Abstract

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal neurodegenerative disease affecting motor neurons in the motor cortex, brainstem, and the spinal cord. In response to neurodegeneration, spinal cord exhibits ineffective regenerative attempt, thus suggesting that therapeutic strategies aimed at enhancing regenerative capacity of ependymal stem/progenitor cells (epSPCs), residing in the spinal cord, could promote neurogenesis. Dysregulated levels of metabolites might disturb epSPC differentiation, and their restoration might favour neurogenesis. This study aimed to investigate the metabolomic profile of epSPCs from ALS mice to identify altered metabolites as novel therapeutic targets for precision treatment. We performed a metabolome analysis to investigate changes in epSPCs from ALS compared to control male mice (B6SJL-Tg (SOD1*G93A)1Gur/J) and treated the epSPCs with FM19G11-loaded nanoparticles (NPs) to reestablish metabolic balance. Metabolomics analysis revealed significant changes in ALS epSPCs compared to controls. In vitro treatment with FM19G11-loaded nanoparticles (NPs) restored key metabolic networks, particularly in pathways related to glucose, glutamate and glutathione metabolism. These findings highlight the potential of FM19G11-loaded NPs to revert metabolic dysregulation in ALS epSPCs, providing a basis for innovative metabolic therapies and precision medicine approaches to counteract motor neuron degeneration in ALS and other motor neuron diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal disorder that affects motor neurons in the motor cortex, brainstem and spinal cord1. About 90% of cases are sporadic and of unknown origin, while ~ 10% are familial (FALS); among these, ~ 20% result from superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) mutations. Both sporadic and familial ALS involve loss of upper and/or lower motor neurons, leading to similar pathology. SOD1 is ubiquitously expressed in human cells, with its transcription regulated by basal transcription factors. Immunoreactivity for SOD1 has been detected in the nervous system, particularly in motor neurons, small interneurons, astrocytes within the white matter, and ependymal cells lining the central canal2. Mutations in the SOD1 gene, which encodes the antioxidant enzyme superoxide dismutase 1, represent a well-characterized genetic cause of familial ALS. These mutations lead to misfolding and aggregation of SOD1, triggering oxidative stress, glutamate excitotoxicity, mitochondrial dysfunction, and ultimately motor neuron degeneration, thereby playing a central role in ALS pathology3. The ALS neurodegenerative process stimulates an extensive but unproductive renewing response in the spinal cord4,5,6.

Our previous study showed a regeneration attempt mainly consisting of a proliferative response of ependymal stem progenitor cells (epSPCs) in spinal cord of the ALS G93A-SOD1 mouse model6. In addition, we demonstrated an enhanced proliferation and self-renewal of G93A-SOD1 mouse epSPCs after in vitro treatment with gold nanovectors loaded with FM19G11, a hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) modulator7. FM19G11 modulates key signaling pathways involved in cell survival and proliferation by upregulating pluripotency-associated genes, such as SOX2, OCT4, and AKT, as well as proliferation-related genes, including AKT1 and TERT7. By enhancing the self-renewal and differentiation potential of stem and progenitor cells, FM19G11 may promote neuroregeneration. Moreover, its ability to regulate mitochondrial function modulating mitochondrial uncoupling proteins, neuroinflammatory pathways and glucose metabolisms makes it a particularly promising candidate for ALS therapy, where motor neuron degeneration is driven by these pathogenic mechanisms7,8,9,10. Of note, human spinal cord SPCs are able to differentiate into the three neural cell lineages, thus implying that epSPC stimulation and differentiation may represent a strategy to counteract, or even reverse, motor neuron degeneration in ALS.

Disruptions in energy homeostasis and metabolism emerge in ALS and are considered central to disease pathogenesis11,12. Cerebral glucose uptake is reduced in patients, with distinct metabolic patterns observed across genetic backgrounds (SOD1, C9ORF72, and sporadic ALS), suggesting region-specific vulnerabilities13. In parallel, glutamate metabolism is disrupted, and excess glutamate contributes to motor neuron degeneration through excitotoxicity, calcium overload, and modulation of astrocytic reactivity14. Oxidative stress further exacerbates neuronal damage, while dysfunction of the glutathione pathway, particularly in the context of SOD1 mutations, enhances motor neuron vulnerability, highlighting this pathway as a promising therapeutic target15.

Due to the increasing evidence that an imbalance in the energy homeostasis contributes to ALS pathology, targeting the energy metabolism is emerging as a potential therapeutic strategy. Most approaches focused on enhancing the supply of energetic substrates, manipulating metabolic fluxes, or optimizing mitochondrial function16. In this context, dysregulated levels of metabolites might disturb epSPC differentiation, and their restoration might favour their proliferation and differentiation, as well as the release of neurotrophic factors. Indeed, metabolites play a pivotal role in regulating neural stem cell fate. It is known that amino acid metabolism, particularly via glutamine and its derivative α-ketoglutarate, modulates epigenetic reprogramming during differentiation, serving as substrates for histone and DNA demethylases17. Furthermore, intermediates from glycolysis, the TCA cycle, and the pentose phosphate pathway are known to impact key epigenetic regulators thereby shaping neural stem cell fate decisions17.

The aim of this study was to investigate the metabolomic profile of ALS epSPCs to identify altered metabolites as novel therapeutic targets for disease treatment. For this purpose, we employed a systems metabolomics approach to comprehensively profile and identify metabolic alteration in ALS mouse epSPCs at distinct stages of disease development and progression. Given that FM19G11 modulates HIF pathway and plays a key role in global metabolic regulation8, we explored the therapeutic potential of biodegradable poly-lactide-co-glycolide (PLGA) nanoparticles (NPs) loaded with FM19G11 to restore metabolic balance in ALS epSPCs.

Methods

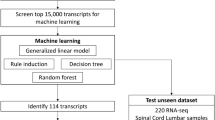

The study design is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Workflow of metabolic reprogramming in ALS epSPCs by FM19G11 nanotherapy. (A) Isolation and characterization of epSPCs derived from G93A-SOD1 and B6SJL mice at week 8, 12, 18 of age. Characterization involved immunofluorescence and metabolomic analyses. (B) Isolation of epSPCs derived from G93A-SOD1 mice at week 8, 12, 18 of age and treatment with FM19G11-loaded nanoparticles. Evaluation of FM19G11 effects on metabolome was performed by metabolomic and gene expression analysis. The workflow scheme was designed using BioRender.com. Biorender: Created in BioRender. Cattaneo, M. (2025) https://BioRender.com/t867o2h.

All reagents are detailed in Supplemental Table 1.

Animals

Transgenic G93A-SOD1 (B6SJL-Tg(SOD1*G93A)1Gur/J) and B6SJL (control) mice purchased from Charles River, Inc. (Wilmington, MA, USA) were maintained and bred at the animal house of the Fondazione IRCCS Carlo Besta Neurological Institute, in compliance with institutional guidelines and international regulations (EEC Council Directive 86/609). G93A-SOD1 mice were identified via real time PCR analysis using human SOD1-specific primers as previously described18. G93A-SOD1 male animals carrying more than 27 mutant SOD1 copies were included in the study with an optimal weight of 25 g. The animals were monitored daily. Male mice were used in all studies and sacrificed by exposure to carbon dioxide at different post-natal weeks: 8 (pre-symptomatic phase), 12 (disease onset), and 18 (late symptomatic phase)18. The work has been reported in line with the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0.

Preparation of FM19G11 loaded nanoparticles

The NPs were prepared by the solvent evaporation method using polyvinyl alcohol (PVA; 30–70 kDa, 87–89% hydrolyzed; Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) as surfactant to ensure colloidal stability in the biological environment while minimizing protein adsorption onto the NP surface. Briefly, FM19G11 (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) was solubilized in dichloromethane (DCM) to prepare a solution at 0.5 mg mL−1 concentration. Subsequently, the polymer (20 mg, PLGA; Resomer 502 H, 50:50, 7–17 kDa; Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) was dissolved in 1 mL of the FM19G11-containing solution. The resulting organic phase was drop-wise added to 4 mL of aqueous solution, containing 2% w/v PVA. The dispersion was then sonicated using a tip sonicator at 60 W for 60 s (two sonication cycles, each lasting 30 s, with a 30-second break between them). Samples were left stirring for 3 h and the excess of organic solvent was removed by rotavapor. NPs were collected and purified by centrifugation (10,733 g × 40 min). The final product was resuspended in 1 mL of MilliQ water (mQw) and the unloaded drug was removed through a mild centrifugation (10,733 g × 1 min). Fluorescently labelled NPs were obtained in the same way, by also adding 2% w/w of rhodamine B-labeled PLGA (50:50, 10–30 kDa; Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) to the final PLGA solution in the organic phase.

As previously described18, NPs were characterized through dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis in order to estimate their hydrodynamic diameter (DH). Measurements were performed on an ALV apparatus equipped with ALV-5000/EPP Correlator, special optical fiber detector and ALV/CGS-3 Compact goniometer. The light source is He–Ne laser (l = 633 nm), 22 mW output power. Hydrodynamic size and related distribution were determined by a cumulant fitting of the auto-correlation function. For these analyses, the stock NP dispersion was diluted 1:100 (v/v) in water and measured at 25 °C. In the specific case of FM19G11-loaded NPs, obtained size distribution showed an averaged hydrodynamic diameter (< DH>) of 227 ± 7 nm.

FM19G11 content was determined by HPLC analysis. The NPs were disassembled by mixing the NP suspension with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at a volume ratio of 1/10. Each sample was injected (20 µL) in a C18 reversed-phase chromatography column at 30 °C with a flow rate of 0.5 mL min−1 in a solution of acetonitrile-water with 59:41 ratio. The FM19G11 peak was detected after ~ 7 min. The detection wavelength was set at 247 nm. Calibration curves were previously obtained with different FM19G11 concentrations (0.25, 0.1, 0.04, 0.02, 0.01, 0.004, 0.002 mg mL−1). Encapsulation Efficiency (EE%) values associated to each batch of NPs were calculated according to the following equations: EE% = 100*(Weight of Drug Encapsulated in Polymer Nanoparticles)/(Weight of Drug Used in Encapsulation Method). The obtained value of EE% was 51.5 ± 9.8% corresponding to 0.56 ± 0.02 mM of FM19G11.

The analyses were performed on a JASCO® HPLC equipped with: 2057 autosampler; RI-2031 refraction index detector; UV-/Vis detector, CO-2060 plus oven column; PU-2080 pump; MD-2018 photodiode array PDA detector; C18 column (2.7 mm particle size) 150 mmx4.6 mm (length x diameter). Evaluation of the drug concentration was done using the UV-/Vis detector.

Culture of EpSPCs and FM19G11 treatment

The epSPCs were isolated from whole spinal cords of G93A-SOD1 and age-matched B6SJL mice at week 8, 12 and 18 of age. After removal of the overlying meninges and blood vessels, spinal cords were cut into small pieces, dissociated with 0.05% collagenase I (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Foster City, CA, USA) for 15 min at 37 °C, and then processed to produce epSPC neurospheres as previously described6,18. At day 20 (passage 3), epSPCs from G93A-SOD1 and B6SJL mice were cultured at a density of 105 cells in proliferative medium consisted of Dulbecco’s modified essential medium (DMEM Thermo Fischer Scientific) supplemented with F12 (Thermo Fischer Scientific), 50 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (EGF; Thermo Fischer Scientific), 10 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF; Thermo Fischer Scientific), 30% glucose, 7.5% Na bicarbonate (Thermo Fischer Scientific), 100 mM l-glutamine (Merck KGaA), 2 mg/ml heparin (2 mg/ml), bovine serum albumin (BSA; Thermo Fischer Scientific), 1 M HEPES (Thermo Fischer Scientific) and 10% hormone mix (DMEM/F12, 30% glucose, 7.5% Na bicarbonate, 1 M HEPES, putrescine 9.6 ng/ml, insulin 0.025 mg/ml, progesterone 6.3 ng/ml and Na selenite 5.2 ng/ml. Putrescine, insulin, progesterone and Na selenite are all from Merck KGaA.

At day 21, cells were cultured in proliferative medium under different conditions for 72 h: (i) basal control conditions, and (ii) treatment with FM19G11-loaded NPs (500 nM FM19G11). This concentration was previously identified as optimal in our earlier studies7,8, where it effectively modulated both epSPC and muscle cell proliferation, differentiation and energetic status.

For labelling metabolomics experiment, epSPCs were cultured for 48 h in the proliferative medium supplemented with 3 g/L of [U-13C6] glucose (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Tewksbury, MA, USA).

Immunocytochemistry and quantification of epSPC-neurospheres cultures

Before the fixation, cells were washed with PBS for three times and then were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma) in PBS pH 7.4 for 15 min at room temperature (RT). Permeabilization and blocking were performed using 0.2% Triton X-100 (Carlo Erba Reagents, Milan, Italy) and 10% Normal Goat Serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in PBS for 1 h at RT. The cells were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the mouse anti-nestin antibody (1:200, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), mouse anti-Tubulin βIII (1:200 Merck KGaA) and rabbit anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (1:300 Dako Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Immunopositivity was revealed with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat ant-rabbit IgG (1:500, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated goat anti-mouse (1:500, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cell nuclei were stained with 1 µg/mL 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; 1:1000; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Images were acquired using a confocal microscopy (TCS SP8 AOBS, Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany, or Nikon D-Eclipse C1, Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and processed with Fiji-ImageJ software (version 2.3.0/1.53q). GFAP staining intensities was measured using the Fiji-ImageJ (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD) in five randomly selected fields per coverslip (8 coverslips per culture, 6 cultures for each animal group) Staining intensity was quantified using the Corrected Total Cell Fluorescence (CTCF), calculated as: CTCF = Integrated Density−(Area of selected cell×Mean fluorescence of background readings). This method accounts for the area of the neurospheres, allowing correction for potential size differences. Integrated Density was used instead of simple fluorescence values, as it represents the sum of the fluorescence contribution of each pixel within the selection, weighted by its area. This approach reduces the influence of a few highly fluorescent pixels, which is not possible using a mean intensity measurement, enabling a more accurate assessment of the number of positive cells. The number of NPs was quantified in three separate cultures per group, with three randomly selected images acquired from each. The immunofluorescence quantification was performed in a blinded manner to minimize potential bias.

Metabolite extraction from epSPCs

For the comparison of metabolomes between ALS mice and controls, epSPCs were isolated from six G93A-SOD1 mice and six age-matched controls at 8 or 12 weeks of age, and from twelve G93A-SOD1 mice and twelve age-matched controls at 18 weeks of age. To assess the effects of FM19G11 treatment, epSPCs from five G93A-SOD1 mice and five age-matched controls at each timepoint were used to compare treated versus untreated G93A-SOD1 epSPCs and control epSPCs.

Cells were collected by centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 7 min at 4 °C. Cell pellets were washed with a solution of NaCl 0.9%, quenched with an ice-cold solution of 70:30 acetonitrile: water and placed at −80 °C for 30 min. Samples were then sonicated 5 s for 5 pulses at 70% power four times (the sonicator is a HD 2070 from Bandelin Sonoplus equipped with a MS73 probe) and then centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 min at 4˚C. Supernatant aqueous phases were collected in a glass insert and dried in a centrifugal vacuum concentrator (Concentrator plus/Vacufuge plus, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) at 30 °C for about 2.5 h.

LC-MS analyses for metabolomics experiments

Dried samples were resuspended with 150 µL H2O and then analyzed in a UHPLC-QTOF mass spectrometer. LC separation was performed using an Agilent 1290 Infinity UHPLC system and an InfinityLab Poroshell 120 PFP column (2.1 × 100 mm, 2.7 μm; Agilent Technologies). Mobile phase A was water with 0.1% formic acid. Mobile phase B was acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid. The injection volume was 15 µL and LC gradient conditions were: 0 min: 100% A; 2 min: 100% A; 4 min: 99% A; 10 min: 98% A; 11 min: 70% A; 15 min: 70% A; 16 min: 100% A with 5 min of post-run. The flow rate was 0.2 mL/min and the column temperature was 35 °C. MS detection was performed using an Agilent 6550 iFunnel Q-TOF mass spectrometer with a Dual JetStream source, operating in negative ionization mode. MS parameters were the following: gas temperature at 285 °C; gas flow: 14 L/min; nebulizer pressure: 45 psig; sheath gas temperature at 330 °C; sheath gas flow: 12 L/min; VCap: 3700 V; Fragmentor: 175 V; Skimmer: 65 V; Octopole RF: 750 V. Active reference mass correction was done through a second nebulizer using masses with m/z: 112.9855 and 1033.9881. Data were acquired from m/z 60–1050, as described in19.

Metabolomics data and statistical analysis

Data analysis and isotopic natural abundance correction were performed with MassHunter ProFinder and MassHunter VistaFlux software (version 10.0.2) (Agilent Technologies). Data pre-processing was performed using the Batch Targeted Feature Extraction algorithm and Agile 2 algorithm for semi-targeted experiments, and using the Batch Isotopologue Extraction algorithm for labelling data preprocessing. The software attributes identities to metabolites by inquiring an in-house compound database, which is built with Agilent PCDL Manager (version B.08.00) based on the metabolite formula and its corresponding retention time with a score > 7520. Peak areas obtained were normalized for protein content for each sample. Statistical analyses were performed using MetaboAnalyst 5.0 (https://www.metaboanalyst.ca/)21. Data were subjected to log10 transformation and pareto scaling.

Non T-test or One-way ANOVA (FDR adjusted p-value p < 0.05) were used as statistical test and data visualization performed through hierarchical clustering heatmaps. The clustering method used is Ward’s method with Euclidean distance. Principal component analysis (PCA) was displayed as score plots of the first two components. Enrichment analysis was performed using Over-Representation Analysis against a metabolite set library from SMPDB22, involving 99 metabolite sets, to identify over-represented metabolite sets based on the hypergeometric test. To minimize bias, all samples were randomized during processing and data acquisition.

mRNA real-time PCR

RNA was extracted from epSPCs using TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Then, it was reverse transcribed using SuperScript Vilo cDNA Synthesis kit. cDNA equal to 20 ng of total RNA was amplified by qPCR in duplicate in a ViiA7 qPCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific), using the Fast Advance Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific), assembled with primer and probe sets for VEGF-A and GFAP genes (IDs: Mm0043736_m1 and Mm01253033_m1 respectively) and one housekeeping gene, 18s rRNA (ID: 4333760 F) (Thermo Fisher Scientific). 18s was stably expressed in G93A-SOD1 and B6SJL samples. Relative expression of genes in each group was calculated using the 2−ΔCt formula.

Functional network construction

MetaboAnalyst 6.0 Network Analysis was used to create the metabolite network. The prediction of the metabolite targets was performed according to KEGG IDs (Minoru Kanehisa, Miho Furumichi, Yoko Sato, Yuriko Matsuura, Mari Ishiguro-Watanabe, KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world, Nucleic Acids Research, Volume 53, Issue D1, 6 January 2025, Pages D672–D67723, CytoScape 3.10.3 (https://cytoscape.org/) displayed the nodes, selected and predictive targets metabolites, and the interactions among them.

Statistical analysis

The non-Gaussian distributed data, verified via Shapiro–Wilk test, were analysed either with a Mann-Whitney test for the comparison of two groups or a Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparison tests for the comparisons among multiple groups.

Results

G93A-SOD1 epSPCs exhibit a reactive glial phenotype characterized by increased GFAP expression

To better understand whether disease progression in ALS affects the stemness and differentiation potential of epSPCs, we evaluated their immunoreactivity for neural progenitor markers. We assessed the immunoreactivity of epSPCs, isolated from G93A-SOD1 and B6SJL control mice at different stages of disease progression, for neural progenitor markers (Fig. 2). Cell phenotypes were identified by immunoreactivity for anti-nestin, anti-β-tubulin III, and anti-GFAP, indicating neural stem cells, neuronal progenitors, and glial progenitors, respectively. G93A-SOD1 epSPC-generated neurospheres exhibited a reactive glial phenotype, as shown by GFAP immunoreactivity that was higher than in cells from age-matched control animals. This increase was statistically significant at 12 weeks (p < 0.05) and 18 weeks (p < 0.01, Fig. 2). No significant differences were observed between the groups for nestin and β-tubulin III immunoreactivity (Supplemental Fig. 1), consistent with our previous work6. In both our previous study and the present one, neurosphere size and expression of pluripotency markers did not differ between G93A-SOD1 and control epSPCs. The main differences were observed in differentiation: G93A-SOD1 epSPCs from late-stage animals showed enhanced proliferation, a higher proportion of neurons, and the generation of astrocytes with strong GFAP immunoreactivity6. These findings indicate that while the stem cell properties of epSPCs remain largely intact, their differentiation potential is altered in the context of ALS, with a skewing toward reactive glial phenotypes and increased neuronal output.

Characterization of neurospheres of epSPCs derived from control and G93A-SOD1 mice. A, B, C left panels representative photomicrographs of neurospheres formed from epSPCs of B6SJL and G93A-SOD1 mice at weeks 8 (A), 12 (B) and 18 (C) of age cultured for 25 days (passage 3). Confocal microscopy with double-staining for GFAP (red), Nestin (green) and DAPI (blue), and GFAP (red), β-tubulin III (cyan) and DAPI (blue), scale bar = 30 μm. A, B, C right panels Quantification of GFAP immunoreactivity in neurospheres of epSPCs obtained from B6SJL (red histogram) and G93A-SOD1 (green histogram) mice at week 8 (A), 12 (B), 18 (C) of age. Data information: data are expressed in arbitrary unit (AU) as mean of the percentage of GFAP positive cells in 5 randomly selected fields per coverslip (8 coverslips per culture, 6 cultures for each animal group). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Mann-Whitney test.

Altered metabolite patterns in epSPCs from G93A-SOD1 mice

To explore whether disease progression is also associated with metabolic alterations in epSPCs, we performed a metabolomics profiling followed by multivariate and univariate analyses. the principal component analysis (PCA) of metabolomics data (Fig. 3), revealed that G93A-SOD1 and control epSPCs formed two distinct clusters, indicating a different behaviour between G93A-SOD1 and B6SJL control samples. Notably, these clusters remained distinct across all disease stages.

Principal component analyses on metabolomics data set between control and G93A-SOD1 epSPCs. PCA score plots between the first two components of the metabolome in B6SJL (red) and G93A-SOD1 (green) epSPCs at weeks 8, 12 (N = 6 for the two groups) and 18 (N = 12) of age. The explained variances are shown in brackets.

Subsequently, we identified the statistically different metabolites between the two conditions for each time point analyzed (Fig. 4). Clustering analysis confirmed the evident distinction between G93A-SOD1 and control epSPCs as shown in heatmaps of statistically significant metabolites between the two conditions. The most significant differences (63 differentially expressed metabolites) were identified at 12 weeks, which represent an intermediate disease stage (Fig. 4B), and continued to be pronounced (50 differentially expressed metabolites) even at 18 weeks, the most advanced disease stage (Fig. 4C). In contrast, at the early stage of disease (8 weeks), fewer differences were observed (35 metabolites) (Fig. 4A). These findings indicate that metabolic alterations in epSPCs emerge early and become progressively more pronounced with disease progression, suggesting a potential contribution to the pathological microenvironment in ALS.

Metabolic characterization of control and G93A-SOD1 epSPCs. A, B, C left panels Hierarchical clustering analyses shown as heatmaps of the differential expressed metabolites between G93A-SOD1 and B6SJL epSPCs at weeks 8 (A), 12 (B) (N = 6 for the two groups) and 18 (C) (N = 12) of age. Colours represent different levels that increase from blue to red. A, B, C right panels Pathway enrichment analyses of the differential expressed metabolites in epSPCs. Colours from red to orange indicate p-values. The dimension of the circles indicates the enrichment ratio. D, E upper panels Hierarchical cluster analysis of metabolites abundances in B6SJL (D) and G93A-SOD1 (E) epSPCs, highlighting the temporal evolution of the metabolic profile of each genotype. Colours represent different levels that increase from blue to red. D, E bottom panels Pathway enrichment analyses of the significant metabolites affected by the age of B6SJL epSPCs (D) and G93A-SOD1 epSPCs (E). Colours from red to orange indicate p-values. The dimension of the circles indicates the enrichment ratio.

To further investigate the affected metabolic pathways, we performed enrichment analysis using the small molecule pathway database (SMPDB) (Fig. 4, right panels). At week 8, arginine and proline, glutamate, aspartate, glycine and serine, phenylalanine and tyrosine metabolisms, urea cycle, ammonia recycling, purine, biotin and phenylacetate metabolisms and phosphatidylethanolamine biosynthesis pathways were significantly altered in ALS compared to control cells (Fig. 4A). At weeks 12, the Warburg effect, pentose phosphate pathway, glycine and serine, glutathione, glutamate, methionine, alanine, phenylalanine and tyrosine, arginine and proline, taurine and hypotaurine, and aspartate metabolisms, ammonia recycling, urea cycle, glycerol phosphate shuttle, gluconeogenesis, glucose-alanine cycle and glycolysis pathways were significantly altered in ALS compared to control cells (Fig. 4B). At week 18, the ammonia recycling, Warburg effect, urea cycle, glycine and serine, glutamate, aspartate, arginine and proline, methionine, purine, glutathione, betaine, alanine, phenylalanine and tyrosine, amino sugar, cysteine, butyrate, histidine, selenoamino acid, nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolisms, citric acid cycle, pentose phosphate pathway, glucose-alanine cycle, cardiolipin biosynthesis, mitochondrial electron transport chain and transfer of acetyl groups into the mitochondria pathways were significantly altered in ALS compared to control cells (Fig. 4C).

To first establish the temporal evolution of the metabolic profile in each genotype, we analyzed B6SJL and G93A-SOD1 samples separately. In B6SJL (Supplementary Fig. 2 A, left panel), the PCA score plot showed a clear separation of samples across 8, 12, and 18 weeks, with 12- and 18-week samples clustering more closely, indicating a progressive and convergent metabolic shift. The corresponding heatmap of individual samples (Supplementary Fig. 2 A, right panel) and the averaged heatmap (Fig. 4D, upper panel) both highlighted a global time-dependent decrease in metabolite abundance, with higher levels at 8 weeks that declined progressively at 12 and 18 weeks. Pathway enrichment analysis of the 67 statistically significant metabolites (Fig. 4D, bottom panel) revealed strong overrepresentation of glycine and serine metabolism, the urea cycle, arginine and proline metabolism, aspartate metabolism, and glutamate metabolism, as well as energy-related pathways such as the Warburg effect and the citric acid cycle. Additional enrichment was observed in amino acid biosynthesis (methionine, phenylalanine, tyrosine, tryptophan) and nucleotide metabolism. These findings indicate that, in control samples, time-dependent metabolic changes primarily affect amino acid metabolism and energy-related pathways. The Venn diagram further supported this conclusion by highlighting metabolites that were consistently decreased at both 12 and 18 weeks (Supplementary Fig. 2 A, bottom panel). These included oleic acid, quinolinic acid, oxidized glutathione, L-phenylalanine, glutaric acid, N-acetylglucosamine 6-phosphate, malondialdehyde, arachidonic acid, L-lactic acid, uridine 5′-diphosphoglucuronic acid, and picolinate, suggesting long-term suppression of lipid metabolism, oxidative stress-related pathways, and intermediates of the kynurenine and glucuronic acid pathways. In addition, a broader set of metabolites were downregulated during this time course, including cytidine, L-threonine, S-adenosylmethioninamine, adenosine, folate, D-glucose 6-phosphate, sedoheptulose 7-phosphate, succinic acid, L-lysine, citrulline, S-adenosyl-L-methionine, AMP, glutathione, ornithine, UDP-glucuronate, UMP, L-arginine, kynurenate, glucosamine 6-phosphate, methylglyoxal, xanthine, acetic acid, N1-acetylspermine, and acetoacetic acid. Many of these are involved in amino acid metabolism, nucleotide metabolism, and energy-related pathways, further supporting the notion of a time-dependent global metabolic downshift in control neurospheres.

In G93A-SOD1 epSPCs a distinct temporal pattern was observed (Supplementary Fig. 2B). The PCA confirmed separation of metabolic profiles across time points, consistent with the non-averaged heatmap from ANOVA analysis (Supplementary Fig. 2B, left and right panels). Clustering of averaged metabolites (Fig. 4E, top panel) further revealed that, unlike controls, some metabolites did not follow a uniform decreasing trend. Instead, a subset — including D-isocitric acid, L-dehydro-ascorbate, uric acid, L-glutamate, pyrophosphate, oxaloacetic acid, ADP, oxoglutaric acid, citric acid, L-glutamic acid 5-phosphate, uridine, fructose 1,6-bisphosphate, cyclic AMP, xanthosine, and riboflavin — showed an opposite trajectory, persisting or increasing at later time points. The Venn diagram (Supplementary Fig. 2B, bottom panel) further illustrated overlapping and unique sets of altered metabolites between 12 and 18 weeks, consistent with a disease-related metabolic reprogramming distinct from the time-dependent decline observed in controls. Pathway enrichment analysis of the 66 statistically significant metabolites (Fig. 4E, bottom panel) revealed strong enrichment of glycine and serine metabolism, arginine and proline metabolism, the urea cycle, the Warburg effect, alanine metabolism, aspartate metabolism, glutamate metabolism, and methionine metabolism, with additional overrepresentation in pathways linked to nucleotide metabolism, gluconeogenesis, the pentose phosphate pathway, and pyruvate metabolism. Together, these results indicate that G93A-SOD1 neurospheres undergo a distinct metabolic reorganization over time, characterized by sustained activation of amino acid and energy-related pathways, in contrast to the global time-dependent metabolic downshift observed in controls.

Altered glucose metabolism in epSPCs from G93A-SOD1 mice at advanced disease stage

It is widely known that glucose is a key metabolite implicated in ALS24, and the quantification of its utilization is essential to understand the cellular and molecular mechanisms by which this metabolite participates in the metabolic rewiring that influences the survival of motor neurons. Among the global metabolic alterations identified, several pathways were found to converge on glycolysis and glucose metabolism, which represent central hubs in cellular energy homeostasis and are strongly implicated in ALS pathophysiology.

Based on this, we selected glycolysis as a representative pathway for further investigation, given its direct relevance to energy production, redox balance, and the regulation of stem cell fate. This focused analysis allowed us to better connect the global metabolic changes to specific alterations in a pathway critically involved in both neuronal and stem cell function.

Glucose metabolism can be steered towards energy-producing and biosynthetic pathways based on cellular needs. The glycolysis is the main energetic pathway and it starts with the phosphorylation of glucose to glucose 6-phosphate (G6P) and its conversion into fructose 6-phosphate (F6P) producing pyruvate (Pyr) that enters in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. However, glucose can also be directed towards glycogen biosynthesis or pentose phosphate pathway (PPP).

To evaluate glucose utilization in epSPCs isolated from 18 weeks-old mice, we used U13C6-labelled glucose (m + 6 Glc) (Fig. 5A). In G93A-SOD1 epSPCs, we observed a slight but significant decrease in the labelling of uridine diphosphate glucose (UDP-Glc), which is derived from G6P through its conversion into G1P and implicated in glycogen biosynthesis (p < 0.01). Similarly, ribose 5-phosphate (R5P) involved in the PPP obtained from G6P, showed reduced labelling in epSPCs from G93A-ALS compared to control mice (p < 0.01).

A Glucose metabolism in control and G93A-SOD1 epSPCs. Schematic representations and atomic transition map of relative isotope labelling enrichment of metabolites from [U-13C6] glucose in B6SJL (white) and G93A-SOD1 (grey) epSPCs at week 18. Filled blue circles indicate 13 C enrichment. Data are expressed as relative to control (N = 5 for each group). B Glutamine metabolism in control and G93A-SOD1 epSPCs. Schematic representations and atomic transition map of relative isotope labelling enrichment of metabolites from [U-13C5] glutamine in B6SJL (white) and G93A-SOD1 (grey) epSPCs at week 18. Pink-filled circles indicate 13 C enrichment. Data are expressed as relative to control (N = 5 for each group). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.005.

The side reaction of F6P to glucosamine-6-phosphate (GlcN6P) and uridine diphosphate N acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc), implicated in the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway, produced a significant reduction of the labelling levels of UDP- GlcNAc both the m + 6 form and the full m + 8 (the remaining marked acetyl group (Ac) derived from downstream glucose metabolism), in G93A-ALS compared to control epSPCs (p < 0.01). We also found that m + 3 lactate (Lac), derived from Pyr through anaerobic glycolysis, was significantly decreased in G93A-SOD1 epSPCs (p < 0.01, Fig. 5A), indicating reduced glucose oxidation via glycolysis. Consequently, Pyr that enters into the TCA cycle and is converted to acetyl-CoA was also affected. Citrate (Cit) m + 2 levels were significantly reduced in G93A-SOD1 epSPCs (p < 0.01), as were downstream TCA cycle intermediates m + 2 malate (Mal) and m + 2 fumarate (Fum) indicating impaired glucose oxidation via TCA (p < 0.01).

Interestingly, an alternative route of pyruvate entry into the TCA cycle via the anaplerotic enzyme pyruvate carboxylase, which converts Pyr into oxaloacetate (OAA) appeared upregulated in G93A-SOD1 epSPCs. This was reflected by increased labelling of m + 3 malate through the anticlockwise TCA cycle in G93A-SOD1 epSPCs compared to controls (p < 0.01). As an alternative to TCA cycle, the acetyl-CoA can enter in the mevalonate pathway producing acetoacetyl-CoA (AcAc) and mevalonate (Mev) whose marked levels were significantly increase in G93A-SOD1 epSPCs (p < 0.01).

To further evaluate anaplerotic contributions to the TCA cycle, we performed U-¹³C5-glutamine tracing in epSPCs from 18-week-old mice (Fig. 5B). In contrast to the reduced incorporation of glucose-derived carbons, glutamine labeling revealed increased entry of this substrate into the TCA cycle in G93A-SOD1 epSPCs. Specifically, we detected higher enrichment of m + 4 citrate, m + 4 malate, and m + 4 aspartate, consistent with enhanced anaplerotic flux through α-ketoglutarate. Moreover, the labeling of m + 5 glutamate and m + 5 glutathione was significantly increased, together with elevated levels of oxidized glutathione (GSSG) and pyroglutamate, indicating that glutamine was preferentially fueling both bioenergetic and redox-related pathways. These findings suggest that G93A-SOD1 epSPCs undergo a metabolic rewiring characterized by reduced glucose oxidation and a compensatory reliance on glutamine anaplerosis to sustain TCA cycle activity and antioxidant defense.

Treatment with FM19G11-loaded NPs restores the levels of metabolites involved in glucose-, glutamate-, and glutathione-related pathways in G93A-SOD1 epSPCs

To evaluate whether the altered transcriptional and metabolic programs observed in G93A-SOD1 epSPCs could be modulated by a therapeutic intervention, we investigated the effects of FM19G11 delivered through nanoparticles. Upon 72 h of treatment, FM19G11-loaded NPs localized in the nucleus and cytoplasm of epSPCs (Fig. 6A). As shown in Fig. 6B, we observed increased levels of VEGF gene, a directly FM19G11 target, in G93A-SOD1 compared to control cells at weeks 8, 12, 18 at basal condition (p < 0.05). After treatment, with NPs-FM19G11, this expression significantly decreased in treated G93A-SOD1 epSPCs compared to untreated cells reaching levels similar to those of control cells (Fig. 6B p < 0.05). In line with the immunofluorescence analysis, GFAP expression levels were elevated in G93A-SOD1 cells compared to controls at week 12, and significantly increased at week 18 under basal conditions (Fig. 6B, p < 0.05). Treatment with FM19G11-loaded NPs significantly reduced GFAP expression in G93A-SOD1 epSPCs compared to untreated cells, restoring expression levels to those comparable with control cells (Fig. 6B, p < 0.05). These results support that the treatment impacts transcriptional programs by directly targeting VEGF and lowering GFAP levels associated with glial differentiation.

Metabolic characterization of G93A-SOD1 epSPCs after FM19G11-loaded nanovectors. A Confocal orthogonal images indicated double staining of nestin (green), nanovectors (red) and DAPI (blue) of treated G93A-SOD1 and B6SJL epSPCs. 126x magnification, scale bar 10 µm. (2 coverslips per culture, 10 randomly selected fields, 3 cultures for each animal group). B Real-time RT PCR of VEGF and GFAP gene expression levels in epSPCs from B6SJL (light violet), untreated G93A-SOD1 (red) and G93A-SOD1 treated cells with FM19G11-loaded nanovectors (green) at 8, 12, 18 weeks (N = 5 for each group). Relative expression data are presented as mean ± SD. The Kruskal-Wallis analysis with Dunn’ was used to compare among untreated and treated epSPCs G93A-SOD1 and B6SJL cells. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. C, D, E Hierarchical clustering analyses shown as heatmaps of the differential metabolites between untreated and treated G93A-SOD1 and B6SJL epSPCs at weeks 8 (C), 12 (D) and 18 (E) of age (N = 5 for each group). Colours represent different levels that increase from blue to red.

Metabolomics analyses were performed in B6SJL control epSPCs, and in untreated and NPs-FM19G11-treated G93A-SOD-1 epSPCs, including cells isolated at the three disease stages (i.e., 8, 12 and 18 weeks) (Fig. 6C-E). Hierarchical clustering analyses of the epSPCs isolated at 8 and 12 weeks revealed a metabolic signature that was more similar between control and untreated G93A-SOD1 cells compared to NPs-FM19G11-treated G93A-SOD1 cells (Fig. 6C, D). Notably, we observed a general downregulation of metabolites in treated cells, with a higher number of differentially expressed metabolites at 12 weeks compared to 8 weeks. These findings suggest that the metabolic rewiring induced by the NPs-FM19G11 treatment begins during early disease stages. However, at these stages, the treatment was not able to fully modulate a metabolic signature similar to that of the control cells.

Conversely, a hierarchical clustering analysis conducted on week 18 data ((Fig. 6E) identified a primary cluster that differentiated the untreated G93A-SOD1 condition from both the control and the treated conditions, which were found to belong to the same sub-cluster. These findings indicated that, after NPs-FM19G11 administration, the metabolic profile of epSPCs from G93A-SOD1 mice at the symptomatic disease stage was more closely regulate that of the control group compared to untreated G93A-SOD1 cells. In order to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the observed rewiring, the subsequent analysis was focused on specific metabolites involved in glucose, glutamate and glutathione metabolism.

As shown in Fig. 7, we observed increased levels of glucose-related metabolites (D-glucose, lactic acid, citric acid and mevalonate) in G93A-SOD1 compared to control epSPCs at basal condition with a statistically significant increase only for mevalonate (Fig. 7 top panel, p < 0.05). After treatment with NPs-FM19G11, these metabolites were significantly reduced in treated G93A-SOD1 epSPCs compared to untreated cells, reaching levels similar to those of control cells (Fig. 7 top panel p < 0.001). In addition, metabolomics analysis showed an increased levels of glutamate, glutamine, glycine, aspartate and DMG in G93A-SOD1 compared to control cells (Fig. 7 middle panel, p < 0.05). These values underwent a decrease following NPs-FM19G11 treatment in G93A-SOD1 cells (Fig. 7 middle panel, p < 0.05). Moreover, increased levels of pyroglutamate, adenosyl homocysteine, GSSG and GSH metabolites were observed in G93A-SOD1 compared to control cells (Fig. 7 bottom panel p < 0.05). After NPs-FM19G11 treatment, these metabolites levels were shifted toward control-like profile (Fig. 7 bottom panel, p < 0.01). Of note, the analysis considered the most significant pathways and their potential translation into an in vivo model for therapeutic applications. Glycolysis remains a central pathway of interest, as reflected by the normalization of key glucose-related metabolites following FM19G11 treatment. Moreover, other pathways crucial to ALS pathogenesis, including glutamate and glutathione metabolism, also normalized after treatment, highlighting the broad and promising metabolic impact of FM19G11 in the ALS context.

Glucose, glutamate and glutathione-related pathway metabolites in epSPCs ALS, and B6SJL cells. Levels of the glucose, glutamate, and glutathione-related pathway metabolites in epSPCs from B6SJL (pink), untreated G93A-SOD1 (yellow) and G93A-SOD1 treated cells with FM19G11-loaded nanovectors (light blue) at 18 weeks (N = 5 for each group). Data information: Data are expressed as relative to control. The Kruskal-Wallis analysis was used to compare each metabolite among untreated and treated epSPCs ALS and B6SJL cells. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

A functional network was constructed using MetaboAnalyst 6.0 annotation terms of metabolites to provide a comprehensive visualization of the relationships among glucose-related (D-glucose, lactic acid, citric acid, and mevalonate), glutamate-related (glutamate, glutamine, glycine, aspartate, and DMG), and glutathione-related (pyroglutamate, adenosyl homocysteine, GSSG, and GSH) metabolites, as well as their predicted downstream metabolites (Fig. 8). This network approach was chosen to integrate complex metabolic data and highlight potential mechanistic connections, allowing us to identify functional relationships that may underlie the effects of NPs-FM19G11 treatment. By mapping these interactions, we were able to visualize how alterations in key metabolic pathways are linked to each other and to potential molecular targets, providing insight into the coordinated metabolic response induced by the treatment.

Discussion

In this study we assessed the metabolome of epSPCs isolated from the spinal cord of G93A-SOD1 mice to identify metabolites that could potentially act as novel therapeutic targets for ALS treatment. We also investigated the in vitro effects of a novel NP-based therapy with FM19G11, a HIF modulator known to affect the global metabolism8,10. Specifically, we evaluated whether NPs-FM19G11 could restore the altered metabolism associated with ALS.

Metabolomic analysis revealed significant alterations of different metabolic pathways in ALS epSPCs isolated from mice at different disease stages compared to control cells. The identified pathways, and their metabolites, were known to be involved in ALS pathological mechanisms25, thus representing possible new targets for innovative therapeutics.

One of the most affected pathways was glucose metabolism, which includes metabolites such as: D-glucose, lactic acid, citric acid, and mevalonate metabolites, showing significant alterations in G93A-SOD1 compared to control cells. This phenomenon was more evident at the later disease stage and aligned with findings by McDonald and colleagues26, who demonstrated altered glucose homeostasis and uptake in G93A-SOD1 mice, attributed to the hormonal regulation of glucose concentrations, which may contribute to disease progression. Importantly, glycolysis represents a central hub of cellular energy metabolism, tightly linked to ATP production, redox balance, and biosynthetic processes. Its dysregulation not only reflects impaired energy homeostasis but may also directly influence stem cell fate, proliferation, and differentiation, further highlighting its crucial role in ALS pathophysiology. Considerable evidence indicates that cerebral glucose uptake is impaired in ALS patients13. Moreover, recent studies on glucose metabolism have identified region-specific hypo- and hypermetabolic patterns in ALS brain, which are different according to the patients’ genetic background. Indeed, patients with SOD1 mutations, C9ORF72 expansions, and sporadic ALS exhibit distinct glucose metabolic profiles, potentially reflecting different pathological involvement across cortical regions27,28. Dysregulated glucose metabolism is well reported in humans and animal models of ALS13,29, with increased production of lactate, a hallmark of the Warburg effect25, emerging as an early disease event. Notably, glucose metabolic imbalance contributes to increase the oxidative stress, impairing ATP production, thus providing a hint for the exacerbation of neurodegeneration25.

Given the importance of glucose metabolism in ALS, targeting metabolic pathways influenced by the Warburg effect might offer a promising therapeutic strategy. Enhancing mitochondrial function, modulating glycolysis and restoring lactate metabolism could improve energy homeostasis. Building on this evidence, we treated G93A-SOD1 cells with FM19G11 to investigate the restorative effects of this HIF on altered glucose metabolism. Consistently with previous studies8,9 FM19G11-loaded NP treatment in G93A-SOD1 epSPCs led to a significant reduction of several metabolites, including D-glucose, lactic acid, citric acid, and mevalonate, shifting them to levels comparable to those of control cells. According with these data, new therapeutic approaches for ALS could focus on targeting glucose-related metabolism to enhance cellular bioenergetics, which might hold the promise for symptoms’ relief or slowing disease progression. The stimulation of epSPC differentiation and release of neurotrophic factors in the spinal cord may represent a strategy to counteract, or even reverse, motor degeneration in ALS, and in other motor neuron diseases.

In addition to glucose metabolism, metabolomics analysis showed an increase of glutamate, glutamine, and glycine metabolism in epSPCs isolated from G93A-SOD1 mice compared to controls at early disease stage. It is now well-known that the levels of glutamate are altered in ALS patients14. Specifically, glutamate, a potentially neuroexcitotoxic compound, is thought to be the transmitter of the corticospinal tracts and certain spinal cord interneurons, therefore a systemic defect in its metabolism may contribute to motor neuron degeneration in ALS30,31. Glutamate toxicity is highly relevant in ALS since it may favor disease progression via multiple pathways, by directly affecting motor neurons and modulating astrocytic reactive phenotype and their secretome, thus providing paracrine signals to neighbouring cells14. Excess of glutamate at the synaptic cleft results in excessive firing of neurons, thereby increasing the influx of calcium which can be toxic to neurons32. In ALS, the glutamate metabolism excitotoxicity is a well-documented mechanism contributing to motor neuron degeneration33. Due to the central role of glutamate in ALS, experimental therapies have been investigated and developed targeting glutamate signaling pathways or aimed at enhancing glutamate transport (EAAT2) function in order to restore glutamate homeostasis34. Advances in gene therapy and small molecules able to upregulate EAAT2 expression are under investigation as potential intervention35 that could mitigate oxidative stress and excitotoxicity, reducing neuronal damage. Our functional in vitro studies displayed a significant reduction of metabolites of the glutamate-related pathway, including glutamate, glutamine, glycine, aspartate and DMG, in NPs-FM19G11-treated G93A-SOD1 epSPCs compared to untreated cells. Of note, the treatment reduced the expression of glutamate-related metabolites, suggesting its potential as a metabolome-targeting therapeutic strategy for ALS.

Furthermore, NPs-FM19G11 treatment restored the levels of glutathione-related metabolites in epSPCs from ALS mice by the treatment. Motor neuron degeneration in ALS is associated with oxidative damage. Glutathione, a key antioxidant and redox regulator, plays a crucial role in cellular defense mechanisms. Studies have shown that mutant SOD1 cell lines trigger an adaptive response, leading to the upregulation of glutathione synthesis. However, the dysregulation of the glutathione pathway, resulting from the SOD1 mutation, may contribute to the increased vulnerability of motor neurons. This pathway thus represents a promising therapeutic target15. In ALS, the glutathione cycle is often disrupted, leading to increased oxidative stress36. Pyroglutamate, a product of glutathione turnover12, may accumulate when this cycle is dysfunctional. The reduction of pyroglutamate levels after treatment could indicate improved glutathione cycle efficiency and a better oxidative stress management. Interestingly, elevated pyroglutamate levels have been associated with toxic effects37, as its accumulation may disrupt redox homeostasis and interfere with glutamate metabolism. Therefore, its reduction could reflect a restoration of metabolic balance and a decrease in oxidative stress, both crucial outcomes in neurodegenerative diseases as ALS. Moreover, the decrease in adenosyl homocysteine, which we observed in ALS cells following NPs-FM19G11 treatment, may indicate a restoration of methylation processes. Since high levels of adenosyl homocysteine are associated with dysfunctions in the methylation cycle and an accumulation of homocysteine, a phenomenon that increases oxidative stress and neuronal damage38, a reduction of these levels could lead to improved cell survival. Reduction of GSSG metabolite levels suggests a decrease in oxidative damage and an improvement in the cellular redox balance. Under normal conditions, a low concentration of GSSG relative to GSH indicates good cellular protection capacity39. In the context of ALS, a decrease in GSSG could be beneficial since it could be associated with an enhancement of the efficiency of the glutathione cycle and a better oxidative balance.

Of note, while FM19G11 modulates metabolic profiles, in some cases it shifts certain metabolites away from pathological levels without fully restoring them to control values. Because FM19G11 also promotes epSPC proliferation7, the observed changes in metabolite abundance could reflect altered growth rates or shifts in differentiation rather than a direct correction of pathological metabolism. The global decrease in metabolite levels, while seemingly counterintuitive for a proliferative state, may reflect metabolic reprogramming associated with cell cycle progression or differentiation, as shown by our molecular analysis and previous work7, rather than simple metabolite accumulation.

The more pronounced treatment effects observed at the late stage of disease may be explained by different, not mutually exclusive, mechanisms. In the early phase, compensatory responses may still counteract pathological alterations, thus masking therapeutic benefits, whereas in advanced stages these mechanisms are exhausted and disease manifestations become more stable and homogeneous, making treatment effects more evident. It is also conceivable that our approach preferentially targets molecular processes that are specifically active in the later phases of disease progression. From a translational perspective, this timing-dependent action may represent an advantage, as ALS patients generally start therapeutic interventions only once clinical symptoms are already manifest, and modeling treatment at symptomatic onset therefore provides a scenario that closely mirrors the real-world conditions of patient care.

By integrating the analysis of metabolites and their targets within a functional network, we identified several pathways affected by the NPs-FM19G11 treatment. This implies that targeting a selected group of metabolites could have a broader impact on multiple pathways, an outcome that may be particularly relevant in the context of ALS and other complex neurodegenerative diseases.

Our study has several important limitations. First, it relies exclusively on the G93A-SOD1 mouse model, which accounts for only ~ 2% of ALS cases (those associated with SOD1 mutations). Although this model is widely used and reproduces many key aspects of ALS pathology, its inability to fully capture the heterogeneity and complexity of the human disease must be acknowledged, as findings may not be directly generalizable to other ALS subtypes. Second, the study is primarily based on in vitro experiments. While these provide valuable mechanistic insights, additional in vivo studies are required to confirm the effects of FM19G11-loaded NPs on epSPC energy metabolism and, crucially, to demonstrate their capacity to promote neurogenesis. In vivo experiments will also make it possible to evaluate how the activated microenvironment of the ependymal canal in the ALS spinal cord—characterized by glial and neural cell interactions with resident epSPCs—influences treatment outcomes40,41. Notably, in our previous study we showed that epSPCs derived from SOD1-G93A mice exhibit a distinctive miRNA expression profile that is preserved in culture, suggesting that these cells retain in vitro a molecular imprint of their in vivo pathological state, which may affect their differentiation potential6. While this approach offers important mechanistic insights, it does not fully reproduce the complexity of the in vivo metabolic environment, where interactions with glial and other cell types are critical. Moreover, functional assays assessing neuroprotection and epSPC differentiation after treatment were not performed and should be included in future studies. Our work also does not address the persistence of the metabolic effects induced by FM19G11-loaded NPs, which is essential to determine whether the observed responses are transient or sustained over time. Finally, potential barriers to clinical translation—including biodistribution, safety, and manufacturing scalability—must be carefully evaluated. Expanding these analyses to additional ALS models and incorporating functional validations will therefore be essential to fully assess the therapeutic potential of our FM19G11-based nanotechnology approach across diverse ALS subgroups and phenotypes.

Nevertheless, combination of our findings with data from our previous studies7,8 allows to highlight the potential of NPs-FM19G11 treatment as a strategy to treat ALS, but also other neurological disorders, in view of the positive regulatory effects of this treatment on three relevant pathways implicated in neurodegeneration, including glucose, glutamate and glutathione-related pathways. This strategy could also promote epSPC differentiation and the release of neurotrophic factors from these cells to counteract degeneration of motor neurons, thus deserving further investigation for its translation in clinical application for ALS care.

Conclusions

Overall findings highlight the potential of FM19G11-loaded NPs to revert metabolic dysregulation in ALS epSPCs, providing a basis for innovative metabolic therapies and precision medicine approaches to counteract motor neuron degeneration in ALS and other motor neuron diseases.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available at Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15038568.

Abbreviations

- ALS:

-

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- epSPCs:

-

Ependymal stem progenitor cells

- SOD1:

-

Superoxide dismutase 1

- HIF:

-

Hypoxia-inducible factor

- PLGA:

-

Poly-lactide-co-glycolide

- NPs:

-

Nanoparticles

- DCM:

-

Dichlorometane

- DLS:

-

Dynamic light scattering

- DMSO:

-

Dimethyl sulfoxide

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- TCA:

-

Tricarboxylic acid

- PPP:

-

Pentose phosphate pathway

- EAAT2:

-

Excitatory amino acid transporter 2

References

Feldman, E. L. et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [in eng]. Lancet 400 (10360), 1363–1380 (2022).

Huang, M. et al. Variability in SOD1-associated amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: geographic patterns, clinical heterogeneity, molecular alterations, and therapeutic implications [in eng]. Transl Neurodegener. 13 (1), 28 (2024).

Taylor, J. P., Brown, R. H. & Cleveland, D. W. Decoding ALS: from genes to mechanism [in eng]. Nature 539 (7628), 197–206 (2016).

Chi, L. et al. Temporal response of neural progenitor cells to disease onset and progression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-like Transgenic mice [in eng]. Stem Cells Dev. 16 (4), 579–588 (2007).

Guan, Y. J. et al. Increased stem cell proliferation in the spinal cord of adult amyotrophic lateral sclerosis Transgenic mice [in eng]. J. Neurochem. 102 (4), 1125–1138 (2007).

Marcuzzo, S. et al. Altered MiRNA expression is associated with neuronal fate in G93A-SOD1 ependymal stem progenitor cells. Exp. Neurol. 253, 91–101 (2014).

Marcuzzo, S. et al. FM19G11-Loaded Gold Nanoparticles Enhance the Proliferation and Self-Renewal of Ependymal Stem Progenitor Cells Derived from ALS Mice [in eng]. Cells. ;8(3). (2019).

Malacarne, C. et al. FM19G11-loaded nanoparticles modulate energetic status and production of reactive oxygen species in myoblasts from ALS mice [in eng]. Biomed. Pharmacother. 173, 116380 (2024).

Rodríguez-Jimnez, F. J. et al. FM19G11 favors spinal cord injury regeneration and stem cell self-renewal by mitochondrial uncoupling and glucose metabolism induction [in eng]. Stem Cells. 30 (10), 2221–2233 (2012).

Moreno-Manzano, V. et al. FM19G11, a new hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) modulator, affects stem cell differentiation status [in eng]. J. Biol. Chem. 285 (2), 1333–1342 (2010).

Goutman, S. A. et al. Metabolomics identifies shared lipid pathways in independent amyotrophic lateral sclerosis cohorts [in eng]. Brain 145 (12), 4425–4439 (2022).

Goutman, S. A. et al. Untargeted metabolomics yields insight into ALS disease mechanisms [in eng]. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 91 (12), 1329–1338 (2020).

Tefera, T. W. et al. CNS glucose metabolism in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a therapeutic target? [in eng]. Cell. Biosci. 11 (1), 14 (2021).

Foran, E. & Trotti, D. Glutamate transporters and the excitotoxic path to motor neuron degeneration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [in eng]. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 11 (7), 1587–1602 (2009).

Tartari, S. et al. Adaptation to G93Asuperoxide dismutase 1 in a motor neuron cell line model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: the role of glutathione [in eng]. FEBS J. 276 (10), 2861–2874 (2009).

Burg, T. & Van Den Bosch, L. Abnormal energy metabolism in ALS: a key player? [in eng]. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 36 (4), 338–345 (2023).

Fawal, M. A. & Davy, A. Impact of metabolic pathways and epigenetics on neural stem cells [in eng]. Epigenet Insights. 11, 2516865718820946 (2018).

Marcuzzo, S. et al. Hind limb muscle atrophy precedes cerebral neuronal degeneration in G93A-SOD1 mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a longitudinal MRI study [in eng]. Exp. Neurol. 231 (1), 30–37 (2011).

Bonanomi, M. et al. Transcriptomics and metabolomics integration reveals Redox-Dependent metabolic rewiring in breast cancer cells [in eng]. Cancers (Basel) 13(20) (2021).

Lori, G. et al. Altered fatty acid metabolism rewires cholangiocarcinoma stemness features [in eng]. JHEP Rep. 6 (10), 101182 (2024).

Pang, Z. et al. MetaboAnalyst 5.0: narrowing the gap between Raw spectra and functional insights [in eng]. Nucleic Acids Res. 49 (W1), W388–W396 (2021).

Jewison, T. et al. SMPDB 2.0: big improvements to the small molecule pathway database [in eng]. Nucleic Acids Res. 42 (Database issue), D478–484 (2014).

Kanehisa, M. et al. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world [in eng]. Nucleic Acids Res. 53 (D1), D672–D677 (2025).

Lerskiatiphanich, T., Marallag, J. & Lee, J. D. Glucose metabolism in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: it is bitter-sweet [in eng]. Neural Regen Res. 17 (9), 1975–1977 (2022).

Maksimovic, K. et al. Evidence of metabolic dysfunction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) patients and animal models [in eng]. Biomolecules; 13(5) (2023).

McDonald, T. S. et al. Glucose clearance and uptake is increased in the SOD1 [in eng]. FASEB J. 35 (7), e21707 (2021).

De Vocht, J. et al. Differences in cerebral glucose metabolism in ALS patients with and without [in eng]. Cells 12(6) (2023).

Canosa, A. et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with SOD1 mutations shows distinct brain metabolic changes [in eng]. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 49 (7), 2242–2250 (2022).

Pascual, J. M. et al. Triheptanoin for glucose transporter type I deficiency (G1D): modulation of human ictogenesis, cerebral metabolic rate, and cognitive indices by a food supplement [in eng]. JAMA Neurol. 71 (10), 1255–1265 (2014).

Plaitakis, A. & Caroscio, J. T. Abnormal glutamate metabolism in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [in eng]. Ann. Neurol. 22 (5), 575–579 (1987).

Blasco, H. et al. The glutamate hypothesis in ALS: pathophysiology and drug development [in eng]. Curr. Med. Chem. 21 (31), 3551–3575 (2014).

Lewerenz, J. & Maher, P. Chronic glutamate toxicity in neurodegenerative Diseases-What is the evidence? [in eng]. Front. Neurosci. 9, 469 (2015).

Arnold, F. J. et al. Revisiting glutamate excitotoxicity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and Age-Related neurodegeneration [in eng]. Int. J. Mol. Sci.; 25(11), 5587 (2024).

Averill, L. A. et al. Glutamate dysregulation and glutamatergic therapeutics for PTSD: evidence from human studies [in eng]. Neurosci. Lett. 649, 147–155 (2017).

Wang, X. M. et al. Dysregulation of EAAT2 and VGLUT2 spinal glutamate transports via histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2) contributes to Paclitaxel-induced painful neuropathy [in eng]. Mol. Cancer Ther. 19 (10), 2196–2209 (2020).

Barber, S. C. & Shaw, P. J. Oxidative stress in ALS: key role in motor neuron injury and therapeutic target [in eng]. Free Radic Biol. Med. 48 (5), 629–641 (2010).

Kim, K. Glutathione in the nervous system as a potential therapeutic target to control the development and progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [in eng]. Antioxid. (Basel) 10(7), 1011 (2021).

Cunha-Oliveira, T. et al. Oxidative stress in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: pathophysiology and opportunities for Pharmacological intervention [in eng]. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 5021694 (2020).

Forman, H. J., Zhang, H. & Rinna, A. Glutathione: overview of its protective roles, measurement, and biosynthesis [in eng]. Mol. Aspects Med. 30 (1–2), 1–12 (2009).

Hamilton, L. K. et al. Cellular organization of the central Canal ependymal zone, a niche of latent neural stem cells in the adult mammalian spinal cord [in eng]. Neuroscience 164 (3), 1044–1056 (2009).

Fornai, F. et al. Plastic changes in the spinal cord in motor neuron disease [in eng]. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 670756 (2014).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by: Italian Ministry of Health (RRC); Fondazione Regionale per la Ricerca Biomedica POR FESR 2014—2020 under INTERSLA project, ID 1157625 (G.L.) CALabria HUB per Ricerca Innovativa ed Avanzata- CALHUB.RIA “Creazione di Hub delle Scienze della Vita” T4-AN-09 prog. ZRPOS2 and from the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MIUR)—ELIXIR-IT through the empowering project ELIXIRNextGenIT (Grant Code IR0000010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C., M.B., C.C., F.B.B., D.G., and S.M.; methodology, M.C., M.B., C.C., investigation, M.C., M.B., C.C., C.M., E.G., and G.F., visualization, M.C., M.B., and C.C.; funding acquisition, G.L., F.B.B., D.G and S.M.; supervision, S.B., D.P., G.L., P.M., F.B.B., D.G., and S.M.; writing – original draft, M.C., M.B., C.C., and S.M.; writing – review & editing, S.B., F.B.B., D.G., S.M.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

All animal experiments were carried out in accordance with the EU Directive 2010/63 and with the Italian law (D.L. 26/2014) on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. Transgenic G93A-SOD1 (B6SJL-Tg (SOD1*G93A)1Gur/J) [MGI: 2183719] and control B6.SJL mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories, Inc. (Wilmington, MA, USA), maintained and bred at the animal house of the Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta in compliance with institutional guidelines. The project was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute and the Italian Ministry of Health (ref. 78/2022-PR, “Malattie del motoneurone: studio di microRNA in modelli sperimentali per l’ottimizzazione della diagnosi e l’identificazione di potenziali trattamenti terapeutici”).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cattaneo, M., Bonanomi, M., Chirizzi, C. et al. Metabolic reprogramming in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis ependymal stem cells by FM19G11 nanotherapy. Sci Rep 15, 39847 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23553-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23553-3