Abstract

Grain amaranth (Amaranthus hypochondriacus) is a climate-resilient pseudo-cereal with high nutritional value and stress tolerance. NAC transcription factors (TFs) are key regulators in plant development and environmental responses. Here, we performed a comprehensive genome-wide analysis of 70 NAC genes (AhypNACs), classified into 24 phylogenetic subfamilies. Gene structure analysis showed exon variation (1–7), and chromosomal mapping revealed uneven distribution, with 32 segmental, 5 tandem, and 32 transposed duplications. Promoter analysis identified diverse cis-regulatory elements linked to light, hormone signaling, and stress response. miRNA analysis suggested Ahyp-miR164a targets four NAC genes, indicating post-transcriptional control. Comparative genomics showed both conserved and lineage-specific expansions among Oryza sativa, Beta vulgaris, Arabidopsis thaliana, and Chenopodium quinoa. Transcriptome analysis across seven tissues and five stress conditions identified several condition-specific and multi-stress-responsive NAC genes, with AhypNAC17, AhypNAC23, and AhypNAC24 showing strong induction. RT-qPCR validation under drought stress confirmed early and sustained upregulation of AhypNAC23 and AhypNAC24, and downregulation of AhypNAC03 and AhypNAC70, supporting their functional roles in drought adaptation. This study provides key insights into the structural diversity, evolutionary patterns, and stress-regulatory roles of NAC TFs in A. hypochondriacus, laying the foundation for genetic improvement of stress-resilient cultivars.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The genus Amaranthus, derived from the Greek word meaning “eternal” or “everlasting,” encompasses species of significant agricultural and nutritional value. Among these, Amaranth, commonly known as Prince’s feather, is recognised as a promising pseudo-cereal and leafy vegetable. Unlike true cereals that store carbohydrates in the endosperm, grain Amaranth accumulates starch in the perisperm, justifying its classification as a pseudo-cereal1. Amaranth grains are nutritionally rich, offering high levels of essential micronutrients including iron, calcium, magnesium, β-carotene, folic acid, and vitamin C2. The seeds are particularly notable for their elevated protein content (~ 22.5%), substantial dietary fibre (~ 8%), and lysine content (0.73–0.84%), which significantly surpasses that of common cereals such as maize and wheat3. In addition to its nutritional benefits, amaranth leaves have demonstrated therapeutic potential by inhibiting the abnormal proliferation of breast, colon, and liver cancer cells, highlighting its value in dietary and medicinal contexts4.

Transcription factors are key regulatory proteins that modulate gene expression by binding to specific cis-acting elements in the promoter regions of target genes. These proteins orchestrate a wide range of physiological and developmental processes in plants, particularly in response to environmental cues5. Based on conserved DNA-binding domains, plant TFs are categorised into 58 families6, among them the most prominent families are NAC, MYB, AP2/ERF, HD-Zip, bZIP, WRKY, ARF, and others7. The NAC (NAM, ATAF1/2, and CUC2) family, in particular, represents one of the most prominent plant-specific transcription factor family, playing critical roles in diverse biological functions8.

The NAC family derives its name from three founding members: NAM (No Apical Meristem), ATAF1/2 (Arabidopsis Transcription Activator Factors), and CUC2 (Cup-shaped Cotyledon 2)9,10,11. Functionally, the NAM domain is vital for apical meristem formation in Petunia hybrida7, ATAF1/2 act as repressors in defence responses against necrotrophic fungal and bacterial pathogens12 and CUC2 is involved in embryogenesis, floral development, and shoot apical meristem formation in Arabidopsis thaliana10. Beyond these roles, NAC TFs have been implicated in the regulation of secondary cell wall biosynthesis13 shoot and root development14, organ boundary maintenance15, leaf senescence16, fruit ripening17, and cell cycle control18,19.

Genome-wide studies have identified a variable number of NAC genes across plant species, reflecting their evolutionary diversification and functional specialisation. For example, 117 NAC genes have been reported in Arabidopsis thaliana, 151 in Oryza sativa (rice), 152 in Glycine max (soybean), 220 in Gossypium hirsutum (cotton), 167 in Musa acuminata (banana), 82 in Nelumbo nucifera (lotus), 79 in Asparagus officinalis, 74 in Fragaria vesca (strawberry), and 289 in Saccharum spontaneum (sugarcane)20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27.

The recent availability of a high-quality, chromosome-level genome assembly for A. hypochondriacus28 has enabled comprehensive genome-wide analyses of key transcription factor families, including NAC. The present study systematically identifies and characterises the complete set of NAC genes in grain Amaranth, providing a detailed investigation of their structural features, phylogenetic relationships, conserved motifs, gene structures, physicochemical properties, subcellular localisation, transmembrane domains, and chromosomal distribution. Additionally, cis-regulatory elements were examined to infer potential regulatory mechanisms, and syntenic analyses were performed to explore evolutionary conservation. In silico expression profiling across various tissues and under multiple abiotic and biotic stresses identified several stress-responsive AhypNAC genes, of which four drought-inducible candidates were validated via RT-qPCR.

Collectively, this study offers comprehensive insights into the genomic organisation, evolutionary dynamics, and regulatory potential of the NAC gene family in grain amaranth. These findings establish a foundational framework for functional validation of stress-responsive NAC genes and pave the way for future efforts aimed at improving stress resilience and productivity in amaranth and related crops.

Results

Identification of NAC genes

A total of 70 NAC genes were identified in the Amaranthus hypochondriacus genome through a homology-based search using the PlantTFDB v5.0 database. Their identities were further confirmed by detecting conserved NAC-specific domains via NCBI’s Conserved Domain Database and Pfam. For consistency, the genes were renamed AhypNAC01 to AhypNAC70 based on their genomic locations (Table S1). These genes were unevenly distributed across the 16 chromosomes. The highest numbers were found on 1 and 3, each carrying nine genes (12.86%), followed by 4 with eight (11.43%) and 6 with seven (10%). Six genes (8.57%) were located on 2, 5, and 11, while 7 contained four (5.71%). Fewer genes were mapped to 9, 12, and 14 (three each, 4.29%), and to 8 and 10 (two each, 2.86%). The lowest counts were on 15 and 16, with just one gene each (1.43%). Notably, chromosome 13 had no NAC genes. This uneven pattern, especially the absence on chromosome 13, may be linked to genetic, structural, or evolutionary features that shaped the NAC gene arrangement in A. hypochondriacus.

Motif, domain and gene structure analysis

All NAC proteins identified in Amaranthus hypochondriacus shared a conserved NAC domain at the N-terminal, which is crucial for DNA binding. Most of these proteins contained the five typical subdomains (A–E), with a few exceptions. For instance, AhypNAC65 lacked subdomain E, while AhypNAC14, AhypNAC44, AhypNAC46, and AhypNAC58 missed both A and B (Fig. S1). Motif analysis using MEME revealed 10 conserved regions, ranging from 15 to 50 amino acids in length. Motifs 1 to 5 appeared in most proteins, suggesting core functions, whereas motifs 6, 7, and 10 were found only in specific subgroups. In contrast, motifs 8 and 9 were scattered across different clusters. AhypNAC03 contained just one motif, while a group of 12 genes exhibited six distinct motifs each, indicating structural and possibly functional diversity (Fig. S2). To explore evolutionary relationships, a neighbor-joining (NJ) tree was constructed using the complete NAC gene set, dividing the genes into nine distinct subgroups (Fig. 1A). The clustering was consistent with motif arrangements, particularly those located at the C-terminal (Fig. 1B). Analysis of gene structures revealed variation in exon–intron organization (Fig. 1C). All genes possessed at least two exons and one intron. The majority (around 71%) displayed a typical structure of three to four exons. A simpler structure with two exons was seen in nine genes, while a more complex organization of six exons was found in seven, including AhypNAC25, AhypNAC28, and AhypNAC66. Additionally, single instances of genes with seven and one exon were observed in AhypNAC20 and AhypNAC43, respectively. Genes within the same phylogenetic group generally shared similar structures, highlighting evolutionary conservation (Fig. 1D, E).

Structural and evolutionary characterization of NAC genes in Amaranthus hypochondriacus. (A) Phylogenetic tree of 70 AhypNAC proteins constructed using the maximum likelihood method. (B) Conserved motif distribution; each coloured box represents a distinct motif, and black lines indicate non-conserved regions. (C) Predicted NAC domains highlighted in green. (D) Gene structure showing coding sequences (CDS) in yellow and untranslated regions (UTRs) in green. (E) Legend for motif and gene structure representations. Nucleotide and amino acid lengths are indicated by scale bars.

Chromosomal distribution, syntenic relationships, orthologous clustering, and evolutionary dynamics of NAC genes

The 70 AhypNAC genes were unevenly distributed across 16 chromosomes, with the highest numbers on chromosomes 1 and 3 (9 genes each), followed by 4 (8) and 6 (7). Chromosomes 13 lacked NAC genes entirely (Fig. 2). Gene duplication contributed significantly to NAC expansion: 32 genes originated from dispersed duplications, 32 from segmental or whole-genome duplication, and five from tandem duplications. One gene (AhypNAC28) likely arose via proximal duplication. Segmental duplications (17 gene pairs) had Ka/Ks ratios between 0.12 and 0.43, suggesting purifying selection (Fig. S2, Table S2-S3).

Synteny analysis revealed conserved NAC loci between A. hypochondriacus and four species. With C. quinoa, 104 syntenic NACs were found, predominantly on chromosomes 1 and 2. Comparisons with A. thaliana identified 46 syntenic genes, with strongest matches from chromosome 2. Moderate conservation was observed with O. sativa (14 genes), while B. vulgaris shared 21 genes, mainly from chromosome 2. Chromosomes 13 and 16 showed no conservation across species, reflecting divergence (Fig. 3).

Orthologous clustering using OrthoVenn3 across five species (A. hypochondriacus (Ahyp), A. thaliana (At), O. sativa (Os), B. vulgaris (Bv), C. quinoa (Cq)) identified 81 orthogroups. A. hypochondriacus shared 27 core NAC genes with all species, suggesting conserved ancestral functions. Notably, three genes were uniquely shared with C. quinoa, indicating a closer evolutionary relationship. No NAC genes were exclusive to Ahyp alone. O. sativa displayed the highest number of species-specific orthologs (18), consistent with monocot-dicot divergence. A total of 76 singleton genes were identified, including 18 from Ahyp, suggesting possible lineage-specific innovations (Fig. 4A, B).

Comparative genomic and evolutionary analysis of NAC transcription factors across five plant species: Amaranthus hypochondriacus (Ahyp), Arabidopsis thaliana (At), Oryza sativa (Os), Beta vulgaris (Bv), and Chenopodium quinoa (Cq). (A) Venn diagram showing shared and unique orthogroups among the five species, highlighting conserved and lineage-specific NAC gene sets. (B) Upset plot illustrating the intersections of orthologous groups across species, providing insight into cluster-level conservation and divergence. (C) Unrooted phylogenetic tree constructed using the maximum likelihood method (JTT + CAT model), depicting evolutionary relationships among representative NAC orthogroups. (D) Ultrametric phylogenetic tree generated by CAFE, showing gene family expansion (magenta) and contraction (blue) events across lineages, with numeric values indicating the number of affected orthogroups.

Phylogenetic analysis using the maximum likelihood method (JTT + CAT model) revealed that A. hypochondriacus is most closely related to C. quinoa (bootstrap support = 0.890), with both species clustering within the Caryophyllales clade. B. vulgaris was more distantly related, while A. thaliana and O. sativa were placed in more basal positions, with the latter being the most divergent, reflecting its monocot origin (Fig. 4C).

Gene family evolution analysis using CAFE (Computational Analysis of gene Family Evolution) indicated dynamic changes. C. quinoa showed the highest expansion (+ 2 orthogroups), A. thaliana showed moderate expansion (+ 1), while A. hypochondriacus and O. sativa each exhibited contraction in two orthogroups. These patterns highlight lineage-specific gene gains or losses, likely driven by adaptive evolution or genome restructuring (Fig. 4D).

Phylogenetic analysis

A phylogenetic tree was constructed using 272 NAC protein sequences from Amaranthus hypochondriacus (AhypNAC—70), Arabidopsis thaliana (ANAC—105), and Oryza sativa (OsNAC—97), employing the maximum likelihood method (Jones-Taylor-Thornton (JTT) model) with 1000 bootstrap replicates. The NAC proteins clustered into 24 clades, highlighting both conserved and species-specific groups. Clade I comprised seven divergent NACs, including AhypNAC14, ANAC095, and OsNAC134, which lacked strong subfamily assignments and may represent fast-evolving genes. Clades II (ANAC063), III (Oryza-specific NAC 1), and IV (ATAF-like) included conserved regulators of stress responses, with Clade IV featuring ANAC023/024 and their orthologs. Clade V (ANAC001) and VI (ANAC077-Ortholog) consisted of evolutionarily preserved pairs. Clade VII (ONAC8-like) and VIII (TIP) were linked to development and membrane trafficking. Clade IX (ANAC084-like) and X (ANAC097-like) retained conserved Arabidopsis sequences, while Clade XI (SENU5), anchored by ANAC083, included 13 genes like OsNAC118–120 and AhypNAC59, associated with oxidative stress regulation (Fig. 5).

Phylogenetic tree of NAC proteins from A. hypochondriacus, A. thaliana, and O. sativa constructed using the maximum likelihood method (JTT model, 1,000 bootstraps). The 272 proteins clustered into 24 clades, including known and novel subfamilies. Coloured branches represent subgroups; internal nodes show bootstrap values, reflecting evolutionary relationships and lineage-specific diversification.

Clade XII, with AhypNAC33 and AhypNAC57, appeared unique to A. hypochondriacus. Clade XIII and Clade XIV contained canonical regulators like ANAC008. Clade XV (TERN) included TM-NACs with membrane localization. Clade XVI (ONAC022-like) was broadly conserved, possibly regulating development and senescence. Clade XVII (NAP), containing ANAC029 and its amaranth homologs, was associated with leaf aging and hormonal signaling. Clade XVIII (AtNAC3), centered on ANAC019, grouped AhypNAC40 and AhypNAC32 likely functioning in abiotic stress and senescence. Clade XIX (ATAF) included 15 genes from all three species, including stress-linked repressors like ANAC002 and OsNAC075. Clade XX (ANAC011), with 19 members, was broadly conserved, possibly involved in developmental regulation. Clade XXI (NAC2), XXII (OsNAC7-like), and XXIII (NAM) contained developmental regulators involved in root and shoot development. Clade XXIV (NAC1) was the largest, with 28 members, including NACs involved in auxin signaling and organogenesis, supporting its functional importance across species.

Physiochemical properties, subcellular localisation and transmembrane helices

To assess functional diversity within the AhypNAC protein family, 70 NAC proteins were analyzed using the Multiple Protein Profiler and TMHMM tools. The assessment included protein length, molecular weight (MW), isoelectric point (pI), hydropathicity (GRAVY), aliphatic and instability indices, aromaticity, net charge at pH 7.0, subcellular localization, and potential transmembrane domains. Protein lengths ranged from 65 (AhypNAC03) to 634 amino acids (AhypNAC67), with corresponding MWs of 7.75 to 70.27 kDa. The predicted pI values varied between 4.51 and 9.93, grouping 34 proteins as acidic (pI < 6.5), 11 as near-neutral (6.5–7.5), and 25 as basic (pI > 7.5), indicating charge diversity under physiological conditions. All proteins exhibited negative GRAVY values (− 1.183 to − 0.16), confirming their hydrophilic nature. The aliphatic index ranged from 42.43 to 88.49, while instability indices spanned 23.90 to 77.05, suggesting that 41 proteins are potentially unstable under in vitro conditions. Aromaticity values remained low (0.05–0.15), and net charge fluctuated widely (− 35.51 to + 11.67), implying differences in electrostatic properties and interaction capabilities. Subcellular localization prediction placed 64 proteins in the nucleus, consistent with their expected roles as transcription factors. Six proteins were predicted to localize to organelles, including the chloroplast (AhypNAC35, 46, 54) and endomembrane system (AhypNAC25, 45, 67) (Table 1). In addition, TMHMM analysis identified transmembrane helices in six proteins, suggesting possible involvement in membrane-associated functions (Table S4).

Cis-Regulatory elements and miRNA-mediated regulation of NAC genes

To explore transcriptional regulation of the 70 AhypNAC genes, we analyzed their 2000 bp upstream promoter regions and identified over 1700 cis-acting elements classified into 20 functional categories. Light-responsive elements were most prevalent (902 instances; 51.84%), including G-box, GATA-motif, Sp1, and TCT-motif, suggesting light-mediated control of NAC expression in A. hypochondriacus. Hormone-responsive motifs were also abundant: jasmonate-related elements (TGACG and CGTCA) occurred 152 times (8.74%), abscisic acid-related ABRE motifs appeared 125 times (7.18%), while motifs for gibberellin (3.22%), auxin (2.6%), and salicylic acid (2.59%) were also detected. Stress-related elements, such as anaerobic response elements (AREs, 100 instances), TC-rich repeats, and LTR motifs, indicate potential roles in hypoxia and cold stress adaptation. Developmental regulatory motifs like CAT-box (meristem activity), GCN4 (endosperm-specific), and MSA-like elements (cell cycle) were also present. Additionally, 86 MYB-binding motifs (4.94%) were identified, indicating possible co-regulation by MYB and NAC transcription factors (Fig. 6A, B).

To investigate post-transcriptional control, we predicted miRNA targets and identified Ahyp-miR164a as a conserved regulator of four NAC genes—AhypNAC02, AhypNAC10, AhypNAC56, and AhypNAC61. All interactions were cleavage-based, with binding sites located within the coding regions (569–703 bp). Expectation values ranged from 0.5 to 3.0 and UPE scores from 7.49 to 17.82, indicating stable interactions (Table S5). These results suggest miR164a-mediated fine-tuning of NAC gene expression in stress or development-related pathways.

Comprehensive expression profiling and qPCR validation of AhypNAC genes

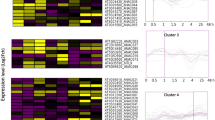

Comprehensive transcriptome analysis of 70 AhypNAC genes across seven tissues and five stress conditions revealed distinct expression signatures, classified into eight co-expression clusters (I–VIII), suggesting functional divergence in development and stress response in A. hypochondriacus. In cotyledons, AhypNAC51, 17 (Cluster I), and 31 (Cluster II) exhibited strong expression, while AhypNAC03 (III), 21 (III), 02 (IV), 16 (VIII), 58 (VIII), 59 (VIII), and 60 (III) showed low expression levels. Flowers showed high expression of AhypNAC68 (II) and 31 (II), with AhypNAC11 (III), 21 (III), and 05 (IV) expressed at lower levels. In pigmented red stem, AhypNAC17 (I) was highly expressed, while AhypNAC11 (III) showed moderately reduced expression. During the pre-linear stage, AhypNAC86 (not listed, possibly AhypNAC68) and 31 (II) were prominent, whereas AhypNAC03 (III), 11 (III), 60 (III), and 02 (IV) were less expressed. In the root tissue, genes in Cluster IV, such as AhypNAC06, 04, and 65, showed high expression, whereas AhypNAC69 (V), 19 (V), and 13 (V) were minimally expressed. In seeds, AhypNAC68 (II) and 31 (II) were again strongly expressed, while AhypNAC11 (III), 50 (III), and 02 (IV) showed reduced levels. Stem-specific expression was observed for AhypNAC38 (VIII) and 63 (VIII), while AhypNAC03 (III), 13 (V), and 19 (V) remained low (Fig. 7A, Table S6).

Heatmap showing log₂ fold-change expression of 70 AhypNAC genes across eight tissues and five stress conditions in Amaranthus hypochondriacus. (A) Genes are grouped into eight clusters (I–VIII) based on expression similarity. Red and blue indicate high and low expression, respectively. Top colour bar marks sample type: green (tissue) and yellow (stress). (B) qRT-PCR validation of AhypNAC03, AhypNAC70, AhypNAC23 and AhypNAC24 under different water stress.

Under drought stress, Cluster I genes (AhypNAC23, 24, 32) were highly expressed, while AhypNAC03 (III) and 70 (IV) were downregulated. In salt stress, AhypNAC06 (IV) and 51 (I) were induced, while genes such as AhypNAC69 (V), 19 (V), 13 (V), 38 (VIII), 63 (VIII), and 66 (VIII) were suppressed. Waterlogging strongly upregulated AhypNAC17 (I), 32 (I), and 69 (V), with downregulation of AhypNAC11 (III), 39 (VIII), 58 (VIII), and 59 (VIII). In bacterial infection, genes from Clusters I and IV such as AhypNAC17, 65, and 69 (V) were upregulated, while AhypNAC15 (VII) and 25 (VI) were suppressed. Insect herbivory induced AhypNAC17 (I) and 65 (IV), while AhypNAC25 (VI) was downregulated. Hierarchical clustering revealed functional modules: Clusters I–II encompassed highly expressed genes across both stress and developmental contexts, while Clusters V–VIII included genes with more specialized or suppressed expression. These transcriptional patterns underscore the regulatory versatility of AhypNAC genes and identify core candidates for further functional characterization under environmental and developmental contexts.

To validate in silico predictions, four AhypNAC genes were analyzed by RT-qPCR in the drought-tolerant genotype A. hypochondriacus “Annapurna” under severe water deficit (10% irrigation). AhypNAC23 showed strong early induction (~ 21-fold at 15 days) that declined to ~ 3-fold by 30 days, suggesting a transient drought response. AhypNAC24 remained stably upregulated (~ 3-fold), indicating sustained activation. Conversely, AhypNAC03 declined from 2.1-fold to 0.25-fold, and AhypNAC70 remained suppressed, implying negative regulation under prolonged drought. These results support the roles of AhypNAC23 and AhypNAC24 as potential positive regulators of drought tolerance (Fig. 7B).

Discussion

The NAC TF family constitutes one of the largest and most functionally diverse gene families in plants, playing pivotal roles in development, stress response, and senescence regulation14. In this study, we identified and characterized 70 NAC genes (AhypNACs) in Amaranthus hypochondriacus, a climate-resilient pseudo-cereal, and performed a genome-wide analysis of their structural, evolutionary, and expression features. The number of NAC genes in A. hypochondriacus is comparable to that in Arabidopsis thaliana (150), Oryza sativa (75), Capsicum annuum (104), and Solanum lycopersicum (88), Asparagus officinalis (85), Fagopyrum tataricum (80) suggesting a conserved repertoire across angiosperms20,25,29,30,31. Uneven chromosomal distribution—with no NAC genes found on chromosome 13 alongside identification of 32 segmentally duplicated and five tandemly duplicated genes indicates that gene duplication events have been key drivers of NAC expansion, as also observed in Glycine max32, Beta vulgaris33, and Chenopodium quinoa34. Gene structure analysis showed variation in exon number (1–7), with most genes containing 3–4 exons, consistent with patterns in Brassica napus35 and Triticum aestivum36. Promoter analysis revealed a predominance of light-responsive cis-elements (~ 52%), along with abundant hormone- and stress-related motifs, particularly ABA and jasmonate elements. This suggests potential cross-talk between light signaling and abiotic stress responses, a pattern also reported in Arabidopsis20 and Capsicum annuum29. Phylogenetic and orthologous clustering classified AhypNACs into 24 clades, with the OsNAC7-like group showing lineage-specific expansion, indicative of Amaranthaceae specific adaptations. Synteny analysis revealed a high degree of conservation with C. quinoa, supporting close evolutionary ties within the Amaranthaceae–Chenopodiaceae clade. The presence of A. hypochondriacus-specific orthogroups further implies species-specific functional diversification, while the relatively fewer singletons in A. hypochondriacus versus O. sativa suggests reduced NAC gene turnover in dicots. Subcellular localization predicted that most AhypNAC proteins are nuclear, consistent with their role as TFs. However, six genes encoding transmembrane domains likely represent membrane-bound NACs (NTLs), similar to those involved in ER stress signaling in A. thaliana20.

Transcriptome profiling across eight tissues and five stress conditions revealed diverse spatial and temporal expression signatures, grouped into eight co-expression clusters. Tissue-specific expression of genes like AhypNAC68 and AhypNAC31 (flower/seed) and AhypNAC06 and AhypNAC65 (root) points to specialized developmental functions. Stress-induced expression analysis revealed that AhypNAC23, AhypNAC24, and AhypNAC32 were strongly upregulated under drought, while AhypNAC17 and AhypNAC69 were induced across multiple stress conditions (salt, bacterial, insect, and waterlogging), suggesting their role as central regulators in the stress response network. Similar multi-stress NAC regulators have been reported in Musa acuminata23 and Zea mays37. RT-qPCR validation under drought stress further confirmed the transcriptomic findings. AhypNAC23 exhibited strong early induction (~ 21-fold at 15 days), while AhypNAC24 showed sustained upregulation, aligning with drought-responsive patterns reported for AmNAC24 in Ammopiptanthus mongolicus38, which is implicated in ROS scavenging through upregulation of antioxidant enzymes39. The downregulation of AhypNAC03 and AhypNAC70 under prolonged drought mirrors findings in peanut, where AhNAC3 homologs regulate downstream drought-related genes40. Together, these results highlight the functional divergence and regulatory complexity of NAC genes in A. hypochondriacus, offering valuable candidates for stress-resilient crop improvement. Notably, the identified drought- and multi-stress-responsive NACs particularly AhypNAC17, AhypNAC23, and AhypNAC24 serve as promising targets for future CRISPR-Cas9-based gene editing and transgenic overexpression assays. These approaches will be essential for functionally validating candidate NACs and translating these findings into practical applications for molecular breeding and the development of climate-resilient amaranth cultivars.

Conclusion

In this study, 70 NAC transcription factor genes were identified in Amaranthus hypochondriacus and comprehensively analysed for their chromosomal distribution, gene structure, duplication patterns, phylogenetic classification, and regulatory features. Expression profiling across various tissues and five abiotic and biotic stress conditions, supported by RT-qPCR validation, revealed key drought-responsive genes including AhypNAC23, AhypNAC24, AhypNAC03, and AhypNAC70. Predictions of transmembrane domains and miRNA interactions, particularly with Ahyp-miR164a, indicate multilayered regulatory control. These findings suggest that several AhypNAC genes play important roles in drought and multi-stress tolerance. This work offers a valuable genomic resource for future functional studies and provides a strong foundation for CRISPR-Cas9-based gene editing or overexpression assays aimed at developing climate-resilient amaranth cultivars through molecular breeding.

Materials and methods

Identification of NAC genes

The genome, protein, coding sequences, and annotation files of A. hypochondriacus were downloaded from Phytozome (https://phytozome-next.jgi.doe.gov/) submitted under Phytozome genome ID: 45941. To identify the NAC genes in the amaranth genome, the downloaded protein sequences were subjected to a sequence similarity search against the PlantTFDB v5.0 (https://planttfdb.gao-lab.org/download.php)6. The identified NAC protein sequences were further validated in silico to ensure the presence of the NAC domain using the NCBI Conserved Domain Database (CDD)42, InterProScan43 and the Pfam protein domain database44.

Sequence alignment, phylogenetic relationships, conserved motifs and gene structures

NAC protein sequences of A. hypochondriacus, A. thaliana (https://www.arabidopsis.org/) and O. sativa(https://phytozome-next.jgi.doe.gov/info/Osativa_v7_0) were aligned using MUSCLE (MEGA v11.0.13)45. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the maximum likelihood method (JTT model, 1000 bootstraps) and visualized with iTOL46. Conserved motifs were identified using MEME (maximum motifs = 10), and gene structures were extracted from GFF files and visualized using TBtools47.

Chromosomal mapping, synteny, duplication, and orthologous cluster analysis

NAC protein sequences of A. hypochondriacus, A. thaliana (https://www.arabidopsis.org/) and O. sativa(https://phytozome-next.jgi.doe.gov/info/Osativa_v7_0) were aligned using MUSCLE (MEGA v11.0.13)45. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the maximum likelihood method (JTT model, 1000 bootstraps) and visualized with iTOL46. Conserved motifs were identified using MEME (maximum motifs = 10), and gene structures were extracted from GFF files and visualized using TBtools47.

Physiochemical properties, subcellular localisation, and transmembrane helices prediction

The physiochemical properties of the identified NAC proteins were identified using Multiple Protein Profiler v1.0.48, subcellular localisation was predicted with BUSCA49 while transmembrane helices were identified using TMHMM v2.050 highlighting potential membrane-associated NACs.

Cis-Regulatory elements and miRNA analysis

The Promoter regions (2000 bp upstream) of AhypNAC genes were analyzed using PlantCARE51 to identify cis-acting regulatory elements, with visualization via TBtools. To explore post-transcriptional regulation, miRNA–NAC interactions were predicted using psRNATarget52, employing A. hypochondriacus specific mature miRNAs from Martínez Núñez et al.53, revealing potential miRNA binding sites under default parameters, including an expectation score of ≤ 3.

RNA-seq data download and expression analysis

RNA-seq datasets corresponding to various stress conditions in Amaranth were retrieved from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) submitted under Bio Projects PRJNA263128 and PRJNA65409. These include samples from pre-linear stage (SRR1598909), stem (SRR1598910), flower (SRR1598911), root (SRR1598913), cotyledons (SRR1598915), seed (SRR1598916) and pigmented red stem (SRR172680), drought stress (SRR1598914), salt stress (SRR183483), bacterial infection (SRR172679), waterlogging (SRR172677), insect herbivory (SRR172676). Transcript abundance for NAC genes was quantified using Salmon (v1.9.0)43 in quasi-mapping-based mode, with the NAC coding sequences as the reference transcriptome. The quantification outputs were imported and summarised using the tximport package in R, followed by differential gene expression analysis using DESeq2. A variance-stabilising transformation was applied to normalise the expression values. Heatmaps were generated in R using the pheatmap package to visualise the relative expression patterns of 70 NAC genes across five abiotic and biotic stress conditions and seven tissues. This approach enabled the identification of condition-specific upregulation and downregulation of NAC genes involved in stress responses.

Plant material and drought stress treatment

Seeds of Amaranthus hypochondriacus genotype “Annapurna” were obtained from the National Gene Bank at ICAR–NBPGR, New Delhi, under the accession number IC42258-1. This released cultivar was sourced from the national gene bank to ensure authenticity. Plants were grown under controlled greenhouse conditions (25 ± 1 °C, 16 h light/8 h dark) at ICAR-NBPGR, New Delhi. After 30 days, uniform seedlings at the four-leaf stage were transferred to pots containing a coco peat: vermiculite mixture (2:1). Drought stress was imposed using the gravimetric method described by Imakumbili et al. (2021)54, with water regimes of 100%, 60%, 30%, and 10% field capacity to simulate control, moderate, severe, and water-deficit conditions, respectively. Leaf samples were harvested at 0, 15, and 30 days post-treatment in three biological replicates, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at –80 °C for RNA extraction.

RNA isolation, cDNA preparation and RT-qPCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from drought-stressed leaf tissues using the RNeasy® Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Single-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using 1 µg of RNA with the Verso cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Scientific). Gene-specific primers were designed using Primer355 and validated by agarose gel electrophoresis. Actin (Accession No.: KJ634809) was used as the internal reference gene. RT-qPCR was conducted on a BIO-RAD CFX96 system using SYBR Green chemistry under the following conditions: 95 °C for 4 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 20 s, 58 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 20 s. Each reaction included two biological and three technical replicates. Relative expression levels were calculated using the 2–ΔΔCT method56, and fold changes were visualised using ggplot2 in R with error bars representing mean ± SD.

Data availability

The dataset of 70 identified AhypNAC gene sequences (genes including promoter region and the encoded protein) is available for download in FASTA format from FigShare at https://figshare.com/s/cf4aedbf2e95b3959690.

References

Kumari, A. et al. Genetic resources and breeding approaches for improvement of amaranth (Amaranthus spp.) and quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa). Front. Nutr. 10, 1129723. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2023.1129723 (2023).

Hongyan, L. et al. Characterization of phenolics, betacyanins and antioxidant activities of the seed, leaf, sprout, flower and stalk extracts of three Amaranthus species. J. Food Compos. Anal. 37, 75–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2014.09.003 (2015).

Gupta, S., Lakshmia, A. J., Manjunath, M. N. & Prakash, J. Analysis of nutrient and anti-nutrient content of underutilized green leafy vegetables. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 38, 339–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2004.06.012 (2005).

Bressani, R., Sánchez-Marroquín, A. & Morales, E. Chemical composition of grain amaranth cultivars and effects of processing on their nutritional quality. Food Rev. Int. 8, 23–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/87559129209540928 (1992).

Meshi, T. & Iwabuchi, M. Plant transcription factors. Plant Cell Physiol. 36, 1405–1420 (1995).

Jin, J. P., Zhang, H., Kong, L., Gao, G. & Luo, J. C. PlantTFDB 3.0: A portal for the functional and evolutionary study of plant transcription factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D1182–D1187. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkt1016 (2014).

Liu, G. S., Li, H. L., Grierson, D. & Fu, D. Q. NAC transcription factor family regulation of fruit ripening and quality: A review. Cells 11, 525. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11030525 (2022).

Lv, S. et al. Large-scale cloning and comparative analysis of TaNAC genes in response to stripe rust and powdery mildew in wheat (Triticum aestivum). Genes 11, 1073. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11091073 (2020).

Souer, E., van Houwelingen, A., Kloos, D., Mol, J. & Koes, R. The no apical meristem gene of Petunia is required for pattern formation in embryos and flowers and is expressed at meristem and primordia boundaries. Cell 85, 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81093-4 (1996).

Aida, M., Ishida, T., Fukaki, H., Fujisawa, H. & Tasaka, M. Genes involved in organ separation in Arabidopsis: An analysis of the cup-shaped cotyledon mutant. Plant Cell 9, 841–857. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.9.6.841 (1997).

Puranik, S., Sahu, P. P., Srivastava, P. S. & Prasad, M. NAC proteins: Regulation and role in stress tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 17(6), 369–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2012.02.004 (2012).

Kim, T. et al. Evolution of NAC transcription factors from early land plants to domesticated crops. Plant Cell Physiol. 66(4), 566–580. https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pcae133 (2025).

Sun, Q. W. et al. A cotton NAC domain transcription factor, GhFSN5, negatively regulates secondary cell wall biosynthesis and anther development in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 146, 303–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2019.11.030 (2020).

Vroemen, C. W., Mordhorst, A. P., Albrecht, C., Kwaaitaal, M. A. & de Vries, S. C. The CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON3 gene is required for boundary and shoot meristem formation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 15, 1563–1577. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.012203 (2003).

Zimmermann, R. & Werr, W. Pattern formation in the monocot embryo as revealed by NAM and CUC3 orthologues from Zea mays. Plant Mol. Biol. 58, 669–685. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11103-005-7702-x (2005).

Guo, Y. & Gan, S. AtNAP, a NAC family transcription factor, has an important role in leaf senescence. Plant J. 46, 601–612. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02723.x (2006).

Duval, M., Hsieh, T. F., Kim, S. Y. & Thomas, T. L. Molecular characterization of AtNAM: A member of the Arabidopsis NAC domain superfamily. Plant Mol. Biol. 50, 237–248. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016028530943 (2002).

Kim, Y. S. et al. A membrane-bound NAC transcription factor regulates cell division in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18, 3132–3144. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.106.043018 (2006).

Willemsen, V. et al. The NAC domain transcription factors FEZ and SOMBRERO control the orientation of cell division plane in Arabidopsis root stem cells. Dev. Cell 15, 913–922. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2008.09.019 (2008).

Ooka, H. et al. Comprehensive analysis of NAC family genes in Oryza sativa and Arabidopsis thaliana. DNA Res. 10, 239–247. https://doi.org/10.1093/dnares/10.6.239 (2003).

Pinheiro, G. L. et al. Complete inventory of soybean NAC transcription factors: sequence conservation and expression analysis uncover their distinct roles in stress response. Gene 444, 10–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2009.05.012 (2009).

Bai, S. et al. Genome-wide identification of the NAC transcription factors in Gossypium hirsutum and analysis of their responses to Verticillium wilt. Plants 11, 2661. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11192661 (2022).

Tak, H., Negi, S. & Ganapathi, T. R. Banana NAC transcription factor MusaNAC042 is positively associated with drought and salinity tolerance. Protoplasma 254, 803–816. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00709-016-0991-x (2016).

Song, H. et al. Genome-wide characterization and comprehensive analysis of NAC transcription factor family in Nelumbo nucifera. Front. Genet. 13, 901838. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2022.901838 (2022).

Li, C. et al. Genome-wide identification and analysis of the NAC transcription factor gene family in garden asparagus (Asparagus officinalis). Genes (Basel) 13, 976. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes13060976 (2022).

Zhang, H. et al. Genome-wide identification and expression profile analysis of the NAC transcription factor family during abiotic and biotic stress in woodland strawberry. PLoS ONE 13, e0197892. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0197892 (2018).

Shen, Q. et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the NAC transcription factor family in Saccharum spontaneum under different stresses. Plant Signal Behav. 17, 2088665. https://doi.org/10.1080/15592324.2022.2088665 (2022).

Lightfoot, D. J. et al. Single-molecule sequencing and Hi-C-based proximity-guided assembly of amaranth (Amaranthus hypochondriacus) chromosomes provide insights into genome evolution. BMC Biol. 15(1), 74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-017-0412-4 (2017).

Weiping, D. et al. Genome-wide analyses of the NAC transcription factor gene family in pepper (Capsicum annuum): Chromosome location, phylogeny, structure, expression patterns, cis-elements in the promoter, and interaction network. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 1028. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19041028 (2018).

Ma, Q. et al. Comparative genomics of NAC TFs in Solanum lycopersicum and their evolutionary divergence. Life Sci. 33, 405–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2023.130045 (2023).

Moyang, L. et al. Genome-wide analysis of the NAC transcription factor family in tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum). BMC Genomics 20, 113. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-019-5500-0 (2019).

Le, D. T. et al. Genome-wide survey and expression analysis of the plant-specific NAC transcription factor family in soybean during development and dehydration stress. DNA Res. 18, 263–276. https://doi.org/10.1093/dnares/dsr015 (2011).

Wei, W. et al. Genome-wide analysis of Beta vulgaris NAC genes. BMC Genomics 21, 122. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-020-6515-3 (2020).

Liu, M. et al. Genome-wide identification, characterization, and expression analysis of the NAC transcription factor in Chenopodium quinoa. Genes (Basel) 10, 500. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes10070500 (2019).

Dwayne, H. et al. Molecular characterization of Brassica napus NAC domain transcriptional activators induced in response to biotic and abiotic stress. Plant Mol. Biol. 53, 383–397. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:PLAN.0000006944.61384.11 (2003).

Liu, C. et al. Genome-wide analysis of NAC transcription factors in wheat. G3 (Bethesda) 10, 1327–1339. https://doi.org/10.1534/g3.120.401014 (2020).

Wang, H. et al. Characterization of NAC gene family in Zea mays and their expression in response to stress. Front. Genet. 11, 567890. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2020.567890 (2020).

Dorjee, T. et al. Characterization of NAC Gene Family in Ammopiptanthus mongolicus and Functional Analysis of AmNAC24, an Osmotic and Cold-Stress-Induced NAC Gene. Biomolecules 14(2), 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom14020182 (2024).

Liu, X. et al. Overexpression of Arachis hypogaea NAC3 in tobacco enhances dehydration and drought tolerance by increasing superoxide scavenging. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 70, 354–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.05.018 (2013).

Li, P. et al. Genome-wide identification of NAC transcription factors and their functional prediction of abiotic stress response in peanut. Front Genet. 9(12), 630292. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2021.630292 (2021).

Goodstein, D. M. et al. Phytozome: A comparative platform for green plant genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D1178–D1186. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkr944 (2012).

Wang, J. et al. The conserved domain database in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D354–D360. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac1096 (2022).

Jones, P. et al. InterProScan 5: Genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 30, 1236–1240. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu031 (2014).

Finn, R. D. et al. Pfam: The protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D222–D230. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkt1223 (2014).

Tamura, K. et al. MEGA11: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 3022–3027. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msab120 (2021).

Letunic, I. & Bork, P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v5: An online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, W293–W296. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab301 (2021).

Chen, C. et al. TBtools: An integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 13, 1194–1202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009 (2020).

Sganzerla Martinez, G., Dutt, M., Kumar, A. & Kelvin, D. J. Multiple protein profiler 1.0 (MPP): A webserver for predicting and visualizing physiochemical properties of proteins at the proteome level. Protein J. 43(4), 711–717. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10930-024-10214-z (2024).

Savojardo, C. et al. BUSCA: An integrative web server to predict subcellular localization of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W459–W466. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky320 (2018).

Krogh, A., Larsson, B., von Heijne, G. & Sonnhammer, E. L. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: Application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 305, 567–580. https://doi.org/10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315 (2001).

Lescot, M. et al. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 325–327. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/30.1.325 (2002).

Dai, X. & Zhao, P. X. psRNATarget: A plant small RNA target analysis server. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, W155–W159. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkr319 (2011).

Martínez Núñez, M. et al. Identification of genuine and novel miRNAs in Amaranthus hypochondriacus from high-throughput sequencing data. Genomics 113(1 Pt 1), 88–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygeno.2020.11.027 (2021).

Imakumbili, M. et al. Managing cassava growth on nutrient poor soils under different water stress conditions. Heliyon 7(6), e07331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07331 (2021).

Untergasser, A. et al. Primer3–new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 40(15), e115. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks596 (2012).

Schmittgen, T. D. et al. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat. Protoc. 3(6), 1101–1108. https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2008.73 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Director of BRIC-Centre for DNA Fingerprinting and Diagnostics (BRIC-CDFD), Hyderabad, and the Director of the ICAR-National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources (ICAR-NBPGR), New Delhi, for providing the necessary facilities and support to carry out this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K.M. conceptualized the study and designed the methodology. E.R. performed all data analysis and curation. A.S. and A.M. conducted the qRT-PCR experiments. E.R. and A.K.M. prepared the initial draft of the manuscript. N.K.S. and R.S. contributed to manuscript review and editing. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Eerapagula, R., Singh, A., Maurya, A. et al. Genome-wide analysis of NAC transcription factors in grain amaranth reveals structural diversity and regulatory features. Sci Rep 15, 39968 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23630-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23630-7