Abstract

Accurate midpalatal suture maturation assessment is critical for orthodontic treatment planning, yet current manual staging methods exhibit substantial inter-examiner variability (kappa values 0.3-0.8), compromising treatment decision reliability. This study developed and validated DeepMSM, an automated multimodal deep learning framework integrating cone-beam computed tomography with clinical indicators for standardized midpalatal suture staging. We retrospectively analyzed cone-beam computed tomography and lateral cephalometric radiographs from 200 orthodontic patients aged 7-36 years. The DeepMSM framework integrated multimodal images with clinical variables including age, gender, cervical vertebral maturation stage, and mandibular third molar stage using attention-based fusion strategies. DeepMSM achieved 93.75% accuracy and 93.81% F1-score, substantially outperforming single-modality approaches (47.50%-71.25% accuracy) and dual-modality models (73.75–81.25% accuracy). The system demonstrated excellent performance in distinguishing critical stages C and D with F1-scores of 92%-93%, representing the decision point between conventional expansion and surgical intervention. All clinical parameters showed significant correlations with midpalatal suture maturation (p<0.05). DeepMSM, a novel multimodal midpalatal suture maturation assessment system, achieved a high accuracy of 93.75%, demonstrating the potential to reduce diagnostic variability and improve treatment reliability. This automated framework particularly benefits less experienced clinicians in making critical treatment decisions for maxillary expansion therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Transverse maxillary hypoplasia (TMH) represents a common orthodontic condition affecting 13% to 23% of children and up to 30% of adults1. This condition is characterized by inadequate transverse maxillary dimensions, resulting in posterior crossbites, dental crowding, and compromised masticatory function2,3. Beyond dental complications, TMH significantly impacts facial aesthetics and nasal airway patency, with airway narrowing increasing the risk of sleep-disordered breathing and substantially compromising patient quality of life4,5.

Maxillary expansion represents the primary therapeutic intervention for TMH, utilizing lateral orthopedic forces to open the midpalatal suture (MPS) and stimulate new bone formation. The timing and method of expansion are critically dependent on accurate assessment of MPS maturation status6,7. Patients with patent or partially fused sutures are ideal candidates for rapid palatal expansion (RPE), which can achieve 7–10 mm of maxillary expansion with minimal skeletal side effects during the mixed and early permanent dentition phases. Conversely, individuals with advanced suture maturation require alternative approaches such as mini-screw assisted expansion (MSE) or surgically-assisted rapid palatal expansion (SARPE)8,9. This fundamental treatment dichotomy makes precise MPS staging essential for optimal therapeutic outcomes and patient safety10,11,12.

Current clinical practice predominantly uses Angelieri’s five-stage classification system (stages A-E) to evaluate cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) images13. While this system provides a standardized assessment framework, it suffers from significant limitations that compromise clinical decision-making. Inter-examiner reliability varies considerably, with reported weighted kappa values ranging from 0.3 to 0.8, indicating substantial inconsistency in diagnostic interpretation14,15. These variations are particularly pronounced among less-experienced clinicians, especially when distinguishing between stages C and D—a differentiation of paramount clinical importance as stage C represents the optimal window for conventional expansion while stage D typically requires invasive surgical approaches. The subjective nature of manual staging, combined with time-intensive evaluation processes, further limits the standardization of care delivery across different clinical settings.

Recent advances in artificial intelligence have shown promise for automated MPS assessment, offering potential solutions to these diagnostic challenges. Gao et al.16 developed texture-based algorithms for analyzing suture ossification patterns, while Zhu et al.17 achieved 75.37% diagnostic accuracy using deep learning architectures. Tang et al.18 further explored advanced neural network approaches combining Vision Transformers with convolutional neural networks to improve generalization across different patient populations. However, current automated approaches have critical limitations preventing clinical implementation. The reported accuracy levels fall short of the diagnostic reliability required for confident treatment planning decisions. Most significantly, existing single-modality approaches exhibit insufficient precision in distinguishing stage C from adjacent stages B and D—the very distinction that is paramount for determining conventional versus surgical expansion approaches.

Substantial clinical evidence supports the integration of multiple diagnostic indicators for comprehensive MPS assessment. Patient demographics, particularly age and gender, significantly influence suture maturation patterns, with females typically exhibiting earlier fusion compared to males19,20,21. Cervical vertebral maturation (CVM) demonstrates strong correlations with MPS development, where early CVM stages (CS1–CS2) correspond to patent sutures (stages A–B) and advanced CVM stages (CS5–CS6) align with complete suture fusion (stage E)14,22,23. Similarly, mandibular third molar(MTM) calcification patterns show significant correlation with MPS maturation progression24. However, no single clinical indicator adequately captures the complexity of suture maturation, necessitating comprehensive multimodal approaches that can integrate diverse yet complementary biological markers.

This study introduces DeepMSM, a novel multimodal deep learning framework for automated midpalatal suture assessment. The system systematically integrates CBCT images with routinely available clinical indicators, including patient demographics, CVM staging, and MTM development. By leveraging these complementary data sources through advanced artificial intelligence techniques, DeepMSM aims to overcome the limitations of current manual staging approaches while providing standardized, reproducible, and clinically reliable assessments across diverse clinical settings. The framework specifically enhances accuracy in the clinically critical C–D stage differentiation, potentially transforming treatment planning precision for maxillary expansion therapy and advancing the field of intelligent orthodontic diagnostics.

The main contributions of this study are as follows:

-

Novel Multimodal Clinical Assessment Framework: We present a comprehensive automated system that systematically integrates multiple clinical indicators routinely available in orthodontic practice–CBCT imaging, patient demographics, CVM, and MTM development–to achieve a high diagnostic accuracy (93.75%) in MPS staging, with particular strength in the clinically critical C-D stage differentiation.

-

Evidence-Based Validation of Clinical Indicators: Through comprehensive analysis of 200 patients, we establish the relative diagnostic value and optimal integration of multiple clinical parameters in MPS assessment, providing evidence-based guidance for clinical decision-making and advancing understanding of craniofacial maturation patterns.

-

Clinically Applicable Diagnostic Tool: Our system demonstrates consistent diagnostic performance that surpasses typical clinician accuracy while utilizing only routinely acquired clinical data, offering a practical solution for standardizing MPS evaluation across different clinical settings and practitioner experience levels, ultimately improving treatment planning reliability.

Methodology

Study design and participants

Study population

CBCT images and lateral cephalometric radiographs (LCR) images were collected from orthodontic patients seeking treatment between January 2020 and December 2024. All imaging studies were originally performed for routine clinical diagnostic purposes. This retrospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Stomatological Hospital of Fujian Medical University (approval number: [2024] FJMU Oral Ethics Review No. 94). All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations for human subjects research. Given the retrospective nature of this study using anonymized radiographic data originally acquired for routine clinical purposes, the Ethics Committee granted a waiver of informed consent in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Inclusion Criteria: Patients were included if they met the following criteria: (1) Age between 7 and 36 years at the time of imaging; (2) Availability of both CBCT and lateral cephalometric radiographs acquired within a 1-month interval; (3) No history of orthodontic treatment, orthognathic surgery, or maxillofacial trauma; (4) Absence of systemic diseases known to affect bone metabolism (e.g., osteoporosis, hyperparathyroidism, corticosteroid therapy); (5) No severe skeletal deformities, cleft lip and palate, or other craniofacial anomalies that could affect normal suture development.

Exclusion Criteria: Patients were excluded for: (1) Poor image quality preventing adequate visualization of the midpalatal suture region in CBCT images; (2) Inadequate visualization of C2–C4 cervical vertebrae in lateral cephalometric radiographs; (3) Absence of evaluable MTM; (4) Presence of severe dental pathology affecting MTM assessment, including extensive caries, periapical lesions, or significant root resorption.

Imaging acquisition protocol

All CBCT images were acquired using a standardized protocol with the following parameters: 120 kVp, 5 mAs, field of view 16 \(\times\) 13 cm, and voxel size 0.25 mm. Patients were positioned according to manufacturer recommendations with the Frankfort horizontal plane parallel to the floor and the midsagittal plane perpendicular to the floor.

All LCR were obtained using conventional radiographic equipment with standardized patient positioning protocols. All radiographs were taken with consistent magnification factors and exposure parameters to ensure image quality and reproducibility.

The imaging protocol utilized clinically indicated lateral cephalograms and CBCT scans, with all modalities derived from standard diagnostic procedures without additional exposure, strictly following ALARA(As Low As Reasonably Achievable) principles and AAOMR guidelines43 for radiation protection.

Dataset characteristics

The final study cohort comprised 200 patients (75 males, 125 females) with a mean age of \(16.65 \pm 6.03\) years (range: 7–36 years). The dataset was randomly stratified into training (60%, n=120), validation (20%, n=40), and testing (20%, n=40) sets with balanced representation of MPS maturation stages across all subsets.

The dataset included three imaging modalities: (1) midpalatal suture regions from CBCT (MPS-CBCT), (2) mandibular third molar regions from CBCT (MTM-CBCT), and (3) cervical vertebrae regions from lateral cephalograms (CVM-LCR). Clinical variables included patient demographics (age, gender) and maturation staging assessments (CVM and MTM stages). The dataset was randomly partitioned at the patient level to ensure that all data modalities for a single patient belonged exclusively to either the training, validation, or testing set, thereby preventing any risk of information leakage.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 26.0, IBM Corp.) with significance level set at \(p < 0.05\). Detailed statistical analyses can be found in Section.

Image analysis and clinical assessment

Image processing and region extraction

All CBCT DICOM datasets were processed using Ez3D Plus imaging software (Vatech, Korea) following standardized protocols. Three anatomical regions were systematically extracted for each patient:

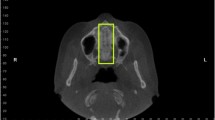

Midpalatal Suture Region (MPS-CBCT): Coronal cross-SMctions were obtained at the palatal plane passing through the posterior nasal spine, visualizing the complete suture anatomy from anterior to posterior nasal spine for consistent anatomical orientation and morphological assessment.

Mandibular Third Molar Region (MTM-CBCT): Cross-SMctional images were extracted along the long axis of MTM. When bilateral mandibular third molars were present, the tooth with more advanced developmental stage was selected for analysis.

Cervical Vertebral Region (CVM-LCR): Lateral cephalometric radiographs (LCR) were processed to extract C2–C4 cervical vertebrae regions, emphasizing inferior border characteristics and concavity patterns essential for maturation staging.

All extracted images underwent standardized preprocessing, including resizing to 224 \(\times\) 224 pixels and intensity normalization for consistent computational analysis and compatibility with ResNet-based visual backbones.

Clinical staging assessment

Clinical staging assessments was performed by two orthodontists (each with over 10 years of clinical experience) and one senior orthodontic specialist (over 30 years of experience), all possessing extensive expertise in craniofacial radiographic interpretation. The two orthodontists independently performed the staging assessments, with any discrepant cases being adjudicated by the senior specialist. Final staging determinations required consensus from at least two of the three evaluators.

Images of MPS stages based on Angelieri’s five-stage system (A–E). Midpalatal suture maturation stages based on Angelieri’s classification system. Representative CBCT coronal sections showing the five stages of midpalatal suture development: Stage A shows straight high-density sutural line; Stage B displays scalloped appearance with occasional parallel lines; Stage C presents two parallel scalloped lines with small separations; Stage D demonstrates fusion in posterior region with visible suture anteriorly; Stage E shows complete fusion with no visible suture.

Images of CVM stages based on Baccetti’s classification method (CS1–CS6). Cervical vertebral maturation stages based on Baccetti’s classification method. Lateral cephalometric radiographs illustrating the six stages of cervical vertebral development: CS1-CS6 showing progressive morphological changes in C2-C4 vertebral bodies, including concavity development at inferior borders and overall vertebral shape modifications used for skeletal maturity assessment.

Images of MTM stages based on Demirjian’s classification method (A–H). Mandibular third molar development stages based on Demirjian’s classification system. CBCT cross-sectional images demonstrating the eight stages of mandibular third molar development: Stages A-H showing progression from initial crown mineralization to complete root formation with closed apex, used for dental maturity assessment.

MPS Maturation Staging (MPS Stage): As shown in Figure 1, MPS maturation was classified using Angelieri’s five-stage system13: Stage A (straight high-density sutural line), Stage B (scalloped appearance with occasional parallel lines), Stage C (two parallel scalloped lines with small separations), Stage D (fusion in posterior region with visible suture anteriorly), and Stage E (complete fusion with no visible suture).

Cervical Vertebral Maturation (CVM Stage): As shown in Figure 2, CVM staging followed Baccetti’s six-stage method25, evaluating morphological characteristics of C2–C4 vertebral bodies, including concavity presence, depth, and extent at inferior borders, and overall vertebral shape modifications.

Mandibular Third Molar Development (MTM Stage): As shown in Figure 3, MTM development was assessed using Demirjian’s eight-stage classification system26, evaluating crown formation, root development, mineralization patterns, and apical closure status from Stage A (initial crown mineralization) to Stage H (complete root formation with closed apex).

Design of DeepMSM

Overall architecture

As shown in Figure 4, the DeepMSM (Deep Learning for Midpalatal Suture Maturation) framework represents a novel multimodal artificial intelligence system specifically designed for automated MPS staging in clinical practice. The system architecture integrates multiple data sources routinely available in orthodontic practice: three imaging modalities (MPS-CBCT, MTM-CBCT, CVM-LCR) and tabular variables (patient age, gender, CVM stage, MTM stage).

The framework employs a hierarchical integration approach, utilizing deep convolutional neural networks for image feature extraction and multilayer perceptron networks for tabular data processing. These modality-specific features are subsequently integrated through attention-based fusion mechanisms to generate comprehensive multimodal representations for final classification.

Schematic overview of the proposed DeepMSM architecture. Three imaging modalities (MPS-CBCT, MTM-CBCT, and CVM-LCR) are each passed through a shared ResNet-50 encoder (pre-trained on the RadImageNet dataset27), followed by an MLP-based encoder for tabular features (Age, Gender, CVM stage, MTM stage). The resulting feature vectors are concatenated and passed into a classification head that outputs the MPS maturation stage \(\{A,B,C,D,E\}\). Schematic overview of the DeepMSM architecture. The multimodal deep learning framework integrates three imaging modalities (MPS-CBCT, MTM-CBCT, and CVM-LCR) through shared ResNet-50 encoders pre-trained on RadImageNet, combined with MLP-based processing of tabular features (age, gender, CVM stage, MTM stage). Feature vectors are concatenated and processed through a classification head to output MPS maturation stages A-E.

Image feature extraction

Enhanced ResNet-50 Backbone:

Image features are extracted using ResNet-50 architectures28 enhanced with Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM)29 and initialized with RadImageNet pre-trained weights27. Each imaging modality is processed through identical encoder networks:

where \(I_{\alpha }\) represents the input image for modality \(\alpha\) and \(\textbf{z}_{\alpha } \in \mathbb {R}^{128}\) is the extracted feature vector.

Attention Mechanism: The CBAM attention module29 enhances feature representation through sequential channel and spatial attention:

where \(M_c\) and \(M_s\) represent channel and spatial attention modules, \(\otimes\) denotes element-wise multiplication, and \(\sigma\) is the sigmoid activation function.

Tabular data processing

Tabular variables are processed through a unified MLP architecture with embedding layers for categorical variables:

where \(\tilde{T}_{\textrm{age}} = \frac{T_{\textrm{age}} - \mu _{\textrm{age}}}{\sigma _{\textrm{age}}}\) represents normalized age, and \(\textrm{Embed}(\cdot )\) denotes learnable embedding functions for categorical variables.

Multimodal fusion strategy

Hierarchical Attention-Based Fusion: Image features are first combined through attention-weighted fusion:

Image and tabular features are then projected to a common space with gating mechanisms:

where \(\odot\) represents element-wise multiplication and \([\cdot , \cdot ]\) denotes concatenation.

Classification and training strategy

Classification Head: The fused representation is processed through a multi-layer classification network:

Class probabilities are computed using softmax: \(p(y=c|\textbf{x}) = \frac{\exp (z_c)}{\sum _{c'=1}^5 \exp (z_{c'})}\) for MPS stages \(c \in \{A, B, C, D, E\}\).

Progressive Training Strategy: A three-stage training approach was implemented to optimize model performance. In the first stage, image encoder components were trained while tabular data processing components remained frozen (learning rate: 0.001). The second stage integrated tabular data processing while maintaining frozen image features (learning rate: 0.0005). Finally, the third stage performed end-to-end fine-tuning of all system parameters (learning rate: 0.0001). This progressive approach ensures stable convergence and optimal utilization of the limited training dataset.

Weighted cross-entropy loss is employed to address class imbalance:

where \(w_c = \frac{N}{5 \cdot N_c}\) with N representing the total number of samples, \(N_c\) being the number of samples in stage c, and \(c \in \{A, B, C, D, E\}\).

Tabular integration and interpretability

DeepMSM is designed for seamless integration into clinical workflows, utilizing only routinely acquired diagnostic data without requiring additional examinations or specialized equipment. The system provides interpretable outputs through attention visualization techniques, allowing clinicians to understand the basis for automated predictions and maintain clinical oversight of the diagnostic process.

Results

Study population characteristics

A total of 200 participants were enrolled in this study, comprising 75 males (mean age \(15.12 \pm 4.85\) years) and 125 females (mean age \(17.57 \pm 6.47\) years). The overall mean age was \(16.65 \pm 6.03\) years, reflecting the study’s focus on adolescents and young adults undergoing orthodontic evaluation. The age and gender distribution across different developmental stages is presented in Table 1.

The distribution shows a predominance of participants in the 12–17 age group (47%), followed by the 18–29 age group (34%), which is consistent with typical orthodontic patient demographics seeking maxillary expansion treatment.

Statistical analysis

MPS stage distribution patterns

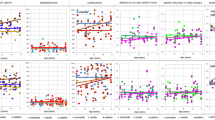

Figure 5 illustrates the distribution of MPS stages across key clinical predictors, demonstrating systematic developmental relationships that support multimodal prediction approaches.

Distribution of MPS stages across clinical predictors: (a) Age groups, (b) CVM stages, (c) MTM stages. Distribution of MPS stages across clinical predictors. Bar charts showing the distribution of midpalatal suture stages across: (a) age groups demonstrating age-related progression patterns; (b) cervical vertebral maturation stages showing developmental correspondence; (c) mandibular third molar stages revealing correlation with dental development.

Age-related distribution revealed distinct patterns with early MPS stages (A and B) predominantly occurring in younger participants (Age <12: 83% stages A–B; Age 12–17: 61% stages A–B), while advanced stages (D and E) showed higher frequencies in older age groups (Age 18–29: 54% stages D–E; Age \(\ge\)30: 75% stages D–E).

CVM stage correlations demonstrated strong developmental correspondence, with early MPS stages (A–B) primarily aligning with early CVM stages (CS1–CS3: 78% stages A–B), and later MPS stages (D–E) correlating with advanced CVM stages (CS4–CS6: 69% stages D–E).

MTM stage correlations showed that MPS-A corresponded primarily to early MTM stages (A–C: 85%), while MPS-D and MPS-E were predominantly associated with advanced MTM stages (F–H: 71%).

Inter-variable correlation analysis

Spearman rank correlation analysis revealed significant relationships among all variables (\(p < 0.05\)), as shown in Figure 6. The strongest correlation was observed between age and MTM stage (\(\rho = 0.74\)), followed by strong correlations between MTM stage and MPS stage (\(\rho = 0.63\)), MTM stage and CVM stage (\(\rho = 0.63\)), age and CVM stage (\(\rho = 0.54\)), and CVM stage and MPS stage (\(\rho = 0.52\)). A moderate correlation was found between age and MPS stage (\(\rho = 0.48\)).

Heatmap of Spearman Correlation Matrix among MPS stage, MTM stage, CVM stage, and Age (All correlations significant, p<0.05). Correlation coefficients (\(\rho\)) indicate: \(|\rho |\) \(\ge\) 0.5 (strong), 0.3\(\le\) \(|\rho |\) \(<\)0.5. Spearman correlation matrix among clinical variables. Heatmap displaying correlation coefficients between MPS stage, MTM stage, CVM stage, and age. All correlations are statistically significant (p<0.05), with correlation strength indicated by color intensity and numerical values.

These correlations validate the biological rationale for multimodal integration while indicating that individual predictors provide complementary rather than redundant information for MPS stage determination.

Model performance comparison

Table 2 presents comprehensive performance metrics across all evaluated models, revealing clear advantages of multimodal integration. DeepMSM achieved the highest diagnostic performance with 93.75% accuracy and 93.81% F1-score, demonstrating superior capability compared to all other evaluated approaches.

Semi-multimodal models utilizing both CBCT and LCR achieved moderate performance, with ResNet50-SM28 reaching 81.25% accuracy, EfficientNet-SM30 achieving 75%, and ResNet18-SM28 obtaining 73.75%. These dual-modality approaches demonstrated the complementary value of combining three-dimensional suture morphology with cervical vertebral maturation indicators, yet remained insufficient for tabular implementation.

Single-modality approaches showed considerable variation in performance across different data sources and architectures. Among CBCT-only models, ResNet50-SG28 achieved the highest accuracy of 71.25%, followed by EfficientNet-SG30 at 70% and ResNet18-SG28 at 56.25%. The tabular data-only baseline model (MLP-SG) achieved only 47.50% accuracy, demonstrating that traditional clinical indicators alone are inadequate for reliable MPS staging. This limited performance of the MLP-SG baseline underscores the complexity of craniofacial maturation patterns that cannot be captured through demographic and developmental parameters without accompanying imaging data.

Manual assessment by orthodontic residents demonstrated substantial challenges, with accuracy rates of 40.11% and 30.36% respectively, highlighting the inherent difficulty of subjective MPS evaluation even with complete access to imaging and tabular information. The performance hierarchy clearly demonstrates the incremental value of multimodal data integration, with DeepMSM’s 93.75% accuracy representing a substantial 12.5% improvement over the best semi-multimodal approach and a 46.25% improvement compared to the tabular baseline (MLP-SG). Most significantly, the automated framework achieved more than double the accuracy of manual assessment, emphasizing the substantial clinical value of standardized, objective diagnostic approaches.

Detailed performance analysis of DeepMSM

Stage-specific performance

Figure 7 presents the confusion matrix and detailed classification metrics, revealing stage-specific model performance patterns.

(a) The confusion matrix normalized by row percentages, showing the distribution of predicted labels for classes A–E. (b) The Precision, Recall, and F1-scores for each class. DeepMSM classification performance analysis. (a) Confusion matrix normalized by row percentages showing distribution of predicted labels for MPS stages A-E. (b) Precision, recall, and F1-scores for each stage demonstrating excellent performance across all maturation stages, particularly for clinically critical stages C and D.

DeepMSM demonstrated excellent performance for extreme maturation stages, with Stage A achieving precision of 97%, recall of 95%, and F1-score of 96%, while Stage E reached precision of 96%, recall of 98%, and F1-score of 97%. These results reflect the distinct morphological characteristics of early and complete suture maturation stages, which facilitate reliable automated identification.

For the clinically critical intermediate stages, the system maintained strong diagnostic accuracy across all parameters. Stage B demonstrated precision of 92%, recall of 89%, and F1-score of 91%, while Stage C achieved precision of 91%, recall of 93%, and F1-score of 92%. Most importantly, Stage D showed precision of 94%, recall of 91%, and F1-score of 93%, confirming the model’s capability to accurately identify this crucial treatment decision threshold.

Analysis of misclassification patterns revealed that 87% of errors occurred between adjacent developmental stages, a finding that aligns with clinical expectations given the gradual nature of biological maturation processes. This error distribution is clinically acceptable, as even experienced orthodontists face inherent challenges in distinguishing transitional phases where morphological features overlap between consecutive maturation stages.

Clinical decision-making impact

The model’s ability to accurately distinguish between Stages C and D (92% and 93% F1-scores respectively) is particularly significant for clinical practice, as this differentiation directly determines treatment approach selection between conventional rapid maxillary expansion and surgically-assisted expansion protocols.

Model interpretability and clinical relevance

Model interpretability and validation

Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) analysis was employed to visualize and validate the anatomical regions contributing to model decision-making processes (Figure 8). The analysis demonstrated that DeepMSM consistently focused on clinically relevant anatomical structures across all imaging modalities. For cervical vertebral images (CVM-LCR), the model primarily concentrated on C2–C4 vertebral body morphology, particularly the inferior border concavity patterns that are fundamental to established CVM staging criteria. In midpalatal suture images (MPS-CBCT), attention was concentrated on the posterior midpalatal suture regions and surrounding bone density variations, which correspond to the anatomical features used by clinicians for manual MPS assessment. For mandibular third molar images (MTM-CBCT), the model emphasized root development patterns and apical closure status, aligning with the key parameters in Demirjian’s classification system.

Grad-CAM visualizations of the CVM-LCR, MTM-CBCT, and MPS-CBCT modalities. Heatmaps indicate discriminative regions associated with automated decision-making, with red representing high diagnostic relevance and blue representing low relevance. The attention patterns demonstrate that the model focuses on clinically established anatomical landmarks for each modality. Grad-CAM visualization of model attention patterns. Heatmaps showing discriminative regions for each imaging modality: CVM-LCR focuses on cervical vertebrae morphology; MTM-CBCT emphasizes root development patterns; MPS-CBCT highlights posterior suture regions. Red indicates high diagnostic relevance, blue represents low relevance, confirming anatomically meaningful feature learning.

These activation patterns provide strong evidence that DeepMSM has learned to identify and utilize the same anatomical features that experienced orthodontists rely upon for manual assessment, supporting the model’s biological validity and clinical applicability.

Clinical validation insights

The systematic attention to anatomically relevant structures demonstrates that DeepMSM has learned clinically meaningful features rather than spurious correlations, supporting its potential for reliable clinical deployment and integration into standard orthodontic diagnostic workflows.

Discussion

This study introduces the DeepMSM framework, a multimodal deep learning system that addresses the critical challenge of accurately assessing midpalatal suture (MPS) maturation. By integrating CBCT, LCR, and clinical data, the model achieved a high accuracy of 93.75%, demonstrating strong performance in differentiating between the clinically pivotal Stages C and D (92% and 93% F1-scores, respectively). This capability directly informs the crucial decision between conventional rapid palatal expansion (RPE) and surgically-assisted rapid palatal expansion (SARPE), promising to enhance treatment planning in orthodontics.

Our results highlight the limitations of current assessment methods, which rely on subjective radiographic interpretation and suffer from significant inter-examiner variability, with reported agreement rates often below 80%13,15,34. Manual assessments by orthodontic residents in our study yielded accuracies between 30.36% and 40.11%, a finding consistent with benchmarks reported by Chhatwani et al.34, which showed a clear expertise gradient in MPS classification. DeepMSM substantially outperforms these manual baselines by leveraging a multimodal approach that synthesizes three-dimensional anatomical insights from CBCT with skeletal and dental maturation indicators. This integration provides a more comprehensive and objective assessment than any single modality alone. The model’s misclassifications were predominantly between adjacent stages (87%), which is clinically understandable given the gradual nature of biological maturation.

The clinical implications of DeepMSM are twofold. Primarily, it offers a standardized and reproducible tool that can reduce the risk of inappropriate treatment. Accurate identification of Stage C can prevent unnecessary surgeries, while precise Stage D identification helps avoid failed conventional expansion attempts. Secondly, the model serves as a valuable educational and trust-building instrument. Our Grad-CAM visualizations confirm that DeepMSM focuses on clinically relevant anatomical landmarks–such as C2-C4 vertebral morphology and posterior suture characteristics–which fosters clinician trust and acceptance. This transparency also provides an objective guide for trainees, helping to standardize diagnostic approaches and shorten the learning curve associated with this complex assessment.

Despite its promising performance, this study has several limitations that must be acknowledged. First, the single-center, retrospective design necessitates comprehensive external validation to confirm its generalizability across diverse populations, imaging protocols, and clinical settings. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits insights into individual maturation trajectories, a gap that could be addressed by future longitudinal research. Third, our study’s age distribution (mainly 12–29 years) underrepresents older patients who often require MARPE or SARPE due to complete suture fusion35,40,41, and future multi-center studies should include more mature cases. Finally, our use of 2D images, while computationally efficient, could be enhanced by full 3D architectures in future work.

Future research will focus on addressing these limitations through prospective, multi-center clinical trials to establish the real-world clinical utility of DeepMSM. Technologically, future iterations of the framework may incorporate advancements in AI to further enhance performance. Critically, the successful deployment of DeepMSM requires seamless and responsible integration into clinical workflows. While the system is designed for compatibility with existing PACS and EHR systems, its implementation must be guided by robust data governance and security practices. As recent literature on medical imaging AI emphasizes, addressing legal, ethical, and cybersecurity risks–such as patient consent, data minimization, and security–is paramount for the safe deployment of such technologies in clinical settings42.

In summary, DeepMSM represents significant progress toward objective, evidence-based orthodontic assessment. By providing standardized and accurate MPS staging, it serves as an essential decision support tool that complements clinical expertise, with the potential to significantly improve the reliability and safety of maxillary expansion therapy.

Conclusion

This study successfully developed and validated DeepMSM, a multimodal deep learning framework for automated midpalatal suture maturation assessment. The framework achieved 93.75% accuracy by integrating CBCT imaging, lateral cephalometric radiographs, and clinical indicators, substantially outperforming single-modality approaches (47.50%-81.25%) and manual assessment (30.36%-40.11%).

The framework’s ability to accurately distinguish between Stages C and D (92-93% F1-scores) directly addresses the critical clinical challenge in treatment selection between conventional and surgically-assisted maxillary expansion. Grad-CAM analysis confirmed that the model focuses on anatomically relevant structures, supporting its clinical validity.

Study limitations include single-center validation and the need for broader population testing. Future research should focus on multi-center validation and prospective clinical trials to evaluate real-world implementation. Additionally, the systematic exploration and integration of newer generation encoders represents an important direction for future work, as our modular framework design specifically supports such upgrades to benefit from advances in backbone architectures.

DeepMSM provides clinicians with a standardized, objective diagnostic tool that has the potential to improve treatment outcomes for patients requiring maxillary expansion therapy.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request, subject to ethical approval and data protection regulations.

Code availability

The DeepMSM framework code is available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Ye, G. et al. Comparative evaluation of transverse width indices for diagnosing maxillary transverse deficiency. BMC Oral Health 24, 808 (2024).

Andrucioli, M. C. D. & Matsumoto, M. A. N. Transverse maxillary deficiency: Treatment alternatives in face of early skeletal maturation. Dental Press J. Orthod. 25, 70–79 (2020).

Betts, N. J. et al. Diagnosis and treatment of transverse maxillary deficiency. Int. J. Adult Orthodon. Orthognath. Surg. 10, 75–96 (1995).

Brunetto, D. P., Sant’Anna, E. F., Machado, A. W. & Moon, W. Non-surgical treatment of transverse deficiency in adults using microimplant-assisted rapid palatal expansion (MARPE). Dental Press J. Orthod. 22, 110–125 (2017).

Vanarsdall, R. L. Jr. Transverse dimension and long-term stability. Semin. Orthod. 5, 171–180 (1999).

Sawchuk, D. et al. Diagnostic methods for assessing maxillary skeletal and dental transverse deficiencies: A systematic review. Korean J. Orthod. 46, 331–342 (2016).

Maraón-Vásquez, G. A. et al. Effect of treatment of transverse maxillary deficiency using rapid palatal expansion on oral health-related quality of life in children: complementary results for a controlled clinical trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 28, 520 (2024).

Kılıç, N., Kiki, A. & Oktay, H. A comparison of dentoalveolar inclination treated by two palatal expanders. Eur. J. Orthod. 30, 67–72 (2008).

Rungcharassaeng, K. et al. Factors affecting buccal bone changes of maxillary posterior teeth after rapid maxillary expansion. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 132(428), e1-428.e8 (2007).

Garib, D. G. et al. Rapid maxillary expansion-tooth tissue-borne versus tooth-borne expanders: A computed tomography evaluation of dentoskeletal effects. Angle Orthod. 75, 548–557 (2005).

Bell, W. H. & Epker, B. N. Surgical-orthodontic expansion of the maxilla. Am. J. Orthod. 70, 517–528 (1976).

Betts, N. J. et al. Diagnosis and treatment of transverse maxillary deficiency. Int. J. Adult Orthodon. Orthognath. Surg. 10, 75–96 (1995).

Angelieri, F. et al. Midpalatal suture maturation: Classification method for individual assessment before rapid maxillary expansion. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 144, 759–769 (2013).

Angelieri, F., Franchi, L., Cevidanes, L. H. S. & McNamara, J. A. Jr. Diagnostic performance of skeletal maturity for the assessment of midpalatal suture maturation. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 148, 1010–1016 (2015).

Barbosa, N. M. V. et al. Reliability and reproducibility of the method of assessment of midpalatal suture maturation: A tomographic study. Angle Orthod. 89, 71–77 (2019).

Gao, L. et al. Midpalatal suture CBCT image quantitive characteristics analysis based on machine learning algorithm construction and optimization. Bioengineering 9, 316 (2022).

Zhu, M. et al. Convolutional neural network-assisted diagnosis of midpalatal suture maturation stage in cone-beam computed tomography. J. Dent. 141, 104808 (2024).

Tang, H. et al. Prediction of midpalatal suture maturation stage based on transfer learning and enhanced vision transformer. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 24, 232 (2024).

Jimenez-Valdivia, L. M. et al. Midpalatal suture maturation stage assessment in adolescents and young adults using cone-beam computed tomography. Prog. Orthod. 20, 38 (2019).

Ferrillo, M., Daly, K., Pandis, N. & Fleming, P. S. The effect of vertical skeletal proportions, skeletal maturation, and age on midpalatal suture maturation: a CBCT-based study. Prog. Orthod. 25, 17 (2024).

Cokuner, H. G., Atik, E. & Taner, T. Relationship between midpalatal suture maturation and age and maturation of cervical vertebrae: radiographic evaluation. Acta Odontol. Turc. 35, 79–85 (2018).

Jang, H. I. et al. Relationship between maturation indices and morphology of the midpalatal suture obtained using cone-beam computed tomography images. Korean J. Orthod. 46, 345–355 (2016).

Liu, H., Feng, L. & Wang, L. Diagnostic value of cervical vertebral maturation stages for midpalatal suture maturation assessment: a study in the Chinese population. BMC Oral Health 23, 495 (2023).

Šefeldaitė, S. et al. Correlation between third molar mineralization and midpalatal suture maturity: A cone beam computed tomography study. Med. Sci. Monit. 29, e940539 (2023).

Baccetti, T., Franchi, L. & McNamara, J. A. Jr. An improved version of the cervical vertebral maturation (CVM) method for the assessment of mandibular growth. Angle Orthod. 72, 316–323 (2002).

Demirjian, A. Dental development: An index of physiological maturity. Union Med. Can. 109, 832–839 (1980).

Mei, X. et al. RadImageNet: An open radiologic deep learning research dataset for effective transfer learning. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 4, e210315 (2022).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 770–778 (2016).

Woo, S., Park, J., Lee, J. Y. & Kweon, I. S. CBAM: convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV) 3–19 (2018).

Tan, M. & Le, Q. Efficientnet: rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In International Conference on Machine Learning 6105–6113 (PMLR, 2019).

Baccetti, T., Franchi, L., Cameron, C. G. & McNamara, J. A. Jr. Treatment timing for rapid maxillary expansion. Angle Orthod. 71, 343–350 (2001).

Sayar, G. & Kılınç, D. D. Rapid maxillary expansion outcomes according to midpalatal suture maturation levels. Prog. Orthod. 20, 35 (2019).

Kapetanović, A. et al. Efficacy of miniscrew-assisted rapid palatal expansion (MARPE) in late adolescents and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Orthod. 43, 313–323 (2021).

Chhatwani, S. et al. Performance of dental students, orthodontic residents, and orthodontists for classification of midpalatal suture maturation stages on cone-beam computed tomography scans-a preliminary study. BMC Oral Health 24, 373 (2024).

Angelieri, F. et al. Cone beam computed tomography evaluation of midpalatal suture maturation in adults. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 46, 1562–1570 (2017).

Mahdian, A. et al. Correlation assessment of cervical vertebrae maturation stage and mid-palatal suture maturation in an Iranian population. J. World Fed. Orthod. 9, 134–138 (2020).

Estrada, J. T. et al. Correlation between cervical vertebrae maturation and midpalatal suture fusion in patients aged between 10 and 20 years: a cross-sectional and 3D study. Int. Orthod. 20, 100659 (2022).

Kumar, S. et al. Skeletal maturation evaluation using mandibular second molar calcification stages. Angle Orthod. 82, 501–506 (2012).

Chen, J. et al. Correlation between dental maturity and cervical vertebral maturity. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 110, 777–783 (2010).

Colonna, A. et al. Association of the mid-palatal suture morphology to the age and to its density: A CBCT retrospective comparative observational study. Int. Orthod. 19(2), 235–242 (2021).

Gonzálvez Moreno, A. M. et al. Cone Beam Computed Tomography evaluation of midpalatal suture maturation according to age and sex: A systematic review. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 23(1), 44–50 (2022).

Kováč, J. et al. AI-driven facial image analysis for early detection of rare diseases: Legal, ethical, forensic, and cybersecurity considerations. AI 5, 723–736 (2024).

American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology. Clinical recommendations regarding use of cone beam computed tomography in orthodontics. [corrected]. Position statement by the American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol116(2), 238–257 (2013).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82501193), the Project of Fujian Provincial Department of Finance (No. 2024CZZX04), the Startup Fund for Scientific Research, Fujian Medical University (No. 2024QH1163), and the Fujian Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Nos. 2025J01807 and 2025J01123719).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.C., Z.W., and H.W. conceived the study and designed the methodology. J.C., Z.W., H.W., and Z.C. collected and preprocessed the data. Z.L. developed the deep learning algorithms and implemented the code. Z.C. and Q.Y. conducted the experiments and analyzed the results. Z.L. and L.X. supervised the project and provided critical guidance. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This retrospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Stomatological Hospital of Fujian Medical University (approval number: [2024] FJMU Oral Ethics Review No. 94). All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations including the Declaration of Helsinki and institutional ethical standards for human subjects research. Given the retrospective nature of this study using anonymized radiographic data originally acquired for routine clinical diagnostic purposes, the Ethics Committee granted a waiver of informed consent in accordance with institutional guidelines and applicable regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable. This study used only anonymized radiographic data with no identifiable patient information or images.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cai, J., Wang, Z., Wang, H. et al. Multimodal deep learning for midpalatal suture assessment in maxillary expansion. Sci Rep 15, 39723 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23500-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23500-2