Abstract

Harris Hawk Optimizer (HHO) is a recent revolutionary algorithm developed in the literature that simulates the cooperative hunting behaviour of Parabuteo Unicinctus. Despite its simplicity, the standard HHO often suffers from slow convergence, limited exploitation capacity and performance degradation on high-dimensional and constrained problems. This study aims to develop seven novel Harris Hawk Optimizer (HHO) variants, HHO-ADAP, HHO-CHAOS, HHO-Elite, HHO-GA, HHO-Inertia, HHO-PSO, and HHO-ULTRA, that integrate adaptive mechanisms, chaotic dynamics, elite preservation, and cross-algorithmic hybridization to improve the balance between exploration and exploitation. The proposed methods were rigorously tested on the CEC 2014 benchmark suite for dimensions 10, 30, 50, and 100, as well as ten constrained engineering design problems, and results are compared against state-of-the-art optimizers CMA-ES, L-SHADE, LSHADE-cnEpSin, SPS-L-SHADE-EIG, EBOwithCMAR, WMA, and OWMA. Quantitative results demonstrate that the hybrids consistently outperform the baseline HHO and classical optimizers. HHO-PSO and HHO-Elite achieved up to 35% faster convergence and reached solution values as small as 10⁻216, compared with much weaker values (10⁻42–10⁻47) for classical baselines. On multimodal and fixed-dimension functions, HHO-Elite, HHO-CHAOS, and HHO-ADAP effectively delayed stagnation and preserved diversity, avoiding premature convergence. For engineering problems, the hybrids produced near-optimal designs: pressure vessel (≈5885.2), spring (≈0.01267), welded beam (≈1.7257), gear train (= 0), and Belleville spring (≈1.9795). Variance was as low as 10⁻16 (multiple disk clutch, gear train), while average runtimes remained below 0.01 s for most hybrids, markedly faster than champion algorithms such as SPS-L-SHADE-EIG (> 1.4 s) and WMA (> 1.8 s). The results highlight that hybridization significantly enhances HHO’s robustness, solution accuracy, and adaptability for solving large-scale, nonlinear, and constrained optimization problems in engineering and scientific domains.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In practical scenarios optimization involves reducing costs, time, and resource consumption while enhancing performance and profitability. An optimization problem is typically characterized by an objective function f, a set of decision variables X and a set of constraints C which can be expressed mathematically as follows:

where R represents the domain of real numbers, while E and I correspond to equality and inequality constraints respectively. In cases where multiple objectives need to be optimized simultaneously, the problem is referred to as a multi objective optimization problem. However, solving optimization problems can be highly challenging, as many of them fall into the category of Non-deterministic Polynomial-time hard problems. Due to their complexity, traditional mathematical approaches often struggle to find optimal solutions effectively. Scientific and engineering fields frequently encounter optimization problems that demand sophisticated algorithms to identify optimal solutions within intricate, multi-dimensional search spaces. The scientific community has turned its focus toward metaheuristic optimization techniques because these methods address complex problems without needing explicit gradient data.

Real world optimization problems are inherently complex due to their high dimensional search spaces and intricate constraints. Traditional mathematical optimization methods often struggle to provide effective solutions, particularly for NP hard problems where exhaustive searches become computationally infeasible [1]. As a result, metaheuristic algorithms have gained prominence in scientific and engineering domains due to their ability to efficiently explore vast search spaces without requiring explicit gradient information [2]. These algorithms have demonstrated superior performance in addressing challenging optimization problems across various fields including electrical and civil engineering [3] and statistical optimization [4] making them a powerful tool for real world applications.

Metaheuristic techniques inspired by natural phenomena have demonstrated remarkable success in solving challenging optimization problems across diverse fields including machine learning [5], structural engineering [6], business process optimization [7], transportation systems [8] and computational intelligence [9]. Among these nature-inspired algorithms such as Particle Swarm Optimization [10], Genetic Algorithms [11], Grey Wolf Optimizer [12] and Harris Hawks Optimization [13] have been extensively studied due to their adaptability and efficiency in handling multi-modal, constrained and high dimensional problems.

Recent advances in metaheuristics include algorithms such as EBOwithCMAR [14], CEO [15], DOA [16], PGA [17], AI-GPSed [18], Superb Fairy-wren Optimization [19], DLO [20], FCO [21], GCA [22] and LRFDB-AGDE [23] etc. Among these recent developments, the Woodpecker Mating Algorithm (WMA) [24] has attracted significant attention. Inspired by the drumming communication and mating behaviour of woodpeckers, WMA divides the population into male and female groups where females approach males based on the intensity of their drum sound. This mechanism enhances both diversification and intensification allowing WMA to efficiently solve non-convex, multimodal and scalable problems. Its improved forms such as OWMA [25], Woodpecker mating algorithm for optimal economic load dispatch [26], HWMWOA [27], GWMA [28] HSCWMA [29] further demonstrate the algorithm’s adaptability to real-world engineering challenges. In addition to these several recent algorithms have been proposed, reflecting the rapid advancement of the field. Examples include the hierarchical multi-leadership sine cosine algorithm [30], Improved Sine Cosine algorithm for global optimization and medical data classification [31], Slime Mould Algorithm (SMA) [32], Aquila Optimizer (AO) [33], Runge–Kutta Optimization (RUN) [34] etc. These developments underscore the motivation for this study: designing robust hybrid HHO variants capable of addressing the persistent challenges of premature convergence, poor scalability, and exploration–exploitation imbalance.

Another key challenge in solving real world optimization problems is the dynamic and uncertain nature of many practical environments, where problem landscapes can change over time or contain noisy, discontinuous or deceptive regions [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. Despite the growing popularity of metaheuristic algorithms, no single algorithm is universally effective across all problem domains, as stated by the No Free Lunch (NFL) theorem [36]. This limitation becomes particularly evident when handling large-scale, constrained, and highly non-linear optimization problems, where standard algorithms often exhibit stagnation or premature convergence [37, 38]. In this context, Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO), although promising, can still fall short in complex search spaces [13]. This motivates the development of enhanced HHO-based hybrid algorithms that can dynamically balance exploration and exploitation using additional adaptive mechanisms [39, 40]. While HHO has shown competitive results across various benchmarks, it still faces difficulties in maintaining population diversity and avoiding local optima, particularly in high dimensional and multi modal landscapes [40].

Harris Hawks Optimization in particular, has emerged as a competitive optimization technique by simulating the cooperative hunting strategies of Parabuteo Unicinctus. However, despite its advantages, HHO encounters challenges in maintaining a balance between exploration and exploitation, leading to premature convergence in certain problem landscapes. To overcome these limitations, hybrid metaheuristic approaches have been proposed, integrating complementary strategies such as Lévy Flight for enhanced exploration, chaotic maps for diversified search dynamics, and adaptive parameter tuning to improve convergence behaviour [41, 42].

To enhance its performance and generalizability, the development of hybrid HHO variants that integrate other optimization strategies has become a promising direction of research. These hybrid models seek to combine the exploration strength of one method with the exploitation efficiency of another, aiming for a better trade-off between diversification and intensification during the search process. In doing so, they enhance the robustness, convergence rate and adaptability of the base HHO algorithm across a wide range of application domains [37].

This research is motivated by the need to enhance the standard HHO’s capabilities, making it more robust, efficient and adaptable to diverse optimization problems. The purpose of developing the proposed hybrid HHO variants is to overcome the key limitations of the original HHO namely its tendency toward premature convergence, difficulty in maintaining population diversity, and reduced effectiveness in high-dimensional or constrained engineering problems. By incorporating adaptive controls, chaotic dynamics, swarm-based operators, and elitism, these hybrids are specifically designed to achieve faster convergence, higher solution accuracy, and improved stability across a wide spectrum of optimization scenarios.

The main contributions of this work are as follows:

-

Purpose of the Hybridization: The proposed hybrid HHO algorithms are developed to address the shortcomings of the original HHO, particularly its limited balance between exploration and exploitation and its vulnerability to stagnation in complex landscapes.

-

Development of Seven Hybrid Variants: Seven novel HHO-based hybrids are introduced HHO-CHAOS, HHO-PSO, HHO-Inertia, HHO-Elite, HHO-GA, HHO-ULTRA and HHO-ADAP.

-

Improved Exploration–Exploitation Trade-off: The hybrids leverage global exploration strategies and strong exploitation mechanisms to achieve a more effective trade-off.

-

Enhanced Convergence Behaviour: Adaptive parameter adjustments and elite-based search strategies prevent premature convergence, preserve population diversity and ensure consistent progress toward high-quality solutions.

-

Comprehensive Benchmark Evaluation: The proposed methods are validated on unimodal, multimodal and fixed-dimension benchmark functions under varied test conditions and dimensions.

-

Application to Real-World Problems: Ten constrained engineering design problems are solved to demonstrate the real-world value of the hybrids showing their ability to handle structural, nonlinear, and multi-constraint optimization tasks efficiently.

-

Comparison with State-of-the-Art Algorithms: The performance of the proposed hybrids is compared with standard HHO and leading metaheuristics.

The rest of the document is structured as follows: In Sect. Literature review provides a detailed the literature review focusing on nature-inspired metaheuristics and HHO hybridization. Section Mathematical modelling of HHO and its hybrid variants describes the original HHO algorithm and the hybridization strategies used in the proposed variants. Section Experiment set up and test functions outlines the experimental setup including benchmark functions. Section Results and discussion presents the simulation results and discussions on comparative analysis of the proposed methods against standard HHO. Section Statistical analysis discusses statistical analysis to validate the significance of the results and enhance the robustness of the analysis. Section Time complexity analysis discusses the time complexity of the proposed algorithms. Section Exploration vs. exploitation gives a discussion on exploration vs exploitation analysis providing evidence or analysis to support this balance. Section Analysis of engineering problems discusses the application of the proposed hybrid methods to engineering design problems. Section Conclusion and future work gives the conclusion and future scope.

Literature review

Numerous nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithms are used in literature to tackle these challenging real world optimization issues. Figure 1 illustrates how metaheuristic algorithms are categorized into different groups.

The classification of the metaheuristic algorithms [43].

Majority of related recent algorithms and optimizers is compiled in Table 1.

Hybrid methods which combine two or more algorithms to improve performance and eliminate local optima are nevertheless becoming more and more popular. In recent years, numerous researchers have proposed hybridizations of the Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO) algorithm to address its limitations in balancing exploration and exploitation, as well as avoiding entrapment in local optima. These hybrid approaches have demonstrated significant potential in solving a wide range of practical-world engineering and optimization problems. A Boosted Binary HHO for feature selection tasks is presented in [69]. The proposed method incorporated a binary encoding mechanism and an enhanced position updating strategy to improve convergence speed and classification accuracy. This approach proved highly effective in handling high-dimensional feature selection problems, achieving superior performance in both accuracy and computational efficiency. In [70] a Hybrid HHO tailored for solving Flow Shop Scheduling Problems (FSSP) with the objective of minimizing energy consumption in continuous manufacturing processes was presented. A Hybrid Parallel HHO algorithm is discussed for optimizing the re-entry trajectory of reusable launch vehicles incorporating constraints such as no-fly zones [71]. In [72], Gezici and Livatyali proposed an improved HHO is developed for continuous and discrete optimization tasks. Binary Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) was combined with HHO [73]. A Blockchain-Assisted Hybrid HHO model for deep learning-based DDoS attack detection in IoT environments [74]. A Multi-Strategy HHO incorporating several advanced search mechanisms and applied it to optimize Least Squares Support Vector Machines (LSSVM) [75]. In [76], HHO is utilized for load demand forecasting and optimal sizing of stand-alone hybrid renewable energy systems comprising photovoltaic, wind, and battery components. A hybrid framework combining HHO with a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) was proposed for network intrusion detection [77]. HHO is combined with SVR and the model achieved better result with optimization [78].

Some recent work of hybrid HHO that follows are listed in Table 2.

Mathematical modelling of HHO and its hybrid variants

Standard HHO

HHO consists of two primary phases: exploration and exploitation.

The Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO) algorithm is a nature-inspired metaheuristic introduced in 2019 by Heidari et al. [13]. It simulates the cooperative hunting behaviour of Harris hawks as they surround and capture prey—representing the global best solution in the search space.

The optimization process is divided into exploration and exploitation phases, governed dynamically by a prey energy parameter (E). Hawks (candidate solutions) switch strategies depending on the prey’s energy, which gradually decreases over time, mimicking escape behaviour [13].

-

1.

Exploration Phase (|E|≥ 1): Hawks explore the search space by moving toward either a randomly selected hawk or the average position of the population [13].

-

2.

Exploitation Phase (|E|< 1): Depending on E and random thresholds, the algorithm selects one of several strategies:

-

3.

Hard besiege – When the prey has low escaping energy (\(\left|E\right|<0.5\)), the hawks directly converge towards the rabbit.

$$X\left(t+1\right)={X}_{rabbit}\left(t\right)-E.\left|J.{X}_{rabbit}\left(t\right)-X(t)\right|$$where \(E\) is the escaping energy, \(J\) is the jump strength of the prey and \(X(t)\) is the hawk’s position at iteration \(t\).

Soft besiege – If the prey still has moderate energy (\(\left|E\right|>0.5\)), the attack is slower and guided by adaptive steps.

where the random jump strength \(J=2(1-rand())\)

5. Lévy Flight escape – When the prey attempts sudden escapes, hawks perform random dives around the rabbit’s location in two steps using Lévy flights [12].

-

First attempt:

$${X}_{1}={X}_{rabbit}\left(t\right)-E.\left|J.{X}_{rabbit}\left(t\right)-X(t)\right|$$ -

If this does not improve fitness, a Lévy flight–based escape is applied:

$${X}_{2}={X}_{rabbit}\left(t\right)-E.\left|J.{X}_{rabbit}\left(t\right)-X\left(t\right)\right|+L\left(\lambda \right).rand(1,d)$$

where \(L\left(\lambda \right)\) is a Lévy flight distribution.

Throughout the iterations, the algorithm tracks the best solution (“rabbit”) found so far. The hawks continuously update their positions using adaptive rules until reaching the termination condition, usually defined by a maximum number of iterations [91].

Hybrid variants of HHO

Several hybrid strategies have been introduced to enhance HHO.

HHO-ADAP: Adaptive Harris Hawks Optimization – Uses adaptive energy and probability updates, combined with Lévy flights, to dynamically increase exploration when stagnation is detected, allowing the algorithm to escape local traps.

HHO-CHAOS: Chaotic-map based Harris Hawks Optimization – Incorporates a Logistic chaotic map into the energy factor, introducing nonlinear and unpredictable perturbations in hawk movements, which diversify the search space and prevent clustering around local solutions.

HHO-Elite: Elite-preservation Harris Hawks Optimization- Retains a pool of elite solutions while applying Lévy perturbations around them. This dual strategy refines the best individuals while still injecting diversity to avoid premature convergence.

HHO-GA: Genetic Algorithm hybrid HHO – Integrates GA operators (selection, crossover, mutation) after each HHO iteration, ensuring continuous generation of new candidate solutions that help the population move out of locally optimal basins.

HHO-PSO: Particle Swarm Optimization hybrid HHO – Enhances global exploration through PSO’s velocity updates and information sharing between particles, reducing the chance that all hawks converge prematurely to a suboptimal region.

HHO-Inertia: Inertia weight based HHO – Introduces a time-varying inertia weight to balance old and new positional updates. This smooth transition reduces oscillations and helps the population escape when trapped.

HHO-ULTRA: Unified Learning Through Reinforced Adaptation –Combines adaptive energy decay, Lévy flights, and an elite archive replacement strategy, maintaining both solution diversity and refinement pressure, which allows the search to restart in new regions if stagnation occurs.

HHO-ADAP algorithm

The HHO-ADAP algorithm is an enhanced version of Harris Hawks Optimization, where adaptive strategies are introduced to balance exploration and exploitation. The energy of the hawks and the jump strength are adjusted dynamically over time to improve convergence and avoid premature stagnation. The algorithm is inspired by the cooperative hunting strategy of Harris hawks enhanced with adaptive probabilities and Levy flights for improved global search capability. Figure 2 contains the pseudocode of the proposed HHO-ADAP algorithm.

HHO-CHAOS algorithm

The HHO-CHAOS algorithm begins by initializing hawk positions and the best solution (rabbit). Each hawk’s fitness is evaluated and the best one updates the rabbit. Several chaotic maps are available in literature. In this study, the Logistic map was selected because of its well-known properties of simplicity and uniform distribution in the range [0,1]. These characteristics ensure good coverage of the search space while avoiding additional computational overhead.

The Logistic map is mathematically defined as:

where r is the control parameter that governs the chaotic behaviour. In this work, we use r = 3.99 and an initial value of \({x}_{0}=0.5\), which produces fully chaotic dynamics. This integration increases randomness in hawks’ movement and diversifies candidate solutions. This helps the algorithm escape local optima. Due to its balance of strong chaos and computational efficiency, the Logistic map was chosen over other chaotic sequences.

At every iteration, the hawks update their positions based on the rabbit’s energy which is dynamically adapted using a decaying energy factor and a chaotic component derived from the Logistic Map.

-

Exploration Phase: If escaping energy is high, hawks perch either near another randomly selected hawk or around the population mean with chaotic variation.

-

Exploitation Phase: If the energy is low, hawks apply four attack strategies:

-

Hard or soft besiege, depending on energy level.

-

If the rabbit tries to escape, Levy flight is used for local refinement.

Chaos is integrated directly into the escape energy to improve diversification and prevent premature convergence.

The algorithm iterates until the maximum number of iterations is reached, returning the best fitness and position. Figure 3 contains the pseudocode of the proposed HHO-CHAOS algorithm.

HHO-elite algorithm

The HHO-Elite algorithm improves the standard HHO by introducing an elite preservation mechanism to enhance convergence speed and search accuracy. A population of hawks is initialized along with a global best solution (rabbit). During each iteration, the top-performing individuals (typically the top 5%) are retained as elite members.

The algorithm computes the escaping energy of the prey, which dynamically controls the balance between exploration and exploitation. When the absolute value of the energy is high (|E|≥ 1), hawks perform exploration using random strategies guided by elite members. When |E|< 1, the algorithm switches to exploitation, applying soft or hard besiege tactics depending on a probabilistic threshold.

If exploitation fails to yield improvement, a Lévy flight-based strategy is applied to perturb the hawk’s position, helping escape local optima. Elite individuals guide both phases, contributing to more robust decision-making. Throughout the process, the best fitness is recorded, and elite members are updated to maintain diversity and solution quality. Figure 4 contains the pseudocode of the proposed HHO-Elite algorithm.

HHO-GA Algorithm

This hybrid algorithm integrates the Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO) framework with key operators from Genetic Algorithm (GA) to enhance exploration and solution refinement. The standard HHO operations (exploration, soft/hard besiege, and Levy flight) guide the search process based on adaptive escape energy. In each iteration, the best solution (“rabbit”) is updated. The algorithm incorporates GA-based tournament selection, crossover, and mutation after each HHO phase, improving population diversity and convergence. This fusion helps avoid local optima and improves global search capabilities. Figure 5 contains the pseudocode of the proposed HHO-GA algorithm.

HHO-PSO algorithm

The HHO-PSO algorithm integrates the explorative velocity update of Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) with the exploitation behavior of Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO) to balance global search and local refinement. Initially, hawks’ positions, velocities, and fitness values are initialized. PSO updates improve global and personal bests, followed by HHO-inspired escaping energy mechanisms to exploit the best-found solution (rabbit). The process repeats iteratively, maintaining convergence efficiency while avoiding premature local entrapment. Figure 6 contains the pseudocode of the proposed HHO-PSO algorithm.

HHO-inertia algorithm

In the inertia-based variant of HHO, the position update equations are modified by introducing a dynamic inertia weight w, which gradually decreases during iterations to shift the algorithm from exploration to exploitation. The inertia weight is computed as

where, \({w}_{initial}=0.9,\)

t is the current iteration.

T is the maximum number of iterations.

The new position of each hawk is expressed as a weighted combination of its current position and the standard HHO update term. For instance, in the hard besiege strategy, the update becomes

While in soft besiege case it is written as

where \({X}_{r}\) is the rabbit location or best solution, E is the escaping energy, and \(J=2(1-rand())\) represents the random jump strength of the rabbit. By incorporating the inertia weight in this manner, the algorithm balances the influence of the previous position and the new update. That results in smoother convergence behaviour and a more adaptive transition between exploration and exploitation. Figure 7 presents the pseudocode of the proposed HHO-Inertia algorithm.

HHO-ULTRA algorithm

The HHO-ULTRA incorporates elite preservation, adaptive escape energy and dynamic exploration–exploitation balancing. The algorithm begins by initializing a population of hawks and selecting the best individual (rabbit). In each iteration, it evaluates fitness and updates the best solution. The escaping energy is controlled by a quadratic decay function defined as

where t is the current iteration and T is the maximum number of iterations. The energy factor becomes

This function maintains a higher energy in the early stage, encouraging exploration and decreases more rapidly toward the end to strengthen exploitation. Based on E(t), hawks perform exploration (if |E|≥ 1) or exploitation (if |E|< 1). During exploitation, two moves are attempted using either direct updates or Lévy flight and only improved candidates are accepted. An elite archive preserves the best-performing solutions by replacing the worst individuals. The process continues until the maximum number of iterations is reached. Figure 8 presents the pseudocode of the proposed HHO-ULTRA algorithm.

Experiment set up and test functions

Experiment set up

The experiment has been performed with the MATLAB 2023a in the environment in Windows 11. Operating system is 64-bit, 12th Gen Intel(R) Core (TM) i7-12650H processor 2.30 GHz and 16 GB RAM.

Standard benchmark functions

The proposed hybrid variants and standard HHO is evaluated using standard benchmark functions for performance comparison [92]. Table 3 gives the mathematical expression of test functions are classified into three primary groups: unimodal (F1 to F7), multimodal (F8 to F13), and fixed-dimensional (F14 to F23) [90]. The algorithm is evaluated with 30 runs and 1000 maximum iterations.

Results and discussion

The proposed hybrid HHO variants are tested for 7 UM standard functions (F1 to F7), 6 multimodal (MM) benchmark functions (F8 to F13) and 10 fixed-dimension (FD) functions (F14 to F23) for various dimensions. The algorithm is tested for 1000 iterations and 30 trial runs. The results of UM and MM test functions are for 10, 30, 50 and 100 dimensions as shown in Tables 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11. For comparison of performance mean, standard deviation, median and minimum (best) value are considered. The results of fixed dimension test functions are shown in Table 12. The variants are evaluated are compared with standard HHO [13], WMA [24], OWMA [25], CMA-ES [93], EBOwithCMAR [14], SPS-L-SHADE-EIG [94], LSHADE_cnEpSin [95] and L-SHADE [96].

In all experiments, the population size of was fixed at 30. To confirm fairness, the same population size was used for all variants of HHO as well as for the baseline algorithms.

Results

-

A.

Unimodal functions

-

B.

Multimodal Functions

-

C.

Fixed Dimension Functions

Discussion

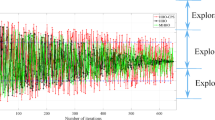

The performance of the proposed hybrids was examined on unimodal, multimodal, and fixed-dimension benchmarks at 10, 30, 50, and 100 dimensions. The results are summarized in Tables 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 and convergence patterns are shown in Figs. 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68 and 69.

Unimodal functions (F1–F7)

At 10 dimensions as shown in Table 4 and Figs. 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15, the hybrids achieved near-optimal accuracy. For F1, HHO-Elite reached the global optimum with best = 0.0 in 0.009 s. HHO-CHAOS and HHO-PSO obtained values in the range of 10–203 and 10–101. CMA-ES and LSHADE-cnEpSin remained weaker at 10⁻42 and 10⁻4⁷ with runtimes up to 0.77 s. HHO-GA and HHO-ULTRA showed higher variance. The convergence graphs confirm that HHO-Elite and HHO-CHAOS stabilized within 50 iterations, while CMA-ES and HHO-GA converged slower or oscillated.

At 30 dimensions as shown in Table 5 and Figs. 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 and 22, the robustness of adaptive and swarm hybrids was clear. HHO-Elite maintained best = 10⁻21⁶, while HHO-ADAP kept mean ≈ 10⁻⁶1. HHO-GA collapsed with best = 0.47 and mean ≈ 9.9. CMA-ES and LSHADE-cnEpSin produced results between 10⁻14 and 10⁻2⁷ but required more than 6 s. Hybrids completed in milliseconds with smooth convergence.

At 50 dimensions as shown in Table 6 and Figs. 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 and 29, the gap widened further. HHO-Elite again achieved 0.0, while HHO-CHAOS and HHO-PSO produced 10⁻2⁰2 and 10⁻⁹⁷. HHO-GA failed with best = 59.3 and mean ≈ 398. CMA-ES and LSHADE-cnEpSin gave values in the range 10⁻⁸–10⁻2⁰ but required up to 81.9 s. The convergence plots confirm HHO-Elite and HHO-CHAOS converged smoothly, while HHO-GA stagnated early.

At 100 dimensions as shown in Table 7 and Figs. 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35 and 36, scalability was tested. HHO-Elite reached 10⁻21⁶, HHO-CHAOS achieved 10⁻2⁰⁶, and HHO-PSO and HHO-ADAP gave 10⁻⁸⁷ and 10⁻⁷⁸. HHO-GA collapsed completely with best values above 2000. LSHADE-cnEpSin reached 10⁻11 but required 2.27 s, compared to milliseconds for hybrids. CMA-ES diverged, and HHO-ULTRA showed poor convergence.

Multimodal functions (F8–F13)

At 10 dimensions as shown in Table 8 and Figs. 37, 38, 39, 40, 41 and 42, the hybrids delayed stagnation and maintained diversity. For F9, HHO-CHAOS achieved results near 10⁻⁹, while CMA-ES and HHO-GA remained several orders worse. The convergence plots confirm that HHO-CHAOS and HHO-ADAP preserved exploration longer, while HHO-GA stagnated.

At 30 dimensions as shown in Table 9 and Figs. 43, 44, 45, 46, 47 and 48, HHO-ADAP performed strongly in F11 and F12, producing mean results nearly two orders better than CMA-ES. HHO-CHAOS showed stable variance. HHO-GA degraded with inconsistent values. Convergence curves confirm that hybrids avoided premature convergence, while HHO-GA oscillated around suboptimal solutions.

At 50 dimensions as shown in Table 10 and Figs. 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54 and 55, HHO-CHAOS and HHO-ADAP dominated. In F11, HHO-ADAP reached near 10⁻41, while CMA-ES remained close to 10⁻2⁰. WMA and HHO-GA failed, with best values above 1. The convergence graphs show HHO-CHAOS and HHO-ADAP progressed steadily, while HHO-GA stagnated early.

At 100 dimensions as shown in Table 11 and Figs. 56, 57, 58, 59 and 60, hybrids remained competitive. HHO-Elite and HHO-CHAOS delivered consistent results, while LSHADE-cnEpSin reached slightly better values in some functions such as F9 ≈ 10⁻15. However, LSHADE required several seconds per run, compared to milliseconds for the hybrids. Convergence plots confirm that HHO-CHAOS and HHO-ADAP balanced exploration and exploitation more effectively than CMA-ES and HHO-GA.

Fixed-dimension functions (F14–F23)

At fixed-dimension problems as shown in Table 12 and Figs. 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68 and 69, the hybrids again performed reliably. HHO-Elite and HHO-PSO gave stable results with low variance. In F20, HHO-Elite achieved 0.0, matching LSHADE-cnEpSin but at < 0.01 s. HHO-GA and HHO-ULTRA oscillated and produced weaker solutions. CMA-ES provided competitive values in some cases but with longer runtimes. The convergence graphs confirm that hybrids reached smooth convergence, while HHO-GA and HHO-ULTRA stagnated at higher values.

Mechanistically, the hybrids avoid local optima via (i) adaptive energy/probability with Lévy flights (HHO-ADAP), (ii) Logistic chaotic perturbations (HHO-CHAOS), (iii) elite preservation with Lévy perturbations (HHO-Elite), (iv) GA/PSO operators that inject novel candidates and velocity guidance (HHO-GA/HHO-PSO), (v) a time-varying inertia weight (HHO-Inertia), and (vi) ULTRA’s quadratic decay with elite-archive replacement (HHO-ULTRA). These mechanisms (Sec. “Hybrid variants of HHO”) manifest empirically as delayed stagnation, smoother convergence, and reduced premature convergence across UM/MM/FD benchmarks and D ∈ {10, 30, 50, 100}.

Statistical analysis

Wilcoxon rank sum test has been used to investigate the statistical analysis. For statistical analysis p value is considered. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was performed to validate the statistical significance of the observed differences. A significance threshold of p < 0.05 was adopted. As seen in Table 13, the proposed hybrids (HHO-Elite, HHO-CHAOS, HHO-PSO, HHO-ADAP) achieved very small p-values in most cases, often below 10⁻⁹, confirming consistent superiority over the baseline HHO. HHO-GA and HHO-UL-TRA showed higher p-values in several functions, indicating weaker performance. Against strong competitors like LSHADE-cnEpSin and CMA-ES, some functions (e.g., F14, F20, F23) showed statistical equivalence, but the hybrids retained lower runtimes. These results confirm that the improvements are statistically significant across the majority of benchmark functions.

Time complexity analysis

The computational complexity of the proposed HHO variants is derived from their iterative population-based nature. At each iteration, the fitness of all individuals in a population of size N is evaluated in a d-dimensional search space. Position updates are performed according to algorithm-specific rules. Therefore, the overall time complexity can be expressed as:

where N is the population size, T is the maximum number of iterations, and d is the problem dimension. This expression applies to all the HHO variants, with minor additional constants introduced by mechanisms such as chaos maps, elite preservation, or hybrid updates.

To validate the theoretical complexity empirical runtime experiments were performed using the Ackley function as the test problem. Runtime measurements (in seconds) were collected across different dimensions (d = 10,30,50,100) and population sizes (N = 20,30,50) for 200 iterations. The results are summarized in Table 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 and 20.

The runtime analysis demonstrates that the execution time grows approximately linearly with both the population size and the problem dimension, which is consistent with the theoretical complexity of \(O(N\times T\times d)\) per iteration. Variants such as HHO-ULTRA and HHO-Elite consistently show higher runtimes due to the additional computational mechanisms they incorporate, including elite preservation strategies and archive maintenance. Simpler hybridizations like HHO-PSO and HHO-Inertia achieve the lowest runtimes, with values below 0.02 s for cases such as N = 20, d = 10. Although the absolute differences between variants are relatively modest typically within a few milliseconds. The empirical results confirm that the constant factors introduced by different hybridization techniques significantly influence computational efficiency.

Exploration vs. exploitation

Exploration and exploitation were derived from the population diversity metric. Let \({x}_{i}^{t}\) be the position of the \({i}^{th}\) individual at iteration t, and \({x}^{t}\) the centroid of the population. Diversity was measured as:

where N is the population size.

Exploration (%) = \(\frac{\#\{t|{D}_{t+1}>{D}_{t}\}}{T}\times 100\)

Where, T = total number of iterations.

\(\#\{t|{D}_{t+1}>{D}_{t}\}=\) number of iterations where diversity increases.

Exploitation (%) = 100- Exploration (%).

Exploration vs exploitation analysis is given in Table 21. HHO-Elite variants low exploration (20–35%) and high exploitation (65–80%), giving very fast convergence at lower dimensions. HHO-CHAOS and HHO-PSO show balanced ratios (30–50%). HHO-ADAP and HHO-Inertia shift gradually providing robust but slower convergence. HHO-ULTRA and HHO-GA hybrids favour exploration (60–85%), preserving diversity but with lower convergence speed.

Analysis of engineering problems

Engineering design problems involve optimizing complex systems with multiple constraints and objectives. These problems often require advanced optimization techniques to explore large solution spaces efficiently. Experimental analysis plays an important role in evaluating, effectiveness of different optimization algorithms in solving such problems [90]. In this research, ten constrained engineering design problems are selected and proposed SMA variants are evaluated on these problems along with standard HHO [13], WMA [24], OWMA [25], CMA-ES [93], EBOwithCMAR [14], SPS-L-SHADE-EIG [94], LSHADE_cnEpSin [95] and L-SHADE [96].

Three-bar truss problem (SPECIAL1)

The truss consists of three bars connected at joints, and the goal is to minimize the total material cost as shown in Fig. 70 [90]. The design variables include the length and cross-sectional area of the bars. The challenge is to balance the structural load-carrying capacity with the material used to minimize cost, while maintaining the truss’s strength and stability under applied loads. The problem involves both linear and nonlinear components in the design.

Three-bar truss problem [90].

Let us consider,

Minimize,

Subject to,

Range of variables = 0 \(\le\)\(t_{1}\) , \(t_{2}\) \(\le\) 1.

Here, l = 100 cm, P = 2KN/\(cm^{2}\), \(\sigma\) = 2 KN/\(cm^{2}\).

Table 22 shows the performance of different HHO hybrids and baseline algorithms on the three-bar truss problem. The lowest weight (≈263.8958) was precisely reached by HHO-Elite, HHO-PSO, HHO-ADAP and HHO-Inertia, all with zero or near-zero variance, confirming strong convergence reliability. HHO-GA and HHO-Chaos also reached values close to the optimum but exhibited slightly higher dispersion (standard deviation ≈0.38–0.99). HHO-ULTRA produced feasible results but with larger variance, reflecting weaker stability on this simple problem. EBOwithCMAR also matched the exact optimum with negligible spread, while CMA-ES, L-SHADE, and SPS-L-SHADE-EIG showed higher mean values and standard deviations, indicating less robustness.

Average time per run was very low for all hybrids (< 0.002 s), with HHO-Inertia being the fastest (0.000149 s). Classical baselines required significantly more time, e.g., WMA (0.594 s) and SPS-L-SHADE-EIG (0.451 s). Overall, the results confirm that HHO hybrids not only ensure precise convergence but also deliver highly efficient runtimes compared to established metaheuristics.

Speed Reducer Problem (SPECIAL2)

A speed reducer is a mechanical device used to decrease the speed of a motor while increasing the torque [90]. The problem is to minimize the cost of designing a speed reducer, while ensuring that it meets certain functional requirements, such as torque capacity, speed ratios, and durability. The design variables include the diameters, number of teeth, and material properties of the gears as shown in Fig. 71. Constraints are applied to ensure that the system operates within the physical limits of the gears.

Speed reducer problem [90].

Minimize \(\begin{gathered} f(\vec{t}) = 0.7854t_{1} t_{2} (3.3333t_{3}^{2} + 14.9334t_{3} - 43.0934) - 1.508t_{1} (t_{6}^{2} + t_{7}^{2} ) + 7.4777(t_{6}^{3} + t_{7}^{3} ) \hfill \\ + 0.7854(t_{4} t_{6}^{2} + t_{5} t_{7}^{2} ) \hfill \\ \end{gathered}\) (3).

Subject to,

Table 23 summarizes the results for the speed reducer design problem. The lowest value (≈2994.47) was exactly achieved by HHO-GA, HHO-PSO and baseline algorithms such as L-SHADE and SPS-L-SHADE-EIG, with extremely low or near-zero variance. HHO-GA delivered the most stable performance with negligible deviation (≈0.0018) and consistent median values. HHO-PSO also remained close to the optimum but showed slightly higher spread (σ ≈62.6). HHO-ADAP and HHO-Elite reached feasible solutions but with larger variances, indicating less stability under this constraint-heavy problem. HHO-Inertia failed to maintain robustness, producing high dispersion and outliers. WMA and CMA-ES performed poorly, with extremely large mean values and variance, showing difficulty in handling nonlinear constraints. L-SHADE family algorithms (L-SHADE, LSHADE-cnEpSin, SPS-L-SHADE-EIG) achieved exact optimal values with near-zero deviations that validates their strong baseline competitiveness.

Average time per run was lowest for HHO and HHO-Chaos (< 0.007 s), while HHO-Elite and HHO-ULTRA required higher runtimes (0.07 and 0.047 s respectively). Classical baselines like WMA and SPS-L-SHADE-EIG consumed significantly more time (> 0.45 s). Overall, HHO-GA and HHO-PSO emerged as the most effective hybrids for this problem, combining accuracy, robustness, and computational efficiency.

Pressure vessel design (SPECIAL3)

A pressure vessel is a container designed to hold gases or liquids at a high pressure as shown in Fig. 72 [90]. The problem involves determining the optimal thickness and material properties of the vessel to minimize its construction cost while ensuring it can withstand the specified internal pressure. Design variables include the vessel’s diameter, wall thickness, and material properties. Constraints typically include factors like maximum allowable stress and safety factors. The goal is to find the most cost-effective design that meets performance requirements.

Pressure vessel design [90].

Subject to,

Variable ranges are,

0 \(\le\) \(t_{1}\) \(\le\) 99; 0 \(\le\) \(t_{2}\) \(\le\) 99; 10 \(\le\) \(t_{3}\) \(\le\) 200; 10 \(\le\) \(t_{4}\) \(\le\) 200.

Table 24 presents the comparative performance on the pressure vessel design problem. The lowest best value was obtained by HHO-Chaos (5885.20) and the lowest mean value was achieved by HHO-Elite (5885.16) showing its strong average consistency. For the median, lowest value was achieved by LSHADE family demonstrating precise convergence. The most stable algorithm in terms of standard deviation was L-SHADE (σ ≈ 17.6), confirming its reliability. In terms of computational efficiency, the fastest runtime was observed for standard HHO (~ 0.0032 s), followed closely by HHO-Chaos (~ 0.0046 s).

Overall, the results indicate that while the L-SHADE family provided the most stable and precise convergence, HHO-Chaos produced the best single run, HHO-Elite delivered the strongest average performance and HHO was the fastest. These complementary outcomes demonstrate that the proposed hybrids, particularly HHO-Elite and HHO-Chaos, can deliver near-optimal solutions with competitive efficiency while the L-SHADE variants remain the most consistent performers.

In terms of computational efficiency, the lowest average runtime was obtained by standard HHO (0.0032 s), followed by HHO-Chaos (0.0046 s), both significantly faster than the advanced baselines. Hybrids such as HHO-GA (0.0077 s) and HHO-Elite (0.055 s) required slightly higher runtimes but still remained well under 0.1 s. By contrast, classical methods like SPS-L-SHADE-EIG (1.51 s) and WMA (1.89 s) consumed more than a second per run, showing that the proposed HHO variants are markedly more efficient.

Spring design (SPECIAL4)

The problem focuses on designing a spring (typically a compression or tension spring) that minimizes material usage (cost) while ensuring that it performs according to the required force–deflection characteristics. Design variables that include the wire diameter, spring diameter and number of coils are shown in Fig. 73. Constraints could include the spring’s required stiffness, maximum load, or deflection. The optimization involves balancing the spring’s performance with material efficiency.

Spring design problem [90].

Consider, \(\vec{s} = \left[ {s_{1} s_{2} s_{3} } \right] = \left[ {dDN} \right]\) (5).

Minimize, \(f(s) = \left( {s_{3} + 2} \right)s_{2} s_{1}^{2}\) (5.a).

Subject to,

Variable ranges, 0.005 \(\le\) \(s_{1}\) \(\le\) 2.00, 0.25 \(\le\) \(t_{2}\) \(\le\) 1.30, 2.00 \(\le\) \(s_{3}\) \(\le\) 15.0.

Table 25 presents the comparative performance on the spring design problem. The lowest best value was obtained by HHO-CHAOS (0.0126664), while the lowest mean and median values were consistently achieved by L-SHADE (0.0126671 and 0.0126653, respectively), confirming its precision and reliability. In terms of stability, L-SHADE (σ ≈ 5.4 × 10⁻⁶) was again the most consistent algorithm. Among the hybrids, HHO-GA and HHO-Elite provided strong averages with moderate variance (~ 0.001), whereas HHO-ULTRA showed weaker stability (σ ≈ 0.00174). Baselines such as CMA-ES failed completely with infeasible outputs, while WMA produced larger errors and high variability.

For computational efficiency, the fastest runtime was obtained by HHO-Inertia (0.0019 s), followed by HHO-CHAOS (0.0027 s) and standard HHO (0.0030 s), all substantially faster than advanced baselines. Hybrids such as HHO-GA (0.0051 s) and HHO-Elite (0.0089 s) required slightly higher runtimes but still remained under 0.01 s. In contrast, classical methods such as EBOwithCMAR (0.114 s), SPS-L-SHADE-EIG (0.189 s), and WMA (0.242 s) consumed much more time. Overall, the L-SHADE family provided the most stable and precise performance, HHO-CHAOS produced the best single run, and HHO-Inertia was the fastest.

Welded beam design (SPECIAL5)

The design of a welded beam involves optimizing its dimensions and material properties to minimize the weight while ensuring it can carry a specified load without excessive deflection or stress. The beam needs to be strong enough to support the load, and its deflection under the load must be within allowable limits. This problem requires balancing structural integrity with material efficiency and weight reduction. Figure 74 visualizes the welded beam design problem.

Welded beam design [90].

Let us consider,

Minimize,

Subject to,

Range of Variables = 0.1 \(\le\) \(t_{1}\) \(\le\) 2; 0.1 \(\le\) \(t_{2}\) \(\le\) 1; 0.1 \(\le\) \(t_{3}\) \(\le\) 10; 0.1 \(\le\) \(t_{4}\) \(\le\) 2.

Here,

Table 26 presents the comparative performance on the welded beam design problem. The lowest best value was jointly achieved by HHO-GA and L-SHADE (1.7257), highlighting their ability to reach strong optimal solutions. OWMA outperformed all other algorithms by delivering the lowest mean (1.8013) and median (1.8015), as well as the most stable results with a very small standard deviation (σ ≈ 0.0187). Among the proposed hybrids, HHO-PSO and standard HHO obtained competitive mean values (~ 1.90) with moderate variance while HHO-Elite showed reliable though slightly higher averages. HHO-Inertia and HHO-ULTRA were less stable, showing high deviations (σ > 0.55). Baselines such as CMA-ES failed with excessively large or infeasible results, and WMA performed poorly with higher means and deviations.

In terms of computational efficiency, the fastest runtime was observed for HHO-Inertia (0.0064 s), followed by standard HHO (0.0072 s) and HHO-ADAP (0.0095 s), all within milliseconds. Other hybrids such as HHO-PSO (0.0109 s) and HHO-CHAOS (0.0105 s) remained efficient. By contrast, advanced champion algorithms required significantly more time: L-SHADE (0.227 s), LSHADE-cnEpSin (0.255 s), SPS-L-SHADE-EIG (0.498 s), and OWMA (0.726 s), while WMA (1.162 s) and EBOwithCMAR (0.528 s) were the slowest. Overall, the results show that while OWMA offered the most stable and consistent averages, HHO-GA and L-SHADE produced the strongest best solutions, and HHO-Inertia achieved the fastest runtime.

Rolling element bearing design (SPECIAL6)

This problem deals with the design of a rolling element bearing, which is used to support rotating machinery and reduce friction between moving parts. The goal is to either maximize the bearing’s lifespan or minimize its cost, while satisfying constraints related to the bearing’s geometry, stress, deformation, and operational parameters. Design variables may include the bearing’s dimensions, materials, and the number of rolling elements (balls or rollers). Constraints are based on performance factors like load-carrying capacity and speed. Figure 75 visualizes the design considerations of the Rolling Element Bearing Design case.

Rolling element bearing design [90].

Maximize,

If,\(DIM \le 25.4mm\)

If, \(DIM \ge 25.4mm\).

Subject to,

Here, \(f_{c} = 37.91\left[ {1 + \left\{ {1.04\left( {\frac{1 - \varepsilon }{{1 + \varepsilon }}} \right)^{1.72} \left( {\frac{{f_{I} \left( {2f_{0} - 1} \right)}}{{f_{0} \left( {2f_{I} - 1} \right)}}} \right)^{0.41} } \right\}^{10/3} } \right]^{ - 0.3} \times \left[ {\frac{{\varepsilon^{0.3} \left( {1 - \varepsilon } \right)^{1.39} }}{{\left( {1 + \varepsilon } \right)^{1/3} }}} \right]\left[ {\frac{{2f_{I} }}{{2f_{I} - 1}}} \right]^{0.41}\)

\(DIM = 160;\dim = 90;B_{W} = 30;R_{I} = R_{0} = 11.033\); \(0.515 \le f_{I}\) and \(f_{0} \le 0.6\)

Table 27 presents the comparative performance on the rolling element bearing problem. The lowest best value was consistently achieved by the L-SHADE family and EBOwithCMAR (≈ –85,539.19), with LSHADE-cnEpSin and SPS-L-SHADE-EIG also reporting identical mean and median values (≈ –85,539.19). Among these, SPS-L-SHADE-EIG demonstrated the highest stability with an almost negligible standard deviation (≈ 2.9 × 10⁻11), confirming its precision. Within the proposed hybrids, HHO-PSO (best = –85,515.41, mean = –83,443.70, σ ≈ 862) and HHO-GA (best = –85,539.19, mean = –83,853.19, σ ≈ 1884) achieved competitive performance with strong consistency compared to other HHO variants. HHO-ULTRA and WMA performed very poorly, producing infeasible averages of 1011–1014 with extremely high deviations. CMA-ES also diverged yielding large infeasible values.

For computational efficiency, the fastest runtime was recorded by HHO-Inertia (0.0076 s), followed by HHO-PSO (0.0127 s) and HHO-CHAOS (0.0146 s). Other hybrids such as HHO (0.0170 s) and HHO-GA (0.0195 s) remained efficient, while HHO-ULTRA (0.0534 s) and HHO-Elite (0.0374 s) were moderately slower. In comparison, advanced baselines such as L-SHADE (0.266 s), LSHADE-cnEpSin (0.631 s), and SPS-L-SHADE-EIG (0.907 s) consumed significantly more time, with WMA (0.702 s) and EBOwithCMAR (0.611 s) also requiring higher runtimes. Overall, the results confirm that while the L-SHADE family and EBOwithCMAR delivered the most precise and stable performance, HHO-PSO and HHO-GA were the strongest hybrid performers, and HHO-Inertia provided the fastest runtime.

Multiple disk clutch brake design (SPECIAL7)

A multi-disk clutch brake is used in mechanical systems to engage or disengage components, transferring torque while maintaining size and efficiency. The problem involves designing a clutch that efficiently transfers torque, fits within specified size constraints, and operates smoothly without excessive wear. Design variables include the number of disks, material properties, dimensions of the disks, and other related components. The aim is to optimize the clutch’s performance while minimizing cost and ensuring durability. Figure 76 visualizes the design considerations of the Multiple Disk Clutch Brake Design.

Multiple disk clutch brake design [90].

Minimize,

Subject to;

Here,

Table 28 presents the comparative performance on the multiple disk clutch brake problem. The lowest best values were consistently achieved by HHO-Elite, HHO-GA, HHO-CHAOS, HHO-PSO, EBOwithCMAR and LSHADE-cnEpSin (≈0.38965), confirming their ability to converge to the known optimum. In terms of averages, HHO-GA and HHO-CHAOS provided the strongest performance with the lowest mean (0.389653) and median (0.389653), while also achieving near-zero variance (σ ≈ 10⁻1⁶) which highlight their remarkable stability. HHO-Elite was similarly competitive, producing near-identical best and mean values. HHO-PSO also converged close to the optimum but with slightly larger variance. HHO-ADAP, HHO-Inertia and HHO-ULTRA produced weaker averages and higher dispersions, whereas classical baselines like CMA-ES diverged, yielding significantly larger values.

In terms of computational efficiency, the fastest runtime was observed for standard HHO (0.0040 s), followed by HHO-Inertia (0.0102 s) and HHO-Elite (0.0116 s). Hybrids such as HHO-GA (0.0252 s) and HHO-CHAOS (0.0611 s) required moderately higher runtimes but still remained well under 0.1 s. By contrast, advanced algorithms including EBOwithCMAR (1.079 s), SPS-L-SHADE-EIG (1.462 s), and OWMA (1.370 s) consumed much more time, showing that the proposed HHO variants were markedly more efficient. Overall, the results confirm that while HHO-GA and HHO-CHAOS delivered the most stable and consistent solutions, HHO-Elite remained highly competitive, and standard HHO was the fastest in runtime.

Gear Train Design (SPECIAL8)

A gear train is a system of gears that transmit motion and torque. The goal in this design problem is to minimize errors in the gear ratio while respecting the size and number of teeth of the gears, as well as other physical limitations. Gear trains are crucial in machines where the precision of movement is important, such as in watches or transmission systems. Design variables include gear sizes, number of teeth, and material properties. Constraints include limitations on gear dimensions and operational requirements. Figure 77 visualizes the design considerations of the gear train design problem.

Gear train design [90].

Minimize,

Subject to; \(12 \le t_{1} ,t_{2} ,t_{3} ,t_{4} \le 60\) .

Table 29 presents the comparative performance on the gear train design problem.

The minimum value of 0 is achieved by HHO, HHO-Elite, HHO-GA, HHO-ADAP, HHO-PSO, HHO-ULTRA, as well as the baseline EBOwithCMAR, LSHADE-cnEpSin, SPS-L-SHADE-EIG and partially by HHO-Inertia (Best = 0) despite a slightly higher mean. HHO, HHO-Elite, HHO-ADAP, HHO-PSO and HHO-ULTRA also attained zero variance (σ = 0) and zero mean, indicating perfect convergence across all runs. HHO-GA achieved an extremely small mean (~ 1.71 × 10⁻3⁰) with negligible variance, reflecting near-ideal stability. SPS-L-SHADE-EIG and LSHADE-cnEpSin also maintained means on the order of 10⁻13–10⁻1⁶, confirming precision. CMA-ES and WMA struggled to converge reliably.

In terms of computational efficiency, the fastest runtimes were recorded by HHO-Inertia (0.00108 s), HHO-CHAOS (0.00145 s), and HHO-PSO (0.00166 s), with standard HHO (0.00221 s) and HHO-GA (0.00334 s) close behind. All hybrids remained under 0.013 s, making them highly efficient compared with classical baselines like SPS-L-SHADE-EIG (0.202 s) and OWMA (0.214 s). Overall, the results confirm that multiple HHO variants especially HHO-PSO, HHO-ADAP, HHO-GA, and HHO-Elite achieved exact global solutions with perfect stability and extremely low runtime, establishing them as both precise and computationally efficient for this benchmark.

Belleville spring design (SPECIAL9)

A Belleville Spring is a type of disc spring used in applications where high load capacity and limited deflection are required, such as in automotive suspension systems or pressure relief valves. The objective is to design the spring to minimize cost while ensuring it meets performance specifications related to load capacity, deflection, and stiffness. The design variables include the spring’s dimensions (such as disc thickness and diameter) and material properties. The constraints ensure that the spring performs within the desired range for load and deflection.

Table 30 presents the comparative performance on the Belleville spring design problem. The lowest best value was obtained by HHO-CHAOS (1.97949), followed closely by HHO-GA, HHO-Elite, HHO-PSO and the L-SHADE family (≈1.9796–1.9797). In terms of average performance, LSHADE-cnEpSin was the most precise, achieving identical best, mean, and median values (1.979674757) with an almost negligible variance (σ ≈ 1.1 × 10⁻15). Among the hybrids, HHO-GA provided the strongest mean and median consistency (mean ≈1.9846, σ ≈0.0099), while HHO-Elite and HHO-PSO also performed competitively. In contrast, several variants including HHO, HHO-Inertia, HHO-ADAP and HHO-ULTRA exhibited instability, producing unrealistically large average values due to divergence in some runs. Baselines such as CMA-ES and WMA failed to converge reliably, with excessively large means and deviations.

In terms of computational efficiency, the fastest runtime was observed for standard HHO (0.0035 s), followed by HHO-Inertia (0.0086 s) and HHO-PSO (0.0125 s). Other hybrids such as HHO-Elite (0.0166 s) and HHO-GA (0.0242 s) required slightly longer runtimes but still remained efficient under 0.03 s. By contrast, advanced baseline methods consumed substantially more time, with L-SHADE (0.427 s), LSHADE-cnEpSin (0.483 s), SPS-L-SHADE-EIG (0.938 s), and OWMA (1.178 s) all requiring significantly higher runtimes. Overall, the results confirm that while HHO-CHAOS achieved the lowest best value, LSHADE-cnEpSin was the most stable and precise, and standard HHO remained the fastest.

Cantilever Beam Design (SPECIAL10)

A cantilever beam is a beam fixed at one end and free at the other. The goal is to reduce total cost of beam while ensuring that it can carry a specified load without excessive deflection or stress. The design variables could include the beam’s dimensions (length and cross-sectional area) and material properties. Constraints typically involve ensuring that the beam can withstand the applied load without exceeding stress limits or deflecting beyond allowable limits. This problem is common in structural engineering applications. Figure 78 visualizes the design considerations of the cantilever beam design problem.

Cantilever beam design [90].

Let us consider, \(\vec{t} = \left[ {t_{1} t_{2} t_{3} t_{4} t_{5} } \right]\) (11).

Minimize, \(f(\vec{t}) = 0.6224(t_{1} + t_{2} + t_{3} + t_{4} + t_{5} ),\) (11.a).

Subject to, \(g(t) = \frac{61}{{t_{1}^{3} }} + \frac{37}{{t_{2}^{3} }} + \frac{19}{{t_{3}^{3} }} + \frac{7}{{t_{4}^{3} }} + \frac{1}{{t_{5}^{3} }} \le 1\) (11.b).

Variable ranges are, \(0.01 \le t_{1} ,t_{2} ,t_{3} ,t_{4} ,t_{5} \le 100\).

Table 31 presents the comparative performance on the cantilever beam design problem. The lowest best value was achieved by HHO-CHAOS (1.30319), slightly outperforming all other methods. However, in terms of averages, HHO-ADAP emerged as the most competitive, providing the lowest mean (1.30309), lowest median (1.30497), and smallest standard deviation (σ ≈ 0.00113), highlighting its superior stability. HHO-Elite also performed reliably with best = 1.30344 and moderate variance, while HHO-GA and HHO-PSO gave feasible results but with higher mean values (~ 1.314). By contrast, HHO-Inertia and especially HHO-ULTRA showed weak performance, with ULTRA producing large averages (≈3.8) and very high deviation. Among baselines, the L-SHADE family and EBOwithCMAR reached near-optimal best values (≈1.30345) but with higher mean and variance compared to the stronger hybrids, while CMA-ES and WMA failed with poor solutions.

In terms of computational efficiency, the fastest runtime was obtained by standard HHO (0.0041 s), closely followed by HHO-Inertia (0.0048 s) and HHO-PSO (0.0070 s). Hybrids such as HHO-Elite (0.0086 s) and HHO-ADAP (0.0099 s) were also efficient, whereas HHO-GA (0.0150 s) and HHO-CHAOS (0.0099 s) consumed more time but still remained under 0.02 s. By contrast, the champion baselines were significantly slower, with L-SHADE (0.195 s), LSHADE-cnEpSin (0.255 s), and SPS-L-SHADE-EIG (0.791 s) all-consuming far more runtime, and OWMA (0.748 s) also lagging. Overall, the results confirm that HHO-CHAOS achieved the best solution, HHO-ADAP offered the most consistent and stable performance, and standard HHO was the fastest.

Conclusion and future work

This study developed and evaluated seven hybrid variants of the Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO) algorithm HHO-Elite, HHO-PSO, HHO-GA, HHO-ADAP, HHO-CHAOS, HHO-Inertia and HHO-ULTRA across a wide benchmark suite and ten practical-world engineering design problems. The results clearly demonstrate that hybridization enhances the baseline HHO in terms of convergence efficiency, solution quality and robustness under constrained environments.

The comparative analysis revealed that HHO-Elite, HHO-GA and HHO-PSO also displayed strong and stable convergence, delivering competitive performance across a wide range of problems with fast execution times. HHO-ADAP showed balanced performance adapting effectively to varying problem complexities, though not always achieving the fastest convergence. HHO-CHAOS and HHO-Inertia showed mixed results occasionally reaching good solutions but often with higher variance and instability. HHO-ULTRA performed the weakest with higher mean values and poor stability thus reflects exploration-heavy behaviour without consistent convergence.

The engineering problem results highlight the complementary strengths of the proposed hybrids, as different variants proved particularly effective under varying structural and nonlinear constraints. Rather than a single dominant approach, the findings demonstrate that tailored hybridization strategies allow the algorithms to adapt effectively across diverse problem settings. The analysis of average time per run highlights that the proposed HHO-GA, HHO-Elite and HHO-PSO maintain computational efficiency while achieving high-quality solutions further validating suitability for real-world engineering design optimization.

The main contributions of this work are seven novel hybridization strategies of HHO, incorporating adaptive mechanisms, elite preservation, chaotic dynamics, genetic operators and swarm intelligence features. Second, the algorithms were rigorously validated across a large suite of benchmark functions with varied dimensions and ten diverse engineering design problems, demonstrating improvements in convergence speed, accuracy, and robustness. Third, the analysis of convergence dynamics and computational efficiency provided insights into the trade-offs between exploration and exploitation establishing HHO-GA, HHO-Elite and HHO-PSO as the most competitive hybrids while also clarifying the situational strengths of other variants.

Although the findings are promising, several open research questions remain, which define directions for future exploration. A key concerns the scalability of hybrids to large-scale optimization problems involving thousands of variables, where computational cost and memory efficiency become critical. Another key challenge is enabling adaptation to dynamic and uncertain optimization environments, where problem constraints and objectives evolve over time. Mult objective extensions also remain underexplored particularly in balancing convergence and diversity when dealing with conflicting goals. Theoretical analysis of why specific hybridization strategies succeed in particular landscapes is still lacking; addressing this gap would strengthen the interpretability of hybrid metaheuristics. Beyond classical engineering problems, extending hybrid HHO variants to data-driven domains such as machine learning, renewable energy scheduling and intelligent control systems presents another promising research direction.

In conclusion, this work demonstrates that hybrid HHO variants substantially advance the baseline algorithm by offering tailored strengths across different optimization landscapes. By addressing the identified open challenges, these hybrids can evolve into powerful versatile optimizers capable of solving increasingly complex real-world problems.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Tomar, V., Bansal, M. & Singh, P. Metaheuristic algorithms for optimization: A brief review. Eng. Proc. 59(1), 238 (2024).

Rajwar, K., Deep, K. & Das, S. An exhaustive review of the metaheuristic algorithms for search and optimization: Taxonomy, applications, and open challenges. Artif. Intell. Rev. 56(11), 13187–13257 (2023).

Rezk, H., Olabi, A. G., Wilberforce, T. & Sayed, E. T. Metaheuristic optimization algorithms for real-world electrical and civil engineering application: a review. Results Eng. 23, 102437 (2024).

Cui, E. H., Zhang, Z., Chen, C. J. & Wong, W. K. Applications of nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithms for tackling optimization problems across disciplines. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 9403 (2024).

El-Kenawy, E.-S. M., Eid, M. M., Saber, M. & Ibrahim, A. MbGWO-SFS: Modified binary grey wolf optimizer based on stochastic fractal search for feature selection. IEEE Access. 8, 107635–107649 (2020).

Grossmann, I. E. Global optimization in engineering design (Springer Science & Business Media, Berlin Heidelberg, 2013).

Cheng, Y. et al. Modeling and optimization for collaborative business process towards IoT applications. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2018(1), 9174568 (2018).

Wang, X., Choi, T.-M., Liu, H. & Yue, X. A novel hybrid ant colony optimization algorithm for emergency transportation problems during post-disaster scenarios. IEEE Trans. Syst., Man, Cybern.: Syst. 48(4), 545–556 (2016).

Nouiri, M., Bekrar, A., Jemai, A., Niar, S. & Ammari, A. C. An effective and distributed particle swarm optimization algorithm for flexible job-shop scheduling problem. J. Intell. Manuf. 29, 603–615 (2018).

Kennedy, James, and Russell Eberhart. (1995) “Particle swarm optimization.” In Proceedings of ICNN’95-international conference on neural networks, 4: 1942–1948.

Katoch, S., Chauhan, S. S. & Kumar, V. A review on genetic algorithm: past, present, and future. Multim. Tools Appl. 80, 8091–8126 (2021).

Mirjalili, S., Mirjalili, S. M. & Lewis, A. Grey wolf optimizer. Adv. Eng. Softw. 69, 46–61 (2014).

Deb, K., Sindhya, K. & Hakanen, J. Multi-objective optimization (CRC Press, Boca Raton, 2016).

Kumar, A., Misra, R. K., & Singh, D. (2017, June). Improving the local search capability of effective butterfly optimizer using covariance matrix adapted retreat phase. In 2017 IEEE congress on evolutionary computation (CEC) (pp. 1835–1842). IEEE.

Dong, Y., Zhang, S., Zhang, H., Zhou, X. & Jiang, J. Chaotic evolution optimization: A novel metaheuristic algorithm inspired by chaotic dynamics. Chaos, Solitons Fractals 192, 116049. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2025.116049 (2025).

Houssein, E. H. et al. Hybrid Harris hawks optimization with cuckoo search for drug design and discovery in chemoinformatics. Sci. Rep. 10, 14439 (2020).

Bohat, V. K., Hashim, F. A., Batra, H. & Elaziz, M. A. Phototropic growth algorithm: A novel metaheuristic inspired from phototropic growth of plants. Knowl. -Based Syst. 322, 113548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2025.113548 (2025).

Mohamed, M. I., Yousef, A. M. & Hafez, A. A. A novel metaheuristic optimizer GPSed via artificial intelligence for reliable economic dispatch. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 20258 (2025).

Jia, H., Zhou, X., Zhang, J. & Mirjalili, S. Superb fairy-wren optimization algorithm: A novel metaheuristic algorithm for solving feature selection problems. Clust. Comput. 28(4), 246 (2025).

Wang, X. Draco lizard optimizer: A novel metaheuristic algorithm for global optimization problems. Evol. Intel. 18(1), 10 (2025).

Wang, X. Fishing cat optimizer: a novel metaheuristic technique. Eng. Comput. 42(2), 780–833 (2025).

Etesami, R., Madadi, M., Keynia, F. & Arabpour, A. Gaussian combined arms algorithm: a novel meta-heuristic approach for solving engineering problems. Evol. Intel. 18(2), 1–36 (2025).

Ge, Y. et al. A novel metaheuristic optimizer based on improved adaptive guided differential evolution algorithm for parameter identification of a PEMFC model. Fuel 383, 133869 (2025).

Karimzadeh Parizi, M. & Keynia, F. Woodpecker mating algorithm: A novel nature-inspired optimization method (Elsevier, 2020).

Karimzadeh Parizi, M., Keynia, F. & Khatibi bardsiri, A.,. OWMA: An improved self-regulatory woodpecker mating algorithm using opposition-based learning and allocation of local memory for solving optimization problems. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 40(1), 919–946 (2021).

Karimzadeh Parizi, M., Keynia, F. & Khatibi Bardsiri, A. Woodpecker mating algorithm for optimal economic load dispatch in a power system with conventional generators. Int. J. Ind. Electron. Control Optim. 4(2), 221–234 (2021).

Zhang, J., Li, H. & Parizi, M. K. HWMWOA: A Hybrid WMA–WOA algorithm with adaptive cauchy mutation for global optimization and data classification. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Decis. Mak. 22(04), 1195–1252 (2023).

Gong, J. & Karimzadeh Parizi, M. GWMA: the parallel implementation of woodpecker mating algorithm on the GPU. J. Chin. Inst. Eng. 45(6), 556–568 (2022).

Parizi, M. K., Keynia, F. & Bardsiri, A. K. HSCWMA: A new hybrid SCA-WMA algorithm for solving optimization problems. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Decis. Mak. 20(02), 775–808 (2021).

Zhong, M. et al. A hierarchical multi-leadership sine cosine algorithm to dissolving global optimization and data classification: The COVID-19 case study. Comput. Biol. Med. 164, 107212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2023.107212 (2023).

Lu, C., Wei, Y. & Karimzadeh Parizi, M. Improved Sine Cosine algorithm for global optimization and medical data classification. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Decision Making. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219622025500774 (2025).

Li, S., Chen, H., Wang, M., Heidari, A. A. & Mirjalili, s. Slime mould algorithm: A new method for stochastic optimization. Future Gener. Computer Syst. 111, 300–323 (2020).

Abualigah, L. et al. Aquila optimizer: a novel meta-heuristic optimization algorithm. Computers Ind. Eng. 157, 107250 (2021).

Ahmadianfar, I., Heidari, A. A., Gandomi, A. H., Chu, X. & Chen, H. RUN beyond the metaphor: An efficient optimization algorithm based on Runge Kutta method. Expert Syst. Appl. 181, 115079 (2021).

Dorigo, M. & Stützle, T. Ant colony optimization: overview and recent advances (Springer International Publishing, Berlin Heidelberg, 2019).

Wolpert, D. H. & Macready, W. G. No free lunch theorems for optimization. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 1(1), 67–82 (1997).

Mirjalili, S. Evolutionary algorithms and neural networks. Stud. Comput. Intell. 780(1), 43–53 (2019).

Yang, X.-S. Nature-inspired optimization algorithms (Academic Press, Massachusetts, 2020).

Mao, M. & Gui, D. Enhanced adaptive-convergence in Harris’ hawks optimization algorithm. Artif. Intell. Rev. 57(7), 164 (2024).

Yang, T., Fang, J., Jia, C., Liu, Z. & Liu, Yu. An improved harris hawks optimization algorithm based on chaotic sequence and opposite elite learning mechanism. PLoS ONE 18(2), e0281636 (2023).

Rao, R. V. & Waghmare, G. G. A new optimization algorithm for solving complex constrained design optimization problems. Eng. Optimiz. 49(1), 60–83 (2017).

Li, Y., Wang, J., Zhao, D., Li, G. & Chen, C. A two-stage approach for combined heat and power economic emission dispatch: Combining multi-objective optimization with integrated decision making. Energy 162, 237–254 (2018).

Dhiman, G. & Kumar, V. Spotted hyena optimizer: A novel bio-inspired based metaheuristic technique for engineering applications. Adv. Eng. Softw. 114, 48–70 (2017).

Mirjalili, S. & Lewis, A. The whale optimization algorithm. Adv. Eng. Softw. 95, 51–67 (2016).

Mirjalili, S. Moth-flame optimization algorithm: A novel nature-inspired heuristic paradigm. Knowl.-Based Syst. 89, 228–249 (2015).

Mirjalili, S., Mirjalili, S. M. & Hatamlou, A. Multi-verse optimizer: A nature-inspired algorithm for global optimization. Neural Computing Appl. 27, 495–513 (2016).

Arora, S. & Singh, S. Butterfly optimization algorithm: A novel approach for global optimization. Soft. Comput. 23, 715–734 (2019).

Mirjalili, S. SCA: A sine cosine algorithm for solving optimization problems. Knowl.-Based Syst. 96, 120–133 (2016).

Mirjalili, S. The ant lion optimizer. Adv. Eng. Softw. 83, 80–98 (2015).

Mirjalili, S. et al. Salp swarm algorithm: A bio-inspired optimizer for engineering design problems. Adv. Eng. Softw. 114, 163–191 (2017).

Dhiman, G. & Kumar, V. Emperor penguin optimizer: a bio-inspired algorithm for engineering problems. Knowl.-Based Syst. 159, 20–50 (2018).

Mohammadi-Balani, A., Nayeri, M. D., Azar, A. & Taghizadeh-Yazdi, M. Golden eagle optimizer: A nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithm. Computers Ind. Eng. 152, 107050 (2021).

Al-Betar, M. A., Alyasseri, Z. A. A., Awadallah, M. A. & Doush, I. A. Coronavirus herd immunity optimizer (CHIO). Neural Computing Appl. 33(10), 5011–5042 (2021).

Khishe, M. & Mosavi, M. R. Chimp optimization algorithm. Expert Syst. Appl. 149, 113338 (2020).

Faramarzi, A., Heidarinejad, M., Stephens, B. & Mirjalili, S. Equilibrium optimizer: A novel optimization algorithm. Knowl.-Based Syst. 191, 105190 (2020).

Zhao, W., Wang, L. & Mirjalili, S. Artificial hummingbird algorithm: A new bio-inspired optimizer with its engineering applications. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 388, 114194 (2022).

Połap, D. & Woźniak, M. Red fox optimization algorithm. Expert Syst. Appl. 166, 114107 (2021).

Chou, J.-S. & Truong, D.-N. A novel metaheuristic optimizer inspired by behavior of jellyfish in ocean. Appl. Math. Comput. 389, 125535 (2021).

Dehghani, M. & Trojovský, P. Osprey optimization algorithm: A new bio-inspired metaheuristic algorithm for solving engineering optimization problems. Front. Mech. Eng. 8, 1126450 (2023).

Abdollahzadeh, B. et al. Puma optimizer (PO): a novel metaheuristic optimization algorithm and its application in machine learning. Clust. Comput. 27(4), 5235–5283 (2024).

Peraza-Vázquez, H., Peña-Delgado, A., Merino-Treviño, M., Morales-Cepeda, A. B. & Sinha, N. A novel metaheuristic inspired by horned lizard defense tactics. Artif. Intell. Rev. 57(3), 59 (2024).

Li, Z. et al. Tactical unit algorithm: A novel metaheuristic algorithm for optimal loading distribution of chillers in energy optimization. Appl. Therm. Eng. 238, 122037 (2024).

Cheng, J. & De Waele, W. Weighted average algorithm: A novel meta-heuristic optimization algorithm based on the weighted average position concept. Knowl.-Based Syst. 305, 112564 (2024).

Ghiaskar, A., Amiri, A. & Mirjalili, S. Polar fox optimization algorithm: a novel meta-heuristic algorithm. Neural Comput. Appl. 36(33), 20983–21022 (2024).

Yu, D., Ji, Y. & Xia, Y. Projection-iterative-methods-based optimizer: A novel metaheuristic algorithm for continuous optimization problems and feature selection. Knowl. -Based Syst. 326, 113978 (2025).

Elbaz, M., Alhag, S. K., Al-Shuraym, L. A., Moghanm, F. S. & Marie, H. S. Osedax-GAN: A novel metaheuristic approach for missing pixel imputation imagery for enhanced detection accuracy of freshwater fish diseases in aquaculture. Aquacult. Eng. 111, 102606 (2025).

Barba-Toscano, O., Cuevas, E., Escobar-Cuevas, H. & Islas-Toski, M. Cellular neighbors optimizer: a novel metaheuristic approach inspired by the cellular automata and agent-based modeling for global optimization. J. Supercomput. 81(8), 869 (2025).

Braik, M. & Al-Hiary, H. A novel meta-heuristic optimization algorithm inspired by water uptake and transport in plants. Neural Comput. Appl. 37, 1–82 (2025).

Zhang, Y., Liu, R., Wang, X., Chen, H. & Li, C. Boosted binary Harris hawks optimizer and feature selection. Eng. Computers 37, 3747–3772 (2021).

Utama, D. M. & Widodo, D. S. An energy-efficient flow shop scheduling using hybrid Harris hawks optimization. Bull. Elect. Eng. Inf. 10(1), 537–545 (2021).

Su, Y., Dai, Y. & Liu, Y. A hybrid parallel Harris hawks optimization algorithm for reusable launch vehicle reentry trajectory optimization with no-fly zones. Soft. Comput. 25, 10867–10884 (2021).

Gezici, H. & Livatyali, H. An improved Harris Hawks Optimization algorithm for continuous and discrete optimization problems. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 113, 104952 (2022).

Alwajih, R., Abdulkadir, S. J., Al Hussian, H., Aziz, N. & Al-Tashi, Q. Hybrid binary whale with Harris hawks for feature selection. Neural Comput. Appl. 34, 15447–15463 (2022).

Katib, I. & Ragab, M. Blockchain-assisted hybrid Harris hawks optimization based deep DDoS attack detection in the IoT environment. Mathematics 11(8), 1887 (2023).

Jiao, S., Wang, C., Gao, R., Li, Y. & Zhang, Q. Harris hawks optimization with multi-strategy search and application. Symmetry 13(4), 621 (2021).

Abba, S. I., Najashi, B. G., Rotimi, A., Musa, B. & Yimen, N. Emerging Harris Hawks Optimization based load demand forecasting and optimal sizing of stand-alone hybrid renewable energy systems – A case study. Results Eng. 12, 100260 (2021).

Alazab, M., Khurma, R. A., Castillo, P. A. & Abu-Salih, B. An effective network intrusion detection approach based on hybrid Harris Hawks and multi-layer perceptron. Egypt. Inf. J. 25, 100423 (2024).

Li, C., Zhou, J., Du, K., Armaghani, D. J. & Huang, S. Prediction of flyrock distance in surface mining using a novel hybrid model of Harris hawks optimization with multi-strategies-based support vector regression. Nat. Resour. Res. 32, 391–409 (2023).

Houssein, E. H. et al. Hybrid Harris hawks optimization with cuckoo search for drug design and discovery in chemoinformatics. Sci. Reports 10(1), 14439 (2020).

Abdel-Basset, M., Ding, W. & El-Shahat, D. A hybrid Harris Hawks optimization algorithm with simulated annealing for feature selection. Artif. Intell. Rev. 54(1), 593–637 (2021).

Houssein, E. H., Hosney, M. E., Oliva, D., Mohamed, W. M. & Hassaballah, M. A novel hybrid Harris hawks optimization and support vector machines for drug design and discovery. Comput. Chem. Eng. 133, 106656 (2020).

Kaveh, A., Rahmani, P. & Dadras Eslamlou, A. An efficient hybrid approach based on Harris Hawks optimization and imperialist competitive algorithm for structural optimization. Eng. Comput. 38, 1–29 (2021).