Abstract

Triple-negative apocrine carcinoma (TNAC) is a rare and chemotherapy-insensitive subtype of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), characterized by specific morphology and molecular features. Despite limited chemotherapy response, TNAC shows favorable long-term survival, suggesting distinct resistance mechanisms. In this study, we present the first proteomics-based profiling of TNAC formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples using mass spectrometry. Our analysis reveals progressive activation of PI3K/AKT and androgen receptor (AR) signaling, along with upregulation of GTPase-related proteins, suggesting enhanced invasiveness. Post-chemotherapy TNAC displays increased inflammation and mixed ribosomal regulation, pointing to a metabolic shift in survival strategy. These findings support the rationale for exploring chemotherapy de-escalation strategies in TNAC, and highlight the potential utility of PI3K/AKT inhibitors and AR antagonists, possibly in combination with GTPase inhibitors, metabolic disruptors, or immunotherapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Triple-negative apocrine carcinoma (TNAC) is a rare and chemo-insensitive subtype of breast cancer. While apocrine carcinoma (AC) accounts for 0.4–4% of all breast cancers, TNAC, representing approximately 1% of triple-negative breast cancers (TNBCs), making it one of the least studied subtypes1,2,3,4,5. TNBC is defined by the absence of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2/ Erb-B2 Receptor Tyrosine Kinase 2 (ERBB2, also known as HER2), which limits targeted treatment options and often leads to aggressive clinical behavior5,6. Despite its rarity, TNAC differs from non-apocrine triple-negative breast cancer (NA-TNBC) by exhibiting low Ki67 expression and consistent androgen receptor (AR) positivity, which may contribute to a lower proliferative index and distinct therapeutic vulnerabilities7,8,9.

AC is characterized by apocrine morphology, including large tumor cells, eosinophilic cytoplasmic granules, and prominent nucleoli10,11. It can present as ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) or invasive carcinoma. Originating from epithelial cells within the terminal ductal lobular units, DCIS remains confined within the ducts, while invasive breast cancer penetrates the basement membrane and stroma, requiring systemic therapies to prevent or manage metastasis. According to the World Health Organization, invasive apocrine carcinoma is defined by tumors in which over 90% of cells exhibit apocrine morphology12. Understanding the molecular mechanisms driving this progression is crucial for developing effective treatment strategies.

TNAC exhibits poor response to chemotherapy yet better long-term survival, sparking interest in personalized treatment approaches4,7,9,13,14,15,16. While multidrug chemotherapy remains a standard treatment for malignant tumors, neoadjuvant chemotherapy—administered before surgery to shrink tumors—is increasingly utilized6,17,18. However, its side effects and variable efficacy have led to a growing focus on identifying patients who may not benefit from chemotherapy19,20. In ER+/PR+ and HER2+ breast cancers, treatment decisions are carefully guided by chemo-exemption strategies21,22,23,24. In TNBC, immunotherapy (e.g., pembrolizumab) and AR-targeted therapies are emerging alternatives25,26,27,28. Increasing evidence suggests that TNAC patients may not benefit from chemotherapy, prompting discussions on chemo-exemption to optimize treatment and reduce unnecessary toxicity9,16.

Our team previously conducted a retrospective clinical and statistical analysis of 41 TNAC cases, alongside data from the SEER database, and found that TNAC responds poorly to neoadjuvant therapy yet exhibits better short-term prognosis compared to other TNBCs, likely due to its low proliferative nature9. Although prior genomic studies have classified TNAC subtypes and proposed potential therapeutic targets29,30, the molecular mechanisms underlying these clinical observations remain incompletely understood, and proteomics-based analyses are still lacking. To address this, we employed mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomics to systematically profile dysregulated proteins and pathways in TNAC, along with assessing chemotherapy response to elucidate potential mechanisms of treatment resistance. Whole-exome sequencing (WES) was also incorporated to explore somatic mutations that may contribute to proteomic alterations. Together, this study presents a proteogenomic view of TNAC, with a primary focus on proteomic alterations, contributing to the development of precision oncology strategies for this rare TNBC subtype.

Results

Clinical and pathological characteristics of samples

In order to explore TNAC as a unique tumor type, we collected formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples from 31 patients diagnosed with invasive TNAC (Supplementary Table S1). The general workflow is pictured in Fig. 1a. The median age of patients at diagnosis was 57 years, ranging from 38 to 79. Of the 31 patients, 41.9% (13/31) were at TNM stage I, 45.2% (14/31) at stage II, and 12.9% (4/31) at stage III. Sample morphology was evaluated and confirmed by two pathologists, and protein markers were verified by immunohistochemical staining (IHC). Example IHC and Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) images are shown in Fig. 1b,c. All patients were negative for the hormone receptors ER and PR, and lacked HER2 amplification, consistent with other TNBCs. In contrast, they were mostly AR positive and had low Ki67 expression. The average duration of storage for FFPE samples was 1869 days, ranging from 229 to 3185 days. Ten patient samples contained DCIS components. Seven patients received neoadjuvant chemotherapy prior to surgery, and their needle biopsy FFPE specimens were also collected. Among these seven patients, three were at TNM stage II, two were at stage III, and one was at stage I, with a median age of 54 (from 46 to 63). Pathological response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy was assessed using the Miller–Payne (MP) grading system on a five-point scale: four patients had a grade 2, and three had a grade 3. In total, 78 samples were collected for this study, comprising 30 adjacent tissues (referred to as “normal” tissues), 10 DCIS tissues, and 38 invasive tissues (from 31 patients, including 7 pre-chemotherapy biopsies). All FFPE tissues were analyzed by MS, and invasive and matched normal tissues from three patients were also analyzed by WES.

Overview of the experimental design and representative H&E and IHC images of clinical samples. (a) Breast cancer patient samples were collected through needle biopsies prior to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and from surgical resections. FFPE sections were pathologically reviewed to confirm TNAC diagnosis. Normal, DCIS, and invasive tumor regions were dissected for mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomic profiling, with selected samples also subjected to whole-exome sequencing (WES). Bioinformatic analyses were conducted to identify dysregulated proteins, altered pathways, and potential mechanisms underlying tumor progression and chemoresistance. Our findings support the rationale for chemotherapy de-escalation and highlight the potential utility of targeted therapies such as PI3K inhibitors. (b) Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of Ki67, HER2 (ERBB2), EGFR, and AR in normal, DCIS, and invasive TNAC tissues. Scale bar = 50 μm. (c) Representative H&E-stained images of normal breast tissue, TNAC DCIS, TNAC invasive carcinoma, and NA-TNBC invasive carcinoma. Scale bar = 50 μm. (d) Principal component analysis (PCA) clustering shows a clear separation of normal, DCIS, and invasive TNAC tissues, indicating distinct molecular profiles. (e) Boxplots displaying MS-based expression levels of EGFR (top) and HER2/ERBB2 (bottom) across normal, DCIS, and invasive TNAC tissues (*p < 0.05).

Proteomic and functional analysis of TNAC progression

To investigate the molecular features underlying TNAC initiation and progression, we performed MS-based proteomic profiling on invasive tumors, DCIS lesions, and adjacent normal tissues. In total, 5952 protein groups were quantified at a 1% FDR for both peptides and proteins (Supplementary Table S2). Across tissue types, we identified 4399 proteins from 34,136 peptides in normal samples, 4427 proteins from 33,392 peptides in DCIS, and 5842 proteins from 54,048 peptides in invasive tumors. Representative H&E and IHC images are shown in Fig. 1b,c. Principal component analysis (PCA) (Fig. 1d) revealed distinct clustering of normal, DCIS, and invasive tissues, underscoring progressive molecular divergence.

Consistent with previous studies7,9,11,13,14,29, TNAC tumor tissues in our cohort frequently expressed AR and EGFR, whereas ER, PR, and Ki-67 were generally low or undetectable. At the cohort level, these patterns were reflected in both MS-based proteomics and IHC results (Fig. 1b,e). EGFR was strongly expressed, and AR was detectable in invasive regions, while ER, PR, and Ki-67 were absent in the proteomic data. HER2, observed in some IHC images of DCIS and invasive tumors, showed a similar trend in MS data, with low abundance in normal tissues and gradual upregulation in DCIS and invasive TNAC. Certain low-abundance proteins, such as GCDFP-15, were observed by IHC but not detected by MS, likely reflecting sensitivity limitations of proteomics31. We emphasize that the IHC images in Fig. 1b illustrate individual cases and are not intended to represent cohort-wide averages; rather, they provide pathological context that complements the proteomic profiles. Overall, the proteomic and IHC findings were consistent at the trend level and aligned with previously reported TNAC expression profiles7,9,11,13,14,29, supporting the robustness of the dataset for downstream functional analysis.

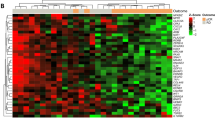

Proteomic and network analysis of TNAC tumor progression. (a) Heatmap showing variations in protein expression across normal, DCIS, and invasive TNAC tissues. Each cell represents the standardized score of protein abundance in an individual sample, with colors indicating relative expression levels. (b) Venn diagram showing the number and percentage of significantly altered proteins unique to or shared among normal, DCIS, and invasive groups. (c) Co-expression network of protein modules identified by WGCNA. A total of 3277 proteins were grouped into five modules (ME0–ME4), each represented by a distinct color. ME0 contains unclustered proteins and serves only as a reference, while ME1–ME4 correspond to functional modules enriched for distinct biological processes. (d) Correlation heatmap of module eigengenes (ME1–ME4) with clinical groups (normal, DCIS, invasive TNAC). ME0 represents unclustered proteins and is shown only as a reference. Positive correlations are shown in red, negative correlations in blue, with color intensity proportional to the correlation coefficient. (e) Module–trait relationships for pre- versus post-chemotherapy samples, highlighting treatment-associated shifts in module expression. (f) Signaling pathways illustrating the upregulation of proteins involved in PI3K/AKT, androgen receptor (AR) signaling in invasive TNAC. The figure highlights the increased expression of key regulators, including PI3K, AKT, mTOR, AR, and RAC.

We further analyzed differential protein expression, identifying 2309 proteins that mark the transition from DCIS to invasive TNAC (Supplementary Table S3). Hierarchical clustering revealed distinct profiles for normal, DCIS, and invasive tissues, with DCIS showing an intermediate pattern (Fig. 2a). The Venn diagram (Fig. 2b) showed that 3418 proteins (52%) were shared across all groups, while invasive tumors had the largest unique set (1308 proteins, 20%), indicating substantial proteomic remodeling at invasion. DCIS and normal tissues had fewer unique proteins (257 and 431, respectively), reflecting their closer molecular similarity. To explore coordinated protein expression changes, weighted correlation network analysis (WGCNA) was conducted (Fig. 2c), grouping a total of 3277 proteins into five modules (ME0–ME4). ME0 represents unclustered proteins and serves only as a reference. ME1, associated with Golgi vesicle transport and protein localization, indicates altered intracellular trafficking. ME2, linked to MYC targets and oxidative phosphorylation, highlights metabolic reprogramming in TNAC. ME3, containing extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling and epithelial–mesenchymal transition-related proteins, reflects structural components often linked to tumor–stroma interactions; its higher eigengene value in normal tissues likely reflects abundant stromal ECM rather than active EMT. ME4, enriched in chromatin DNA-binding proteins, suggests transcriptional and epigenetic regulation. Bilateral clustering revealed that ME3 was most prominent in normal tissues and ME1/ME2 in invasive tumors, illustrating a progressive molecular shift—i.e., a stepwise reprogramming of protein expression modules—from tumor initiation to invasion (Fig. 2d).

Differential expression analysis identified significant changes in key biological pathways associated with TNAC progression (Fig. 3; Supplementary Table S3). A total of 1647 proteins were upregulated, and 463 were downregulated in invasive tumors compared to normal tissues. Invasive TNAC exhibited increased cadherin binding and GTPase activity, supporting cell adhesion modulation and cytoskeletal reorganization, whereas ECM was downregulated, indicating progressive loss of structural integrity. Comparisons between DCIS and normal tissues showed cadherin binding and ligase activity enrichment while ECM-associated proteins were downregulated, resembling patterns observed in invasive TNAC. Additionally, invasive tumors displayed enrichment in GTPase activity and guanyl ribonucleotide binding proteins, whereas DCIS retained ECM-associated proteins, suggesting different tumor microenvironment adaptations at distinct disease stages. Interestingly, actin binding was markedly downregulated in DCIS compared to both normal and invasive TNAC samples. This may reflect cytoskeletal remodeling during early tumorigenesis or reduced migratory activity, though we cannot exclude technical variation due to tissue fixation or sampling artifacts. Further studies are warranted to validate these observations.

Differential expression and functional enrichment analysis of TNAC normal, DCIS, and invasive tissues. (Left) Volcano plots illustrating differentially expressed proteins across three comparisons: invasive vs. normal, DCIS vs. normal, and invasive vs. DCIS. The x-axis represents log2 fold change, while the y-axis represents –log10 p-value. Significantly altered proteins (p < 0.05, |log2 fold change| > 1) are highlighted in black. (Middle) Top enriched Gene Ontology (GO) terms for upregulated proteins in each comparison, categorized by molecular functions and biological processes (p < 0.05, log₂ fold change > 1). The numbers beside the dots represent fold enrichment. The dot size represents the number of proteins involved, while the color gradient indicates the adjusted p-value. (Right) Top enriched GO terms for downregulated proteins in each comparison (p < 0.05, log₂2fold change < − 1). The numbers beside the dots represent fold enrichment. The dot size corresponds to the number of proteins in each category, and the color represents statistical significance (adjusted p-values). The results highlight distinct molecular features of TNAC progression, including cadherin and GTPase binding in invasive tumors and extracellular matrix remodeling in DCIS.

The gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) further highlighted key oncogenic drivers of TNAC (Supplementary Table S3). The Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/ Protein kinase B (PKB, also known as AKT) signaling was significantly enriched across tumor progression (p < 0.01). Similarly, AR signaling was activated in invasive TNAC vs. DCIS (p-value = 0.035), reinforcing its role in tumor progression and potential therapeutic relevance. These findings indicate that targeting PI3K/AKT and AR signaling could offer therapeutic opportunities in TNAC, which we will discuss in detail in the following paragraph. The analysis also revealed metabolic and immune adaptations, including increased mitochondrial translation in invasive TNAC, dysregulated cholesterol synthesis in DCIS, and complement pathway inhibition in both tumor types, possibly contributing to immune evasion. The epigenetic regulatory processes were more active in invasive TNAC, while DCIS tumors exhibited increased activity in scavenging by class A receptors, suggesting early-stage microenvironmental adaptations.

PI3K/AKT and AR pathway activation in TNAC progression

The PI3K/AKT pathway has long been recognized as a key driver and therapeutic target in breast cancer32,33,34. While PIK3CA somatic mutations were less frequently detected in TNBC compared to other breast cancer subtypes35, certain TNBC subtypes exhibit higher PI3K mutation rates, making PI3K inhibitors a potential treatment option33,36. In TNAC, genomic studies have consistently identified mutations in PIK3CA, PIK3R1, PTEN, and TP53, highlighting PI3K/AKT pathway activation as a hallmark of this subtype29,30. Lyman et al. classified TNAC into six molecular subgroups based on gene expression, including the luminal androgen receptor (LAR) subtype, which Kim et al. found to be the most common TNAC subtype, accounting for approximately 40% of cases29,37. While previous genomic studies failed to detect mutations in the AR gene in TNAC29,30, our proteomics analysis confirms AR overexpression in invasive TNAC tissues, reinforcing its role in tumor biology.

Cross-talk between AR and PI3K/AKT signaling is well established in prostate cancer38,39,40,41,42,43, and our proteomic data suggest a similar interaction in TNAC. Invasive TNAC tissues exhibited marked upregulation of PI3K catalytic and regulatory subunits (PIK3CB, PIK3R1, PIK3R2), AKT isoforms (AKT1, AKT2), and mTOR, relative to both DCIS and normal tissues (Fig. 2f), indicating activation of proliferative and pro-survival signaling. Concurrently, AR expression was elevated, accompanied by increased levels of AR coactivators—CARM1, UBE2I, and KDM1A—consistent with enhanced AR transcriptional activity. GTPase signaling components RAC1 and MAPK1 were also upregulated, implicating cytoskeletal remodeling and motility programs that may contribute to invasive behavior. Notably, the IHC images in Fig. 1b illustrate individual TNAC cases from the same specimens analyzed by MS and are shown as pathological context, whereas the quantitative cohort-wide expression profiles are presented in Fig. 2f. Together, these findings point to coordinated activation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR and AR pathways, alongside RAC1-driven cytoskeletal reorganization, supporting the potential application of PI3K inhibitors, AR antagonists, and RAC1-targeting agents to mitigate TNAC progression and invasion.

WES analysis of TNAC tumors

WES analysis was performed on three invasive TNAC tumors and their matched adjacent non-tumor breast tissues, which served as comparators. The average read count was ~ 66 million in normal samples and ~ 75 million in tumor samples, with approximately 30% of reads duplicated. More than 99% of reads were mapped to the reference genome, achieving an average sequencing depth of 120× and > 99% coverage of the target regions. Figure 4 provides an overview of the WES results.

Differential analysis between tumor and matched adjacent non-tumor tissues identified 32 mutated genes, with splice site mutations representing the most frequent mutation type, followed by in-frame insertions and deletions (Fig. 4a). The most common single nucleotide variation (SNV) class was C > T transitions (Fig. 4b). Genomic profiling revealed the top ten mutated genes (Fig. 4c). Notably, no mutations were detected in PIK3CA, the catalytic subunit of PI3K, which has frequently been reported in TNAC. This absence may reflect inter-patient genetic variability, limited sensitivity in FFPE-derived DNA, or the small sample size (n = 3). In support of this possibility, a prior study reported PIK3CA mutations in only 16% of TNAC cases29, indicating such mutations occur in a subset rather than universally.

Comparison of WES results with proteomic data identified twelve genes with both genomic alterations and measurable protein expression changes: ACE2, C3, COL18A1, DNM3, HCLS1, MAL2, NRDC, NUP54, OLFM4, PRKCSH, SMARCA2, and TNS1 (Fig. 4d). Variants likely representing known SNPs were excluded based on dbSNP and Ensembl annotations. Among the remaining candidates, C3 showed the most pronounced protein downregulation, suggesting a potential cis-effect of its genomic alteration. Two splice site variants were detected in C3 (chr19:6690742, A > G, and chr19:6679511, C > T; the latter annotated as an SNP), present in all three tumor samples with reduced C3 protein abundance. However, without RNA-seq data, it is not possible to confirm whether these mutations result in exon skipping or transcript instability, and peptide-level proteomics did not reveal evidence of exon skipping or mis-splicing.

Other notable splice site variants included ACE2 (chrX:15610348, C > T) and MAL2 (chr1:120220775, CG > C), the latter reported as a high-impact variant predicted to cause protein truncation or loss of function[EJBC 2020;23:e25, Supplementary 3]. Nonsense mutations were observed in TNS1 (chr2:218712886, G > GinsGCTGC, TNA), HCLS1 (chr3:121351315, G > GinsGGCTCAGGCTCA), and NUP54 (chr4:77065320, G > GinsTTA), with only TNS1 showing concordant protein downregulation in both invasive and primary tumors. An in-frame deletion in COL18A1 (chr21:46924426_46924434delGGCCCCCCA) resulted in NM_030582:exon33:c.3364_3364del: p.G1122fs and NM_130444:exon33:c.4069_4069del: p.G1357fs. In-frame deletions were identified in NRDC (chr1:52306064_52306066delTCT) and SMARCA2. Representative mutations are shown in Fig. 4e.

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) analysis of three invasive TNAC tumors and their corresponding adjacent non-tumor TNAC breast tissues. (a) Variant classification of identified mutations, with splice site variants being the most frequent. (b) Single nucleotide variant (SNV) type distribution, showing that the predominant mutation type is C > T. (c) Top 10 most frequently mutated genes, with bars representing the number of mutations and the percentage of TNAC patients harboring them. (d) Integration of WES and proteomics data, highlighting 12 genes that are both mutated and exhibit significant differential protein expression (p < 0.01, |log2 fold change| > 1). (e) Schematic representation of mutations in COL18A1 and NRDC, illustrating the mutation sites (lollipops) detected in TNAC tumors. Colors indicate different mutation classifications, and the length of each stick represents the number of patients with the mutation.

Several of these genes are functionally relevant to tumor biology or immunity. C3 encodes complement component 3, a central regulator of the complement cascade, with roles in B-cell activation and immune modulation44. Reduced C3 protein levels in TNAC may reflect immune suppression or altered complement signaling in this subgroup. COL18A1, encoding collagen type XVIII alpha 1, has been reported as overexpressed in high-grade breast cancer and associated with poor prognosis and resistance to HER2-targeted therapy45. In our dataset, we detected an in-frame deletion in COL18A1 in invasive TNAC tissues, with proteomic data suggesting reduced expression. This preliminary observation requires validation in larger cohorts. NRDC (nardilysin), a zinc metalloendopeptidase, has been linked to cytokine regulation, tumor progression, and membrane protein shedding46,47. We observed an in-frame deletion in NRDC across all three sequenced tumors, though its functional consequence remains unclear.

Given the small sample size, these observations should be considered exploratory. Nevertheless, the concordance between genomic alterations and proteomic changes in a subset of genes—particularly those involved in extracellular matrix remodeling and immune signaling—suggests potential relevance to TNAC pathogenesis and provides a rationale for further validation in larger cohorts.

Molecular adaptations in chemotherapy-resistant TNAC

This study investigates the molecular impact of chemotherapy on intrinsically resistant cancer tissue, focusing on proteomic changes before and after treatment in patients known to exhibit poor chemotherapy response yet high overall survival rates. We first performed a PCA plot and heatmap analysis on proteomic profiles of four groups: pre-chemotherapy normal, pre-chemotherapy invasive, post-chemotherapy normal, and post-chemotherapy invasive (Fig. 5a,b). The distinct clustering patterns indicate substantial differences between normal and invasive samples, as well as between pre- and post-chemotherapy states. The ellipses suggest that post-chemotherapy invasive samples cluster more closely together, whereas pre-chemotherapy normal samples exhibit a broader distribution, reflecting a higher degree of heterogeneity. We then focused on pre- and post-chemotherapy invasive samples. The Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC), PCA, and heatmap results are consistent (Fig. 5c–e), showing that post-chemotherapy invasive samples form a more cohesive cluster, whereas pre-chemotherapy samples exhibit more variability. This suggests that chemotherapy alters the proteomic landscape of invasive tumors, potentially driving a more uniform molecular state. Differential analysis shows that 306 proteins were downregulated, 334 proteins were upregulated (p < 0.05, |Fold change| > 1.5), and 3238 proteins remained unchanged (Fig. 5f; Supplementary Table S4).

Proteomic profiling and functional analysis of pre- and post-chemotherapy TNAC samples. (a) Principal component analysis (PCA) plot showing distinct clustering of pre- and post-chemotherapy samples, with separation between normal and invasive tissues. (b) Heatmap illustrating global protein expression changes between pre- and post-chemotherapy groups. Each column represents a sample, and the color scale indicates relative protein abundance. (c) Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC) heatmap demonstrating hierarchical clustering of pre- and post-chemotherapy invasive samples. (d) PCA of invasive samples pre- and post-chemotherapy. (e) Heatmap of differentially expressed proteins between pre- and post-chemotherapy invasive samples, illustrating significant changes in protein expression patterns. (f) Volcano plot displaying significantly upregulated (red) and downregulated (blue) proteins in post-chemotherapy invasive samples compared to pre-chemotherapy samples (p < 0.05, |Fold change| > 1.5). (g) GSEA showing significantly upregulated and downregulated KEGG pathways in post-chemotherapy samples. (h) Protein–protein interaction (PPI) network of key functional categories enriched in post-chemotherapy samples. Nodes represent proteins, with red indicating upregulation and blue indicating downregulation.

The GSEA results revealed significant differences in biological processes between post- and pre-chemotherapy TNAC samples, particularly in immune response, metabolism, and cellular structure regulation (Fig. 5g; Supplementary Table S4). Notably, pathways related to immune activation, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, complement and coagulation cascades, and neutrophil extracellular trap formation, were significantly upregulated after chemotherapy, suggesting an increased inflammatory response and immune system engagement. In contrast, pathways associated with metabolism, such as fatty acid metabolism, bile secretion, and calcium signaling, were downregulated post-chemotherapy, indicating metabolic shifts that may reflect altered tumor cell adaptability or stress responses. Moreover, the suppression of focal adhesion and cytoskeletal organization pathways suggests potential chemotherapy-induced effects on tumor cell migration and invasion.

The PPI analysis further supports these findings by showing distinct alterations in functional protein clusters post-chemotherapy (Fig. 5h). Proteins related to ribosomal structure and biogenesis (RPS23, RPS25, RPS28, RPL5, RPL26, RPL28, RPLP1, RPL39, EIF6, GTPBP4) exhibited mixed regulation, indicating selective changes in protein synthesis machinery, which may reflect cellular stress responses or adaptive resistance mechanisms. In contrast, lipid metabolism proteins (APOA1, APOA2, APOC1, APOC3, AMBP) and acute-phase response proteins (A2M, ORM1, ORM2, SERPINA1, SERPINC1, SERPIND1, HRG, HBB, TTR) were consistently upregulated post-chemotherapy. This suggests a potential increase in inflammatory and stress response proteins, reinforcing the KEGG findings on immune activation. Similarly, the upregulation of ECM proteins (VTN, AHSG, RBP4, TF, LYZ) aligns with the observed enrichment of complement and coagulation cascades, indicating remodeling of the tumor microenvironment in response to treatment.

These findings complement the WGCNA results, which capture global co-expression patterns across the proteome. WGCNA identified four major modules with distinct functional enrichments, including Golgi vesicle transport (ME1), MYC targets/oxidative phosphorylation (ME2), extracellular matrix remodeling/EMT (ME3), and chromatin DNA binding (ME4) (Fig. 2c). Comparison of pre- and post-chemotherapy samples (Fig. 2e) revealed enrichment of ME1 after treatment, while ME2 and ME3 were higher before treatment. This suggests that chemotherapy suppresses broad ECM and metabolic/translational programs while enhancing trafficking-related and secretory pathways. The apparent increase of certain ECM or secretory proteins in the PPI analysis likely reflects selective upregulation within a generally downregulated ECM/EMT module, indicating a shift from proliferative/EMT programs toward inflammatory and secretory adaptation in residual tumor cells.

Together, these analyses suggest that post-chemotherapy TNAC tumors undergo significant immune activation, metabolic reprogramming, and ECM remodeling. While chemotherapy may induce stress responses that affect ribosomal activity and protein synthesis, it also enhances inflammatory and acute-phase responses, which could either contribute to tumor suppression or therapy resistance. Understanding these molecular adaptations is crucial for identifying potential vulnerabilities and developing targeted therapeutic strategies for TNAC. Our findings on post/pre-chemotherapy TNAC proteomics profiles align with Anurag et al.’s study of chemotherapy resistance and response in TNBC, highlighting metabolism reprogramming as a key resistance mechanism48. However, unlike TNBC, which relies on DNA damage repair and enhanced translation, TNAC exhibits mixed ribosomal regulation and a stronger inflammatory response, suggesting a distinct adaptation strategy. These distinct molecular features suggest that TNAC may require a different therapeutic approach, emphasizing metabolic and immune-targeting strategies rather than conventional chemotherapy regimens.

Discussion

This study presents the first proteomics-based characterization of TNAC, a rare subtype of TNBC that shows resistance to standard chemotherapy yet favorable long-term outcomes. By profiling normal breast tissues, DCIS, and invasive TNAC using mass spectrometry, we identified molecular features associated with tumor progression and chemoresistance.

Invasive TNACs exhibited elevated expression of proteins involved in PI3K/AKT and AR signaling, pathways known to promote oncogenic growth and survival. This shift suggests increasing dependence on growth factor and hormone-mediated signaling during progression. Gene Ontology analysis revealed substantial ECM remodeling and increased expression of GTPase-regulated proteins, supporting enhanced motility and invasion. WGCNA analysis highlighted two modules relevant to TNAC biology: ME2, enriched for MYC-driven oxidative phosphorylation, and ME3, containing ECM remodeling and epithelial–mesenchymal transition-related proteins. These modules reflect potential metabolic plasticity and structural components that may differ across disease stages.

WES of three TNAC tumor–adjacent normal pairs revealed a small number of candidate somatic variants, including alterations in extracellular matrix–related genes (e.g., COL18A1) and immune regulators (e.g., C3). Reduced C3 protein abundance in all C3-mutant tumors raises the possibility of impaired complement activation and altered tumor–immune interactions in this subgroup, although functional consequences remain to be determined. The small cohort size limits the strength of biological conclusions. We observed recurrent events such as an in-frame deletion in NRDC and an in-frame deletion in COL18A1, but confirmation of their relevance will require validation in larger patient populations. Given the small sample size, these genomic findings should be considered exploratory and hypothesis-generating, providing preliminary insights and a rationale for future investigation in expanded cohorts.

Proteomic comparison of TNAC tumors before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy revealed distinct molecular adaptations. Despite limited clinical response, post-treatment tumors exhibited increased expression of metabolic adaptation proteins such as ORM1, ORM2, APOA2, and AHSG, suggesting a metabolic shift toward lipid metabolism and activation of acute-phase response pathways. This phenotype implies that TNAC tumors may evade chemotherapy not through clonal expansion of proliferative cells, as is common in conventional TNBCs, but through metabolic flexibility and stress response activation. Such mechanisms contrast with the high Ki67 expression and proliferation-driven chemoresistance typically observed in other TNBC subtypes37,49,50.

As the analysis was performed on macrodissected FFPE samples, the proteomic profiles likely contain contributions from adjacent stromal and immune components, particularly in post-chemotherapy specimens where immune infiltration may be more pronounced. While this heterogeneity may influence specific molecular readouts, it also provides an opportunity to capture biologically relevant aspects of the tumor microenvironment, offering complementary insights into tumor–stroma and tumor–immune interactions. Our use of paired samples—before and after treatment, and normal versus tumor—together with stringent statistical thresholds, helps mitigate background effects while retaining this broader biological context. The observed signatures remain consistent with known TNAC biology and are supported by multiple independent lines of evidence. Nevertheless, this characteristic of macrodissected samples underscores the value of future studies incorporating spatial proteomics, laser-capture microdissection, or single-cell approaches to more precisely resolve tumor-intrinsic molecular changes.

Given these findings, an important clinical question arises: Does standard chemotherapy truly benefit TNAC patients, or could alternative, less toxic therapies yield superior outcomes? The persistence of metabolic and immune adaptation signatures after chemotherapy suggests that TNAC tumors may survive independently of rapid proliferation. This could explain why TNAC patients often demonstrate favorable long-term survival despite poor initial chemotherapy response. Consequently, targeted strategies—such as metabolic inhibitors, immune-modulating agents, or lipid metabolism disruptors—may be more effective than conventional cytotoxic regimens. These observations reinforce the need for biomarker-driven treatment stratification, as a subset of TNAC tumors may remain clinically indolent without requiring aggressive therapy.

Therapeutic de-escalation may thus be justified in selected TNAC patients. In particular: PI3K inhibitors (e.g., Alpelisib, Copanlisib) target oncogenic signaling and survival pathways commonly activated in AR-positive TNBC and may be effective in TNAC51,52,53; AR-targeted therapies (e.g., Enzalutamide) are rational combinations with PI3K blockade and have shown benefit in preclinical and clinical studies of AR + TNBC54,55; Oxidative phosphorylation inhibitors (e.g., IACS-010759) may exploit metabolic vulnerabilities arising from enhanced mitochondrial respiration in TNAC56; RAC-GTPase inhibitors (e.g., EHT1864)57 may restrain cytoskeletal dynamics and cell motility implicated in TNAC, even though global ECM/EMT signals are reduced in our cohort; Immune checkpoint blockade, especially PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors, is currently under evaluation in TNBC, and our data suggest that post-chemotherapy TNAC tumors exhibit increased inflammation and complement activation—features that may sensitize them to immunotherapy58,59. While no TNAC-specific therapy trials have been conducted to date, these findings support the rationale for exploring precision medicine approaches in this histologically and molecularly distinct TNBC subtype.

In conclusion, this study provides a comprehensive proteogenomic characterization of TNAC, identifying PI3K/AKT and AR pathway enrichment as key features of invasive progression and revealing metabolic reprogramming as a mechanism of chemotherapy resistance. Our findings suggest that TNAC tumors evade chemotherapy through adaptive survival strategies rather than rapid proliferation, challenging the necessity of standard chemotherapy in this subtype. These insights support a shift toward biomarker-driven therapies primarily targeting PI3K/AKT and AR pathways, with potential consideration for GTPase inhibitors, metabolic interventions, as well as immune therapy, to improve TNAC treatment outcomes.

Methods

Tissue samples

All of the cases diagnosed as invasive breast apocrine carcinoma between 2008 and 2021 in Peking University Hospital were retrieved and reviewed by two senior pathologists. The diagnostic criteria include a minimum of 95% of the tumor displaying apocrine differentiation, tumor cells with a minimum Nuclear: Cytoplasm ratio of 1:2, abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, distinct nucleoli, and well-defined cell boundaries. Patients with positive expression in ER or PR were excluded. Patients with HER2-amplification were also excluded. A total of thirty-one cases of invasive TNAC were included for proteomic analysis. The FFPE blocks used in this study were obtained from Peking University Cancer Hospital in Beijing, China, with approval from the hospital’s ethical committee under reference number 2020KT113. The cells were stained using H&E, and the expression of protein markers such as ER, PR, and HER2 was evaluated using IHC, as described in a previous publication9. Out of the 31 invasive TNAC cases, 10 still contained accompanying DCIS lesions; therefore, invasive, DCIS, and adjacent normal tissues (~ 10 μm thick) were carefully dissected from the FFPE blocks on a macroscopic level. In addition, seven patients had received neoadjuvant therapy, and FFPE samples of their needle biopsies taken before chemotherapy were included in the study. The survival of these patients was evaluated using the Miller–Payne grading system.

Sample preparation for proteomics analysis

Paraffin of FFPE samples was solubilized by xylene, and protein pellets were washed with ethanol. The ethanol was removed completely and the sections were left to air-dry. Samples were lysed with a buffer containing 4% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 0.1 M DTT (Sigma, 43815), and 1 mM PMSF (Amresco, M145). The collected solution was mixed with pre-cold acetone in a 4:1 ratio. After precipitating the proteins with acetone, they were further washed with cooled acetone. The protein precipitation was then redissolved in 200 µL of 8 M urea solution. The protein concentration was determined by the bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Thermo Scientific, 23227). Samples containing 100 µg of proteins were first reduced with 10 mM dithiothreitol at 56 °C for 30 min and alkylated with 10 mM iodoacetamide at room temperature (RT) in the dark for an additional 30 min. Then, the samples were digested by trypsin using the filter-aided proteome preparation method. Specifically, the samples were transferred into a 30 kD Microcon filter (Millipore, MRCF0R030) and centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 20 min. The precipitate on the filter was washed twice by adding 300 µL of washing buffer (8 M urea in 100 mM Tris, pH 8.0) into the filter and then centrifuged again at 14,000 × g for 20 min. The precipitate was then resuspended in 200 µL of 100 mM NH4HCO3. Trypsin was added to the filter at a protein-to-enzyme ratio of 50:1 (w/w), and the proteins were digested at 37 °C for 16 h. After this, peptides were collected by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 20 min and dried in a vacuum concentrator (Thermo Scientific).

MS analysis

The dried peptide samples were re-dissolved in Solvent A (0.1% formic acid in water) and loaded onto a trap column (100 μm × 2 cm, home-made; particle size, 3 μm; pore size, 120 Å; SunChrom, USA) under a maximum pressure of 280 bar using Solvent A. The samples were then separated on a home-made 150 μm × 12 cm silica microcolumn (particle size, 1.9 μm; pore size, 120 Å; SunChrom, USA) with a gradient of 5–35% mobile phase B (acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid) at a flow rate of 300 nL/min for 120 min.

The eluted peptides were ionized under 2.2 kV. MS operated under a data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode. For detection with the Orbitrap Eclipse mass spectrometer, a precursor scan was performed in the Orbitrap by scanning m/z 300–1500 with a resolution of 60,000. Then, MS/MS scanning was carried out in the Orbitrap by scanning m/z 200–1400 with a resolution of 15,000. The most intense ions selected under top-speed (3 s) mode were isolated in Quadrupole with a 1.6 m/z window and fragmented by higher energy collisional dissociation (HCD) with a normalized collision energy of 32%. The maximum injection time was set to 40 ms for full scans and 30 ms for MS/MS scans. Dynamic exclusion time was set as 30 s.

MS data processing

All MS data were processed in the Maxquant (v 1.6.17.0) platform. The raw files were searched against the human National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) ref-seq protein database (updated on 07-04-2013, 32,015 entries). Mass tolerances were set at 10 ppm for precursor ions and 0.05 Da for product ions. Up to two missed cleavages were allowed. Carbamidomethylation at cysteine was specified as a fixed modification, while acetylation at protein N-terminus and oxidation at methionine were considered as variable modifications. The data were also searched against a target-decoy database to ensure identifications were accepted at a false discovery rate of 1% at both peptide and protein levels. Proteins were classified into protein groups when identified peptides could not differentiate protein isoforms and homologues. The Maxquant-iBAQ labeling-free quantitation method was applied to evaluate protein abundances. Missing values were imputed using minimum values in the corresponding sample. An R package “DEP” (v 1.16.0) was used for data preprocessing and manual examination of data. Before processing, the proteins were filtered to ensure the number of missing values was below half of the smallest sample size condition. The filtered datasets were then log2-transformed and normalized by variance stabilizing transformation to eliminate the effect of different variances among proteins in differential expression protein list.

Differential expression analysis

Differential protein expressions were analyzed using the R package “limma” (v 3.50.0). Specifically, a separate linear model was fit for each protein, and contrasts were then tested. Empirical Bayes moderation was performed to achieve more accurate estimates of protein-wise variability. Generally, proteins with an adjusted p-value < 0.05 and a |log2 Fold change| > 1 or |Fold change| > 1.5 were identified as differentially expressed proteins.

GO enrichment analysis

For the GO enrichment analysis, the R package “clusterProfiler” (v 4.2.2) with default parameters was applied. We focused on enriching “BP” (biological process) and “MF” (molecular function) subontology terms. The default background—consisting of the entire human proteome—was used for the analysis.

GSEA

For GSEA enrichment analysis of tumor progression, the R package “clusterProfiler” (v 4.2.2) with default parameters was utilized by the following annotated gene sets from the Molecular Signatures Database (v 2023.2.Hs): H (hallmark gene sets), CP (canonical pathways gene sets), and C5 (ontology-gene sets). Pathways with an adjusted p-value < 0.05 were identified as significantly altered pathways. For GSEA enrichment analysis of chemotherapy impact, the R package “ClusterProfiler” (v4.2.2) was used to conduct enrichment analysis of KEGG-based geneset60,61, with an adjusted p-value < 0.05 as the cutoff.

WGCNA

WGCNA analysis was performed to identify protein modules during TNAC tumor development using R package “WGCNA” (v 1.72-5). 3277 proteins that passed filtering were used for co-expression network construction. Power 10 was selected as the soft threshold as it fits a scale-free topology model well (R2 = 0.87) while preserving connectivity of 40.72. A signed network was constructed to keep track of the sign of the co-expression information. A topological overlap measure (TOM) was used to evaluate the network interconnectedness, and protein modules composed of highly connected proteins were then identified by hierarchical clustering. The modules identified using the blockwise Modules function were further annotated using the compare Cluster function in the R package “cluster Profiler.” This was based on annotation gene sets from Molecular Signatures Database, including H (hallmark gene sets), CP (canonical pathways gene sets), and C5 (ontology-gene sets). The top significantly enriched terms (adjusted p < 0.01) were manually selected to summarize the functions of the modules.

WES

WES was conducted on invasive TNAC tumors and their corresponding adjacent non-tumor breast tissues from three TNAC patients (ID T001808541, T002002780, T001994386). The exome sequences were efficiently enriched from 0.4 µg genomic DNA using Agilent SureSelect Human All Exon V6 (Agilent USA, Catalog #: 5190-8864) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Firstly, qualified genomic DNA was randomly fragmented to an average size of 180–280 bp by Covaris LE220R-plus (Covaris, USA). The remaining overhangs were converted into blunt ends via polymerase-exonuclease complex activities. Secondly, DNA fragments were end-repaired and phosphorylated, followed by A-tailing and ligation at the 3’ends with paired-end adapters. DNA fragments with ligated adapter molecules on both ends were selectively enriched in a PCR reaction. After the PCR reaction, libraries hybridize with the liquid phase with a biotin-labeled probe, then use magnetic beads with streptomycin to capture the exons of genes. Captured libraries were enriched in a PCR reaction to add index tags to prepare for sequencing. Products were purified using AMPure XP system (Beckman Coulter, Beverly, USA), libraries were analyzed for size distribution by Agilent 5400 system (AATI) (Agilent, USA) and quantified by real-time PCR (Life Technologies, USA) (1.5 nM). The qualified libraries were pooled and sequenced on Illumina platforms with PE150 strategy in Novogene Bioinformatics Technology Co., Ltd (Beijing, China), according to effective library concentration and the data amount required.

The sequencing reads were then aligned to the hg19 reference genome using BWA (v 0.7.8-r455), and the depth was checked by Sambamba (v 0.6.8). Aligned BAM files were processed by SAMtools (v 1.9) to identify the SNP sites and INDEL sites. The SNP sites were annotated using ANNOVAR (v 2017June8) with reference databases, including Refseq, dbSNP, 1000 genome, GO, and KEGG. The final annotations were consolidated into MAF format. Subsequent analyses were conducted based on the samples’ origin using maftools and manual scripts. No threshold for statistical significance was applied.

Data availability

The MS-based proteomics data have been deposited in the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the data set identifier PXD054737. Reviewers may access them through the following link with the code TEdF: https://www.iprox.cn/page/PSV023.html;?url=1758694176415c5EB The WES data generated in this study are available in the China National Center for Bioinformation (CNCB) under the accession number PRJCA046728 through the following link: https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/bioproject/browse/PRJCA046728.

References

Sun, K. et al. Incidence, mortality, and disability-adjusted life years of female breast cancer in China, 2022. Chin. Med. J. (Engl). 137, 2429–2436. https://doi.org/10.1097/CM9.0000000000003278 (2024).

Mills, A. M., Atkins, K. A. & C, E. G., S, M. W., C, M. B. & Pure apocrine carcinomas represent a clinicopathologically distinct androgen receptor-positive subset of triple-negative breast cancers. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 40, 1109–1116. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000000671 (2016).

Wu, W., Wu, M., Peng, G., Shi, D. & Zhang, J. Prognosis in triple-negative apocrine carcinomas of the breast: A population-based study. Cancer Med. 8, 7523–7531. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.2634 (2019).

Arciero, C. A. et al. Triple-negative apocrine carcinoma: A rare pathologic subtype with a better prognosis than other triple-negative breast cancers. J. Surg. Oncol. 122, 1232–1239. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.26129 (2020).

Moss, J. L., Tatalovich, Z., Zhu, L., Morgan, C. & Cronin, K. A. Triple-negative breast cancer incidence in the united states: ecological correlations with area-level sociodemographics, healthcare, and health behaviors. Breast Cancer. 28, 82–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12282-020-01132-w (2021).

van den Ende, N. S. et al. Triple-Negative breast cancer and predictive markers of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy: A systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24032969 (2023).

Saridakis, A. et al. Apocrine breast cancer: unique features of a predominantly Triple-Negative breast cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 28, 5610–5616. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-021-10518-9 (2021).

Schwartz, C. J. et al. Triple-negative apocrine carcinomas: toward a unified group with shared molecular features and clinical behavior. Mod. Pathol. 36, 100125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.modpat.2023.100125 (2023).

Hu, T. et al. Triple-Negative apocrine breast carcinoma has better prognosis despite poor response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J. Clin. Med. 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11061607 (2022).

Thomas, A., Reis-Filho, J. S., Geyer, C. E. Jr. & Wen, H. Y. Rare subtypes of triple negative breast cancer: current understanding and future directions. NPJ Breast Cancer. 9, 55. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-023-00554-x (2023).

Vranic, S. et al. Apocrine carcinoma of the breast: a comprehensive review. Histol. Histopathol. 28, 1393–1409. https://doi.org/10.14670/HH-28.1393 (2013).

Tan, P. H. et al. The 2019 world health organization classification of tumours of the breast. Histopathology 77, 181–185. https://doi.org/10.1111/his.14091 (2020).

Dellapasqua, S. et al. Immunohistochemically defined subtypes and outcome of apocrine breast cancer. Clin. Breast Cancer. 13, 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clbc.2012.11.004 (2013).

Vranic, S. et al. Immunohistochemical and molecular profiling of histologically defined apocrine carcinomas of the breast. Hum. Pathol. 46, 1350–1359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2015.05.017 (2015).

Tsutsumi, Y. Apocrine carcinoma as triple-negative breast cancer: novel definition of apocrine-type carcinoma as estrogen/progesterone receptor-negative and androgen receptor-positive invasive ductal carcinoma. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 42, 375–386. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hys034 (2012).

Montagna, E. et al. Prognosis of selected triple negative apocrine breast cancer patients who did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy. Breast 53, 138–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2020.07.003 (2020).

Hassan, M. S., Ansari, J., Spooner, D. & Hussain, S. A. Chemotherapy for breast cancer (review). Oncol. Rep. 24, 1121–1131. https://doi.org/10.3892/or_00000963 (2010).

Chiappa, C. et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer: evaluation of the impact on surgical outcomes and prognosis. Cancers (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16132332 (2024).

Jiang, L. et al. Prospective observational study on biomarkers of response in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat. Med. 30, 749–761. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02790-x (2024).

Ulukaya, E., Karakas, D. & Dimas, K. Tumor chemosensitivity assays are helpful for personalized cytotoxic treatments in cancer patients. Med. (Kaunas). https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57060636 (2021).

Sparano, J. A. et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy guided by a 21-Gene expression assay in breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 111–121. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1804710 (2018).

Kalinsky, K. et al. 21-Gene assay to inform chemotherapy benefit in node-positive breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 385, 2336–2347. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2108873 (2021).

Piccart, M. et al. 70-gene signature as an aid for treatment decisions in early breast cancer: updated results of the phase 3 randomised MINDACT trial with an exploratory analysis by age. Lancet Oncol. 22, 476–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00007-3 (2021).

Swain, S. M., Shastry, M. & Hamilton, E. Targeting HER2-positive breast cancer: advances and future directions. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 22, 101–126. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41573-022-00579-0 (2023).

Schmid, P. et al. Pembrolizumab for early Triple-Negative breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 810–821. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1910549 (2020).

Traina, T. A. et al. Enzalutamide for the treatment of androgen Receptor-Expressing Triple-Negative breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 36, 884–890. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.71.3495 (2018).

Michmerhuizen, A. R., Spratt, D. E., Pierce, L. J. & Speers, C. W. ARe we there yet? Understanding androgen receptor signaling in breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer. 6, 47. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-020-00190-9 (2020).

Grellety, T., MacGrogan, G., Chakiba, C., Kind, M. & Bonnefoi, H. Long-term complete response of an androgen receptor-positive triple-negative metastatic breast cancer to abiraterone acetate. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2, 0. https://doi.org/10.1200/PO.17.00223 (2018).

Kim, J. Y. et al. Genomic characteristics of triple negative apocrine carcinoma: a comparison to triple negative breast cancer. Exp. Mol. Med. 55, 1451–1461. https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-023-01030-z (2023).

Sun, X. et al. Invasive apocrine carcinoma of the breast: clinicopathologic features and comprehensive genomic profiling of 18 pure triple-negative apocrine carcinomas. Mod. Pathol. 33, 2473–2482. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-020-0589-x (2020).

Meissner, F., Geddes-McAlister, J., Mann, M. & Bantscheff, M. The emerging role of mass spectrometry-based proteomics in drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 21, 637–654. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41573-022-00409-3 (2022).

Garg, P. et al. Strategic advancements in targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway for breast cancer therapy. Biochem. Pharmacol. 236, 116850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2025.116850 (2025).

Raphael, J., Desautels, D., Pritchard, K. I., Petkova, E. & Shah, P. S. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitors in advanced breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cancer. 91, 38–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2017.12.010 (2018).

Liu, L., Graff, S. L. & Wang, Y. New emerging therapies targeting PI3K/AKT/mTOR/PTEN pathway in hormonal Receptor-Positive and HER2-Negative breast Cancer-Current state and molecular pathology perspective. Cancers (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17010016 (2024).

Martinez-Saez, O. et al. Frequency and spectrum of PIK3CA somatic mutations in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 22, 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-020-01284-9 (2020).

Zhang, H. P. et al. PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway: an important driver and therapeutic target in triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 31, 539–551. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12282-024-01567-5 (2024).

Lehmann, B. D. et al. Identification of human triple-negative breast cancer subtypes and preclinical models for selection of targeted therapies. J. Clin. Investig. 121, 2750–2767. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI45014 (2011).

Raith, F., O’Donovan, D. H., Lemos, C., Politz, O. & Haendler, B. Addressing the reciprocal crosstalk between the AR and the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathways for prostate cancer treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24032289 (2023).

Sun, M. et al. Activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway by androgen through interaction of p85alpha, androgen receptor, and Src. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 42992–43000. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M306295200 (2003).

Baron, S. et al. Androgen receptor mediates non-genomic activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-OH kinase in androgen-sensitive epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 14579–14586. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M306143200 (2004).

Wang, Y., Kreisberg, J. I. & Ghosh, P. M. Cross-talk between the androgen receptor and the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway in prostate cancer. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets. 7, 591–604. https://doi.org/10.2174/156800907781662248 (2007).

Yang, L. et al. Induction of androgen receptor expression by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt downstream substrate, FOXO3a, and their roles in apoptosis of LNCaP prostate cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 33558–33565. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M504461200 (2005).

Sarker, D., Reid, A. H., Yap, T. A. & de Bono, J. S. Targeting the PI3K/AKT pathway for the treatment of prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 4799–4805. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0125 (2009).

Lu, Y. et al. Complement signals determine opposite effects of B cells in chemotherapy-induced immunity. Cell. 180, 1081–1097 e1024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.015 (2020).

Devarajan, R. et al. Targeting collagen XVIII improves the efficiency of erbb inhibitors in breast cancer models. J. Clin. Investig. 133 https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI159181 (2023).

Kanda, K. et al. Nardilysin and ADAM proteases promote gastric cancer cell growth by activating intrinsic cytokine signalling via enhanced ectodomain shedding of TNF-alpha. EMBO Mol. Med. 4, 396–411. https://doi.org/10.1002/emmm.201200216 (2012).

Morita, Y. et al. Genome-wide profiling of Nardilysin target genes reveals its role in epigenetic regulation and cell cycle progression. Sci. Rep. 7, 14801. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14942-4 (2017).

Anurag, M. et al. Proteogenomic markers of chemotherapy resistance and response in Triple-Negative breast cancer. Cancer Discov. 12, 2586–2605. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-22-0200 (2022).

Narendra, R. N. et al. Ki-67 levels and their association with response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer: A prospective observational study. Cureus 17, e83207. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.83207 (2025).

Andre, F., Arnedos, M., Goubar, A., Ghouadni, A. & Delaloge, S. Ki67—no evidence for its use in node-positive breast cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 12, 296–301. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.46 (2015).

Mishra, R., Patel, H., Alanazi, S., Kilroy, M. K. & Garrett, J. T. PI3K inhibitors in cancer: clinical implications and adverse effects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22073464 (2021).

Curigliano, G. & Shah, R. R. Safety and tolerability of Phosphatidylinositol-3-Kinase (PI3K) inhibitors in oncology. Drug Saf. 42, 247–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-018-0778-4 (2019).

Sabbah, D. A., Hajjo, R., Bardaweel, S. K. & Zhong, H. A. Targeting the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in anticancer research: a recent update on inhibitor design and clinical trials (2020–2023). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 34, 141–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/13543776.2024.2338100 (2024).

Chen, Y., Zhou, Q., Hankey, W., Fang, X. & Yuan, F. Second generation androgen receptor antagonists and challenges in prostate cancer treatment. Cell. Death Dis. 13, 632. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-022-05084-1 (2022).

Kolyvas, E. A., Caldas, C., Kelly, K. & Ahmad, S. S. Androgen receptor function and targeted therapeutics across breast cancer subtypes. Breast Cancer Res. 24, 79. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-022-01574-4 (2022).

Molina, J. R. et al. An inhibitor of oxidative phosphorylation exploits cancer vulnerability. Nat. Med. 24, 1036–1046. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0052-4 (2018).

Onesto, C., Shutes, A., Picard, V., Schweighoffer, F. & Der, C. J. Characterization of EHT 1864, a novel small molecule inhibitor of Rac family small GTPases. Methods Enzymol. 439, 111–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0076-6879(07)00409-0 (2008).

Abdou, Y. et al. Immunotherapy in triple negative breast cancer: beyond checkpoint inhibitors. NPJ Breast Cancer. 8, 121. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-022-00486-y (2022).

Debien, V. et al. Immunotherapy in breast cancer: an overview of current strategies and perspectives. NPJ Breast Cancer. 9, 7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-023-00508-3 (2023).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000).

Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28, 1947–1951. https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.3715 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank Weixin Wang and the other team members at Cosmos Wisdom Co., Ltd. in Hangzhou, China, for their contributions to the bioinformatic analysis and graph editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z., M.L., S.T., and T.Hu. conceived and supervised the study.M.L. and T.Hu. collected clinical data including patient information and pathology review.W.S. acquired the sequencing data.T.He., F.X., W.S., A.Q., Y.L., and M.L. performed data analysis, integration, and interpretation.Y.Z., S.T., and T.Hu. supervised the bioinformatics analysis.Y.Z., W.S., T.He., F.X., and M.L. wrote the main manuscript text.Y.Z. edited the manuscript.All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

The study was approved by the Peking University Cancer Hospital ethics committee (No. 2020KT113) and all patients provided an informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, Y., Long, M., Shi, W. et al. Proteomics characterization of triple-negative apocrine carcinoma reveals molecular features of progression and chemotherapy response. Sci Rep 15, 39863 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23449-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23449-2