Abstract

Working under extreme heat conditions threatens health and well-being, which is aggravated by climate change. This study estimated the impact of an increase in global temperature on workability in the Brazilian population and its respective economic costs, under two climate change scenarios, projected over the 21st century. Using daytime Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT) projections from Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6) climate models (SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios), we estimated productivity losses in the country’s principal labour activities: agriculture, civil construction, the manufacturing industry, services, and informal labour. The economic cost was obtained from daily wages, number of workers and productivity loss. Our results indicate that the North, Northeast and Central-West regions face significant increases in daytime WBGT, frequently surpassing 34 °C in the SSP5-8.5 scenario, which may exacerbate the effects of outdoor activities as they are currently carried out. In agriculture and civil construction, productivity could fall by 90%. Daily economic losses for regulated labour activities could reach USD 228 million under SSP2-4.5 and up to USD 353 million in SSP5-8.5. To reduce these impacts, global mitigation action to curb the increase of global temperature must be implemented, while national public policies that protect workers, such as creating cool spaces, providing regular breaks, adjusting working hours and encouraging hydration, must be adopted and reinforced.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

We are living in the hottest decade in recorded history. In 2024, the average global near-surface temperature was 1.6 °C higher than the preindustrial average, making it the hottest year in 175 years of meteorological records and, for the first time, the annual average surpassed the 1.5 °C of the Paris Agreement1. Although global mitigation efforts are underway, they remain in early stages, reinforcing the urgency to accelerate actions that address the growing impacts of climate change. The scientific community has warned of the impacts of global warming over 1.5 °C, which include more intense climate change and more frequent extreme weather events2,3.

The 2024 report of The Lancet Countdown warns that accelerated climate change represents unprecedented threats to health and human survival on a global scale. Increased exposure to extreme heat compromises physical activity, sleep and mental health4. In 2023, moderate risk of heat stress during light outdoor exercise increased by 27.7% compared to 1990–1999, hitting record levels4. In Latin America, the rise in temperature has intensified extreme climate risks: between 2013 and 2022, exposure to heatwaves rose by 248% for babies and 271% for the elderly compared to 1986–2005. Over the same period, an increase of 256 and 189 annual hours of environmental heat was recorded; this is associated with moderate to high risk of heat stress5,6.

Heat stress conditions, driven by air temperature, humidity, solar radiation, and wind, influence workability – the capacity to perform labour activities under extreme heat - and productivity loss, which reflects the portion of the working day compromised by heat stress7,8. This decline in physical and cognitive performance during manual activities has already contributed to global productivity losses approaching 10%9. Projections indicate that, under scenarios of high fossil fuel consumption, these losses could escalate to 30–40% by the end of the century9. In 2023, extreme heat resulted in a record loss of 512 billion working hours, equivalent to USD 835 billion in potential income losses4. In Brazil, it is estimated that, by 2100, the economic costs—which corresponds to the financial impact of reduced productivity10, will represent approximately 2% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP)10,11. Workers in high intensity activities and exposed to the open-air environments are more affected, facing losses of income and employment, an increased cost of living, difficulties in adapting and aggravated health problems12,13,14.

The global workforce is composed of approximately 3.3 billion people, 2.4 billion (71% of workers) of whom are exposed to excessive heat15. Of these, workers who undertake external economic activities, such as agriculture, civil construction and extractivism, are more vulnerable to heat stress, due to prolonged exposure to extreme heat and inappropriate working conditions16. Despite progress in understanding the impacts of heat on occupational health, significant gaps remain. In particular, there is a lack of comprehensive studies that explore the impact of climate change on workability and the economic losses associated with specific regional contexts, such as Brazil, a country with high exposure to extreme heat and a strong dependency on outdoor work activities and/or those with limited access to adequate rest areas with milder temperatures.

Our study therefore seeks to fill this gap, providing a detailed analysis of the impacts of global warming on the workability of the Brazilian population and its respective economic costs, under two climate change scenarios, one based on an intermediate development trajectory and another driven by fossil fuels. As a thermal stress indicator, we used the daily Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGTday), which combines air temperature, humidity, solar radiation, and wind speed to estimate the heat load imposed on the human body during outdoor activities. This index is widely adopted in occupational health standards and climate impact assessments because it provides a comprehensive representation of environmental heat stress. In this study, WBGTday was estimated through the end of the century, followed by the calculation of the expected reduction in workability and probable the associated economic costs, providing data to support public policy planning and adaptation strategies.

Materials and methods

Study area

Brazil is the fifth largest country in the world in terms of territory, occupying approximately 8,510,417.771 km², and the seventh in terms of its population, which is over 203 million. Approximately 84.72% of this population lives in urban areas, with 12.4% in rural areas17. The country is divided into 5570 municipalities, 26 administrative units and one federal district, and is composed of five large regions (Fig. 1). The heterogeneous topography of its territory, with its mountains, plateaus and plains, has a strong influence on wind circulation and climate systems, contributing to the formation of varied climate zones and meteorological conditions18.

Topographic map of Brazil showing regional boundaries. Data derived from HydroSHEDS (https://www.hydrosheds.org/hydrosheds-core-downloads).

Brazil’s five macro-regions exhibit diverse climatic characteristics, encompassing three major Köppen climate zones - tropical (A), dry (B), and subtropical (C) - are present, which are further subdivided into nine distinct climate types across the country. The North region is predominantly classified as tropical rainforest (Af) and monsoon (Am), with high annual rainfall and little temperature variation, especially in the Amazon Basin. The Northeast presents sharp climatic contrasts, ranging from tropical savanna (Aw) and monsoon (Am) along the coast to semi-arid (BSh) conditions in the interior, making it one of the driest areas in the country. In the Central-West, the dominant climate is tropical savanna (Aw), characterised by a pronounced dry winter and wet summer, although monsoon (Am) conditions also occur in the northwest. The Southeast includes a mix of tropical (Aw, Am) and subtropical (Cwa, Cwb, Cfa, Cfb) climates, influenced by variations in elevation and its transitional position between climatic zones. Finally, the South is characterised by subtropical humid climates (Cfa and Cfb), with more defined seasons and cooler temperatures, particularly in the highlands19,20,21.

Projected data in the climate change scenarios

Meteorological data

Historical and simulated data from the SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) were used, based on 18 climate models (Table 1) obtained from the NASA Earth Exchange Global Daily Downscaled Projections (NEX-GDDP-CMIP6) dataset22. These models were selected for their strong performance in recent studies for Brazil23,24,25. The SSPs were produced by the sixth phase of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6) and represent potential socio-economic trajectories over the 21 st century, each associated with different levels of greenhouse gas emissions (GGEs) and changes to land use, with the SSP2-4.5 representing an intermediary development scenario and the SSP5-8.5 a fossil-fuel dependent one26. The NEX-GDDP-CMIP6 data has a daily temporal and spatial resolution of 0.25° × 0.25° with built-in bias correction. This ensures that the data is suitable for regional- and local-level studies, capturing the spatial-temporal patterns of the climate variables, enabling us to assess the future impacts of climate change associated with the two scenarios22.

The NEX-GDDP-CMIP6 dataset provides bias-corrected and downscaled climate projections that incorporate meteorological station observations during the calibration process. The reliability of this dataset for regional climate impact assessments in Brazil has been demonstrated in previous validation studies27,28.

Meteorological variables used in this study included relative humidity (RH, %), short-wave radiation (R, W/m²), average (Ta, °C) and maximum (Tmax, °C) near-surface air temperature, and wind speed at 10 m (V, m/s), extracted from the NEX-GDDP-CMIP6 dataset. These variables were selected to calculate the daytime Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGTday), a composite index that integrates multiple environmental stressors to assess occupational heat stress more accurately than temperature alone. The use of WBGTday allows for a more realistic evaluation of heat exposure during typical working hours, particularly in outdoor environments.

For each variable, an ensemble mean was calculated from the 18 climate models for both the historical baseline (1981–2014) and future projections (2025–2099), which were divided into three time intervals: short-term (2025–2049), medium-term (2050–2074), and long-term (2075 to 2099).

Wind speed data simulated at 10 m were adjusted to 2 m following the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)29 guidelines for short grass surfaces, as required for accurate WBGT calculation:

\(\:{U}_{2}=\) wind speed 2 m above ground surface (m/s); \(\:{U}_{z}=\) measured wind speed z m above ground surface (m/s); \(\:z=\) height of measurement above ground surface (m).

Calculation of the wet bulb globe temperature (WBGT)

The WBGT is widely used in occupational30 and sports health31. It combines certain meteorological variables in order to simulate the environmental conditions32 during intense physical activity8,33.

The WBGT index combines three key environmental variables: natural wet bulb temperature (Tnwb), which reflects the effects of humidity, wind speed, and air temperature on evaporative cooling; globe temperature (Tg), which accounts for radiant heat from solar exposure; and air temperature (Ta), representing the ambient dry bulb temperature. Together, these variables simulate the external environmental heat load and are used to estimate WBGT values under different climate conditions.

The meteorological data (Table 1) obtained from the simulations was used to calculate the external WBGT under the SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios. The external WBGT is calculated as the weighted average of the Tnwb, Tg and Ta, according to the following equation:

We applied empirically derived equations based on previous studies to obtain the estimates for Tnwb and Tg. The equation used to calculate the globe temperature (Tg)34 was based on air temperature (Ta) and incident solar radiation (R) data, resulting in the following formula:

This method was validated by its authors, using three years of field data from the Brazilian Northeast and showed high accuracy under daytime outdoor conditions (R² = 0.91). Although the equation does not include wind speed, it performs well in tropical environments and suits large-scale applications. This simplification may cause small deviations, but its impact on WBGT is limited due to the lower weight of Tg in the final index.

The natural wet-bulb temperature (Tnwb) is the appropriate input for WBGT calculations, but its direct estimation is limited by data availability in local-scale climate projections. To address this, Tnwb was approximated using the psychrometric wet-bulb temperature (Tpwb)35,36, based on previously established equations. According to these equations, if \(\:{T}_{g}-{T}_{a}<4\):

where C is a constant that depends on wind speed V (m/s) and

when \(\:{T}_{g}-{T}_{a}\ge\:4\), we incorporate the effect of radiant heat, as described below:

where e is given by:

The Tpwb equation is described as:

To obtain the vapour pressure, a previously developed equation was applied35:

Although Tnwb and Tpwb differ in their physical basis, the Tpwb based method applied in this study produces WBGT estimates with acceptable accuracy for large-scale climate analyses36. Linear regressions show strong agreement between calculated and observed Tnwb values (R² ≥ 0.95)36. The authors who developed and applied this equation to estimate WBGT reported biases ranging from − 0.44 to 0.11, depending on the location, indicating minimal deviation and acceptable accuracy for regional-scale applications.

No interpolation method was applied in the spatial representation of the WBGT. Instead, calculations were performed directly at each grid point of the NEX-GDDP-CMIP6 dataset, preserving the original spatial resolution of 0.25° × 0.25°. This procedure ensured that the WBGT values reflected the localized climatic conditions simulated by each model, maintaining consistency with the bias-corrected and downscaled data used throughout the analysis.

Population data

The exposed population in Brazil under both socio-economic development scenarios was calculated using the ISIMIP2b protocol from the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project (ISIMIP), which provides population density data (per km²) a 1/24 spatial resolution37. The population affected by the heat conditions that impact on workability was estimated for the 2075 to 2099 period.

The SSP2-4.5 projections suggest a reduction in Brazil’s population density across almost the entire nation, with the most significant drop (low fertility) in the coastal states between Pará and Rio Grande do Sul38. Moderate growth with balanced urbanization and spatial development is observed in large metropolitan regions, which represent exceptions to the general trend. The SSP5-8.5 scenario suggests that, even with economic optimism and greater investment in education and health, Brazil will maintain a population density similar to that of the SSP2-4.5 with accelerated urbanization in its metropolitan regions38.

The quarterly average of the 2022 working population, available from the System of Automatic Recovery (Sistema IBGE de Recuperação Automática: SIDRA) of the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística: IBGE’s) (SIDRA/IBGE) (https://sidra.ibge.gov.br/tabela/5434 and https://sidra.ibge.gov.br/tabela/8517), was used as a reference for the number of workers in each sector. Based on this information, the proportion of the population employed by each sector within each region was calculated. In 2022, Brazil had an approximate total of 99 million active workers, of which 39% (38.8 million) were working informally, according to the SIDRA/IBGE data. This level of informal labour is particularly high in the North and Northeast regions, reflecting greater worker vulnerability in these areas. Approximately 8.7% of the national workforce is employed in agriculture, 7.42% in civil construction and 12.7% in industry. The service sector accounts for the highest proportion, at 50.7%. However, sectoral distribution varies significantly between regions: agriculture continues to represent an important source of employment in the Northeast, while the services and industry dominate in the Southeast.

To estimate the future proportion of active workers, the 2022 sectoral workforce in each Brazilian region was divided by the total regional population from the 2022 census17. This proportion was then multiplied by the projected population under each development scenario. This allowed us to estimate the number of workers employed in each sector and region in Brazil in the final quarter of the century (2075 to 2099), taking account of the same sector/economic activity distribution. Although this assumption does not capture potential structural labour market shifts, such as those driven by automation or public policies, it enables the isolation of climate change effects on current labour structures, ensuring comparability across scenarios. These estimates were then used to estimate the potential economic costs that each may incur under the two climate change scenarios.

Labour loss estimates

An established method39 to calculate daily WBGT (WBGTday) and thus estimate workability and productivity losses under the climate change scenarios for Brazil’s five regions was applied. In this method, the WBGTday follows the “4 + 4 + 4” formula, which represents the 12 h of daylight, where the sets of 4 h correspond to the daily average (WBGTtas), the maximum daily value (WBGTtasmax) and the average between the two (WBGThalf):

The applicability of this method to daily data was verified40, demonstrating that the difference between this and hourly data was less than 5%. The methodology assumes a 12-hour workday (6 a.m. to 6 p.m.) to represent the total period of potential daytime exposure to heat. Although the typical Brazilian workday usually spans from 7 a.m. to 5 p.m., this simplification follows the standard adopted in previous studies40 to reflect average daylight availability. As a result, the estimated labour losses may be slightly overestimated; however, this approach ensures consistency with the WBGTday calculation and allows for comparative analyses under different climate scenarios:

The error function (erf) is used to report the decline in labour productivity due to heat exposure, accounting for different levels of work intensity. WBGTaver and WBGTstd are fixed reference parameters for workers engaged in varying activity levels41, as shown in Table 2. This function generates values in the range of −1 to 1. To normalize these values in the [0, 1] range, add 1 to the result and divide by 2. To convert the Loss Fraction result into a percentage, multiply the value by 100.

The variables WBGTaver and WBGTstd correspond to the average WBGT and its standard deviation, respectively, for each level of work intensity (light, moderate, and high). These values are not exposure limits per se, but parameters used in the exposure–response function (ERF) to estimate productivity losses. WBGTaver represents the threshold around which productivity losses begin to occur, while WBGTstd accounts for the variability in tolerance to heat stress, enabling a probabilistic estimation of impacts across the working population40,41.

The Loss Fraction was calculated for labour activities that employ the largest share of the Brazilian workforce: agriculture, civil construction, manufacturing, services, and informal labour across all sectors. To classify the intensity level of each activity, this study adopted thresholds for light (≈ 200 W), moderate (≈ 300 W), and high (≈ 400 W) work based on international standards ISO 7243 (2017) and ACGIH (2015)42. These metabolic rates reflect typical activity types: light work includes seated or administrative tasks; moderate work includes standing or machine-based tasks; and high work refers to physically demanding tasks such as construction or manual field labour. Based on this classification, manufacturing and services were categorized as moderate intensity, while agriculture, civil construction, and informal labour were classified as high intensity. These classifications supported the estimation of productivity losses presented in Table 3.

Results

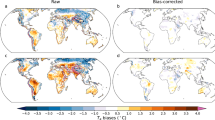

The WBGTday projections to assess daytime workability indicate a progressive increase in heat stress over the coming decades, particularly under the SSP5-8.5 high emission scenario (Fig. 2) compared to the historical period (1981–2014) (Figure S1). Thermal sensation of extreme heat stress is more intense in the North, Central-West and Northeast regions under both scenarios.

Daytime WBGT projections (WBGTday) under the SSP2-4.5 (top) and SSP5-8.5 (bottom) scenarios over the short (2025–2049), medium (2050–2074) and long term (2075–2099). Maps were generated using Python 3.11.3 (https://www.python.org/) with the libraries NumPy 2.1.2, Xarray 2024.10.0, Matplotlib 3.9.2, Cartopy 0.24.1, and Colorcet 3.1.0.

Light-intensity activities were not considered in this analysis, as they are generally associated with indoor, air-conditioned environments and therefore less exposed to outdoor heat stress conditions. Productivity loss in moderate activities, such as the manufacturing industry and services, is presented in percentage terms in Fig. 3. We identified losses ranging from 0 to 65%, 81% and 93% in the short, medium and long term, respectively. The Southern region, which includes areas with subtropical climates, appears to be the least affected by productivity losses arising from heat stress. In contrast, the scenarios project the greatest losses in Brazil’s Northern region, characterized by an equatorial climate, with values exceeding 90% under the SSP5-8.5 scenario during the final quarter of the century.

Loss of productivity in moderate intensity activities under the SSP2-4.5 (top) and SSP5-8.5 (bottom) scenarios over the short (2025–2049), medium (2050–2074) and long term (2075–2099). Maps were generated using Python 3.11.3 (https://www.python.org/) with the libraries NumPy 2.1.2, Xarray 2024.10.0, Scipy 1.14.1, Matplotlib 3.9.2, Cartopy 0.24.1, and Colorcet 3.1.0.

Figure 4 shows the areas experiencing the greatest productivity loss in high intensity activities, such as agriculture and civil construction, as well as for informal workers in Brazil. These losses can reach up to 73%, 86% and 95% over the short, medium and long term. A significant increase in productivity loss is observed compared to moderate intensity activities, with values exceeding 50% between 2050 and 2074 in areas semi-arid and tropical savanna climates, particularly in parts of the Northeast and Central-West regions, where such losses had not been previously recorded (Fig. 3). Without substantial adaptation of work environments, heat stress is expected to further intensify the impacts on outdoor labor by the end of the century.

Loss of productivity in high intensity activities under the SSP2-4.5 (top) and SSP5-8.5 (bottom) scenarios over the short (2025–2049), medium (2050–2074) and long term (2075–2099). Maps were generated using Python 3.11.3 (https://www.python.org/) with the libraries NumPy 2.1.2, Xarray 2024.10.0, Scipy 1.14.1, Matplotlib 3.9.2, Cartopy 0.24.1, and Colorcet 3.1.0.

Figure 5 demonstrates the daily economic costs (in USD million), for each of Brazil’s regions by the end of the century (2075–2099), associated with productivity losses in each of the work activities (agriculture, construction, industry and services) and in informal work, according to estimates under the SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios. Since data for informal work also include activities that are not part of this analysis, we chose to present them separately (bottom row), thereby avoiding duplication or overestimation of the total economic cost.

When we compared the two scenarios, we noted that the economic losses in the moderate emission scenario (SSP2-4.5) were lower than those in the high emission one (SSP5-8.5). Total daily losses could reach USD 228 million in the first scenario and USD 353 million in the second, while those in the informal sector are USD 116 million and USD 160 million respectively. In both scenarios, the highest economic costs are found in the service sector, due to the high number of active workers in it. This is followed by the informal sector, which includes workers without formal employment contracts working in all of Brazil’s economic sectors. This is followed by industry, civil construction and agriculture.

In our regional analysis, the Southern region records the lowest total economic costs: USD 11.6 million in scenario SSP2-4.5 and USD 21.8 million in scenario SSP5-8.5. For the informal sector, these costs are USD 4.6 million and USD 7.9 million, respectively. The Central-West has costs of USD 29.2 million and USD 40.4 million, with USD 11.6 million and USD 14.8 million in the informal sector. In the Northern region, these costs represent USD 36.4 million and USD 45.9 million, while the informal sector experiences losses of USD 22.2 million and USD 25.8 million. Costs in the Northeast are USD 66 million and USD 94.6 million, with the informal sector at USD 41.9 million and USD 55 million. Finally, the Southeast ranks first in terms of economic costs, reaching USD 84.6 million and USD 150.8 million for the principal work activities, and USD 35.5 million and USD 56.4 million in the informal sector. Additional details about economic losses by state can be found in the Supplementary Material (see Supplementary Fig. S2 and S3 online).

Discussion

Regional disparities and projected impacts

Our results suggest that, by the end of the century, the North, Central-West and Northeast regions will be the most impacted, with productivity losses of over 90% in physically intense labour activities, such as agriculture and civil construction, particularly under the SSP5-8.5 scenario. The greatest economic costs were associated with the service sector and informal labour, with an emphasis on the Southeast, which will experience the greatest impact, due to its population density and intense economic activities, while the South will experience the least, reflecting its milder climate conditions.

In both scenarios, we observed a consistent increase in WBGTday over all the periods, with the SSP5-8.5 scenario presenting the most significant and comprehensive increases over the long term. A WBGTday of 34 °C is considered the critical limit for occupational safety8, suggesting that, in the high emission scenarios, outdoors activities, as they are currently performed, will be compromised in the Northern region and in parts of the Central-West and Northeast during a significant part of the year. In the SSP2-4.5 scenario, the minimum and maximum WBGTday values increased by 1.88 °C and 3.87 °C respectively, while in the SSP5-8.5 scenario, these increases were even more significant, reaching a minimum of 3.52 °C and a maximum of 7.70 °C. These results are in line with the recent work43, who reported an increased WBGT of 4 °C and 7 °C for Brazil under similar scenarios. The projected impact for Brazil reflects the global trends of increased WBGT observed in tropical regions, such as Sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, Oceania, Central America, the Caribbean and South America, where it frequently exceeds the safety limits for outdoor labour44,45,46.

Occupational risks and socioeconomic inequality

An increase in extreme temperatures could expose a significant portion of the working class to unhealthy conditions, particularly in regions more susceptible to intense heat events, such as the North and Northeast47,48. In these areas, lower levels of schooling49 and high levels of informal labour, activities that demand physical effort, such as agriculture and extractivism, increase worker exposure to heat stress. The growing trend of such exposure to extreme temperatures has serious implications for public health and labour productivity50,51,52. In the Central-West, despite advances in agricultural mechanization, small-scale farmers continue to experience difficulties due to extreme climate conditions and a lack of subsidies. In the South and Southeast, sectors such as civil construction and agriculture also experience the severe impacts of intense heat, particularly among the low income population16,53,54.

An absence of adequate infrastructure to mitigate the effects of extreme heat raises the incidence of heat exhaustion, sunstroke and other heat-related conditions55, forcing workers to reduce their active working hours. In order to minimize such impacts, rest breaks must be provided, preferably in shaded areas where seating is provided8,39, while hydration must be maintained. Adjusting work schedules to cooler periods of the day or considering night shifts may also help reduce heat exposure and protect worker health. However, given the projected increases in extreme temperature, these measures may not be sufficient to eliminate the risks associated with heat stress. It is therefore crucial to invest in work environment technologies, such as substituting physically demanding activities for lighter tasks, whenever possible, as well as adopting personal protective equipment (PPEs) designed to cool the body. Such initiatives can help to reduce the impacts of heat stress, which both compromises working conditions and represents a significant risk to health56, not only affecting high intensity activities but also moderate or low intensity tasks, impacting activities such as transport and trade.

Formal workers who undertake outdoor activities, such as postmen and women, drivers, garbage collectors and members of the public security forces, have some level of collective and individual protection, such as appropriate uniforms, planned breaks and access to drinking water. Informal workers, on the other hand, such as temporary agricultural workers, street vendors, delivery drivers and recycled-waste collectors, face even more precarious conditions. Without access to worker benefits or adequate protection measures, such workers are much more susceptible to extreme heat57, accentuating the social and economic inequalities arising from climate change. Further, since they depend directly on their daily production efforts to guarantee their living, they very often ignore the natural warning signs of their bodies in response to excessive heat, intensifying physical efforts and exposing themselves to even greater risks.

Economic implications under different climate change scenarios

The economic losses associated with heat stress varied significantly between the scenarios. The daily economic losses in scenario SSP2-4.5 were USD 228 million, while in the SSP5-8.5 one they reached USD 353 million, representing an increase of almost 55%. These numbers highlight how political decisions and the population’s habits can substantially reduce future economic impacts. From this viewpoint, the implementation of mitigation measures, such as the reduction of GGEs and investment in adapted infrastructure, could limit the financial losses and protect the most sensitive sectors, particularly in a country such as Brazil, which has such marked regional differences.

Regional analyses reveal important inequalities. The greatest economic losses occurred in the Southeast and Northeast regions, reflecting their population density, climate vulnerability and occupational characteristics. Informal work, with losses of up to USD 160 million in SSP5-8.5, highlight the vulnerability of workers with no formal protections. On the other hand, the South experiences the lowest costs, indicating more favorable economic and climate features. These results support the assertion that immediate decisions could lead to fairer social and economic trajectories58. The SSP2-4.5 scenario demonstrates that efforts to reduce emissions, such as the Paris Agreement, are economically viable and effective. In contrast, the SSP5-8.5 scenario exposes the high costs of inaction, particularly for those sectors most dependent on the human workforce, such as agriculture, construction and other forms of informal labour.

We observed that climate change could represent an imminent crisis for Brazil’s production capacity, with serious long-term social and economic repercussions. The relationship between heat discomfort and economic losses is increasingly evident4 and requires immediate action from decision-makers. In the Amazon, sustainable economic activities, preserving the forest and developing agroforestry systems, are viable alternatives, with the potential to generate seven times more profit than exploration activities and to mitigate climate impacts59. Formalizing work, investing in resilient infrastructure and low carbon policies are examples of the action required for a more sustainable and equitable future.

Study limitations

We should consider some of the study’s limitations. First, the database does not encompass the ethnic and age diversity of the Brazilian population, due to a lack of detailed information in the climate scenarios’ population projections. As a result, our analysis does not reflect variations in heat vulnerability associated with these factors known to exacerbate the effects of heat exposure. This limitation likely leads to an underestimation of productivity and economic losses, particularly among marginalised or underserved groups, as population averages may conceal disproportionately higher impacts experienced by those more vulnerable to heat stress.

Second, the classification of labour activities into moderate and high intensity follows official guidelines but does not capture intra-sectoral variability, such as distinctions between mechanised and manual tasks or between administrative and physical roles. The data on informal labour also aggregates activities beyond those analysed in detail, which may lead to further approximation. Moreover, the analysis assumes a static labour distribution based on 2022 census data. While this enables comparability across climate scenarios, it does not reflect potential shifts in employment structure driven by automation, economic development, or public policy, due to the absence of integrated projections for Brazil. Additionally, when calculating economic costs, we assumed that all active workers perform their tasks in environments without access to cooling infrastructure, which may not accurately reflect conditions in certain regions or sectors. Our model also does not account for potential future adaptations, such as adjustments to working hours, the implementation of protective technologies, or behavioural changes, that could reduce heat exposure and mitigate productivity losses over time.

Third, applying uniform heat stress thresholds across a climatically diverse country like Brazil adds uncertainty to our estimates. Although 92% of the territory lies within the intertropical zone, the remaining 8% falls south of the Tropic of Capricorn, where populations may be less physiologically adapted to high heat exposure. As a result, using a single threshold may underestimate heat-related productivity losses in these regions. Nonetheless, we adopted this approach to ensure comparability across regions and climate scenarios, following widely accepted international guidelines40,42. Moreover, the lack of region-specific WBGT thresholds derived from physiological data for most parts of Brazil hindered the application of more locally sensitive values.

Finally, although WBGT is widely recognised for bioclimatic evaluations, its application in population studies presents significant challenges, including the lack of a database and the limited availability of specialised operational equipment60. Although we did not conduct a specific validation of the WBGT estimates for this study, previous research has validated the performance of the CMIP6 models for Brazil23,24,25 and applied established methodologies based on simulated meteorological variables10,34,35,36,39,40,42,43. However, CMIP6 models have known uncertainties in spatial resolution and bias correction22,61,62,63, which may affect the accuracy of WBGT estimates. Moreover, the empirical equations used to estimate WBGT components simplify complex heat exchange processes and introduce errors; validation studies report strong correlations but also biases that vary by location34,36,39,40,41.

Despite these limitations, this approach provides reliable insights for large-scale assessments and is particularly useful for comparing impacts across intermediate and high-emission scenarios. Nonetheless, caution is warranted when interpreting results at finer regional or demographic levels. Future studies could build upon the current work by incorporating more detailed socioeconomic and demographic information, such as age, ethnicity, income, and education levels, to better capture heterogeneity in heat vulnerability and labour capacity, provided that projections with this level of detail become available. Integrating projections of employment structure, informal labour distribution, and regional adaptation measures would allow for more precise estimates of productivity losses under climate change scenarios. Further research could also examine sector-specific responses, behavioral adaptations, and the effectiveness of protective interventions, providing more nuanced insights to guide public policy and public health strategies aimed at mitigating heat-related economic and health impacts.

Strengths and implications

This study offers an interdisciplinary contribution by integrating climate, labour and economic analyses, highlighting regional variations and the urgent need for public policies to protect workers and reduce the economic impacts associated with heat stress. By quantifying the potential economic impacts associated with productivity, taking account of both the percentage of lost hours due to the need for worker rest and hydration, and the associated economic cost, our results provide valuable insights into the potential economic consequences of climate conditions according to developmental trajectories and climate scenarios.

The ongoing monitoring of heat exposure is crucial for protecting the population’s health throughout the year64. Despite the existence of Brazilian legislation to protect workers against extreme heat, there remains a need to improve monitoring systems, promote more efficient interventions and implement innovative public policies65. It is therefore essential to connect public policies with private initiatives in order to adopt measures for worker protection, such as creating cool spaces, guaranteeing regular breaks, adjusting worker hours and encouraging adequate hydration. Such initiatives are essential to strengthening adaptation and resilience to extreme heat, ensuring the health and safety of the workforce in an increasingly intense climate change scenario.

Conclusion

We estimated the impacts of climate change on workability and on the economic costs to the Brazilian population up to the end of the 21 st century. Our results suggest that the North, Central-West and Northeast will face extreme heat conditions (WBGTday > 34 °C) for most of the year, particularly under the SSP5-8.5 scenario, compromising outdoor activities. In contrast, the South and Southeast regions will experience more moderate impacts, with some areas avoiding extreme heat conditions.

Work activities related to services will experience the highest economic costs, followed by informal labour, agriculture and civil construction. The Southeast and Northeast regions will experience the highest total costs, while, despite high productivity losses. In the most pessimistic scenario, productivity losses in high intensity activities could exacerbate the effects of outdoor activities in several parts of the North and Northeast.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data are freely available and can be accessed at: NEX-GDDP (https://nex-gddp-cmip6.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/index.html), ISIMIP2b (https://data.isimip.org/search/tree/ISIMIP2b/SecondaryInputData/socioeconomic/pop/), IBGE (https://sidra.ibge.gov.br/tabela/5434 & https://sidra.ibge.gov.br/tabela/8517).

References

Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S). Global climate highlights 2024. (2025).

Calvin, K. et al. IPCC, 2023: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (Eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/ (2023). https://doi.org/10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647

United Nations Environment Programme. Emissions Gap Report 2023: Broken Record – Temperatures Hit New Highs, yet World Fails To Cut Emissions (Again) (United Nations Environment Programme, 2023). https://doi.org/10.59117/20.500.11822/43922

Romanello, M. et al. The 2024 report of the lancet countdown on health and climate change: facing record-breaking threats from delayed action. Lancet 404, 1847–1896 (2024).

Suresh, K. Extremes of weather conditions and child health. Open. J. Pediatr. Child. Health. 9, 050–057 (2024).

World Health Organization (WHO). Heat and health. (2024). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-heat-and-health

Dasgupta, S. et al. Effects of climate change on combined labour productivity and supply: an empirical, multi-model study. Lancet Planet. Health. 5, e455–e465 (2021).

Andrews, O., Le Quéré, C., Kjellstrom, T., Lemke, B. & Haines, A. Implications for workability and survivability in populations exposed to extreme heat under climate change: a modelling study. Lancet Planet. Health. 2, e540–e547 (2018).

De Sario, M. et al. Occupational heat stress, heat-related effects and the related social and economic loss: a scoping literature review. Front. Public. Health. 11, 1173553 (2023).

Zhao, M. et al. Labour productivity and economic impacts of carbon mitigation: a modelling study and benefit–cost analysis. Lancet Planet. Health. 6, e941–e948 (2022).

Souza, B. & Haddad, E. Climate change in brazil: dealing with uncertainty in agricultural productivity models and the implications for economy-wide impacts. Spat. Econ. Anal. 17, 83–100 (2022).

Karthick, S., Kermanshachi, S., Pamidimukkala, A. & Namian, M. A review of construction workforce health challenges and strategies in extreme weather conditions. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 29, 773–784 (2023).

Abbass, K. et al. A review of the global climate change impacts, adaptation, and sustainable mitigation measures. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 29, 42539–42559 (2022).

El Khayat, M. et al. Impacts of climate change and heat stress on farmworkers’ health: A scoping review. Front. Public. Health. 10, 782811 (2022).

ILO. Ensuring safety and health at work in a changing climate | International Labour Organization. (2024). https://www.ilo.org/publications/ensuring-safety-and-health-work-changing-climate

Flouris, A. Heat at Work: Implications for Safety and Health: A Global Review of the Science, Policy and Practice | VOCEDplus, the International Tertiary Education and Research Database. (2024).

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia Física (IBGE). : População e Demografia, Primeiros Resultados. IBGE | Biblioteca Censo Demográfico (2022). https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/index.php/biblioteca-catalogo?view=detalhes&id=2102011 (2023).

Cavalcanti, I. F. A. Tempo e clima no Brasil (Oficina de Textos, 2016).

Alvares, C. A., Stape, J. L., Sentelhas, P. C., De Moraes Gonçalves, J. L. & Sparovek, G. Köppen’s climate classification map for Brazil. Meteorol. Z. 22, 711–728 (2013).

Zonas Climáticas do Brasil, conforme Köppen. Centro de Estudos da Metropole (2021). https://doi.org/10.55881/cem.db.clk001

Lima, R. F. D., Aparecido, L. E. D. O., Torsoni, G. B. & Rolim, G. D. S. Climate change assessment in Brazil: Utilizing the Köppen-Geiger (1936) Climate Classification. Rev Bras. Meteorol 38, 18 (2023).

Thrasher, B. et al. NASA global daily downscaled Projections, CMIP6. Sci. Data. 9, 262 (2022).

Reboita, M. S., De Souza Ferreira, W., Gabriel Martins Ribeiro, G., Ali, S. & J. & Assessment of precipitation and near-surface temperature simulation by CMIP6 models in South America. Environ. Res. Clim. 3, 025011 (2024).

Firpo, M. Â. F. et al. Assessment of CMIP6 models’ performance in simulating present-day climate in Brazil. Front. Clim. 4, 948499 (2022).

Brumatti, L. M., Commar, L. F. S., Neumann, N. D. O., Pires, G. F. & Avila-Diaz, A. Bias correction in CMIP6 models simulations and projections for brazil’s climate assessment. Earth Syst. Environ. 8, 121–134 (2024).

Dantas, L. G., Santos, D., Santos, C. A. C., Martins, C. A. G., Alves, L. M. & E. S. P. R. & Future changes in temperature and precipitation over Northeastern Brazil by CMIP6 model. Water 14, 4118 (2022).

Mendonça, L. M., Blanco, C. J. C. & Cruz, J. Performance and projections of the NEX-GDDP-CMIP6 in simulating precipitation in the Brazilian Amazon and Cerrado biomes. Int. J. Climatol. 44, 3726–3741 (2024).

Avila-Diaz, A., Abrahão, G., Justino, F., Torres, R. & Wilson, A. Extreme climate indices in brazil: evaluation of downscaled Earth system models at high horizontal resolution. 54, 5065–5088 (2020).

Allen, R. G., Pereira, L. S., Raes, D. & Smith, M. F. A. O. Irrigation and drainage paper 56. Crop evapotranspiration (guidelines for computing crop water requirements). Food Agric. Organ. U N Rome 300, (1998).

Lemke, B. & Kjellstrom, T. Calculating workplace WBGT from meteorological data: A tool for climate change assessment. Ind. Health. 50, 267–278 (2012).

Yeargin, S. et al. Variations of wet-bulb Globe temperature across high school athletics in South Carolina. Int. J. Biometeorol. 67, 735–744 (2023).

Yaglou, C. P. & Minard, D. Control of heat casualties at military training centers. AMA Arch. Ind. Health. 16, 302–316 (1957).

Parsons, K. Human Thermal Environments (CRC, 2007). https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420025248.

Da Silva, T. G. F. et al. Black Globe temperature from meteorological data and a bioclimatic analysis of the Brazilian Northeast for Saanen goats. J. Therm. Biol. 85, 102408 (2019).

Bernard, T. E. Prediction of workplace wet bulb global temperature. Appl. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 14, 126–134 (1999).

Carter, A. W., Zaitchik, B. F., Gohlke, J. M., Wang, S. & Richardson, M. B. Methods for estimating wet bulb globe temperature from remote and low-cost data: A comparative study in Central Alabama. GeoHealth 4, e2019 (2019).

Frieler, K. et al. Assessing the impacts of 1.5°C global warming – simulation protocol of the Inter-Sectoral impact model intercomparison project (ISIMIP2b). Geosci. Model. Dev. 10, 4321–4345 (2017).

Jones, B. & O’Neill, B. C. Spatially explicit global population scenarios consistent with the shared socioeconomic pathways. Environ. Res. Lett. 11, 084003 (2016).

Kjellstrom, T., Freyberg, C., Lemke, B., Otto, M. & Briggs, D. Estimating population heat exposure and impacts on working people in conjunction with climate change. Int. J. Biometeorol. 62, 291–306 (2018).

Parsons, L. A., Shindell, D., Tigchelaar, M., Zhang, Y. & Spector, J. T. Increased labor losses and decreased adaptation potential in a warmer world. Nat. Commun. 12, 7286 (2021).

Cai, W. et al. The 2022 China report of the lancet countdown on health and climate change: leveraging climate actions for healthy ageing. Lancet Public. Health. 7, e1073–e1090 (2022).

Morabito, M. et al. Heat-related productivity loss: benefits derived by working in the shade or work-time shifting. Int. J. Prod. Perform. Manag. 70, 507–525 (2020).

Bitencourt, D. P., Alves, M. & Shibuya, L. Climate change impacts on heat stress in Brazil—Past, present, and future implications for occupational heat exposure. Int. J. Climatol. 41, 52 (2021).

Newth, D. & Gunasekera, D. Projected changes in Wet-Bulb Globe temperature under alternative climate scenarios. Atmosphere 9, 187 (2018).

Kitsios, V., O’Kane, T. J. & Newth, D. A machine learning approach to rapidly project climate responses under a multitude of net-zero emission pathways. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 355 (2023).

Buzan, J. R. Implementation and evaluation of wet bulb globe temperature within non-urban environments in the community land model version 5. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 16, e2023 (2024).

Marengo, J. A. et al. Drought in Northeast brazil: A review of agricultural and policy adaptation options for food security. Clim. Resil. Sustain. 1, e17 (2022).

Marengo, J. A. et al. The drought of Amazonia in 2023–2024. Am. J. Clim. Change. 13, 567–597 (2024).

Educação 2022. IBGE, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, (2023).

De Alves, B. F., Bottino, M. J., Nobre, P. & Nobre, C. A. Deforestation and climate change are projected to increase heat stress risk in the Brazilian Amazon. Commun. Earth Environ. 2, 207 (2021).

Libonati, R. et al. Drought–heatwave nexus in Brazil and related impacts on health and fires: A comprehensive review. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 1517, 44–62 (2022).

Helo Sarmiento, J., Melo, O., Ortiz-Alvarado, L. & Pantoja Vallejos, C. Reyes-Mandujano, I. F. Economic impacts associated with the health effects of climate change in South america: a scoping review. Lancet Reg. Health - Am. 26, 100606 (2023).

Bitencourt, D. P. Maximum wet-bulb Globe temperature mapping in central–south brazil: a numerical study. Meteorol. Appl. 26, 385–395 (2019).

Schneider, S., Cazella, A. A., Mattei, L. F. & Histórico caracterização e dinâmica recente do PRONAF – programa Nacional de Fortalecimento Da agricultura familiar. Rev. Grifos. 30, 12–41 (2020).

Hamed, M. M. et al. Thermal bioclimatic indicators over Southeast asia: present status and future projection using CMIP6. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 29, 91212–91231 (2022).

Schwingshackl, C., Sillmann, J., Vicedo-Cabrera, A. M., Sandstad, M. & Aunan, K. Heat stress indicators in CMIP6: estimating future trends and exceedances of Impact‐Relevant thresholds. Earths Future. 9, e2020EF001885 (2021).

Fernandes, R. D. C. P. O Construto multidimensional Trabalho precário, o futuro do Trabalho e a saúde de trabalhadoras(es). Cad Saúde Pública. 39, e00100522 (2023).

Haasnoot, M., Di Fant, V., Kwakkel, J. & Lawrence, J. Lessons from a decade of adaptive pathways studies for climate adaptation. Glob Environ. Change. 88, 102907 (2024).

A Balancing Act for Brazil’s Amazonian States: an Economic Memorandum. (The World Bank, (2023). https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1909-4

Spangler, K. R., Liang, S. & Wellenius, G. A. Wet-Bulb Globe Temperature, universal thermal climate Index, and other heat metrics for US Counties, 2000–2020. Sci. Data. 9, 326 (2022).

Baogang, Y. et al. Future changes in extremes across China based on NEX-GDDP-CMIP6 models. Clim. Dyn. 62, 9587–9617 (2024).

Talchabhadel, R., Bhattarai, S. & Bista, S. Projected changes in precipitation extremes across the Mississippi river basin using the NASA global daily downscaled datasets NEX - GDDP ‐ CMIP6. Int. J. Climatol. 45, e8748 (2025).

Moradian, S., Coleman, L., Kazmierczak, B. & Olbert, A. I. How to choose the most proper representative climate model over A study region? A case study of precipitation simulations in Ireland with NEX-GDDP-CMIP6 data. Water Resour. Manag. 38, 215–234 (2024).

Amorim, A., Labaki, L., Maia, P., Barros, T. & Marcelo, A. Occupational exposure to heat in outdoor activities in Building constructions in southeastern Brazil. In Advances in Safety Management and Human Factors Vol. 969 (ed. Arezes, P. M.) 393–403 (Springer International Publishing, 2020).

Bitencourt, D. P., Maia, P. A., Ruas, Á. C. & Cunha, I. D. Â. D. Outdoor work: past, present, and future on occupational heat exposure. Rev. Bras. Saúde Ocupacional. 48, edcinq13 (2023).

Funding

This research was supported by the National Council of Technological and Scientific Development – CNPq (grant number 406498/2022-9).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptual aspects of this work. I.H.S. and L.G.D. conceived the idea, conducted the research, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. B.F.A.O., C.C., and D.P.B. assisted in interpreting the results. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dantas, L.G., de Oliveira, B.F.A., Cremonese, C. et al. Projected productivity losses and economic costs due to heat stress under climate change scenarios in Brazil. Sci Rep 15, 39775 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23487-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23487-w