The Si-O bonds within its structure are strong, but the presence of cations like Ca and Mg between the chains keeps the overall rigidity of the mineral similar to that of the host glass. The magnetite configuration (cubic spinel crystal structure) ensures greater symmetry and Fe-O bond uniformity, giving the mineral more isotropic elastic properties and higher rigidity. Young’s modulus of augite is around 150 GPa56, which varies depending on its chemical composition and physical conditions while that of magnetite is about 175 GPa57,58. The shear modulus shows similar values for both phases (60 GPa) indicating that augite and magnetite react similarly to shear deformations56,57,59. According to the literature, the bulk modulus is between 100 and 120 GPa for augite60 and 200 GPa for magnetite57, highlighting that the latter is much less compressible. Augite, with its single-chain structure, shows high anisotropy, with elastic properties varying greatly depending on the direction. In contrast, magnetite, thanks to the cubic symmetry of its crystal structure, is more isotropic in its elastic behavior. Density and compressibility also play an important role in their elastic differences: augite has a lower density, ranging from 3.2 to 3.5 g cm−3, making it more compressible, while magnetite, with a higher density of approximately 5.1–5.2 g cm−3, is much less compressible and more resistant to volumetric deformation. Therefore, their behavior under pressure further distinguishes the two minerals. Augite silicate chains show an average bond energy and distances comparable to that of the hosting glass, thus its presence in the system may explain similar HV values between the pure glass (B3) and the crystallized one (B3_180), 6.1 and 6.4 GPa, respectively. On the other hand, magnetite behaves more rigidly and linearly even under very high pressures, thanks to the solidity and uniformity of its cubic structure. The apparent correlation between magnetization and hardness is not due to magnetism per se, but to the microstructural role of magnetite nanocrystals. These rigid inclusions hinder crack propagation and increase the effective stiffness of the glass-ceramic matrix, thereby contributing to the observed strengthening.

In summary, magnetite is stiffer, less deformable, and more isotropic compared to augite, which displays more variable and directional elastic properties that are certainly the cause of their observed contribution in increasing both HV (up to 7.5 GPa) and Pc (up to 7.6 N) of the 2-step crystallized basalt.

Implications

The presence of Fe-rich clusters in volcanic glasses was recently suggested as a good candidate nucleant agent for magnetite, affecting magma behavior61,62,63. These findings align with the observations from related studies indicating that the nucleation of pyroxenes and Fe oxides, such as augite and magnetite, respectively, occur very fast and may influence melt viscosity and mechanical strength by depleting iron from the glass matrix, potentially leading to its increase6,14. This is consistent with the behavior seen in Mt. Etna basalt, where Fe-bearing oxides crystallization significantly impacts melt viscosity10.

Our findings mimic the behavior of a lapilli tuff erupted during one of the Stromboli’s most explosive events64. This formation is a result of the transformation and high-temperature sintering of basaltic scoriae, lapilli, and ash that had originally accumulated as loose tephra and were progressively buried during ongoing volcanic activity. The reheating, thermal annealing, and sintering of pyroclasts (pyrometamorphism) at T > 600 °C is evidenced by subsolidus reactions and partial melting of both mineral phases and glassy groundmass, with subsequent nucleation of other mineral phases (i.e. pyroxene, feldspar and Ti-magnetite). The active vents and shallow conduits of Stromboli are surrounded by a significant volume of these high-temperature rocks, with varying degrees of compaction and sintering. Their mechanical properties differ from those of regular cool rocks, being likely much more resistant, which could, consequently, affect eruptive dynamics.

Here, we show that basalts containing nanolites exhibit greater resistance to cracking, likely due to nanoscale processes that increase the brittle failure limit. Once this limit is exceeded, the material breaks, releasing stored energy in proportion to the nanocristallinity, influencing eruption dynamics.

Conclusions

This study shows a detailed picture of the thermal and structural evolution of a trachy-basalt. The transition from an amorphous glassy state to a predominantly crystalline multiphase system is marked by significant changes in thermal, magnetic behavior and structural characteristics. The early formation of augite as the dominant crystalline phase, followed by magnetite, underscores the complex interplay between thermal conditions and crystallization processes, highlighting the impact of thermal treatment protocols on the crystallization, microstructure, magnetic behavior, and mechanical properties of basaltic glasses.

Single-step annealing at 850 °C for 180 min results in a rapid transition to a nanocrystalline dominated by augite with dispersed magnetite, leading to enhanced mechanical strength and the development of ferromagnetic properties.

In contrast, two-step annealing (750 °C for 60 min followed by 850 °C for 180 min) promotes a more gradual transformation, favoring a magnetite embryo, increased hardness, and a predominantly paramagnetic response. The two-step process results in a more mechanically robust material with a significantly reduction of crack formation.

This suggests that slower, irregular heating, akin to volcanic heat pulses, could influence natural crystallization pathways, increasing the system ability to store elastic energy. Once the plastic-brittle limit is reached, elastic energy will be released, resulting in a catastrophic nano-controlled failure. These experimental findings provide valuable insights into both natural basaltic crystallization and the controlled development of durable glass-ceramics.

While direct extrapolation to volcanic systems is not possible, these experiments highlight the potential influence of nanolite crystallization on the mechanical behavior of vocanic glasses, offering a conceptual framework for interpreting natural observations.

Future studies could explore the specific roles of glass chemistry in the magnetite and augite during crystallization process, as well as their impact on the viscoelastic response of basalts magmas during fragmentation.

Materials and methods

Materials

The selected starting material (B3) is a trachybasalt glass produced by melting a powdered oxide mix at 1500 °C for 2 h, quenched on a copper plate, remelted for homogenization, and annealed at Tg for 1 h before cooling at 2 °C min−117,25. B3 has a glass transition temperature Tg at 648 °C and a Fe3+/ΣFe ratio (measured by Mössbauer spectroscopy) of 0.79. Chemical composition, Tg and a Fe3+/ΣFe ratio are reported in Table 2.

Methods

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and thermal treatment

In order to retrieve the temperatures at which the system changes state (glass to supercooled liquid) and crystallizes, we thermally analyze the B3 glass by using a simultaneous thermogravimetric analyser and differential scanning calorimeter (TGA-DSC 3+, Mettler Toledo). Polished glass chips (~ 80 mg) from each sample were placed in an alumina crucible and heated from room temperature (RT) to 900 °C at a rate of 20 °C min− 1 under an air flow of 100 mL min− 1 to erase the sample thermal history. The temperature was then reduced to 200 °C at the same rate (20 °C min− 1) and re-heated with the same rate up to 900 °C. The onset of the crystallization temperature was determined through the tangent method.

The temperature selected for crystallization was primarily guided by the results of the DSC. The glass samples were heated in a muffle furnace from room temperature to the selected Tcs at 20 °C min− 1 and held at that temperature for the target times. Each isothermal treatment is reached by ramps 20 °C min− 1. After each isothermal treatment, the furnace was turned off and the sample immediately removed to cool in ambient air. This quenching procedure corresponds to very high cooling rates (10–100 °C s− 1), effectively suppressing further crystallization during cooling. For each annealing at least two independent samples were prepared and analyzed, yielding consistent phase assemblages and mechanical properties. Reported values are therefore representative of reproducible results. All experiments were conducted under constant laboratory air conditions to ensure comparability across treatments.

Raman spectroscopy

Raman spectra were recorded using a Thermo Scientific DXR2 spectrometer with solid-state lasers operating at 532 nm. Scattered light was dispersed by a custom interchangeable grating and detected with a thermoelectrically cooled charge-coupled device (CCD). The grating provided a spectral range on the Stokes side from 50 to 1875 cm− 1, with an average resolution of 1 cm− 1 and a minimum detectable frequency of 50 cm− 1. The laser power on the sample surface was set to 10 mW, and no signs of surface alteration from laser exposure were observed. To address weak luminescence, a linear background correction was applied (see Refs17,25,34. as example).

X-Ray powder diffraction (XRD)

XRD analyses were performed with a Bragg–Brentano PANalytical X’Pert-Pro PW3060 diffractometer with θ–θ geometry and CuKα radiation. Spectra were collected in the 5–80° 2θ range with a step size of 0.02°, at room temperature and operating conditions of 40 mA and 40 kV. Representative amounts of the studied samples were powdered in an agate mortar and wet-loaded on a 0-background silicon holder. Phase identification and semi-quantitative phase analysis, with the reference intensity ratio (RIR) method65, were carried out with the PANalytical X’Pert High Score software, using the ICSD PDF2-2004 database.

The average grain size of crystallites (D) forming in the glass during annealing was estimated from XRD patterns through the Scherrer Equation66, which relates the Full Width Half Maximum (FWHM) of the peaks to the crystal size:

where K is the Scherrer constant (assumed = 0.94 as for spherical crystals with cubic symmetry), λ is the wavelength (0.15406 nm), β is the FWHM and θ is the Bragg angle (in radians). The instrumental broadening as function of θ was estimated through an Al2O3 (corundum) standard. The average grain size was estimated measuring the FWHM of the most intense peak (I100) occurring in the diffractograms between 29.72 and 29.80 2θ° values. The average grain size (\(\:{D}_{c}\)) corrected for instrumental broadening (βi) is therefore calculated as:

where βs is the FWHM of the I100 peak, n = 2 for Gaussian profiles, which better describe instrumental broadening.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

A small amount of the same powder studied by XRD was dispersed in isopropyl alcohol and ultrasonicated for 3 min. 5 µL of the suspension was then deposited on 300 mesh Cu grids supporting a carbon membrane. TEM investigations were performed with a JEOL JEM 2100P instrument, operating at 200 kV and equipped with an Oxford energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) for microanalysis and a Gatan Rio CMOS camera for image acquisition. TEM images were analyzed by superimposing reference grid on each micrograph selecting 3 portions with at least 50 clearly measurable particles each. Image processing was carried out in Fiji (ImageJ, 2.14.0, https://fiji.sc/)67. Prior to analysis, images were converted to 8-bit grayscale, and thresholding was applied to distinguish particles from the background. When necessary, touching or overlapping particles were separated using the built-in watershed algorithm. Only well-defined particles entirely contained within the selected grid squares were considered, while incomplete or poorly resolved particles were excluded. For each particle, the Feret’s diameter (maximum caliper distance) was measured, as it provides a robust estimate of size even for slightly elongated or irregular shapes. The mean particle size were calculated from the combined dataset of the three selected grid squares and used to represent the overall particle size distribution.

Vibrating sample magnetometry (VSM)

Room temperature magnetization measurements were conducted using a vibrating sample magnetometer module from Quantum Design DynaCool to assess the magnetic properties of the synthetic basaltic glass (B3) before and after the thermal treatments. The measurements were performed in magnetic fields ranging from − 4 to 4 T.

Microhardness

The Vickers Hardness (HV) of all three samples was evaluated at room temperature using a Future Technology FM-310 microhardness tester, with an applied load of 100, 200 and 300 gf. Before testing, the samples were mounted in an epoxy resin and polished. For each sample, 10 indentations were performed. To assess crack formation probability, the applied loads were varied as follows: 100, 200, 300, 500, 1000, and 2000 gf. The contact duration between the tip and sample was 5 s, and cracks were observed and counted 20 s after indentation. The percentage of crack formation, X, was determined using the formula below68,

Here the denominator “4” represents the number of radial crack arms counted per indentation and \(\:{x}_{i}\) is the number of corners with cracks at the i indentation. We define the critical load (Pc) as the indentation load at which radial cracks are observed in 50% of the imprints.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Di Genova, D., Caracciolo, A. & Kolzenburg, S. Measuring the degree of nanotilization of volcanic glasses: Understanding syn-eruptive processes recorded in melt inclusions. Lithos 318–319, 209–218 (2018).

Giordano, D. et al. Viscosity of Palmas-type magmas of the Paraná magmatic Province (Rio Grande do Sul State, Brazil): Implications for high-temperature silicic volcanism. Chem. Geol. 560, 119981 (2021).

Mujin, M. & Nakamura, M. Late-stage groundmass differentiation as a record of magma stagnation, fragmentation, and rewelding. Bull. Volcanol. 82(6), 48 (2020).

Okumura, S. et al. Rheology of nanocrystal-bearing andesite magma and its roles in explosive volcanism. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 1–7 (2022).

Cáceres, F. et al. Can nanolites enhance eruption explosivity? Geology 48(10), 997–1001 (2020).

Pereira, L. et al. The rheological response of magma to nanolitisation. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 448, 108039 (2024).

González-García, D. et al. Retrieving dissolved H2O content from micro-Raman spectroscopy on nanolitized silicic glasses: Application to volcanic products of the Paraná magmatic Province, Brazil. Chem. Geol. 567, 120058 (2021).

Valdivia, P. et al. Nanoscale chemical heterogeneities control the viscosity of andesitic magmas. Commun. Earth Environ. 6, 455 (2025)

Bamber, E. C. et al. 3D quantification of nanolites using X-ray ptychography reveals syn-eruptive nanocrystallisation impacts magma rheology. Nat. Commun. 16, 7083 (2025).

Di Genova, D. et al. In situ observation of nanolite growth in volcanic melt: A driving force for explosive eruptions. Sci. Adv. 6, 1–13 (2020).

Liu, C. et al. Preparation and dielectric properties of the amorphous basaltic glass. Silicon 14, 3623–3628 (2022).

Klein, J. M. et al. Microstructure and mechanical properties of a nucleant-free basaltic glass-ceramic. Mater. Sci. Technol. (United Kingdom). 35, 544–551 (2019).

Hornby, A. J. et al. Nanoscale silicate melt textures determine volcanic Ash surface chemistry. Nat. Commun. 15, 1–10 (2024).

Cáceres, F. et al. Oxide nanolitisation-induced melt iron extraction causes viscosity jumps and enhanced explosivity in silicic magma. Nat. Commun. 15(1), 604 (2024).

Khater, G. A., Abdel-Motelib, A., Manawi, E., Abu Safiah, M. O. & A. W. & Glass-ceramics materials from basaltic rocks and some industrial waste. J. Non Cryst. Solids. 358, 1128–1134 (2012).

de Lima, L. F., Zorzi, J. E. & Cruz, R. C. D. Basaltic glass-ceramic: A short review. Bol. la. Soc. Esp. Ceram. Y Vidr https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bsecv.2020.07.005 (2020).

Cassetta, M., Zanatta, M., Biesuz, M., Giarola, M. & Mariotto, G. New insights about the role of Na–K ratio on the vibrational dynamics of synthetic-basalt glasses. J. Raman Spectrosc. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrs.6298 (2022).

Kuzmin, K. L., Gutnikov, S. I., Zhukovskaya, E. S. & Lazoryak, B. I. Basaltic glass fibers with advanced mechanical properties. J. Non Cryst. Solids. 476, 144–150 (2017).

Tarrago, M., Royo, I., Martínez, S., Garcia-Valles, M. & Neuville, D. R. Incorporation of calcium in glasses: A key to understand the vitrification of sewage sludge. Int. J. Appl. Glas Sci. 12, 367–380 (2021).

Jensen, M. et al. Hardness of basaltic glass-ceramics. Glas Technol. Eur. J. Glas Sci. Technol. 50, 2–7 (2009).

Lima, L. F., Mantas, P. Q., Segadães, A. M. & Cruz, R. C. D. Processing and characterization of sinter-crystallized basalt glass-ceramics. J. Non Cryst. Solids. 538, 120019 (2020).

Deng, B., Harris, J. T. & Luo, J. Atomic picture of crack propagation in Li2O-2SiO2 glass-ceramics revealed by molecular dynamics simulations. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 103, 4304–4312 (2020).

Arzilli, F. et al. Magma fragmentation in highly explosive basaltic eruptions induced by rapid crystallization. Nat. Geosci. 12, 1023–1028 (2019).

Cassetta, M. et al. Micro-Raman spectroscopy for a comprehensive Understanding of the structural evolution of Basaltic-Andesite and Trachybasalt multiphase systems. Chem. Geol. 616, 121241 (2023).

Cassetta, M. et al. Effect of the alkali vs iron ratio on glass transition temperature and vibrational properties of synthetic basalt-like glasses. Spectrochim Acta - Part. Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 293, 122430 (2023).

Scarani, A. et al. A chemical threshold controls nanocrystallization and degassing behaviour in basalt magmas. Commun. Earth Environ. 3(1), 284 (2022).

Galeener, F. L. Band limits and the vibrational spectra of tetrahedral glasses. Phys. Rev. B 19, 4292–4297 (1979).

Matson, D. W., Sharma, S. K. & Philpotts, J. A. The structure of high-silica alkali-silicate glasses. A Raman spectroscopic investigation. J. Non Cryst. Solids. 58, 323–352 (1983).

McMillan, P. & Piriou, B. Raman spectroscopic studies of silicate and related glass structure: A review. Bull. Mineral. 106, 57–75 (1983).

Cassetta, M. et al. Deep-UV Raman spectroscopy: A novel heuristic method to characterize volcanologically relevant glasses on Mars. Chem. Geol. 644, 121867 (2024).

Di Muro, A. et al. Micro-Raman determination of iron redox state in dry natural glasses: Application to peralkaline rhyolites and basalts. Chem. Geol. 259, 78–88 (2009).

Schiavi, F. et al. Water quantification in silicate glasses by Raman spectroscopy: Correcting for the effects of confocality, density and ferric iron. Chem. Geol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2018.02.036 (2018).

Giordano, D. et al. A calibrated database of Raman spectra for natural silicate glasses: Implications for modelling melt physical properties. J. Raman Spectrosc. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrs.5675 (2019).

Cassetta, M. et al. Boson peak and elastic moduli in the Na2O-SiO2 system. Minerals 13, 1166 (2023). Viscosity.

Enrichi, F. et al. Effect of the crystal structure on the optical properties and ag sensitization of Tb3+/Yb3 + ions in silica-zirconia glasses and glass-ceramics. Ceram. Int. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.10.036 (2022).

González-García, D., Giordano, D., Russell, J. K. & Dingwell, D. B. A Raman spectroscopic tool to estimate chemical composition of natural volcanic glasses. Chem. Geol. 556, 119819 (2020).

Di Genova, D. et al. Effect of iron and nanolites on Raman spectra of volcanic glasses: A reassessment of existing strategies to estimate the water content. Chem. Geol. 475, 76–86 (2017).

Huang, E., Chen, C. H., Huang, T., Lin, E. H. & Xu, J. A. Raman spectroscopic characteristics of Mg-Fe-Ca pyroxenes. Am. Mineral. 85, 473–479 (2000).

Wang, A., Jolliff, B., Haskin, L. A., Kuebler, K. E. & Viskupic, K. M. Characterization of structures and compositions of quadrilateral pyroxenes by Raman Spectroscopy - Implications for future planetary exploration. Am. Mineral. 86, 790–806 (2001).

Shebanova, O. N. & Lazor, P. Raman spectroscopic study of magnetite (FeFe2O4): A new assignment for the vibrational spectrum. J. Solid State Chem. 174, 424–430 (2003).

Buzatu, A. & Buzgar, N. The Raman study of Single-Chain silicates. “Analele Stiint ale Univ” Al I Cuza” Din. Lasi. Geol. 56, 107–125 (2010).

Tribaudino, M., Mantovani, L., Bersani, D. & Lottici, P. P. Raman spectroscopy of (Ca,Mg)MgSi2O6 clinopyroxenes. Am. Mineral. 97, 1339–1347 (2012).

Tribaudino, M. et al. High-pressure Raman spectroscopy of Ca(Mg,Co)Si2O6 and Ca(Mg,Co)Ge2O6 clinopyroxenes. J. Raman Spectrosc. 48, 1443–1448 (2017).

Takeda, H. & I Ridley, W. Crystallography and chemical trends of orthopyroxene-pigeonite from rock 14310 and coarse fine 12033. Proc. Lunar Sci. Conf. 3, 423–430 (1972).

Hamilton, W. C. Extinction effects in neutron scattering from single magnetic crystals. Acta Crystallogr. 11, 585–594 (1958).

Gutnikov, S. I., Malakho, A. P., Lazoryak, B. I. & Loginov, V. S. Influence of alumina on the properties of continuous basalt fibers. Russ J. Inorg. Chem. 54, 191–196 (2009).

Francis, A. A. Crystallization kinetics of magnetic glass-ceramics prepared by the processing of waste materials. Mater. Res. Bull. 41, 1146–1154 (2006).

Avancini, T. G., Souza, M. T., de Oliveira, A. P. N., Arcaro, S. & Alves, A. K. Magnetic properties of magnetite-based nano-glass-ceramics obtained from a Fe-rich scale and borosilicate glass wastes. Ceram. Int. 45, 4360–4367 (2019).

Pham, T. N., Huy, T. Q. & Le, A. T. Spinel ferrite (AFe2O4)-based heterostructured designs for lithium-ion battery, environmental monitoring, and biomedical applications. RSC Adv. 10, 31622–31661 (2020).

Dunlop, D. J. Superparamagnetic and single-domain threshold sizes in magnetite. J. Geophys. Res. 78, 1780–1793 (1973).

Hou, Y., Zhang, G. H. & Chou, K. C. Effect of atmosphere control on magnetic properties of CaO-Al2O3-SiO2-Fe3O4 glass ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 41, 2663–2673 (2021).

Wence et al. Migration mechanism and magnetic properties of Fe ions in glass–ceramics of an iron-rich CMAS system. Glas Phys. Chem. 49, 463–477 (2023).

Wang, B., Yu, Y., Wang, M., Mauro, J. C. & Bauchy, M. Nanoductility in silicate glasses is driven by topological heterogeneity. Phys. Rev. B. 93, 1–5 (2016).

Célarié, F. et al. Glass breaks like Metal, but at the nanometer scale. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 4 (2003).

Fu, Q. et al. Tough, bioinspired transparent glass-ceramics. Adv. Eng. Mater. 24, 1–10 (2022).

Aleksandrov, K. S. & Ryzhova, T. V. A. The elastic properties of rock-forming minerals, I: Pyroxenes and amphiboles. Izv. Acad. Sci. USSR Geophys. 9, 1339–1344 (1961).

Chicot, D. et al. Mechanical properties of magnetite (Fe3O4), hematite (α-Fe2O3) and goethite (α-FeO·OH) by instrumented indentation and molecular dynamics analysis. Mater. Chem. Phys. 129, 862–870 (2011).

Zou, Y. et al. Thermally induced anomaly in the shear behavior of magnetite at high pressure. Phys. Rev. Appl. 10, 1 (2018).

Reichmann, H. J. & Jacobsen, S. D. High-pressure elasticity of a natural magnetite crystal. Am. Mineral. 89, 1061–1066 (2004).

Nestola, F., Ballaran, B., Tribaudino, T., Ohashi, H. & M. & Compressional behaviour of CaNiSi2O6 clinopyroxene: Bulk modulus systematic and cation type in clinopyroxenes. Phys. Chem. Min. 32, 222–227 (2005).

Szewczyk, D. & Cassetta, M. Colossal low-temperature upturn in the heat capacity of volcanic glasses. J. Non Cryst. Solids. 637, 123046 (2024).

Cormier, L., Galoisy, L., Lelong, G. & Calas, G. Fromnanoscale heterogeneities to nanolites: Cation clustering in glasses. Comptes Rendus Phys. 24, 199–214 (2023).

Dubosq, R. et al. Bubbles and atom clusters in rock melts: A chicken and egg problem. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 428, 107574 (2022).

Del Moro, S., Renzulli, A., Landi, P., La Felice, S. & Rosi, M. Unusual Lapilli tuff ejecta erupted at stromboli during the 15 March 2007 explosion shed light on the nature and thermal state of rocks forming the crater system of the volcano. J. Volcanol Geotherm. Res. 254, 37–52 (2013).

Snyder, R. L. & Bish, D. L. Modern Powder Diffraction: Quantitative Analysis (De Gruyter, 1989). https://doi.org/10.1515/9781501509018-008

Patterson, A. L. The scherrer formula for X-ray particle size determination. Phys. Rev. 56, 978–982 (1939).

Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682 (2012).

Sorarù, G. D. et al. On the structure and properties of hydrothermally toughened soda–lime silicate float glass. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 107, 5383–5399 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Authors acknowledge support from PNRR M4C2 - PRIN 2022PXHTXM - STONE - A new generation Spectroscopy Tool to monitor rheology and phase trans- formation prOcesses in volcaNology and cEramic production funded by the European Union – Next Generation EU. Authors acknowledge Marco Giarola and Centro Piattaforme Tecnologiche (CPT) of the University of Verona for technical support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.C.: conceptualization; methods; data analysis; writing original manuscript. G.C.C., R.C., S.L.F., D.G., M.B., B.G.S., J.F.D.F.A., T.D.R., C.Z., F.E. and N.D.: methods; data analysis; writing, review and editing. D.G. and N.D.: funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cassetta, M., Capitani, G.C., Chaudhary, R. et al. Nanolite cargo evolution in trachybasaltic glass comparing magnetite and augite. Sci Rep 15, 39170 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23410-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23410-3