Abstract

This study introduces a novel Variable Sample Size Exponentially Weighted Moving Average (VSS-EWMA) control chart for monitoring the coefficient of variation, termed as Dynamic Adaptive CV (DACV) chart. Tailored for dynamic production settings where both the process mean and variability are subject to change, the proposed chart integrates an adaptive sampling strategy within the EWMA framework, allowing real-time adjustment of sample size in response to process conditions. Comparative analysis with the conventional Fixed Sample Size EWMA (FEWMA) chart reveals that DACV chart exhibits enhanced sensitivity in detecting small to moderate shifts in variability. Its performance is rigorously evaluated using Average Run Length (ARL), Standard Deviation of Run Length (SDRL), and run-length percentiles. Visualizations through heat maps further affirm its robustness across a wide range of shift magnitudes and smoothing parameters. A real-world application using semiconductor manufacturing data demonstrates the practical utility of DACV chart, underscoring its potential in contemporary quality monitoring systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Statistical Process Control (SPC) is an imperative tool in industrial quality measurement that provides measures to identify the variance of non-stable processes. Since its introduction by Shewhart at Bell Labs, who pioneered the use of control charts, such as the upper and lower control limits to identify variations in process parameters such as mean and variance, the discipline has undergone tremendous changes in order to address current and future issues of industry1. The old Shewhart charts show ability to detect large shifts, but do not respond to small to moderate shifts, this limitation led to the development of the memory based charts; the EWMA by Roberts2 and Cumulative Sum (CUSUM) chart by Page3 to deal with more subtle changes in process behavior. The researchers have especially insisted on observing the CV the ratio of standard deviation (S.D) to the mean especially when the mean is not constant. To achieve the same goal, CV can also be used as a standardized indicator of process variability to be utilized in situations where mean and S.D vary at the same time4. This gives the CV control charts application specific to those industries where the proportional shifts among the process parameters are likely to occur (die-casting and clinical measurements)5. Recent trends have been on improving the sensitivity of CV control charts by use of adaptive mechanisms. An example of the later is adaptive EWMA (AEWMA) charts, which dynamically change the smoothing constant to reflect observed changes in order to enhance early detection of change in process behavior6. Nevertheless, even standard AEWMA-CV charts continue to have the problem of poorly detecting the occasional or minor shifts. In this regard, Riaz et al.7 discussed the control chart for the process CV by considering the adaptive smoothing constant. With the use of Monte Carlo simulations, the proposed chart initiates high performance in identifying small differences in variability of processes as compared to the available charts.

Muhammad et al.8 introduced a variable sample size (VSS) EWMA control chart custom-tailored towards controlling the squared CV. The author came up with analytical formulas of the ARL, average sample size (ASS), and an expected ARL (EARL) and later proceeded to devise an optimization procedure to optimize chart parameters. Their findings show that the method can reliably work better than five standard CV monitoring charts. The findings were validated by means of an industrial application in many scenarios. On the same note, Noor-ul-Amin et al.9 created a hybrid control chart that shows the intention of monitoring the process mean and CV simultaneously. The ARL and SDRL evaluation demonstrated that the proposed chart has an improved sensitivity compared with the traditional practices. The practical feasibility of the method was made stronger as it was validated with the real industry data. An adaptive Shewhart control chart containing VSS approach was also suggested to monitor the CV in a manufacturing process together with short-run production in Amdouni et al.10. They got the analytical form of the ARL in a shortened version. Their work also provides a comparative evaluation of it to a traditional fixed sampling rate. Shewhart chart and also back it up with a practical application of the data. Function-based adaptive EWMA (FAEWMA) charts have recently gained attention for their improved sensitivity in CV monitoring. Arshad et al.11 proposed a FAEWMA chart that dynamically adjusts the smoothing parameter to detect small shifts effectively. Later, Arshad et al.12 extended this approach by incorporating measurement errors, demonstrating that the function-based chart maintains strong performance even under data uncertainty. Recent developments in adaptive sampling strategies have further improved the performance of EWMA control charts. Shabbir et al.13 introduced a dynamic sample size EWMA chart based on a piecewise linear function, allowing the sample size to adjust in real-time based on the EWMA statistic.

Adaptive EWMA (AEWMA) charts extend the traditional EWMA framework by dynamically adjusting design parameters in response to process conditions. Such adaptations typically involve modifying the smoothing constant, which controls responsiveness to shifts, or varying the sample size, which balances information gain with resource efficiency. These strategies aim to achieve greater sensitivity to process changes while maintaining robustness during periods of stability. Building on these ideas, several adaptive EWMA-type charts have been proposed. For example, the AEWMA chart adapts the smoothing constant (λ) to improve responsiveness6, while the FAEWMA chart makes a functional response to recent statistics, enhancing sensitivity to small shifts11,12. More recently, Abbasi and Noor-ul-Amin14 introduced the quadratic sigmoid-based adaptive sample size EWMA (QSEWMA) chart, which regulates the sample size through a quadratic sigmoid function to efficiently monitor process dispersion. In contrast, the proposed DACV chart integrates an EWMA structure with a piecewise linear, dynamically updated sample size function. This approach maintains resource efficiency by employing smaller sample sizes during stable conditions and achieves faster detection of potential shifts with larger sample sizes, thus offering a distinct contribution relative to existing adaptive methods.

The study contributes by suggesting the DACV chart, a VSS-EWMA-based approach for monitoring the coefficient of variation. Unlike existing adaptive methods that focus solely on smoothing parameter adaptation or nonlinear sample size schemes, DACV integrates a piecewise linear dynamic sample size adjustment within the EWMA framework. This yields improved detection of small-to-moderate shifts in CV while conserving resources during stable operation. Monte Carlo simulations confirm that DACV chart outperforms traditional fixed-sample EWMA charts in terms of quicker detection and reduced run-length variability. Its practical utility is further demonstrated through application to real industrial data. The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section “Design of the proposed control chart” presents the design of the DACV chart. Section “Performance analysis” discusses performance evaluation using run-length metrics. Section “Discussion” compares its performance with existing control charts. Section “Real data set example” provides a real-life case study. Section “Limitations of the study” concludes the study with key findings and recommendations.

Design of the proposed control chart

This section introduces the formulation of a EWMA control chart for monitoring the CV, referred to hereafter as the FEWMA chart. The proposed design is intended to detect rare or subtle shifts in the CV of a normally distributed production process.

Assume the quality characteristic of interest denoted by Y, follows a normal distribution with mean\({\mu _Y}\) and variance \(\sigma _{Y}^{2}\) such that \(Y\sim N\left( {{\mu _Y},\sigma _{Y}^{2}} \right)\) at any time point \(t \geqslant 1\), the process output \(\left\{ {{Y_t}} \right\}\) continues to follow this distribution. The CV at time t, denoted by \({\gamma _{{Y_t}}}=\frac{{{\sigma _{{Y_t}}}}}{{{\mu _{{Y_t}}}}}\), represents the relative variability of the process. While the mean and S.D may fluctuate across subgroups, the ratio \({\gamma _{{Y_t}}}\) is expected to remain constant in a stable process, such that \({\gamma _{{Y_{t=0}}}}\) denotes the in-control state. when a shift occurs, the system transitions to an out-of-control state with a modified CV\({\gamma _{{Y_{t=1}}}}\), characterized by a shift factor\({\delta _t}=\frac{{{\gamma _{{Y_t}}}}}{{{\gamma _{{Y_{t=0}}}}}}\). In an in-control scenario, this ratio equals \(1\left( {\delta =1} \right)\) for all \(t \leqslant {t_0}\); otherwise, for \(t>{t_0}\), a shift is indicated when\(\delta \ne 1\).

To monitor changes in \({\gamma _{{Y_{t=0}}}}\), a simple random sample of size n is collected from the process output at each time point t. Let the observations be \(\left\{ {{Y_{1t}},{Y_{2t}},\ldots,{Y_{nt}}} \right\}\), where \(i=1,2,\ldots,n.\) For each subgroup, compute the sample mean \(\overline {{{Y_t}}} =\frac{1}{n}\sum\nolimits_{{i=1}}^{n} {{Y_{it}}}\) and the sample S.D \({S_t}=\sqrt {\frac{1}{{n - 1}}\sum\nolimits_{{i=1}}^{n} {{{\left( {{Y_{it}} - \overline {{{Y_t}}} } \right)}^2}} }\). The sample CV at time t is then estimated by \({\hat {\gamma }_t}=\frac{{{S_t}}}{{\overline {{{Y_t}}} }}\), a positive random variable defined over the interval \(\left( {0,\infty } \right)\). Since the CV statistic follows a non-central F distribution, direct monitoring can be challenging due to its skewness. To enable the use of EWMA charts that assume normality, we transform the CV statistic through its cumulative distribution function (CDF) and map it to a standard normal variate. This transformation simplifies chart design and improves detection power.

Statistically, the transformed variable follows a non-central t-distribution \({{\sqrt n } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\sqrt n } {{{\hat {\gamma }}_t}}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{{\hat {\gamma }}_t}}}\) with degrees of freedom \(n - 1\) and a non-centrality parameter\({{\sqrt n } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\sqrt n } {{\gamma _t}}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{\gamma _t}}}\). Equivalently, follows a non-central F-distribution \({{\sqrt n } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\sqrt n } {{{\hat {\gamma }}_t}^{2}}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{{\hat {\gamma }}_t}^{2}}}\) with degrees of freedom \(\left( {1,n - 1} \right)\) and non-centrality parameter \({n \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {n {\gamma _{t}^{2}}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\gamma _{t}^{2}}}\). The cumulative distribution function (CDF) of this non-central F-distribution, denoted as \({F_F}\left( {\frac{n}{{\hat {\gamma }_{t}^{2}}};1,n - 1,\frac{n}{{\gamma _{t}^{2}}}} \right)\), yields a uniformly distributed variable over the interval \(\left( {0,1} \right)\). Applying the inverse CDF of the standard normal distribution\({\phi ^{ - 1}}\), transforms this into a standard normal random variable:

This transformed variable \(Y_{t}^{*}\)is then used as the basis for monitoring the process. If no shift is present, the expected value of \(Y_{t}^{*}\)is zero and the system remains in control \(\left( {{\delta _t}=0fort \leqslant {t_0}} \right)\).However, if the process shifts (\(t \leqslant {t_0}\)), then\({\delta _t} \ne 0\), indicating a departure from the stable CV \({\gamma _{{Y_{t=0}}}}\) resulting in altered variability as reflected in the distribution of \(Y_{t}^{*}.\)

Here, \(\lambda \in \left[ {0,1} \right]\) is the smoothing constant that determines the weight assigned to recent observations. This recursive estimator allows the control chart to adjust dynamically to developing shifts in process variability.

The UCL/LCL based on VSS can be defined as:

Proposed dynamically sample size adjusted EWMA CV control chart

This subsection presents the construction of a novel control chart designed to monitor the CV using a EWMA approach integrated with a VSS mechanism. The proposed chart denoted as DACV control chart, dynamically adjusts the sample size based on the estimated process state, thereby enhancing the chart’s sensitivity to shifts in process variability. Assume the quality characteristic \(Y_{t}\sim N\left( \mu ,\sigma ^{2} \right)\)at time t, with the in-control CV defined as\(CV_{0}=\sigma/\mu\). At each sampling instant, a sample of size\({n_t}\) is drawn from the process and the sample CV is computed as \(C{\hat {V}_t}=S_{t}/{\bar{Y}}_{t}\), where \({\bar{Y}}_{t}\) and \(S_{t}\) is the sample mean and S.D respectively.

To construct a control chart based on the CV, the test statistic at time t is formed as:

Under the assumption of normality, the statistic T follows a non-central F-distribution and its cumulative Probability is mapped to a Standard normal scope:

This transformation yields a normally distributed variable\({X_t}\), which is then monitored using a EWMA Statistic defined recursively in (5):

With \({Z_0}={\mu _0}\) (usually set to 0).

The control limits at each time t are computed as:

Where \(s{z_t}\) is given by:

A key innovation in the DACV chart design is the piecewise linear adaptation of sample size determined based on \({Z_{t - 1}}\). Specifically:

If \({Z_{t - 1}}<\mu - \delta\) then \({n_t}={n_1}\).

If \({Z_{t - 1}}>\mu +\delta\) then \({n_t}={n_2}\).

If \(\mu - \delta \leqslant {Z_{t - 1}} \leqslant \mu +\delta\) then \({n_t}=round\left( {a{Z_{t - 1}}+b} \right)\).

Here, \({n_1}\)and \({n_2}\) are predefined minimum and maximum sample sizes respectively, while a and b control the slope and intercept of the linear region. The parameters\(\delta ,\lambda\)and L govern the responsiveness of the chart. The parameters a and b determine how aggressively the sample size increases as the EWMA statistic deviates from the target. In this study, we set values of a and b following the guidelines of Shabbir et al.13, ensuring a balance between detection speed and sampling cost.

Because the sample size varies, the standard deviation of the EWMA statistic, and hence the control limits, change accordingly. This ensures the chart maintains the desired in-control ARL regardless of sampling conditions. A signal is generated when \({Z_t}\) falls outside the control limits as described in (6). Furthermore, we discussed the flowchart of the design of proposed control chart in Fig. 1.

This VSS-EWMA approach enhances the ability of the control chart to adapt in real-time. In periods of stability, the chart conserves resources by using smaller sample sizes. In contrast, under suspected shifts the sample size increases, improving the detection power. Monte Carlo simulations demonstrate that this structure results in ARLs and tighter run-length distributions, especially for small to moderate shifts in CV.

Performance analysis

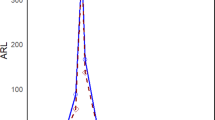

This section evaluates the comparative behavior of the proposed DACV and FEWMA control charts using Monte Carlo simulations. The performance is assessed under various combinations of smoothing constant \(\lambda\), control limit multiplier L, and sample sizes and shifts\(\delta\). The performance indicators include the ARL, SDRL, and percentile run lengths (P05 to P95). To evaluate the efficiency of the proposed DACV chart, we conducted simulations based on the following steps:

-

i.

Initialization of parameters

The simulation begins by defining all necessary parameters. These include the minimum and maximum sample sizes \({n_1}\)and\({n_2}\), the smoothing constant\(\lambda\), the control limit multiplier L, the shift magnitude \(\delta\), and the process mean\(\mu\)and standard deviation\(\sigma\). Additionally, the number of simulation replications (e.g., 50,000) and the maximum number of samples per run (e.g., 1,000,000) are set to ensure statistical reliability.

-

ii.

Begin the simulation loop

For each simulation run, the process starts with an initial sample size equal to \({n_1}\) and the EWMA statistic is initialized as \({Z_0}=0\). Depending on whether the simulation targets an in-control or out-of-control process, data is generated either from the baseline distribution or from a shifted version that reflects a change in the CV.

-

iii.

Iterative monitoring and chart updating

At each time point within a simulation run, a sample of size is drawn from the defined normal distribution. The sample mean and standard deviation are used to compute the CV, which is then converted into a test statistic. This statistic is transformed into a standard normal value, which in turn is used to update the EWMA statistic using the recursive formula \({Z_t}=\lambda {X_t}+\left( {1 - \lambda } \right){Z_{t - 1}}\). The control limits for the chart are computed using the current sample size and the formula for the standard deviation of the EWMA statistic. If the updated EWMA statistic\({Z_t}\)exceeds either the UCL or LCL, the run is terminated and the corresponding run length is recorded. If the statistic remains within the control limits, the process continues to the next sampling point.

-

iv.

Dynamic sample size adjustment

The sample size is updated at each stage depending on the behavior of the EWMA statistic. If the value of \({Z_{t - 1}}\) is close to the target process mean, the next sample size remains at \({n_1}\), reflecting presumed process stability. If \({Z_{t - 1}}\) shows significant deviation from the target, the sample size is increased to\({n_2}\)enhance detection capability. In intermediate situations, the sample size is adjusted according to a linear function of the EWMA statistic, typically expressed as \({n_t}=round\left( {a{Z_{t - 1}}+b} \right)\), where the constants a, b and a threshold\(\delta\)define the response behavior.

-

v.

Repeat the simulation process

Steps 2 through 4 are repeated for a large number of simulation replications in order to generate stable and reliable estimates of performance measures.

-

vi.

Summarize performance metrics

Upon completion of all simulation runs, the results are summarized by calculating the ARL, the SDRL, and selected run length percentiles such as P5, P10, P25, P50, P75, P90, and P95. These metrics collectively provide a comprehensive evaluation of the detection power, stability, and efficiency of the proposed DACV control chart under varying process shift conditions.

Figure 2 describes the simulation steps to calculate the run length profile.

Discussion

Tables 1 and 2 report the results at \(\lambda =0.15\) and \(\lambda =0.25\), respectively. For small shifts \(\left( {\delta =0.25,0.5} \right)\), DACV consistently outperforms FEWMA showing smaller ARLs and narrower SDRLs, especially notable at \(\left( {\delta =0.25} \right)\), where DACV achieves better detection sensitivity with higher percentiles clustering at lower run lengths. As the shift increases to moderate \(\left( {\delta =0.75,0.9} \right)\), DACV demonstrates clear superiority by offering significantly smaller ARLs than FEWMA. For example, at \(\left( {\delta =0.9} \right)\) in Table 1, DACV records an ARL of 64.52 versus 140.4 for FEWMA. This trend becomes more pronounced with larger shifts \(\left( {\delta =1.25,1.50} \right)\) confirming DACV’s responsiveness. Notably, at \(\left( {\delta =1.0} \right)\), both control charts approach the maximum ARL threshold (500), affirming design consistency. However, even in this boundary case DACV maintains a tighter SDRL indicating reduced run-length variability. In Tables 3 and 4 explore scenarios with smaller sample sizes. The superiority of DACV remains evident across both values of \(\lambda\). For small shifts, DACV maintains lower ARLs and more compact percentile ranges. At moderate to large shifts, DACV’s sensitivity is again more pronounced e.g., at \(\left( {\delta =0.75} \right)\), DACV reduces ARL from 52.81 (FEWMA) to 21.71. Interestingly, for large shifts \(\left( {\delta \geqslant 2} \right)\), both charts rapidly detect out-of-control conditions.

In Table 5 presents a sensitivity analysis at ARL0 ≈ 500 across different combinations of \(\lambda\) and L. DACV consistently shows lower ARLs than FEWMA for small to moderate shifts \(\left( {\delta =0.25\,to\,1.25} \right)\), confirming its robustness. At extreme shifts \(\left( {\delta =3.0} \right)\), the performance of both charts converges aligning with the expected behavior where extreme deviations are swiftly detected by any chart. The comparative results confirm that the DACV chart outperforms the FEWMA chart, especially in detecting small to moderate shifts in the CV. DACV offers enhanced sensitivity, reduced run-length variability, and consistent performance across parameter settings. In the all the tables, For large shifts both DACV and FEWMA converge in performance. This is because under extreme deviations, any control chart signals almost immediately, reducing the relative advantage of adaptive mechanisms. In such cases, both charts approach ARL values close to 1, reflecting near-instant detection.

Since the performance measures were obtained through Monte Carlo simulation, it is important to assess the variability of the ARL values. In Table 1 at δ = 0.50, the proposed DACV chart yielded an ARL of 4.11 with SDRL = 1.01, resulting in an Monte Carlo standard error (MCSE) ≈ 0.0045, whereas the FEWMA chart recorded ARL = 4.39 with SDRL = 1.84 and MCSE ≈ 0.0082. Similarly, at δ = 0.90, DACV produced ARL = 64.52 with SDRL = 58.85, corresponding to an MCSE ≈ 0.26, while FEWMA had ARL = 140.4 with SDRL = 136.39 (MCSE ≈ 0.61). These results confirm that the simulation variability is very small relative to the ARL magnitudes, especially for moderate shifts, ensuring the robustness of the reported findings. For large shifts, higher SDRL values reflect the natural variability of run lengths rather than simulation error, yet MCSE values remain small enough to support reliable comparisons between charts.

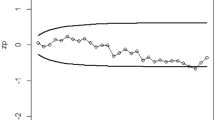

To facilitate a comparative visual analysis of the proposed DACV control chart and the conventional FEWMA chart heat maps were constructed using the simulation results provided in Table 1 (for \(\lambda =0.15\)and sample sizes \({n_1}=5,{n_2}=10\)). Two key performance metrics were visualized: the difference in ARLs between the two charts and the ratio of their ARLs. Figure 3(left panel) presents a heat-map of ARL differences (FEWMA – DACV) across a range of shift magnitudes (δ). This visualization highlights the performance gain achieved by the DACV chart in terms of earlier detection of process shifts. The larger the value, the more quickly DACV responds relative to FEWMA. As evident from the heat-map, the performance gap is most pronounced in the range\(\left( {0.5 \leqslant \delta \leqslant 1.25} \right)\), indicating DACV’s superior sensitivity to small-to-moderate shifts in process variability. Figure 3(right panel) depicts the ARL ratio (FEWMA/DACV), offering a normalized perspective on relative detection efficiency. A ratio greater than 1 confirms faster detection by DACV. The trend reaffirms the earlier finding: DACV consistently achieves lower ARLs across nearly all shift levels, especially around \(\delta =0.75\)to\(\delta =1.0\), where its responsiveness is almost two times faster than that of FEWMA. These heat-map analyses provide compelling visual evidence of DACV’s enhanced performance, making it a more effective tool for monitoring subtle changes in the coefficient of variation under dynamic sampling environments.

Real data set example

The proposed DACV chart is applied to a real-world dataset from the Montgomery15. The dataset consists of 35 samples, each containing 5 wafers, resulting in 175 Flow Width measurements (in microns) collected hourly. To verify the assumption of normality, the Shapiro–Wilk test was conducted on the Flow Width data which indicates that the dataset follows a normal distribution.

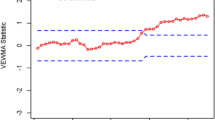

The analysis is divided into two phases. Phase-I comprises the first 20 samples (100 observations), representing an in-control process and is used to establish baseline parameters for the DACV chart. Phase-II includes the remaining 15 samples and simulates out-of-control conditions to evaluate the chart’s ability to detect process deviations. The performance of the proposed DACV dispersion chart was assessed under VSS conditions across different configurations of sample sizes and smoothing constants. The comparison was also made against the conventional FEWMA chart. For implementation, the DACV chart was configured with λ = 0.15 and 0.25, respective minimum and maximum sample sizes are taken as 5 and 10, and piecewise parameters a = 1.5, b = 2. These values were selected based on the sensitivity analysis reported in Section “Performance analysis”, ensuring a balanced trade-off between detection speed and sampling economy. The FEWMA chart was designed under the ARL0 ≈ 370 condition for fair comparison. Figures 4, 5, 6 and 7 illustrate in each case, the DACV chart outperformed the FEWMA chart by detecting shifts earlier. During Phase-I, all four configurations demonstrated process stability as the plotted statistics remained within control limits. This indicates consistent production and effective monitoring under normal conditions. However, when shifted samples were introduced in Phase-II to simulate process variation (i.e., the presence of a shift δ), the DACV charts provided an immediate indication of out-of-control conditions.

As shown in Fig. 4, the DACV chart detected the process shift as early as the 21 st sample, whereas the conventional FEWMA chart (not shown here) signaled the process deviation at the 27th sample. Similar patterns were observed in Figs. 5 and 6, demonstrating that across all tested configurations, the DACV chart consistently detected process shifts more promptly than the FEWMA chart.

This early detection capability underscores the effectiveness of the DACV chart, particularly in a VSS framework, in capturing subtle shifts in process variability. The enhanced responsiveness is especially beneficial in high-precision industries such as semiconductor manufacturing, where timely corrective actions are critical to maintaining production quality. The implementation of DACV charts thus offers a robust approach to process monitoring and can be extended to other industrial sectors for superior quality control.

Limitations of the study

While the DACV chart demonstrates strong performance, several limitations must be noted. First, the study assumes normally distributed and independent observations, which may not hold in all real-world processes. Second, the parameter settings were optimized through simulation, and their transferability to other industrial contexts may require recalibration. Third, the application was based on a specific semiconductor dataset, and broader validation across diverse sectors is still needed. These considerations represent threats to the validity of the findings and provide important directions for future research.

Conclusion and recommendation

This study proposes a new control chart, DACV, designed to better monitor the CV in dynamic production conditions. The proposed chart improves sensitivity to small and moderate shifts compared to conventional EWMA by integrating variable sampling strategies. Large-scale simulations and practical application demonstrate that DACV is more stable and quicker in detection than classical approaches. In practice, DACV is most beneficial in environments where process variability must be closely monitored under changing conditions and where sample collection is costly. For highly stable processes or cases where large shifts dominate, simpler fixed-sample EWMA charts may suffice due to their ease of implementation. However, for processes with frequent small-to-moderate shifts—such as semiconductor manufacturing, chemical industries, or clinical measurement settings—the DACV chart provides earlier detection and more efficient use of resources, making it a preferable choice.

Although the suggested DACV chart records impressive results regarding small-to-moderate shifts, its efficacy relies on the assumption of normality, which may not always hold in real-life applications. Simulation-derived parameter tuning may also limit its generalizability across domains, and the complexity of adaptive sampling can pose challenges in time-sensitive or resource-constrained environments. Future research should explore cost-sensitive designs to formally balance detection speed against sampling effort, investigate machine learning–based dynamic tuning of both smoothing constant and sample size, and extend the DACV framework to non-normal or autocorrelated data. Applications beyond semiconductors would also help validate its generalizability.

Data availability

The datasets used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and are subject to ethical guidelines and institutional policies.

References

Shewhart, W. A. Economic Control of Quality of Manufactured Product (D. Van Nostrand Company, New York 1931).

Roberts, S. W. Control chart tests based on geometric moving averages. Technometrics 1(3), 239–250 (1959).

Page, E. S. Continuous inspection schemes. Biometrika 41(1–2), 100–115 (1954).

Kang, L., Albin, S. L. & Xie, M. Monitoring variability with coefficient of variation charts. J. Qual. Technol. 46(1), 1–12 (2014).

Castagliola, P., Celano, G. & Fichera, S. Monitoring the coefficient of variation using EWMA charts. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 27(4), 407–420 (2011).

Capizzi, G. & Masarotto, G. An adaptive exponentially weighted moving average control chart. Technometrics 45(3), 199–207 (2003).

Riaz, A. et al. Adaptive EWMA control chart for monitoring the coefficient of variation under ranked set sampling schemes. Sci. Rep. 13, 17617. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-45070-x (2023).

Muhammad, A. N. B., Yeong, W. C., Chong, Z. L., Lim, S. L. & Khoo, M. B. C. Monitoring the coefficient of variation using a variable sample size EWMA chart. Comput. Ind. Eng. 126, 378–398 (2018).

Noor-ul‐Amin, M., Tariq, S. & Hanif, M. Control charts for simultaneously monitoring of process mean and coefficient of variation with and without auxiliary information. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 35(8), 2639–2656 (2019).

Amdouni, A., Castagliola, P., Taleb, H. & Celano, G. Monitoring the coefficient of variation using a variable sample size control chart in short production runs. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 81, 1–14 (2015).

Arshad, A., Noor-ul‐Amin, M. & Hanif, M. Monitoring of coefficient of variation with function‐based adaptive exponentially weighted moving average control chart. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 38(2), 1074–1091 (2022).

Arshad, A., Noor-ul‐Amin, M., Dogu, E. & Hanif, M. Performance of function-based AEWMA coefficient of variation control chart with measurement errors. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 53(8), 3978–4000 (2024).

Shabbir, N., Noor-ul‐Amin, M. & Hanif, M. Dynamic sample size based EWMA control chart using piecewise linear function. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 41, 2453–2462. https://doi.org/10.1002/qre.3780 (2025).

Abbasi, A. R. & Noor-ul‐Amin, M. Adaptive sample size strategies for process dispersion using EWMA control chart. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 41(1), 510–531 (2025).

Montgomery, D. C. Introduction To Statistical Quality Control 6th edn (Wiley, Hoboken, 2009).

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R913),Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding

No funding required.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.S. and M.N. developed the main methodology and wrote the initial manuscript draft. M.E.A.E. conducted the literature review and assisted in refining the methodology. A.S. performed the simulations and statistical analysis. M.N. prepared all figures, including heat maps and contour plots. All authors contributed to result interpretation and discussion. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Safeer, A., Elwahab, M.E.A. & Nabi, M. Development of a VSS-EWMA chart for coefficient of variation with application to production process. Sci Rep 15, 38442 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23704-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23704-6