Abstract

Heterosis has been widely used to increase crop yield. Four genetic heterosis models have been proposed previously: dominance, overdominance, epistasis, and pseudo-overdominance models. In a previous study, the remarkable heterosis for culm length (CL) of the F1 variety ‘Tentaka’ (MS79 × 74LH3213) of high biomass sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench) can be explained based on the dominance model involving five genes. However, whether other genes or epistatic interactions contribute to the heterosis remains unclear. Here, we clarified the two points and propose an updated model of the heterosis. We conducted quantitative trait locus (QTL) and epistasis analyses for CL and flowering date by employing a joint F2 population, consisting of each F2 population of the progeny of MS79 × 74LH3213 cultivated for over 4 years. In addition to the five known genes, a sixth QTL was indicated on chromosome 6. The corresponding candidate gene was Ma1/SbPRR37, which was linked with Ma6/SbGhd7, one of the five genes. The genes showed a repulsive phase in the pericentromeric region, and pseudo-overdominance was observed. Although five QTL epistatic interactions were detected, their genetic effects were weaker than those of most single QTLs. In conclusion, as all the dominant alleles of the six loci were major elements for the heterosis, it can be explained mainly based on the dominance model and partially by the epistasis model. The present study provides new insights into the genetic basis of the heterosis and could serve as a model for understanding heterosis in other crops.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heterosis is a phenomenon in which a hybrid is superior to its parental lines. It has been used to increase the grain and biomass yields, quality, and biotic and abiotic stress tolerance of crops1. For example, hybrid corn became a main crop in the United States in the 1950 s, with yields increasing approximately fourfold from the 1930 s to the 1960s2. The development of commercial hybrid rice in China began in the 1970 s to increase yield3. Thus, hybrid breeding is a crucial approach for supporting the global food demand with an increasing population.

Four representative genetic models of heterosis have been proposed: dominance, overdominance, epistasis, and pseudo-overdominance models4. The dominance model attributes heterosis to the complementation of deleterious recessive alleles and accumulation of dominant alleles in F1 hybrids5. The overdominance model proposes that heterozygous genotypes at specific loci outperform homozygous genotypes6. The epistasis model explains heterosis through interactions between loci7. In addition, multiple genes in the repulsion linkage in two parental inbred lines can be detected as mimicking an overdominance locus, called pseudo-overdominance. Because the strength of the linkage between multiple genes affects whether they are detected as an overdominant locus8, pseudo-overdominance is often detected in pericentromeric regions in maize9,10. Epigenetic mechanisms, such as DNA methylation, histone acetylation, and chromatin modification, also play a role in heterosis11. All of these models have contributed to hybrid vigor in multiple crops, and combined models have been fitted in some cases9,12,13,14,15,16. Therefore, multiple models must be tested to elucidate the genetic mechanisms underlying heterosis.

Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench) is a versatile crop used as food, forage, and bioenergy17. Grain sorghum breeding programs have focused on achieving semi-dwarf stature and early flowering, and four dwarf loci (Dw1–Dw4) and six maturity loci (Ma1–Ma6) have been utilized in breeding17,18. By contrast, feed and bioenergy sorghum breeding emphasizes high biomass for structural and nonstructural carbohydrate yields. Hybrid vigor has been exploited for breeding high-biomass sorghum. For example, the plant height of the Japanese hybrid variety (MS79 × 74LH3213) ‘Tentaka’ reaches ~ 4 m, despite its parents having a height of ~ 1.2 m19. The mid-parent heterosis for culm length (CL) of the F1 variety exceeded 193%19, and the heterosis was more pronounced in sorghum than in rice and maize15,16. In our previous study, we estimated that the heterosis is caused by five genes19 associated with internode elongation (Dw1, Dw3, and Dw7a) and flowering date (FD; Ma3 and Ma6). Dw1 is a positive regulator of brassinosteroid (BR) signaling20,21,22. Dw3 encodes an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter, which is an ortholog of Arabidopsis ABCB1 and ABCB1923,24. Dw3 functions as an auxin transport facilitator23; however, ABCB19 functions as a BR exporter and, together with ABCB1, positively regulates BR signaling25,26. Dw7a, which has been cloned recently, is a new dwarfing gene that encodes a MYB transcription factor and is orthologous to maize brachytic 119,27,28. Ma3 and Ma6 are maturity genes; the former encodes phytochrome B (PhyB), which functions as a photoreceptor, whereas the latter is an ortholog of rice Ghd7 (Grain Number, Plant Height, and Heading Date 7), which represses flowering in long days (LD)29,30. Other maturity and dwarfing genes include Ma1, Ma2, and Dw2. Ma1 encodes pseudo-response regulator protein 37 (PRR37) and functions in the biological circadian clock31. Ma2 enhances Ma1 and SbCO expression and delays flowering in LD32. Dw2 encodes the AGCVIII protein kinase KIPK and modulates endomembrane and cell division33,34.

The parents (MS79 and 74LH3213) are homozygous for the recessive alleles of each of the five genes (dw7a and ma6/sbghd7 for MS79, and dw1, dw3, and ma3/sbphyB for 74LH3213), and the deleterious recessive alleles of these genes have been complemented by the dominant alleles in the hybrid19. In addition, an integrated line with five homozygous dominant alleles (i5), which pyramided the dominant alleles of the five genes into the genetic background of the male parent, exhibited approximately 85% of CL against that of F1 hybrid. These findings suggest that heterosis can be explained by the dominance model19. Although these results indicate that the overdominance effect does not play a major role, whether epistatic effects contribute to the heterosis remains unclear. Moreover, no study has verified the extent to which the epistasis model is involved in heterosis in sorghum at the genetic locus level. Furthermore, the CL of i5 did not completely correspond to that of the F1 hybrid. Although i5 carried homozygous dominant alleles of the five genes, the variances in CL and FD were higher than those in the F1 hybrid19. Thus, other genes may contribute to the heterosis.

In this study, we aimed to (1) detect loci associated with the heterosis of CL beyond the five known genes and (2) reveal the contribution of epistatic effects to the heterosis. A quantitative trait locus (QTL) analysis was performed using a joint F2 population derived from MS79 × 74LH3213 grown over 4 years. Ma1/SbPRR37, which controls flowering time in sorghum, was newly identified as the corresponding gene for the heterosis. In conclusion, the heterosis can be explained mainly by the six-gene dominance model and partially by the epistasis model. Notably, Ma1/SbPRR37 and Ma6/SbGhd7 were linked to repulsion, resulting in pseudo-overdominance in this analysis. These findings enhance our understanding of heterosis in sorghum and offer valuable insights for sorghum and other crop breeding programs.

Materials and methods

Single-QTL analysis using joint F2 population

In our previous study19, a QTL analysis for CL and FD was conducted using F2 populations derived from MS79 × 74LH3213 over 4 years (2013, 2014, 2015, and 2018). A total of 653 plants with either CL or FD in the previous data were selected for the present study. To account for environmental effects, we combined the F2 populations using the following formula:

where µ is the overall mean in the population, E is the environmental effect for each year, and e is the residual value. The regression analysis was performed with environmental effects as fixed effects. Specifically, the years were treated as a dummy variable. The e values of CL and FD, which included genetic effects and genotype-by-environment interactions, were used as phenotypic values and referred to as joint data (Supplementary Fig. S1).

DNA markers reported by Hashimoto et al. (2021) were used, and those with 50% missing genotypes were excluded. A linkage map with 145 DNA markers was constructed using R/qtl35 (Supplementary Table S1). Map distances were calculated using Kosambi’s method36 (Supplementary Table S2). A single-QTL analysis of the joint data was performed using composite interval mapping (CIM) in R/qtl37, with conditions set to a 10 cM window size and 1 cM walk speed. The number of covariates was five for CL and two for FD, as determined in our previous report19. Empirical threshold values at the 5% level for each trait were determined using 1000 permutation tests38. In addition, the joint data were subjected to genome-wide composite interval mapping (GCIM) using QTL.gCIMapping v3.439. Additive (a) and dominance effects (d) were estimated using the following equations:

where A and B are the genotype of parents, and AA, AB, and BB represent the average of a phenotype in each genotype.

Epistasis analysis

Significant epistasis was identified in two steps. First, QTLNetworkv2.2 was used to detect candidate interactions between QTLs using mixed composite interval mapping at a significance level of 0.1%, determined by 10,000 permutation tests40. Second, the candidate interactions were tested using a multiple regression model with the fitqtl function in R/qtl. The model uses the following equation:

where QTLi is the detected ith single QTL, n is the number of detected single QTLs, (QTL1×QTL2)c is the detected cth QTL interaction, m is the number of candidate QTL interactions detected in the first step, and e is the residual value. Drop-one-term analyses at the 5% significance level were used to test each term. Significant interactions between the two methods were considered as epistatic QTLs.

QTL-by-environment interaction analysis

Interactions between significant single or epistatic QTLs and environment were tested using the following model:

where QTLi is the detected ith single QTL, n is the number of detected single QTLs, E is the environmental effect for each year, (QTL1 × QTL2)c is the significant cth QTL interaction, m is the number of QTL interactions, (QTLi × E) and (QTL1 × QTL2 × E) are the interactions between single or epistatic QTLs and environment, and e is the residual value. In this analysis, raw phenotypic data were used, and the analysis of variance was conducted. The genotypes of the nearest marker to each QTL were considered the genotypes of those QTLs.

Validation of the genetic effect using a heterozygous inbred family and a near-isogenic line

The genetic effect of the QTL (qCL-6b/qFD-6b, see Results) was validated using a heterozygous inbred family (HIF) developed by backcrossing F1 (MS79 × 74LH3213) with 74LH3213, followed by selfing, as described by Hashimoto et al. (2021). The BC1F5 population (n = 67) was cultivated at the Togo Field Science and Education Center of Nagoya University (Aichi, Japan) in 2020, and genomic DNA was extracted from the leaves using the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide extraction method41 with modifications according to Hashimoto et al. (2021). These samples were genotyped using 139 DNA markers (Supplementary Table S1), and an individual was heterozygous for qCL-6b/qFD-6b and homozygous at the dominant allele for the five genes associated with heterosis. The progeny (BC1F6, n = 94) were cultivated in 2021 under the same experimental design described by Hashimoto et al. (2021). CL was measured from the ground to the panicle neck, and FD was the number of days from sowing to flowering of the main stem. The HIF was genotyped using the nearest marker (SB3481) to qCL-6b/qFD-6b (Supplementary Table S1).

The genetic effect of qCL-7b/Dw3 (see Results) was validated using a near-isogenic line (NIL). The parental varieties were bmr-6 with a non-functional allele (dw3) and a duplication in exon 5, as reported by Multani et al. (2003), and SIL-05 (Dw3). The resultant F1 from the cross between the varieties consisted of five successive backcrosses with SIL-05, and plants heterozygous for Dw3 were detected using marker-assisted selection. Whole-genome genotyping was conducted in the BC5F2 generation using 81 DNA markers (Supplementary Table S3). We evaluated the CL in the 57 plants of BC5F2 generation in 2020 and 86 plants of BC5F3 generation in 2021, respectively. Climate data (temperature and precipitation) for 2020 and 2021 for Toyota City near our farm were downloaded from the Japan Meteorological Agency.

Sequence comparison of candidate genes

To compare candidate gene alleles, we resequenced MS79 and 74LH3213 using DNBSEQ-500 (MGI tech, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China). DNA was extracted from the two varieties using the method described above. These samples were sequenced with a 150 bp pair-end and ~ 7G clean data (10×coverage). These short reads were mapped to the BTx623 (v5.1) genome using BWA-mem2 (v2.2.1)42. After marking duplicates with the MarkDuplicates function in picard, SNP (single nucleotide polymorphism) and INDEL (insertion and deletion) calling were performed with the HaplotypeCaller function in the Genome Analysis Toolkit v4.1.8.143, and detected variants were filtered with Variantfiltration (SNP: QUAL < 30.0, SOR > 3.0, FD > 60.0, MQ < 40.0, MQRankSum < −12.5 and ReadPosRankSum < −8.0, INDEL: QUAL < 30.0, FD > 200.0 and ReadPosRankSum < −20.0). Variant quality score recalibration was conducted using the BaseRecalibrator and ApplyBQSR functions. Subsequently, variant calling and filtering were performed under similar conditions. Multi-allelic variants were removed using vcftools v1.1.1644.

Variants in the coding sites of two candidate genes, SbPRR37 and Dw2, of qCL-6b/qFD-6b (see Results) were extracted. Functional alleles from 100M (SbPRR37, GenBank accession no. JF801188) and BTx623 (Dw2, v5.1 in Phytozome) were used for comparison. Sequence alignments were performed using Clustal Omega45.

Statistical analysis and visualization

Basic statistical analyses were performed using R software (v. 4.1.0). Tukey’s test was conducted using the emmeans package (https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1080/00031305.1980.10483031?needAccess=true). A circos plot illustrating the QTL interactions was generated using shinyCircos-V2.046. Additional visualizations, including boxplots, histograms, and scatter plots, were created using the ggplot2 package47. A graphical genotype was created using GenoSee48.

Results

Single-QTL analysis for the joint F2 population

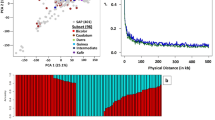

A single-QTL analysis was performed to evaluate the statistical power of QTL detection using the joint F2 population of the progeny of the Japanese hybrid variety that represents the notable heterosis (Fig. 1A). The QTLs for CL and FD were detected at six and four loci, respectively (Fig. 1B and C; Table 1, Supplementary Fig. S2). When we examined the effect of marker genotype missing rate on linkage construction and QTL detection, no significant differences were found between the 20% and 50% thresholds for marker genotype missing rate (Supplementary Fig. S2). The QTLs detected by CIM were consistent with those obtained using GCIM (Supplementary Fig. S3). Among the QTLs, five for CL and two for FD corresponded to the loci reported by Hashimoto et al. (2021) (Table 1). By contrast, qCL-6b, qFD-2, and qFD-6b were first detected in the present study (Fig. 1B and C; Table 1). The joint population demonstrated enhanced statistical power because it enabled the detection of these minor QTLs, which exhibited smaller genetic effects than previously identified QTLs (Table 1).

Six loci for the heterosis of culm length detected in single-quantitative trait locus (QTL) analysis. (A) Plant stature of F1 hybrid variety ‘Tentaka’ and its parental lines MS79 (female parent) and 74LH3213 (male parent). Plants were cultivated in two rows per hill. Red bars represent one meter. (B–C) Logarithm of the odds (LOD) curves of single-QTL analysis for culm length (CL) (B) and flowering days (FD) (C) using the joint F2 data. (D–E) Genetic effects of qCL-6b (D) and qFD-6b (E). The vertical axes indicate residual values regressed by year. The horizontal axis shows the genotypes of the DNA marker, which is the nearest QTL. “A” and “B” are the alleles of MS79 and 74LH3213, respectively. Different letters on the violin plots indicate significant differences between samples in the Tukey’s test. The black dots in the violin plots represent the average values in each genotype.

Three loci were identified as co-located between CL and FD (qCL-1 and qFD-1, qCL-6a and qFD-6a, qCL-6b and qFD-6b; Fig. 1B and C; Table 1). Therefore, CL was responsible for the six QTLs corresponding to internode elongation and FD, suggesting that they are important for the heterosis in the cross. Based on previous allele comparisons between parental lines19, the genes responsible for the five QTLs were identified as Ma3/SbPhyB (qCL-1/qFD-1), Ma6/SbGhd7 (qCL-6a/qFD-6a), Dw7a (qCL-7a), Dw3 (qCL-7b), and Dw1 (qCL-9). The newly identified qCL-6b/qFD-6b exhibited the highest d/a ratio among the QTLs, with dominance values of 5.29 for CL and 25.8 for FD (Fig. 1D and E; Table 1). These results indicate that qCL-6b/qFD-6b exhibits overdominance or pseudo-overdominance. By contrast, as heterozygous individuals at qFD-6b displayed a bimodal distribution (Fig. 1E), the estimated genetic effects of qCL-6b/qFD-6b were influenced by other loci. Notably, qCL-7b exhibited a d/a ratio > 1 (Table 1).

Epistatic QTL analysis

To identify genome-wide epistasis between the two QTLs, we performed the following two-step analysis: detection of candidate QTL interactions using the QTL network and validation using the fitqtl function in R/qtl35 (Table 2 and Supplementary Table S4 and S5). Two and three QTL interactions were identified for each trait: qCL-1 × qCL-6a and qCL-1 × qCL-9 for CL and qFD-1 × qFD-6a, qFD-1 × qFD-6b and qFD-2 × qFD-6b for FD (Fig. 2; Table 2). All QTL interactions were combinations of the same loci detected by single-QTL analysis, and qCL-1 × qCL-6a and qFD-1 × qFD-6a were co-localized (Fig. 2; Table 2). The three QTL interactions showed additive × additive, additive × dominance, and dominance × additive genetic effects, except for qFD-1 × qFD-6b and qFD-2 × qFD-6b (Fig. 2B–D; Table 2). The three QTL interactions indicated larger genetic effects in the homozygous or heterozygous for the dominant allele genetic background than the homozygous for the recessive allele genetic background (Fig. 2B–D). In qFD-1 × qFD-6b and qFD-2 × qFD-6b, the phenotype of heterozygotes for qFD-6b was higher than that of the homozygotes, depending on the genetic background, similar to the results of the single-QTL analysis (Figs. 1D and 2E–F). The dominance × dominance interaction of qFD-1 × qFD-6b and qFD-2 × qFD-6b seemed to reflect the differences in genetic effects between genetic backgrounds. Thus, the genetic effect of overdominance/pseudo-overdominance of qFD-6b depended on the genotypes of qFD-1 and qFD-2. However, the phenotypic variation explained (PVE) by each QTL exceeded 9% for all except qCL-6b and qFD-2, whereas that by QTL interactions was limited to a maximum of only 3.8%. Consequently, the contribution of QTL interactions to heterosis was limited (Supplementary Table S5).

Epistatic quantitative trait loci (QTLs) detected in the joint F2 population. (A) Circos plot for QTL interactions. The outside circle shows a linkage map, and the second and third layers indicate confidence intervals detected by single-QTL analysis. The center lines connecting QTLs are significant interactions. Red and blue represent the results of CL and FD, respectively. (B–F) Genetic effects of QTL interactions detected for CL (B–C) and FD (D–F). These vertical axes show residual values regressed on trait values by year effects. These horizontal axes and line colors represent genotypes of the nearest markers of the QTLs. “A” and “B” are the alleles of MS79 and 74LH3213, respectively. For corresponding genes of QTLs, the genotype of the marker indicates whether it is a dominant or recessive allele. Error bars indicate the standard errors. Different letters in the line graphs indicate significant differences in the Tukey’s test among genotypes of one QTL on the horizontal axis for each genotype of another QTL.

The QTL-by-environment interaction was detected only in qFD-6a ×E (Supplementary Table S6). The PVE was only 0.4%, indicating that the single or epistatic QTL-by-environment interactions had minimal effects on the heterosis.

Verification of pseudo-overdominance for qCL-6b/qFD-6b and qCL-7b

Given its location approximately 30 cM from qCL-6a/qFD-6a/SbGhd7, the qCL-6b/qFD-6b locus was assumed to exhibit pseudo-overdominance (Table 1). In this study, we verified the influence of the linkage between the two QTLs for FD that showed the highest d/a (Table 1). Furthermore, we focused on qFD-1/SbPhyB genotypes because qFD-1 × qFD-6b influenced the overdominance/pseudo-overdominance effect of qFD-6b (Fig. 2E), and qFD-1/SbPhyB had a greater genetic effect than qFD-2 (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. S4). Plants harboring the homozygous allele of the female parent for qFD-6b (qFD-6b_AA) were hitchhiked by the recessive allele homozygous for qFD-6a/SbGhd7 at a higher frequency than plants harboring other alleles (Fig. 3A). Two QTLs, qFD-6a/SbGhd7 and qFD-1/SbPhyB, are completely or incompletely dominant in inheritance19 (Table 1). Next, phenotypic segregation at qFD-6b was studied in the functional genetic backgrounds of two QTLs (qFD-1/SbPhyB and qFD-6a/SbGhd7 carrying homozygous or heterozygous dominant alleles) or in a non-functional background (homozygous recessive alleles). Plants on the functional background showed significant differences between qFD-6b_BB and other genotypes, whereas plants on the non-functional background showed lower values than those on the functional background and no significant difference between qFD-6b_AA and qFD-6b_BB (Fig. 3B). These results suggested that the inheritance pattern of qFD-6b was complete dominance in the functional background (Fig. 3B). To verify the completely dominant inheritance of qCL-6b/qFD-6b, we used a HIF in BC1F6 that segregated in qCL-6b/qFD-6b candidate region and homozygous for the dominant alleles at other QTLs (Fig. 3C). The inheritance manner of qCL-6/qFD-6b indicated complete dominance, with the female-parent allele being dominant over the male-parent allele (Fig. 3D and E).

Influence on the genetic effects of qCL-6b/qFD-6b due to linkage with qCL-6a/qFD-6a/SbGhd7. (A) Linkage between qFD-6b and qFD-6a/SbGhd7. The ratio of plants homozygous at the recessive alleles for qFD-1/SbPhyB and qFD-6a/SbGhd7 in the genotypes of qFD-6b is shown. The horizontal axis indicates the genotypes of the nearest marker of qFD-6b. “A” and “B” are the alleles of MS79 and 74LH3213, respectively. qFD-1_B and qFD-6a_A indicate the recessive alleles of SbPhyB and SbGhd7, respectively, and the plants homozygous for each recessive allele (qFD-1_BB or qFD-6a_AA) are approximately early flowering. Red, grey, and yellow bars show either recessive allele for qFD-1/SbPhyB and qFD-6a/SbGhd7. The numbers in the bars indicate the ratio of plants having each genetic background. The number of plants with each genotype of qFD-6b is shown on the bar plots. (B) Inheritance manner of qFD-6b in the functional genetic background. The left and right panels show boxplots classified by qFD-6b genotypes in the functional (only blue plants of panel A) and non-functional (plants other than blue in panel A) genetic backgrounds, respectively. The vertical axis indicates residual values regressed by year. (C) Graphical genotype of a parental plant used in the validation of the genetic effects of qCL-6b/qFD-6b. The plant was selected from the BC1F5 generation, which was selfed after being backcrossed with 74LH3213 for F1 (MS79 × 74LH3213). Blue and yellow segments indicate 74LH3213 and MS79, respectively. Black bars show DNA markers, and red arrows show the positions of five genes previously reported as heterosis factors (Hashimoto et al. 2021). (D–E) Relationship between qCL-6b/qFD-6b and CL (D) or FD (E) in the BC1F6 generation. The horizontal axes show the genotypes of the DNA marker (SB3481), which is the nearest qCL-6b/qFD-6b. “A” and “B” are the alleles of MS79 and 74LH3213, respectively. Different letters on the boxplots indicate significant differences between samples in the Tukey’s test.

d/a ratios beyond one were also detected at the qCL-7b/Dw3 locus (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. S4D). Two genes (qCL-7a/Dw7a and qCL-7b/Dw3) are linked in the repulsion phase in this region, suggesting pseudo-overdominance8,19. The inheritance pattern of qCL-7b/Dw3 was estimated to be completely dominant in both genetic backgrounds when the joint F2 population was divided into two groups using the nearest marker of qCL-7b/Dw3 (Supplementary Fig. S5A and S5B). In the validation experiment with a NIL harboring the heterozygous allele for Dw3 derived from crossing between bmr-6 (dw3) and SIL-05 (Dw3), the population with a segregating Dw3 locus in 2020 showed slightly higher CL than NILs with homozygosity, whereas the result in 2021 indicated complete dominance (Supplementary Fig. S5C–S5E). The accumulated temperature and accumulated precipitation during the growth stage in 2020 were higher than those in 2021 (Supplementary Fig. S6). These differences might explain the slightly higher heterozygosity in 2020 than in 2021. However, Li et al. (2015) reported that the inheritance manner of Dw3 is completely dominant. Therefore, qCL-7b/Dw3 was almost completely dominant, suggesting that the locus on chromosome 7 was pseudo-overdominant, which was induced by the repulsive linkage between Dw7a and Dw3.

Identification of genes responsible for qCL-6b/qFD-6b

Ma1/SbPRR37 and Dw2 are located in the qCL-6b/qFD-6b confidence region31,33. The coding sites of the two genes were compared using resequencing data from both parental lines. For Ma1/SbPRR37, the male parent allele (74LH3213) exhibited a single-base deletion in the fourth exon (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. S7). This mutation caused a frameshift, which led to a premature stop codon (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. S7). This allele has been previously reported to be a loss-of-function allele31. A comparison of the allele of female parent with 100 M known as a functional allele revealed one nonsynonymous mutation in the female parent allele (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. S7). By contrast, the male parent allele of Dw2 was identical to the BTx623 allele known as a functional allele33 (Supplementary Fig. S8 and S9). These results suggest that Ma1/SbPRR37 is the most likely candidate gene responsible for qCL-6b/qFD-6b.

Discussion

Using the joint F2 population, we newly identified qCL-6b/qFD-6b associated with the hybrid vigor of the CL of a Japanese F1 variety. Heterosis of the CL in the F1 variety is probably explained by six genes that regulate internode elongation and flowering based on previous and our studies (qCL-7a/Dw7a, qCL-7b/Dw3, qCL-9/Dw1, qCL-1/qFD-1/SbPhyB, qCL-6a/qFD-6a/SbGhd7, and qCL-6b/qFD-6b/SbPRR37) (Table 1; Fig. 1). Based on previous and our studies, these genes are the most likely to be responsible for the detected QTLs19,20,21,22,23,27,28,29,30,31 (Supplementary Table S7). In our previous study, SbPRR37 was predicted to influence hybrid vigor but was not detected as a QTL19. This result can be attributed to the number of individuals in the F2 population. By leveraging a joint F2 population of over 600 plants, we achieved higher statistical power in the single-QTL analysis. Indeed, qCL-6b/qFD-6b and qFD-2 had smaller genetic effects on CL and FD than previously detected QTLs19 (Table 1). The genetic effect of qCL-6b/qFD-6b was validated using the HIF, and Ma1/SbPRR37 was identified as the gene responsible for qCL-6b/qFD-6b. This approach of constructing a joint F2 population proved valuable for QTL analysis.

Pseudo-overdominace for CL and FD was observed in this study. Of the six loci associated with the heterosis for CL, four were completely or incompletely dominant (Table 1; Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. S3). Conversely, two QTLs (qCL-6b/qFD-6b/SbPRR37 and qCL-7b/Dw3) with d/a > 1 were also detected on chromosomes 6 and 7. A previous study reported pseudo-overdominance for sorghum plant height due to two QTLs (qHT7.1 and Dw3) linked in the repulsion phase on chromosome 78. The gene Sobic.007G137101, which encodes an R2R3-type MYB transcription factor, corresponds to qHT7.1 and qCL-7a/Dw7a19,27,28. The qCL-7b/Dw3 region exhibited d/a = 2.85 but was nearly completely dominant when Dw3 was segregated alone, suggesting pseudo-overdominance owing to the repulsion-phase linkage between Dw7a and Dw3 in the female and male parents (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. S4). In addition, qCL-6b/qFD-6b/SbPRR37 had the highest d/a (CL: 5.29, FD: 25.8) detected first in this study but showed complete dominance by the following precise study, suggesting that it is also pseudo-overdominant (Table 1; Fig. 3). Therefore, our results indicate that the high d/a ratios beyond one on the two QTLs are attributed to two genes linked in the repulsion phase.

Although qCL-6a/qFD-6a/SbGhd7 and qCL-6b/qFD-6b/SbPRR37 were greater than 40 Mb, they were linked at approximately 30 cM and exhibited repulsion-phase linkage (Table 1; Fig. 3B). Both QTLs were detected across the centromere, suggesting that the pseudo-overdominance was caused by the two QTLs in the pericentromeric region, where recombination occurs at a low frequency49. McMullen et al. (2009) speculated that pseudo-overdominance is a major factor in maize heterosis because it maintains higher heterozygosity near the centromeres than in other regions in inbred lines50. This hypothesis is supported by the different fixation of alleles in the pericentromeric regions between the Dent and Flint heterotic groups51. In fact, most QTLs associated with heterosis for yield in maize are located on pericentromeric regions10,52. For example, the QTL on chromosome 5 comprises at least two causal genes in the repulsion phase linkage, indicating pseudo-overdominance9. Although whether pericentromeric regions mainly contribute to heterosis in sorghum remains unclear, this study provides the first evidence for this contribution. Future investigations into the genetic mechanisms of heterosis in other crops should also consider the pericentromeric regions in heterotic groups.

A detailed analysis of epistatic effects revealed two and three QTL interactions for CL and FD, respectively (Table 2; Fig. 2). The epistatic effects of CL (qCL-1/qFD-1/SbPhyB × qCL-6a/qFD-6a/SbGhd7 and qCL-1/qFD-1/SbPhyB × qCL-9/Dw1) showed that genetic effects were enhanced when these two genes were dominant (Fig. 2B and C). However, their epistatic effects were weaker than those of most QTLs (Supplementary Table S1 and 2), suggesting that their contribution to the heterosis is limited.

Most QTL interactions were detected between FD genes, indicating a relationship between these genes in the sorghum flowering regulatory pathway (Fig. 2; Table 2). Epistasis associated with flowering was observed in qCL-1/qFD-1/SbPhyB × qCL-6a/qFD-6a/SbGhd7, qFD-1/SbPhyB × qFD-6b/SbPRR37, and qFD-2/Ma2 × qFD-6b/SbPRR37. According to the sorghum flowering regulatory pathway, SbPhyB acts upstream of SbGhd7 and SbPRR3730,31, and Ma2 delays flowering under LD by enhancing the expression of SbPRR37 and SbCO32. The genetic effect of qCL-1/qFD-1/SbPhyB × qCL-6a/qFD-6a/SbGhd7 was the strongest epistasis detected in this study, and only this epistasis was detected in both CL and FD (Fig. 2; Table 2). When one of the two genes (SbPhyB or SbGhd7) was a recessive allele, the other genetic effect was suppressed (Fig. 2B and D). Therefore, the recessive alleles of the two genes found in each female and male parents, respectively, could play an important role in a requirement for parental varieties, i.e., simultaneous early flowering date necessary for naturally crossing.

The second epistasis for CL (qCL-1/qFD-1/SbPhyB × qCL-9/Dw1) may indicate a relationship between red/far-red receptor and BR signaling components. In the sbphyB genetic background (sbphyB sbphyB at qCL-1) used in the present study, the genetic effect of qCL-9/Dw1 was weaker than that in the SbPhyB genetic background (SbPhyB sbphyB or SbPhyB SbPhyB at qCL-1) (Fig. 2C). Dw1, a positive regulator of BR signaling component, interacts with and inhibits the nuclear localization of BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE 2 (BIN2) to promote the nuclear localization of BRASSINAZOLE-RESISTANT1 (BZR1)21. The expression of Dw1 is downregulated via feedback regulation by brassinolide (BL) treatment. Meanwhile, PhyB activated by red light interacts with dephosphorylated BRI1-EMS-SUPPRESSOR1 (BES1) and inhibits its transcriptional activity in Arabidopsis53,54. BES1/BZR1, a master regulator of BR-related gene expression, is a target of BIN2 phosphorylation53. Thus, the epistasis between Dw1 and SbPhyB could be controlled by a feedback regulation from BL or BES1/BZR1 to both Dw1 and SbPhyB. Further studies considering plant physiological aspects are necessary to explain the epistasis.

In addition, although a synergistic effect was reported in a double-mutant NIL (NIL-dw1dw3) against the gain-of-function background of Dw1 and Dw3, epistasis between these genes was not detected in the present study22. Advanced backcrossed lines, such as chromosomal substitution lines and NIL, have potentially detected QTLs that could not be detected in an F2 population55. The results of this study may reflect differences in statistical power between F2 populations and NILs.

All identified QTLs showed positive completely dominant or incompletely dominant inheritance, and the contribution of epistatic QTLs to the heterosis was limited. Hence, we propose a six-gene model suggesting that the heterosis for CL in an F1 sorghum hybrid can be mainly explained by the dominance model and partially explained by the epistasis model (Fig. 5). Many QTLs have been detected in the heterosis for plant height in various crops, and the six-gene model is comparatively simple. Previous studies on maize plant height have detected 8–21 QTLs using populations derived from three single-cross populations, and 18 QTLs have been reported using 30 F1 populations consisting of 8,652 combinations obtained by crossing 1,428 maternal lines and 30 paternal testers10,16,56,57. More than 20 QTLs have been reported using F2 populations from 17 representative hybrid rice crosses12. Genes responsible for some of these QTLs have been identified; however, most of the remaining QTLs are unknown. QTLs associated with sorghum plant height have also been reported across genomes58,59,60,61,62. However, in the present study, only six genes contributed to the heterosis, although the plant height of the F1 variety used was three times higher than that of the parents (Table 1; Fig. 1A, Supplementary Fig. S1). Five of these genes (Dw1, Dw3, SbPRR37, SbPhyB, and SbGhd7) were included in the 10 genes that are important for grain sorghum breeding17,18. This finding suggests that the genes that contribute to breeding have a large genetic effect and that if all the genes function, sorghum will reach 4 m in height, as in the F1 cultivar. Thus, the proposed six-gene model in the present study has a great advantage for the high biomass F1 breeding of sorghum (Fig. 5). In conclusion, the proposed model showed that the six genes contributed to the heterosis of CL in Poaceae through the increased number and length of internodes by late flowering. Further studies should verify whether this model can be applied to the heterosis of CL in other crops.

Genetic model of the heterosis for sorghum culm length (CL). Six genes (Dw1, Dw3, Dw7a, SbPhyB, SbGhd7, and SbPRR37) contributed to the heterosis for the CL of F1 variety ‘Tentaka’. The dark and thin color of six genes indicate dominant and recessive alleles, respectively. The thick lines in the circles represent the linkage between genes, resulting in pseudo-overdominance in F1 due to the repulsive linkages. The inner lines represent epistasis, and the dotted lines show repressed relationships. The female parent (MS79) carries dw7a and sbghd7, and the male parent carries dw1, dw3, sbphyB, and sbprr37. The F1 hybrid has all dominant alleles of six genes and positive epistasis, but the effects of epistatic interactions are weaker than those of single QTLs. Therefore, the heterosis is explained mainly by the dominance model but partially by the epistasis model.

This study analyzed the genetic mechanisms underlying the heterosis for CL in F1 hybrid sorghum. The following three points were identified: (1) SbPRR37 on chromosome 6 contributed to the heterosis, (2) SbGhd7 and SbPRR37 were linked in the repulsion phase in the pericentromeric region and showed pseudo-overdominance, and (3) all identified QTLs showed positive complete dominant or incomplete dominant inheritance. Although several epistatic QTLs were identified in this study, their contributions to the heterosis were limited. Moreover, this study does not provide evidence that overdominance effects do not exist. The population crossing between i5 and its parents must be analyzed to obtain further insights. Nevertheless, the results of this study revealed that the dominance and epistatic effects contributed significantly to the heterosis, suggesting that the overdominance effect, if present, is limited.

In conclusion, a six-gene model was considered for the heterosis, which was explained mainly by the dominance model and partially by the epistasis model (Fig. 5). These results provide insights into the genetic mechanisms of heterosis in high-biomass sorghum. This study could serve as a reference for the genetic design of high-biomass F1 varieties.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the Japan Sequence Read Archive (DRA) repository, DRA021679 (sample ID, 74LH3213: DRR706008 and MS79: DRR706009). DRA021679 will be included in the DRA search system shortly.

References

Miyaji, N., Fujimoto, R. & Hybrid Vigor Importance of epigenetic processes and consequences for breeding. Adv. Bot. Ress. 88, 247–275 (2018).

Duvick, D. N. Biotechnology in the 1930s: the development of hybrid maize. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2, 69–74 (2001).

Li, J., Luo, X. & Zhou, K. Research and development of hybrid rice in China. Plant. Breed. 143, 96–104 (2024).

Goff, S. A. A unifying theory for general Multigenic heterosis: energy efficiency, protein metabolism, and implications for molecular breeding. New. Phytol. 189, 923–937 (2011).

Jones, D. F. (ed.) Genetics in Plant and Animal Improvement (Wiley, 1925).

Shull, G. H. Hybrid seed corn. Science 103, 547–550 (1946).

Powers, L. An expansion of jones’s theory for the explanation of heterosis. Am. Nat. 78, 275–280 (1944).

Li, X., Li, X., Fridman, E., Tesso, T. T. & Yu, J. Dissecting repulsion linkage in the dwarfing gene Dw3 region for sorghum plant height provides insights into heterosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 11823–11828 (2015).

Graham, G. I., Wolff, D. W. & Stuber, C. W. Characterization of a yield quantitative trait locus on chromosome five of maize by fine mapping. Crop Sci. 37, 1601–1610 (1997).

Stuber, C. W., Lincoln, S. E., Wolff, D. W., Helentjaris, T. & Lander, E. S. Identification of genetic factors contributing to heterosis in a hybrid from two elite maize inbred lines using molecular markers. Genetics 132, 823–839 (1992).

Chen, Z. J. Genomic and epigenetic insights into the molecular bases of heterosis. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14, 471–482 (2013).

Huang, X. et al. Genomic architecture of heterosis for yield traits in rice. Nature 537, 629–633 (2016).

Krieger, U., Lippman, Z. B. & Zamir, D. The flowering gene SINGLE FLOWER TRUSS drives heterosis for yield in tomato. Nat. Genet. 42, 459–463 (2010).

Larièpe, A. et al. The genetic basis of heterosis: multiparental quantitative trait loci mapping reveals contrasted levels of apparent overdominance among traits of agronomical interest in maize (Zea Mays L). Genetics 190, 795–811 (2012).

Shen, G., Zhan, W., Chen, H. & Xing, Y. Dominance and epistasis are the main contributors to heterosis for plant height in rice. Plant. Sci. 215–216, 11–18 (2014).

Xiao, Y. et al. The genetic mechanism of heterosis utilization in maize improvement. Genome Biol. 22, 148 (2021).

Rooney, W. L. & Aydin, S. Genetic control of a Photoperiod-Sensitive response in Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench. Crop Sci. 39, 397–400 (1999).

Quinby, J. R. The genetics of sorghum improvement. J. Hered. 66, 56–62 (1975).

Hashimoto, S. et al. The dominance model for heterosis explains culm length genetics in a hybrid sorghum variety. Sci. Rep. 11, 4532 (2021).

Hilley, J., Truong, S., Olson, S., Morishige, D. & Mullet, J. Identification of Dw1, a regulator of sorghum stem internode length. PLoS ONE. 11, e0151271 (2016).

Hirano, K. et al. Sorghum DW1 positively regulates brassinosteroid signaling by inhibiting the nuclear localization of BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE 2. Sci. Rep. 7, 126 (2017).

Yamaguchi, M. et al. Sorghum Dw1, an agronomically important gene for lodging resistance, encodes a novel protein involved in cell proliferation. Sci. Rep. 6, 28366 (2016).

Multani, D. S. et al. Loss of an MDR transporter in compact stalks of maize br2 and sorghum dw3 mutants. Science 302, 81–84 (2003).

Noh, B., Murphy, A. S. & Spalding, E. P. Multidrug resistance –like genes of Arabidopsis required for auxin transport and auxin-Mediated development. Plant. Cell. 13, 2441–2454 (2001).

Wei, H. et al. Structural insights into brassinosteroid export mediated by the Arabidopsis ABC transporter ABCB1. Plant. Commun. 6, 101181 (2025).

Ying, W. et al. Structure and function of the Arabidopsis ABC transporter ABCB19 in brassinosteroid export. Science 383, eadj4591 (2024).

Jiao, S. et al. Parallel tuning of semi-dwarfism via differential splicing of Brachytic1 in commercial maize and smallholder sorghum. New. Phytol. 240, 1930–1943 (2023).

Mu, Q. et al. A MYB transcription factor underlying plant height in sorghum qHT7.1 and maize Brachytic 1 loci. Plant J. Tpj 17111 (2024).

Murphy, R. L. et al. Ghd7 (Ma6) represses sorghum flowering in long days: Ghd7 alleles enhance biomass accumulation and grain production. Plant Genome 7, 1–10 (2014).

Yang, S. et al. Sorghum phytochrome B inhibits flowering in long days by activating expression of SbPRR37 and SbGHD7, repressors of SbEHD1, SbCN8 and SbCN12. PLoS ONE. 9, e105352 (2014).

Murphy, R. L. et al. Coincident light and clock regulation of pseudoresponse regulator protein 37 (PRR37) controls photoperiodic flowering in sorghum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 108, 16469–16474 (2011).

Casto, A. L. et al. Maturity2, a novel regulator of flowering time in sorghum bicolor, increases expression of SbPRR37 and SbCO in long days delaying flowering. PLoS ONE. 14, e0212154 (2019).

Hilley, J. L. et al. Sorghum Dw2 encodes a protein kinase regulator of stem internode length. Sci. Rep. 7, 4616 (2017).

Oliver, J. et al. The AGCVIII kinase Dw2 modulates cell proliferation, endomembrane trafficking, and MLG/xylan cell wall localization in elongating stem internodes of Sorghum bicolor. Plant. J. 105, 1053–1071 (2021).

Broman, K. W., Wu, H., Sen, Ś. & Churchill, G. A. R/qtl: QTL mapping in experimental crosses. Bioinformatics 19, 889–890 (2003).

Kosambi, D. The estimation of map distances from recombination values. Ann. Eugen 12, 172–175 (1943).

Zeng, Z. B. Precision mapping of quantitative trait loci. Genetics 136, 1457–1468 (1994).

Churchill, G. A. & Doerge, R. W. Empirical threshold values for quantitative trait mapping. Genetics 138, 963–971 (1994).

Zhou, Y. H., Li, G. and Zhang, Y. M. A compressed variance Component mixed model framework for detecting small and linked QTL-by-environment interactions. Brief. Bioinform. 23, 1–18 (2022).

Yang, J. et al. QTLNetwork: mapping and visualizing genetic architecture of complex traits in experimental populations. Bioinformatics 24, 721–723 (2008).

Murray, M. G. & Thompson, W. F. Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant. DNA Nucleic Acids Res. 8, 4321–4325 (1980).

Md, V., Misra, S., Li, H. & Aluru, S. Efficient Architecture-Aware Acceleration of BWA-MEM for Multicore Systems. In IEEE Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium (2019).

DePristo, M. A. et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat. Genet. 43, 491–498 (2011).

Danecek, P. et al. The variant call format and vcftools. Bioinformatics 27, 2156–2158 (2011).

Sievers, F. et al. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using clustal Omega. Mol. Syst. Biol. 7, 539 (2011).

Wang, Y. et al. shinyCircos-V2.0: leveraging the creation of circos plot with enhanced usability and advanced features. iMeta 2, e109 (2023).

Wickham, H. & Sievert, C. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis Second (Springer, 2016).

Hashimoto, S. GenoSee: a novel visualization tool for graphical genotypes. Breed. Sci. 74, 454–461 (2024).

Wang, Y. & Copenhaver, G. P. Meiotic recombination: mixing it up in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 69, 577–609 (2018).

McMullen, M. D. et al. Genetic properties of the maize nested association mapping population. Science 325, 737–740 (2009).

Technow, F. et al. Genome properties and prospects of genomic prediction of hybrid performance in a breeding program of maize. Genetics 197, 1343–1355 (2014).

Schön, C. C., Dhillon, B. S., Utz, H. F. & Melchinger, A. E. High congruency of QTL positions for heterosis of grain yield in three crosses of maize. Theor. Appl. Genet. 120, 321–332 (2010).

Nolan, T. M., Vukašinović, N., Liu, D., Russinova, E. & Yin, Y. Brassinosteroids: multidimensional regulators of plant Growth, Development, and stress responses. Plant. Cell. 32, 295–318 (2020).

Wu, J. et al. PhyB interacts with BES1 to regulate brassinosteroid signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant. Cell. Physiol. 60, 353–366 (2019).

Nagata, K. et al. Advanced backcross QTL analysis reveals complicated genetic control of rice grain shape in a Japonica × indica cross. Breed. Sci. 65, 308–318 (2015).

Frascaroli, E. et al. Classical genetic and quantitative trait loci analyses of heterosis in a maize hybrid between two elite inbred lines. Genetics 176, 625–644 (2007).

Lu, H., Romero-Severson, J. & Bernardo, R. Genetic basis of heterosis explored by simple sequence repeat markers in a random-mated maize population. Theor. Appl. Genet. 107, 494–502 (2003).

Dweikat, I., Braun, D., Benjamin, B. & Teingtham, K. Detection of reproducible QTL associated with bioenergy traits in sorghum across several growing environments. Euphytica 219, 70 (2023).

Felderhoff, T. J. et al. QTLs for Energy-related traits in a sweet × grain sorghum [ Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench] mapping population. Crop Sci. 52, 2040–2049 (2012).

Guan, Y. et al. QTL mapping of bio-energy related traits in sorghum. Euphytica 182, 431–440 (2011).

Murray, S. C. et al. Genetic improvement of sorghum as a biofuel feedstock: II. QTL for stem and leaf structural carbohydrates. Crop Sci. 48, 2180–2193 (2008).

Ritter, K. B. et al. Identification of QTL for sugar-related traits in a sweet × grain sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L. Moench) Recombinant inbred population. Mol. Breed. 22, 367–384 (2008).

Funding

This work was partially supported by the Japan Science and Technology-Mirai Program Grant No. JPMJMI17EG; the Moonshot Research and Development Program (JPNP18016) and the NEDO Feasibility Study Program (JPNP14004), commissioned by the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO); and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI, Grant No. 22K14868 and 25K18218.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Designed experiments: SO, SH, SK, TS; Phenotyping: SO, TK, SH; Genotyping: SA-N, KO-S, SH; Data analysis/QTL analysis: SO; Wrote the manuscript: SO, TS. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Okada, S., Hashimoto, S., Kikuchi, T. et al. Six-gene model underlying heterosis for culm length and flowering date in sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench). Sci Rep 15, 39880 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23675-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23675-8