Abstract

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases (ASCVD) are a group of diseases that can lead to serious lethal and disabling consequences, in which inflammation plays a key role. Although the role of eosinophils as innate immune cells in cardiovascular disease has been extensively studied, their specific impact is unclear and conflicting findings exist. The aim of this research was to assess the potential association between eosinophil count and ASCVD in US adults and to identify specific populations more strongly associated with ASCVD through subgroup analyses. This study conducted a cross-sectional analysis based on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) between 2011 and 2018. Eosinophil counts data were derived from laboratory test results, while the diagnosis of ASCVD was derived from a questionnaire completed by the participants, defined as the respondent having been told that they had at least one of congestive heart failure, coronary heart disease, angina pectoris, heart attack, or stroke. A multivariate logistic regression model was used in the study to explore the potential association between eosinophil count and ASCVD. A total of 20,363 participants were enrolled in this study, including 2,256 patients with ASCVD. After multivariate logistic regression analyses and adjustment for relevant covariates, a significant positive association was found between eosinophil count and ASCVD. In addition, the subgroup analysis revealed an interesting finding: the association between eosinophil counts and ASCVD was more pronounced among older persons, smokers, and males. A positive correlation between eosinophil counts and ASCVD has been shown in the American adult population. In addition, in certain subpopulations—such as older persons, smokers, and males—the association between eosinophil counts and the occurrence of ASCVD appeared to be stronger.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) is an inclusive term for a group of cardiac and systemic vascular diseases caused by atherosclerosis, which encompasses serious diseases such as coronary heart disease and stroke, and is one of the leading causes of death and disability worldwide1,2. Traditional risk factors for ASCVD include hyperlipidemia, hypertension and diabetes mellitus, which have been widely confirmed in previous studies3,4,5,6. As chronic inflammation plays an important role in ASCVD, the study of innate immunity in ASCVD has received a lot of attention7,8,9. Eosinophils, as an important component of innate immune cells, are closely related to the inflammatory response of the body10. Historically, the main focus has been on its role in allergic reactions, but recent studies have found a significant link between eosinophils and atherosclerosis11,12. In a retrospective study of 430 patients with acute ischaemic stroke, they defined complex aortic arch plaques (CAP) as plaques ≥ 4 mm in thickness with an ulcerated or mobile component. The results of the study showed that patients with complex aortic arch atherosclerotic plaques had higher blood eosinophil counts than patients with aortic arch plaques without complex features13. In the other study, eosinophils were found to correlate with the degree of atherosclerotic lesions in asthmatics, and asthmatics with eosinophil counts greater than 300 n/ul had more severe atherosclerotic lesions14. Moreover, the study by Meng et al. further revealed that eosinophil knockdown attenuates vascular calcification as well as the progression of arteriosclerosis in mice15. Eosinophils play a complex and critical role in cardiovascular disease caused by atherosclerosis. A Meta-analysis reveals an association between high eosinophil counts and acute coronary thrombotic events, short-term cerebral infarction, and mortality16. However, it has also been found that low eosinophil counts are associated with increased severity of coronary artery disease (CAD) and increased risk of acute coronary thrombotic events17. These conflicting findings prompted a review article to delve into the role of eosinophils in different cardiovascular diseases, noting that the relationship between eosinophils and cardiovascular disease is unclear and may be related to the timing of the cardiovascular event as well as the point in time at which the eosinophil data were collected11. Therefore, by analysing data from a large sample of adults from a nationally representative community in the NHANES, we aimed to assess the relationship between eosinophil counts and ASCVD.

Methods

Participants

Data for this study were obtained from NHANES, an ongoing cross-sectional, multistage, stratified survey designed to assess the nutritional and health status of a nationally representative sample of United States civilians. All participants in the NHANES study gave their informed consent prior to their involvement. This study followed the Declaration of Helsinki, received ethical approval from the Ethical Review Committee of the National Centre for Health Statistics. To assess the relationship between eosinophil counts and ASCVD, our study utilized data from four NHANES cycles: 2011–2012, 2013–2014, 2015–2016, and 2017–2018, which included a total of 23,063 participants.

Definition of ASCVD

ASCVD was defined as the presence of at least one of these factors: congestive heart failure, coronary heart disease, angina, heart attack and stroke. The source of all these data is the questionnaire on the CDC-NCHS website. Heart failure, coronary heart disease, angina, heart attack (myocardial infarction), and stroke were defined based on self-reported responses to the NHANES questionnaire, in which participants were asked whether they had ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that they had the condition.

Covariates

In this study, we included a range of personal data as covariates, including gender, age, race, body mass index (BMI), smoking history, blood pressure, glycated haemoglobin, lipid levels, asthma history, emphysema, and chronic bronchitis. Specifically, hypertension was defined as an average of three measurements of blood pressure exceeding 140/90 mmHg; The diagnostic criterion for diabetes mellitus is a glycosylated haemoglobin level greater than 7.0%; Smoking history was then defined as smoking more than 100 cigarettes in a lifetime. According to the age classification of the World Health Organization (WHO), the older persons are defined as people aged ≥ 60. These covariates were fully considered in the statistical analyses to control for their possible potential impact on the association between eosinophil counts and ASCVD, thus ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the study results. All detailed measurement procedures are available at www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/publicly.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses in this study were performed using R software (version 4.4.1). To assess the baseline characteristics of the participants based on their history of ASCVD, we used chi-square tests and t-tests. Based on the median eosinophil counts, we categorised the participants into a low eosinophil group (Low group < 0.2 (1000n/ul)) and a high eosinophil group (High group ≥ 0.2 (1000n/ul)). To assess the relationship between eosinophil counts and ASCVD, we used multivariate logistic regression analysis and constructed models with three different levels of adjustment: Model 1 did not adjust for any covariates; Model 2 adjusted for gender, age, and race; and Model 3 adjusted for all relevant covariates. In addition, we used the restricted cubic spline method to assess the nonlinear correlation between eosinophil counts and ASCVD. In applying cubic spline, we set up four nodes. In this study, p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

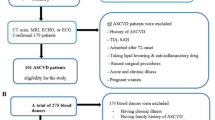

Figure 1 illustrates the sampling process flowchart for the NHANES study from 2011 to 2018. Table 1 demonstrates the baseline characteristics of 20,363 participants during NHANES 2011–2018, including 2,256 patients with ASCVD. Among ASCVD participants, the proportion of males was higher, about 55.67%, and the mean age of participants was significantly higher than that of non-ASCVD participants. Racial distribution also showed differences, with non-Hispanic whites having higher rates of ASCVD. Patients with ASCVD have higher levels of BMI, suggesting that obesity is a contributing factor to ASCVD. In addition, ASCVD has higher rates of hypertension, diabetes, smoking, asthma, emphysema and chronic bronchitis. In terms of continuous variables, patients with ASCVD had higher levels of triglycerides, fasting glucose, blood pressure (both systolic and diastolic), and lower levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) compared with individuals without ASCVD. Surprisingly, patients with ASCVD had lower low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL) levels than those without ASCVD, which may be explained by intensive lipid-lowering therapy and survivor bias. Notably, eosinophil counts were significantly higher in participants with ASCVD than in those without ASCVD (0.23 vs. 0.20 1000n/ul, p < 0.0001).

Relationship between eosinophil counts and ASCVD

To delve deeper into the relationship between eosinophil counts and ASCVD as well as its risk factors, we divided participants into two groups based on median eosinophil counts and analysed their distribution among ASCVD and non-ASCVD participants (Table 2). Participants with eosinophil counts < 0.2 (1000n/ul) were classified as the Low group, and those with eosinophil counts ≥ 0.2 (1000n/ul) were classified as the High group. Populations with higher eosinophil counts had larger proportions of males, older people, members of particular ethnic groups, and smokers. It is worth noting that their incidence of lung diseases is also high, such as asthma, emphysema, and chronic bronchitis. These could all be potential confounding factors. In addition, their systolic blood pressure, glycated haemoglobin, and triglyceride levels were significantly higher than those in the group with lower eosinophil counts (p < 0.001), while HDL levels were significantly lower than those in the group with lower eosinophil counts (p < 0.001). In terms of the prevalence of ASCVD sub-outcomes, the group with higher eosinophil counts had higher proportions of congestive heart failure, coronary atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, angina pectoris, heart attack, and stroke (p < 0.001). When eosinophil count was analyzed as a continuous variable, we discovered that it was significantly associated with an increased risk of ASCVD using multivariate logistic regression analysis. This association showed statistical significance in three different models(Table 3). All five sub-outcomes showed a correlation with the eosinophil count in both models 1 and 2. However, in Model 3, eosinophil counts remained significantly associated only with heart attack(P < 0.001). This suggests that after accounting for other potential confounders, the association between eosinophil counts and other sub-outcomes may be less important than initially observed. When eosinophil count was analysed as a categorical variable, with lower eosinophil counts as the reference group, we found a significant correlation between higher eosinophil counts and ASCVD in both models 1 and 2. After adjusting for all potential confounders, Model 3 did not reveal any significant associations, which may be attributable to the loss of group differences when analyzed as categorical variables. In model 2, although the correlation between eosinophil count and CHD approached the level of significance (p = 0.055), it did not reach statistical significance. However, eosinophil counts still showed significant correlations in other ASCVD sub-outcomes. Further, in model 3, significant correlations between eosinophil count and heart attack (P = 0.039), stroke (P = 0.049)were confirmed after adjustment for all relevant covariates. These findings highlight the potential importance of eosinophil count in ASCVD risk assessment. Using restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis, we explored the correlation between eosinophil count and ASCVD, as well as two sub-outcomes, heart attack and stroke. In univariate regression analyses, eosinophil count showed a non-linear relationship with all three outcomes(Fig. 2A-C). However, after adjusting for covariates, no evidence of a non-linear relationship was observed between eosinophil counts and the primary outcome (ASCVD) or the secondary outcomes (heart attack and stroke). (Fig. 3A-C). This suggests that the nonlinear associations observed in the univariate analysis were largely driven by confounding variables such as age, smoking status, pulmonary disease, and other cardiovascular risk factors. Once these factors were adjusted for, the relationships became more stable and tended to approximate linearity. These findings indicate that eosinophil counts may have a linear association with ASCVD. In addition, among the sub-outcomes, eosinophil counts may exhibit a linear association with heart attack. For the stroke(P_overall = 0.054), indicating a trend toward association but without statistical significance. These differences may require confirmation through studies with larger sample sizes or further clinical investigations.

Restricted cubic spline analysis of eosinophil count and ASCVD. (A) ASCVD for all participants; (B) Heart attack for all participants; (C) Stroke for all participants. Age, gender, race, BMI, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, HDL, TG, LDL, TC, Asthma, Emphysema, Chronic bronchitis were adjusted. ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; BMI, body mass index; HDL, High density lipoprotein; TG, Triglycerides; TC, Total Cholesterol; LDL, Low density lipoprotein.

Subgroup analysis

Figure4 displays the findings of the subgroup analyses and interactions as a forest plot. After subgrouping by gender, age, race, BMI, hypertension, diabetes, and smoking history, we found that the correlation between eosinophil counts and ASCVD was more pronounced in the following subgroups: males (p = 0.005), those older than 60 years (p = 0.008), and smokers (p = 0.026). These results suggest that the impact of eosinophil counts on ASCVD may be more important in these specific high-risk populations. It is noteworthy that this was an exploratory analysis, while the findings provide some insights, they still require confirmation in studies with larger sample sizes and further clinical investigations.

Discussion

Eosinophils typically comprise 1–5% of all peripheral blood leukocytes and are a crucial granulocyte type in the innate immune system10,18. They play a key role in ASCVD19. Several clinical studies have found that elevated eosinophil counts are associated with an increased risk of ASCVD20,21,22. A single-centre cohort study examining the relationship between eosinophil count and coronary artery disease (CAD) found that a high eosinophil count was associated with CAD risk factors such as gender and history of previous coronary artery reconstruction, but in multivariate analysis, eosinophil counts did not show independent associations with the prevalence and severity of CAD22. Another study involving 478,259 participants in the UK, with 1,377 deaths from cardiovascular disease during a seven-year follow-up period, showed that patients who died from cardiovascular disease had higher blood eosinophil counts than those who were still alive at the end of the follow-up. This suggests that eosinophil counts may be associated with the risk of death from cardiovascular disease21. There was also a study of 333,218 participants followed for 6 years, during which time 8,164 developed CVD, which showed that patients who developed CVD had higher baseline blood eosinophil counts than controls. This further supports the association between eosinophil counts and the development of CVD20. Contrary to previous findings, several studies have proposed the hypothesis that low eosinophil counts are associated with a high risk of ASCVD17,23. A study by Gao et al. in 5,287 patients undergoing coronary angiography showed that low eosinophil counts correlated with the severity of coronary artery disease and the incidence of acute myocardial infarction (AMI). In addition, they found that combining the percentage of eosinophils with traditional risk factor models improved the ability of the models to predict the severity of coronary heart disease and acute coronary thrombotic events17. These findings emphasise the complex role of eosinophil counts in assessing cardiovascular disease risk, which may play different roles in different clinical contexts.

The current study offers intricate and multidimensional findings in its investigation of the function of eosinophils in the pathogenic mechanisms of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. In atherosclerosis, experimental studies by Meng et al. have shown that eosinophil cationic protein (ECP) plays a facilitator role in the development of atherosclerosis15. In heart transplant patients, a correlation was observed between the degree of graft atherosclerosis and eosinophil infiltration24. Through their interactions with platelets, these eosinophils not only increase thrombosis and inflammatory reactions25,26, but their cationic proteins also worsen vascular calcification mediated by vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), which furthers the development of atherosclerosis. However, in the pathology of myocardial infarction, the study by Liu et al. demonstrated an increase in eosinophils in peripheral blood and infarcted tissue after myocardial infarction in both clinical and animal models. Notably, in a mouse model of myocardial infarction in which eosinophils were knocked out, the severity of myocardial infarction was instead exacerbated, suggesting that eosinophils accumulated in the myocardial tissue actually play a protective role. Further studies found that eosinophils inhibit ventricular remodelling by reducing cardiomyocyte death and inhibiting fibroblast activation27. Another clinical trial also revealed similar results, however it found that after myocardial infarction, there were less eosinophils in the peripheral blood, which could be because eosinophils had been taken into the infarcted tissue28. Together, these findings reveal an important role for eosinophils in protecting the heart from myocardial infarction injury. In addition, in heart failure, IL-4 and the cationic protein EAR1 released by eosinophils have been shown to be cardioprotective, and they act by attenuating apoptosis in cardiomyocytes29. According to the previous research, eosinophils have a dual function in ASCVD. It can both protect the heart by preventing ventricular remodeling and cardiomyocyte death, and it may aggravate the development of atherosclerosis by increasing vascular calcification and inflammatory reactions.

Based on these conflicting results, we assessed the correlation between eosinophil counts and ASCVD by analysing nationally representative data from a large sample in the Nhanes database. In this cross-sectional study, we investigated the relationship between is eosinophil counts and ASCVD in NHANES 2011–2018. After adjusting for multiple covariates, we observed that higher eosinophil counts may be associated with ASCVD occurrence. In the sub-outcome analysis of Model 3, after adjusting for covariates, eosinophil counts were associated with heart attack and stroke, but not with HF, CHD, or angina pectoris. This discrepancy may be related to limitations of the NHANES database, as patients with HF, CHD, and angina pectoris often present with atypical symptoms, leading to underreporting. In contrast, heart attack and stroke usually have an abrupt onset with striking manifestations, making them more likely to be accurately recalled and documented. In addition, eosinophils may play a more important role in plaque instability and thrombosis, which are central to acute events such as myocardial infarction and stroke. This could biologically explain the stronger association with acute cardiovascular events compared to stable manifestations of coronary heart disease. In addition, the relatively small sample size may also be one of the reasons for the observed differences. RCS analysis demonstrated that, after adjusting for covariates, eosinophil counts may have a linear relationship with ASCVD and heart attack. Our analysis indicated a positive association between eosinophil counts and heart attack. However, given that NHANES is a cross-sectional study, causal inference cannot be established. Whether the increase in eosinophils is a consequence of the acute event, plays a protective role, or contributes to disease progression remains unclear and warrants further experimental investigation. Furthermore, subgroup analyses also revealed that the correlation between eosinophil counts and ASCVD was more significant in the older persons, smokers and males, suggesting that greater attention should be given to cardiovascular health in older persons, smokers, and males with elevated eosinophil counts. A clinical study involving 104 male smokers and 94 male non-smokers demonstrated that smokers exhibited elevated peripheral blood eosinophil and neutrophil counts, leading to the activation of systemic inflammatory responses30, which may accelerate the progression of cardiovascular disease.

Limitations

This study does have some inherent limitations. First, because of the cross-sectional design of this study, we could only observe a positive association between eosinophil count and the development of ASCVD. We could not determine the causality of the association, that is, whether the elevation of eosinophils is a cause or effect of the development of ASCVD or whether there are other unobserved confounding factors between the two. Second, the study sample was limited to U.S. adults, which may limit the generalisability of the findings to other regions or different populations. Therefore, care needs to be taken when applying these findings to other regions, taking into account how the genetic backgrounds, lifestyles and environmental factors of populations in different regions may affect the results. Third, this study was based on the NHANES database, where all diagnoses relied on participants’ self-reported questionnaires, which may introduce diagnostic inaccuracies. Fourth, due to the inherent limitations of the NHANES database, we were unable to obtain data on certain potential confounders, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and medication use, which may have influenced the results.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study established an association between eosinophil counts and the occurrence of ASCVD by multivariate logistic regression analysis using nationally representative population samples from four cycles of the NHANES database between 2011 and 2018. In the sub-outcome analysis, eosinophil counts appeared to exhibit a linear association only with heart attack. Further subgroup analyses showed that the association between eosinophil counts and ASCVD was particularly significant in the group of older persons, smokers, males, providing valuable reference information for US efforts in clinical screening and prevention of ASCVD.

Data availability

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: direct link to the data: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.

References

Zheng, W. C., Chan, W., Dart, A. & Shaw, J. A. Novel therapeutic targets and emerging treatments for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 10 (1), 53–67 (2024).

Tsao, C. W. et al. Heart disease and stroke Statistics-2022 update: A report from the American heart association. Circulation 145 (8), e153–e639 (2022).

Mach, F. et al. 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur. Heart J. 41 (1), 111–188 (2020).

Coca, A. et al. Estimated impact of guidelines-based initiation of dual antihypertensive therapy on long-term cardiovascular outcomes in 1.1 million individuals. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 10 (8), 697–707 (2025).

Xiao, Y. et al. Chinese expert consensus on blood lipid management in patients with diabetes (2024 edition). J. Transl Int. Med. 12 (4), 325–343 (2024).

Yi, J., Qu, C., Li, X. & Gao, H. Insulin resistance assessed by estimated glucose disposal rate and risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases incidence: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 23 (1), 349 (2024).

Wadström, B. N., Pedersen, K. M., Wulff, A. B. & Nordestgaard, B. G. Inflammation compared to low-density lipoprotein cholesterol: two different causes of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 34 (3), 96–104 (2023).

Mazhar, F. et al. Systemic inflammation and health outcomes in patients receiving treatment for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Eur. Heart J. 45 (44), 4719–4730 (2024).

Rossello, X. Lifetime risk Estimation in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: where inflammation Meets Lipoprotein(a). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 78 (11), 1095–1096 (2021).

Kim, H. J. & Jung, Y. The emerging role of eosinophils as multifunctional leukocytes in health and disease. Immune Netw. 20 (3), e24 (2020).

Xu, J. et al. Differential roles of eosinophils in cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 22 (3), 165–182 (2025).

Gerdes, N. Eosinophils promote vascular calcification and atherosclerosis: adding another layer of complexity on the path to clarity? Eur. Heart J. 44 (29), 2784–2786 (2023).

Kitano, T. et al. Association between absolute eosinophil count and complex aortic arch plaque in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 48 (4), 1074–1076 (2017).

Biener, L. et al. Blood eosinophil count is associated with early atherosclerotic artery changes in asthma. BMC Pulm Med. 24 (1), 509 (2024).

Meng, Z. et al. Cationic proteins from eosinophils bind bone morphogenetic protein receptors promoting vascular calcification and atherogenesis. Eur. Heart J. 44 (29), 2763–2783 (2023).

Xu, W. J. et al. Arterial and venous thromboembolism risk associated with blood eosinophils: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Anim. Model. Exp. Med. 5 (5), 470–481 (2022).

Gao, S. et al. Eosinophils count in peripheral circulation is associated with coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis 286, 128–134 (2019).

Jung, Y. & Rothenberg, M. E. Roles and regulation of Gastrointestinal eosinophils in immunity and disease. J. Immunol. 193 (3), 999–1005 (2014).

Pongdee, T. et al. Rethinking blood eosinophil counts: Epidemiology, associated chronic diseases, and increased risks of cardiovascular disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Glob. 1 (4), 233–240 (2022).

Groot, H. E., van Blokland, I. V., Lipsic, E., Karper, J. C. & van der Harst, P. Leukocyte profiles across the cardiovascular disease continuum: A population-based cohort study. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 138, 158–164 (2020).

Welsh, C. et al. Association of total and differential leukocyte counts with cardiovascular disease and mortality in the UK biobank. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc Biol. 38 (6), 1415–1423 (2018).

Verdoia, M. et al. Absolute eosinophils count and the extent of coronary artery disease: a single centre cohort study. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis. 39 (4), 459–466 (2015).

Shah, A. D., Denaxas, S., Nicholas, O., Hingorani, A. D. & Hemingway, H. Low eosinophil and low lymphocyte counts and the incidence of 12 cardiovascular diseases: a CALIBER cohort study. Open. Heart. 3 (2), e000477 (2016).

Spriewald, B. M., Ensminger, S. M., Billing, J. S., Morris, P. J. & Wood, K. J. Increased expression of transforming growth factor-beta and eosinophil infiltration is associated with the development of transplant arteriosclerosis in long-term surviving cardiac allografts. Transplantation 76 (7), 1105–1111 (2003).

Dou, H. et al. Hematopoietic and eosinophil-specific LNK(SH2B3) deficiency promotes eosinophilia and arterial thrombosis. Blood 143 (17), 1758–1772 (2024).

Marx, C. et al. Eosinophil-platelet interactions promote atherosclerosis and stabilize thrombosis with eosinophil extracellular traps. Blood 134 (21), 1859–1872 (2019).

Liu, J. et al. Eosinophils improve cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Nat. Commun. 11 (1), 6396 (2020).

Toor, I. S. et al. Eosinophil deficiency promotes aberrant repair and adverse remodeling following acute myocardial infarction. JACC Basic. Transl Sci. 5 (7), 665–681 (2020).

Yang, C. et al. Eosinophils protect pressure overload- and β-adrenoreceptor agonist-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Cardiovasc. Res. 119 (1), 195–212 (2023).

Khudhur, Z. O. et al. The effects of heavy smoking on oxidative stress, inflammatory biomarkers, vascular dysfunction, and hematological indices. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 18251 (2025).

Funding

The Shanxi Provincial Government’s Regional Cooperation Program (Grant No. 202204041101038), the Leading Talent Team Building Program (Grant No. 202204051002010), the Translational Medicine Engineering Research Center for Vascular Diseases of Shanxi Province, China (Grant No. 2022017), the Construction and Demonstration of Molecular Diagnosis and Treatment Platform for Vascular Diseases in Shanxi Province, China (Grant No. SCP-2023-17), and the Central Government Guidance Fund for Local Projects, China (YDZJSX2021C026) all provided funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Runze Chang: Writing – original draft, Data curation. Chuanglong Lu: Data curation, Formal analysis. Ruijing Zhang: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Honglin Dong: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, R., Lu, C., Zhang, R. et al. Correlation of peripheral blood eosinophil counts with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 15, 39924 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23658-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23658-9