Abstract

Oxidative stress and inflammation induced by ultraviolet (UV) exposure significantly accelerate skin aging, necessitating effective bioactive agents to prevent photodamage. This study investigates the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of cell extracts from Lavandula angustifolia cell suspension cultures, assessing their potential applications in preventing skin aging and mitigating inflammation. L. angustifolia cell suspension cultures were established from callus derived from lavender stem tissues. Notably, treatment with methyl jasmonate (MJ) significantly enhanced secondary metabolite production, as confirmed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis. The MJ-treated lavender cell extract (LC-MJ) improved cell viability and inhibited early apoptosis in mouse fibroblasts exposed to ultraviolet B-induced oxidative stress. Additionally, LC-MJ extract effectively downregulated inflammatory pathways in lipopolysaccharide-induced RAW 264.7 macrophages by reducing the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and IL-6. This anti-inflammatory effect was associated with the inhibition of MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways, indicating a protective role in inflammation-related conditions. These observations imply that LC-MJ extract could be utilized as a functional bioactive agent in the management of oxidative stress and inflammation, particularly in the prevention of skin aging and UV-induced photodamage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plants biosynthesize a wide spectrum of secondary metabolites that function as rich sources of bioactive compounds widely utilized in pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and functional foods for their medicinal and therapeutic properties. The growing demand for natural compounds with potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities has garnered increasing attention in health and biomedical research. These functional constituents actively participate in counteracting oxidative stress and inflammation, two major factors implicated in various physiological disorders, including skin aging accelerated by UV radiation exposure1. UV radiation induces oxidative stress by generating reactive oxygen species (ROS), which lead to oxidative damage of lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids2. This process accelerates cellular senescence, increases matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) expression, and degrades collagen and elastin, ultimately promoting premature skin aging and inflammation3.

Among botanical sources, L. angustifolia (commonly known as lavender) is widely recognized for its rich composition of bioactive metabolites, particularly those with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, wound-healing, neuroprotective, and cognitive-enhancing properties4,5,6,7. Notably, rosmarinic acid and linalool have been identified as key components involved in oxidative stress reduction, immune modulation, and skin barrier protection8,9. Due to its cosmeceutical and pharmaceutical potential, lavender has gained significant interest for functional applications in skin care. While numerous studies have explored the chemical composition and pharmacological properties of lavender, research has primarily focused on essential oils derived from its aerial parts and flowers10. However, the bioactive composition of essential oils is highly susceptible to environmental and processing factors, leading to variations in stability and consistency11. The large-scale production of lavender-derived bioactive compounds is often hindered by seasonal variations, geographical limitations, and the labor-intensive nature of traditional plant extraction methods12,13. As a promising alternative, plant cell suspension cultures combined with elicitation technology offer a controlled and reproducible system for optimizing culture conditions, overcoming environmental constraints, and enhancing bioactive metabolite production14,15. Among various elicitation techniques, MJ is widely recognized for its ability to stimulate key metabolic pathways, significantly increasing the production of target compounds14,15,16. These advantages establish plant cell suspension cultures as a promising platform for meeting the increasing demand for natural bioactive compounds in the healthcare, cosmetics, and pharmaceutical industries.

This study aims to develop functional biomaterials from L. angustifolia cell suspension cultures with enhanced production of bioactive compounds. Additionally, it explores the molecular mechanisms underlying their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities, focusing on their potential therapeutic applications in photodamage protection.

Although previous studies extensively characterized lavender essential oils, this research utilizing elicitation-enhanced lavender (L. angustifolia) cell suspension cultures remains limited. Thus, this study proposes a novel, reproducible approach to overcome traditional limitations such as seasonal and geographical variations. It was hypothesized that MJ elicitation could significantly enhance the production of bioactive metabolites in lavender cell cultures, thereby increasing their protective effects against UV-induced oxidative stress and inflammation. To hypothesis was examined by assessing the effects of MJ elicitation on metabolite production in L. angustifolia cell suspension cultures using GC–MS analysis. The antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of lavender cell extracts were then evaluated, along with their protective effects against oxidative stress-induced photoaging. The findings of this study contribute to the advancement of in vitro cell culture-based functional biomaterial production, offering insights into the sustainable production of high-value bioactive compounds with potential applications in healthcare, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals.

Materials and methods

Plant material and compliance statement

Lavandula angustifolia plants were obtained from a commercial horticultural farm (Herbwon, Jeongeup, South Korea) and used to induce callus for cell suspension cultures. The plant identity was confirmed based on the supplier’s documentation and morphological characteristics. As the material was cultivated and commercially obtained, a voucher specimen was not deposited. Instead, the L. angustifolia plant cell line was deposited as a patent resource in the Korean Collection for Type Cultures (KCTC) at the Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology (KRIBB) under accession number KCTC 15497BP. All experimental procedures involving L. angustifolia complied with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation.

Callus induction, and cell suspension cultures

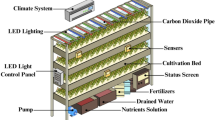

Stem tissues from L. angustifolia were used for callus induction on callus induction medium (referred to as V medium) composed of MS basal medium including Gamborg B5 vitamins at a concentration of 4.4 g/L. The V medium also contained sucrose 20 g/L, MES monohydrate 0.5 g/L, 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid 1.5 mg/L, α-naphthaleneacetic acid 0.1 mg/L, kinetin 0.25 mg/L, indole-3-acetic acid 0.1 mg/L, and gelrite 4 g/L, with a pH adjustment to 5.8; all components were purchased from Duchefa Biochemie (Haarlem, The Netherlands). Lavender cell suspension cultures were established in V liquid medium as previously described17. For scale-up to a 1-ton bioreactor, suspension cultures were sequentially expanded from 3-L to 20-L lab-scale bioreactors to a 1-ton pilot-scale bioreactor based on the previous lab-scale study. After cultivation, the cells were harvested and dried using hot air at 45 °C for 24 h, and the resulting dried cells were processed into extraction powder, as previously described17.

Sample preparation and GC–MS analysis

Dried lavender cell samples (untreated, LC-CK; MJ-treated, LC-MJ) were extracted using methanol (≥ 99.9%, GC grade). Each sample (10 mg) was mixed with 1 mL of methanol and agitated for 1 h. After filtration, the extracts were analyzed using a GCMS-QP2010 Plus instrument (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) with an Rxi-5MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 µm film thickness; Restek, USA). The oven temperature was initially held at 45 °C for 2 min, then increased to 280 °C at a rate of 4 °C per min, followed by a 5 min final hold. Helium (2 mL/min) was used as the carrier gas. Injector and detector temperatures were adjusted to 250 °C and 300 °C, respectively, and both interface and ion source were maintained at 300 °C . The detection range was m/z 30–800 over an acquisition period of 3 to 65.75 min. The injection volume of 8 µL was used in splitless mode (split ratio 0). Compounds were identified by matching spectra against the Wiley 8 library, with matches exceeding 85% similarity considered acceptable. This threshold was selected based on previous studies using the Wiley library, where 85% similarity has been commonly accepted for tentative compound identification18,19,20.

Plant and callus extraction

Metabolites were extracted by sonicating 0.3 g of dry weight sample in 10 mL of 80% methanol (v/v) for 30 min using an ultrasonic cleaner (WUC-D10H; DAIHAN Scientific, Wonju, Republic of Korea). After centrifuging the samples at 11,000 rpm for 10 min, the resulting supernatant was subjected to concentration using an evaporator (Hyper Vap HV-300; Hanil Scientific, Gimpo, Korea).

Cell culture

The mouse skin fibroblast cells (NIH-3T3) and macrophage (RAW 264.7) cell lines were purchased from the Korean Cell Line Bank (Seoul, Republic of Korea). Cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco BRL, NY, USA), containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin under a humidified incubator set at 37 °C with 5% CO2. NIH-3T3 fibroblasts were used as a model of UVB-induced oxidative stress and photodamage, and RAW 264.7 macrophages were used to investigate LPS-induced inflammatory responses.

Cell viability

A total of 1 × 104 NIH-3T3 cells per well were seeded into 96-well plates and incubated for 12 h to allow for cell attachment. The cells were then treated with LC-CK or LC-MJ extracts at concentrations of 25, 50, or 100 μg/mL for 24 h. For UVB treatment groups, the cells were first treated with the extracts for 2 h and then exposed to UVB irradiation at 25 mJ/cm2 (306 nm) using a UV crosslinker (CL-1000 M, UVP, Upland, CA, USA), followed by further incubation for 22 h. RAW 264.7 cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well in 96-well plates and incubated for 12 h to allow for cell attachment. The cells were then treated simultaneously with lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 1 μg/mL) and varying concentrations (25, 50, and 100 μg/mL) of LC-CK or LC-MJ extracts for 24 h. Cell viability was evaluated using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; EZ-3000, DoGenBio Co., Ltd., Seoul, Republic of Korea). Briefly, 10 μL of the CCK-8 solution was added to each well, and the plate was incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. Absorbance was then measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (SpectraMax iD3, Molecular Devices, USA)21. The results were expressed as a percentage relative to the untreated control group. The experiment was performed in triplicate.

Cell cycle analysis

NIH-3T3 cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well in 12-well plates and incubated for 12 h to allow for attachment. Cells were divided into four groups: untreated control (Con), LC-MJ only, UVB only, and UVB + LC-MJ. Cells in the LC-MJ and UVB + LC-MJ groups were treated with LC-MJ extract (100 μg/mL) for 2 h. Cells in the UVB and UVB + LC-MJ groups were irradiated with UVB (25 mJ/cm2, 306 nm) using a UV crosslinker (CL-1000 M, UVP, Upland, CA, USA), followed by further incubation with or without LC-MJ for 22 h, totaling 24 h of treatment. After treatment, cells were harvested by trypsinization, washed twice with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and fixed in 70% ethanol at 4 °C overnight. The fixed cells were then washed again and stained using FxCycle™ PI/RNase Staining Solution (F10797; Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions and the protocol described by Park et al.22. The stained cells were incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. DNA content was analyzed using an Attune™ NxT Flow Cytometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), and cell cycle distribution (G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases) was evaluated using FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR, USA).

Annexin V/PI staining

NIH-3T3 cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well in 12-well plates and incubated for 12 h to allow cell attachment. For treatment, cells were divided into four groups: untreated control (Con), LC-MJ (100 μg/mL) only, UVB only, and UVB + LC-MJ. Cells in the LC-MJ and UVB + LC-MJ groups were treated with LC-MJ extract (100 μg/mL) for 2 h. Cells in the UVB and UVB + LC-MJ groups were irradiated with UVB (25 mJ/cm2, 306 nm) using a CL-1000 M UV crosslinker (UVP, Upland, CA, USA), followed by incubation for an additional 22 h with or without LC-MJ, for a total treatment duration of 24 h. After treatment, cells were harvested by trypsinization, washed twice with cold PBS, and stained using the Annexin V/PI Staining Kit (BD Biosciences, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cells were incubated at room temperature in the dark for 15 min. Apoptotic cell populations were analyzed using the Attune™ NxT Flow Cytometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), and data were processed with FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR, USA).

Measurement of intracellular ROS levels

Intracellular ROS levels were measured in both NIH-3T3 fibroblasts and RAW 264.7 macrophages using CellROX™ Green Reagent (5 μM; Cat. No. C10444, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA), following the manufacturer’s protocol. For UVB-induced oxidative stress, NIH-3T3 cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well in 12-well plates and incubated for 12 h for cell attachment. Cells were divided into four groups: untreated control (Con), LC-MJ only, UVB only, and UVB + LC-MJ. LC-MJ (100 μg/mL) was pre-incubated for 2 h before UVB exposure (25 mJ/cm2, 306 nm) using a CL-1000 M UV crosslinker (UVP, Upland, CA, USA), followed by a 22 h post-irradiation incubation. After treatment, cells were harvested by trypsinization, washed twice with cold PBS, and stained with CellROX™ Green Reagent for 30 min at 37 °C in the dark. After staining, cells were washed and resuspended in PBS for flow cytometric analysis. For the inflammation-induced ROS model, RAW 264.7 cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 105 cells/well in 12-well plates and allowed to adhere for 12 h. Cells were co-treated with LPS (1 μg/mL) and varying concentrations of LC-MJ (25, 50, and 100 μg/mL) for 24 h. After treatment, cells were washed once with pre-warmed PBS, and incubated with CellROX™ Green Reagent diluted in serum-free medium for 30 min at 37 °C in the dark. Cells were subsequently washed twice with PBS, harvested using a cell scraper, filtered through a 40 μm nylon mesh, and centrifuged. The resulting cell suspensions were resuspended in PBS. Flow cytometric analysis was performed using an Attune™ NxT Flow Cytometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), acquiring at least 80,000 events per sample. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR, USA). To ensure reliable detection of ROS, light exposure was minimized throughout the staining and analysis procedures, and all steps were performed within the same timeframe to prevent ROS degradation or overoxidation.

Assessment of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP), mitochondria mass

NIH-3T3 cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well in 12-well plates and incubated for 12 h to allow for attachment. Cells were divided into four groups: untreated control (Con), LC-MJ only, UVB only, and UVB + LC-MJ. Cells in the LC-MJ and UVB + LC-MJ groups were treated with LC-MJ extract (100 μg/mL) for 2 h, followed by UVB irradiation at 25 mJ/cm2 (306 nm) using a CL-1000 M UV crosslinker (UVP, Upland, CA, USA). After UVB exposure, cells were further incubated with or without LC-MJ for 22 h, totaling 24 h of treatment. After treatment, cells were collected by trypsinization and washed twice with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) was evaluated using tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester perchlorate (TMRM; 5 μM; Cat. No. T668, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA), and mitochondrial mass was assessed using MitoTracker™ Green FM (1 μM; Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). Cells were incubated with the respective dyes at 37 °C for 30 min in the dark. After staining, cells were washed and resuspended in PBS. Stained cells were immediately analyzed using an Attune™ NxT Flow Cytometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), and data were processed with FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR, USA). A minimum of 80,000 events was collected per sample. To ensure accuracy, light exposure was minimized during staining and analysis, and all samples were processed within the same time window to avoid fluorescence variation.

NO measurement

RAW 264.7 macrophages were seeded at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well in 12-well plates and incubated for 12 h to allow for attachment. Cells were then stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 1 μg/mL) and simultaneously treated with LC-CK or LC-MJ extracts at concentrations of 25, 50, or 100 μg/mL for 24 h, following the same protocol used in the cell viability assay. After treatment, 100 μL of the culture supernatant was collected from each well and transferred to a 96-well plate. An equal volume (100 μL) of Griess reagent (Cat. No. G4410; Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) was added to each well, and the plate was incubated at room temperature for 10 min in the dark. The absorbance was measured at 540 nm using a Multiskan SkyHigh microplate reader (A51119500C, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Nitric oxide production was indirectly assessed by detecting nitrite (NO₂⁻), the stable end product of NO. The amount of NO production was expressed as a percentage relative to the untreated control group (set as 100%), based on absorbance values. A standard curve was not generated, and results reflect relative changes in NO production.

Measurement of cytokines

RAW 264.7 macrophages were seeded at a density of 1 × 10⁶ cells per 100 mm dish and incubated for 12 h to allow attachment. The cells were then treated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 1 μg/mL) in the absence or presence of LC-MJ extract (100 μg/mL) for 24 h. After treatment, the culture medium was collected and centrifuged to remove cellular debris. The concentrations of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interleukin (IL)-6 in the culture supernatants were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (TNF-α: DY410-05; IL-6: DY406-05; R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA), following the manufacturer’s protocols. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader, and cytokine levels were calculated from the standard curves provided in each kit.

Western blot analysis

RAW 264.7 macrophages were seeded at a density of 1 × 10⁷ cells per dish in 100 mm culture dishes and incubated for 12 h to allow for attachment. Cells were then stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 1 μg/mL) and simultaneously treated with LC-MJ (100 μg/mL) for 24 h. After treatment, cells were washed twice with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed using RIPA buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Cat. No. 78440, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cell lysates were incubated on ice for 30 min and centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The protein concentration of the supernatant was measured using a BCA protein assay kit (Cat. No. 23225, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Equal amounts of protein (30 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE using 10% polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Immun-Blot®, 0.2 μm; Cat. No. 1620177, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in TBS-T for 1 h at room temperature and incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies (all diluted 1:1,000): COX-2 (#12,282), iNOS (#13,120), p-p65 (#3033), p65 (#8242), p-p38 (#4511), p38 (#8690), p-JNK (#4668), JNK (#9252), p-ERK (#4370), and ERK (#4695), all from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). β-actin (1:1,000; sc-47778) was used as the loading control and obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA). After three washes with TBS-T, membranes were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies: anti-rabbit IgG (1:5000; #7074, Cell Signaling Technology) or anti-mouse IgG (1:5000; sc-2005, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Protein bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection kit (Cat. No. 32106, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and images were acquired using a FUSION FX imaging system, Evo-6 series (Vilber Lourmat, Collégien, France). Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). The immunoblotting procedure was based on the protocol described by Kim et al.23, with appropriate modifications.

Statistical analysis

Triplicate measurements from independently repeated experiments were statistically analyzed using GraphPad Prism version 8.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) to ensure the reliability and reproducibility of the data. For statistical evaluation, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test or an unpaired Student’s t-test was applied, depending on the comparison. Results are shown as mean with standard deviations (mean ± SD).

Results

GC–MS analysis of lavender cell extracts from lavender cell suspension cultures

The GC–MS profiles of methanol extracts (LC-CK and LC-MJ) from lavender cell suspension cultures reveal distinct metabolic compositions in both extracts (Fig. 1A). Figure 1B shows the peak list significantly altered by MJ treatment, highlighting 11 noticeable changes in peak area percentage (%) in the LC-MJ extract, indicating variations in peak intensity relative to LC-CK control. The peak area percentage of each identified compound in the LC-MJ extract was calculated based on its proportion of the total peak area (100%) of the 11 compounds (Fig. 1B). Compound identification was confirmed by spectral comparison with a mass spectral reference library. The identified compounds in the LC-MJ extract are classified into five categories: phenolic metabolism, Maillard reaction products (MRPs), lipid and fatty acid metabolism, amino acid and nitrogen metabolism, and steroid-related metabolism (Table S2). Among them, two compounds, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-4H-pyran-4-one (DDMP) and 2-hydroxy-4-methylbenzaldehyde (HMB), exhibited high peak area percentage ratios of 39.47% and 20.51%, respectively. These compounds were rarely found in plant extracts but are notable for their significant potential. Notably, the relative peak intensity of DDMP and HMB in the LC-MJ extract increased approximately 3.44-fold and 10.30-fold, respectively, compared with LC-CK (Fig. 1C). While these compounds were barely detected in the LC-CK extract, their production was markedly enhanced in LC-MJ following MJ treatment.

GC–MS analysis of methanol extracts from lavender cell suspension cultures. (A) GC–MS chromatograms of LC-CK and LC-MJ extracts, highlighting distinct metabolite differences. (B) Peak list of 11 major identified compounds with significant changes in the LC-CK and LC-MJ extracts. The peak area percentage of each identified compound in LC-CK and LC-MJ extracts were determined by calculating the ratio of its peak area to the total peak area (100%) of the 11 major peaks in the mass spectrum. (C) Comparison of relative peak intensity for the two major compounds (DDMP and HMB) between LC-CK and LC-MJ extracts.

Protective effects of LC-MJ extract against UVB-induced oxidative damage in mouse fibroblasts

Our previous report demonstrated that LC-MJ extract exhibits significant antioxidant activity17. Given its strong antioxidant potential, this extract has emerged as a promising candidate for anti-photoaging applications. To further evaluate the effects of LC-CK and LC-MJ extracts derived from lavender cell cultures on mouse fibroblasts, each sample was administered at varying concentrations, and cell viability was assessed 24 h post-treatment (Fig. 2). The results indicated that both LC-CK and LC-MJ extracts enhanced cell viability. Notably, at a concentration of 100 μg/mL, LC-MJ (116.92 ± 3.33%) resulted in markedly higher cell viability than LC-CK (130.778 ± 1.07%) (Fig. 2A). To investigate the protective effects against UV-induced stress, mouse fibroblasts were exposed to 25 mJ/cm2 of UVB radiation while simultaneously being treated with each extract. At 24 h post-UVB exposure, Both LC-CK and LC-MJ extracts significantly improved cell viability compared with the UVB-exposed control group. LC-CK exhibited a significant protective effect at 50 µg/mL and 100 µg/mL, with cell viabilities of (116.86 ± 3.26%) and (114.61 ± 4.06%), respectively. In contrast, LC-MJ showed significant effects at all tested concentrations—25, 50, and 100 µg/mL—with corresponding cell viabilities of (116.296 ± 4.55%), (121.43 ± 7.05%), and (126.54 ± 2.46%). Notably, LC-MJ demonstrated a more pronounced protective effect overall (Fig. 2B). These findings suggest that both LC-CK and LC-MJ extracts confer protective effects against UVB exposure in mouse fibroblasts, with LC-MJ exhibiting superior efficacy. This prompted further investigation into the cellular protective mechanisms of LC-MJ extract.

Effect of LC-MJ extract on UVB-induced cytotoxicity, cell cycle distribution, and apoptosis in NIH-3T3 fibroblast cells. (A, B) Cell viability was assessed using a colorimetric assay after UVB exposure (25 mJ/cm2) and treatment with various concentrations of LC-MJ extract (25, 50, 100 μg/mL). (C, D) Cell cycle distribution was analyzed by flow cytometry following propidium iodide (PI) staining. NIH-3T3 fibroblast cells were treated with or without LC-MJ extract (100 g/ml) for 24 h, exposed to UVB (25 mJ/cm2), and subsequently stained with PI for DNA content analysis. (E, F) Apoptosis was evaluated using Annexin V-FITC/PI double staining and flow cytometry analysis. Cells were categorized into four quadrants: Q1 (Annexin V − /PI + ; necrotic cells), Q2 (Annexin V + /PI + ; late apoptotic/secondary necrotic cells), Q3 (Annexin V + /PI − ; early apoptotic cells), and Q4 (Annexin V − /PI − ; viable cells). Con, non-UVB-exposed cells. All data are presented as mean ± SD. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; #, p < 0.05; ##, p < 0.01 compared with LC-CK group.

Cell cycle analysis was conducted to assess UVB-induced cell cycle arrest and damage. In non-UVB-exposed cells, LC-MJ treatment did not significantly alter the cell cycle distribution compared to the control (G0/G1: 70.2 ± 0.5%, S: 16.9 ± 0.25%, M: 3.7 ± 0.16%), closely resembling the untreated control group (G0/G1: 71.2 ± 0.78%, S: 16.3 ± 0.35%, M: 3.4 ± 0.07%). However, UVB exposure markedly disrupted cell cycle progression, increasing S and M phase populations (S: 20.4 ± 0.15%, M: 23.7 ± 0.60%) and reducing the G0/G1 population to 40.4 ± 0.36%. Treatment with LC-MJ following UVB exposure significantly mitigated these effects, partially restoring the G0/G1 phase to 51.6 ± 1.88% while reducing S and M phase populations to 18.1 ± 0.1% and 15.1 ± 1.39%, respectively. This protective trend was further confirmed through Annexin V/propidium iodide (PI) double staining, which revealed that LC-MJ extract decreased Annexin V-positive cells in UVB-exposed fibroblasts. Specifically, UVB irradiation markedly increased the percentage of early apoptotic cells to 18.51 ± 0.18%, compared to 3.4 ± 0.22% in the control. However, treatment with LC-MJ extract reduced early apoptosis in UVB-exposed cells to 4.94 ± 0.05%, indicating protection against early apoptosis induced by UVB radiation (Fig. 2E, F).

Antioxidant effect of LC-MJ extract against UVB-induced oxidative stress

Previous studies have confirmed that UVB irradiation increases reactive oxygen species (ROS) in fibroblast cells24. To evaluate the antioxidant potential of LC-MJ extract in mitigating intracellular ROS generation, CellROX Green reagent was employed, and total ROS levels were quantified via flow cytometry (Fig. 3). Under normal conditions, intracellular ROS levels were 9.45 ± 3.03%, and treatment with LC-MJ extract alone did not significantly alter ROS levels (11.97 ± 2.73%). However, UVB exposure alone resulted in a significant increase in ROS levels to 38.76 ± 3.88%. Notably, when LC-MJ extract was co-treated with UVB, ROS accumulation was effectively reduced to 20.2 ± 3.02%, suggesting its intracellular antioxidant activity (Fig. 3A, B).

Effect of LC-MJ extract on UVB-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and ROS production in NIH-3T3 fibroblast cells. (A, B) Intracellular ROS levels were measured using CellROX Green staining. Cells were treated with LC-MJ extract (100 μg/ml) for 24 h, exposed to UVB (25 mJ/cm2), and stained with CellROX Green reagent for 30 min. Fluorescence intensity was quantified using flow cytometry to assess ROS accumulation. (C, D) Mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) was evaluated using tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester perchlorate (TMRM) staining. Following LC-MJ extract treatment (100 μg/ml) and UVB (25 mJ/cm2) exposure, cells were stained with TMRM for 30 min. The red/green fluorescence ratio was analyzed to assess UVB-induced MMP disruption and its prevention by LC-MJ extract. (E, F) Mitochondrial mass was assessed using MitoTracker Green staining. Fluorescence intensity was measured to evaluate mitochondrial accumulation following UVB exposure and its restorative effects by LC-MJ extract. All Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). ***, p < 0.001 compared with the UVB group; N.S, no significant difference.

It has been previously reported that UVB-induced oxidative stress disrupts mitochondrial integrity by causing excessive polarization in skin cells25. Supporting these results, our data showed that LC-MJ extract did not significantly affect mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) under normal conditions (Control: 40.2 ± 0.88%, LC-MJ: 37.4 ± 4.75%). However, it effectively attenuated UVB-induced mitochondrial hyperpolarization (UVB: 46.8 ± 1.4%, UVB + LC-MJ: 35.1 ± 1.2%) (Fig. 3C, D). Furthermore, UVB exposure induced mitochondrial fusion as a compensatory mechanism for cellular damage, leading to an increase in mitochondrial mass, as observed through MitoTracker Green staining. In UVB-exposed groups, mitochondrial mass was significantly elevated (UVB: 56.8 ± 2.7%) compared with the control group (30.26 ± 7.67%). However, treatment with LC-MJ extract attenuated this UVB-induced increase in mitochondrial mass (UVB + LC-MJ: 41.1 ± 0.81%). Notably, LC-MJ extract suppressed mitochondrial fusion, thereby preventing excessive mitochondrial accumulation. Meanwhile, treatment with LC-MJ extract alone did not significantly alter mitochondrial mass compared with the control group (LC-MJ: 29.93 ± 14.09%), indicating that it does not affect mitochondrial dynamics under normal conditions (Fig. 3E, F).

Inhibitory effect of LC-MJ extract on LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine and NO production without cytotoxicity

The effect of LC-MJ extract on NO generation in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells was investigated to elucidate its anti-inflammatory mechanism (Fig. 4). First, the cytotoxicity of LC-CK and LC-MJ extracts (25, 50, 100 μg/mL) was assessed. None of the extracts exhibited cytotoxic effects on RAW 264.7 cells (Fig. 4A). LPS (1 μg/mL) stimulation markedly increased NO production in the culture supernatant compared to the unstimulated control group (Con: 100.00 ± 1.16% vs. LPS: 177.33 ± 7.37%). Co-treatment with LC-MJ extract significantly and dose-dependently attenuated this elevation, reducing NO levels to 149.64 ± 3.88% (25 µg/mL), 139.33 ± 2.27% (50 µg/mL), and 115.08 ± 7.43% (100 µg/mL). In contrast, LC-CK extract at the same concentrations resulted in comparatively higher NO levels: 172.84 ± 1.38% (25 µg/mL), 167.11 ± 0.86% (50 µg/mL), and 154.51 ± 13.25% (100 µg/mL). These findings demonstrate that LC-MJ exhibits superior NO inhibitory activity relative to LC-CK, highlighting its potent anti-inflammatory potential (Fig. 4B). Additionally, LPS stimulation led to a significant elevation in intracellular ROS levels in RAW 264.7 cells compared to the untreated control (Con: 9.86 ± 2.68% vs. LPS: 52.67 ± 2.90%). Treatment with LC-MJ extract effectively suppressed this ROS increase in a concentration-dependent manner, reducing levels to 44.57 ± 10.87% at 25 µg/mL, 37.33 ± 0.85% at 50 µg/mL, and 29.87 ± 2.47% at 100 µg/mL (Fig. 4C). Based on these findings, a fixed concentration of 100 μg/mL was used in all subsequent experiments. Notably, LC-MJ extract did not significantly affect the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines in unstimulated RAW 264.7 cells (IL-6: 1.52 ± 0.20 pg/mL; TNF-α: 1.92 ± 1.24 pg/mL vs. control IL-6: 1.74 ± 0.17 pg/mL; TNF-α: 1.08 ± 1.06 pg/mL). However, LC-MJ treatment markedly suppressed the LPS-induced elevation in cytokine secretion. Specifically, LPS stimulation increased IL-6 and TNF-α levels to 98.57 ± 1.65 pg/mL and 203.58 ± 3.89 pg/mL, respectively, whereas co-treatment with LC-MJ reduced these levels to 61.08 ± 2.64 pg/mL (IL-6) and 86.75 ± 5.30 pg/mL (TNF-α). These results strongly suggest that LC-MJ extract plays a crucial role in modulating LPS-induced inflammatory responses by suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokine and NO production (Fig. 4D, E).

Effect of LC-MJ extract on LPS-induced inflammatory responses in RAW 264.7 cells. (A) Cell viability was assessed using a colorimetric assay after treating RAW 264.7 cells with LPS (1 μg/mL) in the presence or absence of LC-CK or LC-MJ extract (25, 50, 100 μg/mL) for 24 h. (B) NO production was measured using the Griess reagent assay. RAW 264.7 cells were treated with LPS (1 μg/mL) and various concentrations of LC-MJ extract for 24 h, and NO levels were quantified from culture supernatants. (C) Intracellular ROS levels were determined using the Griess reagent. Cells were treated with LPS (1 μg/mL) and LC-MJ for 24 h, followed by fluorescence intensity measurement via flow cytometry. (D, E) Pro-inflammatory cytokine levels of IL-6 and TNF-α were determined using ELISA. Supernatants from RAW 264.7 cells treated with LPS (1 μg/mL) and LC-MJ for 24 h were collected, and cytokine concentrations were quantified. Data are presented as mean ± SD. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 vs. LPS group; ###, p < 0.001 vs. LC-CK group.

LC-MJ extract suppresses pro-inflammatory mediators by inhibiting MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways

Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB, p65) are critical intracellular signaling pathways that regulate the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators (iNOS, COX-2). To determine whether the anti-inflammatory effects of LC-MJ extract are mediated through these signaling pathways, the activation of MAPKs (p38, JNK, ERK) and the phosphorylation of the NF-κB p65 were examined (Fig. 5A–C). Treatment with LC-MJ extract alone did not alter the basal expression and phosphorylation levels of MAPKs and NF-κB in RAW 264.7 cells. However, upon LPS stimulation, it effectively reduced the phosphorylation of MAPKs, including p38, JNK, and ERK (Fig. 5A). Moreover, LC-MJ extract significantly inhibited LPS-induced phosphorylation of p65, thereby suppressing the expression of key inflammatory mediators, including iNOS and COX-2 (Fig. 5B–D).

Effect of LC-MJ extract on LPS-induced MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways in RAW 264.7 cells. (A) Western blot analysis of the MAPK pathway: The expression levels of phosphorylated and total forms of p38, JNK, and ERK were analyzed in cells treated with LPS (1 μg/mL) with or without LC-MJ extract. Actin was used as a loading control. (B) Western blot analysis of inflammatory markers: The expression levels of COX-2 and iNOS, key inflammatory mediators, were assessed in LPS-stimulated cells with or without LC-MJ extract. (C) Western blot analysis of NF-κB signaling: The protein levels of phosphorylated and total p65 were examined in LPS-treated cells with or without LC-MJ extract. (D) Densitometric analysis of Western blot bands was performed to quantify the relative protein expression levels. Results are expressed as fold changes relative to the control group. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). ***, p < 0.001 vs. LPS group; N.S, no significant difference.

These findings suggest that LC-MJ extract mitigates the LPS-induced pro-inflammatory responses in RAW 264.7 cells by modulating the MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways. Thus, LC-MJ extract may serve as a potential anti-inflammatory agent by targeting these key intracellular pathways.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that the LC-MJ extract obtained from lavender cell suspension cultures exhibits strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, highlighting its potential for preventing skin aging and mitigating inflammation. The use of NIH-3T3 fibroblasts and RAW 264.7 macrophages provided physiologically relevant models to assess the photoprotective and anti-inflammatory potential of the LC-MJ extract, respectively. While most studies on lavender have focused on essential oils extracted from its above-ground parts and flowers10, our study underscores the promise of lavender cell suspension cultures in producing standardized, metabolite-rich extracts, offering a significant advantage for industrial applications and therapeutic development. Previous studies have demonstrated that plant-derived bioactive compounds, particularly flavonoids and phenolic compounds, are key contributors to the reduction of oxidative stress and the regulation of inflammatory responses26,27. Specifically, numerous studies indicate that polyphenolic compounds can inhibit the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, while concurrently enhancing endogenous antioxidant defense mechanisms28. As shown in our GC–MS analysis, MJ elicitation in lavender cell suspension cultures (LC-MJ extract) significantly increased the biosynthesis of key phenolic compounds, including HMB, MVP, and DTBP, all of which are known to have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities (Table S1). For instance, HMB in Decalepis arayalpathra, an aromatic medicinal plant, exhibited strong antioxidant activity and induced apoptosis in breast cancer cells by promoting the accumulation of ROS, mitochondrial membrane depolarization, and cell cycle arrest29. Additionally, MVP displays anti-inflammatory and anticancer properties, particularly in pancreatic cancer models30,31,32. DTBP is a phenolic compound with antioxidant properties, contributing to cellular protection33,34.

In addition to polyphenols, Maillard reaction products (MRPs) were also enhanced by MJ elicitation, with DDMP being the most abundant MRP detected in the LC-MJ extract. DDMP has been shown to exhibit strong free radical scavenging activity and effectively reduce oxidative stress in cells35. According to prior findings, 17.5 μM DDMP achieved an 81.1% radical scavenging rate, surpassing the commonly used synthetic antioxidant butylated hydroxytoluene, which had a scavenging rate of 58.4%36. Moreover, DDMP has demonstrated anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antifungal, and anticancer properties37,38, indicating its potential for diverse biomedical applications. These results suggest that the LC-MJ extract possesses anti-inflammatory potential by suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokines and inhibiting MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways, which play central roles in inflammation. Although these findings highlight promising bioactivity, they are limited to in vitro models, and further in vivo validation is required to establish clinical relevance. Another notable MRP, maltol, has also been reported to exhibit strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, particularly in alcohol-induced oxidative stress and osteoarthritis models39,40. Notably, maltol modulates key signaling pathways such as COX-2, iNOS, NF-κB, and PI3K/AKT, suggesting that the LC-MJ extract shares a similar anti-inflammatory mechanism, as demonstrated in its anti-inflammatory experiments (Fig. 5). Although GC–MS analysis showed a notable increase in several metabolites after MJ treatment, this study did not perform precise quantification or functional assays for individual compounds. While previous studies support the activities of DDMP, HMB, and revealed metabolites, their specific roles in the observed bioeffects require further investigation. DDMP and HMB were markedly enriched in the LC-MJ extract, and both compounds are known for their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potential. However, their precise contribution to the observed biological effects remains to be clarified, as this study did not include assays using the purified compounds. Future investigations employing individual metabolite treatments will help identify the key active components of LC-MJ. Furthermore, our previous research demonstrated that MJ elicitation leads to increased production of rosmarinic acid (RA) in lavender cell suspension cultures17, suggesting that RA may also contribute to the bioactive properties of LC-MJ extract. In our previous work, the reproducibility of MJ elicitation was established at the lab scale through repeated cultures, and its feasibility was further demonstrated in a 1-ton pilot-scale system. The extracts obtained from that pilot-scale culture were utilized in the present study for biological evaluations. Although the large-scale cultivation was performed only once due to operational constraints, RA contents of the extracts were quantified (Table S1) and confirmed to exhibit the expected MJ-dependent enrichment, consistent with the trends repeatedly observed in lab-scale cultures. These results indicate that the pilot-scale extracts employed here were both representative and reliable, thereby validating the functional analyses conducted in this study. Moreover, evaluating the toxicity profile of bioactive extracts is essential to ensure their safety for pharmaceutical and cosmetic applications. As shown in Table S2, MJ treatment in lavender cell suspension cultures not only enhanced the biosynthesis of various bioactive metabolites but also reduced the levels of 5-HMF, a potentially carcinogenic compound41. This suggests that the LC-MJ extract, with its lower 5-HMF content, possesses greater pharmacological value and therapeutic potential compared with LC-CK. These findings suggest that the diverse bioactive metabolites present in the LC-MJ extract may play a crucial role in its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, reinforcing its potential applications in the pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and food industries. Although LC-MJ extract showed no cytotoxicity in vitro, further irritation or sensitization tests will be necessary to ensure its safety for cosmetic use. Importantly, the present results validate our initial hypothesis that MJ elicitation can effectively promote the synthesis of bioactive compounds in lavender cell suspension cultures, ultimately increasing their effectiveness against oxidative stress and inflammation. Unlike conventional extraction methods, the utilization of plant cell suspension cultures combined with elicitation presents an innovative, scalable, and consistent strategy, ideal for industrial-scale production and therapeutic applications.

Oxidative stress, primarily caused by free radicals, is a key factor contributing to premature aging42. Antioxidants help neutralize free radicals, diminishing the appearance of wrinkles, fine lines, and various signs of skin aging. Additionally, they strengthen the skin’s natural defense mechanisms to maintain elasticity and resilience43,44. Meanwhile, inflammation is closely associated with a range of dermatological disorders such as acne, eczema, and psoriasis45,46. Anti-inflammatory compounds help alleviate redness, irritation, and swelling, which are common symptoms of various dermatological conditions. By modulating inflammatory pathways, these compounds promote skin barrier function and tissue regeneration, leading to a healthier complexion and improved skin integrity47,48. Therefore, the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of the LC-MJ extract are expected to play a crucial role in protecting the skin from oxidative stress, reducing inflammation, and promoting overall skin health. Furthermore, the dual antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities exhibited by the LC-MJ extract suggest broader therapeutic potential beyond dermatological applications. The brain, due to its high oxygen consumption and rich lipid composition, is particularly susceptible to oxidative stress—a key factor linked to the underlying mechanisms of disorders such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases49. Antioxidant activity plays a pivotal role in neuroprotection by counteracting oxidative stress, thereby reducing neuronal damage and degeneration. It has been shown in prior research that the lavender extracts possess potent antioxidant and neuroprotective properties5,50,51,52,53. These findings collectively support the hypothesis that the LC-MJ extract may hold promise as a therapeutic candidate for the prevention or treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Therefore, further research are needed to investigate the neuroprotective potential of the LC-MJ extract, particularly in elucidating its mechanisms of action and efficacy in relevant in vitro and in vivo models.

UVB exposure is well known to induce excessive ROS production in fibroblasts, disrupting cellular homeostasis and accelerating skin damage44,54. In the present study, the LC-MJ extract effectively prevented UVB-induced early apoptosis in fibroblasts while suppressing free radical generation and mitochondrial dysfunction. Specifically, it inhibited mitochondrial hyperpolarization and prevented abnormal increases in mitochondrial mass, both of which are key contributors to UV-induced skin aging. These findings suggest that the LC-MJ extract may serve as a natural strategy for protecting against UV-induced skin damage, with potential applications in preventing photoaging and managing oxidative stress-related skin disorders. Despite the promising results, this study has several limitations that warrant further investigation. First, although the LC-MJ extract exhibited significant antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities in vitro, its efficacy and safety must be verified through further in vivo studies and clinical trials. Second, while key bioactive compounds were identified, the precise molecular mechanisms underlying their biological effects require additional clarification through mechanistic studies. Third, this study primarily focused on specific metabolites; therefore, comprehensive metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses are needed to fully elucidate the biosynthetic pathways activated by methyl jasmonate elicitation. Lastly, for industrial application, further optimization of large-scale culture conditions and extraction processes is essential to ensure production consistency and scalability. These areas of research should be addressed in future studies to fully realize the therapeutic and commercial potential of LC-MJ extract.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that MJ elicitation enhances the biosynthesis of diverse bioactive metabolites in lavender cell suspension cultures, thereby improving their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potential. The findings support the therapeutic applications of LC-MJ extract in the pharmaceutical and cosmeceutical industries while also highlighting the feasibility of plant cell suspension cultures as a sustainable and scalable platform for functional biomaterial production. Prospective studies could concentrate on elucidating the specific molecular mechanisms of these bioactive metabolites and conducting clinical evaluations to validate their therapeutic potential.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

Simitzis, P. E. Agro-industrial by-products and their bioactive compounds—An ally against oxidative stress and skin aging. Cosmetics 5, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics5040058 (2018).

Wei, M., He, X., Liu, N. & Deng, H. Role of reactive oxygen species in ultraviolet-induced photodamage of the skin. Cell Div 19, 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13008-024-00107-z (2024).

Perluigi, M. et al. Effects of UVB-induced oxidative stress on protein expression and specific protein oxidation in normal human epithelial keratinocytes: A proteomic approach. Proteome Sci. 8, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-5956-8-13 (2010).

Dobros, N., Zawada, K. & Paradowska, K. Phytochemical profile and antioxidant activity of Lavandula angustifolia and Lavandula x intermedia cultivars extracted with different methods. Antioxidants 11, 711. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11040711 (2022).

Mykhailenko, O. et al. Phenolic compounds and pharmacological potential of Lavandula angustifolia extracts for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Plants 14, 289. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14020289 (2025).

Pandur, E. et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.) essential oil prepared during different plant phenophases on THP-1 macrophages. BMC Complement Med. Ther. 21, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-021-03461-5 (2021).

Samuelson, R., Lobl, M., Higgins, S., Clarey, D. & Wysong, A. The effects of lavender essential oil on wound healing: A review of the current evidence. J. Altern. Complement Med. 26, 680–690. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2019.0286 (2020).

Pandur, E. et al. Linalool and geraniol defend neurons from oxidative stress, inflammation, and iron accumulation In in vitro Parkinson’s models. Antioxidants 13, 917. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox13080917 (2024).

Perra, M. et al. Formulation and testing of antioxidant and protective effect of hyalurosomes loading extract rich in rosmarinic acid biotechnologically produced from Lavandula angustifolia Miller. Molecules 27, 2423. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27082423 (2022).

Hajhashemi, V., Ghannadi, A. & Sharif, B. Anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties of the leaf extracts and essential oil of Lavandula angustifolia Mill. J. Ethnopharmacol. 89, 67–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-8741(03)00234-4 (2003).

Das, S. & Prakash, B. Effect of environmental factors on essential oil biosynthesis, chemical stability, and yields, plant essential oils: From traditional to modern-day application (Springer, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-4370-8_10.

Bagade, S. B. & Patil, M. Recent advances in microwave assisted extraction of bioactive compounds from complex herbal samples: A review. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 51, 138–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408347.2019.1686966 (2021).

McRae, J., Yang, Q., Crawford, R. & Palombo, E. Review of the methods used for isolating pharmaceutical lead compounds from traditional medicinal plants. Environmentalist 27, 165–174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10669-007-9024-9 (2007).

Jeong, Y. J. et al. Methyl jasmonate increases isoflavone production in soybean cell cultures by activating structural genes involved in isoflavonoid biosynthesis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 66, 4099–4105. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.8b00350 (2018).

Jeong, Y. J. et al. Induced extracellular production of stilbenes in grapevine cell culture medium by elicitation with methyl jasmonate and stevioside. Bioresour. Bioprocess 7, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40643-020-00329-3 (2020).

Khadem, A. Cell suspension culture of lavender (Lavandula angustifolia) and the influence of methyl jasmonate and yeast extract on rosmarinic acid production. SID J. 35, 280411 (2023).

Kim, B. R. et al. Elicitor-mediated enhancement of rosmarinic acid biosynthesis in cell suspension cultures of Lavandula angustifolia and in vitro biological activities of cell extracts. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 224, 109896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2025.109896 (2025).

Jang, W. G., Kim, D. & Hwang, S. G. Protaetia brevitarsis seulensis larvae ethanol extract inhibits RANKL-stimulated osteoclastogenesis and ameliorates bone loss in ovariectomized mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 165, 115112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2023.115112 (2023).

Danezis, G. P., Tsagkaris, A. S., Camin, F., Brusic, V. & Georgiou, C. A. Food authentication: Techniques, trends & emerging approaches. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 85, 123–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2016.02.026 (2016).

Karabagias, V. K. et al. Valorization of prickly pear juice geographical origin based on mineral and volatile compound contents using LDA. Foods 8, 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods8040123 (2019).

Kang, S. H. et al. Radioprotective effects of centipedegrass extract on NIH-3T3 fibroblasts via anti-oxidative activity. Exp. Ther. Med. 21, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2021.9863 (2021).

Park, H.-B., Hwang, S. & Baek, K.-H. USP7 regulates the ERK1/2 signaling pathway through deubiquitinating Raf-1 in lung adenocarcinoma. Cell death Dis. 13, 698. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-022-05136-6 (2022).

Kim, W. S. et al. RM, a novel resveratrol derivative, attenuates inflammatory responses induced by lipopolysaccharide via selectively increasing the Tollip protein in macrophages: A partial mechanism with therapeutic potential in an inflammatory setting. Int. Immunopharmacol. 78, 106072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2019.106072 (2020).

Choi, J.-K., Kwon, O.-Y. & Lee, S.-H. Kaempferide prevents photoaging of ultraviolet-B irradiated NIH-3T3 cells and mouse skin via regulating the reactive oxygen species-mediated signalings. Antioxidants 12, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox12010011 (2023).

Hegedűs, C. et al. PARP1 inhibition augments UVB-mediated mitochondrial changes—Implications for UV-induced DNA repair and photocarcinogenesis. Cancers 12, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12010005 (2020).

Mucha, P., Skoczyńska, A., Małecka, M., Hikisz, P. & Budzisz, E. Overview of the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of selected plant compounds and their metal ions complexes. Molecules 26, 4886. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26164886 (2021).

Rudrapal, M. et al. Dietary polyphenols and their role in oxidative stress-induced human diseases: Insights into protective effects, antioxidant potentials and mechanism(s) of action. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 806470. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.806470 (2022).

Bucciantini, M., Leri, M., Nardiello, P., Casamenti, F. & Stefani, M. Olive polyphenols: Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Antioxidants 10, 1044. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10071044 (2021).

Thangam, R., Gokul, S., Sathuvan, M., Suresh, V. & Sivasubramanian, S. A novel antioxidant rich compound 2-hydoxy 4-methylbenzaldehyde from Decalepis arayalpathra induces apoptosis in breast cancer cells. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 21, 101339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcab.2019.101339 (2019).

Asami, E., Kitami, M., Ida, T., Kobayashi, T. & Saeki, M. Anti-inflammatory activity of 2-methoxy-4-vinylphenol involves inhibition of lipopolysaccharide-induced inducible nitric oxidase synthase by heme oxygenase-1. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 45, 589–596. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923973.2023.2197141 (2023).

Kim, D. H. et al. 2-Methoxy-4-vinylphenol attenuates migration of human pancreatic cancer cells via blockade of FAK and AKT signaling. Anticancer Res. 39, 6685–6691. https://doi.org/10.21873/anticanres.13883 (2019).

Rubab, M. et al. Bioactive potential of 2-methoxy-4-vinylphenol and benzofuran from Brassica oleracea L. var. capitate f rubra (red cabbage) on oxidative and microbiological stability of beef meat. Foods 9, 568. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9050568 (2020).

Shakira, R. M., Abd Wahab, M. K., Nordin, N. & Ariffin, A. Antioxidant properties of butylated phenol with oxadiazole and hydrazone moiety at ortho position supported by DFT study. RSC Adv. 12, 17085–17095. https://doi.org/10.1039/D2RA02140D (2022).

Vijayakumar, K. & MuhilVannan, S. 3,5-Di-tert-butylphenol combat against Streptococcus mutans by impeding acidogenicity, acidurance and biofilm formation. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 37, 202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11274-021-03165-5 (2021).

Li, H., Tang, X.-Y., Wu, C.-J. & Yu, S.-J. Formation of 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-4(H)-pyran-4-one (DDMP) in glucose-amino acids Maillard reaction by dry-heating in comparison to wet-heating. LWT 105, 156–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2019.02.015 (2019).

Chen, Z. et al. Effect of hydroxyl on antioxidant properties of 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-4H-pyran-4-one to scavenge free radicals. RSC Adv. 11, 34456–34461. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1RA06317K (2021).

Hussein, H. M. Analysis of trace heavy metals and volatile chemical compounds of Lepidium sativum using atomic absorption spectroscopy, gas chromatography-mass spectrometric and fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy. Res. J. Pharm. Biol. Chem. Sci. 7, 2529–2555 (2016).

Olajuyigbe, O. O., Onibudo, T. E., Coopoosam, R. M., Ashafa, A. O. T. & Afolayan, A. J. Bioactive compounds and in vitro antimicrobial activities of ethanol stem bark extract of Trilepisium madagascariense DC. J. Pharmacogn. Phytother. 10, 83–94. https://doi.org/10.3923/ijp.2018.901.912 (2018).

Lu, H. et al. Maltol prevents the progression of osteoarthritis by targeting PI3K/Akt/NF-κB pathway: In vitro and in vivo studies. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 25, 499–509. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.16104 (2021).

Wang, Z. et al. Maltol improves APAP-induced hepatotoxicity by inhibiting oxidative stress and inflammation response via NF-κB and PI3K/Akt signal pathways. Antioxidants 8, 395. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox8090395 (2019).

Xiong, K., Li, M. M., Chen, Y. Q., Hu, Y. M. & Jin, W. Formation and reduction of toxic compounds derived from the Maillard reaction during the thermal processing of different food matrices. J. Food Prot. 87, 100338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfp.2024.100338 (2024).

Chen, J., Liu, Y., Zhao, Z. & Qiu, J. Oxidative stress in the skin: Impact and related protection. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 43, 495–509. https://doi.org/10.1111/ics.12728 (2021).

Mavrogonatou, E. et al. Activation of the JNKs/ATM-p53 axis is indispensable for the cytoprotection of dermal fibroblasts exposed to UVB radiation. Cell Death Dis. 13, 647. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-022-05106-y (2022).

Qin, D. et al. Rapamycin protects skin fibroblasts from ultraviolet B-induced photoaging by suppressing the production of reactive oxygen species. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 46, 1849–1860. https://doi.org/10.1159/000489369 (2018).

Gómez-Farto, A. et al. Development of an emulgel for the effective treatment of atopic dermatitis: Biocompatibility and clinical investigation. Gels 10, 370. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels10060370 (2024).

Lin, T.-K., Zhong, L. & Santiago, J. L. Anti-inflammatory and skin barrier repair effects of topical application of some plant oils. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19010070 (2018).

Matar, D. Y. et al. Skin inflammation with a focus on wound healing. Adv. Wound Care 12, 269–287. https://doi.org/10.1089/wound.2021.0126 (2023).

Schrementi, M., Chen, L. & DiPietro, L. A. The importance of targeting inflammation in skin regeneration. Skin Tissue Models https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-810545-0.00011-5 (2018).

Butterfield, D. A. & Halliwell, B. Oxidative stress, dysfunctional glucose metabolism and Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 20, 148–160. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41583-019-0132-6 (2019).

Hancianu, M., Cioanca, O., Mihasan, M. & Hritcu, L. Neuroprotective effects of inhaled lavender oil on scopolamine-induced dementia via anti-oxidative activities in rats. Phytomedicine 20, 446–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2012.12.006 (2013).

Kaka, G. et al. Assessment of the neuroprotective effects of Lavandula angustifolia extract on the contusive model of spinal cord injury in Wistar rats. Front. Neurosci. 10, 25. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2016.00025 (2016).

Rabiei, Z. & Rafieian-Kopaei, M. Neuroprotective effect of pretreatment with Lavandula officinalis ethanolic extract on blood-brain barrier permeability in a rat stroke model. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 7, S421–S426. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1995-7645(14)60269-8 (2014).

Rahmati, B., Kiasalari, Z., Roghani, M., Khalili, M. & Ansari, F. Antidepressant and anxiolytic activity of Lavandula officinalis aerial parts hydroalcoholic extract in scopolamine-treated rats. Pharm. Biol. 55, 958–965. https://doi.org/10.1080/13880209.2017.1285320 (2017).

Mo, Z., Yuan, J., Guan, X. & Peng, J. Advancements in dermatological applications of curcumin: Clinical efficacy and mechanistic insights in the management of skin disorders. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 17, 1083–1092. https://doi.org/10.2147/CCID.S467442 (2024).

Zhang, B. et al. Oleic acid alleviates LPS-induced acute kidney injury by restraining inflammation and oxidative stress via the Ras/MAPKs/PPAR-γ signaling pathway. Phytomedicine 94, 153818 (2022).

Santa-María, C. et al. Update on anti-inflammatory molecular mechanisms induced by oleic acid. Nutrients 15, 224 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology (KRIBB) Research Initiative Program (Grant No. KGM5282432, KGM5382414), the Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology (KIAT) funded by the Korean government (MOTIE) (Grant No. P0012725), and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (Grant No. 2021R1A5A8029490), and the National Research Council of Science & Technology (NST) funded by the MSIT (Grant No. CAP23051-200).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DH B contributed to conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, visualization, and original draft writing; BR K contributed to conceptualization, formal analysis, visualization, and original draft writing; KH K performed formal analysis and contributed to data visualization; GC J was responsible for validation and contributed to writing-review and editing; YJ J contributed to validation of the experimental results; S K contributed to validation of the experimental results; OR L contributed to interpretation of the data; JC J supervised the project and provided project administration and resources; CY K supervised the project, provided project administration and resources, and contributed to writing-review and final editing of the manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

The authors used ChatGPT to assist with language refinement during manuscript preparation. All content was reviewed and revised by the authors, who take responsibility for the final version.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bak, DH., Kim, B.R., Kim, KH. et al. Methyl jasmonate elicitation enhances photoprotective and anti-inflammatory properties in Lavandula angustifolia cell suspension cultures. Sci Rep 15, 39177 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23620-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23620-9