Abstract

Focused ion beam scanning electron microscopy (FIB-SEM) tomography has increasingly been utilized for acquiring three-dimensional (3D) microstructure features at the sub-micron scale in irradiated nuclear materials. This technique involves sequential ion beam slicing followed by electron beam imaging and compositional mapping using energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS). Despite its growing use, several challenges persist. These include the time-intensive nature of data collection of EDS data, difficulties in distinguishing between various microstructures, and issues with image alignment. These challenges currently limit the broader application of FIB-SEM tomography in the field. To overcome these limitations, we propose using convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to automate microstructure identification in SEM images. Our study introduces a new framework for identifying microstructures in irradiated U-10Zr (wt%) metallic fuel with limited annotated data. The framework includes the creation of a reliable annotated dataset with paired SEM and ground truth data from EDS maps, the applications of CNNs for microstructure identification, and the validation of model performance. Specifically, we employed the Segment Anything Model (SAM) to align SEM images with corresponding EDS maps and focused ion beam (FIB) tomography SEM data. We evaluate several models, including Patch-based U-Net, Attention U-Net, and Residual U-Net, finding that patch-based U-Net exhibits superior segmentation performance and consistency. This approach reduces reliance on EDS detectors and aids in accelerating nuclear material analysis process, highlighting the potential of advanced deep learning techniques to improve microstructural understanding in nuclear material. This is the first framework to integrate SAM and Patch-based CNN models for semantic segmentation of irradiated nuclear materials, with potential applicability to other tomography datasets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

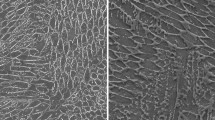

Focused ion beam scanning electron microscopy (FIB-SEM) tomography has recently been employed in a variety of studies across different fields, including biological science1, geological materials2, and nuclear materials3,4,5,6,7.This technique involves sequentially milling away thin layers of the materials, followed by SEM imaging the surface and/or compositional analysis through energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS). This technique enables three-dimensional visualizations of the microstructures in examined materials, allowing researchers to study intricate details in nuclear materials, such as phases, boundaries, distribution of porosity, and fission products. The microstructures observed through SEM are often visually similar and indistinguishable to the naked eye, making it challenging to differentiate between various phases. To address this difficulty, energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) is often paired with SEM imaging for elemental analysis, aiding in the identification of various phases. When SEM imaging and EDS are performed on the same regions of a sample, often at different resolutions, more accurate phase identification can be achieved, as shown in Fig. 1. However, enabling this level of accuracy is difficult to achieve using through SEM imaging alone.

Conducting comprehensive microstructural and compositional analysis using FIB-SEM presents several challenges, primarily related to time and labor costs. Acquiring EDS maps requires long-term instrumental stability since it is time-consuming, often limiting the maximum acquisition of material volume. Furthermore, accurately identifying specific microstructures often requires the combination of multiple EDS elemental maps, which frequently contain noise8,9 that can obscure the details necessary for accurate phase identification. For FIB-SEM tomography of irradiated materials, operational constraints such as minimizing radioactivity often necessitate limiting EDS map acquisition, making it impractical to apply EDS to every SEM image. Typically, only 8–10 patches are selected for EDS characterization mainly to confirm the presence of specific elements, leaving part of sample unanalyzed. Additionally, aligning EDS maps and SEM images is essential to correct misalignment caused during data collection due to software setting variations and drifting problems. These challenges collectively limit the efficacy for FIB-SEM tomography capabilities and data analysis.

Deep learning models, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), offer a promising solution to overcome some limitations and improve SEM-EDS data analysis. Bangaru et al. utilized a CNN to identify four distinct microstructures—aggregates, hydrated cement, anhydrous cement, and pores—in SEM images of concrete10. This approach helped in understanding the performance and potential causes of cracks or failures in concrete material. Other studies have utilized CNN-based architectures to facilitate microstructure characterizing in nuclear materials. For example, Wang et al. introduced a residual model with a ResNet50 encoder11, pre-trained on the ImageNet dataset12, for segmenting pores in irradiated metallic fuels13. Although this study demonstrated that while residual convolutional blocks effectively segmented large pores, it struggled to accurately identify smaller pores in SEM images. Sun et al. implemented a CNN-based instance segmentation model of extracting fission gas bubbles in SEM images of irradiated U-10Zr14. Moreover, CNNs have been applied to various microscopy datasets, achieving excellent characterization performance15,16,17. The advantages of applying CNN models to material science have been demonstrated in recent years. However, the good performance of CNN models highly depends on large, carefully annotated imaging datasets, which are typically generated manually14, synthetically18 or based on EDS maps11 in material science.

In our specific case, the absence of ground truth annotated data for CNN training posed a significant challenge. Moreover, no synthetic data is available on the studied material and labeling manually is both time-consuming and labor-intensive. Thus, generating the ground truth from EDS maps is the best choice. To overcome the challenge of noise posed to EDS map data analysis, we propose using EDS to generate ground truth data with a new framework for data preparation. Following data preparation, we employ Patch-Based CNNs (PBCNNs) to identify microstructures. These models can characterize materials more efficiently with less noise, providing a promising solution to overcome the challenges that low-resolution EDS detectors pose. The workflow includes the following steps:

1) creating a reliable dataset by using EDS maps to generate ground truth data for training the deep learning model.

2) employing several deep learning models to identify the microstructures from SEM images following the data preparation.

3) validating the performance of the models and utilizing the test performed model on unseen dataset.

The pipeline of the proposed model is illustrated in Fig. 2. This approach aims to address the limitations of EDS availability and enhance the efficiency and accuracy of microstructural analysis. The key contributions of this work include:

-

Developing a new framework for data preparation in FIB-SEM tomography data.

-

Implementing PBCNNs for efficient segmentation of material microstructures in SEM images.

-

Performed a comprehensive analysis of state-of-the-art CNN-based SEM segmentation methods.

Materials and experiments

U-10Zr (wt%) metallic fuel is the leading candidate for the next-generation sodium-cooled fast reactor19,20. Prototypical annular and solid U-10Zr fuels were used for the data analysis, which was designed and fabricated in the Materials & Fuel Complex at Idaho National Laboratory (INL)21,22. The studied sample is from a high burn-up (13.1 at%) solid U-10Zr metallic fuel cladded with HT9 as part of the MFF-3 irradiation test in the Fast Flux Test Facility (FFTF)23. Advanced characterizations of the material were conducted previously at Irradiated Materials Characterization Laboratory (IMCL) using focus ion beam (FIB) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM).

In this study, the SEM images were collected under 5525× magnification with a field of view (FOV) using backscattered electrons (BSE) using Helios NanoLab G3 Dual Beam Plasma FIB instrument at IMCL. 65 pairs of SEM images and EDS maps were collected. Each SEM image is at a size of 1024 × 1512 pixels with a resolution of 0.048 \(\:\mu\:m/pixel\), while each EDS map size is 400 × 512 pixels with resolution of 0.12 \(\:\mu\:m/pixel\). Besides, 150 SEM images with a higher resolution of 0.0096 μm/pixel were collected without EDS maps. Based upon previous findings22,24, we focused on six key microstructure features. Pores represent voids within the fuel that affect structural integrity and thermal conductivity, essential for assessing fuel swelling and gas release. Platinum (Pt) is often deposited as a protective layer on the surface of the sample before milling. This helps to prevent damage to the underlying material during the ion milling process. HT9 Cladding enhances high-temperature performance and corrosion resistance of the cladding, making its examination vital for understanding protective effectiveness under irradiation. Uranium (U) matrix, the primary energy source, provides insights into phase transformations and irradiation impacts on fuel microstructure. Lanthanides, as fission products, form separate phases, and their distribution helps understand their behavior and effects on fuel performance and safety. Studying these classes— pores, Pt, HT9 cladding, U, lanthanides, and other—provides valuable information on microstructural changes, material interactions, and overall performance of the U-10Zr fuel, aiding in the development of next-generation sodium-cooled fast reactors.

Methods

Data preparation

As we discussed in the introduction, one of the primary challenges in employing CNNs for phase detection is the limited availability of annotated data. High-quality, labeled EDS datasets are essential for training robust and accurate CNN models, but obtaining such data can be resource-intensive and time-consuming. EDS maps often contain noise, complicating the data preparation process. To address this issue, we utilized EDS maps to generate ground truth annotations efficiently, aligned SEM and the corresponding EDS for model training, and employed patch extraction, thereby increasing the data volume. The workflow is shown in Fig. 3. The details for each component are described as follows.

Ground truth generation on EDS images. The data preparation process for EDS analysis begins with denoising the EDS data to enhance the quality of the elemental maps using Gaussian and minimum filtering. Following this, the denoised elemental maps are combined to form a composite image that shows the distribution and concentration of various elements within the sample. As each EDS map represents one specific element distribution within a region, we utilized overlayed EDS maps to generate annotations based on multiple threshold methods. The maps were annotated at pixel level to assign each pixel to one of six predefined classes: Pores, Pt, HT9 Cladding, U, Lanthanides, and Other. The manually annotated data establishes a ground truth dataset, serving as a reference for validating the accuracy of the analysis. Finally, segmentation masks were created through binary thresholding of EDS maps, with each element assigned a single pixel value ranging from 0 to 5.

SEM images and EDS elemental maps alignment. To ensure corresponding SEM images and EDS maps shared the same global coordinate system, we aligned SEM images with corresponding EDS elemental maps. ImageJ and Fiji25 are popular open-source software for microscopy image registration, adopting techniques such as Scale-Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT)26. Boever et al.27, combine information between corresponding X-ray Computed Tomography (CT), SEM, and EDS images with the Bookstein landmark registration technique28 to improve chemical characterization in geological materials. Although effective, such methods require high-resolution local features in image pairs to achieve high registration performance, thus struggle to register sparse and noisy EDS images. To overcome this, Mosaliganti et al.29

utilized an Insight Segmentation and Registration Toolkit (ITK)30 to segment and register microscopy datasets. By extracting global features, this method reduces the need for high-resolution FIB tomography images. In addition, Zhou et al. employed deep learning to learn appropriate transformations between microscopy image pairs and increase registration quality31. Although these solutions yielded great registration performance, both require time-consuming data preprocessing and iterative optimization steps, diminishing their speed and efficiency.

In this study, we first aligned all SEM and EDS images using a pre-trained vision transformer known as Segment Anything Model (SAM)32 for reducing the inter-and intra-slice variability between FIB tomography image pairs. Specifically, we separated the material regions of current frame in our FIB tomography dataset from the background pixels by identifying the boundaries of the U-10Zr. After identifying these boundaries on both SEM and EDS images, we cropped the images only maintaining material areas. This method does not require any training or extensive data preprocessing, thus it is more efficient than current state-of-the-art microscopy data registration methods. Figure 4 shows an example of the SEM image before and after alignment using the SAM. Figure 5 presents an example of the aligned SEM image and EDS map using SAM.

Patch-based convolutional neural network

U-Net is particularly effective for biomedical image segmentation tasks due to its architecture that captures both contextual information and precise localization. U-Net has also demonstrated high efficiency with limited data33. The architecture includes skip connections that allow for the combination of high-resolution features from the encoder with upsampled features in the decoder, which helps maintain spatial information, as shown in Fig. 6(a). Attention U-Net as shown in Fig. 6(b) often outperforms traditional U-Net models in tasks requiring fine segmentation due to its ability to emphasize important features while ignoring irrelevant ones34. However, to take full advantage of attention mechanisms, large datasets may be necessary to avoid overfitting and ensure proper learning. Residual U-Net shows superior performance in various image recognition tasks without facing issues like vanishing gradients35. The architecture can be adapted for different tasks, including classification, detection, and segmentation, as shown in Fig. 6(c). In this study, we first extracted small patches from each image to expand the number of samples in our dataset. Due to our limited sample size, we proposed a PBCNN model to characterize irradiated nuclear material, drawing inspiration from the widely successful U-Net architecture33,34,35. Additionally, we validated the model’s performance using popular metrics and compared it against Attention and Residual networks on the FIB tomography dataset. The experimental setup and performance comparisons are shown in the following sections.

Experimental setup/Implementation details

We utilized a dataset consisting of registered 65 SEM images with corresponding annotated EDS data serving as the ground truth for the training and evaluation of all PBCNN models. The leave-one-out cross-validation method was employed, wherein each SEM image was iteratively used as a test sample while the remaining images were used to train the model. This approach ensured a comprehensive assessment by allowing every patch to contribute to both training and testing.

Training dataset setup. To prepare the dataset for training the CNN model, we up-sampled all images to 640 × 1280 pixels for efficient material characterization. Then image patches measuring 256 × 128 pixels were extracted from preprocessed SEM and EDS image pairs. This procedure resulted in a total of 2952 valid patches. Besides, images were randomly augmented in each epoch using techniques such as horizontal and vertical flipping, scaling, and rotation. Additionally, all images were shuffled at the start of training to mitigate the risk of overfitting and ensure a diverse sampling of the data throughout the learning process.

Training parameter setup. The experiments were conducted on Nvidia A100 GPUs, with the primary software environment being CUDA 12.3 and Python 3.11.9. The deep learning framework was Tensorflow version 2.16.1. The Adam optimizer was employed with a learning rate set to 1 × 10-4. In this work, we implemented PBCNNs based on U-Net, Attention U-Net, and Residual U-Net architectures for the semantic segmentation of FIB tomography data. All PBCNN models were optimized using a specific learning objective. The models were trained with a batch size of 16 for 100 epochs. An exponential learning rate scheduler with a decay rate of 0.97 was used to reduce the learning rate after each epoch. Optimal material characterization performance was achieved after 80 epochs, as detailed. Fig. 7 shows that fewer epochs resulted in lower Dice similarity performance, while more training led to reduced generalizability.

Loss function selection. The input for training was defined by the following learning objective:

where \(\:{L}_{Final}\) is the summation of the mean squared error, \(\:{L}_{MSE}\), and dice similarity coefficient \(\:{L}_{DICE}\), between PBCNN output and ground truth segmentation masks.

Evaluation metrics

To obtain the best performance of the models on the specific task, we trained and tested three CNN architectures: U-Net, Attention U-Net, and Residual U-Net on the same generated dataset. The popular metrics we used include mask-level Accuracy, Dice Similarity Coefficient (Dice) and the Jaccard Similarity Index (IoU) by comparing the predicted element-wise segmentations to annotated ground truth masks. The three metrics are defined as below:

Where, \(\:A\) and \(\:B\) represent the set of pixels in the ground truth and predicted segmentation masks, and \(\:N\) is the total number of pixels. The higher metric value indicates the better performance of the model.

In the following section, we obtained the overall comparisons of the three models and justified the importance of each component of PBCNN architecture through the ablation of numerous input parameters.

Results

Overall accuracy comparison

To ensure a fair comparison of all models, we controlled experimental variables, including the use of image patches, the choice of loss functions such as DICE and cross-entropy, and data augmentation methods. This standardized approach allowed for an objective evaluation of each model’s performance. With the chosen parameters, U-Net, Attention U-Net, and Residual U-Net successfully identified five different microstructures on the studied material. Figure 8 shows the characterization result of PBCNN models on a single SEM image. Table 1 shows the characterization performance of PBCNN models on all SEM Images. U-Net achieved a mean Dice of 0.84 ± 0.01, compared to Attention U-Net and Residual U-Net with a Dice of 0.82 ± 0.01 and 0.80 ± 0.01, respectively. The highest Dice value from U-Net indicates model performance is the best among the three models.

Ablation studies

To verify the efficacy of the proposed PBCNN model, we conducted three ablation experiments, the results of which are presented in Tables 2 and 3, and 4, respectively. The first experiment aimed to determine if the patch-based method enhances model performance. The second experiment evaluated the impact of data augmentation on the results. The third experiment focused on identifying the optimal loss function for achieving the best results. Each experiment was evaluated using mask-level accuracy, Dice coefficient, and Intersection over Union (IoU) metrics.

To ensure the robustness and generalizability of the PBCNN model, we conducted a series of tests on image patches derived from the global dataset of SEM images. By segmenting the entire images into smaller patches, we aimed to evaluate model performance on localized features while preserving the contextual information inherent in the global structure. This patched approach improved the training process convergence smoother and faster, as shown in Fig. 9, and allowed us to assess the model’s capability to accurately detect microstructural phases within diverse regions of the material, ensuring that the trained model is not overly reliant on specific global characteristics but can generalize well across different scales and contexts. As shown in Table 2, we demonstrate that a patch-based approach improved the material characterization performance across several metrics and 65 SEM images. Specifically, the mean IoU and Dice on the U-10Zr dataset increased by 17.5% and 3%, respectively. Splitting SEM images into patches effectively allowed the model to capture local features in SEM images and increased the number of training samples. These improvements imply that the model benefits from enhanced sensitivity to localized features while maintaining an understanding of the overall structure.

To further enhance the performance and robustness of the PBCNN model, we employed extensive data augmentation techniques during training. This included transformations such as rotations, translations, and flipping, significantly increasing the diversity of the training dataset. By augmenting the initial dataset to over 4000 images, we observed a substantial improvement in the model’s ability to accurately detect and classify microstructural phases, as shown in Table 3. However, beyond this point, additional augmentation did not yield significant further improvements in model performance. This suggests that while data augmentation is crucial for enhancing model robustness and generalization, there is a saturation point beyond which the benefits of further augmentation diminish. Consequently, our findings underscore the importance of a balanced approach to data augmentation, optimizing the trade-off between dataset diversity and computational efficiency.

The third ablation experiment focused on determining the optimal loss function for the PBCNN model. Various loss functions were tested to identify which one provided the best performance in terms of accuracy, Dice coefficient, and IoU. The results, detailed in Table 4, show the individual DICE loss function, or composite mean squared error (MSE), and DICE loss function outperformed other loss functions.

In summary, these ablation experiments underscore the importance of patch-based methods and data augmentation in enhancing the performance of the PBCNN model, as well as the critical role of selecting an optimal loss function. The comprehensive evaluation using accuracy, Dice coefficient, and IoU metrics provides a robust validation of the model’s efficacy in detecting microstructural phases.

Application and discussion

In Sect. ❝Methods❞, our validation demonstrated that the PBCNN model surpassed both the Residual U-Net and Attention U-Net, exhibiting superior accuracy, Dice coefficients, and IoU in detecting five distinct microstructure classes within the training data. The training phase utilized 65 SEM images with lower resolution. In this section, we extend the application of the PBCNN model to another dataset of 150 SEM images with higher resolution and generate a 3D visualization of the microstructures. The goal of 3D reconstruction is driven by the enhanced observational capabilities of FIB 3D tomography compared to traditional 2D SEM. FIB 3D tomography involves incrementally milling away material atoms and conducting SEM imaging to create stacks of 2D images, which are then reconstructed into a 3D volume. Despite its advantages, FIB tomography has limitations that we address, including the misalignment of adjacent SEM during the milling process. There is a variation in the focused area during SEM, causing discrepancies between slices. To accurately visualize the 3D structure of the entire

.

To ensure adjacent SEM images sharing the same global coordinate system, we first aligned all SEM using the SAM model32 which is discussed in Sect. ❝Data preparation❞. The 3D reconstruction result of the studied material after alignment is shown in Fig. 10 (a). The PBCNN model was applied to all SEM images. The detected microstructures were reconstructed into a 3D structure for visualization in three-dimensional space in different angle views, as shown in Fig. 10 (b). Segmented 3D renderings of the five microstructural groups are shown in Figs. 11 and 12. We provided animation results for different phases as supplementary documents (fuel.gif, ht9.gif, ln.gif, others.gif, pores.gif and ln_pores.gif).From these reconstructions of different phases, the concentrated lanthanide areas are identified at the interface of HT9 cladding and Uranium fuel, while isolated lanthanides are located at the pore boundaries. Meanwhile, iron (Fe) from HT9 cladding has diffused to fuel. These observations highlight the capacity of the PBCNN framework to extract meaningful structural features from complex microstructural datasets.

At the same time, limitations of our work should be acknowledged. First, segmentation performance can be influenced by the quality of EDS data and by the binarization of overlapping elemental signals into six phase maps. Qualitative results in Fig. 12 indicate that the model generalizes well to unseen, higher-resolution FIB-SEM data, suggesting some robustness to variations in input data. However, a more systematic evaluation of the effects of EDS data resolution, noise levels, and binarization thresholds remains an important direction for future work.

Secondly, all PBCNN models were optimized using per-pixel loss functions, which do not explicitly account for global spatial alignment. This can lead to pixelated artifacts when predictions are slightly shifted, as illustrated in Fig. 8. In future work, we plan to incorporate hierarchical patch-based losses to better enforce structural coherence across scales or integrate positional encoding to restore global spatial awareness during training.

Conclusion

In this study, we utilized a vision transformer model, known as SAM, to automatically align FIB-SEM tomography data collected for high burn-up U-10Zr metallic fuel samples. We created a new dataset consisting of pairs of SEM images and EDS ground truth maps that was built in this research for different microstructure identification. Several state-of-the-art CNN models have been trained and tested on the limited new dataset.

Our results demonstrate that SAM is effective for aligning FIB-SEM tomography data. Additionally, we showed that PBCNN techniques can identify complex microstructures and accelerate the analysis process of FIB-SEM tomography data. Among the tested models, U-Net, Attention U-Net, and Residual U-Net exhibited excellent segmentation performance, with U-Net slightly outperformed the others and showing more consistent results during the ablation of input parameters.

Applying the best-performing PBCNN model to unseen FIB-SEM tomography data of the studied material, we identified the Fuel-Cladding Chemical Interaction (FCCI) region where iron from the cladding has intruded into the fuel and most lanthanides generated during irradiation are localized at the cladding-fuel interface. Another finding from the 3D reconstruction results is that isolated lanthanides are located at the boundary of pores.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first framework of combining SAM and PBCNN models for semantic segmentation of irradiated nuclear material. We believe that the proposed workflow will be easily accessible and employed on other tomography datasets.

Data availability

The data that supports the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Tomoka Hasegawa, T. et al. Norio Amizuka,Biological application of focus ion beam-scanning electron microscopy (FIB-SEM) to the imaging of cartilaginous fibrils and osteoblastic cytoplasmic processes,Journal of Oral Biosciences,Volume 59, Issue 1,2017,Pages 55–62,ISSN 1349-0079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.job.2016.11.004

Saif, T., Lin, Q., Butcher, A. R., Bijeljic, B. & Blunt, M. J. Multi-scale multi-dimensional microstructure imaging of oil shale pyrolysis using X-ray micro-tomography, automated ultra-high resolution SEM, MAPS mineralogy and FIB-SEM. Appl. Energy. 202, 628–647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.05.039 (2017).

José David Arregui-Mena, Seibert, R. L., Tyler, J. & Gerczak Characterization of PyC/SiC interfaces with FIB-SEM tomography. J. Nucl. Mater. 545 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2020.152736 (2021). 152736, ISSN 0022-3115 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022311520313441

Cristian, I. et al. Development of mesopores in superfine grain graphite neutron-irradiated at high fluence,Carbon,141,2019,Pages 663–675,ISSN 0008-223, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2018.08.039. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0008622318307723).

Casey McKinney, C., Smith, G., Helmreich, T. & Gerczak Assel Aitkaliyeva,A practical guide to characterizing irradiated nuclear fuels using FIB tomography,Micron,Volume 158,2022,103290,ISSN 0968–4328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micron.2022.103290. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0968432822000865).

José, D. et al. Kentaro Takizawa, Yutai Katoh,Nitrogen adsorption data, FIB-SEM tomography and TEM micrographs of neutron-irradiated superfine grain graphite,Data in Brief,Volume 21,2018,Pages 2643–2650,ISSN 2352–3409,https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2018.11.078

Casey McKinney, F. et al. Three-dimensional microstructural characterization of FBR MOX fuel and the contribution of microstructural features to the thermal conductivity of the fuel,Journal of nuclear Materials,572,2022,154073,ISSN 0022–3115, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2022.154073

Newbury, D. E. & Williams, D. B. The electron microscope: the materials characterization tool of the millennium. Acta Mater. 48, 323–346 (2000).

Reimers, I., Safonov, I., Kornilov, A. & Yakimchuk, I. Two-Stage alignment of FIB-SEM images of rock samples. J. Imaging. 6, 107 (2020).

Bangaru, S. S., Wang, C., Zhou, X. & Hassan, M. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image segmentation for microstructure analysis of concrete using U-net convolutional neural network. Autom. Constr. 144, 104602 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. A fine pore-preserved deep neural network for porosity analytics of a high burnup U-10Zr metallic fuel. Sci. Rep. 13, 22274 (2023).

Deng, J. et al. Imagenet: A large-scale hierarchical image database, 2009 IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 248–255. (2009).

Xu, F., Cai, L., Salvato, D., Capriotti, L. & Yao, T. Advanced characterization-informed machine learning framework and quantitative insight to irradiated annular U-10Zr metallic fuels. Sci. Rep. 13, 10616 (2023).

Sun, S. et al. An efficient instance segmentation approach for studying fission gas bubbles in irradiated metallic nuclear fuel. Sci. Rep. 13, 22275 (2023).

Fujita, S. & Han, X. H. Cell detection and segmentation in microscopy images with improved mask R-CNN, Proceedings of the Asian conference on computer vision. (2020).

Niu, Y., Mostaghimi, P., Shabaninejad, M., Swietojanski, P. & Armstrong, R. T. Digital rock segmentation for petrophysical analysis with reduced user bias using convolutional neural networks, Water Resources Research. 56 e2019WR026597. (2020).

Swanson, K., Trivedi, S., Lequieu, J., Swanson, K. & Kondor, R. Deep learning for automated classification and characterization of amorphous materials. Soft Matter. 16, 435–446 (2020).

Lee, J. W., Park, W. B., Lee, J. H., Singh, S. P. & Sohn, K. S. A deep-learning technique for phase identification in multiphase inorganic compounds using synthetic XRD powder patterns. Nat. Commun. 11, 86 (2020).

Crawford, D. C., Porter, D. L. & Hayes, S. L. Fuels for sodium-cooled fast reactors: US perspective. J. Nucl. Mater. 371, 202–231 (2007).

Miao, Y., Stauff, N., Oaks, A., Yacout, A. M. & Kim, T. K. Fuel performance evaluation of annular metallic fuels for an advanced fast reactor concept. Nucl. Eng. Des. 352, 110157 (2019).

Salvato, D. et al. Transmission electron microscopy study of a high burnup U-10Zr metallic fuel. J. Nucl. Mater. 570, 153963 (2022).

Yao, T. et al. Benson, α-U and ω-UZr2 in neutron irradiated U-10Zr annular metallic fuel. J. Nucl. Mater. 542, 152536 (2020).

Salvato, D. et al. The effect of temperature and burnup on U-10Zr metallic fuel chemical interaction with HT-9: A SEM-EDS study. J. Nucl. Mater. 591, 154928 (2024).

Janney, D. E. & Hayes, S. L. Experimentally known properties of U-10Zr alloys: A critical review. Nucl. Technol. 203, 109–128 (2018).

Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods. 9, 676–682 (2012).

Lindeberg, T. Scale invariant feature transform, (2012).

De Boever, W., Derluyn, H., Van Loo, D., Van Hoorebeke, L. & Cnudde, V. Data-fusion of high resolution X-ray CT, SEM and EDS for 3D and pseudo-3D chemical and structural characterization of sandstone. Micron 74, 15–21 (2015).

Bookstein, F. L. Size and shape spaces for landmark data in two dimensions. Stat. Sci. 1, 181–222 (1986).

Mosaliganti, K. et al. Registration and 3D visualization of large microscopy images, medical imaging 2006: image processing. 6144 923–934. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.653505 (2006).

Ibanez, L., Schroeder, W., Ng, L. & Cates, J. The ITK Software Guide (ed: Kitware, Incorporated Clifton Park, 2003).

Zhou, S. et al. Fast and accurate electron microscopy image registration with 3D convolution, Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2019: 22nd International Conference, Shenzhen, China, October 13–17, 2019, Proceedings, Part I 22. 478–486. (2019).

Kirillov, A. et al. Segment anything, Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision. 4015–4026. (2023).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation, Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th international conference, Munich, Germany, October 5–9, 2015, proceedings, part III 18. 234–241. (2015).

Oktay, O. et al. Attention u-net: learning where to look for the pancreas, arxiv Preprint arxiv:1804.03999. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:4861068 (2018).

Zhang, Z., Liu, Q. & Wang, Y. Road extraction by deep residual u-net. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 15, 749–753 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). Work supported through the INL Laboratory Directed Research& Development (LDRD) Program under DOE Idaho Operations Office Contract DE-AC07-05ID14517 (tracking number: 23A1070-069FP, 24A1081-149FP, 25A1090-192FP). The research data was collected under the Nuclear Science User Facilities (NSUF) funding. This research made use of the resources of the High Performance Computing (HPC) Center at Idaho National Laboratory, which is supported by the Office of Nuclear Energy of the U.S. Department of Energy and the Nuclear Science User Facilities. U.S. Government retains and the publisher, by accepting the article for publication, acknowledges that the U.S. Government retains a nonexclusive, paid-up, irrevocable, worldwide license to publish or reproduce the published form of this manuscript or al- low others to do so, for U.S. Government purposes. And the authors greatly acknowledge all IMCL facility support regarding sample preparation and handling.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J. U. and Y. T.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, review and editing. T. J. M.: Investigation, Data collection, Writing – review & editing. M.W. A. and V. B.: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Supervision. Y. W. and F. X.: Investigation, Data collection, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Project administration.– review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Disclaimer

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Uwaeze, J., Tang, Y., Mauseth, T.J. et al. Patch-Based convolutional neural networks for multiple microstructural features detection in FIB-SEM micrographs of irradiated nuclear fuel. Sci Rep 16, 678 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23606-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23606-7