Abstract

Evaluating WB status during normal knee flexion activities is important for optimizing surgical procedures and postoperative rehabilitation. This study aimed to clarify the effects of weight-bearing (WB) on in vivo knee kinematics and cruciate ligament forces in normal knees. Fluoroscopic imaging in the sagittal plane was used while volunteers performed squatting and active-assisted knee flexion. Tibiofemoral kinematics were measured using a two-dimensional/three-dimensional registration technique. Forces in the anterior cruciate ligament (anteromedial/posterolateral; aACL/pACL) and the posterior cruciate ligament (anterolateral/posteromedial; aPCL/pPCL) were analyzed. Anteroposterior translation (APT) of low contact points (LCPs) in WB and non-weight-bearing (NWB) conditions showed no anterior translation from extension to mid-flexion. The medial APT of LCPs in the NWB was more posterior than in WB. Medial stabilized articular surface and/or a surgical technique may help restore native knee kinematics across WB conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Previous studies have reported that patients dissatisfied with their knees after knee arthroplasty often complained during weight-bearing (WB) activities1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Therefore, evaluating the effects of WB is clinically important. Studies that investigated WB effects at mid-range flexion on the kinematics in knees after arthroplasty demonstrated that medial or lateral contact points are more posteriorly located under WB than during non-weight-bearing (NWB) conditions8,9,10,11,12,13. In anterior cruciate ligament (ACL)-sacrificed total knee arthroplasty (TKA) knees, such as those with cruciate-retaining TKA (CR-TKA), paradoxical anterior motion of the femur relative to the tibia has been observed during NWB activities14,15. Fujimoto et al. suggested this anterior motion during NWB is due to the absence of the ACL15. Additionally, Moewis et al. reported that anterior translation of the femur relative to the tibia during both NWB and WB activities may be associated with insufficient PCL tension16,17. By contrast, knees with preserved or substituted ACLs, such as unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA), bicruciate-retaining TKA (BCR-TKA), and bicruciate-substitute TKA (BCS-TKA) demonstrated reduced paradoxical anterior motion8,9,10. It is also well established that WB activities stabilize the knee joint through increased joint loading, particularly via muscle contraction16,17,18,19. However, a previous in vivo cadaveric study reported that knees in open-kinetic-chain positions were more anteriorly located than in closed-kinetic-chain positions20.

Kage et al. demonstrated that WB knee flexion angle correlates more strongly with patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) than NWB condition in TKA21. Additionally, the angular difference between NWB and WB conditions are associated with PROMs21. These findings highlight the importance of evaluating WB status during normal knee flexion activities to optimize surgical procedures and postoperative rehabilitation.

In normal knees, the ACL shortens and the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) elongates with increasing flexion22,23. Previous study has demonstrated that cruciate ligament forces in UKA, BCR-TKA, and preoperative osteoarthritis (OA) knees were higher than those in normal knees24. However, the effect of WB on cruciate ligament forces also remains unknown.

The purpose of this study was to clarify the effects of WB on in vivo knee kinematics and cruciate ligament force in normal knee during high-flexion activities. We hypothesized that normal knees maintain anteroposterior stability and cruciate ligament function due to preservation of the ACL and PCL, and therefore, WB status would not affect in vivo kinematics or cruciate ligament forces.

Results

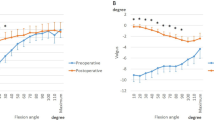

Rotational kinematic changes (Fig. 1)

The WB and NWB knees flexed from − 6.7 ± 4.9° to 154.4 ± 4.2°, and from − 1.2 ± 4.2° to 141.4 ± 3.2°, respectively. WB knees demonstrated significantly greater extension and flexion ranges than NWB knees (p < 0.01 for minimum and maximum flexion).

In WB knees, the femur displayed steep external rotation (10.0 ± 3.7°) relative to the tibia from 0° to 40° of flexion, reaching 20.4 ± 6.3° on average. By contrast, in NWB knees, the femurs displayed steep external rotation (13.4 ± 4.6°) relative to the tibia from 90° to 140° of flexion, reaching 21.4 ± 6.9° on average. WB knees exhibited more external rotation than NWB knees from 10° to 110° of flexion.

Regarding varus-valgus alignment, WB knees showed no significant angular deviation. NWB knees showed 2.4 ± 1.6° varus alignment up to 40° of flexion, followed by 2.2 ± 3.3° valgus alignment up to 140° of flexion. From 40° to 80° of flexion, NWB knees indicated a significant varus position compared to the WB knees.

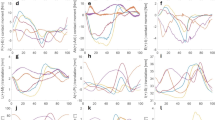

Translational kinematic changes

Anteroposterior translation (APT) of surgical epicondylar axis (SEA) (Fig. 2)

Up to 30° of flexion, the medial side of WB and NWB knees indicated 10.4 ± 5.5% and 5.6 ± 3.9% anterior movement, respectively. Beyond 30° of flexion, WB knees showed 10.2 ± 7.3% posterior movement, while NWB knees showed 17.7 ± 7.3% posterior movement from 30° to 110° of flexion, followed by 4.6 ± 5.6% anterior movement. WB knees were more anteriorly located than NWB knees up to 120° of flexion. On the lateral side, WB knees displayed a total posterior translation of 63.2 ± 11.9%. NWB knees displayed posterior translation up to 10° and beyond 50° of flexion (4.4 ± 3.0% and 54.1 ± 10.7%), with no significant movement from 10° to 50° of flexion. WB knees were more posteriorly located than NWB knees from 20° to 70° of flexion.

APT of low contact points (LCPs) (Fig. 3)

The medial side of WB indicated a total of 22.5 ± 11.3% posterior movement. While the medial side of NWB knees showed 20.7 ± 6.6% posterior movement up to 90° of flexion, followed by 4.5 ± 5.1% anterior movement. WB knees were more anteriorly located than NWB knees from 10° to 120° of flexion. At 140° of flexion, WB knees were more posteriorly located than NWB knees.

The lateral side of WB and NWB knees indicated 38.25 ± 11.6% and 44.1 ± 11.3% posterior movement with flexion, respectively. WB knees were more posteriorly located than NWB knees from 10° to 70° of flexion.

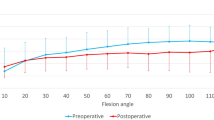

ACL forces (Fig. 4)

For both the anteromedial and posterolateral bundles of the ACL (aACL and pACL), forces decreased with flexion in both WB and NWB knees. From 0° to 10°and from 50° to 80° of flexion, the aACL force was lower in WB than in NWB. Similarly, from 0° to 30° of flexion, the pACL force in WB was lower than that in NWB.

PCL forces (Fig. 5)

For both the anterolateral and posteromedial bundles of the PCL (aPCL and pPCL), forces increased with flexion in both WB and NWB knees. At 60° of flexion, the aPCL force in WB was smaller than that in NWB. In addition, at 40° of flexion, the pPCL force in WB was also smaller than that in NWB. While from 70° to 100° of flexion, the pPCL force in WB was larger than that in NWB.

Discussion

Contrary to our hypothesis, the kinematics and cruciate ligament force of normal knee were affected by WB status.

The key findings of this study were that the APT of LCPs in WB and NWB conditions showed no anterior translation from extension to mid-flexion. However, the medial position of the LCPs in NWB knees was located more posteriorly than that in WB knees. In most of the CR-TKA knees, paradoxical anterior movement of femur relative to tibia due to ACL deficiency was observed from extension to mid-flexion14,25. By contrast, knees after ACL-function-preserving arthroplasty, such as UKA, BCR-TKA, and BCS-TKA, showed less anterior translation of the femur relative to the tibia8,9,10. This emphasizes the importance of ACL function in maintaining native anterior stability. Furthermore, several previous studies of CR-TKA and fixed-bearing PS-TKA showed that the medial contact point was located more anteriorly in NWB than in WB conditions8,9,13,14. However, in newly updated PS mobile-bearing (MB) TKA, which provides stability during the mid-flexion phase and medial-pivot TKA (MP-TKA), the medial contact point in NWB was more posteriorly located than that in WB11,26; that is similar to native knees. These facts suggest that the medial stabilized articular surface may also be important to achieve the native knee kinematics during various WB conditions. A previous study also showed that the femoral external rotation angle is smaller during extension than during flexion27. Additionally, the medial side is positioned more posteriorly in extension than in flexion27. Quadriceps muscle force increases femoral external rotation with flexion28,29 and is greater during WB than during NWB activities30. This increased quadriceps muscle force may, therefore, contribute to the observed medial APT differences.

WB knees exhibited greater external rotation than NWB knees from early flexion to high flexion. A previous cadaveric study demonstrated that active knee flexion showed more external rotation than passive knee flexion20, and that closed-kinetic-chain (CKC) knee flexion was more externally rotated than an open-kinetic-chain (OKC) knee flexion20. These findings suggest that active and CKC motion during WB activities promote pronounced femoral external rotation. Through femoral external rotation, the shear forces acting on the patella are reduced, thereby lowering the risk of anterior knee pain. Previous studies have shown that NWB knees exhibit greater external rotation than WB knees16,17,18. In our study, NWB motion was performed as active-assisted knee flexion, whereas the study showing the opposite observation investigated active knee flexion-extension. Because quadriceps force induces femoral external rotation31, it is possible that the quadriceps force during active-assisted knee flexion was weaker than that during active knee flexion-extension. The axial rotation in normal knees varies in kinematics depending on WB or NWB status. Intraoperative axial rotation resembles NWB kinematics, with no significant movement followed by femoral extreme external rotation32,33. Therefore, assessment under NWB activities may be useful for comparing intraoperative and postoperative rotational kinematics. However, WB conditions reflect actual activities; therefore, understanding the differences between WB and NWB conditions is particularly important.

At mid-flexion, NWB knees indicated a significant varus alignment compared to WB knees, consistent with previous cadaveric study20. In other words, OKC knee flexion indicated a significant varus alignment than CKC flexion at mid-flexion20. Because the NWB position results in slightly greater varus alignment than the WB position in TKA, maintaining slight valgus alignment through kinematic alignment may better approximate normal function than aiming for neutral alignment through mechanical alignment.

The APT of SEA indicated a similar kinematic trend to APT of LCPs, though the medial APT of SEA showed slight anterior movement at early flexion. In other words, the medial movement of LCPs almost recreates that of SEA. On the lateral sides, APT in WB showed more posterior translation of femur relative to than that in NWB at mid-flexion. Nakazato et al. reported that tibial widening was independently correlated to lateral posterior tibial slope (PTS) after anatomical rectangular tunnel ACL reconstruction (ACLR), as increased PTS can result in posterior translation of the femur during WB activities, increasing ACL strain and injury risk34. The lateral PTS in this study was 9.4 ± 2.0°, which may contribute to large posterior translation of the femur observed at mid-flexion. Accordingly, in rehabilitation after ACLR, patients with increased lateral PTS should exercise caution with half-squatting at an early stage, while squatting with a forward-leaning posture is recommended.

ACL forces decreased with flexion in both WB and NWB knees from early to mid-flexion. In this study, the ACL forces in WB were smaller than those in NWB at early flexion. NWB exercises generally load the ACL more than WB exercises owing to increased hamstring activity35. This muscle contraction during WB activity may reduce the role of the ACL in stabilizing the joint. Additionally, the femoral origin of the local coordinate system, with respect to the tibia, in WB was more inferior, anterior, and medially located than that in NWB (Supplementary Table S1-3), which induced ACL elongation. This femoral origin movement was similar to that in a previous study36. The ACL elongation at early flexion might affect the increasing ligament force. By contrast, PCL forces increased with flexion in both WB and NWB knees from mid to deep flexion. The PCL force in WB was smaller than that in NWB, it was only 60° of flexion. By contrast, the pPCL force in WB was larger than that in NWB at mid-flexion. Hosseini et al. reported that especially pPCL strain during forward lunge was larger than that during passive flexion at mid-flexion37. This pPCL elongation in WB might affect the increase of ligament force.

This study has some limitations. First, volunteers performed only squatting and passive knee flexion, so other activities of daily living, such as walking, kneeling, and stair activities, may yield different results. Second, we evaluated only male Japanese. Other genders and ethnicities may indicate different results.

In conclusion, the APT of LCPs in WB and NWB conditions showed no anterior translation from extension to mid-flexion, with the medial APT of LCPs in NWB condition more posteriorly located than in WB knees. In TKA, a medially stabilized articular surface, such as medial-pivot design, or a medial stabilization surgical technique, such as avoiding MCL release, may be important for achieving native knee kinematics under varying WB conditions. In addition, WB exercises may be recommended to help preserve the cruciate ligaments.

Methods

This study included 20 Japanese male volunteers with no history of knee pain. All participants provided informed consent, and the study was approved by The University of Tokyo Institutional Ethics Review Board. The following methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Fluoroscopic imaging was performed in the sagittal plane while each volunteer performed squatting (WB) and active assisted knee flexion motions (NWB) at a natural pace. The NWB motions were performed in a single leg while sitting (Fig. 6). Participants practiced the motions several times prior to recording. The volunteers’ mean age was 34.5 ± 2.5 years, with an average height of 174.0 ± 0.1 cm and weight of 69.8 ± 7.7 kg.

Sequential motion was recorded as digital X-ray images (1024 × 1024 × 12 bits/pixel, 7.5-Hz serial spot images as a DICOM file) using a 17-inch flat panel detector system (ZEXIRA DREX-ZX80, Toshiba, Tokyo, Japan). Images were processed using dynamic range compression to enhance edge visibility. Knee spatial position and orientation were estimated using a two-dimensional (2D)/three-dimensional (3D) registration technique38,39. This technique was based on a contour-based registration algorithm that uses single-view fluoroscopic images and 3D computer-aided design (CAD) models38,39. 3D bone models were generated using computed tomography (CT: Aquilion ONE, 320-slice CT scanner, slice thickness 1 mm, Canon, Tokyo, Japan) before surgery and used them for CAD models. The CAD models were reconstructed using software (ZedView, LEXI, Tokyo, Japan). The estimation accuracy for relative motion between 3D bone models was ≤ 1° in rotation and ≤ 1 mm in translation39. The local coordinate system in the bone model was produced according to a previous study39. Knee rotations were described using the joint rotational convention of Grood and Suntay40. The femoral rotation and varus-valgus angle relative to the tibia; APT of the surgical epicondylar axis (SEA), defined as the line connecting the medial sulcus (medial side) and lateral epicondyle (lateral side) of the femur on a plane perpendicular to the tibial mechanical axis; and APT of femoral LCPs on the proximal tibial plane were analyzed at each flexion angle (Fig. 7)39,41. The proximal tibial plane was defined as the plane that originally adjusted medial inclination and posterior slope. Intraclass correlation coefficients to measure intra- and interobserver reliability were 0.99 and 0.99 for detecting the medial sulcus and 0.98 and 0.99 for detecting the lateral epicondyle. External rotation was denoted as positive, and internal rotation as negative. Valgus was defined as positive, and varus as negative. Positive or negative values of APT were defined as anterior or posterior to the axis of the tibia, respectively.

Both bundles of the ACL and PCL were identified using the osseous landmarks on the preoperative CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI: Vantage Centurian ZGO, fat-suppressed proton density-weighted images, Canon, Tokyo, Japan)22,42,43,44. The accuracy of the attachment area was within 0.7 ± 0.1 mm44. Each cruciate ligament force was calculated using commercially available software (VivoSim v1, Advanced Mechanical Technology Inc., Watertown, MA, USA; https://amti.biz/index .aspx). The path of each ligament was assumed to be a straight line, and the effects of the ligament-bone contact were neglected. Each ligament was assumed to be elastic, and its properties were described using a nonlinear force–strain relationship (Videos 1 and 2)45,46,47. The stiffness values of the model ligaments were derived from previously published data47,48,49 and were further adjusted to match knee-joint laxity measurements from intact and ACL-deficient knees reported in cadaveric studies46,50. Cruciate ligament forces at each flexion angle were computed for each squatting cycle. All values were expressed as means ± standard deviations.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) ²⁰¹⁷. Repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post-hoc pairwise comparison tests evaluated differences in rotational kinematics, APTs, and cruciate ligament forces. Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05. A paired t-test was used to compare knee flexion angles. A priori power analysis was conducted using G*Power (version 3.1.9.7; Heinrich Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany)51 prior to the study. The analysis determined that a minimum of eight knees was required to achieve an alpha level of 0.05, a power of 0.95, and an effect size of 0.25.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kim, M. S., Koh, I. J., Choi, Y. J., Lee, J. Y. & In, Y. Differences in patient-reported outcomes between unicompartmental and total knee arthroplasties: A propensity score-matched analysis. J. Arthroplast. 32, 1453–1459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2016.11.034 (2017).

Nakahara, H. et al. Correlations between patient satisfaction and ability to perform daily activities after total knee arthroplasty: why aren’t patients satisfied? J. Orthop. Science: Official J. Japanese Orthop. Association. 20, 87–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00776-014-0671-7 (2015).

Nam, D., Nunley, R. M. & Barrack, R. L. Patient dissatisfaction following total knee replacement: a growing concern? Bone Joint J. 96–b. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620x.96b11.34152 (2014).

Matsuda, S., Kawahara, S., Okazaki, K., Tashiro, Y. & Iwamoto, Y. Postoperative alignment and ROM affect patient satisfaction after TKA. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 471, 127–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-012-2533-y (2013).

Bourne, R. B., Chesworth, B. M., Davis, A. M., Mahomed, N. N. & Charron, K. D. Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: who is satisfied and who is not? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 468, 57–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-009-1119-9 (2010).

Noble, P. C., Conditt, M. A., Cook, K. F. & Mathis, K. B. The John Insall Award: patient expectations affect satisfaction with total knee arthroplasty. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 452, 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.blo.0000238825.63648.1e (2006).

Wylde, V. et al. Patient-reported outcomes after total hip and knee arthroplasty: comparison of midterm results. J. Arthroplast. 24, 210–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2007.12.001 (2009).

Kono, K. et al. Effect of weight-bearing in bicruciate-retaining total knee arthroplasty during high-flexion activities. Clin. Biomech. (Bristol, Avon). 92, 105569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2021.105569 (2022).

Kono, K. et al. Bicruciate-stabilised total knee arthroplasty provides good functional stability during high-flexion weight-bearing activities. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthroscopy: Official J. ESSKA. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-019-05375-9 (2019).

Kono, K. et al. Weight-bearing status affects in vivo kinematics following mobile-bearing unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthroscopy: Official J. ESSKA. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-020-05893-x (2020).

Kage, T. et al. In vivo kinematic comparison of medial pivot total knee arthroplasty in weight-bearing and non-weight-bearing deep knee bending. Clin. Biomech. (Bristol, Avon). 99, 105762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2022.105762 (2022).

Horiuchi, H. et al. In vivo kinematic analysis of cruciate-retaining total knee arthroplasty during weight-bearing and non-weight-bearing deep knee bending. J. Arthroplast. 27, 1196–1202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2012.01.017 (2012).

Shimizu, N., Tomita, T., Yamazaki, T., Yoshikawa, H. & Sugamoto, K. The effect of weight-bearing condition on kinematics of a high-flexion, posterior-stabilized knee prosthesis. J. Arthroplast. 26, 1031–1037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2011.01.008 (2011).

Horiuchi, H. et al. In vivo kinematic analysis of cruciate-retaining total knee arthroplasty during weight-bearing and non-weight-bearing deep knee bending. J. Arthroplast. 27, 1196–1202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2012.01.017 (2012).

Fujimoto, E. et al. Significant effect of the posterior tibial slope on the weight-bearing, midflexion in vivo kinematics after cruciate-retaining total knee arthroplasty. J. Arthroplast. 29, 2324–2330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2013.10.018 (2014).

Moewis, P. et al. Author correction: weight bearing activities change the pivot position after total knee arthroplasty. Sci. Rep. 10(759). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-57831-z (2020).

Moewis, P. et al. Weight bearing activities change the pivot position after total knee arthroplasty. Sci. Rep. 9, 9148. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-45694-y (2019).

Moewis, P. et al. Retention of posterior cruciate ligament alone may not achieve physiological knee joint kinematics after total knee arthroplasty: A retrospective study. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. Vol. 103, 146–154. https://doi.org/10.2106/jbjs.20.00024 (2021).

Pfitzner, T. et al. Modifications of femoral component design in multi-radius total knee arthroplasty lead to higher lateral posterior femoro-tibial translation. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthroscopy: Official J. ESSKA. 26, 1645–1655. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-017-4622-7 (2018).

Kono, K. et al. Intraoperative knee kinematics measured by computer-assisted navigation and intraoperative ligament balance have the potential to predict postoperative knee kinematics. J. Orthop. Research: Official Publication Orthop. Res. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.25182 (2021).

Kage, T. et al. Weight-bearing knee flexion angle better correlates with patient-reported outcome measures than non-weight-bearing condition in total knee arthroplasty: a three-dimensional analysis study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 22, 718. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-021-04594-x (2021).

Kono, K. et al. In vivo length change of ligaments of normal knees during dynamic high flexion. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 21 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-020-03560-3 (2020).

Rao, Z. et al. In vivo kinematics and ligamentous function of the knee during weight-bearing flexion: an investigation on mid-range flexion of the knee. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-019-05499-y (2019).

Kono, K. et al. In vivo kinematics and cruciate ligament tension are not restored to normal after bicruciate-preserving arthroplasty. J. Arthroplast. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2024.03.060 (2024).

Dennis, D. A., Komistek, R. D., Mahfouz, M. R., Haas, B. D. & Stiehl, J. B. Multicenter determination of in vivo kinematics after total knee arthroplasty. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 37–57. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.blo.0000092986.12414.b5 (2003).

Kage, T. et al. In vivo kinematics of a newly updated posterior-stabilised mobile-bearing total knee arthroplasty in weight-bearing and non-weight-bearing high-flexion activities. Knee 29, 183–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knee.2021.02.005 (2021).

Kono, K. et al. In vivo three-dimensional kinematic comparison of normal knees between flexion and extension activities. Asia-Pacific J. Sports Med. Arthrosc. Rehabilitation Technol. 36, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asmart.2024.01.003 (2024).

Hirokawa, S., Solomonow, M., Lu, Y., Lou, Z. P. & D’Ambrosia, R. Anterior-posterior and rotational displacement of the tibia elicited by quadriceps contraction. Am. J. Sports Med. 20, 299–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/036354659202000311 (1992).

Li, G., Kawamura, K., Barrance, P., Chao, E. Y. & Kaufman, K. Prediction of muscle recruitment and its effect on joint reaction forces during knee exercises. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 26, 725–733 (1998).

Olivetti, L. et al. A novel weight-bearing strengthening program during rehabilitation of older people is feasible and improves standing up more than a non-weight-bearing strengthening program: a randomised trial. Aust. J. Physiother. 53, 147–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0004-9514(07)70021-1 (2007).

Li, G. et al. Kinematics of the knee at high flexion angles: an in vitro investigation. J. Orthop. Research: Official Publication Orthop. Res. Soc. 22, 90–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0736-0266(03)00118-9 (2004).

Kono, K. et al. Intraoperative kinematics of bicruciate-stabilized total knee arthroplasty during high-flexion motion of the knee. Knee 29, 291–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knee.2021.02.010 (2021).

Inui, H. et al. Comparison of intraoperative kinematics and their influence on the clinical outcomes between posterior stabilized total knee arthroplasty and bi-cruciate stabilized total knee arthroplasty. Knee 27, 1263–1270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knee.2020.06.008 (2020).

Nakazato, K. et al. Lateral posterior tibial slope and length of the tendon within the tibial tunnel are independent factors to predict tibial tunnel widening following anatomic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthroscopy: Official J. ESSKA. 29, 3818–3824. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-020-06419-1 (2021).

Escamilla, R. F., Macleod, T. D., Wilk, K. E., Paulos, L. & Andrews, J. R. Anterior cruciate ligament strain and tensile forces for weight-bearing and non-weight-bearing exercises: a guide to exercise selection. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 42, 208–220. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2012.3768 (2012).

Li, P. et al. In-vivo tibiofemoral kinematics of the normal knee during closed and open kinetic chain exercises: A comparative study of box squat and seated knee extension. Med. Eng. Phys. 101, 103766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medengphy.2022.103766 (2022).

Hosseini Nasab, S. H. et al. Loading patterns of the posterior cruciate ligament in the healthy knee: A systematic review. PloS One. 11, e0167106. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0167106 (2016).

Yamazaki, T. et al. Improvement of depth position in 2-D/3-D registration of knee implants using single-plane fluoroscopy. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 23, 602–612 (2004).

Kono, K. et al. In vivo three-dimensional kinematics of normal knees during different high-flexion activities. Bone Joint J. 100–b. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620x.100b1.bjj-2017-0553.r2 (2018).

Grood, E. S. & Suntay, W. J. A joint coordinate system for the clinical description of three-dimensional motions: application to the knee. J. Biomech. Eng. 105, 136–144 (1983).

Kono, K. et al. In vivo kinematic comparison before and after mobile-bearing unicompartmental knee arthroplasty during high-flexion activities. Knee https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knee.2020.03.002 (2020).

Inou, Y., Tomita, T., Kiyotomo, D., Yoshikawa, H. & Sugamoto, K. What kinds of posterior cruciate ligament bundles are preserved in cruciate-Retaining total knee arthroplasty? A three-dimensional morphology study. J. Knee Surg. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1675184 (2018).

Shino, K., Mae, T. & Tachibana, Y. Anatomic ACL reconstruction: rectangular tunnel/bone-patellar tendon-bone or triple-bundle/semitendinosus tendon grafting. J. Orthop. Science: Official J. Japanese Orthop. Association. 20, 457–468. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00776-015-0705-9 (2015).

Lee, Y. S., Seon, J. K., Shin, V. I., Kim, G. H. & Jeon, M. Anatomical evaluation of CT-MRI combined femoral model. Biomed. Eng. Online. 7, 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-925x-7-6 (2008).

Blankevoort, L. & Huiskes, R. Ligament-bone interaction in a three-dimensional model of the knee. J. Biomech. Eng. 113, 263–269 (1991).

Pandy, M. G., Sasaki, K. & Kim, S. A. Three-dimensional musculoskeletal model of the human knee joint. Part 1: theoretical construct. Comput. Methods Biomech. BioMed. Eng. 1, 87–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/01495739708936697 (1998).

Shelburne, K. B., Kim, H. J., Sterett, W. I. & Pandy, M. G. Effect of posterior tibial slope on knee biomechanics during functional activity. J. Orthop. Research: Official Publication Orthop. Res. Soc. 29, 223–231. https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.21242 (2011).

Shelburne, K. B. & Pandy, M. G. A musculoskeletal model of the knee for evaluating ligament forces during isometric contractions. J. Biomech. 30, 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0021-9290(96)00119-4 (1997).

Kono, K. et al. Cruciate ligament force of knees following mobile-bearing unicompartmental knee arthroplasty is larger than the preoperative value. Sci. Rep. 11, 18233. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-97655-z (2021).

Shelburne, K. B., Pandy, M. G., Anderson, F. C. & Torry, M. R. Pattern of anterior cruciate ligament force in normal walking. J. Biomech. 37, 797–805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2003.10.010 (2004).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A. & Lang, A. G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods. 41, 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/brm.41.4.1149 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage [http://www.editage.com] for editing and reviewing this manuscript for English language.

Funding

We thank the Grant-in-Aid for Science Research from the Japanese Orthopedic Society of Knee Arthroscopy and Sports Medicine Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KK contributed to formal analysis, investigation, and writing of the manuscript. RM, TK, and SK carried out data curation and conceived the study. TY provided technical assistance. MT, ST, RY, KK, TA, TK, TM, SK, HI, DD, TT, and ST provided general support. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 3

Supplementary Material 4

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kono, K., Murakami, R., Kage, T. et al. The effect of weight-bearing status on kinematics and cruciate ligament force in normal knees. Sci Rep 15, 40019 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23577-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23577-9