Abstract

Surgical site infection (SSI) after colorectal cancer (CRC) surgery is still a significant healthcare issue. This study aimed to analyze risk factor associated with SSI. A total of 528 consecutive CRC patients who underwent curative resections between September 2017 and August 2024 were analyzed. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and machine learning (ML) models of Random Forest, K-Nearest Neighbor, Decision Tree, and XG Boost were employed for risk factor evaluation. SSI rate was 17.6%. SSI development varied significantly by tumor location, surgical technique, stoma formation, and neoadjuvant therapy. Furthermore, the preoperative values of white blood cell (WBC) count ≤ 5 (103/mcL), lymphocyte count ≤ 1.32 (103/mcL), polymorphonuclear (PMN) count ≤ 3.3 (103/mcL), platelet distribution width (PDW) ≤ 11.2 (fL), and serum creatinine ≤ 0.9 (mg/dL) were associated with SSI development. The results of the ML models also showed that PDW, PMN count, WBC count, lymphocyte count, RDW, serum urea, tumor location, surgery duration, surgical technique, and serum creatinine were the most important factors affecting SSI development. Development of SSI following CRC surgery was associated with several risk factors, including patients’ characteristics and perioperative conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is ranked the third most common cancer, accounting for 10% of the entire newly diagnosed cases worldwide. Its mortality rate ranges from 9.0 to 16.1 per 100,000, making CRC the second most common cause of cancer-related death1,2. Currently, surgical management is the standard treatment for patients with CRC, along with other therapeutic approaches, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy3. One of the most critical postoperative complications occurring in these patients is surgical site infection (SSI)4. Despite all the necessary precautions, including antibiotics, new surgical techniques, perioperative care, and post-surgical hygiene, SSI remains one of the most challenging complications after colorectal surgery due to the presence of a high microbial population in the colon and rectum and the presence of related risk factors1,5. Studies have indicated that the incidence of SSI ranges from 5 to 30% following colorectal surgery6,7. SSI has significant associations with increased hospitalization days, readmission, morbidity, and mortality of CRC patients1,8. In various studies, the relative importance of risk factors in developing SSI remains unclear. To date, advanced age, contaminated or dirty wounds, neoplastic surgery, smoking, obesity, diabetes, immunosuppression, chemotherapy, and steroid use have been identified as the most common risk factors for SSI in post-surgery colorectal cancer patients4,6. Grasping the incidence and risk factors influencing SSI is crucial for developing an efficient prevention strategy and efforts to improve patient outcomes9,10. Nowadays, machine learning (ML) algorithms have emerged as robust techniques for analyzing complex datasets. These algorithms have improved the function to identify patterns in datasets rather than conventional methods. The capabilities of various ML models were employed in several studies to predict factors contributing to post-surgical infections11,12. Despite recent advances, SSI development after surgical treatments and determining its related risk factors remains a critical challenge in CRC surgery. Therefore, this study was designed to identify SSI-associated risk factors and develop feature importance analysis using ML algorithms.

Materials and methods

Colorectal cancer surgery registry characteristics

The data in this retrospective cohort study were obtained from the CRC surgery registry (No: 4001728) approved by Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (MUMS), Mashhad, Iran. All CRC patients who were referred to the colorectal surgical ward at Ghaem Hospital affiliated with MUMS, from September 23, 2017, to August 5, 2024, were included in this registry (n = 621). For CRC confirmation, the result of colonoscopy biopsy in elective situations and intraoperative findings in emergency situations were considered. Before surgery, the physical status of all patients was evaluated using the ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) score. The scale ranges from 1 to 6, with higher scores indicating an increased risk of complications. All of the study participants had an ASA classification score of II or III. Neoadjuvant therapy for patients with advanced rectal and colon cancers as a part of treatment was considered. The neoadjuvant treatment regimen varied depending on the extent of tumor involvement, tumor location, and the patient’s characteristics. For bowel preparation, the patients were given four 10-g sachets of polyethylene glycol (PEG) 4000 flavored powder diluted in a glass of water, if they tolerated, and had no symptoms or signs of bowel obstruction. In addition, they received oral metronidazole 500 mg every 8 h for 48 h before the operation, and a clear liquid diet 24 h prior to surgery. For antibiotic prophylaxis, the patients received intravenous cefazolin (1 g for weights ≤ 80 kg, and 2 g for weights > 80 kg) and metronidazole 500 mg before the skin incision in the operating room.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

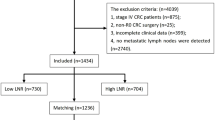

In this study, patients were selected based on in-hospital mortality, tumor location, and surgery techniques. Initially, in-hospital mortality cases (14, 2.2%) attributed to non-SSI causes were excluded. In addition, patients with surgery techniques of exploration (12, 1.9%), local excision (4, 0.6%), palliative stoma formation (51, 8.2%), exenteration (2, 0.3%), perineal colostomy (2, 0.3%), patients with anal melanoma (1, 0.2%), anal squamous cell carcinoma (3, 0.5%) and synchronous colon tumor (4, 0.6%) were excluded. Finally, a total of 528 eligible patients were included in this study. The flowchart of participant inclusion is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Demographic and clinical variables

Demographic and clinical characteristics including age at diagnosis, gender, surgical approach, tumor location, surgical technique resection, operation time, stoma formation status, transfusion during hospitalization, neoadjuvant therapy status, pathological TNM staging, intraoperative complication status, and history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, smoking and past surgical history were evaluated in this study.

Preoperative laboratory findings of white blood cell (WBC) (103/mcL), lymphocyte count (103/mcL), polymorphonuclear (PMN) count (103/mcL), hemoglobin (Hb) (g/dL), red cell distribution width (RDW-CV) (fL), platelet (PLT) (103/mcL), platelet distribution width (PDW) (fL), creatinine (Cr) (mg/dL), urea (mg/dL), sodium (mEq/L) were evaluated to determine the association between these factors and SSI outcome. These parameters pertained to the hospital admission period with a minimum interval of 24 h before the surgery. The instruments for analyzing complete blood count (CBC) and biochemical factors were Sysmex KX-21N and Biotecnica instrument (BT3500), respectively. The quality assessment was conducted in three phases. First, errors in the Levey–Jennings chart were recognized. Second, the lab devices were assessed daily using control samples and monthly by an external sample control group. Third, the coefficient of variation (CV) of laboratory data was determined monthly and compared with the licensed range. Additionally, the laboratory equipment was inspected biannually by a quality assurance company named “Advanced Electronic”.

Outcome definition

In the present study, we defined SSI according to the guideline established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)13. SSIs are classified into three groups: superficial, deep, or organ-space. Superficial SSI refers to infections involving the skin and subcutaneous tissue of the incision, and deep SSI refers to infections occurring in the fascial and muscular layers. Organ-space SSI involves the anatomies that were manipulated during the surgical procedure.

This study described the severity of post-surgical infection based on the Clavien-Dindo grading system14. Study endpoint included SSI occurrence (all three categories) up to 30 days after surgery or earlier for those patients who expired with presenting signs of SSI. The study excluded patients who passed away within 30 days following surgery and showed no signs of SSI. After discharge, up to 30 days following surgery, patients’ follow-up planning was scheduled based on the colorectal clinic days to detect SSI.

Ethical considerations

The current study complied with all relevant national guidelines and institutional regulations and was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the ethics committee of MUMS with ethical code: IR.MUMS.IRH.REC.1403.212. Due to the observational nature of the study, the review board of the ethics committee of MUMS waived the informed consent.

Data preprocessing

Several steps were conducted to preprocess data and prepare it for analysis. In the first step, data was manually checked in order to remove suspicious records. To handle missing data, imputation methods such as mice in R were used to fill in missing values. After these steps, the transformation, including normalization, discretization, and aggregation, were applied to the fields to change them to a suitable format.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative normal variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and non-normal variables were described as median (IQR: interquartile range). Categorical variables were expressed as frequency (percentage). The categorical variables were compared using the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test after checking relevant assumptions. After checking the normality, two-sample t-test or Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare continuous variables, as applicable. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was employed to determine the classifying role of quantitative parameters. The optimal cutoff point of the quantitative parameter was calculated through Youden’s index. The SPSS version 26.0 (Chicago, IL, USA) and MedCalc Statistical Software version 22.005 (MedCalc Software Ltd, Ostend, Belgium; https://www.medcalc.org; 2023) were used for classic analysis. The significance level was considered 0.05.

Four algorithms, including two ensemble learning methods for classification (Random Forest and eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost)), and two non-parametric supervised learning classifiers (Decision Tree and K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN)), were utilized for feature importance analysis. Tune functions in the “caret” package were used to find optimal values for parameters in the models. Leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) technique (considering k as 3) was used in our ML approach to ensure the generalizability, sustainability, and performance of the models, resulting in a less biased or less optimistic estimate of them. The importance of features was analyzed by each model separately, and values for all parameters were provided. These values were then normalized using the min–max normalization method to ensure comparability. Then, an overall importance was assigned to all features by averaging the values calculated by all four models for each feature. All ML models were assessed using the performance evaluation metrics including sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy. Since the data was unbalanced, to prevent the model from overfitting the majority outcome, the OVUN.SAMPLE function from the “ROSE” package was applied, considering a combination of both oversampling and undersampling. R 4.4.2 and RStudio 2024.12.0, along with packages including “Random Forest,” “caret,” “e1071,” “rpart,” and “XGBoost,” were used to apply machine learning models and perform feature importance analysis.

Results

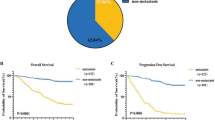

In total, 528 patients with CRC who underwent curative surgery with a mean ± SD age of 56.3 ± 13.4 years were included in this study. Among the patients, 93 (17.6%) experienced SSI during 30 days after surgery (38 (40.9%), 44 (47.3%), and 11 (11.8%) were determined as superficial/deep, organ space, and both superficial/deep and organ space SSIs, respectively.). According to the Clavien-Dindo classification for severity of post-surgical infection, 29 (31.2%) infected patients were categorized as grade II. In addition, 2 (2.2%), 56 (60.2%), 2 (2.2%), and 4 (4.3%) infected patients after surgical procedure were classified as grade Ⅲa, Ⅲb, Ⅳa, and Ⅴ, respectively. Notably, one of the patients classified as grade Ⅳa, assigned a “d” suffix of Clavien-Dindo classification, due to peritonitis caused by anastomotic leakage, which led to stoma formation. This patient still has the stoma. Table 1 shows the characteristics of CRC patients according to the development of SSI. It was demonstrated that tumor location (P < 0.001), surgical techniques (P < 0.001), stoma formation (P < 0.001), and neoadjuvant therapy (P = 0.001) were associated with SSI. Approximately half of the patients with SSI had low or low-middle rectal tumors. Abdominoperineal resection (APR) accounted for the highest percentage (36%) of SSI development compared with other surgical techniques in this study. In addition, 80.6% and 65.6% of affected patients had stoma and history of neoadjuvant therapy, respectively. The comparison of preoperative laboratory parameters between patients with and without SSI is presented in Table 2. Patients who developed SSI during the 30 days after surgery had statistically significant lower values of WBC (P = 0.011), lymphocyte count (P < 0.001), PMN count (P = 0.022), and PDW (P = 0.010) preoperatively.

Figure 2 shows the illustration of normalized feature importance analysis based on four ML models. The results of feature importance analysis aligned with the above-mentioned results, indicating that statistically significant parameters in Tables 1 and 2 were among the top 10 important features. The combined average of normalized feature importance values of four ML models is illustrated in Fig. 3. Laboratory parameters of PDW, PMN count, WBC count, and lymphocyte count, which were known to be correlated with SSI in Table 2, were at the highest rank in Fig. 3. In addition to these variables, the role of tumor location, surgical technique, and surgery duration in the development of SSI should be considered. These three clinical factors were also observed among the top 10 most important factors in Fig. 2. The statistically significant results of the ROC analysis that was conducted for quantitative parameters are presented in Table 3. The preoperative values of WBC count ≤ 5 (103/mcL), PDW ≤ 11.2 (fL), lymphocyte count ≤ 1.32 (103/mcL), PMN count ≤ 3.3 (103/mcL), and serum creatinine ≤ 0.9 (mg/dL) classified patients as infected and non-infected cases, independently.

The normalized values of feature importance analysis based on (A) Random Forest, (B) Decision Tree, (C) K-Nearest Neighbor, and (D) XGBoost models in surgical site infection outcome. Transfusion: Transfusion in hospitalization. Intra-operative…: Intra-operative complication. The performance metrics of the machine learning models are as following: Random forest: Accuracy: 0.71, Sensitivity: 0.81, Specificity: 0.37; Decision tree: Accuracy: 0.58, Sensitivity: 0.64, Specificity: 0.37; K-nearest kneighbour: Accuracy: 0.58, Sensitivity: 0.64, Specificity: 0.37; XG Boost: Accuracy: 0.64, Sensitivity: 0.65, Specificity: 0.70.

Discussion

We conducted a retrospective study to investigate the association between demographic, clinical, and preoperative laboratory data and SSI after CRC resection. In recent years, ML models have also been employed to identify risk factors related to postoperative complications in CRC surgery. The implementation of data-intensive ML algorithms may enhance evidence-based decision-making in surgical practices. The present study revealed that SSI development after CRC surgery was significantly associated with tumor location, surgical technique, stoma formation, and neoadjuvant therapy. Furthermore, preoperative values of WBC count, PMN count, lymphocyte count, PDW, and serum creatinine were defined as classifiers of SSI in ROC analysis. The results of the ML models supported these findings, and almost all mentioned variables were among the most important factors in the incidence of SSI.

However, SSI incidence varies widely in the literature, ranging from 5 to 30%, due to numerous factors6,7. First, this variability is influenced by the case mix demographics of study participants. A number of studies did not include organ/space SSI due to inherent distinctions from incisional SSI. Another key point is that several studies reported SSI did not include rectal cancer due to challenges in rectal surgery compared with colectomies, and therefore, a higher rate of SSI following rectal surgery rather than colectomies. Furthermore, the recent advancement in SSI prevention in oncosurgery may be attributed to comprehensive efforts, including identification of patients’ risk factors, appropriate administration of prophylactic antibiotics, proper skin preparation and drapement, as well as vigilant surveillance15. The overall SSI of 17.6% after CRC surgery in our study is not inferior to any of the recent reports.

The anatomic location of the tumor is one of the most important prognostic factors. Our study is consistent with the previous studies reporting that rectal cancer has a higher risk of SSI rather than colon cancer16,17. Rectal cancer surgery is often associated with ostomy creation, preoperative radiotherapy, and total mesorectal excision along with anastomosis close to the anal verge, all of which may result in prolonged surgical duration and increased bacterial contamination18. Consequently, rectal tumors might be associated with a greater risk of SSI. Regarding the relationship between the surgical technique and SSI, several studies have been conducted. In a study by Chen et al.19, the surgical approach was among the strongest predictors of SSI after CRC surgery using an artificial neural network model. Ikeda et al.20 revealed that APR was strongly associated with SSI in colorectal surgery. Similarly, APR accounted for the highest percentage (36%) of SSI development compared with other surgical techniques in our study. Perineal incision complications, required ostomy formation, tumor location, and technical complexity could explain this relationship.

Not surprisingly, our study revealed that ostomy formation was associated with SSI, and numerous investigations, including recent meta-analyses, have supported this finding7,21. Prolonged exposure to environmental factors, localized tissue injury, and surgical complexity may all be contributing factors21. Nevertheless, it is beneficial for high-risk individuals who are male, malnourished, or who have low pelvic anastomoses22. Because ostomy creation is determined by the systemic or local lesions specified for each patient, it is a relatively unavoidable requirement23. As shown in the present study, the association between extended surgical duration and SSI occurrence is well documented15,16. What is even more remarkable is that there is a significantly elevated linear relationship between operation time and the risk of SSI; the incidence of SSI has increased by 13%, 17%, and 37% for each additional 15, 30, and 60 min of operation time, respectively24. The correlation may be attributed to longer wound exposure to environmental conditions, more complexity of the surgery, and higher risk of surgical trauma7. Our result also revealed that neoadjuvant therapy was correlated with SSI, which is consistent with previous reports16,18. A transient immunosuppression state, particularly following systemic chemotherapy, together with irradiated surgical fields after neoadjuvant radiotherapy, increases the risk of SSI development25. Proactive support of the immune system could be beneficial in high‑risk individuals.

The research on comprehensive indicators of peripheral blood in CRC patients has gained more attention in recent years. Regarding the relationship between the WBC count and its subtypes, including PMN, lymphocyte counts, and infectious complications following surgery, several investigations have been conducted, which have yielded contradictory results. In a study by Huh et al.15, the preoperative WBC number of ≥ 11,000 (cells/mcL) was an independent predictor of SSI after CRC surgery. However, in a study by Mujagic et al.26, preoperative WBC count was not associated with SSI. A study in orthopedic oncology literature investigated the effect of preoperative WBC count on infectious complications following tibial allograft reconstruction and revealed the likelihood of developing deep infections was 88% higher in patients with WBC count of less than 2600 (cells/mcL) as compared to those who had WBC of higher than 2600 (cells/mcL)27. Our study showed that preoperative values of WBC count ≤ 5 (103/mcL), lymphocyte count ≤ 1.32 (103/mcL), PMN count ≤ 3.3 (103/mcL) were significantly associated with development of SSI. In addition, these variables were among the most important features for SSI development in ML models.

While circulating leukocyte count is a reflection of the host’s immune status, neutrophils are often the first line of defense against microbial infections during acute inflammation, and lymphocytes identify certain “non-self” antigens and destroy specific pathogens and those-infected cells28. In a study by Liu et al.16, preoperative lymphocyte count was an important indicator of SSI in patients undergoing robot‑assisted radical resection of CRC, as the lymphocyte count was significantly lower in the SSI group. Preoperative WBC and PMN counts were lower in the SSI group, but there was no statistically significant difference. In a study by Toiyama et al.29, SSI was substantially associated with higher preoperative neutrophil counts in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery for colon cancer. Lymphocyte count was lower in SSI group, but it was not statistically significant.

A weakened lymphocyte-mediated antimicrobial immune response may explain our study finding. Lymphopenia, which is prevalent in advanced malignancies, may lead to compromised immune response. Previous reports indicated that a decrease in serum lymphocytes accelerated tumoral cells proliferation and progression, negatively affecting the prognosis of CRC patients30,31. On the other hand, neoadjuvant therapy is a crucial component of treatment before surgery; nevertheless, some chemotherapy regimens may induce myelosuppression and diminish WBC counts, particularly neutrophil counts32. However, due to interactions between immune cells and numerous potential influencing factors, it is nearly impossible to derive trustworthy conclusions33.

The current study was one of the few studies that investigated the value of PDW in CRC patients. We found that preoperative lower PDW satisfactorily associated with SSI after CRC resection. Few studies have investigated the role of PDW in CRC. Li et al.34 found that decreased PDW was associated with poor disease-free survival and overall survival in CRC patients. Similar to our result, in a study by Li et al.35, preoperative lower PDW significantly contributed to postoperative sepsis following CRC surgery. In addition, PDW was an independently predictive factor of ICU-mortality and 90-day mortality in these patients. The mechanisms elucidating the relationship between preoperative PDW and SSI remain unknown. PDW is a reflection of the platelet size heterogeneity. Platelets are regarded as a significant source of prothrombotic molecules associated with inflammatory markers and contribute to the development and progression of vascular and inflammatory disorders. Platelets with greater size contain many granules that can enhance their hemostatic and proinflammatory functions with increased efficacy36.

Our study showed that preoperative serum creatinine ≤ 0.9 (mg/dL) was correlated with development of SSI. Nasser et al.37 reported higher preoperative creatinine levels were associated with a reduction in superficial SSI following laparoscopic colectomy, but there was no association with deep or organ/space SSI. In contrast, O’Brien et al.38 found no differences in incidence of superficial SSI between patients with different creatinine levels; however, increased creatinine levels were independently correlated with postoperative sepsis. Clinicians routinely notice increased serum creatinine levels, whereas the interpretation of decreased serum creatinine is less definitive. Surgeons should be aware that low serum creatinine can result from iatrogenic fluid overload, liver disease, sepsis, and pregnancy, among other factors. In the absence of these conditions, sarcopenia is the most likely cause of low serum creatinine39. Sarcopenia has been recognized as a risk factor of adverse postoperative outcomes following a variety of surgical procedures, including CRC surgery40.

Last, but not least, SSI may be influenced by the surgeons and hospital-to-hospital differences41. It should be mentioned that there are variations in perioperative preparation, surgical technique, incision care, discharge planning, as well as SSI surveillance. Establishing institutional strategies that incorporate the best components of each institution may be beneficial in reducing SSI incidence21.

Even though ML models need to be externally validated before being implemented in clinical settings, we showed the potential of ML algorithms to improve clinicians’ practice and help target risk-reduction strategies. The results of classical analysis and ML models were aligned in this study, but subtle differences were also observed. Most likely, these discrepancies can be attributed to the different nature of these analyses. Classical analysis evaluates the statistical significance of each variable separately, whereas a feature importance analysis investigates the importance of all variables together. Numerous studies have employed regression models to assess clinical outcomes in CRC patients. However, due to the multicollinearity issues, regression methods were deemed inapplicable, so classification models were used.

The strengths of our study were a relatively large sample size of CRC patients and the evaluation of a large number of clinical variables, accompanied by laboratory variables, which may be less studied compared with the clinical characteristics. These factors are readily available in most clinical settings. Identifying SSI risk factors using these available data is also valuable, particularly for implementing these findings in clinical practice. We conducted a comprehensive investigation using various machine learning models and incorporated a combined feature importance analysis. The main limitation of this study was its single-center, retrospective design, potentially limiting the generalizability of the results. Although our cutoff values were derived from valid statistical analyses, they should be validated in larger studies. Furthermore, laboratory parameters may be affected by unknown factors not measured. However, we implemented some measures to control these factors, such as using the same device to evaluate laboratory data for all patients. In addition, there are other reported risk factors for developing infectious complications following surgery, such as steroid use and preoperative nutritional indices, which we did not include in this study. We recommend that these factors be considered in future research to compare the results more effectively. Future multicenter, prospective studies should be conducted to improve the generalizability and reliability of the findings. The focus of future studies should be on the development of personalized SSI prevention strategies, primarily focused interventions for high‑risk patients, to improve surgical safety and resource allocation.

Conclusion

Development of SSI following CRC surgery is associated with several risk factors, including patients’ characteristics and perioperative conditions. The aforementioned results highlight the importance of personalized assessment of preoperative risks in implementing infection control strategies efficiently in CRC surgery to prevent SSI. In addition, our study demonstrated the promising role of ML models in supporting clinical decision-making on SSI prevention.

Data availability

The dataset analyzed in this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Han, C. et al. Risk factors analysis of surgical site infections in postoperative colorectal cancer: A nine-year retrospective study. BMC Surg. 23(1), 320 (2023).

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clinic. 71(3), 209–249 (2021).

Krasteva, N. & Georgieva, M. Promising therapeutic strategies for colorectal cancer treatment based on nanomaterials. Pharmaceutics. 14(6), 1213 (2022).

Pak, H., Maghsoudi, L. H., Soltanian, A. & Gholami, F. Surgical complications in colorectal cancer patients. Ann. Med. Surg. 55, 13–18 (2020).

Kamboj, M. et al. Risk of surgical site infection (SSI) following colorectal resection is higher in patients with disseminated cancer: An NCCN member cohort study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 39(5), 555–562 (2018).

Calu, V., Piriianu, C., Miron, A. & Grigorean, V. T. Surgical site infections in colorectal cancer surgeries: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of surgical approach and associated risk factors. Life. 14(7), 850 (2024).

Xu, Z. et al. Update on risk factors of surgical site infection in colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 35, 2147–2156 (2020).

Smith, R. L. et al. Wound infection after elective colorectal resection. Ann. Surg. 239(5), 599–605 (2004).

Tartari, E. et al. Patient engagement with surgical site infection prevention: An expert panel perspective. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 6, 1–9 (2017).

Saleh, K. & Schmidtchen, A. Surgical site infections in dermatologic surgery: Etiology, pathogenesis, and current preventative measures. Dermatol. Surg. 41(5), 537–549 (2015).

Merath, K. et al. Use of machine learning for prediction of patient risk of postoperative complications after liver, pancreatic, and colorectal surgery. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 24(8), 1843–1851 (2020).

Wu, G. et al. Performance of machine learning algorithms for surgical site infection case detection and prediction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Med. Surg. 84, 104956 (2022).

(CDC) CfDCaP. Surgical Site Infection Event (SSI) [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/9pscssicurrent.pdf.

Dindo, D., Demartines, N. & Clavien, P.-A. Classification of surgical complications: A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann. Surg. 240(2), 205–213 (2004).

Huh, J. W. et al. Oncological outcome of surgical site infection after colorectal cancer surgery. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 34, 277–283 (2019).

Liu, G. & Ma, L. Factors influencing surgical site infections and health economic evaluation in patients undergoing robot-assisted radical resection for colorectal cancer. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 20(7), 2125–2132 (2024).

Murray, A. C. A., Pasam, R., Estrada, D. & Kiran, R. P. Risk of surgical site infection varies based on location of disease and segment of colorectal resection for cancer. Dis. Colon Rectum 59(6), 493–500 (2016).

Konishi, T., Watanabe, T., Kishimoto, J. & Nagawa, H. Elective colon and rectal surgery differ in risk factors for wound infection: Results of prospective surveillance. Ann. Surg. 244(5), 758–763 (2006).

Chen, K. A. et al. Improved prediction of surgical-site infection after colorectal surgery using machine learning. Dis. Colon Rectum 66(3), 458–466 (2023).

Ikeda, A. et al. Wound infection in colorectal cancer resections through a laparoscopic approach: A single-center prospective observational study of over 3000 cases. Dis. Oncol. 12, 1–7 (2021).

Chen, Y. et al. A meta-analysis of the risk factors for surgical site infection in patients with colorectal cancer. Int. Wound J. 21(2), e14459 (2024).

Hanna, M. H., Vinci, A. & Pigazzi, A. Diverting ileostomy in colorectal surgery: When is it necessary?. Coloproctology 37, 311–320 (2015).

Sagawa, M. et al. Worse preoperative status based on inflammation and host immunity is a risk factor for surgical site infections in colorectal cancer surgery. J. Nippon Med. Sch. 84(5), 224–230 (2017).

Cheng, H. et al. Prolonged operative duration increases risk of surgical site infections: a systematic review. Surg. Infect. 18(6), 722–735 (2017).

Bislenghi, G. et al. Risk factors for surgical site infection after colorectal resection: a prospective single centre study. An analysis on 287 consecutive elective and urgent procedures within an institutional quality improvement project. Acta Chir. Belg. 121(2), 86–93 (2021).

Mujagic, E. et al. The role of preoperative blood parameters to predict the risk of surgical site infection. Am. J. Surg. 215(4), 651–657 (2018).

Lozano-Calderón, S. A., Swaim, S. O., Federico, A., Anderson, M. E. & Gebhardt, M. C. Predictors of soft-tissue complications and deep infection in allograft reconstruction of the proximal tibia. J. Surg. Oncol. 113(7), 811–817 (2016).

Kitayama, J., Yasuda, K., Kawai, K., Sunami, E. & Nagawa, H. Circulating lymphocyte number has a positive association with tumor response in neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for advanced rectal cancer. Radiat. Oncol. 5, 1–6 (2010).

Toiyama, Y. et al. Neutrophil priming as a risk factor for surgical site infection in patients with colon cancer treated by laparoscopic surgery. BMC Surg. 20, 1–8 (2020).

Yang, J. et al. Pre-treatment inflammatory indexes as predictors of survival and cetuximab efficacy in metastatic colorectal cancer patients with wild-type RAS. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 17166 (2017).

Noh, O. K., Oh, S. Y., Kim, Y. B. & Suh, K. W. Prognostic significance of lymphocyte counts in colon cancer patients treated with FOLFOX chemotherapy. World J. Surg. 41, 2898–2905 (2017).

Vijayakumar, G. et al. Evaluation of absolute neutrophil count in the perioperative setting of sarcoma resection. Adv. Orthop. 2024(1), 4873984 (2024).

Lederer, A.-K., Bartsch, F., Moehler, M., Gaßmann, P. & Lang, H. Morbidity and mortality of neutropenic patients in visceral surgery: A narrative review. Cells 11(20), 3314 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. Prognostic evaluation of colorectal cancer using three new comprehensive indexes related to infection, anemia and coagulation derived from peripheral blood. J. Cancer. 11(13), 3834–3845 (2020).

Li, X. T., Yan, Z. & Wang, R. T. Preoperative mean platelet volume and platelet distribution width predict postoperative sepsis in patients with colorectal cancer. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 9438750 (2019).

Abdel-Razik, A., Eldars, W. & Rizk, E. Platelet indices and inflammatory markers as diagnostic predictors for ascitic fluid infection. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 26(12), 1342–1347 (2014).

Nasser, H., Ivanics, T., Leonard-Murali, S. & Stefanou, A. Risk factors for surgical site infection after laparoscopic colectomy: An NSQIP database analysis. J. Surg. Res. 249, 25–33 (2020).

O’Brien, M. M. et al. Modest serum creatinine elevation affects adverse outcome after general surgery. Kidney Int. 62(2), 585–592 (2002).

Loria, A. et al. Low preoperative serum creatinine is common and associated with poor outcomes after nonemergent inpatient surgery. Ann. Surg. 277(2), 246–251 (2023).

Nakanishi, R. et al. Sarcopenia is an independent predictor of complications after colorectal cancer surgery. Surg. Today 48(2), 151–157 (2018).

Ito, M. et al. Influence of learning curve on short-term results after laparoscopic resection for rectal cancer. Surg. Endosc. 23(2), 403–408 (2009).

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.R & M.A.: Writing_original draft, Writing_review, and editing; A.A & A.G: Quality control’s data, Colorectal consultant Mh.T.: Writing_original draft; M.ZS.: Patients’follow-up, Resources, F.S: Chief colorectal cancer registrar, Traditional analysis, Supervision-lead; SM.T: Machine learning models development, Supervision-lead. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rahimi, M., Ansari, M., Abdollahi, A. et al. A comprehensive feature importance analysis of surgical site infection following colorectal cancer surgery. Sci Rep 15, 40004 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23722-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23722-4